Graphical abstract

Keywords: Silkworm, Model organism, Particle size-dependent effects, Metabolome, Gut microbiome, Transcriptome

Highlights

-

•

Environmental concentrations of PS-MNPs increased body weight without affecting survivorship.

-

•

Exposures induced significant alterations in host metabolome, microbiome, and transcriptome.

-

•

Gut metabolites were correlated with the microbiome.

-

•

The observed biomarkers’ responses were particle size-dependent i.e., PS-S > PS-M > PS-L.

-

•

Metabolic disorder and microbiome dysbiosis are the main mechanisms of the observed phenotype.

Abstract

Introduction

Micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) are emerging environmental pollutants that have raised serious concerns about their potential impact on ecosystem and organism health. Despite increasing efforts to investigate the impacts of micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) on biota little is known about their potential impacts on terrestrial organisms, especially insects, at environmental concentrations.

Objectives

To address this gap, we used an insect model, silkworm Bombyx mori to examine the potential long-term impacts of different sizes of polystyrene (PS) MNPs at environmentally realistic concentrations (0.25 to 1.0 μg/mL).

Methods

After exposure to PS-MNPs over most of the larval lifetime (from second to last instar), the endpoints were examined by an integrated physiological (growth and survival) and multiomics approach (metabolomics, 16S rRNA, and transcriptomics).

Results

Our results indicated that dietary exposures to PS-MNPs had no lethal effect on survivorship, but interestingly, increased host body weight. Multiomics analysis revealed that PS-MNPs exposure significantly altered multiple pathways, particularly lipid metabolism, leading to enriched energy reserves. Furthermore, the exposure changed the structure and composition of the gut microbiome and increased the abundance of gut bacteria Acinetobacter and Enterococcus. Notably, the predicted functional profiles and metabolite expressions were significantly correlated with bacterial abundance. Importantly, these observed effects were particle size-dependent and were ranked as PS-S (91.92 nm) > PS-M (5.69 µm) > PS-L (9.7 µm).

Conclusion

Overall, PS-MNPs at environmentally realistic concentrations exerted stimulatory effects on energy metabolism that subsequently enhanced body weight in silkworms, suggesting that chronic PS-MNPs exposure might trigger weight gain in animals and humans by influencing host energy and microbiota homeostasis.

Introduction

Applications of plastic materials in the modern world have been incorporated in almost every field including automobile, textile, medicine, food, agriculture, and construction industries [1], [2]. Due to their numerous social and economic benefits, plastic production has increased tremendously, reaching 390.7 million metric tons in 2021, which represents a 200-fold increase since the first production in 1907 [2], [3]. As a result of this exponential increase and inadequate management and disposal, plastic pollution has become a global concern to the environment and a threat to biodiversity, indicating the need for risk assessment and regulatory standards for long-term policy management of plastics [4], [5].

Particularly, micro- (<5 mm) and nanoplastics (<100 nm) (hereafter known as MNPs) are extremely small bits of plastic fragments that have aroused considerable interest and debate as emerging environmental pollutants in recent years [4], [5]. According to their source, MNPs are either manufactured to be that size (known as primary MNPs) or resulted from the degradation (biodegradation, photooxidation, hydrolysis, mechanical abrasion, etc.) of larger plastic debris (known as secondary MNPs) [6], [7]. MNPs are widely distributed in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems and their pollution is predicted to increase which will continue to pose greater risks to biota and ecosystem processes in various environments [1], [4], [8], [9]. Given the ubiquity of MNPs, they are likely to be ingested by organisms through contaminated food, inhalation, or dermal contact from various exposure sources such as food, dust, cosmetics, medicine, clothing, etc. [1], [4], [10]. Upon ingestion, these particles can be accumulated in tissues and interact with biological molecules which could affect physiological homeostasis and induce toxicity [7], [11]. Polymer features including size, shape, charge, density, agglomeration rate, and surface coating affect their mobility, behavior, biological fate, and toxicity [12], [13], [14]. Generally, the smaller size particles (NPs) can cause greater impacts due to a larger surface/volume ratio and higher cellular internalization than the larger sizes (MPs) [14], [15]. Despite a massively increasing research that has focused on the effects of MNPs on organisms, most of these studies have used unrealistically higher concentrations, and the debate of whether field-realistic concentrations of these particles may pose a hazard and risk continues [4], [16], [17]. MNPs-mediated negative or toxic effects in organisms were observed when the contaminants dose (usually higher than the environmental concentration) exceeded the toxicological threshold of the organisms [4]. On the other hand, low concentrations that are more likely to occur in the environment may impose little or negligible effects, or may even induce positive effects [1], [4], [17]. However, we only have a nascent understanding of chronic low-dose exposures and require further investigations to uncover the ecological implications of the MNPs at environmental concentrations to individual organisms in all environments. Fortunately, the adoption of a high-throughput multiomics approach (metabolomics, genomics, transcriptomics, etc.) could uncover deeper and more subtle effects as well as adverse outcome pathways.

