Abstract

The specificity for self-MHC that is necessary for T cell function is a consequence of intrathymic selection during which T cell antigen receptors (TCRs) expressed by immature thymocytes are tested for their affinity for self-peptide:self-MHC. The germ-line-encoded segments of the TCR, however, are believed to have an innate specificity for structural features of MHC molecules. We directly tested this hypothesis by generating a transgenic mouse system in which the protein HLA-DM is expressed at the surface of thymic cortical epithelial cells in the absence of classical MHC molecules. The specialized intracellular function of HLA-DM has removed this MHC class II-like protein from the evolutionary forces that have been hypothesized to shape TCR-MHC interactions. Our study shows that a structural mimic of MHC class II is not sufficient to appropriately interact with the TCRs expressed by developing thymocytes. This result emphasizes the unique complementarity of TCR-MHC interactions that are maintained by the evolutionary pressures dictated by positive selection.

Keywords: T cell receptor, thymocytes, mice, T lymphocytes, thymus

Development of thymocytes is a multistep process that shapes the repertoire of mature T cells. Ideally, the mature T cell antigen receptor (TCR) repertoire is depleted of specificities that are overtly self-reactive, but is also diversified enough to mount effective immune responses (1, 2). Selection is based on the interactions of the TCRs expressed by immature CD4+CD8+, double-positive (DP) thymocytes with self-peptide:self-MHC expressed on the surface of thymic stromal cells. Poorly defined criteria determine whether this receptor-ligand interaction is of sufficient avidity to drive development of DP thymocytes to mature single-positive, MHC class I- or MHC class II-restricted T cells.

Unresolved issues regarding the positive selection of T cells include the extent that specific interactions of the TCR with MHC-bound self-peptides rather than interactions with MHC itself shape the mature CD4+ T cell repertoire. This question has been addressed by a number of systems that have not produced concordant results (3-7). Such contradictory data have led to speculation that different TCRs may have different requirements for recognition of MHC-bound self-peptide. The inherent MHC reactivity of the preselection TCR repertoire is a second issue that has not been definitively answered. In other words, it is not clear whether the germ line-encoded regions of the TCR are predisposed toward interactions with MHC, or, alternatively, whether the ability of TCRs expressed by mature T cells to interact with MHC is fully a consequence of positive selection.

Mutagenesis studies have suggested that the TCR has a conserved orientation of interaction with MHC molecules, and, therefore, conserved interactions between MHC molecules and TCRs seemed likely. Crystallographic studies of TCRs bound to MHC, however, have not fully confirmed this prediction (7). In retrospect, perhaps this finding is not surprising, considering the wide range of molecules recognized by the TCR, such as the non-MHC-encoded CD1 molecules (8), MHC class Ib molecules [such as H-2M3 (9)], and even MHC class II β chain homodimers (10).

Jerne (11) proposed that germ-line antigen receptors were predisposed for reactivity to MHC molecules as a consequence of the coevolution of this receptor-ligand pair. This hypothesis clearly explained, for example, why lymphocytes from one individual could crossreact with MHC molecules expressed by a different individual: so-called alloreactivity (11, 12). The complexities of intrathymic positive and negative selection were not, however, appreciated when Jerne formed his hypothesis. For a lymphocyte to survive, it must interact with MHC, and, therefore, inherent specificity of antigen receptors cannot be ascertained by analyzing the mature repertoire. Appreciating this complexity, Raulet and colleagues (13) generated hybridomas from T cells that were positively selected in the absence of MHC. These hybridomas proved to have a frequency of alloreactivity to non-self MHC that was equivalent to their MHC-selected counterparts. These data, together with other published work (10, 14), support the concept that the germ line-encoded regions of the TCR are inherently MHC-specific, emphasizing that complementarity to the peptide/MHC-binding site is a major evolutionary selective pressure on the TCR. What is not clear from previous work is whether or not specific features of MHC molecules are required for interactions with TCRs.

