Abstract

In this study, silver-tungsten oxide core–shell nanoparticles (Ag–WO3 NPs) were synthesized by pulsed laser ablation in liquid employing a (1.06 µm) Q-switched Nd:YAG laser, at different Ag colloidal concentration environment (different core concentration). The produced Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs were subjected to characterization using UV–visible spectrophotometry, X-ray diffraction (XRD), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), energy-dispersive spectroscopy, electrical analysis, and photoluminescence PL. The UV–visible spectra exhibited distinct absorption peaks at around 200 and 405 nm, which attributed to the occurrence of surface Plasmon resonance of Ag NPs and WO3 NPs, respectively. The absorbance values of the Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs increased as the core concentrations rose, while the band gap decreased by 2.73–2.5 eV, The (PL) results exhibited prominent peaks with a central wavelength of 456, 458, 458, 464, and 466 nm. Additionally, the PL intensity of the Ag–WO3-NP samples increased proportionally with the concentration of the core. Furthermore, the redshift seen at the peak of the PL emission band may be attributed to the quantum confinement effect. EDX analysis can verify the creation process of the Ag–WO3 core–shell nanostructure. XRD analysis confirms the presence of Ag and WO3 (NPs). The TEM images provided a good visualization of the core-spherical shell structure of the Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs. The average size of the particles ranged from 30.5 to 89 (nm). The electrical characteristics showed an increase in electrical conductivity from (5.89 × 10−4) (Ω cm)−1 to (9.91 × 10−4) (Ω cm)−1, with a drop in average activation energy values of (0.155 eV) and (0.084 eV) at a concentration of 1.6 μg/mL of silver.

Keywords: Ag NPs, WO3 NPs, Core–shell, Nanoparticles, Laser ablation, PLAL

Subject terms: Materials science, Nanoscience and technology

Introduction

Core–shell nanocomposites (NCs) have garnered significant interest in recent years due to their exceptional structural, chemical, photocatalytic, physical, and optical characteristics1–7. Core–shell NCs have a significant coupling exciton effect that exists between the core (noble metal) with surface plasmon resonance (SPR) characteristics and the excitons of the semiconductors (shell)8–10. A variety of methods have been documented for producing core–shell NPs. The wet chemistry approach involves the interaction between the core or shell material and the surrounding liquid, resulting in the formation of core–shell structures. Although this process does produce a substantial outcome, it is occasionally deemed unsustainable due to the use of hazardous substances. In contrast, physical approaches provide several benefits in comparison to wet chemical procedures. Additionally, physical approaches need little sample preparation and do not necessitate the use of environmentally toxic chemicals. The physical techniques include several approaches, such as heat flow tubes, flame assembly, spray pyrolysis techniques, and plasma procedures11. The aforementioned techniques are implemented to generate core–shell nanoparticles in a relatively brief amount of time. Laser ablation is regarded as one of the physical methods within this context. Laser ablation has been used in many methodologies for the synthesis of core–shell nanoparticles, such as laser ablation in the presence of a reactive gas and laser ablation in a liquid medium12. Yellow powdered tungsten oxide (WO3) has a density of 7.16 g/cm3, a melting point of 1473 °C, and a boiling temperature of 1700 °C. While it is insoluble in water and most acids (apart from hydrofluoric acid), it is soluble in ammonium hydroxide, where it forms tungstate13–17. Tungsten oxide (WO3) has a narrow bandgap ranging from 2.7 to 3.1 (eV), making it a material with notable reactivity within the visible light range. Tungsten trioxide (WO3) exhibits stable semiconductor properties18,19. Due to its unusual physicochemical characteristics, it has the potential to be used in a variety of technical domains, including lithium-ion batteries20,21, solar energy devices, photocatalysts16,22, smart windows, electronic information displays and electrochromic devices23–29. While WO3, ZnO, and SnO are commonly employed as gas sensor applications, Tungsten, specifically, has the capability to detect gases that are toxic and destructive, such as NO2, Acetone, and NH316,30, H2S, and hydrocarbons such as carbon monoxide, such as benzene and methane31–33. Thus, the production of WO3 is important. However, WO3 is not widely available due to price rises and export limitations imposed by manufacturing countries34. The extremely common semiconductor metal oxides used in optoelectronic devices include WO3, MoO3, SnO2, TiO2, and ZnO. Surprisingly, among all these, WO3 is used in many electronic devices due to its tunable properties of high thermal stability, visible-range optical absorption, surface morphology, and chemical composition35,36. Extensive research has been conducted on the plasmonic properties shown by silver (Ag) NPs, primarily owing to their exceptional performance relative to other surface plasmon resonance (SPR) metals throughout the visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum. Silver (Ag) nanostructures exhibit distinct, strong, and precise plasmonic phenomena within the visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum. Moreover, localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) may manifest in silver (Ag) nanostructures measuring less than 5 nm in size37–40. The core–shell nanostructures provide many benefits. By altering the material composition, core/shell size ratio, and the surrounding medium, it is possible to adjust and combine the plasmonic response of the nanoparticles. The control of nanostructured materials has garnered significant attention in recent years due to the possible properties that may be achieved and manufactured. These materials possess versatile properties that make them suitable for several application domains, including but not limited to biological, optical, magnetic electronic fields and electrical10,41–49. Numerous fields of study have developed an interest in nanoscience. Consequently, it is essential to produce nanoparticles with the ideal size distribution, morphology, and crystallinity50. Many controlled synthesis techniques for Ag-NPs, including biosynthesis, evaporation condensation, sol–gel, laser ablation, microwave processing, electron irradiation, electrochemical and photochemical have been documented51,52. Every approach has both benefits and drawbacks53–57. Nevertheless, every technique can be categorized into one of two methodologies: bottom-up or top-down. Recent studies have shown that the pulsed laser ablation in liquid medium technique (PLAL) is an effective and promising method for regulating the particle size of nanostructured materials that are manufactured58. The underlying principle of this technique is the use of high-intensity pulsed laser ablation to initiate a laser-matter interaction on the surface of the object under examination. This interaction results in the generation of a plasma plume that is fully submerged in a liquid medium59–65. This phenomenon results in the establishment of a unique thermodynamic condition characterized by elevated pressure levels. The generation of nanoscale particles is facilitated by the creation of distinctive thermodynamic conditions characterized by elevated levels of pressure and temperature64,66. The PLAL processes have the potential to generate nanostructured materials in an extensive range of shapes and dimensions. PLAL, which stands for metal or metal oxide-NCs, has recently been acknowledged as the most adaptable, promising, and straightforward technique for producing such materials. An instance of the effective use of the Nd:YAG laser is the creation of Ag nanoparticle-decorated carbon nanotubes (CNTs) to enhance the photocatalytic efficacy in the removal of naphthalene from67–79 water80 and MWCNTs/Ag NCs for catalytic degradable material for nitro compounds and dyes81. The PLAL process has many benefits, including simplicity, low cost, a decrease in by-product generation, the absence of catalyst and vacuum requirements, high-purity nanomaterial manufacturing, and precise control over particle shape and size by modifying laser settings. The metal-oxide core–shell architecture offers several benefits in terms of enhanced stability against sintering82 and leaching83, the potential to impart magnetic properties to the NCs84,85, and, notably, the ability to modify the material's electronic structure through metal-oxide interactions86. Charge transfer is a critical factor in determining the physicochemical, spectroscopic, and catalytic characteristics of the NCs materials87–89. By modifying their structure (e.g., shell thickness and core size) and composition (e.g., alloying the core or doping the shell), metal-oxide Nc can enable one to adjust their properties due to the multitude of interactions observed within them90–92. Consequently, the characteristics of metal-oxide core–shell NCs are unlike those of any other material93,94. The Ag–WO3 NPs are of particular interest for several reasons. Firstly, the Ag (NP) core can effectively generate strong localized surface plasmons (LSP) across the visible spectrum. Secondly, the LSP can be optimized by adjusting the core (Ag-NPs) diameter. Thirdly, WO3 itself is an excellent gas sensor material. Fourthly, the Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs are expected to function as a good Schottky junction sensor. Fifthly, the well-known layered structure of WO3 at nanometer thickness may enhance the sensor performance through quantum effects. Lastly, the combination of the core (Ag-NPs) and the layered WO3 shell could lead to the development of a new generation of gas sensors with enhanced quantum effects. This work aimed to produce Ag–WO3 core–shell nanoparticles utilizing a laser ablation approach in deionized water at normal room temperature. The XRD, UV–Vis spectrum, PL, EDX, FE-SEM, and TEM techniques were used to analyze the structure, morphology, optical, and electrical features of Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs generated at different core concentrations. Additionally, the room-temperature electrical properties of these NPs were also examined.

As a novel contribution, this work presents a manipulation and fine-tuning of the optical and electrical properties of Ag–WO3 core–shell nanoparticles by varying the Ag core concentration employing laser ablation in liquid technique, the study showcased the impact of core concentration on the structural, morphological, optical, and electrical characteristics of Ag–WO3 core–shell nanoparticles.

Experimental work

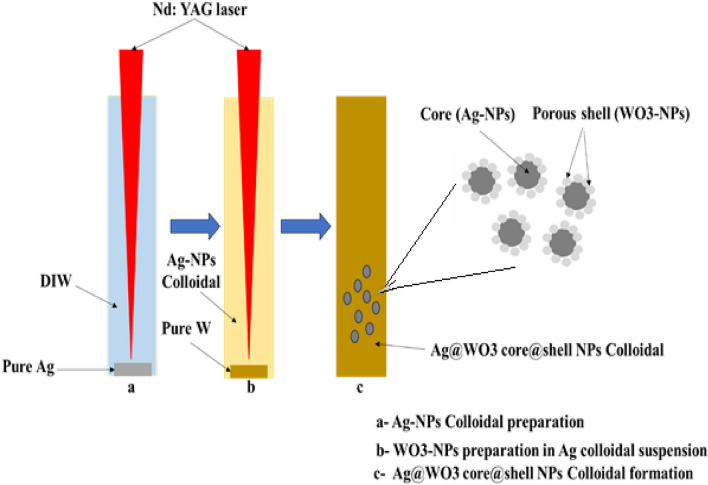

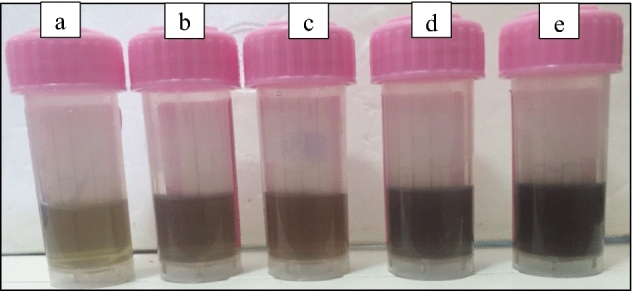

We have synthesized Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs by a two-step process of laser ablation in water. Initially, a 1064 nm Nd:YAG pulsed laser beam was used to ablate a square silver target plate with dimensions of (0.8*0.8 mm) and high purity of (99.9%) that was submerged in 3 ml of distilled water inside a glass container without the use of any chemical additives. A repetition rate of 1 Hz, 10 focal length of the lens and a pulse width of 15 ns were used. The silver target was cleaned before immersion and irradiation by dipping it in acetone and washing it in pure water. The laser ablation procedure was conducted on the Ag target using a laser fluence of 6.12 J/cm2 and number of laser pulses (200, 250, 300, 350, and 400). The experiment was conducted at different concentrations of silver. Resulting in the production of nanoparticles in the form of a suspension (0.36, 0.76, 1.2, 1.6, and 1.96 μg/mL). Step two, the silver target was subsequently substituted for a tungsten target in the solution, to produce the Ag–WO3 colloidal core–shell. Using 1064 nm, 1 Hz, 10 focal length lens with a constant laser fluence of 76.34 J/cm2 laser pulses (300), respectively. Figure 1 illustrates the schematic diagram depicting the process of forming Ag–WO3 core-Porous shell NPs by laser ablation in water (Table 1). Figure 2 depicts an image of newly formed colloidal Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs. It is evident that increasing the number of laser pulses caused an increase in core concentrations and change in the color of the solution, transitioning from light yellow to deep yellow. This change in color indicates a variation in particle size according to the number of laser pulses. The concentrations of the Ag colloidal nanoparticles were determined by estimating the weight of the Ag target before and after ablation by laser. The concentration was estimated as a function of the laser pulses number using a five digit (digital scale) precision weighing instrument that can measure weight to an accuracy of 0.00001 g. The following formulae were used. Five distinct concentrations of (Ag) nanoparticles where used95–97.

| 1 |

where: m1 and m2 denote the target's mass prior to and subsequent to ablation, respectively. The formula for calculating the concentration is as follows98–100:

| 2 |

where: V stands for the liquid’s amount.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating the process of forming Ag–WO3 core-Porous shell NPs using pulsed laser ablation in water.

