Abstract

Covalent modification of lipid A with 4-deoxy-4-amino-L-arabinose (Ara4N) mediates resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides and polymyxin antibiotics in Gram-negative bacteria. The proteins required for Ara4N biosynthesis are encoded in the pmrE and arnBCADTEF loci, with ArnT ultimately transferring the amino sugar from undecaprenyl-phospho-4-deoxy-4-amino-L-arabinose (C55P-Ara4N) to lipid A. However, Ara4N is N-formylated prior to its transfer to undecaprenyl-phosphate by ArnC, requiring a deformylase activity downstream in the pathway to generate the final C55P-Ara4N donor. Here, we show that deletion of the arnD gene in an Escherichia coli mutant that constitutively expresses the arnBCADTEF operon leads to accumulation of the formylated ArnC product, undecaprenyl-phospho-4-deoxy-4-formamido-L-arabinose (C55P-Ara4FN), suggesting that ArnD is the downstream deformylase. Purification of Salmonella Typhimurium ArnD (stArnD) shows it is membrane associated. We present the crystal structure of stArnD revealing a NodB homology domain structure characteristic of the metal-dependent carbohydrate esterase family 4 (CE4). However, ArnD displays several distinct features: a 44 amino acid insertion, a C-terminal extension in the NodB fold, and sequence divergence in the five motifs that define the CE4 family, suggesting that ArnD represents a new family of carbohydrate esterases. The insertion is responsible for membrane association as its deletion results in a soluble ArnD variant. The active site retains a metal coordination H-H-D triad and, in the presence of Co2+ or Mn2+, purified stArnD efficiently deformylates C55P-Ara4FN confirming its role in Ara4N biosynthesis. Mutations D9N and H233Y completely inactivate stArnD implicating these two residues in a metal-assisted acid-base catalytic mechanism.

Keywords: antibiotic resistance, enzyme structure, enzyme mechanism, polymyxin, lipid A modification

Introduction

Lipid A is the conserved, membrane embedded component of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that constitutes the outer leaflet of the outer membrane in diderm bacteria. Cationic antimicrobial peptides of the innate immune system as well as related antibiotics such as polymyxin B and colistin (polymyxin E), electrostatically interact with negatively charged phosphate groups in lipid A as the initial step of their antimicrobial mechanism. However, environmental conditions, such as low pH or low Mg2+, or bacterial exposure to cationic antimicrobial peptides, can trigger lipid A modification with cationic moieties that reduce antimicrobial binding leading to resistance1, 2. One of the most common modifications is the addition of 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose (Ara4N) to phosphate groups in lipid A (SI Fig. S1), which reduces its net charge from −1.5 to 01–3. Ara4N can be present in more than 85% of LPS molecules4 and the less negatively charged cell surface impairs binding of CAMPs causing resistance5, 6. The second most common modification is the addition of phosphoethanolamine (pEtN) to phosphate groups of lipid A (SI Fig. S1). As this reduces lipid A net charge from −1.5 to −1, it is less effective than Ara4N at reducing colistin binding2, 3.

Addition of Ara4N to lipid A is controlled by the PmrA/PmrB and PhoP/PhoQ two-component regulatory systems7, 8. Activation of PmrA results in transcription of pmrE(ugd) and the arnBCADTEF operon (previously known as pmrHFIJKLM) encoding the enzymes responsible for lipid A modification with Ara4N and polymyxin resistance9–11. Constitutively active pmrA (pmrAc) mutants of E. coli and Salmonella Typhimurium are thus polymyxin resistant4, 12, 13. All the gene products of pmrE and the arnBCADTEF are essential for resistance as non-polar inactivation of any one of those genes results in loss of Ara4N-lipid A modification and polymyxin resistance in pmrAc cells9–11, 14.

The pathway for synthesis of Ara4N and its attachment to lipid A begins with UDP-Glucose and its conversion to UDP-Ara4N by the successive action of Ugd (PmrE), the C-terminal domain of ArnA and ArnB (SI Fig. S2). The nucleotide-linked amino sugar is then formylated at the 4’ nitrogen to yield UDP-L-AraN-formyl (UDP-Ara4FN) in a reaction catalyzed by the N-terminal domain of ArnA. As no Ara4FN has been detected attached to lipid A, the reason for an apparently transient N-formylation was puzzling. However, Breazeale and coworkers have suggested that formylation of UDP-Ara4N compensates for the unfavorable equilibrium constant observed for the conversion of UDP-4-ketopentose to UDP-Ara4N, thereby displacing the reaction in the forward direction of the pathway15. ArnC then transfers the formylated amino-sugar to undecaprenyl-phosphate (C55P) to yield undecaprenyl-phospho-4-deoxy-4-formamido-L-arabinose (C55P-Ara4FN) with release of UDP16. Based on weak sequence similarity with polysaccharide deacetylases, the gene product of arnD was proposed to deformylate the intermediate C55P-Ara4FN16, and ArnD from Burkholderia cenocepacia has been reported to slowly deformylate chemically synthesized neryl-phosphate-L-Ara4FN (C10P-Ara4FN), only after a 20 hour incubation17. Deformylation of C55P-Ara4FN to yield undecaprenyl-phospho-4-deoxy-4-amino-L-arabinose (C55P-Ara4N) is essential for the lipid A modification as this intermediate is flipped to the periplasmic side of the inner membrane by the heterodimeric ArnE/ArnF14, 16 before transfer of the Ara4N to lipid A is catalyzed by the transmembrane protein ArnT18–20.

Here, we show that polymyxin resistant E. coli pmrAc accumulates the amino sugar donor C55P-Ara4N required for lipid A modification with Ara4N. However, deletion of arnD (pmrAc ΔarnD) results in accumulation of the formylated intermediate C55P-Ara4FN indicating that ArnD is responsible for deformylating the ArnC product in cells. We present the crystal structure of ArnD from Salmonella Typhimurium and identify conserved structural motifs that define these proteins as a new family of membrane associated carbohydrate esterases. Structure analysis also reveals a conserved membrane interaction finger in ArnD that mediates the peripheral membrane association of the protein. Reconstitution of the purified ArnD activity in vitro shows efficient deformylation of C55P-[14C]Ara4FN as well as the ten carbon diprenol derivative neryl-P-L-[14C]Ara4FN in the presence of Co2+ or Mn2+. Furthermore, mutation of conserved aspartate and histidine amino acids in the active site render the enzyme inactive implicating these residues in a metal-assisted, acid-based catalyzed reaction mechanism. The unambiguous demonstration of the role of ArnD in lipid A modification with Ara4N and polymyxin resistance as well as the structural and in vitro functional characterization of the enzyme, will facilitate specific inhibition studies that may be used to combat polymyxin resistance in Gram-negative pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Construction of a pmrAc mutant of E. coli K-12 with chromosomal insertions in arn genes.

Using a pmrAc variant of E. coli strain DY-330 designated MST10016, we took advantage of λ-RED-mediated recombination, to make a non-polar insertion of a kanamycin resistance gene (kan, aminoglycoside 3’-phosphotransferase) into the arnD gene located in the arnBCADTEF operon. A linear DNA fragment in which the kan gene is flanked by 44 bp located directly upstream of arnD (underlined sequence in DKanKO5) and a ribosomal binding site with an NdeI site (double underlined in DKanKO3) site, followed by 45 bp located directly downstream of arnD (underlined in DKanKO3) was amplified using the oligonucleotides DKanKO3 (5’-gcaggcaataaacgcgaagaggccgataaggtaacgtaccgatttcatatgtatatctccttcttagaaaaactcatcgagcat-3’), DKanKOK5 (5’–ctggatttcttcctgcgcaccgttgatcttacggataaaccatcatgaccaaaattcaacgggaaacgtcttgc- 3’) and the kanamycin resistance gene (Tn903) from plasmid pWSK130 as a template in a PCR reaction using Pfu polymerase. The PCR product was gel purified and 100 ng were introduced into strain MST100 by electroporation following induction of the RED system by incubation of mid-log-phase cells for 15 min at 42 °C. After growth for 2 h at 30 °C, the cells were plated on LB agar containing kanamycin grown overnight at 30 °C. The resulting strain pmrAc ΔarnD has the phenotype PmS, KanR, and only grows at 30 °C. The same approach was utilized to construct the pmrAc ΔarnC strain.

Lipid Extraction from E. coli Strains

The lipid extraction was performed using the method of Bligh-Dyer, essentially as previously described13. Briefly, 400-mL cultures of bacteria were grown to A600 = 2.0 and harvested by centrifugation at 6500 × g for 15 minutes at 4 °C. Cell pellets were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4 (50 mL). To extract the phospholipids, the cell pellet was resuspended in 19 mL of a single-phase Bligh/Dyer mixture, consisting of chloroform/methanol/water (1:2:0.8 v/v). After incubating for 60 minutes at room temperature, with mixing, the insoluble material was removed by centrifugation (4000 × g for 15 minutes at room temperature), and the lipids-containing supernatant was transferred to a clean tube. The supernatant was then converted to a two-phase Bligh/Dyer system consisting of chloroform/methanol/water (2:2:1.8, v/v). The phases were separated by low-speed centrifugation (4000 × g for 15 minutes at room temperature) and the lower phase was removed, and ultimately dried under a stream of N2.

Lipid analysis by electrospray ionization/mass spectrometry (ESI/MS)

All mass spectra were acquired on a QSTAR XL quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometer (ABI/MDS-Sciex, Toronto, Canada), equipped with an electrospray ionization source. Spectra were acquired in the negative ion mode and were typically the accumulation of 60 scans, collected from 200 to 2000 atomic mass units. Lipid extracts from the E. coli strains were resuspended in 100 μL of CHCl3/MeOH (2:1, v/v) and 20 μL of this solution were diluted with 180 μL of CHCl3/MeOH (1:1, v/v) and infused into the ion source at 5–10 μl/min. For the MST100 pmrAc strain sample, 2 μL of piperidine were added to the solution to enhance the production of negatively charged, deprotonated [M-H]− ion signals from neutral species. The negative ion analysis was carried out at −4200 V. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using Analyst QS software.

Cloning and expression and purification of stArnD.

