Abstract

The Fer protein belongs to the fes/fps family of nontransmembrane receptor tyrosine kinases. Lack of success in attempts to establish a permanent cell line overexpressing it at significant levels suggested a strong negative selection against too much Fer protein and pointed to a critical cellular function for Fer. Using a tetracycline-regulatable expression system, overexpression of Fer in embryonic fibroblasts was shown to evoke a massive rounding up, and the subsequent detachment of the cells from the substratum, which eventually led to cell death. Induction of Fer expression coincided with increased complex formation between Fer and the cadherin/src-associated substrate p120cas and elevated tyrosine phosphorylation of p120cas. β-Catenin also exhibited clearly increased phosphotyrosine levels, and Fer and β-catenin were found to be in complex. Significantly, although the levels of α-catenin, β-catenin, and E-cadherin were unaffected by Fer overexpression, decreased amounts of α-catenin and β-catenin were coimmunoprecipitated with E-cadherin, demonstrating a dissolution of adherens junction complexes. A concomitant decrease in levels of phosphotyrosine in the focal adhesion-associated protein p130 was also observed. Together, these results provide a mechanism for explaining the phenotype of cells overexpressing Fer and indicate that the Fer tyrosine kinase has a function in the regulation of cell-cell adhesion.

The Fer protein is a 94-kDa nonreceptor tyrosine kinase, of which the overall structure and primary sequence are most closely related to that of the fes/fps proto-oncoprotein. Fer and fes/fps share 70% identity in their tyrosine kinase domains (18, 38). The amino terminus of Fer is relatively large but does not contain previously identified common protein binding domains. However, this region does have the ability to form coiled-coil structures and mediates oligomerization of Fer in vitro (24). There is a single SH2 domain, which is located between the N-terminal oligomerization and the C-terminal tyrosine kinase domains.

The normal cellular function of Fer is unknown. The finding that it is ubiquitously expressed, albeit more abundantly in cells of fibroblastic and epithelial origin than in hematopoietic cell types, suggests it has a commonly required function in signal transduction (9, 15, 18, 29). Such function is supported by the finding that Fer is well-conserved in evolution, and recently, the Drosophila melanogaster equivalent of Fer, Dfer, was described (37). Involvement of Fer in cell cycle events is supported by the existence of a truncated protein, FerT, which is exclusively expressed at the pachytene stage of meiotic prophase during spermatogenesis (11, 23). In addition, Fer is found both in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fraction of cultured cells (17).

Signalling through the epidermal growth factor (EGF) or platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor results in tyrosine phosphorylation of Fer and of a protein called p120cas (24). Cas was initially identified as a substrate of the activated v-src kinase and becomes prominently tyrosine phosphorylated in v-src-transformed cells (41) but also in response to induced signalling by the PDGF, EGF, and colony-stimulating factor-1 receptors (8, 22). Subsequently, Cas was found to have structural similarity to β-catenin and plakoglobin/γ-catenin, components of cadherin/catenin cell-cell adherens junctions, and was found to be linked to such complexes (7, 42, 43, 48).

Our previous experiments have focused on developing expression systems in which Fer activity and signalling could be examined in more detail. However, repeated attempts to overexpress this protein from commonly used promoters (e.g., mouse mammary tumor virus, simian virus 40, and metallothionein promoters) in fibroblasts failed to yield cell lines with substantial overexpression. We concluded that expression of Fer above a certain threshold is lethal to cells in culture. To circumvent this problem, Fer was expressed in cells from a tetracycline-regulatable promoter. In the present study we have used these stably transfected cells to show that overexpression of Fer leads to the rounding up of cells and subsequently to detachment of cells from the substratum, and we correlate this with alterations in the composition of cell adherens junction protein complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of a tetracycline-responsive FER construct and transfection.

The human FER cDNA (18) was subcloned into a tetracycline-controllable expression system (14) as follows. A 5′ BamHI site was generated via PCR with a 5′ primer consisting of a BamHI recognition sequence followed by 21 nucleotides homologous to the FER coding region from the first ATG and a reverse primer 155 bp downstream of it. The PCR fragment was digested with BamHI-NsiI. The resulting 135-bp 5′ FER fragment was ligated with a 1.2-kb NsiI-KpnI FER fragment into BamHI-KpnI-digested pSK. A 5′ BamHI-KpnI fragment was isolated from this plasmid. A 1.3-kb KpnI-XhoI 3′ fragment from the FER cDNA was ligated into pSK digested with KpnI-XhoI, and a 1.3-kb KpnI-XbaI 3′ fragment was isolated from this. The 1.3-kb BamHI-KpnI 5′ FER fragment and the 1.3-kb KpnI-XbaI 3′ FER fragment were ligated into BamHI-XbaI-digested pUHG10-3 (derived from pUHD10-3 [40]), resulting in pUHG10-3-FER. In this construct, FER is driven by the minimal human cytomegalovirus promoter, preceded by tetO sequences. Simultaneously, a Rat-2 fibroblast cell line expressing the tetracycline-sensitive, tetO-binding transactivator (tTA) was established by cotransfection of the tTA expression plasmid pUHD15-1, in which tTA is produced from a cytomegalovirus promoter, and the neomycin-resistance plasmid pSV2neo. There were no visible phenotypic consequences or toxic effects of tTA expression on these cells. Rat-2 fibroblasts are of embryonic origin. To the best of our knowledge, expression of different cadherins has not been investigated in this cell line. A tTA-expressing clone was selected and stably cotransfected with pUHG10-3-FER and pGKHyg. This resulted in a clonal cell line (tet-Fer) in which transactivation of the FER construct can be repressed by addition of tetracycline. Cells were maintained in high-glucose (4.5 g/liter) Dulbecco’s modified essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U of penicillin/ml, 100 μg of streptomycin/ml, 400 μg of G418/ml, 200 μg of hygromycin B/ml, and 1 μg of tetracycline/ml and kept at 37°C and 7.5% CO2.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis.

Cellular extracts were prepared as described previously (51). In brief, cells (floating plus attached) were lysed in Triton lysis buffer (25mM Na-phosphate [pH 7.5], 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM NaF, 10 μg each of aprotinin and leupeptin/ml, 1 μM pepstatin A, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 25 μM phenylarsine oxide). Per immunoprecipitate, 0.5 to 1 mg of lysate proteins was used. Lysates were incubated with antibodies and washed four times with lysis buffer without inhibitors. Proteins were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Western blots were incubated with antibodies as previously described (51) and visualized with ECL (Amersham Corp.). The Fer polyclonal rabbit antiserum CH-6 has been previously described (17) and was further purified by using an immunoaffinity column. Monoclonal antibodies against E-cadherin, α-catenin, β-catenin, p120cas (Src substrate), p130cas (Crk-associated substrate), FAK, and phosphotyrosine (RC-20) were from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, Ky.). β-Catenin polyclonal antiserum from Santa Cruz Biotech was used for the β-catenin immunoprecipitation and Fer Western blot analyses (Fig. 8). The E-cadherin antiserum is directed against residues 735 to 883 of E-cadherin and the manufacturer states it does not cross-react with N-cadherin.

