Abstract

The yeast transcriptional activator ADR1, which is required for ADH2 and other genes’ expression, contains four transactivation domains (TADs). While previous studies have shown that these TADs act through GCN5 and ADA2, and presumably TFIIB, other factors are likely to be involved in ADR1 function. In this study, we addressed the question of whether TFIID is also required for ADR1 action. In vitro binding studies indicated that TADI of ADR1 was able to retain TAFII90 from yeast extracts and TADII could retain TBP and TAFII130/145. TADIV, however, was capable of retaining multiple TAFIIs, suggesting that TADIV was binding TFIID from yeast whole-cell extracts. The ability of TADIV truncation derivatives to interact with TFIID correlated with their transcription activation potential in vivo. In addition, the ability of LexA-ADR1-TADIV to activate transcription in vivo was compromised by a mutation in TAFII130/145. ADR1 was found to associate in vivo with TFIID in that immunoprecipitation of either TAFII90 or TBP from yeast whole-cell extracts specifically coimmunoprecipitated ADR1. Most importantly, depletion of TAFII90 from yeast cells dramatically reduced ADH2 derepression. These results indicate that ADR1 physically associates with TFIID and that its ability to activate transcription requires an intact TFIID complex.

The derepression of the glucose-repressible ADH2 gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires the transcriptional activator ADR1 (16). ADR1 binds to a 22-bp palindromic sequence—UAS1—located 215 bp upstream of the transcription start site of the ADH2 gene (47). ADR1 also regulates the transcription of genes involved in glycerol metabolism (5, 29) and peroxisome biogenesis, and sequences similar to UAS1 of the ADH2 gene are found in the promoters of these genes (7, 36). Four regions of ADR1 have been identified that are required for its efficient activation of ADH2 transcription: transcription activation domain I (TADI) (residues 76 to 172), TADII (residues 263 to 357), TADIII (residues 420 to 462), and TADIV (residues 642 to 704) (5, 9, 12, 14, 39). TADII and TADIII are functionally redundant in the context of full-length ADR1 (12), suggesting that they may affect the same step in the process of transcriptional activation of the ADH2 gene. TADIV seems most important to the protein in that deletion of it reduces ADR1 function dramatically (9). In our earlier report, we had shown that individual activation domains of ADR1 can contact TFIIB, ADA2, and the histone acetyltransferase GCN5 in vitro (9). However, the deletion of ADA2 or GCN5 had only a moderate effect on the derepression of the ADH2 gene (9), suggesting the existence of additional activation mechanisms.

There are a number of potential targets for ADR1 activation domains among the core transcription factors. TFIID, TFIIF, TFIIB, RNA polymerase II (polII), TFIIH, and TFIIE have been implicated in mammalian and drosophila systems as being direct contacts for various transcription activators (48). For example, the glutamine-rich activation domain of Sp1 contacts TFIID component dTAFII110 (23); VP16 interacts with TFIIB, TBP, and histone-like dTAFII42/hTAFII31; and yeast GAL4 binds TBP and TFIIB (22, 26, 46). The ability of activators to contact multiple targets may be a reflection of activators displaying relatively weak binding to proteins and the requirement to recruit more than one component of the core transcriptional factors to obtain maximal activation potential (31).

TFIID is a multimeric complex consisting of TATA box binding subunit TBP and TBP-associated factors (TAFIIs) (6, 30). Both TBP and TAFIIs show significant degrees of evolutionary conservation in the eucaryotic kingdom (28, 37), suggesting that TFIID quaternary structure may also be conserved. Thirteen yeast TAFIIs have been cloned to date, with sizes ranging from 17 to 150 kDa (3, 25, 37). Most of these proteins are encoded by essential genes. The precise role of TAFIIs in transcription is largely unknown. In vitro studies have shown that activators have both qualitative and quantitative effects on TFIID binding to the TATA box (35). It has also been demonstrated that the TFIID binding step is first and rate limiting in the assembly of the initiation complex at many promoters (11, 24), making it a likely target for transcriptional activators. In vitro data suggest that these proteins are required for activated transcription and that they can serve as direct targets in vivo for activation domains of DNA-binding transcriptional activators of higher eucaryotes (23, 33, 46). In vivo data, however, indicate that yeast TAFIIs are not universally required for polII transcription and are dispensable for activated transcription of a number of yeast genes (27, 43). Although encoded by essential genes, temperature-sensitive alleles of TAFII130/145 and TAFII90 affect the expression of only a small fraction of yeast genes (1, 43). Similar results were observed when different TAFIIs were eliminated from the yeast cell by using a double-shutoff method (27). More recently, it has been shown that TAFII130/145 is required for expression of G1/S cyclins, several small ribosomal subunit protein genes, and the inorganic phosphatase gene PPA1 (34, 44).

We have found that ADR1 TADIV can specifically retain TFIID from yeast whole-cell extracts and that ADR1 coimmunoprecipitates with TAFII90 and with TBP. Moreover, TADIV activation potential was specifically reduced by a temperature-sensitive allele of TAFII130/145, and transcriptional activation of the ADH2 gene did not occur in vivo if the yeast cell was depleted of TAFII90. These results suggest that transcriptional activation of the ADH2 gene by ADR1 is mediated through its contacts with the TFIID complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

The yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains 938-9b and yBY40-8′ were used for transformation with plasmids expressing ADR1 from the G3PDH promoter. Strains 1427-1 and 1415-9 were derived following tetrad analysis from a cross between both YSW87 (TAF130/145) and YSW90 (taf130/145-ts1) (43) and 612-4a. Strains containing the taf130/145-ts1 allele fail to grow at 37°C but appear to grow normally at 30°C. Strains ZMY60 and ZMY68 were a gift from Z. Moqtaderi and K. Struhl, and the genotypes are described elsewhere (27). The TAFII90 shutoff assay was conducted exactly as previously described (27). Briefly, ZMY60 and ZMY68 were grown in synthetic medium lacking uracil (SC-Ura) and supplemented with 5% glucose until they reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3. At this time, CuSO4 was added to a final concentration of 500 μM and incubation was continued for another 7 h. Yeast cells were washed twice in SC-Ura supplemented with 3% ethanol and 500 μM CuSO4 and incubated in this medium for 5 h. Aliquots were taken at 0, 1, 2, and 5 h. For the preparation of yeast whole-cell extracts, yeast strains containing the ADR1-overexpressing plasmid were grown to an OD600 of 0.7 in synthetic medium lacking leucine (SC-Leu) and supplemented with 3% ethanol, 3% glycerol, or 5% glucose. All of the other strains used in this work were grown in YEP (15) supplemented with 3% ethanol and 3% glycerol to an OD600 of 0.7.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Relevant genotype |

|---|---|

| EGY188 | MATa ura3-52 his3 leu2 trp1 LexAop-LEU2 |

| 938-9b | MATα ura3-52 his4 LexAop-LEU2 adh1-Δ1 adr1 |

| YEK20 | MATa ura3 his3 trp1 leu2 suc2 ade2 lys2 tafII25::TRP1/pRS413-HA13-TAFII25 |

| yBY40-8′ | MATa ura3 his3 trp1 leu2 suc2 ade2 lys2 tafII90::TRP1/pRS413-HA13-TAFII90 |

| yKG1794 | MATa ura3 leu2 his3 brf1::LEU2/pRS413-HA13-BRF1 |

| 1415-9 | MATa ura3 trp1 his3 leu2 tafII145::LEU2/pRS313-tafII145-ts-1 |

| 1427-1 | MATa ura3 trp1 his3 leu2 tafII145::LEU2/pRS313-TAFII145 |

| 500-6 | MATa adh1-11 adh3 adr1-1 ura1 his4 trp1 |

| 411-40 | Isogenic to 500-16 but with adr1-1::ADR1-TRP1 |

| 411-26 | Isogenic to 500-16 but with trp1::4-ADR1-TRP1 |

| 411-33 | Isogenic to 500-16 but with trp1::8-ADR1-TRP1 |

| YSW87 | MATa ura3 his3 leu2 tafII145::LEU2/pRS313-TAFII145 |

| YSW90 | Isogenic to YSW87 but with pRS313-tafII145-ts-1 |

| 612-4a | MATα adh1-11 ura3 his3 trp1 leu2 |

All DNA manipulations and subcloning were done with Escherichia coli DH5α. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins were expressed in and purified from E. coli BL21.

Plasmid constructions.

The vector expressing full-length ADR1 from the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) promoter was constructed by cutting pJC100 (8) with BamHI and HindIII and isolating the fragment containing the entire G3PDH prmoter and residues 1 to 649 of ADR1 and ligating it into pRS425 (10) digested with BamHI and HindIII, which created pPK46. pAK52, containing the entire ADR1 gene with approximately 1.5 kb of 3′ sequences was cut with BstEII, blunt ended with Klenow enzyme, and cut with HindIII, and the fragment containing residues 649 to 1323 of ADR1 was isolated from the agarose gel. pPK46 was cut with SalI, blunt ended with Klenow enzyme, cut with HindIII, and ligated to the ADR1 fragment containing residues 649 to 1323, creating pPK47 containing full-length ADR1 under the control of the G3PDH promoter. pPK50 containing full-length ADR1 with TADIV deleted was constructed by cutting pPK47 with NcoI and BsgI, isolating the vector backbone from the agarose gel, cutting pPK4 (9) with the same enzymes, and ligating the pPK4 fragment containing ADR1 residues 1 to 642 and 704 to 1173 into the pPK47 backbone.

GST fusions with ADR1 TADs and Vpu were described previously (9). Isolation of LexA fusions with ADR1 TADIV has also been described (9).

ADHII and β-galactosidase activity assays.

ADHII and β-galactosidase activity assays were conducted as previously described (9), except that the medium used for β-galactosidase assays lacked both uracil and tryptophan.

Binding assays.

GST fusion proteins were expressed and bound to glutathione-agarose beads as previously described (9). Yeast whole-cell extracts were prepared from cells grown to a density of 5 × 107, collected by centrifugation, and disrupted by bead beating in 2 volumes of A300 buffer (20 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 300 mM potassium acetate, 1% Triton, protease inhibitors). Washed glutathione-agarose beads were incubated with 1 mg of yeast whole-cell extract protein in 250 μl of A300 buffer for 2 h at 4°C on a rocking platform. Unbound proteins were removed by four washes with 1 ml of A300 buffer, and specifically bound proteins were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) after boiling beads directly in sample buffer. Proteins resolved by SDS-PAGE were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane and analyzed by Western blotting as previously described (20). Antibody to yTAFII90 was kindly provided by M. Green, and antibody to the RPB1 subunit of RNA polII was a gift from J. Jaehning.

IP.

Preparation of yeast extracts for immunoprecipitation (IP) was done as described in reference 45, except that dithiothreitol was omitted from the final dialysis step. IP of triple HA1-tagged TAFII90 from yeast whole-cell extracts was conducted in IP incubation and washing buffer (25 mM KPO4 [pH 7.6], 150 mM KCl, 1 mM NaPPi, 1 mM NaF, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Nonidet P-40, protease inhibitor cocktail). A 20-μl volume of packed protein A-agarose beads was incubated with 2 μl of monoclonal antibody 12CA5 for 1 h at 4°C and in 250 μl of IP incubation and washing buffer, washed once with the same buffer to remove excess antibody, and mixed with 2 mg of yeast crude extract protein in 500 μl of IP incubation and washing buffer. Incubation was allowed to proceed for 2 h at 4°C with constant rocking. The beads were washed four times with 1 ml of the same buffer to remove unbound proteins from the yeast extract, mixed with SDS loading buffer, boiled for 5 min, and separated on an 8% polyacrylamide gel prior to Western analysis (20). TBP IPs were conducted in a similar manner, except that strains were used that were isogenic to 500-16 containing different defined ADR1 dosages and yeast whole-cell extracts were used (12).