Table 1.

Explained different concentrations of colloidal silver versus number of laser pulses.

| Sample | Laser pulses | Concentrations (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 200 | 0.36 |

| 2 | 250 | 0.76 |

| 3 | 300 | 1.2 |

| 4 | 350 | 1.6 |

| 5 | 400 | 1.96 |

Figure 2.

Photograph of freshly prepared colloidal Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs at different concentrations of Ag (a—0.36, b—0.76, c—1.2, d—1.6, e—1.96) μg/mL.

In order to study the structural characteristics of Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs deposited on silicon substrate, XRD measurement was used (XRD-6000, Shimadzu, X-ray diffractometer). In this work, all samples were processed using the FE-SEM (ARYA Electron Optic) equipment, which featured an energy dispersive X-ray (EDX), to accomplish the advantages indicated before. The TEM (type CM10 pw6020, Philips-Germany) was used to analyze the size and form of Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs. Using a UV–Vis double beam spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-1800), the optical absorbance of the colloidal nanoparticles solution was documented. We measured the resistance (R) values of the Ag–WO3 core–shell samples using a Kiethly electrometer and an excitation wavelength of 325 nm, as part of the Pl analysis.

Results and discussion

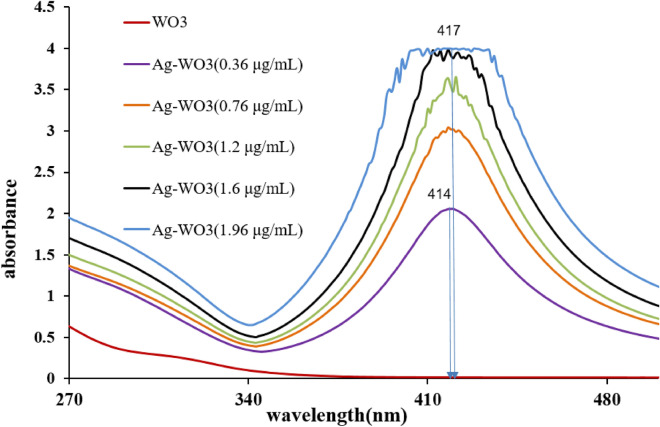

The optical properties and the energy gap of the Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs were determined by means of ultraviolet spectroscopy. The absorption spectrum of Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs samples was obtained in Fig. 3 using a fluence of 76.43 J/cm2, 400 laser pulses, and a wavelength of 1064 nm. The samples were prepared with varying concentrations of silver (0.36, 0.76, 1.2, 1.6, and 1.96 μg/mL) and a constant fluence of 6.12 J/cm2. Figure 3 shows the optical absorption spectra of the Ag–WO3 core–shell nanoparticles that were produced by employing pulse laser ablation in water. The number of laser pulses used in the synthesis process varied between 200, 250, 300, 350, and 400. A strong plasmonic absorption peak at 410 nm is easily discernible in the absorption spectra of Ag–WO3 core–shell nanoparticles. The spectrum exhibited distinct and broad absorption peaks in the visible region, located at approximately 414, 416, 415, 417, and 417 nm for the samples with concentrations of 0.36, 0.76, 1.2, 1.6, and 1.96 μg/mL, respectively. In agreement with one of the previous studies101,102. The intensities of all distinctive peaks, which were seen in the Ag–WO3 NPs samples, exhibit an increase when the amounts of silver particles are increased. The observed peaks ascribed to the presence of Ag-NPs. Furthermore, it was observed that there were minor absorption peaks at around 311, 312, 313, 314, and 315 nm, indicating the presence of WO3 nanoparticles for the samples with concentrations of 0.36, 0.76, 1.2, 1.6, and 1.96 μg/mL, respectively. After the incorporation of Ag NPs into WO3 NPs, the absorption band edge of bare WO3 is redshifted (toward a longer wavelength). The presence of both peaks provided evidence for the creation of the Ag–WO3 core shell NPs103–105. This result gives a clear indication of the effect of Ag nanoparticles due to the effect of SPR coming from Ag (core) nanoparticles. Consequently, the bandgap energy of the material decreased as a result of the redshifted of absorption band edges produced by the incorporations of Ag NPs. The band gaps of the samples at different concentrations of silver (0.36, 0.76, 1.2, 1.6, and 1.96 μg/mL) are presented in Fig. 4. The optical absorption band gap follows a power law when incident photon energy is greater than the band gap and above the exponential106–109:

| 3 |

where Eg is the optical bandgap, α is the absorption coefficient, n is an exponent, β is the edge with parameter and hʋ is the incident photon energy.

Figure 3.

Absorption spectrum of Ag–WO3 nanoparticles with various Ag nanoparticle concentrations.

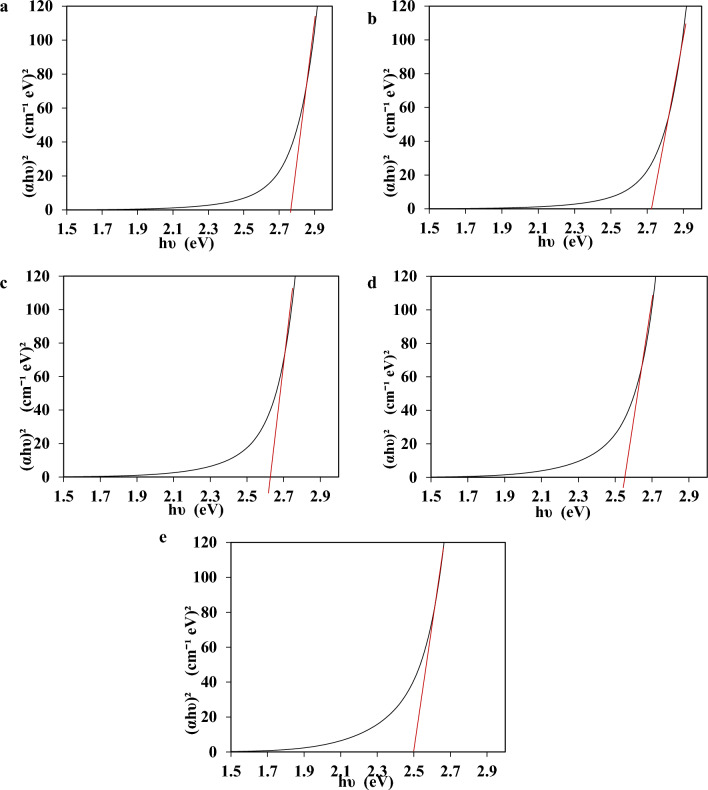

Figure 4.

The absorption and energy gap spectra of Ag–WO3-NPs at different concentrations of Ag (a—0.36, b—0.76, c—1.2, d—1.6, e—1.96) μg/mL.

It can be observed from Fig. 4 that the optical band gap energy decreases to 2.75, 2.73, 2.62, 2.55, and 2.5 eV as the concentration of Ag increases. These values are very close to those stated in a previous study110, the band gap tailoring in core–shell NPs was attributed to its shape and the quantum confinement effect111,112. The interfaces of Ag–WO3 NPs have a significant impact on the processes of charge transfer and separation113,114. This is attributed to the presence of Ag NPs, which function as localized surface plasmons (LSP). This process credits the combination of electromagnetic waves to the oscillations of electrons115. This procedure enables the reduction of the band gap in the core cell structure. As a result, the adjusted band gap allows for increased interaction between visible light and the core–shell compared to the regulated WO3. The core–shell has promising optical and electrical properties because to its ability to fine-tune the band gap features116,117. Consequently, the bandgap energy of the material decreased as a result of the redshifted of absorption band edges produced by the incorporations of Ag NPs.

The flat peak in surface plasmon resonance typically refers to the collective oscillation of electrons at the interface between a metal and a dielectric material when excited by incident light. The resonance condition occurs when the momentum of incident photons matches the momentum of the surface plasmons.

The SPR response may not exhibit a sharp peak, making it challenging to identify the resonance position. This could be due to various factors, such as broadening of the SPR peak due to particle size distribution, polydispersity, or other experimental conditions.

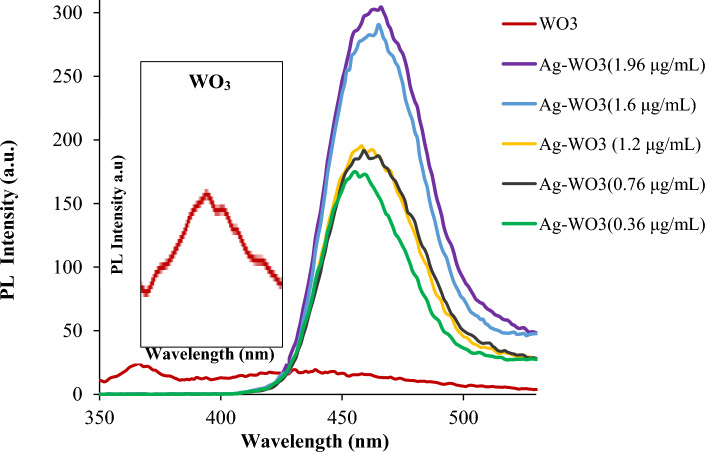

Figure 5 displays the photoluminescence (PL) spectrum of core–shell NPs consisting of silver (Ag) and tungsten oxide (WO3). The photoluminescence (PL) studies revealed increased intensities in all the Ag–WO3 samples created using varying amounts of silver (0.36, 0.76, 1.2, 1.6, and 1.96 μg/mL). The spectrum shows excitation bands located at 456, 458, 458, 464, and 466 nm, which correspond to energy gaps of about 2.71, 2.7, 2.7, 2.67, and 2.66 eV, respectively. The energy gap value approximated using PL data is marginally greater in magnitude compared to what was ascertained using UV–vis data118. Further, it differs from the energy gap of pure WO3. The PL intensities of the Ag–WO3 NPs peaks exhibited a significant increase compared to the PL peak of WO3. Additionally, these peaks show a minor shift, which may be ascribed to the enhanced photoluminescence seen in the NCs structure. This improvement is due to the incorporation of Ag-NPs. These results are consistent with UV–visible results. Ag–WO3 CS-NPs' emission energy and PL emission wavelength are displayed in Table 2 as a function of Ag concentrations.

