Abstract

Background

Opioids are a common treatment for older adults living with pain. Given high rates of polypharmacy and chronic comorbidities, older adults are at risk of opioid overdose. Evidence is now available that take-home naloxone (THN) supports reduction of opioid-related harms. It is unknown what THN initiatives are available for older adults, especially those living with chronic pain.

Objective

To summarize the literature regarding THN, with a focus on older adults using opioids for pain, including facilitators of and barriers to THN access, knowledge gaps, and pharmacist-led initiatives.

Data Sources

A scoping review, guided by an established framework and PRISMA-ScR guidelines, was performed. Methods involved searching 6 bibliographic databases (MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, APA PsycINFO, Web of Science Core Collection, and PubMed), reference harvesting, and citation tracking. Searches were conducted up to March 2023, with no date limits applied; only English publications were included.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Study eligibility was determined according to preset criteria, including age; discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus. Data were extracted and categorized through thematic analysis.

Data Synthesis

Four studies met the eligibility criteria. All 4 studies detailed THN programs in primary care settings involving older adults taking opioids for pain management. Two of the studies highlighted patient-specific risk factors for opioid overdose, including concomitant use of benzodiazepines and/or gabapentinoids, mean morphine milligram equivalents per day of at least 50, and previous opioid overdose. Two of the studies assessed patient knowledge of opioid overdose management and attitudes toward THN. Educational programs increased patients’ interest in THN.

Conclusions

The literature about THN for older adults living with pain is limited, and no literature was found on pharmacist-led initiatives in this area. Future research on THN provision for older adults, including pharmacist-led initiatives, could help to optimize care for older adults living with pain.

Keywords: take-home naloxone, older adults, pain, opioids, harm reduction, special population

RÉSUMÉ

Contexte

Les opioïdes sont un traitement courant pour les personnes âgées souffrant de douleur. Compte tenu des taux élevés de polypharmacie et de comorbidités chroniques, les personnes âgées courent un risque de surdose d’opioïdes. Il est désormais prouvé que la distribution de trousses de naloxone contribue à la réduction des méfaits liés aux opioïdes. On ne sait pas quelles initiatives de distribution de trousses de naloxone existent pour les personnes âgées, en particulier celles souffrant de douleurs chroniques.

Objectif

Résumer la documentation concernant la distribution des trousses de naloxone chez les personnes âgées qui utilisent des opioïdes contre la douleur, y compris les facilitateurs et les obstacles à l’accès aux trousses, les lacunes dans les connaissances et les initiatives menées par les pharmaciens.

Sources des données

Un examen de la portée, guidé par un cadre éprouvé et les lignes directrices PRISMA-ScR, a été réalisé. Les méthodes impliquaient la recherche dans 6 bases de données bibliographiques (MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, APA PsycINFO, Web of Science Core Collection et PubMed), la récolte de références et le suivi des citations. Les recherches ont été effectuées jusqu’en mars 2023, sans limites quant à la date; seules les publications en anglais ont été incluses.

Sélection des études et extraction des données

L’admissibilité à l’étude a été déterminée selon des critères prédéfinis, notamment l’âge; les divergences ont été résolues par discussion et consensus. Les données ont été extraites et catégorisées grâce à une analyse thématique.

Synthèse des données

Quatre études répondaient aux critères d’admissibilité. Les 4 études ont détaillé des programmes de distribution de trousses de naloxone dans des établissements de soins primaires chez les personnes âgées prenant des opioïdes pour gérer la douleur. Deux des études ont mis en évidence des facteurs de risque spécifiques aux patients en matière de surdosage aux opioïdes, notamment l’utilisation concomitante de benzodiazépines et/ou de gabapentinoïdes, une moyenne d’équivalents en milligrammes de morphine par jour d’au moins 50 et un surdosage antérieur aux opioïdes. Deux des études ont évalué les connaissances des patients en matière de gestion des surdosages aux opioïdes et leur attitude envers la distribution de trousses de naloxone. Les programmes éducatifs ont accru l’intérêt des patients pour les trousses de naloxone.

Conclusions

La documentation sur la distribution de trousses de naloxone chez les personnes âgées souffrant de douleur est limitée et aucune littérature n’a été trouvée sur les initiatives menées par les pharmaciens dans ce domaine. Les recherches futures sur la distribution de trousses de naloxone aux personnes âgées, y compris les initiatives menées par des pharmaciens, pourraient contribuer à optimiser les soins aux personnes âgées souffrant de douleur.