The gene for Salmonella Typhimurium ArnD (stArnD, Uniprot: O52326) was PCR amplified from genomic DNA with a sense primer incorporating an NdeI restriction site at the start ATG codon, and an antisense primer coding for an hexahistidine tag immediately after the last codon followed by a stop codon and an XmaI restriction site. The PCR product was purified, digested with NdeI and XmaI (New England BioLabs) and ligated into an engineered pET28 vector digested with the same enzymes, resulting in the ArnD expression plasmid pMS1337. E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells (Invitrogen) were transformed with pMS1337, and a single colony used to inoculate 100 mL of Luria Broth (LB) media supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin. The culture was incubated overnight at 37 °C and used to inoculate 4 x 1 L of LB media supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin. The cells were grown at 37°C until the OD600 = 0.6. The cultures were then cooled down on ice before adding IPTG (final concentration 0.5 mM) to induce protein expression. The cultures were then incubated overnight at room temperature with shaking. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000 rpm (JLA 8.1000 rotor) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 50 mL of lysis buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME), lysozyme 0.5 mg/mL and 1 EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche). The cells were lysed by 3 to 4 passes through an Avestin Emulsiflex C3 unit followed by removal of cell debris by centrifugation at 15000 rpm (Sorvall SS-34 rotor) for 30 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 50000 rpm (Beckman fixed-angle Titanium rotor Type 70) for 2 hours at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the membrane pellet resuspended in lysis buffer without lysozyme, supplemented with n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltopyranoside (DDM, Anatrace) to a final concentration of 1% (w/v) and homogenized in a Dounce homogenizer. The homogenate was incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle rocking to extract ArnD. The suspension was then ultracentrifuged at 50000 rpm (Type-70Ti) for 1 hour at 4°C and the insoluble pellet discarded. The supernatant was loaded to a 5 mL HisTrap FF Ni-NTA column (Cytiva) equilibrated in 25 mM Tris-Base pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mM BME and 0.023% (w/v) DDM. The column was washed with 5 column volumes of the above buffer supplemented with 5 mM imidazole and the elution was achieved by increasing the imidazole concentration to 300 mM during a five-column volume linear gradient. Fractions containing ArnD, as evaluated by SDS-PAGE, were pooled, loaded in a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) column equilibrated in 25 mM Tris-Base pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mM BME, 1 mM EDTA and 0.02% (w/v) DDM and eluted in the same buffer. Fractions containing ArnD, as detected by SDS-PAGE, were pooled and concentrated to 13 mg/mL using a 100k MWCO centrifugal filter unit. Protein stocks were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80°C for further use.

Cloning, expression, and purification of ArnD mutants.

Point mutations D9N and H233Y in the gene for stArnD were introduced in the pMS 1337 plasmid using a variation of the QuikChange protocol21 and primers 5’-cgcattaatgttgataccttgcgaggaacg-3’ and 5’-atcaacattaatgcgtaaaccgactttcgtcatatg-3’ for D9N, and 5’-gtatataccatctacgcggaagtagaaggtattgtccatcag-3’ and 5’-cgcgtagatggtatataccggcgtgcctttgt-3’ for H233Y. The same PCR-based protocol was utilized to replace the coding sequence for amino acids 44–82 for a glycine, or a glycine and a cysteine in the deletions del-G and del-GC, respectively. Primer pairs for del-G and del-GC mutants were 5’-gccggacggaggaaaaaatatcggcaacgctaatgccg-3’, 5’-ttttttcctccgtccggcccgacgctgaagaaaaagctgg-3’ and 5’-ccggacggatgtggaaaaaatatcggcaacgctaatgccg-3’, 5’-tttttccacatccgtccggcccgacgctgaagaaaaagctg-3’, respectively.

ArnD point mutants D9N and H233Y were expressed and purified as described above for the wild-type protein. For the ArnD deletions del-G and del-GC, the plasmids were introduced in chemically competent E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells and single colonies from an overnight cultured plate used to inoculate a starter culture in LB media supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin, which was then incubated at 37°C overnight. The starter culture was used to inoculate 1 L of LB media supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin. The cells were grown at 37°C until the OD600 = 0.6. The cultures were then cooled down on ice before adding IPTG (final concentration 0.1 mM) to induce protein expression. The cultures were then incubated overnight at room temperature with shaking. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4000 rpm (JLA 8.1000 rotor) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 50 mL of lysis buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME), lysozyme 0.5 mg/mL and 1 EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche). The cells were lysed by 3 to 4 passes through an Avestin Emulsiflex C3 unit followed by removal of cell debris by centrifugation at 15000 rpm (Sorvall SS-34 rotor) for 30 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 50000 rpm (Beckman fixed-angle Titanium rotor Type 70) for 2 hours at 4°C. An SDS-PAGE of the supernatant and pellet fractions revealed that del-G and del-CG proteins fractionated with the soluble fraction (supernatant) rather than the membranes (pellet). The pellet was then discarded, and the supernatant loaded on a 5 mL HisTrap FF Ni-NTA column (Cytiva) equilibrated in 25 mM Tris-Base pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mM BME. The column was washed with 5 column volumes of the above buffer supplemented with 5 mM imidazole and the elution was achieved by increasing the imidazole concentration to 300 mM during a five-column volume linear gradient. Fractions containing ArnD, as evaluated by SDS-PAGE, were pooled, loaded in a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) column equilibrated in 25 mM Tris-Base pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 5 mM BME, 1 mM EDTA and eluted in the same buffer. Fractions containing ArnD as detected by SDS-PAGE were pooled and concentrated to 18 mg/mL for del-G and 15 mg/mL for del-GC using a 10k MWCO centrifugal filter unit. Protein stocks were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80°C for further use.

ArnD crystallization, x-ray data collection, and structure determination

Crystals of ArnD were obtained by mixing 2 μL of a stock solution of ArnD (6 mg/mL) in 25mM Tris-HCl, pH8.0, 150mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 5mM BME, 0.0174% DDM, with 2 μL of a precipitant solution containing 0.1M Na citrate pH 6.2, 10% isopropanol and 17% PEG4000 and allowing vapor diffusion between the protein droplet and a 1mL reservoir of precipitant in a hanging drop set up incubated at 16 °C. Small crystals formed after 3–6 days, and they were harvested, and flash frozen in a stream of nitrogen (100 °K) prior to x-ray data collection. A dataset was collected at beam line 8.2.2 of the Advanced Light Source of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which showed anisotropic diffraction to 2.6Å resolution. Data were indexed, integrated and scaled using HKL200022. Data collection statistics are shown in SI, Table S1.

The crystals belonged to space group I222 with unit cell dimensions a = 82.55, b = 85.65, c = 111.91 Å suggesting one ArnD molecule per asymmetric unit. The structure was determined by molecular replacement using Phaser as implemented in the Phenix program suite23, 24. The search model was produced by Dr. Kathryn Tunyasuvunakool, senior scientist at DeepMind, using AlphaFold2. The model was trimmed by removing the regions with residues with higher error estimates which included residues 44–84, 184–186, 201–208, 225–226 and 283–288. Rotation and translation searches using the trimmed model resulted in a single unambiguous solution. Rigid body refinement of the solution yielded a crystallographic Rfree of 0.331 and inspection of the electron density maps revealed good density for most of the missing regions in the model confirming the correctness of the molecular replacement solution. The model was improved through alternating cycles of positional and B factor refinement in Phenix, and manual rebuilding using Coot25, 26. Refinement statistics for the final model are shown in SI Table S1.

Enzymatic synthesis of undecaprenyl-phospho-L-[14C]Ara4FN (C55P-[14C]Ara4FN)

Since the ArnD substrate, C55P-Ara4FN, is not commercially available, its synthesis was carried out by sequential enzymatic conversion of UDP-glucuronic acid into C55P-Ara4FN using purified ArnA, ArnB and ArnC. Full-length E. coli ArnA and ArnB were expressed and purified as described27, 28. Salmonella ArnC was cloned, expressed in E. coli, and purified using the same protocol described above for Salmonella ArnD. To obtain a radioactively labeled substrate, conversion of UDP-[14C]-glucuronic acid to UDP-L-[14C]-Ara4N was achieved preparing a 50 μL reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-Base pH 8.0, 10 mM BME, 6 mM NAD+ and 12 μM UDP-[14C]-glucuronic acid (Perkin Elmer, uniformly labeled with [14C] in the glucuronic acid, specific activity: 313 mCi/mmol), and mixing it with an equal volume of a solution containing 100 mM Glutamic acid pH 7.0, and the enzymes ArnA 0.3 mg/mL and ArnB 0.5 mg/mL. After a 3 hour incubation at room temperature, the reaction mixture was mixed with an equal volume of a solution containing 2 mM N10-formyl-tetrahydrofolate, freshly prepared from N-5-formyltetrahydrofolate (Sigma) as previously described29, to obtain the formylated amino sugar nucleotide UDP-L-[14C]Ara4FN. The reaction progress was followed by spotting 1 μL of each reaction mixture on a polyethylenimine (PEI) cellulose plate developed in a solvent system containing 0.25 M acetic acid and 0.4 M LiCl29 and visualizing radioactive spots. The final mixture was filtered through a 30k MWCO centrifugal unit to remove the enzymes. To transfer the formylated sugar [14C]Ara4FN to a lipid acceptor, the filtered reaction mixture was supplemented with ArnC reaction components so that the final concentrations were: 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 0.2 mM MnCl2, 0.2% (w/v) DDM, purified ArnC 0.25 mg/mL and 0.1 mM undecaprenyl-phosphate (Larodan). The reaction was incubated at room temperature for 1 hour which results in complete transfer of [14C]Ara4FN to the lipid to yield C55P-[14C]Ara4FN, as evaluated by spotting 1 μL of the reaction on a silica plate developed in a solvent system consisting of chloroform/methanol/water/ammonium hydroxide in a ratio of 35/40/3.6/0.4 and visualizing radioactive spots.

ArnD in vitro reconstituted activity assays.

