Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Characterization of emergency department (ED) visits for acute harms related to use of over-the-counter cough and cold medications (CCMs) by patient demographics, intent of CCM use, concurrent substance use, and clinical manifestations can help guide prevention of medication harms.

Methods:

Public health surveillance data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project were used to estimate numbers and population rates of ED visits from 2017-2019.

Results:

Based on 1,396 surveillance cases, there were an estimated 26,735 (95% CI, 21,679-31,791) US ED visits for CCM-related harms annually, accounting for 1.3% (95% CI, 1.2%-1.5%) of all ED visits for medication adverse events. Three fifths (61.4%, 95% CI, 55.6%-67.2%) of these visits were attributed to non-therapeutic CCM use (nonmedical use, self-harm, unsupervised pediatric exposures). Most visits by children aged <4 years (74.0%, 95% CI, 59.7%-88.3%) were for unsupervised CCM exposures. Proportion hospitalized was higher for visits for self-harm (76.5%, 95% CI, 68.9%-84.2%) than for visits for nonmedical use (30.3%, 95% CI, 21.1%-39.6%) and therapeutic use (8.8%, 95% CI, 5.9%-11.8%). Overall, estimated population rates of ED visits for CCM-related harms were higher for patients aged 12-34 years (16.5 per 100,000, 95% CI, 13.0-20.0) compared with patients aged <12 years (5.1 per 100,000, 95% CI, 3.6–6.5) and ≥35 years (4.3 per 100,000, 95% CI, 3.4-5.1). Concurrent use of other medications, illicit drugs, or alcohol was frequent in ED visits for nonmedical use (61.3%) and self-harm (75.9%).

Conclusions:

Continued national surveillance of CCM-related harms can assess progress toward safer use.

Keywords: cough and cold medication, adverse drug event, nonmedical drug use, unsupervised exposure, medication safety

Over-the-counter (OTC) cough and cold medications (hereafter CCMs) are frequently used for relief of upper respiratory infection symptoms.1 In 2019, Americans spent >$9 billion to purchase 1.2 billion bottles or packages of OTC upper respiratory medications, many of which are marketed for treating coughs and colds.2 Many CCMs have multiple active ingredients including nasal decongestants, cough suppressants, expectorants, and antihistamines; some also contain analgesics.3 When used as directed, the risk of severe adverse events related to CCMs is generally considered to be low.1,4 However, when not used as directed, the risk of severe adverse events may be higher, as some CCM ingredients can cause serious harm in large overdoses.5 CCMs have been identified in studies of adverse drug reactions, drug-drug interactions, drug overdoses, and unsupervised pediatric exposures.4–9

Targeted efforts to reduce specific types of CCM-related harms began decades ago. Since 1997, geriatric professional societies have recommended that older adults avoid certain active ingredients in CCMs.10 In the 2000s, to reduce CCM misuse among teens, some states implemented age restriction laws for purchasing dextromethorphan-containing products; educational efforts were also initiated.11 Since 2008, nearly all US manufacturers have removed infant OTC CCM products and added warnings not to use CCMs in children aged <4 years.12,13 In 2015, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended that bottles of OTC pediatric liquid medications containing acetaminophen, including CCMs, should have supplemental child safety features to reduce risks of dosing errors and unintended access (unsupervised exposure) by young children.14

We used nationally representative public health surveillance data to estimate the numbers and population rates of emergency department (ED) visits for acute CCM-related harms by patient demographics, intent of drug use, concurrent substance use, and clinical manifestations.

Methods

Data Source

We used data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance (NEISS-CADES) project, a collaboration of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), and FDA, to generate national estimates of ED visits for acute harms from CCM use. NEISS-CADES is an active public health surveillance system based on a nationally representative, stratified probability sample of 60 hospitals in the United States and its territories with at least 6 beds and a 24-hour ED.7,15 Data collection from NEISS-CADES hospitals was reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.*

Trained data abstractors review medical records of every ED visit to identify harms (adverse events) from medications used for any reason based on clinician documentation, including adverse reactions to therapeutic doses, medication errors, unsupervised exposures by children, overdoses of any kind, and secondary injuries attributed to medications (e.g., choking on a pill). An adverse event case was defined as an incident ED visit for a condition or harm that the treating clinician explicitly attributed to the use of a drug or a drug-specific effect as recorded in the medical record. Abstractors record up to 4 implicated medications and intent of use, clinician diagnoses, free-text narratives of the event (including clinical manifestations, relevant preceding events, concurrent illicit drug or alcohol use), laboratory testing, treatments administered, and discharge disposition. Two clinician reviewers at CDC review free-text narratives for every case and code clinical manifestations and implicated medications based on the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, version 9.1, and a modified version of the Veterans Administration National Drug File, respectively.

Definitions

Cases in which an OTC cough and cold medication (CCM) was implicated from January 1, 2017 through December 31, 2019 were selected for study. CCMs included orally administered OTC products containing decongestants, antitussive agents, and/or expectorants alone or in combination and/or with analgesics or antihistamines. Clinicians’ assessment of patients’ intent of CCM use was classified as therapeutic (used as directed or unintentional errors) or non-therapeutic. Non-therapeutic use included: (1) unsupervised exposures by children aged ≤10 years, (2) self-harm (using medication to intentionally injure oneself), or (3) nonmedical use. Nonmedical use included abuse (clinician diagnosis of abuse or documentation of recreational use; e.g., “to get high”), misuse (using medication for symptom relief, but not using as directed; e.g., taking someone else’s prescription medication or taking additional doses for greater effect), or overdoses without documentation of therapeutic intent, misuse, abuse, or self-harm (e.g., patients found unresponsive or unwilling to describe circumstances or intent). Although concern has been raised that the term ‘abuse’ may contribute to stigma,16,17 it is employed here because it remains commonly used by clinicians in medical documentation.