Mots-clés: trousses de naloxone, personnes âgées, douleur, opioïdes, réduction des méfaits, population particulière

INTRODUCTION

Pain management in older adults is complex and must be highly individualized because of age-related physiologic changes, as well as the high prevalence of medical comorbidities.1–4 Given that older adults represent the fastest-growing segment of the population and that 4 out of 5 older adults experience pain, there is a pressing need to optimize pain management for this demographic.5–7 Specifically, there is growing evidence against the long-term use of opioids for treatment of chronic pain, especially in older adults, because of the adverse effects of these medications, including cognitive slowing, falls, and respiratory depression.8,9 In a report published by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction, researchers reported that approximately 44% of adults aged 55 years or older used opioids, with 1.1% of this group taking opioids daily.10

Opioid-related deaths are on the rise worldwide, and older adults are not exempt from this crisis.11 According to data from the National Vital Statistics System of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between 2000 and 2020, drug overdose–related deaths among adults aged 65 and older increased from 2.4 to 8.8 deaths per 100 000 people.12 The current mortality rate may be even greater because of the temporary closure of community harm reduction services during the COVID-19 pandemic.13

Naloxone is an opioid antagonist that temporarily reverses the effects of opioid toxicity.14 Older adults are at increased risk of experiencing opioid toxicity because of chronic comorbidities, receipt of high opioid doses and long-acting formulations, polypharmacy with central nervous system (CNS) depressants, and age-related physiologic and pharmacokinetic changes, including reduced drug metabolism and elimination.15,16

Although take-home naloxone (THN) programs have been established to reduce opioid-related deaths, primary care providers, physicians, and nurses are hesitant to recommend and prescribe THN out of fear of stigmatizing patients and because of uncertainty surrounding the prioritization of patient populations.17,18 Pharmacists are well positioned to fill this treatment gap by offering and providing THN.19 With many pharmacists working toward making THN distribution a standardized practice, it is clear that pharmacists have an integral role in educating patients and their loved ones, other health care professionals, and the community about the importance of THN in reducing opioid-related deaths.20

A growing body of research exists on THN programs for adults with opioid use disorder; however, limited research has been conducted on THN for older adults who are using opioids for pain.21–23 The 2020 Canadian national consensus guidelines for naloxone prescribing by pharmacists recommend THN for individuals with a history of opioid overdose, those who take long-term or high doses of opioids, and those using concomitant sedatives such as benzodiazepines and CNS depressants; however, these guidelines do not specifically address THN in older adults living with pain.24

According to best practices developed using a Delphi approach, THN should be offered to patients with any type of pain during opioid initiation, with active discussions continuing throughout treatment.25 Because opioid overdoses can happen at any time and anywhere, ongoing overdose education and THN training for patients and their families, friends, and/or care providers, are timely and targeted interventions that could save lives.26,27 Given the rise in admissions to hospital emergency departments and unintentional drug overdoses among older adults living with pain, additional research specific to this population is warranted.28,29

This scoping review was undertaken to identify and synthesize existing literature about THN access and use among older adults living with pain. The researchers sought to answer the following question: What is known about take-home naloxone for older adults living with pain? More specifically, this study aimed to determine facilitators of and barriers to THN, to identify pharmacist-led THN initiatives, and to describe the current state of THN access and use in Canada, all in the context of older adults living with pain.

METHODS

This scoping review was guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s framework30 and PRISMA-ScR guidelines.31 The review included literature describing THN access and use among adults aged 60 years or older living with any type of pain. We selected age 60 years or older as one of the inclusion criteria based on the mean age of study participants observed during prescreening of referenced articles. All peer-reviewed sources, including quantitative or qualitative manuscripts, conference abstracts, editorials, case reports, mixed-methods reports, textbook chapters, and grey literature, were considered in the scoping review, provided they were written in English. No date limits were applied because we wanted to comprehensively capture all relevant and available literature. Studies or other literature were excluded if they primarily focused on opioid use disorder, because THN programs are often readily available for this population.

Six bibliographic databases were searched: MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), Scopus, APA PsycINFO, Web of Science Core Collection (Clarivate), and PubMed. In addition, reference harvesting and citation tracking were performed in the Web of Science platform for peer-reviewed sources and grey literature. The search strategy for each database was created by R.R.D.C. and reviewed by K.H., E.M.Y., and a librarian specialist (see Appendix 1 for an example of the comprehensive search strategy). The search strategies were refined through team discussions. R.R.D.C. conducted the searches between February 27 and March 7, 2023, and used Zotero software (Corporation for Digital Scholarship) for citation management.

