ABSTRACT

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains are a major challenge for clinicians due, in part, to their resistance to most β-lactams, the first-line treatment for methicillin-susceptible S. aureus. A phenotype termed “NaHCO3-responsiveness” has been identified, wherein many clinical MRSA isolates are rendered susceptible to standard-of-care β-lactams in the presence of physiologically relevant concentrations of NaHCO3, in vitro and ex vivo; moreover, such “NaHCO3-responsive” isolates can be effectively cleared by β-lactams from target tissues in experimental infective endocarditis (IE). One mechanistic impact of NaHCO3 exposure on NaHCO3-responsive MRSA is to repress WTA synthesis. This NaHCO3 effect mimics the phenotype of tarO-deficient MRSA, including sensitization to the PBP2-targeting β-lactam, cefuroxime (CFX). Herein, we further investigated the impacts of NaHCO3 exposure on CFX susceptibility in the presence and absence of a WTA synthesis inhibitor, ticlopidine (TCP), in a collection of clinical MRSA isolates from skin and soft tissue infections (SSTI) and bloodstream infections (BSI). NaHCO3 and/or TCP enhanced susceptibility to CFX in vitro, by both minimum inhibitor concentration (MIC) and time-kill assays, as well as in an ex vivo simulated endocarditis vegetations (SEV) model, in NaHCO3-responsive MRSA. Furthermore, in experimental IE (presumably in the presence of endogenous NaHCO3), pre-exposure to TCP prior to infection sensitized the NaHCO3-responsive MRSA strain (but not the non-responsive strain) to enhanced clearances by CFX in target tissues. These data support the notion that NaHCO3 is acting similarly to WTA synthesis inhibitors, and that such inhibitors have potential translational applications in the treatment of certain MRSA strains in conjunction with specific β-lactam agents.

KEYWORDS: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), β-lactams, NaHCO3-responsive, penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), wall teichoic acid (WTA) synthesis, experimental infective endocarditis (IE)

INTRODUCTION

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains are a major clinical threat due to the large variety of invasive syndromes caused by such strains, as well as their broad antimicrobial resistances (1–3). Recently, however, a novel phenotype has been documented among large collections of clinical MRSA bloodstream infection (BSI) and skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) isolates, termed “NaHCO3-responsiveness”; in this phenotype, many MRSA isolates are rendered “susceptible” in vitro to the β-lactams, cefazolin (CFZ) and oxacillin (OXA), in the presence of physiologically relevant concentrations of NaHCO3 (4–6). The translatability of this in vitro phenotype has been established in both ex vivo and in vivo endocarditis models (4, 7, 8).

Mechanistically, NaHCO3-mediated susceptibility to CFZ and OXA appears related to multiple impacts on penicillin-binding protein (PBP) 2a expression and functionality (9–11). In addition, NaHCO3 has been shown to affect the expression and production of components required for PBP2a activity, including the PBP2a chaperone system, vrsA-prsA, and wall teichoic acid (WTA) synthesis (9, 12). Of interest, disruption of WTA synthesis, with agents such as ticlopidine (TCP), tarocins, and tunicamycin, is also known to sensitize MRSA to β-lactams, especially those that specifically target PBP2 (13–16). These latter anti-WTA agents share the capacity to inhibit the activity of enzymes involved in early WTA synthesis (13, 15–17).

As mentioned above, we recently demonstrated that NaHCO3 was capable of altering WTA production in a small cohort of MRSA BSI isolates, and that NaHCO3 and TCP were similarly capable of sensitizing MRSA to the PBP2-targeting β-lactam, cefuroxime (CFX) (12). There were no further in vitro synergistic enhancements of NaHCO3 plus TCP on CFX sensitization by minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay, suggesting that NaHCO3 and TCP may have the same biological target.

In the present study, we investigated (i) the ability of NaHCO3 and TCP to sensitize MRSA to CFX in BSI and SSTI isolates in both static (MIC) and dynamic (time-kill) assays; and (ii) both the ex vivo and in vivo translatability of in vitro susceptibility assays with CFX, NaHCO3, and/or TCP, utilizing ex vivo simulated endocarditis vegetations (SEV) and rabbit infective endocarditis (IE) models.

RESULTS

In vitro synergy of TCP, NaHCO3, and CFX

Previously, both TCP and NaHCO3 were each shown to sensitize NaHCO3-responsive MRSA BSI isolates to the PBP2-specific inhibitor, CFX (12). In the current cohort, which has been enlarged by the addition of MRSA SSTI isolates, a similar phenotype was observed, wherein NaHCO3-responsive MRSA isolates were sensitized to CFX by TCP or NaHCO3; in contrast, the susceptibilities of non-responsive strains were not impacted by these agents (Table 1). As observed before, the MICs of CFX were similar for NaHCO3-responsive strains exposed to TCP or NaHCO3 alone, although no additional CFX MIC reductions occurred when TCP and NaHCO3 were combined.

TABLE 1.

Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of cefuroxime (CFX) for NaHCO3-responsive and non-responsive MRSA isolates grown in the presence and absence of TCP and/or NaHCO3

| Strain | Isolate source | Cefuroxime MIC (µg/mL) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca-MHB Tris | Ca-MHB Tris 44 mM NaHCO3 | |||||

| W/o TCPa | + TCPb | W/o TCP | + TCP | |||

| NaHCO3-responsive | MRSA 11/11c | BSId | 256 | 8 | 4 | 8 |

| MW2c | BSI | 128 | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| 8010 | SSTId | 256 | 16 | 8 | 16 | |

| 8029 | SSTI | 256 | 8 | 8 | 16 | |

| 8058 | SSTI | 128 | 16 | 16 | 8 | |

| 8074 | SSTI | 256 | 32 | 16 | 32 | |

| 8129 | SSTI | 128 | 16 | 8 | 8 | |

| Non-responsive | COLc | BSI | >512 | >512 | 512 | >512 |

| BMC1001c | BSI | >512 | >512 | >512 | >512 | |

| 8049 | SSTI | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | |

| 8080 | SSTI | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | |

| 8086 | SSTI | 32 | 32 | 32 | 16 | |

| 8096 | SSTI | >256 | >256 | >256 | >256 | |

| 8131 | SSTI | 16 | 16 | 8 | 16 | |

TCP = ticlopidine.

TCP exposure is 32 µg/mL in all conditions.

Data previously published in Ersoy et al. (12).

BSI, bloodstream infection; SSTI, skin and soft tissue infection.

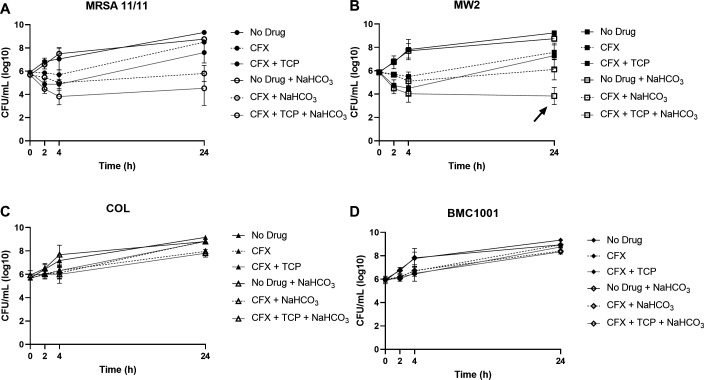

To further quantify the dynamic impacts of TCP and NaHCO3 on CFX susceptibility, time-kill assays were used in four prototype strains: two NaHCO3-responsive (MRSA 11/11 and MW2) and two NaHCO3-non-responsive (COL and BMC1001). Although the MICs of CFX were similar in the presence of TCP or NaHCO3 alone or in combination, the combination of TCP plus NaHCO3 resulted in several logs of increased killing by CFX in NaHCO3-responsive strains at 24 h vs each agent alone, CFX and NaHCO3 in combination, or TCP and CFX in combination (Fig. 1A and B). This triple combination exerted “synergy” for strain MW2 (>2 log10 CFU/mL reductions, P < 0.0001 CFX + TCP + NaHCO3 vs both CFX + TCP or CFX + NaHCO3 at 24-h exposures) (Fig. 1B). This suggested the presence of synergistic bactericidal effects of CFX plus TCP plus NaHCO3 in combination that were not observed in more static MIC assays. As expected, TCP and NaHCO3, alone or in combination, did not enhance bacterial killing by CFX in non-responsive strains (Fig. 1C and D).

Fig 1.

Time-kill curves for NaHCO3-responsive strains MRSA 11/11 (A) and MW2 (B), and non-responsive strains COL (C) and BMC1001 (D) exposed to CFX, with or without NaHCO3 and TCP. Cells were incubated without drug for 3 h to enter log phase. For all assays, drug concentrations are 30 µg/mL CFX and 32 µg/mL TCP.

Ex vivo CFX synergy with NaHCO3 and TCP in the SEV model

This SEV model mimics two key microenvironments that MRSA strains are exposed to in vivo: (i) high-inoculum growth within cardiac vegetations; and (ii) human-equivalent pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) dosing regimens. Thus, this model is widely considered as a “bridge” between in vitro and in vivo studies (18, 19). SEV time-kill assays for the NaHCO3-responsive strain, MW2, demonstrated (i) no difference in 72-h SEV growth curves between exposures to chamber fluid media alone (CA-MHB Tris), CFX alone or media supplemented with NaHCO3 or TCP alone (growth curves for supplementation with NaHCO3 or TCP alone not shown); and (ii) a >3 log10 CFU/g reduction for CFX supplemented media with TCP, NaHCO3, or both, indicating synergy between CFX combined with TCP and/or NaHCO3 (Fig. 2A), as predicted by in vitro MIC studies (Table 1). Neither combination regimen exerted a bactericidal effect over the 72-h exposure period. In contrast, for the non-responsive strains, COL or BMC1001, in the SEV model, neither TCP nor NaHCO3 enhanced killing of CFX, as expected from in vitro studies (Fig. 2B and C; Table 1).

Fig 2.

SEV kill curves for NaHCO3-responsive strain MW2 (A), and non-responsive strains COL (B) and BMC1001 (C) exposed to CFX, with or without NaHCO3 and TCP. CFX dosing mimics human PK/PD, while TCP dosing was optimized to reach a steady state of 8 µg/mL throughout the experiment.

