SUMMARY

Introduction

In the 2022–23 Mpox outbreak, cases also occurred in children, adolescents, and adults aged 50 years and older, for whom the risk of transmission is low and whose epidemiological characteristics are less known, compared to high-risk groups such as young adults. Here we describe the epidemiological characteristics of Mpox in children, adolescents and adults aged 50 years and older in the global Mpox outbreak.

Methods

A retrospective study on laboratory-confirmed surveillance data of Mpox cases reported to World Health Organization (WHO) was conducted. Case data from WHO’s 2022–23 Mpox Outbreak: Global Trends from 1 January 2022 to 1 September 2023 was used for our analysis. We included cases reported by WHO with data on age (children [range, 0 to 9 years], adolescents [range, 10 to 17 years], adults 50 to 59 years, and adults 60 years and older), gender, WHO region, hospital admission, and intensive care unit admission.

Results

Until September 01, 2023, data from 89,752 cases of Mpox have been reported to WHO. Of all the reported cases, 1124 (1.3%), 6296 (7.0%) and 1501 (1.6%) were children and adolescents, adults aged 50–59 years, and adults aged 60 years or older, respectively, and the proportion varied among WHO regions. There was a high proportion of cases among population aged 0–17 years, adolescents (256 [66.3%]) from the region of the Americas and girls aged 0–9 years [127 (46.7%)] from the African region. Men aged 50–59 years (3495 [57.2%] vs. 2553 [41.8%] cases from the region of the Americas and the European region, respectively) and men aged 60–69 years (639 [60.0%] vs. 607 [48.4%] from the region of the Americas and the European region) were most affected, compared to other age groups and women. Among children, adolescents, and adults aged 50 years or older, a low proportion of cases developed some complications and required hospital admission, and some cases were admitted to the intensive care unit.

Conclusions

Epidemiological evidence of Mpox in these low-risk groups highlights the risk of wider community transmission. Therefore, while efforts continue to control the global outbreak of Mpox in high-risk groups, it is also necessary to ensure that these low-risk groups have access to timely health care and vaccination.

Keywords: Monkeypox, children, adults, older adults, outbreak, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Monkeypox (Mpox) is a zoonotic infection that can be transmitted between humans through droplet exposure or direct contact with infectious materials or infected fluids [1–3]. Since 1970, Mpox cases have occurred primarily in Central and West Africa, with sporadic transmission to the human population [4, 5]. From May 2022, non-endemic countries reported sustained community transmission and outbreaks to World Health Organization (WHO) and a high proportion of cases have spread quickly to all continents [6, 7]. For this reason, Mpox was declared as an international public health emergency by the WHO in July 2022 [1, 8].

In the global outbreak, young adults, men who have sex with men (MSM) and ethnic minorities were disproportionately affected [8–10]. In this outbreak, cases have also occurred in low-risk groups such as children, adolescents, adults aged 50–59 years and older adults for whom the risk of transmission is low and whose epidemiological characteristics are less well known [7, 8]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States of America, cases of Mpox in children and adolescents are uncommon, often limited to local or national contexts, and the disease tends not to be severe [11–13]. However, a previous study reported that children aged <5 years and older adults have a higher risk of hospitalization due to Mpox [8]. In children, household contact with the virus appears to be the main mode of transmission. In adolescents and in other age groups such as adults, sexual contact appears to be the main mode of transmission [8]. However, there are not enough studies on this [8]. To date, there are no clinical or outcome data for any of these lowrisk groups because comparisons are difficult. Therefore, it’s difficult to draw conclusions for these low-risk groups. In this context, describing the epidemiological characteristics of Mpox in lowrisk groups has important implications for case detection, contact tracing, risk communication, clinical care, improved access to healthcare and vaccination, epidemiological surveillance, prevention and control in different contexts.

In this study, we describe the epidemiological characteristics of Mpox infection in children, adolescents and adults aged 50 years and older in the global Mpox outbreak.