R.R.D.C. imported the citations into Covidence software for deduplication and screening. R.R.D.C. and K.H. independently used a 2-step process for screening, first considering titles and abstracts only and then moving to review of full-text manuscripts. The reviewers were not blinded to author names or journal titles. The authors discussed any discrepancies identified by Covidence at both the title and abstract reviewing stage and the full-text manuscript reviewing stage.

A data collection form was developed by R.R.D.C. using Arksey and O’Malley’s framework30 to determine which variables to extract, with the inclusion of key finding fields based on the study objectives. R.R.D.C. performed a data extraction test of 10 articles, and revisions were made on the basis of this testing. The authors iteratively improved the data extraction form to include the following data fields: study title, author, year of publication, study type, country of origin, objective(s), population studied, sample size, methods, intervention, comparator, duration of intervention, and outcome(s) studied. The form also included key findings relevant to THN access and use among older adults living with pain, including medical risk factors of the studied cohort; barriers to, facilitators of, and knowledge gaps related to THN; and details about the respective THN programs. R.R.D.C. then extracted information from the remaining full-text manuscripts by accounting for each field. Once data extraction was complete, the data were reviewed by K.H. and E.Y.M.

Given the nature of a scoping review, the authors did not critically appraise the literature identified, which is consistent with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework.30 Results from the data extraction were categorized through a narrative summary and thematic analysis.

RESULTS

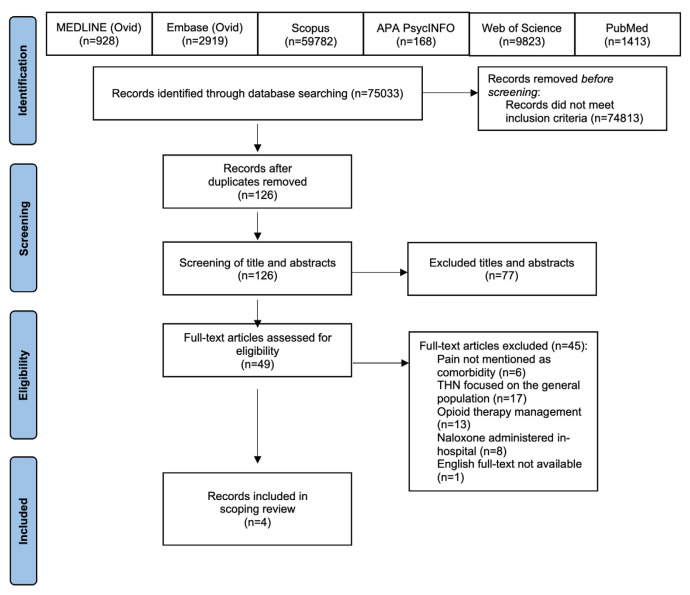

The comprehensive search yielded 75 033 studies from all peer-reviewed sources and grey literature, inclusive of reference harvesting and citation tracking. The Covidence software found 89 duplicates, which were removed. R.R.D.C. and K.H. manually removed 5 article duplicates not automatically removed by the software. After deduplication and exclusion of additional articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria, 126 articles were screened, and 49 full-text articles were reviewed. A total of 4 studies were included in the scoping review (Figure 1), 2 interventional and 2 non-interventional or descriptive studies (Appendix 2). The studies originated in or had corresponding authors from the United States (n = 3) or Australia (n = 1), with included items published from 2018 to 2021. The emerging themes summarized here include the types of THN programs, the patient-specific opioid overdose risk factors, and the factors contributing to THN access and use.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. THN = take-home naloxone.

Take-Home Naloxone Programs

All 4 articles described THN programs involving older adults in primary care settings, with 1 study also including home health workers (licensed nurses and social workers).32–35 The mean age of older adult patients ranged from 60.1 to 80.3 years.32–35 Sample sizes ranged from 31 to 208 participants.32–35 In terms of study design, there were 2 educational intervention studies, 1 retrospective chart review, and 1 prospective cohort study. Two of the 4 studies assessed patient knowledge of opioid overdose management and attitudes toward THN; both noted increased interest in obtaining THN after the educational intervention.32,33 In these 2 studies, the participants were primarily female (66% and 87%, respectively) and primarily white.32,33

Medical History and Characteristics

Most articles (n = 3) detailed patient demographic characteristics, including medical histories and opioid toxicity–related risk factors. Two of these 3 studies discussed opioids used for pain, including oxycodone (n = 2), codeine (n = 1), fentanyl (n = 1), hydrocodone (n = 1), and morphine (n = 1).33,35 Two studies highlighted patient-specific risk factors for opioid toxicity, including concomitant use of benzodiazepines and/or gabapentinoids (n = 2), taking more than 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day (n = 2), and previous history of opioid overdoses (n = 1).34,35

