Abstract

Here we present complete genome sequences, including a comparative analysis, of 103 isolates of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) representing all seven serotypes and including the first complete sequences of the SAT1 and SAT3 genomes. The data reveal novel highly conserved genomic regions, indicating functional constraints for variability as well as novel viral genomic motifs with likely biological relevance. Previously undescribed invariant motifs were identified in the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTR), as was tolerance for insertions/deletions in the 5′ UTR. Fifty-eight percent of the amino acids encoded by FMDV isolates are invariant, suggesting that these residues are critical for virus biology. Novel, conserved sequence motifs with likely functional significance were identified within proteins Lpro, 1B, 1D, and 3C. An analysis of the complete FMDV genomes indicated phylogenetic incongruities between different genomic regions which were suggestive of interserotypic recombination. Additionally, a novel SAT virus lineage containing nonstructural protein-encoding regions distinct from other SAT and Euroasiatic lineages was identified. Insights into viral RNA sequence conservation and variability and genetic diversity in nature will likely impact our understanding of FMDV infections, host range, and transmission.

Foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) is an acute, systemic disease of domestic and wild cloven-hooved animal species and is caused by Foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV), the prototype member of the genus Aphthovirus of the family Picornaviridae. FMDV occurs as seven distinct serotypes (Euroasiatic serotypes A, O, C, and Asia1 and South African Territories [SAT] serotypes SAT1, SAT2, and SAT3) and multiple subtypes reflecting significant genetic variability. The highly contagious nature of FMDV and the associated productivity losses make it a primary animal health concern worldwide. Effective vaccines and stringent control measures have enabled FMD eradication in most developed countries, which maintain unvaccinated, seronegative herds in compliance with strict international trade policies. However, the disease remains enzootic in many regions of the world, posing a serious problem for commercial trade with FMD-free countries.

FMDV is a small nonenveloped virus with a pseudo T=3 icosahedral capsid made up of 60 copies each of four structural proteins. The capsid surrounds an 8.4-kilobase, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome which is covalently bound at its 5′ end to the small viral protein 3B (or VPg) and is polyadenylated at its 3′ end. Upon virus entry into a cell, the viral genome is rapidly translated into a polyprotein which is co- and posttranslationally cleaved by viral proteinases into several partially cleaved, likely functional, intermediates and ultimately into 12 mature proteins (87, 97).

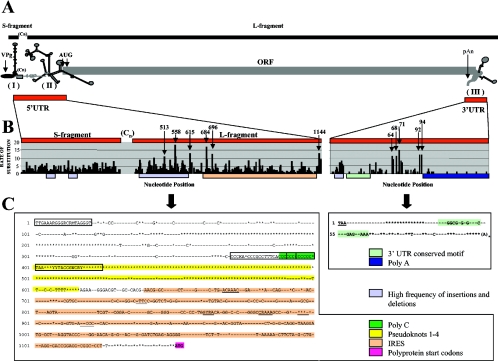

The FMDV genome organization is similar to that of other picornaviruses, including a large single open reading frame (ORF) flanked by highly structured 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (5′ UTR and 3′ UTR, respectively) (Fig. 1A). The 5′ UTR consists of, from the 5′ end, a 350- to 380-nucleotide (nt) “short” (S) fragment, a 100- to 420-nt poly(C) tract (90% C), and the approximately 700-nt 5′ terminus of the genomic “long” (L) fragment, which contains three or four tandemly repeated pseudoknots, a stem-loop cis-acting replication element (cre), and a type II internal ribosome entry site (IRES) (69). The FMDV 5′ UTR plays important roles in cap-independent translation initiation of the viral polyprotein and in viral genome replication (64). The 3′ UTR is about 90 nt long and is thought to contain cis-acting elements required for efficient genome replication (4).

FIG. 1.

FMDV UTR variability. (A) FMDV S and L genomic fragments showing the locations and predicted secondary structures of UTRs. Cn, poly(C) tract; AUG, start codons; pAn, poly(A); I, II, and III, S fragment, IRES, and 3′ UTR, respectively. (B) Rates of substitution per nt between positions 1 and 1218 and positions 8277 and 8441 in a genomic ClustalW alignment. Arrows with numbers indicate positions with high rates of nt substitution. (C) 5′ UTR nt conservation between positions 1 and 1153 for the 103 FMDV isolates examined in this study. Motifs previously defined as conserved between picornavirus IRESs are underlined. Boxes indicate primers used for amplification. Asterisks indicate nt positions tolerant to insertions/deletions in two or more isolates. (D) Nucleotide conservation within S fragment (I), IRES (II), and 3′ UTR (III) predicted secondary structures. Arrows indicate regions used for PCR amplification. UTR regions from the isolate C5Argentina/69 were used to generate secondary structure predictions and plots with mfold and Squiggles. Black circles indicate invariant nt among the 103 isolates presented here; gray circles represent nt that are conserved in at least 100 of 103 isolates (96%); gray shading indicates residues comprising previously described motifs. Nucleotide position numbers correspond to the consensus sequence generated by a ClustalW alignment of the 103 isolates.

The four capsid proteins, 1A, 1B, 1C, and 1D (also known as VP4, VP2, VP3, and VP1, respectively), are encoded by the N-terminal half of the ORF, and with the exception of 1A, which is excluded from the virion surface, are involved in antigenicity and binding to a subset of RGD-dependent integrins and heparan sulfate proteoglycan receptors on the cell surface (reviewed in reference 45). Nonstructural proteins represent about two-thirds of the ORF-encoded proteins and include Lpro, 2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3Cpro, and 3Dpol (93). FMDV polyprotein processing is mediated by Lpro, 3Cpro, and 2A. Lpro is a papain-like protease that, in addition to excising itself from the polyprotein, cleaves the cellular translation initiation factor eIF4G, resulting in a shutoff of host cap-dependent translation (65). 3Cpro, a member of the trypsin family of serine proteinases, performs all but three of the cleavages leading to mature viral proteins and also cleaves host cell proteins (111). FMDV 2A mediates autocleavage at its C terminus, apparently by inducing a ribosomal skip during polyprotein synthesis (19, 20). Although the functions of the FMDV 2B and 2C proteins are unknown, preliminary work suggests that, similar to those of other picornaviruses, they localize to endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-derived vesicles, the sites of viral genome replication (106). 3A is thought to be a multifunctional integral membrane protein that enhances viral RNA synthesis by 3Dpol and stimulates cleavage of the 3CD precursor (91). FMDV encodes three nonidentical copies of genome-linked 3B, a protein required for viral RNA replication (26). The 3D gene encodes the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and it and 3A colocalize with ER membrane-associated replication complexes (80, 92).

Despite a basic understanding of many aspects of picornaviral biology, much information regarding FMDV UTR, protein, and protein precursor functions and roles in virulence, host range, and virus transmission remains poorly understood. Comparative genomic analysis of a large number of FMDV genomes may allow the identification of highly conserved regulatory or coding regions which are critical for aspects of virus biology. To date, the few comparative analyses of full-length FMDV genomes have relied on intratypic (serotype O) or intertypic (serotypes O, A, and C) comparisons of a small number of isolates and serotypes (70, 86). In addition, complete genomic sequences of some serotypes are not available (SAT1 and SAT3) or, for others, only represent highly cell culture-adapted isolates (serotypes A and C). Studies involving large numbers of virus isolates have largely focused on genomic regions encoding structural proteins associated with serotype specificity for phylogenetic purposes (reviewed in reference 55).

For this work, we obtained and analyzed 103 complete genome sequences representing all FMDV serotypes, including the previously unavailable SAT1 and SAT3 genomes. Our analyses identified novel highly conserved genomic regions indicating functional constraints for variability, novel viral genomic motifs with likely biological relevance, and previously undescribed virus lineages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

FMDV isolates.

One hundred three FMDV isolates were obtained from the Animal Plant Health Inspection Service, United States Department of Agriculture (Table 1). Except for recent isolates from Argentina, the United Kingdom, and South Korea (2000-2001), most isolates belonged to the Animal Plant Health Inspection Service archive collection and represented a broad temporal and geographical distribution (Table 1). Although certain archive isolates have been adapted to guinea pigs or passaged in cell cultures, isolates obtained from their natural hosts were well represented. For some analyses, complete genome or whole polyprotein FMDV sequences currently available in GenBank release 141 were considered and included (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

FMDV sequences

| Sequence no.c | Isolate namea | Country, year of isolation | Passage historyb | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A25 Argentina/59 | Argentina, 1959 | GP, 1 LK | AY593769 |