Statistical Analysis

To calculate national estimates of ED visits, CPSC weights cases based on the inverse probability of selection, adjusted for nonresponse and post-stratified to adjust for changes in the total number of hospital ED visits annually.18,19 National estimates of ED visits with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the SURVEYMEANS procedure in SAS version 9.4 to account for the sample weights and complex sample design. Estimated numbers of ED visits and corresponding 95% CIs for the 3-year period were divided by 3 to obtain average annual estimates. Estimates based on <20 cases or total estimates <1,200 are considered statistically unstable and are not shown. Estimates with coefficients of variation >30% may be considered statistically unstable and are noted. Intercensal estimates from the US Census Bureau were used to estimate rates of ED visits by age.20

Results

Based on 1,396 NEISS-CADES surveillance cases, there were an estimated 26,735 (95% CI, 21,679-31,791) ED visits for CCM-related harms in the United States annually from 2017 through 2019, accounting for 1.3% (95% CI, 1.2%-1.5%) of the total number of ED visits for medication-related harms (Table 1). Two fifths (38.6%, 95% CI, 32.8%-44.4%; 10,319 annually, 95% CI, 7,887-12,752) were visits attributed to therapeutic CCM use, while three fifths (61.4%, 95% CI, 55.6%-67.2%; 16,415 annually, 95% CI, 12,878-19,952) were attributed to non-therapeutic CCM use. Non-therapeutic visits included 7,870 (95% CI, 5,757-9,982) visits annually for nonmedical use, 7,382 (95% CI, 5,706-9,058) visits annually for self-harm, and 1,164 (95% CI, 834-1,494) visits annually for unsupervised CCM exposures by children aged 10 or younger.

Table 1.

National Estimates of Emergency Department (ED) Visits for Over-the-Counter (OTC) Cough and Cold Medication (CCM)-related Harms, by Patient and Case Characteristics, 2017-2019a

| Characteristic | Therapeutic Use | Non-therapeutic Useb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Annual Estimate | Cases | Annual Estimate | |||||

| No. | No. | % | 95% CI | No. | No. | % | 95% CI | |

| Age (Years) | ||||||||

| <4 | 13 | -- | -- | -- | 74 | 776 | 4.7 | (2.9 - 6.5) |

| 4 - 11 | 60 | 951 | 9.2 | (5.2 - 13.3) | 34 | 559 | 3.4 | (1.8 - 5.0) |

| 12 - 17 | 50 | 1,181 | 11.4 | (7.3 - 15.6) | 279 | 3,657 | 22.3 | (15.7 - 28.9) |

| 18 - 24 | 65 | 1,419 | 13.8 | (9.6 - 17.9) | 193 | 3,694 | 22.5 | (18.8 - 26.2) |

| 25 - 34 | 62 | 1,730 | 16.8 | (13.1 - 20.4) | 232 | 5,005 | 30.5 | (23.3 - 37.7) |

| 35 - 44 | 59 | 1,338 | 13.0 | (9.0 - 16.9) | 51 | 1,066 | 6.5 | (4.6 - 8.4) |

| 45 - 54 | 46 | 1,182 | 11.5 | (8.9 - 14.0) | 51 | 1,066 | 6.5 | (4.3 - 8.7) |

| 55 - 64 | 33 | 675 | 6.5 | (4.0 - 9.1) | 13 | -- | -- | -- |

| ≥65 | 66 | 1,677 | 16.2 | (12.3 - 20.2) | 15 | -- | -- | -- |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 270 | 6,307 | 61.1 | (55.8 - 66.4) | 410 | 7,289 | 44.4 | (38.1 - 50.7) |

| Male | 184 | 4,012 | 38.9 | (33.6 - 44.2) | 532 | 9,126 | 55.6 | (49.3 - 61.9) |

| Disposition c | ||||||||

| Hospitalized | 38 | 912 | 8.8 | (5.9 - 11.8) | 510 | 8,194 | 49.9 | (42.9 - 56.9) |

| Treated/released or left against medical advice | 416 | 9,407 | 91.2 | (88.2 - 94.1) | 430 | 8,163 | 49.7 | (42.4 - 57.1) |

| Type of non-therapeutic use | ||||||||

| Nonmedical use | NA | NA | NA | NA | 432 | 7,870 | 47.9 | (43.0 - 52.9) |

| Self-harm | NA | NA | NA | NA | 417 | 7,382 | 45.0 | (40.3 - 49.6) |

| Unsupervised pediatric exposure | NA | NA | NA | NA | 93 | 1,164 | 7.1 | (4.8 - 9.3) |

| No. of implicated medications | ||||||||

| 1 | 345 | 7,959 | 77.1 | (72.2 - 82.0) | 593 | 9,930 | 60.5 | (55.6 - 65.4) |

| 2 | 85 | 1,873 | 18.2 | (13.8 - 22.5) | 199 | 3,809 | 23.2 | (18.1 - 28.3) |

| 3 | 11 | -- | -- | -- | 92 | 1,706 | 10.4 | (7.3 - 13.5) |

| 4 or more | 13 | -- | -- | -- | 58 | 970 | 5.9 | (3.6 - 8.2) |

| Total | 454 | 10,319 | 100.0 | 942 | 16,416 | 100.0 | ||

CI = confidence interval. NA = not applicable.

Estimates are from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimates based on <20 cases or total estimates <1200 for the study period are considered statistically unstable and are not shown (--).

Non-therapeutic use includes unsupervised exposures by patients aged ≤10 years, self-harm, and nonmedical use (i.e., abuse [clinician diagnosis of abuse or documentation of recreational use], misuse [using medication for symptom relief, but not using medication as directed], and overdoses without documentation of therapeutic intent, misuse, abuse, or self-harm).

Missing for 2 cases of ED visits for harms from non-therapeutic CCM use.

Considering ED visits for both therapeutic and non-therapeutic CCM use combined, 62.4% (95% CI, 59.0%-65.8%) involved patients aged 12-34 years. Among these patients aged 12-34 years, 74.1% (95% CI, 68.4%-79.7%) of ED visits for CCM-related harms involved non-therapeutic use, compared with 45.8% (95% CI, 35.0%-56.7%) among patients aged 35-54 years, and 20.1% (95% CI, 11.7%-28.6%) among patients aged 55 years or older. Three fourths (74.0%, 95% CI, 59.7%-88.3%) of visits for CCM harms among children aged <4 years were for unsupervised exposures.

