Abstract

Purpose of Review

Functionally irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears (FIRCT) represent a substantial source of morbidity for many patients. Several surgical options can be considered for the salvage of FICRTs. Transfer of the tendon of the lower trapezius to the greater tuberosity, originally described for surgical management of the paralytic shoulder, has emerged as an attractive option, particularly for patients with external rotation lag and those looking for strength restoration. The purpose of this publication is to review the indications, surgical technique, and reported outcomes of this procedure.

Recent Findings

Lower trapezius transfer (LTT) to the greater tuberosity in patients with irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears has been reported to be associated with satisfactory outcomes and low reoperation rates. It seems to be particularly effective in improving external rotation motion and strength, even when the teres minor is involved. In patients with a reparable infraspinatus, minimal fatty infiltration, and an intact teres minor, the outcome of LTT may be similar to that of superior capsule reconstruction (SCR), but LTT is more beneficial otherwise. The hospital cost of LTT has been reported to be less than the cost of SCR and equivalent to the cost of reverse arthroplasty. When reverse arthroplasty has been performed after a failed LTT, the outcome and complication rates do not seem to increase.

Summary

LTT provides satisfactory outcomes for many patients with a posterosuperior FIRCT, particularly when they present preoperatively with an external rotation lag sign, involvement of the teres minor, or a desire to improve strength.

Keywords: Rotator cuff tear, Tendon transfer, Lower trapezius transfer

Introduction

Rotator cuff tears are a common source of shoulder pain and disability [1]. When conservative management is not successful, rotator cuff repair is considered. However, not uncommonly, patients present with advanced rotator cuff tears not amenable to surgical repair, either because the size and retraction of the tear are such that they do not allow to physically anchor the torn tendons or because the chances of tendon-to-bone healing are very slim. The term functionally irreparable cuff tear (FIRCT) has been coined to encompass these two categories of patients, reflecting the fact that some tears will just not reach the anatomic footprint (irreparable) whereas others may reach but still will not heal (functionally irreparable) [2].

There are multiple salvage options described for the surgical management of FIRCT. Currently, the most popular options include superior capsular reconstruction (SCR), reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA), implantation of a subacromial balloon, and tendon transfers [3]. Table 1 summarizes the ideal indications for each of these procedures. Tendon transfers are ideal for individuals with an external rotation lag sign or severe weakness in external rotation, although tendon transfers can also be considered for other patients with posterosuperior FIRCT provided there is no glenohumeral arthritis or escape.

Table 1.

Ideal indications for salvage procedures in patients with posterosuperior FIRCT

| Subacromial balloon |

• Older age • Good active motion, no lag signs • Intact subscapularis • No glenohumeral arthritis |

| Superior capsule reconstruction |

• Intact teres minor • Intact or reparable subscapularis • No external rotation lag sign • No advanced infraspinatus atrophy • No glenohumeral arthritis |

| Tendon transfers |

• External rotation lag sign or severe weakness in external rotation • No glenohumeral arthritis |

| Reverse shoulder arthroplasty |

• Glenohumeral arthritis • True pseudoparalysis in elevation, especially with escape • Associated irreparable subscapularis • Failed SCR or failed tendon transfer |

Traditionally, transfer of the latissimus dorsi to the greater tuberosity was considered of choice for posterosuperior FIRCT, with satisfactory reported clinical outcomes at 10 years in well-selected patients [4]. However, lower trapezius transfer (LTT) has emerged as an attractive alternative to latissimus dorsi transfer [3, 5, 6•]. The relative benefits and disadvantages of these two tendon transfers are summarized in Table 2. This publication reviews the rationale, indications, contraindications, surgical technique, and outcomes of LTT for posterosuperior FIRCT.

Table 2.