Figure 5.

PL spectrum of Ag–WO3 nanoparticles with various Ag nanoparticle concentrations.

Table 2.

The Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs' emission energy and PL emission wavelength as a function of Ag concentrations.

| Ag concentrations (μg/mL) | UV–vis energy gap (eV) | PL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emission peak wavelength (nm) | Band gap energy (eV) | ||

| 0.36 | 2.73 | 456 | 2.71 |

| 0.76 | 2.72 | 458 | 2.7 |

| 1.2 | 2.6 | 458 | 2.7 |

| 1.6 | 2.55 | 465 | 2.67 |

| 1.96 | 2.5 | 466 | 2.66 |

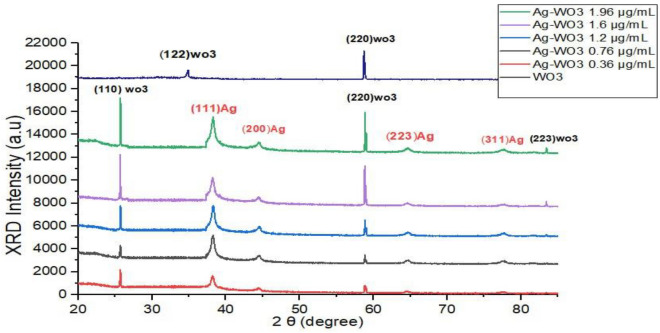

Figure 6 displays the diffraction peaks corresponding to the core–shell samples. These peaks were generated using a fluence of 76.34 J/cm2 and 400 laser pulses. The figure also displays a wavelength of 1064 nm with different concentrations of silver (0.36, 0.76, 1.2, 1.6, and 1.96 μg/mL). This figure further displays the prominent peaks that can be ascribed to hexagonal WO3, as indicated by the JCPDS card number 00-33-1387 and PDF number #75-2187. The peaks are located at 2θ values of 25.5° and 58.84°, corresponding to the orientations (110) and (220), respectively. On the other hand, the peak at 2θ = 83.4o with orientations (223), indexed to JCPDS card no. 89-1287, is related to the tetragonal WO3 phase. The presence of Ag-NPs was verified by the peaks at 2θ = 38.2o, 44.3o, 64.5o, and 77.86o with orientations (111), (200), (223), and (311). This can be attributed to cubic Ag nanoparticles, according to pdf number 870720. Due to the relatively high diameter of the core, significant diffraction peaks are generated. XRD identification of the core–shell configuration119–121 showed that these results are in line with the study122. When exposed to X-ray radiation, the greater concentrations of aggregated silver nanoparticles resulted in a greater degree of reflection123,124. For the WO3 sample, two peaks appeared at 2θ: 28.92° and 58.84°. While 28.92° corresponds to the (122) plane according to (JCPDS # 201323) triclinic WO3 phase structure, 58.84° corresponds to the (220) plane hexagonal WO3 phase structure. In addition, the XRD patterns of Ag–WO3 core/shell NPs exhibit a marginally greater intensity than those of shell NPs (Fig. 6). This may be the result of incorporation Ag core NPs causing an increase in particle size and crystallinity. Table 3 illustrates the grain size, dislocation densities, Miller indices, and micro strains of Ag–WO3 nanoparticles. The Scherrer formula is used to calculate the size of crystallites125–127:

| 4 |

where λ is the X-ray wavelength, β is the full width at the half maximum, k is the constant 0.89 < k < 1 change with Miller indices and crystallite shape, but is frequently close to 0.94, and θ is the diffraction angle128–130. The dislocation density was calculated using the formula (3) and the Microstrains were determined using Eq. (5). The table demonstrates a small augmentation in crystalline size when the concentration of silver particles is increased. Conversely, the dislocation density and Microstrains exhibited a reduction due to the aforementioned factor. The dislocation density in lines/m2 can be determined by employing the equation131–133:

| 5 |

Figure 6.

XRD patterns of Ag-–O3 nanoparticles using various Ag concentrations.

Table 3.

XRD parameters of core–shell Ag@WO3 nanoparticles prepared with various Ag nanoparticle concentrations.

| Ag concentration μg/mL |

2θ | FWHM | Miller indices | Crystalline size (nm) | Dislocation density (δ) | Microstrains |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.36 |

25.5° 58.84° |

0.146 0.114 |

110 220 |

55.45 63.43 |

0.078227463 0.038693379 |

0.062103798 0.043311681 |

| 0.76 |

25.5° 58.84° |

0.13 0.093 |

110 220 |

56.86 72.82 |

0.729303684 0.033897991 |

0.063672181 0.04971665 |

| 1.2 |

25.5° 58.84° 83.4° |

0.129 0.089 0.235 |

110 220 223 |

62.76 81.25 26.384 |

0.069118786 0.030207989 0.063461585 |

0.054872534 0.033813505 0.076545193 |

| 1.6 |

25.5° 58.84° 83.4° |

0.121 0.083 0.224 |

110 220 223 |

66.91 85.19 27.67 |

0.064832349 0.02783208 0.06049102 |

0.052469586 0.031154016 0.072962227 |

| 1.96 |

25.5° 58.84° 83.4° |

0.11 0.081 0.211 |

110 220 223 |

73.60 89.28 29.38 |

0.046790533 0.030774089 0.068727812 |

0.050938499 0.027492664 0.056980402 |

(d) Lattice strain or Microstrains (η).

The lattice strain is caused by lattice imperfections such dislocations, vacancies, interstitials, and substitutional. These defects cause the atoms to be displaced from their original places in the crystal structure, as a result, the lattice plane d-spacing may be varied. Microstrains will occur during the production of the thin film. This strain may be estimated using the equation below134–137.

| 6 |

The film deposition circumstances will have an impact on structural factors such grain size, crystallinity, and crystal structure.

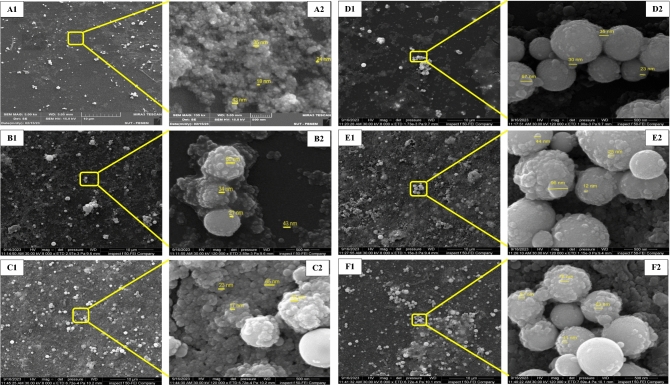

Figure 7 shows the FESEM images of Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs samples as function of Ag-NPs concentrations. The Ag-NPs concentrations in the samples varied from 0.36 to 1.96 μg/mL. As seen in Fig. 7. The Ag–WO3 core–shell structure displays a noticeable augmentation in particle size as the concentration of silver increases. Furthermore, the particles have a well-defined spherical morphology that aligns precisely with the findings of the study138–140. The shape, size and agglomerated particles of nanoparticles are determined by the concentrations of Ag-NPs, as seen in Fig. 7. Specifically, the size of WO3 outer shell nanoparticles rises proportionally with higher concentrations of Ag-NPs. Additionally, the size of the Ag core also increases in tandem with the Ag-NPs concentrations. This aligns with the findings reported in a prior investigation141. The (SEM) images reveal the presence of core/porous-shell structures in the microspheres. The pores inside the shell are densely and uniformly distributed, as seen from the distinct color difference. The shell exhibited a high degree of porosity and was characterized by its minimal thickness. The pictures given below depict various morphological characteristics of both the core and the shell layer. The outer layer, WO3, has a higher degree of surface roughness in comparison to the inner layer, Ag.

Figure 7.

FESEM images of (a) WO3-NPs and Ag–WO3-NPs at various Ag concentrations (b—0.36, c—0.76, d—1.2, d—1.6 and e—1.96) μg/mL.

