Abstract

The accuracy of artificial intelligence-aided (AI) caries diagnosis can vary considerably depending on numerous factors. This review aimed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of AI models for caries detection and classification on bitewing radiographs. Publications after 2010 were screened in five databases. A customized risk of bias (RoB) assessment tool was developed and applied to the 14 articles that met the inclusion criteria out of 935 references. Dataset sizes ranged from 112 to 3686 radiographs. While 86 % of the studies reported a model with an accuracy of ≥80 %, most exhibited unclear or high risk of bias. Three studies compared the model’s diagnostic performance to dentists, in which the models consistently showed higher average sensitivity. Five studies were included in a bivariate diagnostic random-effects meta-analysis for overall caries detection. The diagnostic odds ratio was 55.8 (95 % CI= 28.8 – 108.3), and the summary sensitivity and specificity were 0.87 (0.76 – 0.94) and 0.89 (0.75 – 0.960), respectively. Independent meta-analyses for dentin and enamel caries detection were conducted and showed sensitivities of 0.84 (0.80 – 0.87) and 0.71 (0.66 – 0.75), respectively. Despite the promising diagnostic performance of AI models, the lack of high-quality, adequately reported, and externally validated studies highlight current challenges and future research needs.

Keywords: Dental caries, Reference standards, Diagnostic techniques and procedures, Assessment, Visual examination, Adjunct methods

1. Introduction

Early detection of proximal caries is crucial for timely treatment and safeguarding the best possible prognosis. Recent systematic reviews investigating the accuracy of unaided visual examination for the detection of enamel and dentin caries reported acceptable diagnostic accuracy [1], [2]. This renders dental radiography a valuable diagnostic aid to efficiently detect, diagnose, and monitor caries [3], [4]. It also renders the development of reliable tools to support the diagnosis process, such as artificial intelligence (AI) tools, of paramount importance. AI implementations in the dental field are growing steadily, and dental caries detection is one of the main areas of interest [5]. Numerous studies have investigated the diagnostic performance of AI models on all types of dental radiographs [5], [6]. The development of AI models for caries detection, especially from bitewing radiographs (BWR) is one of the promising endeavors of AI in dentistry.

It is known that the performance of AI models aimed at caries diagnosis can vary considerably depending on the algorithm used, the size and diversity of the included radiographic dataset, and the quality of the annotations, among other factors [6]. Each of these elements factors into the uncertainty surrounding the true robustness and consistency of this emerging technology. Given the vast number of publications, the highly dynamic nature of this field, and the importance of ensuring reliable detection of caries, a systematic appraisal of the diagnostic performance of these models is needed. Therefore, this systematic review aims to identify studies that used AI for caries detection on bitewing radiographs and evaluate study quality. Additionally, it also aimed to compile meta-analytic data regarding the diagnostic accuracy of these models.

2. Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the PRISMA-DTA guidelines [7] and was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (ID number: CRD42023424797).

2.1. Systematic search of the literature

This systematic review aimed to answer the following PIRD question: “What is the diagnostic performance of AI-based models (index test) for caries detection and/or classification (diagnosis of interest) on bitewing radiographs (population) in comparison to the reference standard (reference test)?” The PIRD question was searched in five different databases: Medline (via PubMed), Embase, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, and Google Scholar. The databases were searched using different combinations of search terms that were agreed upon based on the research question and eligibility criteria. The keywords used in the search are summarized in Table 1, and the search queries for the different databases and their results can be found in Appendix I of the supplemental material. All citation results from the databases were downloaded and merged into one folder in the reference management software EndNote X7 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). Furthermore, a hand search of the reference lists of the included references, journals of interest, and relevant reviews was performed. However, no search for gray literature was conducted. Articles identified via hand search were added to the rest of the records. Then, duplicate records were eliminated with the help of the bibliographic software.

Table 1.

Search terms and keywords used in the database search.

| Caries | Radiography | Artificial intelligence | Diagnosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| caries OR decay OR cavity OR dentin OR enamel | AND | radiograph* OR x-ray OR x ray OR bitewing OR bite wing OR bite-wing | AND | artificial intelligence OR deep learning OR machine learning OR computer vision OR neural network OR annotation OR NN | AND | detect* OR diagn* OR evaluat* OR localization OR segmentation OR classification OR performance OR accuracy OR sensitivity OR specificity OR reference |

The titles and abstracts of the resulting articles were examined according to the predefined eligibility criteria by two independent reviewers (N.A. and J.K.), and any disagreements were discussed until resolution. Reviewers were not blinded to the identifying data of the articles. After screening records and eliminating ineligible articles, the full texts were retrieved for the eligible ones. In case the article’s eligibility could not be determined solely from the title and abstract, its full text was examined for further evaluation. After viewing the full text articles, the reviewers made a final decision for inclusion or exclusion in consensus. The inclusion criteria were publications that developed an AI model to detect, classify, or segment caries, and reported the internal validation results. The studies must include an evaluation of the model’s diagnostic performance by comparing it to a reference standard. Due to the recent uprise of AI applications in dentistry, the search was limited to publications after 2010. Excluded studies were reviews, conference proceedings, editorials, and studies reported in languages other than English. Furthermore, studies that did not report sufficient details regarding the development and evaluation of the AI model or that did not separately report the model’s caries detection performance were excluded. Studies employing automated tools for annotation were also excluded from consideration.