METHODS

Design and population

This retrospective study is an analysis based on surveillance data on laboratory-confirmed Mpox cases reported to WHO by Member States and their countries. WHO collected data submitted by countries in different formats. A global surveillance system was established by WHO in May 2022. This system includes daily combined numbers of cases by country and WHO region from 1 January 2022 to 1 September 2023. Institutional review board approval and informed consent were not required for this study because we used available online data from the WHO.

Source of data

We used case data from the 2022–23 Mpox outbreak: Global Trends from WHO [7]. The WHO report focuses on laboratory-confirmed cases according to the WHO working case definition published in the surveillance, case investigation, and contact tracing for Mpox interim guidance [7, 14]. Mpox cases reported to WHO with information on age (population from 0 to 17 years, and adults aged 50 years and older), sex, WHO region region of the Americas, European region, Western pacific region, South-east Asia region, and African region), hospitalization and intensive care unit (ICU) admission were examined. People aged 0–17 years were divided into two groups according to gender: children aged 0–9 years and adolescents aged 10–17 years. Adult people were divided into two groups: adults aged 50–59 years and older adults ≥60 years. In addition, adult persons were divided into four age groups according to their sex: adults aged 50–59 years, 60–69 years, 70–79 years and ≥80 years.

Statistical analysis

Our analysis was limited to a descriptive analysis of the epidemiological characteristics of Mpox in children, adolescents, and adults aged 50 years and older, using laboratory-confirmed Mpox cases reported from 1 January 2022 to 1 September 2023. Age groups were compared with other variables. Age-stratified categorical data (for children, adolescents and adults aged 50 years and older) including sex, WHO region, hospitalization and ICU admission were summarized in frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between groups were made using the Fisher’s exact test or the Chi-Squared test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analyses were conducted with StataSE 17.0.

RESULTS

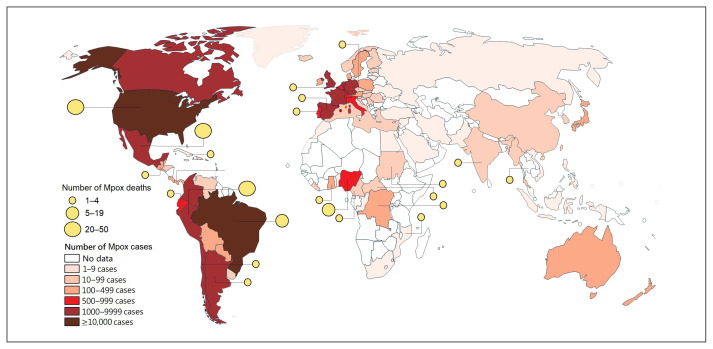

Between 1 January 2022 and 1 September 2023, 89752 laboratory-confirmed cases of Mpox and 157 deaths were reported to WHO from 114 countries in the six WHO regions (Figure 1). Of all cases reported to WHO, 1124 (1.3%) were children aged 0–9 years and adolescents aged 10–17 years (males n=667, females n=457), 6296 (7.0%) adults aged 50–59 years (males n=6105, females n=191), and 1501 (1.6%) adults aged ≥60 years (males n=1415, females n=86). Therefore, a total of 8921 cases from five WHO regions were included in the analysis.

Figure 1.

Global distribution of Mpox laboratory-confirmed cases and deaths among January 01, 2022 to September 01, 2023 (accessed on 01 September 2023) [7, 15].

Mpox in children and adolescents

Compared with children, there was a high proportion of cases in male adolescents (P<0.00001). The proportion of children and adolescents with Mpox infection varied by WHO region (P<0.00001), with higher proportions in the region of the Americas (310 [55.4%] vs. 379 [67.2%] in children and adolescents, respectively) and the African region (217 [38.8%] vs. 122 [21.6%] in children and adolescents, respectively). Forty-seven (21 [3.8%] vs. 26 [4.6%] in children and adolescents, respectively; P=0.471) cases had complications that required hospital admission, and only one child under 10 years cases (0.35%) was admitted to the ICU. There was a high proportion of cases in male adolescents aged 10–17 years (256 [66.3%]) from the region of the Americas, and girls aged 0–9 years (127 [46.7%]) from the African region (Table 1).

