Abstract

Background:

Postoperative ileus remains the most common cause of prolonged hospital stay after abdominal surgery. Various agents have been tested in the treatment of postoperative ileus but no agent alone has achieved effectiveness as postoperative ileus is of multifactorial aetiology.

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to assess the effects of combined use of gum-chewing and parenteral metoclopramide on the duration of postoperative ileus after abdominal surgery.

Materials and Methods:

This was a randomised controlled study of patients aged 16–65 years who underwent elective abdominal surgeries. Patients were randomised into a gum-metoclopramide (GM) group, a gum-only (G) group, a metoclopramide-only (M) group and a control (C) group. Patients in the GM group chewed gum and received intravenous metoclopramide, each 8 hourly. In G group, patients chewed only gum, whereas those in M group received only 10mg of intravenous metoclopramide, 8 hourly. To C group, 10 mL of intravenous sterile water was given 8 hourly. Patients were monitored for time to passage of first flatus or faeces. Groups were compared for the duration of postoperative ileus and duration of hospital stay using analysis of variance. Statistical significance was set at a P value of <0.05.

Results:

Fifty-two out of the 105 recruited patients were eligible for analysis. The male-to-female ratio was 1:1.9 with a median age of 57.0 years (interquartile range [IQR] =16 years). Prolonged postoperative ileus occurred in 9.4% (n = 5) of the patients (GM = 2, G = 1, M = 2, C = 0; P = 0.604) and was associated with longer duration of nasogastric tube use (P = 0.028). The duration of postoperative ileus was 3 days (IQR = 2), 2.5 days (IQR = 3.3), 4 days (IQR = 1.5) and 3 days (IQR = 2) in the GM, G, M, and C groups, respectively (P = 0.317), whereas the median duration of hospital stay was 7 days (IQR = 3), shortest in G group (6.5 days, IQR = 8) and longest in M group (9 days, IQR = 3) (P = 0.143).

Conclusions:

The combined use of gum-chewing and parenteral metoclopramide had no effect on the duration of postoperative ileus following abdominal surgeries in adult surgical patients.

Keywords: Abdominal surgery, gum-chewing, ileus, metoclopramide

Introduction

The term ileus was first described by Cannon and Murphy in 1906 and it refers to the loss of gastrointestinal peristalsis.[1] In postoperative ileus, there is a transient cessation of coordinated bowel motility after surgery which prevents effective transit of intestinal contents and/or tolerance of oral intake.[2] Although other non-abdominal procedures can potentially predispose patients to postoperative ileus, gastrointestinal surgeries in particular are more commonly implicated.[2]

Many researchers consider ‘normal’ or ‘uncomplicated’ postoperative ileus as a predictable and inevitable phase in postoperative bowel recovery after abdominal surgery and only consider ileus lasting more than 5 days as prolonged following laparotomy[3,4] or greater than 3 days following laparoscopic surgery.[5] Therefore, the cutoff day for distinguishing between prolonged postoperative ileus and normal postoperative ileus varies between 4 and 6 days. This is because an internationally accepted standard of definition is lacking.[6]

The aetiology of postoperative ileus is multifactorial. This includes preoperative factors such as preoperative bowel preparation, prolonged preoperative fasting, preoperative opioid use, previous abdominal surgery, increasing age, presence of systemic inflammation and comorbidities (e.g. diabetic gastroparesis),[7,8,9] intraoperative factors such as the type of anaesthesia (use of general anaesthesia), extent of surgery, intraoperative opioid use, injudicious intravenous fluid administration, intraoperative blood loss, prolonged duration of surgery, degree of intra-peritoneal contamination and the surgical access.[10,11] The postoperative factors include postoperative opioid use, use of nasogastric tube, postoperative pain, and electrolyte disturbance.[12] However, the major cause of postoperative ileus is surgery itself.[8]

Various modalities have been used in the prevention and treatment of postoperative ileus. These are categorised as clinical or pharmacological. The clinical approach includes avoidance of perioperative opioid analgesia, selective use of nasogastric tube postoperatively, use of epidural anaesthesia, use of laparoscopic approach in preference to laparotomy, minimal bowel handling, judicious intraoperative fluid administration, early enteral feeding and use of sham feeding postoperatively.[13,14] The aim of pharmacologic management is to minimise sympathetic inhibition of the gastrointestinal motility, decrease inflammation, stimulate gastrointestinal motility and reduce the stimulatory effect of opioids on gastrointestinal miu (μ) receptors. The pharmacologic options include the use of macrolide antibiotics and motilin-receptor agonists such as erythromycin, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors like neostigmine, μ-receptor antagonists like alvimopan and anti-emetic agents like metoclopramide.[15] Although widely reported to be effective in several studies,[15,16,17] the use of alvimopan is limited by availability, cost and logistics involved in its procurement and storage.[18] Other prokinetic agents that have been tried include parenteral lidocaine, 5-hydroxytryptamine-4(5-HT4) agonists such as cisapride (now withdrawn due to the profound side effects of cardiac arrhythmias), ghrelin receptor agonists like capromorelin and colon-stimulating laxatives like bisacodyl and lactulose.[19]

Sham feeding is a type of feeding where a food substance is chewed without being swallowed. Gum-chewing (a type of sham feeding) stimulates motility of the human duodenum, stomach and rectosigmoid.[20] It has been shown to increase the serum concentration of the peptide hormones gastrin, the neuropeptide neurotensin and pancreatic polypeptide, all of which are prokinetic.[18] Gum-chewing improves bowel function by not only increasing vagal cholinergic stimulation of the gut but its anti-inflammatory effects on the gut with subsequent release of promotility agents.[18,20] This is because the process of gum-chewing, although simple, mimicks normal feeding and so elicits similar myoelectric and endocrine stimulation necessary for bowel function.[18] It is cheap, easily available, safe and effective.[12,20,21] Majority of studies have reported its beneficial effect in reducing postoperative ileus.[22,23,24]

Metoclopramide is an anti-emetic that promotes gastric emptying. It is a dopamine receptor antagonist with mixed 5HT3 receptor antagonist and 5HT4 receptor agonist effects. Neuronal stimulation with prokinetic 5HT4 receptor agonists and dopamine receptor antagonists have been found to ameliorate the motility disorder associated with postoperative ileus.[7] The use of Metoclopramide in the management of postoperative ileus stems from this prokinetic property. However, studies on the management of postoperative ileus using metoclopramide have revealed conflicting results although the majority have reported it has no additional benefit in postoperative ileus.[5,15,16] Postoperative ileus is a condition of multifactorial aetiology; hence, a multimodal approach involving a combination of different modalities of reducing it has been advocated.[16] Although the effectiveness of most single modalities is limited, a combination of different strategies may be synergistic.

