Abstract

Cherenkov imaging is a unique verification tool that could provide both dosimetric and tissue function information during radiation therapy. However, the number of interrogated Cherenkov photons in tissue is always limited and tangled with stray radiation photons, severely frustrating the measurement single-to-noise ratio. As such, here a noise-robust photon-limited imaging technique is proposed by comprehensively exploiting the physical rationale of low-flux Cherenkov measurements together with the spatial correlations of target scene. Validation experiments confirmed that Cherenkov signal could be promisingly recovered with high SNR by irradiating at as few as one x-ray pulse from a linear accelerator (10 mGy dose), and the Cherenkov excited luminescence imaging sensitivity can be extended by >1cm depth or >100% on average, for most concentrations of phosphorescent probe. This approach demonstrates that improved applications in radiation oncology could be seen when signal amplitude, noise robustness, and temporal resolution are comprehensively considered into the image recovery process.

Imaging of Cherenkov emission during radiation therapy can be uniquely achieved as a way to map the dose delivered to each patient, with real-time, and non-contact sampling of the entire dose field [1,2]. Additionally, Cherenkov excited luminescence imaging (CELI) is a high-sensitivity molecular imaging modality that can provide molecular tissue function information being examined in research studies [3]. These imaging techniques are based in cameras that have been optimized for fast time-synchronized signal gating and with substantial image processing steps, to allow single-photon level image data to be captured and used. The detectable Cherenkov signals emitted from tissue are concentrated in the red to near infrared wavelength bands, but still strong optical scattering and absorption in tissue considerably attenuate the detected light signals (radiant exitance ~0.1mW/cm2) and any secondary molecular excited luminescence signals are typically an order of magnitude weaker than this. Thus, Poisson noise dominates the lower limits of the measurement [3,4]. Apart from having weak detection of emission, the camera measurement also inevitably contains severe slat-and-pepper noise, as indicated by saturated pixels or non-functional pixels, caused by stray x-ray radiation striking parts of the intensified cameras used (e.g., ICCD and ICMOS) [5]. In this regard, the Cherenkov images typically suffer from low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which is commonly solved largely by integrating images for longer times. However practically integrating for longer times cannot be done if there are limits to the radiation dose that is being used, and so increased signal is not always possible nor desirable. In this study a fundamentally new approach to suppressing noise is illustrated for the first time in Cherenkov imaging of radiation dose.

