Abstract

Human sepsis is a complex disease that manifests with a diverse range of phenotypes and inherent variability among individuals making it hard to develop a comprehensive animal model. Despite this difficulty, numerous models have been developed that capture many key aspects of human sepsis. The robustness of these models is vital for conducting pre-clinical studies to test and develop potential therapeutics. In this article, we describe four different models of murine sepsis that can be used to address different scientific questions relevant to the pathology and immune response during and after a septic event. The first protocol details a non-synchronous cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) model of sepsis, where mice are subjected to polymicrobial exposure through surgery at different time points within two weeks. This variation in sepsis onset establishes each mouse at a different state of inflammation and cytokine levels that mimics the variability observed in humans when they present in the clinic. This model is ideal for studying the long-term impact of sepsis on the host. The second protocol is also a type of polymicrobial sepsis, where injection of a specific amount of cecal slurry from a donor mouse into the peritoneum of recipient mice establishes immediate inflammation and sepsis without any need for surgery. The third protocol describes infecting mice with a defined Gram+ or Gram− bacterial strain to model a subset of sepsis observed in humans infected with a single pathogen. The last protocol describes administering LPS to induce sterile endotoxemia. This form of sepsis is observed in humans exposed to bacterial toxins from the environment.

Keywords: Sepsis, mouse models, CLP, Cecal Slurry sepsis, microbial sepsis

INTRODUCTION

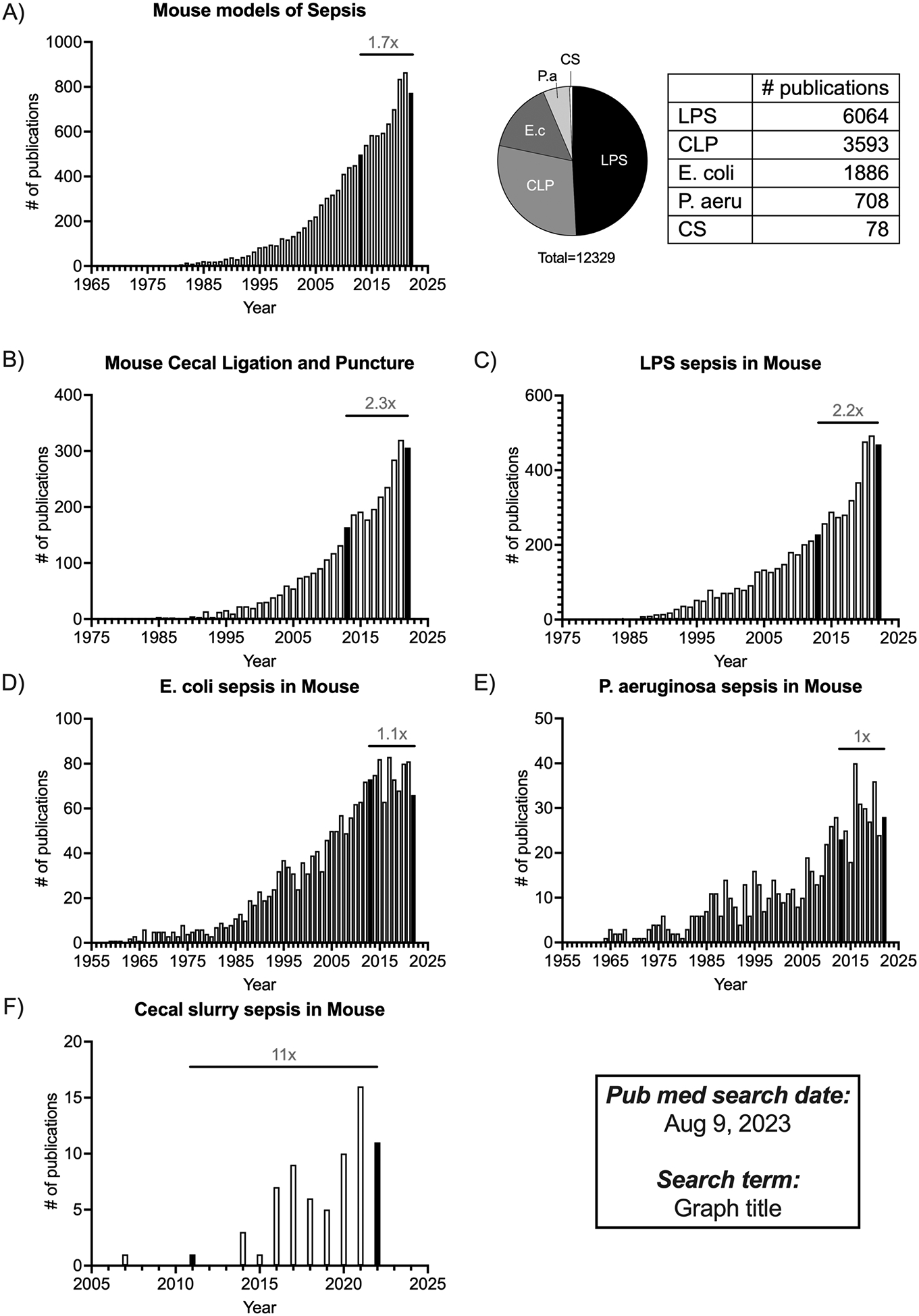

Sepsis in humans is defined by an overwhelming response to an infection or toxin that causes hyper-inflammation and immune cell death, which can eventually lead to multi-organ failure and death (Sanger et. al., 2016). While some patients develop sepsis before being admitted to the hospital, others develop sepsis days after hospitalization for other medical reasons. Consequently, treatments need to be tailored to each sepsis patient depending on the severity of the symptoms. All these features make it important to develop robust mouse models that capture the multitude of phenotypic and developmental aspects of human sepsis to empower scientists to translate their research from bench to bedside. The oldest published record of mouse septicemia in PubMed dates to 1892 (Moore, 1892). Monomicrobial sepsis models, using bacteria such as E. coli or P. aeruginosa, in mice garnered early interest (Fig.1D–E). In the attempt to find therapies from bacterial and fungal components, scientists isolated endotoxins like LPS. Once we learned the significance of these endotoxins in establishing inflammation, the LPS endotoxemia model came into existence (Parant et. al., 1977). The ease of execution and reproducibility of the LPS model have made it the most published model of sepsis (Fig.1A, 1C). Through the scientific unraveling of complex sepsis phenotypes in humans, the mouse models have also evolved to complement that. Cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) is one such model that was first established in mice in 1983 (Baker et al., 1983). The CLP model captures some of the most important hallmarks of human sepsis – specifically, the inflammation, lymphopenia, and long-term immunosuppression – making it the most comprehensive model currently used today. The cecal slurry model of sepsis is relatively new compared to the other models and has been slowly gaining traction since 2011 (Fig.1F; Wynn et al., 2011). Publication data from PubMed (as of Aug, 2023) show the number of publications using the LPS or CLP models has increased 2-fold in the last decade (Fig. 1B–C), while papers using a monomicrobial sepsis model appear to be reaching saturation (Fig. 1D–E). It is important to emphasize that all these sepsis models are still relevant for preclinical use depending on the scientific question(s) being investigated.

