Abstract

Objective

Despite cardiotoxicity overlap, the trastuzumab/pertuzumab and anthracycline combination remains crucial due to significant benefits. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD), a less cardiotoxic anthracycline, was evaluated for efficacy and cardiac safety when combined with cyclophosphamide and followed by taxanes with trastuzumab/pertuzumab in human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-positive early breast cancer (BC).

Methods

In this multicenter, phase II study, patients with confirmed HER2-positive early BC received four cycles of PLD (30−35 mg/m2) and cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2), followed by four cycles of taxanes (docetaxel, 90−100 mg/m2 or nab-paclitaxel, 260 mg/m2), concomitant with eight cycles of trastuzumab (8 mg/kg loading dose, then 6 mg/kg) and pertuzumab (840 mg loading dose, then 420 mg) every 3 weeks. The primary endpoint was total pathological complete response (tpCR, ypT0/is ypN0). Secondary endpoints included breast pCR (bpCR), objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate, rate of breast-conserving surgery (BCS), and safety (with a focus on cardiotoxicity).

Results

Between May 27, 2020 and May 11, 2022, 78 patients were treated with surgery, 42 (53.8%) of whom had BCS. After neoadjuvant therapy, 47 [60.3%, 95% confidence interval (95% CI), 48.5%−71.2%] patients achieved tpCR, and 49 (62.8%) achieved bpCR. ORRs were 76.9% (95% CI, 66.0%−85.7%) and 93.6% (95% CI, 85.7%−97.9%) after 4-cycle and 8-cycle neoadjuvant therapy, respectively. Nine (11.5%) patients experienced asymptomatic left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) reductions of ≥10% from baseline, all with a minimum value of >55%. No treatment-related abnormal cardiac function changes were observed in mean N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP), troponin I, or high-sensitivity troponin.

Conclusions

This dual HER2-blockade with sequential polychemotherapy showed promising activity with rapid tumor regression in HER2-positive BC. Importantly, this regimen showed an acceptable safety profile, especially a low risk of cardiac events, suggesting it as an attractive treatment approach with a favorable risk-benefit balance.

Keywords: Breast cancer, HER2-positive breast cancer, dual HER2 blockade, neoadjuvant therapy, sequential therapy

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide, with an estimated 2.3 million new cases in 2020 (1). Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-positive BC is an aggressive subtype (2), accounting for 15%−20% of all BCs (3). HER2-positive BC, known for its aggressive behavior, typically has worse outcomes and higher mortality rates than other subtypes (4,5). Despite the success of current HER2 therapies in BC, both de novo and acquired resistance occur, especially in metastatic cases (6). Therefore, successful therapy for this disease remains challenging.

In recent decades, neoadjuvant therapy has become a preferred option in HER2-positive BC because pathological complete response (pCR) correlates with outcome (7). In the pivotal NeoSphere trial, adding pertuzumab to trastuzumab-based chemotherapy nearly doubled the pCR rate (from 29% to 46%) in this disease (8,9). According to these data, polychemotherapy with dual HER2 blockade is the standard neoadjuvant care for HER2-positive BC (10).

Nevertheless, recent studies have shown that combining trastuzumab with conventional anthracyclines, particularly doxorubicin, is not recommended due to overlapping cardiotoxicity (11,12), as reported by Slamon et al., with this regimen causing more cardiac dysfunction than anthracyclines alone (27% vs. 8%) (13). On the contrary, several studies suggest that trastuzumab with anthracyclines may be safe (14-16). Additionally, based on the 2021 St. Gallen/Vienna panel discussion, anthracyclines are still needed for node-positive disease (17). Despite the significant benefit of anthracyclines in HER2-positive BC, clinicians are reluctant to omit them from treatment regimens (18,19). The optimal chemotherapy backbone for dual HER2-blockade is still unknown regarding efficacy and toxicity (20).

To minimize cardiotoxicity, researchers are investigating novel neoadjuvant regimens by optimizing administration and using alternative agents, such as sequential instead of concomitant therapy (21-23) or liposomal anthracyclines [e.g., nonpegylated or pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (NPLD/PLD)] (14,24). The large clinical trial BCIRG-006 confirmed the encouraging outcomes of sequential therapy in reducing the risk of cardiotoxicity, with only a 2% incidence of congestive heart failure (25). Meanwhile, there is strong recent evidence that early HER2-blockade improves tumor control (26). Additionally, liposomal anthracyclines have demonstrated similar efficacy and reduced toxicity compared to conventional anthracyclines (27,28). Based on this robust evidence, developing safer sequential therapy with liposomal doxorubicin and full-course HER2-blockade seemed preferable. An early-stage study showed that PLD/cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel and trastuzumab is feasible and safe, but the data are from limited cases and the 30% breast pCR (ypT0/is) rate is unsatisfactory (21). Thus, there is much room for improvement.

To improve pathological response, we evaluated the activity and safety of sequential neoadjuvant chemotherapy with PLD/cyclophosphamide followed by taxanes and full-course trastuzumab/pertuzumab for HER2-positive BC.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

This study was an investigator-initiated, single-arm, open-label, multicenter, phase II trial assessing the efficacy and safety of sequential chemotherapy plus dual HER2 blockade as neoadjuvant therapy in HER2-positive BC patients. Patients were recruited from Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, Shenzhen Qianhai Shekou Free Trade Zone Hospital and Guilin Medical College Second Affiliated Hospital in China. This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University (No. 2019-KY-062-004), and all participants provided written informed consent before study procedures. This study was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trials Registry (https://www.chictr.org.cn/), ChiCTR1900028433.

