Abstract

Introduction:

Abiraterone and concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) are used in the treatment of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Recently, it has been suggested that the use of abiraterone alone (without ADT) may have comparable efficacy to abiraterone with ongoing ADT. Here, we sought to assess the impact of ADT cessation in patients beginning abiraterone for castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Methods:

We identified 39 patients at our institution who received abiraterone alone (with discontinuation of ADT) between 2011 to 2022. We then procured a comparable group of 39 patients (matched by age, Gleason score, and PSA level) who received abiraterone with ongoing ADT during the same period. We assessed and compared clinical outcomes in the two groups (abiraterone-alone versus abiraterone-ADT) with respect to PSA response rates, PSA progression-free survival and overall survival. Results were adjusted using Cox proportional-hazards multivariable models.

Results:

The median PSA prior to treatment initiation was 12.7 (range: 0.2–199) ng/mL in the abiraterone-alone group and 15.5 (range: 0.6–212) ng/mL in the abiraterone-ADT group. Use of abiraterone alone adequately suppressed testosterone levels in 35/37 (94.6%) patients. Patients receiving abiraterone alone had a median PSA reduction of 80.2% vs 79.5% in patients receiving abiraterone and ADT. The median PSA progression-free survival in patients receiving abiraterone alone was 27.4 months versus 25.8 months in patients receiving abiraterone and ADT (hazard ratio 1.10; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.65–1.71; p=0.82). In addition, abiraterone alone was associated with an overall survival of 3.6 years versus 3.1 years in patients receiving abiraterone and ADT (hazard ratio 0.90; 95% CI 0.50–1.62; p=0.72). There were no differences in PFS or OS between groups after performing Cox multivariable regression analyses.

Conclusion:

Use of abiraterone alone was associated with comparable clinical outcomes to patients who received abiraterone together with ADT. Further prospective studies are warranted to evaluate the impact of abiraterone alone on treatment outcomes and cost savings.

Introduction:

Prostate cancer remains the most common noncutaneous cancer and the second leading cause of death in American men1. In patients diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer, androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is the recommended mainstay of treatment. Despite the initial positive response, virtually all patients will eventually progress to metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) despite adequate testosterone suppression, prompting additional treatment options. In patients with progressive disease, second-generation hormonal agents, such as abiraterone, are one of the recommended treatment options2.

Abiraterone is an irreversible inhibitor of CYP17 (17 alpha-hydroxylase/C17,20-lyase), an enzyme in the androgen biosynthesis pathway found in the testes, adrenal glands, and prostatic tumor cells3. Abiraterone acetate should be taken at a dose of 1000 mg/day on an empty stomach, or alternatively can be ingested at a 250 mg/day dose following a low-fat breakfast4. It should be administered together with 5 mg of prednisone twice daily to reduce the impact of mineralocorticoid-related side effects2. Importantly, in all the pivotal clinical trials leading to the FDA approval of abiraterone, the drug was prescribed together with ongoing medical castration therapies (i.e. ADT) or in patients who had previously received bilateral surgical orchiectomy.

The use of abiraterone has been associated with positive outcomes in different disease settings. In mCRPC patients previously treated with chemotherapy (COU-AA-301 trial), abiraterone acetate with prednisone was associated with a progression-free survival of 5.6 months vs 3.6 months in the placebo group. Abiraterone was also associated with an improved overall survival of 14.8 months vs 10.9 months in the placebo group in the same study5. Similarly, in patients with no previous chemotherapy treatment for mCRPC (COU-AA-302 trial), the use of abiraterone acetate with prednisone was associated with a 57% reduction of radiographic progression-free survival (hazard ratio [HR], 0.43; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.35 to 0.52; P<0.001) and a 25% reduction in the risk of death (HR, 0.75; 95% CI: 0.61 to 0.93; P=0.009)6. Given the positive outcomes seen in both of these clinical trials, the use of abiraterone acetate with prednisone in addition to ADT has become a standard of care in the treatment of mCRPC2.

Recently, a phase 2 clinical trial was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of using single-agent abiraterone as a monotherapy without ADT in mCRPC patients7. Given that this clinical trial suggested that the use of abiraterone with prednisone alone was perhaps as effective as abiraterone with ADT, we sought to determine the impact of abiraterone monotherapy on survival outcomes at our institution due to its potential to adequately suppress testosterone levels alone without ADT8.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective chart review of mCRPC patients who received abiraterone alone at our institution between October 2011 and March 2022. We conducted a consecutive search and identified 39 patients who received abiraterone therapy without ADT. We then procured 39 additional mCRPC patients who received abiraterone and concurrent leuprolide between July 2011 and April 2021. Cohorts were matched based on median PSA levels (± 5.0 ng/mL) and Gleason score at diagnosis (± one grade group), median PSA levels (± 3.0 ng/mL) at abiraterone initiation, and median age (± 3 years) at abiraterone treatment initiation. Patients previously treated with enzalutamide or any 2nd generation ADT prior to abiraterone in both groups were excluded due to abiraterone’s reduced efficacy as a second-line novel hormonal agent9. The study was approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board (STUDY00016535).

