Abstract

The Simpson grading scale for the classification of the extent of meningioma resection provided a tremendous movement forward in 1957 suggesting increasing the extent of resection improves recurrence rates. However, equal, if not greater, movements forward have been made in the neurosurgical community over the last half a century owing to improvements in neuroimaging capabilities, microsurgical techniques, and radiotherapeutic strategies. Sughrue et al proposed the idea that these advancements have altered what a “recurrence” and “subtotal resection” truly means in modern neurosurgery compared with Simpson's era, and that a mandated use of the Simpson Scale is likely less clinically relevant today. A subsequent period of debate ensued in the literature which sought to re-examine the clinical value of using the Simpson Scale in modern neurosurgery. While a large body of evidence has recently been provided, these data generally continue to support the clinical importance of gross tumor resection as well as the value of adjuvant radiation therapy and the importance of recently updated World Health Organization classifications. However, there remains a negligible interval benefit in performing overly aggressive surgery and heroic maneuvers to remove the last bit of tumor, dura, and/or bone just for the simple act of achieving a lower Simpson score. Ultimately, meningioma surgery may be better contextualized as a continuous set of weighted risk–benefit decisions throughout the entire operation.

Keywords: Simpson Scale, meningiomas, recurrence, neuroimaging, subtotal resection, neurosurgery, gross total resection

Introduction

In 2010, the senior author and his colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco wrote a paper titled: “ The relevance of Simpson Grade I and II resection in modern neurosurgical treatment of World Health Organization Grade I meningiomas .” In this paper, they proposed that operating based on the Simpson grading scale using modern surgical techniques may not necessarily change the overall trajectory of the patients prognosis and likelihood of recurrence. 1 While Simpson's original seminal paper in 1957 suggested that increasing the extent of resection improves recurrence-free survival rates in patients with meningiomas, 2 many aspects of his grading scale required further clarification and rethinking to withstand the modern advancements in the neurosurgical field.

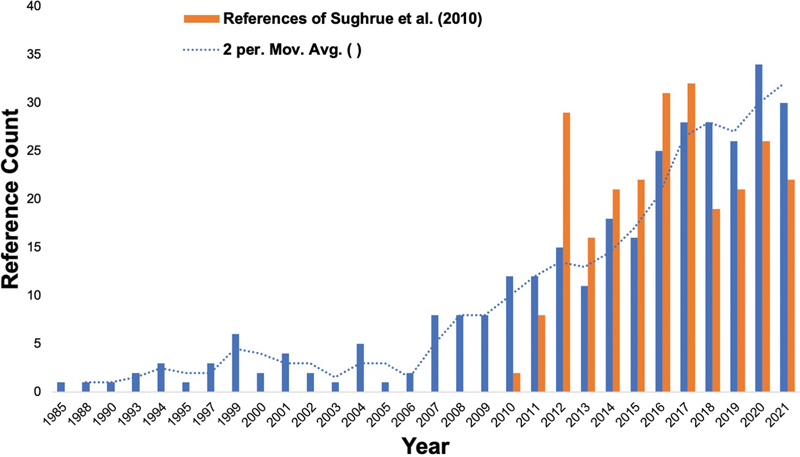

The paper by Sughrue et al 1 has been cited a total of 252 times as of 2021, and has been subject to numerous debates as seen in the recent published literature ( Fig. 1 ). Following 2010, several papers have similarly begun to re-examine and question the relevance of the neurosurgical community's focus on differentiating between specific grades on the Simpson Scale (grades I–V), 3 4 while several others in the midst of this discussion have instead pledged loyalty to the relevance of this scale within the modern era of neurosurgery, 5 6 7 or at least a modified version of this scale. However, as we continue to advance in our ability to extend the rate of resection, utilize the most advanced operative techniques, and understand the complex pathophysiological mechanisms of meningioma tumors, we must simultaneously continue to challenge our surgical principles in this field over time to optimize patient outcomes.

Fig. 1.

Superimposed trend of the discussions on the Simpson grading scale for WHO grade I meningiomas following the Sughrue et al publication in 2010. 1 Solid blue lines represent approximate publication counts of the Simpson Scale for WHO grade I meningiomas captured from a PubMed search utilizing the string (“meningioma” AND “simpson” AND “grade 1”). Dotted blue lines represent a 2-year moving average of solid blue line reference counts. Solid orange lines represent citations of the Sughrue et al's paper starting with its introduction. 1

In this article, we will discuss the progress in thinking since the paper by Sughrue et al 1 in 2010, how the field has evolved to have a more nuanced view of this topic, and what can and cannot be reasonably concluded based on these efforts. Furthermore, we will conclude by discussing where we think the real questions remain given the recently available literature.

What Does the Simpson Scale Implicate Today?

In Donald Simpson's landmark paper in 1957 titled “ The Recurrence of Intracranial Meningiomas After Surgical Treatment ,” 2 he hypothesized that the extent of resection correlated with the rate of recurrence in benign meningiomas. In a time prior to revolutionary advancements in microsurgical techniques, neuroimaging capabilities, and alternative therapeutic strategies, Simpson's observations were particularly important and were among the very few available studies formally supporting the benefits of aggressive surgical cytoreductive treatments for meningiomas, along with the highly influential Cushing monograph of meningiomas in 1938. 8 In his paper, Simpson reviewed 235 surgical meningioma cases from 1938 to 1954 at the Radcliffe Infirmary at Oxford ( Oxford series ) and 97 cases from 1928 and 1938 treated in London by Sir Hugh Cairns due to the presence of a longer follow-up period ( London Series ). To obtain a “convenient” grading system for operations of varying scope regarding the likelihood of recurrence following surgery, Simpson created a 5-point scale and attempted to correlate them with recurrence rates ( Table 1 ). Defined mostly as the return of clinical symptoms , recurrence rates of 9% (grade I), 16% (grade II), 29% (grade III), and 39% (grade IV) were demonstrated. Simpson grade V referred to decompression with or without biopsy. Of note, the 6-month mortality rate in the Oxford series was 13%, while it was 28% in the London series.