Table 1.

Monkeypox cases in children and adolescents in 2022–23 global outbreak, from January 01, 2022 to September 1, 2023.

| Total | Children 0–9 years of age | Adolescents 10–17 years of age | P value † | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n (%) | 1124 (100) | 560 (49.8) | 564 (50.2) | |

| Sex, n (%) | <0.00001 | |||

| Male | 667 (59.3) | 281 (50.2) | 386 (68.4) | |

| Female | 457 (40.7) | 279 (49.8) | 178 (31.6) | |

| Region, n (%) | <0.00001 | |||

| Region of the Americas | 689 (61.3) | 310 (55.4) | 379 (67.2) | |

| African region | 339 (30.2) | 217 (38.8) | 122 (21.6) | |

| European region | 86 (7.7) | 26 (4.6) | 60 (10.6) | |

| Western pacific region | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.5) | |

| Hospitalized cases, n (%) | 0.471 | |||

| Yes | 47 (4.2) | 21 (3.8) | 26 (4.6) | |

| No | 1077 (95.8) | 539 (96.2) | 538 (95.4) | |

| ICU-admission, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 1 (0.1) | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| No | 1123 (99.9) | 559 (88.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Cases including risk groups, n (%)* | 933 (83.0) | 509 (90.9) | 424 (75.2) | |

| Cases excluding HSH, n (%)** | 191 (17.0) | 51 (9.1) | 140 (24.8) | |

| Male | Female | |||

| Children 0–9 years of age | Adolescents 10–17 years of age | Children 0–9 years of age | Adolescents 10–17 years of age | |

| Total cases, n (%) | 281 (25.0) | 386 (34.3) | 272 (24.2) | 178 (15.8) |

| Region, n (%) | ||||

| Region of the Americas | 177 (63.0) | 256 (66.3) | 133 (48.9) | 123 (69.1) |

| African region | 90 (32.0) | 76 (19.7) | 127 (46.7) | 46 (25.8) |

| European region | 14 (4.1) | 51 (13.2) | 12 (4.4) | 9 (5.0) |

| Western pacific region | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.78) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hospitalized cases, n (%) | 14 (4.1) | 23 (5.6) | 7 (2.6) | 3 (1.7) |

| ICU-admission, n (%) | 1 (0.35) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cases including risk groups, n (%)* | 250 (88.9) | 304 (78.8) | 252 (92.7) | 120 (67.4) |

| Cases excluding HSH, n (%)** | 31 (11.0) | 82 (21.2) | 20 (7.3) | 58 (32.6) |

Notes: Data are n (%). Surveillance data on people with confirmed-laboratory Mpox were obtained from the 2022–23 Mpox Outbreak: Global Trends from WHO. Other regions including, Western pacific region, South-east Asia region and African region. ICU=intensive care unit.

Risk groups including, men who have sex with men, men reported as bisexual, heterosexual, and lesbian (women who have sex with women).

The following outputs apply to cases that are not men who have sex with men, and sexual orientation is known.

Chi-Square test or Fisher exact test.