An estimated 61.1% (95% CI, 55.8%-66.4%) of ED visits for harms after therapeutic use of CCMs involved females compared with 44.4% (95% CI, 38.1%-50.7%) of ED visits after non-therapeutic use of CCMs. Among visits for non-therapeutic use of CCMs, most ED visits for nonmedical use (68.1%, 95% CI, 60.5%-75.7%) and unsupervised pediatric exposures (62.9%, 95% CI, 46.0%-79.9%) involved male patients, whereas most visits for CCM-related self-harm (58.9%, 95% CI, 50.7%-67.1%) involved female patients (Supplement 1). The proportion of ED visits for CCM harms that resulted in hospitalization was highest for visits due to self-harm (76.5%, 95% CI, 68.9%-84.2%), and was significantly lower for visits due to nonmedical use (30.3%, 95% CI, 21.1%-39.6%), and therapeutic use (8.8%, 95% CI, 5.9%-11.8%).

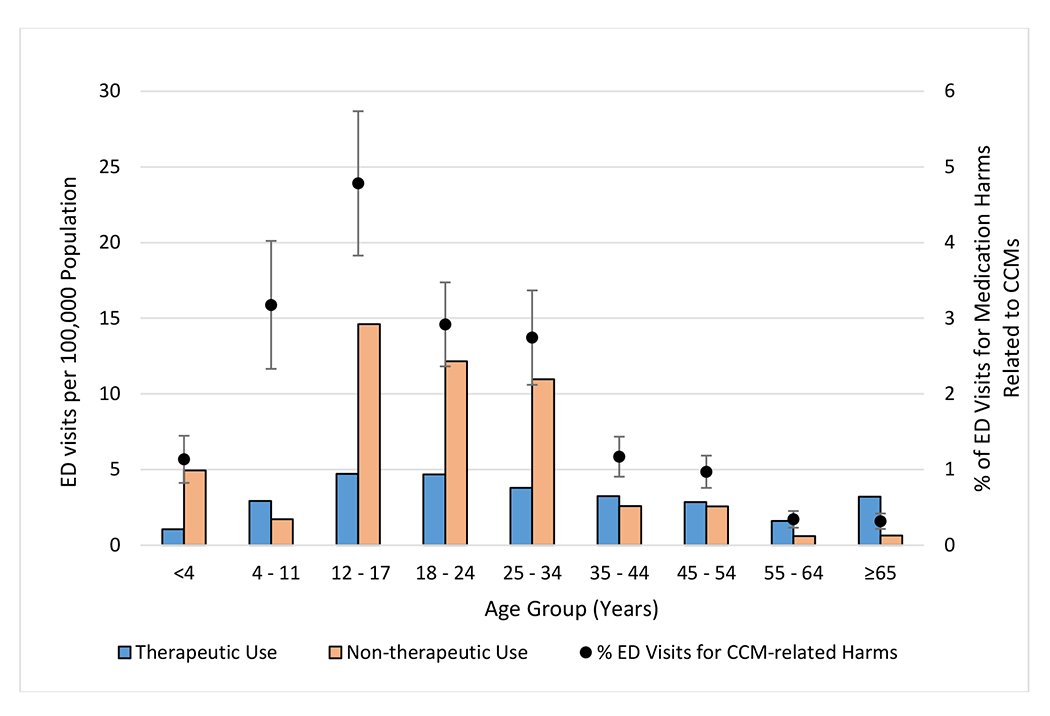

Overall, the estimated proportion of all ED visits for acute medication harms that involved CCMs varied by age, from 1.1% (95% CI, 0.8%-1.4%) among patients aged <4 years, increasing to 4.8% (95% CI, 3.8%-5.7%) among patients aged 12-17 years, then declining to 0.3% among patients aged 55-64 years (95% CI, 0.2%-0.5%) and ≥65 years (95% CI, 0.2%-0.4%) (Figure 1). Including both therapeutic use and non-therapeutic use combined, the estimated population rate of ED visits for CCM-related harms was highest for patients aged 12-34 years (16.5 per 100,000, 95% CI, 13.0-20.0), and significantly lower for patients aged <12 years (5.1 per 100,000, 95% CI, 3.6-6.5) and ≥35 years (4.3 per 100,000, 95% CI, 3.4-5.1). Among patients aged 12-34 years, the population rate of ED visits for non-therapeutic use of CCMs (12.2 per 100,000, 95% CI, 9.4-15.1) was 3-fold higher than the population rate for therapeutic use (4.3 per 100,000, 95% CI, 3.1-5.5) and 8-fold higher than the population rate for non-therapeutic use (1.5 per 100,000, 95% CI, 1.1-2.0) among patients aged ≥35 years.

Figure 1: Estimated Rate and Proportion of Emergency Department (ED) Visits for Over-the-Counter (OTC) Cough and Cold Medication (CCM)-Related Harms, by Age Group and Intent of Use, 2017-2019.

Abbreviations: CCM = cough and cold medication; ED = emergency department. Estimates of ED visits for medication harms are from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; population estimates are from the US Census Bureau. Non-therapeutic use includes unsupervised exposures by patients aged ≤10 years, self-harm, and nonmedical use (i.e., abuse [clinician diagnosis of abuse or documentation of recreational use], misuse [using medication for symptom relief, but not using medication as directed], and overdoses without documentation of therapeutic intent, misuse, abuse, or self-harm). “% of ED visits for medication harms related to CCMs” corresponds to the proportion of ED visits for CCM-related harms in the specified age group of all ED visits for medication harms in that age group. The estimated proportion of ED visits for medication harms that were related to CCMs for each age group is shown with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. The estimated numbers of ED visits for harms attributed to therapeutic CCM use among patients aged <4 years and non- therapeutic CCM use among patients aged 55-64 years and ≥65 years were based on <20 cases and are therefore considered statistically unstable.

