Abstract

Objective

To assess the prevalence and factors associated with cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation among high school adolescents of Pokhara Metropolitan City, Nepal.

Design

A cross-sectional study.

Setting

Pokhara Metropolitan City, Nepal.

Participants

We used convenient sampling to enrol 450 adolescents aged 16–19 years from four distinct higher secondary schools in Pokhara Metropolitan City.

Outcome measures

We administered the Cyberbullying and an Online Aggression Survey to determine the prevalence of cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to estimate the ORs and 95% CIs. Data were analysed using STATA V.13.

Results

The 30-day prevalence of cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation was 14.4% and 19.8%, and the over-the-lifetime prevalence was 24.2% and 42.2%, respectively. Posting mean or hurtful comments online was the most common form of both cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation. Compared with females, males were more likely to be involved in cyberbullying (adjusted OR (AOR)=13.52; 95% CI: 6.04 to 30.25; p value <0.001) and cyber-victimised (AOR=2.22; 95% CI: 1.33 to 3.73; p value <0.05). Using the internet almost every day was associated with cyberbullying (AOR=9.44; 95% CI: 1.17 to 75.79; p value <0.05) and cyber-victimisation (AOR=4.96; 95% CI: 1.06 to 23.18; p value <0.05). Students from urban place of residence were associated with both cyberbullying (AOR=2.45; 95% CI: 1.23 to 4.88; p value <0.05) and cyber-victimisation (AOR=1.77; 95% CI: 1.02 to 3.05; p value <0.05).

Conclusion

The study recommends the implementation of cyber-safety educational programmes, and counselling services including the rational use of internet and periodic screening for cyberbullying in educational institutions. The enforcement of strong anti-bullying policies and regulations could be helpful to combat the health-related consequences of cyberbullying.

Keywords: Cyberbullying, Cyber-Victimization, Adolescent, Internet, Social Media, Nepal

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study used multivariate logistic regression models, adjusting for potential confounders which helps to eliminate alternative explanations of our findings.

The cross-sectional design of this study limits inferences regarding the direction of association of several factors with cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation.

The questionnaire relied on self-reporting for the prevalence of cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation, which may have led to potential information bias.

Introduction

The rapid advances in internet technology and the use of innovative technological tools are pervasive worldwide. The expanding field of internet technology has remarkably helped billions of people connect and communicate in their public and private lives.1 However, internet penetration rates vary across countries. In the most developed countries, internet penetration is approximately 90.0%. Across developing countries, only an estimated 35.0% of the population has access to the internet.2 Among several innovative internet technologies, the use of social media is widespread among all age groups, with children and teenagers under the age of 18 making up about one-third of all internet users globally.3 In search of frequent gratification and peer acceptance, these age groups are at risk of problematic internet use such as cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation.4

Cyberbullying is defined as a repeated act when someone repeatedly harasses, harms or mistreats others through internet technologies or devices such as smartphones, email and internet sites.5 6 With the surge of information and data-sharing platforms, greater digital socialisation and the popularisation of social media, cyberbullying has become more common than ever. It often occurs when there is little adult oversight.7 A nationwide study conducted in the United States of America (USA) reported that at least 37.0% of adolescents aged 12–17 years encountered some form of cyberbullying, including harsh remarks and hurtful comments, rumours and physical threats.8 In a similar vein, a research by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) found that 19.7% of college students were engaged in cyberbullying at least once in their lifetime, while 54.4% of them reported experiencing it at least once.9 Unlike traditional bullying, it is more difficult to identify victims and perpetrators of cyberbullying and to mitigate at homes and schools.7 Furthermore, the rising prevalence of cyberbullying has resulted in adverse impacts on adolescents’ physical and mental health and led to poor academic performances globally.10 Evidence suggests that adolescents who have been victims of cyberbullying are more likely to experience emotional stress, anxiety or depression11–14 and may even have thoughts of or attempt suicide.13 14

According to the World Telecommunication/Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Indicators Database 2021, about 52.0% of the population has access to the internet in Nepal15 and the number of mobile users in early 2021 was equivalent to 131.3% of the total population.16 Furthermore, the social isolation regulation following the COVID-19 pandemic has restricted face-to-face interaction and caused a massive increase in the use of social networking sites and online activity, thereby contributing to the increase in the prevalence of cyberbullying.17 As a result, there was an increased possibility of encountering cyberbullying making adolescents more vulnerable to cybercrime.18 So far, the most common forms of cyberbullying in Nepal are related to social media platforms, such as Facebook, followed by YouTube and WhatsApp.19 20 To mitigate cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation, the government of Nepal has endorsed the reactive electronic transaction act 2006/2007.21 However, because of the unique characteristics of cyberbullying and associated fear and stigma, the perpetrators and victims under-report and hide their identities.7 22 Thus, there is interest in exploring how to abate cyberbullying among the most vulnerable adolescents in schools in Nepal.