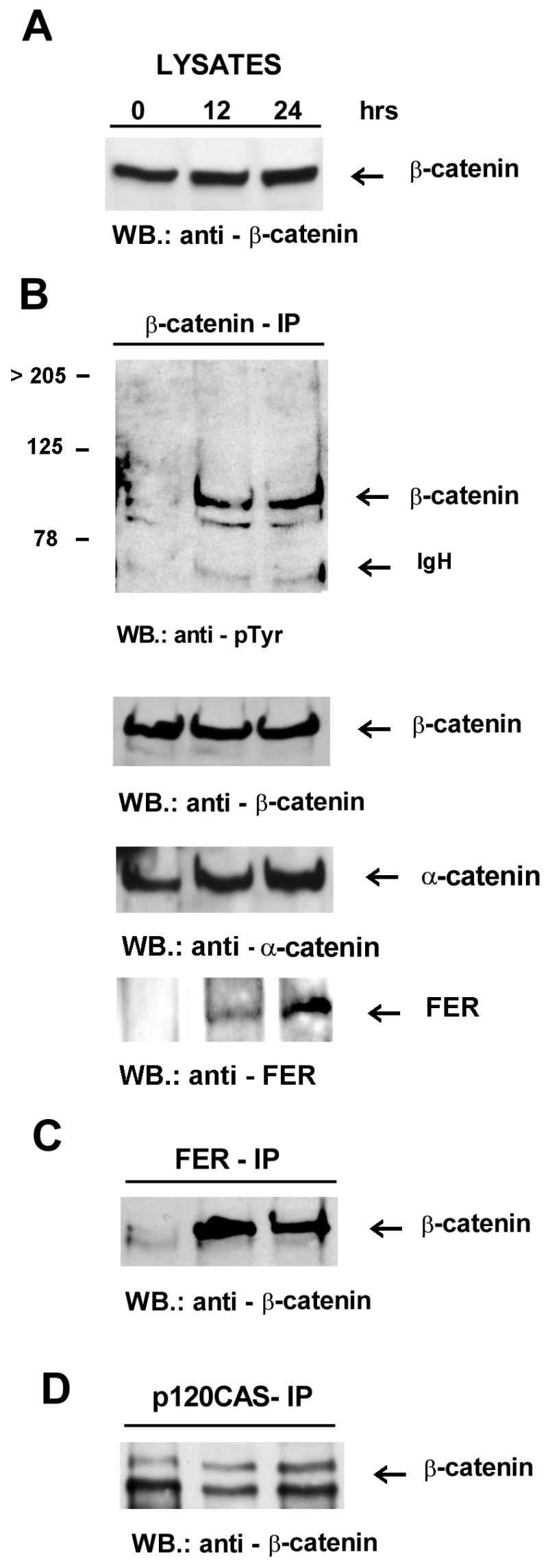

FIG. 8.

β-catenin coimmunoprecipitates with Fer and becomes tyrosine phosphorylated upon induction of Fer expression. Lysates (A) and β-catenin (B), Fer (C), and p120cas (D) immunoprecipitates were prepared at 0, 12, and 24 h after withdrawal of tetracycline. Antibodies used for immunoprecipitation (IP) and Western blotting (WB) are indicated above and below each panel, respectively. The locations of β-catenin, α-catenin, and Fer are indicated. Note that the extra lower-molecular-weight species which reacts with the β-catenin antibodies and is seen in some of the extracts (but not lysates, which are processed more rapidly) most likely represents partial proteolytic degradation products of β-catenin as indicated in reference 21. IgH, immunoglobulin heavy chain.

Analysis of DNA: flowcytometry and DNA laddering.

For fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis 106 cells from nonconfluent cultures were either collected from the medium (as floating cells) or trypsinized (attached cells) and washed twice in Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline lacking Mg2+ and Ca2+, resuspended in 1 ml of permeabilization buffer (Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline-Mg2+-Ca2+, 0.1% Na3-citrate, 0.1% Triton X-100) with RNase (40 μg/ml), and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Propidium iodide (final concentration, 25 μg/ml) was added and cells were stained for 15 to 30 min in the dark at room temperature.

Attached and floating cells at time 0 and after 1.5 days of Fer overexpression were harvested and used for high-molecular-weight extraction. DNA was analyzed for laddering by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel and ethidium bromide staining.

All figures were generated with a Compaq Deskpro Pentium 133 32 Ms RAM computer and an HP ScanJet 4C printer. The software program used was Corel Photopaint 7.

RESULTS

Overexpression of Fer induces rounding up and subsequently leads to detachment of cells.

To generate a cell line with regulatable Fer overexpression, a tTA expressing cell line was first established in which the expression of a reporter gene could be tightly controlled by tetracycline. Then this cell line was supertransfected with the Fer reporter construct, resulting in the generation of tet-Fer.

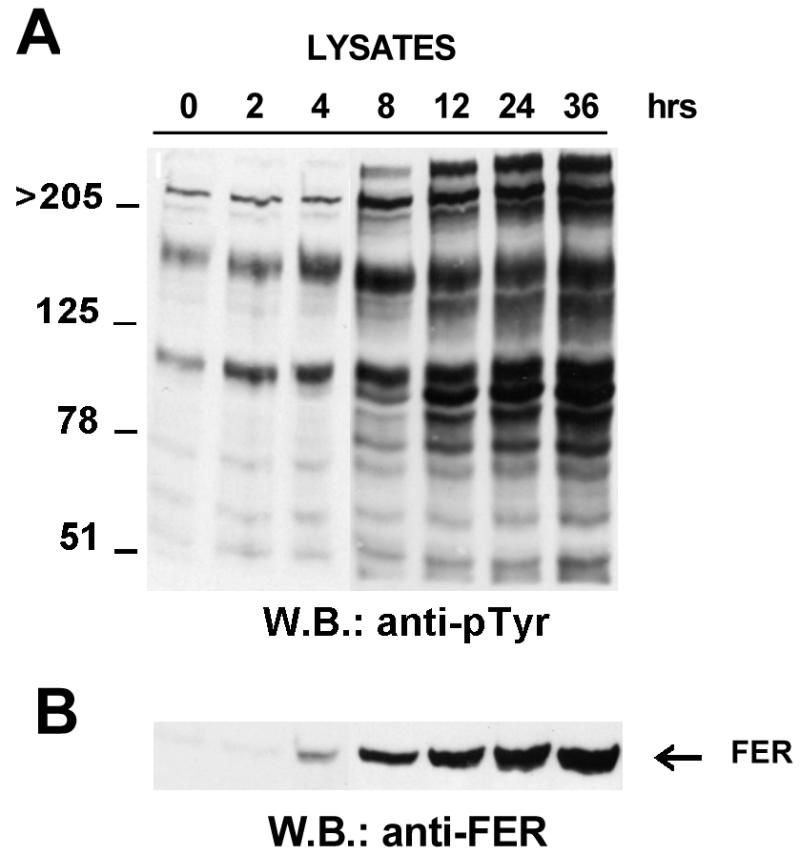

Tet-Fer cells were cultured in the absence of tetracycline, and whole-cell lysates were prepared at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 36 h after withdrawal of tetracycline. Starting 2 h after tetracycline withdrawal, a gradual increase in Fer expression was observed (Fig. 1B). Concomitantly, the tyrosine phosphorylation levels of several distinct cellular proteins including the 94-kDa Fer protein were also increased (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Time course of Fer overexpression. Lysates were prepared from cells cultured in the absence of tetracycline (Fer-overexpressing cells) for the indicated times. Each lane contains 20 μg of total cell protein. The filters were blotted with the RC-20 anti-pTyr monoclonal antibody (A) or anti-Fer antisera (B). The location of the 94-kDa Fer kinase is indicated in panel B. WB, Western blot.