Northern analysis.

Total yeast RNA was isolated by the hot acidic phenol method (2, 13) and quantified by spectrophotometry (A260). Approximately 40 μg of total RNA per sample was denatured with glyoxal and dimethyl sulfoxide and mixed with gel loading buffer as described in reference 32. Denatured RNA samples were loaded in duplicate and resolved on a 1.2% agarose gel, half of which was stained with ethidium bromide in 0.1 M ammonium acetate to verify the equality of loading, and the other half was transferred to a GeneScreen nylon membrane and hybridized to the 3′-32P-labeled ADH2 oligonucleotide probe GTTGGTAGCCTTAACGACTGCGCTAAC (18) in accordance with the membrane manufacturer’s instructions, except that all posthybridization washes were for 1 min each. To determine the levels of CCR4 and ADR1 mRNAs, CCR4 and ADR1 coding sequence fragments were first PCR amplified from plasmids pPC1 and pPK47, respectively. PCR products were subsequently purified with double phenol extraction-ethanol precipitation, 32P-labeled with the Amersham Corp. Random Priming Labeling Kit, and used as probes in a hybridization reaction with the same membrane used to measure ADH2 mRNA levels.

RESULTS

TADIV specifically contacts TFIID.

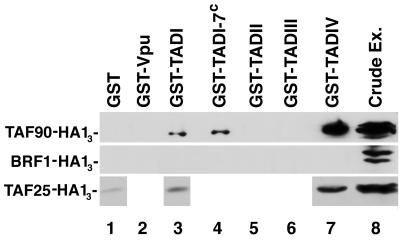

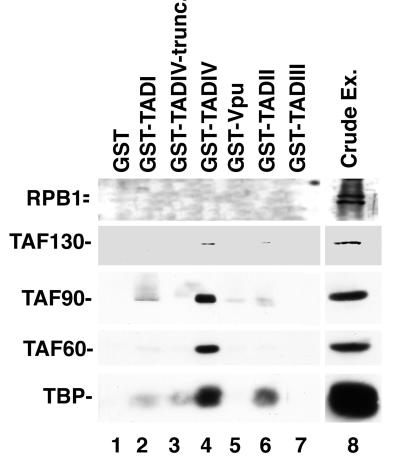

We used affinity chromatography to determine if components of TFIID interact with TADs of ADR1. GST fusions with TADI, TADII, TADIII, TADIV, and Vpu, a human immunodeficiency virus type 1-encoded control protein, bound to glutathione-coupled beads were incubated with whole-cell extracts obtained from yeast strains expressing triple HA1-tagged TAFII90, TAFII25, or BRF1, a TAF subunit of TFIIIB but not of TFIID (25, 30). As shown in Fig. 1, TADIV and, to a lesser extent, TADI were capable of specifically retaining both TAFII90-HA13 and TAFII25-HA13 but not BRF1-HA13. The GST-Vpu, GST-TADII, and GST-TADIII fusions and GST alone bound none of the tagged proteins examined. We subsequently examined if other components of TFIID were being pulled down by TADIV and TADI. Yeast extracts were incubated with the same GST fusions described above, and the proteins which were retained were probed with antibodies to different components of the TFIID complex: TAFII130/145, TAFII90, TAFII60, and TBP (Fig. 2). The GST-TADIV fusion retained all of these (Fig. 2, lane 4). The RPB1 subunit of RNA polII, however, was not retained by GST-TADIV. The most likely interpretation of this result is that TADIV retains the entire TFIID complex. TADI displayed weak binding to TAFII90 and did not retain any of the other TAF components of TFIID (Fig. 2, lane 2). Weak binding of TBP to TADI was also observed, although our previous analysis indicated that in vitro-expressed TBP does not bind TADI (9). TADI-7c, containing a mutation that enhances ADR1 transcriptional activity (17), did not display increased interaction with TAFII90 compared to TADI (Fig. 1, compare lanes 4 and 3). GST-TADII displayed weak binding to TBP, as shown previously (9), and to TAFII130/145 (Fig. 2, lane 6), while GST-TADIII did not bind any components of the TFIID complex (Fig. 2, lane 7).

FIG. 1.

GST-TADI and GST-TADIV bind to TAFII90 and TAFII25. The expression of GST fusion proteins was induced as previously described (9). After binding to glutathione-agarose beads, the GST fusion protein was incubated with crude extracts (Ex.) from yeast strains yEK20 (containing TAFII25-HA13), yBY40-8′ (containing TAFII90-HA13), and yKG1794 (containing BRF1-HA13) as described in Materials and Methods. Proteins were eluted from glutathione-agarose beads by boiling and separated by SDS-PAGE. Western analysis was conducted by using mouse monoclonal antibody 12CA5 against the HA1 epitope. One hundred micrograms of GST fusion protein was loaded in each lane. GST-TADI contains residues 148 to 262 of ADR1; GST-TADII contains residues 262 to 359; GST-TADIII contains residues 420 to 462; and GST-TADIV contains residues 642 to 704. GST-TADI-7c is the same as GST-TADI, except it contains an S230L mutation. Equivalent levels of each GST fusion were present as assayed by Coomassie blue staining.

FIG. 2.

