Abstract

Purpose of Review

Massive irreparable rotator cuff tears (MIRCTs) present treatment challenges. Recently, superior capsule reconstruction (SCR) and anterior cable reconstruction have emerged as surgical options, but no single approach is superior. This review provides an overview of SCR and cable reconstruction techniques, including biomechanical studies, clinical outcomes, and surgical considerations.

Recent Findings

Biomechanical studies show SCR with autografts or allografts improves glenohumeral stability and mechanics. Clinical outcomes of SCR demonstrate improved range of motion, function scores, and pain relief in short-term studies. Anterior cable reconstruction reduces superior humeral head translation and subacromial pressures in biomechanical models. Early clinical studies report improved rotator cuff healing and outcomes for cable reconstruction in specific irreparable tear patterns.

Summary

SCR and cable reconstruction are viable surgical options for MIRCTs based on early encouraging results. However, higher-level comparative studies with long-term follow-up are still needed. Careful consideration of tear pattern, patient factors, and surgical goals is required to optimize treatment of MIRCTs. Further research is necessary to determine the optimal role for these procedures.

Keywords: Massive irreparable rotator cuff tears; Superior capsule reconstruction, Cable reconstruction, Biomechanics, Clinical outcomes

Introduction

Massive irreparable rotator cuff tears (MIRCTs) present significant challenges, leading to intense shoulder pain and functional impairment [1, 2•, 3]. MIRCTs are defined as tears larger than 5 cm or involving two or more tendons that are unable to be repaired primarily. There are several treatment options for MIRCTs, including non-operative management, debridement, partial repair, tendon transfers, reverse total shoulder arthroplasty, and recently introduced techniques like superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) and anterior cable reconstruction. However, no single approach has been established as superior [1, 2•, 3].

SCR addresses MIRCTs by reconstructing the superior capsule using autograft or allograft tissue attached medially to the glenoid and laterally to the greater tuberosity [4–6]. This procedure aims to restore superior stability to the glenohumeral joint, re-center the humeral head and enhance the remaining rotator cuff muscles’ function. Initial outcomes of SCR demonstrate improved range of motion, function scores, and pain relief [7]. Nevertheless, long-term durability and comparative studies with other procedures require further investigation [8].

The rotator cable complex plays a crucial role in maintaining balanced force couples for the rotator cuff's optimal function [9–12]. Both the anterior and posterior rotator cable attachments are particularly important for overhead movements [12]. Thus, an alternative approach to addressing MIRCTs may involve focusing on these critical attachment sites instead of covering the entire superior capsule, as seen SCR. Cable reconstruction aims to restore the rotator cable using autograft or allograft tissue, providing static anterior and posterior stability while avoiding extensive dissection and graft passage into the subacromial space, which is necessary for SCR [13, 14••]. Though long-term data is still limited, cable reconstruction may serve as a joint-preserving option for specific patients with irreparable tears isolated to the anterior or posterior cable.

The aim of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of SCR and anterior cable reconstruction as treatment options for MIRCTs, while presenting the existing biomechanical and clinical data, as well as insights into authors’ surgical technique preferences.

Superior Capsule Reconstruction

Background/Rationale

The rationale behind SCR is to restore glenohumeral kinematics by recreating the biomechanical advantage provided by the superior shoulder capsule and provide a scaffold for balancing rotator cuff force couples. The superior shoulder capsule runs on the undersurface of the rotator cuff tendons and extends between the superior glenoid and greater tuberosity [15]. It is well-recognized as a main static stabilizer of the glenohumeral joint, particularly in terms of limiting superior translation of the humerus [16, 17].

Biomechanical Outcomes

In 2012, Mihata et al. performed the first biomechanical study of SCR in a cadaveric model [15]. They noted significant changes including increased humeral translation, increased subacromial contact pressure, and decreased glenohumeral compression in a supraspinatus tear model. The authors then compared the biomechanical changes in these factors after using a patch to reconstruct the supraspinatus, to reconstruct the superior capsule, and to reconstruct both the supraspinatus and superior capsule. Their main finding was that superior translation was completely restored in the SCR group, but only partially restored in the rotator cuff repair group. Further, SCR improved the range of motion stability while no improvement was noted in the rotator cuff patch group.

Subsequent biomechanical studies have built on Mihata’s early work and have also focused on optimizing SCR technique and graft choice. Specifically, graft choice between fascia lata and human dermal allograft has been considered in several studies. In a cadaveric biomechanical analysis, human dermal allograft was found to only partially restore superior glenohumeral stability, which was fully restored in a fascia lata allograft group [18]. This and other studies were included in a 2023 systematic review that noted improved restraint to superior translation in the fascia lata group when compared to human dermal and long head of the biceps tendon cohorts [19]. However, it has been demonstrated that doubling the dermal allograft can result in similar biomechanics to the fascia lata allograft, leading authors to advocate for doubling the dermal graft to result in an increased thickness and biomechanical stability [20].