Postoperative ileus increases the duration of hospital stay, increasing the risk of postoperative complications and incurs extra costs on the patient and healthcare systems. This is more worrisome in our environment where most of the patients pay out of pocket. Instead of waiting for normal return of bowel function after abdominal surgeries, hastening this recovery process using a cheap multimodal approach may reduce the duration of postoperative ileus in our patients. Studies investigating the effects of gum-chewing and use of prokinetic agents as a multimodal approach are scarce and the few available related studies were either not for general surgical procedures or involved a single agent intervention. The focus of this study was to examine the effects of the combined use of gum-chewing (a clinical approach) and parenteral metoclopramide (a pharmacological strategy) on the duration of postoperative ileus after abdominal surgery in adult surgical patients seen at our institution.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective randomised controlled trial (RCT) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT05669781) carried out at our institution, from 1 October 2018 to 30 September 2019. Ethical approval was obtained from our institutional review board with the ethics committee assigned number: UI/EC/18/0231. Study participants were recruited from adult patients presenting through the surgical outpatient (SOP) clinic and non-surgical wards of our institution to the endocrine, oncological and gastrointestinal surgery divisions of general surgery over the study period. All patients requiring elective laparotomy aged 16–65 years were recruited for the study. Emergency laparotomies and structural or functional inability to chew gum constituted the exclusion criteria. During data analysis, only patients who had gastrointestinal resection with or without anastomosis were included, whereas those who had elective laparotomy without gastrointestinal resection or anastomosis were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained from all eligible patients.

Study participants were randomised into four groups (GM, G, M and C groups) using blocked sequence randomisation. Consecutive adult surgical patients (aged 16–65 years) booked for elective abdominal surgery were prospectively enrolled into the four study groups via the SOP clinic of our institution. A computer-generated blocked randomisation sequence was used to insert the instruction ‘1’ or ‘2’ or ‘3’ or ‘4’ (representing GM, G, M, and C groups, respectively) consecutively to 105 serially numbered envelopes, all of which were sealed afterward. The envelopes were pulled serially with each consecutive patient.

Data were obtained through a detailed history and physical examination and included demographic variables such as age and gender. Medical history of previous abdominal surgeries and any comorbidity such as chronic constipation, diabetes mellitus, parkinsonism, renal or cardiac disease were sought and allergy to metoclopramide or gum was noted. Body mass index (BMI) and relevant investigation results were recorded. Other pre- and intraoperative data recorded included: clinical diagnosis, American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) grade, type of anaesthesia, cadre of surgeon, surgical access (laparoscopic versus open), length of skin incision, intraoperative estimated blood loss (EBL), total intraoperative fluid administered, duration of surgery, surgical procedure done and duration of anaesthesia. Recorded postoperatively were time to passage of first flatus, time to passage of first faeces, time to initial recording of bowel sounds, time to tolerance of normal diet, day of first ambulation, length of hospital stay, cost of hospital stay and postoperative complications.

Informed consent was obtained from all patients that met the inclusion criteria. All patients for elective surgery were admitted at least a day before surgery and kept on nothing by mouth from 12 midnight on the eve of surgery. Patients with class 2 or more wounds were given intravenous metronidazole and ceftriaxone at the induction of anaesthesia. All the patients had general anaesthesia and a nasogastric tube passed. Abdominal skin incision was made by the surgeon who was either a senior registrar or consultant in general surgery and to whom the patient’s group was undisclosed. Standard procedures (surgical and aesthetic) relevant to each case were carried out. The group assigned to each patient was known only to the research assistants (a house surgeon and the nursing staff) who alone administered the intervention to the appropriate groups. Although what was used for intravenous intervention was undisclosed to the patients in the GM, M and C groups, it was not possible to blind patients who received gum-only (G group).

All interventions were commenced from the first postoperative day. Patients in G group were given one stick of sugar-free gum (Orbit, Wrigley, US) 8 hourly daily till either first flatus or faeces was passed with an instruction to chew for 15 min(only) without swallowing the chewed gum. The criteria for discontinuing each intervention was not disclosed to the patients. The gum was given to patients at a fixed interval to help monitor compliance. Patients in the metoclopramide-only (M) group received intravenous metoclopramide (Philometro, Hubei Tianyao) 10 mg 8 hourly for the first 72 h postoperatively. The gum-metoclopramide (GM) group received intravenous metoclopramide and also chewed gum using the protocol earlier described for G and M groups. Patients assigned to the control (C) group received 10 mL of sterile water intravenously 8 hourly for the first 72 h postoperatively.

All patients were asked to notify the nursing staff at first passage of flatus. A blinded doctor visited the patients 8 hourly and recorded the time of the first bowel sounds, passage of flatus, and defecation. After giving each intervention, the type and time of intervention was documented in an identifier-free patient’s questionnaire. The first time of flatus and defecation was recorded based on the patient’s own statements. Prolonged postoperative ileus was defined as ileus lasting more than 5 days following laparotomy or greater than 3 days following laparoscopic surgery.[25] Nasogastric tube was removed on the day of return of bowel function. The total duration of hospital stay, calculated from the first postoperative day to the day of discharge, was recorded.