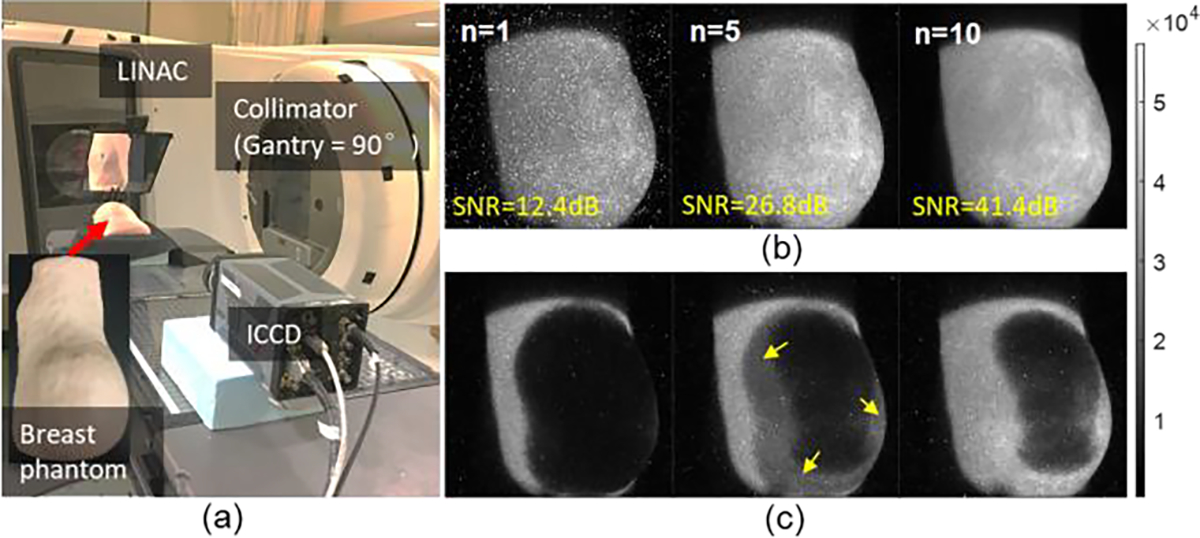

A typical solution that helps suppress both types of noise is to perform temporal median filtering in conjunction with appropriate accumulations on chip (AOC) [4]. Figure 1 exemplifies Cherenkov imaging of a step-and-shoot IMRT treatment delivered to a breast phantom using an ICCD camera for fast frame capture and integration. The phantom was designed to mimic a full-size right breast, made of soft clay (B00LH2DWDW, Sculpey Inc., Stockbridge, GA) that has optical properties of and at 625nm. As seen from Fig. 1(b), the SNR remarkably increases with the number of frames () to be median filtered. To fulfill the specific requirement on SNR, the framerate of Cherenkov measurement is limited, e.g., 17 frames per second or even less in dosimetric applications [1], which allows for a video imaging of the treatment. This frame rate balances integration of images, to have sufficient signal to make them useful to view. However, dynamics and lower dose rates or lower energies produce sub-standard images, and so limits in temporal resolution could frustrate image quality during a single fraction of the treatment, because of either overlapping acquisitions as illustrated in Fig. 1(c), or just inferior image quality. Moreover, the ending frame in either a single fraction or whole treatment could be underestimated due to an inconsistent number of frames to be integrated or temporally filtered.

Fig. 1.

The consequence of sacrificing temporal resolution and radiation dose delivered to enhance image SNR. (a) Measurement geometry for Cherenkov imaging of a step-and-shoot IMRT breast treatment. (b) Imaging results after temporal median filtering of a various number of frames (n) with each frame obtained at 36 AOCs (at 360Hz AOC). (c) Misinterpretation in an intermediate frame by overlapping adjacent ones.

To achieve photon-limited Cherenkov imaging with a better balance between SNR and temporal resolution, an effective image reconstruction strategy is herein proposed. We utilized the photon-limited imaging technique, which has extensive applications in remote sensing of a dynamic scene at a long standoff distance, where the limitations on the optical flux and integration time preclude further collection of target photons. First photon imaging (FPI) is an approach to circumvent the imaging problem, that only records the first detected photon arrival incident at each pixel to recover both the reflectivity and 3D profile of interrogated scene [6]. In past years, FPI has been continuously improved in acquisition speed and photon efficiency, e.g., an extreme photon budget down to 0.01 photon per pixel was reported by combing FPI with single-pixel imaging technique [7,8]. Recently, it was further extended for long-distance LiDAR up to 200 km and non-line-of-sight imaging over 1.43 km [9,10].

Given the similar challenges in remote sensing as discussed, the image reconstruction scheme that originated from the FPI was modified and implemented for photon-limited Cherenkov imaging in this study. We define to be the distribution of underlying Cherenkov signal integrated over a single pulse of a clinical linear accelerator (Linac), and the corresponding latent background emissions. is defined as the total Cherenkov signal acquired during Linac pulses or AOCs. The detector rate function can be discretized as

| (1) |

where is the photon efficiency of the th pixel, determined via a flood-field calibration. The stray x-ray typically leads to irregularly high photon-count rates locally as illustrated in Fig. 1(b), making their detection times uninformative [4]. Consequently, these ‘hot pixels’ can be located by performing a classical histogram-based thresholding strategy, and then removed by averaging the neighbor pixels at a window size of 3×3 so that their outputs could be ignored in Eq. (1). The above equation remains applicable for CELI measurement over a defined width of time gate.

Let be the observed number of Cherenkov photons over AOCs at pixel after median filtering or not. The problem addressed in this letter is the estimation of from . As per the theory of photon counting, the statistical distribution of obeys a Poisson distribution with parameter , i.e.,

| (2) |

The probability mass function of can thus be expressed in terms of , as

| (3) |

The maximum likelihood estimation on of the above probability distribution can be formulated as

| (4) |

This is a strictly convex function of , of which the optimization yields

| (5) |

We take as the non-negative that minimizes the sum of negative maximum likelihood functions over all locations and a sparsity-promoting regularization term, i.e.,

| (6) |

where is a total-variation seminorm, and was empirically set depending on the measurement SNR. The optimization in Eq. (6) is strictly convex, since it is the nonnegative weighted sum of individually convex functions. The solution can be done efficiently using projected-gradient methods, e.g., the SPIRAL algorithm [11]. In the iterative solution, the initial guess of used the expression in Eq. (5). To further minimize the background noise while remaining effective on the target, a negative log-form substitution of is found to be helpful, i.e.,

| (7) |

Note that is herein assumed to be already rescaled to a range of [0, 1).