A growing number of studies have investigated the effects of MNPs on physiology (growth and development, survival, reproduction), histology (injury to internal tissues), biochemistry (metabolites), molecular biology (gene expression and metabolic pathway), and gut microbiome of various organisms [11], [15], [16], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]. However, the potential impacts of MNPs on terrestrial ecosystems, particularly on the most abundant and ecologically important group of animals, insects, are still largely unknown. As insects provide numerous ecosystem services, it is imperative that we investigate the potential long-term effects of MNPs on this diverse and abundant fauna.

Silkworm Bombyx mori is a special economic animal and a well-studied insect model [25], [26]. Given its sensitivity to environmental contaminants and weak resistance to diseases, the silkworm is growing in popularity as a model organism in the ecotoxicology [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]. In addition, their clear genetic background, moderate body size, short life cycle, rapid reproduction, as well as easy handling make them overcome some of the disadvantages such as the long generation time, high maintenance cost, and growing ethical concerns of the vertebrate models [30], [31]. Given the widespread occurrence of MNPs in terrestrial environments, it is essential to assess their impact on biota. The use of silkworms as a model organism is particularly relevant due to their sensitivity to environmental contaminants and their status as a representative of the insects, which are a vital component of the ecosystem. In our previous study, we observed sublethal effects on silkworms when exposed to a relatively high concentration of polystyrene micro- and nanoplastics (PS-MNPs) [29]. Therefore, based on the literature reporting negligible or positive effects of MNPs at environmental concentrations, we hypothesized that the long-term exposures of field-realistic doses of PS-MNPs would have no serious adverse effects, however, they may interfere with the host physiological homeostasis. To test this hypothesis, silkworm larvae were exposed to three different sizes of PS-MNPs at environmentally relevant concentrations. We used multiomics approach, including metabolomics, 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing, and transcriptomics, to investigate the effects of PS-MNPs on host physiology and metabolic functions, as well as the underlying mechanisms. The specific objectives of this study were to evaluate how long-term exposure to three different sizes of PS-MNPs affects host growth and survivorship, gut metabolites profiles, gut microbiota, transcript profiles of critical genes, and the associations between changed metabolites and the gut microbiome of silkworms. We also examined the differences in the potential impacts of different size particles on the said endpoints. Overall, the findings of this silkworm-based ecotoxicology research can provide crucial information on the potential risks of MNPs, which can complement preclinical studies using mammals and contribute significantly to improving mammalian welfare.

Materials and methods

Physiochemical characterization of polystyrene micro- and nanoplastics (PS-MNPs)

Commercially prepared polystyrene (PS) micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) (milk-white suspension, 2.5% w/v) used in this study were purchased from MACKLIN® Shanghai, China. The three different sizes of pristine PS-MNPs were PS-S (small) with sizes ranging from 50 to 100 nm, PS-M (medium) with sizes ranging from 5 to 5.9 µm, and PS-L (large) with sizes ranging from 9 to 9.9 µm. The physicochemical properties of the PS-MNPs were characterized in accordance with our previous study [29]. Briefly, the particles were monodispersed (1 mg/mL stock suspension) in Milli-Q water by sonication at 250 W, 40–45 kHz for 30 min. The morphology of the PS-MNPs was determined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Hitachi HF-3300, Japan) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi SU8000, Japan). The size distribution and average diameter were determined using ImageJ software (V. 1.8.0_172). Additionally, the chemical composition of the particles was confirmed using pyrolysis with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS).