The association between categorical and numerical perioperative factors with prolonged postoperative ileus was analysed using the chi-square (or Fisher’s exact) test and Mann–Whitney U, respectively. Comparison of groups in terms of the duration of postoperative ileus was done using the Kruskal–Wallis test. Secondary endpoints compared between the groups included time to first bowel sound, duration of hospital stay and cost of hospital stay. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Data were analysed by using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 23.0 for Windows (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Results

Patients’ demographic and perioperative characteristics

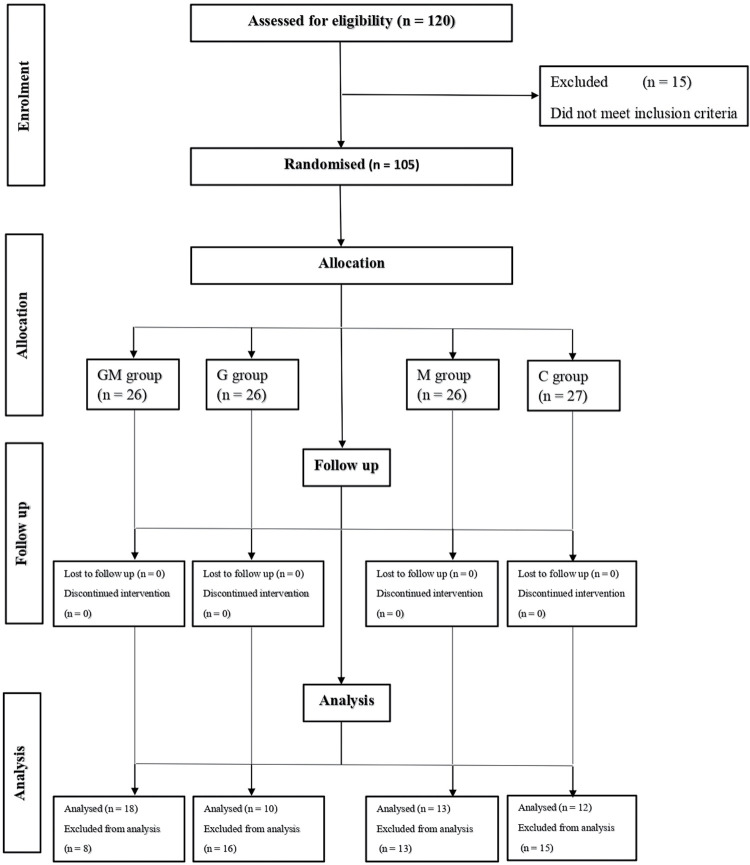

A total of 105 patients were recruited for the study with only 53 included for data analysis. The CONSORT flow diagram depicting the flow of participants through the study is shown in Figure 1. As shown in Table 1, 65.9% (n = 27) were females, whereas 34.1% (n = 14) were males with a male: female ratio of 1:1.9. The median age was 57.0 years (interquartile range [IQR] = 16) with majority of them (65.9%, n = 27) being 55 years and above. The four groups were comparable in perioperative factors such as age, BMI, ASA grade, presence/absence of comorbidity, cadre of surgeon, duration of surgery/ anaesthesia and distribution of surgical procedures, except for gender where a statistically significant difference was obtained across the groups (P = 0.020). The mean BMI was 23.1 ± 4.9kg/m2. Only 9.8% (n = 4) were obese, whereas 53.7% (n = 22) had normal BMI. Majority of the patients were in the ASA grades III (46.3%, n = 19) and II (41.5%, n = 17).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram showing participant distribution through the study

Table 1.

Distribution of perioperative factors between the study groups

| GM group (n = 18) | G group (n = 10) | M group (n = 13) | C group (n = 12) | Total (n = 53) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||||

| Average age (IQR) | 56.0 (16) | 62.0 (12) | 54.0 (17) | 60.0 (21) | 57.0 (16) | 0.588 |

| 16–24 years | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 25–34 years | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (18.2) | 3 (7.3) | |

| 35–44 years | 2 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (7.3%) | 0.312 |

| 45–54 years | 3 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (18.2) | 8 (19.5) | |

| 55+ years | 7 (58.3) | 8 9100.0) | 5 (50.0) | 7 (63.6) | 27 (65.9) | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 1 (8.3) | 6 (75.0) | 4 (40.0) | 3 (27.3) | 14 (34.1) | 0.020 |

| Female | 11 (91.7) | 2 (25.0) | 6 (60.0) | 8 (72.7) | 27 (65.9) | |

| BMI | 21.8 ± 4.3 | 21.6 ± 3.8 | 22.7 ± 3.9 | 26.1 ± 6.1 | 23.1 ± 4.9 | 0.113 |

| Underweight | 2 (16.7) | 2 (25.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0) | 5 (12.2) | |

| Normal | 6 (50.0) | 5 (62.5) | 6 (60.0) | 5 (45.5) | 22 (53.7) | 0.089 |

| Overweight | 4 (33.3) | 1 (12.5) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (18.2) | 10 (24.4) | |

| Obese | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (36.4) | 4 (9.8) | |

| ASA grade | ||||||

| Grade I | 0 (0) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (9.10 | 3 (7.3) | |

| Grade II | 5 (41.7) | 3 (37.5) | 6 (60.0) | 3 (27.3) | 17 (41.5) | 0.828 |

| Grade III | 6 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 3 (30.0) | 6 (54.5) | 19 (46.3) | |

| Grade IV | 1 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (4.9) | |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Yes | 8 (44.4) | 2 (20.0) | 5 (38.5) | 6 (50.0) | 21 (39.6) | 0.506 |

| No | 10 (55.6) | 8 (80.0) | 8 (61.5) | 6 (50.0) | 32 (60.4) | |

IQR = interquartile range, BMI = body mass index, ASA = American Society of Anaesthesiologists

Clinical characteristics of patients

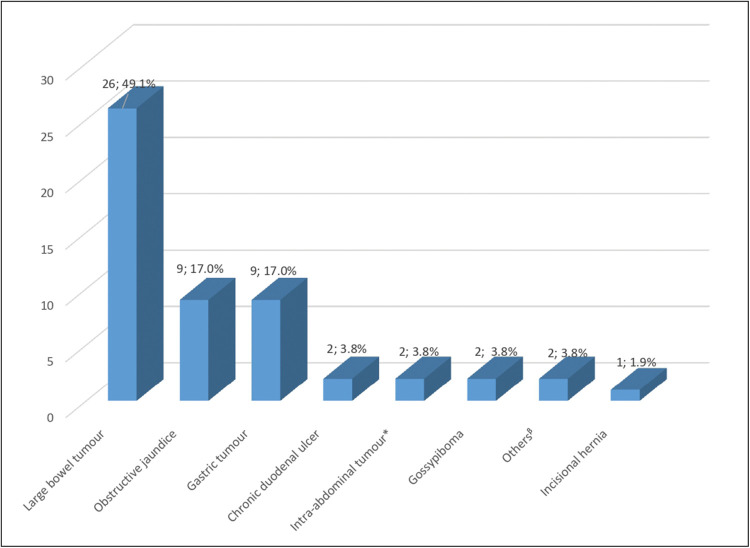

Majority of the patients (n = 15; 28.3%) had abdominal pain as their presenting complaint. Comorbidity was present in over one-third of the patients (n = 21; 39.6%), the most common being hypertension. As depicted in Figure 2, the most common diagnosis was large bowel tumour (n = 26; 49.1%), followed by obstructive jaundice (n = 9; 17.0%) and gastric tumour (n = 9; 17.0%). Although 65.4% of the large bowel tumours and 77.8% of the obstructive jaundice occurred in females, gastric tumours were slightly higher in males than females (n = 5; 55.6% vs n = 4; 44.4%).