Relative benefits and disadvantages of transfers of the latissimus dorsi and the lower trapezius to the greater tuberosity

| Latissimus dorsi transfer | Lower trapezius transfer |

|---|---|

|

• Direct transfer (sufficient excursion, does not need intercalary graft) • Out of phase (natural internal rotator, requires biofeedback training) • Poor results reported in the presence of subscapularis insufficiency • Potential to restore active external rotation in abduction • Long-term results available |

• Indirect transfer (insufficient excursion, needs intercalary graft) • In phase (contracts spontaneously with active external rotation) • Adequate results in subscapularis-deficient shoulders • Best to restore active external rotation with the arm at the side • No long-term results available |

Rationale

The lower trapezius muscle-tendon unit line of pull is very similar to the infraspinatus. In addition, active external rotation of the shoulder activates trapezius contraction (in phase). Several biomechanical studies have reported its biomechanical effectiveness to restore active external rotation, especially with the arm at the side [7–9]. After some training, harvesting the lower trapezius becomes relatively easy, although the muscular planes in the periscapular region are not as defined as in the front of the shoulder, and many shoulder surgeons may not be familiar with the relevant anatomy of this region. In addition, the technique can be performed with arthroscopic assistance. The main drawback of this procedure is the lack of adequate excursion of the lower trapezius to reach the greater tuberosity directly, needing an intercalary graft (indirect transfer). Another theoretical concern relates to the possibility of affecting scapulothoracic function adversely; however, abnormal scapulothoracic motion or periscapular pain has not been reported after LTT [6•, 8, 10•, 11•].

Indications and Contraindications

LTT is considered for shoulders with posterosuperior FIRCT provided there is no symptomatic glenohumeral joint cartilage degeneration or anterosuperior escape. Some surgeons have adopted this procedure for all shoulders with a posterosuperior FIRCT when reverse arthroplasty is best avoided; other surgeons indicate LTT more selectively. Severe weakness in external rotation, the presence of an external rotation lag sign, advanced fatty infiltration of the infraspinatus, and involvement of the teres minor are considered by most the ideal indication for LTT (Fig. 1).

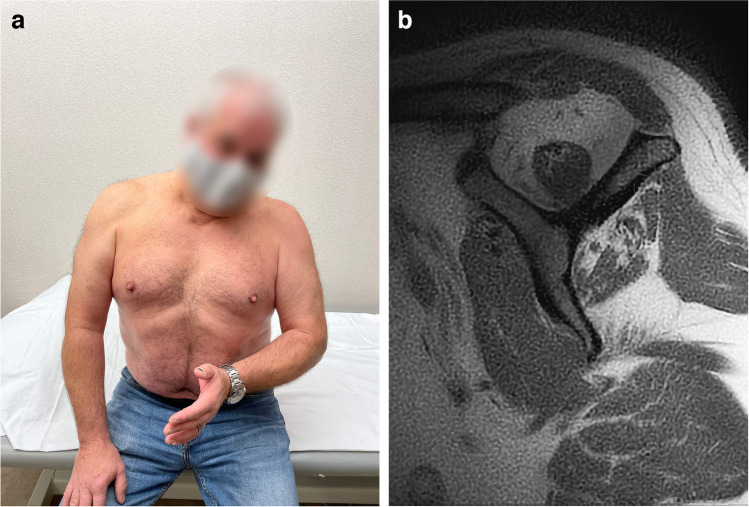

Fig. 1.

The ideal candidates for LTT are patients with a posterosuperior FIRCT, lack of active external rotation (A), and advanced fatty infiltration with involvement of the teres minor (B)

Alternative transfers, such as transfer of the latissimus dorsi, are considered contraindicated when there is associated subscapularis insufficiency. On the contrary, good outcomes have been reported with LTT even in the presence of subscapularis tears. However, many of those shoulders improve more with a dual anterior and posterior tendon transfer or a reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

Surgical Technique

LTT is an arthroscopically assisted surgical procedure that is combined with a partial repair of the rotator cuff whenever possible. Our preference is to perform the procedure in the beach-chair position and to use an Achilles tendon allograft as the intercalary graft, but this procedure can be performed in the lateral decubitus position and using an alternative autograft or allograft. When the decision to proceed with a LTT has been made preoperatively, we prefer to harvest the lower trapezius first; however, there are shoulders when the final decision to proceed with a LTT is based in the intraoperative assessment of cuff repairability, and in those shoulders, harvesting is performed later in the procedure.