We assessed and compared three endpoints in our study: PSA response rates, PSA progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Best PSA response rate was defined as the maximum reduction in PSA level relative to baseline, expressed as a percentage; this outcome was depicted using waterfall plots. PSA progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from treatment initiation until two consecutive rises in PSA values above the nadir (in those with a PSA reduction) or above baseline (in those without any reduction). Overall survival was defined as the time of treatment initiation until death from any cause. Cox proportional-hazard multivariate analysis was then performed (for PFS and OS) after adjusting for age at abiraterone initiation, Gleason grade group, PSA at abiraterone initiation, and previous taxane chemotherapy.

Descriptive statistics were used to report means, medians, and ranges in baseline demographic characteristics. Such descriptive statistics were performed using PRISM GraphPad 9.5.0. Time-to-event endpoints (PFS and OS) were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method, and comparisons between groups were made using the log-rank test and a two-sided P value. PSA waterfall plots and survival analysis including PSA Progression-free survival (PFS) and Overall survival (OS) were also performed using PRISM GraphPad 9.5.0. Finally, Cox proportional-hazard multivariate analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0.0.0.

Results:

Demographics and baseline characteristics of patients were generally balanced, and are presented in Table 1. The abiraterone-only group had a median age of 79 (range: 46–93) years at treatment initiation, and the abiraterone-ADT group had a median age of 76 (range: 61–89) years (Mann Whitney test, p=0.24). The pretreatment PSA was 12.7 (range: 0.17–199) ng/mL in the abiraterone-only group and 15.5 (0.59 – 212) ng/mL in the abiraterone-ADT group (p=0.12). More than 60% of patients in both groups had a Gleason grade group 4 or 5 at diagnosis (p=0.69). About one-quarter of patients in both groups had previously received a taxane chemotherapy agent.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and demographics

| Characteristics | Abiraterone-alone arm | Abiraterone and Leuprolide arm |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 39 | 39 |

| PSA at Diagnosis (ng/mL) | ||

| median (min-max) | 11.0 (1.7 – 2000) | 15.9 (3.5 – 1203) |

| Grade Group (%) | ||

| 1 | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.1) |

| 2 | 4 (10.3) | 3 (7.7) |

| 3 | 5 (12.8) | 5 (12.8) |

| 4 | 8 (20.5) | 8 (20.5) |

| 5 | 16 (41.0) | 20 (51.3) |

| Unknown | 5 (12.8) | 1 (2.6) |

| Age at Abiraterone treatment initiation (Years) | ||

| median (min-max) | 79 (46 – 93) | 76 (61 – 89) |

| ECOG performance status at abiraterone initiation | ||

| 0 | 23 | 25 |

| 1 | 15 | 12 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Pre-Abiraterone treatment PSA (ng/mL) | ||

| median (min-max) | 12.7 (0.17 – 199) | 15.5 (0.59 – 212) |

| TIme between last Leuprolide treatment and Abiraterone initiation (days) | ||

| median (min-max) | 93 (11 – 185) | 84 (8–176) |

| Duration of ADT prior to Abiraterone initiation (months) | ||

| Median (min-max) | 82 (17 – 196) | 81 (16 – 187) |

| Site of disease at treatment initiation - no. (%) | ||

| Bone | 24 (61.5) | 22 (56.4) |

| Lymph node | 16 (41.0) | 19 (48.7) |

| Visceral | 1 (2.6) | 3 (7.7) |

| Previous local therapies | ||

| Radical prostatectomy (RP) | 12 (30.8) | 14 (35.9) |

| Radiation therapy | 17 (43.6) | 11 (28.2) |

| Previous systemic therapies | ||

| Leuprolide | 39 (100.0) | 39 (100.0) |

| Docetaxel | 9 (23.1) | 11 (28.2) |

| Sipuleucel-T | 10 (25.6) | 9 (23.1) |

| Nivolumab | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ketoconazole | 1 (2.6) | 1 (2.6) |

In patients receiving abiraterone alone, 28/39 (71.8%) received the full 1000 mg dose of abiraterone, 10/39 (25.6%) received a reduced dose of abiraterone (750 mg or 500 mg), and 1/39 (2.6%) received the 250mg dose with food. Two patients began at the full abiraterone dose but did not tolerate it, requiring a dose reduction. In the abiraterone-alone cohort, 38/39 patients (97.4%) had discontinued receiving ADT approximately three months prior to treatment initiation. Only 1/39 (2.6%) received ADT 11 days prior to treatment initiation. The median duration between ADT discontinuation and treatment initiation was 93 days (range: 11–185) in the abiraterone-alone cohort. In patients receiving both abiraterone and ADT, 33/39 (84.6%) received the full 1000 mg dose of abiraterone and 6/39 (15.4%) received a reduced dose (750 mg or 500 mg). Similar to the abiraterone-only group, 2 patients did not tolerate the recommended full dose. In both cohorts, all patients received the standard 5 mg of prednisone twice daily as recommended throughout treatment.

