Abstract

Introduction

Lack of transparent communication between patients and physicians regarding the use of herbal medicine (HM) presents a major public health challenge, as inappropriate HM use poses health risks. Considering the widespread use of HM and the risk of adverse events, it is crucial for pregnant women to openly discuss their HM use with healthcare providers. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aims to estimate the pooled prevalence of pregnant women’s HM use and disclosure to healthcare providers and to examine the relationship between HM disclosure and various maternal and child health (MCH) measures.

Methods

A systematic search of five databases was conducted for cross-sectional studies on HM use during pregnancy published from 2000 to 2023. Data extraction followed a standardised approach, and Stata V.16.0 was used for data analysis. Also, Spearman’s correlation coefficient was calculated to examine the association between use and disclosure of HM and various MCH indicators.

Results

This review included 111 studies across 51 countries on the use of HM among pregnant women. Our findings showed that 34.4% of women used HM during pregnancy, driven by the perception that HM is presumably safer and more natural than conventional medical therapies. However, only 27.9% of the HM users disclosed their use to healthcare providers because they considered HM as harmless and were not prompted by the healthcare providers to discuss their self-care practices. Furthermore, a significant correlation was observed between HM disclosure and improved MCH outcomes.

Conclusion

Inadequate communication between pregnant women and physicians on HM use highlights a deficiency in the quality of care that may be associated with unfavourable maternal outcomes. Thus, physician engagement in effective and unbiased communication about HM during antenatal care, along with evidence-based guidance on HM use, can help mitigate the potential risks associated with inappropriate HM use.

Keywords: Systematic review, Maternal health, Health education and promotion, Health policy, Public Health

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

As the use of herbal medicine (HM) increases among pregnant women, promoting open and proactive patient–physician communication is essential to help women make informed decisions about HM use during pregnancy, prevent potential harm and ensure optimal care. However, existing reviews on pregnant women’s HM use provide limited insights into communication between pregnant women and their physicians regarding HM use.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Despite the widespread use of HM among pregnant women, less than one-third of women discussed their use with obstetric care providers due to the perceived safety of HM and the lack of inquiry from physicians.

Furthermore, the non-disclosure of HM use showed a significant correlation with higher maternal and neonatal mortality, lower proportions of births attended by skilled birth attendants and lower antenatal care coverage. This correlation may be influenced by suboptimal patient–physician communication in regions with poorer maternal and child health (MCH) outcomes.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

To prevent potential adverse MCH outcomes resulting from inappropriate HM use, effective patient–physician communication regarding self-care practices should be facilitated.

Advocating training for healthcare providers on commonly used HM, raising awareness about the safe use, benefits and potential toxicity of HM through community programmes, and integrating inquiries about HM use into standard antenatal case-taking procedures are critical steps to promote open discussions about HM use during antenatal care.

Introduction

Pregnancy is characterised by hormonal changes that often result in significant physical discomfort and mood swings.1–3 To address these health issues, expectant mothers commonly turn to self-care approaches, as they fear the potential teratogenic effects of conventional pharmaceutical products.4 5 Furthermore, during global health crises, such as the outbreak of COVID-19, self-care practices gained increased attention due to the rise in social distancing, self-isolation and strain on the public health system.6 7 Self-care approaches have proven beneficial not only because they allow individuals to actively participate in their own healthcare and exercise patient autonomy, but also because they improve access to healthcare for those facing geographical and economic barriers.8

However, certain self-care modalities, such as herbal medicine (HM), contain bioactive compounds that can pose risks to both the mother and the fetus if misused.9–15 While safety and efficacy data exist for some HM, many others lack conclusive evidence and, in some cases, rely on anecdotal evidence and information from mass media and other digital platforms.9 16–18 Specifically, the abundance of information available online blurs the line between lay and expert knowledge, making it challenging for individuals to discern accurate information.8 Furthermore, the use of HM is often cited as one of the reasons for delay in seeking professional healthcare services and is associated with inadequate antenatal care (ANC) utilisation,19–24 potentially increasing the risk of unfavourable maternal and child health (MCH) outcomes.25 26 Therefore, effective management of pregnant women’s HM use has emerged as a significant public health concern in order to prevent the misuse of HM and mitigate subsequent threats to MCH.

Promoting patient–doctor communication on pregnant women’s health regimen during ANC is a non-pharmacological strategy that enables healthcare providers to support the women in the safe and appropriate use of HM.27–29 This approach allows healthcare providers to assist pregnant women in making informed decisions about their use of self-care interventions and provides an opportunity for early intervention if potential harm arises. Nevertheless, as many as 93% of complementary medicine (CAM) users do not discuss their use with conventional healthcare providers because the importance of discussing HM use is often overlooked.30 Additionally, the lack of clinical guidelines encouraging healthcare providers to discuss patients’ use of additional healthcare approaches during medical consultations, coupled with limited physician knowledge of HM, creates barriers to effective communication.31 Consequently, inadequate patient–physician communication regarding HM use, along with the neglect of patient preferences and choices in healthcare, hinders coordination between complementary health practices and conventional medical care, potentially exposing HM users to health risks.27 32–35

Despite the importance of open and effective communication on self-care practices between pregnant women and their obstetric care providers,9 27 29 discussions about HM use are relatively rare and mostly initiated by patients rather than healthcare providers in current clinical practice. Thus, patient disclosure of HM use serves as a critical first step for patient–doctor communication on HM use and becomes an important factor in achieving optimal MCH outcomes. However, previous studies on the use of HM during pregnancy offer limited insights into the discussion between pregnant women and their healthcare providers about HM use and focus primarily on patterns and characteristics of HM use.36–39 Therefore, this review aims to estimate the pooled prevalence of pregnant women’s HM use and examine their disclosure practices to healthcare providers, while also exploring the potential association between HM disclosure and improved MCH status.

Methods

This review was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) database (CRD42022352846), and the findings of this systematic review are presented following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (online supplemental appendix 1).40

bmjgh-2023-013412supp001.pdf (45.8KB, pdf)

Search strategy

An electronic database search was performed on 16 March 2023, using PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE (Ovid), CINAHL, Scopus and Web of Science to identify studies that report pregnant women’s HM use and their disclosure of HM use to healthcare providers. The search was conducted using MeSH and related keywords of three major terms: herbal medicine, pregnancy and cross-sectional study (online supplemental appendix 2). The search was limited to cross-sectional studies because such study designs are commonly used to assess participants’ health behaviours and to improve the comparability of the findings.9 30 The publication years were restricted to 2000–2023, considering the increasing popularity of HM use over the last two decades.41 The language was restricted to English-language only. An ancestral search was also conducted to identify any additional relevant articles.

bmjgh-2023-013412supp002.pdf (63.1KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

This review includes studies that are: (1) conducted between 2000 and 2023 and (2) report cross-sectional data on the use and disclosure of HM during pregnancy. For our study, the time frame of pregnancy included the period from conception to birth, excluding HM use during labour or postpartum. This review specifically focused on HM use to reduce the heterogeneity among the studies due to varying definitions of complementary and CAM. Moreover, studies focusing on a single HM modality or a specific indication for use were excluded, as they may not provide an accurate representation of the prevalence rates for HM use and could affect the estimation of the general HM use during pregnancy.

Study selection and risk of bias assessment

Three reviewers completed the full-text review of the selected studies to examine various study characteristics (ie, publication year, study design, setting and research subjects) and inclusion of key outcomes (ie, the prevalence of HM use and disclosure, as well as any additional quantitative data related to patient–physician communication regarding HM use). In cases where a study explored multiple CAM modalities, only the prevalence of HM use was extracted. After independently extracting the data, the three reviewers compared their results and resolved any disagreements with the assistance of senior researchers.

The quality of selected studies was evaluated using the critical appraisal tool developed by Hoy et al,42 which is designed to evaluate the risk of bias in prevalence studies and consists of 11 items. Each item was scored either 0 or 1, with lower scores indicating a lower risk of bias. Studies that scored 7 or higher on the quality assessment scale were excluded from the final analysis.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

A meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the pooled prevalence of HM use and disclosure among pregnant women and the corresponding 95% CIs, using the Stata V.16.0. Given the high heterogeneity among the studies (I²=99.00%), a random effect meta-analysis was conducted, and the funnel plot and the Egger test were used to examine publication bias (online supplemental appendices 3 and 4). A subgroup meta-analysis was performed to analyse differences in the HM use and disclosure rates by geographical region (ie, by countries and by continents: Africa, Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, Europe, South-East Asia and Western Pacific) and the study year (ie, studies conducted between 2000–2010 and 2011–2023).

bmjgh-2023-013412supp003.pdf (85.5KB, pdf)

Furthermore, the HM use and disclosure rates were also compared based on the MCH status of the study settings because we hypothesised that pregnant women’s disclosure of HM use is associated with better MCH outcomes. As open communication on HM use between expectant mothers and their healthcare providers could help prevent inappropriate HM use,23 27 we considered the disclosure of HM as an intervention for achieving optimal MCH. The MCH status of each study setting was determined by assessing the major MCH indicators, such as maternal mortality rate (MMR), neonatal mortality rate (NMR), skilled birth attendant (SBA) utilisation rate and the coverage of at least four ANC visits at the time of each study.