Female patients aged 18−70 years with histologically or cytologically confirmed HER2-positive BC were eligible for enrollment. HER2-positive was defined as an immunohistochemistry (IHC) score of 3+ or a fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) score of 2+ if confirmed by FISH positivity, following American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists (ASCO/CAP) guidelines (29). The inclusion criteria included patients with treatment-naïve, invasive, unilateral BC and primary tumors >2 cm or positive lymph nodes. Other inclusion criteria included at least one measurable lesion as per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1, baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0−2, baseline left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of ≥55%, and adequate organ function. The exclusion criteria included metastatic BC (stage IV), inflammatory BC, other malignancies, uncontrolled diabetes, impaired cardiac function, and pregnant or lactating patients at screening. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Supplementary Table S1.

Table S1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Variables | Criteria |

| HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2; IHC, immunohistochemistry; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-BNP; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ULN, upper limit of normal; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; ECG, electrocardiograph; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus. | |

| Inclusion criteria | 1. Female patients aged from 18 to 70 years old; 2. Histologically confirmed as unilateral primary breast cancer and without previous treatment. Occult breast cancer, inflammatory breast cancer and eczematoid carcinoma are ineligible; 3. HER2 positive (defined by IHC 3+ or IHC 2+ and fluorescence in situ hybridization-positive); 4. Tumor ≥2 cm or lymph node-positive; 5. Patients must have at least one measurable disease according to RECIST 1.1; 6. ECOG performance score ≤2 points; 7. LVEF≥55%; 8. BNP or NT-proBNP and cardiac troponin are normal; 9. ALT, AST, ALP, and serum total bilirubin are all ≤2 ULN; serum creatinine ≤1.5 ULN; 10. Bone marrow function: white blood cell count ≥3.0×109/L; ANC≥1.5×109/L; platelets ≥100×109/L; hemoglobin ≥90 g/L; 11. Ability to understand and voluntarily receive the research procedures according to protocol, willingness to sign the written informed consent document. |

| Exclusion criteria | 1. Stage IV (metastatic) breast cancer; 2. Known or suspected hypersusceptibility to any agents used in the treatment protocol; 3. Need to concurrent treatment with any other anti-cancer therapy considered by the investigator; 4. Patients with severe cardiac disease or discomfort who are expected to be unable to tolerate chemotherapy, including but not limited to e.g., fatal arrhythmia or higher grade atrioventricular block [second-degree type II (Mobitz 2) or third-degree atrioventricular block], unstable angina pectoris, clinical significance valvular disease, transmural myocardial infarction measured by ECG, uncontrolled hypertension; 5. Patients with uncontrolled diabetes; 6. Severe or uncontrolled infections that may affect study treatment or evaluation, including but not limited to active hepatitis virus infection, HIV antibody positive, lung infection, etc.; 7. A history of other malignancies within the previous 5 years, except for adequately treated carcinoma in situ of the cervix or basal cell carcinoma of the skin; 8. Participation in other clinical trials within 4 weeks before enrollment; 9. Women who are pregnant, breastfeeding, or refuse to use adequate contraception prior to study entry and for the duration of study participation; 10. Other conditions considered to be inappropriate to be enrolled by the investigator. |

Procedures

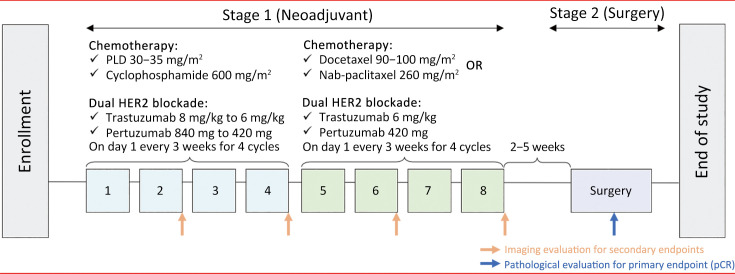

All eligible patients received four cycles of PLD (30−35 mg/m2; CSPC Ouyi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shijiazhuang, China), cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2), trastuzumab (initial 8 mg/kg, then 6 mg/kg), and pertuzumab (initial 840 mg, then 420 mg), followed by four cycles of taxanes (docetaxel, 90−100 mg/m2 or nab-paclitaxel, 260 mg/m2), trastuzumab (6 mg/kg), and pertuzumab (420 mg). Drugs were administered intravenously on d 1 every 3 weeks in a 21-day cycle (Figure 1). Definitive surgery was scheduled 2−5 weeks postneoadjuvant therapy. The type of surgery (mastectomy, modified radical mastectomy, or breast-conserving surgery) depended on the patient’s choice or surgical indications.

Figure 1.

Treatment schedule. PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; pCR, pathological complete response.

Tumor assessment was performed by ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at baseline and every 2 cycles until completion of 8 cycles of neoadjuvant therapy (presurgery). The radiological response was assessed using RECIST version 1.1. pCR was determined by local histopathological assessment of breast and lymph node tissues postneoadjuvant therapy per the 8th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) ypTNM staging system. Safety and tolerability were assessed by adverse events (AEs), vital signs, electrocardiograms, ECOG performance status, and laboratory tests (hematology, serum biochemistry, urinalysis) at each study cycle. AEs were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for AEs (NCI-CTCAE) version 5.0.