| 2 | A Canefa 1/61 | Argentina, 1961 | BOV 2 LK | AY593789 |

| 3 | A24 Argentina/65 | Argentina, 1965 | BOV, 3 LK | AY593767 |

| 4 | A26 Argentina/66* | Argentina, 1966 | 8 GP | AY593770 |

| 5 | A Argentina/00 | Argentina, 2000 | BOV | AY593782 |

| 6 | A Argentina/01 Areco | Argentina, 2001 | BOV | AY593783 |

| 7 | A ARGp55/01 | Argentina, 2001 | BHK-21 passage 55 | AY593784 |

| 8 | A ARGp64/01 | Argentina, 2001 | BHK-21, passage 64 | AY593785 |

| 9 | A Trenquelauquen/01 | Argentina, 2001 | BOV | AY593786 |

| 10 | A General Lopez/01 | Argentina, 2001 | BOV | AY593790 |

| 11 | A Uruguay/01 | Uruguay, 2001 | BOV | AY593801 |

| 12 | A Uruguay/98 | Uruguay, 2001 | BHK-21 | AY593802 |

| 13 | A Bage/77* | Brazil, 1977 | 2 BTT | AY593787 |

| 14 | A Brazil/79 | Brazil, 1979 | 1 BHK-21, 1 IBRS-2 | AY593788 |

| 15 | A Venceslau/76 | Brazil, 1976 | 5 BHK-21, BTT | AY593803 |

| 16 | A13 Brazil /70 | Brazil, 1970 | 7 GP | AY593753 |

| 17 | A16 Belem/59 | Brazil, 1959 | BOV, 1 LK | AY593756 |

| 18 | A17 Aguarulbos/67 | Brazil, 1967 | 3 BOV, 3 LK | AY593757 |

| 19 | A24 Cruzeiro/55 | Brazil, 1955 | 5 BHK-21, 5 IBRS-2 | AY593768 |

| 20 | A Sabana/85 | Colombia, 1985 | 1 BTT, 1 BHK-21, 1 IBRS-2 | AY593794 |

| 21 | A27 Colombia/67 | Colombia, 1967 | 10 GP | AY593771 |

| 22 | A29 Peru/69 | Peru, 1969 | GP, 1 LK | AY593773 |

| 23 | A18 Zulia/67 | Venezuela, 1967 | 1 BK, 10 GP, 2 LK | AY593758 |

| 24 | A32 Venezuela/70 | Venezuela, 1970 | 1 BOV, LK | AY593775 |

| 25 | A10 Holland/42 | Holland, 1942 | 1 IBRS-2 | AY593751 |

| 26 | A12 Valle Strain 119* | Great Britain, 1932 | 77 BOV | AY593752 |

| 27 | A1 Bayern/Bavaria | Germany, 1971 | GP, 1 IBRS-2 | AY593759 |

| 28 | A3 Mecklenburg/68 | Germany, 1968 | 1 BOV, 1 LK | AY593776 |

| 29 | A5 Westerwald/51* | West Germany, 1951 | ET, BTT | AY593781 |

| 30 | A4 WG/42 | West Germany | 4 BTT, 4 BHK-21 | AY593777 |

| 31 | A4 WG/72 | West Germany, 1972 | 1 BOV, 1 LK | AY593779 |

| 32 | A5 Allier/60 | France, 1960 | 3 GP, 4 BT, 4 BHK-21 | AY593780 |

| 33 | A8 Parma/62 | Italy, 1962 | BOV, 1 LK | AY593792 |

| 34 | A4 Spain* | Spain | ET, 1 BTT | AY593778 |

| 35 | A2 Spain/69 | Spain, 1969 | 1 LK | AY593774 |

| 36 | A14 Spain/59 | Spain, 1959 | BOV, 1 LK | AY593754 |

| 37 | A Philippines/75 | Philippines, 1975 | 4 GP, 2 LK | AY593793 |

| 38 | A15 Thailand/60 | Thailand, 1960 | 1 BOV, 3 LK | AY593755 |

| 39 | A22 Turkey/65* | Turkey, 1965 | 2 BTT | AY593765 |

| 40 | A28 Turkey/72 | Turkey, 1972 | 1 LK | AY593772 |

| 41 | A20 USSR 1/64 | USSR, 1964 | 2 LK | AY593760 |

| 42 | A Iran/1/98 | Iran, 1998 | 1 BOV | AY593791 |

| 43 | A22 Iraq 24/64 | Iraq, 1964 | 4 BTT, 1 LK | AY593762 |

| 44 | A22 Iraq 26/64* | Iraq, 1964 | 3 BOV | AY593763 |

| 45 | A22 Iraq/70 | Iraq, 1970 | 2 LK | AY593764 |

| 46 | A21 Kenya/64 | Kenya, 1964 | 9 GP | AY593761 |

| 47 | A23 Kenya 6/65 | Kenya, 1965 | 2 LK | AY593766 |

| 48 | Asia 1 Leb 1/83* | Kfar Kela/Lebanon, 1983 | 2 PK, 2 BTT | AY593799 |

| 49 | Asia 1 Leb 2/83* | Lebanon, 1983 | 2 BOV | AY593800 |

| 50 | Asia 1 Leb 3/83* | Southern Lebanon, 1983 | 2 PK, 2 BTT | AY593798 |

| 51 | Asia 1/1 PAK/54 | Pakistan, 1954 | 6 BTT, 2 LK | AY593795 |

| 52 | Asia 1/2 ISRL 3/63 | Israel, 1963 | BOV, 7 GP | AY593796 |

| 53 | Asia 1/3 Kimron | Israel, 1963 | BOV, 9 GP | AY593797 |

| 54 | C Waldman strain 149* | Great Britain, 1970 | BTT | AY593810 |

| 55 | C1 Noville/65 | Switzerland, 1965 | 2 PI, BHK-21 | AY593804 |

| 56 | C1 Oberbayern/60* | Germany, 1960 | BHK-21 | AY593805 |

| 57 | C3 Indaial/71 | Brazil, 1971 | 2 BHK-21 | AY593806 |

| 58 | C3 Resende/55 | Brazil, 1955 | 1 LK | AY593807 |

| 59 | C4 Tierra del Fuego/66 | Tierra del Fuego, Argentina, 1966 | 1 LK | AY593808 |

| 60 | C5 Argentina/69 | Argentina, 1969 | 5 BHK-21, 5 GP | AY593809 |

| 61 | O Rey Iran/66 | Iran, 1966 | BTT, BK, 1 LK | AY593834 |

| 62 | O Uruguay/63 | Uruguay, 1963 | BK, 2 LK | AY593837 |

| 63 | O UK 2001* | United Kingdom, 2001 | BVF | AY593836 |

| 64 | O UK2001-ED | Plum Island, 2002 | 1 BHK-21 | AY593831 |

| 65 | O UK2001-FB | Plum Island, 2002 | 2 BHK-21 | AY593832 |

| 66 | O1 Argentina/65 | Argentina, 1965 | 2 BTT, 1 LK | AY593814 |

| 67 | O1 BFS18/67 | United Kingdom | 1 LK | AY593815 |

| 68 | O1 BFS46/67 | United Kingdom | 2 BHK-21 | AY593816 |

| 69 | O1 Brugge | Belgium, 1973 | 1 LK | AY593817 |

| 70 | O1 Campos/58 | Brazil, 1958 | 1 BTT | AY593818 |

| 71 | O1 Campos/94 | Plum Island | BHK-21 | AY593819 |

| 72 | O1 Canefa/64* | Argentina, 1964 | 2 BTT | AY593820 |

| 73 | O1 Caseros/67* | Argentina, 1967 | 4 BTT | AY593821 |

| 74 | O1 M11* | Unknown, 1953 | BTT | AY593822 |

| 75 | O1 Manisa/69* | Turkey, 1969 | BVF | AY593823 |

| 76 | O1 SKR/00* | S. Korea, 2000 | Swine epithelium | AY593824 |

| 77 | O1 Vallee/39* | Pirbright, 1953 | Bovine epithelium | AY593825 |

| 78 | O10 Philippines | Philippines/58 | 1 LK | AY593811 |

| 79 | O10 Philippines 2/58* | Philippines/58 | BTY, BK, BOV | AY593812 |

| 80 | O11 Indonesia/62 | Indonesia, 1962 | BTT, 2 LK | AY593813 |

| 81 | O2 Brescia/47 | Italy, 1947 | 1 LK | AY593826 |

| 82 | O3 Venezuela/71 | Venezuela, 1971 | BTT, 1 LK | AY593827 |

| 83 | O5 India/62* | India, 1962 | 1 BK, 1 BTT | AY593828 |

| 84 | O6 Pirbright/65 | United Kingdom /65 | 4 GP | AY593829 |

| 85 | O7 Poland/59 | Poland, 1959 | 1 LK | AY593830 |

| 86 | O Taiwan/97 | Taiwan, 1997 | Swine epithelium | AY593835 |

| 87 | O Penghu/99 | Taiwan, 1999 | Swine epithelium | AY593833 |

| 88 | SAT 1 BOT 1/68 | Botswana (BEC), 1968 | 3 BTY, 5 BHK-21 | AY593845 |

| 89 | SAT 1 Rhod5/66* | Rhodesia, 1966 | 1 BTT | AY593846 |

| 90 | SAT 1/1 BEC | Botswana (BEC), 1970 | 2 LK | AY593838 |

| 91 | SAT 1/20 RV 11/37 | Pirbright, WRL, 1970 | 3 IBRS-2 | AY593839 |

| 92 | SAT 1/3 SWA1/49 | Unknown, 1970 | 4 IBRS-2 | AY593840 |

| 93 | SAT 1/4 SR2/58 | Rhodesia, 1970 | 3 IBRS-2 | AY593841 |

| 94 | SAT 1/5 SA/61 | Unknown, 1972 | 3 IBRS-2 | AY593842 |

| 95 | SAT 1/6 SWA40/61 | Unknown, 1970 | 3 IBRS-2 | AY593843 |

| 96 | SAT 1/7 ISRL 4/62 | Israel, 1962 | 3 IBRS-2 | AY593844 |

| 97 | SAT 2/1 Rhod/48 | Rhodesia, 1948 | 3 IBRS-2 | AY593847 |

| 98 | SAT 2/2 106/67 | Unknown, 1970 | 2 IBRS-2 | AY593848 |

| 99 | SAT 2/3 Kenya 11/60 | Kenya, 1960 | 3 IBRS-2 | AY593849 |

| 100 | SAT 3/2 SA57/59 | Unknown, 1969 | 1 LK | AY593850 |

| 101 | SAT 3/3 BEC20/61 | Botswana (BEC), 1961 | 2 LK | AY593851 |

| 102 | SAT 3/3 Kenya 11/60 | Kenya, 1960 | 4 IBRS-2 | AY593852 |

| 103 | SAT 3/4 BEC 1/65 | Botswana (BEC), 1965 | 1 LK | AY593853 |

| 104 | O/JPN/2000 | Japan | BEF, 4 BK | AB079061 |

| 105 | O strain Chu-Pei | Taiwan | Swine | AF026168 |

| 106 | OTau-YuanTW97 | Taiwan | Unknown | AF154271 |

| 107 | O1 Geshure | Israel | Unknown | AF189157 |

| 108 | O1 Yunlin | Taiwan | Swine | AF308157 |

| 109 | O/SK 2000 | South Korea | Unknown | AF377945 |

| AY312586 | ||||

| O/SK 2002 | South Korea | Unknown | AY312588 | |

| 110 | O Tibet /1/99 | China | Unknown | AF506822 |

| 111 | O Akesu/58 | China | BOV | AF511039 |

| 112 | SAT 2 ZIM/7/83 | Zimbabwe, clone | Vaccine strain, cloned | AF540910 |

| 113 | A12-strain 119 | United Kingdom | Tissue culture, cloned | M10975 |

| 114 | Asia 1 IND 63/72 | India, vaccine | Vaccine strain, unknown | AY304994 |

| 115 | A22/550 Azerbaijan 65 | USSR | Unknown | X74812 |

| 116 | O-HKN/2002 | China | Unknown | AY317098 |

| 117 | O strain OMIII | Attenuated from strain Akesu/58 | Unknown | AY359854 |

| 118 | Asia1 YNBS/58 | China | Unknown | AY390432 |

| 119 | C rp99 | C-S8c1 derivative | Persistently infected BHK-21 cells, passage 99 | FAN133358 |

| 120 | C rp146 | C-S8c1 derivative | Persistently infected BHK-21 cells, passage 146 | FAN133359 |

| 121 | C-s8c1 | Spain (Olot) | BHK-21 | FDI133357 |

| 122 | SAT 2 KEN/3/57 | Kenya | Unknown | FDI251473 |

| 123 | O1Campos | Brazil | Tissue culture, cloned | FDI320488 |

| 124 | C3Arg85 | Argentina | BHK-21 | FMV7347 |

| 125 | C3Arg85 Rb-15 | C3Arg85 derivative | Partially resistant BHK-Rb cells | FMV7572 |

| 126 | TAW/2/99 TC | Taiwan | BEF, 3 BHK-21, 1 BTY, 2 BHK-21 | AJ539136 |

| 127 | TAW/2/99 BOV | Taiwan | BEF, 3BHK-21, 1BTY, 2BHK-21, 1 BOV, 2 swine, 1 BOV | AJ539137 |

| 128 | Tibet/CHA/99 | China | 1 BOV, 3 BHK-21 | AJ539138 |

| 129 | O/SK 2000 | South Korea | BOV,1 BHK-21 | AJ539139 |

| 130 | SAR/19/2000 | South Africa | BOV, 2 PK, 1 IBRS-2, 1 BHK-21 | AJ539140 |

| 131 | UKG/35/2001 | United Kingdom | 2 swine | AJ539141 |

| 132 | A10-61 | Argentina | Unknown, cloned | PIFMDV1 |

| 133 | O1-Kaufbeuren/66 | Germany | BHK-21, cloned | PIFMDV |

*, RNA was extracted directly from tissue or vesicular fluid.