HLA-DM (DM) and the mouse homologue H-2M are pre-dominantly sequestered in endosomal-like compartments known as MIICs (15) due to a tyrosine-based motif in the tail of the β chain (16, 17). This MHC-encoded molecule has strong tertiary structural similarity to MHC class II (18, 19), but, due to its intracellular residence, it has been removed from the forces of evolution that have been hypothesized to drive and maintain TCR-MHC interactions (20). By generating a transgenic mouse system in which surface DM (sDM) is expressed on thymic cortical epithelial cells in the absence of conventional MHC molecules, we sought to understand whether specificity for MHC is inherent in TCR genes due to evolutionary pressures. Our analyses show that expression of sDM on thymic cortical epithelial cells is not sufficient for thymocytes to develop into mature T cells. These results emphasize the unique involvement of intrinsic features of the MHC structure for the positive selection of T cells.

Materials and Methods

Transfections. cDNA clones for wild-type HLA-DMA and the mutant version of HLA-DMB were cloned into the pMCFR expression vector (21). The vectors were transfected by electroporation into the B cell line CH27 (22). Stable clones were derived by selection with G418.

Mixed Lymphocyte Reactions. Lymph node cells (2 × 105) from B10.BR (I-Ak) or C57BL/6 (I-Ab) mice (responders) were incubated with either irradiated parental CH27 (I-Ak) or irradiated sDM transfected CH27 cells (stimulators) in 96-well plates. Cells were pulsed with [3H]thymidine after 72 h, and the level of [3H]thymidine incorporation was measured after 96 h.

Generation of Transgenic Mice. sDM cDNA clones used for transfections were transferred into a vector containing the promoter region for keratin 14 (K14) (23). The transgenes were coinjected into fertilized F2 eggs obtained from matings of (C57BL/6J × CBA/J)F1 mice by Sloan-Kettering's Mouse Genetics Core Facility. Three founder lines were generated, and two were backcrossed to I-Aα, β2-microglobulin double MHC-deficient mice (Taconic Farms) and then intercrossed to generate MHC-deficient mice that were homozygous for the transgenes. Mice were genotyped by PCR, which was confirmed by FACS.

Thymic Stromal Cell Culture. Thymuses were harvested from K14-sDM transgenic or control MHC-deficient mice, cut into small pieces, washed with Bruff's media containing 5% FBS, and subsequently rinsed with media containing 1% FBS to remove thymocytes. Thymic stromal cells were released from the tissue by digesting with 1 mg/ml collagenase/dispase solution containing DNase I for 30 min at 37°C. After percoll gradient centrifugation, cells from the low density layer were taken and cultured in Bruff's medium complemented with 5% FCS for 1 week. Cells in the supernatant were removed, and only adherent cells were taken for further analyses.

Flow Cytometry. Cells were analyzed by using a CyAn flow cytometer (DakoCytomation). Antibodies against CD11b, CD69, CD8, CD4, TCRβ, and CD24 were purchased from BD Biosciences. The DEC205 antibody was provided by Sloan-Kettering's Monoclonal Antibody Core Facility. Antibodies against DM (MaP.DM1) (24) and HLA-DO (Mags.DO5) were a gift from L. Denzin (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center). Each mAb was either biotinylated or directly conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488, FITC, phycoerythrin (PE), PECy7, PECy5, or allophycocyanin (APC) fluorophores. APC- or PE-conjugated streptavidin (BD Biosciences) was used to reveal staining with biotinylated mAbs. DAPI was used for dead cell exclusion, and cell doublets were eliminated by monitoring the pulse width signal.

Immunohistochemistry. Thymuses were harvested, embedded in OCT compound (Sakura, Torrance, CA), and frozen on dry ice. Frozen sections were mounted on slides and fixed in acetone. Cells were labeled with biotinylated MaP.DM1 or Mags.DO5 Abs and visualized by streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase. The enzyme reaction was developed by using the conventional substrate for alkaline phosphatase (Fast Red, Sigma-Aldrich).