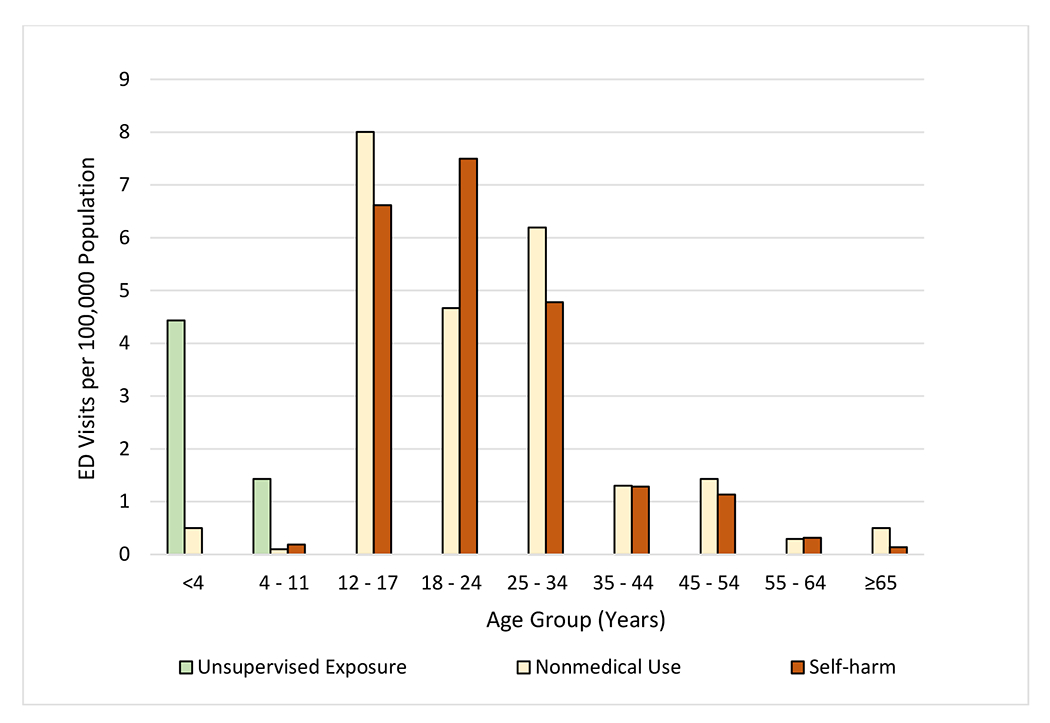

When categorized by type of non-therapeutic use, population rates of ED visits also varied by patient age (Figure 2). Estimated population rates of ED visits for nonmedical use of CCMs peaked at 8.0 (95% CI, 3.7-12.3) per 100,000 patients aged 12-17 years; for self-harm, rates peaked at 7.5 (95% CI, 5.5-9.5) per 100,000 patients aged 18-24 years. An estimated 4.4 (95% CI, 2.6-6.3) ED visits per 100,000 children aged <4 years involved unsupervised CCM exposures; most were due to ingestion of liquid CCM products (64.0%, 95% CI, 50.1%-77.9%).

Figure 2: Estimated Rate of Emergency Department (ED) Visits for Harms Related to Non-therapeutic Use of Over-the-Counter (OTC) Cough and Cold Medications (CCMs), by Age Group and Type of Non-therapeutic Use, 2017-2019.

Abbreviations: CCM = cough and cold medication; ED = emergency department. Estimates of ED visits for medication harms are from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; population estimates are from the US Census Bureau. Nonmedical use includes abuse (clinician diagnosis of abuse or documentation of recreational use), misuse (using medication for symptom relief, but not using medication as directed), and overdoses without documentation of therapeutic intent, misuse, abuse, or self-harm. The estimated numbers of ED visits for harms attributed to nonmedical CCM use among patients aged <4 years, 4-11 years, 55-64 years, and ≥65 years, and CCM-related self-harm among patients aged 4-11 years, 55-64 years, and ≥65 years were based on <20 cases and are therefore considered statistically unstable. There were no cases involving self-harm among children aged <4 years or unsupervised exposures among patients aged >11 years. The coefficient of variation for the estimate of nonmedical CCM use among patients aged 35-44 years is >30% and may be considered statistically unstable.

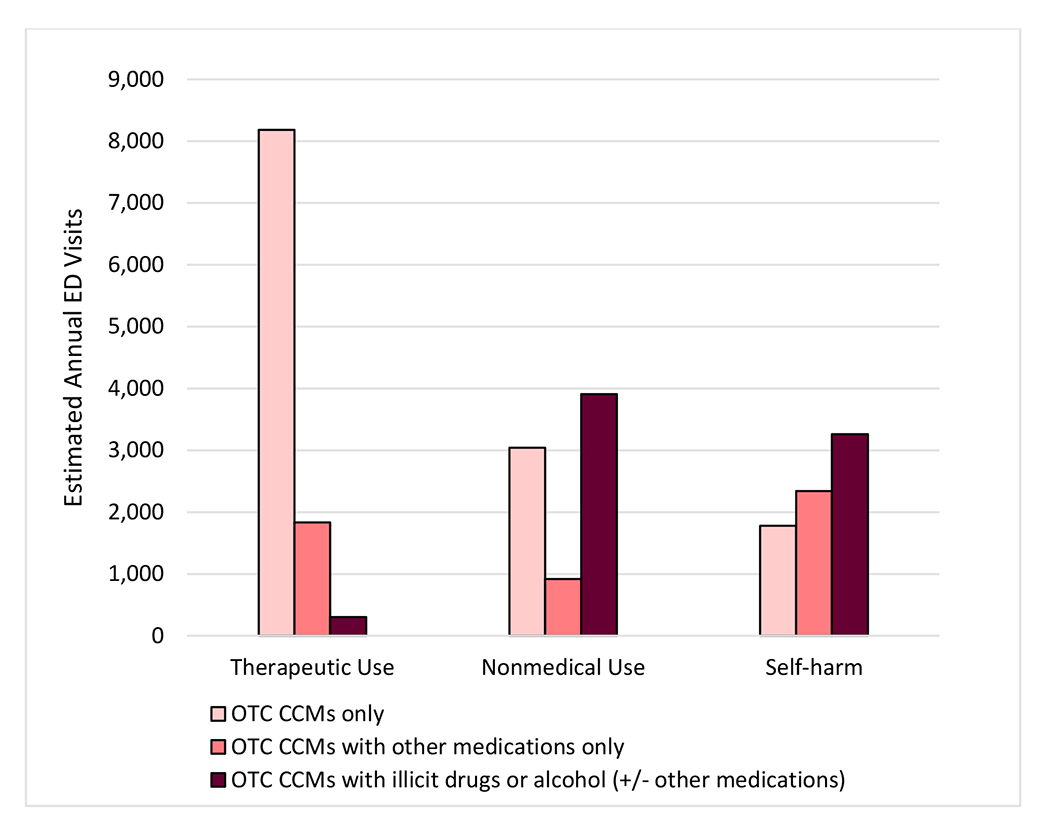

Most ED visits attributed to therapeutic CCM use (79.3%, 95% CI, 74.3%-84.3%) did not involve other types of substances, and 17.7% (95% CI, 13.1%-22.4%) involved only other medications (Figure 3). On the other hand, three fifths of ED visits involving nonmedical CCM use (61.3%, 95% CI, 52.7%-70.0%) and three fourths of visits for CCM-related self-harm (75.9%, 95% CI, 69.4%-82.5%) involved concurrent use of illicit drugs, alcohol, and/or other medications.

