The United States is facing a mental health crisis, as more than one in five US adults live with a mental illness (57.8 million in 2021).1 The COVID-19 pandemic (March 11, 2020‒May 5, 2023) has been linked with increases in poor mental health outcomes in not only the general population but also among workers.2 The social and economic disruptions experienced by many people amplified and compressed mental health morbidity. Lifetime estimates of the prevalence of poor mental health outcomes were seen in the early, acute phases of the pandemic; for example, in June 2020, 40% of US adults reported struggling with mental health or substance use.3

While working in health occupations has always been challenging, our entire system of providing health care has been under extreme duress for the past three years, and in some cases, it has been pushed near the breaking point. Difficult working conditions associated with health occupations, including long work hours and shiftwork, intense physical and emotional labor, exposure to human suffering and death, and risk of exposure to disease and violence, have all been magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic.4 Health workers including not only frontline health care workers such as nurses and physicians but also public health workers, emergency medical service (EMS) first responders, mental health workers, long-term care workers, and others in many supporting roles, have been especially impacted by increased poor mental health outcomes.

During the first year of the pandemic, across 65 studies involving 97 333 health workers, 22% reported moderate depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).5 One study, which surveyed more than 1100 health workers from June through September 2020, found that 93% reported they were experiencing stress, 86% reported anxiety, 76% reported exhaustion and burnout, and 41% reported loneliness.6 Similarly, a survey of 26 174 public health workers in 2021 revealed that 53% were experiencing symptoms of at least one mental health condition.2 The mental health challenges have been experienced by both clinicians and those in nonclinical support roles, but fewer assistance resources have been available to lower-wage health workers. In 2022, only 22% of health workers in California reported adequate emotional support. Janitorial, food service, supply, and other support staff reported the lowest support (17%) among represented job types.7

An urgent and related challenge facing the US health workforce is burnout. Burnout is driving and magnifying workforce shortages among many health occupations. In 2019, societal costs of health worker burnout were estimated to be $4.6 billion,8 and these costs are expected to increase given the rates of health workers leaving the workforce. A cross-sectional survey of 43 000 health care workers conducted during the first several months of the COVID-19 pandemic (April to December 2020) reported that 49.9% experienced burnout and 29% intended to leave their position. Both burnout and intent to leave were highest among nurses with rates of 56% and 41%, respectively.9 This loss of workforce has persisted over the course of the pandemic. A November 2022 survey of 12 581 nurses revealed that 19% intended to leave their current position in the next six months, and 27% were considering leaving.10

The public health workforce has also been experiencing alarming rates of workforce loss in an already understaffed infrastructure. According to data from the 2021 Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey (a nationally representative survey of individual state and local governmental public health agency workers), approximately 40% of the workforce intended to leave their jobs within the next five years.11 At the same time, it has been estimated that approximately 80 000 additional full-time staff members are needed throughout the nation’s public health agencies to meet current needs for public health services (https://bit.ly/3RxrdtF).

GOVERNMENT ACTIONS

It has become increasingly evident that mental health and well-being is an important aspect of public health, and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has prioritized the implementation of approaches to support positive mental health outcomes across multiple domains, including in working populations. CDC also recognizes work as a social determinant of health, as it affects a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks. CDC has developed a behavioral health coordination unit to coordinate agency strategy and priorities in mental health around ongoing programs focused on youth mental health, coping with stress, cultural and social connectedness, and pandemic-related mental health impacts.12 For example, the CDC developed the How Right Now campaign to promote and strengthen emotional well-being and resilience, largely in response to the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic across the US population, including elevated rates of stress, depression, anxiety, PTSD, suicidal behavior, and substance use disorders.13

In his first State of the Union Address in 2022, President Biden announced a strategy to address our national mental health crisis. The President’s 2023 State of the Union Address again called for urgent action to tackle the current mental health crisis, and one of the key activities called for was provision of support for the mental health of the health workforce.14 On May 18, 2023, President Biden announced additional critical actions to advance his mental health plan to transform how mental health is understood, accessed, treated, and integrated both in and out of health care settings, and he outlined new strategies for addressing the nation’s mental health crisis.15

Through the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) at CDC received $20 million to carry out a national evidence-based education and awareness campaign to safeguard and improve the mental health of health workers, which was critically needed.16 With this commentary, CDC is calling for increased national attention and broad-based action to urgently and sustainably improve the culture and climate of the workplaces engaged in health across the nation. The mental health of the nation’s health sector will influence every American; preventing and addressing mental health concerns among health workers benefits them directly, and it also improves their ability to care for us all.