Results and Discussion

DM is normally localized in endosomal/lysosomal compartments where it functions as a molecular editor for antigenic peptide loading onto MHC class II (25). We selected DM as substitute for MHC class II because the intracellular localization of DM has sequestered this protein from the evolutionary pressures that may play a role in maintaining TCR interactions with classical MHC molecules. Although the amino acid identity of DM with other MHC class II genes is only 30%, as compared with 60% identity among classical MHC class II genes (26), it has a remarkably similar tertiary structure to MHC class II (18, 19). The most dramatic effect of the amino acid sequence differences is the apparent closure of the peptide-binding groove (18, 19). Lack of peptide binding is supported by the inability to directly elute peptides from DM (L. Denzin, personal communication). This significant difference from classical MHC class II was critical because it relieved our studies from the complexities of thousands of different ligands created by the binding of self-peptides. Sequence differences also result in the loss of an obvious CD4 binding motif, which should eliminate binding to DM by this invariant, germ-line-encoded self-protein.

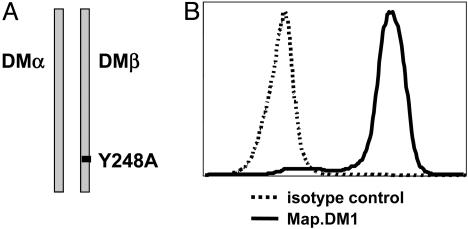

Naive T Cells Are Not Activated by Surface DM. We first tested DM-TCR interactions by determining whether naive T cells could be stimulated by DM. We transfected the mouse B cell line CH27 with the wild-type DMA gene and a mutated version of the DMB gene. Mutation of tyrosine 248 to alanine in the cytoplasmic tail of the DMβ chain (Fig. 1A) redirects targeting of DM from endosomes to the cell surface (16). Cell surface expression of sDM (Fig. 1B) was confirmed with the DM-specific mAb MaP.DM1 (24). Cell surface levels of the endogenous I-Ak and I-Ek MHC molecules on the transfected and nontransfected clones were similar, as determined by FACS (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Targeting of DM to the cell surface. (A) Tyrosine 248 in the cytoplasmic tail of HLA-DMB was mutated to an alanine to target DM to the cell surface. (B) Cell surface expression of sDM in the mouse B cell line (CH27) transfected with wild-type HLA-DMA and Y248A HLA-DMB. Stably transfected clones were stained for sDM with an antibody against DM (MaP.DM1) or an isotype control (Mags. DO5).

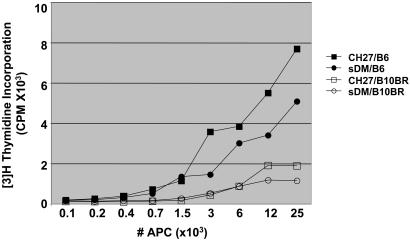

Titrated numbers of stimulators (either sDM-transfected or nontransfected CH27 cells) were incubated with responder T cells harvested from the lymph nodes of either C57BL/6 (H-2b) or B10.BR (H-2k) mice. We first confirmed that the CH27 B cell line was an efficient stimulator of naive T cells by measuring the response of T cells harvested from C57BL/6 to H-2k MHC expressed by CH27. As shown in Fig. 2, T cells from B6 mice responded strongly to both CH27 and sDM-transfected CH27 stimulators. The addition of anti-CD28 did not enhance the T cell response (data not shown). We next asked whether T cells from H-2k, B10.BR mice would recognize and respond to sDM as a non-self-MHC molecule. Because DM is not expressed at the cell surface in the thymus, T cells should not be tolerant to this molecule. Even if central tolerance to endogenous H-2M occurs, the human version of the molecule should be sufficiently different from mouse H-2M to induce proliferation. Surprisingly, there was no measurable T cell response to the MHC-like sDM molecule.

Fig. 2.

Naive T cells are not activated by surface DM. LN cells from B6 or B10.BR mice were incubated with CH27 or sDM transfected cells for 72 h, then pulsed with [3H]thymidine. Incorporation of [3H]thymidine was measured 95 h after pulse. The graph shows the level of radioactive thymidine incorporation in B6 LN cells incubated with CH27 (▪) or sDM-transfected CH27 (•) cells. B10.BR LN cells incubated with CH27 (□) or sDM-transfected CH27 (○) cells show a minimal proliferation.