Figure 1.

Summary of studies published using mouse models of sepsis over time. PubMed was conducted on Aug 9 2023, to search for different mouse models of sepsis, where the “search terms” used are mentioned as the graph title. The indexing Information was downloaded from the “Results by year” filter to generate the graphs. A. Summary of publications focusing on “Mouse models of sepsis” are listed by year in the bar graphs, with the pie chart showing the number of publications of each model that make up the total publication count. B, C, D, E, F. Summary of publications listed by year, focusing on “Mouse cecal ligation and puncture”, “LPS sepsis in mouse”, “E. coli sepsis in mouse”, “P. aeruginosa sepsis in mouse”, and “Cecal slurry sepsis in mouse” respectively. All the bar graphs show the fold change in the number of publications between 2013–2023. Bars indicating the datapoints for 2013 and 2023 are filled in Black for ease of identification.

In 2020, we published a protocol detailing the CLP model of sepsis in Current Protocols in Immunology (Sjaastad et al., 2020). In this update, we will be describing the intricacies and strengths/weaknesses of other mouse models of sepsis routinely used to address different scientific questions. The first protocol outlines a non-synchronous model of polymicrobial sepsis, where CLP surgery is performed on different days but all the analyses of that cohort of mice is performed on the same day. This variation of the CLP model will capture the variability observed in humans in terms of their state of inflammation, lymphopenia, and disease kinetics at the time of clinical presentation, and thus serves as a better pre-clinical model to assess the efficacy of immunotherapies to treat sepsis. The second protocol tells the methodology for the cecal slurry model, where a defined amount of cecal slurry is directly injected into the peritoneum of recipient mice to induce sepsis. This model can also be used to study cytokine kinetics and lymphopenia (especially at early time points) without the complications of surgery. The third protocol tells of the steps in a monomicrobial model of sepsis, where mice are infected with a predetermined dose of Gram+ or Gram− bacteria to induce sepsis. This model is useful to measure pathogen-specific sepsis phenotypes along with immune responses. The final protocol gives a description of an LPS endotoxemia model, where a septic response is induced in mice without any infection. This model is useful for assessing short-term inflammatory cytokine responses and testing therapies that target the cytokines (or other circulating molecules) without the added complications of a cellular response to infection.

NOTE: Protocols involving live animals must be reviewed and approved by the investigator’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Appropriate personal protective equipment (e.g., gloves, surgical mask, hair net, lab coat, protective sleeves) should be worn based on institutional guidance and regulations. In addition, the use of any controlled substances (e.g., ketamine) requires appropriate licensure and storage. Bacterial pathogens, such as E. coli and P. aeruginosa, are Bio Safety Level-2 [BSL-2] pathogens. Therefore, follow all appropriate guidelines and regulations for the use and handling of pathogenic microorganisms. All bacterial usage requires the preparation of sterile media, plates, and glassware.

[*Copy Editor: This is an update of a previously published paper in CPI. The authors elected to reference the previous article (Sjaasted et al) rather than repeating the entire original protocol for the induction of CLP. The editors approved this.]

Basic Protocol 1: Non-synchronous Cecal Ligation and Puncture

The following protocol describes the method for inducing polymicrobial murine sepsis by non-synchronous cecal ligation and puncture (non-sync CLP). CLP is the most used model of polymicrobial sepsis that has received outstanding attention over the past decade with more than 3500 publications in PubMed (Fig.1). Here, we propose a non-synchronous variation to the CLP model, where instead of performing all CLP surgeries at one sitting, mice are staggered into different groups where they undergo surgeries at different days/hours (Fig. 2D). While all the technical aspects for each CLP surgery remain identical to the previously-published protocol (Sjaastad et al., 2020), inclusion of mice on different time courses after the septic insult attempts to imitate the real-world situation where sepsis patients are admitted during various stages of sepsis, with little-to-no information about the exact onset, and allows to account for such heterogeneity that is often neglected during conventional CLP.

Figure 2.

Using non-synchronous CLP in mouse to achieve the heterogeneity of immune system states of human sepsis patients. A. Serum collected from septic patients shortly after admission into the hospital(n=14), and serum from human healthy control (HC, n=12) are used to assay for IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-10 cytokine levels. B. Mice are subjected to sham surgery(n=20) at −7D, or CLP surgery at −7D, −3D, −1D, or −6hrs. Serum was collected from all the mice(n=67) at 3,6,12,24,48, and 72 hours post CLP. The serum from all the time points is pooled to show the levels of IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-10. C. Kinetics of the serum cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-10) at different times post CLP. D. A model describing the non-synchronous CLP sepsis in mice. Unpaired t-test was performed between groups in 2A, 2B, where * p< 0.05, ** p<0.01, and error bar represents SEM. LOD- Limit of detection.

Materials:

Please refer to Sjaastad et al. for materials (Sjaastad et al., 2020).

Induction of non-synchronous CLP in mouse:

Please refer to Sjaastad et.al for the annotated protocol steps to induce polymicrobial sepsis via CLP surgery (Sjaastad et al., 2020). Specifically, the details about how to prepare for surgery, anesthetize and prepare first mouse, perform CLP, perform post-operative care, and perform additional CLPs can be found. To adjust the previous CLP protocol to a non-sync CLP method, one need to perform CLP surgeries at different days/times and recommend scattering mice so that after all the surgeries are performed, there are mice that received CLP 7 days, 3 days, 1 day, and 6 hours before using the CLP mice for the experiment. Mice in the control group underwent sham surgery 7 days before the mice were ready for the experiment. Refer to the previous article (Sjaastad et al., 2020) for the post operative care and monitoring procedures. For the non-synchronous CLP protocol, make sure that the mice undergoing CLP 7 days, 3 days, 1 day and 6 hrs should be given the corresponding post operative care and monitoring separately.

Basic Protocol 2: Cecal slurry model of murine sepsis

The following protocol describes the method for preparing a cecal slurry (CS) for inducing polymicrobial sepsis after intraperitoneal injection into recipient mice. The following protocol is designed for use in adult mice, but the protocol can be modified for use in neonatal mice. Any strain, sex, or age of mouse can (in theory) be used in the following protocol, but donor and recipient mice should be matched.