Figure 2.

Distribution of patients by diagnosis. *Excludes large bowel and gastric tumor; β Includes enterocutaneous fistula & adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis

The mean values of serum electrolytes, blood urea and creatinine, and the haematocrit in the preoperative and early postoperative periods were within normal limits with a mean fasting blood sugar of 102.0 ± 30.0mg/dl. The admission-to-intervention time was below 24 h in 18.9% of patients (n = 10), whereas the rest (81.1%; n = 43) were admitted 24 h and above before surgery.

Surgical procedures performed and intraoperative data

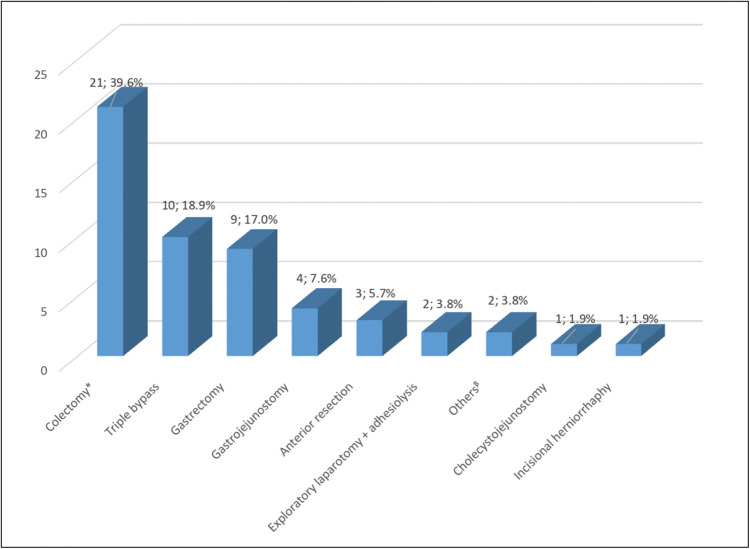

Figure 3 shows the distribution of patients by surgical procedures done, the most frequently performed procedure being colectomy (39.6%, n =21), followed by triple bypass (18.9%, n = 10) and gastrectomy (17.0%, n = 9).

Figure 3.

Distribution of patients by type of surgical procedure. *Includes only hemicolectomies and sigmoidectomies; β Includes closure of colostomy and repair of multiple small bowel fistulae.

Most of the procedures (71.7%; n = 38) were performed by a consultant, whereas the rest (28.3%; n = 15) were done by a senior registrar as shown in Table 2. The median duration of surgery and anaesthesia were 120 min (IQR = 62) and 140 min (IQR = 74), respectively. All the procedures were via an open approach.

Table 2.

Intraoperative parameters

| GM group (n = 18) | G group (n = 10) | M group (n = 13) | C group (n = 12) | Total (n = 53) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadre of surgeon | ||||||

| Senior registrar | 6 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (23.1) | 6 (50.0) | 15 (28.3) | 0.068 |

| Consultant | 12 (66.7) | 10 (100.0) | 10 (76.9) | 6 (50.0) | 38 (71.7) | |

| Duration of surgery | 120 (75) | 70 (75) | 128 (134) | 110 (50) | 120 (62) | 0.117 |

| Duration of anaesthesia | 155 (40) | 92 (66) | 147 (134) | 135 (75) | 140 (74) | 0.214 |

| Length of skin incision (cm) | 19.8 ± 2.1 | 18.1 ± 4.3 | 20.9 ± 3.4 | 19.8 ± 3.7 | 19.8 | 0.485 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 150 (475) | 250 (587) | 375 (1350) | 325 (312) | 300 (350) | 0.318 |

| Intraoperative fluid administered (litres) | 2.2 (1.4) | 2.0 (0.8) | 2.5 (1) | 2.0 (1.4) | 2 (1) | 0.189 |

Postoperative outcomes and cost of care

Postoperatively, only 4 (7.5%) of the patients were admitted in the intensive care unit (ICU) [Table 3]. Of these, 1 patient was in the GM group, 1 in the M group and 2 in C group with none in the G group. Two patients (3.8%; all in the GM group) had their nasogastric tubes re-inserted, whereas 2 patients (3.8%) required re-laparotomy (GM = 1, M = 1). None of the patients in the G and C groups required nasogastric tube re-insertion or re-laparotomy. The median duration of hospital stay was 7.0 days (IQR = 3), lowest in G group (6.5 days; IQR = 8) and highest in M group (9 days; IQR = 3).

Table 3.

Postoperative outcomes of patients

| GM group (n = 18) | G group (n = 10) | M group (n = 13) | C group (n = 12) | Total (n = 53) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | ||||||

| Yes | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (16.7) | 4 (7.5) | 0.503 |

| No | 17 (94.4) | 10 (100.0) | 12 (92.3) | 10 (83.3) | 49 (92.5) | |

| Duration of NGT use | 4 (3) | 4 (1) | 5 (2) | 4 (2) | 4 (1) | 0.108 |

| NG tube reinsertion | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.8) | 0.257 |

| No | 16 (88.9) | 10 (100.0) | 13 (100.0) | 12 (100.0) | 51 (96.2) | |

| Need for re-laparotomy | ||||||

| Yes | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.8) | 0.666 |

| No | 17 (94.4) | 10 (100.0) | 12 (92.3) | 12 (100.0) | 51 (96.2) | |

| Postop complications nausea | ||||||

| Yes | 3 (16.7) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (7.5) | 0.234 |

| No | 15 (83.3) | 9 (90.0) | 13 (100.0) | 12 (100.0) | 49 (92.5) | |

| Vomiting | ||||||

| Yes | 4 (22.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (7.5) | 0.038 |

| No | 14 (77.8) | 10 (100.0) | 13 (100.0) | 12 (100.0) | 49 (92.5) | |

| Abdominal distention | ||||||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.8) | 0.425 |