Although cyberbullying is a growing area of research in public health, there are few reports on its prevalence and contributing factors, especially among Nepalese adolescents. Consequently, this study aims to assess the status and determinants of cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation among adolescents in selected schools of Nepal. We believe that the findings of this study will be beneficial for concerned stakeholders and help commence a meaningful dialogue at the policy level regarding cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

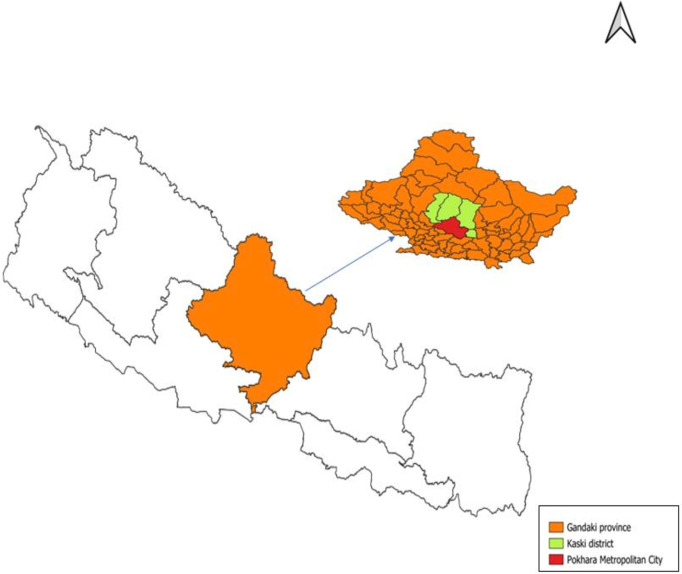

We conducted a cross-sectional school-based survey among the higher secondary school adolescents (16–19 years) of private and public schools in Pokhara Metropolitan City, Nepal (figure 1). Situated 200 km to the west of the capital Kathmandu, Pokhara serves as Nepal’s urban centre and functions as the capital city of the Gandaki Province. The adolescent age group of 10–19 years, in Gandaki province, makes up 1.6% of the overall population of 6.4 million.23 The educational landscape in Nepal comprises around 4187 higher secondary schools, encompassing 3628 community (public) schools, 913 institutional (private) schools and 6 religious institutions. In Pokhara, there are a total of 117 higher secondary schools, contributing to a total of 661 642 higher secondary students in Nepal.24 We noted that the use of internet technologies is slightly higher in private schools when compared with the government schools.25 For broad representation and logistical feasibility, we chose two private and public higher secondary schools for the present study.

Figure 1.

Map of Nepal showing the study site.

Sample size and participant recruitment

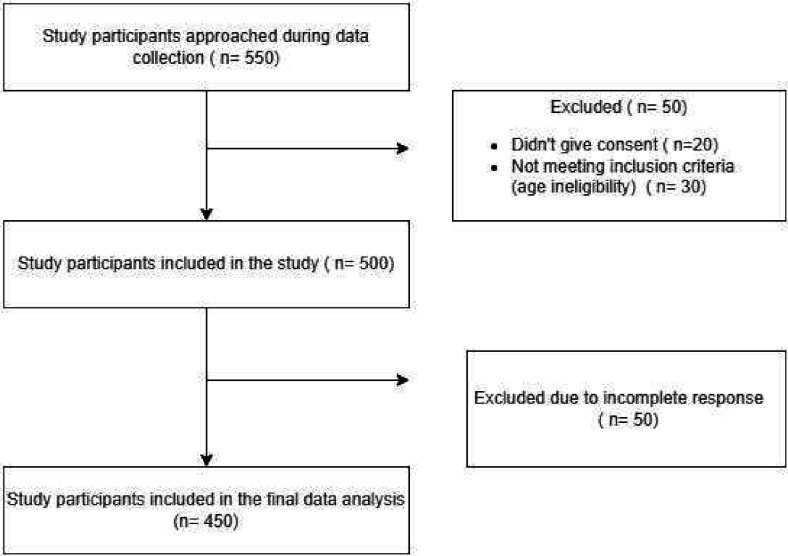

The sample size for the study participant was calculated using the Cochran formula,26 n=Z2pq/d2. Using the formula, the calculated sample size was 394, considering 64.0% prevalence (p) of cyberbullying among school students,18 a margin of error set at 5%, CI at 95% and considering a non-response rate of 10.0%. Ultimately, we recruited 450 participants who met the inclusion criteria: (a) respondents aged 16–19 years old; (b) having access to the internet; (c) availability of mobile phones and (d) exposure to social network sites (Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, WhatsApp/Twitter, Viber). Participants were selected conveniently in close coordination with the school authorities. We considered the availability of students and ensured participation did not interfere with their regular class schedule. Eligible participants were selected after obtaining the written informed consent and assent forms from their guardians. Individuals who declined to provide consent were excluded from the study. Figure 2 illustrates the number of participants approached for interviews and selection process in the study.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of study participant recruitment.

Data collection tool

The survey questionnaire was developed using tools from previous studies10 27 28 and through expert consultation. Outcome variables were adopted from the standard Cyberbullying and Online Aggression Survey Instrument.27

The questionnaire contained three sections:

Sociodemographic characteristics: this section included age (in years), gender (male/female), ethnicity (Brahmin/Chhetri, Gurung/Magar, others), residence (urban, rural), religion (Hindu, others), grade (11 or 12), type of family (nuclear, joint) and school type (private, public). Part of the tools were adapted from the Nepal Demographic Health Survey (NDHS).28

Internet-related: this section measured the use of internet in the past month (almost every day, at least once a week), average hours per day spent on social media (less than 1 hour, 1–2 hours, more than 2 hours) and most commonly used social media (WhatsApp/Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube). The categorisation of these variables was based on NDHS 2016.28