In patients receiving abiraterone alone, testosterone levels were monitored in 37/39 (94.9%) patients. 37/37 (100%) of patients had a drop of testosterone to undetectable levels (<2ng/dl) after starting abiraterone. 25/37 (67.6%) maintained a testosterone level <2 ng/dL throughout treatment, and 3/37 (8.1%) between 0 – 10ng/dL. In two (5.4%) patients, a transient elevation in testosterone levels to >50ng/dL was noted followed by a rapid reduction in testosterone back to undetectable levels (<2ng/dL) upon initiation of abiraterone.

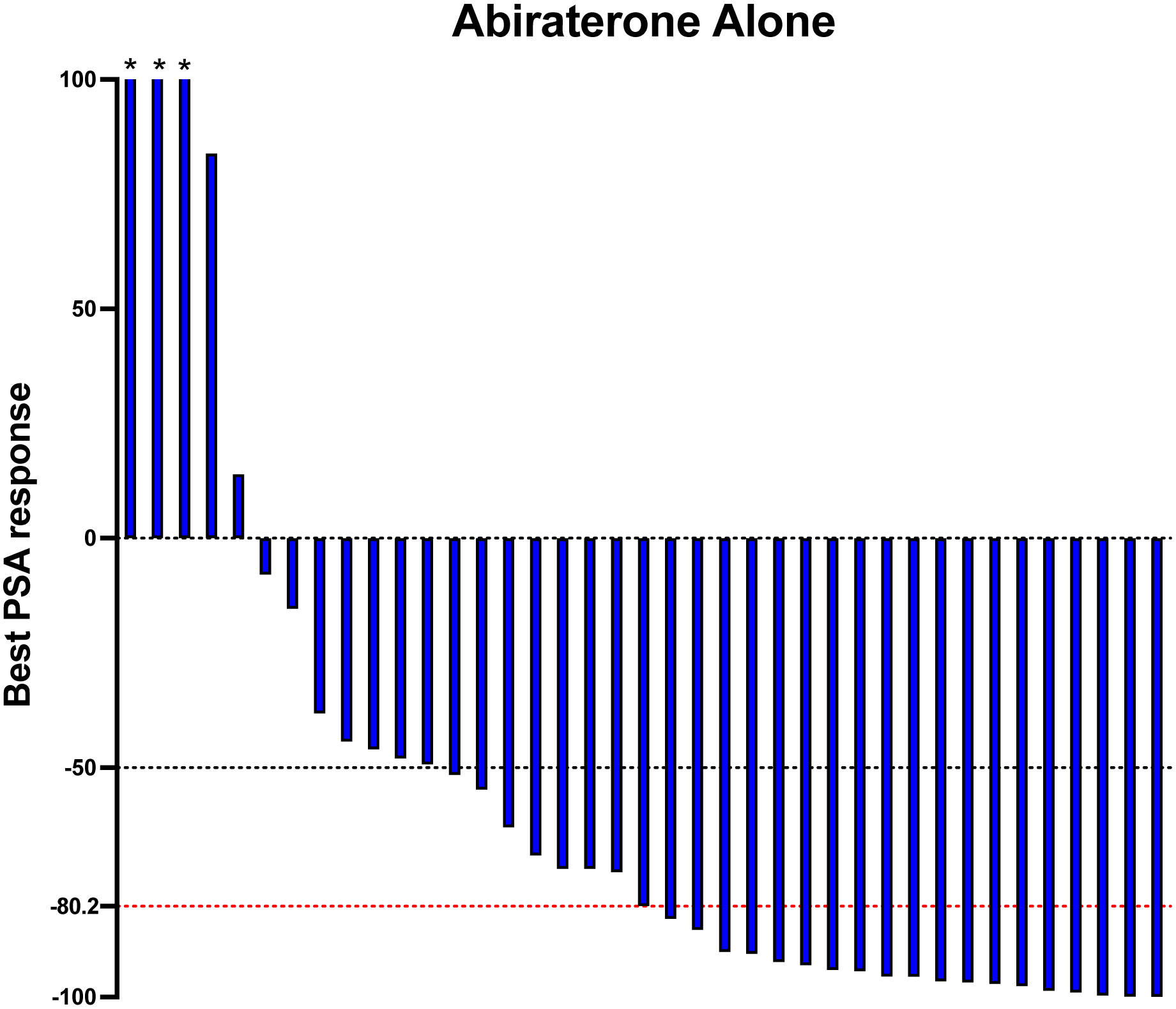

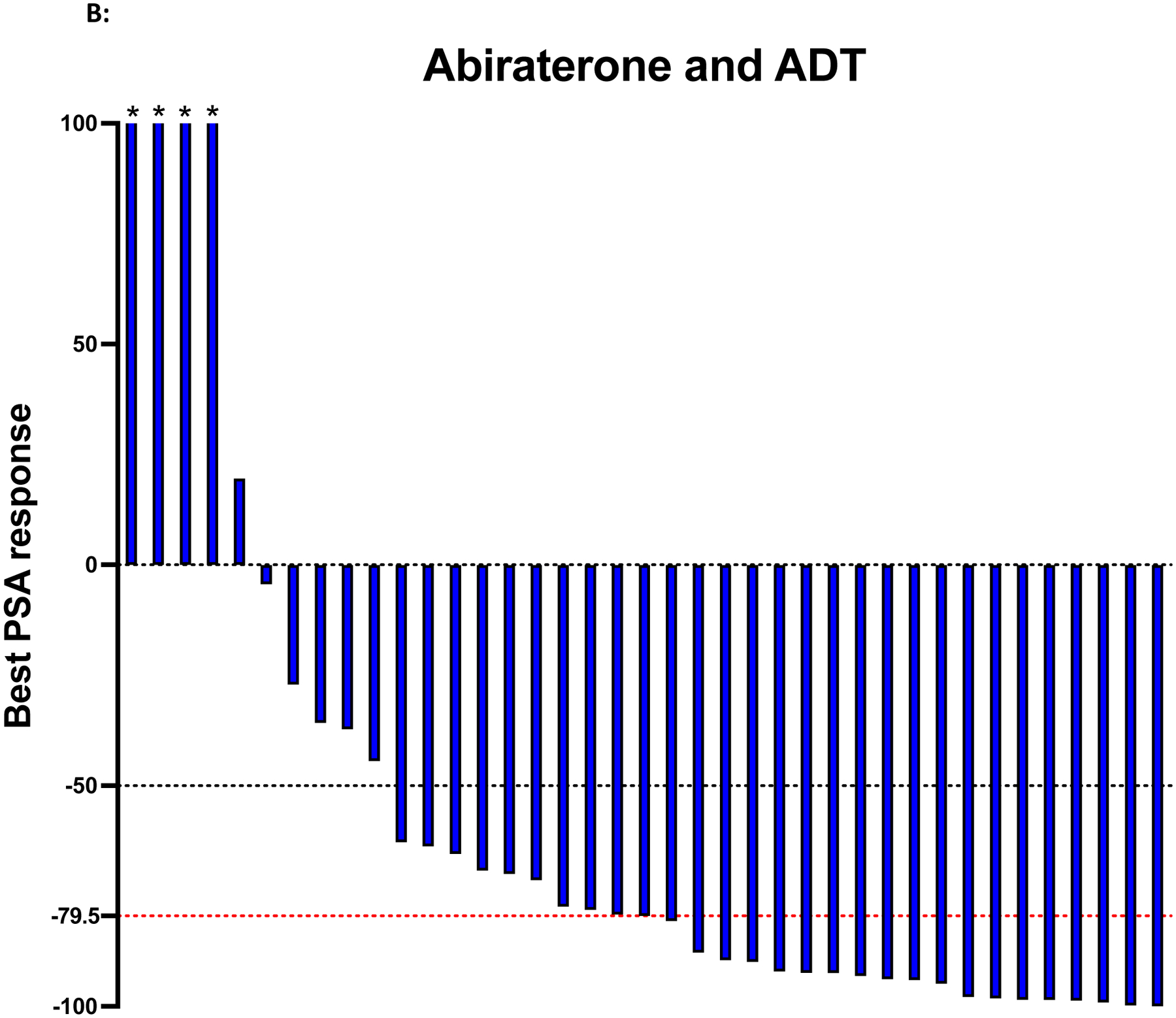

Best PSA response rate was also investigated in our study. In patients receiving abiraterone alone, 34/39 (87.2%) patients had a reduction in their PSA levels, with a median PSA reduction of 80.2%. 27/34 (79.4%) of patients achieved a PSA reduction of >50%, and 17/34 (50%) achieved a PSA reduction of >90%. (Figure 1A). In patients receiving abiraterone and ADT, 34/39 (87.2%) patients had a reduction in their PSA levels, with a median PSA reduction of 79.5%. 29/34 (85.3%) of patients achieved a PSA reduction of >50%, and 15/34 (44.1%) achieved a PSA reduction of >90%. (Figure 1B).