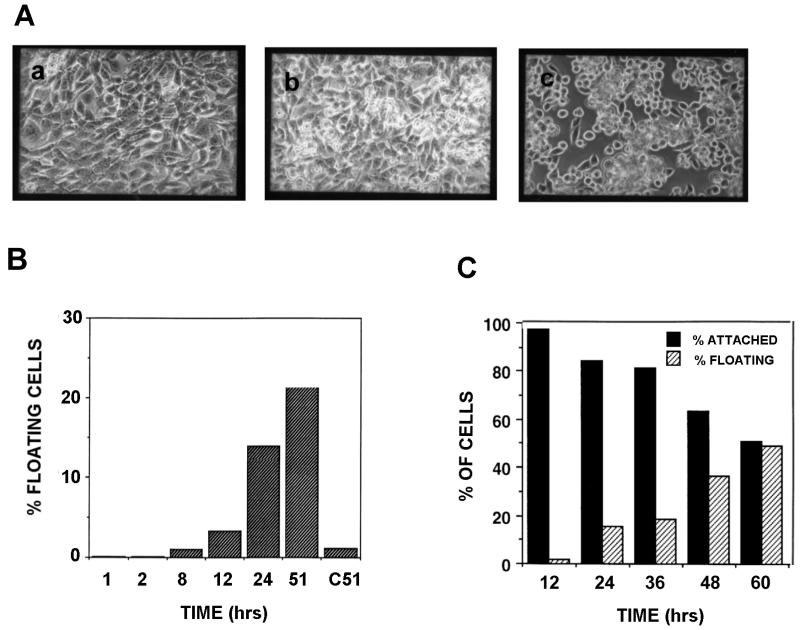

In the presence of tetracycline (i.e., repressed Fer expression), the transfected fibroblasts presented normal growth and morphology (Fig. 2A, panel a). After withdrawal of tetracycline, cells progressively showed a rounded morphology (Fig. 2A, panels b and c) and subsequently detached from the monolayer. To quantitate detachment, attached and floating cells cultured in the absence of tetracycline were collected at different times and counted. A culture of cells continuously grown in the presence of tetracycline served as a control. As shown in Fig. 2B, the number of floating cells increased progressively over time, with around 20% of the total number of cells floating at 48 h. Floating cells increased in number and after 6 days of culture in the absence of tetracycline over 99% of the cells had detached. This finding is concordant with our earlier observation that Fer overexpression leads to cell death.

FIG. 2.

Time course of Fer overexpression-induced detachment and reattachment. (A) tet-Fer cells were cultured in the presence (a, Fer expression repressed) or absence (b and c, 15 and 34 h, respectively, after tetracycline withdrawal) of tetracycline, and cell morphology and detachment were evaluated microscopically. (B) Floating cells were collected at different time points as indicated and counted. The bars represent the percentages of floating cells in the total number of cells (attached plus floating cells) at each time point. The control at t = 51 h represents cells grown in the continuous presence of tetracycline. (C) Reattachment of floating cells. Cells which had been floating for the indicated amount of time after tetracycline withdrawal were reincubated with tetracycline-containing medium to repress Fer expression. The percentage of cells from each time point which either re-attached or remained floating is indicated after 24 h in medium with tetracycline. The data shown are representative of two independently performed experiments.

Floating cells can reattach but show increased apoptosis after a prolonged state of disattachment.

To investigate whether these floating cells were irreversibly committed (i.e., apoptotic) floaters were collected after having been in suspension for 12 to 60 h. Cells were then returned to medium containing tetracycline, which represses the Fer expression, and the percentage of cells which reattached was determined after 24 h. As shown in Fig. 2C, the percentage of cells being able to reattach was a function of time: the longer the cells had been floating, the smaller the percentage of cells which were able to reattach. However, the vast majority of cells which had been floating for 12 to 24 h were able to reattach, indicating these cells were not committed to apoptosis.

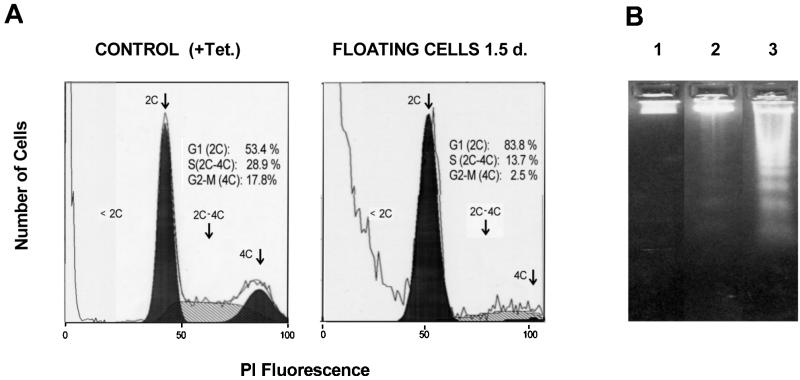

To investigate the floating population, flow cytometric analysis of cells after 36 h of Fer overexpression was performed. This showed that the viability of the Fer-overexpressing cells was reduced to varying extents in different experiments compared with that of cells which were repressed. As shown in Fig. 3A, the detached population of Fer-overexpressing cells showed apoptosis (cells with DNA < 2C). The population of viable cells was primarily composed of cells residing in G1 phase (2C), with a drastic reduction in the number of cells in S phase (2C-4C) (around 50% of the control) and G2-M phase (4C). When Fer-overexpressing cells were separated in detached and attached cells and the DNA of these populations was analyzed by gel electrophoresis, those that had been floating for 36 h displayed DNA fragmentation (Fig. 3B, lane 3). The cells that remained attached showed very little DNA fragmentation (Fig. 3B, lane 2).

FIG. 3.

Cell cycle analysis of cells after Fer induction. (A) Flow cytometry. DNA content of control cells lacking Fer induction was compared to DNA content of floating cells after 1.5 days of Fer overexpression. Black areas denote G0/G1 (left peak, 2C DNA) or G2/M (right peak, 4C DNA) populations. The hatched area in between represents the population of cells in S phase (2C-4C DNA). The percentage of cells in each phase was calculated by including only live cells (population of cells with less than 2C DNA was excluded). PI, propidium iodide. (B) DNA laddering. DNAs were isolated from the same cultures depicted in panel A, 1.5 days after tetracycline withdrawal, and run on a 1.5% agarose gel. Each lane contains 10 μg of DNA. Lane 1, cells grown in the presence of tetracycline; lane 2, Fer-overexpressing attached cells; lane 3, Fer-overexpressing floating cells.

