Abstract

Objective:

Addressing family psychosocial and mental health needs in the perinatal and early childhood period has a significant impact on long-term maternal and child health and is key to achieving health equity. We aimed to (1) describe and evaluate the role of an Early Childhood Community Health Worker (EC-CHW) to address psychosocial needs and improve psychosocial well-being for families in the perinatal period, and (2) examine factors associated with completion of goals.

Methods:

An EC-CHW program was modeled after an existing hospital CHW program for children with special healthcare needs and chronic disease. An evaluation was conducted using repeated measures to assess improvements in psychosocial outcomes such as family stress and protective factors after participating in the EC-CHW program. Linear regression was also used to assess factors associated with completion of goals.

Results:

Over a 21-month period (January 2019-September 2020), 161 families were referred to the EC-CHW. The most common reasons for referral included social needs and navigating systems for child developmental and behavioral concerns. There were high rates of family engagement in services (87%). After 6 months, families demonstrated statistically significant improvements in protective factors including positive parenting knowledge and social support. Only 1 key predictor variable, maternal depression, showed significant associations with completion of goals in the multivariable analysis.

Conclusions:

This study demonstrated the need for, and potential impact of an EC-CHW in addressing psychosocial and mental health needs in the perinatal period, and in a primary care setting. Impacts on protective factors are promising.

Keywords: community health worker (CHW), psychosocial, early intervention, medical home

Introduction

Research demonstrates the impact of psychosocial factors on health outcomes, especially during the perinatal and early childhood period. For instance, fetal and child brains and bodies are affected by exposure to toxic stress and other factors associated with social disadvantages, potentially leading to chronic medical conditions such as hypertension, developmental delays, mental health problems, and thwarted cognitive and overall potential.1 -3

The “medical home” model has been adopted to offer prevention services and provide comprehensive care to address psychosocial needs.4,5 In this model, screening for psychosocial factors, such as Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) and maternal depression, helps uncover some of the upstream causes of many childhood developmental and behavioral concerns. It may also assist in matching needs to appropriate resources as well as help mitigate the impact of toxic stress. There continues to be a gap however, in ensuring families get the referrals and services they need.6 -8 Many referral sites are under-resourced, and families are often challenged with navigating complex systems, which limits uptake. In addition, stigma and misinformation related to psychosocial labels, further limit engagement.9,10 Without effective methods to address these barriers, healthcare providers remain hesitant to address psychosocial health needs. 11

The integration of Community Health Workers (CHWs) to address this gap in primary care shows great promise. CHWs, who are often trusted peers or community members, minimize barriers to care such as stigma and mistrust. CHWs have long been an asset to primary care practices in managing chronic conditions such as asthma and diabetes, and supporting families of children with special healthcare needs. 12 They have also been linked to improved health outcomes among racial and ethnic minority communities with disparities in access to services.13,14 However, the role of CHWs to specifically address perinatal and early childhood psychosocial health within primary care settings is less well-established. The use of CHWs in the perinatal and early childhood periods may be especially helpful given their focus on families and communities rather than individual patients. In particular, mothers often lose healthcare coverage after the immediate post-natal period, which might lead to unaddressed physical and social-emotional needs that affect the entire family. Psycho-social health needs may be appropriately addressed by trusted community health workers, who are often more familiar and adept at social services and community resources than other healthcare providers. This is a key advantage during the current mental health crisis and behavioral health resource shortage facing our nation.

To address this need, an Early Childhood CHW (EC-CHW) role was created at a large academic medical center that serves a largely immigrant community with high rates of poverty and suboptimal psychosocial outcomes. This study aims to describe and evaluate the role of the EC-CHW; specifically, to assess its effectiveness in (1) improving psychosocial well-being, and (2) completing goals for families referred.

Methods

Setting

The EC-CHW program was developed as a collaborative effort between Pediatrics, Obstetrics & Gynecology (Ob/Gyn), Behavioral Health and Community Based Organizations (CBOs). It was created within 1 of 4 primary care practices of the NewYork Presbyterian Hospital-Columbia University Irving Medical Center. This system has a Center for Community Health Navigation (CCHN) that sub-contracts CHWs with CBOs offering social services needed by patients with chronic diseases such as asthma and diabetes. 12

The practice sees 3200 pediatric patients per year, with 1200 ages 0 to 5 years, and 1900 Ob/Gyn patients per year. Much of the population identifies as Hispanic (71%), and half were born outside the US. A quarter to half of the families have household incomes below the federal poverty level and 30% of adults have not graduated from high school.15 -17