Table 1. Simpson grading scale for cranial meningiomas published in 1957 2 .

| Simpson Scale | Definition |

|---|---|

| Grade I | Macroscopically complete removal of tumor, including excision of (a) dural attachment and (b) underlying abnormal bone |

| Grade II | Macroscopically complete removal of tumor including (a) coagulation of dura with tumor extension |

| Grade III | Macroscopically complete removal of tumor |

| Grade IV | Partial removal of tumor |

| Grade V | Decompression with or without biopsy |

While scales can provide useful ways to understand complex quantitative data, they also can lend themselves to oversimplify complicated problems. Based on Simpson's paper, it is important to consider what it truly demonstrated as well as what cannot be reasonably concluded. It did illustrate that it is likely better to remove the dural base and underlying bone whenever surgically feasible. However, the degree and therefore benefit of bony resection in general is subjective in this context given that the amount of bone involvement by tumor tissue and therefore completeness of appropriate bone resection according to Simpson grade can substantially vary between surgeons. Furthermore, this paper did not clarify what a subtotal resection truly means and if they are all equal. This era predated the introduction of most intracranial imaging techniques, such as advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and a recurrence was defined as a return of clinical symptoms which likely referred to a substantial growth in tumor. In contrast, recurrence today for World Health Organization (WHO) grade I meningiomas illustrates a small interval change, often an asymptomatic MRI-defined growth, that provides adequate time to address these tumors, such as with radiosurgery.

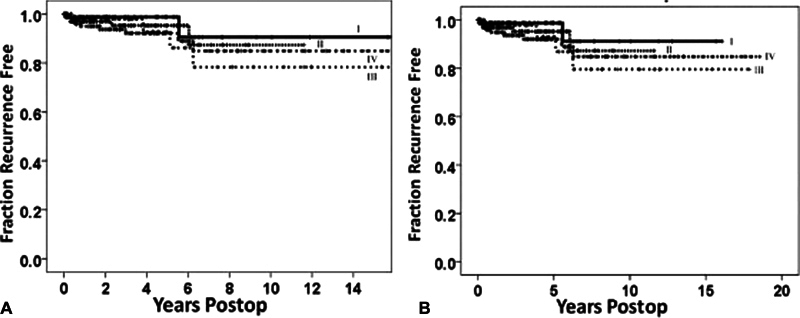

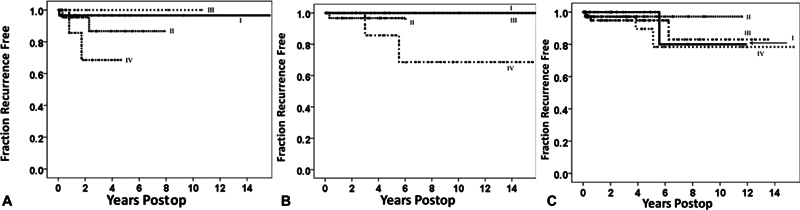

Given the numerous advancements in the field, including microsurgical techniques, modern neuroimaging capabilities, and alternative therapeutic strategies, Sughrue et al 1 published a paper in 2010 raising the point that a recurrence and subtotal resection had different clinical significances compared with Simpson's era. In a cohort of patients at the University of California, San Francisco, recurrence-free survival rates were analyzed with Kaplan–Meier analyses for all patients from 1991 to 2008 with histologically proven WHO grade I meningiomas undergoing craniotomy for resection without previous resection or radiosurgery. Rigorous statistical analyses revealed minimal but nonsignificant differences in recurrence-free survival rates between all Simpson grades (I–IV), as assessed with MRI and the surgeon's intraoperative assessments (median follow-up: 3.7 years, range: 0.5–18). Five-year recurrence-free survival rates were 95, 85, 88, and 81% for Simpson grades I–IV resections, respectively ( Fig. 2 ). Furthermore, subgroup analyses revealed no significant differences between Simpson grade based on tumor location, although Simpson grade IV resections visually appeared to show higher recurrence rates in the convexity and falx/parasagittal ( Fig. 3 ). Despite the presence or absence of any “statistically significant” relationships between Simpson grades, it was found that the benefits of a more aggressive surgical resection that also removed the dura (II) and/or underlying bone (I) were negligible compared with simply removing the tumor alone (III) or leaving traces of tumor along critical neurovascular and nerve structures (IV).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrating recurrence-free survival rates of patients with WHO grade I meningiomas: ( A ) recurrence-free survival for all patients according to Simpson grades I–IV resection. ( B ) Recurrence-free survival for patients with more than 4 years of postoperative follow-up ( n = 126) according to Simpson grades I ( n = 24), II ( n = 37), III ( n = 19), IV ( n = 46). No statistically significant difference was noted between Simpson grades in both figures. Figures taken from Sughrue et al, 1 published in the Journal of Neurosurgery , Volume 113, “The relevance of Simpson grade I and II resection in modern neurosurgical treatment of World Health Organization Grade I meningiomas,” pp. 1029–35, with permission from the Journal of Neurosurgery .

Fig. 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrating recurrence-free survival rates according to tumor location for patients with WHO grade I meningiomas: ( A ) patients with convexity meningiomas ( n = 77) undergoing Simpson grade I–IV resections. ( B ) Patients with falcine or parasagittal meningiomas ( n = 58) undergoing Simpson grade I–IV resections. ( C ) Patients with skull base meningiomas ( n = 189) undergoing Simpson grade I–IV resections. No statistically significant difference was noted between Simpson grades in any location. Figures taken from Sughrue et al, 1 published in the Journal of Neurosurgery , Volume 113, “The relevance of Simpson grade I and II resection in modern neurosurgical treatment of World Health Organization Grade Imeningiomas,” pp. 1029–35, with permission from the Journal of Neurosurgery .

