Abstract

The primary objective of this systematic review with meta-analysis is to methodically discern and compare the impact of diverse warm-up strategies, including both static and dynamic stretching, as well as post-activation potentiation techniques, on the immediate performance of gymnasts. Adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, this paper evaluated studies that examined the gymnasts’ performance after different warm-up strategies namely stretching (static [SS] or dynamic), vibration platforms (VP) or post-activation, in comparison to control conditions (e.g., mixed warm-up routines; no warm-up). The principal outcomes were centered on technical performance metrics (e.g., split, gymnastic jumps) and physical performance metrics (e.g., squat jump, countermovement jump, drop jump, balance, range of motion). Methodological assessments of the included studies were conducted using the Downs and Black Checklist. From the initial search across PubMed, Scopus, and the Web of Science databases, a total of 591 titles were retrieved, and 19 articles were ultimately incorporated in the analysis. The results revealed a non-significant differences (p > 0.05) between the SS condition and control conditions in squat jump performance, countermovement jump and gymnastic technical performance (e.g., split; split jump). Despite the difference in warm-up strategies and outcomes analyzed, the results suggest that there is no significant impairment of lower-limb power after SS. Additionally, technical elements dependent on flexibility appear to be enhanced by SS. Conversely, dynamic stretching and VP seem to be more effective for augmenting power-related and dynamic performance in gymnasts.

Key points.

There is no significant impairment of lower-limb power after static stretching

Technical elements dependent on flexibility appear to be enhanced by static stretching

Dynamic stretching and vibration platforms seem to be more effective for augmenting power-related and dynamic performance in gymnasts

Key words: Gymnastics, warm-up, warming-up, stretch, performance

Introduction

In the realm of gymnastics, a well-structured warm-up regimen is a crucial component for optimizing overall performance aspects, including physical, technical, and cognitive performance (Guidetti et al., 2009). Combining physiological and biomechanical considerations reveals the multifaceted significance of warming up in addition to the conventional understanding of warming up merely as a preparatory phase (Behm et al., 2021). The elevated muscle temperature achieved through a systematic warm-up routine increases flexibility and joint mobility (Opplert and Babault, 2018), enabling gymnasts to perform complex movements better. Furthermore, researches have shown that increased temperature enhances central nervous system function and augments the transmission speed of nervous impulses, potentially benefiting overall athletic performance (Bishop, 2003).

In the context of gymnastics warm-up protocols, the choice between static stretching (SS) and dynamic stretching (DS) methods induces various benefits and disadvantages (Siatras et al., 2003). Several studies indicated that SS may provide benefits such as enhanced muscle flexibility and joint range of motion (Behm and Chaouachi, 2011). However, SS might also impair neuromuscular activation (Chaabene et al., 2019), potentially worsening the dynamic and explosive movements included into gymnastic routines (Siatras et al., 2003). Meanwhile, dynamic warm-ups, particularly when incorporating sport-specific exercises, are likely to induce a more comprehensive physiological and neural preparatory response (Ahmadabadi et al., 2015). Nevertheless, an accurate design is needed to ensure that the warm up routine adequately addresses the diverse demands of gymnastic performances (Takeuchi et al., 2019).

Post-activation potentiation enhancement (PAPEs) (Blazevich and Babault, 2019) that arise from intense maximal contractions introduce an additional stimulus to the preparatory phase (Sale, 2002). Including intense contractions in warm-ups may increase muscle temperature, and muscle fiber water content, as well as muscle activation (Blazevich and Babault, 2019). This effect could improve the early stages of gymnastic performances (Dallas et al., 2019). PAPEs may also contribute to heightened neural drive, potentially increasing the maximum voluntary rate of force development and maximal muscle force (Hodgson et al., 2005). These enhancements in muscle function may substantially improve the dynamic and explosive movements of gymnastic.

The literature lacks comprehensive systematic reviews and meta-analyses investigating the effects of various warm-up strategies for gymnasts (Siatras et al., 2003; Guidetti et al., 2009). The lack of a synthesized overview makes it challenging to draw definitive conclusions about the most effective warm-up protocols for gymnastics. A systematic review and meta-analysis would offer a valuable and comprehensive perspective on the effects of warm-up approaches, providing a broad overview of the evidence on this topic. Such a study could also highlight the specific interventions that consistently yield positive outcomes, offering gymnasts and coaches evidence-based insights into how they can optimize warm-up routines.

Given the considerations outlined above, the principal objective of this systematic review with meta-analysis is to systematically analyze and compare the impacts of various warm-up strategies, including SS and DS, as well as post-activation potentiation techniques, on the immediate performance of gymnasts.

Methods

The registration

Adhering to the rigorous standards delineated by the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, this systematic review was conducted. A comprehensive protocol outlining our review procedures has been formally documented on the Open Science Framework (OSF) platform, assigned the project number osf.io/fk6vz, and accompanied by a DOI:10.17605/OSF.IO/FK6VZ.

Eligibility criteria

In our systematic review and meta-analysis, we have thoroughly incorporated all original articles published in peer-reviewed journals, including those in "ahead-of-print" status. Language restrictions were intentionally avoided to ensure a comprehensive range of articles.

Our establishment of eligibility criteria adhered to the PICOS framework, and a detailed breakdown of these criteria can be found in Table 1. These criteria were carefully formulated to include studies involving gymnasts from any speciality, competitive level, age, or sex, with a minimum requirement of being at least tier 2 (trained/developmental, associated with local-level representation, regular training ~3 times per week, and training with a purpose to compete) on the Participants Classification Framework, which classifies a spectrum of exercise backgrounds and athletic abilities (McKay et al., 2022).

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria based on PICOS.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Gymnasts from any speciality, competitive level, age, or sex, with a minimum requirement of being at least tier 2 (trained/developmental) on the Participants Classification Framework (McKay et al., 2022). | Excluded from the analysis were individuals falling into categories such as other athletes, participants without formal gymnastics training. Additionally, studies incorporating mixed populations, where results included as example volleyball and gymnastics, were excluded due to the absence of stratification within these cohorts. |

| Intervention/exposure | Warm-up strategies exclusively using (1) static stretching; (2) dynamic stretching; (3) post-activation potentiation (PAPE) through intense voluntary contraction; and (4) vibration platforms (VP). | The exclusion criteria involved studies incorporating combined approaches, specifically those featuring a combination of static and dynamic stretching, interventions where post-activation potentiation (PAPE) included stretching, or instances where other combinations with diverse training approaches were employed. |

| Comparator | Comparators were meticulously selected for both scenarios, whether involving cross-over designs or parallel studies. Passive controls, representing a parallel group or condition with comparable characteristics but not exposed to any warm-up intervention, were considered. Additionally, active controls were incorporated, representing a parallel group or condition in which gymnasts were exposed to alternative approaches (e.g., VP, proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation). | The exclusion criteria involved studies incorporating combined approaches. |

| Outcomes | We focused on parameters related to acute gymnastic performance, including athletic physical performance (e.g., jumping performance, muscular power, range of motion), technical performance (e.g., executing specific gymnastics technical exercises), and cognitive/mental performance (e.g., increasing attentional focus, cognitive arousal), assessed at least in two time-points (control and after exposure to intervention). | Chronic adaptations or outcomes beyond those delineated in the inclusion criteria (e.g., well-being). |

| Study design | The review will include studies that utilize either experimental or observational studies, either parallel or crossover. | Non-controlled studies. |

In the context of warm-up interventions, the criteria were clearly outlined, requiring participants to engage in, at least, one of the following warm-up strategies: (1) SS; (2) DS; (3) PAPE; and (4) vibrating platforms. The control group consisted of gymnasts who performed warm-up types that did not include SS, DS, PAPE, and VP.

Regarding our primary outcomes, we focused on parameters related to acute gymnastic responses, including athletic physical performance (e.g., jumping performance, muscular power, range of motion), technical execution (e.g., executing specific gymnastics technical exercises), and cognitive/mental performance (e.g., increasing attentional focus, cognitive arousal). Eligible study types included experimental or observational studies, either cross-sectional or parallel.

To ensure a thorough evaluation, a comprehensive review of the full texts was conducted to ascertain their eligibility for inclusion in the review.

Information sources

Our approach to identifying pertinent studies entailed a thorough search across multiple databases, namely: (i) PubMed, (ii) Scopus, and (iii) Web of Science, up to November 13, 2023. To enhance the comprehensiveness of our methodology and mitigate the risk of overlooking relevant materials, we additionally conducted manual searches within the reference lists of the studies included into our review.

Search strategy

The search was conducted employing Boolean operators AND/OR, with a decision to refrain from using filters or constraints concerning publication dates or language. This approach was implemented to enhance the probability of identifying relevant studies. All the terms included were searched within the title and abstract. It is noteworthy that in PubMed and Scopus databases, the keywords were also selected. In the Web of Science – Core Collection, the terms were chosen specifically as topics. The exact code line used for conducting these searches was: ((Gymnastic* OR gymnast*) AND ("Warm-Up*" OR "Warmup*" OR "Warming-Up*" OR "Warming Up*"OR "static* stretch*"OR "dynamic* stretch*" OR "stretch*" OR "proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation" OR "PNF" OR "Post-activation potentiation" OR "post-activation" OR "PAP" OR "postactivation potentiation")).