2.2. Data collection

The two reviewers (N.A. and J.K.) extracted all relevant data from the included articles using a structured form. Disagreements and discrepancies were discussed until resolution. In summary, the following characteristics – if available – were extracted: bibliographic data, study design, type of neural network(s), number of bitewing radiographs used for training, validation, and testing of the model, dentition type, annotation type, annotation platform, number and experience of annotators, caries classification, image size alteration, and performance metrics. A data extraction template can be found in Appendix II of the supplemental material.

In an effort to pursue complete extraction of the sought data, different approaches were adopted. The first of these included directly contacting the corresponding author of the respective publications via e-mail. This was done for included studies that showed low/moderate RoB and did not explicitly report contingency table results. If no reply was received, a follow-up email was sent a few weeks later. In some instances, the outreach effort extended beyond the corresponding authors, by contacting other authors from the same publication to request the data. Furthermore, the reviewers examined the other AI-based dental diagnostics publications of the authors and workgroups associated with the included studies for any similarities or shared data that could aid in reconstructing the missing information.

2.3. Risk of bias assessment

Given the recent emergence of this technology in dentistry, a specialized Risk of Bias assessment (RoB) tool for evaluating the risk of bias was custom-made and applied to the included studies. The customized assessment tool can be found in Appendix III. Specifically, this assessment tool was based on the caries diagnostic studies RoB tool developed by Kühnisch et al. in 2019 [8]. This tool aimed to adapt the widely used evaluation tools for diagnostic accuracy studies; QUADAS-2 (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies) [8], [9] and the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual [10], [11] to the precise purpose of identifying potential biases in caries diagnostic studies which would otherwise not be comprehensively covered by QUADAS-2 alone. To achieve this, we employed the aforementioned caries diagnostic studies RoB tool and slightly modified it to better align with the nuanced intricacies associated with AI dental diagnostics. This customization was based on relevant checklists within the automated dental diagnostic field [12] and following the guidelines for qualitative study assessment [11], [13]. The resulting customized RoB tool consisted of 17 signaling questions organized into four domains: Population & image selection, Index test, Reference test, and Data analysis (flow and timing). The domains cover various sources of bias including selection bias, spectrum bias, blinding biases for the index and reference tests, misclassification bias, diagnostic review bias and incorporation biases, partial and differential verification biases, validity bias, and reproducibility bias. For each signalling question, one of three modalities (high, low, or unclear) was employed to assess the bias of the included articles. The category ‘unclear RoB’ was reserved for instances where the article provided insufficient or no information.

The RoB assessment was performed by two reviewers (N.A. and J.K.), and discrepancies were discussed and resolved within a larger workgroup until consensus resolution. Further examination was undertaken to choose studies for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Studies scoring low or moderate RoB in the major components (index test criteria, reference test criteria, incorporation bias, partial verification bias, and differential verification bias) were deemed acceptable for a meta-analysis.

2.4. Data handling, statistical procedures, and meta‐analysis

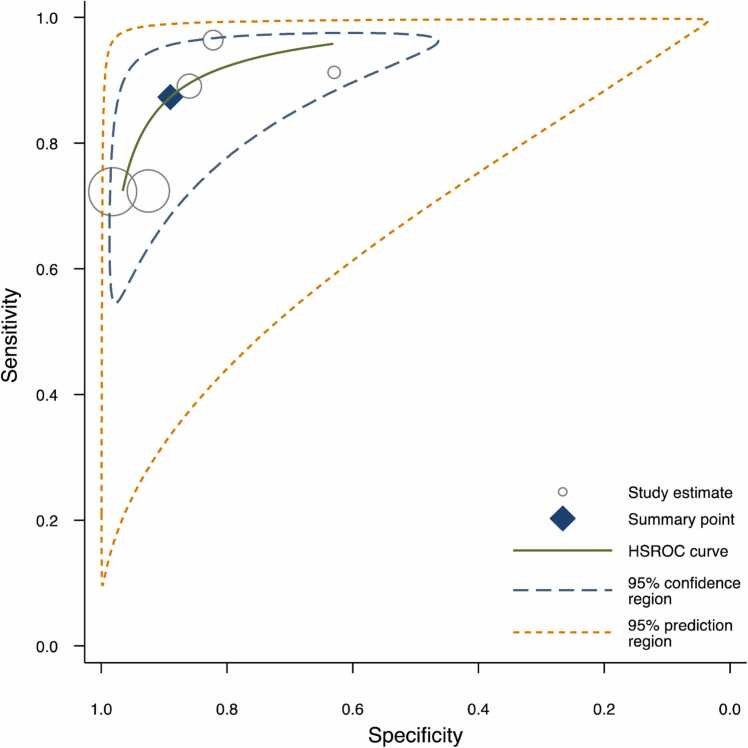

Data from the included studies were entered into Excel spreadsheets (Excel 2023, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and subsequently imported to Review Manager Web (RevMan Web version 6.0, The Cochrane Collaboration, available at revman.cochrane.org) for the RoB assessment. The meta-analyses were carried out using the statistical software program Stata (StataCorp. 2019, release 16, College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC, USA) in conjunction with the statistical packages metandi [14] and metadta [15]. For inclusion in the meta-analysis, studies had to show low or moderate RoB and report either complete contingency tables or the results for sensitivity (SE), specificity (SP), negative predictive value (NPV), positive predictive value (PPV), and caries prevalence to facilitate inclusion in the analysis. To calculate pooled SE and pooled SP estimates with a 95 % confidence interval (95 % CI), a bivariate diagnostic random-effects meta-analysis was used, and the pooled DOR was calculated [16]. A hierarchical summary receiver-operating characteristic curve (HSROC) and forest plot were generated to illustrate the diagnostic performance and differences between studies [17]. For studies reporting multiple AI models, only the best-performing model was included in the meta-analysis.