GST-TADIV binds TFIID. GST fusions were induced as previously described (9), bound to glutathione-agarose beads, and incubated with crude extract (Ex.) from yeast strain EGY188 as described in Materials and Methods. Proteins were eluted from glutathione-agarose beads by boiling and separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were then transferred to a PVDF membrane and probed with the appropriate antibodies. The amount of GST fusion protein per lane is the same as that described in the legend to Fig. 1. The GST fusions are the same as those described in the legend to Fig. 1. GST-TADIV-trunc. represents GST-TADIV-642-679 (see Fig. 3).

The ability of TADIV to bind TFIID correlates with the ability of LexA-TADIV fusions to activate transcription.

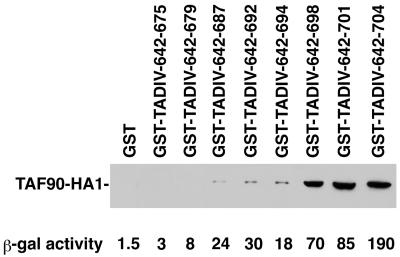

A set of GST-ADR1 truncation derivatives of TADIV that are modeled on LexA-TADIV derivatives which differ in the ability to activate transcription of a LexAop-lacZ reporter construct was tested for the ability to retain TAFII90-HA13 from yeast extracts. LexA-TADIV C-terminal deletions activated a LexAop-lacZ reporter to different extents, depending on the length of the ADR1 moiety present in the fusion. LexA-ADR1-(642-704), LexA-ADR1-(642-701), and LexA-ADR1-(642-698) retained significant transcriptional activity, whereas shorter derivatives were less active (9; see the bottom of Fig. 3). As evident from Fig. 3, the most active TADIV truncation derivatives bound TAFII90-HA13 to the greatest extent, suggesting a functional relevance of the observed binding. Similarly, TAFII130/145, TAFII90, TAFII60, and TBP were not retained by the transcriptionally inactive TADIV moiety represented in GST-TADIV-642-679 (Fig. 2, lane 3).

FIG. 3.

TADIV binding to TAFIIs correlates with TADIV activation ability. The GST-ADR1-TADIV derivatives indicated were expressed in E. coli and bound to glutathione-agarose beads as described in Materials and Methods. Extracts from yeast strain yBY40-8′ were bound to GST fusion proteins, and the resulting bound proteins were analyzed by Western analysis by using antibody 12CA5 directed against the HA1 tag, as described in the legend to Fig. 1. A 100-μg sample of each GST fusion protein was loaded on the gel. All of the GST fusion proteins were expressed at comparable levels (data not shown; 9). The β-galactosidase (β-gal) activities displayed at the bottom are for LexA-TADIV derivatives in their activation of LexAop-lacZ and are taken from reference 9. The standard errors of the means in this case were less than 20% (9).

We had shown previously that deletion of TADIV from the full-length ADR1 protein drastically reduces its ability to activate transcription of ADH2 and of a LexAop-lacZ reporter gene under the control of a single LexA operator binding site (9). Adding back a part of TADIV (residues 642 to 675) which does not bind any of the TFIID components was found not to restore the ability of LexA-ADR1 to activate transcription from the LexAop-lacZ reporter gene: the β-galactosidase activities measured in strains expressing LexA-ADR1, LexA-ADR1-642/704, and LexA-ADR1-675/704 were 900, 50, and 105 mU/mg of protein, respectively, under glucose growth conditions. All of these LexA-ADR1 proteins was expressed to equivalent extents in yeast cells as determined by Western analysis (data not shown). This result indicates that it is the region capable of binding TFIID that is required for ADR1 function.

LexA-ADR1-TADIV activation function is dependent on TAFII130/145.

The above results suggest that it is the ADR1-TADIV interaction with TFIID that would mediate part of the ability of ADR1 to activate transcription. To examine ADR1-TADIV functional dependency on TFIID, the activation ability of LexA-ADR1-TADIV was quantitated in a strain containing the temperature-sensitive tafII145-ts-1 allele that was defective in TAFII130/145 function at the restrictive temperature of 37°C (43). LexA-ADR1-TADIV displayed an over fourfold reduction in the ability to activate a LexA-lacZ reporter in a strain containing a taf130/145 allele compared to a wild-type strain (Table 2). In contrast, LexA-B42, a non-ADR1 activator, was unaffected by the taf130/145 allele. LexA-ADR1-TADIII, which did not bind TFIID in vitro, did not display a significant reduction in activation ability as caused by the taf130/145 allele. LexA-ADR1-TADII, which bound weakly to TBP, and TAF130/145 were reduced in function by 1.7-fold by a taf130/145 allele. Equivalent levels of these LexA fusion proteins were observed in the wild-type and taf130/145 strains (data not shown). These results establish a correlation between TADIV retention of TFIID in vitro as determined by Western analysis and the ability of TADIV to activate transcription in a TFIID-dependent manner.

TABLE 2.

Effect of taf130/145 allele on ADR1-TAD activationa

| Genotype | LexA fusion | Mean β-Galactosidase activity (U/mg) ± SEM | Fold decrease |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | LexA-TADIV | 171 ± 32 | 4.3 |

| taf130/145 | LexA-TADIV | 40 ± 5.7 | |

| Wild type | LexA-B42 | 160 ± 18 | 1.0 |

| taf130/145 | LexA-B42 | 160 ± 27 | |

| Wild type | LexA-TADIII | 42 ± 4.9 | 1.4 |

| taf130/145 | LexA-TADIII | 30 ± 5.4 | |

| Wild type | LexA-TADII | 110 ± 7.1 | 1.7 |

| taf130/145 | LexA-TADII | 66 ± 12 |

β-Galactosidase activities were determined as described previously (12) on at least five separate transformants following growth in glucose-containing medium at the permissive temperature of 30°C. The p1840 reporter plasmid used contains one LexA operator upstream of the lacZ gene (12). LexA-TADIV contains residues 642 to 704 of ADR1 fused to LexA-202, LexA-B42 consists of the E. coli-derived B42 activator, LexA-TADIII contains residues 420 to 462 of ADR1, and LexA-TADII consists of residues 263 to 359 of ADR1 (12).