Patient Position

As mentioned, we prefer to perform this procedure in the beach-chair position (Fig. 2). The surgical field should be prepared and draped to include the posterior aspect of the shoulder medial to the medial border of the scapular body. Use of an arthroscopic arm holder is very helpful and strongly recommended.

Fig. 2.

The patient is placed in the beach-chair position with the arm in a dedicated sterile arm holder and the surgical field prepared and draped medial to the medial border of the scapula. The black dashed lines represent the location of the spine and medial border of the scapula. The blue line represents the location of the skin incision

Lower Trapezius Harvest

A horizontal skin incision is placed just inferior and parallel to the medial half of the spine of the scapula and across the location of the medial edge of the scapular body. In certain individuals, substantial adipose tissue covers the tendon of the lower trapezius and needs to be excised. The inferior edge of the lower trapezius tendon appears falciform from this exposure, and lifting the trapezius with forceps can reveal the edge of the tendon and the plane between the lower trapezius and the underlying infraspinatus.

Once that dissection plane is established bluntly, the tendon of the lower trapezius can be followed laterally to its attachment on the inferior and dorsal aspect of the spine of the scapula. We typically detach the lower trapezius subperiosteally from lateral to medial, dividing it horizontally from the middle trapezius (Fig. 3A). Once the lower trapezius is completely detached, care must be taken to avoid further dissection medially deep to the trapezius muscle, since the neurovascular pedicle is in close proximity, and could be accidentally damaged. On the contrary, subcutaneous dissection superficial to the trapezius is safe and typically provides additional excursion (Fig. 3B).

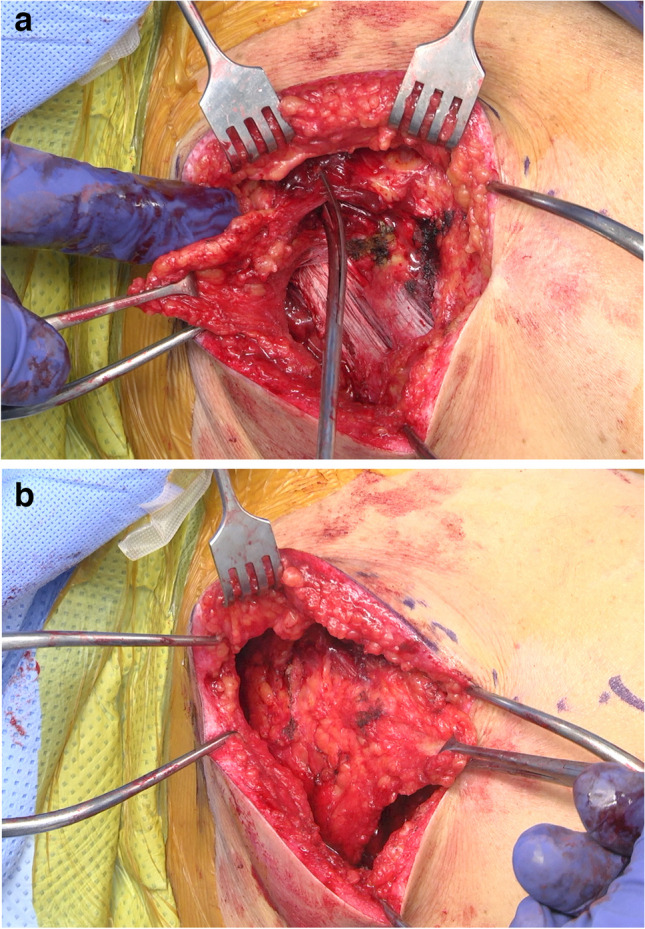

Fig. 3.

A The tendon of the lower trapezius is detached from the spine of the scapula and divided from the middle trapezius. B Subcutaneous dissection superficial to the lower trapezius may provide additional excursion

The fascia of the infraspinatus needs to be opened to pass the graft, but that step is delayed until the arthroscopic portion of the procedure is completed to avoid constant loss of arthroscopic irrigation solution through the fascial opening.