BHK, BHK21 baby hamster kidney cells; LK, PK, and BK, lamb, porcine, and bovine kidney cells, respectively; BTY, bovine thyroid cells; IBRS-2, porcine kidney epithelial cell line; ET, epithelial tissue; BTT, bovine tongue tissue; GP, guinea pig vesicular fluid; BOV, bovine; BVF, bovine vesicular fluid; BEF, bovine esophageal fluid.

Sequence numbers 104 to 133 are FMDV sequences from GenBank.

FMDV RNA isolation, RT-PCR amplification, and sequencing.

Full-length FMDV genome sequences were obtained by reverse transcription (RT) of the complete viral genomic RNA followed by redundant amplification and sequencing of overlapping cDNA fragments spanning the entire viral genome. The total RNA was extracted directly from 140 μl of vesicular fluid, the supernatants of infected cell cultures, or 0.1 g of epithelial tissue from vesicular lesions by the use of RNeasy Mini kits (QIAGEN) and was then resuspended in 40 μl of double-distilled H2O.

Complete viral genomes were reverse transcribed to cDNAs by use of a Super SMART PCR cDNA synthesis kit (Clontech), using the supplied modified oligo(dT) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After spin column purification, the full-length double-stranded cDNA from each isolate was amplified in eight identical long-distance PCRs (2 μl cDNA in a 50-μl reaction volume; 20 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 65°C for 15 s, and 68°C for 2 min) using primers supplied in the kit. Next, 21 overlapping 1.2-kb PCR amplicons spanning the whole FMDV genome were generated in 96-well plates (2.5 μl of template from each of the eight double-stranded cDNA replicates in 25-μl reactions using the primers described in Table S1 in the supplemental material). Adjacent amplicons overlapped for >50% of their lengths. To prevent truncation by subsequent rounds of PCR, we artificially created poly(C) sequences by substituting flanking sequences with specific primers (F1R and F2F) containing six C's or G's.

Amplified products of the correct size were purified (DNA filtration system; Eppendorf) and resuspended in 40 μl of sterile double-distilled H2O per well. All amplicon replicates (eight per FMDV subgenomic fragment per isolate) were subjected to direct sequencing (2.5 μl of template per reaction) using position-specific forward and reverse primers (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), Big Dye Terminator cycle sequencing kits (Applied Biosystems), and a PRISM 3730xl automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). To overcome virus variability and PCR/sequencing errors, we sequenced each amplicon in multiple reactions with both forward and reverse primers, specifically selected by serotype (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Since each amplicon overlapped its neighbor >50%, the multiple direct sequencing reactions resulted in a redundancy rate ranging from 13 to 48 and averaged 28 sequence events per nucleotide.

Direct DNA sequencing of amplicons derived from a given FMDV isolate yielded a master sequence representing the most probable nt for each position of the sequence. This approach prevented analyses of minor sequence variants, polymerase misincorporation errors, and sequencing ambiguities through multiple independent cDNA synthesis, PCR amplification, and direct sequencing events. Due to the quasispecies nature of FMDV populations, polymorphisms were detected at some nt positions. Nevertheless, all positions could be unambiguously assigned to a single nt due to the high degree of redundancy generated by the sequencing strategy. The following sequence ambiguity code was used: K (T/G), M (A/C), R (A/G), S (C/G), W (A/T), Y (C/T), B (C/T/G), D (A/T/G), H (A/C/T), V (A/C/G), and N (A/C/G/T).

Sequence analysis.

Bases were called from chromatogram traces produced with Phred (25), which also produced a quality file containing a predicted probability of error at each base position. Viral sequences were assembled with the Phrap (http://www.phrap.org) and CAP3 assemblers (43). Gap closure was performed as described previously (3). Multiple sequence alignments were performed with the ClustalW (1.7) and Dialign (2.2) computer programs (73, 107). The positions of 5′ UTR sequences presented in Results refer to the consensus sequence generated by ClustalW alignment of this region for the 103 isolates, with some manual editing. Nucleotide substitution analysis was carried out by use of the DISTREE (1.2) (103), DNArates (1.1) (105), ALISTAT (16), and PRETTY (GCG 10 software package [16]) programs. Analyses of codons and synonymous/nonsynonymous (syn/nonsyn) substitution ratios were calculated by using SNAP (77), CodonW (http://www.molbiol.ox.ac.uk/cu/), and codeml (PAML3.14 package), which was also used for statistical evaluations of heterogeneous selection pressures at amino acid sites (116). For protein analysis, the PRETTY program was used. Searches for motifs and/or signal sequences were performed with the MOTIFS (GCG package), HMM (58), pfscan (http://www.isrec.isb-sib.ch/ftp-server/pftools/pft2.2/pft2.2.tar.Z), and Blocks (36) programs of the PROSITE, Pfam, and Blocks databases. Transmembrane protein segment predictions were performed by using Memsat (50), Tmpred (41), Toppred (114), Psort (76), and Saps (11). Secondary structure predictions were performed for proteins by using GOR secondary structure prediction (29) and Pratt (48, 49) and for RNAs by using mfold (46, 117), rnafold (40), and Squiggles (83). Pseudoknot analysis was conducted with pknots (96).

Phylogenetic analysis was performed on aligned genomic and subgenomic regions of FMDV by utilizing the neighbor-joining and split decomposition methods as implemented in the Phylo_win (28) and/or SplitsTree 4.0 (http://www-ab.informatik.uni-tuebingen.de/software/jsplits/welcome_en.html) (44) software package and by utilizing maximum likelihood as implemented in Puzzle (104) and dnaml in the Phylip package (http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html) (27). Individual protein-coding regions were used to screen for incongruent tree topologies suggestive of genomic recombination, and split decomposition analysis (7) of genomic and subgenomic regions was utilized to graphically screen for reticulated branching patterns which were also suggestive of recombination. Similarity plots and bootscanning analysis (100), which compare a given query sequence to several reference sequences via incremental sliding sequence windows to yield corrected similarity values and bootstrap resampling frequencies, respectively, were performed as implemented in the SimPlot, v. 2.5, package (63), utilizing default settings and a window size of 400 nt. As a further test for potential recombination, Sawyer's run test (102), as implemented in GENECONV, v. 1.81 (http://www.math.wustl.edu/∼sawyer), was used on Dialign-aligned FMDV polyprotein-encoding regions, using default settings.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for the genome sequences of FMDV isolates sequenced for this study are listed in Table 1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

With the exception of the poly(C) tract, full-length genomic sequences from 103 FMDV isolates representing all serotypes, including isolates from serotypes not previously fully sequenced (SAT1 and SAT3), were obtained and analyzed. Given that the structure and dynamics of FMDV populations in nature are complex and the relatively small number of SAT2 and SAT3 genomes presented here, it is possible that additional sequence data from field isolates will alter the status of residues and nucleotides presented below as invariant.

FMDV genomes ranged from 8,046 to 8,215 nt, consistent with previously reported genome lengths (86, 108). Although small insertions/deletions were observed in the coding region affecting Lpro, 1B, 1C, 1D, and 3A, most variability in genome size was due to insertions/deletions in the UTRs.

5′ UTR.

The approximately 1,300-base 5′ UTR plays important roles in FMDV replication. However, the specific contribution of S fragment, poly(C) tract, and L fragment pseudoknots to FMDV biology is unknown. The cardiovirus poly(C) tract has been shown to affect virulence (23), while shortening of the FMDV poly(C) tract affected virus growth in vitro but not virulence in a suckling mouse model (95). The cre is essential for picornaviral replication and contains a conserved AAACA motif which in poliovirus functions as a template for 3Dpol-mediated uridylylation of 3B (75). Mutation of the FMDV cre stem region reduced virus RNA replication (68). The approximately 500-nt FMDV IRES, which is responsible for cap-independent polyprotein translation (60), is predicted to contain four structural domains (Fig. 1D, panel II, domains 2 to 5) that interact with cellular factors involved in host translation initiation (94). Domain 2 binds the polypyrimidine tract-binding protein at a UUUC motif. Domain 3 contains at least three loop structures that are conserved in all picornaviruses, including a GNRA motif essential for the maintenance of the IRES tertiary structure and potentially involved in long-range RNA-RNA interactions. The Y-shaped domain 4 and domain 5 interact with the host translational factors eIF4B and eIF4G (65, 99). A 22-nt spacer for ribosomal recognition separates the IRES from the first of two polyprotein start codons, and an additional 84 nt separates the first start codon from the second. Picornavirus utilization of the second start codon seems to be affected by its adjacent sequence and by sequences in the IRES (82). Unlike poliovirus, FMDV utilizes the second start codon twice as often as the first (66).

The analysis in this study of 5′ UTRs from 103 FMDV isolates showed that only 12% and 33% of nt were invariant in the 5′ UTR S and L fragments, respectively (Fig. 1B and C; Table 2). In pairwise comparisons, however, FMDV isolates averaged 80% and 85% nt identity for the S and L fragments, respectively, indicating a high degree of conservation between isolates. This suggests that although the FMDV 5′ UTR can tolerate changes at most positions, selective pressures clearly favor overall conservation, likely for the maintenance of a functional secondary structure. Relatively high rates of substitution (>10) in the 5′ UTR L fragment were observed at positions 513, 558, 615, 684, 696, and 1144 (Fig. 1B).

TABLE 2.

