Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 infection in children is usually asymptomatic/mild. However, some patients may develop critical forms. We aimed to describe characteristics and evaluate the factors associated to in-hospital mortality of patients with critical COVID-19/MIS-C in the Amazonian region. This multicenter prospective cohort included critically ill children (1 mo–18 years old), with confirmed COVID-19/MIS-C admitted to 3 tertiary Pediatric Intensive Care Units (PICU) in the Brazilian Amazon, between April/2020 and May/2023. The main outcome was in-hospital mortality and were evaluated using a multivariable Cox proportional regression. We adjusted the model for pediatric risk of mortality score version IV (PRISMIV) score and age/comorbidity. 266 patients were assessed with 187 in the severe COVID-19 group, 79 included in the MIS-C group. In the severe COVID-19 group 108 (57.8%) were male, median age was 23 months, 95 (50.8%) were up to 2 years of age. Forty-two (22.5%) patients in this group died during follow-up in a median time of 11 days (IQR, 2–28). In the MIS-C group, 56 (70.9%) were male, median age was 23 months and median follow-up was 162 days (range, 3–202). Death occurred in 17 (21.5%) patients with a median death time of 7 (IQR, 4–13) days. The mortality was associated with higher levels of Vasoactive Inotropic-Score (VIS), presence of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), higher levels of Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate, (ESR) and thrombocytopenia. Critically ill patients with severe COVID-19 and MIS-C from the Brazilian Amazon showed a high mortality rate, within 12 days of hospitalization.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2 virus, Intensive Care Unit, Pediatric, Child health, Risk factor, Mortality

Subject terms: Paediatric research, Viral infection, Medical research, Infectious diseases

Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) has affected over 100 million people worldwide, overwhelmed the health care system, and caused significant morbidity and mortality. In comparison to adults, children are less frequently affected, and most of them present with mild symptoms and better prognosis1,2. In hospitalized children, the presence of underlying medical conditions and age under one year old increases the risk of critical illness related to SARS-CoV-2, such as severe COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)1–3.

Several studies have been performed in high income countries, demonstrating characteristics of children with severe COVID-19/MIS-C requiring admission to Pediatric Intensive Care Units (PICU). Data regarding characteristics of critically ill children with COVID-19/MIS-C, and unfavorable prognosis, in resource-restricted regions, is lacking. Therefore, the risk factors for worse outcomes of COVID-19 in these studies may not be entirely applicable to other geographic regions or to less developed countries, which limits the extrapolation of the results1–5.

The Brazilian Amazonian region is recognized for economic, political, social, and environmental disparities, and is characterized by a vast territorial area which may result in lower quality of healthcare and limited accessibility to health services. However, the metropolitan region of Belém has PICUs with healthcare staff trained to care for critically ill children, adequate numbers of staff, and rapid access to necessary medications, supplies and equipment. The health disparities continue to exist in this region as a major issue that adversely affects groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health care which result in an increase in health inequalities.

Given the genetic, socioeconomic conditions and healthcare access in the Amazonian region, critical COVID-19/MIS-C may exhibit different outcomes, including severity, duration, and sequelae compared to what has been described in other parts of the world4–7. We aimed to describe characteristics and evaluate the independent factors associated to in-hospital mortality of patients with critical COVID-19/MIS-C in the Amazonian region.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This multicenter prospective study included critically ill children between 1 month and 18 years of age, with confirmed critical COVID-19/MIS-C, admitted to PICU, from three tertiary Hospitals in the Brazilian Amazon, between April 2020 and May 2023. Patients with other causes of infection with similar presentations and absence of criteria for PICU were excluded. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the coordinating center (the other centers were co-participants). All participants and their legal guardians provided written informed assent and/or consent.

All children admitted to this study underwent diagnostic tests for the presence of SARS-CoV-2. SARS-CoV-2 infection was diagnosed either by nasopharyngeal swab RT-PCR and/or rapid antibody test for SARS-CoV-2, or serological test as recommended. Patients referred from outside facilities had previously had a mandatory test and even so, at the time of admission, a new exam was performed. Included children were separated into 2 groups: severe COVID-19 and critical MIS-C. Each group was split into two subgroups, based on in-hospital mortality at 28th day: survival and non-survival. All outcomes and the worst features were recorded and compared between the 2 groups.

Data collection

The patients included in the study were prospectively assessed from date of hospital admission until discharge or death. The PICU admission criteria were the same in the three hospitals as there were specific guidelines and all of them are references in pediatric intensive care in the state. There was no uniform management protocol formulated by the researchers, however, in all units, the management protocol of pediatric patients with severe COVID-19/MIS-C was based on the recommendations of the Health Ministry. All parameters were collected and processed at the participating medical centers using standardized data collection forms, and all involved institutions used the same laboratory network for the analyses. In cases of readmission to PICU, only the first hospitalization was considered.

Data included demographic information, clinical, therapeutic, and outcomes. Laboratory and ventilatory parameters were evaluated on the first day of hospitalization. Presenting symptoms, respiratory support requirements, use of vasoactive medications and laboratory parameters, including inflammation markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate—[ESR], C-reactive protein [CRP], d-dimer, fibrinogen, ferritin and triglycerides), and cardiac function (troponin T and creatine phosphokinase MB fraction [CPK-MB]) were collected. In addition, mortality and severity scores8,9, treatment, and unfavorable outcomes, were also assessed.

Critical disease included respiratory failure requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), shock, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and/or multiorgan failure with at least one organ involvement. Multiple organ dysfunctions (MOD) were defined by the current criteria10. Severe COVID-19 was defined by the presence of positive real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), or antigen, and at least one organ dysfunction involvement, according to the current criteria10,11. MIS-C was defined according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria11. All patients admitted to the units underwent the test before admission and were positive for antigen test and/or RT-PCR test. To the patients who had MIS-C criteria a serological test was added, as well in severe COVID-19 patients when the clinical presentation was similar to MIS-C.

Chest computed tomography and echocardiographic findings were recorded. Echocardiography was performed in patients with features of shock, unexplained tachycardia, and symptoms suggestive of MIS-C. Myocardial dysfunction was defined by the presence of global or segmental contractibility alterations, ventricular dilation, ejection fraction less than 55% measured by modified Simpson’s method, and troponin levels above the reference value10–12.

Treatment received by the patients such as: type of highest respiratory support, the number of ventilator days in those requiring invasive ventilation, highest Vasoactive Inotropic-Score (VIS)13 and current drug treatment (intravenous methylprednisolone pulse therapy, intravenous immunoglobulin, and low molecular heparin), were also analyzed. A standard ventilatory protocol was used in this study14. Septic shock related to COVID-19, ARDS, and acute kidney injury, were defined and managed as per the Surviving Sepsis Campaign International Guidelines for the Management of Septic Shock in children12, Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference (PALICC) definition15, and kidney disease: Improving Global Outcome classification system (KDIGO) guidelines16, respectively. We defined a SARS-CoV-2 infection associated pediatric death as death occurring in a patient with confirmed severe COVID-19/MIS-C who died after PICU admission. The admission criteria for PICU, was determined by the finding of multiorgan failure with at least one organ involvement which requires monitoring in the PICU, or diagnosis of acute respiratory syndrome or respiratory failure, circulatory shock of any kind, encephalopathy, hepatic or gastrointestinal dysfunction, myocardial dysfunction or heart failure, coagulation disorders, and acute kidney injury10,12, 15, 16. The primary outcome of interest was in-hospital mortality at 28th day.