Barriers

All 4 studies reported barriers to THN for older adults. The 3 most frequently cited barriers were the need for further education and training (n = 3), concerns over THN cost (n = 2), and coprescribing and documenting THN use (n = 1), all from the perspective of patient respondents. After completing one-on-one patient education sessions on opioid overdose management and THN, Whittington and others32 reported that 70% of respondents (n = 114) did not obtain THN according to 5 themes: a lack of perceived utility (69.3%), patients forgetting about THN (20%), THN kit costs (8%), pharmacy access (3.5%), and concerns about THN-related adverse effects (0.9%).

Facilitators

Three of the studies mentioned facilitators of THN for older adults living with pain. These facilitators included THN education and training for older adults (n = 3), patient interest in obtaining THN (n = 3), and patient comfort in discussing THN (n = 1). Although only 8 patients (5.2%) reported having THN before the educational intervention, Whittington and others32 noted that one-on-one patient education increased THN attainment by 25.4%. In another study, after educating patients living with chronic noncancer pain, Nielson and others35 reported that more than half of respondents believed that THN coprescribed with opioids was a “good” or “very good idea”, with another 60% of patients reporting they “would expect [THN] to be offered” or “would appreciate being offered [THN]”.

Knowledge Gaps

Two out of 4 studies detailed knowledge gaps among older adults taking opioids for pain. Before the educational intervention, patient groups were assessed on their baseline knowledge of opioids, the signs and symptoms of overdose, and THN.33,35 Pre-education baseline scores among older adults were 39.4% and 45%, respectively, with more than half of respondents reporting that they had never heard of THN.33,35 Nielson and others35 noted that 8% of participants (n = 16) reported experiencing previous opioid overdose, and nearly 15% of patients (n = 30) reported experiencing at least 1 descriptor of opioid overdose previously, specifically drowsiness and confusion (n = 22), unconsciousness/difficulties waking up (n = 8), and blue lips (n = 2). A prospective educational intervention was conducted in the United States to educate home health workers and their older adult clients using opioids about overdose management and THN utility.33 Overall, home health workers believed their older adult clients had limited knowledge about the risks of opioids, the purpose and means of accessing THN, and how and when to use THN. Despite a 51.2% increase between pre-education and post-education test scores, none of the older adults obtained THN, with 38% reporting they “did not think [they] needed it”.33

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first literature summary about THN focused on older adults living with pain. Because the number of peer-reviewed publications meeting the inclusion criteria was limited, this review highlights the lack of priority given to THN initiatives focused on older adults living with pain and demonstrates the need for innovative work in this area. The literature identified was from the United States and Australia; thus, outcomes discussed here are likely transferable to Canada, given similar economic size and health care resources.36 We identified a range of patient-specific knowledge gaps and logistic barriers. Further work to address these barriers could include the creation and dissemination of a THN risk assessment tool that health care professionals could use to assess patients in terms of their need for THN. Additionally, health care professionals’ efforts focused on educating older adult patients about the benefits of THN may help to increase patient buy-in to this type of therapy. THN programs are often readily available to individuals living with opioid use disorder; however, awareness about the role of THN for patients living with pain and continuing education for health care professionals specifically focused on this area are lacking and represent key reasons why we undertook this work.37

Older adults (age 65 years or older) make up nearly 20% of Canada’s total population.38 More than half of older adults suffer from pain, and pain is one of the top concerns for patients seeking care in Canada.39,40 With polypharmacy rates highest among those 65 years or older, the use of excessive or unnecessary medications increases the risk of adverse drug effects, including opioid-related harms.41 For example, there were 1789 apparent opioid overdose deaths, some involving pharmaceutical-grade opioids, among Canadians aged 60 years or older between January 2018 and September 2022.42 Although the Government of Canada pledged $20 million to help communities respond to increasing opioid-related overdoses, for example by enhancing awareness of and access to THN, to our knowledge, no programs are specifically targeted toward older adults.43 The 2017 Canadian Guideline for Opioids for Chronic Noncancer Pain44 recommends providing THN for individuals who are identified as being at risk for opioid overdose, specifically those taking high doses of opioid (e.g., > 50–90 MME) and those with underlying medical comorbidities; however, similar to the 2020 Canadian national consensus guidelines for naloxone prescribing by pharmacists,24 these guidelines do not explicitly include older adults.44 Thus, opportunities exist to improve THN initiatives, awareness, and availability for older adults living with pain.