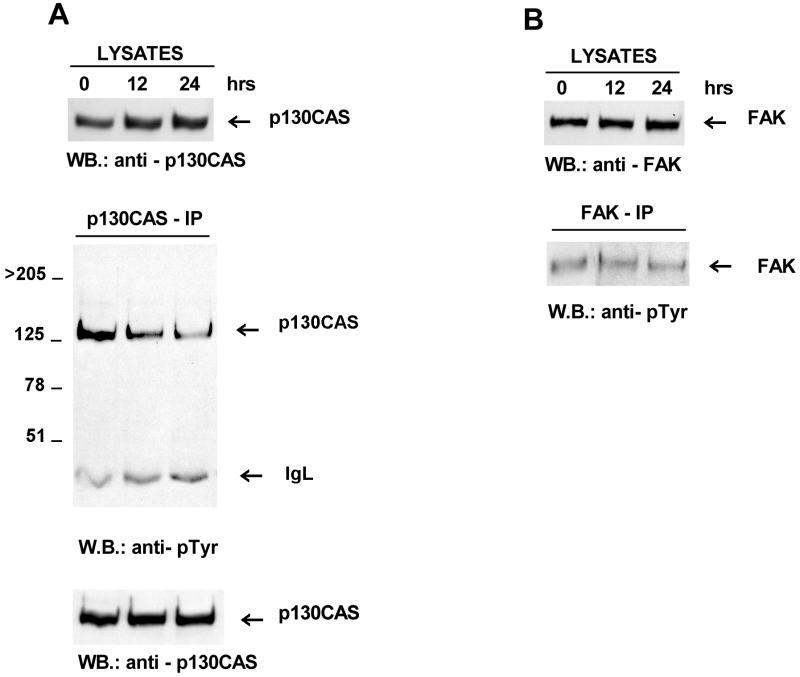

The Crk-associated substrate p130 becomes hypophosphorylated with Fer overexpression.

The rounding up and subsequent detachment of cells following induction of Fer indicated a perturbation of cell-cell and/or cell-substratum adhesion. A more detailed analysis of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins affected by Fer overexpression (results not shown) indicated hypophosphorylation of a 130-kDa phosphoprotein concomitant with the increased Fer levels. The detachment of the Fer-overexpressing cells from the substratum suggested that the integrin-associated focal contacts could be affected in these cells. Therefore, we examined tyrosine phosphorylation of the focal adhesion tyrosine kinase FAK and the Crk-associated substrate p130. Both proteins localize to focal adhesions and are tyrosine phosphorylated in cells in response to integrin-mediated adhesion (5, 6, 35, 39, 52).

Neither FAK nor p130 expression levels were altered by Fer overexpression (Fig. 4). Immunoprecipitation of FAK followed by Western blotting with a phosphotyrosine-specific antibody showed that its level of tyrosine phosphorylation was unaltered (Fig. 4B). In contrast, p130 was almost completely dephosphorylated after 24 h of Fer overexpression (Fig. 4A). This result links hypophosphorylation of p130 with the decreased attachment seen in Fer-overexpressing cells.

FIG. 4.

Decreased tyrosine phosphorylation of the Crk-associated substrate p130 but not of the focal adhesion kinase Fak in Fer-overexpressing cells. This figure is representative of three independently performed experiments. Total lysates or immunoprecipitates were blotted with anti-p130 monoclonal antibodies (A) or anti-FAK monoclonal antibodies (B). as indicated below each panel. The locations of p130 and p125FAK are indicated. IgL, immunoglobulin light chain. WB, Western blot.

Fer overexpression induces p120cas phosphorylation.

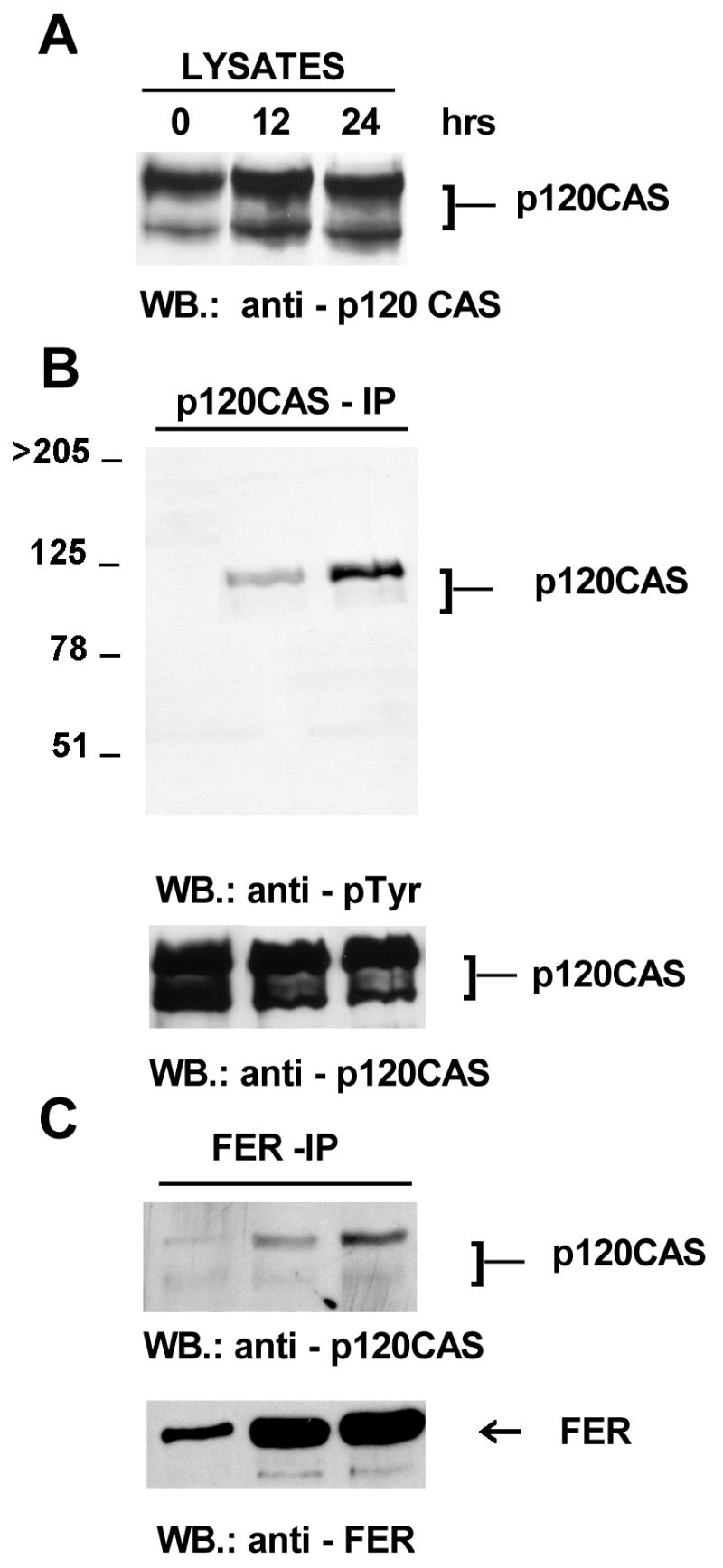

Previously, a constitutive association of Fer has been reported with p120cas (24). This protein was originally identified as a substrate for the activated v-src kinase and was subsequently shown to be a member of the catenin family because it contains armadillo repeats. Members of this family mediate cell-cell contacts by linking the transmembrane cadherins to the cytoskeleton (reviewed in references 13 and 32). To investigate p120cas complex formation, tet-FER whole-cell lysates at 0, 12, and 24 h of Fer overexpression were immunoprecipitated with a p120cas monoclonal antibody. In agreement with previously published data obtained with NIH 3T3 fibroblasts (33), the 1A, 1B, 2A, and 2B isoforms of Cas were all expressed in Rat-2 fibroblasts, with the 1A and 1B forms, which comigrate here, being the most abundant (shown as the most slowly migrating band in Fig. 5A). In contrast to the effect of transformation by v-src, which alters the ratio of the different isoforms (33), overexpression of Fer did not affect either the ratio of the isoforms or total expression levels of p120cas (Fig. 5A). When the Cas immunoprecipitates were blotted with an antiphosphotyrosine antibody, phosphorylated Cas was found present at 12 and 24 h (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, the Cas 1A and 1B isoforms (upper of the two bands) were most prominently phosphorylated, whereas bands corresponding to the 2A and 2B isoforms (lower of the two bands) showed very little, if any, tyrosine phosphorylation. An increased amount of Cas coimmunoprecipitated with Fer and correlated with the elevated expression of the Fer protein over time (Fig. 5C). Since Cas is found in complex with E-cadherin at adherens junctions, which also contain α-catenin complexed to either β-catenin or plakoglobin, it was of interest to examine the effects of the composition of the adherens junctions upon Fer induction.