Selection process

The screening process was conducted by two of the authors. They independently reviewed the retrieved records, including both titles and abstracts. Subsequently, each author individually assessed the full texts of the selected records. In instances where discrepancies in the evaluation arose, a collaborative reevaluation process was initiated to reach a consensus. If a consensus could not be achieved, the final decision was deferred to a third author.

To streamline record management, we employed EndNote X9.3.3 software, developed by Clarivate Analytics in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Data collection process

The data collection process was independently carried out by two of the authors. In cases where disagreements emerged during this phase, a third author served as a mediator. To improve efficiency and uphold organization throughout this procedure, we employed a dedicated Microsoft® Excel datasheet. This datasheet included all relevant data and essential information, ensuring a structured and effective approach to data management.

Data items

The data collection process involved extracting a comprehensive range of participant details and contextual factors. These variables included details, as the publication date, primary research objectives, sample size, country of origin, age distribution, sex, study design specifics, and the competitive level of the participants.

Regarding intervention-related conditions, we documented information regarding the study duration, training context, and various aspects of the training regimen. This involved specific details on the duration, repetitions, rest intervals, intensity, frequency, and training density.

Moreover, we extracted information from both the experimental and control groups. This included details regarding the type of exercises, exercise intensity, and volume.

Our primary focus during the extraction of main outcomes was based on parameters associated with acute gymnastic responses. This included assessments of athletic physical performance, such as jumping, muscular power, and range of motion; technical execution, including the quality of specific gymnastics technical exercises; and cognitive/mental performance, which involved measures to evaluate attentional focus and cognitive arousal. These measures were collected both before (baseline) and after the intervention, guaranteeing a minimum of two time points for assessing performance.

Study risk of bias assessment

In the case of non-controlled studies, we evaluated the methodological quality of the included studies by applying a set of 27 criteria outlined in the modified Downs and Black Checklist (Downs and Black, 1998; Simic et al., 2010). This checklist categorizes its 27 items into distinct domains, namely "reporting" (10 items), "external validity" (3 items), "internal validity - bias" (7 items), "internal validity - confounding (selection bias)" (6 items), and "power" (1 item) (Trac et al., 2016).

Each item was assigned a score of either 0 (indicating poor quality) or 1 (indicating good quality), except for question 5 ("clear description of principal confounders"), which had a scoring range from 0 (not satisfactory) to 2 (fully satisfactory). Consequently, each study had the potential to attain a maximum score of 28.

To assess study quality, we established the following thresholds: (i) poor quality (<14 points); (ii) fair quality (14-18 points); (iii) good quality (19-23 points); and (iv) excellent quality (24-28 points). This systematic approach ensured a comprehensive evaluation of the methodological rigor across the included studies.

Summary measures, synthesis of results, and publications bias

Effect sizes, specifically Hedges' g, were calculated for variables related to gymnastic performance in both intervention and control groups. These measurements were obtained from the means and standard deviations before and after the intervention, and the standardization was conducted using the standard deviation values after the intervention. To account for potential differences between studies that could impact warm-up effects, the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model was utilized (Deeks et al., 2008; Kontopantelis et al., 2013).

The representation of effect size (ES) values incorporated 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), with interpretation based on a scale: <0.2 for trivial, 0.2-0.6 for small, >0.6-1.2 for moderate, >1.2-2.0 for large, >2.0-4.0 for very large, and >4.0 for extremely large effects (Hopkins et al., 2009). Subsequently, it was considered pertinent to exclude a study from a specific meta-analysis if its ES value was ≥2, as such a result is considered atypical in warm-up studies following most interventions and may be identified as an outlier. (Kadlec et al., 2023).

To assess the influence of heterogeneity, I2 statistics were employed, categorizing values as <25% for low impact, 25-75% for moderate impact, and >75% for high impact. To investigate the potential publication bias in continuous variables, the extended Egger's test was applied. To mitigate this bias, a sensitivity analysis was carried out using the trim and fill method, with L0 as the default estimator for the number of missing studies. All statistical analyses were executed using SPSS (version 28, IBM, USA), and the significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Study Identification and Selection

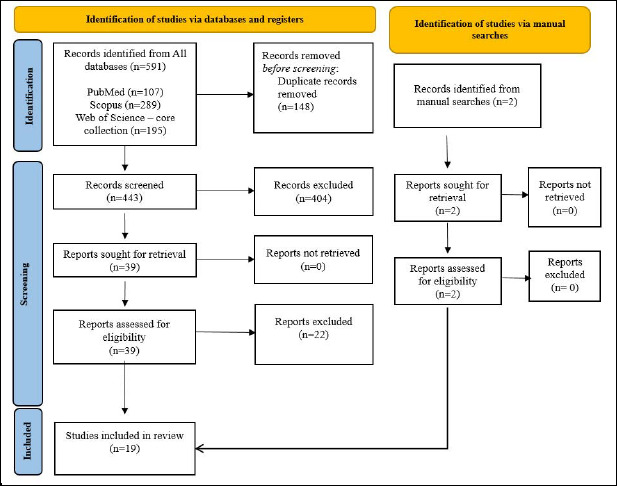

Figure 1 illustrates the outcomes of our initial investigation, revealing a total of 591 titles. Seventeen studies that adhered to our predetermined eligibility criteria were identified. In addition to our database screening, we conducted an extensive manual search within the references cited in the selected articles. This supplementary search revealed two additional articles meeting our inclusion criteria. Consequently, our systematic review included a total of 19 articles (Supplementary Material 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Supplementary material 1.

List of articles included and excluded during full-text screening.

| STUDIES | POPULATION | INTERVENTION | COMPARATOR | OUTCOMES | DESIGN | DECISION |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute versus Chronic dynamic warm-up on balance and balance the vault performance in skilled gymnast | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| The effect of stretching exercise on maximum peak torque | N | Y | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| Active vascular gymnastic: Principles and technique | N | N | N | N | N | EXCLUDED |

| Intermittent but Not Continuous Static Stretching Improves Subsequent Vertical Jump Performance in Flexibility-Trained Athletes | Y | Y | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| The effect of two different conditions of whole-body vibration on flexibility and jumping performance on artistic gymnasts | Y | N | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| Acute effect of different stretching methods on flexibility and jumping performance in competitive artistic gymnasts | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| The effect of different duration of dynamic stretching on sprint run and agility test on female gymnast | Y | Y | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| Acute effects of dynamic and pnf stretching on leg and vertical stiffness on female gymnasts | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| Acute effects of bilateral and unilateral whole body vibration training on jumping ability, asymmetry, and bilateral deficit on former artistic gymnasts | Y | N | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| Acute effect of bounce drop jump and countermovement drop jump with and without additional load on jump performance parameters and reactive strength index on young gymnasts | Y | N | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| Acute enhancement of jumping performance after different plyometric stimuli in high level gymnasts is associated with postactivation potentiation | Y | Y | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| Preexercise static stretching effect on leaping performance in elite rhythmic gymnasts | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| Effects of baseline levels of flexibility and vertical jump ability on performance following different volumes of static stretching and potentiating exercises in elite gymnasts | Y | Y | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| Flexibility training in preadolescent female athletes: Acute and long-term effects of intermittent and continuous static stretching | Y | Y | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| Acute effects of intermittent and continuous static stretching on hip flexion angle in athletes with varying flexibility training background | Y | Y | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| Acute and long-term effects of two different static stretching training protocols on range of motion and vertical jump in preadolescent athletes | Y | Y | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| The relationship between stretching and jumping in artistic gymnastics | Y | N | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| Effect of dynamic range of motion and static stretching techniques on flexibility, strength and jump performance in female gymnasts | Y | N | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| Static-stretching vs. Contract-relax - proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching: study the effect on muscle response using tensiomyography | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| The post activation potentiation effect of two different conditioning stimuli on drop jump parameters on young female artistic gymnasts | Y | Y | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| Precompetition warm-up in elite and subelite rhythmic gymnastics | Y | N | N | N | N | EXCLUDED |

| Six mobilization exercises for active range of hip flexion | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | EXCLUDED |

| Effects of drop jumps added to the warm-up of elite sport athletes with a high capacity for explosive force development | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | EXCLUDED |

| The acute effects of stretching with vibration on dynamic flexibility in young female gymnasts | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| Static stretch versus Mulligan Concept - long-term effects in gymnast's flexibility | Y | N | N | Y | N | EXCLUDED |

| Vibration and stretching effects on flexibility and explosive strength in young gymnasts | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| Acute static stretching reduces lower extremity power in trained children | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| Acute effects of vibration-assisted stretching are more evident in the non-dominant limb | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| Effects of different stretching methods on vertical jump ability and range of motion in young female artistic gymnastics athletes | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| The effect of different stretching protocols on vertical jump measures in college age gymnasts | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| Effectiveness of the conjugate influence method in improving static and dynamic balance in rhythmic gymnastics gymnasts | Y | N | N | N | N | EXCLUDED |

| Acute effects of prolonged static stretching on jumping performance and range of motion in young female gymnasts | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| Benefit of propioceptive neuromuscular facilitation on the joint mobility of youth-aged female gymnasts with correlations for rehabilitation | Y | N | N | N | N | EXCLUDED |

| Flexibility enhancement with vibration: Acute and long-term | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| Effect of vibration on forward split flexibility and pain perception in young male gymnasts | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| Static and Dynamic Acute Stretching Effect on Gymnasts' Speed in Vaulting | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| Synergist and antagonist muscles static stretching acute effect during a V-sit position on parallel bars | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| Effects of warm-up exercises with interval training on fitness of gymnasts | Y | N | N | N | N | EXCLUDED |

| The effect of different types of warm-up protocols on the range of motion and on motor abilities of rhythmic gymnastics athletes and ballet dancers | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| Manual searches | ||||||

| The acute effect of whole body vibration training on flexibility and explosive strength of young gymnasts | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

| The immediate effect of vibration therapy on flexibility in female junior elite gymnasts | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | INCLUDED |