Several studies have also investigated the effects of different graft thicknesses. Mihata’s original biomechanical work demonstrated the benefits of SCR with a 5-mm-thick fascial graft [15]. Clinically, however, favorable results have been noted with graft thicknesses ranging between 3.5 mm [21] and 8 mm [22]. In 2016, Mihata et al. directly compared subacromial contract pressures and superior translation with grafts of 4 mm and 8 mm thicknesses in a cadaveric model [23]. In this series, although both grafts decreased subacromial contact pressure, the 8-mm-thick graft demonstrated improved superior stability. Further, a 2021 article by Lacheta et al. found that a 3-mm-thick dermal allograft only partially restored superior stability of the glenohumeral joint, which authors note may have clinical consequences [24]. Other biomechanical studies have also shown that acromioplasty significantly decreases the subacromial contact area compared with SCR without acromioplasty [25].

Several studies have evaluated using the long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) as an autograft option for SCR. Potential advantages of using the native biceps include avoiding donor site morbidity and utilizing a locally available tissue. Denard et al. [26] tested a box-shaped SCR configuration using the LHBT in 8 cadaveric shoulders. The biceps origin was left intact and the tendon secured anterolaterally and posteromedially with suture anchors to create a box configuration. Compared to a massive cuff tear model, the box SCR decreased superior translation by about 2 mm at 0 degrees abduction. Peak subacromial pressures were also reduced with the box SCR compared to the cuff tear model. The authors concluded the box SCR may play a role in augmentation of massive tears. El-Shaar et al. [27] compared SCR using either LHBT or tensor fascia lata (TFL) autografts in 10 cadaveric shoulders. The LHBT graft required 393% more force for superior translation compared to the cuff tear state, while the TFL required 194% more force. The LHBT graft trended toward being a stronger reconstruction compared to the TFL. This suggests the LHBT may be equivalent or potentially even better than the TFL graft.

Clinical Outcomes

Fascia Lata Autograft

Mihata et al. first reported on the clinical outcomes of fascia lata autograft SCR in 2013 [22]. This original series included 24 shoulders with irreparable rotator cuff tears treated with SCR. Encouraging results were noted including an average gain of active elevation of 64°, acromiohumeral distance increase of 4.1 mm, and no progression of osteoarthritis at a mean of 34 months of follow-up. Importantly, this series also demonstrated an impressive improvement in the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score, from 24 preoperatively to 93 after SCR.

In 2018, Mihata et al. reported on the outcomes of SCR in patients with pseudoparalysis [28]. In this series of 88 patients, they noted improvements in active forward elevation, external rotation, acromiohumeral distance, and patient-reported outcome scores in all patients. Further, in 28 patients identified to have pseudoparalysis, active forward elevation improved from 37° to 150°, and 27 were noted to have reversal of their pseudoparalysis. Mihata and colleagues have also provided insight into potential high return to sport after SCR [29]. One potential downside to the fascia lata autograft is harvest site morbidity; however, some argue that this is a clinically non-significant issue that can be further mitigated with minimally invasive harvesting techniques [30, 31].

Long Head of the Biceps Tendon

Several recent studies have evaluated the outcomes of SCR using the LHBT for treatment of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Overall, studies have shown significant improvements in pain scores, shoulder function, and range of motion with the use of the LHBT for SCR. Systematic reviews have reported the mean visual analog scale (VAS) exceeding the minimal clinically important difference for adequate pain relief [32–34]. Shoulder functional outcome scores such as the Constant score, ASES score, Simple Shoulder Test (SST), and others have also shown significant improvements after SCR with the biceps tendon [32, 33, 34]. Range of motion has also improved, with reported improvements in forward elevation and in external rotation. Comparison studies have shown SCR with the biceps tendon has equivalent improvements in pain, function, and range of motion compared to traditional SCR with fascia lata graft and other rotator cuff repair techniques for massive tears [35]. Advantages of using the biceps tendon include less surgical time, no graft cost, avoidance of donor site morbidity, and a technically simpler procedure.

Human Dermal Allograft

Positive results have also been demonstrated in clinical studies evaluating the outcomes of SCR utilizing a human dermal allograft. In 2017, Denard et al. reported their preliminary results with the dermal allograft in SCR [36]. Although they noted a revision rate of 18%, improvements in pain and acromiohumeral distance allowed the authors to conclude that these early results were encouraging. Pennington et al. also reported on a consecutive series of 88 patients undergoing SCR with dermal allograft, in which they found significant improvements in pain, function, and radiographic parameters [37]. These authors also noted that the lasting increase in acromiohumeral distance may indicate the reliability of this graft option in maintaining capsular stability. In 2019, Burkhart and Hartzler built on this work and evaluated the outcomes in 10 pseudoparalytic patients managed with dermal allograft SCR. In this cohort, they reported an average forward elevation gain of 132° in addition to significant improvement in pain and AES scores [38]. Although concerns exist regarding the smaller thickness of the dermal allograft as compared to the fascia lata autograft, a systematic review evaluating 606 shoulders demonstrated favorable short and mid-term results in both graft options [39].

