Abstract

There is a critical unmet need to detect and image 2D materials within single cells and tissues while surveying a high degree of information from single cells. Here, a versatile multiplexed label-free single-cell detection strategy is proposed based on single-cell mass cytometry by time-of-flight (CyTOF) and ion-beam imaging by time-of-flight (MIBI-TOF). This strategy, “Label-free sINgle-cell tracKing of 2D matErials by mass cytometry and MIBI-TOF Design” (LINKED), enables nanomaterial detection and simultaneous measurement of multiple cell and tissue features. As a proof of concept, a set of 2D materials, transition metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides (MXenes), is selected to ensure mass detection within the cytometry range while avoiding overlap with more than 70 currently available tags, each able to survey multiple biological parameters. First, their detection and quantification in 15 primary human immune cell subpopulations are demonstrated. Together with the detection, mass cytometry is used to capture several biological aspects of MXenes, such as their biocompatibility and cytokine production after their uptake. Through enzymatic labeling, MXenes’ mediation of cell–cell interactions is simultaneously evaluated. In vivo biodistribution experiments using a mixture of MXenes in mice confirm the versatility of the detection strategy and reveal MXene accumulation in the liver, blood, spleen, lungs, and relative immune cell subtypes. Finally, MIBI-TOF is applied to detect MXenes in different organs revealing their spatial distribution. The label-free detection of 2D materials by mass cytometry at the single-cell level, on multiple cell subpopulations and in multiple organs simultaneously, will enable exciting new opportunities in biomedicine.

Keywords: biocompatibility, biomedical applications, immune system, MXenes, nanomedicine

1. Introduction

The ability to track, detect, and quantitatively measure nanomaterials in cells and tissues has driven their increasing exploitation in biomedicine. The development of label-free, high-resolution, and high-dimensional approaches that simultaneously visualize 2D) materials in multiple cell types, thus enabling insight into cell functions and interactions, together with their spatial localization in tissues, will be crucial for translating nanomaterials to clinical applications.

Transition metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides (MXenes)[1,2] are emergent 2D materials with a wide variety of structures and compositions.[3,4] Although the most studied MXene is Ti3C2, more than 30 stoichiometric compositions and at least 20 solid solutions have been reported. The surfaces of those 2D sheets are covered by functional groups, written as Tx. These groups primarily comprise O, OH and F, and thus are hydrophilic and easily dispersible in water and physiologic media. Because most MXenes have been shown to have biocompatibility and no cytotoxicity, they have been widely explored in diverse fields[5–7] including medicine.[8–14] In particular, simultaneous therapeutic strategies and detection/visualization technologies aimed either at imaging/diagnosis or at guiding therapy have enabled new perspectives in theranostics with 2D materials[8].

The use of MXenes for photothermal therapy, medical imaging, drug delivery and other biomedical applications[8,11–13,15–19] requires the ability to detect MXenes at the tissue and cell levels in vitro and in vivo. An ideal detection modality should enable label-free single-cell level resolution and the simultaneous interrogation of many cellular parameters.

Single-cell mass cytometry by time-of-flight (CyTOF) is a well-established technique based on mass spectrometry to detect metal element-tagged probes, thus allowing for parameter discrimination according to their mass/charge ratio (m/z), with minimal overlap or signal background.[20,21] Whereas CyTOF is limited to cells in suspension, such as circulating blood cells or cells dissociated from tissues, imaging mass cytometry (IMC)[22,23] and multiplexed ion-beam imaging by time-of-flight (MIBI-TOF)[24,25] similarly use elementally labeled probes to measure dozens of molecular parameters at single-cell resolution in situ. These techniques are becoming increasingly prevalent and have greatly advanced diverse fields including immunology, oncology, neuroscience, and infectious diseases.[23,24,26,27]

We have recently demonstrated the use of CyTOF for studying the immunocompatibility of graphene.[28] Because carbon is not trackable with mass cytometry, its detection has been enabled through functionalization with AgInS2 nanocrystals.[29] However, the material functionalization itself may affect the toxicological profile,[30,31] and the cell interaction and uptake capabilities;[32,33] it may additionally affect the intrinsic features of 2D materials that are exploitable for therapeutic/bioimaging purposes,[8] thus possibly impairing their biomedical effectiveness.

A versatile approach combining label-free detection with high-dimensional data analysis at the single-cell level would greatly enable the exploration of novel 2D materials in biomedicine.[2,30,34,35] Among those materials, MXenes are notable for their chemical versatility and consequently are attractive candidates for a 2D material that can be detected and imaged by CyTOF, IMC, and MIBI-TOF.

Here, we introduce the “Label-free sINgle-cell tracKing of 2D matErials by mass cytometry and MIBI-TOF Design” (LINKED) approach for the detection of nanomaterials (Figure 1). In LINKED, we designed 2D materials that can be directly identified by mass cytometry and imaging at the single-cell level (Figure 1a). Importantly, this design abrogates the need for additional chemical functionalization, thus overcoming many of the limitations of other imaging approaches.[23,36]

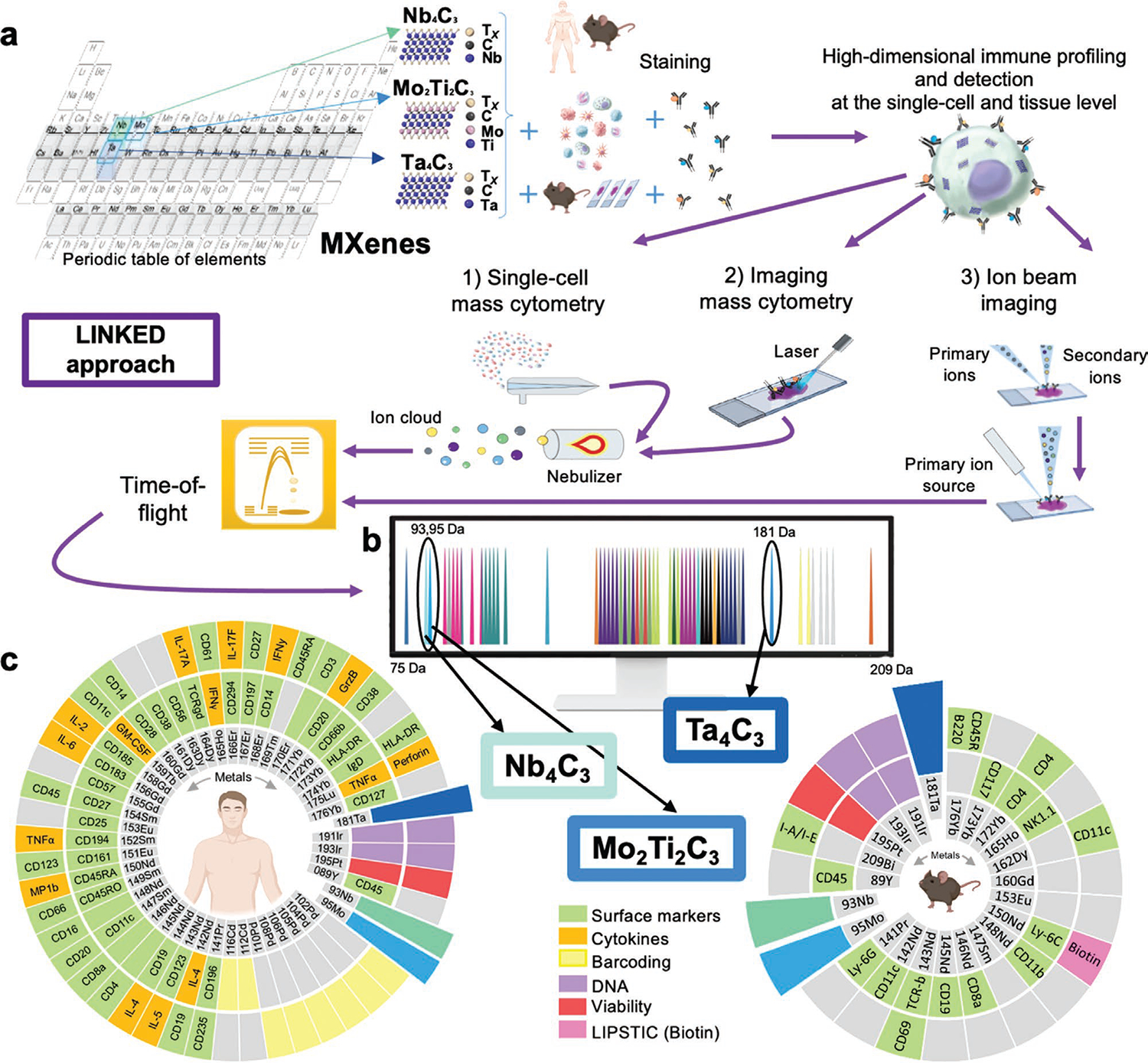

Figure 1.

”Label-free sINgle-cell tracKing of 2D matErials by mass cytometry and MIBI-TOF Design” (LINKED) approach. a) Selection of CyTOF-visible elements, shown in gray in the periodic table, to synthesize biocompatible MXenes: Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3, and Ta4C3; a schematic representation for their detection on cell and tissues using three mass-cytometry-based methods (single-cell mass cytometry, imaging mass cytometry, and ion-beam imaging) is also shown. b) Mass cytometry permits the detection of stable isotope masses from 75 to 209 Da. The colored pictures represent all current metal tags used in CyTOF. MXenes here designed by LINKED were inserted in unexplored channels. Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3, and Ta4C3 detection is permitted in the 93Nb, 95Mo and 180Ta channels, respectively. c) MXene compatibility with available commercial tags used in the present study: a total of 48 isotopes have been used for human ex vivo and for ex vivo and in vivo mouse experiments. A total of 76 mass cytometry probes have been used (56 for human and 21 for mice) for the assessment of viability, cytokine detection, markers for cluster of differentiation (CD), palladium and cadmium-based barcoding, DNA staining, and biotin detection.

We took several aspects into consideration in designing these MXenes. First, we wanted the materials to fit the detection range of CyTOF and MIBI-TOF, from 79 to 209 in atomic mass. Next, we aimed to avoid any overlap with channels commonly used for metal conjugated antibodies (Figure 1b). We identified Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3, and Ta4C3 MXenes as eligible candidates, which could be identified in the 93Nb, 95Mo and 181Ta channels, respectively. Ti3C2, the most widely used MXene for biomedical applications,[10] was selected as a reference material not visible by mass spectrometry because of its low mass. The full material physicochemical characterization is reported in Figure S1, Supporting Information. We stained peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy human donors, as well as ex vivo and in vivo mouse samples, with a wide variety of metal-conjugated antibodies, then assessed their detection and immune profiling with CyTOF, IMC, and MIBI-TOF. The LINKED-driven design of MXenes allowed for the insertion of novel channels of detection for CyTOF, IMC, and MIBI-TOF, particularly 93Nb and 95Mo, which have not previously been explored (Figure 1b). Moreover, according to LINKED, the selected materials are highly compatible and non-overlapping with currently available antibody panels. Here, we demonstrated their compatibility with more than 70 metal-tagged antibodies, as well as palladium- and cadmium-based barcodes used for ex vivo human immune-phenotyping/immune cell functionality analysis and in vivo mice experiments (Figure 1c).

The study workflow is reported in Figure S2, Supporting Information, which shows the various levels of complexity, from material production to their assessment ex vivo in terms of high-dimensional immune profiling using different technological platforms, to their detection in multiple human cell types and in several organs in mice. Detection data were then confirmed in situ through MIBI-TOF. In addition, to reveal the possible effects of MXenes on immune cell interactions, we used an enzymatic labeling approach that we have recently proposed to characterize the complex T-cell–dendritic cell interactions,[37] which we adapted to mass cytometry.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. MXenes Can Be Detected at the Single-Cell Level without Additional Chemical Functionalization

The tracking of 2D materials is critical to expanding their biomedical applications. Therefore, we explored the possibility of detecting MXenes at the single-cell level by CyTOF, simultaneously interrogating many cellular parameters. To this end, we chose the complex pool of PBMCs, consisting of a large variety of immune cell subpopulations, as an ideal ex vivo model for a proof-of-concept study to develop LINKED.[38]

Initially, to investigate the biocompatibility of MXenes, we treated PBMCs with increasing concentrations of Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3,, and Ta4C3 (12.5, 25, 50, and 100 μg mL−1) for 24 h, then evaluated cell viability with calcein (Figure S3a, Supporting Information) and flow cytometry analysis (Figure S3b, Supporting Information), which showed no cytotoxic effects.

