Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is one of the most common forms of inflammatory arthritis and while advances in psoriasis therapeutics have led to skin clearance in many patients using targeted biologics, joint efficacy lags behind.1-4 Even in patients with seemingly controlled inflammation, up to half continue to experience “residual” pain.5,6 Clinically, patients may present with continued tender joints after treatment without any evidence of active swelling or inflammation. While this is often treated with up-titration or change in immunomodulatory therapy, the drivers of persistent joint pain are unknown. We hypothesize that it is driven primarily by non-inflammatory causes, such as psychologic distress, fatigue, and sleep disturbance. Here we aimed to define the prevalence and clinical characteristics of non-inflammatory persistent joint pain in PsA patients.

Consecutive patients (n=121) were enrolled from the NYU Psoriatic Arthritis Center (PAC) into an observational cohort. Patients were defined as active (≥1 swollen joint), in remission (0 swollen and tender joints), or having persistent joint pain (0 swollen joints, ≥1 tender joint). This study was approved by the NYU IRB (s20-00084). Full methods can be found in the supplemental material.

At time of evaluation, 26/121 (21.5%) participants had active disease and 95 (78.5%) had no swollen joints or evidence of active synovitis as assessed by physical exam. Of those without swollen joints, 70 (73.7%) were in full remission and 25 (26.3%) had persistent joint pain with an average of 3.0 tender joints (SD 2.8) (Table 1). Patients with persistent joint pain had similar demographics, low levels of fibromyalgia, and disease characteristics to those in full remission, including presence of peripheral erosions or axial disease, mean time between symptom onset to diagnosis, and number of past biologics used. Additionally, the groups had a similar proportion of patients with elevated acute phase reactants and currently on biologics. Patients with persistent joint pain had worse physician global scores compared to those in remission (2.5 vs 1.4, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cross-Sectional Cohort

| Characteristic | All (n=95) | Remission (n=70) | Persistent Joint Pain (n=25) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and Comorbidities | ||||

| Age-- mean (SD) | 47.8 (13.7) | 46.6 (14.0) | 51.0 (12.4) | 0.16 |

| Female-- n(%) | 49 (51.6) | 37 (52.9) | 12 (48.0) | 0.65 |

| Race-- n(%) | 0.24 | |||

| White | 76 (80.0) | 58 (82.9) | 18 (72.0) | |

| Asian | 3 (3.2) | 2 (2.9) | 1 (4.0) | |

| Black | 2 (2.1) | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 14 (14.7) | 8 (11.4) | 6 (24.0) | |

| Hispanic-- n(%) | 6 (6.3) | 3 (4.3) | 3 (12.0) | 0.36 |

| Cardiovascular disease*—n(%) | 39 (41.1) | 25 (35.7) | 14 (56.0) | 0.10 |

| Fibromyalgia—n(%) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.0) | 0.26 |

| Disease Characteristics | ||||

| Erosions-- n(%) | 25 (26.3) | 19 (27.1) | 6 (24.0) | > 0.99 |

| Axial disease—n(%) | ||||

| Radiographic | 12 (12.6) | 11 (15.7) | 1 (4.0) | 0.17 |

| Nonradiographic | 7 (7.4) | 7 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.18 |

| Past biologics -- mean (SD) | 1.8 (1.9) | 2.0 (2.0) | 1.4 (1.6) | 0.21 |

| Diagnosis Delay (years)-- mean (SD) | 2.3 (6.0) | 2.4 (6.4) | 2.2 (5.1) | 0.94 |

| Current Disease Activity | ||||

| BMI-- mean (SD) | 29.3 (7.1) | 29.1 (7.6) | 29.7 (5.9) | 0.72 |

| % BSA-- mean (SD) | 1.0 (3.5) | 1.1 (4.0) | 0.7 (1.3) | 0.68 |

| Enthesitis-- n(%) | 12 (12.6) | 7 (10.0) | 5 (20.0) | 0.22 |

| Elevated ESR-- n(%) | 23 (24.2) | 17 (24.3) | 5 (20.0) | 0.46 |

| Elevated CRP-- n(%) | 17 (17.9) | 13 (18.6) | 4 (16.0) | 0.44 |

| Physician Global—mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.4 (1.1) | 2.5 (1.1) | < 0.001 |

| Current biologic-- n(%) | 82 (86.3) | 60 (85.7) | 22 (88.0) | > 0.99 |

BMI denotes body mass index, %BSA percent of body surface area affected by psoriasis, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP c-reactive protein