Utilizing both the bivariate diagnostic random-effects meta-analysis and HSROC models in the analysis offers several key benefits. Bivariate diagnostic random-effects meta-analysis accounts for the correlation between SE and SP while effectively addressing study heterogeneity, providing a robust assessment of diagnostic accuracy. On the other hand, HSROC allows for a more comprehensive exploration of diagnostic accuracy data. Together, these models provide a well-rounded analysis that enhances the depth and reliability of the findings. As the HSROC curve progresses toward the upper-left corner of the graph, the DOR increases, signifying a test with an enhanced ability to discriminate between disease and health conditions [18].

Furthermore, the diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) was calculated for any model in the included studies for which one of the following result pairs was reported: contingency tables, SE and SP, or PPV and NPV. For this meta-analysis, the diagnostic accuracy measures are reported per caries lesion. A sensitivity-specificity scatterplot was created to facilitate comparison between models in different studies, this was done using the statistical software R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.R-project.org/). Additional information obtained via author communication was incorporated in the analysis whenever possible. In instances where direct communication with the authors did not yield the required data, we resorted to utilizing the calculator function in RevMan, which employs equations to derive unreported data from the information that was available in the study. Studies with no or incomplete data were excluded from further analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Database search

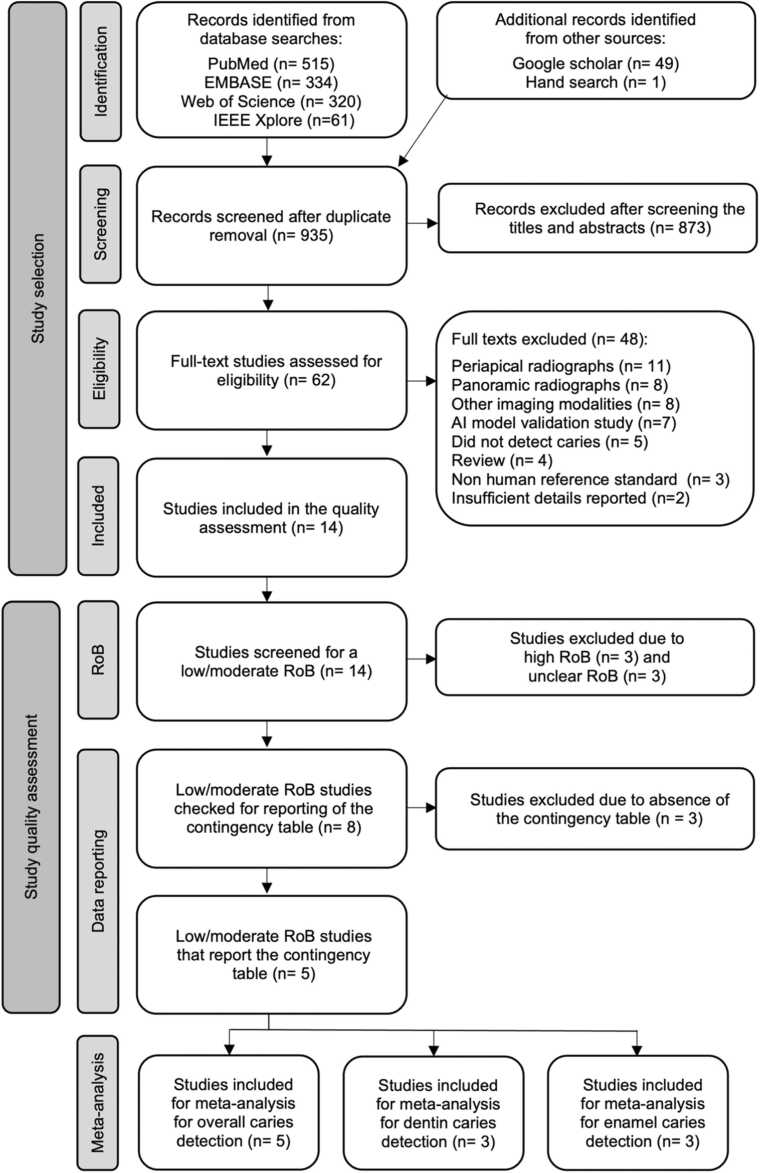

The database searches were conducted twice to ensure an updated view of the field. The first search was in April 2023, and the second was in November of the same year. The final database search yielded 935 unique citations. Of these, 62 potential references were identified, and 14 studies were included in the qualitative assessment (supplementary materials Appendix IV) [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32]. There were several reasons for study exclusion as listed in Appendix V. An overview of the study flow and eligibility assessment process is summarized in Fig. 1. Although the database search excluded only studies published before 2010, all included studies were published between 2020 and 2023.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram illustrating the search and study selection process.

3.2. Study characteristics

A wide range of neural networks were employed, of which the most prevalent was the U-Net architecture which was used in six studies. Eleven of the included studies (79 %) specified using a BWR dataset of permanent teeth, and the rest did not mention the type of dentition investigated. The dataset size ranged from 112 to 3686 BWR, and all but two studies detailed the eligibility criteria for the images used. The average number of dentists annotating the reference dataset was 2, with two studies reporting annotation by only one dentist. Furthermore, the annotators’ clinical experience ranged from 3 to 25 years. Half of the included classified caries lesions as either present or absent. A summary of the data extracted from the study is tabulated in Appendix VI of the supplementary materials.