To perform the subgroup analysis based on MCH status, each study was categorised based on whether the country of the study setting had achieved the WHO’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target for MMR (70/100 000), NMR (12/10 000) and SBA utilisation (90%).43 44 Regarding ANC utilisation rate, countries were grouped based on whether the study setting met the global target of at least four ANC coverage (90%).45 Country-specific MCH indicator values were obtained from the WHO Data Platform,46 UNICEF Data Warehouse47 and the World Bank Open Data.48 In cases where country-specific data were unavailable, the researchers assumed the MCH situation of the country, classifying it as below or above the global average based on the country’s economic status (ie, gross domestic product per capita).49 50

Lastly, using the SPSS V.26.0., Spearman’s correlation coefficient and scatter plots were computed to explore the potential association between various MCH measures and HM utilisation and disclosure rates. A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Patient and public involvement

There was no direct participation or input from patients or the public in the design or conduct of this systematic review and meta-analysis. However, our research findings will contribute to inspiring healthcare providers and policy-makers to develop interventions that improve the quality of patient care and ensure the safety and well-being of pregnant mothers and their children.

Results

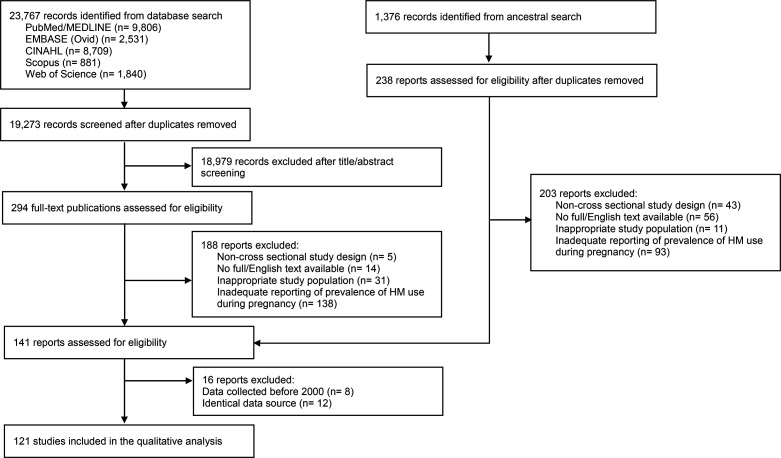

Of 23 767 studies retrieved from the database searches, 294 studies met the criteria for full-text screening. Among these, 188 records were excluded from the review for one of the following reasons: non-cross-sectional study design, inappropriate study population, unavailability of full English text and inadequate reporting of pregnant women’s HM use (figure 1). Additionally, 1376 records were identified by reviewing the reference lists of the remaining 106 studies. After removing duplicates, 238 additional studies were included for further review, and 35 studies met the eligibility criteria after the full-text appraisal. Furthermore, 16 studies were excluded due to using data collected before 2000 and identical datasets. Consequently, 121 studies were subjected to a risk of bias assessment, and after excluding 10 studies with a high risk of bias,51–60 a total of 111 studies were included in the final review (online supplemental appendix 5).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of search strategy.

bmjgh-2023-013412supp004.pdf (122.9KB, pdf)

Characteristics of studies

Among 111 studies, 102 studies were cross-sectional in design.27 61–161 Three studies used mixed-method approaches,162–164 and six studies had non-cross-sectional designs (ie, longitudinal and case–control),165–170 but reported cross-sectional data on HM use during pregnancy (online supplemental appendix 6). Regarding the geographical distribution of included studies, a majority of them were conducted in Africa.66 69 77 81 82 89 91 95 98 100 101 105 106 115 116 119 121–123 129 132–135 137–140 143 144 146 150 153 156 158–164 Lastly, 21 out of 111 studies presented findings related to pregnant women’s disclosure of HM use to their healthcare providers.27 70 73 83 85 86 91 109 110 115 117 122 125 126 129 133 142 149 155 160 164

bmjgh-2023-013412supp005.pdf (157.1KB, pdf)

Prevalence of HM use among pregnant women

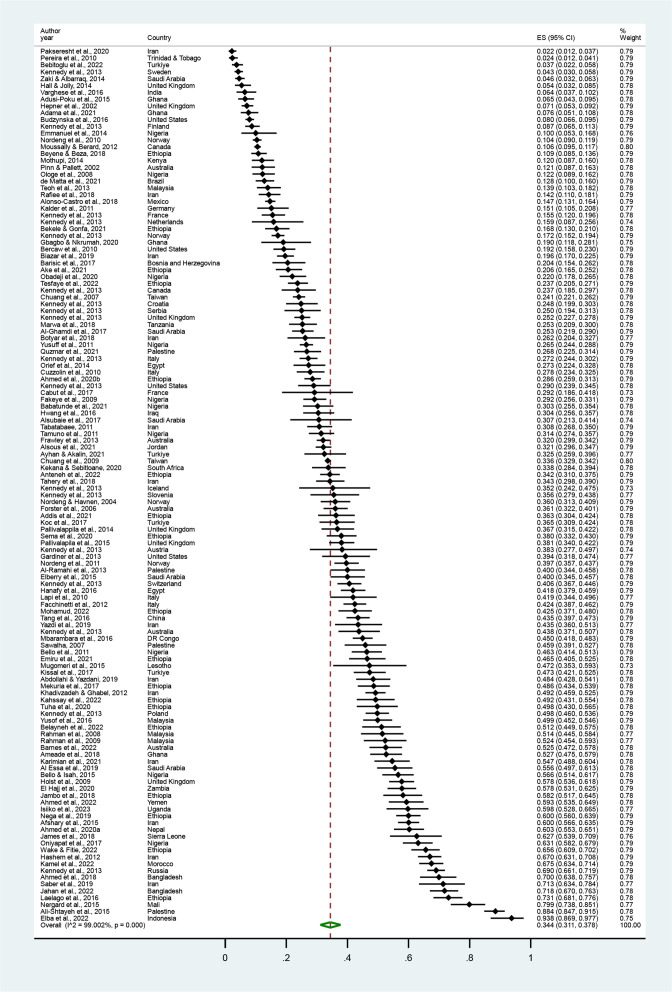

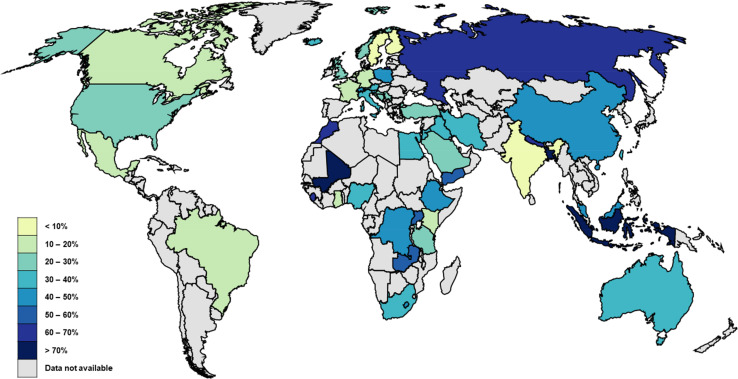

The pooled prevalence of HM use during pregnancy was 34.4% (95% CI 31.1% to 37.8%), ranging from 2.2% to 93.8% (table 1, figure 2).55 136 Among the 51 countries included, HM use was the lowest in Trinidad and Tobago and the highest in Indonesia (figure 3).76 101 The prevalence varied significantly by study year (p=0.048) and geographical region (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Pooled prevalence of HM use and HM disclosure by study characteristics

| Characteristics | HM utilisation†† | HM disclosure†† | ||||||

| Mean* | 95% CI | n† | P value | Mean* | 95% CI | n† | P value | |

| Overall | 34.4% | 31.1% to 37.8% | 111 | 27.9% | 20.0% to 36.5% | 21 | ||

| Study year | ||||||||

| 2000–2010 | 28.8% | 23.1% to 34.7% | 29 | 0.048 | 24.3% | 11.2% to 40.3% | 3 | 0.643 |

| 2011–2023 | 36.1% | 31.9% to 40.5% | 82 | 28.5% | 19.6% to 38.2% | 18 | ||

| Geographical region | ||||||||

| Africa | 37.6% | 31.9% to 43.6% | 41 | <0.001 | 9.7% | 4.6% to 16.5% | 7 | <0.001 |

| Americas | 16.0% | 11.2% to 21.3% | 8 | 38.1% | 26.1% to 51.2% | 1 | ||

| Eastern Mediterranean | 39.5% | 30.9% to 48.5% | 28 | 44.5% | 36.2% to 52.9% | 7 | ||