FMDV genome variabilitya

| UTR or genome region | No. of nt positions aligned | No. of invariant nt | % Invariant nt | Ts/Tv rate (%) | Average pairwise identity (%) | Minimum pairwise identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5′ UTR | 1,150 | 303 | 26 | 2.89 | 83 | 64 |

| S-UTR | 393 | 48 | 12 | 3.93 | 80 | 51 |

| L-UTR | 757 | 255 | 33 | 2.63 | 85 | 70 |

| 3′ UTR | 161 | 15 | 9 | 3.93 | 82 | 63 |

| ORF | 7,076 | 3,287 | 46 | 2.44 | 84 | 73 |

| Lpro | 606 | 227 | 37 | 3.23 | 80 | 61 |

| 1A | 255 | 143 | 56 | 2.53 | 84 | 73 |

| 1B | 660 | 243 | 37 | 1.75 | 75 | 62 |

| 1C | 675 | 235 | 35 | 1.84 | 75 | 58 |

| 1D | 693 | 147 | 21 | 1.55 | 68 | 48 |

| 2A | 48 | 23 | 48 | 2.64 | 89 | 73 |

| 2B | 462 | 282 | 61 | 6.67 | 91 | 81 |

| 2C | 953 | 527 | 55 | 5.14 | 89 | 78 |

| 3A | 459 | 160 | 35 | 3.75 | 85 | 68 |

| 3B | 216 | 96 | 44 | 5.51 | 89 | 69 |

| 3C | 639 | 380 | 59 | 4.12 | 89 | 77 |

| 3D | 1,410 | 824 | 58 | 5.53 | 91 | 83 |

Estimates were based on ClustalW (UTR data) or Dialign (ORF data) alignments of the 103 FMDV isolates examined. The number of invariant nt for each genomic region relative to the total number of positions was used to estimate the percentage of invariant nt. The ratio of transitions to transversions (Ts/Tv) was obtained by using Distree and Kimura 2 parameter correction with gamma distributions. ALISTAT was used to obtain the average % pairwise identity and the minimum pairwise identity. The 5′ UTR includes the S and L fragments 5′ of the first AUG. The S-UTR includes nt from position 1 to the poly(C) tract. The L-UTR includes nt from the end of the poly(C) tract to the first AUG. The 3′ UTR includes nt from the polyprotein stop codon to the poly(A) tail.

5′ UTR S fragment.

S fragment lengths averaged 322 and 373 nt for SAT and Euroasiatic isolates, respectively, and spanned positions 1 to 393 in the 5′ UTR alignment (Fig. 1B). SAT viruses contained insertions/deletions of 1 to 3 nt, with most occurring at positions 120 to 160 and 200 to 300, including SAT-specific nt present at positions 38, 39, 67, 95, 250, 350, 366, and 375. Euroasiatic isolates contained insertions/deletions of 1 to 5 nt in length (with the exception of isolates C Waldman strain 149, A Canefa 1/61, and A25 Argentina/59, which contained a 76-nt deletion between positions 153 and 228) and included Euroasiatic-specific nt present at positions 86, 123, 124, 144, 145, 155, 156, 157, 174, 181 to 191, 197 to 219, 240, 256, 277, 292 to 294, 300 to 306, and 324 (Table 3). Notably, SAT1/7 Isrl 4/62 and SAT2-3 Kenya 11/60 appeared to have the most complete S fragment sequences of those sampled, lacking both SAT and Euroasiatic-specific deletions, and contained nt at positions 142, 143, 239, 290, 291, and 307 which were absent from other viruses.

TABLE 3.

Selected FMDV 5′ UTR insertions/deletions

| Isolate or fragmenta | nt positions

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Ins | Dels | |

| S | ||

| A1 Bayern/Bavaria | 80-82 | |

| A3 Mecklenburg/68 | 80-82 | |

| A Canefa 1/61 | 114 | |

| A25 Argentina/59 | 114 | |

| Asia 1/1 PAK/54 | 114 | |

| O11 Indonesia/62 | 114 | |

| SAT 1/7 ISRL 4/62 | 142, 143 | |

| SAT 2/3 Kenya 11/60 | 142, 143 | |

| C Waldman strain 149* | 153-228 | |

| A25 Argentina/59 | 153-228 | |

| A Canefa 1/61 | 153-228 | |

| A24 | 270 | |

| O1 Argentina | 270 | |

| SAT 1/7 ISRL 4/62 | 290, 291 | |

| SAT 2/3 Kenya 11/60 | 290, 291 | |

| A Argentina/01 Areco | 290-293 | |

| A ARGp55/01 | 290-293 | |

| A ARGp64/01 | 290-293 | |

| A General Lopez/01 | 290-293 | |

| A Trenquelauquen/01 | 290-293 | |

| A Uruguay/01 | 290-293 | |

| A Uruguay/98 | 290-293 | |

| O UK 2001 | 292 | |

| O UK 2001-ED | 292 | |

| O UK 2001-FB | 292 | |

| O1 SKR/00 | 292 | |

| A22 Azerbaijan | 320 | |

| A22 Iraq24/64 | 320 | |

| A22 Iraq26/64 | 320 | |

| A22 Turkey/65 | 320 | |

| A28 Turkey/72 | 320 | |

| A22 Turkey/65 | 364-366 | |

| A28 Turkey/72 | 364-366 | |

| L | ||

| A28 Turkey/72 | 418-478 | |

| O1 Vallee/39 | 418-478 | |

| O5 India/62* | 418-478 | |

| O Akesu/58 | 418-478 | |

| O Akesu/58 vaccine | 418-501 | |

| C1 Noville/65 | 418-478 | |

| C1 Oberbayern/60* | 418-478 | |

| C-s8c1 Spain | 418-478 | |

| C-Perst.inf.BHKp99 | 418-478 | |

| C-Perst.inf.BHKp146 | 418-478 | |

| SAT 1/7 ISRL 4/62 | 418-487 | |

| A24 Cruzeiro/55 | 427-487 | |

| A21 Kenya/64 | 427-487 | |

| A20 USSR 1/64 | 427-487 | |

| O11 Indonesia/62 | 427-487 | |

| SAT 2/3 Kenya 11/60 | 427-487 | |

| SAT 1/20 RV 11/37 | 427-487 | |

| SAT 1 Rhod5/66* | 427-487 | |

| SAT 2/1 Rhod/48 | 427-487 | |

| SAT 2/2 106/67 | 427-487 | |

| SAT 3-4 BEC 1/65 | 427-487 | |

| A5 Westerwald/51* | 427-443 | |

| O Penghu/99 | 460-502 | |

| O Yunlin Tw97 | 460-502 | |

| O HKN/2002 | 460-502 | |

| O Taiwan/97 | 460-502 | |

| A26 Argentina/66* | 419-523 | |

| A16 Belem/59 | 419-523 | |

| O11 Indonesia/62 | 523-546 | |

| Asia1-IND 63/72 | 554-591 | |

| A3 Mecklenburg/68 | 554-591 | |

| A4 Spain* | 554-591 | |

| A2 Spain/69 | 554-591 | |

| A4 WG/72 | 554-591 | |

| A1 Bayern/Bavaria | 554-591 | |

| A10 Holland/42 | 554-591 | |

| O1 M11 | 554-591 | |

| O2 Brescia/47 | 554-591 | |

| O3 Venezuela/71 | 554-591 | |

*, isolates from which RNA was extracted directly from tissue or vesicular fluid.

Although the overall nt substitution rates in the S fragment were low, specific regions of variability were observed, and only 19 nt were invariant, excluding the regions used to prime amplification (Fig. 1C and D). S fragment sequences generally grouped into SAT and Euroasiatic lineages, which averaged only 50% nt identity with each other; however, little or no correlation with other serotypic groupings was observed (data not shown). Notably, several isolates of disparate serotypes contained very similar S fragment sequences, including the C Waldman strain 149 and A12 Valle strain 119 S fragments, which shared 98% nt identity.

In most cases, secondary structure analyses of S fragments predicted a single stem-loop structure similar to that previously proposed (12, 24). However, the S fragment sequences of 16% of the isolates folded into alternative structures within similar free energy levels (e.g., strains A22 Turkey/65, A24 Argentina 65, and Asia 1 Leb 83) (data not shown).

5′ UTR L fragment.

The 5′ UTR region of the L fragment ranged from 604 to 751 nt long. Remarkably, apparently unrelated virus isolates contained identical deletions in the L fragment (Table 3). SAT and Euroasiatic-specific L fragment insertions/deletions were identified, as were isolate-specific insertions/deletions, including an 18-nt insertion located 28 nt downstream of the poly(C) tract in strain A5 Westerwald/51.

The pseudoknot region between positions 403 and 600 was highly tolerant to changes, with no invariant nt located within the first 200 positions and insertions/deletions tolerated at each position (Fig. 1C). Previously undescribed invariant nt and motifs located between the pseudoknot region and the IRES included AGAAWYGGGACGU (positions 617 to 629), GCRCACGWAACGCGC (positions 632 to 646), and ACAAAC (positions 668 to 673) within the cre.

FMDV IRES sequences (positions 640 to 1151) showed 70 to 100% nt identity in pairwise comparisons, 47% invariant nt, and numerous invariant motifs in the predicted secondary structure domains (Fig. 1C and D). Domain 2 contained the polypyrimidine tract-binding protein motif UUUC and three previously undescribed motifs at the base, bulge (invariant GGUCUWGAG motif), and apex regions of the stem-loop. Domain 3 contained GYRA (corresponding to the conserved picornaviral GNRA motif) and CRAAA (except in isolates O1Argentina/65 and OAkesu/58) motifs in loops A and B, respectively. While the picornavirus domain 3 loop D motif ACCC was present in 99/103 FMDV isolates, the loop 3C motif ACAC was not conserved in FMDV. Domain 3 also contained novel highly conserved motifs, including the UCGUMGCGGAGCA (positions 823 to 835) motif and GRUACUGGUA and GRGACUGGUA motifs (positions 965 to 974), specific for Euroasiatic and SAT serotypes, respectively, and CUGGWGRCAGGCUAAGGAUGCCCU (positions 983 to 1006), predicted to form a prominent bulge at the base of the stem (Fig. 1C and D). Domain 4 was highly conserved, with two novel invariant motifs (GAUCUGAG [positions 1039 to 1046] and UUAAAAG [positions 1080 to 1087]) predicted to form prominent bulges in the secondary structure. In domain 5, 19 of the 21 nt were invariant (Fig. 1C and D). The conservation of these motifs suggests biological significance. Notably, the 22-nt region between the IRES and the first AUG was highly variable, possibly underlying FMDV's preferential use of the second start codon (9, 66). In summary, the FMDV 5′ UTR, although tolerant for nt substitutions and insertions/deletions, showed significant conservation, especially in the IRES, where novel sequence motifs were identified.