Figure 3: Annual National Estimates of Emergency Department (ED) Visits for Over-the-Counter (OTC) Cough and Cold Medication (CCM)-related Harms, by Concurrent Substances, 2017-2019.

Abbreviations: CCM = cough and cold medication; ED = emergency department; OTC = over-the-counter. Estimates of ED visits for medication harms are from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nonmedical use includes abuse (clinician diagnosis of abuse or documentation of recreational use), misuse (using medication for symptom relief, but not using medication as directed), and overdoses without documentation of therapeutic intent, misuse, abuse, or self-harm. Illicit drugs include specified illicit substances (e.g., heroin, cocaine), as well as unspecified opioids and unspecified amphetamines (e.g., documentation of opioid ingestion, but unclear whether prescription opioids or illicit opioids were taken). The estimated number of ED visits for harms attributed to therapeutic CCM use involving illicit drugs or alcohol (+/− other medications) is based on <20 cases and is therefore considered statistically unstable. ED visits for unsupervised pediatric CCM exposures are not shown (1,164 estimated visits annually).

Although it was not common for another class of medication to be involved in ED visits for harms from therapeutic CCM use, antibiotics were most commonly co-implicated (5.1%,95% CI, 2.7%-7.5%) (Supplement 2). One in 10 ED visits for nonmedical CCM use (11.0%, 95% CI, 6.0%-15.9%), involved benzodiazepines. Over half of ED visits for CCM-related self-harm also involved other types of medication, most frequently medications commonly available over-the-counter (non-opioid acetaminophen-containing analgesics [16.6%, 95% CI, 12.7%- 20.6%], antihistamines [13.8%, 95% CI, 10.1%-17.5%], and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [11.8%, 95% CI, 9.3%-14.4%]), and psychiatric medications (antidepressants [7.9%, 95% CI, 4.2%-11.5%] and benzodiazepines [7.7%, 95% CI, 4.2%-11.2%]).

Alcohol was involved in 20.8% (95% CI, 15.0%-26.7%) of ED visits for nonmedical use of CCMs and 24.7% (95% CI, 17.8-31.6%) of ED visits for self-harm involving CCMs (Supplement 2). Illicit substances were involved in over one third of ED visits (39.1%, 95% CI, 28.4%-49.9%) involving nonmedical use of CCMs and over one-quarter of ED visits (27.3%, 95% CI, 22.5%-32.1%) for self-harm involving CCMs. Marijuana was the most commonly documented concurrent illicit substance in ED visits due to both nonmedical CCM use (24.3%, 95% CI, 15.3%-33.2%) and self-harm (19.6%, 95% CI, 15.5%-23.7%). Illicit stimulants (including cocaine, methamphetamine, or unspecified amphetamines) were involved in 13.6% (95% CI, 8.8%-18.4%) of ED visits involving nonmedical CCM use, and 7.8% (95% CI, 4.5%-11.2%) involving CCM-related self-harm.

An estimated two fifths of ED visits for therapeutic CCM use involved allergic reactions (27.8% mild-to-moderate and 12.3% severe reactions) (Table 2). Similar proportions of ED visits for therapeutic CCM use involved syncope, presyncope, falls or other injuries (13.2%), psychiatric or other central nervous system effects (12.4%), altered mental status or unresponsiveness (11.9%), and cardiovascular effects (11.9%). The most common manifestation documented in ED visits for nonmedical CCM use was altered mental status or unresponsiveness (44.9%); however, 73.9% (95% CI, 62.8%-84.9%) of these visits also involved concurrent use of alcohol, illicit drugs, or other medications. Psychiatric or other central nervous system effects were documented in 7.5% of ED visits for nonmedical CCM use, and in 29.9% of visits for nonmedical CCM use, no clinical manifestations were specified (e.g., patient with documented overdose but specific symptoms were not documented). Nearly three fifths (58.0%) of ED visits involving CCM-related self-harm had no documented manifestations and in 9.7% of visits, increased drug levels were the only manifestation documented. One fifth (21.4%) of visits for CCM-related self-harm involved altered mental status or unresponsiveness, of which 82.0% (95% CI, 73.9%-90.2%) involved concurrent use of alcohol, illicit drugs, or other medications. Altered mental status or unresponsiveness was documented twice as frequently in ED visits involving OTC CCMs with other substances compared with those involving OTC CCMs alone (34.1%, 95% CI, 27.7%-40.5% vs. 15.6%, 95% CI, 11.9%-19.4%) (Supplement 3).

Table 2.

National Estimates of Emergency Department (ED) Visits for Over-the-Counter (OTC) Cough and Cold Medication (CCM)-related Harms, by Clinical Manifestations, 2017-2019a

| Manifestationsb | Therapeutic Use | Nonmedical Usec | Self-harm | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Annual Estimate | Cases | Annual Estimate | Cases | Annual Estimate | |||||||

| No. | No. | % | 95% CI | No. | No. | % | 95% CI | No. | No. | % | 95% CI | |

| Severe allergic reaction | 56 | 1,271 | 12.3 | (8.7 - 15.9) | 1 | -- | -- | -- | 0 | -- | -- | -- |

| Altered mental status/unresponsiveness | 54 | 1,227 | 11.9 | (8.2 - 15.6) | 199 | 3,533 | 44.9 | (37.3 - 52.5) | 75 | 1,583 | 21.4 | (13.5 - 29.4) |

| Presyncope/syncope/fall/injury | 61 | 1,367 | 13.2 | (9.1 - 17.4) | 20 | -- | -- | -- | 11 | -- | -- | -- |

| Psychiatric or other central nervous system effect | 50 | 1,275 | 12.4 | (8.9 - 15.9) | 34 | 591 | 7.5 | (4.6 - 10.4) | 9 | -- | -- | -- |