Subsequently, we used CyTOF to explore the potential detection of Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3, and Ta4C3, and reveal the immunological effects on individual cells. The specific atomic masses of the 2D materials selected in this work enabled mass spectrometry detection of Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3,, and Ta4C3 in the niobium (93Nb), molybdenum (95Mo), and tantalum (180–181Ta) channels, respectively.

We chose the sub-cytotoxic concentration of 50 μg mL−1 and the 24 h time-point on the basis of the results of the viability assays (Figure S3, Supporting Information) and to ensure noticeable changes in immune cell functionality in terms of cytokine release and gene expression modulation, according to our previous experience with graphene-based materials.[28,29] Using a panel of 61 metal-tagged antibodies (Table S1, Supporting Information), we identified 15 distinct immune cell types according to the expression profiles of several cluster of differentiation (CD) markers present on the cell surfaces (gating strategy in Figure S4, Supporting Information). Computational tSNE analysis was performed as previously reported.[28,29] The tSNE plots (Figure 2a), heat maps (Figure 2b–d) and bar graphs (Figure 2e,f) indicated that all 2D materials were naturally visible at the single-cell level and interacted with a vast number of immune cell subpopulations.

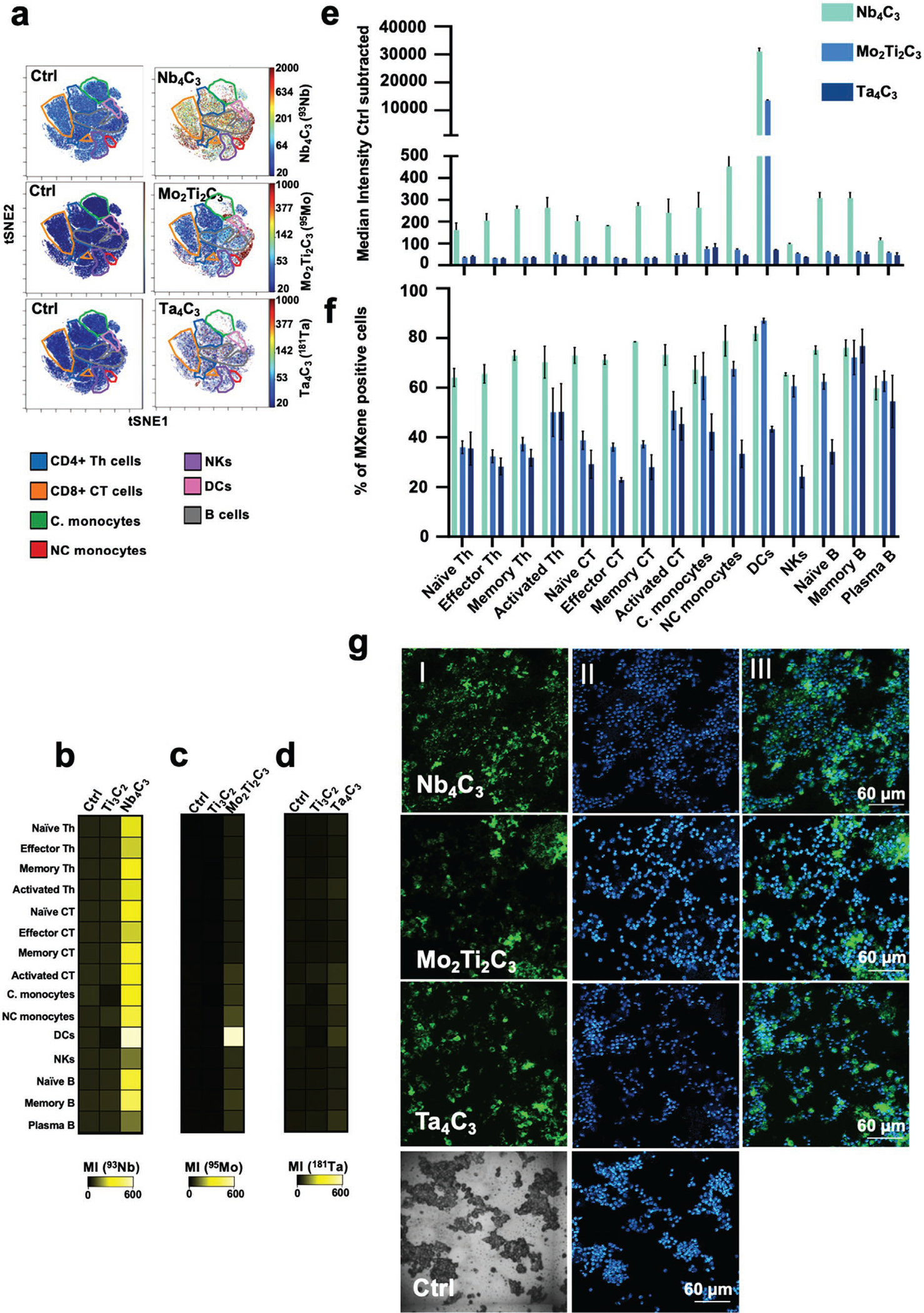

Figure 2.

MXene tracking in human PBMCs at the single-cell level. a–f) PBMCs were incubated with 50 μg mL−1 of Ti3C2, Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3 or Ta4C3 for 24 h and stained for mass cytometry analysis. Representative tSNE for each MXene showing the single-cell signal intensity compared to the control (Ctrl); intensity is represented from blue (low interaction) to red (high interaction) (a). Heat maps reporting the MXenes’ median intensity for each specific channel in all the major immune cell subpopulations identified (b)–(d). Grouped bar plots showing Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3, and Ta4C3 median intensity (e) and % of positive cells for all the replicates in all PBMC subpopulations identified (f). g, MXenes detection in human PBMCs by imaging mass cytometry (IMC). Panels (I) represent IMC images reporting in green the single-cell tracking of Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3 or Ta4C3. Panels (II) represent IMC images reporting in blue and light blue the DNA signal. Panels (III) represent IMC images reporting a composite image of DNA (blue) and Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3 or Ta4C3 (green). All the experiments were performed in triplicate and shown as means ± standard deviation (SD).

Among the MXenes, Nb4C3 had the strongest signal and showed extensive interaction with all immune cell subpopulations identified. In particular, dendritic cells (DCs) showed the most prominent binding to Nb4C3., Mo2Ti2C3 and Ta4C3 showed similar single-cell signal levels and were similarly trackable in many immune subsets. However, compared with Ta4C3, Mo2Ti2C3 had an overall greater ability to interact with the cells, particularly DCs (Figure 2). The single-cell view by t-SNE confirmed that MXenes interacted with all immune subpopulations (Figure S5, Supporting Information).

In addition, we evaluated MXene interaction and detection by IMC on human PBMCs (Figure 2g). All 2D materials were successfully identified by IMC, and their signals were mutually exclusive with that of DNA, thus indicating that they did not localize to cell nuclei. To support the cellular interaction data of CyTOF and IMC, we performed conventional transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis of PBMCs. All materials were readily internalized without any ultrastructural signs of cell death (Figure S6, Supporting Information) and were found either as tightly packed “bundles” in the cytoplasm or within large cytoplasmic vacuoles, whereas no materials were found in the cell nucleus, thereby confirming the results obtained with IMC.

Finally, cisplatin staining revealed that the different 2D material interactions observed among and within the treated cell subpopulations were not associated with a loss of cell viability (Figures S7 and S8, Supporting Information).

Together, our results indicated that MXenes are biocompatible in all PBMC subpopulations and can be detected by CyTOF and IMC without chemical functionalization, in conjunction with all conventionally used metal-labeled antibodies.

2.2. MXenes Do Not Affect Immune Cell Functionality

We then assessed the possible correlation between MXene cell interaction and impact on cell viability, revealing a high biocompatibility of the materials regardless of the extent of interaction (Figure 3a–c). Cytokine production influences several aspects of human health, and their potential modulation by MXenes might be used to guide specific clinical translation applications. Therefore, we assessed immune cell functionality by measuring several secreted cytokines with Luminex assays on the complex pool of PBMCs (Figure 3d) and by intracellular staining to reveal the different populations via CyTOF (Figure S9, Supporting Information). Heat maps represent the median expression values of the cytokines and activation markers analyzed in all immune cell subpopulations identified after treatment with MXenes.

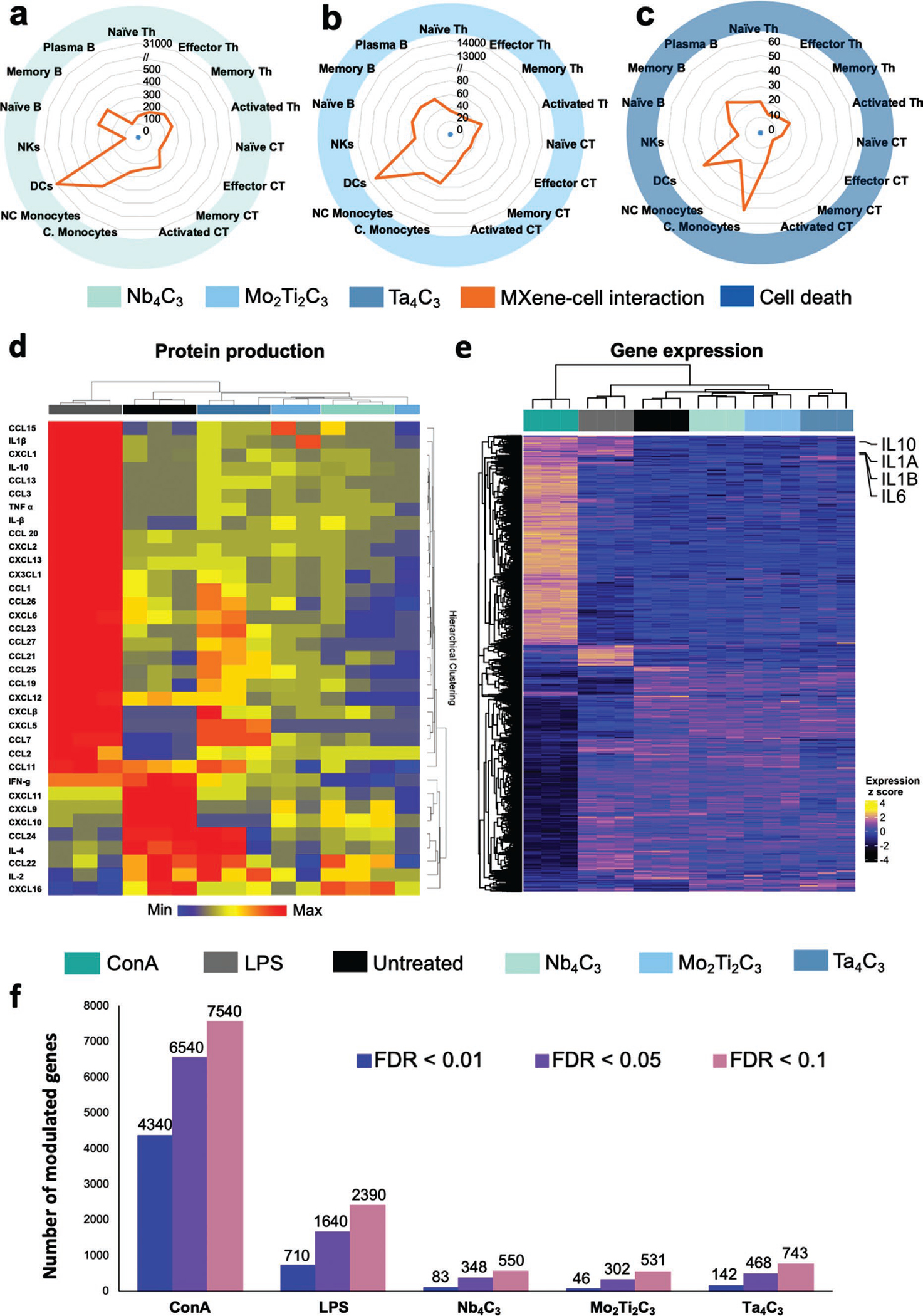

Figure 3.