CFX synergy with endogenous NaHCO3 and/or TCP pre-exposures in experimental IE

To investigate the ability of TCP to sensitize MRSA to CFX in the presence of endogenous HCO3, a rabbit model of experimental IE was used. MRSA cells were pre-exposed to TCP prior to infection to “sensitize” them for potential CFX synergy in vivo. Since TCP has potent anti-platelet aggregation activity and the pathogenesis of IE is highly platelet-dependent (15, 20–22), this pre-exposure strategy was employed rather than direct TCP treatments of animals. Furthermore, TCP is rapidly and extensively metabolized in the liver (23). As predicted by MIC, time-kill, and SEV data above, CFX treatment of rabbits infected with the “un-sensitized” NaHCO3-responsive strain, MW2, resulted in modest but significant reductions (0.5 to 2 log10 CFU/g reductions) in MRSA bio-burdens in all target tissues (Fig. 3A). Of note, when MW2 was “sensitized” by TCP exposure prior to infection, CFX treatment resulted in significantly more MRSA killing (4 to 7 log10 CFU/g reductions) than infection with un-sensitized cells, to near sterilization (detection-limit) levels in all three target tissues (Fig. 3A). As expected, CFX treatment of rabbits infected with the non-responsive strain COL, with or without TCP priming, did not result in any reductions of target tissue MRSA bio-burdens (Fig. 3B).

Fig 3.

Tissue burdens (CFU/g) of NaHCO3-responsive strain MW2 (A) and non-responsive strain COL (B) following infection in a rabbit model of IE. Rabbits were grouped as follows: control = infected with MW2 or COL and untreated; CFX = infected with MW2 or COL and treated with CFX; TCP = infected with MW2 or COL that were exposed to TCP prior to infection and untreated; TCP + CFX = infected with MW2 or COL that were exposed to TCP prior to infection and treated with CFX. Veg. = cardiac vegetation, Kid. = kidney, Spl. = spleen. Statistics were calculated by an unpaired Student’s t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

The ability to “re-purpose” antibiotics with broad efficacy, which are relatively inexpensive and have well-known modes of action and favorable safety profiles, would be a great benefit to physicians in treating complicated MRSA infections (24, 25). Current treatment options for MRSA infections are more limited, and tend to be less effective and more toxic than standard-of-care β-lactams used for the treatment of methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) (26–28).

In the current study, we demonstrated five major findings: (i) BSI and SSTI NaHCO3-responsive (but not NaHCO3-non-responsive) MRSA isolates were sensitized to growth inhibition and killing by the widely used, broad-spectrum, second-generation cephalosporin, CFX (29), in the presence of NaHCO3 or TCP both in vitro and ex vivo; (ii) in growth-inhibitory MIC assays, the reductions in baseline CFX MICs, when combined with either NaHCO3 or TCP alone, were not synergistically enhanced by combining all three agents (suggesting that NaHCO3 and TCP may have the same biological target); (iii) in contrast, in time-kill assays, the combination of TCP plus NaHCO3 did, indeed, enhance the activity of CFX against NaHCO3-responsive MRSA, as compared to CFX plus either TCP or NaHCO3; (iv) in a SEV model, exposure to CFX with TCP and/or NaHCO3 resulted in similar levels of synergistic growth inhibition compared to CFX exposure alone in NaHCO3-responsive MRSA; and (v) TCP pre-exposures sensitized NaHCO3-responsive MRSA to CFX-mediated target tissue MRSA clearances, in the presence of endogenous HCO3 in experimental IE (i.e., HCO3 naturally existing in blood and tissues, typically ranging from ~22 to 45 mM [4, 30]).

Of note, there were discrepancies between the various in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo assays in determining whether combining CFX with both TCP and NaHCO3 resulted in enhanced growth inhibition compared to exposure to CFX with either TCP or NaHCO3 alone. Although the MIC and SEV assays did not demonstrate enhanced synergy with the triple combination (CFX + TCP + NaHCO3), such enhanced efficacy was observed by time-kill assay and pre-exposure to TCP in the experimental rabbit IE model, in NaHCO3-responsive MRSA. We attribute these discrepancies to several factors, including (i) differences in the “metabolic state” of the organism in MIC and SEV vs time-kill and in vivo assays, making MRSA in the latter conditions more “susceptible” to such synergy; and/or (ii) the increased production of the inhibitory target (WTA) when initially exposed to TCP and CFX during exponential-phase growth (time-kill assays). Regarding the differences in triple combination synergy in the ex vivo vs in vivo model, the latter used TCP priming, which appears to further sensitize NaHCO3-responsive MRSA to the effects of CFX. Furthermore, exposure to WTA synthesis-inhibiting molecules has been shown to directly reduce MRSA virulence (31), which may explain the enhanced clearance of TCP pre-exposed NaHCO3-responsive MRSA by CFX in the experimental IE model.