ArnD activity measurements were typically carried out in 10 μL reaction consisting of 5 μL the ArnC reaction described above containing C55P-[14C]Ara4FN and 5 μL of ArnD 0.5 mg/mL supplemented with the indicated metals or EDTA. The mixtures were incubated at room temperature for the indicated times and the reaction progress evaluated by spotting 1 μL of the mixture on a silica plate developed in chloroform/methanol/water/ammonium hydroxide in a ratio of 35/40/3.6/0.4. Radioactive spots were visualized by exposing the TLC plates to phosphorimager screens and reading them on a Typhoon scanner. The reactions comparing activity of wild-type ArnD and mutants D9N and H233Y were carried out as described above but the final protein concentration was 0.1 mg/mL.

Results

ArnD is responsible for deformylation of undecaprenyl-phospho-4formamido-4deoxy-L-arabinose in E. coli.

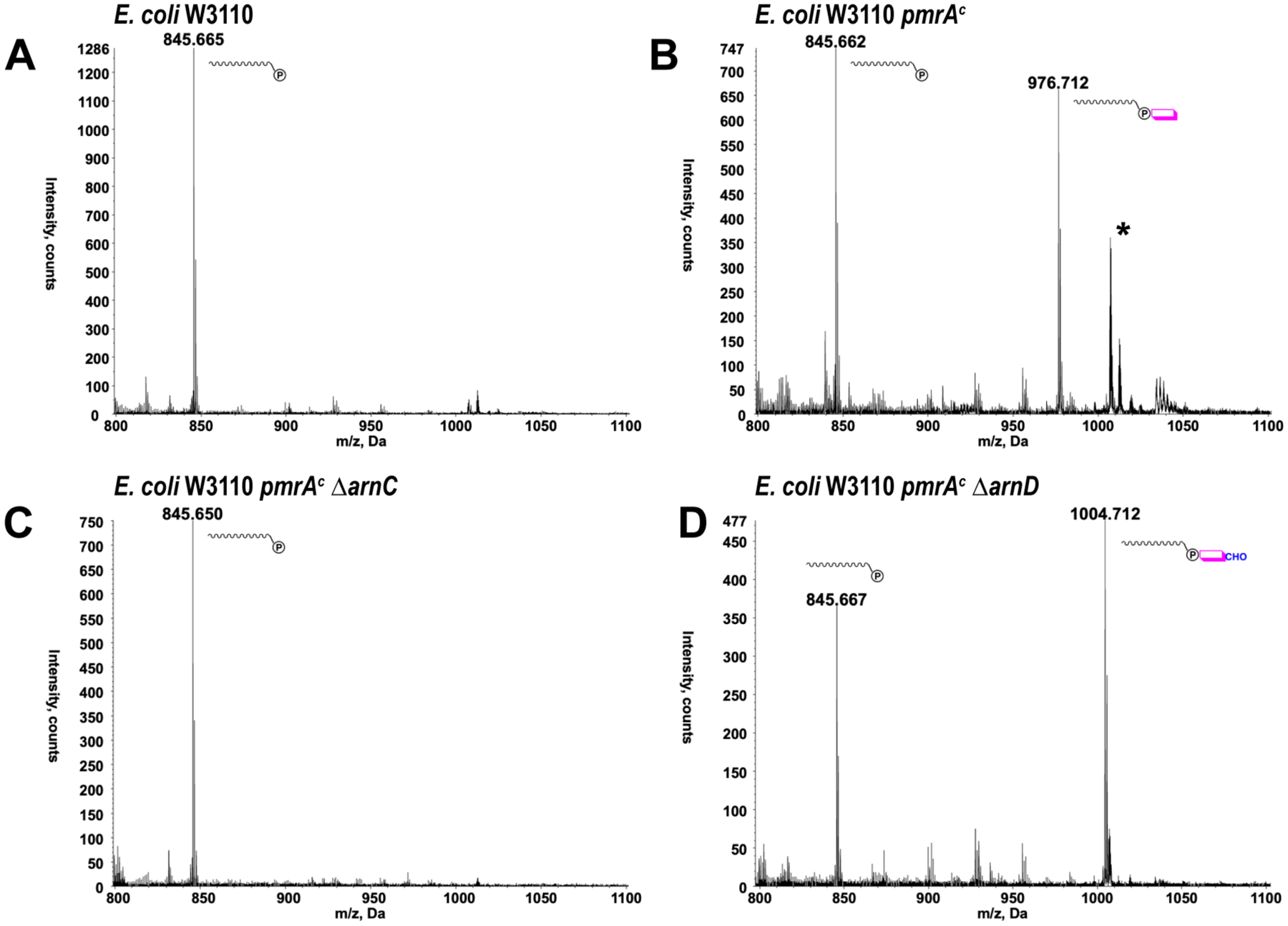

Polymyxin resistance in E. coli, S. Thyphimurium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae is primarily associated with lipid A modification with Ara4N as catalyzed by the integral membrane protein ArnT, which uses C55P-Ara4N as the donor substrate. However, in the pathway for biosynthesis of the ArnT substrate, ArnC efficiently transfers the formylated amino sugar 4-deoxy-4-formamido-L-Arabinose (Ara4FN) but not the unformylated 4-deoxy-4-amino-L-Arabinose from the UDP carrier to the undecaprenyl-phosphate intermediate to yield C55P-Ara4FN (SI Fig. S2 and S3). As the formylated amino sugar is not detected in lipid A a deformylation activity is required in the pathway. Based on weak sequence similarity to polysaccharide deacetylases, ArnD was proposed to catalyze the deformylation step. To test the involvement of ArnC and ArnD in the biosynthesis of C55P-sugar intermediates that lead to lipid A modification with Ara4N and polymyxin resistance in E. coli, phospholipids of polymyxin sensitive and resistant strains were analyzed by ESI/MS. As shown in Fig. 1A, only C55P [M-H]−ion at m/z 845.67 is detectable in the polymyxin sensitive E. coli reference strain W3110, consistent with non-expression of the arnBCADTEF operon under rich media growth conditions. Conversely, the polymyxin resistant E. coli pmrAc strain, carrying a pmrA mutation that results in constitutive expression of the Arn operon, displays both C55P and C55P-Ara4N [M-H]− ions at m/z 845.67 and 976.71 respectively (Fig. 1B). The spectrum also reveals the presence of a triply charged species (m/z 1007.2, labeled with an asterisk) that corresponds to CydH, a small subunit of the cytochrome bd-I oxidase often observed in Blight-Dyer extracts of E. coli30, 31 as well as its methionine oxidized derivative (m/z 1022.5). However, no C55P-Ara4N is observed, indicating that the formylated species is an intermediate in the pathway that does not accumulate. Deletion of the arnC gene in E. coli pmrAc (pmrAc ΔarnC) results in loss of C55P-Ara4N consistent with the role of ArnC in the transfer of Ara4FN from UDP to C55P (Fig. 1C). On the other hand, deletion of arnD (pmrAc ΔarnD) results in accumulation of the formylated intermediate C55P-Ara4FN shown in the spectrum at m/z 1004.71 (Fig. 1D) suggesting that ArnD is responsible for deformylating the ArnC product in E. coli cells.

Figure 1: Negative ion ESI/MS spectra of the undecaprenyl-phosphate sugars in E. coli strains.

Lipids extracted from E. coli strains were subjected to negative ion ESI/MS. Only regions of the spectra showing the [M-H]− ions of undecaprenyl-phosphate and undecaprenyl-phosphate sugars are shown. (A) Wild-type, polymyxin-sensitive, E. coli W3110. (B) polymyxin resistant E. coli W3110 pmrAc. (C) E. coli W3110 pmrAc ΔarnC. (D) E. coli W3110 pmrAc ΔarnD. The exact masses for C55P, C55P-Ara4N and C55P-Ara4FN are 846.665, 977.724 and 1005.719, respectively. The asterisk (*) denotes chloroform soluble CydH.

Crystal structure of ArnD from Salmonella Typhimurium

Multiple constructs of ArnD from E. coli, S. Typhimurium, P. aeruginosa, and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, with N- and C-terminal tags were expressed in E. coli and screened for purification and crystallization. Despite not having any predicted transmembrane regions, the proteins partitioned with the membrane fractions after cell lysis. Therefore, they were extracted and purified in the presence of detergents and screened for crystallization. Full length ArnD from Salmonella Typhimurium (stArnD) with a C-terminal hexahistidine tag yielded crystals amenable to x-ray diffraction analysis. The crystals belonged to space group I222 with one molecule per asymmetric unit. The crystal structure was determined by molecular replacement using an AlphaFold2 model and refined to 2.6 Å resolution as described in Materials and Methods. The final model comprises residues 1–297 with two breaks in the chain between residues 204–208, and 49–73 as no clear electron density was visible for these segments, presumably due to conformational flexibility (see below). The somewhat high crystallographic R factors of the refined model (Rwork=0.225, Rfree=0.288) likely reflect the missing residues in the model that has otherwise good stereochemistry and quality parameters as evaluated by the program Molprobity32, 33. Complete X-ray data collection and refinement statistics are shown in SI Table S1.