This scoping review had some limitations. The searches were limited to a finite set of bibliographic databases, and only peer-reviewed sources written in English were included in the summary. Although we strived to develop a comprehensive review, there is a possibility that the searches did not identify all pertinent work. Additionally, these were very focused searches that excluded sources if the research was incomplete, if results could not be identified, or if the literature focused on in-hospital naloxone administration or THN programs for older adults that did not specify pain as a comorbidity. Although most studies took place in primary care settings, none described pharmacist-led programs or THN efficacy for managing opioid overdose in older adults living with pain. With no randomized controlled trials identified, further research should systematically evaluate THN programs and educational interventions for the aging population. Given the paucity of literature available on this topic, the authors were limited to performing a scoping review rather than a systematic review. No critical appraisal was conducted on the quality of research, because the focus was to identify and discuss the nature and extent of research available. As such, this scoping review describes the literature relevant to THN access and use among older adults living with pain. The review protocol followed Arksey and O’Malley’s framework and PRISMA-ScR guidelines.30,31

Pharmacists have an opportunity to fill this care gap for the underprioritized aging population, especially those living with pain, by offering THN and providing education on the role of THN in opioid overdose. Pharmacists are highly respected medication management experts with a growing scope of practice.45 Pharmacists interact with patients up to 10 times more frequently than family physicians, and are therefore well positioned to identify patients with opioid overdose risk factors, to increase patient awareness of opioid risks and the role of THN, and to implement THN programs in their respective practices.46 One example of THN provision that targets patients living with chronic pain comprises the services offered through the USask Chronic Pain Clinic (UCPC). Beyond offering education and support related to chronic pain management, the UCPC clinical pharmacists assess patients’ familiarity with THN and provide the individuals with THN training and supplies as appropriate.47 In some provinces, such as Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan, pharmacists have an opportunity to register their organizations (e.g., community pharmacies, primary care clinics), which allows them to offer free THN training and kits, without prescription.48,49 Additionally, in Saskatchewan, participating pharmacies receive a $15 reimbursement for each THN kit provided to eligible patients.50

CONCLUSION

The literature about THN focused on older adults living with pain is limited. This review can be distinguished from previous literature by its focus on THN for older adults living with pain. Despite a focused search, to our knowledge there is no literature on pharmacist-led THN initiatives in this area. Given the novel nature of this topic, future areas of research could include pharmacist-led interventions to identify older adults at risk of opioid overdose, development of educational initiatives to meet the diverse needs of older adults, and evaluation of the effectiveness of THN for managing opioid overdose in older adults, all in the context of those living with pain.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend gratitude to the College of Pharmacy and Nutrition, University of Saskatchewan, for coordinating this directed research project and the guidance received by the learning support librarian, Vicky Duncan.

APPENDIX 1. Example search strategy

Ovid MEDLINE® 1946 to February Week 3 2023 (performed on February 7, 2023)

“naloxone” or “take home naloxone” or “take-home naloxone” or “THN” or “Narcan”

“narcotic antagonist” or “narcotic blocker” or “opioid antagonist” or “opioid blocker”

1 or 2

exp “pain” or “chronic pain” or “chronic non cancer pain” or “chronic non-cancer pain” or “CNCP” or “acute pain”

“pain management” or “long-term pain” or “long term pain” or “geriatric pain” or “hospice” or “palliative”

4 or 5

exp opioid/

“Opioid toxicity” or “opioid overdose” or “overdose” or “opioid abuse” or “opioid poisoning”

“drug toxicity” or “drug overdose” or “drug abuse” or “drug poisoning”

“respiratory depression” or “respiratory insufficiency”

7 or 8 or 9 or 10

“elderly” or “older” or “geriatric” or “aged”

3 and 6(additional limits: all aged (65 and over), humans, English

3 and 6 and 11 (additional limits: all aged (65 and over), humans, English

3 and 6 and 12 (additional limits: all aged (65 and over), humans, English

3 and 6 and 11 and 12 (additional limits: all aged (65 and over), humans, English

“pharmacist” or “pharmaceutical services” or “pharmacist-led” or “pharmacist led”

“health services accessibility”

17 or 18

3 and 6 and 17 (additional limits: all aged (65 and over), humans, English

3 and 6 and 19(additional limits: all aged (65 and over), humans, English

3 and 6 and 11 and 17 (additional limits: all aged (65 and over), humans, English