-

Experience with cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation: this section measured experiences with cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation in the last 30 days and over-the-lifetime.This measure was adopted from the Cyberbullying and Online Aggression Survey Instrument.27 The 30-day prevalence for cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation consisted of eight items. The participants provided self-reported responses on a Likert scale, including ‘never [0]’, ‘once [1]’, ‘several times [2]’ and ‘many times [3]’. Further, the reported responses ‘never and once’ were recategorised as ‘0’ and ‘several times and many times’ as ‘1’. For the analysis, we recategorised the response options as binary variables (0,1) where ‘0’ indicated ‘no experience of cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation’ and ‘1’ indicated ‘yes to experience of cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation’. Score of 1 in any of the eight items was considered as yes to cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation. One additional question was added to the tool as ‘Have you ever told anyone about this (cyberbullying or cyber-victimisation)?’, which was adopted from the study conducted by Aye et al.10

For the lifetime experience of the cyberbullying, the responses were collected to the question, ‘Over the lifetime, have you ever cyber-bullied someone through mobile phones or internet?’ and for cyber-victimisation, ‘Over the lifetime, have you ever been a cyber-victim through mobile phones or the internet?’.27

Operational definition

In this study, cyberbullying is defined based on participant’s responses to any of the eight items in the Cyberbullying and Online Aggression Survey Instrument.27 Those who answered ‘Yes’ to any of these items were categorised as individuals who have experienced cyberbullying. Similarly, cyber-victimisation is defined as participants who responded affirmatively to any of the eight items in the same survey instrument, indicating that they have been victims of cyberbullying.

Reliability of the tool

To ensure the reliability of the survey instrument, a pre-test was conducted among 30 higher secondary school adolescents in one of the schools in Pokhara Metropolitan City. The pre-test results were later used to refine the questionnaire. Cronbach’s alpha test was conducted, resulting in a coefficient of 0.7 for the tool measuring cyberbullying and 0.8 for the tool measuring cyber-victimisation.

Data collection technique

We employed a self-administered questionnaire to collect information on exposure, outcome and other variables in the classroom setting. Before administering the questionnaire, the principal investigator coordinated with the respective public and private school authorities of Pokhara Metropolitan City and obtained written approval to conduct the study. Information sessions were conducted with school teachers, guardians and study participants to explain the study’s purpose and expectations. Ethical considerations, emphasising participant’s privacy, confidentiality and anonymity during and after the research, were shared. We also explained the voluntary nature of the study and the right to stop participating at any time. Eligible students received an information sheet and informed assent and consent forms before data collection started. Students who provided signed written consent and an assent form from parents/or guardians were enrolled in the study. Data were collected by research assistants with a Bachelor’s degree in Public Health. Research assistants completed a 5-day training on data collection techniques and ethical considerations before the study began. The questionnaire was administered to the students in the classroom setting during non-teaching hours. The research team provided instructions at the beginning and remained available throughout the session to clarify any confusion or queries. Students took about 20–25 min to complete the survey. The data collection was conducted between April and June 2021. A total of 550 students (16–19 years) were identified, out of which 450 eligible participants were enrolled.

Data analysis

Following data collection, the trained research assistants cross-checked the data and the principal investigator verified the data to ensure the questionnaires were filled out correctly. Data were entered into Microsoft Excel and STATA V.13.0 (Stata Corp) was used for cleaning, coding and statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics (mean, frequency and percentage) were calculated to describe the sample characteristics and are presented in the form of figures and tables. The prevalence of cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation is presented for two different duration periods: the last 30 days and over-the-lifetime. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess the association between dependent (cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation) and independent variables (age, gender, family type, place of residence, class grade and internet-related factors). We reported crude and adjusted OR (AOR) with a 95% CI and p value (<0.05).

Ethical consideration

Official letters and permissions were obtained from concerned school authorities. Written informed consent and assent forms were collected from the study participants and parents or guardians. Data collection commenced only after obtaining written informed assent and consent forms. Confidentiality was maintained at all stages of data handling. The data were anonymised using random identity numbers.

Patient and public involvement

Participants were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting and dissemination plans of our research.

Results

Sociodemographic profile of the participants

The mean age of the participants was 17.5±0.9 years. More than half of the participants were female (54.4%), and about 58.7% of participants resided in urban areas. The majority of the participants followed the Hindu religion (80.0%) whereas the remaining 20.0% were religious minorities (Buddhist, Christian, Kirat and Muslims). About half of the participants were from private higher secondary schools (51.3%) (table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants (n=450)

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

| Age (in years) | (17.5±0.9) | |

| 16 | 59 | 13.1 |

| 17 | 178 | 39.5 |

| 18 | 156 | 34.7 |

| 19 | 57 | 12.7 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 245 | 54.4 |

| Male | 205 | 45.6 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Brahmin/Chhetri | 201 | 44.7 |

| Gurung/Magar | 164 | 36.4 |

| Others | 85 | 18.9 |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 186 | 41.3 |

| Urban | 264 | 58.7 |

| Class | ||

| Class 11 | 193 | 42.9 |

| Class 12 | 257 | 57.1 |

| Religion | ||

| Hindu | 360 | 80.0 |

| Others* | 90 | 20.0 |

| School type | ||

| Private | 231 | 51.3 |

| Public | 219 | 48.7 |

| Type of family | ||

| Joint | 135 | 30.0 |

| Nuclear | 315 | 70.0 |

*Buddhist, Christian, Kirat and Muslims.

Prevalence of cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation

The 30 days and over-the-lifetime prevalences of cyberbullying among participants were 14.4% and 24.2%, respectively. The 30 days and over-the-lifetime prevalences of cyber-victimisation were 19.8% and 42.2%, respectively.