Through author communications, we received the unreported contingency table data for three studies. One of which was successfully included in the meta-analyses for overall, dentin, and enamel caries detection [30]. However, it was not possible to include the other two studies. The exclusion of the other data received is attributed to the AI model design, which was trained to strictly identify abnormal tissue (caries). Consequently, these models were unable to detect healthy tissue, hence no ‘true negative’ values were available, which precludes their integration into the bivariate meta-analysis model [19], [28].

3.3. Qualitative and quantitative assessments

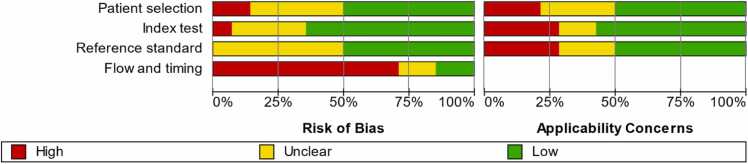

All included studies underwent qualitative assessment. Only one study demonstrated low RoB across all domains [23], while most studies showed signs of unclear or high RoB. The flow and timing domain was where most studies (86 %) showed high or unclear RoB. Evaluation of the RoB and concerns regarding applicability are summarized in Fig. 2. From the fourteen included studies, only four reported complete contingency tables, and a fifth study provided sufficient data to infer the table’s values. Given that these studies were deemed to show low/moderate risk of bias, they were chosen for the meta-analysis for overall caries detection. Furthermore, three of these studies classified the detected lesions and reported detailed confusion matrices, which allowed for an independent meta-analysis for the detection of dentin caries and another one for the detection of enamel caries (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Summary of the methodological quality assessment for the included studies. The red bar indicates high RoB, the yellow bar indicates unclear RoB and the green one indicates low RoB.

Table 2.

Reported contingency tables of studies included in the meta-analysis for the detection of overall, dentin, and enamel caries.

| Study | BWR in total dataset | BWR in test dataset | True positives | False positives | False negatives | True negatives |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall caries detection | ||||||