In accordance with Simpson, Sughrue et al 1 concluded that removing more tumor whenever surgical feasible likely provides the greatest clinical benefit. However, the additional benefits of bony resection on top of a gross total resection alone is likely more modest than what Simpson's efforts indicate and may not justify the consequences of removing that bone just to obtain a better score on the Simpson Scale. Furthermore, it was suggested that the lack of substantial differences found between Simpson grades likely reflects the extremely limited amount of tumor commonly left behind in patients regardless of Simpson grade. Therefore, the introduction of numerous technological and surgical technique advancements in the field challenges the meaning of a modern subtotal or Simpson grade IV resection compared with previous times. 2

Subsequent Work and Significance of the Simpson's Scale

Re-examining the Simpson Grading Scale

Simpson originally expressed doubts in his paper regarding a lack of proof on the benefits of removing hyperostotic bone as well as the extremely large variability in what constitutes a subtotal Simpson grade IV resection, among several other concerns. More recently between 2010 and 2021, many authors have published work similarly reaffirming these doubts and the need to strictly adhere to the Simpson Scale in the modern neurosurgical era.

In 2012, Oya et al published a study including 240 patients with WHO grade I meningiomas and found no statistically significantly relationship in recurrence-free survival rates between Simpson grade I–III resections 4 (median follow-up of 3+ years for n = 126). Instead, the authors proposed the use of a cell proliferation index (MIB-1) as a more clinically relevant measure of risk of recurrence moving forward, 4 an idea which has been more recently supported by others as well. 9 These results illustrate that a complete resection offers great tumor control, but do not show any meaningful differences in recurrence rates when removing additional dura or bone. In 2016, Otero-Rodriguez et al published a study including 224 WHO grade I meningiomas examined between 1991 and 2011 and found similar results 3 (median follow-up: 5 year [range: 37–35]). When examining Simpson grades I–III on recurrence rates and recurrence-free survival in the convexity, falx/parasagittal, skull base, and tentorium, no significant differences were found based on Simpson grade in any single location. The authors concluded that complete tumor resection likely represents the most important factor of tumor control rather than Simpson grade, and this must be weighed against the risk of removing the bone or dura near critical structures or different locations (i.e., the skull base). 3

Elsewhere, in a larger study of 826 meningioma patients by Voß et al in 2017, tumor location has been rigorously examined regarding its prognostic value for Simpson classification. However, the multivariate results presented in this study suggested that only Simpson grade IV resections in the (1) convexity and (2) skull base were significantly correlated with increased recurrences (median follow-up: 4.17 years (range: 0–23.08)). Simpson grades I, II, and III all demonstrated similar rates of recurrence as shown in the above studies, and tumors in the falx/parasagittal were not correlated with recurrences. 10 In a subsequent study, the authors found that Simpson grade IV resections demonstrated the highest risk of recurrence and that dichotomizing the scale into Simpson grades I–III versus IV–V resections was more predictive of recurrence risk than dichotomization into Simpson grades I–II versus III–V resections. 11 Ultimately, the authors demonstrate the clinical benefit of removing maximal amount of tumor, especially in the convexity, but not large clinical benefits of more aggressive resections past simple gross removal of the tumor into the surrounding dural base and underlying bone.

Efforts to Create a More Nuanced Scale

Results from many of the previously mentioned studies above suggest limited applications of the Simpson Scale on a patient-by-patient basis, due to differences in both tumor-related factors (e.g., tumor location and size) 10 12 and patient-related factors (e.g., age or preoperative deficits). 13 As such, numerous authors have offered complementary additions or changes to the original Simpson Scale in hopes of expanding its applicability ( Table 2 ). 4 14 15 16 Such an idea is important given that we as a field will continue to improve our neuroimaging capabilities, 17 18 intraoperative tumor visualization tools, 19 and operative techniques capable of maneuvering in difficult to reach locations. 20 Briefly, many of these scales were created in hopes of addressing concerns of multicentric-diffuse patterns of meningiomatosis satellites by expanding the resection of the dural margin, 9 14 adapting the scale for location-specific uses like the cavernous sinus, 21 or incorporating advanced MRI to improve estimations of the extent of resection. 15 However, as has been demonstrated by Sughrue et al 1 and many others, these new additions remain extremely limited and also location-specific, 22 23 further emphasizing how a scale if mandated must be regularly altered to be clinically useful in specific scenarios. 24 Regardless of the scale implemented, results continue to reflect our main emphasis on and the benefits from removing as much tumor as possible whenever surgically feasible according to the associated risk profile.

Table 2. Modified scales based on the original Simpson grading system outlined in Table 1 .

| Simpson scale modifications | ||

|---|---|---|

| Grade 0 addition a | Modified Shinshu grade/Okudesa–Kobayashi grade b | MEGA radiologic grading c |

| Grade 0 (removal of additional dura margin of 2 cm 17 to 4 cm 15 ) |

Grade I (microscopic Simpson grade I) |

Grade I (radiologically complete removal of tumor with excision of its dural attachment and of any abnormal bone) |

| Simpson grade I | Grade II (microscopic Simpson grade II, but diathermy coagulation of dural attachment, not resection) |

Grade II (radiologically complete removal of the intradural tumor without resection of its dural attachments (e.g., invaded sinus, hyperostotic bone)) |

| Simpson grade II | Grade IIIA (microscopic Simpson grade III, but for intra- and extradural tumors) |

Grade III (partial removal leaving tumor in situ) |

| Simpson grade III | Grade IIIB (microscopic Simpson grade III resection of intradural tumor with no resection or coagulation of dura/extradural attachments or of any extradural attachments) |