Analysis of cell viability versus MXene single-cell binding, single-cell cytokine analysis, and RNA sequencing on human PBMC subpopulations. a–c) PBMCs were treated with 50 μg mL−1 of Ti3C2, Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3 or Ta4C3 for 24 h. The spider charts represent the impact on viability (blue), expressed as Cisplatin (Cis) median intensity, versus the MXene tracking (orange) expressed for fifteen immune cell types after exposure of PBMCs to 50 μg mL−1 of Nb4C3 (a), Mo2Ti2C3 (b) or Ta4C3 (c) for 24 h. d) Cell functionality analysis of PBMCs by Luminex technology. The heat map shows the hierarchical cluster analysis of inflammatory mediators released by PBMCs treated with 50 μg mL−1 of Ta4C3, Mo2Ti2C3 or Nb4C3 for 24 h. As a positive control, cells were exposed to LPS (2 μg mL−1). Association clusters for samples are represented by dendrograms at the top of the heat map. Individual cytokines were colored according to z-scored normalized value (blue = downregulated, yellow square = unmodulated cytokines, red = upregulated cytokines). The analytes represented are the ones passing the FDR p-value of 0.05 by fitting a general ANOVA model between control and all the experimental conditions. e,f) Gene expression analysis by mRNA-Seq. Heatmap of all differentially expressed genes between ConA, LPS, Ta4C3, Mo2Ti2C3 and Nb4C3 versus control using FDR < 0.01; classic LPS-induced transcripts (IL1AB, IL10, and IL6) associated with monocyte activations are represented (e). Numbers of differentially expressed genes based on different cutoff of p-adjusted FDR value between experimental conditions and control (f). All the experiments were performed in triplicate and shown as means ± SD.

Overall, the MXenes selected in this work, compared with other 2D materials such as graphene, exhibited only a slight modulation of the inflammatory mediators analyzed.[8,39] In detail, MXenes induced an overall neutral or inhibitory effect, which was particularly relevant in memory B cells. In contrast, an upregulatory effect limited to several cytokines was observed in DCs and natural killer cells for Ti3C2 and Nb4C3, respectively, and in non-classical monocytes and activated cytotoxic T cells for Mo2Ti2C3 (Figure S9, Supporting Information).

Next, we investigated the effects of MXenes on PBMC by using mRNA sequencing, a sensitive and unbiased approach (Figure 3e and Figure S10, Supporting Information). By performing principal component analysis on all analyzed transcripts (N = 19 959), we found that MXene-treated samples clustered close to the controls, and separately from concanavalin A (ConA)- and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-treated samples, thus indicating that only minimal perturbations were induced by the investigated materials (Figure S10a, Supporting Information). Overall, we did not observe genome-wide changes induced by MXenes, even with permissive p-value cutoffs (Figure 3e,f). All materials showed modest effects on human PBMCs, modulating the expression of fewer genes than the positive controls ConA and LPS (Figure 3e,f). In particular, even if all materials had similar effects on gene expression modulation, Ta4C3 had slightly greater effects than Mo2Ti2C3 and Nb4C3. The expression of 142, 46, and 83 genes was modulated by Ta4C3, Mo2Ti2C3 and Nb4C3, respectively, whereas the positive controls ConA and LPS modulated the expression of 4340 and 710 genes, respectively (FDR < 0.01) (Figure 3f). Furthermore, pathway-enrichment analyses on genes coherently modulated by the three MXenes showed only modest enrichment of immune-related pathways without a clear indication of activation or inhibition (Figure S10b–e, Supporting Information).

To further investigate the effects of the selected 2D materials on immune cell functionality, we monitored the expression of CD25 (α-chain of the IL-2 receptor) and CD69 (C-type lectin protein), which are late and early activation markers, respectively, by using flow cytometry after treatment with Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3 or Ta4C3, and Ti3C2 as an additional control (Figure S11, Supporting Information). No significant increase in the expression of the selected markers was observed, thereby confirming the overall neutral effect of the materials on immune cell function.

Collectively, these results indicated that MXenes can be detected in immune cells without affecting cell functionality, unlike other nanomaterials that can boost the immune system responses, altering cell functions.[28,40–43] The good biocompatibility of MXenes, is probably due to their favorable chemistry. In particular, Ti-, Nb-, Mo-, and Ta-based MXenes selected in this study, are all composed by biocompatible transition metals used in medical settings as metal alloy implants, contrast agents, and biomaterial surface coatings.[44] This positive behavior in biological systems has already been reported for other inorganic nanoparticles and nanostructured materials precisely formulated for various drug delivery and imaging applications.[45]

2.3. MXene Modularity Enables Their Customization for Optimal Cell Viability and Enhanced Cell Internalization

Importantly, for another 2D material, graphene, the lateral size has been shown to play an important role in cell viability and function.[39] Therefore, we investigated the effects of MXene lateral size on their uptake, viability, activation and detection profile. To this end, we produced Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3, and Ta4C3 MXenes with more similar lateral sizes (260, 240, and 160 nm, respectively) (Figure S12, Supporting Information) compared to those in the previous experiments (150, 370 and 810 nm). In Figure S13a, Supporting Information, for each material, we report the CyTOF ionization energy and the number of atoms detectable by mass cytometry. First, the cell viability of MXene-treated PBMCs was analyzed with a cisplatin protocol with CyTOF. We confirmed in Figure S13b, Supporting Information that all materials showed excellent biocompatibility (98.7, 98.8, and 98.7% in live cells for Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3, and Ta4C3, respectively). The percentage of cells positive for Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3, and Ta4C3 ranged between 40% for Ta4C3 and >90% for Mo2Ti2C3 and is reported for the total PBMCs (Figure S13c, Supporting Information) and all 15 immune subpopulations identified (Figure S13d, Supporting Information). The results confirmed that all 2D materials were naturally visible at the single-cell level and were able to interact with a vast number of immune cell subpopulations. Moreover, we demonstrated how the modulation of MXene lateral size by design can increase their detection signal and uptake. In addition, the time course analysis of MXene cell uptake after treatment of PBMCs for 1, 6, and 24 h demonstrated that even after a short exposure time (1 h), MXenes were internalized by immune cells (Figure S13e, Supporting Information). The median intensity of Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3 and Ta4C3 signals after 24 h is also reported as bar plots for total PBMCs (Figure S13f, Supporting Information) and all cell subpopulations (Figure S13g, Supporting Information).

2.4. MXene Cocktail Safety Profile Indicates No Effects on Cell Internalization Capability

Next, we evaluated whether MXenes might be combined to allow multiplexed detection of the materials. To this end, we incubated PBMCs with 150 μg mL−1 of a cocktail of the three MXenes with similar lateral size: Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3, and Ta4C3 (50 μg mL−1 each for 24 h); we then stained with 61-plex panel markers and assessed viability (Table S1, Supporting Information). We observed high biocompatibility of the materials even as a cocktail and at high concentrations (99.9% cell viability at 150 μg mL−1) (Figure 4a). The heat maps show the MXene detection at the single-cell level and their ability to interact with 15 immune cell subsets without affecting their viability (Figure 4b). Moreover, according to bar plots representing the mean intensity (Figure S14a, Supporting Information) and the percentage of positive cells to MXenes (Figure 4c) in total PBMCs after treatment for 24 h with the cocktail of MXenes with different sizes (Nb4C3-150 nm, Mo2Ti2C3-370 nm and Ta4C3-810 nm, 50 μg mL−1 each) or similar sizes (Nb4C3-260 nm, Mo2Ti2C3-240 nm and Ta4C3-160 nm, 50 μg mL−1 each), the differences in lateral size were found to modulate the binding, the uptake and consequently the detection of the materials with the cells, even when the MXenes were administered as a cocktail. The MXene cocktail with similar lateral sizes showed interaction with all immune cell subpopulations, as indicated by the percentage of MXene positive cells (Figure 4d), and a high biocompatibility regardless of the extent of interaction (Figure S14b, Supporting Information). In particular, Nb4C3 and Mo2Ti2C3, despite their lower mean signal intensity (MI) than that of Ta4C3 (Figure 4b), showed a similar higher percentage of single-cell positive cells, which were trackable in many immune subsets, whereas Ta4C3 was more selective for specific immune cell subpopulations (Figure 4d). tSNE analysis reporting all identified major immune subpopulations, MXene individual mean signal intensity, and a tSNE overlay representation of MXene MI in immune cell subpopulations are shown in Figure 4e,f,g, respectively.

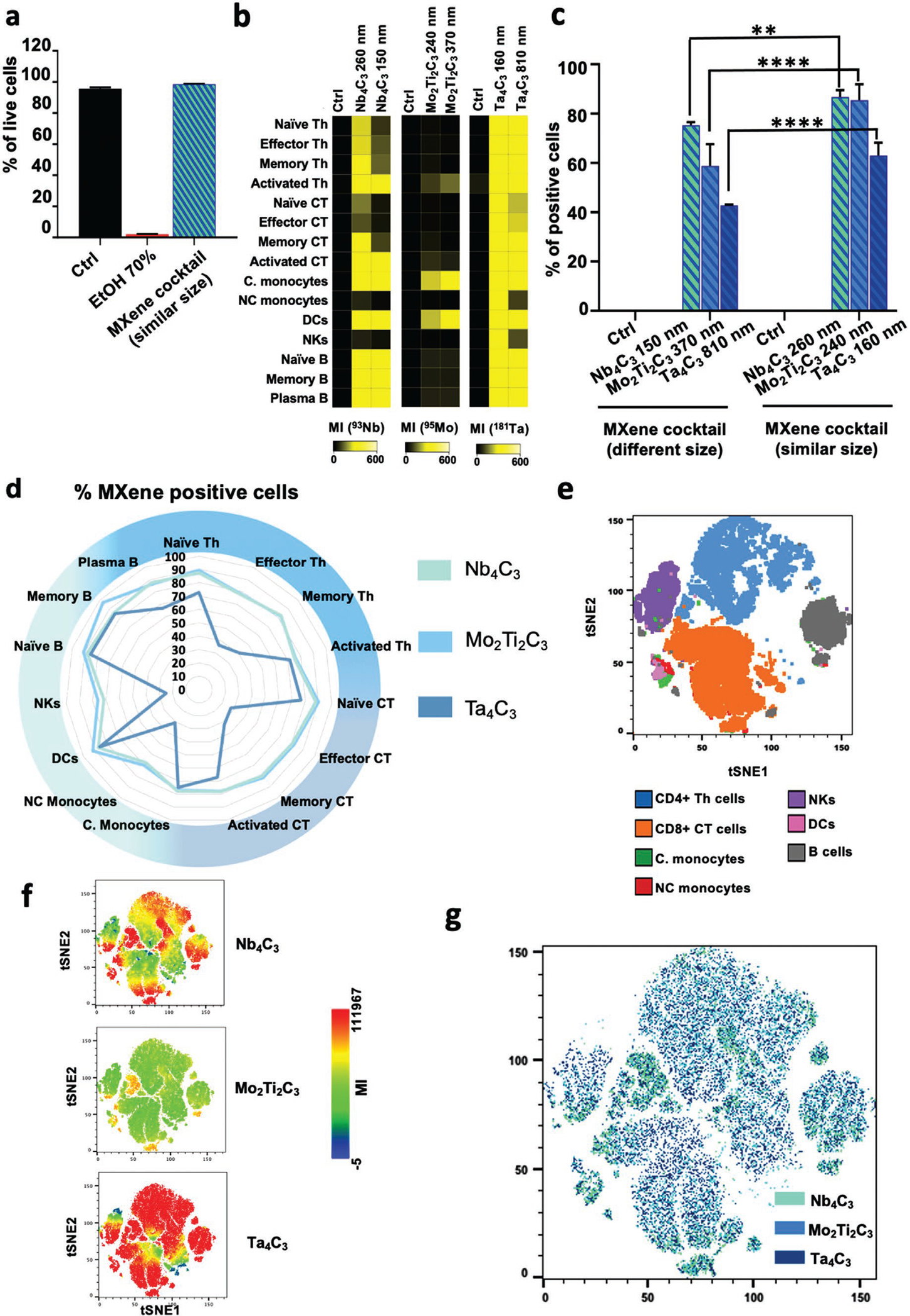

Figure 4.