Cherenkov light was induced by irradiation from a clinical linear accelerator, Linac (2100CD, Varian Medical System, USA) with fixed photon energy of 6 MV and dose rate of 600 monitor units (MU) per minute. Two types of time-gated imaging systems were involved, i.e., an ICMOS (TRC411, Intelligent Scientific Systems, China) camera equipped with a zoom lens (Cannon EF 24–105mm ) and an ICCD (PI-MAX4 1024i, Princeton Instruments, USA) camera with a prime lens (Cannon EF 135mm ). The ICCD and ICMOS cameras used have similar performance in quantum efficiency (25% vs. 17% @500nm), gain factor (10,000 vs. 8,000), equivalent background illumination (0.02 vs. <0.05 photo e−/pixel/sec), and read noise (>16 vs. 23 e− rms). The ICMOS and ICCD cameras were gated by synchronizing to the radiation pulses (approximately of 3.25 μs duration, 360 Hz repetition rate) and turned on at a 3.5 μs or 500 μs gate delay with a fixed gate width of 50 μs following each radiation pulse for luminescence or background measurement. Of note, the background measurement was an approximation of by assuming a limited variation in microsecond-level durations.

In the first experiment, Cherenkov imaging of extremely low radiation dose was done by using an ICMOS camera mounted on a tripod about 2 meters away from the target as shown in Fig. 2(a). The target was a 5000-ml optically-transparent jug full of water at the Linac isocenter. The threshold used for hot-pixel removal was determined from the histogram as shown in Fig. 2(b). Hot pixels were removed in prior to the subsequent denoising procedure. The ground truth Cherenkov image was obtained by median filtering over 150 frames acquired at 2 AOCs [Fig. 2(c)]. Two state-of-the-art competitive methods were involved, i.e., the non-local mean (NLM) [12] and standard block-matched 3D (BM3D) denoising approach [13]. In NLM, the radius of the search window and similarity window were set as 3 and 2, respectively. The similarity between the denoised results and the ground truth image was evaluated by using the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and structural similarity (). It can be seen in Figs. 2 (d) and (e) that the SNRs of raw images were below zero and increased above 20dB for all the denoising methods. The BM3D outperformed the NLM in SNR, with an average increase on SNR of 18.7%, PSNR of 3.2%, and SSIM of 55.6%. Comparing to the BM3D, the proposed method has an outstanding enhancement in SNR of 35.0%, PSNR of 51.3%, and SSIM of 46.9%. The Cherenkov image acquired at 6 AOCs has an acceptable fidelity as per PSNR criterion (i.e., >30dB). The PSNR value further increases to 35.3dB by performing a thresholding of 3% on the raw image when a dosimetric application is considered.

Fig. 2.

Comparison among various image enhancement strategies for Cherenkov imaging at extremely low SNR. (a) Experimental setup configuration. (b) Histogram-based hot-pixel removal. (c) Ground truth Cherenkov image acquired at high SNR. (d) & (e) Imaging results of Cherenkov light in water induced by a 10×10cm2 radiation beam at 1 and 6 Linac pulses, respectively, with each representative recovery approach noted in the figures, including Raw images, with hot pixels removed, non-local mean (NLM), block-matched 3D denoising (BM3D) and the proposed approach to the image.

Next, Cherenkov imaging of a breast phantom during a sliding-window IMRT treatment was performed with the following parameters: photon energy of 6 MV, radiation dose of 210 MU, dose rate of 600 monitor units per minute (MU/min), a fixed repetition rate of 360 Hz, and gantry angles of 270° and 90° used for medial and lateral tangent beamlets, respectively. The imaging geometry and the breast phantom used were the same as those shown in Fig. 1(a). Figure 3 shows the imaging results at five selected time points with each frame acquired at 30 AOCs. Comparing to the raw images with the hot pixels removed, the SNR was averagely increased by 39.1% (±4.66%) using the BM3D method, and further increased by 247.6% (±35.56%) using the proposed one. It can be found from Fig. 3(c) that, the stray x-ray noise inside and outside the irradiated parts are fundamentally alleviated while the target edges and penumbra regions are well preserved. The heterogenous distributions of Cherenkov light as presented in the middle frame could be ascribed by the variations associated with the surface height and surface angle, which has been reported to be addressable in previous work [1].

Fig. 3.