Materials:

Donor mice: Age- and strain-matched mice to recipient mice, for example 12-week-old female C57BL/6 mice obtained from The Jackson Laboratory

Primaxin I.V. (imipenem 500mg stabilized in Cilastatin, NDC 006-3516-59, Merck)

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (see Reagents and Solutions)

15% Glycerol in PBS (Sigma G2026, autoclave sterilize)

Saline Solution (NDC 57319-555-06)

50 mL Beaker

Cell Screen 860 μm mesh (Bellco Glass Inc., Vineland NJ: 1985–00020)

Cell Screen 190 μm metal mesh strainer (Bellco Glass Inc., Vineland NJ:1985–00060)

Cell Screen 94 μm metal mesh strainer (Bellco Glass Inc., Vineland NJ 1985–00150)

Magnetic stir bar

60 mm × 10 mm sterile culture dish plate (Corning)

50 mL conical tubes (Corning Falcon)

23-gauge needle

Slurry Stock Preparation

-

1

Euthanize the donor mouse and open the peritoneum to access the cecum.

-

2

Cut the cecum where it meets the intestine. It visibly will have a three-way intersection. Transfer cecum in an empty 60 mm × 10 mm culture dish over ice.

-

3

Remove the cecal contents by squeezing from the closed end to the opening into a previously weighed 50 mL conical tube. Weight the total mass of cecal contents.

-

4

Resuspend the cecal content in 15% glycerol in PBS solution, using 1 mL of the 15% glycerol in PBS solution for every 100 mg (wet weight) cecal content.

-

5

Pass the cecal contents through a sterile 860 μm mesh strainers over another 50 mL conical tube. Using the back end of a plunger, scrape back and forth across the mesh until only the large contents remain.

-

6

Repeat the process with 190 μm and 94 μm mesh strainers, respectively, into fresh 50 mL conical tubes.

-

7

Transfer the slurry contents into a 50 mL glass beaker, along with a magnetic stir bar.

-

8

Under continuous stirring, dispense the slurry in 1 ml aliquots into cryovials and store at −80°C.

Preparation of antibiotics

-

9

Weigh desired amount of Primaxin powder and reconstitute in sterile saline at 5 mg/mL. Aliquot and store frozen at −20°C for up to 1 week. (Steele, AM. et al. Shock. 2017)

Antibiotics should be prepared the day before beginning an experiment.

Inducing Polymicrobial Sepsis

-

10

Weigh mice and calculate the volume of slurry contents to be injected (1.3 mg cecal slurry per gram body weight).

This CS dose was calculated to result in 100% mortality within 48 hours without any resuscitation method, but >70% survival when antibiotics/resuscitation are administered. A pretreatment body temperature can also be taken using a rectal temperature probe.

-

11

Take frozen CS stock and thaw immediately before injection.

-

12

Mix thoroughly with a 23-gauge needle and inject intraperitoneally (i.p.).

Cecal contents can sink to the bottom and/or clog the needle.

-

13

Begin resuscitation interventions 10 hours after cecal slurry injection by administering 300 μL of 5 mg/mL Primaxin in saline (1.5 mg/mouse) i.p. and 1 mL of pre-warmed sterile saline subcutaneously.

-

14

Administer resuscitation interventions every 12 hours until mice body temperature recovered to at least 35°C.

-

15

Within 24–48 hours of CS administration, perform peripheral bleeds (50–100 μL) for serum collection (to assess the magnitude of the cytokine storm) and/or lymphopenia evaluation.

-

16

21 days post-CS injection, mice are ready for post-sepsis studies. Mice that did not develop severe hypothermia (<30°C at 10 hours) should be excluded from the study.

Mice should still be monitored on a regular basis (daily for first 5–7 days after CS injection, and then every 2–3 days until use in post-sepsis studies. Body temperatures and weights can be measured as long as desired, but they should return to pre-CS values within 7 days.

We routinely evaluate mice for clinical signs of sepsis for scoring disease severity in both the CLP and CS models. Clinical scores can be assessed using an ascending morbidity scale as previously described (Berton et. al., 2022; Silva et. al., 2023). Grooming: 0, (Normal); 1, fur that has lost shine/become matte (Dusty); 2, fur becomes erect or bristling (Ruffled). Mobility: 0, mobile without stimulation (Normal); 1, mice are less responsive/mobile to stimuli (Reduced); 2, mice are unresponsive to stimuli (Immobile). Body Position: 0, body is fully extended (Normal); 1, back is arched/curved (Hunched); 2, laying on side at rest (On side). Weight loss: 0, Due to minimal weight loss that occurs in sham control mice, weight loss has been adjusted to allow for surgery-specific weight loss to be mitigated (<10%); 1, moderate weight loss (10–15%); 2, severe weight loss (>15%). After giving one score for each category, the sum of all categories indicates disease score. Importantly, dead mice are given highest score (8) on the day of death, and thereafter removed from scoring. Healthy scores range from 0–2; moderate disease scores range from 3–5; and severe disease scores range from 6–8.

Using the doses of cecal slurry described here, mice will show signs of sepsis (e.g., increased serum cytokines, increased pathogen burden in the blood, decrease in immune cells in the blood and lymphoid organs, decrease in body temperature) within 48 hours of infection. However, the dose can be increased/decreased to modulate disease severity (survival, serum levels, weight loss, lymphopenia, and body temperature).

Basic Protocol 3: Monomicrobial model of murine sepsis

Experimental monomicrobial sepsis can be induced in mice by direct injection of a single viable pathogen. This model mimics what would be a systemic infection derived from a primary infection (e.g., severe urinary tract infection/pyelonephritis or bacterial pneumonia). Bacterial infections are the primary causes of pathogenic sepsis, but systemic fungal and viral infections can also induce sepsis (especially in immunocompromised individuals). Because of the breadth of microbes that can induce sepsis and the extensive number of monomicrobial models that could be used, we will describe a model where mice experience a systemic uropathogenic E. coli infection by intravenous inoculation.

Materials:

C57Bl/6 mice obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (but other strains or genetically modified mice can be used depending on the experimental question being asked).

Kanamycin-resistant uropathogenic E. coli strain UTI89-kan-RFP (Mora-Bau et al., 2015)

Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Spectronic 20D+ Cat#333183000)

Miller’s LB Agar (RPI (Research Products International) Cat# L24020–500.0) (see Reagents and Solutions)

Miller’s LB Broth (RPI (Research Products International) Cat# L24040–500.0) (see Reagents and Solutions)

Sterile 100 × 15mm petri dish (VWR, Cat# 25384–092)

96-well plate (ThermoFisher Cat# 442404)

1 L Glass Bottle

Insulin Syringes with Needle (29G × ½”)

Preparation of Bacteria prior to infection

-

1

Pick a single colony of uropathogenic E. coli strain UTI89-kan-RFP bacteria grown on LB agar plates containing kanamycin (50 μg/mL) using a sterile pipette tip or inoculating loop and add it to 10 mL of LB broth containing kanamycin (50 μg/mL; Mora-Bau et al., 2015). Grow bacteria statically (i.e., no shaking) overnight at room temperature.