Grade IV (simple decompression) |

| Simpson grade IV |

Grade IV

A

(microscopic Simpson grade IV resection leaving tumor around cranial nerves/blood vessels with removal of attachment) |

|

| Simpson grade V | Grade IVB (microscopic Simpson grade IV up to <10% tumor volume) |

|

| Grade V (microscopic Simpson grade IV leaving >10% tumor volume, or Simpson grade V) |

||

Abbreviation: MEGA, Meningioma Group Amsterdam Grading System of Meningioma Removal Based on Postoperative Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Column 1 illustrates an addition of a “Grade 0” to the Simpson Scale proposed by Borovich et al in 1965. 14

Column 2 summarizes a modified scale published by DeMonte et al in 1995 based on cavernous sinus meningiomas. 21

Column 3 illustrates a modified scale published by Slot et al 15 in World Neurosurgery , Volume 111, “Agreement between extent of meningioma resection based on surgical Simpson grade and based on postoperative magnetic resonance imaging findings,” pp. e856–862, Copyright Elsevier (2018), with permission from Elsevier.

Support of the Simpson Grading Scale

While a great deal of evidence has been published over the last decade questioning the clinical value in achieving different values on the Simpson scale, several authors have also recently published work claiming support of the scales' continued significance as well. Together, these studies largely provide similar arguments and employ similar mathematical techniques in grouping different grades together, which have been strongly reviewed previously, 24 25 and therefore we briefly outline the most recent literature below.

Studies Comparing GTR versus STR

Several recent studies have claimed that increasing the extent of resection past a Simpson grade IV resection results in superior recurrence-free survival rates. To illustrate this idea, these studies have generally grouped Simpson grades I–II or I–III as “GTR” for statistical comparison with Simpson grade IV as “STR.” 24 25 However, such statistical techniques reduces the scales' predictive value, 11 and more importantly, it transforms any questions surrounding possible clinical benefits of removing additional tumor, dura, and/or underlying bone into one that instead questions the need to remove more tumor or not .

In 2007, Natarajan et al examined 150 patients from 1991 to 2004 undergoing resection of petroclival meningiomas and categorized Simpson grade I–II resections as “GTR,” Simpson grade III–IV and >90% resection as “STR,” and Simpson grade III–IV and <90% resection as partial resection “PR.” These groups were later reduced into ultimately only complete versus incomplete resections. 26 Heald et al in 2013 reported on 183 patients with WHO grade I meningiomas between 2004 and 2012, and suggested that “Simpson's grading system… remains, in essence, as pertinent to the modern neurosurgeon as it was at its inception.” However, the authors only report significant benefits in 3-year progression/recurrence-free survival between Simpson grade I (95%) and grade IV (87%) resections, while they found no differences between Simpson grade I and grade II resections and did not study grade III resections (median follow-up: 2.94 years [range: 0.5–81.60]). Ultimately, these results demonstrate that subtotal resections may present a higher risk for recurrence compared with gross-total resections. 23 25 27

In a retrospective study of WHO grade I meningiomas undergoing resection from 2002 to 2007, Gallagher et al suggested that Simpson grading remains a significant predictor of progression-free survival (PFS) for WHO grade I meningiomas. 28 However, the authors only report 5-year recurrence/progression-free survival (RPFS) rates for Simpson grades I (96.8%), II (100%), IV (82.4%), and V (0%) (excluding grade III), and primarily suggest benefits in RPFS rates appear when considering gross total (98.9%) versus subtotal (82.7%) resections. The authors suggested differences in outcomes compared with Sughrue et al are due to their longer follow-up time (5 vs. 3.7 years) and their lack of preoperative embolization, as similarly proposed by Heald et al. 27 However, such points instead likely emphasize our ability to employ currently available techniques that makes a current Simpson grade IV resection much better than in Simpson's era. Furthermore, the authors even go on to recommend different postoperative imagining protocols to monitor the risk of recurrence based on if patients received gross total (I–III) or subtotal (IV–V) surgical resections ( Table 3 ).

Table 3. Studies introduced into the literature following the publication of Sughrue et al 1 in 2010 demonstrating recurrence-free survival rates according to the Simpson grade of resection for WHO grade I meningiomas .

| Study | Review period | Sample size ( N ) |

Follow-up period | Tumor location |

5-year recurrence/progression-free survival | 10-year recurrence/progression-free survival | Significant findings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median, y | (Convexity, falx/parasagittal, skull base, other) | Grade I (%) |

Grade II (%) |

Grade III (%) |

Grade IV (%) |

Grade I (%) |

Grade II (%) |

Grade III (%) |

Grade IV (%) |

||||

| Sughrue et al (2010) | 1991–2008 | 373 | 3.7 (range, 0.5–18) | All | 95 | 85 | 88 | 81 | – | – | – | – | Non statistically significant differences between WHO grades ( p > 0.05) |

| Van Alkemade et al (2012) a | 1985–2003 | 205 | 11 (range, 0–24) | All | 95 | 88 | 80 | 59 (IV/V) |

92 | 77 | 74 | 50 (IV/V) |

Increase in recurrence rates for increasing Simpson grade I–IV/V ( p < 0.001); nonsignificant differences in grades I vs. II or grades I vs. III on multivariate analyses ( p > 0.05) |

| Oya et al (2012) | 1995–2010 | 248 | Total group at least 6 months or more, n = 126 had 3+ years | All | 97.6 | 87.7 | 84.1 | 56.8 | – | – | – | – | Decreased RFS between Simpson grades IV vs. I–III ( p < 0.001), but not between Simpson grades I–III ( p = 0.07) |

| Hasseleid et al (2012) | 1990–2011 | 353 | 7.1 (range, 0.0–20.9) | Convexity | 100 | 97 (II/III) |