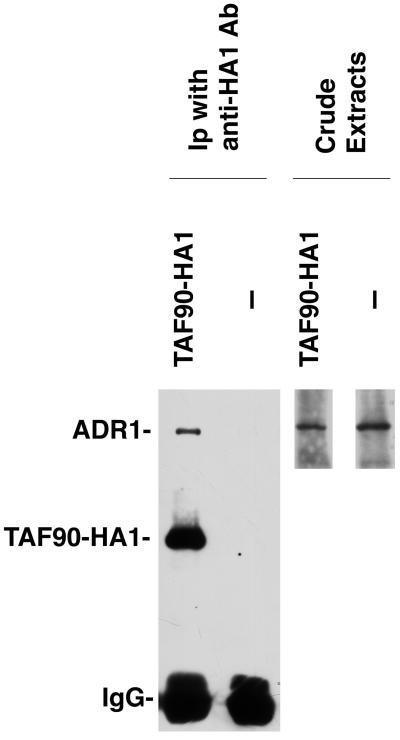

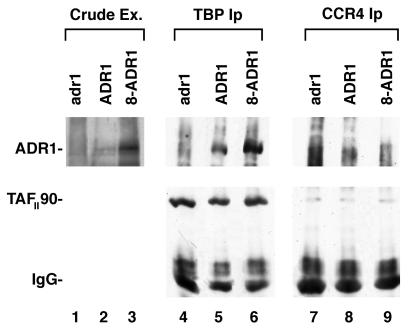

ADR1 coimmunoprecipitates with TAFII90-HA13 and with TBP.

To address the question of in vivo association of full-length ADR1 with TFIID, we initially tested if ADR1 can be coimmunoprecipitated with TAFII90-HA13 by using an ADR1 protein that was overexpressed. ADR1 was expressed from a truncated G3PDH promoter that results in a pattern of ADR1 expression similar to that observed with the native ADR1 promoter (40). TAFII90-HA13 was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA1 antibody from a strain carrying TAFII90-HA13, and ADR1 was found to coimmunoprecipitate with TAFII90-HA13 (Fig. 4). In contrast, ADR1 expressed in strain 938-9b, which lacks HA1-tagged components of TFIID, did not fortuitously immunoprecipitate with anti-HA1 antibody (Fig. 4). Because the pattern and nature of ADR1 activation of ADH2 transcription remain the same when it is overexpressed (5, 12), these results suggest that the association of overexpressed ADR1 with TAFII90 represents a physiologically relevant interaction.

FIG. 4.

ADR1 coimmunoprecipitates with TAFII90. Extracts from strain yBY40-8′, containing triple HA1-tagged TAFII90 and expressing ADR1 from a multicopy vector, and strain 938-9b, containing no HA1-tagged TAFIIs and also expressing ADR1 from the same vector, were incubated with antibody (Ab) 12CA5 directed against the HA1 tag. The resulting immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS–7.5% PAGE. ADR1 and TAFII90-HA13 were detected by Western analysis. A polyclonal antibody raised against ADR1 residues 208 to 231 was used for ADR1 detection; antibody 12CA5 was used for TAFII90-HA13 detection. A 100-μg protein sample was loaded in each crude extract lane. The level of ADR1 protein present in the cell was about 30- to 40-fold higher than that observed for ADR1 expressed at its normal dosage. IgG, immunoglobulin G.

To analyze ADR1 and TFIID interactions under conditions in which ADR1 was not highly overexpressed, we redid our analysis by using strains containing defined dosages of the ADR1 gene integrated into the genome: 16, 8, 4, and 1 copy, respectively (12, 15). Immunoprecipitating TBP with anti-TBP antibody from cells grown on ethanol-containing medium resulted in the coimmunoprecipitation of ADR1 from each of these strains containing a low dosage of ADR1 (Fig. 5, lanes 5 and 6; data not shown). The amount of ADR1 immunoprecipitated with anti-TBP antibody was proportional to the abundance of ADR1 present in the cell (Fig. 5, lanes 2 and 3; data not shown). In contrast, IPs using CCR4 antibody (Fig. 5, lanes 9 to 12) or preimmune serum (data not shown) did not immunoprecipitate ADR1. These data confirm that ADR1, when expressed at its normal physiological concentration, does associate with TFIID in vivo.

FIG. 5.

ADR1 at its physiological concentration coimmunoprecipitates with TBP. Extracts (Ex.) were prepared from yeast strains 500-16 (adr1-1), 411-40 (ADR1), and 411-33 (8-ADR1) following growth on YEP medium containing 3% ethanol. IPs were conducted with either an anti-TBP antibody (lanes 4 to 6) or an anti-CCR4 antibody (lanes 7 to 9). Lanes 1 to 3 display the ADR1 protein present in the crude extracts. Western analysis was conducted with an ADR1 antibody (upper panel) or with a TAFII90 antibody (lower panel). None of the darkenings in the ADR1 region for lanes 7 to 9 correspond to ADR1 based on other repeats of this experiment and the fact that the darkenings did not comigrate with ADR1. IgG, immunoglobulin G.