Generation of K14-sDM Mice. Failure of naive T cells to respond to sDM may simply be due to the skewing of the mature T cell population for recognition of conventional self-MHC that occurs as a result of intrathymic positive selection. In other words, recombination of TCR gene segments might produce TCRs that can interact with DM, but these TCRs fail positive selection. Therefore, to determine whether the preselection TCR repertoire contains TCRs that can interact with our MHC mimic, we generated transgenic mice that express DM at the surface of thymic cortical epithelial cells. The DM genes shown in Fig. 1 were placed under the control of the K14 promoter, directing expression of sDM to cortical epithelial cells (23). Three transgenic founder lines were generated, two of which were backcrossed to the MHC double knockout mice. The founder line with higher expression levels of sDM was used for the studies reported here. Otherwise, the phenotype of both founder lines was identical.

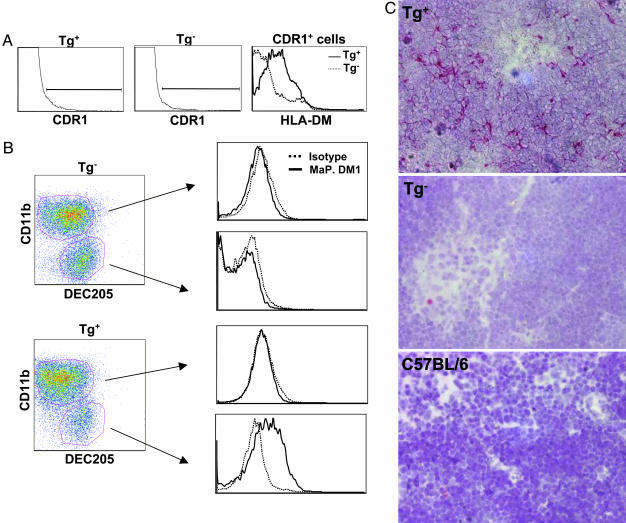

Thymic stromal cells were isolated from K14-sDM and nontransgenic control mice and labeled with mAbs specific for thymic epithelial cells (CDR1) (27) and DM (MaP.DM1). FACS analysis of total thymic stromal cells showed that DM was expressed only on the CDR1-positive cells in K14-sDM mice in comparison with MHC double-deficient mice (Fig. 3A). Because thymic stromal cells include a high proportion of autofluorescent macrophages and epithelial cells (27), ex vivo staining of stromal cells for certain markers does not always yield a conclusive result. Therefore, to confirm the exclusive expression of sDM on the cortical epithelial cells in transgenic mice, thymic stromal cells were cultured in vitro and analyzed by FACS for sDM expression. To enrich for thymic epithelial cells, nonadherent cells were removed during culture, and only the remaining adherent cells were taken for further analyses. Macrophages and epithelial cells were identified by staining with antibodies against CD11b and DEC205, respectively (28). In MHC double-deficient mice, both populations of cells (CD11b+DEC205- and CD11b-DEC205+) did not show sDM expression on the cell surface, as expected (Fig. 3B Upper). In mice carrying the K14-sDM transgenes, however, sDM expression was detected on the epithelial (CD11b-DEC205+) cell population (Fig. 3B Lower).

Fig. 3.

sDM expression in K14-sDM-transgenic (Tg) mice. (A) Thymic stromal cells prepared from K14-sDM and MHC double knockout mice were stained with antibodies against CDR1 and DM. CDR1+ cells from transgenic-positive (Tg+) and transgenic-negative (Tg-) mice were compared for sDM expression. (B) Thymic stromal cells from K14-sDM and MHC double knockout mice were cultured to enrich for adherent cells. Cells were identified by staining with anti-CD11b for macrophages or the cortical epithelial cell marker DEC205. Cell surface expression of sDM was compared in each population. (C) Detection of HLA-DM in situ. Thymic sections from K14-sDM and MHC double knockout and C57BL/6 mice were immunohistochemically stained for DM. Cortical epithelial cells in K14-sDM mice are stained in red. (Magnification: ×200.)