FIG. 5.

Association of p120cas with Fer. Lysates were prepared at 0, 12, and 24 h after withdrawal of tetracycline, which induces Fer expression. Total lysates or immunoprecipitates were blotted with anti-Cas monoclonal (A), anti-pTyr monoclonal (B), or anti-Fer polyclonal (C) antibodies as indicated below the panels. The locations of p120cas and p94Fer (FER) are indicated. WB, Western blot.

Fer overexpression modifies the composition of the E-cadherin–catenin complexes.

Cadherins constitute the extracellular part of the adherens junctions, and their function is regulated intracellularly through an indirect association with the cytoskeleton. Cadherins bind to either β-catenin or plakoglobin. These in turn are linked to α-catenin, which has an actin-binding domain (reviewed in references 1, 30, and 32). There is increasing evidence that β-catenin acts as a regulatory component of the complex (13).

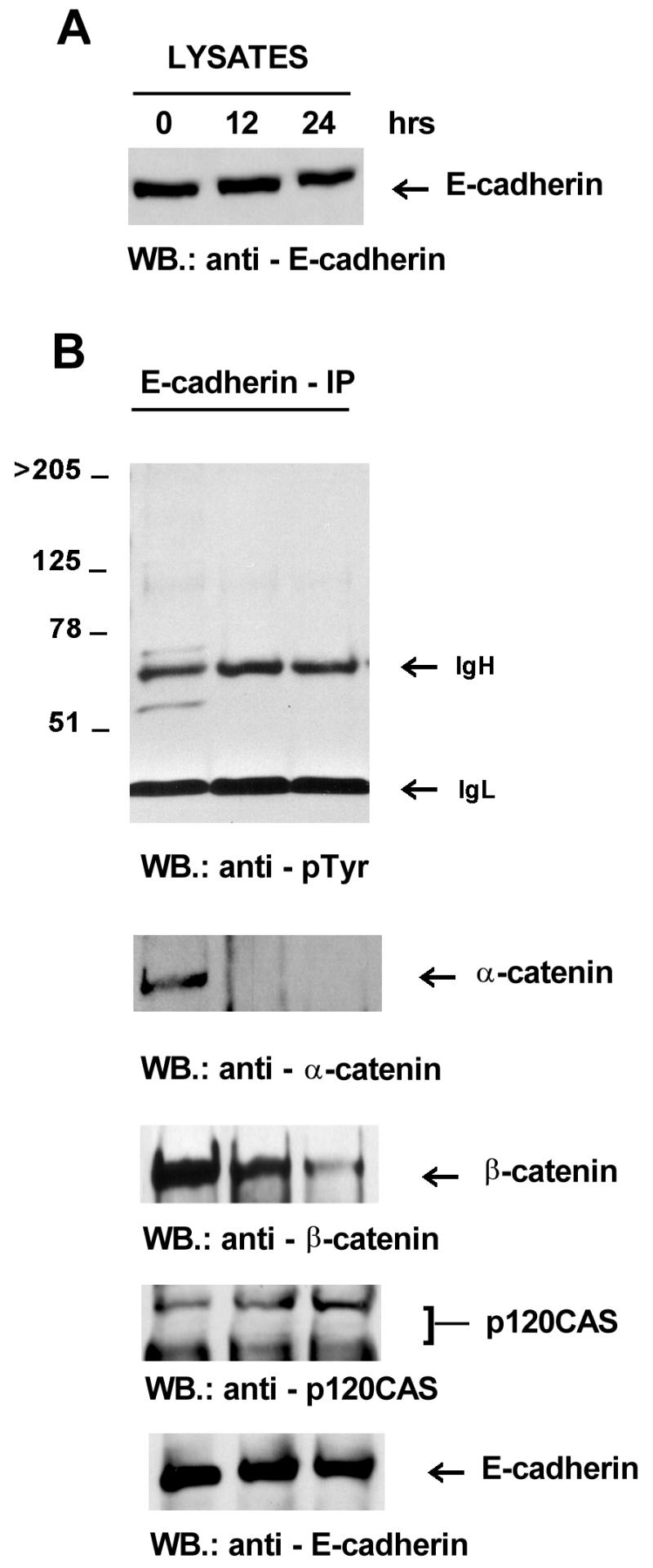

To determine if Fer overexpression modifies the composition of this multiprotein complex, lysates were prepared and immunoprecipitated with anti-E-cadherin monoclonal antibodies, and the composition of the E-cadherin–catenin complexes was analyzed. Expression levels of E-cadherin were not affected by Fer expression (Fig. 6A) nor was E-cadherin detectably phosphorylated on tyrosine (Fig. 6B). However, complex formation with E-cadherin was dramatically affected. The association of E-cadherin with α-catenin was progressively disrupted. Indeed, α-catenin disappeared almost completely from the E-cadherin complex when Fer expression was induced (Fig. 6B). Similar results were obtained when the cells were at 50% confluency (not shown). In contrast, levels of p120cas in the E-cadherin immunoprecipitates were essentially unaffected (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Induction of Fer expression modifies the composition of the E-cadherin–catenin complex. Cells were at confluency. Antibodies used for immunoprecipitation (IP) or Western blotting (WB) of whole-cell lysates (A) and E-cadherin immunoprecipitates (B) are indicated. IgH, immunoglobulin heavy chain; IgL, immunoglobulin light chain.

α-Catenin binds to E-cadherin via β-catenin. Therefore, it was possible that α-catenin dissociated alone. Alternatively, it was possible that the link between β-catenin and E-cadherin was also disrupted. Western blotting of the E-cadherin immunoprecipitates indicated that also β-catenin was progressively lost from the complex (Fig. 6B).