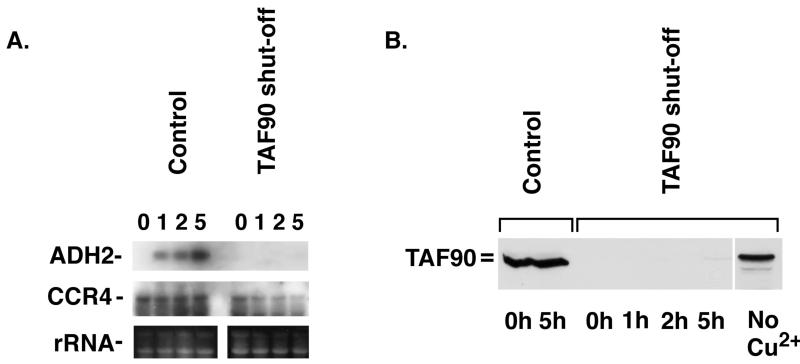

TAFII90 is required for ADH2 derepression.

TAFIIs have been implicated in coactivator function in various in vitro systems by a number of studies (23, 33, 46). Recent results (27, 34, 43, 44) indicate that yeast TAFIIs are not universally required for transcription, although they are required for transcription of some yeast genes. By using a double shutoff system designed to eliminate TAFII90 (27), it was shown, for instance, that the expression of the GAL7 gene occurred in an unimpeded manner when cells were shifted from a repressing carbon source to a nonrepressing carbon source. We therefore used the same strain and protocol for depletion of TAFII90 to test if TAFs are required for derepression of ADH2 transcription. Yeast cells were depleted of TAFII90 (Fig. 6B) and then tested for the ability to activate the ADH2 gene upon depletion of glucose. As shown in Fig. 6A, in the control strain, ADH2 mRNA appeared 1 h after glucose removal. In contrast, in the strain depleted of TAFII90, ADH2 mRNA synthesis did not occur as normalized to the level of either 25S and 18S rRNA or the CCR4 mRNA standard. The observed failure to derepress ADH2 as a result of depletion of TAFII90 was not due to a decrease in ADR1 transcription, since ADR1 mRNA levels were found to be unaffected by TAFII90 depletion (data not shown). Also, use of this TAFII90 shutoff procedure has shown previously that HIS3, DED1, GAL7, CUP1, and SSA4 expression was unaffected by depletion of TAFII90 (27). TRP3 gene expression, however, was found to be sensitive to TAFII90 depletion (27). Other studies have indicated that inactivation of any one of the TAFs can have a general effect on the inactivation of other TAFs and, hence, TFIID in general (43). Our results suggest a requirement for intact TFIID in ADR1-dependent activated transcription.

FIG. 6.

TAFII90 is required for ADH2 derepression. (A) Total RNAs from strains ZMY60 (control) and ZMY68 were prepared, separated on an agarose gel, and analyzed by Northern hybridization as described in Materials and Methods. The time points shown are after both strains were shifted to SC-Ura–2% ethanol–500 μM CuSO4 after 7 h of incubation in SC-Ura–4% glucose–500 μM CuSO4. (Bottom) An identically loaded duplicate gel was stained with ethidium bromide to identify rRNA (25S and 18S) as described in reference 45. Previous experiments have determined that rRNA or CCR4 mRNA (13, 40) serves as a useful standard for quantitation of mRNA loadings. (B) A 100-μg sample of yeast crude extract protein per lane was resolved by SDS–8% PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and probed with an anti-TAFII90 antibody (gift from M. Green). The time points shown are after strains were shifted to SC-Ura–2% ethanol–500 μM CuSO4 after 7 h of incubation in SC-Ura–4% glucose–500 μM CuSO4, with the exception of the no-Cu2+ lane, where the sample was taken prior to addition of 500 μM CuSO4.

DISCUSSION

The results reported herein demonstrate an association of ADR1 with the TFIID complex that appears to be important for ADR1 activation of ADH2. Six lines of evidence suggest that ADR1 acts through TFIID in vivo. (i) TADIV of ADR1 binds TFIID components from yeast crude extracts; (ii) the ability of derivatives of TADIV to bind TFIID components correlates with TADIV activation potential; (iii) deletion of TADIV from ADR1 severely compromises ADR1 function; (iv) the transcriptional potential of LexA-ADR1-TADIV was more severely compromised than that of other activation domains by a taf130/145 allele; (v) ADR1 coimmunoprecipitates with either TAFII90 or TBP; and (vi) TFIID appears to be required for ADR1-dependent activation of ADH2 in vivo, as depletion of yeast cells of TAFII90 prevents ADH2 derepression. These results correlate the in vitro binding of TFIID components by TADIV to the in vivo activation function by TADIV and to its dependency on TFIID. ADR1 physical association with TAFII90 and TBP in vivo further correlates with the demonstrated TFIID requirement for ADH2 derepression. These data suggest a model whereby ADR1 either aids recruitment of TFIID to the promoter, induces structural reconfiguration of TFIID, or stimulates both processes, thereby allowing transcription to occur.

The relative proportion of TBP bound to GST-TADIV of the total present in the crude extract (Fig. 2) was found to be about 1/10 of that of the TAFIIs as determined by densitometric analysis (data not shown). Since there is approximately 10 times as much TBP in the cell as there are individual TAFIIs in the cell (26a, 27, 43), it appears that TBP and TAFIIs were binding stoichiometrically to GST-TADIV. Since TBP (9) and TAFII25 (unpublished observation) do not bind GST-TADIV in the absence of other yeast proteins, these data suggest that TBP and the TAFIIs were binding GST-TADIV as a complex. The ability of TADII to retain TBP and TAFII130/145 from crude extracts further suggests that ADR1 activation domains other than TADIV may be important to ADR1-TFIID interactions. TADII may make a limited interaction with a subset of the TFIID complex. Although the physiological relevance of this interaction is unclear, a taf130/145 allele did result in a slight decrease in the ability of LexA-TADII to activate a LexA-lacZ reporter.