-

2

The following morning, measure the optical density of the culture using a spectrophotometer set to a wavelength of 600 nm (OD600).

For the uropathogenic E. coli strain UTI89-kan-RFP, the colony forming units (CFU)/mL were calculated according to the empirically determined formula OD600 0.35 = 2×108 CFU/mL.

For example, if the culture has an optical density of 2.28, then it contains 1.30 ×109 CFU/mL

OD600 0.35 = 2×108 CFU/mL

OD600 2.28 = X x108 CFU/mL => OD600 2.28 = 1.30×109 CFU/mL

Note: Each bacteria strain will have different OD600 reading to CFU readout. This information may be known, or may need to be empirically determined.

-

3

Determine the number of bacteria to prepare based on the infectious dose needed to induce the desired magnitude of sepsis and the number of mice to infect.

For example, each mouse will receive 1×108 CFU or the uropathogenic E. coli strain UTI89-kan-RFP in a volume of 50 μL. Thus, the bacteria should be adjusted to a concentration of 2×109 CFU/mL.

For example, 15 mice are to be injected. Thus, 15 mice × 50 μL = 750 μL. It is important to always prepare an excess amount to account for volume loss in syringes/needles.

Using these examples of bacterial concentration and final volume needed, determine the number of bacteria needed.

For example, 1000 μL bacteria are needed at a concentration of 2×109 CFU/mL

2×109 total CFU are needed, but the concentration of the overnight culture is 1.30×109 CFU/mL

(2×109 CFU)(X μL) = (1.30×109 CFU)(1000μL)

X = 1538μL

-

4

Transfer the necessary volume of bacterial culture to a microcentrifuge tube (or multiple tubes if required). Centrifuge the tube(s) at 13,000 rpm for 1 min to pellet the bacteria. Aspirate the culture medium from the tube, being careful not to disturb the bacterial pellet. Resuspend the bacteria in the predetermined volume (1000μL in the above example) in sterile PBS. The bacteria are now ready for injection.

Reserve a portion of this bacterial prep for dilution plating to determine the actual titer being injected.

Administration of bacteria to mice

-

5

Anesthetize mice using approved methodology (e.g., isoflurane or Ketamine/xylazine).

-

6

Briefly vortex bacteria prior to drawing up into a 29Gx1/2” insulin syringe with needle.

An insulin syringe is listed here because it has a small “dead volume” and a higher gauge needle that can make the retro-orbital injection easier to perform.

-

7

Deliver 50 μL of the bacterial suspension intravenously (via the retro-orbital plexus) per mouse for an infectious dose of 2×108 CFU/mouse.

-

8

Within 24–48 hours of bacterial injection, perform peripheral bleeds (50–100μL) for serum collection (to assess magnitude of cytokine storm) and/or lymphopenia evaluation.

-

9

Mice are returned to caging and housed under BSL-2 conditions for the duration of the experiment. Mice should be monitored daily (at least) for signs of morbidity using the ascending score system previous described.

Using the doses of uropathogenic E. coli described here, mice will show signs of sepsis (e.g., increased serum cytokines, increased pathogen burden in the blood, decrease in immune cells in the blood and lymphoid organs, decrease in body temperature) within 48 hours of infection. However, the infectious dose can be increased/decreased to modulate disease severity (survival, serum levels, weight loss, lymphopenia, and body temperature).

Basic Protocol 4: LPS model of murine sepsis

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection is used extensively to mimic the septic shock observed in humans. The model uses purified LPS (usually from E. coli) injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) or intravenously (i.v.) into mice to induce endotoxemia. LPS is a pathogen associated molecule pattern (PAMP) that signals through Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) on innate immune cells. Dose-dependent administration can generate varying severity of sepsis phenotype.

Materials:

Purified lipopolysaccharide from E.coli O111:B4 (InvivoGen tlrl-eblps Catalog#00-4976-93)

Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) (see Reagents and Solutions)

Syringe with 25g needle

C57Bl/6 Mice from Jackson Laboratories

Administration of LPS to mice

Weigh mice to be injected with LPS.

Prepare purified LPS to a working concentration of 10 (for severe inflammation), 5 (for moderate inflammation), or 1 (for mild inflammation) mg/kg body weight.

Inject 200μL of LPS solution into the mouse in a single dose intra-peritoneally (i.p.).

Within 24–48 hours of bacterial injection, perform peripheral bleeds (50–100μL) for serum collection (to assess magnitude of cytokine storm) and/or circulating immune cell evaluation.

Mice are returned to caging and housed under BSL-1 conditions for the duration of the experiment. Mice should be monitored daily (at least) for signs of morbidity using the ascending score system previous described.

Reagents and Solutions:

Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS)

2.3 g NaH2PO4 anhydrous (Sodium Phosphate Monobasic, Anhydrous M.W. 119.98 Fisher BioReagents BP329–1)

11.5 g Na2HPO4 anhydrous (Sodium Phosphate Dibasic, Anhydrous M.W. 141.957 Fisher BioReagents BP332)

90 g NaCl (Sodium Chloride M.W. 58.44 Fisher BioReagents BP358)

9.75 L dH2O

pH to 7.2–7.4

Miller’s LB Agar

Dissolve 40 g of Miller’s LB Agar in 1 L distilled water.

Adjust the pH to 7.2.

Autoclave for 15 minutes.

Cool to 50°C, add appropriate antibiotic, mix.

Pour 23 mL per sterile 100 × 15mm petri dish.

Cool and refrigerate at 4°C and store up to one month.

Miller’s LB Broth

Dissolve 25 g of Miller’s LB broth in 1 L distilled water.

Adjust the pH to 7.2.

Sterilize by autoclaving for 15 minutes.

Store at room temperature for up to one month.

COMMENTARY

Background Information:

The first international consensus definition for sepsis and septic shock was detailed in 1991 (SEPSIS-1: Bone et. al., 1992) to help clinicians and scientists consolidate the veritable clinical manifestations and variability observed among different patients. Despite this consorted effort in defining the characteristics of sepsis, there was a need to revise this definition twice: first in 2001 (SEPSIS-2: Levi et. al., 2003), and more recently in 2016 (SEPSIS-3: Shankari-Hari et. al., 2016). The need for such revisions is attributed to the constant uncovering of new sepsis pathophysiology, recent availability of quality data through electronic health records, and improvements in epidemiological statistics that help delineate true variation among populations (Shankari-Hari et. al., 2016). While the SEPSIS-3 definition (along with its earlier generations) has been immensely helpful in regard to making life saving decisions in ICUs, it has become more challenging for the existing animal models to accommodate newly defined attributes.