Statistical analysis

Cohort characteristics were summarized using median (interquartile range) for continuous variables, and frequencies (%) for categorical variables. Comparisons between groups were made using χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables, and Mann–Whitney U was used for continuous data. Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons was employed, adjusting the significance level when patients were compared in two groups (survival and non-survival). Survival rates in days, were calculated, and Kaplan–Meier curves were plotted for categorical variables or using the method of fractional polynomials to access the scale of continuous variables. To determine risk factors for survival we performed univariate and multivariate analyses using continuous variables for the Cox regression “time-to-first-event” analysis. In the regression model we adjusted for a risk of mortality using pediatric risk of mortality score version IV (PRISMIV) score, age under one year old, and presence of comorbidity simultaneously. For these analyses the adopted significance level was set at two-sided p < 0.05. Data analyses were conducted using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Chicago, IL) version 27.0.

Ethics statement

The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the coordinating center (the other centers were co-participants). The parents or guardians of the children, or, when applicable, the children themselves, provided written informed consent before being included in the study. Besides, confidentiality was maintained by keeping privacy at all levels of the study. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of FSCMPA under number 0361/2017, opinion nº 4.060.894, CAAE 31513320.0.0000.5171.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents.

Results

Description of selection criteria for the Cohort

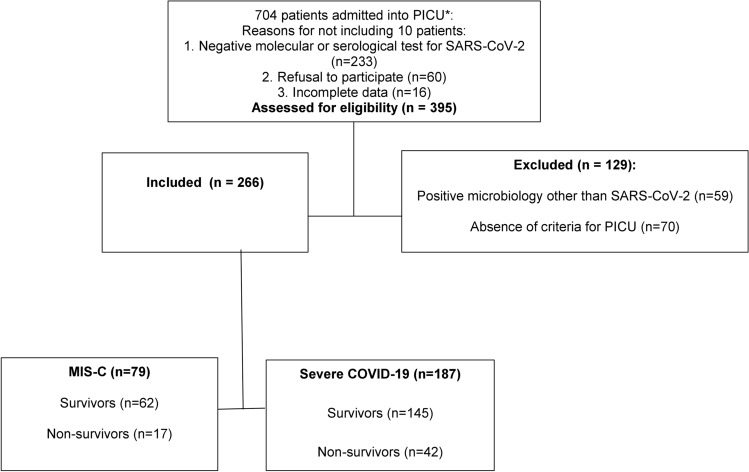

In Brazil from April 2020 to June 2023, 2055 patients under 18 years old presented with confirmed MIS-C, with 140 (6.8%) deaths, while 59,059 patients under 18 years old presented with confirmed severe COVID-19, and were hospitalized, with 3571 (6.1%) deaths17–20. The vaccination coverage was around 7% in children under 2 years of age20. From a population of 704 patients admitted to PICUs in Belém, state of Pará, Brazil, with suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection, from April 01, 2020, to May 31, 2023, 204 patients were excluded due to the following reasons: negative molecular or serological test for SARS-CoV-2 (n = 233), absence of criteria for PICU (n = 70), and/or positive microbiology other than SARS-CoV-2 (n = 59); 7 were positive for other respiratory viruses, 39 were positive for bacteria, and 13 were positive for fungi. Data from 266 patients (median age, 33 [IQR, 9–36] months) was analyzed. The cohort was composed of 190 (71.4%) patients from the FSCMPA’s PICU, 60 (22.6%) patients from Hospital Mario Pinnoti’s PICU, and 16 (6%) from Fundacao Hospital de Clínicas’ Gaspar Viana. The mortality rate was 22.2% (59 patients). varying between 6.3 and 26.3% among the three units (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart describing the study design and selection of participants. PICU, Pediatric Intensive care unit.

MIS-C group

The MIS-C group had 79 patients included, 56 (70.9%) were male, 40 (50.6%) were Brazilian pardo, with 17 (21.5%) non survival and 62 (78.5%) survival. The median age in the non-survival group was 17 months (IQR:5–33), 10 (58.8%) patients were Brazilian pardo and 15 (88.2%) were males. The main clinical presentation of MIS-C was Shock syndrome associated to Kawasaki disease, with 7 (41.2%) non-survival. Comorbidities were more frequent in the non-survival MIS-C group (48 [77.4%] vs. 16 [94.1%]), and also the need for IMV (17 [100%] vs. 38 [61.3%], p < 0.001). Myocardial dysfunctions were more pronounced in non-survival who clinically presented with cardiogenic shock (13 [76.5%] vs 20 [42.6%], p = 0.023) and higher VIS levels (median 163, IQR121-176, vs 12, IQR0-71). In MIS-C patients the Compliance Respiratory system (CRS) and driving pressure was not different and improved in a similar degree in both groups, survival (CRS median 0.6 mL/cmH2O/kg vs. 0.89 mL/cmH2O/kg, DP median 10 cmH2O vs. 9 cmH2O) and non-survival (median 0.67 mL/cmH2O/kg vs. 0.84 mL/cmH2O/kg, DP median 16 cmH2O vs. 17 cmH2O), with no statistical significance, with Wilcoxon test p = 0.135 and p = 0.34 for CRS and DP, respectively. The increase of ventilatory ratio21,22 in the MIS-C patients was performed to maintain the PCO2 levels according to the Tidal volume values. Some ventilatory settings and laboratory parameters were also associated with deaths, such as higher drive pressure levels, and worse hypoxemia at admission, and after 48 h, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with critical MIS-C, according to in-hospital mortality.

| Characteristics of patients with critical MIS-C | Survival (n = 62) | Non-survival (n = 17) | All patients (n = 79) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiological and demographics | ||||

| Age in months median (IQR) | 28 (5–119) | 17 (5–33) | 23 (5–112) | 0.126 |

| Children under 2 years old n (%) | 29 (46.8) | 11 (64.7) | 40 (50.6) | 0.274 |

| Sex: male n (%) | 41 (66.1) | 15 (88.2) | 56 (70.9) | 0.129 |

| Ethnicity: Brazilian pardo n (%) | 30 (48.4) | 10 (58.8) | 40 (50.6) | 0.585 |

| Pediatric complex chronic conditions n (%) | 48 (77.4) | 16 (94.1) | 64 (81.0) | 0.785 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Neurologic and neuromuscular diseases | 13 (27.1) | 6(37.5) | 19 (29.7) | 0.756 |

| Gastrointestinal diseases | 9 (18.8) | 4 (25) | 13 (20.3) | 1.000 |

| Respiratory diseases | 8 (16.7) | 3 (18.8) | 11 (17.2) | 1.000 |

| Time from exposure to symptom onset in days, median (IQR) | 14 (11–21) | 14 (9–25) | 14 (11–23) | 0.905 |

| Duration of fever in days, median (IQR) | 11 (7–13) | 8 (5–12) | 10 (6–12) | 0.174 |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed tests n (%) | ||||

| IgG | 20/124 (16.1)** | 3/34 (8.8)** | 23/158 (14.6)** | 0.412 |

| Antigen test | 42/124 (33.9) | 14/34 (41.2) | 56/158 (35.4) | 0.431 |

| RT-PCR test | 12/124 (9.7) | 4/34 (11.8) | 16/158 (10.1) | 0.75 |

| BMI-for-age Z-scores > 5 years old: moderately underweight n (%) | 11 (17.7) | 4 (23.5) | 15 (19.0) | 1.000 |

| BMI-for-age Z-scores < 5 years old: Normal weight n (%) | 4 (6.5) | 2 (11.8) | 6 (7.6) | 0.144 |

| Clinical | ||||

| MIS-C clinical form: Shock syndrome Kawasaki disease n (%) | 23 (37.1) | 7 (41.2) | 30 (38.0) | 0.783 |

| Lymphadenopathy n (%) | 37 (59.7) | 10 (58.8) | 47 (59.5) | 1.000 |

| Severe dyspnea n (%) | 17 (34.7) | 12 (75) | 29 (44.6) | 0.008 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms n (%) | 40 (64.5) | 14 (82.4) | 54 (68.4) | 0.240 |