We had shown previously (9) that ADR1 TADs can also contact ADA2, GCN5, and TFIIB in vitro. Since ADR1 is required both for chromatin remodeling and for subsequent transcriptional activation (41, 42), it is likely that ADR1 makes multiple contacts to initiate transcription. The facts that two ADR1 molecules bind to its cognate DNA binding site (38) and that ADR1 contains at least four separate activation domains (9) further support the likelihood of distinct multiple interactions by ADR1. Because TADIV of ADR1 uses the same apparent sequence determinants for interactions with TFIID and GCN5 (695 to 704 of TADIV), it may be that the same ADR1 region binds both GCN5 and TFIID. ADR1 TADIV may first contact GCN5 to aid in nucleosome rearrangement and then contact TFIID. Other ADR1 activation domains may contribute to activation through their specific contacts with other components of the GCN5-ADA2 complex or with TFIIB (9). The GCN4 activator in yeast has also been shown to make multiple contacts by using the same apparent sequence determinants to do so. GCN4 has been shown to bind TAFIIs, the ADA2 and ADA3 proteins, and components of the RNA polII holoenzyme (21).

Notwithstanding the above considerations, it remains possible that the ADR1-TFIID interaction is dependent on other transcription factors. Since GCN5-ADA2 could make contact with TAFIIs and TBP (4, 21), it may be that ADR1 interactions with GCN5 recruit TFIID. However, we have been unable to demonstrate an in vivo association of GCN5 with ADR1 as we have done with TFIID and ADR1, suggesting that GCN5 does not mediate TFIID interaction with ADR1.

We also observed that ADR1, when overexpressed under glucose growth conditions (at least eightfold), coimmunoprecipitated with TAFII90 or TBP and did so in proportion to its abundance in the cell (unpublished observations). This level of overexpression of ADR1 allows partial derepression of the ADH2 gene on glucose, indicating that the ADR1 protein is functional (15). These results suggest that even in the presence of glucose, ADR1 can still make appropriate contacts with TFIID at the ADH2 promoter. Previous results have also indicated that ADR1 activation functions are not controlled by glucose (12). It is likely, therefore, that glucose repression affects not the ADR1-TFIID interaction specifically but other aspects of ADR1-dependent ADH2 promoter function. These other aspects include regulation of ADR1 protein (19, 40), control of ADR1-dependent chromatin remodeling that occurs only under derepressing conditions (41, 42), and binding of a repressor to ADR1 (12).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Struhl for providing strains and M. Green for antibodies and strains used in this project. The technical assistance of J. Farrell is also appreciated.

This research was supported by NIH grant GM41215, NSF grant MCB95-13412, Hatch project 291 to C.L.D., and NIH grant GM52461 to P.A.W. P.B.K. was partially supported by a Dissertation Fellowship Award from the University of New Hampshire.