Author’s Approach

Indications

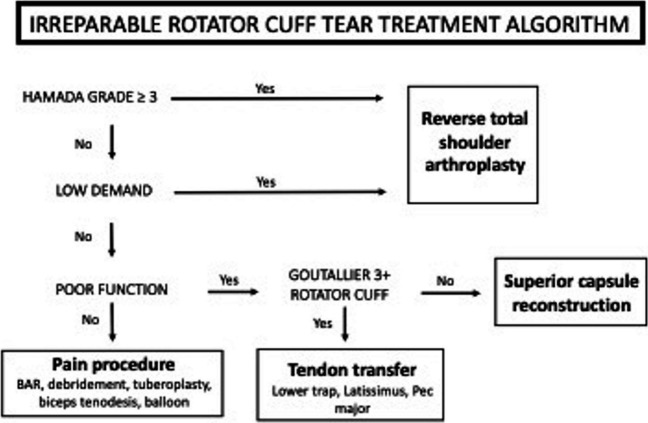

The author’s preferred treatment algorithm is outlined in Fig. 1. In the absence of advanced degenerative changes and in higher demand patients, function should next be considered. Patients with compromised function are unlikely to have a satisfactory outcome with procedures that only address pain. The condition of the rotator cuff should be examined next, as significant fatty infiltration would make the patient a reasonable candidate for tendon transfer procedures such as the latissimus dorsi or lower trapezius transfer. Lastly, if condition of the rotator cuff is intact, the patient is likely a candidate for SCR with partial rotator cuff repair. In this case, the superior stability of the shoulder is restored with the SCR, while partial rotator cuff repair of viable affords optimization of strength, function, and dynamic stability.

Fig. 1.

Treatment algorithm for patients with MIRCT undergoing SCR

Technique

It is the authors’ preferred technique to utilize either a human dermal, Achilles, or fascia lata graft based on patient factors. If the patient demonstrates pseudoparalysis or severe loss of function, Achilles or fascia lata is utilized. However, in the case of maintained shoulder function, human dermal allograft is the graft of choice. In these cases, the excess dermal allograft is used as a spacer for the undersurface of the acromion [40]. Thereby, the thickness of the graft is essentially doubled in addition to providing a buffer for painful impingement.

After general anesthesia is obtained, the patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with a beanbag. It is the authors’ preference to use a padded arm sleeve (STAR; Arthrex, Naples, FL) in lateral suspension. A standard posterior portal is created approximately 1 cm medial and 2 cm distal to the posterolateral border of the acromion. The anterior portal is then created just lateral to the coracoid. Following, diagnostic arthroscopy is performed to fully evaluate and address any intra-articular pathology. Subacromial access is then established with creation of posterolateral and anterolateral portals. A Nevasier portal is also made in order to assist future anchor placement and graft passage. Attempts are then made to mobilize the rotator cuff with capsular, subacromial, and anterior rotator interval releases. If these result in adequate mobility of the rotator cuff, primary repair is attempted. Otherwise, the remaining rotator cuff is mobilized as much as possible to afford for later incorporation with the SCR.

Attention is then turned to preparing the glenoid neck. The glenoid neck just medial to the superior labrum is biologically prepared with a shaver, ablator, or rasp to create a vascular bed. This debrided region should span from the rotator interval anteriorly to the posterior cuff remnant posteriorly. The location of the glenoid anchors are then planned. Typically, 3 knotless anchors (1.8-mm Fibertak; Arthrex, Naples, FL) anchors are utilized and placed at various landmarks. The anterior anchor is typically placed at the anterior base of the coracoid even with the top of the subscapularis. The middle anchor is placed at the posterior aspect of the coracoid, and the posterior anchor is placed at the level of the remnant rotator cuff. The size of the rotator cuff defect is then measured using an arthroscopic probe (Arthrex). The anteroposterior and mediolateral dimensions are recorded and used to prepare the dermal graft, which is prepped and trimmed on the back table. A marking pen is used to note the location of sutures. The marks medially would be 5 mm medial to the edge of the patch, but the patch should be cut so that there is 5 mm on each side anterior and posterior to the mark as well.

The graft is then brought to the shoulder near the anterolateral portal. All 3 working stitches are passed out the lateral portal with special attention paid not to twist the suture. The graft is then rolled and passed while slack is taken out of the knotless anchor devices. Once adequate tension is achieved, the excess suture can be cut and retrieved. Attention is then turned to fixing the graft laterally, which can be achieved in single-row or double-row fashion with the arm in 45° of abduction. Importantly, the authors always attach the remnant of the rotator cuff to the patch just beyond the glenoid fixation. The preferred technique is described by Tokish et al. [41••] and utilizes two free #2 Fiberwire that are passed through the graft at its midportion along the anterior and posterior halves in a horizontal mattress fashion prior to passing the graft. After the graft is secured, these horizontal mattress sutures can be retrieved out the lateral portal before being passed through the remnant superior rotator cuff. A #2 Fiberwire can then be passed through the posterior midportion of the graft and attached to the remnant teres minor tendon. Anteriorly, the sutures can be placed in the superolateral aspect of the subscapularis tendon, or if not available, to the anterolateral humeral head with a knotless anchor.