Y: yes; N: no

Assessment of the risk of bias

Figure 2 illustrates the assessment of the risk of bias using the Downs and Black Checklist. Of the included studies, all of them ranged between 14 and 17 points, placing them within the classification of fair quality. The lack of blinding for both participants and evaluators, as well as the absence of a sample size estimation were the most common issues hindering the generalization of findings. Detailed scores for each assessment item are provided in Supplementary Material 2.

Figure 2.

Final scores on the Downs and Black Checklist for each of the included studies.

Supplementary material 2.

Assessments of risk of bias for each included study.

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q14 | Q15 | Q16 | Q17 | Q18 | Q19 | Q20 | Q21 | Q22 | Q23 | Q24 | Q25 | Q26 | Q27 | Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmadabadi et al. (2015b) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 15 |

| Dallas et al. (2014b) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 15 |

| Dallas et al. (2014a) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Dallas et al. (2021) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 16 |

| Di Cagno et al. (2010) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 15 |

| Manso et al. (2015) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| Johnson et al. (2019) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 17 |

| Kinser et al. (2008) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 16 |

| McNeal and Sands (2003) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| McNeal et al. (2011) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 15 |

| Melocchi et al. (2021) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 15 |

| Montalvo and Dorgo (2020) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 15 |

| Papia et al. (2018) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 15 |

| Sands et al. (2006) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 15 |

| Sands et al. (2008) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 15 |

| Siatras et al. (2003b) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| Siatras (2014) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| Zaggelidou et al. (2023) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| Van Zyl et al. (2011) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 16 |

1: Yes; 2: No; N/A: not applicable; Q; number of the question presented in Downs & Black quality checklist (Downs and Black, 1998)

Characteristics of the individual studies

Table 2 describes the principal characteristics of the individual studies incorporated in the present systematic review.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Study | N | Age (years old) |

Sex | Discipline | Conditions | Description of the warm-up | Outcomes extracted | Instruments/tests for measuring the outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | 16 | 9.62 ± 1.45 | Girls | ND | DS; Control (no warm-up) |

DS: Engage in 12 stretching routines, each performed twice with 8-10 repetitions for every exercise. Allow a 5-second preparation interval before transitioning to the next exercise. | Static Double Eyes Open (SDEO); Static Single Eyes Open (SSEO); Dynamic Double Eyes Open (DDEO); Dynamic Single Eyes Open (DSEO) Balance the vault | Force plate (measuring balance); Vault test |

| Dallas et al., 2014b | 18 | 21.83 ± 1.76 | Women and men | Artistic | SS; PNF; VP | Each participant executed a series of three stretching exercises targeting the knee flexors (hamstrings), knee extensors (quadriceps muscle), and plantar flexors (soleus muscle-gastrocnemius) within each of the three distinct warm-up interventions. Each exercise was sustained for a duration of 15 seconds, reaching a level of mild discomfort, and followed by a 15-second rest period before transitioning to the next exercise. This sequence was repeated three times for each warm-up method, resulting in a total of 3 exercises x 15 seconds within each warm-up routine. | CMJ; SJ; Sit and reach | Optical acquisition system for measuring CMJ and SJ; Sit-and-reach box |

| Dallas et al., 2014a | 34 | 9.22 ± 1.34 | Girls and boys | Artistic | SS; VP | SS: Participants underwent a singular training session employing various execution forms for three distinct exercises. For the initial exercise, they performed one squat every 4 seconds, adhering to the experimental design (resulting in 6-8 squats in total), with each squat reaching a depth of approximately 90° of knee flexion. The second and third exercises involved standing on one leg, flexing their knee to around 120° of knee flexion, and replicating the movement pattern from the preceding exercise. Each exercise lasted for 30 seconds. Overall, they completed two sets of 30 seconds for the first exercise and one set of 30 seconds for the second and third exercises, with a 30-second rest interval between sets. VP: made the same as SS, but with VP working. | CMJ; SJ; single leg SJ; Sit and reach | Switch mat for CMJ and SJ; Sit-and-reach box |

| Dallas et al., 2021 | 31 | 22.32 ± 3.35 | Women | Artistic, rhythmic, team gymnastics | DS; PNF; Control (no stretching) | DS: Participants engaging in Dynamic Stretching contracted the antagonistic muscles of the target areas intentionally while maintaining an upright standing position. They flexed or extended the relevant joints once every 2 seconds for each leg alternately. This dynamic stretching routine was executed for a total duration of 80 seconds, focusing on the quadriceps, hamstrings, hip extensors, and plantar flexors. PNF: Combining static stretching (SS) with isometric contractions, PNF involved two repetitions of each stretching exercise for the quadriceps, hamstrings, hip extensors, and plantar flexors. Participants held each stretch for 10 seconds at a point of discomfort, avoiding pain, with no rest between repetitions. The entire stretching session lasted for 4 minutes. Control: the control group engaged in a 5-minute treadmill run as part of their warm-up routine. | Contact time; flight time; step length; step rate; leg length; vertical displacement of the center of mass; leg stiffness; vertical stiffness; maximal ground reaction force | Vertical stiffness during treadmill running |

| Di Cagno et al., 2010 | 38 | 14.1 ± 3.2 | ND | ND | SS; control (regular warm-up) | SS: Four distinct lower body stretching exercises were incorporated into the routine, including a seated bilateral hamstring stretch, a standing unilateral calf stretch performed both with and without a bent knee, and a standing unilateral quadriceps stretch. Each stretch was repeated three times, with each repetition sustained for more than 30 seconds, reaching a point of mild discomfort. A rest period of approximately 2 minutes was observed between each exercise, and a longer 4-minute interval was allowed between sets of stretching exercises. Control: consisted of a 4-minute jogging session, followed by 4 minutes of dynamic plyometric training and hopping. Subsequently, participants engaged in 10 minutes of ballistic stretching to enhance leg and back flexibility. The warm-up regimen concluded with a focused 2-minute session targeting abdominal and dorsal muscle strength training. | flight time; and ground contact time on SJ, CMJ and Hopping test Leap performance | Optical acquisition system for measuring CMJ, SJ and Hopping test; Leap test |

| Manso et al., 2015 | 10 | 13.2 ± 1.8 | Girls | Rythmic | SS; PNF | SS: The regimen involves a sequence of 10 repetitions, with each contraction lasting for 5 seconds, followed by an intense 10-second phase of maximum forced stretching and concluding with a brief 2-second relaxation. The entire process spans a total duration of 150 seconds. PNF: This technique comprises 15 repetitions, each featuring a robust 10-second phase of maximum forced stretching coupled with a 5-second relaxation interval between each stretch. The overall duration of this exercise routine also amounts to 150 seconds. | Maximum radial deformation or displacement of the muscle belly, speed of response at 3 mm deformation, length of time for which the contraction was maintained and relaxation time | Tensiomyography |

| Johnson et al., 2019 | 27 | 11.5 ± 1.7 | Girls | ND | SS; VP | SS: Each participant completed four sets of three stretches, dedicating 30 seconds to each stretch and incorporating a 5-second rest interval between stretches. VP: the same of SS, but with VP on. |