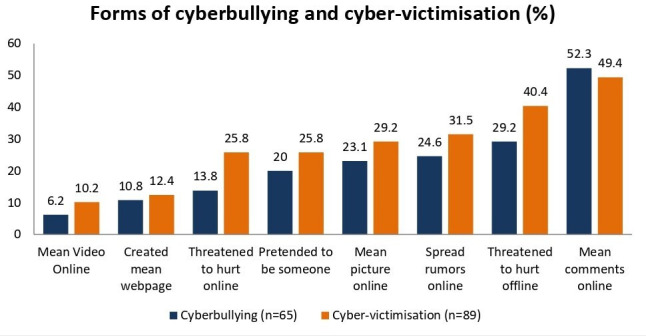

Forms of cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation

The most common form of cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation was posting mean or hurtful comments about someone online, that is, 52.3% and 49.4%, respectively (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forms of cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation in the past 30 days (n=450).

Risk factors associated with cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation (univariate and multivariate logistic analyses)

Table 2 shows the data on the factors associated with cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation in the last 30 days. Several factors were found significantly associated with cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation in both univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. The multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to adjust for potential confounders (age, gender, place of residence, frequency of internet use, social media use) for outcome variables (cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation). Using the multivariate logistic regression analysis, we found that gender, place of residence, frequency of internet use and social media use were associated with cyberbullying. Compared with females, males were more involved in cyberbullying acts (AOR=13.52; 95% CI: 6.04 to 30.25; p value <0.001). The odds of being involved in cyberbullying were higher among the participants who resided in urban areas as compared with those residing in rural areas (AOR=2.45; 95% CI: 1.23 to 4.88; p value=0.010). Participants who used the internet almost every day were more likely to be involved in cyberbullying as compared with those who used the internet once a week (AOR=9.44; 95% CI: 1.17 to 75.79; p value=0.035). The odds of being involved in cyberbullying were 32.0% lower among Facebook users (95% CI: 0.10 to 0.93; p value=0.037) and 22.0% lower among Instagram users (95% CI: 0.06 to 0.80; p value=0.022) as compared with WhatsApp and Twitter users.

Table 2.

Factors associated with cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation in study participants (n=450)

| Variables | Cyberbullying (n=65) | Cyber-victimisation (n=89) | ||||||||

| n (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value | AOR (95% CI) | P value | n (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value | AOR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | ||||||||||

| 16 ref. | 10 (16.9) | 16 (27.1) | ||||||||

| 17 | 23 (12.9) | 0.72 (0.32 to 1.63) | 0.440 | 0.79 (0.30 to 2.08) | 0.639 | 39 (21.9) | 0.75 (0.38 to 1.48) | 0.412 | 0.81 (0.37 to 1.75) | 0.596 |

| 18 | 25 (16.0) | 0.93 (0.41 to 2.08) | 0.870 | 1.23 (0.40 to 3.74) | 0.705 | 23 (14.7) | 0.46 (0.22 to 0.95) | 0.038* | 0.55 (0.22 to 1.38) | 0.211 |

| 19 | 7 (12.3) | 0.68 (0.24 to 1.94) | 0.479 | 0.66 (0.16 to 2.65) | 0.559 | 11 (19.3) | 0.64 (0.26 to 1.53) | 0.321 | 0.99 (0.33 to 2.97) | 0.995 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Female ref. | 8 (3.3) | 34 (13.9) | ||||||||

| Male | 57 (47.8) | 11.40 (5.29 to 24.59) | <0.001* | 13.52 (6.04 to 30.25) | <0.001* | 55 (26.8) | 2.27 (1.41 to 3.66) | <0.001* | 2.22 (1.33 to 3.73) | 0.002* |

| Class | ||||||||||

| Class 11 ref | 32 (16.6) | 45 (23.3) | ||||||||

| Class 12 | 33 (12.8) | 0.74 (0.43 to 1.25) | 0.265 | 0.54 (0.25 to 1.18) | 0.127 | 44 (17.1) | 0.67 (0.42 to 1.08) | 0.104 | 0.62 (0.33 to 1.16) | 0.139 |

| School type | ||||||||||

| Public ref | 26 (11.3) | 28 (12.1) | ||||||||

| Private | 39 (17.8) | 1.70 (1.00 to 2.91) | 0.050 | 1.10 (0.54 to 2.22) | 0.779 | 61 (27.9) | 2.79 (1.70 to 4.58) | <0.001* | 1.79 (1.00 to 3.20) | 0.047* |

| Residence | ||||||||||

| Rural ref | 15 (8.1) | 27 (14.5) | ||||||||

| Urban | 50 (18.9) | 2.66 (1.44 to 4.90) | 0.002* | 2.45 (1.23 to 4.88) | 0.010* | 62 (23.5) | 1.80 (1.09 to 2.97) | 0.020* | 1.77 (1.02 to 3.05) | 0.039* |

| Frequency of internet use | ||||||||||

| At least once a week ref | 1 (2.1) | 2 (4.2) | ||||||||

| Almost everyday | 64 (15.9) | 8.89 (1.20 to 65.66) | 0.032* | 9.44 (1.17 to 75.79) | 0.035* | 87 (21.6) | 6.35 (1.51 to 26.69) | 0.012* | 4.96 (1.06 to 23.18) | 0.041* |

| Social media | ||||||||||

| WhatsApp, Twitter ref | 9 (29.0) | |||||||||

| 32 (12.6) | 0.35 (0.14 to 0.83) | 0.018* | 0.32 (0.10 to 0.93) | 0.037* | 45 (17.8) | 1.46 (0.48 to 4.38) | 0.499 | 1.79 (0.55 to 5.80) | 0.327 | |