Mpox in adults aged 50 years or older

There was a high proportion of cases in men aged 50–59 years, compared with women (P<0.00001). The proportion of adults aged 50–59 years and adults ≥60 years differed between WHO regions (P=0.0008), with a higher proportion in the region of the Americas (3660 [52.9%] vs. 794 [58.1%] in adults aged 50–59 years and adults ≥60 years, respectively) and the European region (2575 [40.9%] vs. 695 [46.3%] in adults aged 50–59 years and adults ≥60 years, respectively). Three hundred and thirty-five (272 [4.3%] vs. 63 [4.2%] in adults aged 50–59 years and adults ≥60 years, respectively; P=0.832) cases developed some complications and required hospital admission, and only nine cases (0.1%) were admitted to the ICU (Table 2). In these two WHO regions, men aged 50–59 years (3495 [57.2%] cases in the region of the Americas and 2553 [41.8%] cases in the European region) and men aged 60–69 years (639 [60.0%] cases in the region of the Americas and 607 [48.4%] cases in the European region) were most affected, compared to other age groups and women (Table 2).

Table 2.

Monkeypox cases in adults aged 50 years or older in 2022–23 global outbreak, from January 1, 2022 to September 1, 2023.

| Total | Adults 50–59 years of age | Adults ≥60 years of age | P value † | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, n (%) | 7797 (100) | 6296 (80.7) | 1501 (19.3) | – | |

| Sex, n (%) | – | – | – | <0.00001 | |

| Male | 7520 (96.4) | 6105 (96.9) | 1415 (94.3) | – | |

| Female | 277 (3.6) | 191 (3.1) | 86 (5.7) | – | |

| Region, n (%) | – | – | – | 0.0008 | |

| Region of the Americas | 4454 (57.1) | 3660 (58.1) | 794 (52.9) | – | |

| European region | 3270 (41.9) | 2575 (40.9) | 695 (46.3) | – | |

| Other regions | 74 (0.94) | 60 (0.95) | 14 (0.93) | – | |

| Hospitalized cases, n (%) | – | – | – | 0.8320 | |

| Yes | 335 (4.3) | 272 (4.3) | 63 (4.2) | – | |

| No | 7462 (95.7) | 6024 (95.7) | 1438 (95.8) | – | |

| ICU-admission, n (%) | – | – | – | 0.0003 | |

| Yes | 9 (0.1) | 3 (0.05) | 6 (0.4) | – | |

| No | 7796 (99.9) | 6293 (99.95) | 1495 (99.6) | – | |

| Male | |||||

| Total | Aged 50–59 years | Aged 60–69 years | Aged 70–79 years | Aged ≥80 years | |

| Total cases, n (%) | 7520 (100) | 6105 (81.2) | 1253 (16.7) | 143 (1.90) | 19 (0.25) |

| Region, n (%) | – | – | – | ||

| Region of the Americas | 4216 (56.1) | 3495 (57.2) | 639 (60.0) | 73 (51.0) | 9 (47.40) |

| European region | 3237 (43.0) | 2553 (41.8) | 607 (48.44) | 68 (47.6) | 9 (47.40) |

| Western pacific region | 43 (0.57) | 33 (0.54) | 5 (0.39) | 5 (3.50) | 0 (0.0) |

| South-east Asia region | 9 (0.12) | 8 (0.13) | 1 (0.08) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| African region | 16 (0.21) | 15 (0.25) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.26) |

| Hospitalized cases, n (%) | 312 (4.15) | 258 (4.23) | 43 (3.43) | 7 (4.90) | 4 (21.0) |

| ICU-admission, n (%) | 3 (0.04) | 3 (0.05) | 3 (0.24) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cases including risk groups, n (%)* | 7174 (95.4) | 5846 (95.8) | 1183 (94.4) | 132 (92.30) | 13 (68.42) |

| Cases excluding HSH, n (%)** | 346 (4.60) | 259 (4.2) | 70 (5.60) | 11 (7.70) | 6 (31.60) |

| Female | |||||

| Total | Aged 50–59 years | Aged 60–69 years | Aged 70–79 years | Aged ≥80 years | |

| Total cases, n (%) | 277 (100) | 191 (69.0) | 50 (18.1) | 26 (9.4) | 10 (3.6) |

| Region, n (%) | – | – | – | – | |

| Region of the Americas | 238 (85.9) | 165 (86.4) | 42 (84.0) | 21 (80.8) | 10 (100) |