| Pneumonia n (%) | 35 (56.5) | 13 (76.5) | 48 (60.8) | 0.168 |

| Exanthema n (%) | 40 (64.5) | 15 (88.2) | 55 (69.6) | 0.078 |

| Cardiogenic Shock n (%) | 20 (42.6) | 13 (76.5) | 33 (51.6) | 0.023 |

| VIS median (IQR) | 12 (0–71) | 163 (121–176) | 39 (0–91) | < 0.001 |

| Oxygen therapy modalities n (%) | ||||

| Oxygen low interfaces | 11 (17.7) | 0 (0) | 11 (13.9) | 0.108 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 38 (61.3) | 17 (100) | 55 (69.6) | < 0.001 |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 13 (21.0) | 0 (0) | 13 (16.5) | 0.059 |

| Ventilator weaning success at first attempt n (%) | 36 (94.7) | 5 (5.9) | 41 (74.5) | < 0.001 |

| Tracheostomy tube use n (%) | 2 (5.3) | 1 (5.9) | 3 (5.5) | 1.000 |

| ADRS n (%) | 23 (37.1) | 17 (100) | 40 (50.6) | < 0.001 |

| Severe ARDS n (%) | 5 (8.1) | 10 (58.8) | 15 (19) | 0.004 |

| MOD > 2 organ involvement n (%) | 41 (66.1) | 17 (100) | 58 (73.4) | 0.004 |

| Renal replacement therapy n (%) | 8 (12.9) | 1 (5.9) | 9 (11.4) | 0.675 |

| KDIGO stage 1, n (%) | 20 (32.3) | 16 (94.1) | 36 (45.6) | < 0.001 |

| Treatment n (%) | ||||

| Low molecular weight heparin therapy | 33 (53.2) | 16 (94.1) | 49 (62.0) | 0.003 |

| Methylprednisolone pulse therapy | 6 (9.7) | 13 (76.5) | 19 924.1) | 0.002 |

| Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy | 37 (59.7) | 17 (100) | 54 (68.4) | 0.002 |

| Outcomes median (IQR) | ||||

| Length of stay at hospital, in days | 15 (10–18) | 11 (6–14) | 14 (9–18) | 0.105 |

| Length of stay at PICU, in days | 6 (4–8) | 11 (6–14) | 6 (4–9) | 0.01 |

| Mechanical ventilation time, in days | 4 (3–6) | 11 (6–14) | 4 (3–9) | < 0.001 |

| Ventilator free days at 28th | 24 (22–25) | 0 (0–1) | 22 (1–25) | < 0.001 |

| PRISMIV% | 1.5 (1.2–2.8) | 5.9 (1.9–32) | 2.8 (1.5–26.4) | 0.009 |

| PELOD-2 | 9.5 (5–20) | 15 (3–21) | 11 (4–20) | 0.9 |

| Ventilatory settings and Respiratory mechanics median (IQR) Day 1 | ||||

| Tidal volume in ml/kg | 6.3 (5.4–7.3) | 9.9 (9.3–10.6) | 6.9 (5.6–9.5) | < 0.001 |

| Respiratory rate breaths/min | 24 (23–29) | 25 (22–30) | 26 (23–30) | 0.813 |

| Peep-peak paw in cmH2O | 9 (7–10) | 22 (18–24) | 17 (10–23) | 0.001 |

| Driving pressure in cmH2O | 9 (8–11) | 17 (16–18) | 11 (9–16) | < 0.001 |

| Compliance respiratory system in mL/cmH2O/kg | 0.6 (0.59–0.89) | 0.67 (0.42–0.99) | 0.64 (0.56–0.97) | 0.91 |

| Ventilatory ratioa | 0.68 (0.48–1.61) | 0.76 (0.62–1.13) | 0.74 (0.53–1.3) | 0.698 |

| Laboratorial features median (IQR) Day 1 | ||||

| Oxygenation index | 5.3 (2.5–10) | 10.6 (8.9–15.6) | 8.4 (3.5–12.3) | < 0.001 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 238 (160–367) | 159 (111–181) | 204 (141–358) | < 0.001 |

| pO2 (mmHg) | 125.5 (72.4–180) | 128 (73–151) | 128 (72.4–179) | 0.456 |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 37.6 (28.6–55.9) | 37 (29.4–50.6) | 37.1 (28.8–55.9) | 0.952 |

| Sodium bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 20.9 (18.2–23.7) | 15.7 (13.8–22.9) | 20.7 (16.3–23.7) | 0.043 |

| Anion gap (mmol/L) | 7.7 (12.2–16.9) | 18.2 (10.4–24.9) | 16.9 (9.5–21.4) | 0.016 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 2.3 (1.7–2.9) | 2.7 (2–2.9) | 2.3 (1.7–2.9) | 0.962 |

| Platelets count/mm3 | 194,000 (120,000–352,000) | 28,000 (19,700–31,300) | 152,000 (45,300–308,000) | < 0.001 |

| Lymphocytes count/mm3 | 1,352 (1,038–1,998) | 1,033 (774–1,428) | 1,270 (978–1,870) | 0.023 |

| INR | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 1.2 (1.0–1.7) | 1.2 (1–1.5) | 0.440 |

| d-Dimer (ng/dL) | 1,917 (959–5,009) | 1,606 (1,209–2,938) | 1,789 (959–4,254) | 0.872 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 288 (145–453) | 226 (160–254) | 269 (145–385) | 0.113 |

| C-reactive protein(mg/dL) | 34 (14,6–80,8) | 77.6(34.5–88.7) | 40.7 (16.2–85) | 0,09 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 12 (8–16) | 45 (35–54) | 14 (9–22) | < 0.001 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 548 (291–597) | 582 (482–1,112) | 550 (298–616) | 0.018 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 26 (17–46) | 22 (19–38) | 25 (17–46) | 0.441 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.4 (0.3–0.9) | 0.4 (0.3–0.4) | 0.4 (0.3–0.8) | 0.480 |

| AST (IU/L) | 45 (35–75) | 50 (38–64) | 46 (35–75) | 0.527 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 35 (17–52) | 38 (17–60) | 35 (17–52) | 0.716 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.7 (2.3–3.8) | 2.9 (2.5–3.5) | 2.7 (2.3–3.8) | 0.810 |

| Troponin I (ng/L) | 0.124 (0.01–1.35) | 4.57 (2.1–11.31) | 0.27 (0.03–2.8) | < 0.001 |

| Ventilatory settings and Respiratory mechanics median (IQR) Day 2 | ||||

| Tidal volume in ml/kg | 5.8 (5.2–7.4) | 9.7 (9–10) | 7.2 (5.5–9.6) | < 0.001 |

| Respiratory rate breaths/min | 27 (23–29) | 28 (22–30) | 28 (23–30) | 0.813 |

| Peep- Peak Paw in cmH2O | 10 (7–11) | 19 (17–23) | 17(10–22) | 0.001 |

| Driving pressure in cmH2O | 10 (9–12) | 16 (15–17) | 12 (9–16) | < 0.001 |

| Compliance respiratory system in mL/cmH2O/kg | 0.89 (0.6–1.13) | 0.84 (0.51–1.12) | 0.87 (0.57–1.12) | 0.68 |

| Ventilatory ratioa | 0.86 (0.6–1.08) | 1.06 (0.88–2.2) | 1.0 (0.69–1.86) | 0.126 |

| Laboratorial features median (IQR) Day 2 | ||||

| Oxygenation index | 4.1 (2.3–8.1) | 10.9 (4.9–13.9) | 6.5 (3.3–10.9) | 0.006 |

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 348 (183–450) | 151 (102–242) | 257 (150–425) | 0.001 |

| pO2 (mmHg) | 124 (58–157) | 106 (59–131) | 111 (55–147.5) | 0.116 |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 42 (34–65) | 46 (42–49) | 45 (34–63) | 0.479 |