| Panyarak et al. 2023 | 2758 | 196 | 115 | 20 | 11 | 34 |

| Estai et al. 2022 | 2468 | 10-fold cross-validation | 293 | 49 | 36 | 301 |

| Suttapak et al. 2022 | 2250 | 450 | 347 | 16 | 13 | 74 |

| Bayraktar et al. 2022 | 1000 | 200 | 271 | 42 | 104 | 2283 |

| Chen et al. 2022 | 978 | 160 | 388 | 116 | 148 | 1435 |

| Dentin caries detection | ||||||

| Panyarak et al. 2023 | 2758 | 180 | 79 | 6 | 11 | 84 |

| Suttapak et al. 2022 | 2250 | 450 | 71 | 16 | 19 | 344 |

| Chen et al. 2022 | 978 | 160 | 225 | 163 | 44 | 72 |

| Enamel caries detection | ||||||

| Panyarak et al. 2023 | 2758 | 180 | 27 | 18 | 14 | 121 |

| Suttapak et al. 2022 | 2250 | 450 | 69 | 23 | 21 | 337 |

| Chen et al. 2022 | 978 | 160 | 163 | 225 | 72 | 44 |

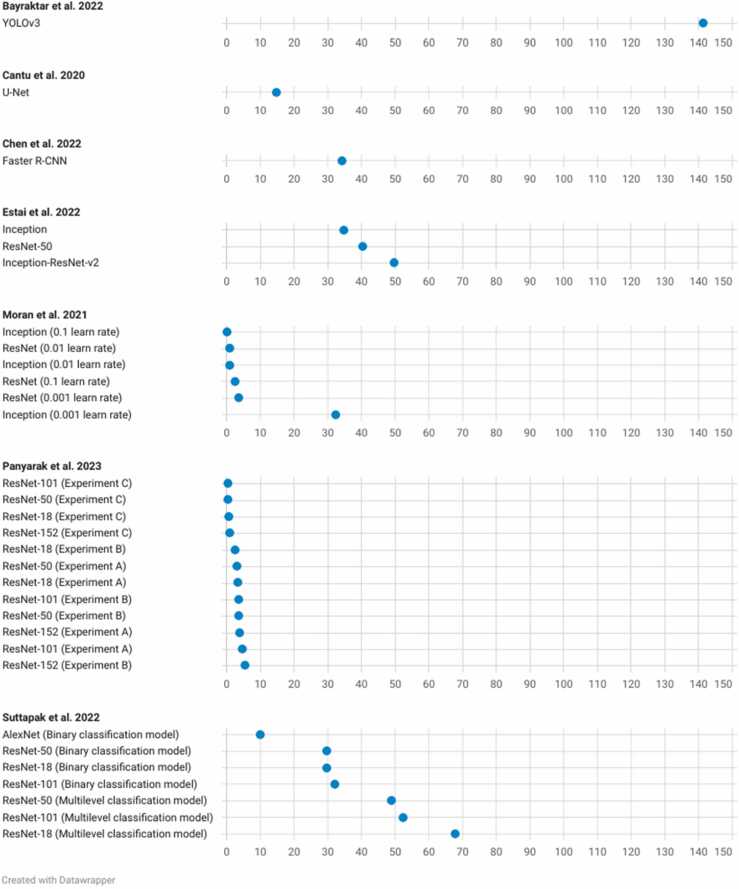

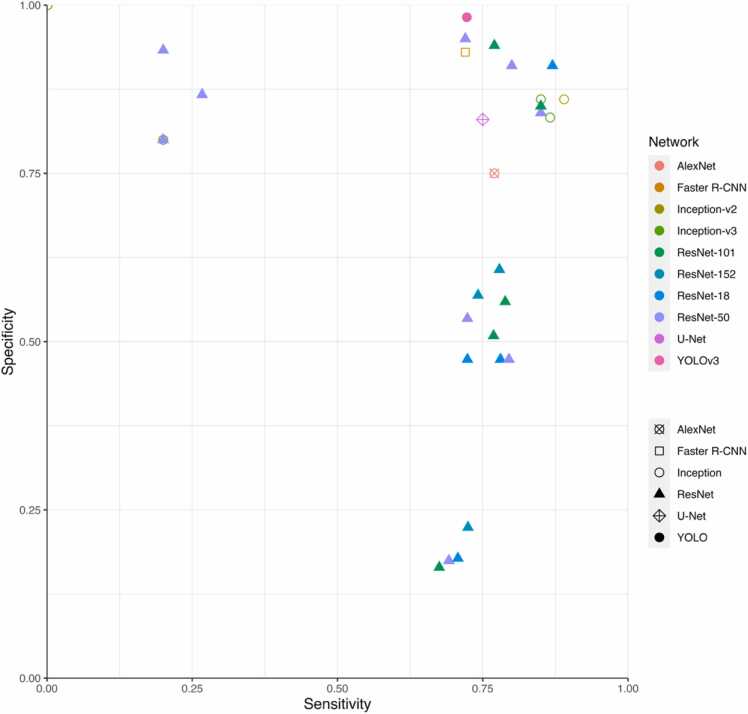

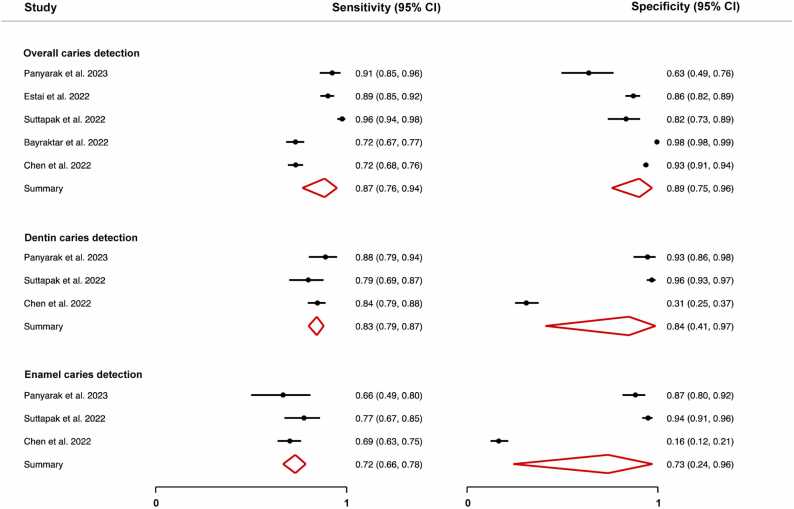

The DOR was calculated for the models for which the pertinent data were reported (Fig. 3). The scatterplot in Fig. 4 facilitates comparison between these different models. The reported DORs ranged from 0 to 141. For the meta-analysis, the highest diagnostic performance was observed for the overall detection of caries with a summary DOR (95 % CI) of 55.8 (28.8 – 108.3), while the lowest was for the detection of enamel caries. The forest plots for the three meta-analyses along with the summary statistics can be found in Fig. 5. The HSROC curve for overall caries detection is shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 3.

Dot plot displaying the DOR of some of the networks in the included studies.

Fig. 4.

Scatterplot showing the sensitivity and specificity results for some of the AI models reported in the included studies.

Fig. 5.

Forest plot for the meta-analyses for overall caries detection, dentin caries detection, and enamel caries detection showing the summary sensitivity and specificity for the included studies with the confidence interval (95 % CI).

Fig. 6.

HSROC curve showing the summary point for overall caries detection along with 95 % confidence region and 95 % prediction region estimates. The prediction region is the estimated 95 % probability range for the expected performance of future studies conducted similarly to those already analyzed.

3.4. Comparison to dentists

Three of the included studies used a hold-out dataset to compare the AI model’s diagnostic performance to that of dentists [21], [22], [23]. The models consistently exhibited higher sensitivity than the dentists. Notably, only one study used external data to validate the model's performance. When compared to the diagnostic performance achieved with internal data, this model showed diminished performance on the external data [20].

4. Discussion

BWRs are frequently recommended as a diagnostic aid to visual-tactile inspection for proximal decay detection [3], [4], [33]. As a result, these radiographs have garnered significant attention aimed at developing AI models that automate this procedure. To address the expanding body of literature, the present systematic review and meta-analysis synthesized and critically evaluated the available evidence regarding AI-based caries detection and classification from BWR.

The included studies showed a broad quality spectrum and only a few studies fulfilled the basic reporting requirements for diagnostic accuracy studies (Fig. 2). Most of the included studies showed high or unclear RoB, which is consistent with earlier reviews' conclusions that the overarching feature in most AI-based dental diagnosis studies is poor reporting quality [6]. Aside from reporting the AI algorithm used and its development, the majority of studies did not report external validation data. Only one study sought external validation for their model's performance, revealing diminished accuracy compared to the results reported for the internal dataset [20]. Since the reported models have not undergone testing as clinical tools, it is essential to recognize the limited understanding of how they would perform in actual clinical settings. Moreover, there remains uncertainty about potential underlying overfitting in the model. Future studies should seek external validation [10], [11], [12], [34], [35]. To enhance a model's generalizability, datasets should aim for maximum possible heterogeneity. This reinforces previous suggestions to share anonymized study datasets in open repositories, enabling external validation of models by other researchers [12].