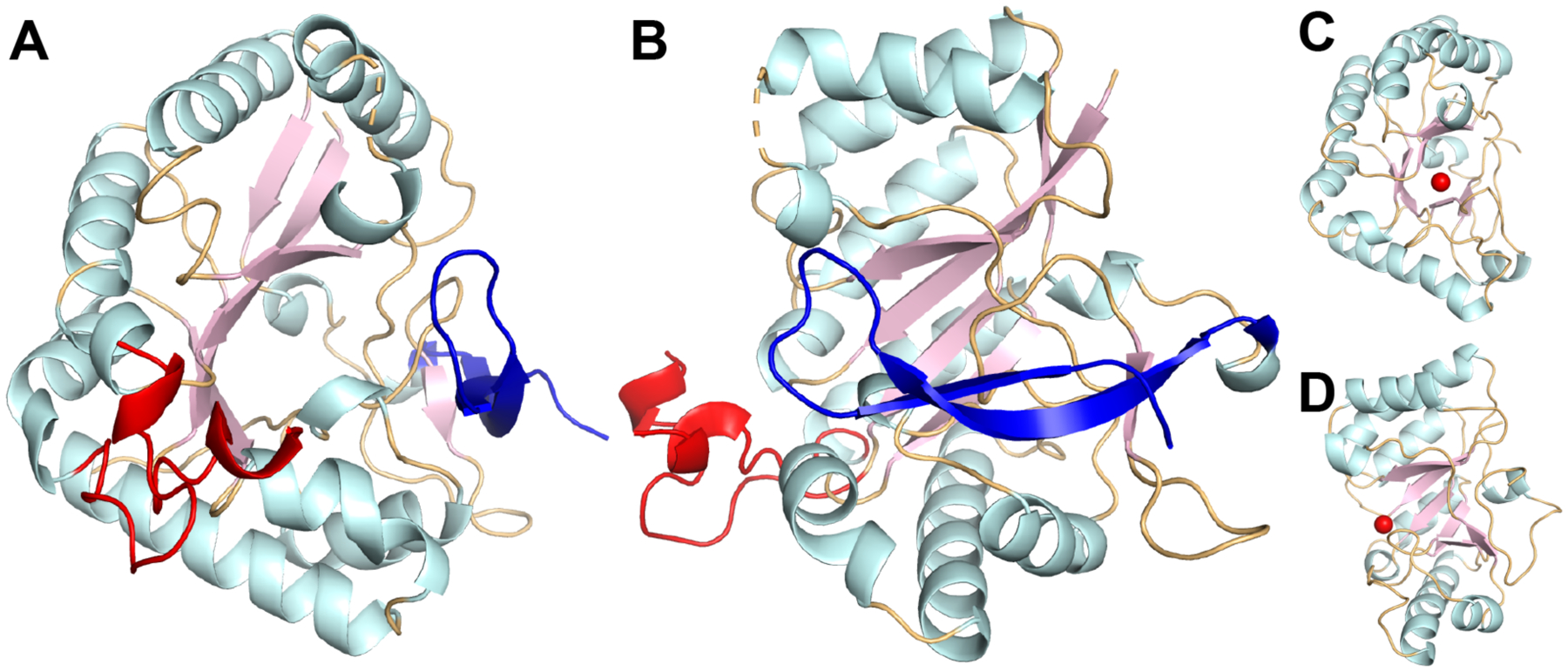

The crystal structure of ArnD (Fig. 2A–B) reveals a NodB homology domain fold with a distorted (β/α)7 barrel topology similar to the carbohydrate esterase family 4 (CE4) in the Carbohydrate Active Enzymes (CAZy) database34. The peptidoglycan deacetylase PgdA is a well-characterized representative of the CE4 family and its structure adopts the characteristic distorted (β/α)7 barrel in which one side of the barrel is formed by irregular secondary structure elements and the active site metal bound at the center of the barrel35 (Fig 2C–D). ArnD superimposed on the PgdA structure with an RMS deviation of 1.9Å over 175 α-carbons despite only having 17% sequence identity (SI Mov. S1). However, whereas the overall fold is shared with polysaccharide esterases such as PgdA, analysis of the structure of stArnD and its sequence conservation (SI Fig. S4) indicate several divergences.

Figure 2: Crystal structure of Salmonella Typhimurium ArnD.

Top (A) and side (B) views of a cartoon representation of stArnD. Strands, helices, and coils in the NodB fold are colored light pink, pale cyan and light orange, respectively. The partially modeled 44 amino acid insertion is colored red and a C-terminal β-hairpin extension is colored blue. (C-D) Cartoon representation of the PgdA structure colored and oriented as in A and B. The bound metal ion is shown in red.

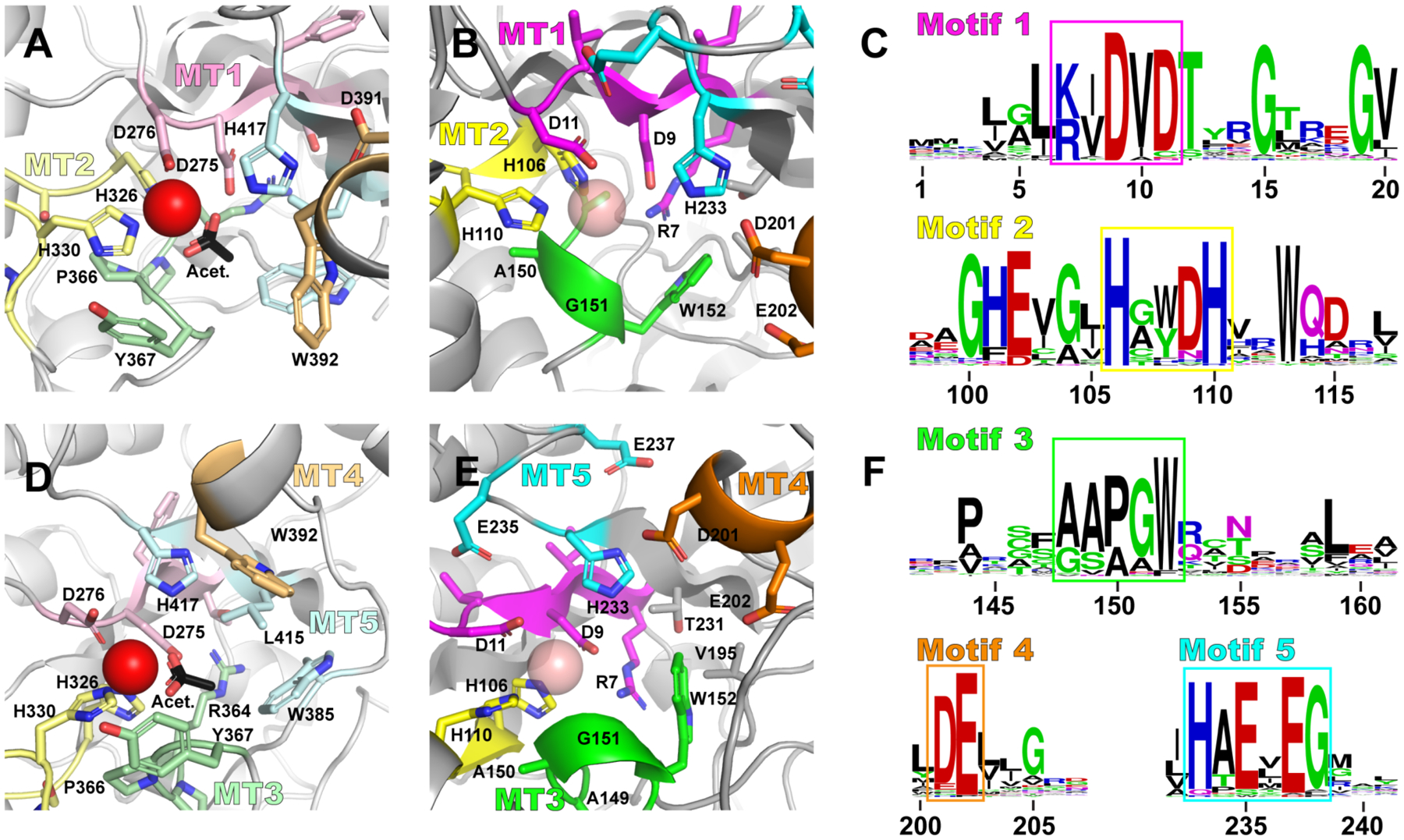

From a global fold standpoint, ArnD differs from the catalytic domain of PgdA in that a C-terminal extension forms a β-hairpin (blue in Fig. 2A–B) that packs against the distorted side of the β-barrel. Also notable is a 44 amino acid insertion protruding from the NodB fold between amino acids 41 and 85 (red in Fig 2A–B). This is only partially modeled in the crystallographic model due to conformational flexibility (see below). Previous analysis of the PgdA structure identified five conserved sequence motifs (MT1–5) associated with the polysaccharide deacetylase family35. These motifs are partially or completely divergent in ArnD proteins (SI Mov. S2). In PgdA, motif 1, TFDD, contains D275 that binds acetate and plays a role in catalysis, and D276 that binds Zn2+; while motif 2, HS/TxxHP, contributes H326 and H330 to the Zn2 binding site (Fig. 3A). In ArnD, motifs 1 and 2 have consensus sequences K/RxDVD and HxxD/NH respectively (Fig. 3B–C). Despite the partial divergence in the sequences, stArnD D9 and D11 in motif 1 as well as H106 and H110 in motif 2 conserve the three-dimensional arrangement observed in PgdA. This suggests they play similar roles in metal binding and catalysis even though our crystal structure did not display interpretable electron density at the site of metal binding. Motifs 3 and 4 in PgdA line the edges of the substrate binding groove and are defined as RPPY and DW respectively (Fig. 3D). In ArnD, motif 4 is instead composed of acidic resides (DE), and motif 3 is dominated by small side chain amino acids and a conserved C-terminal tryptophan with a consensus sequence AAPGW (AAAGW in stArnD) while the side chain of R364 in PgdA is instead contributed by the conserved R7 from motif 1 in ArnD (Fig. 3E–F). These divergences likely reflect the glycolipid nature of the ArnD substrate, C55P-Ara4FN, instead of glycan substrates in polysaccharide deacetylases such as PgdA. The last sequence motif in PgdA (MT5) is composed by the side chains of W385 and L415 that form a hydrophobic pocket to accommodate the methyl of acetyl groups in the substrates, and H417 that interacts with an acetyl oxygen and plays a role in catalysis (Fig. 3D). In ArnD, the hydrophobic pocket residues are not conserved (V195 and T231 in stArnD). Instead, the pocket is occupied by the side chain of W152 from motif 3 (Fig. 3E–F) resulting in a shallower binding site consistent with the formylated (rather than acetylated) substrate C55P-Ara4FN. The putative catalytic histidine is conserved (H233) and is surrounded by two conserved glutamates (E235 and E237, Fig. 3E). We thus propose that for ArnD proteins, motif 5 has a consensus sequence HxExEG (Figure 3F).

Figure 3: Conserved sequence motifs in ArnD vs Polysaccharide Deacetylases.

(A and D) Five motifs (MT1–5) previously described for the peptidoglycan deacetylase PgdA as a representative of polysaccharide deacetylases are shown in the active site of PgdA colored in light tints of pink (MT1), yellow (MT2), green (MT3), orange (MT4) and cyan (MT5). Bound Zn2+ ion and acetate are shown in red and black, respectively. (B and E) The corresponding but divergent motifs in ArnD are shown in bright hues of the same colors and a putative metal ion is modeled as a semitransparent sphere for reference. (C and F) Logos representations of sequence conservation in the five ArnD motifs, highlighted in boxes matching the color scheme in B-E.