Dynamic split jump flexibility; jump height. | Split jump |

| Kinser et al., 2008 | 22 | 11.3 ± 2.6 | Girls | ND | SS; VP | VP: The protocol involved 10 seconds of vibration-assisted stretching, followed by a 5-second rest interval between stretches, implemented at four specific sites. This process was repeated four times in a vertically loaded/cyclic manner. Each athlete traversed all four sites, repeating the same sequence three additional times, ensuring adequate exposure and rest between each site. The stretching was executed to the point of discomfort. SS: Similar to VP, participants assumed identical positions, but without the addition of vibration. | Right and left forward-split; CMJ; SJ | Forward-split; CMJ and SJ on force-plate. |

| McNeal and Sands, 2003 | 13 | 13.3 ± 2.6 | Girls | Artistic | SS; control (no warm-up) | SS: Three fundamental exercises form a common foundation in gymnastics preparation. In the stair stretch, participants were guided to lower their heels off the edge of a stair, reaching their maximum range of motion. The partner supine stretch involved the investigator applying resistance to the ball of the foot, aiming to achieve maximal dorsiflexion of the gymnast's ankle while maintaining a straight leg. Lastly, in the pike stretch, gymnasts assumed a seated pike position, bending forward at the hips toward their feet. Here, the investigator applied resistance to the feet, emphasizing maximal dorsiflexion of the ankle. To ensure consistency in stretching intensity, all stretches were assisted and supervised by the same investigator. Each stretching position was held for a duration of 30 seconds, with the range of motion extended to the point where the gymnast indicated mild discomfort verbally. Control: Did not engage in a warm-up. | DJ (flight time; ground time) | Drop jump test |

| McNeal et al., 2011 | 22 | 13.8 ± 2.2 | Girls | Artistic | SS; VP | SS: The stretching intervention involved adopting a forward split position with a focus on the front leg hamstring muscle group, followed by a forward lunge position emphasizing the rear leg quadriceps muscle group. For each position, participants completed four sets of stretches, each lasting 10 seconds, with a 5-second rest between sets. VP: Mirroring the SS routine, participants replicated the same positions but incorporated vibration. | Split angle | Forward split |

| Melocchi et al., 2021 | 8 | 14 ± 2 | Girls | ND | SS; DS; Control (no stretching) | SS: Within the repertoire of ten exercises, including the low lunge pose, forward split, and thoracic bridge, each individual stretch was sustained for a duration ranging from 15 to 20 seconds. The cumulative time spent on these exercises amounted to approximately 3 minutes. DS: Comprising seven exercises such as torso rotation, shoulder pass-through, and lateral lunge, participants completed between 3 to 10 repetitions for each exercise. The entire set of dynamic stretches took approximately 3 minutes to complete. Control: Participants in this group were not exposed to any stretching exercises. | SJ (height); CMJ (height); Gymnastic jump (height); range of motion of coxo-femoral joint | A video-based mobile application was used to measure SJ, CMJ and gymnastic jump. The forward oversplit was applied for measuring range of motion. |

| Montalvo and Dorgo, 2020 | 11 | 23.18 ± 2.52 | Women and men | ND | SS; DS; SS+DS; DS+SS; Control (no stretching) | Both the dynamic and static stretching protocols comprised 15 exercises, requiring approximately 10-15 minutes for completion. The combined protocols, ST+DY and DY+ST, took between 20-25 minutes to finish, necessitating the completion of all exercises before proceeding to the subsequent testing session. | CMJ (height), SJ (height), depth jump (height) | Optical acquisition system for measuring CMJ, SJ and depth jump |

| Papia et al., 2018 | 19 | 9.8 ± 0.5 | Girls | Gymnastics for all | SS; Control (no stretching) | SS: Participants engaged in 90 seconds of uninterrupted static stretching specifically targeting the quadriceps muscle of one leg. Control: Participants in this group did not partake in any stretching exercises. |

Unilateral and bilateral CMJ (height); Hip and knee range of motion. | An electronic contact mat was employed to measure the CMJ. The hip joint range of motion was determined as the angle between the horizontal plane and the line connecting the markers placed on the hip and knee. |

| Sands et al., 2006 | 10 | 10.1 ± 1.5 | Boys | ND | SS; VP | SS: Athletes engaged in forward and rearward leg stretches, reaching the point of discomfort for 10 seconds, succeeded by a 5-second rest interval. This sequence was repeated four times on each leg and in a split position, resulting in a total duration of 4 minutes. VP: Mirroring the SS routine, participants replicated the same positions but incorporated vibration. |

Left and right forward split (height) | Forward split position with the rear leg flexed at the knee and the shank held vertically against a matted block |

| Sands et al., 2008 | 10 | 10.7 ± 0.99 | Boys | ND | SS; VP | SS: performed split positions over 45 seconds. VP: Mirroring the SS routine, participants replicated the same positions but incorporated vibration. | Left and right forward split (height) | Side split |

| Siatras et al., 2003 | 11 | 9.8 ± 0.8 | Boys | ND | SS; DS; control (traditional warm-up) | Control: Participants engaged in 5 minutes of general exercises, including jogging, jumping, and short sprints. SS: Similar to the control condition, participants performed the same general exercises but also included 2 static stretching exercises. Each static stretching position was held steadily for 30 seconds, reaching the point of limitation before the onset of pain. DS: In line with the control condition, participants followed the same general exercises but incorporated exercises similar to the SS condition. However, in dynamic stretching, participants swung their lower limbs in a dynamic fashion through their maximal range of motion as fast as possible for 30 seconds. | Running speed of gymnasts executing a "handspring" vault 0-15m | Four pair of photocells were used to measure the running speed at "handspring" vault |

| Siatras, 2014 | 14 | 20.9 ± 2.2 | Men | Artistic | SS; control (traditional warm-up) | SS: The static stretching routine extended over 60 seconds, including two conditions (a) synergist muscles focused on the thigh and trunk muscles, and (b) antagonist muscles. The end range of motion was maintained passively for 60 seconds in a single repetition, reaching the point of limitation before the onset of pain. Control: Participants in the control group engaged in 5 minutes of general exercises, including jogging, jumping, and various exercises without incorporating any stretching movements. |

Angle on V-sit exercise (legs horizontal, trunk-vertical and arms-vertical) | V-sit exercise executed on parallel bars |

| Zaggelidou et al., 2023 | 15 | 13.86 ± 1.03 | Girls | Rhythmic | SS; DS | SS: This routine comprised 14 exercises, each involving static stretching for a duration ranging between 10 and 15 seconds. The number of repetitions varied from 1 to 3, depending on the specific exercise. DS: Mirroring the exercises in the SS condition, the dynamic stretching routine incorporated the same 14 exercises. However, in the DS condition, participants executed 3 repetitions for each exercise, focusing on completing each repetition as swiftly as possible. |

Range of motion of hip flexion, knee flexion, and dorsiflexion; and distance of single hop, triple hop, crossover hop and 6-m hop tests. | Range of motion of hip flexion, knee flexion, and dorsiflexion of the ankle joint was evaluated using Myrin goniometer. Hope tests included single hop and triple hop for distance, cross-over hop and 6 meters in a given time |

| Van Zyl et al., 2011 | 52 | 8-10 | Girls | ND | SS; VB; Control (no warm-up) | SS: Participants engaged in a 10-minute session of static stretching, specifically in the forward split position. VP: Participants performed the forward split position on a VP. Control: Participants executed the forward split without any preceding warm-up. |

Forward split range of motion (cm) | Forward split |

Results of the individual studies

Table 3 describes the outcomes of individual studies that have specifically examined the impacts of various warm-up strategies on the jumping and technical execution performance of gymnasts. Table 4 showed the outcomes of individual studies that have specifically examined the impacts of various warm-up strategies on the muscle strength, range of motion and balance gymnastics elements.

Table 3.

Results of individual studies on jumping performance and technical execution of gymnastics elements

| Study | Variable | Control | SS | DS | VP | PNF | Comparison (%) | Comparison (p-value*) | Comparison (ES) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jumping performance | |||||||||

| Dallas et al., 2014b | SJ (cm) | N/A | 31.95 ± 8.77 | N/A | 31.15 ± 8.35 | 32.09 ± 7.73 | SSvsVP: -2.51% SSvsPNF: 0.44% VPvsPNF: 3.02% |

p > 0.05 p > 0.05 p > 0.05 |

-0.09 0.02 0.12 |

| Dallas et al., 2014a | SJ (cm) | N/A | 23.03 ± 4.71 | N/A | 24.37 ± 4.28 | N/A | SSvsVP: 5.82% | ND | 0.31 |

| Di Cagno et al., 2010 | SJ flight time (s) | 0.40 ± 0.24 | 0.40 ± 0.03 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: 0.00% | p > 0.05 | N/A |

| Kinser et al., 2008 | SJ (cm) | N/A | 18.5 ± 3.4 | N/A | 19.9 ± 3.5 | N/A | SSvsVP: 7.57% | ND | 0.46 |

| Melocchi et al., 2021 | SJ (cm) | 32.3 ± 2.91 | 32.4 ± 3.44 | 37.4 ± 5.72 | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: 0.31% CvsDS: 15.70% SSvsDS: 15.44% |

p > 0.99 p = 0.008 p = 0.005 |

0.04 1.01 0.95 |

| Montalvo and Dorgo, 2020 | SJ (cm) | 33.19 ± 5.06 | 35.47 ± 6.91 | 38.21 ± 5.85 | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: 6.87% CvsDS: 15.10% SSvsDS: 7.71% |

p = 0.18 p = 0.84 ND |

0.39 0.98 0.43 |

| Dallas et al., 2014b | CMJ (cm) | N/A | 33.11 ± 9.24 | N/A | 33.67 ± 8.67 | 32.86 ± 7.94 | SSvsVP: 1.68% SSvsPNF: -0.75% VPvsPNF: -2.41% |