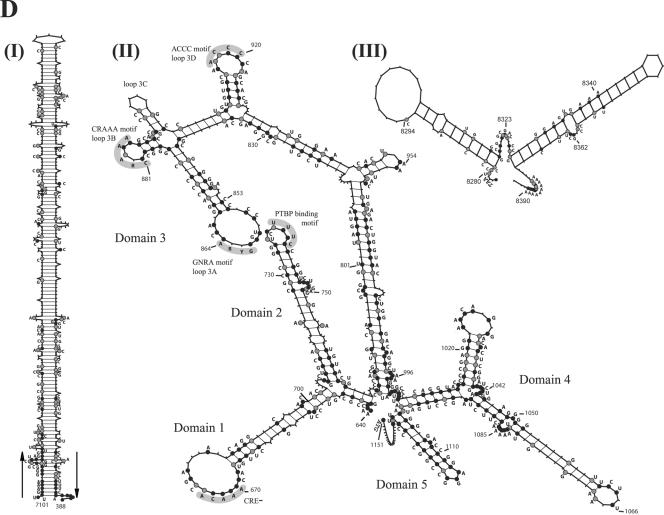

Polyprotein region. (i) Nucleotide sequence and codon analysis.

The nucleotide variability for the 103 FMDV polyprotein (ORF) and individual protein regions is summarized in Table 2. Overall, 46% of all nt were invariant, with 73% nt identity between the least similar pair of sequences. An average transition/transversion (Ts/Tv) rate of 2.4 and syn/nonsyn substitution ratio of 2.1 were observed. As expected, the region encoding 1D was the most variable, exhibiting the lowest percentage of invariant nt (21%), Ts/Tv rate (1.55), and syn/nonsyn ratio (1.03) of all regions. In fact, excluding the highly conserved 1A (VP4) protein, regions encoding structural proteins had significantly lower Ts/Tv rates, nonsyn substitutions/site, and syn/nonsyn ratios than the rest of the genome. Although the substitution rates given here are averages for each protein-coding region, specific regions or residues within each protein were observed to contain higher or lower substitution rates (Fig. 2B and C).

FIG. 2.

FMDV coding region variability. (A) Schematic diagram of FMDV polyprotein coding region showing the positions of, from top to bottom, protein-encoding regions (open boxes), cleavage intermediates, and mature proteins (lines). (B) Graphic representation of rates of nt substitution per site as calculated with DNArates software. (C) Graphic representation of nonsynonymous substitutions per site as calculated with SNAP software.

In general, regions encoding FMDV nonstructural proteins were highly conserved between isolates, exhibiting higher percentages of invariant residues, higher Ts/Tv rates and syn/nonsyn substitution ratios, and lower overall numbers of nonsyn changes/site (Table 2; Fig. 2C). The most conserved FMDV regions were those encoding 2B and 3C, which exhibited the highest percentage of invariant nt (61% and 59%, respectively) and amino acids (76%) in the genome. Notably, the nonstructural proteins Lpro, 3A, and 3B exhibited variability comparable to that of the structural proteins 1B, 1C, and 1D (Table 4), suggesting that these proteins are subjected to selective pressures distinct from those on the other nonstructural proteins. A comparison of CODEML ω rates between different substitution models further indicated that four of these proteins (Lpro, 1D, 3A, and 3B) may indeed undergo diversifying selection (Table 4) (116). Notably, this was observed for relatively few codons (1.5% to 7.6%), with fewer highly significant ones (P > 0.9) tending to cluster within each protein (positions 19, 20, 22, 23, and 82 in Lpro; positions 45, 48, 142, 143, 144, and 146 in 1D; positions 44, 132, 135, 136, and 144 in 3A; positions 4 and 11 in 3B1; and positions 17, 18, and 19 in 3B2). Interestingly, the variable capsid proteins 1B and 1C did not appear in this analysis to undergo diversifying selection (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

FMDV genome variability in encoded amino acid sequencesa

| Genome region | No. of aa positions aligned | No. of invariant aa | % Invariant aa | SNAP result

|

CODEML result

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syn | Nonsyn | Syn/nonsyn | ω | t | PS | ||||

| ORF | 2,360 | 1,363 | 58 | 756 | 362 | 2.08 | ND | ND | ND |

| Lpro | 202 | 89 | 44 | 70 | 45 | 1.55 | 0.27 | 20.8 | Y |

| 1A | 84 | 68 | 81 | 33 | 5 | 6.6 | 0.01 | 22.5 | N |

| 1B | 221 | 103 | 47 | 100 | 63 | 1.6 | 0.06 | 34.9 | N |

| 1C | 225 | 87 | 39 | 99 | 63 | 1.6 | 0.08 | 32.9 | N |

| 1D | 232 | 56 | 24 | 102 | 99 | 1.03 | 0.16 | 35.8 | Y |

| 2A | 17 | 11 | 65 | 5 | 0.52 | 9.6 | ND | ND | ND |

| 2B | 153 | 117 | 76 | 35 | 7 | 5 | 0.06 | 8 | N |

| 2C | 318 | 228 | 72 | 83 | 18 | 4.6 | 0.06 | 10.5 | N |

| 3A | 153 | 57 | 37 | 44 | 21 | 2.1 | 0.16 | 12.7 | Y |

| 3B | 72 | 36 | 50 | 17 | 6 | 2.8 | 0.33 | 8.2 | Y |

| 3C | 213 | 163 | 76 | 55 | 14 | 3.9 | 0.04 | 11.3 | N |

| 3D | 471 | 348 | 74 | 113 | 20 | 5.6 | 0.06 | 8.4 | N |

The synonymous/nonsynonymous (syn/nonsyn) substitutions were estimated by use of the Nei and Gojobori algorithm as implemented in SNAP. Estimates for diversifying positive selection were obtained by using codeml. ω, nonsyn/syn ratio averaged over sites (dN/dS); t, maximum-likelihood tree length measured by the number of nt substitutions along the tree per codon; PS, positive selection; Y, yes; N, no; ND, not done.

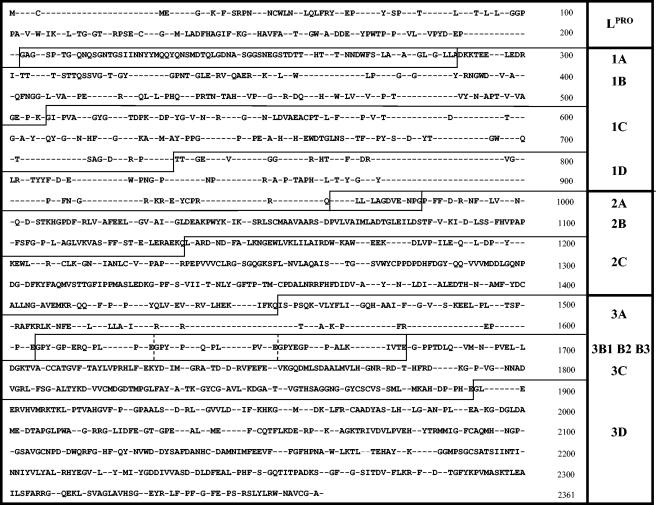

(ii) Amino acid sequence analysis.

Fifty-eight percent of all amino acids (aa) were invariant among the FMDV isolates analyzed here, with the percentage of amino acid conservation for each viral protein correlating with nt conservation in the corresponding genomic region (Fig. 3; Tables 2 and 4). Positions at putative protein cleavage sites showed various degrees of sequence conservation, with Euroasiatic lineages being more conserved than SATs. Residues at the 1A/1B, 2A/2B, 2B/2C, 2C/3A, and 3B/3C cleavage sites exhibited high degrees of conservation (Table 5).

FIG. 3.

FMDV invariant amino acids (single letter code). The consensus sequence is based on the comparison of 103 FMDV isolates conducted for this study, with the exception of the 1D region, which also included all 1D sequences available in GenBank (release 141).

TABLE 5.

FMDV polyprotein cleavage site variabilitya

| Junc- tion | Common amino acids for serotype

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALL (n = 133) | SAT (n = 16) | A (n = 46) | O (n = 23) | C (n = 7) | Asia (n = 6) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L/1A | R | K | L | K | * | G | A | G | Q | L | F | L | R | * | G | A | G | Q | R | K | L | K | * | G | A | G | Q | R | K | L | K | * | G | A | G | Q | R | K | L | K | * | G | A | G | Q | K | R | L | K | * | G | A | G |

| K46 | R46 | V3 | R36 | H3 | A1 | Y2 | V2 | K2 | H1 | K9 | R10 | H1 | K8 | R7 | R2 | Q2 | R1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L15 | F15 | T1 | Q4 | N1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T1 | Y3 | W1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Q6 | N1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| W1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1A/1B | A | L | L | A | * | D | K | K | T | A | L | L | A | * | D | K | K | T | A | L | L | A | * | D | K | K | T | A | L | L | A | * | D | K | K | T | A | L | L | A | * | D | K | K | T | A | L | L | A | * | D | K | K |

| T1 | T1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1B/1C | P | S | K | E | * | G | I | F | P | P | A | K | Q | * | G | I | L | P | P | S | K | E | * | G | I | F | P | P | S | K | E | * | G | I | F | P | P | S | K | E | * | G | I | F | P | P | S | K | E | * | G | I | V |

| A10 | Q17 | V1 | V21 | S3 | E2 | I6 | Q1 | V10 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| V2 | I7 | V2 | V2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| G2 | L7 | G1 | F1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| M1 | M1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1C/1D | P | R | T | Q | * | T | T | S | T | P | S | R | Q | * | T | T | S | A | P | R | Q | Q | * | T | T | A | T | A | R | T | Q | * | T | T | S | A | A | R | Q | Q | * | T | T | T | T | A | R | Q | Q | * | T | T | T |

| A67 | S8 | Q27 | E14 | A43 | A51 | V3 | T2 | V2 | P10 | T7 | V7 | A9 | E10 | T6 | R2 | A3 | A1 | R2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T1 | V5 | R26 | T23 | V9 | A2 | A2 | S10 | S4 | A3 | R5 | P1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A2 | A16 | P2 | T2 | T7 | V1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T2 | P14 | L1 | C1 | A3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| C1 | S12 | S1 | L1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| V1 | R1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| L1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1D/2A | P | A | K | Q | * | L | L | N | F | P | A | K | Q | * | L | C | N | F | P | A | K | Q | * | L | L | N | F | P | V | K | Q | * | T | L | N | F | P | A | K | Q | * | L | L | N | F | P | E | K | Q | * | V | L | N |