| Europe | 27.5% | 21.0% to 34.5% | 19 | 30.1% | 9.9% to 55.4% | 3 | ||

| South-East Asia | 60.5% | 30.9% to 86.3% | 5 | 35.4% | 18.2% to 54.7% | 3 | ||

| Western Pacific | 36.1% | 30.9% to 41.5% | 12 | – | – | – | ||

| Maternal mortality rate (SDG target 3.1.1)‡ | ||||||||

| Less than 70/100 000 live births | 30.8% | 26.9% to 34.9% | 62 | 0.008 | 40.6% | 29.6% to 52.2% | 10 | 0.003 |

| Greater than 70/100 000 live births | 40.4% | 34.6% to 46.2% | 49 | 17.8% | 9.4% to 28.2% | 11 | ||

| Neonatal mortality rate (SDG target 3.2.2)§ | ||||||||

| Less than 12/1000 live births | 31.3% | 27.3% to 35.4% | 58 | 0.033 | 37.7% | 27.4% to 48.5% | 9 | 0.036 |

| Greater than 12/1000 live births | 39.0% | 33.2% to 44.9% | 53 | 21.1% | 11.4% to 32.8% | 12 | ||

| Proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel (SDG target 3.1.2)¶ | ||||||||

| Less than 90% | 39.7% | 33.9% to 45.6% | 48 | 0.019 | 17.8% | 9.4% to 28.2% | 11 | 0.003 |

| Greater than 90% | 31.3% | 27.4% to 35.4% | 63 | 40.6% | 29.6% to 52.2% | 10 | ||

| Antenatal care coverage—at least four visits (global target)** | ||||||||

| Less than 90% | 37.1% | 32.0% to 42.4% | 65 | 0.104 | 23.8% | 15.1% to 33.6% | 15 | 0.107 |

| Greater than 90% | 31.5% | 27.2% to 36.0% | 51 | 38.8% | 23.7% to 55.0% | 6 | ||

*Pooled estimate.

†Number of studies included in each subgroup.

‡SDG target for maternal mortality rate=70/100 000 live births.43

§SDG target for neonatal mortality rate=12/1000 live births.43

¶SDG target for proportion of deliveries attended by skilled birth attendants=90%.44

**Global target for proportion of pregnant women with at least four antenatal care uptake=90%.45

††Estimated using a random effects model.

HM, herbal medicine; SDG, sustainable development goal.

Figure 2.

Pooled prevalence of pregnant women’s HM use. Forest plot of random effect meta-analysis. A total of 111 studies reporting the prevalence of pregnant women’s HM use were included for the pooled estimation of HM use. The black diamond dots and dashed line passing through represent the effect size and corresponding 95% CI reported in individual studies, and the green diamond on the bottom and the size of its lateral tips denote the pooled effect size and its 95% CI.

Figure 3.

Map of prevalence estimates of herbal medicine use by country. The 111 studies included in this review reported the prevalence of HM use across 51 different countries. Darker colours represent a higher prevalence of HM use.

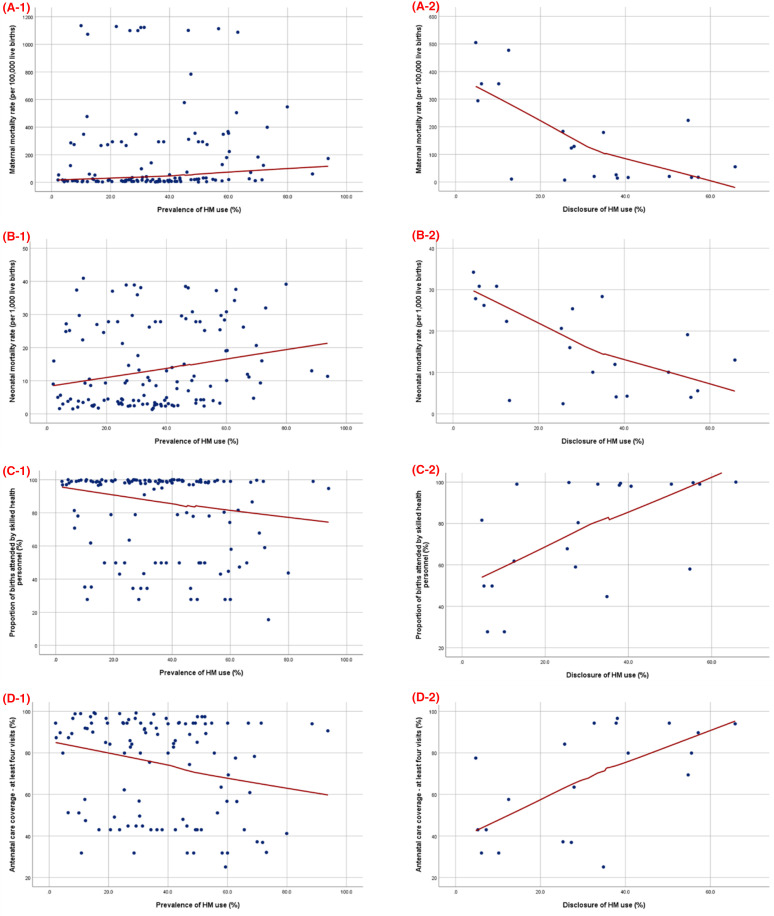

A comparison of HM use with various MCH indicators revealed that the prevalence was significantly higher in the countries that have not reached the SDG target for MMR (p=0.008), NMR (p=0.033) and SBA utilisation (p=0.019). Spearman’s correlation analysis also revealed a positive correlation between HM use and MMR (p=0.013) and NMR (p=0.011), while a negative correlation was found between HM use and SBA utilisation (p=0.033) and the coverage of at least four ANC visits (p=0.011; table 2 and figure 4).

Table 2.

Correlations between HM utilisation and disclose rate and MCH indicators

| Variables | HM utilisation | HM disclosure | ||

| Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rs) | P value | Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rs) | P value | |

| Maternal mortality rate | 0.222 | 0.013 | −0.545 | 0.013 |

| Neonatal mortality rate | 0.227 | 0.011 | −0.597 | 0.004 |

| Proportion of births attended by SBA | −0.190 | 0.033 | 0.587 | 0.005 |

| Antenatal care coverage—at least four visits | −0.243 | 0.011 | 0.581 | 0.007 |

HM, herbal medicine; MCH, maternal and child health; SBA, skilled birth attendant.

Figure 4.

Correlation between HM utilisation or disclosure rate (%) and MCH indicators. (A) maternal mortality rate (per 100 000 live births), (B) neonatal mortality rate (per 1000 live births), (C) the proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel (%) and (D) antenatal care coverage—at least four visits (%). Scatter plot between the prevalence of HM use or disclosure (x-axis) and MCH indicators (y-axis). The blue dots represent the estimation of various MCH indicators of the study setting at the time each study was conducted. The red line denotes the fitted line of each plot.

Pregnant women’s disclosure of HM use to their healthcare providers

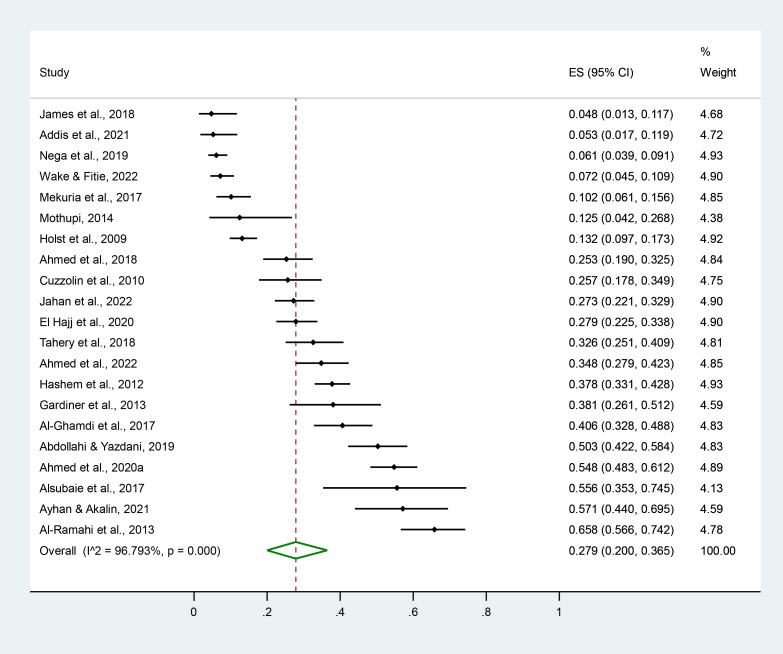

Overall, 27.9% (95% CI 20.0% to 36.5%) of pregnant women disclosed the HM use to their healthcare providers, ranging from 4.8% to 65.8% across different studies (table 1, figure 5).85 122 Geographical variations were significant (p<0.001), with the highest disclosure rate observed in the Eastern Mediterranean region (44.5%) and the lowest in Africa (9.7%).

Figure 5.