p > 0.05 p > 0.05 p > 0.05 |

0.06 -0.03 -0.10 |

| Dallas et al., 2014a | CMJ (cm) | N/A | 24.16 ± 4.76 | N/A | 25.18 ± 4.16 | N/A | SSvsVP: 4.21% | ND | 0.24 |

| Kinser et al., 2008 | CMJ (cm) | N/A | 19.0 ± 2.7 | N/A | 22.0 ± 3.6 | N/A | SSvsVP: 15.79% | ND | 1.11 |

| Melocchi et al., 2021 | CMJ (cm) | 33.6 ± 3.03 | 33.4 ± 4.41 | 37.1 ± 4.66 | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -0.60% CvsDS: 9.23% SSvsDS: 10.78% |

p = 0.98 p = 0.010 p = 0.026 |

-0.05 1.28 1.04 |

| Montalvo and Dorgo, 2020 | CMJ (cm) | 35.93 ± 4.52 | 37.46 ± 6.00 | 40.85 ± 6.68 | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: 4.25% CvsDS: 13.67% SSvsDS: 8.86% |

p > 0.99 p = 0.03 ND |

0.33 1.02 0.56 |

| Papia et al., 2018 | CMJ (cm) | 16.9 ± 3.1 | 16.3 ± 3.4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -3.55% | p = 0.186 | -0.17 |

| Di Cagno et al., 2010 | CMJ flight time (s) | 0.45 ± 0.06 | 0.45 ± 0.03 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: 0.00% | p > 0.05 | N/A |

| McNeal and Sands, 2003 | DJ (s) | 0.466 ± 0.028 | 0.446 ± 0.047 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -4.29% | p<0.001 | -0.75 |

| Montalvo and Dorgo, 2020 | Depth jump (cm) | 31.85 ± 9.47 | 30.49 ± 7.56 | 33.53 ± 7.00 | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -4.27% CvsDS: 5.31% SSvsDS: 9.96% |

p = 0.18 p = 0.18 ND |

-0.15 0.21 0.43 |

| Papia et al., 2018 | One leg CMJ (cm) | 7.4 ± 1.7 | 6.9 ± 1.8 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -6.76% | p = 0.207 | -0.29 |

| Dallas et al., 2014a | SLSJ right (cm) | N/A | 12.27 ± 2.65 | N/A | 13.12 ± 3.14 | N/A | SSvsVP: 6.92% | ND | 0.30 |

| Dallas et al., 2014a | SLSJ left (cm) | N/A | 12.07 ± 3.20 | N/A | 12.87 ± 2.52 | N/A | SSvsVP: 6.64% | ND | 0.29 |

| Di Cagno et al., 2010 | Hooping flight time (s) | 0.48 ± 0.06 | 0.46 ± 0.04 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -4.17% | p > 0.05 | -0.50 |

| Zaggelidou et al., 2023 | Triple hop (cm) | N/A | 4.06 ± ND | 3.99 ± ND | N/A | N/A | SSvsDS: -1.73% | ND | N/A |

| Zaggelidou et al., 2023 | Crossover hop (s) | N/A | 25.65 ± ND | 24.25 ± ND | N/A | N/A | SSvsDS: -5.46% | ND | N/A |

| Zaggelidou et al., 2023 | Crossover hop (s) | N/A | 25.65 ± ND | 24.25 ± ND | N/A | N/A | SSvsDS: -5.46% | ND | N/A |

| Zaggelidou et al., 2023 | 6m hop (s) | N/A | 22.49 ± ND | 23.06 ± ND | N/A | N/A | SSvsDS: 2.53% | ND | N/A |

| Technical execution of gymnastics elements | |||||||||

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | Vault∴ test (score) | 6.44 ± 0.48 | N/A | 8.23 ± 0.50 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: 27.82 | p < 0.001 | 3.77 |

| Di Cagno et al., 2010 | Split leaps with leg stretched flight time (s) | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 0.42 ± 0.04 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -7.14% | p < 0.001 | -0.75 |

| Di Cagno et al., 2010 | Split leaps with ring flight time (s) | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 0.42 ± 0.05 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -7.14% | p < 0.001 | -0.75 |

| Di Cagno et al., 2010 | Split leaps with back bend trunk flight time (s) | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 0.43 ± 0.05 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -6.52% | p < 0.001 | -0.65 |

| Johnson et al., 2019 | Split jump@ (angle) | N/A | 165.3 ± 16.4 | N/A | N/A | 160.8 ± 16.7 | SSvsPNF: -2.74% | ND | -0.28 |

| Johnson et al., 2019 | Split jump@ height (cm) | N/A | 100 ± 11 | N/A | N/A | 101 ± 11 | SSvsPNF: 1.00% | p > 0.05 | 0.09 |

| Kinser et al., 2008 | Right forward-split$ (cm) | N/A | 19.0 ± 4.9 | N/A | 21.4 ± 7.0 | N/A | SSvsVP: 12.63% | ND | 0.34 |

| Kinser et al., 2008 | Left forward-split$ (cm) | N/A | 20.6 ± 5.6 | N/A | 22.6 ± 6.8 | N/A | SSvsVP: 9.71% | ND | 0.29 |

| McNeal et al., 2011 | Split dominant (angle) | N/A | 160.31 ± 0.56 | N/A | 167.12 ± 0.53 | N/A | SSvsVP: 4.23% | ND | 11.71 |

| McNeal et al., 2011 | Split non-dominant (angle) | N/A | 148.76 ± 0.32 | N/A | 160.52 ± 0.76 | N/A | SSvsVP: 7.88% | p < 0.05 | 37.04 |

| Melocchi et al., 2021 | Gymnastics jump (ms) | 744.9 ± 41.59 | 726.8 ± 41.06 | 745.3 ± 56.44 | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -2.43% CvsDS: 0.05% SSvsDS: 2.55% |

p = 0.43 p > 0.99 p = 0.053 |

-0.44 0.01 0.29 |

| Sands et al., 2006 | Right forward split$ (cm) | N/A | ¶ (mean dif: 1.1 cm) | N/A | ¶ (mean dif: 5.7 cm) | N/A | SSvsVP: N/A | ND | N/A |

| Sands et al., 2006 | Left forward split$ (cm) | N/A | ¶ (mean dif: 2.3 cm) | N/A | ¶ (mean dif: 7.4 cm) | N/A | SSvsVP: N/A | ND | N/A |

| Sands et al., 2008 | Forward split (cm) | N/A | 24.5 ± 5.0 | N/A | 20.8 ± 4.9 | N/A | SSvsVP: -14.98% | p < 0.001 | -0.75 |

| Siatras et al., 2003 | Running speed executing a "handspring" vaultδ (m/s) | 5.24 ± 0.46 | 5.07 ± 0.42 | 5.17 ± 0.42 | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -3.25% CvsDS: -1.34% SSvsDS: 1.96% |

p < 0.001 ND ND |

-0.37 -0.16 0.24 |

| Siatras, 2014 | Legs-horizontal on V-sit# (angle) | 38.8 ± 17.0 | 33.8 ± 16.0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -12.95% | p < 0.001 | -0.29 |

| Siatras, 2014 | Trunk-vertical on V-sit# (angle) | 25.3 ± 8.5 | 24.1 ± 8.3 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -4.74% | p > 0.05 | -0.14 |

| Siatras, 2014 | Arms-vertical on V-sit# (angle) | 16.4 ± 3.8 | 15.2 ± 3.2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -7.32% | p > 0.05 | -0.34 |

| Van Zyl et al., 2011 | Forward slit$ (cm) | 18.9 ± 7.60 | 17.9 ± 11.4 | N/A | 9.8 ± 6.20 | N/A | CvsSS: -5.56% CvsVP: -48.14% SSvsVP: -45.81% |

p = 0.006 p < 0.001 p < 0.001 |

-0.09 -1.48 -0.96 |

*p-value extracted from the original article; ES: effect size calculated using standardized Cohen d; %: percentage of difference between conditions; CMJ: countermovement jump; SJ: squat jump; SLSJ: single leg squat jump; DJ: drop jump; SS: static stretching; DS: dynamic stretching; VP: vibration platform; PNF: proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation; N/A: not applicable; ND: not described

¶: the study only provided mean difference between for pre-post differences

#V-sit: static hold where the body forms a V shape by extending the legs straight in front and lifting the upper body to create a straight line from the hands to the toes while balancing on the buttocks

$forward split: involves extending one leg forward and the other backward while keeping both legs straight, creating a line parallel to the ground with the torso positioned between the legs

@split jump: dynamic movement where a gymnast leaps into the air, extending both legs to the sides in a split position, and then lands with one foot in front and the other behind while maintaining the split position

∴vault: refers to an apparatus used for a dynamic event where gymnasts sprint down a runway, propel themselves off a springboard onto the vaulting table, and execute various maneuvers before landing on the mat

δhandspring vault: involves a gymnast running down the runway, placing their hands on the vaulting table, performing a handspring by pushing off with their hands and propelling their body over the vault, and then executing a variety of twists or flips before landing on the mat.