Finally, the exclusive expression of sDM on the cortical epithelial cells in K14-sDM mice was shown by immunohistochemical staining of thymic tissue sections. Whereas C57BL/6 and MHC double-deficient mice show no staining for DM, there was specific staining visible in the K14-sDM mice throughout the cortical area (Fig. 3C). All together, our flow cytometric and immunohistochemical analyses clearly demonstrate that sDM is expressed on the cortical epithelial cells of mice carrying the K14-sDM transgene.

Failure of Positive Selection of Thymocytes in K14-sDM Mice. We next analyzed thymocytes from the K14-sDM mice for the expression of cell surface markers that are indicative of their developmental stages. Thymocytes from K14-sDM mice showed a developmental arrest at the DP stage and did not develop further to single-positive cells. This result is comparable to thymocytes in the control MHC double knockout mice (Fig. 4A). DP cells change their cell surface phenotype during their maturation to SP cells: immature cells are CD24hiCD69-, cells undergoing positive selection are CD24hiCD69+, and mature cells down-regulate these markers (CD24loCD69-). Our FACS analyses revealed that DP cells from K14-sDM mice do not mature and remain at the CD24hi immature stage (Fig. 4B), similar to the developmental block that was observed in the MHC double knockout mice. TCR expression levels on thymocytes from K14-sDM and MHC double knockout mice also did not show any difference (Fig. 4C). Our results demonstrate that the presence of sDM, a structural homologue of MHC class II, was not sufficient for thymocyte development beyond the CD4+CD8+ stage. Finally, immunization of the K14-sDM mice with the sDM-transfected CH27 cell line, followed by in vitro bulk culture and restimulation with sDM-expressing cells, did not produce a sDM-specific T cell response (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Deficient positive selection of thymocytes in K14-sDM mice. Thymocytes from C57BL/6, K14-sDM, or MHC double knockout mice were stained for CD4, CD8, CD24, CD69, and TCR. (A) CD4 and CD8 staining profile in C57BL/6 (Left), K14-sDM (Center), and MHC double knockout mice (Right). (B) DP cells were gated and analyzed for CD24 and CD69 expression. (C) Expression level of TCR was analyzed in total thymocytes from K14-sDM and MHC double knockout mice.

Is It More than MHC Class II Structure? The ability of T cells to functionally interact with hundreds of different classical MHC class I and II alleles to which are bound thousands of different self-peptides clearly demonstrates the flexibility of the preselection TCR repertoire. The broad range of ligands recognized by the TCR, including nonclassical MHC class Ib-encoded proteins such as H-2M3 and HLA-E/Qa1 and non-MHC encoded genes such as CD1d, further highlights the flexibility of this receptor. The accommodation of such a wide variety of ligands is, of course, made possible by the vast combinatorial diversity of the TCR, estimated to be as much as a trillion trillion (1018) possible different TCRs (29).

TCR-MHC interactions are remarkably evolutionarily conserved, as was recently demonstrated when it was shown that human T cells can be efficiently positively selected in the mouse thymus (30). It also has been shown that both human and porcine MHC molecules can serve as functional ligands for mouse-encoded TCRs (31-33). Such interactions seem to be due to inherent specificities of the germ-line-encoded regions of TCR genes for MHC. Hardwired recognition of MHC was most convincingly shown by Zerrahn et al. (13) with a system that derived T cells from MHC-deficient mice by driving maturation with antibodies against the TCR and CD4. These T cells were shown to respond to other MHC alleles with the same frequency as T cells selected on MHC. It has even been shown that mice expressing β/β homodimers of MHC class II, clearly a structure that has an altered TCR contact area, have appreciable levels of positive selection (10). Furthermore, these T cells were reactive to other alleles of MHC, again demonstrating TCR specificity for MHC that is not dependent on normal positive selection. Overall, therefore, it seems many MHC-like structures are able to appropriately interact with developing T cells and promote their maturation. These molecules, however, have been under evolutionary pressure to maintain functional reactivity with TCRs.