Antibiotic susceptibility is strongly tied to the growth state of the organism, which typically exhibits higher levels of “resistance” to antimicrobials during non-planktonic growth in a biofilm (vs planktonic growth in standard in vitro growth media) (32). These differences can confound in vitro-determined levels of antibiotic resistance, which typically measures resistance in a planktonic state, against those exhibited during biofilm growth as found in selected host infections. Importantly, the studies presented herein demonstrate that NaHCO3 and TCP sensitize MRSA to CFX in both in vitro, planktonic growth states (MIC and time-kill assays), as well as in the ex vivo SEV model, in which MRSA cells are growing deeply within platelet-fibrin clots, in a biofilm-like state similar to what is observed during infection within a human endovascular lesion in endocarditis (8, 33). These similar sensitization outcomes observed in both these models, in which MRSA growth states differ greatly, further support the notion that both NaHCO3 and TCP would be capable of sensitizing certain MRSA strains (i.e., NaHCO3-responsive strains) to CFX during actual human infection. Finally, the in vivo verification of the efficacy of CFX in TCP-pretreated NaHCO3-responsive strains (in the presence of endogenously derived NaHCO3) in clearing MRSA from human-like infected cardiac vegetations fully underscores the above concepts.

The WTA biosynthetic pathway is a promising target for new antimicrobials, as WTAs are involved in a wide range of key physiological functions including bacterial:host interactions, bacterial virulence, biofilm formation, and peptidoglycan functionality, including cell division and autolysin activity (34). Additionally, WTAs are essential for the cooperative action of PBP2 and PBP4 that results in highly cross-linked peptidoglycan. Both impairment of the first step of WTA synthesis, mediated by the transferase, TarO, and deletion of tarO result in sensitization of MRSA to many β-lactams, including those specific for PBP2, such as CFX (15). Exposure to NaHCO3 simulates ΔtarO-deletion phenotypes in NaHCO3-responsive strains; however, NaHCO3 has no direct impact on tarO gene expression, either transcriptionally or translationally (12). Thus, NaHCO3 appears to impact TarO post-translationally and reduces WTA production exclusively in NaHCO3-responsive MRSA (12).

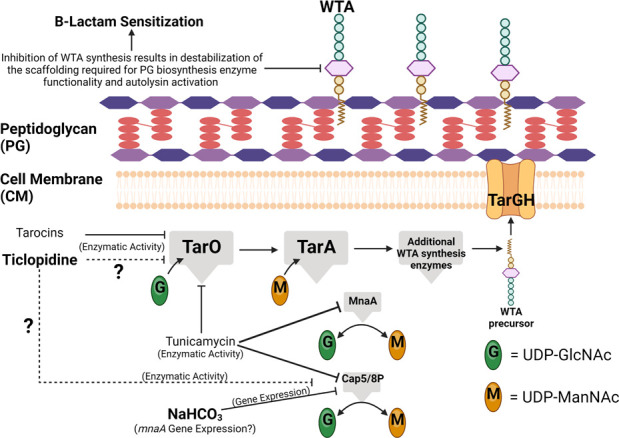

The precise anti-WTA mechanisms of TCP are not totally defined; however, like NaHCO3, TCP most likely targets TarO and synergizes with CFX against MRSA (15, 17). It was previously reported that TCP inhibits the enzymatic activity of TarO (15); however, it remains unclear if TCP directly binds to TarO or whether it inhibits the enzymatic activity of TarO via secondary pathways (17). One potential secondary target of TCP and NaHCO3 is Cap5P, the 2’-epimerase that interconverts UDP-GlcNAc and UDP-ManNAc, the substrates of TarO and another early WTA synthesis step, mediated by TarA (16, 35). Inhibition of UDP-GlcNAc and UDP-ManNAc interconversion has been shown to inhibit WTA synthesis and sensitize MRSA to β-lactams (16). Interestingly, NaHCO3 was previously demonstrated to inhibit the expression of cap5/8P specifically in NaHCO3-responsive strains (36), and certain cap5P genotypes were specific to non-responsive MRSA strains in a collection of SSTI isolates (6). Although speculative, these latter data provide one potential mechanism in which NaHCO3 and TCP may be inhibiting the expression and/or function of cap5P/Cap5P, thereby, repressing the enzymatic activity of TarO and disrupting WTA synthesis specifically in NaHCO3-responsive MRSA. A schematic illustrating this hypothesis is provided in Fig. 4.

Fig 4.

Schematic of potential impacts of TCP and NaHCO3 on WTA biosynthesis. Previous studies have demonstrated that TCP inhibits WTA biosynthesis (similarly to tarocins and tunicamycin), potentially via impacts on TarO functionality (13, 15, 17). NaHCO3 has been demonstrated to specifically inhibit the expression of cap5/8P in a NaHCO3-responsive MRSA strain (36). Inhibition of cap5/8P expression, coupled with inhibition of TarO enzymatic activity (via direct or indirect mechanisms), could result in disruption of WTA biosynthesis, as previously observed (12), sensitizing NaHCO3-responsive MRSA to β-lactams. Created with BioRender.com.