Table 4.

Results of individual studies on muscle strength, flexibility, balance and running.

| Study | Variable | Control (C) | SS | DS | VP | PNF | Comparison (%) | Comparison (p-value*) | Comparison (ES) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | SDEO COPEAP (mm) | 6.56 ± 3.51 | N/A | 5.20 ± 1.58 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: -20.73% | p > 0.05 | -0.36 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | SDEO COPEML (mm) | 6.94 ± 5.83 | N/A | 5.45 ± 2.68 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: -21.61% | p > 0.05 | -0.24 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | SDEO PLAP (mm) | 32.11 ± 5.08 | N/A | 24.38 ± 9.48 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: -24.00% | p > 0.05 | -0.81 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | SDEO PLML (mm) | 35.05 ± 29.76 | N/A | 25.62 ± 14.29 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: -27.07% | p > 0.05 | -0.66 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | SSEO COPEAP (mm) | 6.51 ± 1.23 | N/A | 6.64 ± 2.15 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: 2.00% | p > 0.05 | 0.11 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | SSEO COPEML (mm) | 7.03 ± 0.99 | N/A | 8.21 ± 4.01 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: 16.80% | p > 0.05 | 0.42 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | SSEO PLAP (mm) | 30.06 ± 8.87 | N/A | 30.73 ± 10.35 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: 2.23% | p > 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | SSEO PLML (mm) | 55.27 ± 24.26 | N/A | 48.69 ± 39.44 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: -11.86% | p > 0.05 | -0.24 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | DDEO COPEAP (mm) | 6.84 ± 1.89 | N/A | 6.68 ± 1.77 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: -2.34% | p > 0.05 | -0.13 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | DDEO COPEML (mm) | 6.52 ± 1.68 | N/A | 6.07 ± 1.62 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: -6.90% | p > 0.05 | -0.28 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | DDEO PLAP (mm) | 30.39 ± 8.03 | N/A | 28.98 ± 7.42 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: -4.63% | p > 0.05 | -0.18 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | DDEO PLML (mm) | 33.21 ± 8.77 | N/A | 28.25 ± 7.98 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: -14.96% | p > 0.05 | -0.57 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | DSEO COPEAP (mm) | 6.72 ± 1.17 | N/A | 7.26 ± 2.55 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: 8.04% | p > 0.05 | 0.23 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | DSEO COPEML (mm) | 8.03 ± 1.19 | N/A | 8.34 ± 3.75 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: 3.87% | p > 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | DSEO PLAP (mm) | 31.56 ± 5.47 | N/A | 34.04 ± 13.44 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: 7.85% | p > 0.05 | 0.22 |

| Ahmadabadi et al., 2015 | DSEO PLML (mm) | 40.93 ± 7.62 | N/A | 41.45 ± 21.12 | N/A | N/A | CvsDS: 1.27% | p > 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Dallas et al., 2014b | Sit and reach (cm) | N/A | 39.00 ± 4.85 | N/A | 36.77±6.26 | 39.44±4.55 | SSvsVP: -5.72% SSvsPNF: 1.13% VPvsPNF: 7.28% |

p > 0.05 p > 0.05 p = 0.002 |

-0.45 0.09 0.43 |

| Dallas et al., 2014a | Sit and reach (cm) | N/A | 30.23 ± 6.67 | N/A | 31.11±5.27 | N/A | SSvsVP: 2.91% | ND | 0.14 |

| Papia et al., 2018 | Hip range of motion (angle) | 16.3 ± 3.7 | 18.2 ± 4.2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: 11.66% | p = 0.002 | 0.48 |

| Papia et al., 2018 | Knee range of motion (angle) | 26.6 ± 2.7 | 25.9 ± 3.0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | CvsSS: -2.63% | p = 0.218 | -0.26 |

| Zaggelidou et al., 2023 | Bicep range of motion (angle) | N/A | 133.21 ± ND | 144.50 ± ND | N/A | N/A | SSvsDS: 8.48% | p < 0.001 | N/A |

| Zaggelidou et al., 2023 | Quadricep range of motion (angle) | N/A | 156.29 ± ND | 158.21 ± ND | N/A | N/A | SSvsDS: 1.23% | ND | N/A |

| Zaggelidou et al., 2023 | Ankle range of motion (angle) | N/A | 42.14 ± ND | 43.50 ± ND | N/A | N/A | SSvsDS: 3.23% | ND | N/A |

| Dallas et al., 2021 | Contact time (ms) | 0.207 ± 0.01 | N/A | 0.207 ± 0.01 | N/A | 0.202 ± 0.01 | CvsDS: 0.00% CvsPNF: -2.42% DSvsPNF: -2.42% |

ND ND ND |

N/A -0.51 -0.51 |

| Dallas et al., 2021 | Flight time (s) | 0.111 ± 0.02 | N/A | 0.113 ± 0.02 | N/A | 0.109±0.02 | CvsDS: 1.80% CvsPNF: -1.80% DSvsPNF: -3.54% |

ND ND ND |

0.10 -0.10 -0.20 |

| Dallas et al., 2021 | Step rate (Hz) | 3.141 ± 0.18 | N/A | 3.121 ± 0.17 | N/A | 3.220±0.22 | CvsDS: -0.64% CvsPNF: 2.52% DSvsPNF: 3.17% |

ND ND ND |

-0.11 0.44 0.55 |

| Dallas et al., 2021 | Step length (hz) | 1.418 ± 0.08 | N/A | 1.420 ± 0.07 | N/A | 1.385±0.09 | CvsDS: 0.14% CvsPNF: -2.32% DSvsPNF: -2.46% |

ND ND ND |

0.19 -0.39 -0.42 |

| Dallas et al., 2021 | Change in leg length (m) | 0.182 ± 0.01 | N/A | 0.183 ± 0.01 | N/A | 0.173±0.02 | CvsDS: 0.55% CvsPNF: -4.95% DSvsPNF: -5.46% |

ND ND ND |

0.17 -0.45 -0.50 |

| Dallas et al., 2021 | Vertical displacement of the center of mass (m) | 0.0506 ± 0.01 | N/A | 0.0512 ± 0.01 | N/A | 0.0484±0.01 | CvsDS: 1.19% CvsPNF: -4.36% DSvsPNF: -5.47% |

ND ND ND |

0.07 -0.28 -0.33 |

| Dallas et al., 2021 | Leg stiffness (km/m) | 7.51 ± 1.34 | N/A | 7.51 ± 1.34 | N/A | 7.90±1.47 | CvsDS: 0.00% CvsPNF: 5.19% DSvsPNF: 5.19% |

ND ND ND |

N/A 0.28 0.28 |

| Dallas et al., 2021 | Vertical stiffness (km/m) | 27.016 ± 3.34 | N/A | 27.016 ± 3.34 | N/A | 28.427±4.13 | CvsDS: 0.00% CvsPNF: 5.22% DSvsPNF: 5.22% |

ND ND ND |

N/A 0.35 0.35 |

| Dallas et al., 2021 | Maximal ground reaction force | 1.357±0.17 | N/A | 1.357±0.17 | N/A | 1.356±0.17 | CvsDS: 0.00% CvsPNF: -0.07% DSvsPNF: -0.07% |

ND ND ND |

N/A -0.01 -0.01 |

| Manso et al., 2015 | Maximum radial deformation or displacement of the muscle belly | N/A | 39.72±9.00 | N/A | 38.83±10.74 | N/A | SSvsVP: -2.24% | ND | -0.10 |

| Manso et al., 2015 | Speed of response at 3 mm deformation | N/A | 8.69±2.58 | N/A | 8.79±2.44 | N/A | SSvsVP: 1.15% | ND | 0.04 |

| Manso et al., 2015 | Length of time for which the contraction was maintained | N/A | 132.6±20.48 | N/A | 134.25±19.03 | N/A | SSvsVP: 1.22% | ND | 0.07 |

| Manso et al., 2015 | relaxation time | N/A | 59.31±15.68 | N/A | 56.48±20.71 | N/A | SSvsVP: -4.76% | ND | -0.15 |

*p-value extracted from the original article; ES: effect size calculated using standardized Cohen d; %: percentage of difference between conditions; SDEO: Static Double Eyes Open; SSEO: Static Single Eyes Open; DDEO: Dynamic Double Eyes Open; DSEO: Dynamic Single Eyes Open; N/A: Not applicable; SS: static stretching; DS: dynamic stretching; VP: vibration platform; PNF: proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation; ND: not described

Meta-analysis

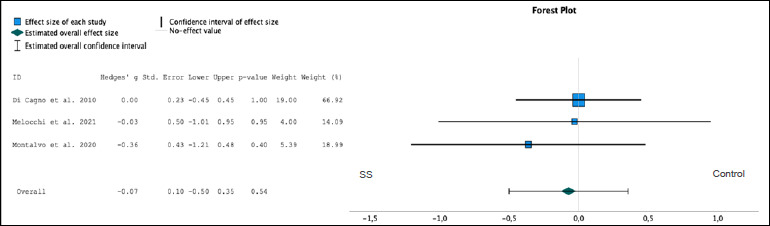

Results showed a non-significant difference between the SS condition and control conditions in squat jump (SJ) performance (Figure 3: ES = -0.073, 95% CI = -0.500; 0.354, p = 0.539, I2 = 0.00%, Egger test two-tailed = 0.585). Similarly, non-significant difference between the VP condition and SS conditions regarding SJ performance were found (Figure 4: ES = 0.159, 95% CI = -0.482; 0.799, p = 0.398, I2 = 0.00%, Egger test two-tailed = 0.422).