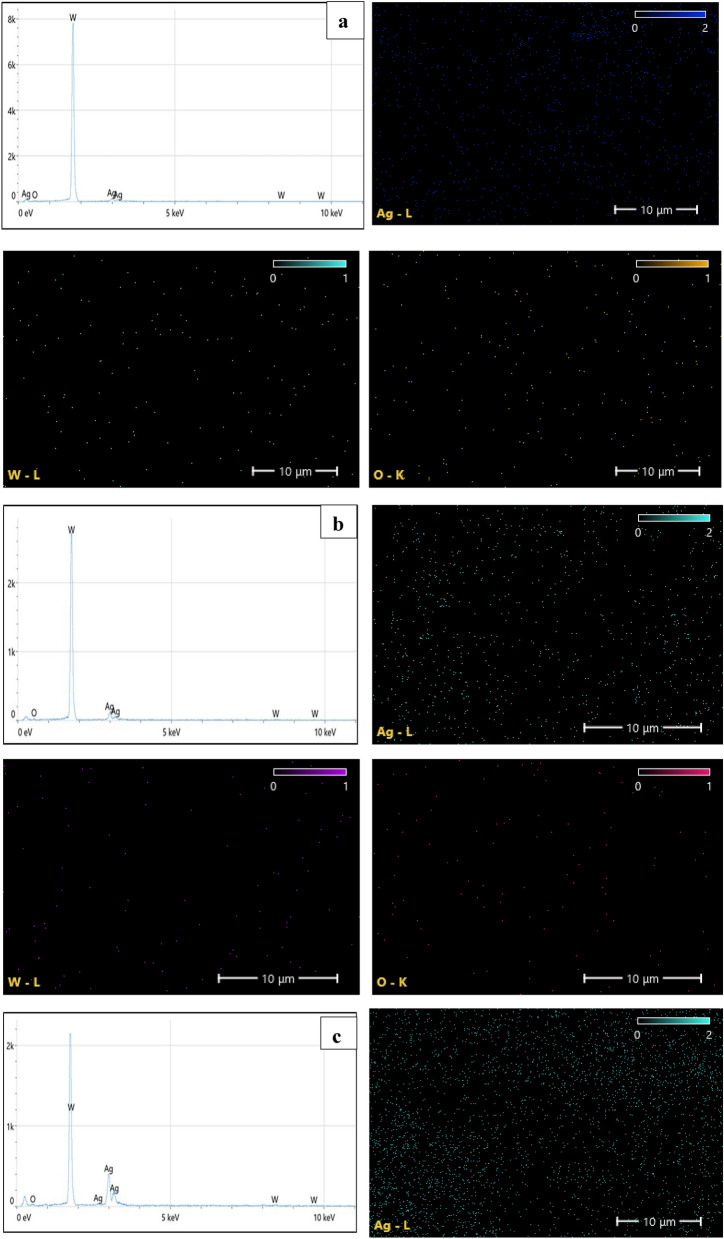

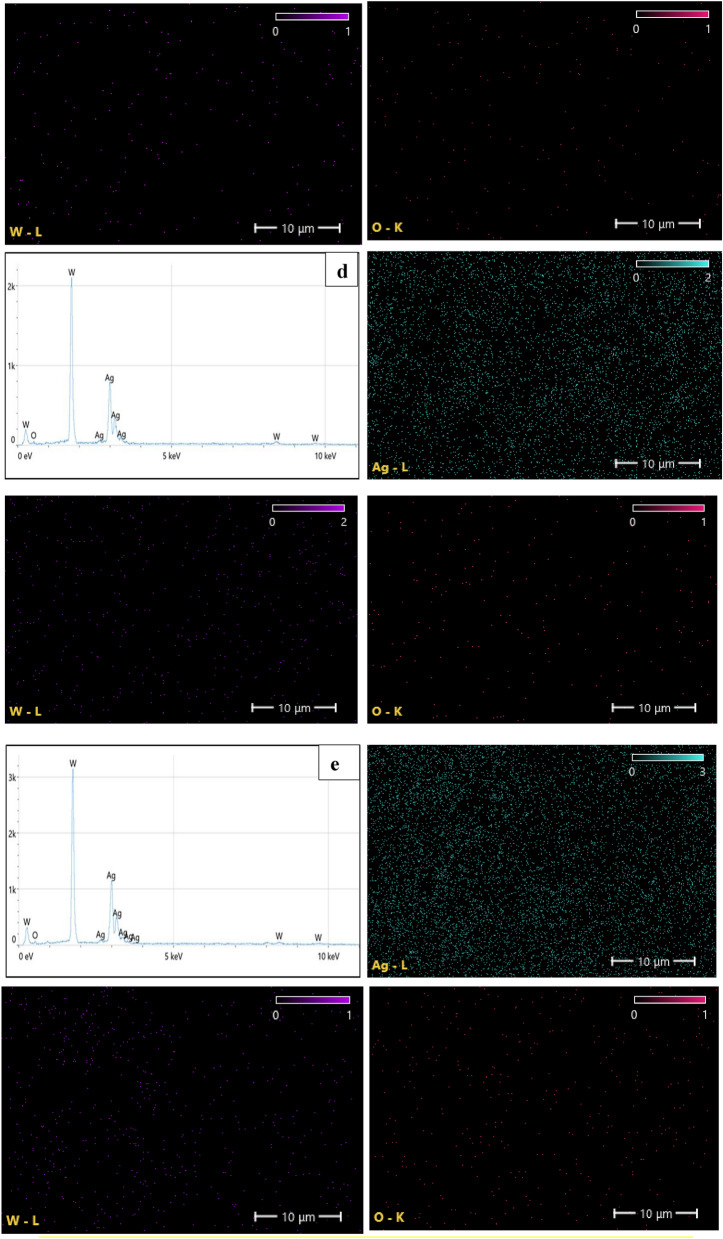

The EDX results for Ag–WO3 core–shell nanoparticles are depicted in Fig. 8. EDX analysis has the potential to provide insights into the formation process of the Ag–WO3 core–shell nanostructure. It can give an indication for the formation of the Ag–WO3 core–shell nanostructure, according to Muhammad A. Imam and Nitin Chopra142,143. The presence of tungsten (W), oxygen (O), and silver (Ag) in the core shell system was confirmed by this figure. Supporting the EDX results of Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs, Fig. 8a,e illustrate the mapping outcomes of Ag, WO3, and O, respectively. Ag NPs showed high intensity in EDX due to the increase laser pulses and increasing Ag concentration. Table 4 illustrates the weight percentages of the elements contained in the samples, as well as the stoichiometries of WO3. The stoichiometric ratio and weight percentage appear to exhibit an upward trend when the concentration of silver nanoparticles increases.

Figure 8.

EDX spectra and elemental mapping images for Ag–WO3 nanoparticles for various Ag concentrations (a—0.36, b—0.76, c—1.2, d—1.6, and e—1.96) μg/mL.

Table 4.

Ag–WO3-NPs stoichiometry and weight percent of elements.

| Ag concentration μg/mL |

W % | Ag % | O % | WO3 Stoichiometry (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.36 | 31.2 | 27.0 | 41.8 | 19 |

| 0.76 | 32.2 | 29.4 | 38.4 | 22 |

| 1.2 | 32.6 | 33.0 | 34.4 | 24 |

| 1.6 | 35.0 | 42.2 | 22.8 | 41 |

| 1.96 | 35.2 | 44.6 | 20.2 | 45 |

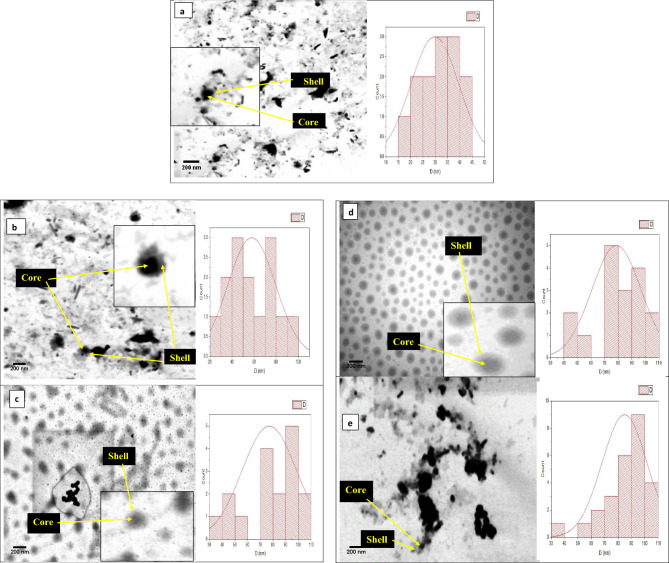

Figure 9a–e depicts transmission electron microscopy (TEM) pictures of Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs samples, illustrating the relationship between the concentration of silver and the observed characteristics. The form and size of NPs are influenced by the concentration of silver, as depicted in the figure. The size of the silver core exhibits a positive correlation with the concentration of silver. In this study, the transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images demonstrate the production of Ag nanoparticles of varying sizes, as well as the presence of some monodisperse Ag particles that are enveloped by a WO3 shell. Additionally, the presence of both aggregated and agglomerated silver particles was noted as increasing the concentration of silver. This matches what was stated in the results of the FE-SEM. Besides, these pictures provide confirmation that the central Ag particles possess spherical morphologies. Table 5 presents data on the average particle size of Ag–WO3 core–shell and Ag core. The results indicate that when the concentration of silver nanoparticles was raised from 0.36 to 1.96 μg/mL, the particle size of the Ag–WO3 core–shell climbed from 30.5 to 89 nm, while the size of the Ag core increased from 28 to 81 nm. Thus, the manipulation of core size is a viable approach for modulating the overall dimensions of metal-oxide nanoparticles, hence exerting a significant influence on the characteristics of the resulting nanocomposites. This is consistent with what was reported in these studies144–146.

Figure 9.

TEM images of Ag–WO3-NPs with different Ag concentrations (a—0.36, b—0.76, c—1.2, d—1.6, and e—1.96) μg/mL.

Table 5.

Presents the average particle size of Ag–WO3-NPs.

| Ag concentration (μg/mL) | Ag core size (nm) | Average particle size of Ag–WO3 NPs (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.36 | 28 | 31 |

| 0.76 | 42 | 45 |

| 1.2 | 60 | 65 |

| 1.6 | 69 | 74 |

| 1.96 | 81 | 89 |

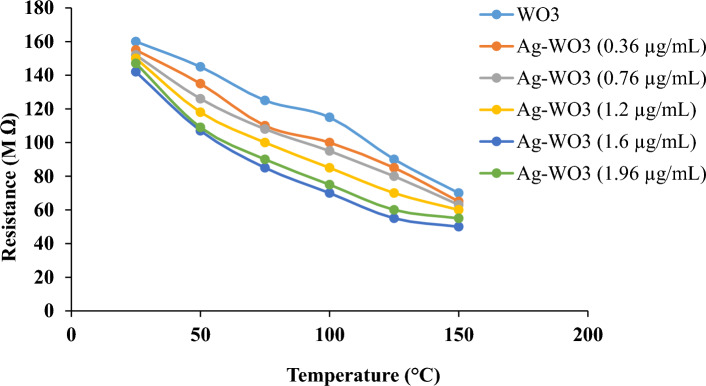

Electrical measurements of WO3 NPs and Ag–WO3 core–shell samples at various Ag concentrations (0.36, 0.76, 1.2, 1.6, and 1.96 μg/mL) were studied in order to achieve the optimum sample conductivity (lowest resistance). The relation of resistance (R) as a function of temperature (T) was determined, as shown in Fig. 10. The reported resistance values of the Ag–WO3 core–shell were high at low temperatures and gradually decreased as the temperature of each sample increased. This is the typical situation for semiconducting materials, as they possess a temperature coefficient that is negative (wherein the resistance decreases as the temperature increases). At thermal equilibrium conditions (room temperature), the initial reading was obtained for each sample to evaluate the resistivity of Ag–WO3 manufactured at different Ag concentrations. As shown in this figure, the sample prepared with a concentration of 1.6 g/mL of silver yielded the lowest resistance of approximately 47.1 MΩ at 150 °C. The electrical resistance of the created samples was reduced on a regular basis as compared to the WO3 sample. Because (Ag) nanostructures are metals characterized by elevated levels of free carriers, the conductivity (σ) was raised.

Figure 10.

Temperature-dependent resistance of WO3 NPs and Ag–WO3 core–shell synthesized with various Ag concentrations.

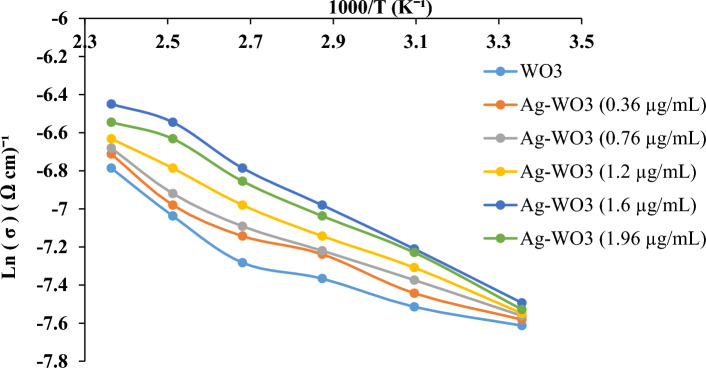

Figure 11 shows the logarithmic conductivities (lnσ) of the carrier’s curve as a function of reciprocal temperature (1000/T) for WO3 and Ag–WO3-produced samples with various Ag concentrations (0.36, 0.76, 1.2, 1.6, and 1.96 μg/mL). The corresponding electrical conductivities (σ) of the samples were determined using the equation147–149:

| 7 |

Figure 11.

Arrhenius plot curve of ln (σ) versus (1000/T) of WO3NPs and Ag–WO3 core–shell synthesized with various Ag concentrations.

The equation shows the resistivity (ρ) in (Ω cm). Based on the figure, the electrical conductivity of the Ag–WO3 core–shell increases as the concentration of silver increases. This rise in conductivity was due to an increase in carrier concentration and mobility150, whereas the electrical conductivity (σ) values for the sample prepared with 1.96 μg/mL of silver were decreased. This result is due to the aggregation of (Ag) nanostructures in extremely high concentrations, which reduced the carrier mobility. The drop in mobility was directly proportional to the decrease in electrical conductivities151–153. This is consistent with what was stated in the previously work154–156. Table 6 show the activation energy of Ag–WO3 with different Ag concentrations for current work and previous work156,157.

Table 6.