Pooled prevalence of pregnant women’s disclosure of HM use. Forest plot of random effect meta-analysis. Out of 111 studies on pregnant women’s HM use, 21 studies reported the HM disclose rate and were included for the pooled estimation of HM disclosure. The black diamond dots and dashed line passing through represent the effect size and corresponding 95% CI reported in individual studies, and the green diamond on the bottom and the size of its lateral tips denote the pooled effect size and its 95% CI.

The disclosure rate was significantly higher in the countries that achieved the SDG targets for MMR (p=0.003), NMR (p=0.036) and SBA utilisation (p=0.003). Furthermore, negative correlations were observed between the disclosure of HM use and both MMR (p=0.013) and NMR (p=0.004), whereas positive correlations were identified between HM disclosure and the utilisation of SBA (p=0.005) and achieving at least four ANC coverage (p=0.007; table 2 and figure 4).

Additional findings regarding patient–physician communication on HM use

A significant percentage of women (91.7%) reported that their physicians did not inquire about HM use during ANC consultations (table 3).122 Furthermore, the majority of pregnant women perceived the physicians’ response to HM disclosure as indifferent (35.3%), with a higher proportion of women receiving warnings about the harmful effects of HM (34.5%) rather than recommendations on HM use (8.0%).91 109 134 Lastly, the most commonly reported reasons for pregnant women to withhold information about their HM use were the perception that HM is harmless (53.6%) and the lack of inquiry from healthcare providers (39.4%).27 83 117 125 126 129 133 149 155 164

Table 3.

Additional findings related to disclosure of HM use

| Categories | No of studies | Findings | |

| Pooled estimate | Reported values | ||

| Inquired by healthcare providers regarding HM use | |||

| Yes | 1122 | 8.3% | 8.3%122 |

| No | 91.7% | 91.7%122 | |

| Physicians’ response regarding HM use | |||

| Showed indifference | 391 109 134 | 35.3% | 31.0%109, 40.0%91 |

| Advised them about harmful/side effects | 34.5% | 20.0%91, 49.0%109 | |

| Discouraged HM use | 28.1% | 7.0%109, 20.0%91, 57.4%134 | |

| Recommended herbal medicine use | 8.0% | 8.0%109 | |

| Discouraged the use of prescription medicine | 5.0% | 5.0%109 | |

| Level of satisfaction on patient-doctor communication on HM use | |||

| Very satisfied | 186 | 55.0% | 55.0%86 |

| Fairly satisfied | 27.0% | 27.0%86 | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 18.0% | 18.0%86 | |

| Not satisfied | 0.0% | 0.0%86 | |

| Reason for non-disclosure | |||

| HM is not harmful | 1027 83 117 125 126 129 133 149 155 164 | 53.6% | 31.0%126, 36.4%129, 93.3%125 |

| Healthcare providers did not ask | 39.4% | 3.0%126, 29.6%129, 30.7%117, 39.4%27, 51.7%149, 52.2%164, 69.2%83 | |

| Forgot to inform the doctor | 23.5% | 0.9%149, 4.0%126, 17.4%27, 32.2%164, 36.3%155, 51.2%117 | |

| It is not important to disclose | 21.6% | 3.3%164, 7.1%117, 18.0%126, 27.6%83, 29.4%27, 44.8%149 | |

| Routine use of HM | 16.0% | 16.0%83 | |

| Without any particular reason | 10.0% | 1.2%83, 19.0%126 | |

| Afraid of doctors’ response | 6.6% | 1.0%126, 3.6%83, 3.8%133, 9.4%117, 11.0%27, 12.2%164 | |

| Did not visit healthcare providers/used HM before visiting the doctor | 3.2% | 1.8%27, 2.0%126, 2.6%149, 6.8%83 | |

| Potential predictors of HM disclosure | 127 | secondary education level (OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.12 to 4.51), four or more visits to ANC (OR 3.74, 95% CI 1.41 to 9.91)27 | |

ANC, antenatal care; HM, herbal medicine.

Discussion

This review examined the pattern of HM use among pregnant women and highlighted the importance of discussing their use with healthcare providers. Due to potential toxicity concerns or dissatisfaction with conventional healthcare services, many individuals turn to natural remedies to address their unmet needs.91 117 133 Pregnant women from various countries rely on HM because they assume that HM is a safer alternative to conventional medicine, posing fewer risks to the developing fetus.171 172 This reliance is substantiated by the traditional practices and scientific validation of several herbs known for their efficacy in addressing physical discomfort during pregnancy.12 173 174 For example, ginger, peppermint and chamomile have proven effective in relieving nausea and vomiting,173 175–177 while cranberry consumption has demonstrated efficacy in preventing urinary tract infections.178 179 Furthermore, garlic has shown preventive properties against pre-eclampsia.174 Based on these perceived benefits, cultural beliefs and available scientific evidence, more than one-third of the women included in this review reported using at least one type of HM during pregnancy.

Nevertheless, despite the perceived safety and expectations associated with HM as a treatment option for pregnancy-related conditions, certain remedies were found to cause adverse effects and poor delivery outcomes when used inappropriately.9 62 180 Although ginger and chamomile are commonly used to alleviate morning sickness, inappropriate use of ginger can lead to stomach irritation, heartburn and even cardiac arrhythmias.27 62 117 181 Prolonged use of chamomile has been associated with a higher risk of preterm delivery and low birth weight.182 183 Furthermore, there is insufficient evidence to confirm the safety of many commonly used herbal products in pregnancy, requiring continued research.15 As such, herbs that are often consumed as food can also possess medicinal properties that may harm the health of pregnant women and their unborn children if used inappropriately. The consequences of inappropriate HM use are particularly profound during the first and third trimesters of pregnancy, as these stages are critical for fetal development and final maturation.174 184 185

To prevent inappropriate HM use, scholars have advocated the need for physicians to be aware of patients’ HM use and engage in open communication about self-care practices.27 73 186 Previous studies have shown that open communication regarding patients’ self-medication through medication reconciliation helped to reduce the risk of adverse drug interactions and medication errors.187 188 Improved patient–doctor communication was also associated with better patient health outcomes.189 190 Similarly, promoting transparent and effective communication between pregnant women and their healthcare providers about self-care activities could serve as a non-medical approach to lower the risk of adverse effects and unfavourable MCH outcomes. Furthermore, as culturally competent and patient-centred care is linked to increased utilisation of essential MCH services,191 physicians can improve the uptake of ANC services by recognising and understanding pregnant women’s health beliefs and practices through non-judgmental communication about HM use.

However, less than one-third of the pregnant HM users discussed their use with healthcare providers, highlighting the need for effective patient–doctor communication regarding the use of additional medical treatments. Significantly higher rates of HM disclosure were observed in countries with better MCH outcomes, as characterised by lower MMR and NMR and a higher proportion of births attended by SBA. Furthermore, a positive correlation was identified between the attendance of four or more ANC sessions and an increased disclosure of HM. This suggests a potential correlation between pregnant women’s disclosure of HM use and the availability of quality maternal healthcare services, along with better patient–doctor communication. Previous studies have already established a positive association between the disclosure of CAM use and more physician visits, as well as a higher quality of the patient–doctor relationship.192–194 Having four or more ANC visits was also identified as a potential predictor of HM disclosure during pregnancy.27 These findings illustrate the importance of ANC coverage, as it is a foundation for ensuring maternal health. ANC visits provide an opportunity to regularly check pregnant women’s health, discuss any health-related concerns and exchange health information.23 195 196 Routine ANC visits can also facilitate effective patient–doctor dialogue about HM use and help prevent inappropriate use of HM.27 180

In addition, healthcare providers were found to play a crucial role in bridging communication gaps related to HM use.83 104 197–199 Most women reported the perception of HM being harmless126 129 and the lack of inquiry from their physicians regarding the use of additional healthcare modalities. as the reasons for not disclosing HM use.27 83 117 126 129 However, up to 92% of women were willing to discuss HM use if their doctor inquired them about the use, and 70% of women desired HM-related information from their doctors.113 197 These findings highlight the importance of healthcare providers initiating the discussions about HM use in an unbiased manner and providing evidence-based feedback to ensure appropriate HM use.18 197 Moreover, these conversations should begin early in pregnancy, as HM use during the first trimester can have critical implications for fetal health and development.10 184 200 Lastly, further research is needed to explore the relationship between the practice of open dialogue between pregnant women and physicians on HM use and the corresponding pregnancy outcomes to determine whether improved patient–physician communication could potentially predict the reduction in unfavourable pregnancy outcomes.

The following limitations can be found in this review. First, the inclusion criteria of the reviewed studies were limited to English-language, which may have restricted the overall representation of HM use during pregnancy. However, efforts were made to minimise the omission of potentially relevant literature by reviewing the references of included studies. Second, the studies included in this review were primarily conducted in a single health facility using non-random sampling methods, impacting the generalisability of the findings. Furthermore, the variation and limited number of studies representing each geographical region hindered the examination of regional differences in subgroup meta-analysis of HM use and disclosure rate. Additionally, differences in the sample sizes and to whom the women disclosed their HM use existed across the studies, with some studies examining HM disclosure to physicians only and others also including midwives and health workers. Thus, these variations must be considered when interpreting the results of this review. However, despite these limitations, this systematic review and meta-analysis estimated the global prevalence of HM use during pregnancy and provided valuable insights into the patterns of HM disclosure among pregnant populations.