Deletion of tarO or exposure to targocil (another WTA synthesis-inhibiting agent that targets the translocator, TarG) alters the expression of a similar cadre of virulence and peptidoglycan biosynthesis genes as observed with exposure to NaHCO3 in NaHCO3-responsive MRSA, including pbp2, fmtA, vraX, sasD, fnbA, and fnbB (14, 36, 37). This provides yet another line of evidence that NaHCO3 may well impact multiple steps in the WTA biosynthetic pathway. Assessing the ability of NaHCO3 and/or TCP to further sensitize a ΔtarO NaHCO3-responsive MRSA strain to CFX may reveal whether these compounds do, in fact, target TarO and/or act on another aspect of WTA synthesis. In addition, studies utilizing the TarG inhibitor, L-638, in combination with either NaHCO3 or TCP may help elucidate their combined impacts on early WTA synthesis. Inhibition of TarG by L-638 has been shown to inhibit cell growth, and suppression of this activity can be achieved by concomitant exposure to early WTA synthesis inhibitors (17).

Other known early WTA synthesis inhibitors, such as tunicamycin and tarocins A and B, have also been shown to sensitize various MRSA strains (including the NaHCO3-non-responsive strain, COL) to a number of β-lactams, perhaps indicating a more potent or broader spectrum of anti-WTA activity than seen with TCP and/or NaHCO3 (13, 17). Furthermore, tunicamycin and tarocins showed higher in vitro inhibitory activity against TarO than TCP, and although both drug classes act through different mechanisms on WTA synthesis, their synergic effect with β-lactams was demonstrated to be more potent than the effect of TCP (17). As only a relatively modest synergistic effect was observed between NaHCO3 and/or TCP with CFX in vitro and ex vivo in the present study, it would be of interest to determine whether a more robust level of synergy might be observed between NaHCO3, β-lactams, and either tunicamycin or tarocins in vitro and ex vivo. Indeed, the significant synergy demonstrated with TCP “sensitizing” used in the in vivo IE model indicates a potential role of sequential inhibition of this pathway for maximal anti-MRSA effects. Furthermore, in vivo studies in a rabbit IE model, similar to the present studies, utilizing selected β-lactams and tunicamycin or tarocins for the treatment of NaHCO3-responsive and non-responsive MRSA would be very informative. Such investigations are currently in progress in our laboratories.

One limitation of this work is the lack of consensus on the specific target/mechanism of action of TCP. Although some research suggests a direct impact on the enzymatic activity of TarO (15), other studies suggest that TarO is not the specific target of this molecule (17). Further supporting the notion that TCP does not directly affect TarO is its specificity for NaHCO3-responsive MRSA, a strain selectivity not observed with other TarO inhibitors (13, 17). As proposed above, it is possible that TCP also targets the 2’-epimerase Cap5P, a known target of NaHCO3 in NaHCO3-responsive strains, similar to the ability of tunicamycin to target the 2’-epimerase MnaA (16). Additional investigations are needed to identify the specific targets of both NaHCO3 and TCP, as they relate to WTA synthesis, and the mechanism of their ability to specifically sensitize NaHCO3-responsive MRSA strains to β-lactams.

Overall, our studies herein provide evidence of the translatability of the NaHCO3-responsive phenotype as it relates to the sensitization of MRSA to selected β-lactams in vivo. NaHCO3 appears to be sensitizing MRSA to β-lactams, in part, via impacts on WTA synthesis. Future development of inhibitors of the WTA pathway holds a promise to “rescue” β-lactam effectiveness for clinical MRSA treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates and growth conditions

The MRSA isolates utilized in this study are clinical BSI or SSTI isolates that have been previously described and characterized for their NaHCO3-responsive phenotypes (4, 6). Isolates were stored at −80°C until thawed for use and isolated on tryptic soy agar (TSA). For all in vitro susceptibility assays, cells were grown in cation-adjusted Mueller Hinton Broth (BD, Difco) with 100 mM Tris buffer (CA-MHB Tris, pH 7.3 ± 0.1) ± 44 mM NaHCO3 (CA-MHB Tris, 44 mM NaHCO3) at 37°C. For in vivo studies, cells were grown overnight at 37°C in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI, BBL) with or without 32 µg/mL TCP, as this dose of TCP provided the best synergy with CFX in in vitro susceptibility assays. Exposure (“sensitizing”) to TCP did not impact overnight cell density prior to animal infection (Fig. S1).

MIC and quantitative time-kill assays

MIC and time-kill assays were carried out as previously described (4). Briefly, for MIC assays, cells were grown overnight in the indicated growth medium, then diluted to 5 × 105 CFU/mL into the same medium containing twofold serial dilutions of CFX, with or without 32 µg/mL TCP, on 96-well plates, as per Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines (38, 39). Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C, and the MIC was scored at the first well in which turbidity was visually reduced. For time-kill assays, cells were grown overnight in the indicated growth medium, then diluted to 5 × 105 CFU/mL in the same growth medium on 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C for 3 h to reach log phase. After reaching the log phase, the cells were diluted back to 5 × 105 CFU/mL into the same growth medium in the presence or absence of 30 µg/mL CFX and 32 µg/mL TCP. This TCP concentration was selected following extensive piloting studies revealing this to be the optimal concentration to disclose synergy between TCP and CFX in vitro. Viable cells were quantified by plating on TSA at 0, 2, 4, and 24 h following incubation with drug.