| V5 | G1 | R1 | S1 | C12 | S1 | C1 | V3 | E6 | M3 | L1 | S1 | C1 | E8 | R3 | A2 | L7 | E1 | S2 | L1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| E25 | T19 | S3 | D2 | A1 | G1 | T2 | T1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T2 | A2 | A1 | V1 | S1 | T1 | A1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| S1 | V4 | F1 | F1 | V1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| V38 | M3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| K1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| D2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2A/2B* | S | N | P | G | * | P | F | F | F | S | N | P | G | * | P | F | F | F | S | N | P | G | * | P | F | F | F | S | N | P | G | * | P | F | F | F | S | N | P | G | * | P | F | F | F | S | N | P | G | * | P | F | F |

| P2 | L1 | R1 | L2 | S1 | L2 | P1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2B/2C | A | E | K | Q | * | L | K | A | R | A | E | K | Q | * | L | K | A | R | A | E | K | Q | * | L | K | A | R | A | E | K | Q | * | L | K | A | R | A | E | K | Q | * | L | K | A | R | A | E | K | Q | * | L | K | A |

| R3 | R1 | R1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2C/3A | I | F | K | Q | * | I | S | I | P | I | F | K | Q | * | I | S | I | P | I | F | K | Q | * | I | S | I | P | I | F | K | Q | * | I | S | I | P | I | F | K | Q | * | I | S | I | P | I | F | K | Q | * | I | S | I |

| L1 | L2 | L2 | T1 | V1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| T3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| V1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3A/3B | P | Q | A | E | * | G | P | Y | A | P | Q | A | E | * | G | P | Y | A | P | Q | A | E | * | G | P | Y | A | P | Q | A | E | * | G | P | Y | A | P | Q | A | E | * | G | P | Y | A | P | Q | A | E | * | G | P | Y |

| R9 | T2 | T24 | K1 | T1 | R3 | T1 | T3 | T4 | T1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| H5 | S2 | H1 | H4 | V1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| K1 | V1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3B/3C | I | V | T | E | * | S | G | A | P | I | V | T | E | * | S | G | C | P | I | V | T | E | * | S | G | A | P | I | V | E | * | S | G | A | P | I | V | T | E | * | S | G | A | P | I | V | T | E | * | S | G | A | |

| T1 | C15 | T1 | A2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3C/3D | P | H | H | E | * | G | L | I | V | P | H | T | E | * | G | L | V | V | P | H | H | E | * | G | L | I | V | P | H | H | E | * | G | L | I | V | P | H | H | E | * | G | L | I | V | P | H | H | E | * | G | L | I |

| Q2 | T13 | V16 | L1 | H2 | I2 | L1 | I1 | V1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I2 | N1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Individual columns and rows represent FMDV serotypes and protein junctions, respectively. The first line in each row indicates the most frequent amino acid for each position, with alternative amino acids listed below and subscripts indicating the number of isolates with that particular residue. The total number (n) of isolates compared within each serotype is indicated at the top. *, protein cleavage point.

Leader proteinase.

FMDV Lpro is expressed as long (Lab) and short (Lb) isoforms that result from alternative usage of either the first or second start codon, respectively, with the sequence between the two AUGs predicted to form a stable hairpin structure crucial to IRES activity (39, 66). Lpro isoforms have indistinguishable activities and specificities and have been proposed to play a role in virulence that may involve the regulation of host interferon responses (89).

Lpro lacked insertions/deletions, with the exception of two additional aa in Euroasiatic lineages (positions 22 and 23). Each methionine start codon was invariant, indicating that both Lpro isoforms are significant for aspects of FMDV biology. Consistent with the previously described hypervariability in the region flanked by the two AUGs, only one residue (C6) was invariant in this region (113). Only 44% of the residues in Lb were invariant, making it much less conserved than was previously reported (30). Although substitutions were concentrated in terminal regions of Lpro, the predicted secondary structure in these regions remained relatively unaltered (data not shown).

A detailed analysis of the Lpro/1A junction resulted in a more ambiguous cleavage motif than was previously described (Table 5) (113). Only GAGXS at the 1A N terminus and the previously described basic residue (K/R) required for cleavage at the Lpro C terminus were invariant. Residues required for Lpro catalytic activity (C52, H149, and D165) (32, 59), suggested to be involved in Lpro autocatalysis (E77) (89), and important for eIF4G cleavage (H110 and H139) (90) were invariant, except for an H110D substitution in all SAT viruses, an E77Q substitution in O6 Pirbright/65, and an E77K substitution in A Phillipines/75 (Table 6). The present FMDV analysis revealed that only 43 of the 65 residues previously identified as conserved between FMDV O1 Kaufbeuren/66 Lpro and the aphthovirus equine rhinitis A virus Lpro were invariant, with 35 of the 43 residues concentrated in three distinct regions (positions 44 to 63, 95 to 110, and 133 to 185) (38) (Table 6). Additional, previously undescribed invariant FMDV Lpro motifs are shown in Table 6.

TABLE 6.

Amino acid conservation in FMDV and ERAV Lpro

| Position no.a | 1 | 6 | 30, 31 | 37 | 40 | 42 | 44-47 | 51-55 | 58-63 | 66, 67 | 73 | 75, 76 | 80 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMDVb | M | C | ME | G | K | F | SRPN | NCWLN | QLFRY | EP | Y | SP | T | |||||||||||||||

| FMDV/ERAVc | M | NCWLN | QL | T | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Position no. | 87 | 91 | 93 | 95 | 98-102 | 104 | 106 | 108-110 | 112 | 114, 115 | 117, 118 | 121-124 | 126 | 130 | ||||||||||||||

| FMDV | L | T | L | L | GGPPA | V | W | IK(H/D) | L | TG | GT | RPSE | C | G | ||||||||||||||

| FMDV/ERAV | T | L | G PP | V | GT | P | G | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Position no. | 133-143 | 145, 146 | 149-153 | 156 | 159, 160 | 162 | 164-166 | 169-173 | 175 | 178, 179 | 183-185 | 187-189 | ||||||||||||||||

| FMDV | M(C/T)LADFHAGIF | KG | HAVFA | T | GW | A | DDE | YPWTP | P | VL | VPYD | EP | ||||||||||||||||

| FMDV/ERAV | L DF A | K | HAVF | T | GW | DD | YP TP | VL | PYD | |||||||||||||||||||

Numbers indicate Lpro amino acid positions from the first polyprotein AUG of Dialign-aligned FMDV polyproteins.

Invariant Lpro residues among 133 FMDV isolates. The proteolytic active sites C52 and H149 are shown in bold.

Invariant Lpro residues between FMDV and ERAV sequences (38).

These data indicate that despite a relatively low overall Lpro aa sequence conservation among the FMDV isolates examined here, functional elements such as the catalytic and cleavage sites and additional, previously undescribed motifs are invariant. The variability observed at the Lpro N and C termini may affect specific virus-host interactions, including ribosomal recognition of alternative start codons.

Structural proteins.

FMDV structural proteins are involved in capsid assembly and stability, virus binding to target cells, and antigenic specificity, influencing significant aspects of virus infection and immunity (45). The high level of variability in FMDV external capsid proteins observed here likely reflects the selective pressures on them.

(i) 1A (VP4).

1A was the most conserved FMDV protein, with 81% of the aa being invariant (Fig. 3; Table 4), including the N-terminal myristylation site and a previously identified heterotypic swine and bovine T-cell epitope (1A positions 20 to 35) (10). Interestingly, the Q73 residue in the SAT viruses distinguishes them from Euroasiatic lineages. Residues potentially specific for SAT2 and SAT3 (I76) and for SAT1 (V80) were also identified.

(ii) 1B (VP2).

1B, a protein of 218 or 219 aa, plays a critical role in virion structural stability and maturation (14). N-terminal regions of 1B contain previously undescribed motifs. For example, DKKTEETTLLEDRILTTRNGHT(T/I)STTQSSVG and DKKTEETT(L/H)LEDRI(L/M/V)TT(S/R)H(G/N)TTTSTTQSSVG are conserved among Euroasiatic and SAT virus isolates, respectively. Three previously identified T-cell epitopes (positions 48 to 68, 114 to 132, and 179 to 187) were conserved (88). Notably, only the N-terminal half of each epitope was invariant, while their C-terminal regions were highly variable.

(iii) 1C (VP3).

1C, a protein of 219 to 221 aa, contains important conformational neutralizing epitopes and makes significant contributions to capsid stability (62). Among the FMDV isolates examined here, 1C was highly variable, with only 39% of the aa being invariant. Most amino acid substitutions were concentrated in four regions (positions 55 to 88, 130 to 140, 176 to 186, and 196 to 208), with insertions/deletions present in the first two regions and a previously described T-cell epitope present in the second region (88). The 1B/1C cleavage site was nearly invariant in Euroasiatic lineages but much less conserved among SAT isolates (Table 5).

(iv) 1D (VP1).

1D is the most studied FMDV protein due to its significance for virus attachment and entry, protective immunity, and serotype specificity (45). 1D ranges in size from 217 to 221 aa, with insertions/deletions contained in regions 140-150 and 166-170. Overall, only 26% of the 1D residues are invariant. The invariant residues and motifs are shown in Fig. 3. Given the available data and the proposed significance of the conserved RGD motif for virus reception and pathogenesis (71, 72), it is notable that complete integrin-binding RGD motifs were lacking in 9 of the 103 FMDV isolates examined here (GGD in C Waldman strain 149 and C4 Tierra del Fuego/66, TGD in C5 Argentina/69, RGE in Asia1/2 Isrl 3/63 and A21 Kenya/64, RDD in A25 Argentina/59 and A Canefa 1/61, HGD in Asia1/3 Kimrom, and PGD in A27 Colombia/67) and in additional sequences present in GenBank (RGN in Asia1 Pak/1/54 and O/Syria/1/87, RSG in A A/IND/110/99, RGE in O KEN/5/95, KGD in O PAK/1/94 and O/IRQ/26/2000, SGD in O Akesu/58, and IGD in O3/Venezuela/51), with substitutions tolerable at any one of the three residues.

Exposure of the 1D N terminus, a region which includes a 10-aa motif which is conserved in several other picornaviruses, is critical for poliovirus entry into the cell (13). The FMDV 1D sequences studied here lack this N-terminal motif, suggesting that some aspects of viral entry may differ from those of other picornaviruses.

Structural implications of capsid protein amino acid conservation.