Figure 1: Waterfall plots of best PSA response.

Figure 1A shows the 39 patients treated with abiraterone only. Figure 1B shows the 39 patients treated with abiraterone and ADT. The black dotted line indicates a PSA response greater than or equal to 50% reduction in PSA level from baseline. The red dotted line indicates the median PSA reduction from the baseline. Asterisks indicate an increase of more than 100% in best PSA response.

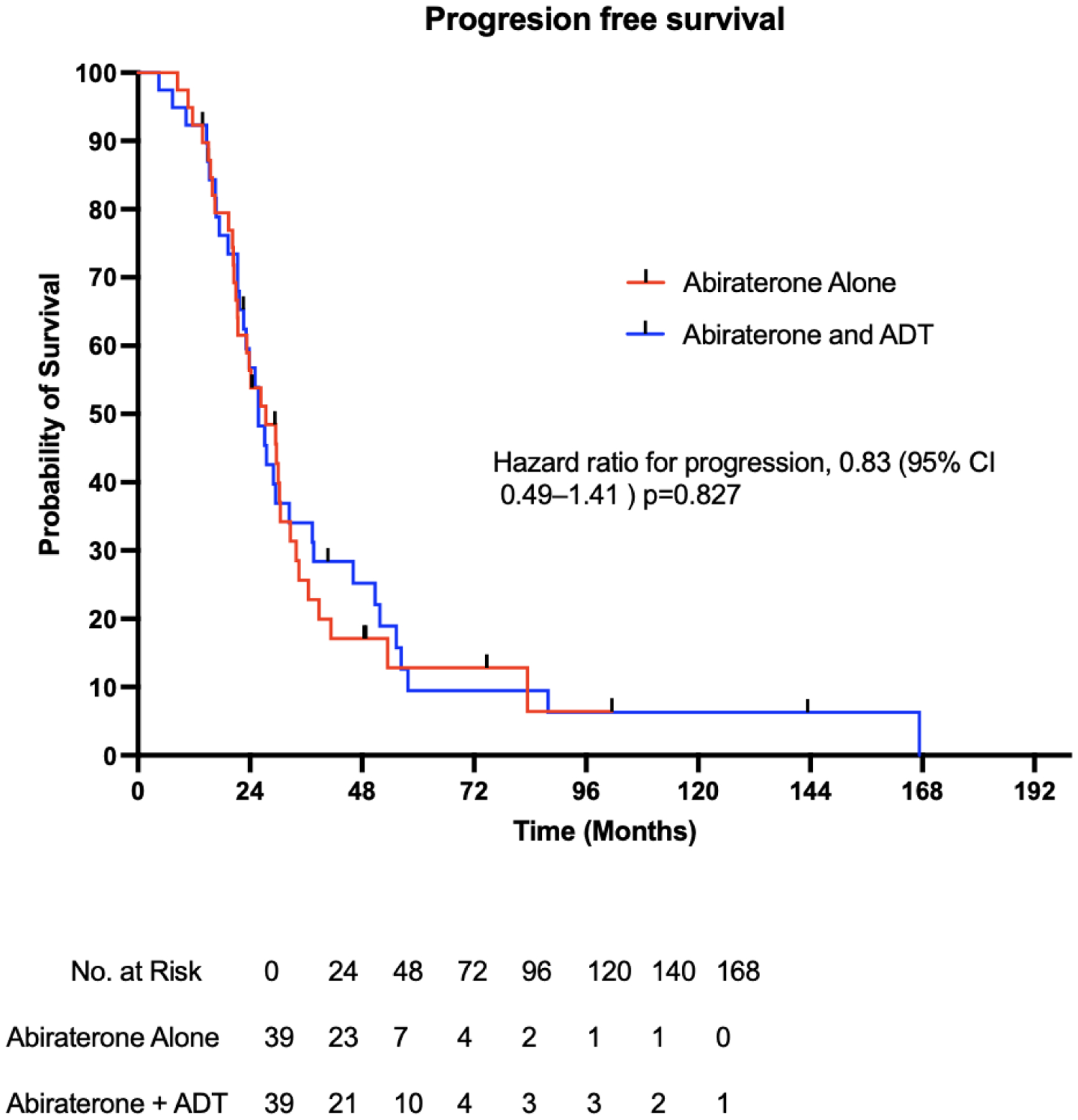

Of patients receiving abiraterone alone, the median PSA progression-free survival was 27.4 months, 95% [CI] 21.4 – 30.5 versus 25.8 months, 95% [CI] 21.3 – 32.4 in patients receiving abiraterone and ADT (hazard ratio for progression, 1.10; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.65–1.71; p=0.82). (Figure 2) (Table 2). The median duration of treatment in the abiraterone-only and the abiraterone-ADT cohorts was 26 and 25 weeks, respectively. After adjusting for age at abiraterone initiation, Gleason grade group, PSA at abiraterone initiation, and previous taxane chemotherapy, Cox proportional-hazard multivariate regression analysis showed no difference in PFS between the abiraterone-alone and abiraterone-ADT groups (adjusted hazard ratio for progression, 0.83; 95% CI 0.49–1.41; p=0.83) (Table 2).