Maintenance of silkworm culture and exposure to PS-MNPs

The silkworm strain (Jinsong × Haoyue) was reared on fresh mulberry under optimum growth conditions [29]. After hatching, the neonate larvae were allowed to acclimatize on finely chopped tender mulberry leaves for two days before being divided into control (CTR) and treatment groups (PS-MNPs). The treatment groups were exposed to environmentally relevant concentrations of PS-S (0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 µg/mL), PS-M (0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 µg/mL), and PS-L (0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 µg/mL) MNPs. The PS-MNPs were carefully sprayed onto fresh mulberry leaves, forming thin films at their designated concentrations. Afterward, the coated leaves were left to air dry naturally at room temperature before being offered for feeding. The exposure doses were selected based on reported concentrations of PS-MNPs in the environment [1], [7], [13], [17]. Larvae in the treatment groups (n = 50 × 3 replicates for each cohort) were fed on mulberry leaves (4 × 2.5˝ pieces) spiked with PS-MNPs. In the CTR group (n = 50 × 3 replicates), the larvae were provided with mulberry leaves treated with autoclaved distilled water. To ensure continuous feeding, leaves were replaced at least three times a day. This feeding regime (CTR and PS-MNPs) continued (for 21 days) until the larvae reached the pre-pupal stage (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Experiment design and characteristics of polystyrene micro- and nanoplastics (PS-MNPs). (A) Silkworm larvae from the second instar until the pre-pupal stage were exposed to three different sizes of PS-MNPs at environmental concentrations and the integrated biomarker responses were determined. CR, conventionally raised; ML, mulberry leaves; DPE, days post-exposure. (B) Physiochemical characteristics were determined by SEM and TEM, and (C) the chemical composition of the particles was reaffirmed by Py-GC/MS.

Ingestion of PS-MNPs and its effect on host phenotype

Ingestion of PS-MNPs can lead to the accumulation of pollutants in the host tissues [29], [32] that subsequently alter the host phenotype. After exposure, the body mass of the individual larva (n = 50, ± standard deviation) from the CTR and treatment groups in each instar was measured on an analytical balance (METTLER TOLEDO, Switzerland). To monitor survivorship, we recorded the number of dead and live individuals in each group throughout the experiment. To analyze the data, we used Kaplan-Meir (log-rank) analysis and generated survival curves using GraphPad Prism (version 9.0).

Samples collection for multi-omics analyses

Given the distinctive effect of medium concentration (0.5 μg/mL) on physiological endpoints (Fig. 2A), the subsequent molecular analyses were performed with individuals from the said concentration cohorts of different sizes. Twenty larvae (on the fourth day of the fifth instar) from each cohort were randomly selected for multi-omics analyses (Fig. 1A). Larvae were dissected in a sterile environment for the sampling of tissues (gut epithelium, fat body, silk glands, and epidermis) and gut contents from individual larvae as a biological replicate [28]. All samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 ℃ until further use.

Fig. 2.

Effects of different sizes of PS-MNPs at different concentrations on the general health of silkworms. (A) Larval body mass and (B) survivorship of the silkworms. Different letters indicate significant differences across the groups estimated by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test. Survival curves were generated in GraphPad Prism (version 9.0) based on Kaplan-Meir (log-rank) analysis.

Untargeted metabolomics analysis

To investigate the effect PS-MNPs exposures on silkworm gut metabolites, six samples of gut tissues from the freeze-dried stock of treated and CTR individuals were taken for untargeted metabolomics analysis as described previously [25]. Briefly, tissues were homogenized (two 5-mm zirconia beads) with Precellys 24 (Bertin technologies, France) homogenizer. Then, a 400 µL methanol: water (4:1 v/v) and 0.02 mg/mL L-2-chlorophenylanin as internal standard was added to 50 mg of sample and vortexed for 60 sec. For protein precipitation, the samples were placed at −20 °C for 30 min. Afterward, supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 13,000 g (4 ℃) for 15 min and transferred to sample vials for LC-MS/MS analysis.