Cherenkov imaging results of a breast phantom at five time points of a customized IMRT treatment: (a) raw images with the hot pixels removed, and (b) – (c) processed results using BM3D and proposed approaches, respectively. Every column corresponds to different time points during the treatment.

The proposed method was further validated on CELI to assess the SNR for phosphorescent objects at various concentrations () and depths in tissue. The phosphorescent probe used in our experiments was Oxyphor PtG4, which has been well demonstrated for oxygen sensing in in-vivo CELI experiments [3, 14]. Eppendorf tubes containing 0.5-mL solution of Oxyphor of varying concentrations (i.e., tubes #1-#7 corresponds to 100, 70, 40, 20, 10, 5, and 1 μM) were positioned at different depths (0, 1, 2, and 3 cm) in a tissue-mimicking phantom [Fig. 4(a)], which consisted of 1% Intralipid and 1% porcine blood per unit volume of solids, with absorption and reduced scattering coefficients calibrated to be and at the emission peak of the Oxyphor (772nm). Images were captured by using the ICCD with 2×2 pixel hardware binning upon readout. An epi-illumination configuration was used, with the Linac gantry oriented at 145 deg and in the same side as the ICCD.

Fig. 4.

Investigation on image quality versus various target depth (0–3 cm) and PtG4 concentrations () ranging 1–100μM. (a) Roomlight image and (b) luminescence image recovered by using different methods. (c) Normalized profiles along the red dashed lines in (b). (d) Corresponding SNRs against different and target depths for the raw, recovered and ground truth images.

The depth of CELI with reasonable probe concentration was typically limited to a few millimeters [3,4]. The secondary process of Cherenkov absorption and re-emission by the Oxyphor molecular reporter typically weakens the luminescence signal about one order of magnitude lower than the original Cherenkov signal, although there is a major benefit of acquisition after the Linac pulses where Cherenkov occurs, so this allows the stray radiation noise to be minimal after the x-ray pulses. These CELI results were processed using the BM3D and proposed method, and here were compared in Fig. 4(b). The ground truth images were obtained by median filtering 10 frames acquired at 36 AOCs. Comparable performance was found within 1cm depth, e.g., an average discrepancy of 9.5% on PSNR and 6.2% on SSIM. With the increase of target depth, such discrepancies become considerable, e.g., PSNR of 85.1% for 2-cm depth and up to 111.7% for 3-cm depth. The Eppendorf tubes with last three concentrations are invisible in both the processed and ground truth images in 2-cm results, and only the tube with the highest concentration was visible at 3-cm depth, although the light was severely diffused. In these cases, the luminescence photons were considerably scattered and absorbed, leading to a level close to the background emissions. The photon-count histogram then typically exhibited a Gaussian distribution [4]. A histogram-based preprocessing was again performed to alleviate the background photons in a way akin to the hot-pixel removal by using the same threshold value. A further comparison between the 1-cm and 2-cm results for the most four concentrations is illustrated in the profile plot in Fig. 4(c). We calculated the SNRs versus varying depths and concentrations in Fig. 3(d). In our cases, the accepted SNR was leveled at 10 dB corresponding to a contrast-to-background ratio (CBR) of 1. In accordance with the criterion, the raw measurement affords an imaging depth of up to 1.5 cm for a of 100 μM, 1cm for 20 μM, and 0.5 cm for 10 μM. The imaging depths for 100 μM and 20 μM were extended to 2.0 cm and 1.5 cm by using the BM3D method, and further extended to 2.5 cm and 1.8 cm using the proposed method. With the proposed method, all the tubes with concentrations above 10 μM could be detected within 1.5-cm depth. The SNRs of the results recovered from proposed method were close to those of the ground truth yielding a discrepancy of 3.67% averaged over all the depths and concentrations. Comparing to the raw measurement, the proposed method extended the imaging depths by 66.7%, 80.0%, and 200.0% for PtG4 concentrations of 100μM, 20μM, and 10μM, respectively, averaged at 115.6%.

In summary, a photon-limited imaging strategy was proposed to allow for low-flux Cherenkov imaging and CELI that suffers from extremely low SNR due to intermixed Poisson statistical and stray radiation noise contributions. The method greatly benefits the real world applications that require fast and accurate imaging while having limited radiation dose, e.g., dosimetric verifications on dose-limited fractionated radiotherapy and molecular sensing during a fast treatment such as FLASH radiotherapy [13]. In our experiments, the recovered images show a slight “staircase effect” to varying extent, which was reported to be ameliorable by adding a -norm penalty on the wavelet transform in Eq. (6) [15]. To allow for 3D Cherenkov profile and simultaneously further eliminate the background noise by exploiting spatial-temporal correlation, a fast-gating camera can be adopted, e.g., the SPAD array [7]. Further validations on dosimetric accuracy are being compared in the recovered Cherenkov images and associated dose maps, through on-going study.