Figure 2: Kaplan-Meier plot of PSA progression-free survival.

Figure 2 shows the PSA-based progression-free survival among the 78 patients who received abiraterone alone or abiraterone and ADT.

Table 2.

Comparison of survival outcomes between Abiraterone-alone versus Abiraterone plus ADT

| Analysis performed | Median | Hazard ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Median PSA progression-free survival for Abiraterone-alone | 27.4 months, 95% [CI] 21.4 – 30.5 | 1.10; 95% [CI] 0.65–1.71; p=0.82 (unadjusted) |

| Median PSA progression-free survival for Abiraterone plus ADT | 25.8 months, 95% [CI] 21.3 – 32.4 | |

| Cox proportional-hazard multivariate regression for PSA progression-free survival | 0.83; 95% [CI] 0.49–1.41; p=0.83 (adjusted) |

|

| Median overall survival for Abiraterone-alone | 3.6 years, 95% [CI] 3.0 – 3.9 | 0.90; 95% [CI] 0.50–1.62; p=0.72 (unadjusted) |

| Median overall survival for Abiraterone plus ADT | 3.1 years, 95% [CI] 2.7 – 4.3 | |

| Cox proportional-hazard multivariate regression for overall survival | 0.71; 95% [CI] 0.42–1.19; p=0.19 (adjusted) |