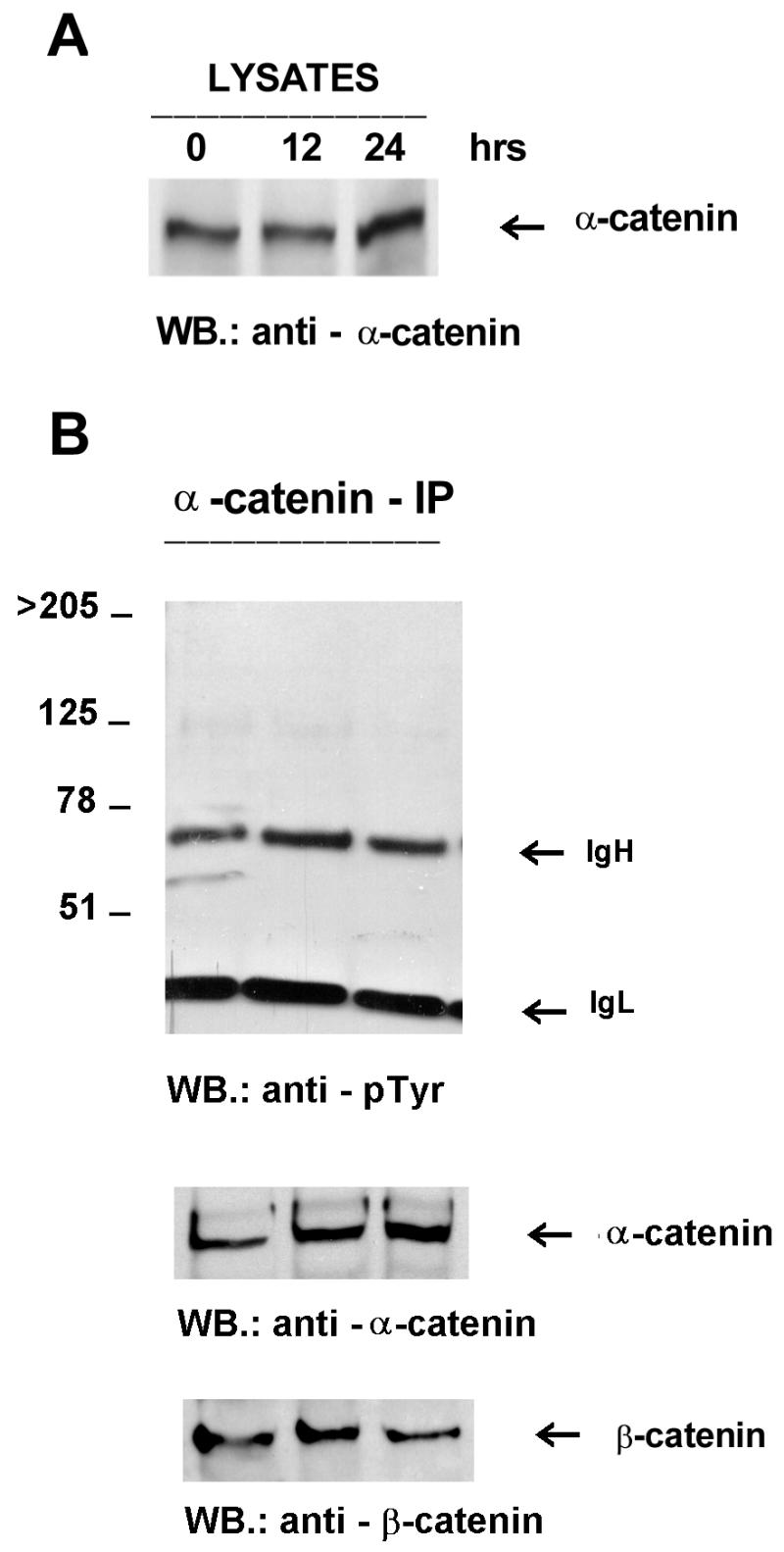

A possible change in α-catenin–β-catenin interaction or expression levels was also investigated. However, expression levels of neither β-catenin (Fig. 8A) nor α-catenin (Fig. 7A) were affected by Fer expression levels. In addition, α-catenin did not become tyrosine phosphorylated (Fig. 7B) nor could it be detected in Fer immunoprecipitates (not shown). The amount of β-catenin recovered in α-catenin immunoprecipitations remained essentially the same in the samples (Fig. 7B), and conversely, there was little variation in the amount of α-catenin recovered in β-catenin immunoprecipitates (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 7.

α-Catenin is unaffected by Fer overexpression. Lysates (A) and immunoprecipitates (B) were prepared as described in the legend to Fig. 4 and immunoprecipitated with anti-α-catenin monoclonal antibodies. Antibodies used for Western blotting (WB.) are indicated below the panels. The location of the 102-kDa α-catenin protein is indicated. IgH, immunoglobulin heavy chain; IgL, immunoglobulin light chain.

Altered tyrosine phosphorylation of β-catenin often coincides with the disassembly of adherens junctions and diminished cell adhesion (2, 3, 16, 31, 46). To examine the effect of Fer induction on β-catenin, lysates were immunoprecipitated with β-catenin antibodies and the level of tyrosine phosphorylation of β-catenin was analyzed. As shown in Fig. 8B, the degree of tyrosine phosphorylation on β-catenin at 12 or 24 h of Fer overexpression was clearly elevated. Interestingly, Fer was present in the β-catenin immunoprecipitate (Fig. 8B), and conversely, immunoprecipitation with Fer antibodies showed the presence of β-catenin (Fig. 8C). The amount of p120cas found in the complex together with β-catenin was not clearly affected by Fer overexpression (Fig. 8D).

DISCUSSION

We attempted numerous times to overexpress Fer in cultured cells by using different systems. These efforts were unsuccessful, suggesting a potent negative selection against cells expressing the protein at high levels. The results presented here, obtained by using a system in which Fer expression can be tightly regulated, provide an explanation for this phenomenon.

When Fer overexpression is induced, major morphological changes in the culture are observed, manifested by rounding up and subsequent detachment of cells. Flow cytometric studies of these floating cells after 36 h revealed a reduction in the number of viable cells and an increase in the number of cells dying by apoptosis, as confirmed by DNA laddering.

We suggest that the diminished viability of these floating cells is not a direct consequence of Fer expression but rather is caused by the inability to attach in the presence of overexpressed Fer. It is well-established that normal (e.g., nontransformed) cells which inappropriately lack cell-cell or cell-matrix contact have decreased viability (45). The increase in apoptotic death observed in the Fer-overexpressing floating cells therefore most probably represents an appropriate response to the anoikis state of these cells. This suggestion is supported by the experiments which demonstrate that cells which had not been floating for extended periods of time could be induced to reattach once Fer expression had been repressed by reintroduction of tetracycline into the medium.

By what mechanism does Fer expression induce these morphological changes? It is likely to be different from that responsible for similar morphological changes associated with expression of the oncogene v-src: in cells expressing v-src tyrosine phosphorylation of the focal adhesion protein pp125Fak is initially increased, followed by pp125Fak degradation (10). In contrast, in our Fer expression system, neither the expression level nor the tyrosine phosphorylation of pp125Fak was changed, although dephosphorylation of the focal adhesion-associated protein p130cas was observed, which could have contributed to a weakening of the cell-matrix interactions. Other reports have demonstrated dephosphorylation of p130 in association with disruption of cell-substratum adhesion (35, 52). Since the dephosphorylation of p130 was already observed at 12 h of Fer induction, when virtually all cells were still attached to the plate, this suggests that dephosphorylation of p130 may precede the actual detachment and may contribute to this event. In addition, cross-talk between the integrin-based cell-matrix and the cadherin-based cell-cell adherens systems has recently been reported (21, 34), suggesting that the biochemical effects of Fer on the cadherin system may also indirectly affect adhesion via integrins.