| Cardiovascular effect | 44 | 1,229 | 11.9 | (8.2 - 15.6) | 15 | -- | -- | -- | 11 | -- | -- | -- |

| Mild-to-moderate allergic reaction | 132 | 2,872 | 27.8 | (23 - 32.6) | 1 | -- | -- | -- | 0 | -- | -- | -- |

| Other effect | 33 | 694 | 6.7 | (3.3 - 10.1) | 20 | 470d | 6.0 | (2.4 - 9.5) | 32 | -- | -- | -- |

| Increased drug level only | 1 | -- | -- | -- | 4 | -- | -- | -- | 43 | 717 | 9.7 | (6.7 - 12.7) |

| No documented clinical manifestations | 23 | -- | -- | -- | 138 | 2,349 | 29.9 | (22 - 37.7) | 236 | 4,278 | 58.0 | (49.1 - 66.8) |

| Total | 454 | 10,319 | 100.0 | 432 | 7,870 | 100.0 | 417 | 7,382 | 100.0 | |||

CI = confidence interval.

Estimates are from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimates based on <20 cases or total estimates <1200 for the study period are considered statistically unstable and are not shown (--). ED visits for unsupervised pediatric CCM exposures are not shown (1,164 estimated visits annually). There we no documented clinical manifestations for 74.1% of ED visits for unsupervised CCM exposures among children aged ≤10 years.

Clinical manifestations were categorized in a mutually exclusive and hierarchical manner (e.g., a case involving depressed consciousness and nausea would be classified as altered mental status/unresponsiveness based on the depressed consciousness). An estimated 61.3% of ED visits for nonmedical CCM use and 75.9% of visits for CCM-related self-harm had documentation of concurrent use of other medications, alcohol, or illicit drugs, and therefore it may be difficult to assess the role that the CCM played in the clinical manifestations, particularly for ED visits for harms involving non-therapeutic CCM use.

Nonmedical use includes abuse (clinician diagnosis of abuse or documentation of recreational use), misuse (using medication for symptom relief, but not using medication as directed), and overdoses without documentation of therapeutic intent, misuse, abuse, or self-harm.

Coefficient of variation >30%.

Discussion

From 2017-2019, there were an estimated 26,735 ED visits each year in the United States for harms from OTC CCM use, with most visits (61%) involving non-therapeutic CCM use. Preventive interventions could be directed toward the most common situations leading patients to seek urgent medical care at each life stage.

Significant progress has been made in reducing ED visits for CCM-related harms in young children,21,22 and continued child safety improvements have potential to further reduce these ED visits.23,24 In the 2000s, it was estimated that 1 in every 16 (6.4%) ED visits for acute medication harms among children aged <4 years involved CCMs, with 77% involving OTC CCMs.22 Since then, nearly all infant CCM products have been removed from the market,13,22CCM labeling was changed to recommend against use in children <4 years of age,13 and a 2015 FDA voluntary guidance recommended that container features, such as flow restrictors, be added to all OTC pediatric liquid acetaminophen-containing products, including CCMs, to limit unsupervised ingestion by children.14 The finding that from 2017-2019 OTC CCMs were implicated in fewer than 1 in 91 (1.1%) ED visits for acute medication harms among children aged <4 years, with nearly three-quarters attributed to unsupervised exposures, suggests safety changes to reduce CCM-related harms in young children have been impactful. In a 2020 draft guidance, FDA expanded recommendations for flow restrictors to other medications, not just those containing acetaminophen, with the OTC CCM ingredients diphenhydramine, dextromethorphan, and pseudoephedrine specifically identified.25 Adding flow restrictors to bottles of liquid acetaminophen has been shown to reduce the quantity of ingestions26-28 and calls to poison centers,28,29 and adding flow restrictors to all pediatric liquid CCM products is likely to reduce ED visits in this age group even further. Nonetheless, because a new generation of parents are now caring for young children and misunderstanding of warnings and label instructions can still occur,30 it will continue to be important to reinforce caregiver awareness to avoid using CCMs in children aged <4 years and to keep medications out of reach and sight of young children.31

While the numbers and rates of ED visits for many types of adverse drug events increase with age, over 60% of ED visits for harms from CCMs involved patients aged 12-34 years, with a population rate 2.5 times higher than other age groups. Further, three fourths (74%) of visits among patients aged 12-34 years involved non-therapeutic CCM use, suggesting targeted prevention opportunities. Adolescents and young adults have been shown to be at an increased risk for substance abuse/misuse and self-harm,32,33 and cultural representations and endorsement of use of CCMs mixed with soft drinks or alcohol by musicians and celebrities popular with teenagers and young adults (e.g., purple drank, lean) may encourage nonmedical CCM use.34 In 2010 the Consumer Healthcare Products Association adopted a multifaceted approach to reduce dextromethorphan misuse and abuse by teens, and these efforts coincided with a decrease in OTC CCM abuse after 2010.11 However, data from more recent years show that the decline in reported OTC CCM abuse has slowed and now may be reversing.35,36 In 2019, >2.5% of US teens reported misusing OTC CCMs in the past year.35

Expanding current primary and secondary prevention interventions may help to reduce acute harms from nonmedical CCM use. Icons warning of the risk of abuse have been added to dextromethorphan packaging,11 and at least 20 states have implemented laws prohibiting the sale of dextromethorphan-containing products to minors.37 Secondary prevention efforts include parental education on CCM abuse/misuse and potential for harm and monitoring within the home.38 The findings that three fifths of ED visits for nonmedical use of CCMs and three fourths of visits for CCM-related self-harm also involved alcohol, illicit drugs, or other medications, suggests that interventions to prevent these visits may need to address non-therapeutic use of CCMs in the context of polysubstance use. Interventions that target children before they enter young adulthood, such as school and family based programs, have been shown to have positive long-term effects in preventing alcohol and drug misuse.39,40 Programs teaching children and adolescents about safe medication use,41 as well as coping and problem solving skills can also reduce both substance use and suicide later in life.42 CDC’s Preventing Suicide: A Technical Package of Policy, Programs, and Practices, outlines seven core strategies aimed at preventing suicide, such as strengthening access and delivery of care, and creating protective environments.42