Much of the recent focus on workplace mental health has led to new resources and supports, including training interventions to support and increase employee resilience (e.g., Healthy Workforce Resiliency Awards).17 While these efforts are critically important, building individual-level skills alone is insufficient to compensate for unsupportive workplace factors, and focusing on how to prevent these issues is needed for sustainability. In a 2022 survey by McKinsey Health Institute, employees with high adaptability were 60% more likely to report intent to leave their organization if they experienced high levels of toxic behavior at work (e.g., unfair or demeaning treatment, noninclusive behavior, abusive management, or unethical behavior from leaders or coworkers) than those employees with lower adaptability. These authors conclude that “relying on improving employee adaptability without addressing broader workplace factors puts employers at an even higher risk of losing some of its most resilient, adaptable employees.”18

NIOSH APPROACH TO WORKPLACE MENTAL HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

NIOSH is a research institute within CDC focused on the study of worker safety and health and empowering employers and workers to create safe and healthy workplaces. For more than a decade, the NIOSH Total Worker Health Program has focused on the overall health and well-being of workers by specifically looking at the connection between their work, safety, and overall health and well-being. The Total Worker Health approach is defined as policies, programs, and practices that integrate protection from work-related safety and health hazards with promotion of injury and illness–prevention efforts to advance worker well-being.19 In Fall 2021, NIOSH launched a Total Worker Health Center of Excellence dedicated to workplace mental health.20 This new center joins nine other funded academic centers researching the most effective ways to improve the overall well-being of workers.

As the future of work evolves and new challenges for working Americans emerge, NIOSH predicts that increased attention to the mental health of workers and more robust controls of psychosocial hazards (such as excessive job demands, low control over work, and harmful supervisory practices) will be imperative. Organizations must prioritize creating and promoting a more supportive and healthier workplace culture if they want to retain a thriving workforce.

NIOSH HEALTH WORKER MENTAL HEALTH INITIATIVE

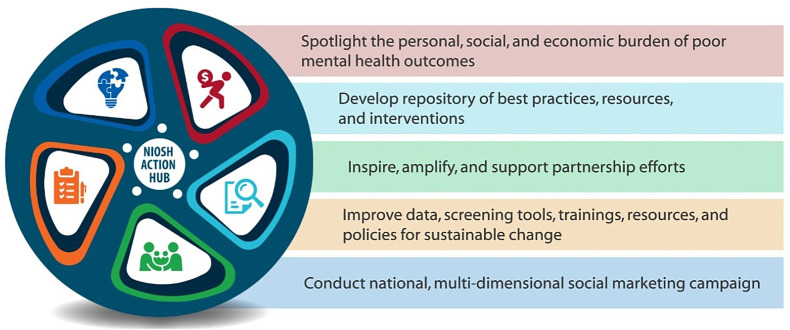

CDC and NIOSH were funded by Congress in 2021 to develop and conduct a national evidence-based education and awareness campaign to safeguard and improve the mental health of health workers. The main charge for this effort was to promote primary prevention of mental health conditions, encourage secondary and tertiary prevention by encouraging health care professionals to seek support and treatment of their own mental health, and help such professionals identify risk factors in themselves and others and respond to those risks. In 2021, NIOSH established a five-part plan to raise awareness of mental health concerns and suicide risk among health workers and to urge employers to build a sustainable infrastructure for future generations of health care workers (Figure 1). The following elements make up the five-part plan:

-

1.

Understand and spotlight the personal, social, and economic burdens of difficult working conditions and their toll on health workers when it comes to poor mental health outcomes.