Disparities in perinatal and early childhood health indicators exist. For example, in 2019 infant mortality rates were 5.2 per 1000 births compared to 4.1 per 1000 citywide. Rates of exclusive breastfeeding were 32.8% compared to 43.4% citywide. Of children who were referred to Early Intervention in New York City, 19% of those in communities of color were never evaluated compared to 6% in predominantly white communities. 18

Description of the Early Childhood CHW Program

The EC-CHW role was created in partnership with an existing community partner, Northern Manhattan Perinatal Partnership (NMPP), which focuses on maternal and child health. One EC-CHW was hired during the initial pilot year (2018), and a second was added to the team in 2019. Both were fluent in Spanish (and 1 in Portuguese), and both were bicultural workers who lived in the community served.

Hiring, training, and all supervision for the CHWs were jointly accomplished by the healthcare and community partner teams, including developmental and behavioral pediatricians, general pediatric and Ob/Gyn faculty, social workers, integrated mental health specialists, and community partner leaders. Training included topics such as managing maternal stress, breastfeeding, positive parenting, SDOH, trauma informed care, early childhood normative developmental and behavioral milestones, and early childhood education programs.

The EC-CHW role was unique in that prevention, rather than management of chronic illness, was emphasized. Therefore, referral criteria were based primarily on the age and stage of the family unit (perinatal and early childhood ages of 0-5 years), rather than a particular medical condition as in many other established CHW programs.

Referrals were at the discretion of health providers, other health team members including social workers for example, and families. In addition, the EC-CHWs conducted outreach to caregivers in the waiting room. Early in the program, before the COVID-19 pandemic, referrals were often made via “warm-handoff” during routine primary care visits. During the pandemic referrals were made in the electronic medical record and EC-CHWs contacted families within 48 hours via phone.

Based on clinician-identified level of risk (from either universal screening—for SDOH, maternal depression and intimate partner violence, or provider discretion) and family preference, families were either involved in a “full” or “brief” intervention to allow for flexibility and engagement. Families in the full intervention received at least 1 comprehensive intake with baseline assessment questions, goal setting with the family, collaborative action steps and frequent follow up usually on a bimonthly basis. Field and home visits were also conducted at the discretion of the family and CHWs. Families in the brief intervention did not have a comprehensive intake, or long term follow up, and instead were assisted with connections to psychosocial services over <3 interactions. Services offered to both full and brief level participants included but were not limited to: identification of local maternal-child programs (such as “Mommy-and-Me” classes, or breastfeeding support groups), enrollment in Early Intervention (EI) or special education (CPSE) services, daycare registration, legal support, Supplemental Nutrition Access Program (SNAP), and/or Women Infant Children (WIC) benefit enrollment, access to food pantries, and public housing application support. The EC-CHWs also provided psycho-education around key messages including maternal self-care, normative child development & behavior, and attachment, learned during their training described above.

Weekly case conference team meetings took place with participants from both institutions including a pediatrician, psychologist, social worker, NewYork Presbyterian Hospital program coordinator, NMPP coordinator, and EC-CHWs. The knowledge and expertise used for case navigation was maximized and a co-management process was established. Documentation into the EMR of case status and outcomes occurred during the team meetings so that referring providers could be kept abreast of the status of their referrals.

Data Collection and Variables Description

To assess for improvements in psychosocial wellbeing over time a secondary data analysis was conducted. Measures including family stress levels, and protective factors were collected at intake and 6 months later. Family stress was measured with an 11-point “Distress Thermometer” ranging from 0 (no distress) to 10 (extreme distress) adapted from a tool primarily used for cancer patients. 19 Protective factors were measured with several previously validated scales including the Family Functioning and Resiliency Scale (five 7-point likert items from never (1) to always (7) with sum scores ranging from 5 to 35), the Social Support Scale (three 7-point likert items from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) with sum scores ranging from 3 to 21), and a Knowledge of Parenting Scale (five 7-point likert items from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) with sum scores ranging from 5 to 35).20,21

To assess for factors associated with completion of goals, the following independent and dependent variables were defined:

Independent variables included demographics (language, race/ethnicity), the type (SDOH, maternal stress/depression, or intimate partner violence) and number of reported needs either from the universal screens or disclosed directly to healthcare providers or CHWs, levels of engagement (binary variable with inability to contact or refusal of services coded as 0, and ability to contact and acceptance of services coded as 1), use of warm handoff (yes/no) and program duration (brief vs full).