| European region | 33 (11.9) | 22 (11.5) | 6 (12.0) | 5 (19.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Western pacific region | – | – | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| South-east Asia region | 2 (0.72) | – | 2 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| African region | 4 (1.44) | 4 (2.09) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hospitalized cases, n (%) | 23 (8.30) | 14 (7.32) | 4 (8.0) | 3 (11.5) | 2 (20) |

| Total | Adults 50–59 years of age | Adults ≥60 years of age | P value † | ||

| ICU-admission, n (%) | 3 (1.08) | – | 2 (4.0) | 1 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cases including risk groups, n (%)* | 160 (57.8) | 116 (60.7) | 26 (52.0) | 12 (46.1) | 6 (60) |

| Cases excluding HSH, n (%)** | 117 (42.2) | 75 (39.3) | 24 (48.0) | 14 (53.8) | 4 (40) |

Notes: Data are n (%). Surveillance data on people with confirmed-laboratory Mpox were obtained from the 2022–23 Mpox Outbreak: Global Trends from WHO. Other regions including, Western pacific region, South-east Asia region and African region. ICU=intensive care unit.

Risk groups including, men who have sex with men, men reported as bisexual, heterosexual, and lesbian (women who have sex with women).

The following outputs apply to cases that are not men who have sex with men (HSH), and sexual orientation is known.

Chi-Square test or Fisher exact test.

DISCUSSION

Compared with the high-risk groups as young adults, the epidemiological characteristics of Mpox infection in children, adolescents and adults aged 50 years and older are less well known. Because of this, we describe the epidemiological characteristics of Mpox infection in children, adolescents and adults aged 50 years and older in the global Mpox outbreak. In comparison with children, there was a high proportion of cases in adolescents from the region of the Americas, and in girls from Africa. There was also a high proportion of cases in men aged 50 years or older from the American and European regions, in comparison with women.

In this report, there are differences in the proportion of cases by sex and WHO region, although the proportion of reported cases was similar in children and adolescents. Our report shows an increase in Mpox cases in comparison with a previous report (from the beginning of the epidemic to January 2023), where the main route of transmission was contact with a person after birth or with contaminated material [8]. One possible explanation is that children and adolescents may be more susceptible to Orthopoxviruses because smallpox vaccination has not been available since 1980, which could lead to cross-protection against Mpox virus [16]. Because cases of Mpox have spread to non-endemic countries, transmission in children is likely to occur in community settings, ie at home, in kindergarten or at school, while transmission in adolescents is likely to occur through sexual contact [12, 17, 18]. In the current outbreak, more cases have been reported in children and adolescents in the region of the Americas than in Africa and Europe, where difficulties in clinical and laboratory diagnosis and access to treatment may be exacerbated by the stigma of disease transmission. In addition, the current number of cases in children and adolescents may be underestimated because of the limited capacity to respond to outbreaks in the countries of the region of the Americas. Therefore, although the number of cases is limited and the disease is less severe in this age group, health care providers (especially among sexually active adolescents) need to promote vaccination and information about testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases [19, 20]. In addition, countries should also strengthen public health response, early detection and isolation [21].

Between 1 January 2022 and 29 January 2023, 564 cases of Mpox in older adults were reported to WHO [8]. However, until 1 September 2023, the number of cases in older adults had almost tripled (n=1501). In contrast to previous outbreaks in endemic countries, in the current outbreak the largest proportion of cases has been reported in men aged 50–59 and 60–69 years in countries in the region of the Americas and Europe region [1, 5]. In these age groups, sexual contact seems to be the mode of transmission, as adults and older adults from some countries in these regions are sexually active, although there is a tendency for sexual activity to decrease with age [22–24]. In a previous report, transmission by sexual contact was observed in 1751 adults aged 50 years and older [8]. High rates of HIV infection have also been reported in adults aged 50 years and older from the United States [25]. As the risk of severe Mpox in men aged 50 to 59 years is lower in non-endemic countries than reported in at-risk populations, they may be considered a lower risk population for complications and mortality until more is known about clinical presentation, disease progression and treatment in this age group. The lower rate of complications in Mpox patients aged ≥50 years may be related to smallpox vaccination received in childhood before vaccination was discontinued, and that receiving JYNNEOS vaccines may provide additional protection [16, 25]. Despite this, preventive measures, including Mpox vaccination, may be warranted in this age group, as reported in the United States (27.6% of adults aged >50 have been vaccinated with JYNNEOS) [25]. Finally, findings of Mpox in men aged 50–59 and older highlight the risk of wider community transmission.