93 (IV/V) |

– | – | – | – | Significant differences in RFS for Simpson grade I vs. II–V ( p < 0.001), but not between II–V | |

| Heald et al (2014) | 2004–2012 | 183 | 2.94 (range, 0.5–81.60) | All | 95% (3 y) |

87% (3 y) |

– | 67% (3 y) |

– | – | – | – | Significant difference in PFS/RFS between Simpson grade IV and I resections ( p = 0.04), but not grade I vs. II resections ( p = 0.29) |

| Otero-Rodriguez et al (2016) | 1991–2011 | 224 | 5 (range, 37–35 (max–min)) | All | 97 | 95 | 98 | – | 90 | 83 | 96 | – | No statistically significant differences between Simpson grades I–III ( p = 0.413) |

| Gousias et al (2016) | 1996–2008 | 716 | 5.17 (mean 5.69 ± 4.03) | All | 99 | 95 | 88 (III/IV) |

95 | 90 | 80 (III/IV) |

Significant differences in PFS between grade I vs. II vs. III/IV, but not between grades III vs. IV | ||

| Gallagher et al (2016) |

2002–2007 | 145 | 5 (range, 0.5–11.17) | All | 96.8 | 100 | – | 82.4 | – | – | – | – | Significant differences between Simpson grades and gross total (I–III) vs. subtotal (IV–V) ( p < 0.05); differences between specific levels not mentioned |

| Nanda et al (2017) |

1995–2014 | 458 | 4.5 (range, 0.8–20.83) | All | 97 | 70 | 68 | 62 | 90 | 50 | 51 | 35 | Significant differences in median RFS across all Simpson grades I–IV ( p = 0.001) |

| Nanda et al (2017) |

1995–2014 | 458 | 4.5 (range, 0.8–20.83) | All | 74 (I/II) |

50 (III/IV) |

62 (I/II) |

32 (III/IV) |

Increased RFS for Simpson grade I/II vs. III/IV resections ( p = 0.005) | ||||

| Voß et al (2017) b c | 1991–2015 | 826 | 4.17 (range, 0–23.08) | All | 88 | 85 | 85 | 70 | 85 | 75 | 75 | 50 | grade IV significantly correlated with increased recurrence ( p < 0.001) |

| Voß et al (2017) b c | 1991–2015 | 826 | 4.17 (range, 0–23.08) | All | 80 (I/II) |

85 (III/IV) |

65 (I/II) |

80 (III/IV) |

PFI was longer for grades III–IV vs. I–II ( p = 0.01) | ||||

| Ehresman et al (2018) | 2007–2015 | 562 c | 2 y (508 patients, 88.8%) 3 (379, 66.3%) 4 (289, 50.5%) 5 (204, 35.7%) 6 (137, 24.0%) 7 (81, 14.2%) |

All | 92 | 91 | 86 | 75 | – | – | – | – |

Significant differences between Simpson grades I vs. IV (

p

= 0.0002) and

grades II vs. IV ( p = 0.002); no other significant differences between grades I–IV |

| Slot et al (2018) | 2005–2007 | 46 c | 3 mo | All | 9 | 19 | 29 | 39 | – | – | – | – | Similar agreement in grading between Simpson grade (neurosurgeon) and radiologic extent of resection (MRI) 72 hours and 3 months after surgery |

| Behling et al (2021) b | 2003–2017 | 1243 | 3.2 (range, 0.1–16.30) | All | 89 | 91 | 85 | 61 | 75 | 85 | 69 | 44 | Significant differences between Simpson grades IV vs. grades I, II, and III (each p < 0.0001); significant differences between grades III vs. I and III vs. II ( p < 0.05), but not between grades I vs. II ( p > 0.05) |

| Brokinkel et al (2021) | 1991–2018 | 939 c | 3.08 (range, 0–23.67) | All | (I–II) 88 |

(III–V) 77 |

(I–II) 78 |

(III–V) 66 |

PFI was longer for Simpson grades I–II vs. III–V ( p = 0.007) and between grades I–III vs. IV–V ( p = 0.001) | ||||

| Brokinkel et al (2021) | 1991–2018 | 939 c | 3.08 (range, 0–23.67) | All | (I–III) 86 |

(IV–V) 71 |

(I–III) 77 |

(IV–V) 65 |

Dichotomization into Simpson grades I–III vs. grades IV–V was more predictive of recurrences than into grades I–II vs. III–V; PFI was longer for Simpson grades I–III vs. IV–V ( p = 0.001) | ||||

| Brokinkel et al (2021) | 1991–2018 | 939 c | 3.08 (range, 0–23.67) | All | 92 | 86 | 84 | 70 | 85 | 73 | 71 | 69 | PFI was significantly different between Simpson grade I vs. IV, but not between grade I vs. grades II, III, or V |

Abbreviations: PFI, progression-free interval; PFS, progression-free survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival.

Recurrence-free survival estimated from reported recurrence rates.

Estimates taken from curves adjusted for WHO grade I meningioma.

Study that includes results based on additional meningiomas, such as WHO Grade II and/or III meningiomas, that could not be removed.