| 10 (11.9) | 0.33 (0.11 to 0.91) | 0.033* | 0.22 (0.06 to 0.80) | 0.022 | 22 (26.2) | 2.39 (0.75 to 7.61) | 0.139 | 2.19 (0.62 to 7.72) | 0.219 | |

| You tube | 14 (17.1) | 0.50 (0.19 to 1.32) | 0.163 | 0.51 (0.14 to 1.83) | 0.309 | 18 (22.0) | 1.89 (0.58 to 6.13) | 0.284 | 2.25 (0.62 to 8.17) | 0.217 |

| Duration of social media use | ||||||||||

| Less than 1 hour ref | 5 (7.7) | |||||||||

| 1–2 hours | 15 (11.7) | 1.59 (0.55 to 4.59) | 0.389 | 1.29 (0.38 to 4.34) | 0.677 | 68 (26.5) | 0.80 (0.31 to 2.05) | 0.651 | 0.41 (0.14 to 1.17) | 0.098 |

| Greater than 2 hours | 45 (17.5) | 2.54 (0.96 to 6.70) | 0.058 | 1.99 (0.64 to 6.10) | 0.229 | 8 (12.3) | 2.56 (1.16 to 5.64) | 0.020* | 1.53 (0.63 to 3.74) | 0.342 |

| Religion | ||||||||||

| Hindu ref | 52 (14.4) | 64 (17.7) | ||||||||

| Others† | 13 (14.4) | 1.00 (0.51 to 1.92) | 1.000 | 1.16 (0.54 to 2.49) | 0.699 | 25 (27.7) | 1.77 (1.04 to 3.03) | 0.035* | 1.66 (0.92 to 3.01) | 0.091 |

*P value <0.05-significant association.

†Buddhist, Christian, Kirat and Muslim.

AOR, adjusted OR.

Similarly, the multivariate logistic regression analysis found that gender, place of residence and frequency of internet use were associated with cyber-victimisation. The odds of being cyber-victimised were 2.22 times higher among males as compared with females (AOR=2.22; 95% CI: 1.33 to 3.73; p value=0.002). Cyber-victimisation was seen more among participants residing in urban areas compared with those residing in rural areas (AOR=1.77; 95% CI: 1.02 to 3.05; p value=0.039). Students in private schools were more cyber-victimised than students in public schools (AOR=1.79; 95% CI: 1.00 to 3.20; p value=0.047). The odds of being cyber-victimised were higher among those who used internet almost every day compared with those who used the internet once a week (AOR=4.96; 95% CI: 1.06 to 23.18; p value=0.041).

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the prevalence of and factors associated with cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation among higher secondary school adolescents. The 30 days and over-the-lifetime prevalences of cyberbullying among higher secondary school adolescents were 14.4% and 24.2%, respectively. For cyber-victimisation, the 30-day and over-the-lifetime prevalences were 19.8% and 42.2%, respectively. Previous studies reported the prevalence ranging from 6.3% to 34.8% for cyberbullying and 14.6% to 56.9% for cyber-victimisation.29–32 The variation could be explained by differences in the research methods, social-demographic characteristics, perspectives of cyberbullying experiences (victims, perpetrators or both victim and perpetrator), instruments (scales, study-specific questions) and sample size.33 34

Furthermore, the differences in internet penetration rates and access to electronic devices contribute significantly to differing prevalence rates across countries, as evidenced by the higher rates of cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation in the UK,35 USA,36 China,29 South Korea,17 where there is greater access to internet and electronic devices. Interestingly, in our study, the prevalence of cyber-victimisation was higher than cyberbullying. This was consistent with the studies conducted in Malaysia,37 Canada38 and Croatia.39 This could be due to the complexity and sensitive nature of the problem. Some individuals might be reluctant to admit their involvement in cyberbullying due to concerns about social and cultural consequences.22 The COVID-19 pandemic might also have influenced the prevalence of cyberbullying, with increased internet usage for educational purposes potentially contributing to a rise in cyberbullying.40–43 These findings underscore the prevalence of cyberbullying among higher secondary school adolescents, emphasising the need for heightened awareness and attention from parents, educators and policymakers to address this significant public health concern.

In our study, males exhibited higher involvement in both cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation. This aligns with findings from a survey conducted among 1917 secondary school adolescents in developed countries, where male adolescents were more prone to cyberbully others and experience cyber-victimisation.44–51 The higher involvement of males compared with females in cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation may be due to higher levels of exposure to and use of the internet and social platforms, such as YouTube and online gaming sites compared with females.52 Lower female involvement in cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation may reflect the culture of upholding family legacy and honour, potentially limiting access to social media and subsequently depriving them of positive digital connections in the context of South East Asia.53 Moreover, cultural and gender norms may play a role, as females perceive a greater risk in online communication and males may be more hesitant to express fear, vulnerability and insecurity related to cyberbullying experiences.54 The gendered pattern may also be influenced by cultural stereotypes. For example, males may refrain from reporting victimisation because it might undermine their sense of masculinity.55 In addition, females are more likely to view cyberbullying as a serious problem56 and hurtful act compared with males,57 which might encourage reporting victimisation. The findings emphasise the need for further exploration into the relationship between gender, culture and cyberbullying involvement. Differences in online behaviours, preferred online media and internet access across genders warrant comprehensive examination to deepen our understanding of the relationship between gender and cyberbullying.