Footnotes

Scientific contribution 1993 from the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apone L M, Virbasius C M, Reese J C, Green M R. Yeast TAFII90 is required for cell cycle progression through G2/M but not for general transcription activation. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2368–2380. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai Y, Perez G M, Beechem J M, Weil P A. Structure-function analysis of TAF130: identification and characterization of a high-affinity TATA-binding protein interaction domain in the N terminus of yeast TAFII130. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3081–3093. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barlev N A, Candau R, Wang L, Darpino P, Silverman N, Berger S L. Characterization of physical interactions of the putative transcriptional adaptor, ADA2, with acidic activation domains and TATA-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19337–19344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.33.19337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bemis L T, Denis C L. Identification of functional regions in the yeast transcriptional activator ADR1. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:2125–2131. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.5.2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burley S K, Roeder R G. Biochemistry and structural biology of transcription factor IID. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:769–799. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng C, Kacherovsky N, Dombek K M, Camier S, Thukral S K, Rhim E, Young E T. Identification of potential target genes for Adr1p through characterization of essential nucleotides in UAS1. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3842–3852. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherry J R. Expression and in vitro phosphorylation of the yeast transcriptional activator ADR1. Ph. D. thesis. Durham: University of New Hampshire; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiang Y-C, Komarnitsky P B, Chase D, Denis C L. ADR1 activation domains contact the histone acetyltransferase GCN5 and core transcription factor TFIIB. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:32359–32365. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.32359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christianson T W, Sikorski R S, Dante M, Shero J H, Hieter P. Multifunctional yeast high-copy-number shuttle vectors. Gene. 1992;110:119–122. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90454-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colgan J, Manley J L. TFIID can be rate limiting in vivo for TATA-containing, but not TATA-lacking, RNA polymerase II promoters. Genes Dev. 1992;6:304–315. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook W J, Chase D, Audino D C, Denis C L. Dissection of the ADR1 protein reveals multiple, functionally redundant activation domains interspersed with inhibitory regions: evidence for a repressor binding to the ADR1c region. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:629–640. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.1.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook W J, Denis C L. Identification of three genes required for the glucose-dependent transcription of the yeast transcriptional activator ADR1. Curr Genet. 1993;23:192–200. doi: 10.1007/BF00351495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook W J, Mosley S, Audino D C, Rovelli A, Mullaney D, Stewart G, Denis C L. Mutations in the zinc-finger region of the yeast regulatory protein ADR1 affect both DNA binding and transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:9374–9379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denis C L. The effects of ADR1 and CCR1 gene dosage on the regulation of the glucose-repressible alcohol dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;208:101–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00330429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denis C L, Ciriacy M, Young E T. A positive regulatory gene is required for accumulation of the functional messenger RNA for the glucose-repressible alcohol dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Mol Biol. 1981;148:355–368. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90181-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denis C L, Fontaine S C, Chase D, Kemp B E, Bemis L T. ADR1c mutations enhance the ability of ADR1 to activate transcription by a mechanism that is independent of effects on cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation of Ser-230. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1507–1514. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Mauro E, Camilloni G, Verdone L, Caserta M. DNA topoisomerase I controls the kinetics of promoter activation and DNA topology in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6702–6710. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.11.6702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dombek K M, Young E T. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase inhibits ADH2 expression in part by decreasing expression of the transcription factor gene ADR1. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1450–1458. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Draper M P, Salvadore C, Denis C L. Identification of a mouse protein whose homolog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a component of the CCR4 transcriptional regulatory complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3487–3495. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drysdale C M, Jackson B M, McVeigh R, Klebanow E R, Bai Y, Kokubo T, Swanson M, Nakatani Y, Weil P A, Hinnebusch A G. The Gcn4p activation domain interacts specifically in vitro with RNA polymerase II holoenzyme, TFIID, and the Adap-Gcn5p coactivator complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:1711–1724. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.3.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta R, Emili A, Pan G, Xiao H, Shales M, Greenblatt J, Ingles C J. Characterization of the interaction between the acidic activation domain of VP16 and the RNA polymerase II initiation factor TFIIB. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2324–2330. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.12.2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoey T, Weinzierl R O J, Gill G, Chen J-L, Dynlacht B D, Tjian R. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of Drosophila TAF110 reveal properties expected of coactivators. Cell. 1993;72:247–260. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90664-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klages N, Strubin M. Stimulation of RNA polymerase II transcription initiation by recruitment of TBP in vivo. Nature. 1995;374:822–823. doi: 10.1038/374822a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klebanow E R, Poon D, Zhou S, Weil P A. Isolation and characterization of TAF25, an essential yeast gene that encodes an RNA polymerase II-specific TATA-binding protein-associated factor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13706–13715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klemm R, Goodrich J, Zhou S, Tjian R. Molecular cloning and expression of the 32-kDa subunit of human TFIID reveals interactions with VP16 and TFIIB that mediate transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5788–5792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.13.5788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.Lee T I, Young R A. Regulation of gene expression by TBP-associated proteins. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1398–1408. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moqtaderi Z, Bai Y-L, Poon D, Weil P, Struhl K. TBP-associated factors are not generally required for transcriptional activation in yeast. Nature. 1996;383:188–191. doi: 10.1038/383188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moqtaderi Z, DePaulo Yale J, Struhl K, Buratowski S. Yeast homologues of higher eucaryotic TFIID subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14654–14658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pavlik P, Simon M, Shuster T, Ruis H. The glycerol kinase (GUT1) gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: cloning and characterization. Curr Genet. 1993;24:21–25. doi: 10.1007/BF00324660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poon D, Bai Y-L, Campbell A M, Bjorklund S, Kim Y-J, Zhou S, Kornberg R D, Weil P A. Identification and characterization of a TFIID-like multiprotein complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8224–8228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ptashne M, Gann A. Transcriptional activation by recruitment. Nature. 1997;386:569–577. doi: 10.1038/386569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sauer F, Wassarman D A, Rubin G M, Tjian R. TAFIIs mediate activation of transcription in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1996;87:1271–1284. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81822-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shen W C, Green M R. Yeast TAFII145 functions as a core promoter selectivity factor, not a general coactivator. Cell. 1997;90:615–624. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80523-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shykind B M, Kim J, Stewart L, Champoux J J, Sharp P A. Topoisomerase I enhances TFIID-TFIIA complex assembly during activation of transcription. Genes Dev. 1997;11:397–407. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.3.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simon M, Adam G, Rapatz W, Spevak W, Ruis H. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae ADR1 gene is a positive regulator of transcription of genes encoding peroxisomal proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:699–704. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.2.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tansey W P, Herr W. TAFIIs: guilt by association? Cell. 1997;88:729–732. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81916-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thukral S K, Eisen A, Young E T. Two monomers of yeast transcription factor ADR1 bind a palindromic sequence symmetrically to activate ADH2 expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1566–1577. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.3.1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thukral S K, Tavianini M A, Blumberg H, Young E T. Localization of a minimal binding domain and activation regions in yeast regulatory protein ADR1. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:2360–2369. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.6.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vallari R C, Cook W J, Audino D C, Morgan M J, Jensen D E, Laredano A P, Denis C L. Glucose repression of the yeast ADH2 gene occurs through multiple mechanisms, including control of the protein synthesis of its transcriptional activator, ADR1. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:1663–1673. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verdone L, Camilloni G, Di Mauro E, Caserta M. Chromatin remodeling during Saccharomyces cerevisiae ADH2 gene activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1978–1988. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verdone L, Cesari F, Denis C L, Di Mauro E, Caserta M. Factors affecting S. cerevisiae ADH2 chromatin remodeling and transcription. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30828–30834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker S S, Reese J C, Apone L M, Green M R. Transcription activation in cells lacking TAFIIs. Nature. 1996;383:185–188. doi: 10.1038/383185a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker S S, Shen W C, Reese J C, Apone L M, Green M R. Yeast TAFII145 required for transcription of G1/S cyclin genes and regulated by the cellular growth state. Cell. 1997;90:607–614. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80522-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woontner M, Wade P A, Bonner J, Jaehning J A. Transcriptional activation in an improved whole-cell extract from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4555–4560. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.9.4555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu Y, Reece R J, Ptashne M. Quantitation of putative activator-target affinities predicts transcriptional activating potential. EMBO J. 1996;15:3951–3963. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu J, Donoviel M S, Young E T. Adjacent upstream activation sequence elements synergistically regulate transcription of ADH2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:34–42. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zawel L, Reinberg D. Common themes in assembly and function of eukaryotic transcription complexes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:533–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]