The dependent variable used as a proxy for completion of goals was “loop closure.” A loop was opened when a patient was referred for a service and considered closed once the EC-CHWs had confirmation from the referral site and/or family of successful engagement with the service. Proportions of closed loops to open loops was used as the main dependent variable.

Data Analysis

First, descriptive statistics were used to characterize the population in terms of demographics, and the variables described above.

Second, for families in the full intervention group, family stress level and protective factors were compared from intake to follow-up using the Mann-Whitney U test for related samples given the non-normal distribution in the small group (N = 26).

Third, to assess for factors associated with loop closure, several bivariate analyses were conducted using 1-way ANOVA including the independent variables described above.

Finally, a linear regression was used to assess for predictors of loop closure including demographics and variables that were either significant at the bivariate level or expected to be associated with loop closure such as SDOH, and stress or protective factors. Based on a large effect size of 0.35, 12 predictor variables, P-value .05 and 80% power, a sample size of 61 was calculated for the regression model.

Results

Between January 2019 through September 2020, 161 families were referred to the EC-CHW program, which is a 300% increase compared to referrals to the hospital’s traditional CHW program for children with special healthcare needs or chronic disease. Most of the referrals were from Pediatrics (N = 127, 78.3%) and the rest from Ob/Gyn (N = 34, 21.7%). Overall, 87% of families referred engaged in the program. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Early Childhood-CHW Program Participant Description.

| Participant descriptor | % (N) |

|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Black | 24.2% (39) |

| Hispanic | 8.1% (13) |

| Non-Hispanic | 16.1 (26) |

| White | 34.8% (56) |

| Hispanic | 31.7% (51) |

| Non-Hispanic | 3.1% (5) |

| Other, unknown or declined | 40.9% (66) |

| Hispanic | 24.2% (39) |

| Non-Hispanic | 6.3%(10) |

| Langage | |

| English | 46.6% (75) |

| Spanish | 44.7% (72) |

| Other | 8.7% (14) |

| Gender (child) | |

| Female | 43.3% (55) |

| Male | 56.7% (72) |

| Median age | |

| Pediatrics (months) | 25 (IQR 4.25-39.75) |

| Ob/Gyn (years) | 26 (IQR 19-29) |

| Referral source | |

| Pediatrics | 78.3% (127) |

| Attending | 24% |

| Resident | 17% |

| Psychologist | 25% |

| Social worker | 20% |

| Self-referred | 14% |

| OB/GYN | 21.7% (34) |

| Attending | 100% |

Almost 50% of cases screened positive for at least 1 SDOH on the hospital’s universal screen, and an additional ~10% were newly disclosed during intake with the CHW. The most common social need reported was food insecurity (25.5%), followed by housing insecurity (14.3%). Many of the referred families also reported potential mental health needs such as maternal stress/depression and isolation (21.1%).

Of the 161 referrals, 54.7% were for brief interventions. Of those enrolled in full interventions, the median time spent in the program was 4 months (IQR 2-7). Home and field visits were offered but only 38.8% accepted, most commonly for accompaniment to services such as Early Intervention (EI) evaluations. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Early Childhood-CHW Program Characteristics.

| Characteristic | % (N) |

|---|---|

| Level of involvement | |

| Full program | 45.3% (73) |

| Brief intervention | 54.7% (88) |

| Reason for referral | |

| Child development or behavior concern | 48.8% (62) |

| Maternal stress and isolation | 21.1% (34) |

| Positive for at least 1 SDOH (food insecurity, housing insecurity, and safety needs) on universal clinic administered screen | 47.8% (77) |

| At least 1 SDOH reported EITHER on universal screen or directly to CHW on intake | 57.1% (92) |

| Type of service received | |

| Referral to CBO partner (NMPP) | 37.8% (45) |

| Referral to CBO non-partner | 18.6% (30) |

| Linkage to EI/CPSE and headstart | 59.1% (79) |

| Linkage to food pantry and SNAP/WIC | 25.1% (41) |

| Linkage to housing, transportation, and job assistance | 14.3% (23) |

| Linkage to legal services | 11.8% (19) |

| Time spent in program (median # months) | 4.0 (IQR 2.0-7.0) |

| Cases with at least 1 loop closure | 84.5% (136) |

| Didn’t engage | 13.0% (21) |

Abbreviation: CBO, Community Based Organization.