ArnD membrane association

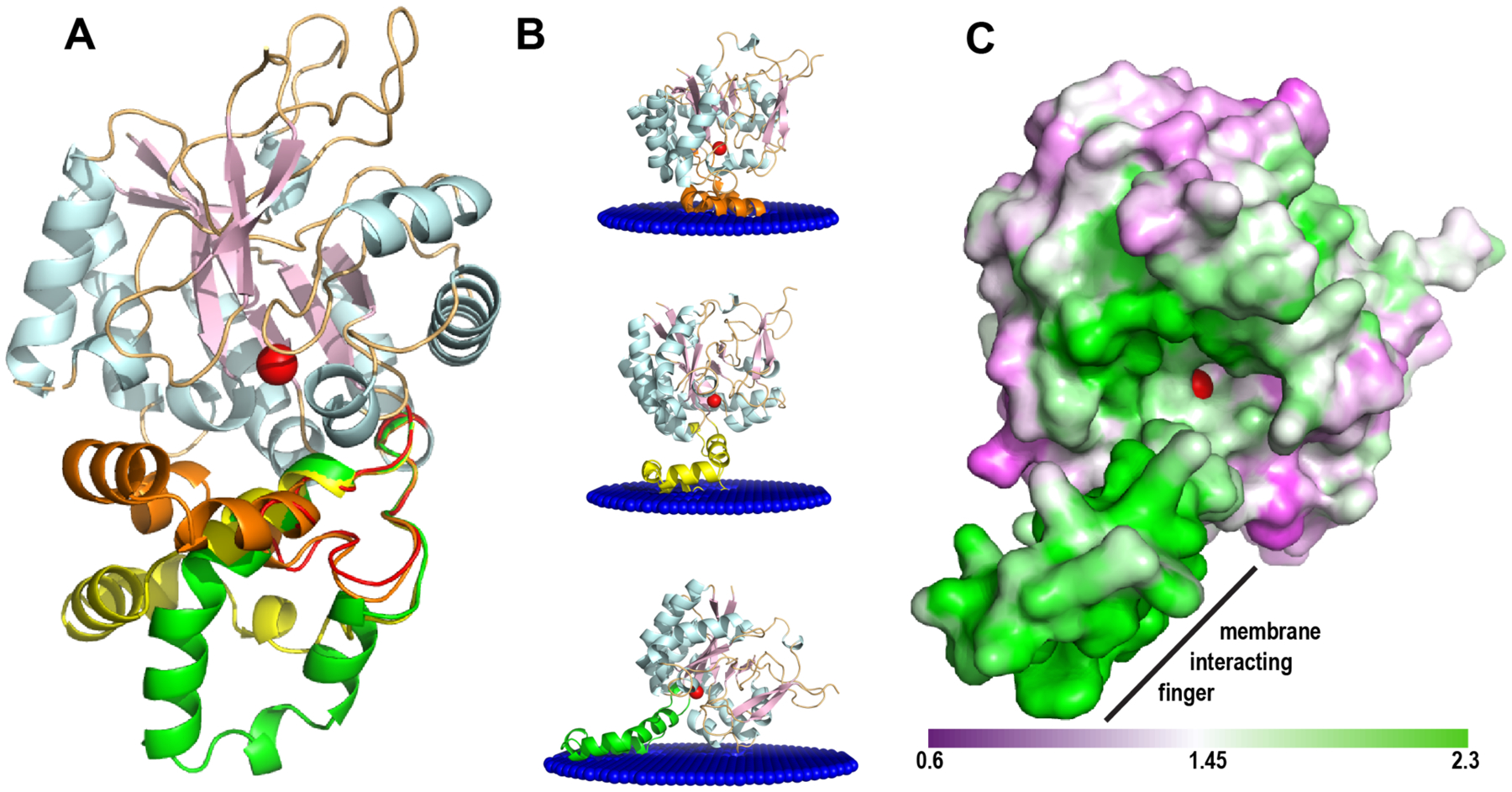

As ArnD partitions with the membrane fractions during purification despite the lack of predicted transmembrane regions, we sought to identify structural features that may mediate its membrane association. One salient characteristic of ArnD proteins is the 44 amino acid insertion that protrudes from the NodB fold (red in Fig. 2A–B). As this stretch of polypeptide could only be partially modeled in the crystal structure, AlphaFold2 predictions of the structure were utilized to develop a complete model. AlphaFold2 produced models with NodB domain architectures essentially identical to the crystal structure (SI Mov. S3, RMSD = 0.35Å). However, the 44 amino acid insertion resulted in alpha helical models that clustered in three different conformations with respect to the NodB domain (Fig. 4A). This apparent conformational flexibility is consistent with the lack of clear electron density in the crystal structure. AlphaFold2 models of the three representative conformation were submitted to the Positioning of Proteins in Membranes (PPM) server that utilizes the protein structure and amino acid composition to estimate the free energy of protein transfer from water to a membrane environment to predict membrane association36, 37. As shown in Fig. 4B, all three ArnD models resulted in a peripheral association with the membrane, in all cases mediated by the flexible 44 amino acid insertion of ArnD.

Figure 4: ArnD membrane association models.

(A) stArnD with the NodB fold colored as in Fig. 2 with AlphaFold2-generated models for the 44 amino acid insertion. Three representative conformations for the insertion are shown colored in orange, yellow and green. (B) Membrane association models calculated using the PPM server for the three representative AlphaFold2 conformations shown in panel A. (C) Representation of the solvent accessible surface for the ArnD AlphaFold2 model with the membrane-interacting “finger” in the conformation depicted at the bottom of panel B, shown from the membrane plane. The surface is colored by the non-polar to polar residue ratio in a scale from 0.6 (polar) to 2.3 (non-polar). In all panels, a metal ion in the putative active site is shown as a red sphere.

The predictions obtained with the PPM server are consistent with those obtained with two additional predictive methods: the Membrane Optimal Docking Area (MODA) server based on the statistical preference of protein surface atoms for interaction with the membrane38; and the DREAMM server that utilizes a machine learning approach trained on a set of 54 peripheral membrane proteins with amino acids experimentally determined to penetrate the membrane39. Both algorithms also identified ArnD as a peripheral membrane protein and the residues predicted to mediate the interaction with the membrane mapped to the 44 amino acid insertion in all three structural models (SI Fig. S5).

To experimentally test these predictions, we engineered two variants of stArnD where amino acids 44–82 were replaced by a glycine (del-G) or a glycine-cysteine (del-GC) linker, which eliminates most of the 44 amino acid insertion in stArnD. Expression of both variants resulted in proteins that no longer fractionated with the membrane fractions and could be purified in the absence of detergents, yielding single peaks in size exclusion chromatography without signs of aggregation (SI Fig. S6). We thus conclude that the 44 amino acid insertion in ArnD proteins constitutes a membrane interaction “finger” that recruits the enzyme to act on its membrane soluble C55P-Ara4FN substrate. Consistent with this idea, the putative membrane interacting finger is located close to the active site (denoted by the modeled metal atom shown in red in Fig. 4B). Mapping the ratio of non-polar to polar residues on the solvent accessible surface of stArnD, as calculated with the protein-sol tool40, reveals a hydrophobic “ramp” that may allow access of the C55P-Ara4FN substrate from the membrane to the metal binding active site in ArnD (Fig. 4C).