Frequency of internet use and exposure to particular social networking sites emerged as significant factors associated with both cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation in our study. We found that Facebook and Instagram users were more frequently involved in cyberbullying which aligns with the findings of studies conducted among school students in Singapore,58 Thailand59 and Indonesia.60 This association may be attributed to Facebook’s popularity among youths61 in South East countries. The unique features of Facebook, such as allowing users to share detailed information on their profiles, post messages, photos/videos and web links on friends’ ‘walls’, and contribute to enhanced mutual social interaction through features like group chats, applications and fan pages.28 62 In contrast to these findings, cyber-victimisation was increasingly reported in WhatsApp groups.63 Unlike Facebook, WhatsApp groups allow for direct interaction within a private space, potentially leading to more targeted or personalised communication. The ubiquity of internet and social media usage in today’s context is undeniable. While the different social media platforms have diverse features, it is imperative to educate adolescents about safe internet practices and equip them with skills to navigate different online platforms responsibly. Technology must be carefully monitored, and efforts should be directed toward promoting responsible technology use. Social media sites should implement control mechanisms to ensure a safe user experience and filter offensive comments or hate speech. Moreover, longitudinal studies are essential to identify specific preventive measures and gain a deeper understanding of the evolving dynamics in the online environment.

Finally, we found that urban place of residence was positively associated with being involved in cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation. Students in urban settings experienced cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation more frequently than those in rural settings. This was consistent with studies in India64 and Taiwan.65 This could be a result of greater access and exposure to the internet and communication technology in the urban areas compared with rural areas.66 The urban–rural differences in cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation might also be due to lack of the parental mediation and internet skills.65 Further research should focus on identifying and understanding urban–rural differences in cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation to develop targeted interventions for both contexts.

Strengths/limitations

The study had some limitations. First, it was a cross-sectional study that used a non-probability sampling method. Due to the cross-sectional design, it was not possible to establish the direction of the risk associations. Second, this study was conducted in a specific area within a limited time period. Therefore, the findings may not be generalised to all secondary school students in Nepal. Third, the questionnaire used to assess the prevalence of cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation relied on self-reported data, potentially introducing bias. Furthermore, the tool did not consider the impact of cyberbullying on overall health. Future studies should emphasise capturing the impact of cyberbullying on physical, mental, social and intellectual health to support anti-cyberbullying interventions or plans.

This research is a valuable contribution to the gaps in literature because it provides meaningful insights into cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation among high secondary school adolescents. Besides this, the use of standardised tools and cost-effectiveness nature are strengths of this study.

Conclusion

The widespread use of technology and social media platforms has put children and adolescents at greater risk for cyberbullying. It is arguably high time for policymakers, major stakeholders and researchers to constructively plan for advanced research, evidence-based policy formulations and tailored interventions to prevent cyberbullying and cyber-victimisation. The government can formulate anti-bullying policies for the educational institutions to control cyberbullying issues. Similarly, the government should increase awareness about existing cyber-laws and policies. Integrating education on cyberbullying into school curricula is essential. Curricula should cover topics such as the impact of cyberbullying on mental health, effective coping mechanisms and guidelines for reporting cyberbullying incidents. Periodic screening for cyberbullying, counselling services, cybersafe educational programmes and awareness-raising campaigns are urgently needed for students. By implementing these multifaceted approaches, we can create a safer and healthier online environment for adolescents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the study participants and their parents, school authorities and research assistants for their valuable time and support to complete the study. We would also like to acknowledge the Department of Public Health, Kathmandu University School of Medical Sciences for their continuous support and guidance throughout this study. We are grateful to Nicole Castle in editing the language of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Twitter: @kunwarsuraxya

Contributors: The following authors have contributed to the manuscript in different ways. SK, SS, BMK, AA, AKS and AS contributed to conceptualization and design. SK, IBS and AR contributed to data collection. SK, SS, BMK, AS and SM contributed to formal analysis. BMK, AS and AKS contributed to supervision. SK and SS contributed to writing-original draft. SS, SM, AJ, IBS, AR, AA, BMK, AS and AKS contributed to writing-review and editing. SK is the guarantor for this manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Map disclaimer: The inclusion of any map (including the depiction of any boundaries therein), or of any geographic or locational reference, does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. Any such expression remains solely that of the relevant source and is not endorsed by BMJ. Maps are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained from parent(s)/guardian(s)

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved. The ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Committee of Kathmandu University School of Medical Sciences (Reference ID: IRC-126/20), Dhulikhel Hospital for conducting the study. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Cohen-Almagor R. Social responsibility on the Internet: addressing the challenge of Cyberbullying. Aggression and Violent Behavior 2018;39:42–52. 10.1016/j.avb.2018.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Bank . Connecting for inclusion: Broadband access for all. Available: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/digitaldevelopment/brief/connecting-for-inclusion-broadband-access-for-all [Accessed 27 Jul 2023].

- 3.Keeley B, Little C. The State of the Worlds Children 2017: Children in a Digital World UNICEF, . 2017Available: from: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED590013 [Accessed 25 Jan 2023].