Ex vivo PK-PD SEV model

Antibiotic PK-PD simulations were performed with ex vivo SEVs prepared as previously described (8). SEVs contain 3–3.5 g/dL of albumin and 6.8–7.4 g/dL of total protein (equating to human physiologic levels) and weigh ~0.7 g. The central (“fluid”) compartment model for the SEVs consists of a 150-mL flask glass, maintained at 35–37°C ambient air and fresh media (MHB or MHB + 44 mM NaHCO3) instilled via a continuous syringe pump system (New Era Pump Systems, Inc.). The models were performed in duplicate flasks to ensure reproducibility with two SEVs collected for each time point (n = 4 SEVs per time point). Simulated human-equivalent antibiotic regimens used for severe infections were derived from human PK data as follows: CFX 750 mg every 8 h, infused over 2 min (Cmax 50 µg/mL, Cmin 0.72 µg/mL, T1/2 1.2 h). Standard TCP regimens of 250 mg twice daily in humans display nonlinear pharmacokinetics, with a terminal half-life of repeated dosing of 4–5 d. Therefore, we simulated steady-state concentrations during the terminal half-life (8 µg/mL) (40) by including TCP 8 µg/mL in the model and supplemental media over a 72-h duration to achieve this constant TCP exposure while simulating the CFX elimination rate constant (ke = 0.53 h−1). Model SEVs were sampled and processed for CFU enumeration as previously described (8).

Rabbit model of MRSA IE

To quantify the synergistic impacts of TCP and endogenous HCO3 on CFX activity in NaHCO3-responsive vs non-responsive strains, a well-characterized rabbit model of indwelling catheter-induced aortic valve IE was used (41). Rabbits were infected intravenously at 48 h after catheter placement with 2 × 105 CFU/animal of the indicated strain; this inoculum represents the ID95 for inducing IE as established by extensive pilot experiments for each strain (data not shown). At 24-h post-infection, the animals were randomized into either untreated control groups (sacrificed at this time-point as a therapeutic baseline) or CFX-treated groups (100 mg/kg administered by intramuscular injection, tid for 4 d). This CFX dosing regimen was based on previously established CFX dosing strategies in MSSA rabbit IE models (4, 42, 43).

For CFX-treated animals, at 24 h after the last CFX treatment (to circumvent any antibiotic carryover effects), animals were sacrificed, and their cardiac vegetations, kidneys, and spleen were aseptically removed and quantitatively cultured on TSA plates as previously described (44). For untreated controls, animals were similarly sacrificed at 24-h post-infection to establish a baseline target tissue MRSA bio-burden to compare to CFX-treated animals. Counts were expressed as mean log10 CFU per gram of tissue (± SD). The limit of detection in target organ cultures in this model, based on average target tissue weights, is ≤2 log10 CFU/g. All culture-negative vegetations, although designated as “sterile,” were still assigned a limit-of-detection log10 CFU/g designation based on their weights, for statistical purposes, to enable comparisons between groups. This is a standard procedure used in this model.

Statistical analyses

An unpaired Student’s t-test was used to make all statistical comparisons, with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001. For in vitro kill curves, statistics were calculated on the viable cell means at 24 h for each group.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the following grant from the National Institutes of Health: 1RO1-AI146078 (to A.S.B.).

Conceptualization: S.C.E., A.S.B., R.A.P.; methodology: S.C.E., W.E.R., W.A.; formal analysis: S.C.E., W.E.R., W.A.; investigation: S.C.E., W.E.R., W.A., S.H.F., S.L.M., A.M.E.; resources: A.S.B.; writing – original draft: S.C.E., A.S.B.; writing – review and editing: S.C.E., A.S.B., R.A.P., H.F.C.; supervision: A.S.B.; project administration: A.S.B.; funding acquisition: A.S.B.

Contributor Information

Selvi C. Ersoy, Email: selvi.ersoy@lundquist.org.

Helen Boucher, Tufts University - New England Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.01627-23.