Improvements in psychosocial wellbeing

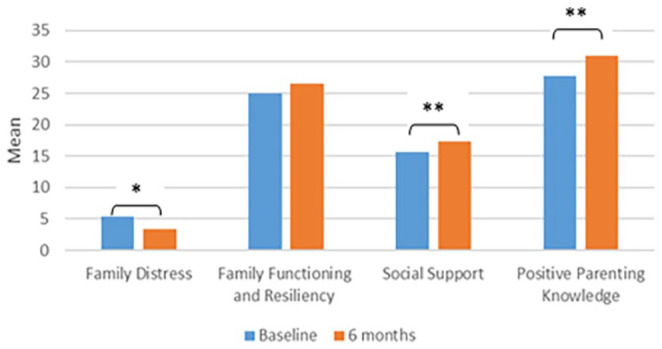

Social Support Scores (baseline mean 15.71 out of 21 (SD = 5.25)) and Positive Parenting Knowledge Scores (baseline mean 27.77 out of 35 (SD = 4.72)) both increased significantly for families between intake and follow-up (P = .22 and .019, respectively). The parent distress thermometer (baseline mean 5.37 out of 10 (SD = 4.58)) moved downward in direction (less stress over time), and Family Functioning and Resiliency (baseline mean 24.98 out of 35 (SD = 7.41)) improved over time, however these results did not reach statistical significance. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Family psycho-social stress and protective factors (baseline to after program involvement, N = 26).

*P = .07.

**Social Support Scores (u = 213, P = .022, effect size, r = .21). Positive Parenting Knowledge Scores (u = 182.p59, P = .019, effect size, r = .22).

Factors associated with completion of goals

Of all 161 families referred, a little more than half (59.5%, N = 96) were referred for only 1 type of service, and the maximum number of loops opened by any case was 6. Most families (73.9%, N = 119) had all their loops closed, 87% (N = 140) had at least 1 of their opened loops closed, and only a small minority of cases did not close any loops; 9.6% (N = 13).

There were no significant associations found at the bivariate level between demographic variables including language or race/ethnicity and the proportion of loops closed. There were also no significant associations between referral source or use of warm handoff, and the proportion of loops closed. The proportion of loops closed was however, significantly associated at the bi-variate level with maternal depression (P = .011) and full (vs brief) programmatic involvement (P = .042). Families who were positive for maternal depression and families who participated in the full program demonstrated higher proportions of loops closed.

The linear regression model inputs, including demographics, maternal stress/depression, SDOH, family stress, and protective factors and level of involvement in the program (brief vs full) explained 25.2% (R2 = .252) of the variance in loop closures and was significant at the 5% level of significance (P = .017). The model itself was moderately correlated to loop closures (R = .502). Maternal depression (P = .033) was the only independent variable significantly associated with programmatic success after controlling for all other covariates. Higher maternal depression was associated with higher loop closures. See Table 3.

Table 3.

Regression Analysis: Factors Associated With Loop Closure (Outcome Variable).

| Model variables | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard error | β | t | ||

| Demographics | |||||

| Child’s gender | 0.001 | 0.003 | .048 | 0.260 | .795 |

| Child’s age (in months) | 0.001 | 0.001 | .219 | 1.158 | .250 |

| Language | 0.027 | 0.058 | .046 | 0.470 | .640 |

| Race | 0.002 | 0.002 | .144 | 0.932 | .354 |

| Ethnicity | 0.000 | 0.003 | .009 | 0.058 | .954 |

| Variables initially significant at bivariate level | |||||

| Maternal depression | 0.162 | 0.078 | .205 | 2.062 | .033 |

| Level of involvement (full vs brief) | 0.037 | 0.079 | .050 | 0.466 | .642 |

| Other variables not significant at bivariate level but included in model | |||||

| Caregiver stress | −0.003 | 0.003 | −.360 | −0.879 | .382 |

| Reported social determinant of health | 0.058 | 0.050 | .121 | 1.164 | .247 |

| Family resiliency | −0.001 | 0.011 | −.117 | −0.111 | .912 |

| Family social support | 0.004 | 0.012 | .415 | 0.327 | .745 |

| Caregiver knowledge of parenting | −0.003 | 0.015 | −.244 | −0.187 | .852 |

Dependent variable: Loop closure.