- 4.Ortega-Ruipérez B, Castellanos Sánchez A, Marcano B. n.d. Risks in adolescent adjustment by Internet exposure: evidence from PISA. Front Psychol;12. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.763759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chisholm JF. Cyberspace violence against girls and adolescent females. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2006;1087:74–89. 10.1196/annals.1385.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patchin JW, Hinduja S. Measuring Cyberbullying: implications for research. Aggression and Violent Behavior 2015;23:69–74. 10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gohal G, Alqassim A, Eltyeb E, et al. Prevalence and related risks of Cyberbullying and its effects on adolescent. BMC Psychiatry 2023;23:39. 10.1186/s12888-023-04542-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cyberbullying statistics and facts for 2023. Available: https://www.comparitech.com/internet-providers/cyberbullying-statistics/ [Accessed 25 Jan 2023].

- 9.Ozden MS, Icellioglu S. The perception of Cyberbullying and Cybervictimization by university students in terms of their personality factors. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 2014;116:4379–83. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.951 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khine AT, Saw YM, Htut ZY, et al. Assessing risk factors and impact of Cyberbullying Victimization among university students in Myanmar: A cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE 2020;15:e0227051. 10.1371/journal.pone.0227051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell KJ, Ybarra M, Finkelhor D. The relative importance of online Victimization in understanding depression, delinquency, and substance use. Child Maltreat 2007;12:314–24. 10.1177/1077559507305996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diamanduros T, Downs E, Jenkins SJ. The role of school psychologists in the assessment, prevention, and intervention of Cyberbullying. Psychology in the Schools 2008;45:693–704. 10.1002/pits.20335 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Geel M, Vedder P, Tanilon J. Relationship between peer Victimization, Cyberbullying, and suicide in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168:435. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Cyberbullying, and suicide. Arch Suicide Res 2010;14:206–21. 10.1080/13811118.2010.494133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Bank . Individuals using the Internet (% of population), Available: https://data.worldbank.org [Accessed 27 Jul 2023].

- 16.Kemp S. Digital 2021 Nepal Datareportal. 2021. Available: from: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2021-nepal [Accessed 27 Jul 2023].

- 17.Shin SY, Choi YJ. Comparison of Cyberbullying before and after the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:10085. 10.3390/ijerph181910085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dhungana RK. Cyber bullying -Nepal. 2014. Available: https://www.academia.edu/6391726/Cyber_Bullying_Nepal

- 19.Samiti RS. 560 cases of Cyber-crime registered in six months [The Himalayan Times]. 2017. Available: https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/560-cases-of-cyber-crime-registered/

- 20.Himalayan News Service . Cyber bureau receives 320 plaints in three months. The Himalayan Times, 2019. Available: https://thehimalayantimes.com/kathmandu/cyber-bureau-receives-320-plaints-in-three-months [Google Scholar]

- 21.The electronic transactions act 2063. 2008. Available: http://www.tepc.gov.np/uploads/files/12the-electronic-transaction-act55.pdf [Accessed 27 Jul 2023].

- 22.Alsawalqa RO. Cyberbullying, social stigma, and self-esteem: the impact of COVID-19 on students from East and Southeast Asia at the University of Jordan. Heliyon 2021;7:e06711. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Department of Health Services . Nepal annual report 2021/22; 2023. Available: http://dohs.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/Annual_Report.pdf [Accessed 8 Jan 2024].

- 24.Center for Education and Human Resource Department . Flash I REPORT 2076 (2019-020); 2020. Available: https://cehrd.gov.np/file_data/mediacenter_files/media_file-17-1589823848.pdf [Accessed 8 Jan 2024].

- 25.Adedeji P, Godwin-Ewu P, Irinoye OO, et al. Internet access and use of social media among adolescents in selected secondary schools in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. J Health Inform Dev Ctries 2021;15. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh AS, Masuku MB. Sampling techniques & determination of sample size in applied Statistics research: an overview. International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management 2014;2:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hinduja S, Patchin JW. school climate 2.0: preventing Cyberbullying and Sexting one classroom at a Time. 2590 Conejo Spectrum, Thousand Oaks California 91320 United States, 10.4135/9781506335438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nepal demographic and health survey (NDHS) 2016. Available: https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr336/fr336.pdf [Accessed 26 Jul 2023].