| No | 18 (100.0) | 9 (92.3) | 12 (100.0) | 12 (100.0) | 51 (96.2) | |

| Length of hospital stay | 7.0(4) | 6.5 (8) | 9 (3) | 7 (2) | 7.0 (3) | 0.143 |

| Outcome | ||||||

| Discharged | 17 (94.4) | 10 (100.0) | 12 (92.3) | 12 (100.0) | 51 (96.2) | 0.666 |

| Dead | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.8) | |

| Need for readmission | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.7) | 0.490 |

| No | 16 (88.9) | 10 (100.0) | 12 (92.3) | 12 (100.0) | 50 (94.3) | |

ICU = intensive care unit, NGT = nasogastric tube

The in-hospital mortality was 3.8% (n = 2; 1 in the GM group and 1 in M group.) with only 5.7% of patients (n = 3) requiring re-admission. Two of the patients requiring re-admission were in GM group, whereas 1 was in M group.

The cost of intervention was ₦306 (IQR = 217), ₦114 (IQR = 91), ₦225 (IQR = 113), and ₦240 (IQR =120) in the GM, G, M and C groups, respectively (P = 0.001), with a median of ₦226 (IQR = 120). The median cost of hospital stay was ₦9600 (IQR = 3000) with the patients in the GM, G, M and C groups spending ₦9000 (IQR = 4500), ₦8400 (IQR = 2400), ₦10,800 (IQR = 3600) and ₦8400 (IQR = 2400) (P = 0.080).

Distribution of postoperative ileus and factors associated with prolonged postoperative ileus

Prolonged postoperative ileus occurred in 5 (9.4%) of the patients (GM = 2, G = 1, M = 2, C = 0; P = 0.604). There was no association between perioperative factors such as age, gender, comorbidity status, history of smoking/ alcohol use, BMI, ASA grade, preoperative opioid use, cadre of surgeon and prolonged postoperative ileus [Table 4a]. However, all the five patients that had a prolonged postop ileus were aged 55 years and above.

Table 4a.

Categorical factors associated with prolonged postop ileus

| Prolonged postop ileus | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 13 (34.2) | 2 (50.0) | 0.608 |

| Female | 25 (65.8) | 2 (50.0) | |

| Age | |||

| 16–24 years | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.530 |

| 25–34 years | 3 (7.9) | 0 (0) | |

| 35–44 years | 3 (7.9) | 0 (0) | |

| 45–54 years | 8 (21.1) | 0 (0) | |

| 55+ years | 24 (63.2) | 4 (100.0) | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| None | 24 (63.2) | 2 (50.0) | 0.628 |

| Yes | 14 (36.80 | 2 (50.0) | |

| History of smoking | |||

| Yes | 4 (10.5) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| No | 34 (89.5) | 4 (100.0) | |

| History of alcohol use | |||

| Yes | 5 (13.2) | 1 (25.0) | 0.474 |

| No | 33 (86.8) | 3 (75.0) | |

| BMI | |||

| Underweight | 4 (10.5) | 1 (25.0) | 0.591 |

| Normal | 21 (55.3) | 1 (25.0) | |

| Overweight | 9 (23.70 | 1 (25.0) | |

| Obese | 4 (10.5) | 1 (25.0) | |

| ASA grade | |||

| Grade I | 3 (7.9) | 0 (0) | 0.206 |

| Grade II | 16 (42.1) | 2 (50.0) | |

| Grade III | 18 (47.4) | 1 (25.0) | |

| Grade IV | 1 (2.6) | 1 (25.0) | |

| Preop opioid use in past 1 month | |||

| Yes | 2 (5.3) | 1 (25.0) | 0.265 |

| No | 36 (94.7) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Cadre of surgeon | |||

| Senior registrar | 9 (23.7) | 3 (75.0) | 0.063 |

| Consultant | 29 (76.3) | 1 (25.0) | |

BMI = body mass index, ASA = American Society of Anaesthesiologists

Similarly, there was no association between the duration of surgery, intraoperative blood loss, intraoperative fluid administration and prolonged postoperative ileus as shown in Table 4b. However, prolonged postoperative ileus was associated with longer duration of nasogastric tube use (P = 0.028) with those who developed prolonged postoperative ileus being on nasogastric tube for a median duration of 5 days (IQR = 2.5 days), whereas those without prolonged ileus were on nasogastric tube for 4 days (IQR= 2 days).

Table 4b.

Numerical factors associated with prolonged postop ileus

| Prolonged postop ileus | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Duration of surgery (min) | 113 (79) | 120 (64) | 0.831 |

| Duration of use of NGT (days) | 4 (2) | 5 (3) | 0.028 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (millilitres) | 325 (475) | 250 (225) | 0.473 |

| Intraoperative fluid administration (litres) | 2.3 (0.9) | 2.0 (0.9) | 0.950 |

NGT = nasogastric tube

The effect of gum-chewing and parenteral metoclopramide on postoperative ileus

The effect of gum-chewing and parenteral metoclopramide on the duration of postoperative outcomes is shown in Table 5. The time to passage of first flatus was 3 days (IQR = 2), 2.5 days (IQR = 3.3), 4 days (IQR = 1.5) and 3 days (IQR = 2) in the GM, G, M, and C groups, respectively. Although patients in the gum group spent the least time to passage of first flatus, there was no statistically significant difference in the time to passage of flatus between the groups (P = 0.333). Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference in the time to passage of stool between the groups (P = 0.677).

Table 5.

Effect of gum-chewing and parenteral metoclopramide on time to postop outcomes*

| GM group (n = 18) | G group (n = 10) | M group (n = 13) | C group (n = 12) | Total (n = 53) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to first flatus | 3 (2) | 2.5 (3.3) | 4 (1.5) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 0.333 |

| Time to first stool | 4 (4) | 5.5 (2.3) | 4.5 (3.5) | 4 (3.5) | 4 (2) | 0.677 |

| Time to first bowel sound | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.5) | 2.5 (2.30 | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 0.677 |

| Time to NGT removal | 4 (2.5) | 4 (2) | 5 (2.3) | 4 (2) | 4 (1) | 0.108 |

| Duration of postoperative ileus | 3 (2) | 2.5 (3.3) | 4 (1.5) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 0.317 |

| Time to tolerance of solid/normal diet | 5 (2.5) | 6 (3) | 7 (2) | 6 (3) | 6 (2) | 0.483 |

| Duration of hospital stay | 7 (4) | 6.5 (8) | 9 (3) | 7 (2) | 7 (3) | 0.143 |

NGT = nasogastric tube

*All time measured in days

The median duration of postoperative ileus was 3 days (IQR = 2). A statistically significant difference was neither found in the duration of postoperative ileus (P = 0.317) nor in the duration of hospital stay (P = 0.143) between the study groups. Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference in the time to first bowel sound, time to tolerance of solid diet and time to nasogastric tube removal between the groups. There was no statistically significant difference in the duration of postoperative ileus by age, gender, BMI, ASA grade, and cadre of surgeon.