MXene cocktail on human PBMCs: viability and detection. a–g) PBMCs were incubated with a cocktail of Nb4C3-260 nm, Mo2Ti2C3-240 nm, and Ta4C3-160 nm (50 μg mL−1 each) for 24 h and stained for mass cytometry analysis. Cell viability was analyzed using Cisplatin (Cis) reagent by CyTOF (a). Heat maps reporting the MXene median intensity for each specific channel in all the major immune subpopulations identified (b). Bar plots representing the percentage of positive cells to MXenes in total PBMCs after treatment for 24 h with the cocktail of MXenes with different size (Nb4C3-150 nm, Mo2Ti2C3-370 nm, and Ta4C3-810 nm; 50 μg mL−1 each) or similar size (Nb4C3-260 nm, Mo2Ti2C3-240 nm, and Ta4C3-160 nm; 50 μg mL−1 each) (c). d–g) PBMCs were incubated with a cocktail of Nb4C3-260 nm, Mo2Ti2C3-240 nm, and Ta4C3-160 nm (50 μg mL−1 each) for 24 h. Detection in 15 immune cell types was analyzed by CyTOF. The spider chart represents the MXene detection in 15 immune cell types expressed as percentage of positive cell for each immune cell subpopulation (d). tSNE analysis reporting all the major immune subpopulations identified (e). MXene mean signal intensity (MI) detected per single cell (f). tSNE overlay representation of MXene MI in immune cell subpopulations (g). All the experiments were performed in triplicate and shown as means ± SD. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001 (Two-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test).

We next performed a quantitative evaluation of MXenes at the single-cell level. To this end, we treated PBMCs with a cocktail of Nb4C3-260 nm, Mo2Ti2C3-240 nm, and Ta4C3-160 nm, and determined the number of 93Nb, 95Mo, and 181Ta atoms per cell from direct atom analysis in all PBMC subpopulations (Figure S15a, Supporting Information). In every cell type, a greater number of atoms per cell was observed for Ta4C3, followed by Nb4C3 and Mo2Ti2C3.

The dynamic range of 93Nb, 95Mo and 181Ta, and the mass spectra of Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3 and Ta4C3 determined with CyTOF solution mode are also reported in Figures S15b,c, Supporting Information, respectively. The CyTOF signal intensities are plotted against concentrations of the materials (Figure S15b, Supporting Information). The dynamic range of quantification of the materials was linear up to 50 μg mL−1. At the same concentrations, a difference of one or two orders of magnitude was observed in Mo2Ti2C3 intensity compared with Nb4C3 and Ta4C3 intensity, respectively.

2.5. MXenes Do Not Alter Dendritic Cell Interactions with T Cells

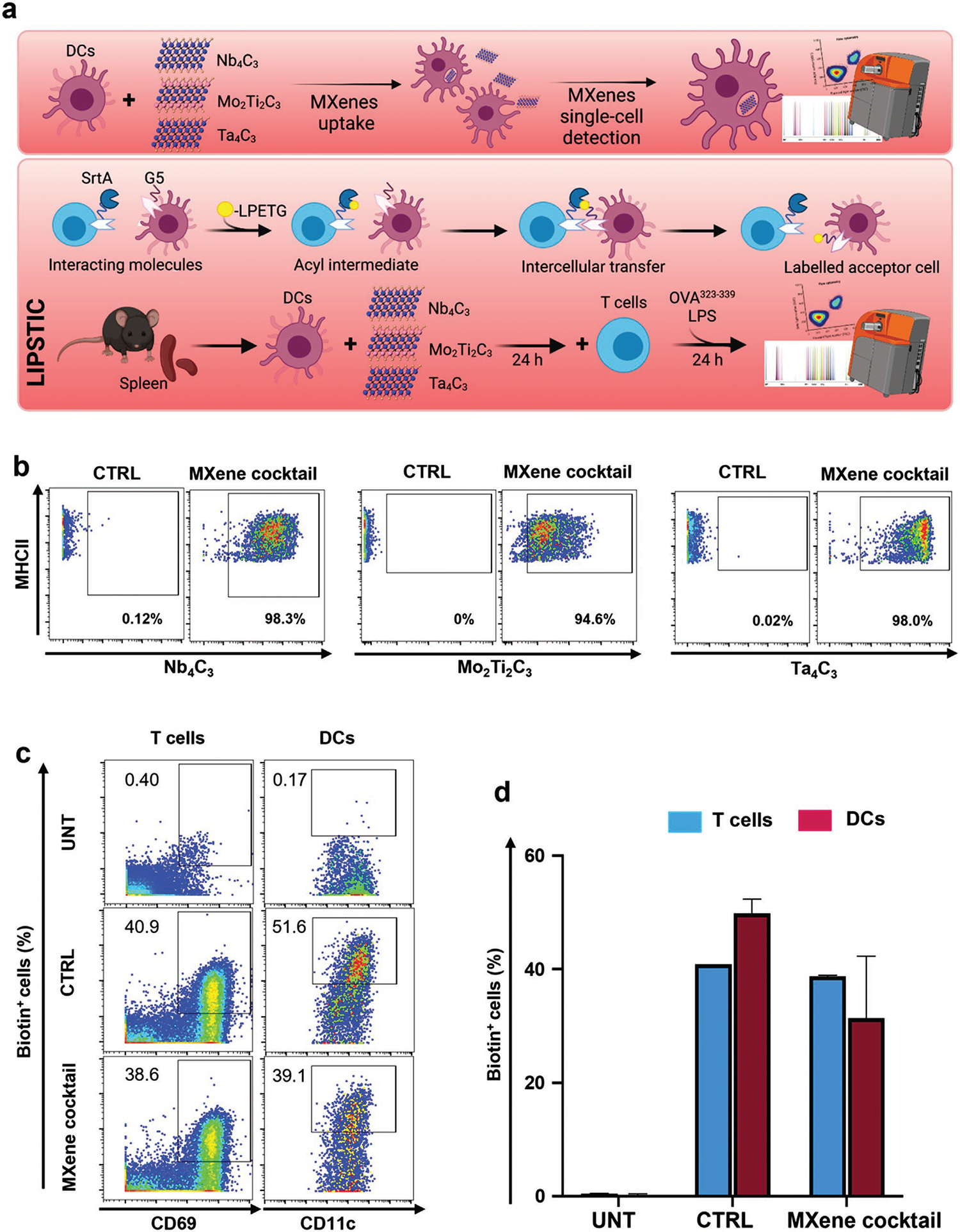

Because MXenes showed notable interactions with immune cells and dendritic cells in particular, we investigated the effects on the interaction between antigen-presenting DCs and T cells—an essential phenomenon underlying the activation of the immune response. To this end, we exploited the LIPSTIC[37] approach and coupled it with the CyTOF strategy for the analysis of cell–cell interactions after MXene treatment of DCs (Figure 5a and Figure S16, Supporting Information). This coupled approach has not previously been reported. We isolated DCs and naïve CD4+ T cells from Cd40G5/G5 and Cd40lgSrtA/Y CD4-Cre+ OT-II mice, respectively, so that the DCs constitutively expressed G5-CD40 protein, whereas the CD4+ T cells expressed CD40L-SrtA as well as a transgenic TCR (OT-II) that specifically recognized chicken ovalbumin derived epitope (OVA323–339 or OT-II peptide). According to previous findings,[37] CD4+ T cells present CD40L-SrtA on their membranes after cognate interaction with DCs. If a SrtA substrate (e.g., biotinylated LPETG) is provided, the enzyme transiently binds the substrate via the formation of an acyl intermediate, then mediates its transfer to nearby DCs expressing G5-CD40. In brief, this strategy allows for the identification and tracking of cells that undergo interactions, which are visualized as biotin+ populations. To assess whether MXene internalization by DCs might affect the above-mentioned process, we treated DCs from LIPSTIC model mouse spleens with the MXene cocktail for 24 h. At the end of the incubation, treated cells were washed and maintained in culture for an additional 24 h, in the presence of untreated T cells, OT-II peptide (9.25 μg mL−1) and LPS (10 μg mL−1) to allow for antigen presentation. The biotinylated SrtA substrate (biotin–LPETG) was provided during the final 30 min of incubation. CyTOF analysis was used to monitor MXene uptake by DCs (owing to the nanomaterials’ detectable masses and compatibility with the antibody panel reported in Table S2, Supporting Information) as well as substrate transfer between T cells and DCs (Figure 5a). As shown in Figure 5b, all materials were efficiently taken up by DCs (>90% MXene positive cells). The representative dot plots shown in Figure 5c demonstrated that LIPSTIC labeling in CD4+ T cells (left) and DCs (right) was not impaired by treatment with the cocktail of MXenes. Indeed, no significant difference in the percentage of biotin+ DCs and CD4+ T cells was observed when MXenes were provided, as highlighted by the grouped bar plots in Figure 5d. Overall, these results indicated that intercellular communication between DCs and T cells was preserved even after MXene uptake by DCs.

Figure 5.

Assessment of MXene cocktail impact on T cells-dendritic cells by a CyTOF-based enzymatic labeling LIPSTIC. a) Schematic representation of DC treatment and analysis (upper panel). DCs were treated with a cocktail containing 50 μg mL−1 of each MXene and cell uptake of each material was monitored by CyTOF analysis, thanks to their detectable masses (93Nb, 95Mo, and 180–181Ta). Schematic representation of “Labeling Immune Partnerships by SorTagging Intercellular Contacts” (LIPSTIC) approach (lower panel). The transpeptidase Sortase A (SrtA) and its target motif (G5) consisting of five N-terminal glycine residues are genetically fused to a receptor and a ligand of interest (in this case, CD40L and CD40). When a biotinylated substrate (i.e., a peptide containing the LPETG sequence) is provided, it transiently binds the SrtA via formation of an acyl intermediate. Upon interaction between the cells expressing the receptor and ligand, the SrtA catalyzes the transfer of the substrate onto the G5 motif. As the acceptor cell retains the label even after cells separate, the history of interaction is revealed by the presence of the biotinylated label. Experimental set-up: DCs and CD4+ T cells were respectively isolated from Cd40G5/G5 and Cd40lgSrtA/Y mouse spleens. DCs were treated with MXenes for 24 h, then further incubated with freshly isolated T cells for 24 h. b) Representative dot plots showing the uptake of MXenes by DCs following exposure to the MXene cocktail. The control was left in complete medium. c) Dot plots representing LIPSTIC labeling in CD4+ T cells (left) and DCs (right). The negative control (UNT) was not provided with the antigen nor treated with the nanomaterials; the positive control (CTRL) was provided with the antigen, but not the nanomaterials; the sample (MXene cocktail) was treated with Mxenes and supplemented with the antigen. d) Grouped bar plots reporting the percentage of biotin+ DCs and CD4+ T cells. All the experiments were performed in triplicate and shown as means ± SD. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001 (one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparison).