Graft Preparation

The narrower (calcaneal) end of the Achilles allograft is prepared to receive two non-absorbable sutures in a running locking configuration (Fig. 4). It is useful to use sutures of different colors. In addition, a marking pen can be used to color the side of the allograft that will be facing superiorly, so that the orientation of the graft is easier to visualize arthroscopically.

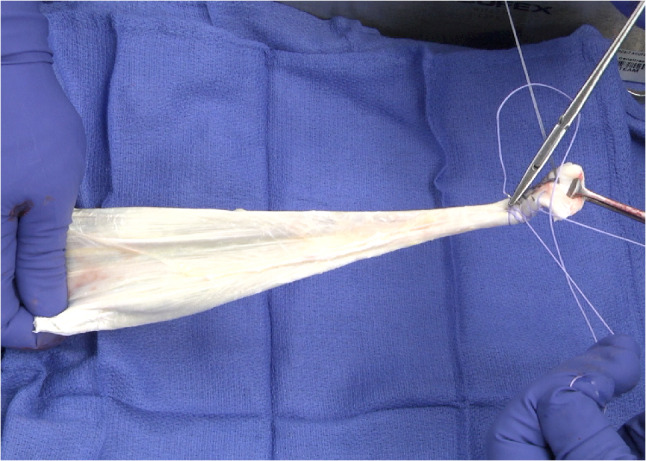

Fig. 4.

Preparation of the Achilles tendon allograft in the back table placing two nonabsorbable sutures in a running locking fashion

Arthroscopically Assisted Graft Fixation

The arthroscopic camera is introduced into the subacromial space through a posterolateral portal. A lateral subacromial portal is used to clear the subacromial bursa. Our preference is to associate a partial repair of the rotator cuff whenever possible. Some of the sutures or tapes used for partial cuff repair can be saved for additional fixation of the graft. If the severity of the rotator cuff tear is such that it does not lend itself to partial repair, one anchor with sutures or tapes may be inserted at the junction between the articular cartilage and the greater tuberosity to be used for the same purpose.

At that point, the superficial fascia of the infraspinatus is divided in line with its fibers to communicate the lower trapezius harvest site with the subacromial space. The sutures placed at the narrower end of the graft are passed through the split of the infraspinatus into the subacromial space and retrieved anteriorly; this can be accomplished with a large metallic clamp or shuttle sutures. Care is taking to pass these leading sutures of the graft lateral to any sutures or tapes that may have been saved for additional graft fixation.

Our preference is to have the graft wrap around the humerus horizontally and fix it to the anterior aspect of the greater tuberosity just posterior to the bicipital groove (Fig. 5). This is easily accomplished with knotless anchors to secure the leading sutures of the graft, one medial and one more lateral. Further fixation and compression are achieved by anchoring any saved sutures or tapes over the graft and into another knotless anchor while the graft is kept under tension.

Fig. 5.

A Schematic demonstrates the fixation strategy for the Achilles tendon to the greater tuberosity. B Arthroscopic photograph from a lateral viewing portal demonstrates fixation of the Achilles allograft

Graft to Lower Trapezius Repair

The wider end of the graft is then repaired to the lower trapezius. With the arm in maximal abduction and external rotation, traction is applied laterally to the lower trapezius and medially to the allograft. The repair can be performed in multiple ways. Our current preference is to pierce the graft end through the lower trapezius in a Pulvertaft fashion and complete the repair with multiple nonabsorbable and absorbable sutures (Fig. 6). Alternatively, the graft can be secured to the undersurface or the dorsal aspect of the trapezius. Repair to the dorsal aspect is probably the easiest, but leaves the allograft in a subcutaneous position, possibly prone to subcutaneous adhesions. Otherwise, we do not believe there are major merits or drawbacks to these different repair techniques.

Fig. 6.

A The allograft pierces the lower trapezius in a Pulvertaft fashion. B Completed tendon to allograft repair

Postoperative Management

After surgery, the affected upper extremity is placed in a shoulder immobilizer that positions the arm in external rotation. Currently, we use a commercially available external rotation brace (DonJoy ER™), which immobilizes the arm in approximately 20° of external rotation. No shoulder therapy is initiated until weeks 6 to 8 postoperatively. We prefer to avoid stretching in internal rotation for the first 3 months postoperatively. The physical therapy program follows the usual stages of first recovering motion and later introducing strengthening exercises with isometrics and elastic bands.