The meta-analysis for overall caries detection revealed that using AI models for the detection of overall caries can yield greater accuracy than using intraoral radiography alone. The majority of the included studies reported an AI model with high accuracy (≥ 80 %), which is in line with the findings of previous reviews [6]. Generally, caries detection using intraoral radiography offers moderate SE (0.40 – 0.50) and high SP (0.80 – 0.90) [2], [4], [36]. As compared to conventional radiologic diagnosis, AI-supported caries diagnosis shows a promising increase in SE as shown by the summary SE of 0.87 (0.76 – 0.94) in Fig. 5. Furthermore, systematic reviews reveal that dental examination aided by radiographs results in caries DORs ranging between only 2.6 (0.80 – 8.20) and 17.11 (3.72 – 78.39), in comparison to 55.8 (28.8 – 108.3) as recorded with AI models included in the present review [2], [4], [36].

The outcomes of the meta-analyses concerning caries classification were in line with the typical clinical scenarios. Since identifying proximal enamel caries presents a greater challenge compared to diagnosing dentin caries, the summary SE for classifying dentin and enamel caries showed similar trends, recording SE of 0.84 (0.80 – 87) and 0.71 (0.66 – 75), respectively. This observation highlights the need to reinforce clinical diagnoses with reliable diagnostic aids to detect the early signs of decay.

Except for one study, all studies included in the meta-analysis reported an average SP that was equal to or exceeding 0.63. The specificity metrics reported by Chen et al., 2022 [23] for the detection of dentin and enamel caries were 0.31 (0.25 – 0.37) and 0.16 (0.12 – 0.21), respectively. Despite demonstrating good SP in overall caries detection and conforming with the trend of declining diagnostic performance in caries classification tasks, these findings deviate markedly from the average performance of the other studies included in the meta-analyses for caries classification (Fig. 5) [29], [30]. Valuable insights can be gained from examining the potential causes behind this outcome. The substantial decrease in SP while the SE remains relatively within range suggests that the test model becomes more permissive to classifying healthy tissue as carious (false positives) when tasked with caries classification. An increase in false positives is inversely related to SP. The discrepancy can be traced back to the annotation approach used . While the other studies in the meta-analysis explicitly annotated healthy tissues (true negatives) in their training sets, the study under consideration labelled carious tissue only. As a result, the developed AI model lacked a clear reference for distinguishing between healthy and carious tissues. This limitation was particularly pronounced in enamel caries classification, where the model faced challenges in discerning the subtle differences between sound surfaces and early lesions, leading to an increased misclassification rate and hence lower SP. This observation is also closely intertwined with the threshold selection for classifying test results as positive or negative. If the threshold was set too low, more cases may have been classified as positive, causing an increase in SE but a decrease in SP.

This observation underscores the critical need to include healthy tissue annotations (true negatives) in training datasets to improve the specificity of caries detection models. Given the diagnostic challenges posed by the elusive nature of early caries lesions, the absence of healthy tissue annotations hinders a comprehensive evaluation of a dental diagnostics model performance, particularly regarding specificity. It is essential to acknowledge this limitation, especially considering the well-recognized risks of overdiagnosis and consequently overtreatment.

Furthermore, data variability and possible class imbalances, as manifested by the prevalence of caries of different extensions in the training dataset, directly impact performance metrics. This is particularly relevant since Chen et al., 2022 report a caries prevalence of 24.8 % (in a total of 978 images) in the dataset in comparison to 41.7 % (in a total of 2758 images) reported by Panyarak et al., 2023 [30]. Finally, discrepancies in performance can be directly attributed to variations in AI model capabilities. Chen et al. employed the Faster R-CNN, while Suttapak et al., 2022 [29] utilized ResNet-101, and Panyarak et al., 2023 employed ResNet-152. The choice of different models introduces variations in complexity, with more layers typically indicating greater complexity and enhanced learning capabilities and performance.

Aside from technical specifications, several factors directly affect an AI model’s diagnostic performance. The professional background and clinical experience of the annotator(s) play a pivotal role. Several studies employed a single expert as the reference standard annotator, a choice that invites criticism due to the considerable variability in experts’ diagnoses. Any model trained on a single-annotator dataset will reflect the proficiency of this sole expert. Exclusively relying on a ‘fuzzy’ reference standard established by one dentist is likely to introduce bias in the model’s performance. Secondly, the size and diversity of the training dataset directly influence the model’s ability to reliably identify different lesions. Currently, there is no consensus regarding the minimum number of images needed to develop a reliable AI model, which further highlights the importance of external validation and testing. On an unrelated note, none of the included studies focused on developing AI models for caries detection in primary dentition. Considering the morphological and radiographic differences between primary and permanent dentitions, it is sensible to develop tailored models that address the unique diagnostic challenges in primary dentition.

There are several published systematic reviews investigating AI-based diagnosis of dental caries. To the best of our knowledge, there are none that focus exclusively on BWR [6], [37], [38], [39]. Several earlier systematic reviews focused on examining AI-based caries diagnosis across various types of radiographs. This wide-ranging inclusion of diverse diagnosis and radiography techniques contributed to heterogeneous datasets, which posed challenges for conducting a meta-analysis. We aimed to overcome these challenges in the present review by focusing solely on BWR. This relatively more homogeneous dataset made way for the quantitative summarization of the published data. Nonetheless, some degree of variability between the included studies remains, which we tried to overcome using a random effects meta-analysis model and a subgroup analysis for the different diagnostic thresholds, namely that of enamel and dentin caries.