Figure 3.

Forest plot comparing performance in squat jumps under control and static stretching (SS) conditions.

Figure 4.

Forest plot comparing performance in squat jumps under vibration platform (VP) and static stretching (SS) conditions.

Non-significant difference between the SS condition and control conditions in countermovement jump (CMJ) performance were found (Figure 5: ES = 0.012, 95% CI = -0.262; 0.286, p = 0.896, I2 = 0.00%, Egger test two-tailed = 0.685) as well as non-significant difference between the VP condition and SS conditions regarding CMJ performance (Figure 6: ES = 0.298, 95% CI = -0.638; 1.234, p = 0.304, I2 = 0.10%, Egger test two-tailed = 0.011).

Figure 5.

Forest plot comparing performance in countermovement jumps under control and static stretching (SS) conditions.

Figure 6.

Forest plot comparing performance in countermovement jumps under vibration platform (VP) and static stretching (SS) conditions.

Non-significant difference between the SS condition and control conditions in gymnastic technical performance were found (Figure 7: ES = 0.428, 95% CI = -0.427; 1.283, p = 0.164, I2 = 19.8%, Egger test two-tailed = 0.345). Non-significant difference between the VP condition and SS conditions regarding gymnastic technical performance were observed (Figure 8: ES = -0.378, 95% CI = -1.983; 1.226, p = 0.417, I2 = 52.7%, Egger test two-tailed = 0.643).

Figure 7.

Forest plot comparing performance in gymnastics technical elements under control and static stretching (SS) conditions.

Figure 8.

Forest plot comparing performance in gymnastics technical elements under vibration platform (VP) and static stretching (SS) conditions.

Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis examined the influence of various warm-up strategies on the immediate performance of gymnasts. In addition to summarize the studies’ outcomes that provided additional information and facilitated comparisons, the meta-analysis for cases with a sufficient number of studies showed no significant differences between SS, vibration platforms (VP), or control conditions in SJ, CMJ, or the technical execution of gymnastics elements.

Several studies in gymnastics, including those by Melocchi et al. (2021), Montalvo and Dorgo (2020), and Di Cagno et al. (2010), have explored the contrasting effects of SS versus traditional warm-ups, specifically focusing on physical and technical performance. Moreover, numerous studies have examined SS characterized by prolonged muscle elongation (McNeal and Sands, 2003; Melocchi et al., 2021). While some studies indicate potential benefits, such as increased range of motion (Melocchi et al., 2021), others suggest that SS may lead to a transient decrease in muscle power (McNeal and Sands, 2003). Interestingly, a meta-analysis exploring the effects of SS on SJ and CMJ revealed that impairment levels depend on the duration of the static stretch (Simic et al., 2013).

Conversely, our results suggest that SS enhances specific gymnastics elements to a moderate but non-significant extent compared to control conditions. Siatras, (2014) showed that the angle reached in legs-horizontal during the V-sit (an exercise in which the gymnast sits with their legs extended and torso lifted off the ground, forming a V shape with the body) was significantly better after SS than after the control condition. Additionally, Van Zyl et al. (2011) reported that the range of motion in a forward split was significantly improved after SS compared to control conditions.

Conversely, for ballistic elements such as split leaps with the leg stretched, the flight time was significantly greater in the control condition than in the SS condition (Di Cagno et al., 2010). Similarly, other research showed that the running speed on the handspring vault was significantly higher in the control condition than in the SS condition (Siatras et al., 2003). Scientific evidence supports the immediate benefits of SS for gymnasts while considering static elements (flexibility), enhancing range of motion and flexibility. Kataura et al. (2017) showed that engaging in SS at a high intensity augments one’s range of motion and reduces passive muscle-tendon stiffness. However, caution is warranted, as SS may induce temporary decreases in ballistic technical elements, which are crucial to gymnastics performance. SS also temporarily decreases muscle stiffness, affecting the muscles’ ability to rapidly generate force due to a decrease of voluntary activation and persistent inward current effects on motoneuron excitability (Behm et al., 2021).

The included studies also often compared SS with the same stretching exercises performed on VP (Kinser et al., 2008; McNeal et al., 2011; Dallas et al., 2014a). VP devices, also known as whole-body vibration (WBV) devices, are intended to complement SS by utilizing mechanical vibrations to stimulate muscle activity and enhance neuromuscular function (Luo et al., 2005). These devices are designed to induce rapid muscle contractions, thereby improving muscle activation and neuromuscular facilitation (Cochrane, 2011). The reflexive responses triggered by the vibrations may also increase strength and power (Alam et al., 2018), helping gymnasts achieve precise coordination and control during their routines (Zasada et al., 2016).

This meta-analysis comparing SS with VP revealed no significant differences in performance outcomes. Specifically, for SJ, both conditions exhibited similar effects in the studies of Dallas et al. (2014b) and Dallas et al. (2014a). Moreover, regarding the forward split, Sands et al. (2008) and Zyl et al. (2011) demonstrated significant benefits of VP. Conversely, Kinser et al. (2008) revealed that the use of VP reduced the range of motion in the forward split compared to SS by 9-12%.

Two studies have hinted at potential benefits on specific gymnastic elements such as the forward split after VP (Sands et al., 2008; Van Zyl et al., 2011). These observations align with a previous research demonstrating that acute exposure to vibration can enhance flexibility (Đorđević et al., 2022). This improvement can be attributed to a muscle extensibility enhancement and a reduced muscle stiffness (Fowler et al., 2019). The mechanism underlying this effect is associated with VP’s ability to induce muscle activity reflex (e.g., tonic vibration reflex, bone myoregulation reflex) (Cidem et al., 2017), thereby enhancing neuromuscular control and increasing the joint range of motion.

Though several studies included in this review lacked the necessary data for a meta-analysis, they examined the impact of DS versus SS on gymnastic performance. Melocchi et al. (2021) found that compared to SS, DS significantly increased SJ and CMJ performance by 15.4% and 10.8%, respectively. Similarly, Montalvo et al. (2020) demonstrated significant benefits of DS, showing an 8.86% improvement in CMJ performance compared to SS. The potential increases in muscle force and/or shortening velocity, possibly prompted by fluid shifts into the working muscles, could enhance muscle function in a fiber-type-specific manner. Concurrently, alterations in neural circuitry, such as changes in H reflex, motor-evoked potentials, and cortico-medullary evoked potential amplitudes, suggest that PAPE is a contributing factor to the observed positive effects (Blazevich and Babault, 2019). In the context of squat and counter-movement, DS primes the neuromuscular system, enhancing the recruitment of motor units and optimizing force generation.

Non-statistically significant values were reported by Melocchi et al. (2021), revealing that DS exhibited a 2.55% greater improvement in specific gymnastic jumps compared to SS. Similarly, the 1.96% increase of running speed in the handspring vault reported after DS reported by Siatras et al. (2003) did not reach statistical significance. However, Zaggelidou et al. (2023) showed a significant 8.48% enhancement in bicep range of motion after DS compared to SS.

Melocchi et al. (2021) evaluated the hip joint range of motion and found no significant difference between SS and DS. While DS involves movement through a range of motion and SS involves holding a position, both modalities have been shown to increase flexibility in comparison to control conditions. The theoretical reasons supporting their comparable effects are related to the commonality of their underlying mechanisms, such as alterations in muscle and tendon compliance, increased stretch tolerance, and neurophysiological adaptations (Behm and Chaouachi, 2011). Furthermore, both DS and SS can promote the viscoelastic properties of the muscles and tendons, thereby improving one’s range of motion (Kubo et al., 2002).

Current research on warm-up protocols for gymnasts reveals several limitations that hinder a comprehensive understanding of their impacts on performance. One limitation is related to the different methodologies employed in the studies. For instance, analyses of stretching warm-ups often overlook the effects of varying stretching durations and their potential impacts on impairments or enhancements, as well as the duration of these effects (i.e., the post-warm-up period). Hence, certain methodological aspects may constrain some of our results. Additionally, most research has concentrated on short-term performance outcomes while overlooking the potential long-term effects of warm-up routines on skill acquisition.

Methodological differences in measuring performance outcomes, such as objective biomechanical measures and surrogates (a variable measurable in lieu of one that cannot be assessed through gold-standard methods), further complicate data interpretation. Future research should include longitudinal studies that assess the cumulative effects of warm-up routines on skill development. Finally, utilizing advanced technologies, such as motion capture and wearable sensors, can provide more accurate and objective measurements of performance outcomes.