Discussion

The EC-CHW program filled a clinical care gap in addressing psychosocial needs in both Pediatric and Ob/Gyn primary care during the perinatal period. Results indicate that families receiving services from the EC-CHW had a decrease in psychosocial stress and an increase in protective factors, namely social support and knowledge of positive parenting. Studies have shown that positive parenting promotes healthy brain development for children through adolescence. 22 These findings may be related to the fact that EC-CHWs served not only as referral navigators assuring linkages to services, but also provided important psycho-education and other non-tangible support such as maternal support, which is important for families in the perinatal period. 23 There was a sharing of resources between the primary care clinic’s Pediatric and Ob/Gyn services, and the community based organization, moving from referral to co-management among partners, which also increased both expertise and capacity to help families.

The program’s aim of facilitating loop closures for engaged families was successfully met, with 90.3% of cases experiencing at least 1 loop closure, an infrequently reported outcome in similar studies, which report ranges of 63% to 82%.24 -26 Interestingly, maternal depression was significantly associated with completion of referrals and goals. Shame and stigma have been documented, and negatively associated with help-seeking behaviors in mothers experiencing maternal depression. 27 One possible explanation for our finding could be that our healthcare providers and the EC-CHW responded to maternal depression in a way that did not induce shame, but instead, focused on enhancing social supports and connection to services that prioritized maternal health and well-being and addressed potential root causes of maternal depression such as housing or food insecurity. The EC-CHW might have also been more proactive in the referral process for mothers with depressive symptoms compared to mothers who were less depressed.

Though not statistically associated with loop closures, nearly half (47.8%) of program participants screened positive for SDOH. It is well established that SDOH account for over 80% of modifiable factors of health in a population and that SDOH are in part responsible for the ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic disparities that exist in health care access and utilization in the United States. 28 Connecting families from marginalized backgrounds to comprehensive health services that address SDOH and helping families navigate early childhood social and emotional concerns is critical for improving the lifelong trajectories of young children and their families. CHW programs have been instrumental in the work to bridge this care gap as they act as trusted brokers between families, the medical system, and needed community resources.29,30

Limitations

This project was primarily intended as a clinical initiative that used multiple evaluative methods, as opposed to a research study with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. This led to a significant amount of missing data. A relatively modest number of families with prolonged programmatic involvement had data on stress and protective factors to compare over time, and this might introduce biases inherent to those families who are more engaged. Program success was also measured with a loop closure variable that was created by the authors. This measure may not fully capture the extent to which families did or did not benefit from the program. Other measures of success and qualitative measures obtained directly from families are worth exploring in future studies. Finally, we do not have data on loops closed for families who were not referred to this program or other control data that would help clarify whether findings were related to our intervention.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the potential need for, and impact of an EC-CHW program in addressing psychosocial needs in the perinatal period. By adapting an existing CHW program to provide prevention efforts, and serve patients and families without chronic medical conditions, the model enhanced a medical home to meet a range of family’s health needs and address systemic barriers faced by minoritized populations. Engagement remained high and families in the program showed significant improvement in measured protective factors as well as a high proportion of loop closures, especially for families effected by maternal depression.

Acknowledgments

NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital Ambulatory Care Network, Northern Manhattan Perinatal Partnership, United Hospital Fund Partnerships for Early Childhood Development

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by EBJ, SM, AM, PP, and KM. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SM, EBJ, and MH. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was funded in part by the United Hospital Fund’s Partnerships for Early Childhood Development (PECD) 2016-2018. The work is also supported by the NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY.

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by the Colubia University Irving Medical Center Institutional Review Board, Protocol #AAAP1607.

ORCID iD: Evelyn Berger-Jenkins  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7014-3416