Conclusion

Lack of communication on HM use between pregnant women and obstetric care providers was correlated with unfavourable MCH outcomes, highlighting the need for prevention efforts across various health sectors to promote open communication about self-care practices during ANC and to encourage physicians to provide guidance on the safe and appropriate use of HM. These prevention initiatives could include advocating training for healthcare professionals working with pregnant mothers on the therapeutic effects of commonly used HM, implementing community outreach programmes to raise awareness of HM’s potential toxicity and integrating questions about HM use into routine antenatal case-taking procedures. Finally, additional research is needed to understand the factors influencing open patient–physician communication on HM use during ANC and to develop strategies for overcoming communication barriers to promote culturally responsive and integrative maternity care.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prof. Nam, Eun Woo (Hanyang University, Seoul, Korea) for providing invaluable guidance in the statistical analysis of this research. Also, we would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments and feedback.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: The systematic review was conceived and designed by HBI and DH. HBI, DC and SJC extracted and analysed the data. HBI and JHH drafted the manuscript. HBI, JHH and DH critically reviewed the manuscript and contributed intellectual content. DH accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish as a guarantor. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Map disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on this map does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. This map is provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. All datasets generated and analysed, including the study protocol, search strategy, list of the included and excluded studies, data extracted, analysis plans, quality assessment, and assessment of the publication bias will be accessible by contacting the corresponding author of this study.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Davis DC. The discomforts of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 1996;25:73–81. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1996.tb02516.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ertmann RK, Nicolaisdottir DR, Kragstrup J, et al. Physical discomfort in early pregnancy and postpartum depressive symptoms. Nord J Psychiatry 2019;73:200–6. 10.1080/08039488.2019.1579861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heitmann K, Nordeng H, Havnen GC, et al. The burden of nausea and vomiting during pregnancy: severe impacts on quality of life, daily life functioning and willingness to become pregnant again–results from a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:75. 10.1186/s12884-017-1249-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aljoher AM, Alsaeed MA, Alkhlfan MA. Pregnant women risk perception of medications and natural products use during pregnancy in Alahsa, Saudi Arabia. Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine 2018;70:13–20. 10.12816/0042956 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lupattelli A, Picinardi M, Cantarutti A, et al. Use and intentional avoidance of prescribed medications in pregnancy: a cross-sectional, web-based study among 926 women in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:3830. 10.3390/ijerph17113830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alyami HS, Orabi MAA, Aldhabbah FM, et al. Knowledge about COVID-19 and beliefs about and use of Herbal products during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J 2020;28:1326–32. 10.1016/j.jsps.2020.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lam CS, Koon HK, Chung VC-H, et al. A public survey of traditional, complementary and integrative medicine use during the COVID-19 outbreak in Hong Kong. PLoS One 2021;16:e0253890. 10.1371/journal.pone.0253890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . WHO consolidated guideline on self-care interventions for health: sexual and reproductive health and rights: World Health Organization, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmed M, Hwang JH, Choi S, et al. Safety classification of herbal medicines used among pregnant women in Asian countries: a systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017;17:489. 10.1186/s12906-017-1995-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruno LO, Simoes RS, de Jesus Simoes M, et al. Pregnancy and Herbal medicines: an unnecessary risk for women’s health—a narrative review. Phytother Res 2018;32:796–810. 10.1002/ptr.6020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zamawe C, King C, Jennings HM, et al. Associations between the use of Herbal medicines and adverse pregnancy outcomes in rural Malawi: a secondary analysis of randomised controlled trial data. BMC Complement Altern Med 2018;18:166. 10.1186/s12906-018-2203-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernstein N, Akram M, Yaniv-Bachrach Z, et al. Is it safe to consume traditional medicinal plants during pregnancy. Phytother Res 2021;35:1908–24. 10.1002/ptr.6935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennedy DA, Lupattelli A, Koren G, et al. Safety classification of Herbal medicines used in pregnancy in a multinational study. BMC Complement Altern Med 2016;16:102. 10.1186/s12906-016-1079-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Im HB, Ghelman R, Portella CFS, et al. Assessing the safety and use of medicinal herbs during pregnancy: a cross-sectional study in São Paulo. Front Pharmacol 2023;14:1268185. 10.3389/fphar.2023.1268185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarecka-Hujar B, Szulc-Musioł B. Herbal medicines—are they effective and safe during pregnancy. Pharmaceutics 2022;14:171. 10.3390/pharmaceutics14010171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim A, Cranswick N, South M. Adverse events associated with the use of complementary and alternative medicine in children. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:297–300. 10.1136/adc.2010.183152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ventola CL. Current issues regarding complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in the United States: part 1: the widespread use of CAM and the need for better-informed health care professionals to provide patient counseling. P T 2010;35:461–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pappas S, Perlman A. Complementary and alternative medicine: the importance of doctor-patient communication. Med Clin North Am 2002;86:1–10. 10.1016/s0025-7125(03)00068-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akhtar K, Akhtar K, Rahman MM. Use of alternative medicine is delaying health-seeking behavior by Bangladeshi breast cancer patients. Eur J Breast Health 2018;14:166–72. 10.5152/ejbh.2018.3929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brienza RS, Stein MD, Fagan MJ. Delay in obtaining conventional healthcare by female internal medicine patients who use herbal therapies. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2002;11:79–87. 10.1089/152460902753473499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ackumey MM, Gyapong M, Pappoe M, et al. Socio-cultural determinants of timely and delayed treatment of Buruli ulcer: implications for disease control. Infect Dis Poverty 2012;1:6. 10.1186/2049-9957-1-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapman RR. Endangering safe motherhood in mozambique: prenatal care as pregnancy risk. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:355–74. 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00363-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tengia-Kessy A, Msalale GC. Understanding forgotten exposures towards achieving sustainable development goal 3: a cross‐sectional study on herbal medicine use during pregnancy or delivery in Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21:270. 10.1186/s12884-021-03741-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muteebwa L, Ssetaala A, Muramuzi D, et al. Factors associated with herbal medicine use in pregnancy among postnatal mothers in Mbarara regional referral hospital in Western Uganda. In Review [Preprint] 2021. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-141153/v1 [DOI]

- 25.Tayie F, Lartey A. Antenatal care and pregnancy outcome in Ghana, the importance of Women\’s education. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development 2008;8:291–303. 10.4314/ajfand.v8i3.19193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saaka M, Sulley I. Independent and joint contributions of inadequate antenatal care timing, contacts and content to adverse pregnancy outcomes. Ann Med 2023;55:2197294. 10.1080/07853890.2023.2197294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed M, Im HB, Hwang JH, et al. Disclosure of herbal medicine use to health care providers among pregnant women in Nepal: a cross-sectional study. BMC Complement Med Ther 2020;20:339. 10.1186/s12906-020-03142-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McIntyre E, Foley H, Diezel H, et al. Development and preliminarily validation of the complementary medicine disclosure index. Patient Educ Couns 2020;103:1237–44. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strouss L, Mackley A, Guillen U, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in women during pregnancy: do their healthcare providers know. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:85. 10.1186/1472-6882-14-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foley H, Steel A, Cramer H, et al. Disclosure of complementary medicine use to medical providers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2019;9:1573. 10.1038/s41598-018-38279-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ee C, Levett K, Smith C, et al. Complementary medicines and therapies in clinical guidelines on pregnancy care: a systematic review. Women Birth 2022;35:e303–17. 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson A, McGrail MR. Disclosure of CAM use to medical practitioners: a review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Complement Ther Med 2004;12:90–8. 10.1016/j.ctim.2004.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelak JA, Cheah WL, Safii R. Patient’s decision to disclose the use of traditional and complementary medicine to medical doctor: a descriptive phenomenology study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2018;2018:4735234. 10.1155/2018/4735234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis EL, Oh B, Butow PN, et al. Cancer patient disclosure and patient-doctor communication of complementary and alternative medicine use: a systematic review. Oncologist 2012;17:1475–81. 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallen GR, Brooks AT. To tell or not to tell: shared decision making, CAM use and disclosure among Underserved patients with rheumatic diseases. Integr Med Insights 2012;7:15–22. 10.4137/IMI.S10333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muñoz Balbontín Y, Stewart D, Shetty A, et al. Herbal medicinal product use during pregnancy and the postnatal period: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2019;133:920–32. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pallivalappila AR, Stewart D, Shetty A, et al. Complementary and alternative medicines use during pregnancy: a systematic review of pregnant women and healthcare professional views and experiences. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:205639. 10.1155/2013/205639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmed SM, Nordeng H, Sundby J, et al. The use of medicinal plants by pregnant women in Africa: a systematic review. J Ethnopharmacol 2018;224:297–313. 10.1016/j.jep.2018.05.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hall HG, Griffiths DL, McKenna LG. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by pregnant women: a literature review. Midwifery 2011;27:817–24. 10.1016/j.midw.2010.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 2021;134:178–89. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frass M, Strassl RP, Friehs H, et al. Use and acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine among the general population and medical personnel: a systematic review. Ochsner J 2012;12:45–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of Interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:934–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.United Nations . Goal 3: ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. n.d. Available: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/