Outcomes

Outcome Studies

Several studies have documented the outcome of LTT for posterosuperior FIRCT. Elhassan et al. first reported on the outcome of open LTT for 33 shoulders in patients aged 31 to 66 (mean, 53 years) [5]. At a mean follow-up of 47 months, all but one patient experienced improvements in pain, subjective shoulder value, and quick-DASH. Average active motion included flexion to 120° and external rotation to 50°. Limited preoperative active elevation was associated with worse outcomes. The outcome of arthroscopically assisted LTT was reported later by Elhassan et al. in a group of 41 patients with an average age of 52 (range 37–71) years [6•]. Two-thirds were revision cuff repairs, and 19 shoulders exhibited true pseudoparalysis. All but five patients experienced improvements in pain, subjective shoulder value, and quick-DASH, with two transfer failures and two additional conversions to reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

Stone et al. reported on 15 LTT performed open [9] or arthroscopically [6•]. The mean age was 52 (range 31–62) years, 13 (93%) were manual laborers, and 9 (60%) had a worker’s compensation claim. Three patients (20%) underwent conversion to reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Of the remaining 12 patients, there were significant improvements in ASES, SANE, and STT scores at 2 years. Again, worse outcomes were reported in patients with poor preoperative active elevation. Chopra et al. reported on 19 patients with a mean age of 56.7 (range, 29–72) years [12]. Fifteen (80%) patients had unsuccessful previous rotator cuff repair. At an average follow-up of 14.6 months, there were significant improvements in postoperative pain VAS (6 vs 2), ASES score (45 vs 71), and PROMIS physical (43 vs 52), external rotation (10° vs 40°), and strength. All patients with a preoperative external rotation lag sign had reversal of their lag sign at the final follow-up. Of 17 work-eligible patients, 13 (76.4%) were able to return to work. MRI obtained 6 months after surgery demonstrated complete healing of the transferred tendon in all but 2 patients (90%).

De Marinis et al. recently published a systematic review on the outcomes of LTT [13]. These authors extracted relevant information regarding 159 patients included in 7 separate studies meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria. The mean age range was 52 to 63 years, 70% of the patients included were male, and the mean follow-up time ranged between 14 and 47 months. At the final follow-up, LTT led to improvements in motion (forward elevation and external rotation (mean gains of 10 to 66° and 11 to 63°, respectively). ER lag was present before surgery in 78 patients and was reversed after LTT in all shoulders. Patient-reported outcomes were improved at the final follow-up. The overall complication rate was 17.6%. The most common complication was seroma or hematoma (6.3%). The most common reoperation was conversion to reverse shoulder arthroplasty (5%) with an overall reoperation rate of 7.5%.

Comparative Studies

A few studies have compared LTT with latissimus dorsi transfer (LDT) or superior capsular reconstruction (SCR). Baek et al. compared the outcome of 48 LDT and 42 LTT [11•]. After a minimum follow-up time of 2 years, significant improvements in clinical outcomes were observed in both groups. Active shoulder external rotation, postoperative ASES scores, and ADLER scores were significantly higher after LTT, and the rate of progression of arthritis was significantly higher after LDT (31.3%) than after LTT (7.1%).

The same group compared the outcome of SCR (22 shoulders) versus LTT (36 shoulders) for posterosuperior FIRCT in shoulders with grade 4 fatty infiltration of the infraspinatus [10•]. Significant improvements in clinical outcomes were observed in both groups. However, LTT was associated with better overall outcomes, including better active shoulder ROM (forward elevation, 165.7° ± 22.3° vs 145.5° ± 32.3°; external rotation, 51.7° ± 10.9° vs 41.1° ± 7.0°), ASES scores (84.8 ± 7.6 vs 76.8 ± 20.3), and patient satisfaction (8.9 ± 1.2 vs 6.4 ± 2.1). The rate of progression of arthritis was significantly higher after SCR (22.7 vs 2.8%) (P = .027). Moreover, the graft retear rate was significantly higher after SCR (63.6% vs 8.3%).