Picornaviral 1A is cleaved from the 1AB (VP0) precursor by unknown mechanisms, and this cleavage is required for virion maturation and infectivity (6, 74). During poliovirus entry into host cells, 1A is involved in receptor-mediated capsid conformational changes resulting in membrane ion channel formation and the release of viral RNA into the cytoplasm (reviewed in reference 42). Several FMDV residues which are known or suspected to affect 1AB cleavage based on their homology to other picornaviral 1ABs were identified in the FMDV isolates examined here. Notably, a number of these residues were located in previously unidentified invariant sequence motifs, suggesting that the critical function of these residues may be contextual. Specifically, these included 1B residues H145, P144, and L83 and 1C residues G39, F41 (replaced by Y in three isolates), and A50, which is included in the conserved motif LDVAEACPT (positions 45 to 53) (8). Additional residues contributing to the 1AB cleavage pocket include 1D P204, contained in the motif RMKRAE(T/L)YCPR (positions 195 to 205), and 1B V32 (I in SAT2 viruses), T33, and Y36, included in the motif TTSTTQSSVG(V/I)T(Y/F)GY (positions 22 to 36). C-terminal to this last motif lies a putative serotype sequence signature (positions 36 to 47) confirmed for 173 available 1B sequences (YSTXEDHXXGPN in A viruses, YXTXEDFVXGPN in O viruses, YATXEDXXGPN in C viruses, YXVXEDAVSGPN in Asia1 viruses, YAXXDXFLPGPN in SAT1 viruses, YADXDSFRXGPN in SAT2 viruses, and YXSADRFLPGPN in SAT3 viruses) and the motif GPNT(S/N)GLEXRVxQAER(F/Y)(F/Y)K (positions 45 to 63), which is present in all FMDV isolates examined here.

An H-rich region at the 1B/1C interphase is proposed to mediate 1B-1C hydrogen bonding and is likely involved in virion sensitivity to acid, a characteristic with implications for virus stability and transmission (2). 1B residues H21 (position 19 in SAT viruses), H145, H157, and H174 were invariant in all FMDV isolates studied here, while H87P and H168Y substitutions were present in serotype C and Euroasiatic viruses, respectively. In addition, 1C contained five invariant H residues, at positions 86 (84 in SAT viruses), 109, 146, 149, and 198 (196 in SAT viruses).

The N termini of five 1C molecules make up the β annulus at the axis of virion fivefold symmetry, thus contributing to capsid stability (1). The 53 N-terminal residues of 1C, including P4, which is possibly involved in binding to the 3Cpro substrate-binding site, and C7, a residue that is invariant in Euroasiatic isolates and involved in disulfide bonding between 1C N termini, were invariant within serotypes (1). However, all SAT viruses demonstrated an unexpected nonconservative C7V substitution, suggesting that SAT virus capsids may exhibit distinct physical properties.

Nonstructural proteins. (i) 2A.

FMDV 2A is an 18-aa peptide similar to the C terminus of cardiovirus 2A, a protein which induces a modification of the cellular translation apparatus resulting in 2A release (19, 20). The FMDV 2A proteins examined here averaged an 89% amino acid identity. Fourteen residues were identified as ≥98% invariant, including the DVEXNPG motif, which is essential for encephalomyocarditis virus 2A activity (21). The high level of 2A conservation likely reflects structural and functional constraints associated with the small size of the protein.

(ii) 2B.

FMDV 2B localizes to sites of virus genome replication in ER-derived vesicles (106). The 2B protein in other picornaviruses enhances membrane permeability, blocks protein secretory pathways, suppresses apoptotic responses by affecting intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, and is implicated in virus-induced cytopathic effects (17, 47, 112).

FMDV 2B, a protein of 154 aa, contains 117 invariant residues (Table 4), with amino acid substitutions limited to only one or two alternate residues per site. A previously undescribed, conserved transmembrane domain was predicted between positions 120 and 140, suggesting that 2B is an integral membrane protein and consistent with the proposed localization of 2B to ER-derived vesicles (106).

(iii) 2C.

FMDV 2C is homologous to poliovirus 2C, an ATPase affecting the initiation of minus-strand RNA synthesis and whose precursor, 2BC, induces vesicle formation in the cytoplasm (53). FMDV 2C localizes to membrane-associated virus-replicating complexes (106).

FMDV 2C is 318 aa long and contains 72% invariant residues, including those of the putative ATP/GTP binding domain (positions 110 to 116, 160 to 163, and 243 to 246) (15). Amino acid substitutions unique to individual SAT serotypes were identified between positions 33 and 92.

(iv) 3A.

FMDV 3A has been implicated in virus virulence and host range, similar to the 3A proteins of other picornaviruses (33, 61). Deletions in 3A have been associated with FMDV attenuation in cattle and with the porcinophilic phenotype of O Taiwan/97 (54). However, evidence suggests that other viral genetic determinants are necessary for these phenotypes (54, 81).

FMDV 3A ranges from 143 to 153 aa, with insertions/deletions preferentially occurring at positions 70 to 110 and 130 to 150, regions identified here as containing previously undescribed variability. In fact, 3A is one of the most variable proteins encoded by FMDV, with fewer invariant aa (37%) than the variable capsid proteins 1B and 1C and the highly variable Lpro and contrasting with the high degree of conservation previously reported for a limited number of PanAsia 3A sequences (54). As described above, 3A contains residues predicted to undergo positive selection, including the Q44 residue, at which a Q44R mutation was previously associated with a pathogenic phenotype in guinea pigs (78). Although the Q44R mutation was present in several guinea pig-adapted isolates examined here, this mutation was absent from other isolates adapted to guinea pigs and present in still others that were not adapted to guinea pigs, suggesting that alternative mutations may underlie this particular phenotype. A previously described transmembrane domain (positions 60 through 76) (54) which tolerated conservative amino acid substitutions at all positions except invariant residues L64, L68, A70, and I72 was also variable in this study. Our data revealed limited variability in the potential 3A T-cell epitope that was previously identified between positions 21 and 35 (10). The variable nature of 3A suggests that it may be highly informative for epidemiologic or forensic purposes. Additionally, the likely role for 3A in virulence and host range suggests that interactions with host factors underlie 3A's variability and the diversifying selection predicted to act upon it.

(v) 3B.

FMDV is the only picornavirus to encode multiple 3B proteins (3B1, 23 aa; 3B2, 24 aa; and 3B3, 24 aa), whose homologue in poliovirus primes genomic RNA synthesis during virus replication (26, 85). In our study, 3B1, 3B2, and 3B3 were present in all FMDV isolates. The motif GPYXGP (except for the substitution GPYXRP in Sat 1/20 Rv 11/37), which contains a Y residue homologous to the poliovirus Y3 residue involved in phosphodiester linkage of 3B to the 5′ end of the viral genome, was invariant in the N terminus of each protein (5) (Table 7). The 3B C-terminal regions contained more amino acid variability, including the majority of observed nonconservative substitutions and the fewest invariant residues. Notably, 3B3 was highly conserved in all isolates examined, supporting previous experimental evidence indicating that only this 3B isoform is essential for virus viability (26, 84). 3B1 and 3B2 were more variable, and in fact, contained residues predicted here to undergo diversifying selection (3B1 residues 4 and 11 and 3B2 residues 17, 18, and 19). These data, in conjunction with experimental data indicating that the deletion of 3B1 and 3B2 may affect FMDV virulence and host range (84), suggest that, similar to that of 3A, 3B1 and 3B2 protein variability reflects host range-specific functions.

TABLE 7.

FMDV 3B (VPg) variability

| Serotype | Sequencea | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3B1 | G | P | Y | A* | G | P | L | E | R | Q | K* | P | L | K | V | R | A | K | L | P | Q | Q | E | |

| T23 | M3 | Q14 | R2 | L14 | K38 | T5 | E4 | P1 | R6 | A14 | ||||||||||||||

| S2 | V1 | R19 | V2 | R1 | F1 | K4 | H5 | |||||||||||||||||

| I1 | R1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3B2 | G | P | Y | A | G | P | M | E | R | Q | K | P | L | K | V | K | A* | K* | A* | P | V | V | K | E |

| V3 | R1 | L23 | D1 | K10 | Q18 | R3 | L15 | R4 | V29 | R21 | L15 | S1 | A16 | R1 | ||||||||||

| T4 | T3 | I4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| E1 | N/P/V1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3B3 | G | P | Y | E | G | P | V | K | K | P | V | A | L | K | V | K | A | K | N | L | I | V | T | E |

| D1 | M1 | R1 | R1 | A1 | L1 | R1 | T2 | R1 | A15 | P15 | ||||||||||||||

| M3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

The most frequent amino acid for each position is shown in the top row for each serotype; alternative amino acids and the number of isolates with that particular residue (subscripts) are listed below. SAT serotype-specific residues are shown in italics. Asterisks indicate positions predicted to undergo diversifying selection by codeml analysis.

(vi) 3C.

FMDV 3Cpro is a 213-amino-acid proteinase involved in the cleavage of most viral precursor proteins and of host factors associated with translation (eIF4A and eIF4G) and transcription (histone H3). A previous mutational analysis of 3Cpro identified the catalytic triad residues C163, H46, and D84 and residues critical for proper protein folding, i.e., D84 and Y136, all of which were invariant in the isolates examined here (34). A previously undescribed invariant motif (VKGQDMLSDAALMVLH) and a predicted transmembrane domain were identified at positions 76 to 91 and 27 to 44, respectively. A high degree of overall 3Cpro conservation indicates a limited tolerance for mutations, likely due to significant structural/functional constraints. Despite the 3Cpro conservation, 36 SAT-specific residues were identified, suggesting that distinct selective pressures exist for the two virus groups.

(vii) 3D.

The 469-amino-acid viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase 3Dpol, responsible for generating minus- and plus-sense genomic RNA, is one of the most conserved FMDV proteins. Our analysis indicated that although it is conserved, 3Dpol is more tolerant of substitutions than was previously reported (56), as our results extended the proportion of variable residues from 8.6% to 26%. D245, N307, and G295, which are essential for maintaining the functional integrity of the picornaviral polymerases (56), were invariant in FMDV 3Dpol, along with other residues described as being highly conserved among all RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (31), including the NTP-binding residues G337, D338, and D339 (115). The previously described picornaviral polymerase peptide motifs KDELR, PSG, YGGD, and FLKR were conserved among all FMDV isolates analyzed (18, 51). Finally, the three previously described hypervariable, hydrophobic antigenic regions of 3Dpol (aa 1 to 12, 64 to 76, and 143 to 153) were also variable in all virus isolates examined here (31).

3′ UTR.

The picornaviral 3′ UTR binds several viral and host proteins and is believed to contain structural cis-acting elements required for negative-strand RNA synthesis (4). Removal of the terminal poly(A) tract or mutagenesis of structural elements abrogates the infectivity of FMDV infectious clones (98). FMDV 3′ UTR sequences stimulate virus-specific, IRES-dependent translation (67) and likely affect other aspects of viral replication, including genome circularization (37).