Discussion

Postoperative ileus is an inevitable sequela of abdominal surgeries and is a key determinant of how soon a patient goes home following abdominal surgery. Measures to enhance patient recovery and early discharge are a welcome development in low resource centres where undesirable postoperative outcomes, including prolonged hospital stay, tasks not only the patients paying out-of-pocket, but inflicts additional burden on the healthcare system. In this study, the goal was to determine whether combining chewing of gum and use of parenteral metoclopramide had an effect on the duration of postoperative ileus after elective abdominal surgery among adult patients that presented to our institution.

The demographic profile of the study participants showed female preponderance (M: F = 1:1.7) and a mean age of 51.9 ± 14.9 years. This may be due to the fact that females presented more with the more common surgical conditions seen in this study. Large bowel tumours which accounted for most of the diagnoses occurred in females than males (67% versus 33%). This may depict a changing pattern in the demography of large bowel tumours in the studied population. Previous studies in Ibadan on the pattern of colon and rectal tumours by Irabor et al.[26] showed a gradual shift from male preponderance to a nearly equal incidence in both sexes. Hitherto, large bowel tumours are known to occur more commonly in males in Nigeria.[27] The older age group of the patients in this study depicts the demographic pattern associated with the most common illnesses patients in this study presented with bowel tumour, obstructive jaundice and gastric tumour.

According to Shamim et al.[28] alimentary tract-based diseases constitute the commonest cause of seeking surgical care in a general surgery unit with the majority of patients presenting with nonspecific abdominal pain. Majority of our patients presented with abdominal pain with large bowel tumour, obstructive jaundice and gastric tumour as the common diagnosis. The distribution of elective cases in this study is similar to those by Adejumo et al.[29] in Gombe where gastrointestinal pathologies (colonic tumours, followed by gastric tumours) constituted the commonest indications for elective laparotomies followed by hepatobiliary pathologies (calculous cholecystitis, followed by obstructive jaundice). Tumours were seen in nearly half of the patients in this study and over a third of patients had a comorbidity, hypertension being the commonest. Patients with malignancies have been shown to have a high incidence of hypertension. Salako et al.[30] reported that comorbidities occurred in 26.9% of cancer patients presenting to two tertiary health facilities in Lagos with the most common being hypertension (20.4%), followed by diabetes (6.7%) and peptic ulcer disease (2.1%). The incidence of obesity in our study (9.8%) was well within the range for the general population in Nigeria (8.1–22.2%).[31] Although comorbidities were prevalent in our patients, these were controlled preoperatively and may, therefore, explain why most of them were in the ASA grades II and III.

The pattern of surgical procedures was in line with the profile of the patients’ disease conditions, the most frequent procedures being colectomy, followed by triple bypass and gastrectomy. Seventy-two percent of these procedures were performed by consultants. This may be due to the fact that most elective procedures are done in the daytime when consultant presence is higher and usually involve fairly stable patients that permit time for resident education by the consultants. Consultant presence has been known to be lower with emergency procedures. In all emergency general surgical cases done at a London teaching hospital, Faiz et al.[32] reported that a consultant was present in 36.2% of cases.

Not surprisingly, the ICU admission rate in this study was low (7.5%) as all procedures were elective in nature. Again, they were mostly done by a consultant surgeon and these patients were relatively stable and fit. Ileus is known to occur in 20%–50% of patients admitted to the ICU, may last up to 6.5 days, and is associated with longer ICU stay.[33] None of the 4 patients admitted in ICU in this study had prolonged ileus.

The review of 52 studies in 2013 by Vather et al.[34] leading to a definition of ‘normal’ ileus as ileus resolving before the four postoperative day and ‘prolonged’ ileus as ileus that resolves on or after the four postoperative day did not put into consideration, the differential resolution of postoperative ileus in open versus laparoscopic surgery. A postoperative ileus management council (PIMC) national experts’ clinical consensus panel, chaired by Delaney et al.[25] defined prolonged postoperative ileus as ileus lasting >5 days following laparotomy or greater than 3 days following laparoscopic surgery. The panel based this on the fact that resolution of postoperative ileus occurs in 65% of patients undergoing open abdominal surgery by the fifth postoperative day, whereas resolution of ileus in patients that underwent laparoscopic surgery occurs by the third postoperative day in approximately 70% of patients. In this study (and using the above definition by Delaney et al.), 9.4% of patients had prolonged postoperative ileus with no statistically significant difference in the incidence of prolonged postoperative ileus between the study groups. There is a wide variation in the reported incidence of prolonged postoperative ileus and this is influenced by the definition used for prolonged ileus, the type of surgery and access (laparoscopic vs open) and the duration of surgery, according to Wolthuis et al.[35] in a meta-analysis that revealed an incidence of 10.2% (RCTs) and 10.3% (non-RCTs) for prolonged postoperative ileus.

Perioperative factors such as age, gender, comorbidity status, history of smoking/ alcohol use, BMI, ASA grade, preoperative opioid use, cadre of surgeon, duration of surgery, EBL, and intraoperative fluid administration had no statistically significant association with prolonged postoperative ileus in this study. Liang et al.[36] reported that although there was no association between gender, BMI, duration of surgery, and EBL, factors such as open surgery, late-stage disease, low level of postoperative albumin and serum potassium, and older age were identified as risk factors for prolonged postoperative ileus in patients undergoing both open and laparoscopic surgery for gastric cancer. Notably, all of the five patients with prolonged postoperative ileus in this study were aged 55 years and above. Quiroga-Centeno et al.[37] in a systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for prolonged postoperative ileus found that the mean age of patients with prolonged postoperative ileus was significantly higher than that of the patients with no prolonged ileus.