From a methodological perspective, this review has strengths and limitations. Among its strengths is the comprehensive search of five of the largest scientific databases in the field, and the study selection process that adhered to a strict protocol to ensure the inclusion of studies with a moderate to low risk of bias. This approach led to the inclusion of studies of higher quality. However, it also resulted in a reduction in the number of studies included. Another noteworthy aspect of this review is the custom-made RoB assessment form, which was tailored to evaluate the unique characteristics of studies bridging the dental and AI research fields. On the other hand, it is essential to also acknowledge the limitations. The included studies showed a wide-ranging difference in data quality and reporting. Due to the compromised reporting quality, only five studies met the criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis. The limited number of studies included in the analysis restricts the generalizability of the meta-analytical findings. Additionally, conference publications, repositories, and grey literature were not included in this review. This omission may introduce publication bias, as we recognize the existence of several relevant publications from these sources in the field. Nevertheless, the deliberate decision to exclude these sources was aimed at concentrating on the methodological intricacies of the selected studies. These details would have been challenging to thoroughly assess in publications with incomplete or insufficient reporting. Furthermore, most studies included a relatively small dataset and used it to develop multiple algorithms, which may have overinflated the reported data. This warrants caution in interpreting conclusions derived from the meta-analyses.

5. Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis consolidated the existing evidence on AI-based caries detection and classification from BWR. The heightened sensitivity of AI models compared to dentists emphasizes their value as potential clinical diagnostic aids. However, challenges involving limited data for meta-analysis, lack of data on the specificity of the model in some studies, and the impact of the annotators’ expertise call for refining research methodologies and enhancing the curation of training datasets. Furthermore, the scarcity of high-quality, adequately reported, and externally validated studies highlights ongoing research needs. Overcoming these challenges is essential for advancing AI's diagnostic capabilities and improving patient care within the field of caries diagnostics.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Förderprogramm der Forschungsgemeinschaft Dental e.V. (FGD) für ausländische Gastwissenschaftler with grant number 01/2023 to N.A.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jdsr.2024.02.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Macey R., Walsh T., Riley P., Glenny A.M., Worthington H.V., O’Malley L., et al. Visual or visual‐tactile examination to detect and inform the diagnosis of enamel caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2021:CD014546. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janjic Rankovic M., Kapor S., Khazaei Y., Crispin A., Schüler I., Krause F., et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic studies of proximal surface caries. Clin Oral Invest. 2021;25:6069–6079. doi: 10.1007/S00784-021-04113-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kühnisch J., Ekstrand K.R., Pretty I., Twetman S., van Loveren C., Gizani S., et al. Best clinical practice guidance for management of early caries lesions in children and young adults: an EAPD policy document. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2016;17:3–12. doi: 10.1007/S40368-015-0218-4/METRICS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh T., Macey R., Riley P., Glenny A.M., Schwendicke F., Worthington H.V., et al. Imaging modalities to inform the detection and diagnosis of early caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;2021:CD014545. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD014545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Putra R.H., Doi C., Yoda N., Astuti E.R., Sasaki K. Current applications and development of artificial intelligence for digital dental radiography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2022;51:20210197. doi: 10.1259/DMFR.20210197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohammad-Rahimi H., Motamedian S.R., Rohban M.H., Krois J., Uribe S.E., Mahmoudinia E., et al. Deep learning for caries detection: a systematic review. J Dent. 2022;122 doi: 10.1016/J.JDENT.2022.104115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McInnes M.D.F., Moher D., Thombs B.D., McGrath T.A., Bossuyt P.M., Clifford T., et al. Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies: the PRISMA-DTA statement. JAMA. 2018;319:388–396. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2017.19163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiting P.F., Rutjes A.W.S., Westwood M.E., Mallett S., Deeks J.J., Reitsma J.B., et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiting P., Rutjes A.W.S., Reitsma J.B., Bossuyt P.M.M., Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Method. 2003;3:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-25/TABLES/1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell J.M., Klugar M., Ding S., Carmody D.P., Hakonsen S.J., Jadotte Y.T., et al. In: JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Aromataris E., Munn Z., editors. JBI; 2020. Chapter 9: Diagnostic test accuracy systematic reviews. 2020th ed. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters M., Godfrey C., McInerney P., Baldini S.C., Khalil H., Parker D. Methodology for JBI Scoping Reviews. The Joanna Briggs Institute; Adelaide, Australia: 2015. The Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwendicke F., Singh T., Lee J.H., Gaudin R., Chaurasia A., Wiegand T., et al. Artificial intelligence in dental research: Checklist for authors, reviewers, readers. J Dent. 2021;107 doi: 10.1016/J.JDENT.2021.103610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bossuyt P.M., Reitsma J.B., Bruns D.E., Gatsonis C.A., Glasziou P.P., Irwig L., et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ. 2015;351 doi: 10.1136/BMJ.H5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harbord R.M., Whiting P. metandi: Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracyusing hierarchical logistic regression. Stata J. 2009;9:211–229. doi: 10.1177/1536867×0900900203. 〈Https://DoiOrg/101177/1536867×0900900203〉 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nyaga V.N., Arbyn M. Metadta: a Stata command for meta-analysis and meta-regression of diagnostic test accuracy data – a tutorial. Arch Public Health. 2022;80:1–15. doi: 10.1186/S13690-021-00747-5/FIGURES/5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reitsma J.B., Glas A.S., Rutjes A.W.S., Scholten R.J.P.M., Bossuyt P.M., Zwinderman A.H. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:982–990. doi: 10.1016/J.JCLINEPI.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutter C.M., Gatsonis C.A. A hierarchical regression approach to meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy evaluations. Stat Med. 2001;20:2865–2884. doi: 10.1002/SIM.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bossuyt P.M.M., Davenport C.F., Deeks J.J., Hyde C., Leeflang M.M.G., Scholten R.J.P.M. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy Version 0.9. Chapter 11: Interpreting results and drawing conclusions. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2013.