As noted, it is the authors’ preference to place the excess dermal allograft on the undersurface of the acromion. The preferred technique to for this acromial allograft spacer technique is as reported by Makovicka et al. [40] in 2018. Postoperatively, the patient is placed in a shoulder immobilizer with an abduction pillow. Elbow, wrist, hand, and gentle passive glenohumeral motion is permitted for the first 6 weeks postoperatively. Progressive motion is then begun at 6 weeks, with formal strengthening initiated at 12 weeks. Gradual return to activity is allowed over a 6-month period as the patient progresses.

Rotator Cable Reconstruction

Background/Rationale

The concept of the rotator cable was originally introduced by Burkhart et al. [42]. According to their findings, the rotator cable complex represents a thickening of the rotator cuff tendons in the transverse plane, spanning from the anterior supraspinatus to the posterior infraspinatus. This unique anatomical structure was termed the “suspension bridge” as it plays a crucial role in maintaining connectivity between the rotator cuff muscles, enabling coordinated function and optimized force transmission [9–12]. When the rotator cable attachments are disrupted due to cuff tearing, it can result in imbalanced force couples and unopposed superior humeral migration [12]. As the anterior and posterior cable attachments are particularly crucial for overhead shoulder function, the restoration of these sites is of utmost importance [12]. Rotator cable reconstruction aims to restore the cable anatomy using graft augmentation in cases where direct tendon-bone healing is not feasible. By re-establishing the cable attachments at the anterior and posterior humeral tuberosity, this procedure leads to improved superior stability, restoration of native shoulder mechanics, and the regaining of proper function.

Biomechanical Outcomes

Denard et al. [43] tested a V-shaped semitendinosus allograft (VST) anterior cable reconstruction in a biomechanical model simulating a complete supraspinatus tear and partial infraspinatus tear involving the anterior half, representing anterior cable disruption. They found that the VST significantly decreased superior translation of the humeral head compared to the massive tear model at 0° and 20° of glenohumeral abduction. Additionally, the VST restored peak subacromial contact pressures to intact, pre-tear levels at all positions except 40° abduction and 60° external rotation. Glenohumeral kinematics were not affected by the VST compared to the intact state. The authors concluded that the VST may help restore anterior stability and reduce subacromial pressures for irreparable tears with isolated deficiency of the anterior rotator cable. Park et al. [44] evaluated an anterior cable reconstruction using semitendinosus allograft in a supraspinatus plus half infraspinatus tear model representing massive irreparable tears. They found the allograft anterior cable reconstruction significantly decreased superior translation of the humeral head compared to the tear model from 0 to 60° of external rotation at both 0° and 20° of glenohumeral abduction. Additionally, the reconstruction significantly reduced peak and mean subacromial contact pressures. Compared to the intact state, the allograft anterior cable reconstruction showed higher total rotational range of motion. The authors concluded this technique using an allograft tendon can reduce superior humeral head migration and subacromial pressures without restricting natural glenohumeral range of motion.

Park et al. [45] tested an anterior cable reconstruction using the proximal biceps tendon in both a complete supraspinatus tear model and a combined supraspinatus plus half infraspinatus tear model representing massive irreparable tears. For both tear models, the biceps tendon anterior cable reconstruction was able to significantly decrease superior translation compared to the tear states from 0 to 60° of external rotation at 0° and 20° of glenohumeral abduction. Additionally, for the combined supraspinatus and infraspinatus tear model, the biceps tendon reconstruction reduced peak subacromial contact pressures compared to the tear state. As with the allograft reconstruction, the biceps tendon technique also showed increased total range of motion compared to intact. The authors concluded that using the native biceps tendon can reduce superior humeral head migration and contact pressures without limiting natural glenohumeral range of motion.

Clinical Outcomes

Anterior cable reconstruction using the proximal biceps tendon has recently emerged as a technique to improve rotator cuff healing and outcomes in patients with large retracted tears involving anterior cable disruption. In the study by Seo et al. [46], anterior cable reconstruction using the long head of the biceps was performed in 41 patients with large to massive rotator cuff tears. At 18.7-month follow-up, the retear rate was lower in the anterior cable reconstruction group at 4.9% compared to 7.1% with conventional repair alone. The postoperative acromiohumeral distance increased significantly in both groups (p < 0.0001) but was larger in the anterior cable reconstruction group at 9.2 ± 1.9 mm vs 8.1 ± 2.4 mm in the conventional repair group (p = 0.01). There were no significant differences in postoperative visual analog scale pain scores, ASES scores, or range of motion between the two groups. In a study by Yang et al. [47], anterior cable reconstruction using the biceps tendon was performed in 32 patients with large retracted anterior L-shaped tears. At a mean 25.4-month follow-up, the retear rate was 18.7%. The ASES score significantly improved from 66.6 preoperatively to 94.1 postoperatively (p < 0.001). The VAS pain score decreased from 2.8 to 0.5 (p < 0.001). In the 6 patients with retears, the relative tear size decreased by 56.8% anteroposteriorly and 70.6% mediolaterally compared to the primary tear size. Their ASES scores still significantly improved from 72.8 preoperatively to 91.1 postoperatively (p < 0.001).