Tumor tissues were collected at baseline for biomarker analysis and evaluated for topoisomerase 2 alpha (TOP2A) expression by independent pathologists. TOP2A expression was assessed prospectively with IHC. TOP2A status was positive with cut-off points of >15% (30) or ≥30% (31) as per previous studies.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was total pCR (tpCR), defined as the absence of invasive lesions in the breast and axillary lymph nodes postneoadjuvant therapy, regardless of residual ductal carcinoma in situ (ypT0/is ypN0). Secondary endpoints included breast pCR [bpCR, defined as the absence of invasive lesions in the breast (ypT0/is) after neoadjuvant therapy], objective response rate [ORR, defined as the percentage of patients with a complete or partial response (CR/PR) per RECIST version 1.1] after 4 cycles of neoadjuvant therapy, ORR and disease control rate [DCR, defined as the percentage of patients with CR, PR, or stable disease (SD)] after 8 cycles of neoadjuvant therapy, and the proportion of patients requiring breast-conserving surgery (BCS). The safety endpoints were the incidence, type, and severity of AEs and cardiac events. The exploratory endpoint was preplanned to evaluate the correlation of biomarkers (TOP2A IHC expression) with clinical efficacy.

Statistical analysis

In this single-arm study, the sample size was based on the primary endpoint pCR. Based on the 50% pCR rate of neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus trastuzumab/pertuzumab in the KRISTINE (32) and TRYPHAENA (33) studies, a sample size of 65 yielded a two-sided 95% confidence interval (95% CI) with a width of 0.25 for a sample pCR rate of 60% using the Clopper-Pearson exact method. Assuming a 15% ineligibility rate, 78 patients were enrolled.

Efficacy was analyzed in the full analysis set, consisting of all patients who received at least one dose of the study drug. The safety analysis was performed in the safety analysis set (SAS), including all patients who received at least one study drug dose and underwent at least one safety assessment. The efficacy endpoints (pCR, ORR, DCR, etc.) were summarized, and the corresponding 95% CIs were estimated using the Clopper-Pearson method. The associations between clinicopathological variables and pCR were calculated post hoc using the Chi-square test. Safety data were summarized with the number and percentage. SPSS software (Version 25.0; IBM Corp., New York, USA) was used for statistical analysis. All statistical tests were two-sided and significant at P<0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

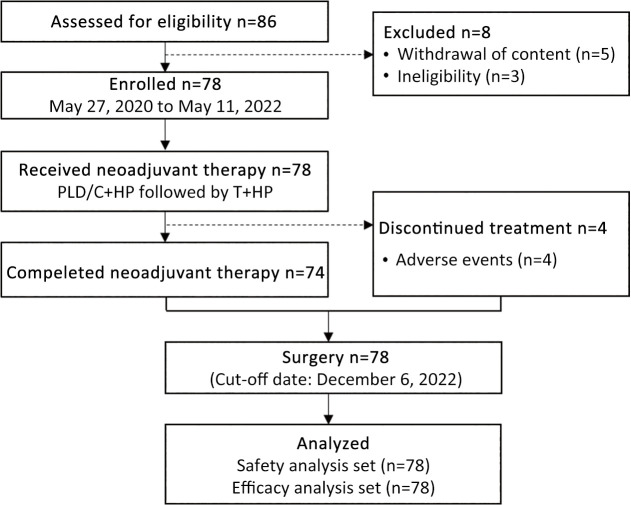

Between May 27, 2020, and May 11, 2022, 86 patients were screened for eligibility, with 8 excluded due to consent withdrawal (n=5) or ineligibility (n=3). A total of 78 HER2-positive BC patients were enrolled in this study (Figure 2). All 78 patients received at least one dose of study treatment and were evaluated for efficacy and safety. The clinical data cut-off date for this analysis, following the last pCR assessment, was December 6, 2022. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The included patients had a median age of 49 (range, 29−70) years at study entry, with 42.3% aged over 50 years. All patients had an ECOG performance status of 0. Most patients were premenopausal (62.8%), had stage II disease (70.5%), and presented with lymph node involvement (70.5%). Twenty-three (29.5%) of 78 patients showed >30% baseline TOP2A IHC expression.

Figure 2.

Study profile. PLD, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; C, cyclophosphamide; T, taxanes; H, trastuzumab; P, pertuzumab.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of included patients (N=78).

| Characteristics | Patients [n (%)] |

| ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hormone receptor; TOP2A, topoisomerase 2 alpha; IHC, immunohistochemistry. | |

| Age (year) [median (range)] | 49 (29−70) |

| <40 | 18 (23.1) |

| 40−50 | 27 (34.6) |

| >50 | 33 (42.3) |

| HR status | |

| Positive | 50 (64.1) |

| Negative | 28 (35.9) |

| ECOG PS 0 | 78 (100) |

| Menopausal status | |

| Premenopausal | 49 (62.8) |

| Postmenopausal | 29 (37.2) |

| Histological type | |

| Ductal carcinoma | 76 (97.4) |

| Lobular carcinoma | 2 (2.6) |

| Histological grade | |

| II | 26 (33.3) |

| II−III | 3 (3.8) |

| III | 18 (23.1) |

| Unknown | 31 (39.7) |

| Lymph node status | |

| Positive | 55 (70.5) |

| Negative | 23 (29.5) |

| Clinical stage | |

| Stage II | 55 (70.5) |

| Stage III | 23 (29.5) |

| T stage | |

| T1 | 3 (3.8) |

| T2 | 49 (62.8) |

| T3 | 23 (29.5) |

| T4 | 3 (3.8) |

| N stage | |

| N0 | 23 (29.5) |

| N1 | 45 (57.7) |

| N2 | 7 (9.0) |

| N3 | 3 (3.8) |

| TOP2A IHC expression | |

| Negative | 1 (1.3) |

| <15% | 14 (17.9) |

| 15%−30% | 31 (39.7) |

| >30% | 23 (29.5) |

| Unknown | 9 (11.5) |

Treatment exposure and surgery

Of the 78 patients starting therapy, 75 (96.2%) completed >4 cycles of neoadjuvant therapy and received sequential taxane therapy, of which 43 received nab-paclitaxel and 32 docetaxel. A total of 74 (94.9%) completed all planned 8 cycles, while 4 withdrew due to toxicity: 2 patients underwent premature surgery for grade 2 interstitial pneumonia (n=1) and hand-foot syndrome, malaise, oral mucositis, and dry skin (n=1); 2 patients had early surgery after 2-cycle pertuzumab/trastuzumab due to grade 4 aspartate aminotransferase (AST) elevation (n=1) and malaise, fever, and oral mucositis (n=1). The median neoadjuvant therapy cycle was 8 (range, 3−8).