From a public health perspective, the Global Health Security (GHS) indicators, which assess various factors such as detection, prevention, reporting, health system, rapid response, international norms compliance, and risk environment, may also help to explain the high proportion of cases in low-risk groups in the region of the Americas [26]. A report has shown that the overall GHS index correlates with the rate of Mpox cases in the countries of the region of the Americas [15]. Thus, countries as the United States, Brazil, Peru and Colombia are the countries with the highest overall GHS indicators, and they have the highest case rates of Mpox cases in the region. One possible explanation is that countries with higher GHS index indicators have greater capacity for case detection, contact tracing and epidemiological surveillance, allowing identification and reporting of cases in these low-risk groups. This could also be the explanation for the high proportion of cases in countries in the European region, but to date there have been no studies that have explained this hypothesis.

Our study has several limitations. First, because access to diagnostic testing may be limited in resource-poor countries, the results may underestimate the true number of Mpox infections when relying on surveillance and laboratory reporting data. Second, the lack of contact tracing or the stigma associated with sexual transmission in low-income countries may need to be taken into account. Thirdly, the data analyzed did not allow the identification of the sources of transmission, which limits our findings.

CONCLUSIONS

In the current outbreak, cases of Mpox are rare among children, adolescents, adults aged 50 to 59 years, and older adults. Compared with children, there was a high proportion of cases in adolescents from the region of the Americas and girls from Africa region. There was also a high proportion of cases in men aged 50 to 59 and 60 to 69 years from the region of the Americas and European region, compared with women. In these lower-risk groups, disease is not severe. However, differences in clinical presentation, diagnosis, outcome and case management of Mpox in these low-risk groups require further clinical research. While efforts to control the global spread of Mpox in high-risk groups are mandatory, countries should also strengthen their public health response capabilities, risk communication, clinical care, access and vaccination in lower-risk groups.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT: Max Carlos Ramírez-Soto: Conceived and designed the experiments. Max Carlos Ramírez-Soto and Hugo Arroyo Hernandez, analysis tools or data, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors agreed to be responsible for all aspects of the work to ensure the accuracy and integrity of the published manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding: This study received no funding.

Data availability statement

The data are publicly available in https://world-healthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/

REFERENCES

- 1. Mitjà O, Ogoina D, Titanji BK, et al. M. Monkeypox. Lancet. 2023;401(10370):60–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02075-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lum FM, Torres-Ruesta A, Tay MZ, et al. Monkeypox: disease epidemiology, host immunity and clinical interventions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22(10):597–613. doi: 10.1038/s41577-022-00775-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Farahat RA, Sah R, El-Sakka AA, et al. Human monkeypox disease (MPX) Infez Med. 2022;30(3):372–391. doi: 10.53854/liim-3003-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ejaz H, Junaid K, Younas S, et al. Emergence and dissemination of monkeypox, an intimidating global public health problem. J Infect Public Health. 2022;15(10):1156–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bunge EM, Hoet B, Chen L, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox. A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16:e0010141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0010141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Venkatesan P. Global monkeypox outbreak. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(7):950. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00379-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization (WHO) Monkeypox. Geneva: WHO; 2022. [accessed on 25 April 2023]. WHO Health Emergency Dashboard. Available online: https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/ [Google Scholar]