3 and 6 and 11 and 19 (additional limits: all aged (65 and over), humans, English

“Canada”

3 and 6 and 17 and 24

3 and 6 and 19 and 24

APPENDIX 2. Characteristics of included studies

| Authorsa | Year | Location | Population Studied and Setting | Design | Study Objective(s) | Key Findingsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventional studies | ||||||

| Whittington et al.32 | 2018 | United States | n = 162; mean age 63.2 years; patients enrolled in a primary care–based chronic pain management program and taking scheduled opioids daily | Intervention study educating participants about naloxone | To evaluate patients on pain management, overdose education, and naloxone attainment |

Barriers: unnecessary, forgot, cost, access, adverse effects Facilitator: n = 31 (20.2%) obtained naloxone after educational intervention; 25.4% overall attainment of naloxone |

| McQuade et al.33 | 2021 | United States | Older adults, n = 31, mean age 73.6 years; home health workers (licensed nurses and social workers), n = 44; outpatient primary care facility | Prospective educational study | To educate home health workers and their older adult clients on opioid overdose and naloxone utility |

Barriers: unnecessary, cost Facilitator: older adults, n = 8 (26%) obtained naloxone after educational intervention Knowledge gaps: pre-educational intervention knowledge (opioids and naloxone) score of older adults = 39.4/100 (SD 26.8), indicates limited baseline education; home health workers reported older adults had limited baseline knowledge |

| Non-interventional studies | ||||||

| Grey literature: Pravodelov et al. (conference abstract)34 | 2021 | United States | n = 100; mean age 80.3 years; older adults who received primary care at an urban geriatrics clinic and for whom at least one opioid for any indication such as pain was prescribed | Retrospective chart review | To assess adherence to guidance-based safer opioid prescribing among older adults |

Barriers: naloxone was prescribed for 17 patients, whereas only 3 had documentation of naloxone availability Relevant medical history: co-prescription of benzodiazepines (n = 25) and gabapentinoids (n = 38), average MME/day ≥ 50 (n = 9) |

| Qualitative: Nielson et al.35 | 2018 | Australia | n = 208; mean age 60.1 years; patients living with chronic noncancer pain and taking Schedule 8 opioids (fentanyl, morphine, oxycodone) ≥ 6 weeks | Prospective cohort study | To assess knowledge of opioid overdose and attitudes toward take-home naloxone |

Barrier: women were less open-minded to naloxone Facilitators: 60% of patients believed naloxone co-prescribed was good to very good, 60% reported that they “appreciate” and “expect” being offered naloxone Relevant medical history: co-prescription of benzodiazepines (n = 54), history of previous opioid overdose (n = 46), MME/day ≥ 100 (n = 73) Knowledge gaps: participants’ score on questionnaire of baseline knowledge (overdose signs and symptoms) = 4.5 out of 10 |

MME = morphine milligram equivalent, SD = standard deviation.

References are cited by numbers used in the main article.

Barrier = factor preventing older adults from obtaining take-home naloxone; facilitator = factor improving attainment of take-home naloxone among older adults.

Footnotes

Competing interests: For activities unrelated to the study reported here, Ryan Chan received undergraduate research funding (in the form of an Interdisciplinary Dean’s Summer Research Project Award) from the University of Saskatchewan’s College of Medicine and College of Pharmacy and Nutrition and has received speaking honoraria for community-based presentations with Big Brothers Big Sisters; he is also Vice President, Communications with the National Executive Council of the Canadian Association of Pharmacy Students and Interns, which receives sponsorship from the Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists. For activities unrelated to the study reported here, Katelyn Halpape has received grant funding from Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addictions Program and Indigenous Services Canada. She also received an honorarium from Hogrefe for work as a chapter editor on the Clinical Handbook of Psychotropic Drugs. No other competing interests were declared.

Funding: None received.