| Sodium bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 23 (19.4–27) | 18.1 (15.8–20.3) | 21 (17.7–25.6) | 0,002 |

| Anion gap (mmol/L) | 11.7 (5.2–20.7) | 15.3 (10.4–23.8) | 13.3 (6.7–21.5) | 0.07 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 1.4 (1–2.8) | 3.5 (2.1–7.9) | 1.9 (1.2–4) | 0.059 |

| Platelets count/mm3 | 265,800 (135,000–376,700) | 301,000 (172,000–450,000) | 279,000 (138,600–448,000) | 0.761 |

| Lymphocytes count/mm3 | 2,266 (1,346–5,000) | 1,807 (1,102–2,934) | 2,246 (1,248–4,525) | 0.095 |

| INR | 1.1 (1–1.4) | 1.11 (1.02–1.3) | 1.1 (1.01–1.38) | 0.2 |

| d-Dimer (ng/dL) | 1,002 (602 -1,795) | 1,291 (690–3,861) | 1,264 (609–3,861) | 0.161 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 203 (101–380) | 170 (64–381) | 203 (78–380) | 0.605 |

| C-reactive protein(mg/dL) | 21 (7.8–41) | 23 (7.5–67) | 20 (7.3–60) | 0.938 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 20 (10–20) | 56 (51–60) | 20 (12–30) | < 0.001 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 149 (94–851) | 329 (169–580) | 329 (132–580) | 0,06 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 15 (7–49) | 34 (19–56) | 31 (14–52) | 0.037 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.3 (0.25–0.5) | 0.45 (0.25–0.6) | 0.4 (0.25–0.6) | 0.417 |

| AST (IU/L) | 41 (33–80) | 53 (33–62) | 49 (33–70) | 0.605 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 31 (16–55) | 32 (17–60) | 31 (16–56) | 0.543 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.7 (2.4–3.2) | 2.8 (2.3–3.1) | 2.8 (2.5–3.2) | 0.272 |

| Troponin I (ng/L) | 0.1 (0.01–7.8) | 0.2 (0,02–19.5) | 0.2 (0.012–13.4) | 0.889 |

BMI, body mass index. VIS, vasoactive-inotropic score. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome. MOD, Multiple organ dysfunction. KDIGO, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome classification system. Peep, Positive end-expiratory pressure. Paw, peak airway pressure. *The bold numbers refer to two-sided p value using Bonferroni correction (p < 0.001). Mechanical ventilation time, Ventilator weaning success at first attempt Oxygen inspired fraction %, was not used to avoid multicolinearity in the regression model. **All patients admitted to units underwent the test before admission and were positive for antigen test and/or RT-PCR test the patients who had MIS-C criteria we added serological test. aVentilatory ratio was defined as (minute ventilation × PaCO2)/(PBW × 100 × 37.5)21, because the predicted minute ventilation used in adults (100 mL/kg/min predicted body weight) does not apply over the age range of children and young adults, a pediatric predicted minute ventilation was used 22.

Severe COVID-19 group

From 187 patients analyzed, 108 (57.8%) were male, median age was 23 months, 95 (50.8%) were up to 2 years of age, 78 were Brazilian pardo (41.7%), and 108 (57.8%) had at least one comorbidity. Forty-two (22.5%) patients died during follow-up, with a median time of 11 days (range, 2–28). Pneumonia was present in 33 (78.6%) in the non-survival group, with all deceased patients requiring IVM, only 15 (35.7%) had presented with severe ARDS. Some ventilatory settings and laboratory parameters were also associated with death, such as higher drive pressure levels, and worse hypoxemia. More pronounced lymphopenia at admission and higher levels of ESR at admission, as well as other parameters, were more frequent in non-survival compared to survival. We observed that on the second day of hospitalization, oxygen exchange was different between survival and non-survival (PaO2/FiO2 ratio, median 206 vs. 289, p = 0.018, Oxygen inspired fraction %, median 60 vs. 40, p = 0.57, and higher driving pressure levels median 10 vs. 8 cmH2O, p < 0.001), in addition to acute phase reactant (erythrocyte sedimentation rate in mm/h median, 44 vs. 15, p < 0.001) and pronounced coagulation disorders (median INR, 1.48 vs 1.26, p = 0.002). The increase of ventilatory ratio21,22 in the patients with severe COVID-19 patients was performed to maintain the PCO2 levels according to the Tidal volume values. In severe COVID-19 patients who died exhibited a significant deterioration of CRS between day 1 (median 0.78 mL/cmH2O/kg) and day 2 (median 0.60 mL/cmH2O/kg), as well as DP (day 1 median 13 cmH2O vs 10 cmH2O) despite having a higher value at the first day on IMV (Wilcoxon test p < 0.001 for both variables), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients with severe COVID-19, according to the in-hospital mortality group.

| Characteristics of patients with severe COVID-19 | Survival (n = 145) | Non-survival (n = 42) | All patients (n = 187) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epidemiological and demographics | ||||

| Age in months median (IQR) | 82 (12–132) | 19 (6–82) | 23 (6–81) | 0.016 |

| Children under 2 years old n (%) | 80 (55.2) | 15 (35.7) | 95 (50.8) | 0.026 |

| Sex: male n (%) | 78 (53.8) | 30 (71.4) | 108 (57.8) | 0.041 |

| Ethnicity: Brazilian pardo n (%) | 68 (46.9) | 10 (23.8) | 78 (41.7) | 0.007 |

| Pediatric complex chronic conditions n (%) | 76 (52.4) | 32 (76.2) | 108 (57.8) | 0.006 |

| Comorbitidies | ||||

| Neurologic and neuromuscular diseases | 15 (19.7) | 16 (50) | 31(28.7) | 0.003 |

| Respiratory diseases | 7 (9.2) | 8 (25) | 15 (13.9) | 0.038 |

| Prematurity and neonatal diseases | 6 (7.9) | 9 (28.1) | 15 (13.9) | 0.008 |

| Time from exposure to symptom onset in days, median (IQR) | 6 (5–9) | 8 (5–15) | 7 (5–9) | 0.027 |

| Duration of fever in days, median (IQR) | 1 (1–4) | 1 (1–4) | 1 (1–4) | 0.424 |

| SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed tests** n (%) | ||||

| RT-PCR | 66/164 (40.2) | 12/55 (21.8) | 78/219 (35.6) | 0.013 |

| Antigen test | 79/164 (48.2) | 30/55 (54.5) | 109/219 (49.8) | 0.41 |

| IgM test | 11/164 (6.7) | 2/55(3.6) | 13/219 (5.9) | 0.525 |

| BMI-for-age Z-scores > 5 years old: Moderately underweight n (%) | 6 (4.1) | 10 (23.8) | 16 (8.6) | 0.006 |

| BMI-for-age Z-scores < 5 years old: Moderately underweight n (%) | 24 (16.6) | 8 (19.0) | 32 (17.1) | 0.899 |

| Clinical | ||||

| Lymphadenopathy n (%) | 30 (20.7) | 6 (14.3) | 36 (19.3) | 0.387 |

| Dyspnea n (%) | 102 (70.3) | 42 (100) | 144 (77.0) | < 0.001 |

| Dyspnea classification n (%) | 65 (63.7) | 42 (100) | 107 (74.3) | < 0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms n (%) | 55 (37.9) | 13 (31.0) | 68 (36.4) | 0.406 |