Author’s Approach

Indications

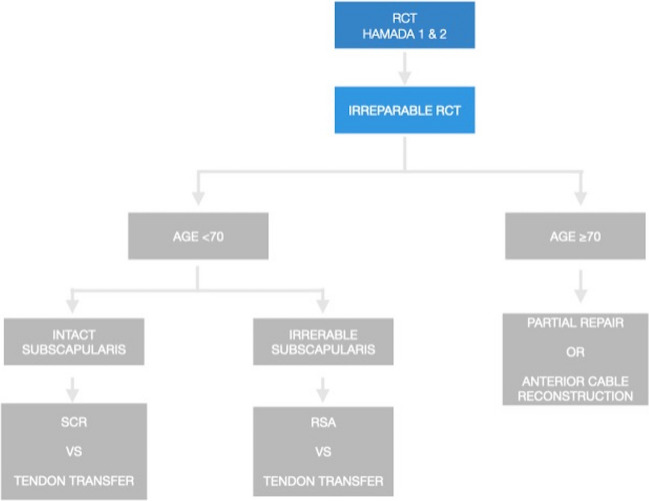

The ideal candidates for cable reconstruction are active adults over the age of 70 with massive, irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears involving both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons. The tear pattern should demonstrate disrupted anterior and posterior rotator cable attachments on diagnostic imaging and arthroscopic evaluation. Patients should exhibit well-preserved glenohumeral joint cartilage without significant arthritis based on radiographs. This technique is best reserved for low-demand patients who wish to avoid reverse total shoulder arthroplasty and extensive postoperative rehabilitation. Adequate bone quality to allow secure suture anchor fixation is necessary. Conversely, this procedure has several contraindications, including young active patients where continued tear propagation is a major concern. Poor bone quality unable to provide adequate suture anchor purchase, significant pre-existing glenohumeral arthritis, and prior failed rotator cuff repairs. Careful patient selection is critical for achieving successful outcomes with suture-based cable reconstruction. The author’s preferred treatment algorithm is outlined in Fig. 2. It is the author’s preferred technique to utilize a semitendinosus allograft for cable reconstruction [14••].

Fig. 2.

Treatment algorithm for patients with MIRCT undergoing cable reconstruction

Technique

The patient is in the lateral decubitus position with the arm suspended in traction. Diagnostic arthroscopy is performed through a standard posterior portal. The integrity of the subscapularis tendon is assessed and repaired if necessary. The long head of the biceps tendon is preserved if intact. The arthroscope is moved to the subacromial space. A lateral working portal is created. A complete bursectomy and removal of bursal adhesions are performed to allow full visualization of the rotator cuff tear pattern and mobility assessment.