- 29.Zhou Z, Tang H, Tian Y, et al. Cyberbullying and its risk factors among Chinese high school students. School Psychology International 2013;34:630–47. 10.1177/0143034313479692 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Y, Chou C. An analysis of multiple factors of Cyberbullying among junior high school students in Taiwan. Computers in Human Behavior 2010;26:1581–90. 10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee C, Shin N. Prevalence of Cyberbullying and predictors of Cyberbullying perpetration among Korean adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior 2017;68:352–8. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.047 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Udris R. Cyberbullying among high school students in Japan: development and validation of the online disinhibition scale. Computers in Human Behavior 2014;41:253–61. 10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selkie EM, Fales JL, Moreno MA. Cyberbullying prevalence among US middle and high school-aged adolescents: A systematic review and quality assessment. J Adolesc Health 2016;58:125–33. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ybarra ML, Boyd D, Korchmaros JD, et al. Defining and measuring Cyberbullying within the larger context of bullying Victimization. J Adolesc Health 2012;51:53–8. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peck HC, Tzani C, Lester D, et al. Cyberbullying in the UK: the effect of global crises on the Victimization rates. Journal of School Violence 2024;23:111–23. 10.1080/15388220.2023.2278473 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamm MP, Newton AS, Chisholm A, et al. Prevalence and effect of Cyberbullying on children and young people: A Scoping review of social media studies. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:770–7. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohd Fadhli SA, Liew Suet Yan J, Ab Halim AS, et al. Finding the link between Cyberbullying and suicidal behaviour among adolescents in Peninsular Malaysia. Healthcare 2022;10:856. 10.3390/healthcare10050856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaillancourt T, Brittain H, Krygsman A, et al. School bullying before and during COVID-19: results from a population-based randomized design. Aggress Behav 2021;47:557–69. 10.1002/ab.21986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vejmelka L, Matković R. Online interactions and problematic Internet use of Croatian students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Information 2021;12:399. 10.3390/info12100399 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Center for Education Statistics . "Students' Internet access before and during the Coronavirus pandemic by household socioeconomic status. NCES Blog; 2021. Available: https://nces.ed.gov/blogs/nces/post/students-internet-access-before-and-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic-by-household-socioeconomic-status [Accessed 10 Feb 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 41.De’ R, Pandey N, Pal A. Impact of Digital surge during COVID-19 pandemic: A viewpoint on research and practice. Int J Inf Manage 2020;55:102171. 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jahan I, Hosen I, al Mamun F, et al. How has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted Internet use behaviors and facilitated problematic Internet use? A Bangladeshi study. PRBM 2021;Volume 14:1127–38. 10.2147/PRBM.S323570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lazuras L, Barkoukis V, Ourda D, et al. A process model of Cyberbullying in adolescence. Computers in Human Behavior 2013;29:881–7. 10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonanno RA, Hymel S. Cyber bullying and Internalizing difficulties: above and beyond the impact of traditional forms of bullying. J Youth Adolesc 2013;42:685–97. 10.1007/s10964-013-9937-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mura G, Diamantini D. Cyberbullying among Colombian students: an exploratory investigation. EJIHPE 2013;3:249–56. 10.3390/ejihpe3030022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shin N, Ahn H. Factors affecting adolescents’ involvement in Cyberbullying: what divides the 20% from the 80%? Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2015;18:393–9. 10.1089/cyber.2014.0362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Navarro R, Larrañaga E, Yubero S. Gender identity, gender-typed personality traits and school bullying: victims, bullies and bully-victims. Child Ind Res 2016;9:1–20. 10.1007/s12187-015-9300-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sticca F, Ruggieri S, Alsaker F, et al. Longitudinal risk factors for Cyberbullying in adolescence. Community & Applied Soc Psy 2013;23:52–67. 10.1002/casp.2136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kowalski RM, Limber SP. Psychological, physical, and academic correlates of Cyberbullying and traditional bullying. J Adolesc Health 2013;53(1 Suppl):S13–20. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park S, Na E-Y, Kim E. The relationship between online activities, Netiquette and Cyberbullying. Children and Youth Services Review 2014;42(July 2014):74–81. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Popović-Ćitić B, Djurić S, Cvetković V. The prevalence of Cyberbullying among adolescents: A case study of middle schools in Serbia. School Psychology International 2011;32:412–24. 10.1177/0143034311401700 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thomas NJ, Martin FH. Video‐Arcade game, computer game and Internet activities of Australian students: participation habits and prevalence of addiction. Australian Journal of Psychology 2010;62:59–66. 10.1080/00049530902748283 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ghai S, Magis-Weinberg L, Stoilova M, et al. Social media and adolescent well-being in the global South. Curr Opin Psychol 2022;46:101318. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pieschl S, Porsch T. The complex relationship between Cyberbullying and trust. DEV 2017;11:9–17. 10.3233/DEV-160208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Q. Cyberbullying in schools: A research of gender differences. Sch Psychol Int 2006;27:157–70. 10.1177/0143034306064547 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Agatston PW, Kowalski R, Limber S. Students’ perspectives on Cyber bullying. J Adolesc Health 2007;41(6 Suppl 1):S59–60. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zsila Á, Urbán R, Griffiths MD, et al. Gender differences in the association between Cyberbullying Victimization and perpetration: the role of anger rumination and traditional bullying experiences. Int J Ment Health Addiction 2020;18:258–61. 10.1007/s11469-018-0050-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kwan GCE, Skoric MM. Facebook bullying: an extension of battles in school. Computers in Human Behavior 2013;29:16–25. 10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sittichai R, Smith P. Bullying and Cyberbullying in Thailand: A review. Ijcse 2013;6:31–44. 10.7903/ijcse.1032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Safaria T. Prevalence and impact of Cyberbullying in a sample of Indonesian junior high school students. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET 2016;15:82–91. [Google Scholar]

- 61.The Social Shepherd . 33 Essential Facebook Statistics You Need To Know In 2024. The Social Shepherd website, Available: https://thesocialshepherd.com/blog/facebook-statistics [Accessed 9 Jun 2024].

- 62.Kowal M, Sorokowski P, Sorokowska A, et al. Reasons for Facebook usage: data from 46 countries. Front Psychol 2020;11:711. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abaido GM. Cyberbullying on social media platforms among university students in the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 2020;25:407–20. 10.1080/02673843.2019.1669059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaur M, Saini M. Indian government initiatives on Cyberbullying: A case study on Cyberbullying in Indian higher education institutions. Educ Inf Technol (Dordr) 2023;28:581–615. 10.1007/s10639-022-11168-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chang F-C, Miao N-F, Chiu C-H, et al. Urban–rural differences in parental Internet mediation and adolescents’ Internet risks in Taiwan. Health, Risk & Society 2016;18:188–204. 10.1080/13698575.2016.1190002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gajurel A. Bridging the Digital divide in Nepal. Nepal Live Today; 2023. Available: https://www.nepallivetoday.com/2023/07/06/bridging-the-digital-divide-in-nepal/ [Accessed 6 Feb 2024]. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.