All 78 patients underwent surgery, with 42 (53.8%, 95% CI: 42.2%−65.2%) receiving BCS. No treatment-related surgical delay occurred in this study, and the median interval between the last neoadjuvant therapy and surgery was 2.9 (IQR, 2.3−3.6) weeks.

Clinical activity

Forty-seven (60.3%, 95% CI: 48.5%−71.2%) of 78 patients achieved tpCR in the breast and axilla. bpCR was observed in 49 (62.8%, 95% CI: 51.1%−73.5%) patients in the overall population. The tpCR rate was 63.6% in node-positive patients, 69.6% in stage III patients, and 56% in hormone receptor (HR)-positive patients.

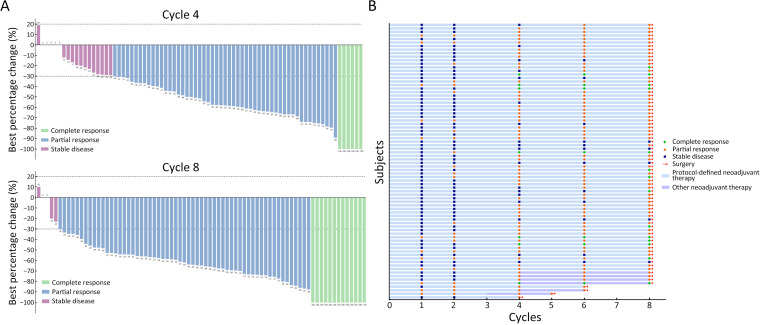

Regarding the imaging response at the end of the first neoadjuvant therapy cycle, all patients achieved disease control (Table 2), with a DCR of 100% (95% CI, 95.4%−100%) and an ORR of 15.4% (95% CI, 8.2%−25.3%). After 2 therapy cycles, the ORR increased to 30.8% (95% CI, 20.8%−42.2%) and reached 76.9% (95% CI, 66.0%−85.7%) after the 4th cycle. At the end of neoadjuvant therapy, 73 (93.6%; 95% CI, 85.7%−97.9%) patients achieved an objective response. Additionally, 5 (6.4%) patients achieved SD after 8 cycles of neoadjuvant therapy, maintaining a DCR of 100% (95% CI, 95.4%−100%). Among the responders, the median response time was 2.8 (range, 0.7−6.2; IQR, 1.5−3.0) months. Figure 3 details the response’s depth and duration.

Table 2. Clinical responses by clinical breast examination during neoadjuvant therapy.

| Variables | Cycle 1 | Cycle 2 | Cycle 4 | Cycle 6 | Cycle 8 (before surgery) |

| 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. | |||||

| Objective response | |||||

| No. | 12 | 24 | 60 | 64 | 73 |

| % (95% CI) | 15.4 (8.2−25.3) | 30.8 (20.8−42.2) | 76.9 (66.0−85.7) | 82.1 (71.7−89.8) | 93.6 (85.7−97.9) |

| Disease control | |||||

| No. | 78 | 78 | 78 | 76 | 78 |

| % (95% CI) | 100 (95.4−100) | 100 (95.4−100) | 100 (95.4−100) | 97.4 (91.0−99.7) | 100 (95.4−100) |

Figure 3.

Tumor response in evaluable patients. (A) Waterfall plot of maximum percent change in target lesion size from baseline in evaluable patients per RECIST 1.1; (B) Response time and treatment duration. Each bar represents a patient.

In the subgroup analyses (Table 3), no clinicopathological variables (e.g., age, menopausal status, clinical stage, tumor size, TOP2A status) were associated with pCR or 4th-cycle ORR.

Table 3. Post-hoc associations between clinicopathological variables and pCR or 4th-cycle ORR.

| Variables | N | pCR [n (%)] | P | 4th-cycle ORR [n (%)] | P | |||

| tpCR | Non-tpCR | ORR | Non-ORR | |||||

| pCR, complete pathological response; ORR, objective response rate; HR, hormone receptor; TOP2A, topoisomerase 2 alpha; IHC, immunohistochemistry; tpCR, total pathological complete response. | ||||||||

| Overall population | 78 | 47 (60.3) | 31 (39.7) | − | 60 (76.9) | 18 (23.1) | − | |