What Is the Interval Benefit of Surpassing Simpson Grade II Resections

One of the major conclusions made in the original paper by the senior author was to suggest that it may not be justified to remove the very last piece of bone all in hopes of just advancing from a Simpson grade II to a Simpson grade I resection when considering possible differences in recurrence rates ( Table 3 ). 1 Indeed, several recent studies have since similarly found negligible, and mostly nonsignificant, differences between these two grades, 3 10 27 29 with a recent study even showing better recurrence rates in Simpson grade II resections compared with grade I resections. 30 However, Gousias et al reported a twofold increase in recurrence rates on multivariate analyses between Simpson grade I and II resections when studying a large series of 901 patients with WHO grade I–III meningiomas with a median follow-up of 5.17 years (mean: 5.69 ± 4.03) (hazard ratio [HR]: 2.665; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.333–5.328; p = 0.006). 6 Of note, these results only translated to a 5% difference in 10-year PFS between Simpson grade I and grade II resections for WHO grade I meningiomas. The authors report that this difference increases to a 10% difference in 10-year PFS when also considering meningiomas of all WHO grades (Simpson grade I, 91.5% vs. Simpson grade II 81.2%), likely reflecting the point that the degree of resection has larger effects for higher grade tumors (WHO grade II–III). Results from this study demonstrate that for higher grade meningiomas it may indeed be worth the additional risk to remove the underlying bone, but this benefit is likely minimal for benign meningiomas. Furthermore, the authors show that in patients with clival/petroclival tumors in the skull base, more aggressive surgery to achieve a grade I resection may result in worse functional outcomes compared with other tumor locations as evidenced by postoperative KPS (Karnofsky Performance Scale) score. 6 31

In comparison to deep-seated skull base tumors, the most convincing evidence for clinically meaningful applications of Simpson grading scale comes with meningiomas of the convexity. Hasseleid and colleagues reported that their study in 2012 on 391 patients with WHO grade I–III meningiomas of the convexity was completed in response to our recently published paper in the same year (median follow-up: 7.1 years, range: 0.0–20.9). 5 7 Overall retreatment rates were 4.3% for WHO grade I meningiomas compared with 9.1% for grade II and 50% for grade III. To study retreatment-free survival by Simpson grade, the authors grouped together Simpson grades II–III and grades IV–V for statistical comparisons with Simpson grade I resections. On multivariate analyses, they found significantly decreased HRs for Simpson grade II–III and IV–V resections compared with Simpson grade I resections (HR: 6.4 and 15.2, respectively). Furthermore, conditional recursive partitioning analysis demonstrated only significant recurrence-free survival rates when comparing Simpson grade I versus grades II–V, but no differences between each Simpson grade II–V. Taken together, these results illustrated the importance of increasing the extent of resection with meningiomas specifically of the convexity , which is generally acknowledged to present less risks to the patient compared with other locations like the skull base. To date, this tumor location has provided the most valuable evidence of clinical benefits in removing the underlying abnormal bone during meningioma resection. 25 32

Interpretations Based on New Histological Classifications

It is important to note that majority of the studies above have been completed in a retrospective manner with analyses completed based on varying, and notably older , WHO grading classification systems. Several updated WHO guidelines for central nervous system tumors have been published since the first WHO classification which sought to organize meningiomas by tumor grade in 1993. 33 34 35 While the number of atypical meningiomas (grade II) were previously estimated to be around 7%, further modifications to the WHO grading criteria in 2007 increased this number to 20 to 35% of newly diagnosed meningiomas, with expected further increases since the 2016 grading criteria moving forward. 25 36 37 Most notably, previous grade I meningiomas with brain invasion have since been reclassified as grade II atypical meningiomas with or without other signs of atypia or anaplasia given the likely prognostic value of brain invasion regarding tumor recurrence. 30 38 39 Thus, although benign grade I meningiomas still remain the most prevalent, it is important to consider that a significant amount of previously analyzed grade I meningiomas are likely of higher grade and that higher grade is an independent predictor of worse outcomes irrespective of resection rates. 40 Furthermore, the role of primary or adjuvant radiation therapy for selected patients has been clearly demonstrated, such as with nonbenign meningiomas or in the case of subtotal resection, and this treatment option is strongly influenced by these grading differences. 25 30 32

These classification differences and the role of radiation therapy, although not considered in many previous studies, provide important factors to consider when attempting to understand the value of the Simpson Scale in modern neurosurgery. 30 Aside from the WHO grade, it is likely that there will be increased focus on molecular-based classifications which may assist in more individualized treatment options, such as with extent of resection (EOR) decisions. In addition to MIB-1 as discussed above, 9 TERT promotor mutations have gained considerable interest as an indicator of poorer prognosis irrespective of WHO grade, and this may be due to this molecular signature possibly representing an early step in malignant progression. 32 41 42 While other mutated genes have also been proposed, 32 few studies have rigorously examined the relationship between these molecular features and recurrence rates and this represents an important area of future study.

Who Is “Right” and What Should We Be Asking?

An important point to bring up concerns the idea of “statistical certainty.” 43 As with any measurement, there is some degree of uncertainty. Given that in neurosurgery, case series can oftentimes be limited in power and scope of sample sizes compared with large epidemiological studies, it can be problematic if we always compare percentages between studies that may not actually be statistically different. In turn, this often leads to an overestimation of effect sizes. Thus, what we can conclude about the Simpson Scale based on various results from the available literature is that there may be some benefit to its utilization, and it is probably better to remove as much tumor as possible ( Table 3 ). In fact, results from most articles presented above, both “for” or “against” the use of the Simpson Scale, generally seem to argue for this exact idea: taking more tumor results in decreased recurrence rates. 24 25 32 However, what the literature seems to suggest is that the interval benefit of taking that last bit of tumor, being additionally aggressive to drill the bone, and doing overly heroic maneuvers to get a “lower Simpson score,” should always be taken into the context of the risk and benefits of those maneuvers based on patient quality of life and functional outcomes.