References

- 1. Chau DL, Walker V, Pai L, Cho LM. Opiates and elderly: use and side effects. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3(2):273–8. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Welch-Coltrane JL, Wachnik AA, Adams MCB, Avants CR, Blumstein HA, Brooks AK, et al. Implementation of individualized pain care plans decreases length of stay and hospital admission rates for high utilizing adults with sickle cell disease. Pain Med. 2021;22(8):1743–52. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnab092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Geriatrics Society Panel on Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1331–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hosseini F, Mullins S, Gibson W, Thake M. Acute pain management for older adults. Clin Med (Lond) 2022;22(4):302–6. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.22.4.ac-p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruckenthal P. Assessment of pain in older adults. In: Smith HS, editor. Current therapy in pain. W B Saunders; 2009. pp. 14–24. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Domenichiello AF, Ramsden CE. The silent epidemic of chronic pain in older adults. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;93:284–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A portrait of Canada’s growing population aged 85 and older from the 2021 Census. Government of Canada; 2022. [cited 2023 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-X/2021004/98-200-x2021004-eng.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ali A, Arif AW, Bhan C, Kumar D, Malik MB, Sayyed Z, et al. Managing chronic pain in the elderly: an overview of the recent therapeutic advancements. Cureus. 2018;10(9):e3293. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mandyam VC, Bruce RD. Chronic pain and opioid use in older people with HIV. Top Antivir Med. 2021;29(5):419–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patten SB. Chapter 2: Epidemiology of psychoactive substance use among older adults. In: Flint AJ, Merali Z, Vaccarino FJ, editors. Substance use in Canada: improving quality of life: substance use and aging. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction; 2018. pp. 25–35. [cited 2023 Aug 7] Available from: https://www.ccsa.ca/improving-quality-life-substance-use-and-aging-report. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marshall K, Hale D. Older adults and the opioid crisis. Home Healthc Now. 2019;37(2):117. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0000000000000743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kramarow EA, Tejada-Vera B. Drug overdose deaths in adults aged 65 and over: United States, 2000–2020. National Center for Health Statistics; (US): 2022. Nov 30, [cited 2023 Mar 31]. Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/121828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beiting KJ, Molony J, Ari M, Thompson K. Targeted virtual opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution in overdose hotspots for older adults during COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(11):E26–9. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cid A, Daskalakis G, Grindrod K, Beazely MA. What is known about community pharmacy-based take-home naloxone programs and program interventions? A scoping review. Pharmacy (Basel) 2021;9(1):30. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy9010030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dufort A, Samaan Z. Problematic opioid use among older adults: epidemiology, adverse outcomes and treatment considerations. Drugs Aging. 2021;38(12):1043–53. doi: 10.1007/s40266-021-00893-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mason M, Soliman R, Kim HS, Post LA. Disparities by sex and race and ethnicity in death rates due to opioid overdose among adults 55 years or older, 1999 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2142982. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Binswanger IA, Koester S, Mueller SR, Gardner EM, Goddard K, Glanz JM. Overdose education and naloxone for patients prescribed opioids in primary care: a qualitative study of primary care staff. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1837–44. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3394-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luther CD, Hughes TD, Ferreri SP. Naloxone prescribing to older adults in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(12):3681–3. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Daskalakis G, Cid A, Grindrod K, Beazely MA. Investigating community pharmacy take home naloxone dispensing during COVID-19: the impact of one public health crisis on another. Pharmacy (Basel) 2021;9(3):129. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy9030129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naloxone in the pharmacy setting. National Institute on Drug Abuse; (US): 2019. [cited 2023 Apr 20]. Available from: https://nida.nih.gov/nidamed-medical-health-professionals/science-to-medicine/medication-treatment-opioid-use-disorder/naloxone-in-pharmacy-setting. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kispert D, Carwile JL, Silvia KB, Eisenhardt EB, Thakarar K. Differences in naloxone prescribing by patient age, ethnicity, and clinic location among patients at high-risk of opioid overdose. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(5):1603–5. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05405-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cherrier N, Kearon J, Tetreault R, Garasia S, Guindon E. Community distribution of naloxone: a systematic review of economic evaluations. PharmacoEconomics Open. 2022;6(3):329–42. doi: 10.1007/s41669-021-00309-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Taliaferro L, McCarron M, Boylan PM, Bennett K, Shreffler M, Neely S, et al. Evaluation of naloxone co-prescribing rates for older adults receiving opioids via a meds-to-beds program. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2023;37(1):16–25. doi: 10.1080/15360288.2022.2140244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tsuyuki RT, Arora V, Barnes M, Beazely MA, Boivin M, Christofides A, et al. Canadian national consensus guidelines for naloxone prescribing by pharmacists. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2020;153(6):347–51. doi: 10.1177/1715163520949973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wenger LD, Doe-Simkins M, Wheeler E, Ongais L, Morris T, Bluthenthal RN, et al. Best practices for community-based overdose education and naloxone distribution programs: results from using the Delphi approach. Harm Reduct J. 2022;19(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s12954-022-00639-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Beauchamp GA, Cuadrado HM, Campbell S, Eliason BB, Jones CL, Fedor AT, et al. A study on the efficacy of a naloxone training program. Cureus. 2021;13(11):e19831. doi: 10.7759/cureus.19831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Doggui R, Adib K, Baldacchino A. Understanding fatal and non-fatal drug overdose risk factors: overdose risk questionnaire pilot study—validation. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:693673. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.693673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee EH, Park JO, Cho JP, Lee CA. Prioritising risk factors for prescription drug overdose among older adults in South Korea: a multi-method study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):5948. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wu A, Permanente K, Sterling V. Special considerations for opioid use in elderly patients with chronic pain. U S Pharm. 2018;43(3):26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Whittington R, Whittington K, Whittington J, Porter J, Zimmermann K, Case H, et al. One-on-one care management and procurement of naloxone for ambulatory use. J Public Health. 2018;40(4):858–62. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdy029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McQuade BM, Koronkowski M, Emery-Tiburcio E, Golden R, Jarrett JB. SAFE – Home Opioid Management Education (SAFE-HOME) in older adults: a naloxone awareness program for home health workers. Drugs Context. 2021;10:2021-7-6. doi: 10.7573/dic.2021-7-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pravodelov V, Scarbrough P, Chua S, Alford D, Lasser K. Adherence to guidelines for safer opioid prescribing and monitoring among patients in an urban safetynet geriatrics clinic [abstract] J Gen Intern Med 2021. 70 34145518 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nielsen S, Peacock A, Lintzeris N, Bruno R, Larance B, Degenhardt L. Knowledge of opioid overdose and attitudes to supply of take-home naloxone among people with chronic noncancer pain prescribed opioids. Pain Med. 2018;19(3):533–40. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnx021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.OECD health statistics 2023. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2023. [cited 2023 Apr 13]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Katzman JG, Takeda MY, Greenberg N, Moya Balasch M, Alchbli A, Katzman WG, et al. Association of take-home naloxone and opioid overdose reversals performed by patients in an opioid treatment program. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e200117. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Older adults and population aging statistics. Statistics Canada; 2023. [cited 2023 Apr 15]. Available from: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/subjects-start/older_adults_and_population_aging. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geri-RxFiles: assessing medications in older adults. 3rd ed. University of Saskatchewan, RxFiles Academic Detailing; Pain management in older adults. [cited 2023 Apr 13] Available from: https://www.rxfiles.ca/rxfiles/uploads/documents/gerirxfiles-pain.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Opioids prescribing in Canada: how are practices changing? Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2019. [cited 2023 Apr 13]. Available from: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/opioid-prescribing-canada-trends-en-web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 41.The dangers of polypharmacy and the case for deprescribing in older adults. National Institute on Aging; US: 2021. [cited 2023 Apr 15]. Available from: https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/dangers-polypharmacy-and-case-deprescribing-older-adults. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada. Government of Canada; 2023. [cited 2023 Apr 15]. Available from: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants/ [Google Scholar]