It was, therefore, tantalizing to study the contribution of an MHC-encoded molecule that has maintained the tertiary structure associated with MHC class II (18), yet has diverged in its primary amino acid sequence. DM, as a consequence of its specialized intracellular function, meets these criteria. DM is missing two prominent features associated with MHC molecules: a peptide-binding groove and a coreceptor interaction domain, either of which might be considered sufficient for blocking TCR interactions. Positive selection, however, is also mediated by both CD1d molecules and I-A β chain homodimers, neither of which presents self-peptides. It has even been shown that in vivo selection of CD8+ T cells can be mediated by MHC class I molecules that may be devoid of peptides (34, 35). Several studies have also demonstrated that mutating the CD4-binding site (36-38) or eliminating CD4 completely (39, 40) reduces, but does not eliminate, positive selection. Therefore, the lack of these two features is not the reason for the failure of TCR interactions with DM.

Overall, our analysis demonstrates that an MHC class II mimic is not sufficient to appropriately interact with the TCRs expressed by developing thymocytes in the mouse. These data suggest that TCR contacts with conserved MHC residues or perhaps the features of the MHC main chain are required for positive selection of T cells and that these contacts are presumably maintained by evolutionary pressures placed upon these receptors and their selecting ligands. Comparisons of multiple MHC structures coupled with site-directed mutagenesis would likely reveal the nature of these conserved interactions.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Saylor and L. Vargas for technical support and L. Denzin and A. Stolzer for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank C. Janeway, Jr., for pointing out the roads but letting us choose the one to travel: and that has made all the difference. This work was supported in part by Public Health Service Grant R01 AI41574, the Roberta C. Rudin Leukemia Research Fund, and funds from the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

Author contributions: H.-J.K. and D.B.S. designed research; H.-J.K. and D.G. performed research; H.-J.K., D.G., and D.B.S. analyzed data; D.G. and D.B.S. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; and H.-J.K. and D.B.S. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: K14, keratin 14; DM, HLA-DM; sDM, surface DM; TCR, T cell antigen receptor; DP, double-positive.