In this study, there was a statistically significant association between the duration of nasogastric tube use and prolonged postoperative ileus (P = 0.003) with those who developed prolonged postoperative ileus being on nasogastric tube for 5 days, whereas those without prolonged ileus were on nasogastric tube for 4 days. The routine use of nasogastric tube following abdominal surgeries is increasingly being jettisoned following the stipulations captured in the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol which advocates for some perioperative measures including selective nasogastric tube use in the postoperative period. This practice has–among other benefits–been shown to protect patients from prolonged postoperative ileus.[38] A study by Grass et al.[39] reported that minimally invasive surgery and compliance of >70% to the ERAS protocol were independent protective factors for postoperative ileus.

Noble et al.[40] performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs that investigated the benefits of chewing gum after abdominal surgery. Chewing gum was associated with a reduction in time to flatus by 14 h and time to bowel movement by 23 h with a reduction in the length of hospital stay by 1.1 days. In this study, patients who chewed gum passed flatus 0.5 days (12 h) earlier with a reduction in the length of hospital stay by 0.5 days compared to controls. These findings were similar to the systematic review by Chan and Law of studies comparing chewing gum to standard postoperative care to shorten postoperative ileus after colorectal resection. Chan and Law [41] found that with combined standard postoperative care and gum-chewing, the patients passed flatus 24.3% earlier (weighted mean difference, –20.8 h; P = 0.0006) and had bowel movement 32.7% earlier (weighted mean difference, –33.3 h; P = 0.0002). They were discharged 17.6% earlier than those having ordinary postoperative treatment (weighted mean difference, –2.4 days; P < 0.00001).

Available studies on multimodal regimen for prevention and treatment of postoperative ileus centre on the combination of an intervention (either a pharmacologic agent like Alvimopan or a non-pharmacologic intervention like acupuncture) with the ERAS regimen. Studies on the combined effect of chewing gum and parenteral metoclopramide are scarce. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining the combined effect of Alvimopan (a selective and peripheral µ-opioid receptor antagonist) and the ERAS protocol on postoperative ileus after open abdominal surgery by Xu et al.[42] showed accelerated recovery of gastrointestinal function, shortened length of hospital stay and reduced postoperative ileus-related morbidity.

This study found no statistically significant difference in the time to first bowel sound, time to passage of flatus, time to passage of faeces, time to tolerance of solid diet, time to nasogastric tube removal, mean duration of postoperative ileus and length of hospital stay between the study groups. In terms of other postoperative outcomes, the combined use of gum and parenteral metoclopramide did not show superior result compared to other study groups. Patients in the gum group however showed better postoperative outcomes in numerical terms, although these findings were not statistically significant.

A study by Ilesanmi and Fatiregun[43] revealed that an increase of 1 day in the duration of hospital stay among surgical inpatients at the UCH, Ibadan increased cost of care by ₦2372.57K. Patients in the M group spent approximately 2 days longer than controls in this study. It is therefore, not surprising that they spent nearly ₦2400 more than controls on the cost of bed fee.

This study is not without limitations. First, as patients may have passed flatus earlier than it was noted (e.g. during sleep), the time to passage of flatus could not have been reliably measured. However, this bias is not limited to any of the groups in this study but cuts across all patients. The second limitation is the small sample size across the study groups which may not sufficiently power a reliable analysis.

Based on the findings of this study, it is recommended that the use of nasogastric tube in the postoperative period should be selective to prevent prolonged postoperative ileus.

Conclusion

The combined use of gum-chewing and parenteral metoclopramide had no effect on either the duration of postoperative ileus or the duration of hospital stay following elective abdominal surgeries in adult surgical patients. However, the use of gum alone appears to show some promise. A randomised controlled study to further validate the effect of gum-chewing on postoperative ileus may be considered.

Registration number/name of registry/URL

NCT05669781/ ClinicalTrials.gov/ https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home.

Authors’ contribution

IBU contributed to study conceptualisation, study design, literature search, data acquisition, data analysis and manuscript preparation. OOA, OOA, AF and DOI all contributed to the study design, manuscript editing and final manuscript review.

Authors’ statement

The authors declare that this manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors, that the requirements for authorship as stated earlier in this document have been met, and that each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have any personal interest/gain that may affect the unbiased conduct, results and presentation of this study to declare.