| Age (year) | 0.509 | 0.315 | ||||||

| <40 | 18 | 9 (50.0) | 9 (50.0) | 15 (83.3) | 3 (16.7) | |||

| 40−50 | 27 | 16 (59.3) | 11 (40.7) | 18 (66.7) | 9 (33.3) | |||

| >50 | 33 | 22 (66.7) | 11 (33.3) | 27 (81.8) | 6 (18.2) | |||

| Menopausal status | 0.227 | 0.134 | ||||||

| Premenopausal | 49 | 27 (55.1) | 22 (44.9) | 35 (71.4) | 14 (28.6) | |||

| Postmenopausal | 29 | 20 (69.0) | 9 (31.0) | 25 (86.2) | 4 (13.8) | |||

| HR status | 0.305 | 0.168 | ||||||

| Negative | 28 | 19 (67.9) | 9 (32.1) | 24 (85.7) | 4 (14.3) | |||

| Positive | 50 | 28 (56.0) | 22 (44.0) | 36 (72.0) | 14 (28.0) | |||

| Histological grade | 0.152 | 0.454 | ||||||

| II | 26 | 16 (61.5) | 10 (38.5) | 20 (76.9) | 6 (23.1) | |||

| II−III | 3 | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | |||

| III | 18 | 13 (72.2) | 5 (27.8) | 12 (66.7) | 6 (33.3) | |||

| Unknown | 31 | 18 (58.1) | 13 (41.9) | 26 (83.9) | 5 (16.1) | |||

| Regional lymph node status | 0.346 | 0.683 | ||||||

| Negative | 23 | 12 (52.2) | 11 (47.8) | 17 (73.9) | 6 (26.1) | |||

| Positive | 55 | 35 (63.6) | 20 (36.4) | 43 (78.2) | 12 (21.8) | |||

| T stage | 0.870 | 0.569 | ||||||

| T1−2 | 52 | 31 (59.6) | 21 (40.4) | 41 (78.8) | 11 (21.2) | |||

| T3−4 | 26 | 16 (61.5) | 10 (38.5) | 19 (73.1) | 7 (26.9) | |||

| N stage | 0.346 | 0.683 | ||||||

| N0 | 23 | 12 (52.2) | 11 (47.8) | 17 (73.9) | 6 (26.1) | |||

| N1−3 | 55 | 35 (63.6) | 20 (36.4) | 43 (78.2) | 12 (21.8) | |||

| Clinical stage | 0.277 | 0.441 | ||||||

| II | 55 | 31 (56.4) | 24 (43.6) | 41 (74.5) | 14 (25.5) | |||

| III | 23 | 16 (69.6) | 7 (30.4) | 19 (82.6) | 4 (17.4) | |||

| TOP2A IHC expression | 0.103 | 0.489 | ||||||

| ≤15% | 15 | 7 (46.7) | 8 (53.3) | 13 (86.7) | 2 (13.3) | |||

| >15% | 54 | 32 (59.3) | 22 (40.7) | 41 (75.9) | 13 (24.1) | |||

| Unknown | 9 | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | |||

Safety

Of the 78 evaluable patients, 4 (5.1%) discontinued treatment due to AEs. There was only one (1.3%) AE-related delay during neoadjuvant taxane therapy. Dose reduction for AEs was necessary in 2.6% (2/78) of patients (1 grade 2 hand-foot syndrome and 1 grade 3 skin ulcer) and was attributed to PLD.

Grade 3−4 AEs are listed in Table 4. During the neoadjuvant phase, AEs occurred in 73 (93.6%) patients; 35 (44.9%) experienced at least one grade 3 or worse AE. The most common hematological toxicities of any grade included decreased lymphocyte (79.5%), white blood cell (69.2%), and neutrophil counts (55.1%), as well as anemia (48.7%). Additionally, frequent nonhematological toxicities included alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevation (64.1%), oral mucositis (57.7%), malaise (57.7%), hand-foot syndrome (57.7%), and increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (55.1%). Serious AEs were reported in only 3 (3.8%) patients (interstitial pneumonia, increased AST, decreased white blood cells, and neutrophils). No treatment-related deaths were observed.

Table 4. AEs of any grade and grade 3−4 in all patients.

| Variables | n (%) | |

| Any grade | Grade 3−4 | |

| AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase. | ||

| Any AEs | 73 (93.6) | 35 (44.9) |

| Any serious AEs | 3 (3.8) | 2 (2.6) |

| AEs leading to discontinuation | 4 (5.1) | 1 (1.3) |

| AEs leading to dose delay/reduction | 3 (3.8) | 2 (2.6) |

| Hematologic toxicities | ||

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 62 (79.5) | 19 (24.4) |

| White blood cell decreased | 54 (69.2) | 20 (25.6) |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 43 (55.1) | 16 (20.5) |

| Anemia | 38 (48.7) | 2 (2.6) |

| Platelet count decreased | 6 (7.7) | 0 (0) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) |

| Non-hematologic toxicities (≥20% incidence) |

||

| Mucositis oral | 45 (57.7) | 2 (2.6) |

| Diarrhea | 41 (52.6) | 0 (0) |

| Nausea | 38 (48.7) | 0 (0) |

| Constipation | 32 (41.0) | 0 (0) |

| Vomiting | 31 (39.7) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrointestinal pain | 21 (26.9) | 0 (0) |

| Abdominal pain | 17 (21.8) | 0 (0) |

| Malaise | 45 (57.7) | 0 (0) |

| Fatigue | 16 (20.5) | 0 (0) |

| ALT increased | 50 (64.1) | 4 (5.1) |

| AST increased | 43 (55.1) | 5 (6.4) |

| GGT increased | 22 (28.2) | 2 (2.6) |

| Alkaline phosphatase increased | 16 (20.5) | 0 (0) |

| Anorexia | 42 (53.8) | 1 (1.3) |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 19 (24.4) | 0 (0) |