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7014-3416

References

- 1. Blair C, Raver CC. Poverty, stress, and brain development: new directions for prevention and intervention. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(3):S30-S36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bellis MA, Hughes K, Ford K, Rodriguez GR, Sethi D, Passmore J. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North America: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(10):e517-e528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS, et al.; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care, and Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e232-e246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sia C, Tonniges TF, Osterhus E, Taba S. History of the medical home concept. Pediatrics. 2004;113(Supplement_4):1473-1478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Francis L, DePriest K, Wilson M, Gross D. Child poverty, toxic stress, and social determinants of health: screening and care coordination. Online J Issues Nurs. 2018;23(3):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Flower K, Earls M, Nagy B, Janies K, Massie S, Bassewitz J. I-SCRN: a quality improvement collaborative to increase early childhood screening, referral and follow up in pediatric primary care practices. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2_MeetingAbstract):72. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garg A, Toy S, Tripodis Y, Silverstein M, Freeman E. Addressing social determinants of health at well child care visits: a cluster RCT. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):e296-e304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nayak SS, Carpenito T, Zamechek L, et al. Predictors of service utilization of young children and families enrolled in a pediatric primary care mental health promotion and prevention program. Community Mental Health J. 2022;58(6):1191-1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu IH, Bathje GJ, Kalibatseva Z, Sung D, Leong FT, Collins-Eaglin J. Stigma, mental health, and counseling service use: a person-centered approach to mental health stigma profiles. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(4):490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Benuto LT, Gonzalez F, Reinosa-Segovia F, Duckworth M. Mental health literacy, stigma, and behavioral health service use: the case of Latinx and non-Latinx whites. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2019;6:1122-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krist AH, Davidson KW, Ngo-Metzger Q. What evidence do we need before recommending routine screening for social determinants of health? Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(10):602-605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Costich MA, Peretz PJ, Davis JA, Stockwell MS, Matiz LA. Impact of a community health worker program to support caregivers of children with special health care needs and address social determinants of health. Clin Pediatr. 2019;58(11-12):1315-1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hudson DL. How Racism Has Shaped the Health of Black Americans and What to Do About It. American Public Health Association. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spencer MS, Hawkins J, Espitia NR, et al. Influence of a community health worker intervention on mental health outcomes among low-income Latino and African American adults with type 2 diabetes. Race Soc Problems. 2013;5:137-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. DiNapoli TP. Office of the New York State Comptroller. 2015. Accessed November 22, 2023. https://www.osc.state.ny.us/

- 16. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. NYC Health. 2015. Accessed November 22, 2023. http://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/index.page.

- 17. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Community Health Profiles. 2015. Accessed November 22, 2023. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/data/data-publications/profiles.page.

- 18. Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York. Early Inequities: How Underfunding Early Intervention Leaves Low-Income Children of Color Behind. 2019. Accessed November 22, 2023. https://s3.amazonaws.com/media.cccnewyork.org/2020/12/EI-Report-FINAL-12-4-19.pdf

- 19. Cutillo A, O’Hea E, Person S, Lessard D, Harralson T, Boudreaux E. NCCN distress thermometer: cut off points and clinical utility. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2017;44(3):329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. FRIENDS National Center for Community-Based Child Abuse Prevention. The Protective Factors Survey User’s Manual. 2011. Accessed November 22, 2023.https://friendsnrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/PFS-Overview.pdf

- 21. Counts JM, Buffington ES, Chang-Rios K, Rasmussen HN, Preacher KJ. The development and validation of the protective factors survey: a self-report measure of protective factors against child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 2010;34(10):762-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Whittle S, Simmons JG, Dennison M, et al. Positive parenting predicts the development of adolescent brain structure: a longitudinal study. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2014;8:7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mundorf C, Shankar A, Moran T, et al. Reducing the risk of postpartum depression in a low-income community through a community health worker intervention. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22:520-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Butler ED, Morgan AU, Kangovi S. Screening for unmet social needs: patient engagement or alienation? NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. 2020;1(4):1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boyum S, Kreuter MW, McQueen A, Thompson T, Greer R. Getting help from 2-1-1: a statewide study of referral outcomes. J Soc Serv Res. 2016;42(3):402-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fleegler EW, Lieu TA, Wise PH, Muret-Wagstaff S. Families’ health-related social problems and missed referral opportunities. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):e1332-e13341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dunford E, Granger C. Maternal guilt and shame: relationship to postnatal depression and attitudes towards help-seeking. J Child Fam Stud. 2017;26:1692-1701. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thornton RL, Glover CM, Cené CW, Glik DC, Henderson JA, Williams DR. Evaluating strategies for reducing health disparities by addressing the social determinants of health. Health Aff. 2016;35(8):1416-1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Islam N, Shapiro E, Wyatt L, et al. Evaluating community health workers’ attributes, roles, and pathways of action in immigrant communities. Prevent Med. 2017;103:1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Matiz LA, Peretz PJ, Jacotin PG, Cruz C, Ramirez-Diaz E, Nieto AR. The impact of integrating community health workers into the patient-centered medical home. J Prim Care Community Health. 2014;5(4):271-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]