| Pneumonia n (%) | 65 (44.8) | 33 (78.6) | 98 (52.4) | < 0.001 |

| Exanthema n (%) | 18 (12.4) | 5 (11.9) | 23 (12.3) | 1.000 |

| Cardiogenic Shock n (%) | 28 (54.9) | 23 (54.8) | 51 (54.8) | 1.000 |

| VIS median (IQR) | 0 (0–24) | 120 (98–154) | 0 (0–95) | < 0.001 |

| Oxygen therapy modalities n (%) | ||||

| Oxygen low interfaces | 77 (53.1) | 0 (0) | 77 (41.2) | < 0.001 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 61 (42.1) | 42 (100) | 103 (55.1) | < 0.001 |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 7 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 7 (3.7) | 0.209 |

| Ventilator weaning success at first attempt n (%) | 47 (77.0) | 18 (42.9) | 65 (63.1) | 0.269 |

| Tracheostomy tube use n (%) | 8 (13.1) | 3 (7.1) | 11 (10.7) | 0.712 |

| ADRS n (%) | 38 (26.2) | 35 (83.3) | 73 (39.0) | < 0.001 |

| Severe ARDS n (%) | 8 (5.5) | 15 (35.7) | 23 (12.3) | 0.076 |

| MOD > 2 organ involvement n (%) | 26 (17.9) | 14 (33.3) | 40 (21.4) | 0.036 |

| Renal replacement therapy n (%) | 13 (9.0) | 6 (14.3) | 19 (10.2) | 0.383 |

| KDIGO,stage 1, n (%) | 60 (41.4) | 26 (61.9) | 86 (46.0) | 0.025 |

| Treatment n (%) | ||||

| Low molecular weight heparin therapy | 51 (35.2) | 9 (21.4) | 60 (32.1) | 0.132 |

| Methylprednisolone pulse therapy | 2 (1.4) | 4 (9.5) | 6 (3.2) | 0.023 |

| Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy | 19 (13.1) | 6 (14.3) | 25 (13.4) | 1.000 |

| Outcomes median (IQR) | ||||

| Length of stay in hospital, in days | 13 (9–18) | 9 (5–15) | 12 (8–17) | 1.000 |

| Length of stay at PICU, in days | 3 (2–6) | 6 (4–11) | 4 (2–7) | < 0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation time, in days | 4 (2–5) | 6 (4–10) | 4 (2–7) | < 0.001 |

| Ventilator free days at 28th | 24 (23–26) | 0 (0–1) | 21 (0–24) | < 0.001 |

| PRISMIV% | 3 (2–8) | 8.6 (4–13) | 4 (2–9) | < 0.001 |

| PELOD-2 | 6 (3–12) | 11 (2.8–15) | 6 (3–12) | 0.036 |

| Ventilatory settings and respiratory mechanics median (IQR) Day 1 | ||||

| Tidal volume in ml/kg | 7 .1(6.2–8.3) | 7.3 (6.1–8.2) | 7.1 (6.1–8.2) | 0.417 |

| Respiratory rate breaths/min | 20 (14–28) | 25 (24–30) | 25 (17–30) | 0.064 |

| Peep-peak paw in cmH2O | 16 (15–18) | 19 (17–22) | 17 (15–19) | 0.033 |

| Driving pressure in cmH2O | 10 (7–13) | 13 (8–15) | 11 (7–14) | 0.015 |

| Compliance respiratory system in mL/cmH2O/kg | 0.88 (0.62–1.16) | 0.78 (0.51–1.01) | 0.66 (0.58–0.95) | 0.035 |

| Ventilatory ratioa | 0.61 (0.5–0.84) | 0.85 (0.64–1.12) | 0.79 (0.59–1.08) | 0.002 |

| Laboratorial features median (IQR) Day 1 | ||||

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 287 (202–431) | 160 (108–258) | 268 (154–402) | < 0.001 |

| pO2 (mmHg) | 137 (83.4–183) | 87.1 (73–124.3) | 124.3 (75.7–180) | 0.002 |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 35.2 (30.2–44) | 36.4 (32.1–43.8) | 33.8 (31–42.3) | 0.036 |

| Sodium bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 21 (18.2–25.5) | 18.1 (15.4–21) | 20 (16.8–24.5) | 0.001 |

| Anion gap (mmol/L) | 13.3 (9.3–19.9) | 18.2 (14.4–20.5) | 14.2 (9.9–19.9) | 0.007 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 1.7 (1.1–2.6) | 1.8 (1.1–2.9) | 1.7 (1.1–2.6) | 0.821 |

| Total leukocyte count/mm3 | 12,495 (9000–18,260) | 8957 (6460–11,065) | 11,400 (7569–17,1010) | < 0.001 |

| Lymphocytes count/mm3 | 2780 (1518–4867) | 1113 (855–1841) | 2432 (1113–4554) | < 0.001 |

| INR | 1.21 (1.02–1.56) | 1.5 (1.2–1.65) | 1.25 (1.03–1.58) | 0.011 |

| d-Dimer (ng/dL) | 609 (330–1,940) | 516 (289–1,192) | 575 (312–1,813) | 0.05 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 125 (102–174) | 109 (92–134) | 120 (100–173) | 0.023 |

| C-reactive protein(mg/dL) | 6 (2–15.4) | 2.3 (0.6 -9.4) | 6 (1.3–14.1) | 0.006 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 12 (10–16) | 17 (10–35) | 14 (10–17) | < 0.001 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 230 (142–452) | 255 (224–385) | 241 (144–452) | 0.389 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 22 (14–43) | 19 (10–45) | 22 (14–44) | 0.404 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0,4 (0.2–0.6) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.4 (0.2–0.6) | 0.05 |

| AST (IU/L) | 39 (24–55) | 32 (13–60) | 37 (22–56) | 0.255 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 33 (21–38) | 35 (31–39) | 34 (21–39) | 0.126 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.8 (2.5–3.4) | 2.6 (2.1–3.1) | 2.8 (2.3–3.4) | 0.037 |

| Troponin I (ng/L), | 0.07 (0.012–0.189) | 0.1 (0.031–0.188) | 0.094 (0.02–0.189) | 0.685 |

| Ventilatory settings and respiratory mechanics median (IQR) Day 2 | ||||

| Tidal volume in ml/kg | 5.7 (4.1–7.4) | 8.1 (6.6–9.8) | 6.6 (4.1–8.2) | 0.006 |

| Respiratory rate breaths/min | 22 (20–25) | 24 (23–28) | 24 (21–27) | 0.285 |

| Peep-peak paw in cmH2O | 15 (14–21) | 20 (19–23) | 19 (15–21) | 0.055 |

| Driving pressure in cmH2O | 8 (6–9) | 10 (8–12) | 8 (5–11) | < 0.001 |

| Compliance respiratory system in mL/cmH2O/kg | 0.81 (0.6–1.04) | 0.6 (0.41–0.72) | 0.88 (0.57–1.12) | 0.001 |

| Ventilatory ratioa | 0.81 (0.61–0.93) | 1.27 (0.77–1.73) | 0.85 (0.66–1.28) | 0.001 |

| Laboratorial features median (IQR) Day 2 | ||||

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 289 (187–469) | 206 (119–340) | 274 (186–417) | 0.018 |

| pO2 (mmHg) | 99 (62–141) | 108 (71–139) | 103 (63–141) | 0.681 |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 36 (30–42) | 35 (27–42) | 36 (29–42) | 0.278 |

| Sodium bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 22.3 (18–24.8) | 20.1 (15.5–22.4) | 21.6 (17.7–24.6) | 0.189 |

| Anion gap (mmol/L) | 14.2 (9.1–19.4) | 15.4 (12.1–20.7) | 14.2 (9.7–19.7) | 0.256 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 1.5 (1–2.1) | 1.3 (1–2.3) | 1.4 (1–2.2) | 0.365 |

| Total leukocyte count/mm3 | 11,821 (8017–16,161) | 11,649 (8069–18,327) | 11,719 (8048–16,423) | 0.267 |