The finding that Fer is associated with p120cas (24) provided a starting point to examine cadherin-associated changes in more detail, since Cas is associated with proteins found in adherens junctions. An increasing amount of p120cas was found in complex with Fer as the level of Fer protein progressively increased. Also, the amount of tyrosine-phosphorylated p120cas was increased. However, it seems unlikely that this association was induced by the tyrosine phosphorylation of Cas, since Kim and Wong (24) showed that these two proteins constitutively bind to each other via the Fer N-terminal domain. Although Fer appeared to bind the 1A, 1B, 2A, and 2B isoforms of Cas, only the 1A and 1B isoforms clearly became tyrosine phosphorylated. This would suggest that the 2A and 2B isoforms lack tyrosine residues which can be phosphorylated by the Fer kinase. Cas2A and 2B differ from 1A and 1B in that it lacks a relatively small N-terminal segment, which contains two tyrosine residues (33). However, if the substrate specificity of Fer resembles that of the related Fes (47), these tyrosine residues would not be in the appropriate context for efficient phosphorylation. Currently, the biochemical significance of the observed phosphorylation of p120cas isoforms by Fer remains unclear, since it did not appear to alter their binding to the E-cadherin complex. Because p120cas binds to a site on E-cadherin distinct from that of β-catenin, binding of these two proteins to E-cadherin may be independently regulated and have a different significance.

It is of interest that the tyrosine kinase Fer also clearly formed a complex with a protein structurally related to p120cas, β-catenin, which also became phosphorylated on tyrosine. In contrast to p120cas, however, increased tyrosine phosphorylation of β-catenin was accompanied by a decrease in the amount of β-catenin found in association with E-cadherin. Tyrosine phosphorylation of β-catenin concurrent with dysfunction of cadherin-mediated adherence has also been demonstrated in growth factor-stimulated cancer cells (12, 19, 46) and in cells transformed by v-src (3, 16, 31, 50) or by ras (25). But the exact correlation between tyrosine phosphorylation of cadherins and catenins in v-src-transformed cells and the weakened adherence of those cells is unclear, since the amount of α-catenin complexed to E-cadherin after v-src transformation is unaltered (36).

It appears that α-catenin is the key component of the complex, since it provides the anchorage to the cytoskeleton and forms the direct link between either cadherin–β-catenin or cadherin-plakoglobin (γ-catenin) complexes to F-actin (28, 44). In contrast to the v-src transformants, induction of Fer expression did lead to a clear disappearance of α-catenin from the E-cadherin complexes, most probably resulting in loss of anchorage of the cadherin complex to F-actin. Since the level of α-catenin bound to β-catenin remained essentially unchanged, α-catenin and β-catenin apparently left the complex together. Regardless of the exact mechanism, however, these biochemical findings provide an explanation for the observed rounding up to Fer-overexpressing cells.

What could the normal cellular role of Fer be? Our present data demonstrate that activity of the tyrosine kinase Fer can regulate the stability of adherens junction complexes. Since we could immunoprecipitate α-catenin with E-cadherin antibodies our methods are capable of detecting complex formation between indirectly bound proteins. However, a direct incorporation of Fer into the E-cadherin–β-catenin–α-catenin complex could not be demonstrated (results not shown). This suggests the existence of a distinct complex including Fer and β-catenin. It has been shown that Fer is constitutively bound to the EGF receptor (EGF-R) and becomes activated upon stimulation of cells with EGF (24). Signalling through the EGF-R can cause the tyrosine phosphorylation of β-catenin (19, 46), and β-catenin has been shown to associate with the EGF-R in epithelial cells under conditions of active growth (49). These data combined suggest that a signalling complex may exist, consisting of the EGF-R, Fer, and β-catenin and that this complex may be responsible for tyrosine phosphorylation of β-catenin observed in some systems. Previously, we have demonstrated that the Fer protein is present both in the cytoplasmic and the nuclear fractions of synchronized cultured fibroblasts (17) and as such may transmit signals regarding the state of cell-cell adhesion to the nucleus. Therefore, we speculate that this protein complex plays a role in the regulation of density-dependent growth.

The modulation of cell adhesion via cadherin-catenin interactions is important for a wide variety of cell types including stationary cells in the context of a tissue as well as migrating cells in development and in tumor metastasis (4, 26, 27). Therefore, it will be of obvious interest to elucidate the regulatory role of Fer in mediating cell-cell contact both in development and in cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Roberto Rosato and Jacqueline M. Veltmaat contributed equally to this work.

The initial stages of this work were supported by Public Health Service grant CA47456 from the National Cancer Institute.