Funding.

National Natural Science Foundation of China (62175183, 62075156, 82172674, 82071971); The Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (Grant No. 20JCYBJC00090).

Footnotes

Disclosures. B. Pogue declares financial involvement in the Cherenkov imaging company DoseOptics as co-founder and president. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hachadorian RL, Bruza P, Jermyn M, Gladstone DJ, Pogue BW, and Jarvis LA, “Imaging radiation dose in breast radiotherapy by X-ray CT calibration of Cherenkov light,” Nat. Commun. 11, 1–9 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarvis LA, Hachadorian RL, Jermyn M, Bruza P, Alexander DA, Tendler II, Williams BB, Gladstone DJ, Schaner PE, Zaki BI, and Pogue BW, “Initial Clinical Experience of Cherenkov Imaging in External Beam Radiation Therapy Identifies Opportunities to Improve Treatment Delivery,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 109, 1627–1637 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pogue BW, Feng J, LaRochelle EP, Bruža P, Lin H, Zhang R, Shell JR, Dehghani H, Davis SC, Vinogradov SA, Gladstone DJ, and Jarvis LA, “Maps of in vivo oxygen pressure with submillimetre resolution and nanomolar sensitivity enabled by Cherenkov-excited luminescence scanned imaging,” Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2, 254–264 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.LaRochelle EPM, Shell JR, Gunn JR, Davis SC, and Pogue BW, “Signal intensity analysis and optimization for in vivo imaging of Cherenkov and excited luminescence,” Phys. Med. Biol. 63, 501–509 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andreozzi JM, Zhang R, Glaser AK, Jarvis LA, Pogue BW, and Gladstone DJ, “Camera selection for real-time in vivo radiation treatment verification systems using Cherenkov imaging,” Med. Phys. 42, 994–1004 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirmani A, Venkatraman D, Shin D, Colaço A, Wong FN, Shapiro JH, and Goyal VK, “First-Photon Imaging,” Science 343, 58–61 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shin D, Xu F, Venkatraman D, Lussana R, Villa F, Zappa F, Goyal VK, Wong FN, and Shapiro JH, “Photon-efficient imaging with a single-photon camera,” Nat. Commun. 7, 1–8 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X, Shi J, Sun L, Li Y, Fan J, and Zeng G, “Photon-limited single-pixel imaging,” Opt. Express 28, 8132–8144 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li ZP, Ye JT, Huang X, Jiang PY, Cao Y, Hong Y, Yu C, Zhang J, Zhang Q, Peng C, Xu F, and Pan JW, “Single-photon imaging over 200 km,” Optica 8, 344–349 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu C, Liu J, Huang X, Li ZP, Yu C, Ye JT, Zhang J, Zhang Q, Dou X, Goyal VK, Xu F, and Pan JW, “Non-line-of-sight imaging over 1.43 km,” PNAS 188, e2024468118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harmany ZT, Marcia RF, and Willett RM, “This is SPIRAL-TAP: Sparse Poisson intensity reconstruction algorithms-theory and practice,” IEEE Trans Image Process 21, 1084–1096 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buades A, Coll B, and Morel J-M, “A non-local algorithm for image denoising,” IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 2, 60–65 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dabov K, Foi A, Katkovnik V, and Egiazarian K, “Image denoising by sparse 3-d transform-domain collaborative filtering,” IEEE Trans. Image Process. 16, 2080–2095 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cao X, Zhang R, Esipova TV, Allu SR, Ashraf R, Rahman M, Gunn JR, Bruza P, Gladstone DJ, Williams BB, Swartz HM, Hoopes PJ, Vinogradov SA, and Pogue BW, “Quantification of Oxygen Depletion During FLASH Irradiation In Vitro and In Vivo,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 111, 240–248 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brůža P, Lin H, Vinogradov SA, Jarvis LA, Gladstone DJ, and Pogue BW, “First-photon imaging via a hybrid penalty,” Opt. Lett. 41, 2986–2989 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng X, Zhao XY, Li LJ, and Sun MJ, Photonics Res. 8, 325–330 (2020). [Google Scholar]