- 44.Damian DJ, Tibelerwa JY, John B, et al. Factors influencing utilization of skilled birth attendant during childbirth in the Southern Highlands, Tanzania: a multilevel analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020;20:420. 10.1186/s12884-020-03110-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.World Health Organization . New global targets to prevent maternal deaths. 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-10-2021-new-global-targets-to-prevent-maternal-deaths

- 46.World Health Organization Data Platform . Maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health and ageing data portal World Health Organization. 2023. Available: https://platform.who.int/data/maternal-newborn-child-adolescent-ageing/indicator-explorer-new

- 47.UNICEF Data Warehouse . Data warehouse: UNICEF. n.d. Available: https://data.unicef.org/dv_index/

- 48.World Bank open data. 2023. Available: https://data.worldbank.org/

- 49.Bayati M, Akbarian R, Kavosi Z. Determinants of life expectancy in Eastern Mediterranean region: a health production function. Int J Health Policy Manag 2013;1:57–61. 10.15171/ijhpm.2013.09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miladinov G. Socioeconomic development and life expectancy relationship: evidence from the EU accession candidate countries. Genus 2020;76:1–20. 10.1186/s41118-019-0071-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sattari M, Dilmaghanizadeh M, Hamishehkar H, et al. Self-reported use and attitudes regarding herbal medicine safety during pregnancy in Iran. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod 2012;7:45–9. 10.5812/jjnpp.3416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bayisa B, Tatiparthi R, Mulisa E. Use of Herbal medicine among pregnant women on antenatal care at Nekemte hospital, Western Ethiopia. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod 2014;9:e17368. 10.17795/jjnpp-17368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Araújo CRF, Santiago FG, Peixoto MI, et al. Use of medicinal plants with teratogenic and abortive effects by pregnant women in a city in northeastern Brazil. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2016;38:127–31. 10.1055/s-0036-1580714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elkhoudri N, Baali A, Amor H. Maternal morbidity and the use of medicinal herbs in the city of Marrakech, Morocco. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge 2016;15:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zaitoun MF, Al-Nowis ME, Alhumaidhan FY, et al. Use of herbs among pregnant women in Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research 2019;11:2105–8. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aljofan M, Alkhamaiseh S. Prevalence and factors influencing use of herbal medicines during pregnancy in hail, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2020;20:e71–6. 10.18295/squmj.2020.20.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Almoayad F, Assiri IA, Almarshoud HF, et al. Exploring the use of herbal treatments during pregnancy among Saudi women: an application of the knowledge-attitude-practice model. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2021;21:591–7. 10.18295/squmj.4.2021.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nnaemeka OD, Chioma Phyllis N, Confidence Chinaza O. The use of herbal medicines in pregnancy: a cross-sectional analytic study. International Journal of Scientific Research in Dental and Medical Sciences 2021;3:66–72. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beşiroğlu R, Şahin AK, Karatas Kocberber E, et al. Evaluation of medication and herbal product use among pregnant women. Actapharm 2021;59:575–88. 10.23893/1307-2080.APS.05936 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ahmad Saleh OB, Nasir A, Fatima N, et al. Incidence of herbal use among pregnant women attending family care center. PJMHS 2022;16:779–81. 10.53350/pjmhs221610779 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hepner DL, Harnett M, Segal S, et al. Herbal medicine use in parturients. Anesth Analg 2002;94:690–3. 10.1097/00000539-200203000-00039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pinn G, Pallett L. Herbal medicine in pregnancy. Complement Ther Nurs Midwifery 2002;8:77–80. 10.1054/ctnm.2001.0620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nordeng H, Havnen GC. Use of herbal drugs in pregnancy: a survey among 400 Norwegian women. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2004;13:371–80. 10.1002/pds.945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Forster DA, Denning A, Wills G, et al. Herbal medicine use during pregnancy in a group of Australian women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2006;6:21. 10.1186/1471-2393-6-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sawalha AF. Consumption of prescription and non-prescription medications by pregnant women: a cross sectional study in Palestine. IUG Journal of Natural Studies 2007;15. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ologe MO, Aboyeji AP, Ijaiya MA, et al. Herbal use among pregnant mothers in Ilorin, Kwra state, Nigeria. J Obstet Gynaecol 2008;28:720–1. 10.1080/01443610802461912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rahman AA, Sulaiman SA, Ahmad Z, et al. Prevalence and pattern of use of herbal medicines during pregnancy in Tumpat district, Kelantan. Malays J Med Sci 2008;15:40–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chuang C-H, Chang P-J, Hsieh W-S, et al. Chinese herbal medicine use in Taiwan during pregnancy and the postpartum period: a population-based cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46:787–95. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fakeye TO, Adisa R, Musa IE. Attitude and use of herbal medicines among pregnant women in Nigeria. BMC Complement Altern Med 2009;9:53. 10.1186/1472-6882-9-53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Holst L, Wright D, Haavik S, et al. The use and the user of herbal remedies during pregnancy. J Altern Complement Med 2009;15:787–92. 10.1089/acm.2008.0467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rahman AA, Sulaiman SA, Ahmad Z, et al. Women’s attitude and sociodemographic characteristics influencing usage of Herbal medicines during pregnancy in Tumpat district, Kelantan. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2009;40:330–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bercaw J, Maheshwari B, Sangi-Haghpeykar H. The use during pregnancy of prescription, over-the-counter, and alternative medications among Hispanic women. Birth 2010;37:211–8. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00408.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cuzzolin L, Francini-Pesenti F, Verlato G, et al. Use of herbal products among 392 Italian pregnant women: focus on pregnancy outcome. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2010;19:1151–8. 10.1002/pds.2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lapi F, Vannacci A, Moschini M, et al. Use, attitudes and knowledge of complementary and alternative drugs (Cads) among pregnant women: a preliminary survey in Tuscany. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2010;7:477–86. 10.1093/ecam/nen031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nordeng H, Ystrøm E, Einarson A. Perception of risk regarding the use of medications and other exposures during pregnancy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2010;66:207–14. 10.1007/s00228-009-0744-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pereira LMP, Nayak BS, Abdul-Lateef H, et al. Drug utilization patterns in pregnant women a case study at the mount hope women’s hospital in Trinidad, West Indies. West Indian Med J 2010;59:561–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bello FA, Morhason-Bello IO, Olayemi O, et al. Patterns and predictors of self-medication amongst antenatal clients in Ibadan, Nigeria. Niger Med J 2011;52:153–7. 10.4103/0300-1652.86124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kalder M, Knoblauch K, Hrgovic I, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine during pregnancy and delivery. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011;283:475–82. 10.1007/s00404-010-1388-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nordeng H, Bayne K, Havnen GC, et al. Use of Herbal drugs during pregnancy among 600 Norwegian women in relation to concurrent use of conventional drugs and pregnancy outcome. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2011;17:147–51. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tabatabaee M. Use of Herbal medicine among pregnant women referring to Valiasr hospital in Kazeroon, Fars, south of Iran. Journal of Medicinal Plants 2011;10:96–108. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tamuno I, Omole-Ohonsi A, Fadare J. Use of herbal medicine among pregnant women attending a tertiary hospital in northern Nigeria. IJGO 2011;15. 10.5580/2932 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yusuff KB, Omarusehe LD. Determinants of self medication practices among pregnant women in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int J Clin Pharm 2011;33:868–75. 10.1007/s11096-011-9556-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hashem Dabaghian F, Abdollahi Fard M, Shojaei A, et al. Use and attitude on herbal medicine in a group of pregnant women in Tehran. Journal of Medicinal Plants 2012;11:22–33. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Khadivzadeh T, Ghabel M. Complementary and alternative medicine use in pregnancy in Mashhad, Iran, 2007-8. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 2012;17:263–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Al-Ramahi R, Jaradat N, Adawi D. Use of Herbal medicines during pregnancy in a group of Palestinian women. J Ethnopharmacol 2013;150:79–84. 10.1016/j.jep.2013.07.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gardiner P, Jarrett K, Filippelli A, et al. Herb use, vitamin use, and diet in low-income, postpartum women. J Midwifery Womens Health 2013;58:150–7. 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2012.00240.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kennedy DA, Lupattelli A, Koren G, et al. Herbal medicine use in pregnancy: results of a multinational study. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013;13:355. 10.1186/1472-6882-13-355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Teoh CS, M H I A, W M WFS, et al. Herbal ingestion during pregnancy and post-partum period is a cause for concern. Med J Malaysia 2013;68:157–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Emmanuel A, Achema G, Afoi BB, et al. Self medicaltion practice among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in selected hospitals in JOS, Nigeria. International Journal of Nursing and Health Science 2014;1:55–9. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hall HR, Jolly K. Women’s use of complementary and alternative medicines during pregnancy: a cross-sectional study. Midwifery 2014;30:499–505. 10.1016/j.midw.2013.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mothupi MC. Use of herbal medicine during pregnancy among women with access to public healthcare in Nairobi, Kenya: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:432. 