| Lymphocytes count/mm3 | 2710 (1122–4402) | 2000 (1092–3122) | 2640 (11,122–4149) | 0.039 |

| INR | 1.26 (1.16–1.5) | 1.48 (1.21–1.91) | 1.27 (1.16–1.58) | 0.002 |

| d-Dimer (ng/dL) | 510 (258–1371 | 1782 (483–5,178) | 546 (258–1783) | 0.154 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 131 (93–269) | 87 (64–270) | 120 (86–269) | 0.246 |

| C-reactive protein(mg/dL) | 6 (1.3–11) | 6.3 (0.8–13.5) | 6 (1.1–12) | 0.67 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 15 (10–18) | 44 (39–77) | 15 (10–22) | < 0.001 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 199 (128–502) | 372 (219–600) | 221 (128–504) | 0.473 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 22 (11–43) | 26 (9–85) | 22 (11–44) | 0.263 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0.804 |

| AST (IU/L) | 51 (36–94) | 52 (36–75) | 51.5 (36–84) | 0.444 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 42 (21–65) | 45 (26–50) | 42 (23–65) | 0.848 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3 (2.6–3.6) | 2.9 (2.5–4) | 3 (2.6–3.8) | 0.447 |

| Troponin I (ng/L), | 0.046 (0.011–0.33) | 0.048 (0.01–0.1) | 0.47 (0.01–0.31) | 0.013 |

BMI, body mass index. VIS, vasoactive-inotropic score. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome. MOD, Multiple organ dysfunction. KDIGO, Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome classification system. Peep, Positive end-expiratory pressure. Paw, peak airway pressure. *The bold numbers refer to two-sided p value using Bonferroni correction (p < 0.001). Mechanical ventilation time, oxygen low interfaces, dyspnea were not used to avoid multicollinearity in the regression model. **All patients admitted to units underwent the test before admission and were positive for antigen test and/or RT-PCR test the patients who had MIS-C criteria we added serological test. aVentilatory ratio was defined as (minute ventilation × PaCO2)/(PBW × 100 × 37.5)21 , because the predicted minute ventilation used in adults (100 mL/kg/min predicted body weight) does not apply over the age range of children and young adults, a pediatric predicted minute ventilation was used22.

Univariate and multivariate analysis

After Cox regression multivariate analysis in the MIS-C group, the main factor associated with in-hospital mortality was platelets lower than 100,000 cel/mm3. Every decrease of 15,000 cel/mm3 platelets increases the risk by 10% (HR1.1, CI95%, 1.0–1.2, p < 0.001) and 40% (HR 1.4, CI95%, 1.1–1.6, p = 0.01) in adjusted models 1 and 2, respectively. In the severe COVID-19 group, VIS (each 5 change increase 30%, 3% and 5% for crude model, adjusted model1 and adjusted model 2, respectively) and ARDS (crude model HR 6.9, CI95%, 1.4–34.5, p = 0.018; adjusted model 1 and 2, HR, 6.4, CI95%, 1.31–31.5, p = 0.022 and HR, 13, CI95%, 2–83, p = 0.007, respectively) stood out as the main factors associated with in-hospital mortality, in models, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Cox regression analysis for associated factors to mortality at admission, according to the study groups.

| MIS-C group | Crude model | Adjusted model 1* | Adjusted model 2* | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||||||||||

| Variable | HR | CI 95% | p value | HR | CI 95% | p value | HR | CI 95% | p value | HR | CI 95% | p value | HR | CI 95% | p value | HR | CI 95% | p value |

| Troponin I (ng/L) for 0.01 ng/L change for each | 1.01 | 0.98–1.04 | 0.516 | – | – | – | 1.0 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.98 | – | – | – | 1.01 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.708 | – | – | – |

| Platelets for 15,000 cel/mm3 change for each | 1.02 | 0.99–1.2 | 0.001 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.03 | 0.007 | 1.11 | 1.0–1.22 | < 0.001 | 1.12 | 1.02–1.23 | 0.010 | 1.3 | 1.1–1.5 | 0.001 | 1.4 | 1.1–1.6 | 0.010 |

| ESR mm/h | 1.09 | 1.05–1.2 | < 0.001 | 1.3 | 1.03–1.5 | 0.020 | 1.1 | 1.06–1.17 | < 0.001 | 1.2 | 0.99–1.5 | 0.057 | 1.2 | 1.1–1.4 | < 0.001 | 1.2 | 1.01–1.5 | 0.04 |

| Severe COVID-19 group | Crude model | Adjusted model 1* | Adjusted model 2* | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||||||||||

| Variable | HR | CI 95% | p value | HR | CI 95% | p value | HR | CI 95% | p value | HR | CI 95% | p value | HR | CI 95% | p value | HR | CI 95% | p value |

| Pneumonia | 3.7 | 1.8–7.8 | < 0.001 | 2.5 | 0.60–11.5 | 0.233 | 0.7 | 0.06–7.5 | 0.761 | – | – | – | 1.61 | 0.2–15 | 0.679 | – | – | – |

| ARDS | 10.4 | 4.6–23.4 | < 0.001 | 6.9 | 1.4–34.5 | 0.018 | 38.4 | 8.6–73.2 | < 0.001 | 6.4 | 1.31–31.5 | 0.022 | 37.1 | 7.8–76 | < 0.001 | 13 | 2–83 | 0.007 |

| VIS for 5 change each | 1.03 | 1.01–1.04 | < 0.001 | 1.3 | 1.2–1.4 | < 0.001 | 1.02 | 1.01–1.05 | < 0.001 | 1.03 | 1.02–1.04 | < 0.001 | 1.03 | 1.02–1.04 | < 0.001 | 1.05 | 1.03–1.06 | < 0.001 |

| Leukocyte/mm3 for 1000 cel/mm3 change each | 1.01 | 0.98–1.02 | 0.238 | – | – | – | 1.02 | 1.01–1.03 | 0.179 | – | – | – | 0.98 | 0.95–1.01 | 0.505 | – | – | – |

| ESR mm/h for 5 mm/h change each | 1.08 | 1.04–1.11 | < 0.001 | 1.05 | 0.98–1.12 | 0.214 | 1.07 | 1.04–1.11 | < 0.001 | 1.06 | 1.0–1.2 | 0.037 | 1.08 | 1.05–1.2 | < 0.001 | 1.06 | 1–1.4 | 0.073 |

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome. VIS, Vasoactive-inotropic score. PIP, peak inspiratory pressure. ESR, Erythrocyte sedimentation rate. PRISMIV%, pediatric risk of mortality score version IV. *Adjusted model 1 and 2 for PRISMIV score > 9 and age under one year old/ presence of comorbidity, respectively. Lymphadenopathy, Dyspnea, Oxygen low interfaces, Invasive mechanical ventilation, Length of stay at PICU, in days, Mechanical ventilation time, in days, Lymphocytes count/mm3, Ventilator free days at 28th, and PaO2/FiO2 ratio did not show the proportionality of risks in the Kaplan Meyer curves in the severe COVID-19 group, while in the MIS-C group the variables: Peak inspiratory pressure, tidal volume, driving pressure, KDIGO stage 1, ARDS, VIS, Invasive mechanical ventilation, Ventilator weaning success at first attempt, Ventilator free days at 28th, Mechanical ventilation time, Oxygen inspired fraction, Positive end-expiratory pressure, PaO2/FiO2 ratio, also did not show the proportionality of risks in the Kaplan Meyer curves or high colinearity or worst result of fractional polynomials method.

The bold number refers to the two-sided p value (p < 0.05).

Survival analysis

Critically ill patients with severe COVID-19 and MIS-C from the Brazilian Amazon presented a median time of 12 days of hospitalization until death.