References

- 1.Michael DJ, Matthew RW. Current therapies to shorten postoperative ileus. Clev Clin J Med. 2009;76:641–8. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76a.09051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farhad Z, Jonah J, Conor P. Pharmacological management of postoperative ileus. Can J Surg. 2009;52:153–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carroll J, Alavi K. Pathogenesis and management of postoperative ileus. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2009;22:47–50. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1202886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Story SK, Chamberlain RS. A comprehensive review of evidence-based strategies to prevent and treat postoperative ileus. Dig Surg. 2009;26:265–75. doi: 10.1159/000227765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tu CP, Tsai CH, Tsai CC, Huang TS, Cheng SP, Liu TP. Postoperative ileus in the elderly. Int J Gerontol. 2014;8:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juárez-Parra MA, Carmona-Cantú J, González-Cano JR, Arana-Garza S, Trevi˜no-Frutos RJ. Risk factors associated with prolonged postoperative ileus after elective colon resection. Revista de Gastroenterología de México. 2015;80:260–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rgmx.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffmann H, Kettelhack C. Fast-track surgery–conditions and challenges in postsurgical treatment: A review of elements of translational research in enhanced recovery after surgery. Eur Surg Res. 2012;49:24–34. doi: 10.1159/000339859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedziwiatr M, Kisialeuski M, Wierdak M, Stanek M, Natkaniec M, Matłok M, et al. Early implementation of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol compliance improves outcomes: A prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2015;21:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.06.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao Y, Qin H, Wu Y, Xiang B. Enhanced recovery after surgery program reduces length of hospital stay and complications in liver resection A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e7628. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Traut U, Brügger L, Kunz R, Pauli-Magnus C, Haug K, Bucher H, et al. Systemic prokinetic pharmacologic treatment for postoperative adynamic ileus following abdominal surgery in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD004930. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004930.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fesharakizadeh M, Taheri D, Dolatkhah S, Wexner SD. Postoperative ileus in colorectal surgery: Is there any difference between laparoscopic and open surgery? Gastroenterol Rep. 2013;2013:138–43. doi: 10.1093/gastro/got008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tintim C, Machado HS. Enhanced recovery after surgery pathway: How its implementation influenced digestive surgery outcomes? J Anesth Clin Res. 2017;8:730. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abantanga FA. Nasogastric tube use in children after abdominal surgery: How long should it be kept in situ? West Afr J Med. 2012;31:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balayla J, Bujold E, Lapensée L, Mayrand M, Sansregret A. Early versus delayed postoperative feeding after major gynaecological surgery and its effects on clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, and length of stay: A randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37:1079–85. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saclarides TJ. Current choices—good or bad—for the proactive management of postoperative ileus: A surgeon’s view. J Perianesth Nurs. 2006;21:S7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Bree SH, Nemethova A, Cailotto C, Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Matteoli G, Boeckxstaens GE. New therapeutic strategies for postoperative ileus. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:675–83. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nair A. Alvimopan for post-operative ileus: What we should know? Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2016;54:97–8. doi: 10.1016/j.aat.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ge W, Chen G, Ding Y. Effect of chewing gum on the postoperative recovery of gastrointestinal function. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:11936–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shigemi D, Nakanishi K, Miyazaki M, Shibata Y, Suzuki S. The effect of the gelatinous lactulose for postoperative bowel movement in the patients undergoing cesarean section. Int Sch Res Notices. 2014;2014:1–4. doi: 10.1155/2014/752862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ngowe MN, Eyenga VC, Kengne BH, Bahebeck J, Sosso AM. Chewing gum reduces postoperative ileus after open appendectomy. Acta Chir Belg. 2010;110:195–9. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2010.11680596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ajuzieogu OV, Amucheazi A, Ezike HA, Achi J, Abam DS. The efficacy of chewing gum on postoperative ileus following cesarean section in Enugu, South East Nigeria: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Niger Clin Pract. 2014;17:739–42. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.144388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terzioglu F, Şimsek S, Karaca K, Sariince N, Altunsoy P, Salman MC. Multimodal interventions (chewing gum, early oral hydration and early mobilisation) on the intestinal motility following abdominal gynaecologic surgery. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:1917–25. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ko-iam W, Sandhu T, Paiboonworacha S, Pongchairerks P, Chotirosniramit A, Chotirosniramit N, et al. Predictive factors for a long hospital stay in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Int J Hepatol. 2017;3:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2017/5497936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clardull A, Saccone G, Di Masco D, Caissutti C, Berghella V. Chewing gum improves postoperative recover of gastrointestinal function after cesarean delivery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;6:1–9. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1330883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delaney C, Kehlet H, Senagore AJ, Bauer AJ, Beart R, Billingham R, et al. Postoperative ileus: Profiles, risk factors, and definitions––a framework for optimizing surgical outcomes in patients undergoing major abdominal colorectal surgery. In: Bosker G, editor. Clinical Consensus Update in General Surgery. Roswell (GA): Pharmatecture, LLC; 2006. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irabor DO, Arowolo A, Afolabi AA. Colon and rectal cancer in Ibadan, Nigeria: An update. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12:43–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holowatyj AN, Maude AS, Musa HS, Adamu A, Ibrahim S, Abdullahi A, et al. Patterns of early-onset colorectal cancer among Nigerians and African Americans. J Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1647–55. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shamim M, Bano S, Iqbal SA. Pattern of cases and its management in a general surgery unit of a rural teaching institution. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62:148–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adejumo AA, Nuhu M, Afolaranmi T. Incidence of and risk factors for abdominal surgical site infection in a Nigerian tertiary care centre. Int J Infect Control. 2015;11:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salako O, Okediji PT, Habeebu MY, Fatiregun OA, Awofeso OM, Okunade KS, et al. The pattern of comorbidities in cancer patients in Lagos, south-Western Nigeria. Ecancer. 2018;12:1–12. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2018.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chukwuonye II, Chuku A, John C, Ohagwu KA, Imoh ME, Isa SE, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in adult Nigerians: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab Syndr. Obes.: Targets Ther. 2013;6:43–7. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S38626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faiz O, Banerjee S, Tekkis P, Papagrigoriadis S, Rennie J, Leather A. We still operate at night! World J Emerg Surg. 2007;2:29–65. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-2-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vazquez-Sandoval A, Ghamande S, Surani S. Critically ill patients and gut motility: Are we addressing it? World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2017;8:174–9. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i3.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vather R, Trivedi S, Bissett I. Defining postoperative ileus: Results of a systematic review and global survey. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:962–72. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2148-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolthuis AM, Bislenghi G, Fieuws S, Overstraeten A, Boeckxstaens G, D’Hoore A. Incidence of prolonged post-operative ileus after colorectal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2015; 18:1–9. doi: 10.1111/codi.13210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang W, Li J, Zhang W, Liu J, Li M, Gao Y, et al. Prolonged post-operative ileus in gastric surgery: Is there any difference between laparoscopic and open surgery? Cancer Med. 2019;8:5515–23. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quiroga-Centeno AC, Jerez-Torra KA, Martin-Mojica PA, Castañeda-Alfonso SA, Castillo-Sánchez ME, Calvo-Corredor OF, et al. Risk factors for prolonged postoperative ileus in colorectal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2020;44:1612–26. doi: 10.1007/s00268-019-05366-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barbieux J, Hamy A, Talbot MF, Casa C, Mucci S, Lermite E, et al. Does enhanced recovery reduce post-operative ileus after colorectal surgery? J Visc Surg. 2017;154:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grass F, Slicker J, Jurt J, Kummer A, Sola J, Hahnloser D, et al. Postoperative ileus in an enhanced recovery pathway: A retrospective cohort study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:675–81. doi: 10.1007/s00384-017-2789-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noble EJ, Harris R, Hosie KB, Thomas S, Lewis SJ. Gum chewing reduces postoperative ileus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2009;7:100–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan MK, Law WL. Use of chewing gum in reducing postoperative ileus after elective colorectal resection: A systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:2149–57. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu L, Zhou X, Yi P, Zhang M, Li J, Xu M. Alvimopan combined with enhanced recovery strategy for managing post-operative ileus after open abdominal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Surg Res. 2016;203:211–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ilesanmi OS, Fatiregun AA. The direct cost of care among surgical inpatients at a tertiary hospital in south West Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;18:1–8. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.3.3177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]