2.6. MXenes Are Detectable After In Vivo Administration

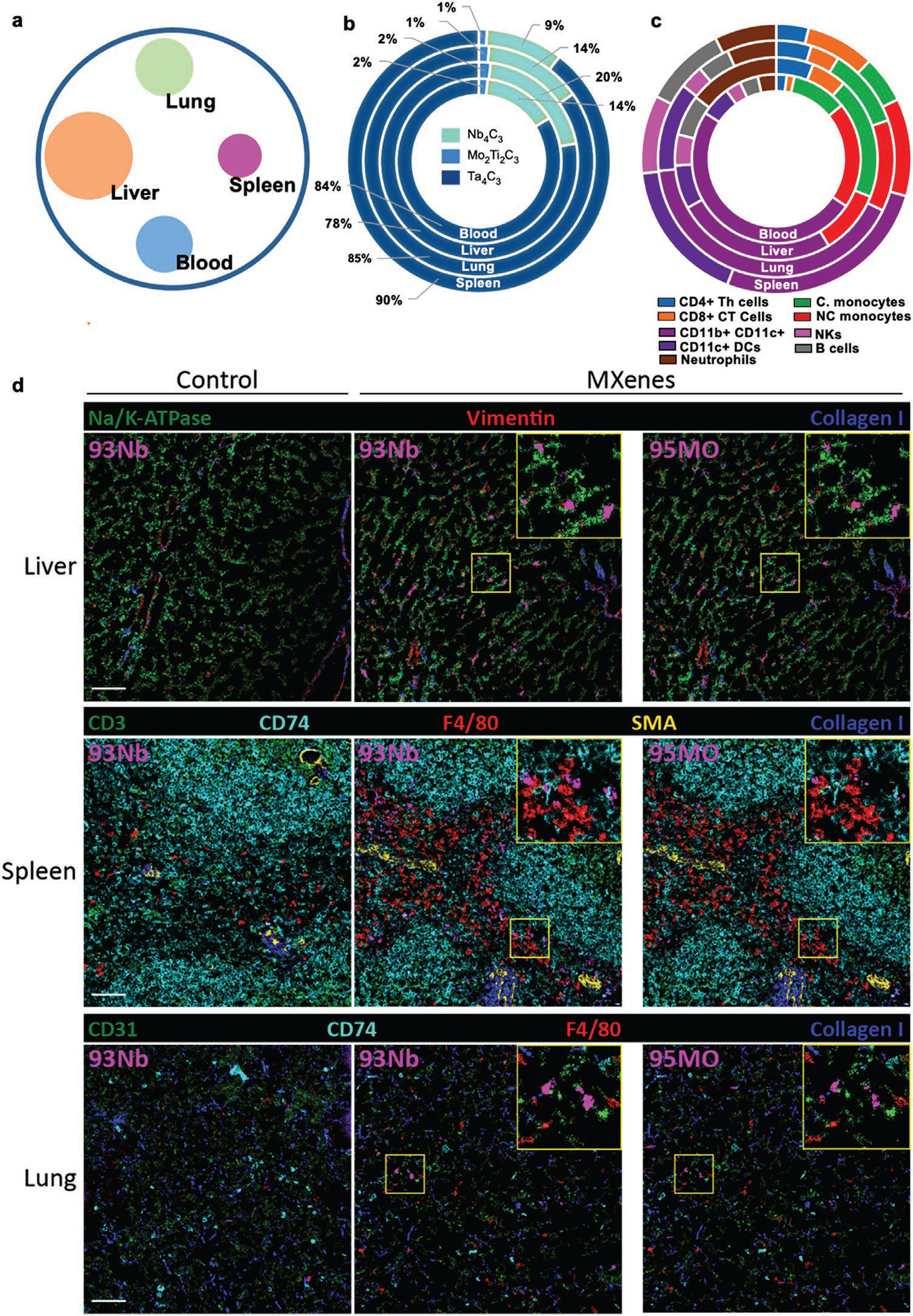

We then investigated the in vivo biodistribution and detection of the MXene cocktail at the tissue and single-cell level by CyTOF and MIBI-TOF. To this end, we I.V. injected C57BL/6J male mice with 20 mg kg−1 of a cocktail of MXenes (Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3, and Ta4C3) for 24 h (Figure 6). The liver, lung, spleen, and blood were subsequently analyzed, and all materials were well detectable at the tissue level and by multiple single-cell staining (Table S3, Supporting Information). The liver had the highest MXene cocktail signal intensity, followed by the blood, lung, and spleen (Figure 6a). In detail, Ta4C3 showed the highest signal, followed by Nb4C3 and Mo2Ti2C3, as revealed by the signal intensity deconvolution for each MXene in all organs analyzed (Figure 6b). The MXene MI signal intensity detected in each immune cell subpopulation analyzed per organ revealed that MXenes were detectable in all cell subsets analyzed, particularly in CD11b+ and CD11c+ dendritic cells (Figure 6c). Grouped bar plots showed the percentage of positive cells (Figure S17a, Supporting Information) and quantified MXene MI (Figure S17b, Supporting Information) for all immune cell subpopulations identified per organ. A representative contour plot of gated CD45+ cells, isolated from the livers of MXene-treated mice, is shown in Figure S18, Supporting Information. The in vivo administration of MXenes did not impair key parameters of whole blood in mice (Figure S19, Supporting Information), confirming the high biocompatibility.

Figure 6.

In vivo biodistribution of MXene cocktail at the tissue and single-cell level. C57B/6j male mice (n = 3) were injected I.V. with 20 mg kg−1 of a cocktail of MXenes (Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3 and Ta4C3) for 24 h. Subsequently, mice were sacrificed and blood, liver, lungs, and spleen were harvested and stained for mass cytometry analysis. a) Representative circle chart reporting the total MXene cocktail (Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3 and Ta4C3) signal intensity detected per organ. b) Signal intensity deconvolution for each MXene in all the organs analyzed. c) MXenes MFI signal intensity detected in each immune cell subpopulation analyzed per organ. d) MIBI-TOF imaging of tissues from control and MXene-injected mice stained with the indicated metal-labeled antibodies. MXene signal (purple) is detectable across all tissues in the niobium (93Nb) and molybdenum (95Mo) channels. Scale bar: 50 μm. All the experiments were performed in triplicate and shown as means ± SD.

Finally, to test whether MXenes might be detectable in intact tissues, we performed MIBI-TOF analysis on mouse organs (Figure 6d). We stained the tissues with a panel of nine metal-labeled antibodies, as detailed in Table S4, Supporting Information, and visualized them by MIBI-TOF, according to our previously reported protocols for tissue preparation.[24] A specific MXene signal was detected in all tissues, at both the niobium (93Nb) and the molybdenum (95Mo) channels, alongside the expected antibody staining (Table S4, Supporting Information), with no signs of tissue damage. The signal in the niobium channel was brighter, exhibiting higher sensitivity of detection of the presence of material. In particular, MXenes were detected mainly in the liver and spleen, followed by the lungs. The materials colocalized and also showed intracellular staining of non-immune cells, mainly in the liver.

Thus, we successfully identified the materials in intact mouse tissues, together with multiple antibody staining. Our findings may provide a 2D material detection solution for the large community of scientists performing in vivo pre-clinical studies.

This study indicated that LINKED can be readily applied to a wide variety of 2D materials to provide new insights into their toxicological profile and translate them into clinical nanosystems, because it: i) tracks 2D materials at the single-cell level, ii) represents a new frontier in 2D material biocompatibility assessment, iii) provides a versatile high-dimensional strategy to investigate 2D material functional interactions with a wide variety of cell populations simultaneously (exemplified here by human immune cells), and iv) promotes the development of new nano-based theranostic applications. LINKED’s 2D material detection design should substantially advance the state of the art and accelerate new advances and discoveries in nanotechnology and medicine.

3. Conclusions

We have presented evidence of label-free single-cell mass cytometry detection of MXenes containing specific transition metals. The 2D materials were reliably detected by imaging mass cytometry and multiplexed ion beam imaging MIBI-TOF, thus paving the way for their future detection in a wide variety of organs for a myriad of biomedical applications. This study provides the first demonstration of imaging of MXenes by using three different mass cytometry techniques in combination with 76 mass cytometry probes (antibodies). Moreover, we used the 93Nb and 95Mo channels, which have not previously been explored for commercial mass cytometry tags. We tested the MXenes simultaneously on 15 primary human immune cell subpopulations and successfully detected material uptake and cell interactions by CyTOF and imaging mass cytometry. Simultaneously, we demonstrated their excellent biocompatibility through high-dimensional immune and functional profiling by CyTOF. By using TEM, flow cytometry, Luminex assays and RNA-seq, we demonstrated the bio- and immunocompatibility of MXenes in terms of cytokine and chemokine production, expression of activation markers, and effects on whole-genome expression. We found that the modulation of MXenes’ lateral size can be used to increase their detection signal and uptake. We also demonstrated the possibility of detection and quantification of MXenes from a multimaterial mixture: a MXene cocktail. By adapting the innovative LIPSTIC approach, based on enzymatic labeling, for CyTOF, we showed that MXenes do not interfere with the interaction of two key players in the immune response: T cells and DCs. CyTOF on mice revealed the biodistribution of the MXene cocktail in vivo at the tissue and single-cell level, indicating MXene imaging properties in multiple organs while capturing immune cell internalization. Finally, we used multiplex ion beam imaging, which has not previously been used for nanomaterial detection, to detect the presence of MXenes in different organs, and observed no signs of tissue damage.

The possibility of detecting MXenes by multiple mass cytometry platforms at the single-cell and tissue levels is expected to tremendously advance preclinical research on this large and highly promising family of 2D materials. Importantly, the proposed strategy is not subjected to the classical limits of ordinary labeling methods or imaging approaches, and it has the potential to be further developed as a technological pipeline that could be extended to other classes of 2D materials with chemical properties similar to those tested in this study.

4. Experimental Section

Preparation and Characterization of MXenes—MAX Precursor Synthesis:

To synthesize the MAX precursors, Ta (−325 mesh, Alfa Aesar, 99.97%), TiC (<2 μm, Alfa Aesar, 99.5%), Nb (−325 mesh, Beantown Chemicals, 99.99%), Mo (−250 mesh, Alfa Aesar, 99.9%), Ti (−325 mesh, Alfa Aesar, 99.5%), Al (−325 mesh, Alfa Aesar, 99.5%), and graphite (−325 mesh, Alfa Aesar, 99%) powders were used. To produce Ti3AlC2, a 2:1:1 atomic ratio of TiC:Ti:Al (50 g total) was mixed. For Nb4AlC3, a 4:1.1:2.7 atomic ratio (10 g total) of Nb:Al:C was used. For Mo2Ti2AlC3, a 2:2:1.3:2.7 atomic ratio (10 g total) of Mo:Ti:Al:C was mixed; for Ta4AlC3, a 4:1:3 atomic ratio (7 g total) of Ta:Al:C was utilized. The powder mixtures were then mixed in a 2:1 ball:powder ratio with 5 mm alumina balls. The mixtures were ball milled at 60 rpm for 24 h prior to high-temperature annealing.

All high-temperature annealing reactions were conducted in a Carbolite furnace, with heating and cooling rate of 3 °C, and 200 cm3 min−1 flow of ultrahigh purity Ar (99.999%). For Ti3AlC2, the mixture was heated to 1400 °C for 2 h. For Nb4AlC3, the powders were heated to 1650 °C for 4 h. The Mo2Ti2AlC3 powder mixture was heated to 1600 °C for 4 h. Finally, to produce Ta4AlC3, the mixture was heated to 1400 °C for 8 h. After cooling, the porous compacts were milled using a TiN-coated milling bit and sieved through a 400-mesh sieve, producing powders with a particle size <38 μm. All experiments on this study were conducted on a single batch of MAX to eliminate any artifacts from variation between MAX synthesis batches.