CLP murine model of sepsis is currently considered the ‘gold standard’ owing to its ability to capture diverse aspects of human sepsis (Table.1). Firstly, prolonged release of gut bacteria into the peritoneal cavity leads to the release of an array of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines (Tamayo et. al., 2011; Silva et. al., 2023). Secondly, tissue necrosis resulting from the cecal ligation leads to organ-specific abnormalities (Abhraham et. al., 2020) shortly after the surgery. Thirdly, CLP mice also exhibit transient lymphopenia followed by a long-lasting state of immune suppression (Heidarian et al., 2023; Berton et al., 2023; Martin et al., 2020), a phenomenon commonly observed in human sepsis survivors (Drewry et al., 2014; Donnelly et al., 2015). This robustness of the CLP model has enabled sepsis researchers to investigate both short- and long-term impacts of sepsis. Despite these strengths, all animal models of sepsis – specifically CLP – are criticized for their inability to predict the outcome of therapeutic interventions in sepsis patients (>200 failed randomized clinical trials; Marshall, 2014). While this could be inherent to the model itself, we should remember that the CLP model doesn’t replicate the variability in sepsis pathology observed among patients at the time of enrollment to the study. For example, upon admission to the hospital, a sepsis patient could be experiencing the early pro-inflammatory stage of sepsis, the peak of the anti-inflammatory response, or the resolution of the cytokine storm where they suffer from lymphopenia. Therefore, the primary goal of the non-synchronous CLP protocol described herein is to achieve the variation in sepsis states among mice within the study groups.

Table.1.

Mouse models of Sepsis, their similarity to human sepsis, and the pros/cons to keep in mind while designing the experiments

| Murine Model of sepsis | Description | Manipulable factors to modulate severity | Aspect of Human sepsis captured by the model | Pros | Cons | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional CLP sepsis | CLP performed at the same time for all the mice in the study |

|

|

|

|

Silva et al., 2023; Heidarian et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022; Zingarelli et al., 2019; Iskander et al., 2016. |

| Non-synchronous CLP sepsis | CLP performed at different times for mice in each experimental group |

|

|

|

|

Cai et al., 2023; Berton et al., 2023; Martin et al., 2020; Donnelly et al., 2015; Drewry et al., 2014. |

| Cecal Slurry | Intraperitoneal administration of cecal slurry at a fixed concentration |

|

|

|

|

Saito et al., 2021; Fujinami et al., 2021; Fallon et al., 2021; Ashina et al., 2020; Fujinoki et al., 2018. |

| Monomicrobial | Infection with a Gram+ or Gram− bacteria (or fungi) |

|

|

|

|

Martin et al., 2023; Herout et al., 2023; LeBlanc et al., 2021; Dimitrijevic et al., 2021; Merino et al., 2020; Martinez-Jehanne et al., 2012. |

| LPS | Administration of a fixed dose of LPS that acts as a PAMP, and mediate inflammatory signals in cells expressing PRRs |

|

|

|

|

Gabarin et al., 2021; Huggins et al., 2020; Warren et al, 2010; Rittisch et al., 2007; Copeland et al., 2005. |

The CS model of sepsis is not used as frequently as other models (e.g., CLP or monomicrobial infection), but there are some unique advantages to the CS model (Table.1). Sepsis lethality is disproportionally high in humans at the extremes of age (i.e., neonates and older adults). While CLP can be performed on adult mice, it is technically not feasible with neonatal mice. Consequently, the CS model is the preferred method for inducing murine neonatal sepsis. Additional similarities/differences between the CLP and CS models include the technical complexities of inducing polymicrobial sepsis. The severity of sepsis can be modulated by the amount of cecal contents extruded from the ligated cecum or injected as a slurry. The technical difficulties of the CLP surgery open the possibility for some inherent operator subtleties that may be difficult to fully replicate. In contrast, intraperitoneal injection of CS is a much easier procedure to perform and does not require anesthesia.

Compared to polymicrobial sepsis, monomicrobial sepsis is more common in humans. There are many protocols available using different bacterial species to induce sepsis (He et al; LeBlanc et al; Spencer et al., 2021), while fungal models of sepsis are also prevalent (Carreras et al., 2019, Fajardo et al., 2021). In each of the models, evaluating systemic inflammation, lymphopenia, temperature changes, and weight loss will be guides to determine a sepsis-causing pathogen dose used. Furthermore, the intravenous or intraperitoneal administration of the microbe bypasses the initial site of infection (e.g., lungs, bladder, kidney or gastrointestinal tract). This may be an oversight and weakness of the model if there are unknown mechanisms about tissue specific roles of infection in sepsis. However, there are advantages to using this model as many standard protocols are available to prepare microbes, and injections are easy to administer.

LPS endotoxemia is yet another model of sepsis that shares the same ease of induction as the monomicrobial sepsis. It is critical to note that sensitivity to LPS differs between humans and SPF mice (Rittirsch et al., 2007). Mice require 250–500-fold higher LPS doses to produce effects (e.g., cytokine response) comparable to that seen in humans (Copeland et al., 2005; Warren et al., 2010). The exact mechanism for this difference remains undefined, but TLR4 sensitivity can be increased in mice with microbial exposure (Huggins et al., 2019). These microbially-experienced mice have a higher frequency of cells expressing TLR4 in the circulation compared to mice housed in specific pathogen-free conditions, which lead to a more robust cytokine storm and increased mortality after LPS challenge. Table 1 elaborates some of the pros and cons of each protocol described here, and the aspect of human sepsis that they capture.

Critical Parameters and Troubleshooting:

Non-synchronous CLP model of murine sepsis

All the critical parameters and trouble-shooting options described in our previous article for CLP (Sjaastad et al., 2020) are very much applicable to this protocol as well. As for the critical parameters specific to non-synchronous CLP, careful attention to the quality and consistency of the surgeries (e.g., being performed by the same person) becomes even more critical because they are performed on different days for each experimental group of mice. The time of starting the surgery on each day should be the same so that the kinetics can be tracked accurately at later time points. The time needed to complete the surgery per mouse varies from person to person. Therefore, calculating the time to complete the surgery for all the mice on the last day is crucial, so that the time at the middle of the surgery can be set as the starting point to calculate the time to start the treatment. For instance, in Fig. 2.D if the surgery for mice in the blue group (−6hr) takes 3hrs (9AM-12PM), then 4:30PM (6hrs starting from 10:30AM) is set as the starting point of treatment or analysis. Also, mice that die before D0 can be excluded, which means it may be necessary to perform CLP surgeries on a higher number of mice to achieve the desired number of testable mice at D0. It is important to note that the mice that die from −6hrs and −24hrs group could be an artefact of poor aseptic technique. So, one should be careful while excluding mice after D0 and/or interpreting results, especially from mice that underwent CLP up to 24hrs before D0. Finally, note that we used SPF mice in this model, and by doing that we are excluding the contributions of genetic heterogeneity and infection history in humans that can influence sepsis outcome. However, studies have shown that in-bred, out-bred and dirty mice with specific pathogen experience are less susceptible to CLP sepsis compared to SPF mice (Berton et al., 2021). Therefore, it is crucial to understand that this model only accounts for the heterogeneity in the immune system states, but not the heterogeneity inherent to the host.