Impact of ticlopidine pre-exposure on overnight cell density.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Boucher H, Miller LG, Razonable RR. 2010. Serious infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis 51:S183–97. doi: 10.1086/653519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Purrello SM, Garau J, Giamarellos E, Mazzei T, Pea F, Soriano A, Stefani S. 2016. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: a review of the currently available treatment options. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 7:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2016.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shorr AF. 2007. Epidemiology and economic impact of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: review and analysis of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics 25:751–768. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200725090-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ersoy SC, Abdelhady W, Li L, Chambers HF, Xiong YQ, Bayer AS. 2019. Bicarbonate resensitization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to β-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 63:e00496-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00496-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ersoy SC, Otmishi M, Milan VT, Li L, Pak Y, Mediavilla J, Chen L, Kreiswirth B, Chambers HF, Proctor RA, Xiong YQ, Fowler VG, Bayer AS. 2020. Scope and predictive genetic/phenotypic signatures of bicarbonate (NaHCO3) responsiveness and β-lactam sensitization in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:e02445-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02445-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ersoy SC, Madrigal SL, Proctor RA, Chen L, Mediavilla JR, Kreiswirth BN, Flores EA, Miller LG, Patel R, Chambers HF, Bayer AS. 2023. Phenotypic and genotypic correlates of the NaHCO3-responsive phenotype among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates from skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs). Clin microbiol infect in revision [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ersoy SC, Rose WE, Patel R, Proctor RA, Chambers HF, Harrison EM, Pak Y, Bayer AS. 2021. A combined phenotypic-genotypic predictive algorithm for in vitro detection of bicarbonate: β-lactam sensitization among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Antibiotics (Basel) 10:1089. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10091089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rose WE, Bienvenida AM, Xiong YQ, Chambers HF, Bayer AS, Ersoy SC. 2020. Ability of bicarbonate supplementation to sensitize selected methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains to β-lactam antibiotics in an ex vivo simulated endocardial vegetation model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 64:e02072-19. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02072-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ersoy SC, Chambers HF, Proctor RA, Rosato AE, Mishra NN, Xiong YQ, Bayer AS. 2023. Impact of bicarbonate on PBP2a production, maturation, and functionality in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 65:e02621-20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02621-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ersoy SC, Chan LC, Yeaman MR, Chambers HF, Proctor RA, Ludwig KC, Schneider T, Manna AC, Cheung A, Bayer AS. 2022. Impacts of NaHCO3 on β-lactam binding to PBP2a protein variants associated with the NaHCO3-responsive versus NaHCO3-non-responsive phenotypes. Antibiotics 11:462. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11040462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ersoy SC, Manna AC, Proctor RA, Chambers HF, Harrison EM, Bayer AS, Cheung A. 2022. The NaHCO3-responsive phenotype in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is influenced by mecA genotype. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 66:e0025222. doi: 10.1128/aac.00252-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ersoy SC, Gonçalves B, Cavaco G, Manna AC, Sobral RG, Nast CC, Proctor RA, Chambers HF, Cheung A, Bayer AS. 2022. Influence of sodium bicarbonate on wall teichoic acid synthesis and β-lactam sensitization in NaHCO3-responsive and nonresponsive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol Spectr 10:e0342222. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.03422-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Campbell J, Singh AK, Santa Maria JP, Kim Y, Brown S, Swoboda JG, Mylonakis E, Wilkinson BJ, Walker S. 2011. Synthetic lethal compound combinations reveal a fundamental connection between wall teichoic acid and peptidoglycan biosyntheses in Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Chem Biol 6:106–116. doi: 10.1021/cb100269f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Campbell J, Singh AK, Swoboda JG, Gilmore MS, Wilkinson BJ, Walker S. 2012. An antibiotic that inhibits a late step in wall teichoic acid biosynthesis induces the cell wall stress stimulon in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:1810–1820. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05938-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Farha MA, Leung A, Sewell EW, D’Elia MA, Allison SE, Ejim L, Pereira PM, Pinho MG, Wright GD, Brown ED. 2013. Inhibition of WTA synthesis blocks the cooperative action of PBPs and sensitizes MRSA to β-lactams. ACS Chem Biol 8:226–233. doi: 10.1021/cb300413m [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mann PA, Müller A, Wolff KA, Fischmann T, Wang H, Reed P, Hou Y, Li W, Müller CE, Xiao J, Murgolo N, Sher X, Mayhood T, Sheth PR, Mirza A, Labroli M, Xiao L, McCoy M, Gill CJ, Pinho MG, Schneider T, Roemer T. 2016. Chemical genetic analysis and functional characterization of staphylococcal wall teichoic acid 2-epimerases reveals unconventional antibiotic drug targets. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005585. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee SH, Wang H, Labroli M, Koseoglu S, Zuck P, Mayhood T, Gill C, Mann P, Sher X, Ha S, et al. 2016. TarO-specific inhibitors of wall teichoic acid biosynthesis restore β-lactam efficacy against methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Sci Transl Med 8:329ra32. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad7364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rose WE, Leonard SN, Rybak MJ. 2008. Evaluation of daptomycin pharmacodynamics and resistance at various dosage regimens against Staphylococcus aureus isolates with reduced susceptibilities to daptomycin in an in vitro pharmacodynamic model with simulated endocardial vegetations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52:3061–3067. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00102-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rose WE, Rybak MJ, Kaatz GW. 2007. Evaluation of daptomycin treatment of Staphylococcus aureus bacterial endocarditis: an in vitro and in vivo simulation using historical and current dosing strategies. J Antimicrob Chemother 60:334–340. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sharis PJ, Cannon CP, Loscalzo J. 1998. The antiplatelet effects of ticlopidine and clopidogrel. Ann Intern Med 129:394–405. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-5-199809010-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sullam PM, Bayer AS, Foss WM, Cheung AL. 1996. Diminished platelet binding in vitro by Staphylococcus aureus is associated with reduced virulence in a rabbit model of infective endocarditis. Infect Immun 64:4915–4921. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.4915-4921.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ford I, Douglas CW. 1997. The role of platelets in infective endocarditis. Platelets 8:285–294. doi: 10.1080/09537109777159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Farid NA, Kurihara A, Wrighton SA. 2010. Metabolism and disposition of the thienopyridine antiplatelet drugs ticlopidine, clopidogrel, and prasugrel in humans. J Clin Pharmacol 50:126–142. doi: 10.1177/0091270009343005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Waters EM, Rudkin JK, Coughlan S, Clair GC, Adkins JN, Gore S, Xia G, Black NS, Downing T, O’Neill E, Kadioglu A, O’Gara JP. 2017. Redeploying β-lactam antibiotics as a novel antivirulence strategy for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. J Infect Dis 215:80–87. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bayer AS, Xiong YQ. 2017. Redeploying β-lactams against Staphylococcus aureus: repurposing with a purpose. J Infect Dis 215:11–13. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Edwards B, Andini R, Esposito S, Grossi P, Lew D, Mazzei T, Novelli A, Soriano A, Gould IM. 2014. Treatment options for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection: where are we now? J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McDanel JS, Perencevich EN, Diekema DJ, Herwaldt LA, Smith TC, Chrischilles EA, Dawson JD, Jiang L, Goto M, Schweizer ML. 2015. Comparative effectiveness of beta-lactams versus vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections among 122 hospitals. Clin Infect Dis 61:361–367. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Castañeda X, García-De-la-Mària C, Gasch O, Pericàs JM, Soy D, Cañas-Pacheco M-A, Falces C, García-González J, Hernández-Meneses M, Vidal B, Almela M, Quintana E, Tolosana JM, Fuster D, Llopis J, Dahl A, Moreno A, Marco F, Miró JM, Hospital Clínic Endocarditis Study Group . 2021. Effectiveness of vancomycin plus cloxacillin compared with vancomycin, cloxacillin and daptomycin single therapies in the treatment of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in a rabbit model of experimental endocarditis. J Antimicrob Chemother 76:1539–1546. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkab069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perry CM, Brogden RN. 1996. Cefuroxime axetil. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs 52:125–158. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199652010-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fenn WO. 1928. The carbon dioxide dissociation curve of nerve and muscle. Am J Physiol 85:207–223. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1928.85.2.207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. El-Halfawy OM, Czarny TL, Flannagan RS, Day J, Bozelli JC, Kuiack RC, Salim A, Eckert P, Epand RM, McGavin MJ, Organ MG, Heinrichs DE, Brown ED. 2020. Discovery of an antivirulence compound that reverses β-lactam resistance in MRSA. Nat Chem Biol 16:143–149. doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0401-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zapotoczna M, McCarthy H, Rudkin JK, O’Gara JP, O’Neill E. 2015. An essential role for coagulase in Staphylococcus aureus biofilm development reveals new therapeutic possibilities for device-related infections. J Infect Dis 212:1883–1893. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zapotoczna M, O’Neill E, O’Gara JP. 2016. Untangling the diverse and redundant mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005671. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Neuhaus FC, Baddiley J. 2003. A continuum of anionic charge: structures and functions of D-alanyl-teichoic acids in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67:686–723. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.686-723.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kiser KB, Bhasin N, Deng L, Lee JC. 1999. Staphylococcus aureus cap5P encodes a UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase with functional redundancy. J Bacteriol 181:4818–4824. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.16.4818-4824.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ersoy SC, Hanson BM, Proctor RA, Arias CA, Tran TT, Chambers HF, Bayer AS. 2021. Impact of bicarbonate-β-lactam exposures on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) gene expression in bicarbonate-β-lactam-responsive vs. non-responsive strains. Genes (Basel) 12:1650. doi: 10.3390/genes12111650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lu Y, Chen F, Zhao Q, Cao Q, Chen R, Pan H, Wang Y, Huang H, Huang R, Liu Q, Li M, Bae T, Liang H, Lan L. 2023. Modulation of MRSA virulence gene expression by the wall teichoic acid enzyme TarO. Nat Commun 14:1594. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-37310-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Patel J, Cockerill F, Alder J, Bradford P, Eliopoulos G, Hardy D, Hindler J, Jenkins S, Lewis J, Miller L. 2014. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-fourth informational supplement. Vol. 34. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cockerill FR. 2012. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically: approved standard. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). [Google Scholar]