MXene Synthesis:

To produce MXenes, HF (Acros Organics, 48–50 wt%; 29 m), HCl (Fisher Scientific, 37 wt%; 12 m), and deionized (DI) water (15 MΩ resistivity) was utilized. For all reactions, Teflon coated stir bars were used with a stirring rate of 300 rpm. Ti3C2Tx was produced by etching 1 g of Ti3AlC2 in a 1:3:6 volumetric ratio (20 mL total) of HF:H2O:HCl for 24 h at 35 °C. To synthesize Mo2Ti2C3Tx, 1 g of Mo2Ti2AlC3 was added to 20 mL of 48–50 wt% HF and stirred for 96 h at 55 °C. Nb4C3Tx was synthesized by adding 1 g of Nb4AlC3 to 20 mL of 48–50 wt% HF and stirred for 120 h 35 °C. Ta4C3Tx was synthesized from 1 g Ta4AlC3 in 20 mL of 48–50 wt% HF for 72 h at 35 °C. Tx represents the surface functional groups (═O, -OH, -F) on the MXene surface after etching and is omitted afterward for brevity. After the appropriate etching time, the mixtures were washed with DI water by centrifugation. The post-reacted mixtures were mixed with 150 mL DI H2O, then were centrifuged at 3,500 rpm for 10 min. The acidic supernatant was decanted, with the multilayer MXene remaining as the sediment. New DI H2O was added, with the sediment redispersed. This process was repeated eight times. This ensured that the sample was fully neutral, and any excess adsorbed acid was removed.

All multilayer MXenes in this study were delaminated in 20 mL of a 5 wt% TMAOH solution (TMAOH; Sigma Aldrich, 25 wt% in H2O). The MXenes were stirred for 12 h at 300 rpm at 35 °C. After stirring, the samples were placed into 50 mL centrifugation tubes. DI water was added, and the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant was decanted off, and the MXene was redispersed in fresh DI water. This procedure was repeated five times to ensure that all excess TMAOH was removed. Following this last cycle, the MXene was redispersed in 50 mL DI water, then was centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected, then centrifuged again at 3500 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was carefully decanted for use. This ensured that only single-flake MXene remained in the solution.

A small fraction of this solution was then vacuum filtered on Celgard membranes (64 nm pore size, 3501 coated polypropylene), which were first washed with ethanol, then deionized water, to produce free-standing films for X-ray diffraction (XRD). By measuring the weight of the produced films (and considering the solution volume added), the concentration of the films was determined.

MXene Characterization:

XRD patterns of the powders and films were collected on a Rigaku Smartlab (40 kV and 30 mA) diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation. The conditions were as follows: i) for the MAX powder, step scan 0.02, 3–90 (2θ), step time of 1 s; ii) for the MXene films, a step scan of 0.03, 3–70 (2θ), step time of 0.5 s was used. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was conducted on a dual-beam focused ion beam (Strata DB235, FEI). The MXene flakes were drop-cast onto a porous alumina substrate. Pt was deposited onto the flake and substrate to minimize charging. DLS (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments) was performed to analyze the size of the MXene flakes. Three measurements were taken of each sample and the average value was reported. Characterization of the MXenes is reported in Figure S1, Supporting Information. All materials were tested for possible contamination as previously reported.[14,46]

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs):

PBMCs were harvested from ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA)-venous blood from informed healthy donors (25–50 years old) using a Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare, CA, USA) standard separation protocol. Informed signed consent was obtained from all the donors. Cell separation and experiments were performed immediately after blood drawing. PBMCs were cultured in 24-well plates in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies), supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies). At least 1 × 106 cells/sample in each experiment were used. Experiments were carried out using multiple healthy donors and technical triplicate.

Calcein AM/Ethidium Homodimer-1 Assay:

PBMCs were treated for 24 h with different concentrations of (12.5, 25, 50, and 100 μg mL−1) of each material and calcein AM/ethidium homodimer-1 staining was performed by incubating cells with 2 μmol L−1 calcein AM and 5 μmol L−1 ethidium homodimer (Live/Dead Viability/Cytotoxicity kit, Invitrogen) for 45 min at 37 °C in the dark. Ethanol 70% was used as a positive control, while samples incubated with medium alone were used as negative controls. The assay discriminates live from dead cells by simultaneously staining with green-fluorescent calcein-AM (excitation wavelength of 485 nm and emission wavelength of 530 nm) to indicate intracellular esterase activity and red-fluorescent ethidium homodimer-1 (excitation wavelength of 530 nm and emission wavelength of 645 nm) to indicate loss of plasma membrane integrity. Plasma membrane integrity and esterase activity were measured by a Fluorescence Microplate Reader (TECAN infinite M200PRO, Switzerland).

Cytotoxicity and Cell Activation by Flow Cytometry:

PBMCs were treated with increasing concentrations of each material (i.e., 25, 50 and 100 μg mL−1) for 24 h and Fixable Viability Stain 780 (FVS780, BD Horizon™) was used to discriminate viable from non-viable cells. Staining was performed in the dark for 30 min. Ethanol at 70% was used as a positive control, while samples incubated with medium alone were used as negative controls. Cells were processed by flow cytometry (LSR Fortessa X-20, BD Bioscience, CA, USA), while data were analyzed by FlowJo Software as previously reported.[47–49]

In addition, PBMC activation was analyzed after treatment with each material (50 μg mL−1) for 24 h. Cells were stained to identify immune activation markers. CD25 and CD69 (PE-conjugated anti-CD25, M-A251 clone; FITC-conjugated anti-CD69, FN50 clone; BD Bioscience, CA, USA) were used as activation markers. Staining was performed in the dark for 20 min. LPS (2 μg mL−1, Sigma) was used as positive control. Cells were processed by flow cytometry (FACS Canto II, BD Bioscience, CA, USA), and data were analyzed by FlowJo Software as previously reported.[47–49]

Single-Cell Mass Cytometry Analysis (CyTOF):

Single-cell mass cytometry analysis was carried out using isolated PBMCs, obtained as previously reported. PBMCs were cultured in 6-well plates at a concentration of 4 × 106 cells per well and treated with 50 μg mL−1 of the materials for 24 h at 37 °C. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) 0.5 μg mL−1 (Sigma–Aldrich, Missouri, USA), ethanol for cell biology (EtOH 70%), and untreated cells were used, respectively, as positive and negative controls.

Six hours before the end of the treatment, cells were incubated with Brefeldin A (Invitrogen, CA, USA) to a final concentration of 10 μg mL−1. After the incubation time, cells were washed with a sterile solution of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), EDTA 0.5 m and 5% of fetal calf serum (FCS). Cells were then combined using Cell-ID 20-Plex Pd Barcoding Kit (Fluidigm, CA, USA). The barcoded sample was stained with Cell-ID Cisplatin (Fluidigm, CA, USA) 1:1000, Maxpar Human Peripheral Blood Phenotyping and Human Intracellular Cytokine I Panel Kits (Fluidigm, CA, USA) following the manufacturer staining protocols.

In synthesis, to guarantee a uniform cell labeling with the palladium barcode, cells were fixed and permeabilized by means of 1X Fix I Buffer and 1X Barcode Perm Buffer. After the barcoding step, samples were pooled together and resuspended in Maxpar Cell Staining Buffer into a 5 mL polystyrene round-bottom tube.

The surface marker antibody cocktail (1:100 dilution for each antibody, final volume 800 μL) was added to the tube. The sample was mixed and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After incubation, the sample was washed twice with Maxpar Cell Staining Buffer. Cells were then fixed by incubating the sample with 1 mL of 1.6% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Subsequently, cells were washed twice with Maxpar Perm-S Buffer and centrifuged for 10 min at 1000g. Cells were then resuspended in 400 μL of Maxpar Perm-S Buffer and incubated for other 30 min with cytoplasmic/secreted antibody cocktail (1:100 dilution for each antibody, final volume 800 μL). At the end of the incubation, cells were washed twice with Maxpar Cell Staining Buffer and stained overnight with Cell-ID Intercalator-Ir solution at the final concentration of 125 × 10−9 m. Prior to data acquisition, the samples were washed twice with Maxpar Cell Staining Buffer, resuspended with 2 mL of Maxpar water and filtered using a 0.22 μm cell strainer cap to remove possible cell clusters or aggregates. Data were analyzed using mass cytometry platform CyTOF2 (Fluidigm Corporation, CA, USA). Table S1, Supporting Information shows the antibody panel used for cell staining following the same procedure as above described.

Gating Strategy and Data Analysis and Visualization:

The CyTOF data analysis was carried out accordingly to the methods described by Orecchioni et al.[28] and Bendall et al.[50] Briefly, normalized, background subtracted FCS files were uploaded into Cytobank for the analysis. The gating strategy excluded doublets, cell debris, and dead cells by means of Cell-ID Intercalator-Ir and LD. Specific PBMC subsets and subpopulations were assessed as reported in Figure S4, Supporting Information, in detail: T cells (CD45+ CD19− CD3+), T helper (CD45+ CD3+ CD4+), T cytotoxic (CD45+ CD3+ CD8+), T naive (CD45RA+ CD27+ CD38− HLADR−), T effector (CD45RA+ CD27− CD38− HLADR−), and activated (CD38+ HLADR+), B cells (CD45+ CD3− CD19+), B naive (HLADR+ CD27−), B memory (HLADR+ CD27+), plasma B (HLADR− CD38+), NK cells (CD45+ CD3− CD19− CD20− CD14− HLADR− CD38+ CD16+), Classical monocytes (CD45+ CD3− CD19− CD20− HLADR+ CD14+), Intermediate monocytes (CD45+ CD3− CD19− CD20− HLADR+ CD14dim CD16+) Non classical monocytes (CD45+ CD3− CD19− CD20− HLADR+ CD14− CD16+), and DC (CD45+ CD3− CD19− CD20− CD14− HLA− DR+ CD11c+ CD123−). The heat map visualization, realized with Cytobank, compared marker fluorescence of the treated populations with mean fluorescent intensity versus the untreated control. tSNE tool was applied. tSNE, a cytometry analysis tool implemented in Cytobank, uses t-stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) showing single cells in a two- or three-dimensional plot, according to their relationships. Nine cell surface markers were exploited in order to produce the tSNE map: CD3, CD4, CD8a, CD11c, CD14, CD16, CD19, CD20, CD123, and HLADR.

Cytokine data analysis was achieved using the tSNE tool. Plots showing the expression intensity of the analyzed cytokines (IFNγ, IL-2, IL4, IL-5, IL17a, IL17f, IL6, MIP1β, TNFα, Perforin, and GrB) and heat maps of mean marker expression ratio for all cytokines were realized.

Cellular Detection of Material Uptake by IMC:

Metal-labeled antibodies were provided by Fluidigm, from the standard CyTOF catalog (http://maxpar.fluidigm.com/product-catalog-metal.php). Metal-labeled antibody cocktails were prepared in 0.1% Tween-20, 1% BSA in PBS. All samples, were first blocked with 1% BSA and 0.2 mg mL−1 mouse IgG Fc fragment (Thermo Scientific) in PBS for 30 min and then incubated with antibody cocktail for 1.5 h at RT, followed by washing with PBS and staining with DNA intercalator Ir-191/193 (Fluidigm) and CD45 (HI30)-89Y (Fluidigm) for 30 min. Slides were again washed with PBS and rinsed with ddH20 for 5 s and dried overnight at room temperature prior to IMC analysis.

ROIs of 500×500 μm undergo laser ablation aerosolizing a 1 μm2 area per pulse (200 Hz), followed by ionization and quantification in the CyTOF Helios instrument. Ion mass data is collected for each pulse and processed to render images for each individual channel at 1 μm resolution, where the intensity of each pixel corresponds to the ion count value. Raw data were analyzed using Fluidigm MCD viewer program.