MIS-C group

After a median follow-up of 162 days (IQR, 156–168, range, 3–202), there were 17 deaths (24.3%) in the critical MIS-C group. The median time for death was 7 days (IQR, 4–13, range 2–40). The Kaplan–Meier survival plots for the statistical general mortality and risk factors in the critical MIS-C group are presented in Supplementary Information 1-Figure (A-B).

Severe COVID-19 group

In the severe COVID-19 group the general mean survival time was 240.7 days (SD 9.04, CI95%, 222.9–258.4) with a median follow-up time of 161 days (IQR, 153–169, range, 2–307). There were 42 (22.5%) deaths and the median time until death was 11 days (IQR, 7–29, range, 3–55). The Kaplan–Meier survival plots for the statistical general mortality and risk factors in the severe COVID-19 patients are presented in Supplementary Information 2-Figure (A-D). Other data information about each patient is available in Supplementary Information 3-Table 1.

Discussion

Our key findings suggest a higher mortality rate for COVID-19 (22.5%) and MIS-C (21.5%) patients compared to other pediatric studies from high-income countries (range 1–10%)1–3, 5–7, 23–25. It is worth noting that most of these studies also included non-critical patients, which makes an adequate comparison difficult, as our sample consisted only of critically ill patients. The mortality rate was high and was characterized by a significant disparity among the three PICUs. This could be due to the inequality in the number of patients attended in the three units.

The main factors associated with in-hospital mortality in this study were the presence of ARDS and cardiovascular dysfunction in the COVID-19 group, while in the MIS-C group an increase in inflammatory markers and thrombocytopenia stood out. These findings are associated with the greater risk factors for PICU admission among the pediatric population with COVID-19/MIS-C, as reported in previous studies1,3, 5, 6, 20, 24, 26–29, however, their presence would not be able to justify mortality exclusively, since in these other studies, the mortality rate was lower than that found in our study.

Based on this we hypothesize that our findings may arise from a complex interaction that emerged between social and clinical risk factors for fatal outcomes. Several studies30–32 have shown that the interactions between ethnicity, social inequality, and/or health access disparity, are strongly associated with the unfavorable outcomes in COVID-19. Among social factors, adult patients29,30 and children/adolescents33,31 from the poorest regions of the country, including those of Indigenous/Pardo Brazilian ethnicity, had a significantly higher risk of poor outcomes.

This study revealed a shorter time to death compared to other surveys. To the best of our knowledge, there are currently no reports regarding the time to death among the pediatric population. However, an adult cohort from a developed country revealed a longer time to death of between nine and 12 days34, which is similar to our findings. Most patients were severely ill and died during their initial days in hospital. As revealed in the ventilatory and laboratorial parameters on the first day of hospitalization, the patients arrived severely ill at the hospital, which could have been a contributor to the short time to death. The vast geographic region and scarcity of specialized centers may have contributed to longer time to access the health system, and consequently, the lower survival time.

Our findings indicate the presence of unfavorable outcomes in our cohort. We hypothesize that numerous biological factors could be determinants of this scenario, such as, high rate of comorbidity, ethnicity and genetic factors, presence of malnutrition, high severity of cases, among others. In addition, the influence of socioeconomic inequities, may coexist as confounding variables, however we were not able to provide this data. Health disparities favor illness, and consequently, worse outcomes for affected individuals or groups, which are reinforced by health inequities. The concept of structural vulnerability seeks to integrate all factors outside the clinical environment to more holistically contextualize the barriers and facilitators that individuals or groups may face in accessing healthcare, adhering to treatment protocols, and achieving better health outcomes. The factors involved in health disparities differ depending on where these disparities occur throughout the course of acute critical illness, and a clear understanding of where these disparities exist is critical to designing future interventions to improve outcomes for all patients35,36.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, there was selection bias in our cohort, since only patients with critical COVID-19/MIS-C and patients from low socio-economic status were included, although a specific socio-economic questionnaire was not performed. In addition to this, although the management of patients was based on Health Ministry recommendations for COVID-19/MIS-C, a uniform management protocol was not applied. It is important to report that the mortality rate was higher in 2020 than in 2021 in MIS-C and in severe COVID-19 groups and has progressively reduced: total of 43 deaths in 2020 (13 [30.2%] and 30 [69.8%] respectively), 7 deaths in 2021 (4 [57.2%] and 3 [42.8%], respectively), and 6 deaths in 2022 (0 [0%]) and 6 [100%], respectively), and finally 3 deaths in 2023 (0 [0%] and 3 [100%], respectively). There was also a change in the ventilatory management of patients with COVID-19 in 2021, based on evidence extrapolated from adults, with less frequent use of alveolar recruitment, and monitoring with bedside electrical impedance tomography to choose the best PEEP. In the case of MIS-C, the implementation of vasoactive support and immunomodulatory therapy was earlier.

An important strength of this study is that it contributes to better knowledge regarding risk factors for severe illness and mortality, which will allow the best prognosis for patients. Furthermore, our study is unique in terms of the large sample size of critical patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, allowing good quality analysis. Another strength is the strict data collection and analysis, which was triple checked, in order to minimize mistakes. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest sample from Brazil which comprehensively describes factors associated to in-hospital mortality in children with severe COVID-19/MIS-C.

In our study the risk of death at any time during follow-up was clearly higher for patients with ARDS and higher levels of VIS in the severe COVID-19 group, and higher ESR and thrombocytopenia for those who presented with MIS-C. It is urgent that we increase surveillance regarding critical forms of pediatric COVID-19 in poor regions. Further data is required to manage children with critical COVID-19/MIS-C, especially in limited-resource regions to provide high quality care for those patients with these life-threatening illnesses.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We are glad to thank Fundação Santa Casa de Misericórdia do Pará for giving us the chance to conduct this research. Our special thanks go to all the children, parents, and participating PICU.

Abbreviations

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CPK-MB

Creatine phosphokinase MB fraction

- ESR

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- IMV

Invasive mechanical ventilation

- KDIGO

Kidney disease improving global outcome classification system

- MIS-C

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children

- MOD

Multiple organ dysfunction

- OI

Oxygenation index

- PALICC

Pediatric acute lung injury consensus conference

- PICU

Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

- SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2

- VIS

Vasoactive inotropic-score

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

E.C.F.F., M.C.M., M.T.T., and G.C. designed research, conceptualized the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. M.C.A.J., M.L.F.M.F.M., L.M.P.P.N., S.C.D.S., M.J.C.P.J. and P.B.C. assisted with the concept, interpretation of data and reviewed the manuscript. K.M.M.M.F., L.F.Q.A., L.G.D., M.M.M.M., M.J.D.S., K.O.H., S.M.P.M., G.M.G., G.C.L.P., R.D.F.P.C., C.T.C.S., G.L., S.B.S., D.C.A.P., A.P.S.P., B.C.G.D., A.H.O.P., M.C.B.A., R.B.B., M.R.C.L., K.F.S.A., A.G.C. and A.M.B.S. conducted data collection, interpretation of data and edited the manuscript. M.T.T. and M.C.M. have contributed equally to this work as co-senior authorship. All authors have read, reviewed, and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

Due to the privacy of patients, the data related to patients cannot be available for public access but can be obtained from the corresponding author (emmersonfariasbrandynew@gmail.com) on reasonable request approved by the institutional review board of all enrolled centers.

Competing interests

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form. All the authors have non-financial nor conflict of interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Maria Teresa Terreri and Marta C. Monteiro.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-55065-x.