CS model of murine sepsis

Mice tend to eat more during the night and will have more contents in their cecum in the morning for harvesting. One full mouse cecum can yield enough fecal content to produce ~3 mL of slurry. Collecting cecal contents from multiple donor mice can generate a large bank of CS samples that can be used in multiple experiments, providing continuity, as well as increased flexibility for planning experiments. Fresh CS can also be produced on the day of each experiment, if preferred. The microbial composition of the cecal material collected and used in the slurry can vary depending on the housing conditions of the donor mice. Thus, investigators need to consider the potential impact of microbiome differences when comparing the response of recipient mice receiving CS from different donors. Like the CLP model, the use and timing of antibiotics and fluids influences the severity of the cytokine storm and recovery of the mice. Changing the timing and dosage of antibiotic treatment will influence the readouts of sepsis.

Monomicrobial model of murine sepsis

We will broadly speak about critical parameters using any monomicrobial model of sepsis. It is important to use a clinically relevant microbe where observations of the pathogen induce hallmarks of sepsis, beyond normal infection. Examples of clinical readouts such as survival, cytokine production, and lymphopenia are considerations when developing a monomicrobial model of murine sepsis. Weight loss and rectal temperatures are not demonstrated in this model, but these are other potential readouts to evaluate the severity of the response to the systemic infection. The uropathogenic E. coli described herein has a high mortality rate (80%) by day 3 using the infectious dose listed, but it gives the investigator the ability to evaluate acute innate immune responses to a systemic infection by a Gram− bacterium. When evaluating this model of sepsis for long term readouts, titer the infectious dose to induce a less severe sepsis and be sure to administer antibiotics and saline fluids to boost recovery.

LPS endotoxemia model

LPS injection is an easily repeatable procedure where the dosage can be modulated. It is a simple and straightforward procedure that can easily induce sterile endotoxemia and inflammation. LPS purity can slightly differ depending on the source, microbe and vendor. While LPS model is a one-time injection that generates high concentrations of inflammatory cytokines, it is cleared rapidly as it is one component of a complex Gram-negative pathogen. The rapid clearance does not correlate with humans as microbes replicate causing a prolonged inflammatory response. Furthermore, LPS does not induce the long-term immunosuppression phenotype seen in the CLP model of sepsis, which are not useful for studying long-term effects of sepsis.

Understanding Results:

Non-synchronous CLP model of murine sepsis

By performing non-synchronous CLP in mice (Fig.2D), we compared the serum cytokine profile of all the mice to that of human samples (Fig.2). Analysis of serum cytokine profile of septic patients shortly after their admission to hospital showed an expected increase in the levels of both pro and anti-inflammatory cytokines. However, closer examination of the data, points to a larger spread in the cytokine levels, highlighting significant diversity with respect to the inflammatory status and sepsis progression of human patients at the time of hospitalization (Fig. 2A). This variability is only replicated in CLP mice when the serum cytokine levels of mice are pooled and measured at different time intervals within 72 hours after CLP surgery (Fig. 2B). Within the first 24 hours after induction of CLP, the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β quickly rise followed by an increase in anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. The mice that survived (closed circles) the CLP-induced heightened inflammation demonstrated gradual return to the homeostatic cytokine levels by 72 hours post-CLP (Fig. 2C). Hence, the use of non-synchronous groups of CLP mice that exhibit different inflammatory status is advantageous to better mimic the heterogeneity of immune system state of sepsis patients. One can envision that this model might provide a better platform to test efficacy of the treatments to ameliorate sepsis-induced symptoms. It can even be done in a blinded fashion, so that the person performing the surgery can be different form the investigator using those mice to ask relevant questions. Once the experiment is completed, whether successful or not, it would be possible to identify if, for instance, the timing of treatment post sepsis (i.e., early vs late after sepsis induction) matters.

CS model of murine sepsis

As described in basic protocol 2, one should decline in body temperature within 10–12 hours of sepsis induction, followed by recovery within 48 hours (Fig. 3A). Depending on the CS dose used, reduction in body temperature can be seen as early as 4 hours. After inducing CS sepsis, it is important to monitor mouse body temperature until it reaches 35°C. Peripheral blood collected 46 hours post CS sepsis can be used to verify loss of white blood cells (WBCs; Fig. 3B), which is also an important phenotype observed in human sepsis. Compared to CLP, CS sepsis leads to inflammation early after induction. The levels of different cytokines in the serum of vehicle and 1.3 mg/g CS treated mice was determined before and 10 hours after CS injection (Fig. 3C). Cytokine levels were below the limit of detection at baseline (before vehicle or CS injection), and importantly remained low even after 10 hours in the mice given the vehicle. As for the CS injected mice, the levels of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-18, IFNβ, IFNγ, TNFα and anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 were increased at the 10-hour time point. Together, these parameters suggest this CS dose is capable of inducing sepsis in mice.

Figure 3.

Cecal slurry (CS) model readout of sepsis. Female mice were injected with 1.3mg/g, 0.975mg/g, 0.65mg/g or vehicle of cecal slurry prepared from 12-week-old female donor mice. Administration of antibiotics and saline fluids were given at 10hrs. A. Rectal temperatures were recorded at baseline (0hr), 4hr, 10hr, 22hr, and 46hrs. B. White blood cell counts from ACK lysed peripheral blood were counted via hemacytometer. Comparisons were made between vehicle treated (n=6) and 1.3mg/g CS treated (n=6). C. Serum from vehicle or 1.3 mg/g CS treated mice at the baseline (0hr) and 10hr were analyzed for cytokine contents. Ordinary One-way ANOVA was used in 3B, where ** p< 0.01; and error bar represents SEM. LOD- Limit of detection.

Monomicrobial model of murine sepsis

Using the information provided in protocol 3, infection of B6 mice with 1×108 CFU uropathogenic E. coli induces the rapid production of multiple cytokines and chemokines, including IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, and IL-10/CXCL10, which can be detected in the serum 3 hours post-infection (Fig. 4A). By 24 hours post-infection, cytokine/chemokine levels decrease but are elevated compared to pre-infection values. A numerical reduction in T cells, B cells, and NK cells in blood can also be seen at the 24-hour post-infection time point by flow cytometry (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

A. Sepsis readouts using uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) monomicrobial model. A. Serum levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, and IL-10/CXCL10 were measured at 0hr (baseline), 3hr, 24hr. Data were combined from two experiments using a total of n=6 mice, where each symbol represents a mouse and bars indicate means with SEM. B. Number of CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, B cells, and NK cells in the blood of mice prior to infection (baseline), 3hrs, and 24hrs after systemic UPEC infection. Unpaired t-test was performed between groups in 2B, where ** p<0.01, *** p< 0.001; and error bar represents SEM. LOD- Limit of detection.