10.1186/1472-6882-14-432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Orief YI, Farghaly NF, Ibrahim MIA. Use of herbal medicines among pregnant women attending family health centers in Alexandria. Middle East Fertility Society Journal 2014;19:42–50. 10.1016/j.mefs.2012.02.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pallivalappila AR, Stewart D, Shetty A, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use during early pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2014;181:251–5. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zaki NM, Albarraq AA. Use, attitudes and knowledge of medications among pregnant women: a Saudi study. Saudi Pharm J 2014;22:419–28. 10.1016/j.jsps.2013.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Adusi-Poku Y, Vanotoo L, Detoh EK, et al. Type of herbal medicines utilized by pregnant women attending ante-natal clinic in Offinso North district: are orthodox prescribers aware. Ghana Med J 2015;49:227. 10.4314/gmj.v49i4.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Afshary P, Mohammadi S, Najar S, et al. Prevalence and causes of self-medication in pregnant women referring to health centers in Southern of Iran. Int J Pharm Sci Res 2015;6:612. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ali-Shtayeh MS, Jamous RM, Jamous RM. Plants used during pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and infant healthcare in Palestine. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2015;21:84–93. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bello UL, Isah J. Use of herbal medicines and aphrodisiac substances among women in Kano state, Nigeria. IOSR J Nursing Health Sci 2015;4:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Elberry AA, Alahdal AA, Almohamadi AM, et al. Evaluation of the use of non-prescribed medications and herbs by pregnant women. Life Sci J 2015;12. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mugomeri E, Seliane K, Chatanga P, et al. Identifying promoters and reasons for medicinal herb usage during pregnancy in Maseru, Lesotho. AJNM 2015;17:4–16. 10.25159/2520-5293/63 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nergard CS, Ho TPT, Diallo D, et al. Attitudes and use of medicinal plants during pregnancy among women at health care centers in three regions of Mali, West-Africa. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 2015;11:73. 10.1186/s13002-015-0057-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pallivalapila AR, Stewart D, Shetty A, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicines during the third trimester. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:204–11. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hanafy SA, Sallam SA, Kharboush IF, et al. Drug utilization pattern during pregnancy in Alexandria, Egypt. Eur J Pharm Med Res 2016;3:19–29. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hwang JH, Kim Y-R, Ahmed M, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in pregnancy: a cross-sectional survey on Iraqi women. BMC Complement Altern Med 2016;16:191. 10.1186/s12906-016-1167-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Laelago T, Yohannes T, Lemango F. Prevalence of herbal medicine use and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at public health facilities in Hossana town, Southern Ethiopia: facility based cross sectional study. Arch Public Health 2016;74:7. 10.1186/s13690-016-0118-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mbarambara PM, Songa PB, Wansubi LM, et al. Self-medication practice among pregnant women attending antenatal care at health centers in Bukavu, Eastern DR Congo. Int J Innov Appl Stud 2016;16:38. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Varghese BM, K V, Banu R. Assessment of drug usage pattern during pregnancy at a tertiary care teaching hospital. IJMEDPH 2016;6:130–5. 10.5530/ijmedph.2016.3.7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yusof J, Mahdy ZA, Noor RM. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in pregnancy and its impact on obstetric outcome. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2016;25:155–63. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2016.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Al-Ghamdi S, Aldossari K, Al-Zahrani J, et al. Prevalence, knowledge and attitudes toward Herbal medication use by Saudi women in the central region during pregnancy, during labor and after delivery. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017;17:196. 10.1186/s12906-017-1714-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Alsubaie SF, Alshehri MG, Ghalib RH. Awareness, use, and attitude towards herbal medicines among Saudi women-cross sectional study. Imp J Interdiscip Res 2017;3:285–90. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Barišić T, Pecirep A, Milićević R, et al. What do pregnant women know about harmful effects of medication and Herbal remedies use during pregnancy? Psychiatr Danub 2017;29 Suppl 4:804–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cabut S, Marie C, Vendittelli F, et al. Intended and actual use of self-medication and alternative products during pregnancy by French women. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 2017;46:167–73. 10.1016/j.jogoh.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kıssal A, Çevik Güner Ü, Batkın Ertürk D. Use of Herbal product among pregnant women in Turkey. Complement Ther Med 2017;30:54–60. 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Koç Z, Sağlam Z, Topatan S. Determination of the usage of complementary and alternative medicine among pregnant women in the northern region of Turkey. Collegian 2017;24:533–9. 10.1016/j.colegn.2016.11.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mekuria AB, Erku DA, Gebresillassie BM, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of Herbal medicine use among pregnant women on antenatal care follow-up at University of Gondar referral and teaching hospital, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017;17:86. 10.1186/s12906-017-1608-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Onyiapat J-L, Okafor C, Okoronkwo I, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use: results from a descriptive study of pregnant women in Udi local government area of Enugu state, Nigeria. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017;17:189. 10.1186/s12906-017-1689-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ahmed M, Hwang JH, Hasan MA, et al. Herbal medicine use by pregnant women in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. BMC Complement Altern Med 2018;18:333. 10.1186/s12906-018-2399-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Alonso-Castro AJ, Ruiz-Padilla AJ, Ruiz-Noa Y, et al. Self-medication practice in pregnant women from central Mexico. Saudi Pharm J 2018;26:886–90. 10.1016/j.jsps.2018.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kwame Ameade EP, Zakaria AP, Abubakar L, et al. Herbal medicine usage before and during pregnancy—a study in northern Ghana. IJCAM 2018;11:235–42. 10.15406/ijcam.2018.11.00405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Botyar M, Kashanian M, Abadi ZRH, et al. A comparison of the frequency, risk factors, and type of self-medication in pregnant and nonpregnant women presenting to Shahid Akbar Abadi teaching hospital in Tehran. J Family Med Prim Care 2018;7:124–9. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_227_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Jambo A, Mengistu G, Sisay M, et al. Self-medication and contributing factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at public hospitals of Harar town, Ethiopia. Front Pharmacol 2018;9:1063. 10.3389/fphar.2018.01063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.James PB, Bah AJ, Tommy MS, et al. Herbal medicines use during pregnancy in Sierra Leone: an exploratory cross-sectional study. Women Birth 2018;31:e302–9. 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Marwa KJ, Njalika A, Ruganuza D, et al. Self-medication among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic at Makongoro health centre in Mwanza, Tanzania: a challenge to health systems. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:16. 10.1186/s12884-017-1642-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Rafiee A, Moradi Gomyek H, Haghighizade MH, et al. Self-treatment during pregnancy and its related factors. J Holist Nurs Midwifery 2018;28:129–35. 10.29252/hnmj.28.2.129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tahery N, Mahmodi N, Shirzadegan R. The prevalence and causes of herbal drug use in pregnant women referring to Abadan health centers; a cross-sectional study in Southwest Iran. Journal of Preventive Epidemiology 2018;3:e16–e. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Abdollahi F, Yazdani Chareti J. The relationship between women’s characteristics and herbal medicines use during pregnancy. Women Health 2019;59:579–90. 10.1080/03630242.2017.1421285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Al Essa M, Alissa A, Alanizi A, et al. Pregnant women’s use and attitude toward herbal, vitamin, and mineral supplements in an academic tertiary care center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J 2019;27:138–44. 10.1016/j.jsps.2018.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Biazar G, Naderi Nabi B, Sedighinejad A, et al. Herbal products use during pregnancy in north of Iran. International Journal of Women’s Health and Reproduction Sciences 2019;7:134–7. 10.15296/ijwhr.2019.21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Nega SS, Bekele HM, Meles GG, et al. Medicinal plants and concomitant use with pharmaceutical drugs among pregnant women. J Altern Complement Med 2019;25:427–34. 10.1089/acm.2018.0062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Saber M, Khanjani N, Zamanian M, et al. Use of medicinal plants and synthetic medicines by pregnant women in Kerman, Iran. Arch Iran Med 2019;22:390–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Yazdi N, Salehi A, Vojoud M, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in pregnant women: a cross-sectional survey in the south of Iran. J Integr Med 2019;17:392–5. 10.1016/j.joim.2019.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ahmed SM, Sundby J, Aragaw YA, et al. Self-medication and safety profile of medicines used among pregnant women in a tertiary teaching hospital in Jimma, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:3993. 10.3390/ijerph17113993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.El Hajj M, Sitali DC, Vwalika B, et al. Herbal medicine use among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in Lusaka province, Zambia: a cross-sectional, Multicentre study. Complement Ther Clin Pract 2020;40:101218. 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kekana LS, Sebitloane MH. Ingestion of herbal medication during pregnancy and adverse perinatal outcomes. S Afr J OG 2020;26:71. 10.7196/sajog.1615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Obadeji ST, Obadeji A, Bamidele JO, et al. Medication use among pregnant women at a secondary health institution: utilisation patterns and predictors of quantity. Afr Health Sci 2020;20:1206–16. 10.4314/ahs.v20i3.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Pakseresht S, Khalili Sherehjini A, Rezaei S, et al. Self-medication and its related factors in pregnant women: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Midwifery and Reproductive Health 2020;8:2359–67. [Google Scholar]