| Dizziness | 33 (42.3) | 0 (0) |

| Insomnia | 20 (25.6) | 0 (0) |

| Hand-foot syndrome | 45 (57.7) | 3 (3.8) |

| Alopecia | 30 (38.5) | 0 (0) |

| Skin hyperpigmentation | 16 (20.5) | 0 (0) |

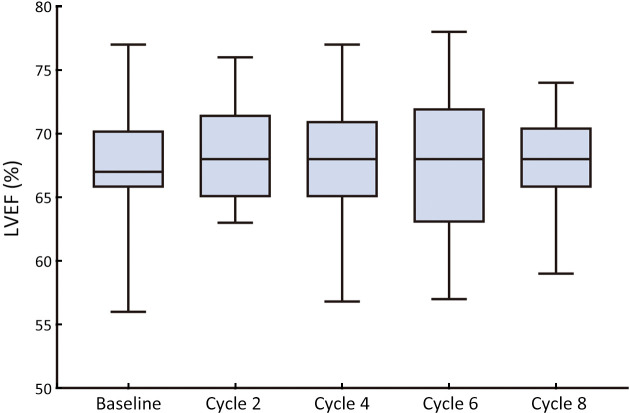

In terms of cardiotoxicity, LVEF reduction (absolute value ≥10% from baseline) occurred in 9 (11.5%) patients, all with a minimum value of >55% (Supplementary Figure S1). Additionally, 11 (14.1%) patients experienced other cardiac-related events, including B-natriuretic peptide (BNP) elevation (3.8%) and palpitations (10.3%). No symptomatic congestive heart failure has been reported. We observed a decrease in mean N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-proBNP) at cycle 8 and an increase in troponin I (cTnI) levels at cycles 4 and 8 (Supplementary Table S2). Only 1 of 78 (1.3%) evaluable patients had abnormal posttreatment NT-proBNP at cycles 4 and 8, with no reports of abnormal high-sensitivity troponin (TNT-HS) or cTnI. Enrolled patients did not have any symptomatic or cardiac events that led to PLD reduction or discontinuation.

Figure S1.

LVEF changes during neoadjuvant treatment. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Table S2. Parameters related to cardiac function.

| Variables | NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | TNT-HS (pg/mL) | cTnI (μg/L) | |||||

|

n (%) |

|

n (%) |

|

n (%) | |||

| The abnormal rate for NT-proBNP means the value higher than 125 pg/mL, for TNT-HS means the value higher than 14 pg/mL, for cTnI means the value higher than 0.04 μg/L. *, indicated P<0.05 (statistically significant). NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; TNT-HS, high-sensitivity troponin; cTnI, troponin I. | ||||||||

| Baseline | 40.6±29.6 | 0 (0) | 4.0±2.8 | 0 (0) | 0.002±0.004 | 0 (0) | ||

| Cycle 4 | 38.1±50.2 | 1 (1.3) | 3.7±1.6 | 0 (0) | 0.003±0.003* | 0 (0) | ||

| Cycle 8 | 32.1±37.1* | 1 (1.3) | 3.4±0.8 | 0 (0) | 0.005±0.004* | 0 (0) | ||

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is one of the few studies of sequential neoadjuvant therapy with liposomal doxorubicin and dual HER2-blockade in HER2-positive BC. PLD plus cyclophosphamide followed by taxanes with trastuzumab/pertuzumab showed a promising tpCR of 60.3% and induced rapid tumor regression in this disease. This regimen demonstrated an acceptable safety profile, particularly with a low risk of cardiac events.

Despite recent controversies, anthracyclines remain a cornerstone in neoadjuvant BC therapy, especially for high-risk patients. HER2-positive tumors are highly sensitive to anthracycline-containing chemotherapy (34,35). Attempts to use regimens with low cardiotoxicity agents in Caucasians, due to anthracyclines and trastuzumab’s overlapping cardiotoxicity, have compromised tpCR improvements (30%−49%) (21,36). Currently, increasing preclinical and clinical data suggest that dual HER2-blockade could be more effective than single blockade in HER2-amplified BC (37). Therefore, to improve response, we investigated dual HER2-blockade with a low cardiotoxicity regimen, achieving a promising result of 60.3% tpCR and 62.8% bpCR in 78 surgical patients. Compared with the standard dual HER2-blockade plus chemotherapy reported in the TRYPHAENA (50.7%) (33) and TRAIN-2 (67%) (20) trials, replacing conventional anthracyclines with PLD in our regimen yielded a promising pCR rate without compromising tumor control. The preferential use of PLD over conventional anthracyclines can improve tolerability and patient compliance due to reduced cardiotoxicity, leading to promising therapeutic effects (38,39). Analysis of these data suggests this sequential regimen achieves higher pCR compared with the 47.3% tpCR in the Opti-HER HEART study (14). We noted that these historical data mostly come from Caucasian cohorts; thus, differences in patient background (ethnicity, underlying diseases, etc.) may be responsible for higher pCR. Thus, cross-trial comparisons should be viewed with caution. This phase II study demonstrated that PLD with cyclophosphamide, followed by concurrent taxanes and trastuzumab/pertuzumab, is effective for HER2-positive BC.

The present study also found rapid tumor regression and significant shrinkage from PLD/cyclophosphamide plus trastuzumab/pertuzumab, as demonstrated by the high ORR and DCR during the 2nd and 4th neoadjuvant therapy cycles. The relatively short response time (median 2.9 months) also supported the finding of a rapid response. Pharmacologically, rapid tumor regression might be due to PLD’s passive targeting, which potentially enhance liposomal drugs’ therapeutic effect (40). Furthermore, a quicker response improves survival (41). Meanwhile, a large-scale meta-analysis provides evidence that anthracycline plus taxane regimens effectively reduce BC recurrence and death (42). Accordingly, based on this evidence, we assumed this neoadjuvant regimen may yield significant survival benefits for HER2-positive BC. Our findings also implied that a short treatment cycle may suffice to induce a rapid, encouraging response, thus eliminating the need for longer treatment cycles. Subgroup analysis revealed no clinicopathological characteristics associated with pCR or 4th-cycle ORR. It might demonstrate this regimen’s generalizability to broader populations as there is no preferred target population.