Cellular Detection of Material Uptake by TEM:

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis, samples were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m sodium cacodylate buffer pH 7.4 ON at 4 °C. The samples were postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide plus potassium ferrocyanide 1% in 0.1 m sodium cacodylate buffer for 1 h at 4 °C. After three water washes, samples were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series and embedded in an epoxy resin (Sigma-Aldrich). Ultrathin sections (60–70 nm) were obtained with an Ultrotome V (LKB) ultramicrotome, counterstained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and viewed with a Tecnai G2 (FEI) transmission electron microscope operating at 100 kV. Images were captured with a Veleta (Olympus Soft Imaging System) digital camera.

Luminex:

To evaluate the impact of MXenes on cytokine release by PBMCs, cells were incubated for 24 h with 50 μg mL−1 of the materials. LPS, 2 μg mL−1 (Sigma) was used as positive control, while samples incubated with medium alone were used as negative controls. Supernatants were collected and analyzed by Luminex technology using Bio-Plex Pro Human Chemokine 40-plex Panel (Bio-Rad) to measure C-C Motif Chemokine Ligand (CCL) 21 (CCL21), chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL) 13 (CXCL13), CCL27, CXCL5, CCL11, CCL24, CCL26, C-X3-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 1 (CX3CL1), CXCL6, granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), CXCL1, CXCL2, CCL1, interferon gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, CXCL8, IL-10, IL-16, CXCL10, CXCL11, CCL2, CCL8, CCL7, CCL13, CCL22, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), CXCL9, CCL3, CCL15, CCL20, CCL19, CCL23, CXCL16, CXCL12, CCL17, CCL25 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. 5-parameter-Logistic regressions with a power low variance weighing were calculated for each cytokine standard with a recovery range of 70–130% using Bioplex Manager V6.2 (BioRad). Concentration falling within the recovery range, expressed in pg mL−1 were extrapolated from the median fluorescence intensity of each cytokine bead set. For analytes above or below the standard recovery ranges, upper and lower limits of quantification computed from the standard curves were substituted. Data were then Log2 transformed and compared across experiments by fitting a general analysis of variance (ANOVA) model with contrast between groups; p values were corrected using Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate, FDR; statistically significant p value cutoff was set at FDR p < 0.05. Values out of range, “00R>” or “00R<”, were replaced, respectively, with the maximum or minimum value for the analyte across samples, indicated with (*), or, when not possible, with the upper (ULOQ) or lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) for that analyte, respectively.

mRNAsequening—RNA Extraction and QC:

To evaluate the impact of MXenes on PBMCs, cells were incubated for 24 h with 50 μg mL−1 of the materials. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS 2 μg mL−1, Sigma) and Concanavalin A (ConA, 10 μg m−1, Sigma) were used as positive controls, while samples incubated with medium alone were used as negative controls. After treatment, the cell suspension was transferred from each well into RNase-free 1.5-mL tubes and cells were washed two times with 1 mL of PBS. Cells were then resuspended in 350 μL of RLT Buffer freshly additionated with 1% b-mercaptoethanol and stored at −80 °C.

RNA was extracted using the RNAeasy Kit (Qiagen. The methodology has been followed detail in kit instruction. RNA was quantitated on a NanoDrop (ThermoFisher) and QCed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). All samples had a RIN > 7.5.

Normalization and Statistical Analysis:

mRNA-sequencing was performed using QuantSeq 3′ mRNA-Seq Library Prep Kit FWD for Illumina (75 single-end) with a read depth of average 8.76 m, and average read alignment of 79.60%. Single samples were sequenced across four lanes, and the resulting FASTQ files were merged by sample. All FASTQ passed QC and were aligned to the reference genome GRCh38 using STAR 2.7.9a. BAM files were converted to a raw counts expression matrix using HTSeq-count. Then “betweenLaneNormalization” normalized data (using EDAseq omitting GC and transcript length correction (not applicable for 3’mRNA-seq)) was quantiled normalization and log2 transformed (total transcript mapped to genes = 19 959 genes). All downstream analysis was performed using RStudio (Version 4.1., RStudio Inc.). Differential gene expression analysis was performed using Limma via Bioconductor package “limma v. 3.46.0” [PMID 25605792] with Benjamini-Hochberg (B-H) FDR, using different FDR p values cutoffs (e.g., 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1). In each comparison, genes with rows sum equal to zero were removed. Global transcriptional differences between samples were assessed by principal component analysis using the “prcomp” function. To illustrate the differentially expressed genes overlap between the conditions, R CRAN package “VennDiagram v. 1.6.20” was used. Differentially expressed genes were then plotted in a heatmap using Bioconductor package “ComplexHeatmap v. 2.6.2”. List of differentially expressed genes were uploaded to Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA; Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA) to detect modulated pathways (IPA canonical pathways).

MXene Quantification Determined by CyTOF Solution Mode:

Dynamic range of 93Nb, 95Mo, and 181Ta was determined by CyTOF solution mode. The dynamic range of MXenes was evaluated by mass cytometry CyTOF Helios system at Fluidigm Canada, solution mode). Nb4C3-260 nm, Mo2Ti2C3-240 nm, and Ta4C3-160 nm 50 μg mL−1 solutions were diluted 1:3 in order to create an ELISA curve (0.00, 0.0076, 0.023, 0.068, 0.2, 0.61, 1.85, 5.55, 16.6, and 50 μg mL−1).

Number of Nanomaterials per Cell Calculation:

The mean 93Nb, 95Mo and 181Ta ion intensity within a specific cell population measured by mass cytometry is addressed as the “mean dual counts”. This value is proportional to the number of 93Nb, 95Mo, and 181Ta atoms per cell and it is the product of the integral over time of detector intensity multiplied by the dual count coefficient, respectively, of 93Nb, 95Mo, and 181Ta.

The conversion of dual counts to the number of niobium, molybdenum and tantalum atoms per cell was determined using the calculations reported by Yang et al, Nat com, 2017 as follows:

Number of 93Nb, 95Mo and 181Ta atoms per cell = 93Nb, 95Mo or 181Ta/193Ir transmission factor.

Since the transmission coefficient for 93Nb, 95Mo or 181Ta cannot be directly assessed in the cytometer, but can be measured for 193Ir, characterized by a degree of ionization similar to the one of MXenes (Ir and MXenes have ionization energies of 8.9760 and 6.7589 (93Nb), 7.0924 (95Mo), 7.5496 (181Ta), eV, respectively). The 193Ir transmission coefficient was calculated dividing the dual counts of 193Ir detected for the instrument tuning solution by the number of 193Ir atoms introduced in the 0.25 p.p.b. Ir tuning solution (Fluidigm CAT#201072) as reported below:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Using the variables tuning solution Ir concentration (2.5 × 10−13 g μL−1), flow rate (0.75 μL s−1 for CyTOF2 or 0.5 μL s−1 for Helios), the integration time (CyTOF2: 2.666 s; Helios: 4 s), the natural abundance of 193Ir (0.627), Avogadro’s number 6.02 × 1023, and isotope mass (193 g mol−1). Finally, the number of NPs per cell was calculated by the number of atoms per cell divided by the number of atoms per NP.

LIPSTIC Experiment:

Cd40G5/G5 and Cd40lgSrtA/Y, CD4-Cre+, OT-II mice were housed in the SPF animal facility of the University of Padova, in accordance with institutional and ethical regulations. 5 to 12 weeks-old male and female mice were used in these experiments. No ethical approval was needed for these experiments, which were all ex vivo.

Isolation of Splenic Dendritic Cells and Naïve CD4+ T cells:

To isolate dendritic cells, spleens were collected, incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in RPMI, 2% FBS, 20 mm HEPES, 400 U mL−1 type-IV collagenase (Sigma Aldrich) and disrupted to generate single-cell suspensions. Red-blood cells were lysed with ACK buffer (NH4Cl 8.024 mg L−1; KHCO3 1.001 mg L−1; EDTA Na2·2H2O 3.722 mg L−1), and the resulting cell suspensions were filtered through a 70 μm mesh into PBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA and 2 × 10−3 m EDTA (PBE). DCs were obtained by magnetic cell separation (MACS) using anti-CD11c beads (Miltenyi Biotec), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

To isolate naïve CD4+ T cells, spleens were harvested and single-cell suspensions were generated as described above. CD4+ T cells were then obtained by using the naïve CD4+ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec) as per manufacturer’s instructions.

Labeling Immune Partnerships by SorTagging Intercellular Contacts (LIPSTIC):

Splenic DCs were isolated from Cd40G5/G5 mice as described above, seeded into round-bottom 96-well plates and treated with MXene cocktail (Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3, and Ta4C3, 50 μg mL−1 each) for 24 h. After the incubation time, cells were washed two times to remove the nanomaterials dispersed in the media. Treated DCs were incubated with untreated naïve CD4+ T cells, freshly isolated from the spleens of Cd40lgSrtA/Y, CD4-Cre+, OT-II mice (2 × 105 total cells per well, 1:1 ratio). Medium was supplemented with 10 × 10−6 m OTII peptide (OVA329–337) and 10 μg mL−1 LPS, before being incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. 30 min before the end of the incubation, the biotin–LPETG was added to each well at a final concentration of 10 × 10−6 m in complete medium. At the end of the incubation, cells were washed three times with Maxpar PBS (Fluidigm) to remove excess biotin–LPETG substrate before CyTOF staining.

To allow dead cells discrimination, cells were resuspended in 500 μL Maxpar PBS containing 1 × 10−6 m 194Pt Cisplatin (Fluidigm), gently vortexed and incubated for 5 min at RT. Cells were then washed with Maxpar Cell Staining buffer and incubated with anti CD16/32 (BioXcell) for 10 min, at RT. After incubation, samples were stained for cell surface markers for 30 min at RT in Maxpar Cell Staining Buffer. The pool of antibodies used for the staining is reported in Table S2, Supporting Information. Cells were then washed twice in Maxpar Cell Staining buffer, before being fixed by adding 16% paraformaldehyde to a final concentration of 1.6%, for 10 min at RT. DNA staining was performed by incubating the cells in Maxpar Fix and Perm buffer supplemented with 1:1000 191Ir/193Ir Cell-ID Intercalator (Fluidigm), for 18 h at 4 °C. In the end, samples were acquired by using mass cytometry platform CyTOF2 (Fluidigm Corporation, CA, USA).

In Vivo Biodistribution:

For the in vivo biodistribution experiments 3 male C57BL/6J (cat. #000664) mice per group were used. Mice were injected I.V. retro-orbitally with a 100 μL MXene cocktail (Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3 and Ta4C3, 20 mg g−1 each in sterile PBS) or only sterile PBS. After 24 h mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation followed by blood withdrawal via cardiac puncture before further organ and tissue dissection. All experiments followed guidelines of the La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) Animal Care and Use Committee. Approval for use of rodents was obtained from LJI according to criteria outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals from the National Institutes of Health.

Blood, spleen, lungs, and livers where harvested and single cell suspension isolated by following procedures:

Blood was withdrawn via cardiac puncture and collected in EDTA-coated tubes (Sarstedt). Erythrocytes were lysed using 1x RBC lysis buffer (Biolegend) for 10 min at room temperature and the cell suspension was washed twice with PBS. Cells were kept in PBS with 2% FBS on until further staining and CyTOF analysis.

Spleens were homogenized through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences), washed with 4 °C cold PBS and red blood cell lysis for 3 min at RT using 1× RBC lysis buffer (Biolegend). Splenocytes were washed with PBS and kept in PBS with 2% FCS, and kept on ice until further staining and CyTOF analysis.

Both lobes of a lung were rinsed with ice-cold PBS and transferred to a gentleMACS C tube (Miltenyi Biotec) and digested with 2 mg mL−1 collagenase D and 80 U mL−1 DNase I for 30 min at 37 °C on a gentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec). After digestion, lung cells were kept on ice in PBS with 2% FBS until further staining and CyTOF analysis.

The liver was dissected and homogenized through a 100 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences). After washing in PBS, the liver cell pellet was resuspended in 10 mL of 37.5% percoll solution and centrifuged at 900 × g for 25 min without acceleration and brake. The cell pellet was collected, washed with PBS, and kept on ice in PBS with 2% FBS until further staining and CyTOF analysis.