Reconstitution of ArnD activity in vitro

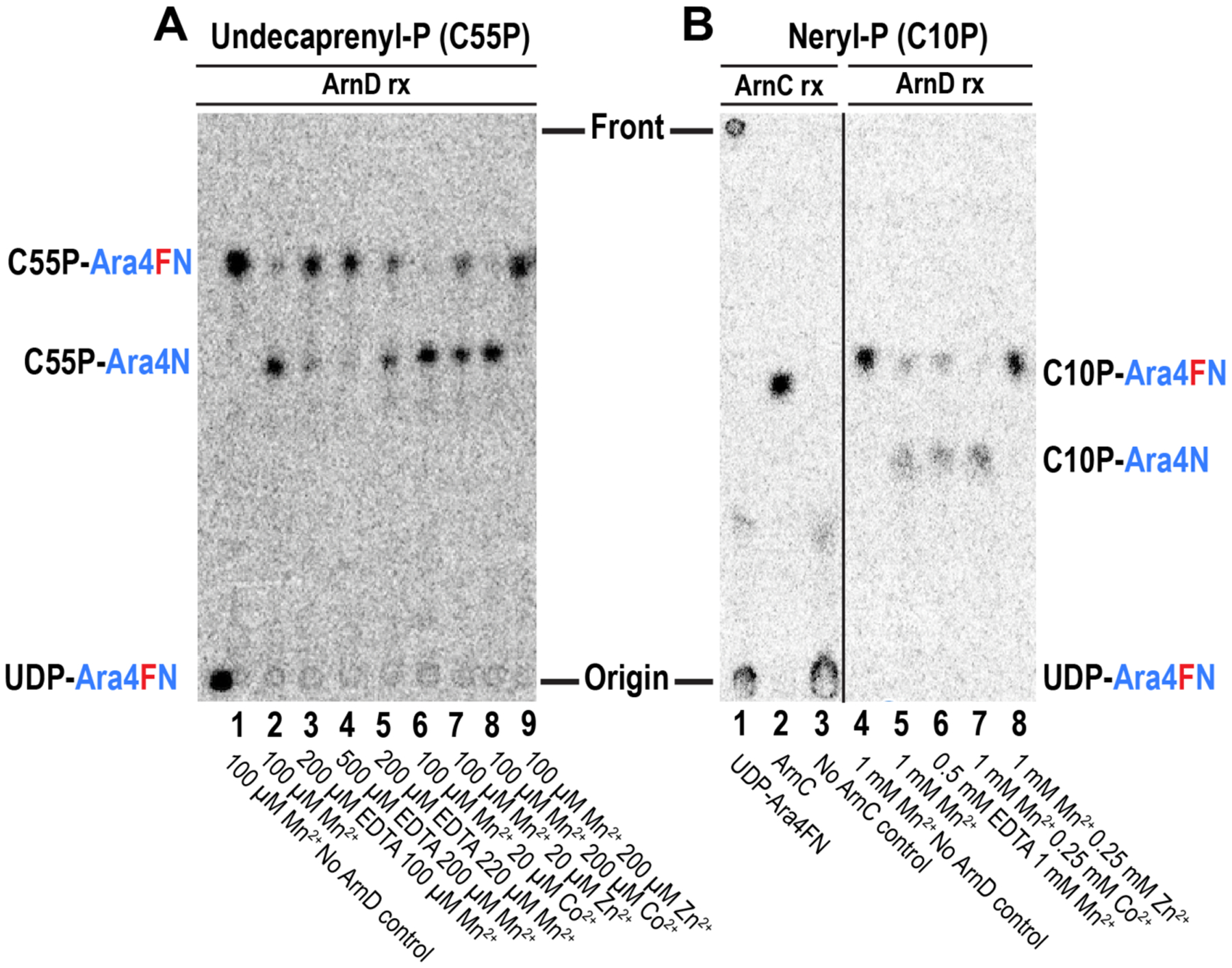

The analysis of C55P compounds derived from E. coli strains described above (Fig. 1), suggested that ArnD is responsible for deformylating the ArnC product C55P-Ara4FN in vivo. To unambiguously assign the ArnD activity, we developed an in vitro assay to use with purified recombinant stArnD. As the C55P-AraFN substrate is not commercially available, purified ArnA, ArnB and ArnC were used to convert UDP-[14C]Glucuronic acid into C55P-[14C]AraFN which results in a fast migrating species in silica thin-layer chromatography (TLC) as previously reported16 (Fig. 5A, lane 1). This product is then converted to a slower migrating species in the presence of purified ArnD, consistent with deformylation of C55P-[14C]Ara4FN to the more polar C55P-[14C]Ara4N (Fig. 5A, lane 2) indicating the reconstitution of ArnD activity in vitro.

Figure 5: ArnD is a metal-dependent lipid-phospho-L-Ara4FN deformylase.

(A) Thin layer chromatography separation of ArnD incubations with undecaprenyl-phospho-L-Ara4FN. UDP-Ara4FN was converted to C55P-Ara4FN by ArnC, and the product was incubated with purified ArnD for 10 minutes under the conditions indicated in each lane. (B) Thin layer chromatography separation of neryl-phosphate reactions with ArnC and ArnD. UDP-Ara4FN (lane 1) was incubated with neryl-phosphate plus (lane 2) or minus (lane 3) ArnC. The formylated amino-sugar is efficiently transferred by ArnC to the lipid to yield neryl-P-Ara4FN (C10P-Ara4FN). Lanes 4–8: The product of the ArnC reaction was incubated with purified ArnD for 10 minutes under the conditions indicated in each lane.

As the crystal structure indicated the conservation of a metal binding motif in ArnD, we next investigated the metal dependency of the in vitro activity. In situ synthesis of C55P-[14C]Ara4FN requires MnCl2 for the activity of ArnC. Therefore, the ArnD reaction shown in lane 2 of Fig. 5A was carried out in the presence of 100 μM Mn2+. Supplementation of the reaction with 200 or 500 μM EDTA severely impairs activity, while further addition of an excess over EDTA of 20 μM Mn2+ recovers activity indicating that ArnD can utilize Mn2+ as a metal to catalyze the deformylation of C55P-[14C]Ara4FN (Fig. 5A, lanes 3–5). Addition of 20 μM Co2+ in a background of 100 μM Mn2+ strongly stimulates ArnD activity, whereas 20 μM Zn2+ does not increase the activity above the levels observed for Mn2+ (Fig. 5A, lanes 2, 6–7). Furthermore, in a background 100 μM Mn2+, addition of 200 μM Co2+ stimulates ArnD activity while 200μM Zn2+ inhibited the reaction (Fig. 5A, lanes 8–9). We conclude that the deformylase activity of ArnD is metal dependent consistent with the conserved features of the active site observed in the crystal structure.

We next tested the ability of ArnD to deformylate neryl-phospho-L-Ara4FN (C10P-Ara4FN), a shorter, diprenyl analog of C55P-Ara4FN. In contrast to undecaprenyl-phosphate that is difficult and expensive to obtain, neryl-phosphate can be easily synthesized from inexpensive nerol (SI supplementary methods). ArnC was able to convert UDP-[14C]Ara4FN into a lipid derivative in the presence of neryl-phosphate and Mn2+ indicating the synthesis of C10P-Ara4FN (Fig. 5B lanes 1–3). This product was efficiently deformylated (10 minutes) in the background of 1mM Mn2+. Sub-stoichiometric addition of EDTA to preferentially chelate any Co2+ that may be present in the reaction over the background Mn2+ still supported the deformylation catalyzed by ArnD (Fig. 5B lanes 4–6) further indicating that ArnD can utilize Mn2+ to deformylate its substrates. Similar to the results obtained with C55P-Ara4FN, the reaction was strongly stimulated by addition of 250 μM Co2+ but was inhibited by 250 μM Zn2+ (Fig. 5B lanes 7–8). Taken together, these results indicate that ArnD is responsible for deformylating the ArnC product C55P-Ara4FN and the reaction can be reconstituted in vitro in the presence of Mn2+ or, preferentially, Co2+. Furthermore, similar levels of activity are observed for the 10-carbon isoprenoid C10P-Ara4FN, which may facilitate future quantitative evaluations of ArnD activity and inhibition.

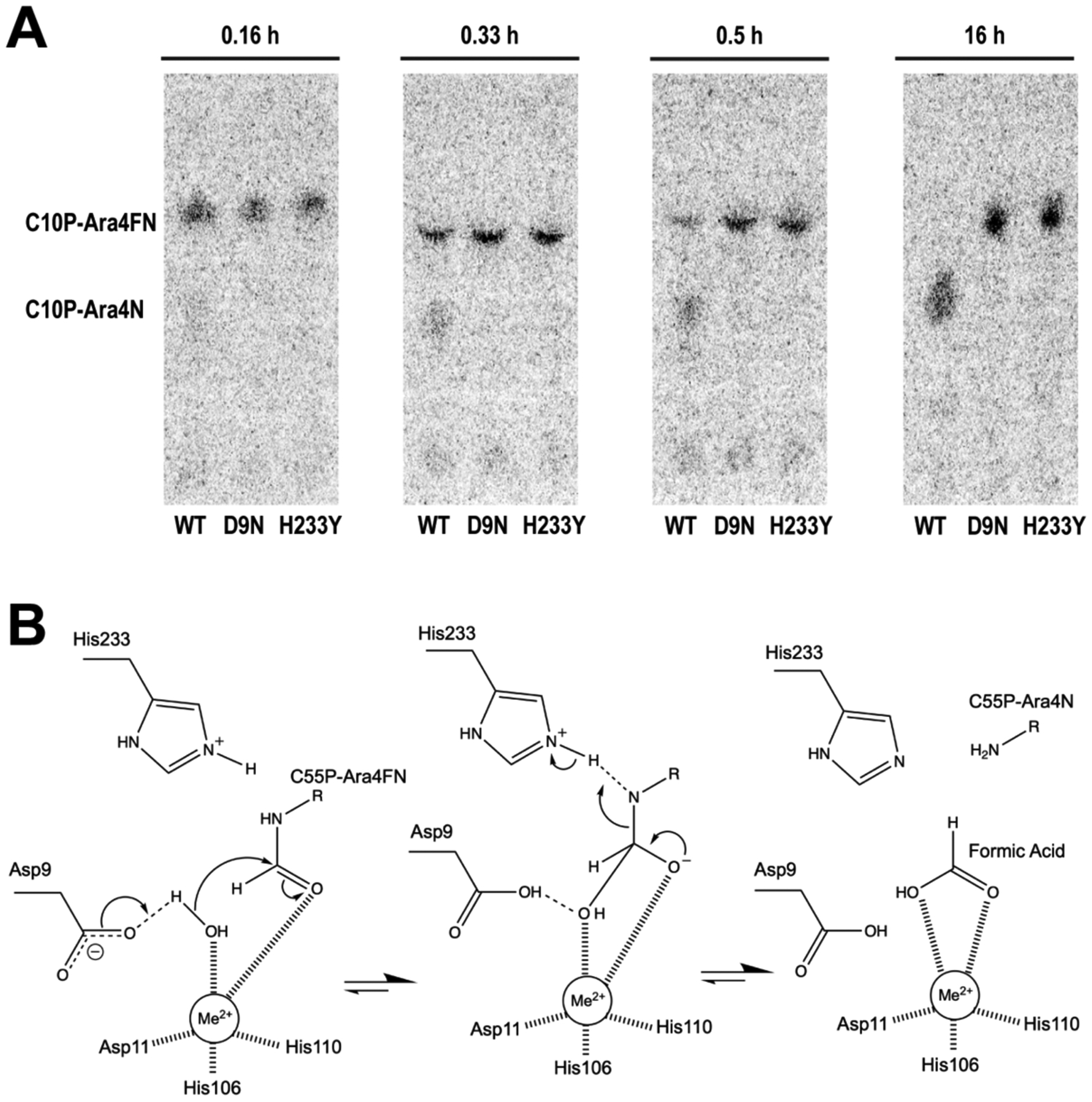

The crystal structure revealed that, in addition to the metal binding residues, an aspartate-histidine pair proposed to play roles in catalysis in polysaccharide deacetylases are conserved in the putative active site of stArnD. They are represented by D9 in motif 1 and H233 in motif 5 of stArnD. To test their potential involvement in catalysis, the deformylation activity of wild-type, D9N and H233Y mutants of ArnD was tested using C10P-[14C]Ara4FN as a substrate. As shown in Fig. 6A, both mutants were completely inactive, with no detectable activity even after a 16-hour incubation. We thus suggest that ArnD deformylates its substrates with a reaction mechanism analogous to that proposed for the peptidoglycan deacetylase PgdA35. In such mechanism (Figure 6B), a water molecule is coordinated and polarized by the strong Lewis acid metal, while D9 acts as a general base abstracting its proton. The resulting hydroxide attacks the electrophilic carbonyl carbon of the formyl group in the substrate leading to a tetrahedral intermediate where the oxyanion is stabilized by the metal. Acting as a general acid, H233 donates a proton to the nitrogen in the tetrahedral intermediate, which resolves with release of the amino sugar-lipid and formic acid products.