One of the largest concerns in Simpson's original paper was that recurrence mainly occurred due to invasion of the dural venous sinuses. This idea is what largely led him to believe that also taking the abnormal bone and dura on top of a gross total resection was absolutely necessary if the sinus was invaded. However, stereotactic radiosurgery, stereotactic radiotherapy, and/or fractionated radiation therapy have all been recently coupled with advances in neuroimaging technologies to improve targeting methods capable of delivering highly precise doses of radiation with minimal risk to surrounding structures following a subtotal Simpson grade IV resection around the major sinuses. When analyzing 1,100 patients receiving subtotal resections for WHO grade I meningiomas in the skull base across nine recently published primary studies (2002–2014), Day and Halasz illustrated that postoperative fractionated stereotactic radiation therapy and/or Gamma Knife radiosurgery resulted in control rates between 92 and 100% at 5 years and 88 and 95% at 10 years. 44 In fact, primary treatments with radiosurgery can produce similar 7-year PFS rates as Simpson 1 resections (95 vs. 96%, p = 0.94). 45 Furthermore, improved understanding of prognostic risk factors of recurrence 9 46 can allow us to perform less aggressive and safer surgeries while offering delayed radiotherapeutic strategies at the time of recurrence.

With newer precise technologies that can identify asymptomatic tumor regrowth and noninvasively treat them, it is likely less severe and clinically meaningful to have a tumor recurrence in modern times. An alternative, and likely more important, discussion moving forward should include our need to think of tumor surgery as a continuous set of weighted risk–benefit decisions throughout the entire operation. Is it a guaranteed cure if you achieve a single point lower on the Simpson Scale and guaranteed recurrence if you do not? The literature seems to suggest the answer is no . Instead, with these extra steps, the benefit is at best a few points on the Simpson Scale.

Conclusion

What we can conclude about the Simpson Scale in the modern neurosurgical era is that there is likely some benefit to its utilization, especially in surgically accessible areas such as the convexity, and it is always better to remove as much tumor as surgically feasible, regardless of tumor type. However, the clinical benefit in overly aggressive meningioma surgery is likely not so great that it is justified to perform overly heroic actions to remove more tumor, dura, and underlying bone for the simple act of achieving a lower score on the Simpson Scale. With advancements in modern neuroimaging, microsurgical techniques, and radiotherapeutic strategies, a “subtotal resection” and tumor “recurrence” likely represent drastically different meanings and less severe clinical implications compared with when the Simpson Scale was first created. Instead, we must shift the debate away from questioning if this scale is still “relevant or not,” and instead move it toward discussion on the need for continuously making risk–benefit decisions throughout the entire meningioma surgery.