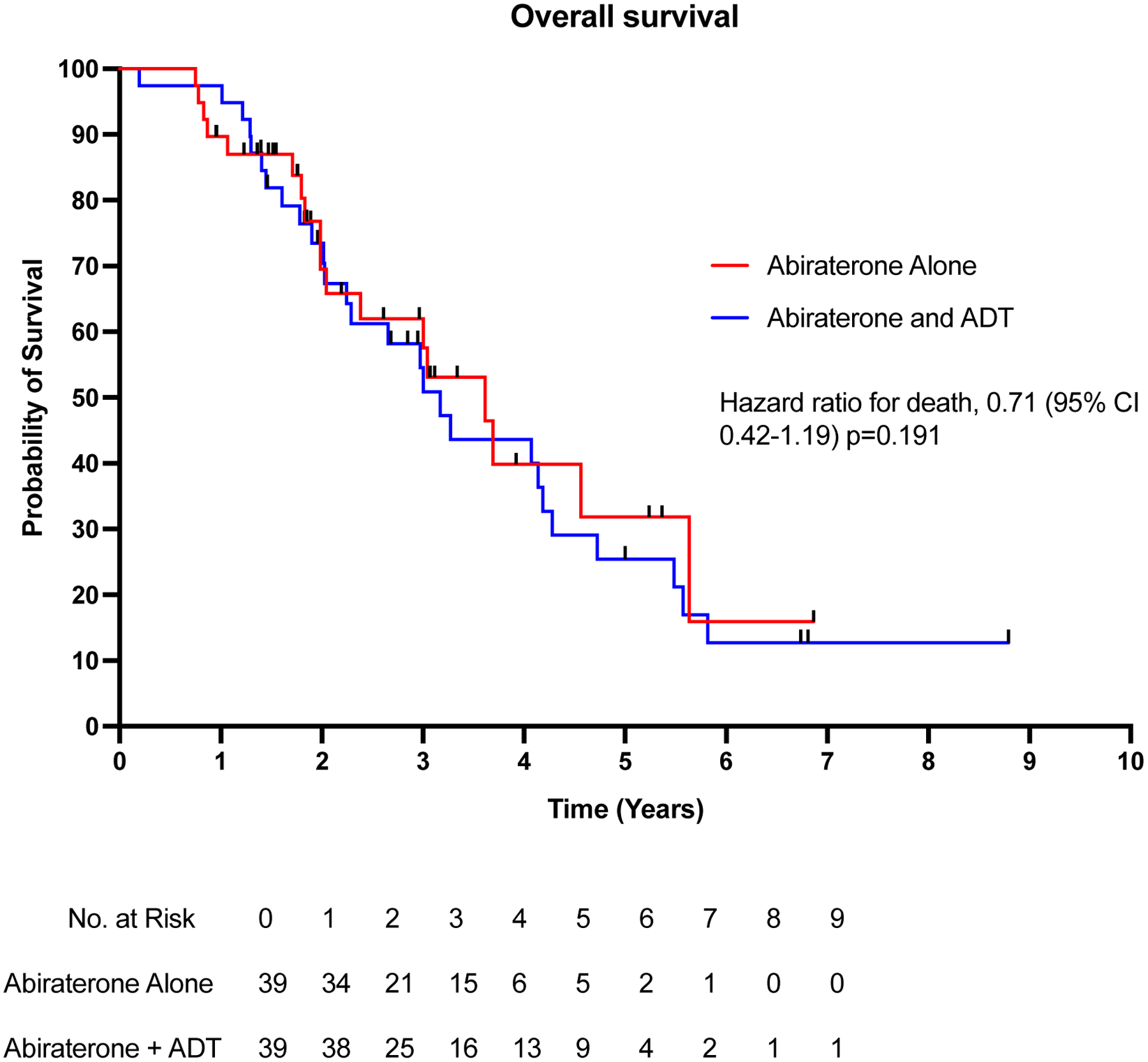

The overall survival in patients receiving abiraterone alone was 3.6 years versus 3.1 years in patients receiving abiraterone and ADT (hazard ratio for overall survival, 0.90; 95% CI 0.50–1.62; p=0.72). (Figure 3) (Table 2). The median follow-up for survival in the abiraterone-only and the abiraterone-ADT cohorts was 2.0 and 2.7 years respectively. Cox proportional-hazard multivariate analysis showed no difference in OS between the abiraterone-alone and abiraterone-ADT groups (adjusted hazard ratio for death, 0.71; 95% CI 0.42–1.19; p=0.19) (Table 2).

Figure 3: Kaplan-Meier plot of overall survival.

Figure 3 shows the overall survival among the 78 patients who received abiraterone alone or abiraterone and ADT.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the largest studies evaluating the outcomes of mCRPC patients receiving abiraterone alone (without concurrent ADT) relative to a matched control group receiving abiraterone plus ADT. Abiraterone has been used as a standard of care due to its survival benefits in both metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) and mCRPC settings5,6,10,11. A recently published randomized phase 2 clinical trial (the SPARE study) was conducted to determine the impact of using abiraterone monotherapy without ADT in 34 mCRPC patients7. The use of abiraterone alone in that trial resulted in adequate testosterone suppression <50 ng/dL, PSA response, and no difference in survival between patients receiving abiraterone alone versus abiraterone and ADT7. Similar outcomes were investigated and observed here. Patients receiving abiraterone alone had comparable PSA reductions, progression-free survival, and overall survival outcomes relative to patients receiving abiraterone and concurrent ADT. In addition, 35/37 (94.6%) patients in the abiraterone-only cohort maintained testosterone levels below castration levels throughout treatment. In 2 patients, a transient spike of testosterone was noted, possibly due to the compensatory surge in LH levels during abiraterone monotherapy, as previously reported in an early study8.

In prostate cancer, the use of ADT is associated with systemic side effects and increased financial burden in patients receiving LHRH agonist or antagonist agents. ADT is associated with erectile dysfunction, hot flashes, hyperlipidemia, osteoporosis, cognitive decline, and fatigue12. Given that the patients receiving abiraterone alone in our study and in the SPARE trial had similar tolerability to the treatment doses and survival outcomes, that may encourage larger prospective trials to investigate the use of abiraterone monotherapy to treat patients with CRPC. However, this may not be expected to improve tolerability, since serum testosterone is expected to remain suppressed using abiraterone monotherapy in most patients. On the other hand, omission of ADT during the course of abiraterone treatment would prevent patients from receiving painful injections, reduce significant cost savings, due to the lack of requirement of delivering repeated doses of LHRH agonist or antagonist agents while on abiraterone therapy, and reduce the time toxicity of visits13.

Our study had several limitations. First, all data were retrospective, from a single institution, and are subject to bias despite our best efforts to match both cohorts. We attempted to correct for these imbalances by performing multivariate analyses for PFS and OS. Second, our analyses of PSA response rates and PFS reflected a real-world practice, and may not have been very precise, because treating physicians ordered PSA tests and imaging assessments at variable intervals. Similarly, serum testosterone levels were not available in all patients, nor were testing intervals standardized. None of our patients here had received a second hormonal agent concurrently with ADT (other than bicalutamide) for hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Thus, it cannot be assumed that our findings would be applicable in the mHSPC setting where we would recommend against the omission of ADT if abiraterone is selected.

This study along with the SPARE trial7 may prompt us to consider elderly patients, opposed to receiving intramuscular/subcutaneous injections, with low tumor burden to benefit best from this regimen due to previous studies reporting slow or lack of testosterone recovery time in patients with old age receiving ADT for more than 2 years14,15. However, the impact of this study might be relatively modest and may not lead to further clinical trials due to patients receiving augmented hormonal therapy in the hormone-sensitive setting and the emergence of 3rd generation ADT and radioligand therapies16,17.