Reducing CCM harms among older patients should focus on therapeutic CCM use, which accounted for >80% of ED visits for CCM harms among patients aged ≥65 years, with another medication co-implicated in nearly one-quarter of estimated visits. The 2019 Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use from the American Geriatrics Society identifies some first generation antihistamine-containing CCMs as inappropriate for geriatric use and further advises caution in using dextromethorphan-containing products due to potential drug-drug interactions.10 Clinicians should inquire about CCM and other OTC medication use by their older adult patients, assess for interactions with prescribed medications, and advise careful review of product warnings, precautions, and administration instructions.43

Public health surveillance data have limitations. First, not all harmful effects from CCM use are addressed, as only acute harms treated in EDs are included. Acute harms diagnosed and treated at primary care or urgent care visits are not included. Long-term complications are likely underestimated as they may not be diagnosed in the ED but only upon further evaluation after the ED visit. In addition, patients for whom a drug history could not be obtained, and deaths occurring in the ED or prior to arrival are not included. Second, not all products that may be considered CCMs were included. This investigation was limited to OTC products in order to allow focused attention and interventions. Single-ingredient antihistamine products were not included as these products are indicated for a variety of purposes unrelated to upper respiratory infections, such as allergic reactions and temporary sleep disturbance. Third, intent of drug use may be misclassified for some cases. Patients may report a therapeutic purpose for using CCMs to the treating clinician when their true intent was for nonmedical use or self-harm. Nonmedical use may be overestimated by including CCM overdoses without indication of intent (e.g., unresponsive patients). Fourth, data on the most frequently implicated CCM active ingredients could help further focus prevention efforts; however, the active ingredients were not always documented (e.g., patient reported only a brand name that represents multiple different product combinations), as patients/caregivers may not know the ingredients in the specific CCM formulations that they use.44 Lack of information about implicated active ingredients can complicate patient management; thus, improved labeling and/or educational efforts to help patients/caregivers identify the active ingredients in their medications may be warranted.45 Fifth, patients may not always report concurrent use of illicit substances or alcohol. On the other hand, screening tests may erroneously identify illicit substances when large amounts of CCMs are ingested.46,47

Implementation of interventions to reduce CCM harms, and inclusion of CCMs in broader efforts to address nonmedical use, self-harm, and polypharmacy can yield important benefits for public health and patient safety. National surveillance of CCM-related harms can be used to assess progress toward medication safety goals.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

From 2017-2019, there were an estimated 26,735 US emergency department (ED) visits annually for harms from over-the-counter cough and cold medications (CCMs); 61.4% involved non-therapeutic CCM use.

Population rates of ED visits for CCM-related harms were highest among patients aged 12-34 years.

Most visits by patients aged 12-34 years involved non-therapeutic CCM use (74.1%), compared with 20.1% of visits by patients aged 55 years or older

Most visits by children aged <4 years (74.0%) were for unsupervised CCM exposures.

Concurrent medication, illicit drug, or alcohol use was frequent in ED visits for nonmedical use (61.3%) and self-harm (75.9%) involving CCMs.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Katie Rose, Ms. Sandra Goring, Ms. Arati Baral, and Mr. Alex Tocitu, from Chenega Enterprise Systems & Solutions, LLC (contractor to CDC), for assistance with data coding and programming and Mr. Tom Schroeder, Ms. Elenore Sonski, Mr. Herman Burney, and data abstractors from the US Consumer Product Safety Commission, for assistance with NEISS-CADES data acquisition. We also thank Dr. Nadine Shehab from Lantana Consulting Group (contractor to CDC) for thoughtful review of the manuscript. No individuals named herein received compensation for their contributions.

Disclaimer:

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: These data have not been presented or published elsewhere.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

See e.g., 45 C.F.R. part 46.102(l)(2), 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. §241(d); 5 U.S.C. §552a; 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fashner J, Ericson K, Werner S. Treatment of the common cold in children and adults. Am Fam Physician 2012;86(2):153–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Consumer Healthcare Products Association. OTC Use Statistics. https://www.chpa.org/about-consumer-healthcare/research-data/otc-use-statistics. Published 2019. Accessed July 13, 2021.

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine. Cough and Cold Medicines. MedLinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/coldandcoughmedicines.html. Published 2021. Accessed June 21, 2021.

- 4.Green JL, Wang GS, Reynolds KM, et al. Safety Profile of Cough and Cold Medication Use in Pediatrics. Pediatrics 2017;139(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chyka PA, Erdman AR, Manoguerra AS, et al. Dextromethorphan poisoning: an evidence-based consensus guideline for out-of-hospital management. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2007;45(6):662–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaefer MK, Shehab N, Cohen AL, Budnitz DS. Adverse events from cough and cold medications in children. Pediatrics 2008;121(4):783–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geller AI, Dowell D, Lovegrove MC, et al. U.S. Emergency Department Visits Resulting From Nonmedical Use of Pharmaceuticals, 2016. Am J Prev Med 2019;56(5):639–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schillie SF, Shehab N, Thomas KE, Budnitz DS. Medication overdoses leading to emergency department visits among children. Am J Prev Med 2009;37(3):181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shehab N, Lovegrove MC, Geller AI, Rose KO, Weidle NJ, Budnitz DS. US Emergency Department Visits for Outpatient Adverse Drug Events, 2013-2014. JAMA 2016;316(20):2115–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Geriatrics Society 2019 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(4):674–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spangler DC, Loyd CM, Skor EE. Dextromethorphan: a case study on addressing abuse of a safe and effective drug. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2016;11(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. OTC Cough and Cold Products: Not For Infants and Children Under 2 Years of Age. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/otc-cough-and-cold-products-not-infants-and-children-under-2-years-age. Published 2008. Accessed June 21, 2021.

- 13.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Use Caution When Giving Cough and Cold Products to Kids. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/special-features/use-caution-when-giving-cough-and-cold-products-kids. Published 2018. Accessed June 25, 2021.

- 14.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administratino. Over-the-Counter Pediatric Oral Liquid Drug Products Containing Acetaminophen. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/over-counter-pediatric-oral-liquid-drug-products-containing-acetaminophen. Published 2015. Accessed June 21, 2021.