In terms of safety, this sequential neoadjuvant regimen was tolerable in this population. The frequent AEs reported in this study, including hematologic toxicities, malaise, and hand-foot syndrome, were known and generally mild with few serious events. No new safety signals or treatment-related deaths were identified in the present analysis. Overall, the safety profiles were consistent with those reported in other studies (8,33,43). More crucially, this regimen had a low cardiotoxicity risk, which is a major safety concerning with combined HER2-targeted agents and anthracyclines. Here, among 78 treated patients, no symptomatic congestive heart failure was observed, and although 9 experienced LVEF reduction, all had a minimum value of >55%. A greater LVEF reduction was observed compared to dual HER2-blockade regimens such as the GeparQuattro trial (LVEF≤45%) (16), the TRYPHAENA trial (<50%) (33), the TRAIN-2 study (45%) (43), and the GeparSepto-GBG 69 trial (<50%) (44). Additionally, the detailed assessment for cardiotoxicity showed reduced cardiac toxicity, as evidenced by no abnormal changes in cardiac function parameters (BNP, NT-proBNP, cTnI, TnI-HS). Overall, sequential therapy with liposomal doxorubicin and trastuzumab/pertuzumab may be less cardiotoxic, supporting our hypothesis. This finding aligns with Saracchini et al.’s results that liposomal doxorubicin safely minimizes cardiotoxicity (45). Previous studies suggest that reduced cardiotoxicity can be partly attributed to changes in the dosage forms of paclitaxel and doxorubicin (28,44). Nevertheless, this hypothesis warrants testing in a larger, randomized phase III trial.

Several limitations of our study should be considered when interpreting the results, both in terms of the study design and execution. First, we must acknowledge that a significant proportion (5%) of the 78 patients in our study discontinued planned treatment early but were included in the efficacy analysis, potentially affecting our results’ strength. Another limitation of our trial is the lack of long-term cardiac safety and survival data due to the short follow-up period. Although no survival outcome was available, previous studies have linked pCR with improved long-term outcomes in HER2-positive BC (46). Moreover, as is typical of early-phase trials, the study was explorative, open-label, nonrandomized, and should be interpreted with caution. Therefore, these early data are not comprehensive and need verification with larger data sets.

Conclusions

This phase II study is one of the few studies to analyze PLD/cyclophosphamide followed by taxanes with trastuzumab/pertuzumab in the neoadjuvant setting, demonstrating impressive, rapid antitumor activity in HER2-positive BC. Importantly, this regimen was well tolerated with few cardiac events, indicating a promising, safer treatment option for these patients. The observed clinical benefit of this low-toxicity sequential regimen warrants further randomized trials.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82003311, No. 82061148016, No. 82230057 and No. 82272859); National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFC2505101); Sun Yat-Sen Clinical Research Cultivating Program (No. SYS-Q-202004); Beijing Medical Award Foundation (No. YXJL-2020-0941-0760); Guangzhou Science and Technology Program (No. 202102010272 and No. 202201020486).

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pupa SM, Ligorio F, Cancila V, et al HER2 signaling and breast cancer stem cells: the bridge behind HER2-positive breast cancer aggressiveness and therapy refractoriness. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:4778. doi: 10.3390/cancers13194778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiang H, Xin L, Ye J, et al A multicenter study on efficacy of dual-target neoadjuvant therapy for HER2-positive breast cancer and a consistent analysis of efficacy evaluation of neoadjuvant therapy by Miller-Payne and RCB pathological evaluation systems (CSBrS-026) Chin J Cancer Res. 2023;35:702–12. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2023.06.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sareyeldin RM, Gupta I, Al-Hashimi I, et al Gene expression and miRNAs Profiling: function and regulation in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:646. doi: 10.3390/cancers11050646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel A, Unni N, Peng Y The changing paradigm for the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:2081. doi: 10.3390/cancers12082081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith AE, Ferraro E, Safonov A, et al HER2 + breast cancers evade anti-HER2 therapy via a switch in driver pathway. Nat Commun. 2021;12:6667. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27093-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harbeck N, Gnant M Breast cancer. Lancet. 2017;389:1134–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31891-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gianni L, Pienkowski T, Im YH, et al Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in women with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): a randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:25–32. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70336-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gianni L, Pienkowski T, Im YH, et al 5-year analysis of neoadjuvant pertuzumab and trastuzumab in patients with locally advanced, inflammatory, or early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer (NeoSphere): a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:791–800. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wuerstlein R, Harbeck N Neoadjuvant therapy for HER2-positive breast cancer. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2017;12:81–92. doi: 10.2174/1574887112666170202165049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohan N, Jiang J, Dokmanovic M, et al Trastuzumab-mediated cardiotoxicity: current understanding, challenges, and frontiers. Antib Ther. 2018;1:13–7. doi: 10.1093/abt/tby003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.An J, Sheikh MS Toxicology of trastuzumab: an insight into mechanisms of cardiotoxicity. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2019;19:400–7. doi: 10.2174/1568009618666171129222159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gavilá J, Oliveira M, Pascual T, et al Safety, activity, and molecular heterogeneity following neoadjuvant non-pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, paclitaxel, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer (Opti-HER HEART): an open-label, single-group, multicenter, phase 2 trial. BMC Med. 2019;17:8. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1233-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bozovic-Spasojevic I, Azim HA Jr, Paesmans M, et al Neoadjuvant anthracycline and trastuzumab for breast cancer: is concurrent treatment safe. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:209–11. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Untch M, Rezai M, Loibl S, et al Neoadjuvant treatment with trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer: results from the GeparQuattro study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2024–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomssen C, Balic M, Harbeck N, et al. St. Gallen/Vienna 2021: A brief summary of the consensus discussion on customizing therapies for women with early breast cancer. Breast Care (Basel) 2021;16:135-43.