Table S3, Supporting Information shows the antibody panel used for cell staining following the same procedure as described above.

In Vivo Blood Cell Counts:

Male C57BL/6J mice (8–10 weeks old) were injected as previously described with vehicle (Saline) or MXene cocktail and housed for 24 h. Mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation; whole blood was then collected in EDTA tubes via cardiac puncture. Blood leukocyte counts were determined by HemaVet 950 (Drew Scientific).

MIBI-TOF:

For the in vivo MIBI-TOF analysis 3 male C57BL/6J (cat.# 000664) mice per group were used. Mice were injected I.V. retro-orbitally with a 100 μL MXene cocktail (Nb4C3, Mo2Ti2C3, and Ta4C3, 20 mg g−1 each in sterile PBS) or only sterile PBS. After 24 h mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation followed by blood withdrawal via cardiac puncture before organ and tissue dissection. Spleen, Liver, Lungs and Kidneys were harvested and fixed for 24 h in a solution containing paraformaldehyde (PFA) 4%. After 24 h fixation, organs were washed and kept in 70% EtOH before paraffin embedding.

Antibody Conjugation:

A summary of antibodies, staining concentrations and conjugated metals can be found in Table S4, Supporting Information. Metal-conjugated primary antibodies were prepared as described previously,[51] using antibody conjugation kits from Ionpath Inc.

MIBI-TOF Staining:

Staining was performed as previously described.[52] Briefly, tissue sections (4 μm-thick) were cut from FFPE tissue blocks and mounted on silanized-gold slides (Ionpath Inc.). Slide-tissue sections were baked at 70 °C for 20 min. Tissue sections were deparaffinized with 3 washes of fresh-xylene. Tissue sections were then rehydrated with successive washes of ethanol 100% (2×), 95% (2×), 80% (1×), 70% (1×), and distilled water. Washes were performed using a Leica ST4020 Linear Stainer (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany) The sections were then immersed in epitope retrieval buffer (Antigen Retrieval Solution, Tris-EDTA, pH 9, abcam) and incubated at 97 °C for 40 min using Lab vision PT module (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Slides were washed with TBS with Tween 20 buffer (TBST, Ionpath Inc.). Sections were then blocked for 1 h with 3% v/v donkey serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Metal-conjugated antibody mix was prepared in 3% v/v donkey serum according to antibody concentrations in Table S4, Supporting Information, and filtered using centrifugal filter, 0.1 μm PVDF membrane (Ultrafree-MC, Merck Millipore, Tullagreen Carrigtowhill, Ireland). Two panels of antibody mix were prepared: with the first, slides were incubated overnight at 4 °C in humid chamber; and with the second, slides were incubated the next morning for 1 h at room temperature (according to incubation conditions for each antibody in Table S4, Supporting Information). Slides were then washed twice 5 min in TBST wash buffer and fixed for 5 min in diluted glutaraldehyde solution 2% (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA, USA) in PBS-low barium. Tissue sections were then dehydrated with successive washes of Tris 0.1 m (pH 8.5), (3×), distilled water (2×), and ethanol 70% (1×), 80% (1×), 95% (2×), 100% (2×). Slides were immediately dried in a vacuum chamber for at least 1 h prior to imaging.

Imaging and Image Processing:

Imaging was performed using the MIBIscope system (Ionpath Inc.). The MXene signal was detected for niobium and Molybdenum at the 93Nb and 95Mo channels respectively. MXene signal at the tantalum (181Ta) channel was also observed and matched the location of the signals in 93Nb and 95Mo. Notably, the slides used for MIBI-TOF are coated with tantalum and as such any holes in the tissue, where bare slide is exposed, will give a high signal for Ta.[53] This bare-slide signal may be difficult to decouple from the MXene signal if 181Ta will be used on its own. Additional work is needed to determine the best use of 181Ta as a reporter using the current methodology. Following image acquisition, output multidimensional TIFF images were processed for background subtraction, noise removal and aggregate removal using MAUI.[53]

Statistical Analysis:

All values are expressed as mean ± S.D. Comparison between groups was performed by one-way ANOVA, followed by a Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparison where data was normally distributed. Data that did not follow the normal distribution were statistically analyzed by Kruskall–Wallis ANOVA. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. Sample size for all the experiments was set as n = 3 biological replicates if not otherwise specified, based on anticipated effect size, anticipated standard error as determined by the experience with previous analysis of human- and mice-derived cells and organs, analysis of statistical power, and availability of reagent (i.e., nanomaterials, except where otherwise stated in the text). Where permitted by availability of reagents and instruments, additional replicates were obtained. Statistical analysis was performed in Excel using the Real Statistics Resource Pack and in GraphPad Prism 9.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

L.G.D., D.B., and L.F. gratefully acknowledge financial support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 734381 (CARBO-IMmap). L.G.D., Y.G., and L.F. acknowledge funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 101029140 (SEE). The work of D.B., L.F., D.R., A.H. and J-C.G was supported by Sidra Medicine Internal Funds (SDR400025). Y.G. gratefully acknowledge financial support from the US National Science Foundation (DMR-2035007). The authors thank Dr. Federico Caicci at the TEM Core Facility at the University of Padua, for expert assistance with analysis. L.K. is supported by the Enoch Foundation Research Fund, the Center for New Scientists at the Weizmann Institute of Science and grants funded by the Schwartz/Reisman Collaborative Science Program, European Research Council (94811), the Israel Science Foundation (2481/20, 3830/21) within the Israel Precision Medicine Partnership program and the Israeli Council for Higher Education (CHE) via the Weizmann Data Science Research Center. L.G.D. thanks Prof. Bengt Fadeel for the useful discussions and Prof. Fabio Di Lisa for the kind hospitality in his laboratory during the Veneto pandemic-related early lockdown.

Open access funding provided by Universita degli Studi di Padova within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Laura Fusco, ImmuneNano Laboratory, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Padua, Padua 35129, Italy; A. J. Drexel Nanomaterials Institute and Department of Materials, Science and Engineering, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA; Human Immunology Division, Translational Medicine Department, Sidra Medicine, Doha 26999, Qatar.

Arianna Gazzi, ImmuneNano Laboratory, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Padua, Padua 35129, Italy; Department of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Trieste, Trieste 34127, Italy.

Christopher E. Shuck, A. J. Drexel Nanomaterials Institute and Department of Materials, Science and Engineering, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

Marco Orecchioni, La Jolla Institute for Immunology, San Diego, CA 92037, USA.

Dafne Alberti, Laboratory of Synthetic Immunology, Oncology and Immunology Section, Department of Surgery Oncology and Gastroenterology, University of Padua, Padua 35124, Italy.

Sènan Mickael D’Almeida, Flow Cytometry Core Facility, School of Life Sciences, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne 1015, Switzerland.

Darawan Rinchai, Human Immunology Division, Translational Medicine Department, Sidra Medicine, Doha 26999, Qatar.

Eiman Ahmed, Human Immunology Division, Translational Medicine Department, Sidra Medicine, Doha 26999, Qatar.

Ofer Elhanani, Department of Molecular Cell Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 7610001, Israel.

Martina Rauner, Department of Medicine III, Center for Healthy Aging, Technical University Dresden, 01307 Dresden, Germany.

Barbara Zavan, Department of Medical Sciences, University of Ferrara, Ferrara 44121, Italy; Maria Cecilia Hospital, GVM Care & Research, Ravenna 48033, Italy.

Jean-Charles Grivel, Deep Phenotyping Core, Sidra Medicine, Doha 26999, Qatar.

Leeat Keren, Department of Molecular Cell Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 7610001, Israel.

Giulia Pasqual, Laboratory of Synthetic Immunology, Oncology and Immunology Section, Department of Surgery Oncology and Gastroenterology, University of Padua, Padua 35124, Italy.

Davide Bedognetti, Human Immunology Division, Translational Medicine Department, Sidra Medicine, Doha 26999, Qatar; Department of Internal Medicine and Medical Specialties, University of Genoa, Genoa 16132, Italy; College of Health and Life Sciences, Hamad Bin Khalifa University, Doha 34110, Qatar.

Klaus Ley, La Jolla Institute for Immunology, San Diego, CA 92037, USA; Immunology Center of Georgia (IMMCG), Augusta University, Augusta, GA 30912, USA.

Yury Gogotsi, A. J. Drexel Nanomaterials Institute and Department of Materials, Science and Engineering, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA.

Lucia Gemma Delogu, ImmuneNano Laboratory, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Padua, Padua 35129, Italy.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- [1].VahidMohammadi A, Rosen J, Gogotsi Y, Science 2021, 372, eabf1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gogotsi Y, Anasori B, ACS Nano 2019, 13, 8491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Han M, Maleski K, Shuck CE, Yang Y, Glazar JT, Foucher AC, Hantanasirisakul K, Sarycheva A, Frey NC, May SJ, Shenoy VB, Stach EA, Gogotsi Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 19110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Deysher G, Shuck CE, Hantanasirisakul K, Frey NC, Foucher AC, Maleski K, Sarycheva A, Shenoy VB, Stach EA, Anasori B, Gogotsi Y, ACS Nano 2020, 14, 204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Anasori B, Lukatskaya MR, Gogotsi Y, Nat. Rev. Mater. 2017, 2, 16098. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Li K, Liang M, Wang H, Wang X, Huang Y, Coelho J, Pinilla S, Zhang Y, Qi F, Nicolosi V, Xu Y, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2070306. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zhang Z, Yang S, Zhang P, Zhang J, Chen G, Feng X, Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fusco L, Gazzi A, Peng G, Shin Y, Vranic S, Bedognetti D, Vitale F, Yilmazer A, Feng X, Fadeel B, Casiraghi C, Delogu LG, Theranostics 2020, 10, 5435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lin H, Chen Y, Shi J, Adv. Sci. 2018, 5, 1800518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Driscoll N, Erickson B, Murphy BB, Richardson AG, Robbins G, Apollo NV, Mentzelopoulos G, Mathis T, Hantanasirisakul K, Bagga P, Gullbrand SE, Sergison M, Reddy R, Wolf JA, Chen HI, Lucas TH, Dillingham TR, Davis KA, Gogotsi Y, Medaglia JD, Vitale F, Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabf8629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rafieerad A, Yan W, Alagarsamy KN, Srivastava A, Sareen N, Arora RC, Dhingra S, Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2106786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rafieerad A, Sequiera GL, Yan W, Kaur P, Amiri A, Dhingra S, J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 101, 103440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gazzi A, Fusco L, Khan A, Bedognetti D, Zavan B, Vitale F, Yilmazer A, Delogu LG, Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Unal MA, Bayrakdar F, Fusco L, Besbinar O, Shuck CE, Yalcin S, Erken MT, Ozkul A, Gurcan C, Panatli O, Summak GY, Gokce C, Orecchioni M, Gazzi A, Vitale F, Somers J, Demir E, Yildiz SS, Nazir H, Grivel J-C, Bedognetti D, Crisanti A, Akcali KC, Gogotsi Y, Delogu LG, Yilmazer A, Nano Today 2021, 38, 101136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Han X, Huang J, Lin H, Wang Z, Li P, Chen Y, Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2018, 7, 1701394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dai C, Chen Y, Jing X, Xiang L, Yang D, Lin H, Liu Z, Han X, Wu R, ACS Nano 2017, 11, 12696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lu B, Zhu Z, Ma B, Wang W, Zhu R, Zhang J, Small 2021, 17, 2100946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rafieerad A, Yan W, Sequiera GL, Sareen N, Abu-El-Rub E, Moudgil M, Dhingra S, Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2019, 8, 1900569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Iravani S, Varma RS, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yang Y-SS, Atukorale PU, Moynihan KD, Bekdemir A, Rakhra K, Tang L, Stellacci F, Irvine DJ, Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sahaf B, Rahman A, Maecker HT, Bendall SC, Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2055, 351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hartmann FJ, Bendall SC, Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Spitzer MH, Nolan GP, Cell 2016, 165, 780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]