Marigi et al. also compared the outcome of SCR and LTT [14•]. In this study, patients with a substantial external rotation lag sign were preferentially treated with LTT, and before surgery, patients in the LTT group had more advanced fatty infiltration of the teres minor and global fatty infiltration. At a mean follow-up 3 (range, 2–6 years), no differences in patient-reported outcome scores were observed. Postoperatively, SCR patients had a less pain (0.3 vs 1.1), better elevation (156° vs 143°), and marginally better strength in elevation (4.8 vs 4.5). LTT patients showed greater improvement in external rotation (17° vs 29°). There were no statistically significant differences in complication (9.4% vs 12.5%) or reoperation rates (3.1% vs 10%).

Wagner et al. also compared the 2-year outcomes of SCR with either LDT or LTT [15]. In their study, 163 patients underwent SCR and 24 arthroscopically assisted TT. The mean age was 60 and 56 years, respectively. Both procedures produced improved outcomes at each postoperative time point compared to preoperative. The pain and functional outcomes measures (VAS, ASES, SANE, and VR-12 physical) were comparable. At 2 years postoperatively, there were no significant differences.

In summary, the current available literature seems to indicate that the LTT is a successful salvage solution for many patients with FIRCT. One study indicates that LTT is superior to LDT. SCR and LTT seem to provide similar outcomes for all comers, but LTT is superior for patients with more advanced rotator cuff disease and seems to be associated with lower rates of graft rupture or progression of osteoarthritis.

Cost Considerations

One study has compared the cost of LTT, SCR, and reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Marigi et al. calculated the costs of 20 SCR, 47 LTT, and 88 reverse arthroplasties performed at the same institution between 2018 and 2020 [16•]. SCR resulted in an additional average cost of $3953 and $3598 compared with LTT and reverse arthroplasty, respectively. Mean standardized costs were as follows: preoperative evaluation SCR $507, LTTT $507, and RSA $730; index surgical hospitalization SCR $19,675, LTTT $15,722, and RSA $16,077; and postoperative care SCR $655, LTTT $686, and RSA $404.

Impact on Revision to Reverse Arthroplasty

One study has reported the outcome of RSA after failed tendon transfers for posterosuperior cuff tears [17•]. Marigi et al. reported on 33 patients who underwent RSA implantation between 2006 and 2019 with a previous failed tendon transfer (FTT) of the shoulder and at least 2 years of clinical follow-up. Prior tendon transfers included 21 latissimus dorsi transfers, 6 latissimus dorsi and teres major (LD-TM) transfers, and 6 lower trapezius transfers. RSAs were performed at an average of 5.5 years (range, 0.3–28 years) after the tendon transfer procedure, with a mean follow-up period of 4 ± 2 years. RSA significantly improved pain and function, with improvements in the visual analog scale pain score (6.2 preoperatively vs 2.2 at most recent follow-up), active elevation (85° vs 111°), American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score (51 vs 74), absolute CS (34 vs 48), and relative CS (42% vs 59502), exceeding the minimal clinically important difference threshold. There were seven complications (21%) across the entire cohort, with dislocation (3 shoulders, 9.1%) as the most common complication. Comparison across TT groups showed that the LD-TM transfer had the highest complication rate (3 shoulders, 50%). Survivorship free of revision or reoperation was estimated to be 90% at 1 year, 85% at 2 years, and 71% at 5 years, with no difference among groups.

Conclusions

Posterosuperior FIRCT can be associated with substantial pain and morbidity. Indirect transfer of the tendon of the lower trapezius has emerged as a successful surgical procedure for patients with this condition. The procedure is performed typically using arthroscopically assisted techniques. Studies published in the peer-reviewed literature have reported high rates of improvement in terms of pain, motion, strength, and patient-reported outcomes. LTT seems to be superior to other procedures, such as SCR, for patients with an external rotation lag sign, severe infraspinatus fatty infiltration, and involvement of the teres minor. The reported cost of LTT seems to be similar to RSA and less expensive than SCR. However, failures do occur, with reported reoperation rates around 10%. When RSA is performed in patients with prior failed LTT, the outcome and complication rates of the arthroplasty do not seem to be worse.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Sanchez-Sotelo receives royalties and consulting fees from Stryker, consulting fees from Acumed, and consulting fees from Exactech. Dr. Sanchez-Sotelo also receives publishing royalties from Elsevier and Oxford University Press. Other potential conflicts of interest include stock options in Orthobullets, PSI, and Precision OS, as well as honorarium from Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised due to incorrect data in “Comparative Studies” and “Conclusions” sections.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