We thank R. Hooft van Huijsduijnen for pUHD10-3, pUHG10-3-CAT, and pUHG15-1; Jeroen Bakker for immunopurification of Fer CH-6 antisera; and Ron de Jong for help with immunodetection experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aberle H, Schwartz H, Kemler R. Cadherin-catenin complex: protein interactions and their implications for cadherin function. J Cell Biochem. 1996;61:514–523. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19960616)61:4%3C514::AID-JCB4%3E3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balsamo J, Leung T, Ernst H, Zanin M K, Hoffman S, Lilien J. Regulated binding of PTP1B-like phosphatase to N-cadherin: control of cadherin-mediated adhesion by dephosphorylation of β-catenin. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:801–813. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.3.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behrens J, Vakaet L, Friis R, Winterhager E, Van Roy F, Mareel M M, Birchmeier W. Loss of epithelial differentiation and gain of invasiveness correlates with tyrosine phosphorylation of the E-cadherin/β-catenin complex in cells transformed with a temperature-sensitive v-src gene. J Cell Biol. 1993;120:757–766. doi: 10.1083/jcb.120.3.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birchmeier, W., K. M. Weidner, and J. Behrens. 1993. Molecular mechanisms leading to loss of differentiation and gain of invasiveness in epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 17(Suppl.):159–164. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Burridge K, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M. Focal adhesions, contractility, and signaling. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:463–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burridge K, Turner C E, Romer L H. Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin and pp125FAK accompanies cell adhesion to extracellular matrix: a role in cytoskeletal assembly. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:893–903. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels J M, Reynolds A B. The tyrosine kinase substrate p120cas binds directly to E-cadherin but not to the adenomatous polyposis coli protein or α-catenin. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4819–4824. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Downing J R, Reynolds A B. PDGF, CSF-1, and EGF induce tyrosine phosphorylation of p120, a pp60src transformation-associated substrate. Oncogene. 1991;6:607–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman R A, Gabrilove J L, Tam J P, Moore A S, Hanafusa H. Specific expression of the human cellular fps/fes encoded protein NCP92 in normal and leukemic myeloid cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:2379–2383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.8.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fincham V J, Frame M C. The catalytic activity of Src is dispensable for translocation to focal adhesions but controls the turnover of these structures during cell motility. EMBO J. 1998;17:81–92. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischman K, Edman J C, Shackleford G M, Turner J A, Rutter W J, Nir U. A murine fer testis-specific transcript (ferT) encodes a truncated Fer protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:146–153. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.1.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujii K, Furukawa F, Matsuyoshi N. Ligand activation of overexpressed epidermal growth factor receptor results in colony dissociation and disturbed E-cadherin function in HSC-1 human cutaneous squamous carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 1996;223:50–62. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gumbiner B M. Cell adhesion: the molecular basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell. 1996;84:345–357. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gossan M, Bujard H. Tight control of gene expression in mammalian cells by tetracycline-responsive promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5547–5551. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halachmy S, Bern O, Schreiber L, Carmel M, Sharabi Y, Shoham J, Nir U. p94fer facilitates cellular recovery of gamma irradiated pre-T cells. Oncogene. 1996;14:2871–2880. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamaguchi M, Matsuyoshi N, Ohnishi Y, Gotoh B, Takeichi M, Nagai Y. p60v-src causes tyrosine phosphorylation and inactivation of the N-cadherin-catenin cell adhesion system. EMBO J. 1993;12:307–314. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05658.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hao Q-L, Ferris D K, White G, Heisterkamp N, Groffen J. Nuclear and cytoplasmic location of the FER tyrosine kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1180–1183. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.2.1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hao Q-L, Heisterkamp N, Groffen J. Isolation and sequence analysis of a novel human tyrosine kinase gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1587–1593. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoschuetzky H, Aberle H, Kemler R. β-catenin mediates the interaction of the cadherin-catenin complex with epidermal growth factor receptor. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1375–1380. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.5.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huber A H, Nelson W J, Weis W I. Three-dimensional structure of the armadillo repeat region of β-catenin. Cell. 1997;90:871–882. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80352-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huttenlocher A, Lakonishok M, Kinder M, Wu S, Truong T, Knudsen K A, Horwitz A F. Integrin and cadherin synergy regulates contact inhibition of migration and motile activity. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:515–526. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.2.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanner S B, Reynolds A B, Parsons J T. Tyrosine phosphorylation of a 120-kilodalton pp60src substrate upon epidermal growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor stimulation and in polyomavirus middle-T-antigen-transformed cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:713–720. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.2.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keshet E, Itin A, Fischman K, Nir U. The testis-specific transcript (ferT) of the tyrosine kinase FER is expressed during spermatogenesis in a stage-specific manner. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:5021–5025. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.9.5021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim L, Wong T W. The cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase FER is associated with the catenin-like substrate pp120 and is activated by growth factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4553–4561. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kinch M S, Clark G J, Der C J, Burridge K. Tyrosine phosphorylation regulates the adhesions of ras-transformed breast epithelia. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:461–471. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.2.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirkpatrick C M, Peifer M. Not just glue: cell-cell junctions as cellular signaling centers. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:56–65. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(95)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klymkowsky M W, Parr B. A glimpse into the body language of cells: the intimate connection between cell adhesion and gene expression. Cell. 1995;83:5–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90226-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knudsen K A, Soler A P, Johnson K R, Wheelock M J. Interaction of actin with the cadherin/catenin cell-cell adhesion complex via alpha-catenin. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:67–77. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Letwin K, Yee S-P, Pawson T. Novel protein-tyrosine kinase cDNAs related to fes/fps and eph, cloning using anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. Oncogene. 1988;3:621–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marrs J A, Nelson W J. Cadherin cell adhesion molecules in differentiation and embryogenesis. Int Rev Cytol. 1996;165:159–205. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsuyoshi N, Hamaguchi M, Taniguchi S, Nagafuchi A, Tsukita S, Takeichi M. Cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion is perturbed by v-src tyrosine phosphorylation in metastatic fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:703–714. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.3.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller J R, Moon R T. Signal transduction through β-catenin and specification of cell fate during embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2527–2539. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mo Y Y, Reynolds A B. Identification of murine p120 isoforms and heterogeneous expression of p120cas isoforms in human tumor cell lines. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2633–2640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monier-Gavelle F, Duband J L. Cross talk between adhesion molecules: control of N-cadherin activity by intracellular signals elicited by beta1 and beta3 integrins in migrating neural crest cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1663–1681. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.7.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nojima Y, Morino N, Mimura T, Hamasaki K, Furuya H, Sakai R, Sato T, Tachibana K, Morimoto C, Yazaki Y, Hirai H. Integrin-mediated cell adhesion promotes tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas, a Src homology 3-containing molecule having multiple Src homology 2-binding motifs. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15398–15402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papkoff J. Regulation of complexed and free catenin pools by distinct mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4536–4543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paulson R, Jackson J, Immergluck K, Bishop J M. The DFer of Drosophila melanogaster encodes two membrane-associated proteins that can both transform vertebrate cells. Oncogene. 1997;14:641–652. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pawson T, Letwin K, Lee T, Hao Q-L, Heisterkamp N, Groffen J. The FER gene is evolutionarily conserved and encodes a widely expressed member of the FPS/FES protein-tyrosine kinase family. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:5722–5725. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.12.5722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petch L A, Bockholt S M, Bouton A, Parsons J T, Burridge K. Adhesion-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of the p130 src substrate. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:1371–1379. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.4.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Resnitzky D, Gossen M, Bujard H, Reed S I. Acceleration of the G1/S phase transition by expression of cyclins D1 and E with an inducible system. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1669–1679. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reynolds A B, Roesel D J, Kanner S B, Parsons J T. Transformation-specific tyrosine phosphorylation of a novel cellular protein in chicken cells expressing oncogenic variants of the avian cellular src gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:629–638. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.2.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reynolds A B, Daniel J, McCrea P, Wheelock M J, Wu J, Zhang Z. Identification of a new catenin: the tyrosine kinase substrate p120cas associates with E-cadherin complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8333–8342. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reynolds A B, Herbert L, Cleveland J L, Berg S T, Gaut J R. p120, a novel substrate of protein tyrosine kinase receptors and of p60v-src, is related to cadherin-binding factors β-catenin, plakoglobin and armadillo. Oncogene. 1992;7:2439–2445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rimm D L, Koslov E R, Kebriaei P, Cianci C D, Morrow J S. α1(E)-catenin is an actin-binding and -bundling protein mediating the attachment of F-actin to the membrane adhesion complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8813–8817. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruoslahti E, Reed J C. Anchorage dependence, integrins, and apoptosis. Cell. 1994;77:477–478. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shibamoto S, Hayakawa M, Takeuchi K, Hori T, Oku N, Miyazawa K, Kitamura N, Takeichi M, Ito F. Tyrosine phosphorylation of β-catenin and plakoglobin enhanced by hepatocyte growth factor and epidermal growth factor in human carcinoma cells. Cell Adhesion Commun. 1994;1:295–305. doi: 10.3109/15419069409097261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Songyang Z, Carraway III K L, Eck M J, Harrison S C, Feldman R A, Mohammadl M, Schlessinger J, Hubbard S R, Smith D P, Eng C, Lorenzo M J, Ponder B A J, Mayer B J, Cantley L C. Catalytic specificity of protein-tyrosine kinases is critical for selective screening. Nature. 1995;373:536–538. doi: 10.1038/373536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Staddon J M, Smales C, Schulze C, Esch F S, Rubin L L. p120, a p120-related protein (p100), and the cadherin/catenin complex. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:369–381. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.2.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takahashi K, Suzuki K, Tsukatani Y. Induction of tyrosine phosphorylation and association of β-catenin with EGF receptor upon tryptic digestion of quiescent cells at confluence. Oncogene. 1997;15:71–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takeda H, Nagafuchi A, Yonemura S, Tsukita S, Behrens J, Birchmeier W, Tsukita S. V-src kinase shifts the cadherin-based cell adhesion from the strong to the weak state and β-catenin is not required for the shift. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1839–1847. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.ten Hoeve J, Kaartinen V, Fioretos T, Haataja L, Voncken J, Heisterkamp N, Groffen J. Cellular interactions of CRKL an SH2-SH3 adaptor protein. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2563–2567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vuori K, Ruoslahti E. Tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas and cortactin accompanies integrin-mediated cell adhesion to extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22259–22262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]