- 43.Federal actions on opioids to date. Government of Canada; 2023. [cited 2023 Apr 15]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/substance-use/problematic-prescription-drug-use/opioids/responding-canada-opioid-crisis/federal-actions/june_2020_pager-FINAL_.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, Buckley DN, Wang L, Couban RJ, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ. 2017;189(18):E659–E666. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pharmacists in Canada. Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2022. [cited 2023 Apr 17]. Available from: https://www.pharmacists.ca/pharmacy-in-canada/pharmacists-in-canada/ [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tsuyuki RT, Beahm NP, Okada H, Al Hamarneh YN. Pharmacists as accessible primary health care providers: review of the evidence. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2018;151(1):4–5. doi: 10.1177/1715163517745517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Halpape K, Jorgenson D, Ahmed A, Kizlyk K, Landry E, Marwah R, et al. Pharmacist-led strategy to address the opioid crisis: the Medication Assessment Centre Interprofessional Opioid Pain Service (MAC iOPS) Can Pharm J (Ott) 2021;155(1):21–5. doi: 10.1177/17151635211045950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Opioid use and overdose strategy. Government of Nova Scotia; 2023. [cited 2023 Jul 30]. Available from: https://novascotia.ca/opioid/ [Google Scholar]

- 49.Take home naloxone program sites. Government of Saskatchewan; 2023. [cited 2023 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.saskatchewan.ca/residents/health/accessing-health-care-services/mental-health-and-addictions-support-services/alcohol-and-drug-support/opioids/take-home-naloxone-program-sites. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Take home naloxone site registration. Government of Saskatchewan; 2023. [cited 2023 Jul 30]. Available from: https://redcap.rqhealth.ca/apps/surveys/?s=HNA339NPN8. [Google Scholar]