-

2.

Assimilate the best evidence, develop a repository of best practices, resources, and interventions

-

3.

Leverage partners to reach and inspire specific audiences and amplify our message.

-

4.

Identify and adapt tools; improve data, surveillance, and screenings; grade the evidence around current interventions; develop trainings and resources; and, ideally, motivate game-changing policies.

-

5.

Generate awareness by conducting a national multidimensional social marketing campaign to stimulate interest in good mental health, lower stigma, normalize the conversation around mental health, lower barriers for care-seeking, and bring a positive message that people can get better, lead more fulfilling lives, and remain in the profession they love.

FIGURE 1—

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health’s Health Worker Mental Health Initiative Objectives

Several efforts from the five objectives are reflected in this special issue. In particular, a systematic review of mental health interventions in health care settings highlights the lack of system-level, primary prevention interventions and indicates that the majority of the literature reflects individual, secondary, or tertiary interventions. Other articles describe updated surveillance data on mental health outcomes among health workers, organization-level interventions to improve mental health outcomes, and efforts partners are engaged in to support mental health and well-being among health workers.

The social marketing campaign is designed to reach decision-makers within hospitals and hospital systems (C-suite executives). These leaders have the unique ability to leverage their high-ranking positions to impact mental health policies and practices at the organizational level. The campaign will develop sound evidence-informed resources to help hospital leaders think differently about how to use their existing resources, improve current processes, and establish new policies at their hospital. For example, in recognition of Mental Health Action Day on May 18, NIOSH published a fact sheet and a joint statement with the Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation about removing overly invasive mental health questions from hospital credentialing applications.21,22 The campaign will also include messages for leaders to provide to their own workers directly, allowing for hyper-local context and customization for maximum effectiveness. In our message testing, we learned hospital leaders genuinely care about their staff and want to address barriers to their workforce’s well-being. They need the resources and guidance to implement proven solutions at their hospital that the campaign will provide. Message testing also revealed health care workers want hospital leaders to address challenges at the systems level and lead by example to foster well-being in the workplace. The full campaign will launch in Fall 2023 and be evaluated through a cross-sectional survey of health care workers and hospital leaders from partner organizations.

Additional efforts are underway to assist public health workers who also saw consistent challenges and working conditions worsen because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many reported experiencing high levels of fatigue, strain, stress, loss, distrust, public anger and unrest, and threats of violence, as well as personal loss and grief.2 NIOSH has developed burnout prevention training specifically for supervisors of public health workers.23 Improving workplace policies and practices is the best way to address burnout. While individual-level solutions like self-care and resilience training may help, making organizational changes is necessary. For this reason, managers and supervisors must take action to address this issue. This self-paced online course offers continuing education credit at no cost. It provides an overview of burnout and its consequences in public health, discusses how resource and demand imbalances lead to burnout, and provides strategies to prioritize employee health and well-being.

Those who have partnered with us along the way are critical to the reach and influence of these efforts. Since the beginning, NIOSH has leveraged well-established partner connections and forged new ones. These partnerships helped us frame, steer, and amplify our efforts. Early on, NIOSH connected with other federal entities who were also working on the mental health crisis, including CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, the US Surgeon General, and the Health Resources and Services Administration. The Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation; the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention; the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; the Service Employees International Union; the American Hospital Association; and many others have contributed to the effort.

CONCLUSION

The journey to safeguarding and improving the mental health of those who safeguard the health of us all is vital. CDC and NIOSH are committed to providing the most accurate, timely, and compelling science to drive this change. The nation is well aware of the problems at hand, and it is clear the time for action is overdue. With dedicated partners and organizational-level commitments, we aim to improve the health of these workers and, in turn, all Americans for generations to come. Our ultimate success will depend upon those who lead health care‒providing organizations. We urge you to join us on this critically important journey.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank L. Casey Chosewood, Thomas Cunningham, and Christina Spring for their scientific support of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Mental Health Initiative described in this article.

Note. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. January 2023. . Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2021-nsduh-annual-national-report . Accessed May 17, 2023.