References

- 1.Kisielow, P. & von Boehmer, H. (1995) Adv. Immunol. 58, 87-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sebzda, E., Mariathasan, S., Ohteki, T., Jones, R., Bachmann, M. F. & Ohashi, P. S. (1999) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 17, 829-874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ignatowicz, L., Kappler, J. & Marrack, P. (1996) Cell 84, 521-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sant'Angelo, D. B., Waterbury, P. G., Cohen, B. E., Martin, W. D., Van Kaer, L., Hayday, A. C. & Janeway, C. A., Jr. (1997) Immunity 7, 517-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surh, C. D., Lee, D. S., Fung-Leung, W. P., Karlsson, L. & Sprent, J. (1997) Immunity 7, 209-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grubin, C. E., Kovats, S., deRoos, P. & Rudensky, A. Y. (1997) Immunity 7, 197-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reinherz, E. L., Tan, K., Tang, L., Kern, P., Liu, J., Xiong, Y., Hussey, R. E., Smolyar, A., Hare, B., Zhang, R., et al. (1999) Science 286, 1913-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bendelac, A., Lantz, O., Quimby, M. E., Yewdell, J. W., Bennink, J. R. & Brutkiewicz, R. R. (1995) Science 268, 863-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ploss, A., Lauvau, G., Contos, B., Kerksiek, K. M., Guirnalda, P. D., Leiner, I., Lenz, L. L., Bevan, M. J. & Pamer, E. G. (2003) J. Immunol. 171, 5948-5955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vidovic, D., Boulanger, N., Kuye, O., Toral, J., Ito, K., Guenot, J., Bluethmann, H. & Nagy, Z. A. (1997) Immunogenetics 45, 325-335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jerne, N. K. (1971) Eur. J. Immunol. 1, 1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huseby, E., Kappler, J. & Marrack, P. (2004) Eur. J. Immunol. 34, 1243-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zerrahn, J., Held, W. & Raulet, D. H. (1997) Cell 88, 627-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackman, M., Yague, J., Kubo, R., Gay, D., Coleclough, C., Palmer, E., Kappler, J. & Marrack, P. (1986) Cell 47, 349-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierre, P., Denzin, L. K., Hammond, C., Drake, J. R., Amigorena, S., Cresswell, P. & Mellman, I. (1996) Immunity 4, 229-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marks, M. S., Roche, P. A., van Donselaar, E., Woodruff, L., Peters, P. J. & Bonifacino, J. S. (1995) J. Cell Biol. 131, 351-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindstedt, R., Liljedahl, M., Peleraux, A., Peterson, P. A. & Karlsson, L. (1995) Immunity 3, 561-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fremont, D. H., Crawford, F., Marrack, P., Hendrickson, W. A. & Kappler, J. (1998) Immunity 9, 385-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosyak, L., Zaller, D. M. & Wiley, D. C. (1998) Immunity 9, 377-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janeway, C. A., Chervonsky, A. V. & Sant'Angelo, D. (1997) Curr. Biol. 7, R299-R300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Denzin, L. K., Robbins, N. F., Carboy-Newcomb, C. & Cresswell, P. (1994) Immunity 1, 595-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dao, T., Blander, J. M. & Sant'Angelo, D. B. (2003) J. Immunol. 170, 48-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laufer, T. M., DeKoning, J., Markowitz, J. S., Lo, D. & Glimcher, L. H. (1996) Nature 383, 81-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammond, C., Denzin, L. K., Pan, M., Griffith, J. M., Geuze, H. J. & Cresswell, P. (1998) J. Immunol. 161, 3282-3291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roche, P. A. (1995) Immunity 3, 259-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alfonso, C. & Karlsson, L. (2000) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 113-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gray, D. H., Chidgey, A. P. & Boyd, R. L. (2002) J. Immunol. Methods 260, 15-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang, W., Swiggard, W. J., Heufler, C., Peng, M., Mirza, A., Steinman, R. M. & Nussenzweig, M. C. (1995) Nature 375, 151-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janeway, C. A., Jr., Travers, P., Walport, M. & Schlomchik, M. (2005) in Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease (Garland, New York), 6th Ed., pp. 135-168.

- 30.Traggiai, E., Chicha, L., Mazzucchelli, L., Bronz, L., Piffaretti, J. C., Lanzavecchia, A. & Manz, M. G. (2004) Science 304, 104-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.David, C. S. & Taneja, V. (2004) Am. J. Med. Sci. 327, 180-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roddis, M., Carter, R. W., Sun, M. Y., Weissensteiner, T., McMichael, A. J., Bowness, P. & Bodmer, H. C. (2004) J. Immunol. 172, 155-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao, Y., Fishman, J. A., Sergio, J. J., Oliveros, J. L., Pearson, D. A., Szot, G. L., Wilkinson, R. A., Arn, J. S., Sachs, D. H. & Sykes, M. (1997) J. Immunol. 158, 1641-1649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martien van Santen, H., Woolsey, A., Rickardt, P. G., Van Kaer, L., Baas, E. J., Berns, A., Tonegawa, S. & Ploegh, H. L. (1995) J. Exp. Med. 181, 787-792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schumacher, T. N. & Ploegh, H. L. (1994) Immunity 1, 721-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilfillan, S., Shen, X. & Konig, R. (1998) J. Immunol. 161, 6629-6637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yelon, D., Schaefer, K. L. & Berg, L. J. (1999) J. Immunol. 162, 1348-1358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riberdy, J. M., Mostaghel, E. & Doyle, C. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 4493-4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Locksley, R. M., Reiner, S. L., Hatam, F., Littman, D. R. & Killeen, N. (1993) Science 261, 1448-1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tyznik, A. J., Sun, J. C. & Bevan, M. J. (2004) J. Exp. Med. 199, 559-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]