Figure 6: Proposed ArnD mechanism.

(A) Thin layer chromatography separations of reactions containing C10P-[14C]Ara4FN and wild type (WT) or mutant (D9N or H233Y) ArnD. Samples were taken at the indicated time points of the reaction. (B) Proposed reaction mechanism based on similarity to polysaccharide deacetylases (adapted from reference35, copyright (2005) National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A.). A coordinated divalent metal is denoted as Me2+.

Discussion

Modification of lipid A with Ara4N is one of the main mechanisms of bacterial resistance to innate immunity cationic antimicrobial peptides and the polymyxin family of antibiotics, of which colistin is the most clinically relevant. The proteins encoded in the pmrE(ugd) and arnBCADTEF loci constitute a biosynthetic pathway that converts the common metabolite UDP-Glucose into UDP-Ara4N and then into C55P-Ara4N, which serves as the amino sugar donor for lipid A modification. Interestingly, the N-terminal domain of ArnA catalyzes the N-formylation of UDP-Ara4N and the next enzyme in the pathway, ArnC, specifically utilizes the formylated intermediate for transfer to the C55P lipid carrier to yield C55P-Ara4FN. A deformylase activity is then required. We show unequivocally that ArnD is responsible for C55P-Ara4FN deformylation. Deletion of the arnD gene in pmrAc mutants of E. coli that constitutively express the arnBCADTEF operon leads to accumulation of C55P-Ara4FN. This intermediate was efficiently deformylated in vitro by purified ArnD to yield the final amino-sugar donor C55P-Ara4N.

The crystal structure of stArnD revealed an overall NodB fold and conservation of a metal binding active site similar to the carbohydrate esterase family 4 (CE4) of carbohydrate active enzymes. This family is composed of metal-dependent deacetylases that act on polysaccharide (peptidoglycan, chitin, chitooligosaccharide and xylan) substrates. However, despite retaining the distorted (β/α)7 barrel topology of the NodB fold, ArnD shares low overall sequence similarity to CE4 family members—17% sequence identity between stArnD and the representative CE4 enzyme PgdA. Furthermore, ArnD diverges in the sequence of five defining motifs as well as the presence of a 44 amino acid insertion and C-terminal β-hairpin extension. The insertion likely folds into an α-helical “finger” that mediates ArnD’s interaction with the membrane, and we show its deletion results in a soluble protein. Whereas some members of CE4 family such as Bacillus subtilis PdaC are membrane associated41, they do not contain the membrane interacting finger observed in ArnD and have separate membrane-association motifs. These divergent features suggest ArnD belongs in a separate carbohydrate esterase family, consistent with its distinct deformylase activity, membrane association motif and the glycolipid nature of its undecaprenyl-phosphate-L-Ara4FN substrate.

We show that stArnD efficient deformylation of C55P-Ara4FN is metal dependent with a preference for Co2+, although Mn2+ also supported the reaction. Promiscuity in metal binding dependence has been documented for multiple carbohydrate esterases and other enzymes35, 42–45.The metal utilized in vivo is thus likely determined by the relative availability in the environment. Adak et al. have previously reported that chemically synthesized neryl-phosphate-L-Ara4FN (C10P-Ara4FN) could be slowly deformylated in an extended (20 h) incubation with Burkholderia cenocepacia ArnD (bcArnD) in the presence of 250 μM Zn2+17. This low level of activity could be due to bcArnD not being a bona fide deformylase, the diprenol C10P-Ara4FN not being the cognate substrate, or unfavorable in vitro reaction conditions. The experiments in Fig. 5 show that stArnD efficiently deformylates C10P-Ara4FN in the presence of Mn2+ or Co2+. However, stArnD deformylation of both C10P-Ar4FN and the cognate substrate C55P-Ara4FN is inhibited at high μM concentrations of Zn2+. This suggest that the relatively low activity of bcArnD was likely due to the presence of 250 μM Zn2+ in the in vitro reaction17.

The stArnD catalytic mechanism depended on the conserved D9 and H233 residues. Mutations D9N and H233Y—the most conservative mutations for aspartate and histidine residues respectively46—completely abolished activity (Fig. 6). These results support a metal-assisted acid-base catalytic mechanism previously proposed for the deacetylase PgdA depicted in Fig. 6B. Fadouloglou et al. reported that two CE4 family polysaccharide deacetylases from B cereus and B. anthracis autocatalytically hydroxylate the Cα of a proline in the RPPY motif (MT3)47. The modification, which resulted in approximately a 10-fold enhancement of activity over the non-hydroxylated enzyme, was proposed to aid in stabilization of the tetrahedral oxyanion intermediate, representing a form of active site maturation47. Motif 3 is divergent in ArnD (AAAGW in stArnD, Fig 3E–F) and the proline hydroxylated in the bacilli polysaccharide deacetylases is neither conserved nor spatially contributed from elsewhere in the sequence, suggesting that this form of active site maturation is not observed in ArnD.

Colistin (polymyxin E) is a high priority antimicrobial in clinical use for treatment with multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacteria48–50. However, colistin resistant isolates are increasingly reported51–54. As arnD is essential for lipid A modification with Ara4N and polymyxin resistance11, it is an attractive target for development of resistance inhibitors. There is ample precedent for inhibition of metal-dependent deacetylases as a clinically viable strategy55–57. The structural and functional characterization of ArnD thus opens exciting opportunities for inhibitor development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Kathryn Tunyasuvunakool, senior scientist at DeepMind, for assistance with generation of ArnD models using AlphaFold2; Austin Bargmann for expert assistance in synthesis of neryl-phosphate; and Annette Erbse for assistance and training in the use of the Shared Instruments Pool (RRID: SCR_018986) of the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Colorado Boulder, in particular the centrifuges and the Emulsiflex C3 homogenizer.

Funding Sources

This material is based in part on work supported by a Fullbright fellowship to D.M.E. and grant AI060841 to M.C.S. from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- Ara4N

4-deoxy-4-amino-L-arabinose

- C55P-Ara4N

undecaprenyl-phospho-4-deoxy-4-amino-L-arabinose

- C55P-Ara4FN

undecaprenyl-phospho-4-deoxy-4-formamido-L-arabinose

- C10P-Ara4FN

neryl-phosphate-L- deoxy-4-formamido-L-arabinose

- UDP-Ara4FN

Uridine-diphosphoL-4-deoxy-4-formamido-L-arabinose

- pEtN

phosphoethanolamine

- C55P

undecaprenyl-phosphate

- DDM

n-Dodecyl-β-D-Maltopyranoside

- IPTG

Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- BME

b-mercaptoethanol

- Ni-NTA

nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- MWCO

molecular weight cutoff

- TLC

thin layer chromatography

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Additional figures depicting the structure of lipid A and its modifications; the pathway responsible for the biosynthesis of Ara4N-Lipid-A; the chemical structures of prenyl-phosphate and their sugar derivatives; Logos representation of sequence conservation in ArnD; predictions of membrane interacting residues in ArnD models; purification of arnD deletion mutants del-G and del-GC. Movies animating the structure superposition of stArnD and PgdA; closeup of the ArnD and PgdA active sites; structure superpositions of stArnD and three representative AlphaFold2 models. Table showing the x-ray data collection and structure refinement statistics. Supplementary method describing the synthesis of neryl-phosphate (PDF).

Conflict of interest statement.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Accession Codes

Structure factors and structure coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under accession number 8T0J (stArnD). All other data are described in the manuscript and supporting information.