The FMDV 3′ UTRs were highly variable in length among the isolates, ranging from 85 to 101 nt. A secondary structure analysis of the FMDV 3′ UTR confirmed the Y shape which is also predicted for other picornaviral 3′ UTRs, suggesting that the structure plays an important role in the 3′ UTR function (Fig. 1D and data not shown). A previously unidentified motif was located at the vertex of the Y structure between positions 37 and 61 (Fig. 1C and D). In some cases, however, structural features which could conceivably affect the efficiency of ribosome/RNA dissociation and translation were observed (for example, the exceptionally long stem of A10 Holland/42 and the short stem of O2 Brescia/47) (data not shown).

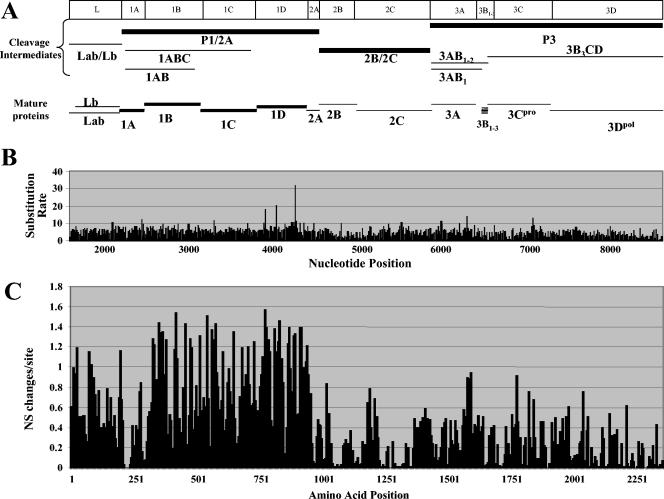

FMDV phylogenetic and recombination analysis.

To date, phylogenetic analyses have been performed largely on FMDV sequences from the 1D coding region. These analyses have permitted the discrimination among serotypically related FMDV isolates (55). Split decomposition, a clustering technique used previously on 1D sequences to suggest the occurrence of quasispecies evolution in Euroasiatic FMDV (22), was used to examine the complete genome sequences of all 103 isolates described here (Fig. 4A). The results indicated that complex phylogenetic relationships exist between members of different serotypes, including relationships between the A24 Argentina/65 and European/South American O1 viruses; between A12 Valle strain 119 and C Waldman strain 149; between the O1 M11, O2 Brescia/47, and O3 Venezuela/71 viruses and European serotype A viruses; between 05India/62 and Asia1 viruses from Israel; among six SAT1 and three SAT3 viruses; and most notably, between SAT1/7 Isrl 4/62 and SAT2/3 Kenya 11/60 and other SAT1 and SAT2 viruses (Fig. 4A and data not shown).

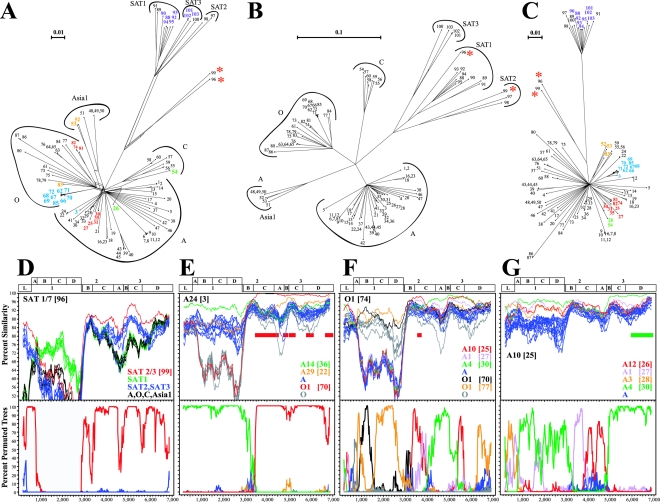

FIG. 4.

FMDV phylogenetic and recombination analysis. (A) One hundred three FMDV genomes were aligned with ClustalW and visually screened for reticulated branching patterns by split decomposition cluster analysis, using SplitsTree with Hamming distances. Numbers at terminal nodes correspond to the isolates presented in Table 1, arcs and labels indicate serotype-specific groups, similar colors indicate isolates exhibiting obvious interserotypic relationships, red stars indicate SAT viruses with unique nonstructural protein sequences, and bars represent estimated distances. Similar results were obtained with alternative corrections for multiple substitution (data not shown). Subgenomic split decomposition analysis was conducted on structural protein (1A to 1D) (B) and nonstructural protein (Lpro and 2A to 3D) (C) coding regions aligned with Dialign. (D to G) Similarity (upper box) and bootscanning (lower box) plots were generated with a query isolate against reference isolates aligned with Dialign, indicating corrected percent similarities and bootstrap frequencies as percentages of permuted trees, respectively. Polyprotein schematics are shown above the similarity plots. Query isolates are indicated at the left within similarity plots and included the following: (D) SAT 1/7 Isrl 4/62 (no. 96), (E) A24 Argentina/65 (no. 3), (F) O1 M11 (no. 74), and (G) A10 Holland/42 (no. 25). Reference isolates are indicated individually or as groups in color, as labeled at the right within similarity plots, and included the following: (D) red, SAT 2/3 Kenya 11/60 (no. 99); green, SAT1 viruses (no. 88 to 95); blue, SAT2 and SAT3 viruses (no. 97 and 98 and 100 to 103, respectively); black, A viruses (no. 30, 38, and 46), O viruses (no. 80 and 86), C viruses (no. 57), and Asia1 viruses (no. 51); (E) green, A14 Spain/59 (no. 36); orange, A29 Peru/69 (no. 22); blue, A viruses (no. 2, 10, 18, 19, 22, 25, 27, 30, 38, 39, 42, 46, and 47); red, O1 Campos/58 (no. 70); gray, O viruses (no. 74, 78, 80, 83, and 87); (F) red, A10 Holland/42 (no. 25); pink, A1 Bayern/Bavaria (no. 27); green, A4 WG/72 (no. 30); blue, A viruses (no. 2, 10, 18, 19, 22, 38, 39, 42, 46, 47); black O1 Campos/58 (no. 70); orange, O1 Vallee/39 (no. 77); gray, O viruses (no. 63, 75, 77, 78, 80, 83, 87); (G) red, A12 Valle Strain 119 (no. 26); pink, A1 Bayern/Bavaria (no. 27); orange, A3 Mecklenburg/68 (no. 28); green, A4 WG/72 (no. 30); blue, A viruses (no. 2, 3, 5, 10, 13, 17, 19, 21, 22, 29, 32, 33, 36 to 39, 41, 46, and 47). Aligned polyprotein-encoding nt positions are indicated below the bootscan plots. Colored bars within similarity plot boxes indicate fragments identified by GENECONV as having significant global permutation values (P < 0.05) shared between the query sequence and particular reference sequences.

The data from analyses of individual protein-encoding regions indicated that incongruent tree topologies exist for different genomic regions (data not shown). An analysis of 1B, 1C, 1D, or all of the structural protein-encoding regions together indicated few obvious phylogenetic incongruities, placing viruses into serotypic, temporal, and/or geographic groups (Fig. 4B and data not shown). In general, analyses of the entire structural protein-encoding region improved bootstrap/confidence values relative to 1D analysis alone (data not shown). Conversely, analyses of the 5′ UTR and regions encoding individual or all nonstructural proteins failed to produce the serotype-inclusive groups observed with capsid protein sequences, often yielding unresolved, star-like topologies among diverse serotypes (Fig. 4C and data not shown). Consistent with the complex relationships illustrated in Fig. 4A, analyses of nonstructural protein-encoding regions indicated groupings of serotypically disparate viruses, which extended previous but limited data (54, 110, 113) (Fig. 4C). Similarity plots and bootscanning analysis further indicated that several of these interserotypically related viruses contained nonstructural protein-encoding regions most similar to those of viruses with divergent capsid protein-encoding sequences, suggesting the occurrence of intertypic recombination during the history of these lineages (Fig. 4D to F and data not shown). Examples of potential intratypic recombination were also noted, more obviously in nonstructural protein-encoding regions but also in structural protein-encoding regions, as has been suggested previously (Fig. 4F and G and data not shown) (35, 109).

Taken together, these data suggest that FMDV capsid protein sequences may undergo intertypic recombination infrequently relative to that in other genomic regions, which conceivably undergo complex recombination events and fail to display serotype-specific phylogenetic relationships. These observations are consistent with and extend previous reports of FMDV recombination, which has been inferred from incongruent Lpro, 3Cpro, and 1D topologies and observed (and suggested to predominate) in C-terminal genomic regions (52, 57, 101, 113). Similar observations have recently been made for enterovirus genomes, which were suggested to undergo relatively extensive recombination in nonstructural gene regions while generally maintaining serospecific monophyly (79). These observations, including the inability to reliably define viral relationships based on nonstructural protein-encoding sequences and data suggestive of recombination, raise interesting questions about FMDV genome evolution in nature and the relative contribution of recombination to the generation of FMDV genetic and population diversity.

Notably, the analysis described here identified a novel SAT lineage represented by SAT1-7 Isrl 4/62 and SAT2-3 Kenya 11/60, which contain nonstructural protein-encoding regions that are divergent from each other but are also clearly distinct from those of the other SAT and Euroasiatic lineages presented here (Fig. 4C). The distinct nature of nonstructural proteins from these structurally/serotypically SAT-like viruses was supported by a previously available genome sequence similar to that of SAT2-3 Kenya (SAT2 Ken/3/57; 97% overall nucleotide identity) (Table 1) and by previous data indicating that the SAT2 Ken/3/57 Lpro- and 3C-encoding regions may be distinct from those of other SATs (102). Taken together, these results suggest that more FMDV genome diversity may exist in nature than is currently indicated by serology or 1D sequence analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Lubroth for providing FMDV isolates and A. Lakowitz and A. Zsak for providing excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jvi.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acharya, R., E. Fry, D. Stuart, G. Fox, D. Rowlands, and F. Brown. 1990. The structure of foot-and-mouth disease virus: implications for its physical and biological properties. Vet. Microbiol. 23:21-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acharya, R., E. Fry, D. Stuart, G. Fox, D. Rowlands, and F. Brown. 1989. The three-dimensional structure of foot-and-mouth disease virus at 2.9 Å resolution. Nature (London) 337:709-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afonso, C. L., E. R. Tulman, Z. Lu, E. Oma, G. F. Kutish, and D. L. Rock. 1999. The genome of Melanoplus sanguinipes entomopoxvirus. J. Virol. 73:533-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agol, V. I., A. V. Paul, and E. Wimmer. 1999. Paradoxes of the replication of picornaviral genomes. Virus Res. 62:129-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambros, V., and D. Baltimore. 1978. Protein is linked to the 5′ end of poliovirus RNA by a phosphodiester linkage to tyrosine. J. Biol. Chem. 253:5263-5266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]