Cardiovascular disease includes hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, history of myocardial infraction, history of stroke

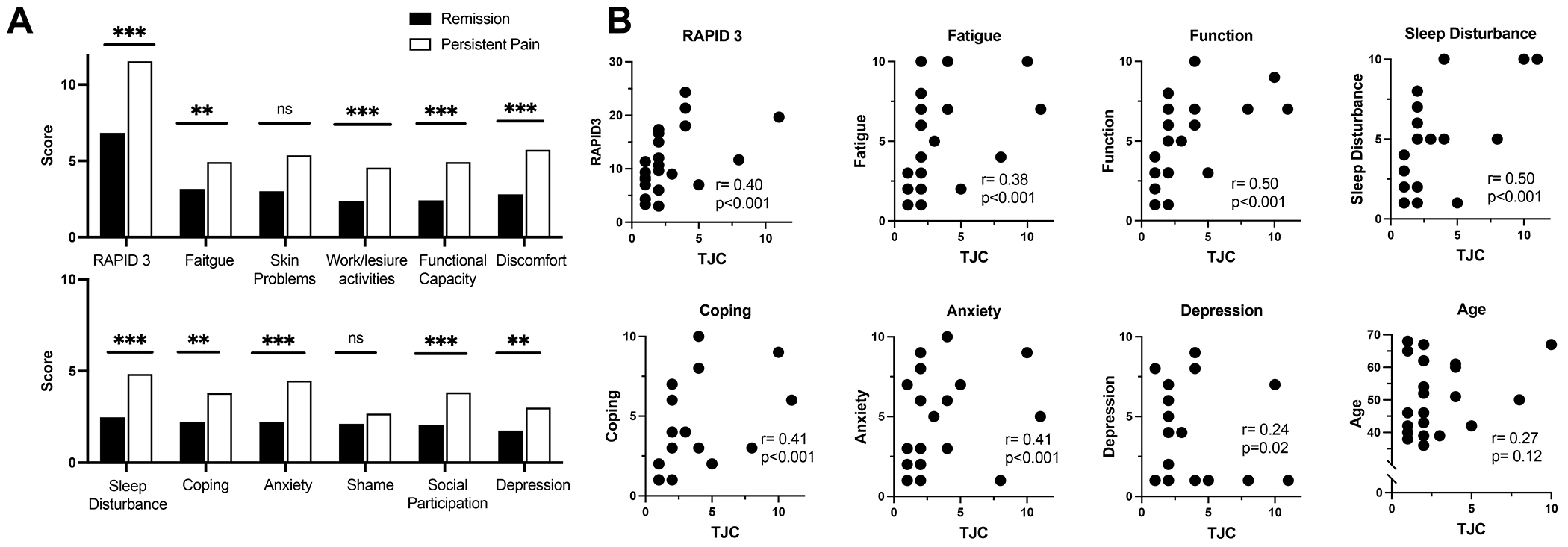

Despite these similarities, patients with persistent joint pain had higher levels of fatigue, depression, and anxiety compared to those in remission as well as worse coping mechanisms, more impact on their work and social life, and increased sleep disturbance (as measured by PsAID; Figure 1A). Global mental health scores (PROMIS10) were also worse in those with persistent pain (49.9 vs. 45.2, P= 0.02, lower scores indicating decreased mental health). In patients with persistent joint pain, the number of tender joints was moderately correlated with level of fatigue, function, sleep disturbance, coping difficulties, and anxiety, weakly correlated with depression, but not with age (Figure 1B). Patients with persistent joint pain had similar patient reported outcomes to those with active inflammatory disease (Table S1, Figure S1).

Figure 1. Increased psychosocial stress in patients with persistent joint pain.

(A) Comparison in patient reported outcomes between those in complete remission (blue) and those with persistent joint pain (purple). On all scales, higher number represents worse outcome. (B) Correlation between number of tender joints in those with persistent pain (but without synovitis) and patient reported outcomes. Acronyms: RAPID3, Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3; TJC, tender joint count. ** p<0.01. *** P< 0.001

A second cohort of PAC patients (n=143) with newly diagnosed PsA and at least one subsequent visit was followed for an average of 7.9 months (SD 7.6) to assess for disease outcome (active, remission, persistent joint pain) after initiation of treatment. At follow up, 59 participants were active, 56 were in remission and 28 had persistent joint pain. Patients with persistent joint pain were older, but had similar baseline disease activity (Table S2). Self-reported depression ever (Odds ratio (OR) 2.45, 95% CI 0.92-6.50) and an increased tender and swollen joint count difference at baseline (OR 1.09, 95% CI 0.99-1.20) were the most predictive of having later persistent joint pain compared to continued activity or remission, even after adjustment for age, although neither achieved statistical significance (Figure S2).