The activation energy of Ag–WO3 with different Ag concentrations for current work and previous work.

| Current work | Previous work126 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag concentration (μg/mL) | Average (σdc) (Ω cm)−1 | Activation energy (eV) | Time (s) | Ag concentration (μg/mL) | Average (σdc) (Ω cm)−1 |

| (0 Ag-(WO3) | 5.89 × 10−4 | 0.155 | 5 | 6.328 × 10−8 | 0.222 |

| 0.36 | 7.91 × 10−4 | 0.117 | 15 | 8.5624 × 10−8 | 0.221 |

| 0.76 | 8.25 × 10−4 | 0.111 | 25 | 1.3619 × 10−7 | 0.188 |

| 1.2 | 8.93 × 10−4 | 0.094 | 35 | 3.4491 × 10−7 | 0.220 |

| 1.6 | 10.6 × 10−4 | 0.091 | 45 | 1.8557 × 10−7 | 0.192 |

| 1.96 | 9.91 × 10−4 | 0.084 | |||

The Arrhenius relation was used to calculate the activation energy158–160:

| 8 |

where the conductivities of carriers are denoted by the symbol σ, σ° represents the temperature of the independent portion conductivity, Ea denotes the necessary amount of energy for activation, then tn, constant of Boltzman (K), and the temperature, denoted by the letter T, is expressed as a value in Kelvin (k) unit. The activation energy values as a function of Ag concentration in the Ag–WO3 samples are listed in Table 6.

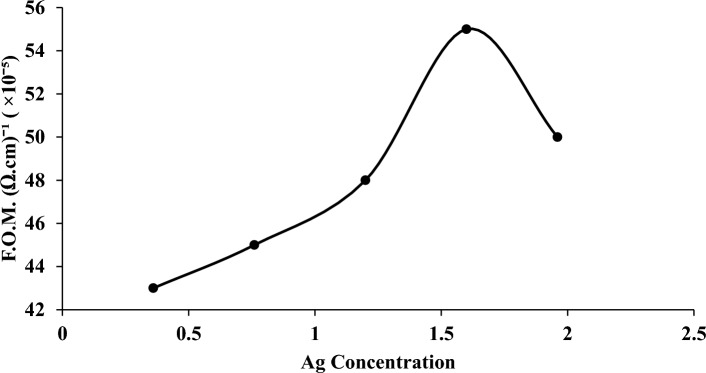

The figure of merit (F.O.M.) of Ag–WO3 core–shell samples created with various silver concentrations is displayed in Fig. 12. They were computed using Eq. (9) which was provided by Iles and Soclof161–163:

| 9 |

Figure 12.

F.O.M. of Ag–WO3 core–shell synthesized with various Ag concentrations.

The absorption coefficient is represented by the symbol (α) and is the conductivity of electricity. The requirement for calculating the F.O.M. was to realize the optimal electrical conductivity (σ) as a function of the absorption coefficient (α) of Ag–WO3 that was made by varying the amount of Ag (0.36, 0.76, 1.2, 1.6, and 1.96 μg/mL). The concentration of 1.6 μg/mL of silver used in the preparation of the Ag–WO3 core shell is considered a merit figure, as the incorporation of silver (Ag) was intended to improve the semiconductor material's properties.

Conclusion

We are successively synthesizing a Novel Ag–WO3 core–shell nanostructure using a two-step laser ablation process in deionized water. The impact of varying core concentrations (Ag-NPs) on the structural, electrical, morphological, and optical characteristics of Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs have been investigated. XRD analysis has confirmed the growth of a hexagonal polycrystalline WO3 phase and the creation of cubic Ag-NPs. The presence of Ag–WO3 core–shell NPs was verified using the XRD profile, which exhibited prominent diffraction planes. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis demonstrated that the size of the Ag core and the thickness of the WO3 shell were dependent on the concentration of the core (Ag). Additionally, the study showed that the Ag–WO3 nanoparticles exhibited a spherical morphology. The photoluminescence (PL) data exhibited a wide peak with a central wavelength of 456 nm. Following the creation of a hybrid Ag–WO3 core–shell structure, the PL intensity of WO3 was quenched. The wavelength of the absorption peak was abundantly evident at (414–417) nm. As a result of the increased ablation, the absorbance rose as the Ag-NPs concentration increased. A substantial decrease in the band gap was observed, with a transition from 2.73 to 2.5 electron volts (eV). The DC conductivity exhibited a distinctive semiconductor-like behavior, showing an increase with elevated temperatures. The figure of merit (F.O.M.) with the best performance was identified by an electrical conductivity observed at a concentration of 1.6 μg/mL of silver. The electrical conductivity of Ag–WO3 has seen a notable increase, with the most advantageous characteristics due to the incorporation of Ag-NPs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the University of Technology-Iraq for the logistic support this work. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA for support this research work through the project number “NBU-FFR-2024-1299-01”. The authors gratefully thank the Prince Faisal bin Khalid bin Sultan Research Chair in Renewable Energy Studies and Applications (PFCRE) at Northern Border University for their support and assistance. The authors would like to thank Al-Farahidi University, Baghdad, Iraq for the logistic support this work.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, E.T., J.A., M.S., A.S., R.I., M.A., and M.H.; methodology, E.T., J.A., M.S., A.S., R.I., M.A., and M.H.; validation, E.T., J.A., M.S., A.S., R.I., M.A., and M.H.; formal analysis, E.T., J.A., M.S., A.S., R.I., M.A., and M.H.; investigation, E.T., J.A., M.S., A.S., R.I., M.A., and M.H.; resources, E.T., J.A., M.S., A.S., R.I., M.A., and M.H.; data curation, E.T., J.A., M.S., A.S., R.I., M.A., and M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S., and M.H.; writing—review and editing, E.T., J.A., A.S., R.I., and M.A.,; visualization, E.T., J.A., M.S., A.S., R.I., M.A., and M.H.; supervision, E.T., and J.A.; project administration, E.T., J.A., M.A.; funding acquisition, providing own funds, Each author has reviewed the published version of the manuscript and given their approval.

Data availability

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Evan T. Salim, Maryam S. Muhsin, Makram A. Fakhri.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Evan T. Salim, Email: evan_tarq@yahoo.com, Email: evan.t.salim@uotechnology.edu.iq

Makram A. Fakhri, Email: mokaram_76@yahoo.com, Email: makram.a.fakhri@uotechnology.edu.iq