- 137.Sema FD, Addis DG, Melese EA, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of self-medication among pregnant women on antenatal care follow-up at University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital in Gondar, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Reprod Med 2020;2020:2936862. 10.1155/2020/2936862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Tuha A, Faris AG, Mohammed SA, et al. Self-medication and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Kemisie general hospital, North East Ethiopia. Patient Prefer Adherence 2020;14:1969–78. 10.2147/PPA.S277098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Adama S, Wallace LJ, Arthur J, et al. Self-medication practices of pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in northern Ghana: an analytical cross-sectional study. Afr J Reprod Health 2021;25:89–98. 10.29063/ajrh2021/v25i4.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ake SF, Yimam GN, Bekele NA. Self-medication and its predictors among pregnant women in Gedeo zone, South Ethiopia. J Basic Clin Pharm 2021;12:60–6. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Alsous MM, I Al-Azzam S, Nusair MB, et al. Self-medication among pregnant women attending outpatients' clinics in northern Jordan-a cross-sectional study. Pharmacol Res Perspect 2021;9:e00735. 10.1002/prp2.735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Ayhan Y, Akalın Uruşak E. Evaluation of Herbal medicine use in the obstetric and Gynecology Department. Ijp 2021;51:243–55. 10.26650/IstanbulJPharm.2020.0064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Babatunde OA, Adeoye IA, Usman AB, et al. Pattern and determinants of self-medication among pregnant women attending Antenatal clinics in primary health care facilities in Ogbomoso, Oyo state, Nigeria. Journal of Interventional Epidemiology and Public Health 2021;4. 10.37432/jieph.2021.4.3.36 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Bekele G, Gonfa D. Prevalence of Herbal medicine utilization and associated factors among pregnant women in Shashamane town, Southern Ethiopia, 2020; challenge to health care service delivery. J Women’s Health Care 2021;10:2167–0420. [Google Scholar]

- 145.da Matta R, Borges JL, Landi UN, et al. Ethno-Epidemiological study of medicinal products and medicinal plants use among pregnant women. BLACPMA 2021;20:71–80. 10.37360/blacpma.21.20.1.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Emiru YK, Adamu BA, Erara M, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in a pregnant population, Northwest Ethiopia. Int J Reprod Med 2021;2021:8829313. 10.1155/2021/8829313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Karimian Z, Sadat Z, Afshar B, et al. Predictors of self-medication with herbal remedies during pregnancy based on the theory of planned behavior in Kashan, Iran. BMC Complement Med Ther 2021;21:211. 10.1186/s12906-021-03353-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Quzmar Y, Istiatieh Z, Nabulsi H, et al. The use of complementary and alternative medicine during pregnancy: a cross-sectional study from Palestine. BMC Complement Med Ther 2021;21:108. 10.1186/s12906-021-03280-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Ahmed M, Hwang JH, Ali MN, et al. Irrational use of selected herbal medicines during pregnancy: a pharmacoepidemiological evidence from Yemen. Front Pharmacol 2022;13:926449. 10.3389/fphar.2022.926449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Alemu Anteneh T, Aklilu Solomon A, Tagele Tamiru A, et al. Knowledge and attitude of women towards herbal medicine usage during pregnancy and associated factors among mothers who gave birth in the last twelve months in Dega Damot district, Northwest Ethiopia. Drug Healthc Patient Saf 2022;14:37–49. 10.2147/DHPS.S355773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Barnes LAJ, Rolfe MI, Barclay L, et al. Demographics, health literacy and health locus of control beliefs of Australian women who take complementary medicine products during pregnancy and breastfeeding: a cross-sectional, online, national survey. Health Expect 2022;25:667–83. 10.1111/hex.13414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Terzioğlu Bebitoğlu B, Hıdıroğlu S, Ayaz Bilir R, et al. Investigation of medication use patterns among pregnant women attending a tertiary referral hospital. Ijp 2022;52:90–5. 10.26650/IstanbulJPharm.2022.980889 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Belayneh YM, Yoseph T, Ahmed S. A cross-sectional study of herbal medicine use and contributing factors among pregnant women on antenatal care follow-up at Dessie referral hospital, northeast Ethiopia. BMC Complement Med Ther 2022;22:146. 10.1186/s12906-022-03628-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Elba F, Hilmanto D, Poddar S. Factors influencing the use of Herbal medications during pregnancy at public health center, Indonesia. J Public Health Res 2022;11:22799036221139939. 10.1177/22799036221139939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 155.Jahan S, Mozumder ZM, Shill DK. Use of Herbal medicines during pregnancy in a group of Bangladeshi women. Heliyon 2022;8:e08854. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e08854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Kahssay SW, Tadege G, Muhammed F. Self-medication practice with modern and herbal medicines and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at Mizan-Tepi University teaching hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022;8:e10398. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Kamel N, El Boullani R, Cherrah Y. Use of medicinal plants during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum in Southern Morocco. Healthcare (Basel) 2022;10:2327. 10.3390/healthcare10112327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Mohamud M. Herbal medicine use and contributing factors among pregnant women at Shiek Hassan Yabare referral hospital in Jigjiga town, Eastern Ethiopia. Australas Med J 2022;15:406–12. [Google Scholar]

- 159.Tesfaye M, Solomon N, Getachew D, et al. Prevalence of harmful traditional practices during pregnancy and associated factors in Southwest Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022;12:e063328. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Wake GE, Fitie GW. Magnitude and determinant factors of Herbal medicine utilization among mothers attending their antenatal care at public health institutions in Debre Berhan town, Ethiopia. Front Public Health 2022;10:883053. 10.3389/fpubh.2022.883053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Isiiko J, Kiptoo J, Yadesa TM, et al. Potentially harmful medication use and the associated factors among pregnant women visiting antenatal care clinics in Mbarara regional referral hospital, Southwestern Uganda. J Clin Transl Res 2023;9:16–25. 10.18053/jctres.09.202301.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Beyene KG, Beza SW. Self-medication practice and associated factors among pregnant women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Trop Med Health 2018;46:10. 10.1186/s41182-018-0091-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Gbagbo FY, Nkrumah J. Implications of self-medication in pregnancy for safe motherhood and sustainable development Goal-3 in selected Ghanaian communities. Public Health Pract (Oxf) 2020;1:100017. 10.1016/j.puhip.2020.100017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Addis GT, Workneh BD, Kahissay MH. Herbal medicines use and associated factors among pregnant women in Debre Tabor town, North West Ethiopia: a mixed method approach. BMC Complement Med Ther 2021;21:268. 10.1186/s12906-021-03439-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Chuang C-H, Hsieh W-S, Guo YL, et al. Chinese Herbal medicines used in pregnancy: a population-based survey in Taiwan. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2007;16:464–8. 10.1002/pds.1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Facchinetti F, Pedrielli G, Benoni G, et al. Herbal supplements in pregnancy: unexpected results from a multicentre study. Hum Reprod 2012;27:3161–7. 10.1093/humrep/des303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Moussally K, Bérard A. Exposure to specific Herbal products during pregnancy and the risk of low birth weight. Alternative Therapies in Health & Medicine 2012;18. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Frawley J, Adams J, Sibbritt D, et al. Prevalence and determinants of complementary and alternative medicine use during pregnancy: results from a nationally representative sample of Australian pregnant women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2013;53:347–52. 10.1111/ajo.12056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Budzynska K, Filippelli AC, Sadikova E, et al. Use and factors associated with Herbal/botanical and Nonvitamin/Nonmineral dietary supplements among women of reproductive age: an analysis of the infant feeding practices study II. J Midwifery Womens Health 2016;61:419–26. 10.1111/jmwh.12482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Tang L, Lee AH, Binns CW, et al. Consumption of Chinese Herbal medicines during pregnancy and postpartum: a prospective cohort study in China. Midwifery 2016;34:205–10. 10.1016/j.midw.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Illamola SM, Amaeze OU, Krepkova LV, et al. Use of herbal medicine by pregnant women: what physicians need to know. Front Pharmacol 2019;10:1483. 10.3389/fphar.2019.01483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Peprah P, Agyemang-Duah W, Arthur-Holmes F, et al. We are nothing without herbs’: a story of herbal remedies use during pregnancy in rural Ghana. BMC Complement Altern Med 2019;19:65. 10.1186/s12906-019-2476-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Wardani RS, Schellack N, Govender T, et al. Treatment of the common cold with herbs used in Ayurveda and Jamu: monograph review and the science of ginger, Liquorice, Turmeric and Peppermint. Drugs Context 2023;12:2023-2-12. 10.7573/dic.2023-2-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]