In a population of patients with PsA that was generally without fibromyalgia, we found that up to a quarter experience persistent joint pain, despite an absence of objective inflammation on exam, underlining the pervasiveness of this clinical scenario. Those with remaining tender joints reported more fatigue, sleep disturbance, depression, and anxiety and worse ability to cope than those without although we cannot determine the directionality of this relationship from a cross-sectional analysis. However, our longitudinal cohort did find that those with a history of depression were more likely to have persistent joint pain after initiation of treatment than those without, in line with previous studies showing that co-morbid depression can hamper PsA remission.7,8 We are limited in the classification of persistent joint, which lacked corresponding radiographic confirmation of the absence of inflammation, and the low prevalence of fibromyalgia, preventing the detection of its possible contribution.

Understanding the modulators of residual joint pain is of critical importance to improve outcomes in PsA. In patients initiating their second or later biologic, only a minority will remain on the drug and achieve remission.9 While this may reflect “treatment resistant” PsA, alternatively, it may also represent failure to differentiate between true inflammatory pain from pain perpetuated by other, non-inflammatory factors. While new and potentially effective treatment strategies are emerging,10 adjuvant therapies (i.e., targeting mental health and sleep) may be necessary to improve outcomes in PsA.

Supplementary Material

Support:

This study was funded by NIH/NIAMS (1UC2AR081029 to Scher, T32-AR-069515 to Haberman, Scher, 5UC2AR081039-02S1 to Scher, Haberman), NYU Colton Center for Autoimmunity, Rheumatology Research Foundation, the National Psoriasis Foundation, The Beatrice Snyder Foundation, The Riley Family Foundation.

Footnotes

This study was approved by the New York University Institutional Review Board (i20-00084).

Contributor Information

Rebecca H. Haberman, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY

Ying Yin Zhou, Department of Medicine, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY.

Sydney Catron, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY.

Adamary Felipe, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY.

Kathryn Jano, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY.

Soumya M. Reddy, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY

Jose U. Scher, Division of Rheumatology, Department of Medicine and the Colton Center for Autoimmunity, NYU Grossman School of Medicine

Declaration of interests:

RHH has served as a consultant for Janssen and UCB. SMR has served as a consultant for UCB, Novartis, Amgen, Fresenius Kabi, Abbvie and has received clinical research support from Pfizer, Janssen, and Eli Lilly. JUS has served as a consultant for Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Amgen, UCB, BMS and AbbVie; and has received funding for investigator-initiated studies from Janssen and Pfizer. YZ, SC, AF, KJ have no disclosures.

References

- 1.McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2015;386:1137–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mease P, Hall S, FitzGerald O, et al. Tofacitinib or Adalimumab versus Placebo for Psoriatic Arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1537–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mease PJ, Goffe BS, Metz J, VanderStoep A, Finck B, Burge DJ. Etanercept in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: a randomised trial. Lancet 2000;356:385–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deodhar A, Helliwell PS, Boehncke WH, et al. Guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis who were biologic-naive or had previously received TNFα inhibitor treatment (DISCOVER-1): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020;395:1115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogdie A, Reddy S, Craig E, et al. Residual Symptoms in Patients with PsA Who Are in Very Low Disease Activity According to Physician Assessments [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72:Suppl 10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kilic G, Kilic E, Nas K, Kamanlı A, Tekeoglu İ. Residual symptoms and disease burden among patients with psoriatic arthritis: is a new disease activity index required? Rheumatol Int 2019;39:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haberman RH, Um S, Catron S, et al. Paradoxical Effects of Depression on Psoriatic Arthritis Outcomes in a Combined Psoriasis-Psoriatic Arthritis Center. Journal of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis;0:24755303231186405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michelsen B, Kristianslund EK, Sexton J, et al. Do depression and anxiety reduce the likelihood of remission in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis? Data from the prospective multicentre NOR-DMARD study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1906–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glintborg B, Giuseppe DD, Wallman JK, et al. Uptake and effectiveness of newer biologic and targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in psoriatic arthritis: results from five Nordic biologics registries. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2023;82:820–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritchlin C, Scher JU. Strategies to Improve Outcomes in Psoriatic Arthritis. Current Rheumatology Reports 2019;21:72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.