Ahmad S. Azzahrani, Email: ahmad.azzahrani@nbu.edu.sa

References

- 1.Chaudhuri R, Paria S. Core/shell nanoparticles: Classes, properties, synthesis mechanisms, characterization, and applications. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:2373–2433. doi: 10.1021/cr100449n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y, Wu H, Li Z, et al. The study of surface plasmon in Au/Ag core/shell compound nanoparticles. Plasmonics. 2012;7:509. doi: 10.1007/s11468-012-9336-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zamiri R, Zakaria A, Jorfi R, et al. Laser assisted fabrication of ZnO/Ag and ZnO/Au core/shell nanocomposites. Appl. Phys. A. 2013;111:487. doi: 10.1007/s00339-012-7517-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oh J, Kim H. Synthesis of core–shell nanoparticles with a Pt nanoparticle core and a silica shell. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2013;13:130. doi: 10.1016/j.cap.2012.06.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu H, Qu S, Lin K, Qing Y, Wang L, Fan Y, Fu Q, Zhang F. Enhanced low-frequency microwave absorbing property of SCFs@ TiO2 composite. Powder Technol. 2018;333:153. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2018.04.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu H, Wu G, Ren Y, Yang L, Wang L, Li X. Co2+/Co3+ ratio dependence of electromagnetic wave absorption in hierarchical NiCo2O4–CoNiO2 hybrids. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2015;3:7677. doi: 10.1039/C5TC01716E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu H, Wu G, Wang L. Peculiar porous α-Fe2O3, γ-Fe2O3 and Fe3O4 nanospheres: Facile synthesis and electromagnetic properties. Powder Technol. 2015;269:443. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2014.09.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiu J, Nogi M, Sugahara T, et al. Ag/TiO2 core–shell nanocables prepared with a one-step polyol process. J. Nanopart. Res. 2012;14:1241. doi: 10.1007/s11051-012-1241-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu Y, Qu S, Zang D, Wang L, Wu H. Fast synthesis of Pt nanocrystals and Pt/microporous La2O3 materials using acoustic levitation. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018;13:50. doi: 10.1186/s11671-018-2467-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ismail RA, Mousa AM, Amin MH. Synthesis of hybrid Au@ PbI2 core-shell nanoparticles by pulsed laser ablation in ethanol. Mater. Res. Express. 2018;5(11):115024. doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/aadf1b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim KS, Kim DJ, Zhao QQ. Numerical analysis on particle coating by the pulsed plasma process. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2006;61(10):3278–3289. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2005.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han H, Fang Y, Li Z, Xu H. Tunable surface plasma resonance frequency in Ag core/Au shell nanoparticles system prepared by laser ablation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008;92(2):023116. doi: 10.1063/1.2829588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chacon C, Perez MR, Oskam G, Gattorno GR. Synthesis and characterization of WO3 polymorphs: Monoclinic, orthorhombic and hexagonal structures. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2015;26:5526–5553. doi: 10.1007/s10854-014-2053-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alwazny MS, Ismail RA, Salim ET. High-quantum efficiency of Au@LiNbO3 core–shell nano composite as a photodetector by two-step laser ablation in liquid. Appl. Phys. A. 2022;128:500. doi: 10.1007/s00339-022-05651-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukherjee R, Kushwaha A, Sahay PP. Spray-deposited nanocrystalline WO3 thin films prepared using tungsten hexachloride dissolved in NN dimethyl formamide and influence of in doping on their electron. Mater. Lett. 2014;10:401–410. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Liu X, Cui J, Sun J. Hydrothermal synthesis of selfassembled hierarchical tungsten oxides hollow spheres and their gas sensing properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015;7:10108–10114. doi: 10.1021/am508121p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fakhri MA, Ismail RA, Abass AK, Mohammed LZ, Alsultany FH, Hashim U. Synthesis of LiNbO3/SiO2/Si nanostructures layer by layer based on Mach–Zehnder modulator using pulsed laser deposition route. Silicon. 2022;14:11781–11795. doi: 10.1007/s12633-022-01902-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagarjuna R, Challagulla S, Sahu P, Roy S, Ganesan R. Polymerizable sol–gel synthesis of nano-crystalline WO3 and its photocatalytic Cr ( VI ) reduction under visible light. Adv. Powder Technol. 2017;28:3265–3273. doi: 10.1016/j.apt.2017.09.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muhsin MS, Salim ET, Saimon JA. Structural, morphological and optical properties of tungsten trioxide nanoparticle synthesis by pulsed laser ablation in water: Effect of laser fluence. J. Opt. 2023 doi: 10.1007/s12596-023-01368-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fakhri MA, Al-Douri Y, Bouhemadou A, Ameri M. Structural and optical properties of nanophotonic LiNbO3 under stirrer time effect. J. Opt. Commun. 2017;39(3):297–306. doi: 10.1515/joc-2016-0159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salmaoui S, Sediri F, Gharbi N, Perruchot C, Aeiyach S, Rutkowska IA, Kulesza PJ, Jouini M. Hexagonal nanorods of tungsten trioxide: synthesis, structure, electrochemical properties and activity as supporting material in electrocatalysis. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011;257:8223–8229. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2011.04.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fakhri MA, Salim ET, Abdulwahhab AW, Hashim U, Salim ZT. Optical properties of micro and nano LiNbO3 thin film prepared by spin coating. Opt. Laser Technol. 2018;103:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.optlastec.2018.01.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen HJ, Xu NS, Deng SZ, Lu DY, Li ZL, Zhou J. Gasochromic effect and relative mechanism of WO3 nanowire films. J. Chen. Nanotechnol. 2007;18:205701. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/18/20/205701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hattori Y, Nomura S, Mukasa S, Toyota H, Inoue T, Kasahara T, Alloys J. Synthesis of tungsten trioxide nanoparticles by microwave plasma in liquid and analysis of physical properties. J. Alloys Comp. 2013;560:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.01.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fakhri MA, Salim ET, Wahid MHA, Hashim U, Salim ZT. Optical investigations and optical constant of nano lithium niobate deposited by spray pyrolysis technique with injection of Li2CO3 and Nb2O5 as raw materials. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018;29(11):9200–9208. doi: 10.1007/s10854-018-8948-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qin YX, Wang F, Shen WJ, Hu M. Mesoporous threedimensional network of crystalline WO3 nanowires for gas sensing application. J. Alloys Comp. 2012;540:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2012.06.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang L, Baik SJ, Lim KS, Yoo SH, Seo MS, Kang SJ, Seo JW. Tunable work function of a WOx buffer layer for enhanced photocarrier collection of pin-type amorphous silicon solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010;96:193501. doi: 10.1063/1.3427396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abood MK, Salim ET, Saimon JA. Niobium pentoxide thin film prepared using simple colloidal suspension for optoelectronic application. Int. J. Nanoelectron. Mater. 2018;11(2):127–134. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barczuk PJ, Krolikowska A, Lewera A, Miecznikowski K, Solarska R, Augustynski J. Structural and photoelectrochemical investigation of boron-modified nanostructured tungsten trioxide films. Electrochim. Acta. 2013;104:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2013.04.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Douri Y, Fakhri MA, Badi N, Voon CH. Effect of stirring time on the structural parameters of nanophotonic LiNbO3 deposited by spin-coating technique. Optik. 2018;156:886–890. doi: 10.1016/j.ijleo.2017.12.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Hu H, Xu J, Zhu S, Ding A, Deng C. WO3 nanocubes: hydrothermal synthesis, growth mechanism, and photocatalytic performance. J. Mater. Res. 2019;34:2955–2963. doi: 10.1557/jmr.2019.189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Forbes A, Erasmus RM. Synthesis of tungsten oxide nanostructures by laser pyrolysis Bonex Wakufwa Mwakikunga Elias Sideras–Haddad and Gift Katumba Bathusile Masina. Int. J. Nanopart. 2008;1:185–202. doi: 10.1504/IJNP.2008.020895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Douri Y, Fakhri MA, Bouhemadou A, Khenata R, Ameri M. Stirrer time effect on optical properties of nanophotonic LiNbO3. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2018;203:243–248. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2017.10.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arutanti O, Nandiyanto ABD, Ogi T, Iskandar F, Kim TO, Okuyama K. Synthesis of composite WO3/TiO2 nanoparticles by flame-assisted spray pyrolysis and their photocatalytic activity. J. Alloys Compd. 2014;591:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2013.12.218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shanmugasundaram K, Thirunavukkarasu P, Ramamurthy M, Balaji M, Chandrasekaran J. Growth and characterization of jet nebulizer spray deposited n-type WO3 thin films for junction diode application. Orient. J. Chem. 2017;33(5):2484. doi: 10.13005/ojc/330542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amir HAAA, Fakhri MA, Alwahib AA, Salim ET, Alsultany FH, Hashim U. An investigation on GaN/ porous-Si NO2 gas sensor fabricated by pulsed laser ablation in liquid. Sens. Actuat. B: Chem. 2022;367:132163. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2022.132163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Erwin WR, Zarick HF, Talbert EM, Bardhan R. Light trapping in mesoporous solar cells with plasmonic nanostructures. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016;9(5):1577–1601. doi: 10.1039/c5ee03847b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jimenez-Cisneros J, Galindo-Lazo JP, Mendez-Rojas MA, Campos-Delgado JR, Cerro-Lopez M. Plasmonic spherical nanoparticles coupled withtitania nanotube arrays prepared by anodization as substrates for surface-enhancedraman spectroscopy applications: A review. Molecules. 2021;26(24):145. doi: 10.3390/molecules26247443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Aberasturi DJ, Serrano-Montes AB, Liz-Marzán LM. Modern applications of plasmonic nanoparticles: From energy to health. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2015;3(5):602–617. doi: 10.1002/adom.201500053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Y, Sun L, Xi M, Feng Q, Jiang C, Fong H. Electrospun TiO2 nanofelt surface-decorated with Ag nanoparticles as sensitive and UV-cleanable substrate for surface enhanced Raman scattering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2014;6(8):5759–5767. doi: 10.1021/am5005859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chaudhary RG, Desimone MF. Synthesis, characterization, and applications of green synthesized nanomaterials (part 1) Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2021;22:722–723. doi: 10.2174/138920102206210521165455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mostafa AM, Mwafy EA. Environmental nanotechnology. Monit. Manag. 2020;14:100382. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rahmah MI. Preparation of silver chloride nanoparticles using human urine. Appl. Nanosci. 2021;11(10):2611–2615. doi: 10.1007/s13204-021-02133-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ismail RA, Mousa AM, Amin MH. Effect of laser fluence on the structural, morphological and optical properties of 2H-PbI 2 nanoparticles prepared by laser ablation in ethanol. J. Inorg. Organometall. Polym. Mater. 2018;28:2365–2374. doi: 10.1007/s10904-018-0908-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahmah, M. I., Ahmed, A. M., Rashid, T. M. & Jabbar Qasim, A. Preparation of silver nanoparticles using laser ablation for in vitro treatment of MCF-7 cancer cells with antibacterial activity. Plasmonics. 1–9 (2023).

- 46.Mousa AM, Ismail RA, Amin MH. Hybrid p-Au@ PbI2/n-Si heterojunction photodetector prepared by pulsed laser ablation in liquid. Optik. 2019;183:933–941. doi: 10.1016/j.ijleo.2019.02.153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salim ET, Agool IR, Muhsien MA. Construction of SnO2/SiO2/Si heterojunction and its lineup using I-V and C-V measurements. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B. 2011;25(29):3863–3869. doi: 10.1142/S0217979211102022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Abdulrazzaq OA, Saleem ET. Inexpensive near-IR photodetector. Turk. J. Phys. 2006;30:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Omar MH, Amin MH, Younis HA. Comparison of using nano-ZnO and nano-Al2O3 to improve the properties of prepared polymethyl methacrylate denture base. Appl. Phys. A. 2022;128(4):313. doi: 10.1007/s00339-022-05359-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chouke PB, Dadure KM, Potbhare AK, Bhusari GS, Mondal A, Chaudhary K, Singh V, Desimone MF, Chaudhary RG, Masram DT. Biosynthesized δ-Bi2O3 Nanoparticles from Crinum viviparum Flower Extract for Photocatalytic Dye Degradation and Molecular Docking. ACS Omega. 2022;7:20983–20993. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c01745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mostafa AM, Mwafy EA, Hasanin MS. One-pot synthesis of nanostructured CdS, CuS, and SnS by pulsed laser ablation in liquid environment and their antimicrobial activity. Opt. Laser Technol. 2020;121:105824. doi: 10.1016/j.optlastec.2019.105824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aadim KA, Jasim AS. Silver nanoparticles synthesized by Nd: YAG laser ablation technique: characterization and antibacterial activity. J. Mod. Sci. 2022;8:71–82. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eisa WH, Zayed MF, Anis B, Abbas LM, Ali SS, Mostafa AM. Clean production of powdery silver nanoparticles using Zingiber officinale: The structural and catalytic properties. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;241:118398. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salim ET. Rapid thermal oxidation for silicon nanocrystal based solar cell. Int. J. Nanoelectron. Mater. 2012;5(2):95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hattab, F. & Fakhry, M. Optical and structure properties for nano titanium oxide thin film prepared by PLD, in 2012 First National Conference for Engineering Sciences (FNCES 2012). 10.1109/NCES.2012.6740474.