- 2.Bryant-Genevier J , Rao CY , Lopes-Cardozo B , et al. Symptoms of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation among state, tribal, local, and territorial public health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, March–April 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(48):1680–1685. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7026e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czeisler MÉ , Lane RI , Petrosky E , et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24‒30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; 69(32):1049–1057. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Academy of Medicine. National Plan for Health Workforce Well-Being. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2022. 10.17226/26744 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y , Scherer N , Felix L , et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0246454. 10.1371/journal.pone.0246454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mental Health America . Survey: The mental health of healthcare workers in COVID-19. 2021. . Available at: https://mhanational.org/mental-health-healthcare-workers-covid-19 . Accessed December 16, 2023.

- 7.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mental Health America . The mental health of healthcare workers: a survey of the concerns and needs of frontline workers as the pandemic entered its third year. 2022. . Available at: https://mhanational.org/sites/default/files/reports/Mental-Health-Healthcare-Workers.pdf . Accessed December 16, 2023.

- 9.Rotenstein LS , Brown R , Sinsky C , et al. The association of work overload with burnout and intent to leave the job across the healthcare workforce during COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(8): 1920–1927. 10.1007/s11606-023-08153-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. American Nurses Association . Three-year annual assessment survey: nurses need increased support from their employer. 2023. . Available at: https://bit.ly/3v1bmvN . Accessed December 16, 2023.

- 11.Hare Bork R , Robins M , Schaffer K , et al. Workplace perceptions and experiences related to COVID-19 response efforts among public health workers—Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey, United States, September 2021‒January 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(29):920–924. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7129a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Mental health. April 28, 2023. . Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/index.htm . Accessed June 6, 2023.

- 13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . How Right Now. March 7, 2023. . Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/howrightnow . Accessed May 17, 2023.

- 14. White House . Fact sheet: In State of the Union, President Biden to outline vision to advance progress on unity agenda in year ahead. February 7, 2023. . Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/02/07/fact-sheet-in-state-of-the-union-president-biden-to-outline-vision-to-advance-progress-on-unity-agenda-in-year-ahead . Accessed December 16, 2023.

- 15. White House . Fact sheet: Biden-Harris administration announces new actions to tackle nation’s mental health crisis. May 18, 2023. . Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/05/18/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-announces-new-actions-to-tackle-nations-mental-health-crisis . Accessed December 16, 2023.

- 16. American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 , HR 1319 ( 2021. ).

- 17. Health Resources & Services Administration . Health workforce resiliency awards. January 2022. . Available at: https://bhw.hrsa.gov/funding/health-workforce-resiliency-awards . Accessed May 17, 2023.

- 18. Brassey J , Coe E , Dewhurst M , et al. Addressing employee burnout: are you solving the right problem? McKinsey Health Institute. 2022. . Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com.cn/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MHI-ariticle_addressing-employee-burnout-are-you-solving-the-right-problem-vf.pdf . Accessed December 16, 2023.

- 19. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health . Fundamentals of total worker health approaches: essential elements for advancing worker safety, health, and well-being. NIOSH Office for Total Worker Health. 2016. . Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2017-112/pdfs/2017_112.pdf?id=10.26616/NIOSHPUB2017112 . Accessed December 16, 2023.

- 20. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health . NIOSH Centers of Excellence for Total Worker Health. August 4, 2021. . Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/twh/centers.html . Accessed May 17, 2023.

- 21. Office for Total Worker Health, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health . Healthcare Worker Wellbeing: Making the System Work for Healthcare Workers. 2023. . Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2023-136/default.html . Accessed December 16, 2023.

- 22. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health . Statement on removing intrusive mental health questions from hospital credentialing applications from the Dr. Lorna Breen Heroes’ Foundation and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. May 18, 2023. . Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/updates/upd-05-18-23.html . Accessed July 17, 2023.

- 23. Office for Total Worker Health, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health . Understanding and preventing burnout among public health workers: guidance for public health leaders. March 8, 2023. . Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/learning/publichealthburnoutprevention/default.html . Accessed May 17, 2023.