3/16/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s12178-024-09891-1

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

- 1.Yanik EL, Chamberlain AM, Keener JD. Trends in rotator cuff repair rates and comorbidity burden among commercially insured patients younger than the age of 65 years, United States 2007–2016. JSES Rev Rep Tech. 2021;1(4):309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.xrrt.2021.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen AR, Taylor AJ, Sanchez-Sotelo J. Factors influencing the reparability and healing rates of rotator cuff tears. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2020;13(5):572–83. doi: 10.1007/s12178-020-09660-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burnier M, Elhassan BT, Sanchez-Sotelo J. Surgical management of irreparable rotator cuff tears: what works, what does not, and what is coming. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101(17):1603–12. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.18.01392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerber C, Rahm SA, Catanzaro S, Farshad M, Moor BK. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for treatment of irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears: long-term results at a minimum follow-up of ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(21):1920–6. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elhassan BT, Wagner ER, Werthel JD. Outcome of lower trapezius transfer to reconstruct massive irreparable posterior-superior rotator cuff tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(8):1346–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elhassan BT, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Wagner ER. Outcome of arthroscopically assisted lower trapezius transfer to reconstruct massive irreparable posterior-superior rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(10):2135–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartzler RU, Barlow JD, An KN, Elhassan BT. Biomechanical effectiveness of different types of tendon transfers to the shoulder for external rotation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(10):1370–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clouette J, Leroux T, Shanmugaraj A, Khan M, Gohal C, Veillette C, et al. The lower trapezius transfer: a systematic review of biomechanical data, techniques, and clinical outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(7):1505–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omid R, Heckmann N, Wang L, McGarry MH, Vangsness CT, Jr, Lee TQ. Biomechanical comparison between the trapezius transfer and latissimus transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(10):1635–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baek CH, Lim C, Kim JG. Superior capsular reconstruction versus lower trapezius transfer for posterosuperior irreparable rotator cuff tears with high-grade fatty infiltration in the infraspinatus. Am J Sports Med. 2022;50(7):1938–47. doi: 10.1177/03635465221092137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baek CH, Lee DH, Kim JG. Latissimus dorsi transfer vs. lower trapezius transfer for posterosuperior irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31(9):1810–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2022.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chopra A, Wright MA, Murthi AM. Outcomes after arthroscopic-assisted lower trapezius transfer with achilles tendon allograft. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2024;33:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2023.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Marinis R, Marigi EM, Atwan Y, Velasquez Garcia A, Morrey ME, Sanchez-Sotelo J. Lower trapezius transfer improves clinical outcomes with a rate of complications and reoperations comparable to other surgical alternatives in patients with functionally irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2023.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marigi EM, Jackowski JR, Elahi MA, Barlow J, Morrey ME, Camp CL, et al. Improved yet varied clinical outcomes observed with comparison of arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction versus arthroscopy-assisted lower trapezius transfer for patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2023;39:2133–2141. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2023.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner ER, Woodmass JM, Welp KM, Chang MJ, Higgins L, Warner JJP. Early postoperative recovery comparisons of superior capsule reconstruction to tendon transfers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32(2):276–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2022.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marigi EM, Johnson QJ, Dholakia R, Borah BJ, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Sperling JW. Cost comparison and complication profiles of superior capsular reconstruction, lower trapezius transfer, and reverse shoulder arthroplasty for irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31(4):847–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2021.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marigi EM, Harstad C, Elhassan B, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Wieser K, Kriechling P. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty after failed tendon transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31(4):763–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2021.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]