Summary

In this single-institution retrospective case-control study, abiraterone without ADT was associated with similar survival outcomes to patients receiving abiraterone with concurrent ADT. The use of abiraterone alone may have the potential to replace the use of abiraterone plus ADT in instances where serum testosterone levels are monitored continuously. Larger prospective trials are warranted to evaluate the efficacy of abiraterone or other second-generation hormonal therapies alone or in conjunction with ongoing androgen deprivation therapies.

Disclosures:

E.S.A. has served as a paid consultant/advisor to Janssen, Astellas, Sanofi, Dendreon, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Amgen, ESSA, Constellation, Blue Earth, Exact Sciences, Invitae, Curium, Pfizer, Merck, AstraZeneca, Clovis and Eli Lilly; has received research funding (to his institution) from Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Curium, Constellation, ESSA, Celgene, Merck, Bayer and Clovis; and is a co-inventor of a patented AR-V7 technology that is licensed to Qiagen.

C.J.R. Honoraria: Jansen Oncology, Bayer. Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer, Dendreon, Advanced Accelerator Applications, Myovant Sciences, Clovis Oncology (Inst), Roivant Research Funding: Clovis Oncology (Inst), Genzyme (Inst). C.J.R. is currently hired at the Prostate cancer foundation.

J.E. Honorarium: Amgen, Eli Lilly, and Genentech. Consulting role to Beigene, Eli Lilly, and Janssen

G.J. Honararium: AstraZeneca and Exelexis

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023. Jan;73(1):17–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaeffer E, Srinivas S, Antonarakis ES, Armstrong AJ, Bekelman JE, Cheng H, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Prostate Cancer, Version 1.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021. Feb 2;19(2):134–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott LJ. Abiraterone Acetate: A Review in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostrate Cancer. Drugs. 2017. Sep;77(14):1565–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szmulewitz RZ, Peer CJ, Ibraheem A, Martinez E, Kozloff MF, Carthon B, et al. Prospective International Randomized Phase II Study of Low-Dose Abiraterone With Food Versus Standard Dose Abiraterone In Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018. May 10;36(14):1389–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, Fizazi K, North S, Chu L, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011. May 26;364(21):1995–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, Molina A, Logothetis CJ, de Souza P, et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2013. Jan 10;368(2):138–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohlmann CH, Jäschke M, Jaehnig P, Krege S, Gschwend J, Rexer H, et al. LHRH sparing therapy in patients with chemotherapy-naïve, mCRPC treated with abiraterone acetate plus prednisone: results of the randomized phase II SPARE trial. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2022. Apr;25(4):778–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attard G, Belldegrun AS, de Bono JS. Selective blockade of androgenic steroid synthesis by novel lyase inhibitors as a therapeutic strategy for treating metastatic prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2005. Dec;96(9):1241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khalaf DJ, Annala M, Taavitsainen S, Finch DL, Oja C, Vergidis J, et al. Optimal sequencing of enzalutamide and abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 2, crossover trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019. Dec;20(12):1730–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, Clarke NW, Mason MD, Dearnaley DP, et al. Abiraterone for Prostate Cancer Not Previously Treated with Hormone Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017. Jul 27;377(4):338–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, Matsubara N, Rodriguez-Antolin A, Alekseev BY, et al. Abiraterone plus Prednisone in Metastatic, Castration-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017. Jul 27;377(4):352–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Desai K, McManus JM, Sharifi N. Hormonal Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Endocr Rev. 2021. May 25;42(3):354–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta A, Eisenhauer EA, Booth CM. The Time Toxicity of Cancer Treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2022. May 20;40(15):1611–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nascimento B, Miranda EP, Jenkins LC, Benfante N, Schofield EA, Mulhall JP. Testosterone Recovery Profiles After Cessation of Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. J Sex Med. 2019. Jun;16(6):872–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nam W, Choi SY, Yoo SJ, Ryu J, Lee J, Kyung YS, et al. Factors associated with testosterone recovery after androgen deprivation therapy in patients with prostate cancer. Investig Clin Urol. 2018. Jan;59(1):18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karimaa M, Riikonen R, Kettunen H, Taavitsainen P, Ramela M, Chrusciel M, et al. First-in-Class Small Molecule to Inhibit CYP11A1 and Steroid Hormone Biosynthesis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2022. Dec 2;21(12):1765–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sartor O, de Bono J, Chi KN, Fizazi K, Herrmann K, Rahbar K, et al. Lutetium-177-PSMA-617 for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021. Sep 16;385(12):1091–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]