- 15.Jhung MA, Budnitz DS, Mendelsohn AB, Weidenbach KN, Nelson TD, Pollock DA. Evaluation and overview of the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance Project (NEISS-CADES). Med Care 2007;45(10 Supl 2):S96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saitz R. Things that Work, Things that Don’t Work, and Things that Matter--Including Words. J Addict Med 2015;9(6):429–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakeman SE. Language and addiction: choosing words wisely. Am J Public Health 2013;103(4):e1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. NEISS - The National Electronic Injury Surveillance System: A Tool for Researchers, https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/pdfs/blk_media_2000d015.pdf. Published 2000. Updated March 2000. Accessed June 24, 2021.

- 19.US Consumer Product Safety Commission. The NEISS Sample (Design and Implementation) 1997 to Present. https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/pdfs/blk_media_2001d011-6b6.pdf. Published 2001. Accessed June 24, 2021.

- 20.US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Bridged-race population estimates: 1990–2019. https://wonder.cdc.gov/bridged-race-population.html. Accessed June 20, 2021.

- 21.Mazer-Amirshahi M, Reid N, van den Anker J, Litovitz T. Effect of cough and cold medication restriction and label changes on pediatric ingestions reported to United States poison centers. J Pediatr 2013;163(5):1372–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hampton LM, Nguyen DB, Edwards JR, Budnitz DS. Cough and cold medication adverse events after market withdrawal and labeling revision. Pediatrics 2013;132(6):1047–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Budnitz DS, Salis S. Preventing medication overdoses in young children: an opportunity for harm elimination. Pediatrics 2011;127(6):e1597–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Geller RJ. Prevention of Unintentional Medication Overdose Among Children: Time for the Promise of the Poison Prevention Packaging Act to Come to Fruition. JAMA 2020;324(6):550–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Restricted Delivery Systems: Flow Restrictors for Oral Liquid Drug Products [Draft] Guidance for Industry, https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/restricted-delivery-systems-flow-restrictors-oral-liquid-drug-products-guidance-industry. Published 2020. Accessed June 22, 2021.

- 26.Geller RJ, Hon SL, Reynolds KM, et al. #6: Do New Child Resistant Closures Reduce Injury Following Accidental Ingestion? Abstracts of the 2015 Annual Meeting of the North American Congress of Clinical Toxicology (NACCT) Web site. https://www.clintox.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/NACCT-abstracts-2015.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed June 22, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lovegrove MC, Hon S, Geller RJ, et al. Efficacy of flow restrictors in limiting access of liquid medications by young children. J Pediatr 2013;163(4):1134–9 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brass EP, Reynolds KM, Burnham RI, Green JL. Frequency of Poison Center Exposures for Pediatric Accidental Unsupervised Ingestions of Acetaminophen after the Introduction of Flow Restrictors. J Pediatr 2018;198:254–9 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paul IM, Reynolds KM, Delva-Clark H, Burnham RI, Green JL. Flow Restrictors and Reduction of Accidental Ingestions of Over-the-Counter Medications. Am J Prev Med 2019;56(6):e205–e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lokker N, Sanders L, Perrin EM, et al. Parental misinterpretations of over-the-counter pediatric cough and cold medication labels. Pediatrics 2009;123(6):1464–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.UpAndAway.org. Put your medicines up and away and out of sight. http://upandaway.org/. Accessed July 23, 2021.

- 32.Benotsch EG, Koester S, Martin AM, Cejka A, Luckman D, Jeffers AJ. Intentional misuse of over-the-counter medications, mental health, and polysubstance use in young adults. J Community Health 2014;39(4):688–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. US Department of Health and Human Services. https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-generals-report.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed June 21, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agnich LE, Stogner JM, Miller BL, Marcum CD. Purple drank prevalence and characteristics of misusers of codeine cough syrup mixtures. Addict Behav 2013;38(9):2445–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Drug Abuse. Monitoring the Future Study: Trends in Prevalence of Various Drugs. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/trends-statistics/monitoring-future/monitoring-future-study-trends-in-prevalence-various-drugs. Published 2020. Accessed June 20, 2021.

- 36.Consumer Healthcare Products Association. National Survey Shows Slight Increase in Teen Abuse of OTC Cough Medicine. https://www.chpa.org/news/2020/12/national-survey-shows-slight-increase-teen-abuse-otc-cough-medicine. Published 2020. Accessed June 18, 2021.

- 37.Consumer Healthcare Products Association. Michigan Becomes 20th State to Adopt Age-18 Sales Law on Cough Medicine. https://www.chpa.org/news/2019/11/michigan-becomes-20th-state-adopt-age-18-sales-law-cough-medicine. Published 2019. Accessed June 28, 2021.

- 38.Consumer Healthcare Products Association. StopMedicineAbuse.Org https://stopmedicineabuse.org/. Published 2021. Accessed June 21, 2021.

- 39.Spoth R, Trudeau L, Shin C, et al. Longitudinal effects of universal preventive intervention on prescription drug misuse: three randomized controlled trials with late adolescents and young adults. Am J Public Health 2013;103(4):665–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute on Drug Abuse. Principles of Substance Abuse Prevention for Early Childhood. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/principles-substance-abuse-prevention-early-childhood/table-contents. Published 2016. Accessed June 22, 2021.

- 41.Incorporated Scholastic. Over-The-Counter Medicine Safety: ELA, Science and Health Lessons About Responsible Medicine Use. https://www.scholastic.com/otc-med-safety/index.html. Published 2019. Accessed June 20, 2021.

- 42.US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing Suicide: A Technical Package of Policies, Programs, and Practices. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicideTechnicalPackage.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed June 19, 2021.

- 43.Qato DM, Wilder J, Schumm LP, Gillet V, Alexander GC. Changes in Prescription and Over-the-Counter Medication and Dietary Supplement Use Among Older Adults in the United States, 2005 vs 2011. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(4):473–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stumpf JL, Liao AC, Nguyen S, Skyles AJ, Alaniz C. Knowledge of appropriate acetaminophen use: A survey of college-age women. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2018;58(1):51–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Best Practices in Developing Proprietary Names for Human Nonprescription Drug Products [Draft] Guidance for Industry. https://www.fda.gov/media/144257/download. Published 2020. Accessed September 19, 2021.

- 46.Finn N, Wolf J, Louie J, Su B. High concentrations of dextromethorphan result in false-positive in opiate immunoassay test. Clin Chim Acta 2015;448:247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brahm NC, Yeager LL, Fox MD, Farmer KC, Palmer TA. Commonly prescribed medications and potential false-positive urine drug screens. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2010;67(16):1344–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.