- 40. Desager JP. 1994. Clinical pharmacokinetics of ticlopidine. Clin Pharmacokinet 26:347–355. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199426050-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abdelhady W, Bayer AS, Seidl K, Moormeier DE, Bayles KW, Cheung A, Yeaman MR, Xiong YQ. 2014. Impact of vancomycin on sarA-mediated biofilm formation: role in persistent endovascular infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Infect Dis 209:1231–1240. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McColm AA, Ryan DM, Acred P. 1984. Comparison of ceftazidime, cefuroxime and methicillin in the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis in rabbits. J Antimicrob Chemother 14:373–377. doi: 10.1093/jac/14.4.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Steckelberg JM, Rouse MS, Tallan BM, Osmon DR, Henry NK, Wilson WR. 1993. Relative efficacies of broad-spectrum cephalosporins for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus experimental infective endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 37:554–558. doi: 10.1128/AAC.37.3.554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Garcia-de-la-Maria C, Xiong YQ, Pericas JM, Armero Y, Moreno A, Mishra NN, Rybak MJ, Tran TT, Arias CA, Sullam PM, Bayer AS, Miro JM. 2017. Impact of high-level daptomycin resistance in the Streptococcus mitis group on virulence and survivability during daptomycin treatment in experimental infective endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02418-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02418-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Impact of ticlopidine pre-exposure on overnight cell density.