- 19.Baydar O., Rozylo-Kalinowska I., Futyma-Gabka K., Saglam H. The U-net approaches to evaluation of dental bite-wing radiographs: an artificial intelligence study. Diagnostics. 2023;13 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics13030453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayraktar Y., Ayan E. Diagnosis of interproximal caries lesions with deep convolutional neural network in digital bitewing radiographs. Clin Oral Invest. 2022;26(1):623–632. doi: 10.1007/s00784-021-04040-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bayrakdar I.S., Orhan K., Akarsu S., Celik O., Atasoy S., Pekince A., et al. Deep-learning approach for caries detection and segmentation on dental bitewing radiographs. Oral Radio. 2022;38:468–479. doi: 10.1007/s11282-021-00577-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantu A.G., Gehrung S., Krois J., Chaurasia A., Rossi J.G., Gaudin R., et al. Detecting caries lesions of different radiographic extension on bitewings using deep learning. J Dent. 2020;100 doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2020.103425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X., Guo J., Ye J., Zhang M., Liang Y. Detection of proximal caries lesions on bitewing radiographs using deep learning method. Caries Res. 2022;56:455–463. doi: 10.1159/000527418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Estai M., Tennant M., Gebauer D., Brostek A., Vignarajan J., Mehdizadeh M., et al. Evaluation of a deep learning system for automatic detection of proximal surface dental caries on bitewing radiographs. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2022;134:262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2022.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee S., Oh S.I., Jo J., Kang S., Shin Y., Park J.W. Deep learning for early dental caries detection in bitewing radiographs. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-96368-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mao Y.C., Chen T.Y., Chou H.S., Lin S.Y., Liu S.Y., Chen Y.A., et al. Caries and restoration detection using bitewing film based on transfer learning with CNNs. Sensors. 2021;21:4613. doi: 10.3390/s21134613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moran M., Faria M., Giraldi G., Bastos L., Oliveira L., Conci A. Classification of approximal caries in bitewing radiographs using convolutional neural networks. Sensors. 2021;21:5192. doi: 10.3390/s21155192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panyarak W., Wantanajittikul K., Charuakkra A., Prapayasatok S., Suttapak W. Enhancing caries detection in bitewing radiographs using YOLOv7. J Digit Imaging. 2023:1–13. doi: 10.1007/S10278-023-00871-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suttapak W., Panyarak W., Jira-apiwattana D., Wantanajittikul K. A unified convolution neural network for dental caries classification. ECTI-CIT Trans. 2022;16:186–195. doi: 10.37936/ecti-cit.2022162.245901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panyarak W., Wantanajittikul K., Suttapak W., Charuakkra A., Prapayasatok S. Feasibility of deep learning for dental caries classification in bitewing radiographs based on the ICCMS radiographic scoring system. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2023;135:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2022.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panyarak W., Suttapak W., Wantanajittikul K., Charuakkra A., Prapayasatok S. Assessment of YOLOv3 for caries detection in bitewing radiographs based on the ICCMSTM radiographic scoring system. Clin Oral Invest. 2022;27:1731–1742. doi: 10.1007/s00784-022-04801-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed W.M., Azhari A.A., Fawaz K.A., Ahmed H.M., Alsadah Z.M., Majumdar A., et al. Artificial intelligence in the detection and classification of dental caries. J Prosthet Dent. 2023;26 doi: 10.1016/J.PROSDENT.2023.07.013. 00478–0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foros P., Oikonomou E., Koletsi D., Rahiotis C., Rahiotis C. Detection methods for early caries diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2021;55:247–259. doi: 10.1159/000516084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neuhaus K.W., Eggmann F., Kühnisch J., Kapor S., Janjic Rankovic M., Schüler I., et al. Standard reporting of caries detection and diagnostic studies (STARCARDDS) Clin Oral Invest. 2022;26:1947. doi: 10.1007/S00784-021-04173-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kühnisch J., Janjic Rankovic M., Kapor S., Schüler I., Krause F., Michou S., et al. Identifying and avoiding risk of bias in caries diagnostic studies. J Clin Med. 2021;10:3223. doi: 10.3390/JCM10153223/S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwendicke F., Tzschoppe M., Paris S. Radiographic caries detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2015;43:924–933. doi: 10.1016/J.JDENT.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khanagar S.B., Alfouzan K., Awawdeh M., Alkadi L., Albalawi F., Alfadley A. Application and performance of artificial intelligence technology in detection, diagnosis and prediction of dental caries (DC)—a systematic review. Diagnostics. 2022;12:1083. doi: 10.3390/DIAGNOSTICS12051083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forouzeshfar P., Safaei A.A., Ghaderi F., Hashemi Kamangar S.S., Kaviani H., Haghi S. Dental caries diagnosis using neural networks and deep learning: a systematic review. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023:1–44. doi: 10.1007/S11042-023-16599-W/FIGURES/17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prados-Privado M., Villalón J.G., Martínez-Martínez C.H., Ivorra C., Prados-Frutos J.C. Dental caries diagnosis and detection using neural networks: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2020;9:3579. doi: 10.3390/JCM9113579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material