- 56.Muhsien MA, Salim ET, Agool IR. Preparation and characterization of (Au/n-SnO2 /SiO2/Si/Al) MIS device for optoelectronic application. Int. J. Opt. 2013;2013:9. doi: 10.1155/2013/756402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ismail RA, Rasheed BG, Salm ET, Al-Hadethy M. High transmittance-low resistivity cadmium oxide films grown by reactive pulsed laser deposition. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2007;18(10):1027–1030. doi: 10.1007/s10854-007-9129-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mostafa AM. Preparation and study of nonlinear response of embedding ZnO nanoparticles in PVA thin film by pulsed laser ablation. J. Mol. Struct. 2021;1223:129007. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Salim ET. Optoelectronic properties of Fe2O3/Si heterojunction prepared by rapid thermal oxidation method. Indian J. Phys. 2013;87(4):349–353. doi: 10.1007/s12648-012-0229-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fakhri MA, Al-Douri Y, Hashim U. Fabricated optical strip waveguide of nanophotonics lithium niobate. IEEE Photonics J. 2016;8(2):4500410. doi: 10.1109/JPHOT.2016.2531583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Muhsien MA, Salem ET, Agool IR, Hamdan HH. Gas sensing of Au/n-SnO2/p-PSi/c-Si heterojunction devices prepared by rapid thermal oxidation. Appl. Nanosci. 2014;4:719–732. doi: 10.1007/s13204-013-0244-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jurn YN, Malek F, Mahmood SA, Liu W-W, Gbashi EK, Fakhri MA. Important parameters analysis of the single-walled carbon nanotubes composite materials. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2016;11(8):5108–5113. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jeon JW, Yoon S, Choi HW, Kim J, Farson D, Cho SH. The effect of laser pulse widths on laser—Ag nanoparticle interaction: Femto-to nanosecond lasers. Appl. Sci. 2018;8:112. doi: 10.3390/app8010112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fakhri MA, Al-Douri Y, Salim ET, Hashim U, Yusof Y, Choo EB, Salim ZT, Jurn YN. Structural properties and surface morphology analysis of nanophotonic LINBO3. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2016;11(8):4974–4978. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mwafy EA, Gaafar MS, Mostafa AM, Marzouk SY, Mahmoud IS. Novel laser-assisted method for synthesis of SnO2/MWCNTs nanocomposite for water treatment from Cu (II) Diam. Relat. Mater. 2021;113:108287. doi: 10.1016/j.diamond.2021.108287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fakhri MA, Hashim U, Salim ET, Salim ZT. Preparation and charactrization of photonic LiNbO3 generated from mixing of new raw materials using spry pyrolysis method. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2016;27(12):13105–13112. doi: 10.1007/s10854-016-5455-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elsayed KA, Alomari M, Drmosh QA, Alheshibri M, Al Baroot A, Kayed TS, Manda AA, Al-Alotaibi AL. Fabrication of ZnO–Ag bimetallic nanoparticles by laser ablation for anticancer activity. Alex. Eng. J. 2022;61(2):1449–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.aej.2021.06.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Al Baroot A, Haladu SA, Ibrahim MB, Akhtar S, Alshammari AH, Taha TAM, Elsayed KA, Manda AA. Enhancement of catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol using MoO3 nanobelts incorporated SiO2 nanocomposite fabricated by nanosecond pulsed laser ablation technique. Phys. Scr. 2023;98(9):095002. doi: 10.1088/1402-4896/ace99d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Manda AA, Elsayed KA, Haladu SA, Cevik E, Ibrahim MB, Drmosh QA. Catalytic activity of cellulose acetate butyrate/TiO2-Au nanocomposite film prepared by laser ablation for 2-nitrophenol reduction. J. Polym. Environ. 2023;32:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Al Baroot A, Elsayed KA, Khan FA, Haladu SA, Ercan F, Çevik E, Drmosh QA, Almessiere MA. Anticancer activity of Au/CNT nanocomposite fabricated by nanosecond pulsed laser ablation method on colon and cervical cancer. Micromachines. 2023;14(7):1455. doi: 10.3390/mi14071455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alheshibri M, Elsayed KA, Khan FA, Haladu SA, Ercan F, Çevik E, Drmosh QA, Kayed TS, Almessiere MA. Tuning the morphology of Au/ZnO nanocomposite using pulsed laser ablation for anticancer applications. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023;49:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alheshibri M, Kotb E, Haladu SA, Al Baroot A, Drmosh QA, Ercan F, Çevik E, Elsayed KA. Synthesis of highly stable Ag/Ta2O5 nanocomposite by pulsed laser ablation as an effectual antibacterial agent. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023;162:109295. doi: 10.1016/j.optlastec.2023.109295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Al Baroot A, Haladu SA, Magami SM, Akhtar S, Drmosh QA, Elsayed KA, Manda AA. Photocatalytic performance of Ag/TiO2/SiO2 nanocomposite synthesized by eco-friendly pulsed laser ablation technique. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 2023;180:111489. doi: 10.1016/j.jpcs.2023.111489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Al Baroot A, Drmosh QA, Alade IO, Elsayed KA, Alheshibri M, Kotb E, AlQahtani HR, Al Qahtani HS. Investigating the antibacterial activity of nanostructured tungsten oxide prepared by pulsed laser ablation at different hydrogen peroxide concentrations. Opt. Mater. 2022;133:112886. doi: 10.1016/j.optmat.2022.112886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Manda AA, Elsayed K, Ibrahim MB, Haladu SA, Ercan F, Çevik E, Bozkurt A, Kayed TS, Altamimi NA, Drmosh QA. Synthesis of CuO/α-Fe2O3 nanocomposite by Q-switched pulsed laser ablation and its catalytic activity for environmental applications. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023;48(6):7635–7646. doi: 10.1007/s13369-022-07462-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.AlBaroot A, Alheshibri M, Drmosh QA, Akhtar S, Kotb E, Elsayed KA. A novel approach for fabrication ZnO/CuO nanocomposite via laser ablation in liquid and its antibacterial activity. Arab. J. Chem. 2022;15(2):103606. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Elsayed KA, Alomari M, Drmosh QA, Manda AA, Haladu SA, Alade O. Anticancer activity of TiO2/Au nanocomposite prepared by laser ablation technique on breast and cervical cancers. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022;149:107828. doi: 10.1016/j.optlastec.2021.107828. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tahani F, Hamdi R, Alkhabbaz H, Alheshibri M, Akhtar S, Ouerfelli N, Elsayed K. Physicochemical properties of nanofluids produced from oxidized nanoparticles synthesized in a liquid by pulsed laser ablation. Lasers Manuf. Mater. Process. 2022;9:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Al-Otaibi AL, Elsayed KA, Manda AA, Haladu SA, Gaya UI, Ercan F, Kayed TS, et al. Pulsed laser ablation-mediated facile fabrication of MoO3/TiO2/rGO nanocomposite as a photocatalyst for dye degradation. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024;170:110156. doi: 10.1016/j.optlastec.2023.110156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alamro FS, Mostafa AM, Al-Ola KAA, Ahmed HA, Toghan A. Synthesis of Ag nanoparticles-decorated CNTs via laser ablation method for the enhancement the photocatalytic removal of naphthalene from water. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:2142. doi: 10.3390/nano11082142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fakhri MA, Halim M, Wahid A, Badr BA, Salim ET, Hashim U, Salim ZT. Enhancement of Lithium Niobate nanophotonic structures via spin-coating technique for optical waveguides application. Eur. Phys. J. Conf. 2017;162(7):01004. doi: 10.1051/epjconf/201716201004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Song S, Wang X, Zhang H. CeO2-encapsulated noble metal nanocatalysts: enhanced activity and stability for catalytic application. NPG Asia Mater. 2015;7:e179–e179. doi: 10.1038/am.2015.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nbelayim P, Ashida Y, Maegawa K, et al. Preparation and characterization of stable and active Pt@TiO2 Core–shell nanoparticles as electrocatalyst for application in PEMFCs. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2020;3:3269–3281. doi: 10.1021/acsaem.9b02169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fatimah I, Fadillah G, Purwiandono G, et al. Magnetic-silica nanocomposites and the functionalized forms for environment and medical applications: A review. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2022;137:109213. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2022.109213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Belessiotis GV, Falara PP, Ibrahim I, et al. Magnetic metal oxide-based photocatalysts with integrated silver for water treatment. Materials. 2022;15:4629. doi: 10.3390/ma15134629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Long Y, Li J, Wu L, et al. Construction of trace silver modified core@shell structured Pt-Ni nanoframe@CeO2 for semihydrogenation of phenylacetylene. Nano Res. 2019;12:869–875. doi: 10.1007/s12274-018-2315-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Neyman KM, Kozlov SM. Quantifying interactions on interfaces between metal particles and oxide supports in catalytic nanomaterials. NPG Asia Mater. 2022;14:59. doi: 10.1038/s41427-022-00405-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ishida T, Murayama T, Taketoshi A, et al. Importance of size and contact structure of gold nanoparticles for the genesis of unique catalytic processes. Chem. Rev. 2020;120:464–525. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rupprechter G. Operando surface spectroscopy and microscopy during catalytic reactions: From clusters via nanoparticles to meso-scale aggregates. Small. 2021;17:2004289. doi: 10.1002/smll.202004289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rai P. Plasmonic noble metal@metal oxide core–shell nanoparticles for dye-sensitized solar cell applications. Sustain. Energy Fuels. 2019;3:63–91. doi: 10.1039/C8SE00336J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Liu X, Iocozzia J, Wang Y, et al. Noble metal–metal oxide nanohybrids with tailored nanostructures for efficient solar energy conversion, photocatalysis and environmental remediation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017;10:402–434. doi: 10.1039/C6EE02265K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang Q, Lee I, Joo JB, et al. Core–shell nanostructured catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:1816–1824. doi: 10.1021/ar300230s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rai P, Majhi SM, Yu Y-T, et al. Noble metal@metal oxide semiconductor core@shell nano-architectures as a new platform for gas sensor applications. RSC Adv. 2015;5:76229–76248. doi: 10.1039/C5RA14322E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li G, Tang Z. Noble metal nanoparticle@metal oxide core/yolk–shell nanostructures as catalysts: Recent progress and perspective. Nanoscale. 2014;6:3995–4011. doi: 10.1039/C3NR06787D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ismail RA, Salim ET, Halbos HT. Preparation of Nb2O5 nanoflakes by hydrothermal route for photodetection applications: The role of deposition time. Optik. 2021;245:167778. doi: 10.1016/j.ijleo.2021.167778. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Alsultany FH, Alhasan SFH, Salim ET. Seed layer-assisted chemical bath deposition of Cu2O nanoparticles on ITO-coated glass substrates with tunable morphology, crystallinity, and optical properties. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2021;31:3749–3759. doi: 10.1007/s10904-021-02016-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Abdul-Hamead AA, Othman FM, Fakhri MA. Preparation of MgO–MnO2 nanocomposite particles for cholesterol sensors. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021;32:15523–15532. doi: 10.1007/s10854-021-06102-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Abood MK, Salim ET, Saimon JA, Hadi AA. Electrical conductivity, mobility and carrier concentration in Nb2O5 films: Effect of NH4OH molarity. Int. J. Nanoelectron. Mater. 2021;14(3):259–268. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hassan MA, Al-Nedawe BM, Fakhri MA. Embedded optical fiber link interferometer sensors for snapshot surface inspection using the synthetic wavelength technique. Appl. Opt. 2021;60(8):2339–2347. doi: 10.1364/AO.417370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mohsin MH, Numan NH, Salim ET, Fakhri MA. Physical properties of sic nanostructure for optoelectronics applications. J. Renew. Mater. 2021;9(9):1519–1530. doi: 10.32604/jrm.2021.015465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fakhri MA, Wahid MHA, Kadhim SM, Badr BA, Salim ET, Hashim U, Salim ZT. The structure and optical properties of Lithium Niobate grown on quartz for photonics application. Eur. Phys. J. Conf. 2017;162:01005. doi: 10.1051/epjconf/201716201005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lijie X, Yin M, Liu SF. Superior sensor performance from Ag@ WO3 core–shell nanostructure. J. Alloys Compd. 2015;623:127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2014.10.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fakhri MA, Basheer RA, Banoosh AM, Azeez HN. Rapid thermal oxidation of nano silver film for solar cell fabrication. Digest J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2021;16(2):367–375. doi: 10.15251/DJNB.2021.162.367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Khan M, Kumar S, Ahamad T, Alhazaa A. Enhancement of photocatalytic and electrochemical properties of hydrothermally synthesized WO3 nanoparticles via Ag loading. J. Alloys Compd. 2018;743:485–493. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.01.343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hassen HH, Salim ET, Taha JM, Mahdi RO, Numan NH, Khalid FG, Fakhri MA. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and photo luminance results for Zno NPs prepared at different preparation condition using LP-PLA technique. Int. J. Nanoelectron. Mater. 2018;11(Special Issue BOND21):65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Davis EA, Mott NF. Conduction in non-crystalline systems V. Conductivity, optical absorption and photoconductivity in amorphous semiconductors. Philos. Mag. 1970;22(179):0903–0922. doi: 10.1080/14786437008221061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Salim ET, Saimon JA, Abood MK, Alsultany FH. A preliminary study on structural and optical properties of heat treated Nb2O5 nanostructure. Int. J. Nanoelectron. Mater. 2023;16(1):21–32. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hassan NK, Khalid FG, Ekshayesh AA, Dahham OS, Hussein MM. Optical investigations of gold nano rods and gold nano rods doped with ZnO nanoparticles for optoelectronic applications. J. Opt. (India) 2023;52:2023–2030. doi: 10.1007/s12596-023-01120-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Osamah S, Alwahib AA, Fakhri MA, Gopinath SCB. Study of single and symmetrical D-shaped optical fiber sensor based on gold nanorods. J. Opt. (India) 2023;52:2048–2058. doi: 10.1007/s12596-023-01119-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Imam, M. A. & Chopra, N. Morphological, Structural and Optical Characterization of Bottom-Up Growth of Ag–WO3 Core-Shell Nano-Cube Heterostructures (2017).