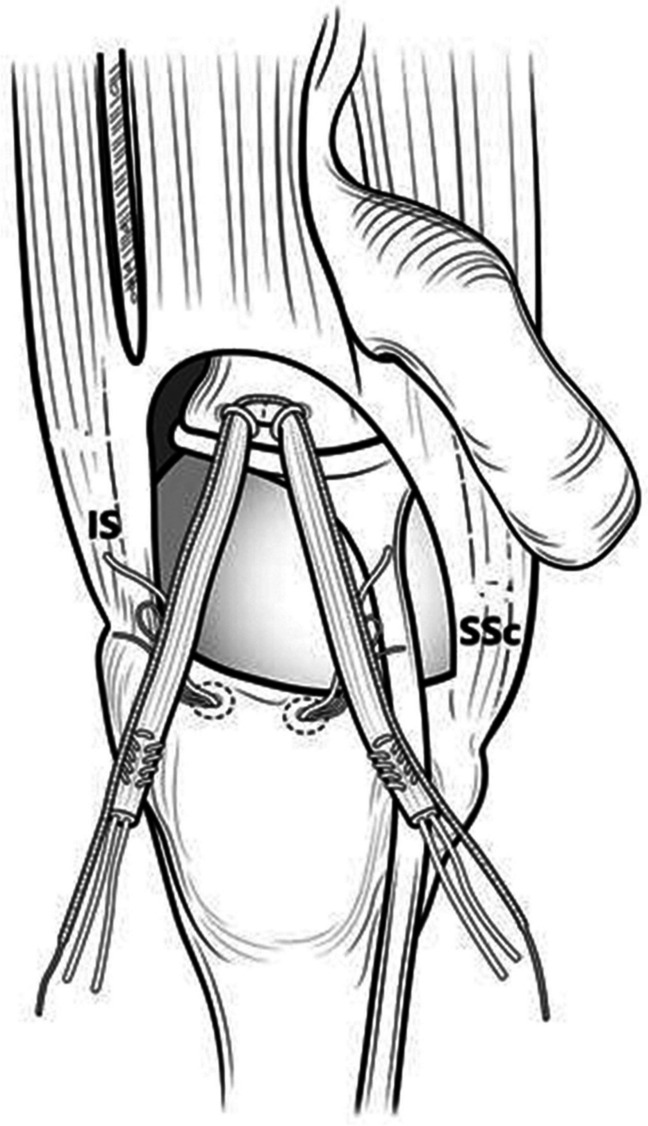

If the tear is massive and irreparable, involving both the supra- and infraspinatus tendons, semitendinosus allograft cable reconstruction is planned. Care is taken to preserve the superior labrum while preparing the glenoid. A superior portal is created, and a 2.6-mm knotless tensionable anchor (FiberTak; Arthrex) is drilled into the glenoid approximately 5 mm medial to the native biceps anchor. This anchor has a fixed repair suture and sliding shuttling suture. The repair suture is used to measure the distance from the glenoid to the lateral edge of the greater tuberosity at both the anterior and posterior aspects. These distances determine graft length. Typically 5 mm is added to the overall length to allow for graft folding at the glenoid anchor. The semitendinosus allograft is prepared on the back table. The graft length is marked at the midpoint. The ends are whipstitched for 10–15 mm with sutures exiting the graft. The prepared graft is pre-tensioned. In the subacromial space, two 2.6-mm knotless anchors (FiberTak; Arthrex) are placed into the greater tuberosity just medial to the articular margin via percutaneous portals. Proper trajectory is critical. The repair suture and shuttling suture from the glenoid anchor are retrieved out the lateral working cannula. The midpoint of the graft is passed through the shuttling suture loop. Tensioning the knotless mechanism secures the graft to the glenoid (Fig. 3). Before lateral fixation, the medial anchor repair sutures are passed to the opposite side of the graft. The posterior graft limb is fixed first just lateral to the greater tuberosity using a 5.5-mm knotless anchor (SwiveLock; Arthrex). The anterior limb is then fixed via the anterolateral portal completing the lateral fixation. The medial anchor repair sutures are tied sequentially to compress the graft to the tuberosity. If possible, margin convergence sutures are used to advance the posterior cuff to the graft (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Schematic view of the V-shaped graft secured to the glenoid with 2 knotless anchors. IS, infraspinatus; SSc, subscapularis

Fig. 4.

Schematic view of final cable allograft constructs viewed from topdown (A) and oblique (B) views. IS, infraspinatus; SSc, subscapularis

Postoperatively, patients are placed in a sling for 6 weeks after surgery with only elbow, wrist, and hand motion permitted. At 6 weeks, the sling is discontinued, and passive shoulder range of motion is initiated. At 12 weeks, strengthening begins. After 6 months, a gradual return to full activities is allowed but higher demand lifting, or overhead activities may be restricted up to 12 months.

Conclusion

MIRCTs remain a challenging scenario for orthopedic surgeons. Many surgical techniques have been described to try to address these difficult tears, but no single approach has proven clearly superior. SCR using either autografts or allografts has shown encouraging improvements in range of motion, function scores, and pain relief in short- and mid-term studies. While long-term durability remains unknown, SCR holds promise as an effective treatment for MIRCTs in appropriate patients. Anterior cable reconstruction techniques using autograft or allograft sources have also recently emerged as options to restore glenohumeral stability by reconstructing the critical anterior and posterior rotator cable attachments. Early biomechanical and limited clinical studies demonstrate encouraging results. Though clinical outcomes are still forthcoming, cable reconstruction may improve rotator cuff healing and outcomes for specific irreparable tear patterns. Therefore, while SCR and cable reconstruction techniques seem to be viable surgical options for MIRCTs based on early results, higher-level comparative studies with long-term follow-up are still needed to better define their roles and optimize patient selection. Careful consideration of tear pattern, patient factors, and surgical goals must guide treatment of these complex cases.

Author Contribution

IP: initial writing, prepared figures and critical revisionsJB: initial writing and critical revisionsJT: Supervision, writing and critical draft revisions, conceptualizationPD: Supervision, writing and critical draft revisions, conceptualization