Conclusion

The current systematic review with meta-analysis revealed no significant differences in the extent to which SS, DS, VP, and control conditions enhanced jumping performance or technical execution in gymnastics. However, several studies suggest that SS slightly outperforms DS in improving technical executions related to static range of motion (e.g., forward split). However, DS appears to enhance jumping performance to a greater extent than SS. These findings suggest that DS is a preferred warm-up strategy in acute settings, especially when performed in close proximity to the gymnastic performance. Meanwhile, SS could be a more favorable warm-up strategy for events involving static movements and range of motion. Due to the heterogeneity of the findings, caution is advised when applying the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis; the warm-up process should be individualized.

Acknowledgements

There is no conflict of interest. The present study complies with the current laws of the country in which it was performed. The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author, who was an organizer of the study.

Biographies

Wenlu YU

Employment

College of Physical Education, Chengdu University

Degree

MEd

Research interests

Gymnastic teaching and training

E-mail: yuwenlu@cdu.edu.cn

DeSen FENG

Employment

ChengDu Sports University

Degree

PhD Student

Research interests

Gymnastic teaching and training

E-mail: fengdesen@cdsu.edu.cn

Ya ZHONG

Employment

The Affiliated Elementary School of Chengdu University

Degree

MEd

Research interests

Education,Training

E-mail: 1003528865@qq.com

Xiaohong LUO

Employment

College of Physical Education, Chengdu University

Degree

PhD

Research interests

Physical Education teaching and training

E-mail: 287503194@qq.com

Qi XU

Employment

Gdansk University of Physical Education and Sport

Degree

PhD

Research interests

Physical Education teaching and training

E-mail: qi.xu@awf.gda.pl

Jiaxiang YU

Employment

College of Pharmacy,Southwest Medical University

Degree

BMS Student

Research interests

Medical Science,Education

E-mail: yujiaxiang0914@qq.com

References

- Ahmadabadi F., Avandi S.M., Aminian-Far A. (2015) Acute versus chronic dynamic warm-up on balance and balance the vault performance in skilled gymnast. International Journal of Applied Exercise Physiology 4, 20-33. [Google Scholar]

- Alam M.M., Khan A.A., Farooq M. (2018) Effect of whole-body vibration on neuromuscular performance: A literature review. Work 59, 571-583. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-182699 10.3233/WOR-182699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behm D.G., Chaouachi A. (2011) A review of the acute effects of static and dynamic stretching on performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology 111, 2633-2651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-011-1879-2 10.1007/s00421-011-1879-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behm D.G., Kay A.D., Trajano G.S., Blazevich A.J. (2021) Mechanisms underlying performance impairments following prolonged static stretching without a comprehensive warm-up. European Journal of Applied Physiology 121, 67-94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-020-04538-8 10.1007/s00421-020-04538-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop D. (2003) Warm Up I: potential mechanisms and the effects of passive warm up on exercise performance. Sports Medicine 33, 439-454. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200333060-00005 10.2165/00007256-200333060-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazevich A.J., Babault N. (2019) Post-activation potentiation versus post-activation performance enhancement in humans: historical perspective, underlying mechanisms, and current issues. Frontiers in Physiology 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.01359 10.3389/fphys.2019.01359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cagno A., Baldari C., Battaglia C., Gallotta M.C., Videira M., Piazza M., Guidetti L. (2010) Preexercise Static Stretching Effect on Leaping Performance in Elite Rhythmic Gymnasts. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 24, 1995-2000. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e34811 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e34811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaabene H., Behm D.G., Negra Y., Granacher U. (2019) Acute Effects of Static Stretching on Muscle Strength and Power: An Attempt to Clarify Previous Caveats. Frontiers in Physiology 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.01468 10.3389/fphys.2019.01468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cidem M., Karacan I., Cakar H.I., Cidem M., Sebik O., Yilmaz G., Turker K.S., Karamehmetoglu S.S. (2017) Vibration parameters affecting vibration-induced reflex muscle activity. Somatosensory & Motor Research 34, 47-51. https://doi.org/10.1080/08990220.2017.1281115 10.1080/08990220.2017.1281115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane D.J. (2011) Vibration Exercise: The Potential Benefits. International Journal of Sports Medicine 32, 75-99. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1268010 10.1055/s-0030-1268010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas G., Kirialanis P., Mellos V. (2014a) The acute effect of whole body vibration training on flexibility and explosive strength of young gymnasts. Biology of Sport 31, 233-237. https://doi.org/10.5604/20831862.1111852 10.5604/20831862.1111852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas G., Mavvidis A., Kosmadaki I., Tsoumani S., Dallas K. (2019) The post activation potentiation effect of two different conditioning stimuli on drop jump parameters on young female artistic gymnasts. Science of Gymnastics Journal 11, 103-113. https://doi.org/10.52165/sgj.11.1.103-113 10.52165/sgj.11.1.103-113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas G., Pappas P., Dallas C. f, Paradisis G. (2021) Acute effects of dynamic and pnf stretching on leg and vertical stiffness on female gymnasts. Science of Gymnastics Journal 13, 263-273. https://doi.org/10.52165/sgj.13.2.263-273 10.52165/sgj.13.2.263-273 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas G., Smirniotou A., Tsiganos G., Tsopani D., Di Cagno A., Tsolakis C. (2014b) Acute effect of different stretching methods on flexibility and jumping performance in competitive artistic gymnasts. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 54, 683-690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks J.J., Higgins J.P., Altman D.G. (2008) Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Eds: Higgins J.P., Green S. The Cochrane Collaboration. 243-296. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470712184.ch9 10.1002/9780470712184.ch9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Đorđević D., Paunović M., Čular D., Vlahović T., Franić M., Sajković D., Petrović T., Sporiš G. (2022) Whole-Body Vibration Effects on Flexibility in Artistic Gymnastics - A Systematic Review. Medicina 58, 595. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58050595 10.3390/medicina58050595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs S.H., Black N. (1998) The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 52, 377-384. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.52.6.377 10.1136/jech.52.6.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler B.D., Palombo K.T.M., Feland J.B., Blotter J.D. (2019) Effects of Whole-Body Vibration on Flexibility and Stiffness: A Literature Review. International Journal of Exercise Science 12, 735-747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidetti L., Cagno A., Di, Gallotta M.C., Battaglia C., Piazza M., Baldari C. (2009) Precompetition Warm-up in Elite and Subelite Rhythmic Gymnastics. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 23, 1877-1882. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b3e04e 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b3e04e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson M., Docherty D., Robbins D. (2005) Post-Activation Potentiation. Sports Medicine 35, 585-595. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200535070-00004 10.2165/00007256-200535070-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins W.G., Marshall S.W., Batterham A.M., Hanin J. (2009) Progressive Statistics for Studies in Sports Medicine and Exercise Science. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 41, 3-13. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cb278 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818cb278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A.W., Warcup C.N., Seeley M.K., Eggett D., Feland J.B. (2019) The acute effects of stretching with vibration on dynamic flexibility in young female gymnasts. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 59. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.18.08290-7 10.23736/S0022-4707.18.08290-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadlec D., Sainani K.L., Nimphius S. (2023) With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility: Common Errors in Meta-Analyses and Meta-Regressions in Strength & Conditioning Research. Sports Medicine 53, 313-325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01766-0 10.1007/s40279-022-01766-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataura S., Suzuki S., Matsuo S., Hatano G., Iwata M., Yokoi K., Tsuchida W., Banno Y., Asai Y. (2017) Acute Effects of the Different Intensity of Static Stretching on Flexibility and Isometric Muscle Force. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 31, 3403-3410. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001752 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser A.M., Ramsey M.W., O’bryant H.S., Ayres C.A., Sands W.A., Stone M.H. (2008) Vibration and Stretching Effects on Flexibility and Explosive Strength in Young Gymnasts. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 40, 133-140. https://doi.org/10.1249/mss.0b013e3181586b13 10.1249/mss.0b013e3181586b13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontopantelis E., Springate D.A., Reeves D. (2013) A Re-Analysis of the Cochrane Library Data: The Dangers of Unobserved Heterogeneity in Meta-Analyses. PLoS ONE 8, e69930. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0069930 10.1371/journal.pone.0069930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo K., Kanehisa H., Fukunaga T. (2002) Effect of stretching training on the viscoelastic properties of human tendon structures in vivo. Journal of Applied Physiology 92, 595-601. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00658.2001 10.1152/japplphysiol.00658.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J., McNamara B., Moran K. (2005) The Use of Vibration Training to Enhance Muscle Strength and Power. Sports Medicine 35, 23-41. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200535010-00003 10.2165/00007256-200535010-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manso J.M.G., Bedoya J.L., Matoso D.R., Vargas L.A., Ruiz D.R., Santana M. V. (2015) Static-stretching vs. contract-relax-proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation stretching: study the effect on muscle response using tensiomyography. European Journal of Human Movement 34, 96-108. [Google Scholar]