References

- 1.Marks KJ, Whitaker M, Anglin O, et al. COVID-NET Surveillance Team. Hospitalizations of children and adolescents with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19-COVID-NET, 14 States, July 2021–January 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022;71(7):271–278. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7107e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez-Dambrauskas S, Vasquez-Hoyos P, Camporesi A, et al. Critical Coronavirus and Kids Epidemiological (CAKE) Study Investigators. Paediatric critical COVID-19 and mortality in a multinational prospective cohort. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2022;12:100272. doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsankov BK, Allaire JM, Irvine MA, et al. Severe COVID-19 infection and pediatric comorbidities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;103:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pereira MFB, Litvinov N, Farhat SCL, et al. Pediatric COVID HC-FMUSP Study Group, Severe clinical spectrum with high mortality in pediatric patients with COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Clinics. 2020;75:e2209. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2020/e2209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhalala US, Gist KM, Tripathi S, et al. Society of critical care medicine discovery viral infection and respiratory illness universal study (VIRUS): COVID-19 Registry Investigator Group. Characterization and outcomes of hospitalized children with coronavirus disease 2019: A report from a multicenter, viral infection and respiratory illness universal study (coronavirus disease 2019) registry. Crit. Care Med. 2022;50(1):e40–e51. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldstein LR, Tenforde MW, Friedman KG, et al. Overcoming COVID-19 Investigators. Characteristics and outcomes of US children and adolescents with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) compared with severe acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(11):1074–1087. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alfraij A, Bin Alamir AA, Al-Otaibi AM, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in critically ill pediatric patients admitted to the intensive care unit: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. J. Infect. Public Health. 2021;14(2):193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Funai T, et al. The pediatric risk of mortality score: Update 2015. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2016;17(1):2–9. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leteurtre S, Duhamel A, Salleron J, et al. PELOD-2: An update of the PEdiatric logistic organ dysfunction score. Crit. Care Med. 2013;41(7):1761–1773. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a2bbd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bembea MM, Agus M, Akcan-Arikan A, et al. Pediatric organ dysfunction information update mandate (PODIUM) contemporary organ dysfunction criteria: Executive summary. Pediatrics. 2022;149(1 Suppl 1):S1–S12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052888B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. [homepage on the Internet]. 19; (WHO, 2020). Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and adolescents temporally related to COVID. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/multisystem-inflammatory-syndrome-in-children-and-adolescents-with-covid-19 (Accessed 7 Sept 2022).

- 12.Weiss SL, Peters MJ, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign international guidelines for the management of septic shock and sepsis-associated organ dysfunction in children. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2020;21(2):e52–e106. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McIntosh AM, Tong S, Deakyne SJ, et al. Validation of the vasoactive-inotropic score in pediatric sepsis. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2017;18(8):750–757. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kneyber MCJ, de Luca D, Calderini E, et al. Section Respiratory Failure of the European Society for Paediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care. Recommendations for mechanical ventilation of critically ill children from the Paediatric Mechanical Ventilation Consensus Conference (PEMVECC) Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(12):1764–1780. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4920-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emeriaud G, López-Fernández YM, Iyer NP, et al. Second Pediatric Acute Lung Injury Consensus Conference (PALICC-2) Group on behalf of the Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators (PALISI) Network. Executive summary of the second international guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome (PALICC-2) Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2023;24(2):143–168. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000003147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levey A, Eckardt K, Dorman N, et al. Nomenclature for kidney function and disease: Report of a kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) consensus conference. Kidney Int. 2020;97:1117–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.BRASIL. MINSITÉRIO DA SAÚDE. Secretária de Vigilância em Saúde. Boletim Epidemiológico Especial. Doença pelo Novo Coronavírus – COVID-19, nº 43 - Boletim COE Coronavírus. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/boletins/epidemiologicos/covid-19 (Acessado em 26 set. 2023).

- 18.BRASIL. MINSITÉRIO DA SAÚDE. Secretária de Vigilância em Saúde. Boletim Epidemiológico Especial. Doença pelo Novo Coronavírus – COVID-19, nº 92 - Boletim COE Coronavírus. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/boletins/epidemiologicos/covid-19 (Acessado em 26 set. 2023).

- 19.BRASIL. MINSITÉRIO DA SAÚDE. Secretária de Vigilância em Saúde. Boletim Epidemiológico Especial. Doença pelo Novo Coronavírus – COVID-19, nº 146 - Boletim COE Coronavírus. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/boletins/epidemiologicos/covid-19 (Acessado em 26 set. 2023).

- 20.BRASIL. MINSITÉRIO DA SAÚDE. Secretária de Vigilância em Saúde. Boletim Epidemiológico Especial. Doença pelo Novo Coronavírus – COVID-19, nº 151 - Boletim COE Coronavírus. Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/centrais-de-conteudo/publicacoes/boletins/epidemiologicos/covid-19 (Acessado em 26 set. 2023).

- 21.Sinha P, Calfee CS, Beitler JR, et al. Physiologic analysis and clinical performance of the ventilatory ratio in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019;199(3):333–341. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201804-0692OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhalla AK, Dong J, Klein MJ, et al. The association between ventilatory ratio and mortality in children and young adults. Respir. Care. 2021;66(2):205–212. doi: 10.4187/respcare.07937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shekerdemian, L.S., Mahmood, N.R., Wolfe, K.K., et al. Characteristics and outcomes of children with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection admitted to US and Canadian pediatric intensive care units. JAMA Pediatr. 174:86873. 9 (2020). doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Swann OV, Holden KA, Turtle L, et al. Clinical characteristics of children and young people admitted to hospital with covid-19 in United Kingdom: prospective multicentre observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;370:m3249. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chao JY, Derespina KR, Herold BC, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized and critically Ill children and adolescents with coronavirus disease 2019 at a tertiary care medical center in New York City. J. Pediatr. 2020;223:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliveira EA, Colosimo EA, Simões E, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for death among hospitalised children and adolescents with COVID-19 in Brazil: An analysis of a nationwide database. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health. 2021;5(8):559–568. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00134-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mamishi S, Pourakbari B, Mehdizadeh M, et al. Children with SARS-CoV-2 infection during the novel coronaviral disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Iran: An alarming concern for severity and mortality of the disease. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022;22(1):382. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07200-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kapoor D, Kumar V, Pemde H, et al. Impact of comorbidities on outcome in children with COVID-19 at a Tertiary Care Pediatric Hospital. Indian Pediatr. 2021;58(6):572–575. doi: 10.1007/s13312-021-2244-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao S, Gavali V, Prabhu SS, et al. Outcome of children admitted with SARS-CoV-2 infection: Experiences from a Pediatric Public Hospital. Indian Pediatr. 2021;58(4):358–362. doi: 10.1007/s13312-021-2196-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mackey K, Ayers CK, Kondo KK, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19-related infections, hospitalizations, and deaths: A systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021;174:362–373. doi: 10.7326/M20-6306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baqui P, Bica I, Marra V, et al. Ethnic and regional variations in hospital mortality from COVID-19 in Brazil: A cross-sectional observational study. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8:e1018–e1026. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30285-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mujica OJ, Victora CG. Social vulnerability as a risk factor for death due to severe paediatric COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health. 2021;5(8):533–535. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)0016-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.López-Medina E, Camacho-Moreno G, Brizuela ME, et al. Factors associated with hospitalization or intensive care admission in children with COVID-19 in Latin America. Front. Pediatr. 2022;10:868297. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.868297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roelens M, Martin A, Friker B, et al. Evolution of COVID-19 mortality over time: results from the Swiss hospital surveillance system (CH-SUR) Swiss Med. Wkly. 2021;151:w30105. doi: 10.4414/smw.2021.w30105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howard AF, Li H, Lynch K, Haljan G. Health equity: A priority for critical illness survivorship research. Crit. Care Explor. 2022;4(10):e0783. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soto GJ, Martin GS, Gong MN. Healthcare disparities in critical illness. Crit. Care Med. 2013;41(12):2784–2793. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a84a43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Due to the privacy of patients, the data related to patients cannot be available for public access but can be obtained from the corresponding author (emmersonfariasbrandynew@gmail.com) on reasonable request approved by the institutional review board of all enrolled centers.