References

- (1).Needham BD, and Trent MS (2013) Fortifying the barrier: the impact of lipid A remodelling on bacterial pathogenesis, Nat Rev Microbiol 11, 467–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Olaitan AO, Morand S, and Rolain JM (2014) Mechanisms of polymyxin resistance: acquired and intrinsic resistance in bacteria, Front Microbiol 5, 643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Nikaido H (2003) Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability revisited, Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67, 593–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Helander IM, Kilpelainen I, and Vaara M (1994) Increased substitution of phosphate groups in lipopolysaccharides and lipid A of the polymyxin-resistant pmrA mutants of Salmonella typhimurium: a 31P-NMR study, Mol Microbiol 11, 481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Guo L, Lim KB, Poduje CM, Daniel M, Gunn JS, Hackett M, and Miller SI (1998) Lipid A acylation and bacterial resistance against vertebrate antimicrobial peptides, Cell 95, 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ernst RK, Yi EC, Guo L, Lim KB, Burns JL, Hackett M, and Miller SI (1999) Specific lipopolysaccharide found in cystic fibrosis airway Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Science 286, 1561–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Huang J, Li C, Song J, Velkov T, Wang L, Zhu Y, and Li J (2020) Regulating polymyxin resistance in Gram-negative bacteria: roles of two-component systems PhoPQ and PmrAB, Future Microbiol 15, 445–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Groisman EA (2001) The pleiotropic two-component regulatory system PhoP-PhoQ, J Bacteriol 183, 1835–1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Gunn JS (2001) Bacterial modification of LPS and resistance to antimicrobial peptides, J. Endotoxin Res 7, 57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Gunn JS, Lim KB, Krueger J, Kim K, Guo L, Hackett M, and Miller SI (1998) PmrA-PmrB-regulated genes necessary for 4-aminoarabinose lipid A modification and polymyxin resistance, Mol Microbiol 27, 1171–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Gunn JS, Ryan SS, Van Velkinburgh JC, Ernst RK, and Miller SI (2000) Genetic and functional analysis of a PmrA-PmrB-regulated locus necessary for lipopolysaccharide modification, antimicrobial peptide resistance, and oral virulence of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium, Infect Immun 68, 6139–6146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Nummila K, Kilpelainen I, Zahringer U, Vaara M, and Helander IM (1995) Lipopolysaccharides of polymyxin B-resistant mutants of Escherichia coli are extensively substituted by 2-aminoethyl pyrophosphate and contain aminoarabinose in lipid A, Mol Microbiol 16, 271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Trent MS, Ribeiro AA, Doerrler WT, Lin S, Cotter RJ, and Raetz CRH (2001) Accumulation of a polyisoprene-linked amino sugar in polymyxin-resistant Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli: structural characterization and transfer to lipid A in the periplasm, J Biol Chem 276, 43132–43144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Yan A, Guan Z, and Raetz CR (2007) An undecaprenyl phosphate-aminoarabinose flippase required for polymyxin resistance in Escherichia coli, J Biol Chem 282, 36077–36089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Breazeale SD, Ribeiro AA, and Raetz CRH (2003) Origin of lipid A species modified with 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose in polymyxin-resistant mutants of Escherichia coli. An aminotransferase (ArnB) that generates UDP-4-deoxy-L-arabinose, J Biol Chem 278, 24731-24739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Breazeale SD, Ribeiro AA, McClerren AL, and Raetz CR (2005) A formyltransferase required for polymyxin resistance in Escherichia coli and the modification of lipid A with 4-Amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose. Identification and function oF UDP-4-deoxy-4-formamido-L-arabinose, J Biol Chem 280, 14154–14167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Adak T, Morales DL, Cook AJ, Grigg JC, Murphy MEP, and Tanner ME (2020) ArnD is a deformylase involved in polymyxin resistance, Chem Commun (Camb) 56, 6830–6833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Bretscher LE, Morrell MT, Funk AL, and Klug CS (2006) Purification and characterization of the L-Ara4N transferase protein ArnT from Salmonella typhimurium, Protein Expr Purif 46, 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Petrou VI, Herrera CM, Schultz KM, Clarke OB, Vendome J, Tomasek D, Banerjee S, Rajashankar KR, Belcher Dufrisne M, Kloss B, Kloppmann E, Rost B, Klug CS, Trent MS, Shapiro L, and Mancia F (2016) Structures of aminoarabinose transferase ArnT suggest a molecular basis for lipid A glycosylation, Science 351, 608–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Trent MS, Ribeiro AA, Lin S, Cotter RJ, and Raetz CRH (2001) An inner membrane enzyme in Salmonella and Escherichia coli that transfers 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose to lipid A: induction on polymyxin-resistant mutants and role of a novel lipid-linked donor, J Biol Chem 276, 43122–43131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Liu H, and Naismith JH (2008) An efficient one-step site-directed deletion, insertion, single and multiple-site plasmid mutagenesis protocol, BMC Biotechnol 8, 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Otwinowski Z, and Minor W (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode, Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Liebschner D, Afonine PV, Baker ML, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Croll TI, Hintze B, Hung LW, Jain S, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner RD, Poon BK, Prisant MG, Read RJ, Richardson JS, Richardson DC, Sammito MD, Sobolev OV, Stockwell DH, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev AG, Videau LL, Williams CJ, and Adams PD (2019) Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in Phenix, Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 75, 861–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Mccoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, and Read RJ (2007) Phaser crystallographic software, Journal of Applied Crystallography 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Emsley P, and Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, and Cowtan K (2010) Features and development of Coot, Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Gatzeva-Topalova PZ, May AP, and Sousa MC (2005) Structure and mechanism of ArnA: conformational change implies ordered dehydrogenase mechanism in key enzyme for polymyxin resistance, Structure 13, 929–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Lee M, and Sousa MC (2014) Structural basis for substrate specificity in ArnB. A key enzyme in the polymyxin resistance pathway of Gram-negative bacteria, Biochemistry 53, 796–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Gatzeva-Topalova PZ, Andrew P, and Sousa MC (2005) Crystal structure and mechanism of the Escherichia coli ArnA (PmrI) transformylase domain. An enzyme for lipid A modification with 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose and polymyxin resistance, Biochemistry 44, 5328–5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Guan Z, Wang X, and Raetz CR (2011) Identification of a chloroform-soluble membrane miniprotein in Escherichia coli and its homolog in Salmonella typhimurium, Anal Biochem 409, 284–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Safarian S, Hahn A, Mills DJ, Radloff M, Eisinger ML, Nikolaev A, Meier-Credo J, Melin F, Miyoshi H, Gennis RB, Sakamoto J, Langer JD, Hellwig P, Kuhlbrandt W, and Michel H (2019) Active site rearrangement and structural divergence in prokaryotic respiratory oxidases, Science 366, 100–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Lovell SC, Davis IW, Arendall WB 3rd, de Bakker PI, Word JM, Prisant MG, Richardson JS, and Richardson DC (2003) Structure validation by Calpha geometry: phi,psi and Cbeta deviation, Proteins 50, 437–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Williams CJ, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Prisant MG, Videau LL, Deis LN, Verma V, Keedy DA, Hintze BJ, Chen VB, Jain S, Lewis SM, Arendall WB 3rd, Snoeyink J, Adams PD, Lovell SC, Richardson JS, and Richardson DC (2018) MolProbity: More and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation, Protein Sci 27, 293–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Drula E, Garron ML, Dogan S, Lombard V, Henrissat B, and Terrapon N (2022) The carbohydrate-active enzyme database: functions and literature, Nucleic Acids Res 50, D571-D577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Blair DE, Schuttelkopf AW, MacRae JI, and van Aalten DM (2005) Structure and metal-dependent mechanism of peptidoglycan deacetylase, a streptococcal virulence factor, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 15429–15434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Lomize MA, Pogozheva ID, Joo H, Mosberg HI, and Lomize AL (2012) OPM database and PPM web server: resources for positioning of proteins in membranes, Nucleic Acids Res 40, D370–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Lomize AL, Todd SC, and Pogozheva ID (2022) Spatial arrangement of proteins in planar and curved membranes by PPM 3.0, Protein Sci 31, 209–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Kufareva I, Lenoir M, Dancea F, Sridhar P, Raush E, Bissig C, Gruenberg J, Abagyan R, and Overduin M (2014) Discovery of novel membrane binding structures and functions, Biochem Cell Biol 92, 555–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Chatzigoulas A, and Cournia Z (2022) Predicting protein-membrane interfaces of peripheral membrane proteins using ensemble machine learning, Brief Bioinform 23, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Hebditch M, and Warwicker J (2019) Web-based display of protein surface and pH-dependent properties for assessing the developability of biotherapeutics, Sci Rep 9, 1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Grifoll-Romero L, Sainz-Polo MA, Albesa-Jove D, Guerin ME, Biarnes X, and Planas A (2019) Structure-function relationships underlying the dual N-acetylmuramic and N-acetylglucosamine specificities of the bacterial peptidoglycan deacetylase PdaC, J Biol Chem 294, 19066–19080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Oberbarnscheidt L, Taylor EJ, Davies GJ, and Gloster TM (2007) Structure of a carbohydrate esterase from Bacillus anthracis, Proteins 66, 250–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Caufrier F, Martinou A, Dupont C, and Bouriotis V (2003) Carbohydrate esterase family 4 enzymes: substrate specificity, Carbohydr Res 338, 687–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Martinou A, Koutsioulis D, and Bouriotis V (2002) Expression, purification, and characterization of a cobalt-activated chitin deacetylase (Cda2p) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Protein Expr Purif 24, 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Taylor EJ, Gloster TM, Turkenburg JP, Vincent F, Brzozowski AM, Dupont C, Shareck F, Centeno MS, Prates JA, Puchart V, Ferreira LM, Fontes CM, Biely P, and Davies GJ (2006) Structure and activity of two metal ion-dependent acetylxylan esterases involved in plant cell wall degradation reveals a close similarity to peptidoglycan deacetylases, J Biol Chem 281, 10968–10975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Jonson PH, and Petersen SB (2001) A critical view on conservative mutations, Protein Eng 14, 397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Fadouloglou VE, Balomenou S, Aivaliotis M, Kotsifaki D, Arnaouteli S, Tomatsidou A, Efstathiou G, Kountourakis N, Miliara S, Griniezaki M, Tsalafouta A, Pergantis SA, Boneca IG, Glykos NM, Bouriotis V, and Kokkinidis M (2017) Unusual alpha-Carbon Hydroxylation of Proline Promotes Active-Site Maturation, J Am Chem Soc 139, 5330–5337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Michalopoulos A, and Papadakis E (2010) Inhaled anti-infective agents: emphasis on colistin, Infection 38, 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Scocchi M, Mardirossian M, Runti G, and Benincasa M (2016) Non-Membrane Permeabilizing Modes of Action of Antimicrobial Peptides on Bacteria, Curr Top Med Chem 16, 76–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Sharma S, Sahoo N, and Bhunia A (2016) Antimicrobial Peptides and their Pore/Ion Channel Properties in Neutralization of Pathogenic Microbes, Curr Top Med Chem 16, 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Alvarez Lerma F, Munoz Bermudez R, Grau S, Gracia Arnillas MP, Sorli L, Recasens L, and Mico Garcia M (2017) Ceftolozane-tazobactam for the treatment of ventilator-associated infections by colistin-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Rev Esp Quimioter 30, 224–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Cheng YH, Lin TL, Pan YJ, Wang YP, Lin YT, and Wang JT (2015) Colistin resistance mechanisms in Klebsiella pneumoniae strains from Taiwan, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59, 2909–2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Jayol A, Nordmann P, Brink A, and Poirel L (2015) Heteroresistance to colistin in Klebsiella pneumoniae associated with alterations in the PhoPQ regulatory system, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59, 2780–2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Jayol A, Poirel L, Brink A, Villegas MV, Yilmaz M, and Nordmann P (2014) Resistance to colistin associated with a single amino acid change in protein PmrB among Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates of worldwide origin, Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58, 4762–4766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Kumar Pal S, and Kumar S (2023) LpxC (UDP-3-O-(R-3-hydroxymyristoyl)-N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase) inhibitors: A long path explored for potent drug design, Int J Biol Macromol 234, 122960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Guo F, and Wang H (2022) Potential of histone deacetylase inhibitors for the therapy of ovarian cancer, Front Oncol 12, 1057186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Hai R, Yang D, Zheng F, Wang W, Han X, Bode AM, and Luo X (2022) The emerging roles of HDACs and their therapeutic implications in cancer, Eur J Pharmacol 931, 175216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.