Time Considerations:

Preparing the surgery station for CLP, performing the surgery, and waiting for the mice to recover from anesthesia (especially when ketamine/Xylazine is used) can take some time. With practice, one can perform CLP surgeries at the rate of 10–15 mins per mouse. However, it should be kept in mind that with a bigger group of mice, it takes longer to perform the surgery. Non-synchronous CLP model thus have a smaller number of mice undergoing surgery in each day, while still having a sufficient number of mice at D0 making it reactively easy compared to conventional CLP.

As for the CS, monomicrobial, and LPS models, preparation of the materials also takes some time, but the sepsis induction by itself can be performed considerably faster compared to conventional and non-synchronous CLP sepsis since the injections can be done without putting the mice under anesthesia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM134880 (to V.P.B.), GM140881 (to T.S.G.), and a Veterans Administration Merit Review Award (BX001324; to T.S.G.). V.P.B. is a University of Iowa Distinguished Scholar. T.S.G. is the recipient of a Research Career Scientist award (IK6BX006192) from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no competing interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request from the authors.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abraham MN, Kelly AP, Brandwein AB, Fernandes TD, Leisman DE, Taylor MD, Brewer MR, Capone CA, & Deutschman CS (2020). Use of Organ Dysfunction as a Primary Outcome Variable Following Cecal Ligation and Puncture: Recommendations for Future Studies. Shock (Augusta, Ga.), 54(2), 168–182. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashina M, Fujioka K, Nishida K, Okubo S, Ikuta T, Shinohara M, & Iijima K (2020). Recombinant human thrombomodulin attenuated sepsis severity in a non-surgical preterm mouse model. Scientific reports, 10(1), 333. 10.1038/s41598-019-57265-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CC, Chaudry IH, Gaines HO, & Baue AE (1983). Evaluation of factors affecting mortality rate after sepsis in a murine cecal ligation and puncture model. Surgery, 94(2), 331–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berton RR, Jensen IJ, Harty JT, Griffith TS, & Badovinac VP (2022). Inflammation Controls Susceptibility of Immune-Experienced Mice to Sepsis. ImmunoHorizons, 6(7), 528–542. 10.4049/immunohorizons.2200050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berton RR, McGonagil PW, Jensen IJ, Ybarra TK, Bishop GA, Harty JT, Griffith TS, & Badovinac VP (2023). Sepsis leads to lasting changes in phenotype and function of naïve CD8 T cells. PLoS pathogens, 19(10), e1011720. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, Schein RM, & Sibbald WJ (1992). Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest, 101(6), 1644–1655. 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, Rodgers E, Schoenmann N, & Raju RP (2023). Advances in Rodent Experimental Models of Sepsis. International journal of molecular sciences, 24(11), 9578. 10.3390/ijms24119578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreras E, Velasco de Andrés M, Orta-Mascaró M, Simões IT, Català C, Zaragoza O, & Lozano F (2019). Discordant susceptibility of inbred C57BL/6 versus outbred CD1 mice to experimental fungal sepsis. Cellular microbiology, 21(5), e12995. 10.1111/cmi.12995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland S, Warren HS, Lowry SF, Calvano SE, Remick D, & Inflammation and the Host Response to Injury Investigators (2005). Acute inflammatory response to endotoxin in mice and humans. Clinical and diagnostic laboratory immunology, 12(1), 60–67. 10.1128/CDLI.12.1.60-67.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrijevic Z, Paunovic G, Tasic D, Mitic B, & Basic D (2021). Risk factors for urosepsis in chronic kidney disease patients with urinary tract infections. Scientific reports, 11(1), 14414. 10.1038/s41598-021-93912-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly JP, Hohmann SF, & Wang HE (2015). Unplanned Readmissions After Hospitalization for Severe Sepsis at Academic Medical Center-Affiliated Hospitals. Critical care medicine, 43(9), 1916–1927. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewry AM, Samra N, Skrupky LP, Fuller BM, Compton SM, & Hotchkiss RS (2014). Persistent lymphopenia after diagnosis of sepsis predicts mortality. Shock (Augusta, Ga.), 42(5), 383–391. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajardo P, Cuenda A, & Sanz-Ezquerro JJ (2021). A Mouse Model of Candidiasis. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.), 2321, 63–74. 10.1007/978-1-0716-1488-4_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon EA, Chung CS, Heffernan DS, Chen Y, De Paepe ME, & Ayala A (2021). Survival and Pulmonary Injury After Neonatal Sepsis: PD1/PDL1’s Contributions to Mouse and Human Immunopathology. Frontiers in immunology, 12, 634529. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.634529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujinami Y, Inoue S, Ono Y, Miyazaki Y, Fujioka K, Yamashita K, & Kotani J (2021). Sepsis Induces Physical and Mental Impairments in a Mouse Model of Post-Intensive Care Syndrome. Journal of clinical medicine, 10(8), 1593. 10.3390/jcm10081593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujioka K, Kalish F, Zhao H, Wong RJ, & Stevenson DK (2018). Heme oxygenase-1 deficiency promotes severity of sepsis in a non-surgical preterm mouse model. Pediatric research, 84(1), 139–145. 10.1038/s41390-018-0028-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabarin RS, Li M, Zimmel PA, Marshall JC, Li Y, & Zhang H (2021). Intracellular and Extracellular Lipopolysaccharide Signaling in Sepsis: Avenues for Novel Therapeutic Strategies. Journal of innate immunity, 13(6), 323–332. 10.1159/000515740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XH, Ouyang DY, & Xu LH (2021). Injection of Escherichia coli to Induce Sepsis. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.), 2321, 43–51. 10.1007/978-1-0716-1488-4_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidarian M, Griffith TS, & Badovinac VP (2023). Sepsis-induced changes in differentiation, maintenance, and function of memory CD8 T cell subsets. Frontiers in immunology, 14, 1130009. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1130009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herout R, Vappala S, Hanstock S, Moskalev I, Chew BH, Kizhakkedathu JN, & Lange D (2023). Development of a High-Throughput Urosepsis Mouse Model. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland), 12(4), 604. 10.3390/pathogens12040604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huggins MA, Sjaastad FV, Pierson M, Kucaba TA, Swanson W, Staley C, Weingarden AR, Jensen IJ, Danahy DB, Badovinac VP, Jameson SC, Vezys V, Masopust D, Khoruts A, Griffith TS, & Hamilton SE (2019). Microbial Exposure Enhances Immunity to Pathogens Recognized by TLR2 but Increases Susceptibility to Cytokine Storm through TLR4 Sensitization. Cell reports, 28(7), 1729–1743.e5. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iskander KN, Vaickus M, Duffy ER, & Remick DG (2016). Shorter Duration of Post-Operative Antibiotics for Cecal Ligation and Puncture Does Not Increase Inflammation or Mortality. PloS one, 11(9), e0163005. 