- 18.van der Voort A, van Ramshorst MS, van Werkhoven ED, et al Three-year follow-up of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without anthracyclines in the presence of dual ERBB2 blockade in patients with ERBB2-positive breast cancer: a secondary analysis of the TRAIN-2 randomized, phase 3 Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:978–84. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hurvitz SA Anthracycline use in ERBB2-positive breast cancer: it is time to Re-TRAIN. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:975–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Ramshorst MS, van der Voort A, van Werkhoven ED, et al Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without anthracyclines in the presence of dual HER2 blockade for HER2-positive breast cancer (TRAIN-2): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:1630–40. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30570-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tuxen MK, Cold S, Tange UB, et al Phase II study of neoadjuvant pegylated liposomal doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide ± trastuzumab followed by docetaxel in locally advanced breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2014;53:1440–5. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.921727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buzdar AU, Suman VJ, Meric-Bernstam F, et al Fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FEC-75) followed by paclitaxel plus trastuzumab versus paclitaxel plus trastuzumab followed by FEC-75 plus trastuzumab as neoadjuvant treatment for patients with HER2-positive breast cancer (Z1041): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1317–25. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70502-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu AF, Singh JC, Wang R, et al Cardiac safety of dual anti-HER2 therapy in the neoadjuvant setting for treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer. Oncologist. 2017;22:642–7. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rocca A, Cortesi P, Cortesi L, et al. Phase II study of liposomal doxorubicin, docetaxel and trastuzumab in combination with metformin as neoadjuvant therapy for HER2-positive breast cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2021;13:1758835920985632.

- 25.Slamon D, Eiermann W, Robert N, et al Adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1273–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harbeck N Advances in targeting HER2-positive breast cancer. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2018;30:55–9. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong M, Luo L, Ying X, et al Comparable efficacy and less toxicity of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus epirubicin for neoadjuvant chemotherapy of breast cancer: a case-control study. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:4247–52. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S162003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Brien ME, Wigler N, Inbar M, et al Reduced cardiotoxicity and comparable efficacy in a phase III trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin HCl (CAELYX/Doxil) versus conventional doxorubicin for first-line treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:440–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, et al Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3997–4013. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikolényi A, Sükösd F, Kaizer L, et al Tumor topoisomerase II alpha status and response to anthracycline-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Oncology. 2011;80:269–77. doi: 10.1159/000329038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Susini T, Berti B, Carriero C, et al Topoisomerase II alpha and TLE3 as predictive markers of response to anthracycline and taxane-containing regimens for neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2014;7:2111–20. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S71646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hurvitz SA, Martin M, Symmans WF, et al Neoadjuvant trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and chemotherapy versus trastuzumab emtansine plus pertuzumab in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer (KRISTINE): a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:115–26. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30716-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneeweiss A, Chia S, Hickish T, et al Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab in combination with standard neoadjuvant anthracycline-containing and anthracycline-free chemotherapy regimens in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer: a randomized phase II cardiac safety study (TRYPHAENA) Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2278–84. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pritchard KI, Messersmith H, Elavathil L, et al HER-2 and topoisomerase II as predictors of response to chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:736–44. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu YT, Xu Z, Arshad B, et al Significantly higher pathologic complete response (pCR) after the concurrent use of trastuzumab and anthracycline-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy for HER2-positive breast cancer: Evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Cancer. 2018;9:3168–76. doi: 10.7150/jca.24701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hyams D, Leichman G, Klein P, et al Phase II trial of neoadjuvant pegylated liposomal doxorubicin with paclitaxel and trastuzumab in patients with operable Her2-positive breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1098. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.SABCS-09-1098. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel TA, Dave B, Rodriguez AA, et al Dual HER2 blockade: preclinical and clinical data. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:419. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0419-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petersen GH, Alzghari SK, Chee W, et al Meta-analysis of clinical and preclinical studies comparing the anticancer efficacy of liposomal versus conventional non-liposomal doxorubicin. J Control Release. 2016;232:255–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shafei A, El-Bakly W, Sobhy A, et al A review on the efficacy and toxicity of different doxorubicin nanoparticles for targeted therapy in metastatic breast cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;95:1209–18. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Makwana V, Karanjia J, Haselhorst T, et al Liposomal doxorubicin as targeted delivery platform: Current trends in surface functionalization. Int J Pharm. 2021;593:120117. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.120117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cameron DA, Anderson ED, Levack P, et al. Primary systemic therapy for operable breast cancer — 10-year survival data after chemotherapy and hormone therapy. Br J Cancer 1997;76:1099-105.

- 42.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Anthracycline-containing and taxane-containing chemotherapy for early-stage operable breast cancer: a patient-level meta-analysis of 100 000 women from 86 randomised trials. Lancet. 2023;401:1277–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00285-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Ramshorst MS, van Werkhoven E, Honkoop AH, et al Toxicity of dual HER2-blockade with pertuzumab added to anthracycline versus non-anthracycline containing chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment in HER2-positive breast cancer: The TRAIN-2 study. Breast. 2016;29:153–9. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Untch M, Jackisch C, Schneeweiss A, et al Nab-paclitaxel versus solvent-based paclitaxel in neoadjuvant chemotherapy for early breast cancer (GeparSepto-GBG 69): a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:345–56. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00542-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saracchini S, Foltran L, Tuccia F, et al Phase II study of liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide, followed by sequential trastuzumab plus docetaxel as primary systemic therapy for breast cancer patients with HER2 overexpression or amplification. Breast. 2013;22:1101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cortazar P, Zhang L, Untch M, et al Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet. 2014;384:164–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]