- 111.Abdul Amir HAA, Fakhri MA, Alwahib AA. Review of GaN optical device characteristics, applications, and optical analysis technology. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021;42:2815–2821. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Xu L, Yin M-L, Liu SF. Agx@WO3 core-shell nanostructure for LSP enhanced chemical sensors. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:6745. doi: 10.1038/srep06745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shi W, Chopra N. Controlled fabrication of photoactive copper oxide–cobalt oxide nanowire heterostructures for efficient phenol photodegradation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2012;4(10):5590–5607. doi: 10.1021/am301488c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hassan NK, Fakhri MA, Salim ET, Hassan MA. Gold nano particles based optical fibers for a different sensor in a review. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021;42:2769–2772. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Chopra N, Shi W, Lattner A. Fabrication and characterization of copper oxide (CuO)–gold (Au)–titania (TiO2) and copper oxide (CuO)–gold (Au)–indium tin oxide (ITO) nanowire heterostructures. Mater. Character. 2014;96:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.matchar.2014.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tumuluri A, Naidu KL, Raju KJ. Band gap determination using Tauc’s plot for LiNbO3 thin films. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 2014;6(6):3353–3356. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Alghurabi MNAK, Mahmood RS, Salim ET, Alhasan SFH, Khalid FG. Structure, optical, and morphological investigations of nano copper oxide prepared using RPLD at different laser wavelength effects. Mater. Today: Proc. 2021;42:2497–2501. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Amir HAAA, Fakhri MA, Alwahib AA, Salim ET, Alsultany FH, Hashim U. Synthesis of gallium nitride nanostructure using pulsed laser ablation in liquid for photoelectric detector. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022;150:106911. doi: 10.1016/j.mssp.2022.106911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Mohammed DA, Kadhim A, Fakhri MA. The enhancement of the corrosion protection of 304 stainless steel using Al2O3 films by PLD method. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018;2045(1):020014. doi: 10.1063/1.5080827. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Salim ET, Ismail RA, Halbos HT. Deposition geometry effect on structural, morphological and optical properties of Nb2O5 nanostructure prepared by hydrothermal technique. Appl. Phys. A. 2020;126:891. doi: 10.1007/s00339-020-03955-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hassan MM, Fakhri MA, Adnan SA. Structural electrical and detection properties of copper oxide based on optoelectronic device. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018;454(1):012172. doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/454/1/012172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bunaciu AA, UdriŞTioiu EG, Aboul-Enein HY. X-ray diffraction: Instrumentation and applications. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2015;45(4):289–299. doi: 10.1080/10408347.2014.949616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Salim ET, Saimon JA, Abood MK, Fakhri MA. Effect of silicon substrate type on Nb2O5/Si device performance: an answer depends on physical analysis. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2020;52(10):463. doi: 10.1007/s11082-020-02588-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Fakhri MA, Alwahib AA, Salim ET, Abdul Amir HAA, Alsultany FH, Hashim U. Synthesis and characterization of GaN/quartz nanostructure using pulsed laser ablation in liquid. Phys. Scr. 2022;97(11):115813. doi: 10.1088/1402-4896/ac9866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Awayiz MT, Salim ET. Photo voltaic properties of Ag2O/Si heterojunction device: Effect of substrate conductivity. Mater. Sci. Forum. 2020;1002:200–210. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.1002.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ali HS, Fakhri MA. An overview of Au & photonic crystal fiber of sensors. Mater. Sci. Forum. 2020;1002:282–289. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.1002.282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Mahdi RO, Fakhri MA, Salim ET. Physical investigations of niobium oxide nanorod imploring laser radiation. Mater. Sci. Forum. 2020;1002:211–220. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.1002.211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Cullity BD. Elements of X-ray diffraction. Addison-Wesley PUBLISHING; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Fakhri MA, Salim ET, Tariq SM, Ibrahim RK, Alsultany FH, Alwahib AA, Alhasan SFH, Gopinath SCB, Salim ZT, Hashim U. A gold nanoparticles coated unclad single mode fiber-optic sensor based on localized surface plasmon resonance. Sci. Rep. 2023;13:5680. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-32852-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Adam H, Gopinath SCB, Md Arshad MK, Sasidharan S, Wu YS. Integration of microfluidic channel on electrochemicalbased nanobiosensors for monoplex and multiplex analyses: an overview. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2023;146:104814. doi: 10.1016/j.jtice.2023.104814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Taleb SM, Fakhri MA, Adnanm SA. Optical Investigations of nanophotonic LiNbO3 films deposited by pulsed laser deposition method, defect and diffusion. Forum. 2020;398:16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hassan MM, Fakhri MA, Adnan SA. Structural and morphological properties of nano photonic silicon structure for photonics applications, defect and diffusion. Forum. 2020;398:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Adnan SA, Tawfiq ZH, Fakhri MA. Gold nanoparticles in liquid based on photonic crystal fiber PCF for sensors application, defect and diffusion. Forum. 2020;398:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Fakhri MA, Salim ET, Abdulwahhab AW, Hashim U, Minshid MA, Salim ZT, Salim ZT. The effect of annealing temperature on optical and photolumence proper. Surf. Rev. Lett. 2019;26(10):1950068. doi: 10.1142/S0218625X19500689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Salim ET, Awayiz MT, Mahdi RO. Tea concentration effect on the optical, structural, and surface roughness of Ag2O thin films. Digest J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2019;14(4):1151–1159. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Hassan MM, Fakhri MA, Adnan SA. 2-D of nano photonic silicon fabrication for sensing application. Digest J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2019;14(4):873–878. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Taleb SM, Fakhri MA, Adnan SA. Physical investigations of nanophotonic LiNbO3 films for photonic applications. J. Ovonic Res. 2019;15(4):261–269. [Google Scholar]

- 138.Jiawang M, Ma Z, Liu B, Wang S, Ma R, Wang C. Composition of Ag–WO3 core-shell nanostructures as efficient electrocatalysts for hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Solid State Chem. 2019;271:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jssc.2018.12.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Ro I, Resasco J, Christopher P. Approaches for understanding and controlling interfacial effects in oxide-supported metal catalysts. ACS Catal. 2018;8:7368–7387. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b02071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Badr BA, Mohammed QQ, Numan NH, Fakhri MA, Abdul Wahhab AW. Substrate temperature effects on optical properties and constants of ZnO. Int. J. Nanoelectron. Mater. 2019;12(3):283–290. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Abdulrahman, T. E., Salim, E. T., Mahdi, R. O. & Wahid, M. H. A. Nb2O5 nano and microspheres fabricated by laser ablation. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol.13, 045006. 10.1088/2043-6262/ac99cf (2022).

- 142.Imam, M. A. & Chopra. N. Morphological, Structural and Optical Characterization of Bottom-Up Growth of Ag–WO3 Core-Shell Nano-cube Heterostructures (2017).

- 143.Salim ET, Fakhri MA, Ismail RA, Abdulwahhab AW, Salim ZT, Munshid MA, Hashim U. Effect of light induced heat treatment on the structural and morphological properties of LiNbO3 thin films. Super Lattices Microstruct. 2019;128:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.spmi.2019.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Xu, L., Yin, M.-L. & Liu, S. Agx@WO3 core-shell nanostructure for LSP enhanced chemical sensors. Sci. Rep.4, 6745 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 145.Ahemad, M. J., Le, T. D., Kim, D.-S. et al. Bimetallic AgAu alloy@ZnO Core–Shell Nanoparticles for Ultra-High Detection Of Ethanol: Potential Impact of Alloy.

- 146.Abood M, Salim ET, Saimon JA. Optical investigations of Nb2O5 at different teamperatures for optoelectronic devices. J. Ovonic Res. 2019;15(2):109–115. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Salim ET, Halboos HT. Synthesis and physical properties of Ag doped niobium pentoxide thin films for Ag-Nb2O5/Si heterojunction device. Mater. Res. Express. 2019;6(6):066401. doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/ab07d3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Badr BA, Numan NH, Khalid FG, Fakhri MA, Abdulwahhab AW. Effetcts of substrate temperatures on optical properties and constants of ZnO prepared by PLD. J. Ovonic Res. 2019;15(2):127–133. [Google Scholar]

- 149.Fakhri MA, Abdulwahhab AW, Kadhim SM, Alwazni MS, Adnan SA. Thermal oxidation effects on physical properties of CuO2 thin films for optoelectronic application. Mater. Res. Express. 2018;6(2):026429. doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/aaf217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Wu, C.-C. Highly flexible touch screen panel fabricated with silver inserted transparent ITO triple-layer structures, I. RSC Adv.8(22), 11862–11870 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 151.Huang, P.-S., Qin, F. & Lee, J.-K. Role of the interface between Ag and ZnO in the electric conductivity of Ag nanoparticle-embedded ZnO. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces12(4), 4715–4721 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 152.Fakhri MA, Salim ET, Wahid MHA, Abdulwahhab AW, Hashim U, Salim ZT. Efficiency enhancement of optical strip waveguide by the effect of heat treatment. Optik. 2019;180:768–774. doi: 10.1016/j.ijleo.2018.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Suresh, S., Gautam E., Unni, M., Satyanarayana, A., Nair, S. & Pillai, V.P.M. Ag@ Nb2O5 plasmonic blocking layer for higher efficiency dye-sensitized solar cells. Dalton Trans. 47(13), 4685–4700 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 154.Salim, E. T., Shafeeq, S. R., AbdulRazzaq, M. J., Fakhri, M. A. & Gopinath, S. C. B. Photo-activation of Ag chemicals for enhanced Nb2O5 optoelectronic device employing plasmonic effects. Surf. Interfaces36, 102618 (2023).

- 155.Salim, E. T., Saimon, J.A., Abood, M. K. & Fakhri, M. A. Electrical conductivity inversion for Nb2O5 nanostructure thin films at different temperatures. Mater. Res. Express6(12), 126459. 10.1088/2053-1591/ab771c (2019).

- 156.Salim, E. T., Hassan, A. I., Mohamed, F. A. & Fakhri, M. A. Photoactivation of Ag ions for improved WO3-based optoelectronic devices. J. Opt.10.1007/s12596-023-01596-x (2024).

- 157.Badr BA, Numan NH, Khalid FG, Fakhri MA, Abdulwahhab AW. All optical investigations of copper oxide for detection devices. J. Ovonic Res. 2019;15(1):53–59. [Google Scholar]

- 158.Al Wazny, M. S., Salim, E. T., Bader, B. A. & Fakhry, M. A. Synthesis of Bi2O3 films, studying their optical, structural, and surface roughness properties. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 454(1), 012160. 10.1088/1757-899X/454/1/012160 (2018).

- 159.Halboos HT, Salim ET. Silver doped niobium pentoxide nanostructured thin film, optical structural and morphological properties. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018;454(1):012174. doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/454/1/012174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Tawfiq ZH, Fakhri MA, Adnan SA. Photonic crystal fibres PCF for different sensors in review. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018;454(1):012173. doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/454/1/012173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Cisneros-Contreras, I. R., Muñoz-Rosas, A. L. & Rodríguez-Gómez, A. Resolution improvement in Haacke’s figure of merit for transparent conductive films. Results Phys.10.1016/j.rinp.2019.102695 (2019).

- 162.Amin MH, Hasan JA, Rashid FH, et al. A comprehensive investigation of structural, optical, morphological, and electrical properties of CuO-NPs synthesized by pulsed laser ablation in water: Effect of laser fluence. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2024;35:210. doi: 10.1007/s10854-024-11954-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Mohammed DA, Fakhri MA, Kadhim A. Reduction the corrosion rate of 304 stainless steel using pulsed laser shock penning method. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018;454(1):012162. doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/454/1/012162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Evan T. Salim, Maryam S. Muhsin, Makram A. Fakhri.