- 8. Laurenson-Schafer H, Sklenovská N, Hoxha A, et al. Description of the first global outbreak of mpox: an analysis of global surveillance data. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11:e1012–e1023. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00198-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Amer FA, Hammad NM, Wegdan AA, ElBadawy NE, Pagliano P, Rodríguez-Morales A. Growing shreds of evidence for monkeypox to be a sexually transmitted infection. Infez Med. 2022;30(3):323–327. doi: 10.53854/liim-3003-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Antinori S, Casalini G, Giacomelli A, Rodriguez-Morales AJ. Update on Mpox: a brief narrative review. Infez Med. 2023;31(3):269–276. doi: 10.53854/liim-3103-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.CDC. Clinical Considerations for Mpox in Children and Adolescents. [access, September 1, 2023]. Updated Available in https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/pediatric.html.

- 12. Aguilera-Alonso D, Alonso-Cadenas JA, Roguera-Sopena M, Lorusso N, Miguel LGS, Calvo C. Monkeypox virus infections in children in Spain during the first months of the 2022 outbreak. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6(11):e22–e23. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00250-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Suvvari TK, Sandeep M, Kumar J, et al. A meta-analysis and mapping of global mpox infection among children and adolescents. Rev Med Virol. 2023;33(5):e2472. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guarducci G, Porchia BR, Lorenzini C, Nante N. Overview of case definitions and contact tracing indications in the 2022 monkeypox outbreak. Infez Med. 2023;31(1):13–19. doi: 10.53854/liim-3101-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ramírez-Soto MC. Monkeypox Outbreak in Peru. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023;59(6):1096. doi: 10.3390/medicina59061096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sanz-Muñoz I, Sánchez-dePrada L, Sánchez-Martínez J, et al. Possible mpox protection from smallpox vaccine-generated antibodies among older adults. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29:656–658. doi: 10.3201/eid2903.221231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khalil A, Samara A, O’Brien P, Ladhani SN. Monkeypox in children: Update on the current outbreak and need for better reporting. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;22:100521. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hennessee I, Shelus V, McArdle CE, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical features of children and adolescents aged <18 Years with Monkeypox - United States, May 17–September 24, 2022. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:1407–1411. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7144a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tutu van Furth AM, van der Kuip M, van Els AL, et al. Paediatric monkeypox patient with unknown source of infection, the Netherlands, June 2022. Euro Surveill. 2022:27. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.29.2200552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maru V, Ghaffar UB, Rawat A, et al. Clinical and epidemiological interventions for Monkeypox management in children: a systematic review. Cureus. 2023;15(5):e38521. doi: 10.7759/cureus.38521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 21. Prins H, Coyer L, De Angelis S, Bluemel B, Cauchi D, Baka A. Evaluation of mpox contact tracing activities and data collection in EU/EEA countries during the 2022 multicountry outbreak in nonendemic countries. J Med Virol. 2024;96(1):e29352. doi: 10.1002/jmv.29352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee D, Nazroo J, O’Connor D, Blake M, Pendleton N. Sexual health and wellbeing among older men and women in England: findings from the English longitudinal study of aging. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45:133–144. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0465-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lindau S, Schumm L, Laumann E, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older Americans in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solway E, Clark S, Singer D, Kirch M, Malani P. Let’s talk about sex. University of Michigan National Poll on Health Aging; [Date: 2018]. http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/143212 . [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eustaquio PC, Salmon-Trejo LAT, McGuire LC, Ellington SR. Epidemiologic and Clinical Features of Mpox in Adults Aged >50 Years - United States, May 2022–May 2023. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:893–896. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7233a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nuclear Threat Initiative Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, The Economist Intelligence Unit. The Global Health Security Index [Internet] GHS Index. [accessed on 12 January 2024]. Available online: https://www.ghsindex.org/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are publicly available in https://world-healthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global/