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Denard has the following conflicts of interest: American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons; board or committee member of Arthrex, Inc.; IP royalties; paid consultant; paid presenter or speaker; research support of Arthroscopy Association of North America; board or committee member of Kaliber Labs; Orthopedics Today; editorial or governing board of PT Genie; and Stock or stock Options. Dr. Tokish has the following conflicts of interest: Arthrex, Inc.; IP royalties; paid consultant; paid presenter or speaker of Arthroscopy Association of North America; board or committee member of Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery; editorial or governing board; publishing royalties and financial or material support of Orthopedics Today; and editorial or governing board.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Kovacevic D, Suriani RJ, Jr, Grawe BM, Yian EH, Gilotra MN, Hasan SA, et al. Management of irreparable massive rotator cuff tears: a systematic review and meta-analysis of patient-reported outcomes, reoperation rates, and treatment response. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29:2459–2475. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dey Hazra ME, Dey Hazra R-O, Hanson JA, Ganokroj P, Vopat ML, Rutledge JC, et al. Treatment options for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears: a review of arthroscopic surgical options. EFORT Open Rev. 2023;8:35–44. doi: 10.1530/EOR-22-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kucirek NK, Hung NJ, Wong SE. Treatment options for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2021;14:304–315. doi: 10.1007/s12178-021-09714-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burkhart SS, Denard PJ, Adams CR, Brady PC, Hartzler RU. Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction for massive irreparable rotator cuff repair. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5:e1407–e1418. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tokish JM, Makovicka JL. The Superior capsular reconstruction: lessons learned and future directions. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28:528–537. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noyes MP, Haidamous G, Spittle NE, Hartzler RU, Denard PJ. Surgical management of massive irreparable cuff tears: superior capsular reconstruction. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2020;13:717–724. doi: 10.1007/s12178-020-09669-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Ding W, Xu J, Ruan D, Heng BC, Ding Q, et al. Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears results in significant improvements in patient reported outcomes and range of motion: a systematic review. ASMAR. 2022;4:e1523–e1537. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2022.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werthel J-D, Vigan M, Schoch B, Francophone Arthroscopy Society (SFA), Lädermann A, Nourissat G, et al. Superior capsular reconstruction - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2021;107(8S):103072. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Goetti P, Denard PJ, Collin P, Ibrahim M, Hoffmeyer P, Lädermann A. Shoulder biomechanics in normal and selected pathological conditions. EFORT Open Rev. 2020;5:508–518. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.5.200006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huri G, Kaymakoglu M, Garbis N. Rotator cable and rotator interval: anatomy, biomechanics and clinical importance. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4:56–62. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.170071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arai R, Matsuda S. Macroscopic and microscopic anatomy of the rotator cable in the shoulder. J Orthop Sci. 2020;25:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jos.2019.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denard PJ, Koo SS, Murena L, Burkhart SS. Pseudoparalysis: the importance of rotator cable integrity. Orthopedics. 2012;35:e1353–e1357. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120822-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams CR, Pasqualini I, Heidenthal JM, Brady PC, Denard PJ. A technique for a suture-based cable reconstruction of an irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tear. Arthrosc Tech. 2022;11:e2055–e2060. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2022.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callegari JJ, Phillips CJ, Lee TQ, Kruse K, Denard PJ. Semitendinosus allograft cable reconstruction technique for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthrosc Tech. 2022;11:e153–e161. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2021.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2248–2255. doi: 10.1177/0363546512456195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishihara Y, Mihata T, Tamboli M, Nguyen L, Park KJ, McGarry MH, et al. Role of the superior shoulder capsule in passive stability of the glenohumeral joint. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:642–648. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciampi P, Scotti C, Nonis A, Vitali M, Di Serio C, Peretti GM, et al. The benefit of synthetic versus biological patch augmentation in the repair of posterosuperior massive rotator cuff tears: a 3-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:1169–1175. doi: 10.1177/0363546514525592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mihata T, Bui CNH, Akeda M, Cavagnaro MA, Kuenzler M, Peterson AB, et al. A biomechanical cadaveric study comparing superior capsule reconstruction using fascia lata allograft with human dermal allograft for irreparable rotator cuff tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:2158–2166. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao X, Jia J, Wen L, Zhang B. Biomechanical outcomes of superior capsular reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears by different graft materials-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Surg. 2022;9:939096. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2022.939096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.E Cline K, Tibone JE, Ihn H, Akeda M, Kim BS, McGarry MH, et al. Superior capsule reconstruction using fascia lata allograft compared with double- and single-layer dermal allograft: a biomechanical study. Arthroscopy. 2021;37(4):1117–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Sutter EG, Godin JA, Garrigues GE. All-arthroscopic superior shoulder capsule reconstruction with partial rotator cuff repair. Orthopedics. 2017;40:e735–e738. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20170615-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, Fukunishi K, Ohue M, Tsujimura T, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:459–470. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mihata T, McGarry MH, Kahn T, Goldberg I, Neo M, Lee TQ. Biomechanical effect of thickness and tension of fascia lata graft on glenohumeral stability for superior capsule reconstruction in irreparable supraspinatus tears. Arthroscopy. 2016;32:418–426. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lacheta L, Brady A, Rosenberg SI, Dekker TJ, Kashyap R, Zandiyeh P, et al. Superior capsule reconstruction with a 3 mm-thick dermal allograft partially restores glenohumeral stability in massive posterosuperior rotator cuff deficiency: a dynamic robotic shoulder model. Am J Sports Med. 2021;49:2056–2063. doi: 10.1177/03635465211013364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mihata T, McGarry MH, Kahn T, Goldberg I, Neo M, Lee TQ. Biomechanical effects of acromioplasty on superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable supraspinatus tendon tears. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:191–197. doi: 10.1177/0363546515608652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denard PJ, Chae S, Chalmers C, Choi JH, McGarry MH, Adamson G, et al. Biceps box configuration for superior capsule reconstruction of the glenohumeral joint decreases superior translation but not to native levels in a biomechanical study. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2021;3:e343–e350. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2020.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Shaar R, Soin S, Nicandri G, Maloney M, Voloshin I. Superior capsular reconstruction with a long head of the biceps tendon autograft: a cadaveric study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6:2325967118785365. doi: 10.1177/2325967118785365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mihata T, Lee TQ, Hasegawa A, Kawakami T, Fukunishi K, Fujisawa Y, et al. Arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction can eliminate pseudoparalysis in patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:2707–2716. doi: 10.1177/0363546518786489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mihata T, Lee TQ, Fukunishi K, Itami Y, Fujisawa Y, Kawakami T, et al. Return to Sports and physical work after arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction among patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46:1077–1083. doi: 10.1177/0363546517753387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ângelo ACLPG, de Campos Azevedo CI. Donor-site morbidity after autologous fascia lata harvest for arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction: a midterm follow-up evaluation. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022;10(2):23259671211073133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Ângelo ACLPG, de Campos Azevedo CI. Minimally invasive fascia lata harvesting in ASCR does not produce significant donor site morbidity. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2019;27:245–50. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5085-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitridis D, Yiannakopoulos C, Sinopidis C, Givissis P, Galanis N. Superior capsular reconstruction of the shoulder using the long head of the biceps tendon: a systematic review of surgical techniques and clinical outcomes. Medicina. 2021;57:229. doi: 10.3390/medicina57030229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheppalli NS, Purudappa PP, Metikala S, Reddy KI, Singla A, Patel HA, et al. Superior capsular reconstruction using the biceps tendon in the treatment of irreparable massive rotator cuff tears improves patient-reported outcome scores: a systematic review. ASMAR. 2022;4:e1235–e1243. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2022.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheppalli NS, Purudappa PP, Metikala S, Goel A, Singla A, Sambandam S. Using biceps tendon autograft as a patch in the treatment of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears improves patient-reported outcome scores: a systematic review. ASMAR. 2023;5:e529–e536. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2023.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kocaoglu B, Firatli G, Ulku TK. Partial rotator cuff repair with superior capsular reconstruction using the biceps tendon is as effective as superior capsular reconstruction using a tensor fasciae latae autograft in the treatment of irreparable massive rotator cuff tears. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8:2325967120922526. doi: 10.1177/2325967120922526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Denard PJ, Brady PC, Adams CR, Tokish JM, Burkhart SS. Preliminary results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction with dermal allograft. Arthroscopy. 2018;34:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.08.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pennington WT, Bartz BA, Pauli JM, Walker CE, Schmidt W. Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction with acellular dermal allograft for the treatment of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears: short-term clinical outcomes and the radiographic parameter of superior capsular distance. Arthroscopy. 2018;34:1764–1773. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burkhart SS, Hartzler RU. Superior capsular reconstruction reverses profound pseudoparalysis in patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears and minimal or no glenohumeral arthritis. Arthroscopy. 2019;35:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith TJ, Gowd AK, Kunkel J, Kaplin L, Hubbard JB, Coates KE, et al. Clinical outcomes of superior capsular reconstruction for massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review comparing acellular dermal allograft and autograft fascia lata. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2021;3:e257–e268. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2020.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Makovicka JL, Patel KA, Tokish JM. Superior capsular reconstruction with the addition of an acromial acellular dermal allograft spacer. Arthrosc Tech. 2018;7:e1181–e1190. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tokish JM, Momaya A, Roberson T. Superior capsular reconstruction with a partial rotator cuff repair: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2018;8:e1. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.CC.17.00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burkhart SS, Esch JC, Jolson RS. The rotator crescent and rotator cable: an anatomic description of the shoulder’s “suspension bridge”. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:611–616. doi: 10.1016/S0749-8063(05)80496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Denard PJ, Park MC, McGarry MH, Adamson G, Lee TQ. Biomechanical assessment of a V-shaped semitendinosus allograft anterior cable reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2022;38:719–728. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2021.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park MC, Hung VT, DeGiacomo AF, McGarry MH, Adamson GJ, Lee TQ. Anterior Cable reconstruction of the superior capsule using semitendinosus allograft for large rotator cuff defects limits superior migration and subacromial contact without inhibiting range of motion: a biomechanical analysis. Arthroscopy. 2021;37:1400–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2020.12.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park MC, Itami Y, Lin CC, Kantor A, McGarry MH, Park CJ, et al. Anterior Cable reconstruction using the proximal biceps tendon for large rotator cuff defects limits superior migration and subacromial contact without inhibiting range of motion: a biomechanical analysis. Arthroscopy. 2018;34:2590–2600. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seo J-B, Kwak K-Y, Park B, Yoo J-S. Anterior cable reconstruction using the proximal biceps tendon for reinforcement of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair prevent retear and increase acromiohumeral distance. J Orthop. 2021;23:246–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang H, Lee S, Shin S-J. Satisfactory functional and structural outcomes of anterior cable reconstruction using the proximal biceps tendon for large retracted rotator cuff tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31:1910–1918. doi: 10.1007/s00167-022-07112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]