10.1371/journal.pone.0163005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc BW, & Lefort CT (2021). A Mouse Model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Pneumonia. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.), 2321, 53–61. 10.1007/978-1-0716-1488-4_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, Cohen J, Opal SM, Vincent JL, Ramsay G, & International Sepsis Definitions Conference (2003). 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Intensive care medicine, 29(4), 530–538. 10.1007/s00134-003-1662-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall JC (2014). Why have clinical trials in sepsis failed?. Trends in molecular medicine, 20(4), 195–203. 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MD, Badovinac VP, & Griffith TS (2020). CD4 T Cell Responses and the Sepsis-Induced Immunoparalysis State. Frontiers in immunology, 11, 1364. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MD, Skon-Hegg C, Kim CY, Xu J, Kucaba TA, Swanson W, Pierson MJ, Williams JW, Badovinac VP, Shen SS, Ingersoll MA, & Griffith TS (2023). CD115+ monocytes protect microbially experienced mice against E. coli-induced sepsis. Cell reports, 42(11), 113345. 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Jéhanne V, Pichon C, du Merle L, Poupel O, Cayet N, Bouchier C, & Le Bouguénec C (2012). Role of the vpe carbohydrate permease in Escherichia coli urovirulence and fitness in vivo. Infection and immunity, 80(8), 2655–2666. 10.1128/IAI.00457-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merino I, Porter SB, Johnston B, Clabots C, Thuras P, Ruiz-Garbajosa P, Cantón R, & Johnson JR (2020). Molecularly defined extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli status predicts virulence in a murine sepsis model better than does virotype, individual virulence genes, or clonal subset among E. coli ST131 isolates. Virulence, 11(1), 327–336. 10.1080/21505594.2020.1747799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore VA (1892). Mouse Septicæmia Bacilli in a Pig’s Spleen. The Journal of comparative medicine and veterinary archives, 13(6), 333–341. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Bau G, Platt AM, van Rooijen N, Randolph GJ, Albert ML, & Ingersoll MA (2015). Macrophages Subvert Adaptive Immunity to Urinary Tract Infection. PLoS pathogens, 11(7), e1005044. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parant M, Parant F, & Chedid L (1977). Inheritance of lipopolysaccharide-enhanced nonspecific resistance to infection and of susceptibility to endotoxic shock in lipopolysaccharide low-responder mice. Infection and immunity, 16(2), 432–438. 10.1128/iai.16.2.432-438.1977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittirsch D, Hoesel LM, & Ward PA (2007). The disconnect between animal models of sepsis and human sepsis. Journal of leukocyte biology, 81(1), 137–143. 10.1189/jlb.0806542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Fujinami Y, Ono Y, Ohyama S, Fujioka K, Yamashita K, Inoue S, & Kotani J (2021). Infiltrated regulatory T cells and Th2 cells in the brain contribute to attenuation of sepsis-associated encephalopathy and alleviation of mental impairments in mice with polymicrobial sepsis. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 92, 25–38. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrum B, Anantha RV, Xu SX, Donnelly M, Haeryfar SM, McCormick JK, & Mele T (2014). A robust scoring system to evaluate sepsis severity in an animal model. BMC research notes, 7, 233. 10.1186/1756-0500-7-233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva EE, Moioffer SJ, Hassert M, Berton RR, Smith MG, van de Wall S, Meyerholz DK, Griffith TS, Harty JT, & Badovinac VP (2023). Defining Parameters That Modulate Susceptibility and Protection to Respiratory Murine Coronavirus MHV1 Infection. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950), ji2300434. Advance online publication. 10.4049/jimmunol.2300434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva EE, Skon-Hegg C, Badovinac VP, & Griffith TS (2023). The Calm after the Storm: Implications of Sepsis Immunoparalysis on Host Immunity. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950), 211(5), 711–719. 10.4049/jimmunol.2300171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, & Angus DC (2016). The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA, 315(8), 801–810. 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjaastad FV, Jensen IJ, Berton RR, Badovinac VP, & Griffith TS (2020). Inducing Experimental Polymicrobial Sepsis by Cecal Ligation and Puncture. Current protocols in immunology, 131(1), e110. 10.1002/cpim.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer CT, Ramos Muniz MG, Setzu NR, & Sanchez Guillen MA (2021). Francisella tularensis Infection of Mice as a Model of Sepsis. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.), 2321, 75–100. 10.1007/978-1-0716-1488-4_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr ME, Steele AM, Saito M, Hacker BJ, Evers BM, & Saito H (2014). A new cecal slurry preparation protocol with improved long-term reproducibility for animal models of sepsis. PloS one, 9(12), e115705. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele AM, Starr ME, & Saito H (2017). Late Therapeutic Intervention with Antibiotics and Fluid Resuscitation Allows for a Prolonged Disease Course with High Survival in a Severe Murine Model of Sepsis. Shock (Augusta, Ga.), 47(6), 726–734. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo E, Fernández A, Almansa R, Carrasco E, Heredia M, Lajo C, Goncalves L, Gómez-Herreras JI, de Lejarazu RO, & Bermejo-Martin JF (2011). Pro- and anti-inflammatory responses are regulated simultaneously from the first moments of septic shock. European cytokine network, 22(2), 82–87. 10.1684/ecn.2011.0281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Lu Y, Zheng J, & Liu X (2022). Of mice and men: Laboratory murine models for recapitulating the immunosuppression of human sepsis. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 956448. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.956448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren HS, Fitting C, Hoff E, Adib-Conquy M, Beasley-Topliffe L, Tesini B, Liang X, Valentine C, Hellman J, Hayden D, & Cavaillon JM (2010). Resilience to bacterial infection: difference between species could be due to proteins in serum. The Journal of infectious diseases, 201(2), 223–232. 10.1086/649557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn JL, Scumpia PO, Delano MJ, O’Malley KA, Ungaro R, Abouhamze A, & Moldawer LL (2007). Increased mortality and altered immunity in neonatal sepsis produced by generalized peritonitis. Shock (Augusta, Ga.), 28(6), 675–683. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3180556d09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingarelli B, Coopersmith CM, Drechsler S, Efron P, Marshall JC, Moldawer L, Wiersinga WJ, Xiao X, Osuchowski MF, & Thiemermann C (2019). Part I: Minimum Quality Threshold in Preclinical Sepsis Studies (MQTiPSS) for Study Design and Humane Modeling Endpoints. Shock (Augusta, Ga.), 51(1), 10–22. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.