Conflict of Interest Michael Sughrue is the Chief Medical Officer and co-founder of Omniscient Neurotechnology and stakeholder. No products related to this were discussed in this paper. Nicholas Dadario has no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E.S.; methodology, M.E.S and N.D.; formal analysis, N.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.E.S and N.D.; writing—review and editing, M.E.S and N.D.; visualization, N.D.; supervision, M.E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Sughrue M E, Kane A J, Shangari G et al. The relevance of Simpson Grade I and II resection in modern neurosurgical treatment of World Health Organization Grade I meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2010;113(05):1029–1035. doi: 10.3171/2010.3.JNS091971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20(01):22–39. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.20.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otero-Rodriguez A, Tabernero M D, Munoz-Martin M C et al. Re-evaluating Simpson Grade I, II, and III resections in neurosurgical treatment of World Health Organization Grade I Meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2016;96:483–488. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oya S, Kawai K, Nakatomi H, Saito N. Significance of Simpson grading system in modern meningioma surgery: integration of the grade with MIB-1 labeling index as a key to predict the recurrence of WHO Grade I meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2012;117(01):121–128. doi: 10.3171/2012.3.JNS111945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasseleid B F, Meling T R, Rønning P, Scheie D, Helseth E. Surgery for convexity meningioma: Simpson Grade I resection as the goal: clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2012;117(06):999–1006. doi: 10.3171/2012.9.JNS12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gousias K, Schramm J, Simon M. The Simpson grading revisited: aggressive surgery and its place in modern meningioma management. J Neurosurg. 2016;125(03):551–560. doi: 10.3171/2015.9.JNS15754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heros R C.Editorial: Simpson grades J Neurosurg 201211706997–998., discussion 998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cushing H, Eisenhardt L. Meningiomas: their classification, regional behaviour, life history, and surgical end results. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1938;27(02):185. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maiuri F, Mariniello G, Peca C et al. Multicentric and diffuse recurrences of meningiomas. Br J Neurosurg. 2020;34(04):439–446. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2020.1754335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voß K M, Spille D C, Sauerland C et al. The Simpson grading in meningioma surgery: does the tumor location influence the prognostic value? J Neurooncol. 2017;133(03):641–651. doi: 10.1007/s11060-017-2481-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brokinkel B, Spille D C, Brokinkel C et al. The Simpson grading: defining the optimal threshold for gross total resection in meningioma surgery. Neurosurg Rev. 2021;44(03):1713–1720. doi: 10.1007/s10143-020-01369-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukushima Y, Oya S, Nakatomi H et al. Effect of dural detachment on long-term tumor control for meningiomas treated using Simpson grade IV resection. J Neurosurg. 2013;119(06):1373–1379. doi: 10.3171/2013.8.JNS13832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lemée J M, Corniola M V, Da Broi M et al. Extent of resection in meningioma: predictive factors and clinical implications. Sci Rep. 2019;9(01):5944. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42451-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borovich B, Doron Y, Braun J et al. Recurrence of intracranial meningiomas: the role played by regional multicentricity. Part 2: clinical and radiological aspects. J Neurosurg. 1986;65(02):168–171. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.65.2.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slot K M, Verbaan D, Bosscher L, Sanchez E, Vandertop W P, Peerdeman S M. Agreement Between extent of meningioma resection based on surgical Simpson Grade and based on postoperative magnetic resonance imaging findings. World Neurosurg. 2018;111:e856–e862. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.12.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinjo T, al-Mefty O, Kanaan I.Grade zero removal of supratentorial convexity meningiomas Neurosurgery 19933303394–399., discussion 399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dadario N B, Brahimaj B, Yeung J, Sughrue M E. Reducing the cognitive footprint of brain tumor surgery. Front Neurol. 2021;12:711646. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.711646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dadario N B, Sughrue M E. Should neurosurgeons try to preserve non-traditional brain networks? A systematic review of the neuroscientific evidence. J Pers Med. 2022;12(04):587. doi: 10.3390/jpm12040587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dadario N B, Khatri D, Reichman N, Nwagwu C D, D'Amico R S. 5-Aminolevulinic acid-shedding light on where to focus. World Neurosurg. 2021;150:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.02.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dadario N B, Zaman A, Pandya M et al. Endoscopic-assisted surgical approach for butterfly glioma surgery. J Neurooncol. 2022;156(03):635–644. doi: 10.1007/s11060-022-03945-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeMonte F, Smith H K, al-Mefty O. Outcome of aggressive removal of cavernous sinus meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1994;81(02):245–251. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.2.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanai N, Sughrue M E, Shangari G, Chung K, Berger M S, McDermott M W. Risk profile associated with convexity meningioma resection in the modern neurosurgical era. J Neurosurg. 2010;112(05):913–919. doi: 10.3171/2009.6.JNS081490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nanda A, Bir S C, Maiti T K, Konar S K, Missios S, Guthikonda B. Relevance of Simpson grading system and recurrence-free survival after surgery for World Health Organization Grade I meningioma. J Neurosurg. 2017;126(01):201–211. doi: 10.3171/2016.1.JNS151842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz T H, McDermott M W.The Simpson grade: abandon the scale but preserve the message J Neurosurg 2020. Oct 09 (e-pub ahead of print). 10.3171/2020.6.JNS201904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers L, Barani I, Chamberlain M et al. Meningiomas: knowledge base, treatment outcomes, and uncertainties. A RANO review. J Neurosurg. 2015;122(01):4–23. doi: 10.3171/2014.7.JNS131644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Natarajan S K, Sekhar L N, Schessel D, Morita A.Petroclival meningiomas: multimodality treatment and outcomes at long-term follow-up Neurosurgery 20076006965–979., discussion 979–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heald J B, Carroll T A, Mair R J. Simpson grade: an opportunity to reassess the need for complete resection of meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2014;156(02):383–388. doi: 10.1007/s00701-013-1923-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallagher M J, Jenkinson M D, Brodbelt A R, Mills S J, Chavredakis E. WHO grade 1 meningioma recurrence: are location and Simpson grade still relevant? Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;141:117–121. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Alkemade H, de Leau M, Dieleman E M et al. Impaired survival and long-term neurological problems in benign meningioma. Neuro-oncol. 2012;14(05):658–666. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Behling F, Fodi C, Hoffmann E et al. The role of Simpson grading in meningiomas after integration of the updated WHO classification and adjuvant radiotherapy. Neurosurg Rev. 2021;44(04):2329–2336. doi: 10.1007/s10143-020-01428-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zentner J, Meyer B, Vieweg U, Herberhold C, Schramm J. Petroclival meningiomas: is radical resection always the best option? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62(04):341–345. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.4.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldbrunner R, Minniti G, Preusser M et al. EANO guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of meningiomas. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(09):e383–e391. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleihues P, Burger P C, Scheithauer B W. The new WHO classification of brain tumours. Brain Pathol. 1993;3(03):255–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1993.tb00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Louis D N, Ohgaki H, Wiestler O D et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114(02):97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Louis D N, Perry A, Reifenberger G et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(06):803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pearson B E, Markert J M, Fisher W S et al. Hitting a moving target: evolution of a treatment paradigm for atypical meningiomas amid changing diagnostic criteria. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;24(05):E3. doi: 10.3171/FOC/2008/24/5/E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson T A, Huang L, Ramanathan D et al. Review of atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: classification, molecular biology, and management. Front Oncol. 2020;10:565582. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.565582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogers L, Gilbert M, Vogelbaum M A. Intracranial meningiomas of atypical (WHO grade II) histology. J Neurooncol. 2010;99(03):393–405. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0343-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Behling F, Hempel J M, Schittenhelm J. Brain invasion in meningioma-a prognostic potential worth exploring. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(13):3259. doi: 10.3390/cancers13133259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huntoon K, Toland A MS, Dahiya S. Meningioma: a review of clinicopathological and molecular aspects. Front Oncol. 2020;10:579599. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.579599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Rashed M, Foshay K, Abedalthagafi M. Recent advances in meningioma immunogenetics. Front Oncol. 2020;9:1472. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goutagny S, Nault J C, Mallet M, Henin D, Rossi J Z, Kalamarides M. High incidence of activating TERT promoter mutations in meningiomas undergoing malignant progression. Brain Pathol. 2014;24(02):184–189. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amrhein V, Greenland S, McShane B.Scientists rise up against statistical significance Nature 2019567(7748):305–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Day S E, Halasz L M. Radiation therapy for WHO grade I meningioma. Chin Clin Oncol. 2017;6 01:S4. doi: 10.21037/cco.2017.06.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pollock B E, Stafford S L, Utter A, Giannini C, Schreiner S A. Stereotactic radiosurgery provides equivalent tumor control to Simpson Grade 1 resection for patients with small- to medium-size meningiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55(04):1000–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04356-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Materi J, Mampre D, Ehresman J, Rincon-Torroella J, Chaichana K L. Predictors of recurrence and high growth rate of residual meningiomas after subtotal resection. J Neurosurg. 2020;134(02):410–416. doi: 10.3171/2019.10.JNS192466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ehresman J S, Garzon-Muvdi T, Rogers D et al. The Relevance of Simpson Grade Resections in Modern Neurosurgical Treatment of World Health Organization Grade I, II, and III Meningiomas. World Neurosurg. 2018;109:e588–e593. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]