To ensure the stability of the analysis, pooled quality control (QC) samples were prepared by mixing equal volumes of all individual samples. These QC samples were injected at regular intervals throughout the analysis. A 2 µL sample was run on the UHPLC-Q Exactive System of Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) for metabolite profiling. Mass spectrometric data were collected with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source operating in positive/negative ion mode. The optimal conditions were set as follows: heater temperature was set at 400 ℃, capillary temperature 320 ℃, Aux gas flow rate 10 arb, sheath gas flow rate 40 arb, ion spray voltage floating 3500 V in positive and −2800 V in negative mode, normalized collision energy 20–40-60 V, and detection was carried out over a mass range of 70–1050 m/z. After completion of mass spectrometry detection, the LC/MS raw data were processed using Progenesis QI software (Waters Corporation, Milford, USA). The resulting three-dimensional data, including sample information, metabolite names, and spectral intensities, were exported in CSV format.

In the data processing step, internal standard peaks, false positive peaks, and variables with a relative standard deviation (RSD) >30% of the QC samples were removed from the data matrix. Metabolites were identified by referring to information from previous studies and utilizing metabolome databases including HMDB (https://www.hmdb.ca/) Meltin (https://meltin.scripps.edu/) and KEGG (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/). The relative concentration of a metabolite was determined by calculating the ratio of its peak integral to the total spectral area. Partial Least Square Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) and Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) was performed in the ropls R package (Version 1.6.2) to determine the stability of the model. Significantly changed metabolites (SCMs) were determined based on the values of variable importance in projection (VIP) obtained from the OPLS-DA model (VIP > 1, p < 0.05). Subsequently, differential metabolites were mapped into their respective biochemical pathway according to the function they perform.

Quantification of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS)

To investigate the effect PS-MNPs exposures on short-chain fatty acids in silkworm gut, samples of gut contents from the freeze-dried stock of treated and CTR individuals (6 replicates) were processed for GS-MS analysis. Gut contents (25 mg) were taken in a 2 mL grinding tube containing 500 µL water and 0.5% phosphoric acid. Afterward, samples were frozen ground (50 Hz) for 3 min (twice), sonicated for 10 min, and centrifuged for 15 min at 13,000 g (4 ℃). Supernatants were collected in 1.5 mL tubes and 0.2 mL n-butanol solvent was added. These tubes were then vortexed for 10 sec, ultrasonicated for 10 min at low temperature, and centrifuged for 5 min at 13,000 g (4 ℃) to collect supernatants. The GC–MS system (8890B-5977B, Agilent Technologies Inc, CA, USA) was used for SCFA analyses. The GC was fitted with HP FFAP capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Agilent J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA, USA), with helium as a carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/min and injection (1 μL injection volume) temperature was 260 ℃. Program temperatures were set as; initial column 80 ℃ for 1 min, then increased to 120 ℃ for 10 min, 185 ℃ for 20 min, and 230 ℃ for 3 min. The ion fragments of SCFAs were identified and their absolute quantities in the test samples were calculated by the equations of the standard curve and 2-ethyl butyric acid was used as the internal reference.

Microbiome analysis

To investigate the effect PS-MNPs exposures on the silkworm gut microbiome, samples of gut contents of exposure and CTR individuals (6 replicates) were processed for bacterial DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was extracted from the homogenized samples (50 mg) using the DNeasy® Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. The primer set 515F: GTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA; 806R: GGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT targeting the 16S rRNA gene V4 region was used for PCR as described in our recent study [33]. After purification and quantification of the PCR products, the resultant amplicons were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq platform (CA, USA). Effective reads were obtained after trimming the primers and spurious sequences using the Cutadapt (v2.8) and DADA2 plugin in the Qiime2 (v2021.4) with recommended parameters. Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were obtained and the subsequent taxonomic classification, species richness, community diversity, and composition analyses were performed as described previously [33], [34].

Transcriptome analysis

Gut tissue samples from the CTR and treatment groups (4 replicates) were collected for total RNA extraction using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Genomic DNA was removed using DNases I (Takara, Japan) and the RNA quality and integrity were measured using the ND-2000 NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and agarose gel electrophoresis (1%). Total RNA (1 μg) was used for the construction of transcriptome libraries using the TruSeqTM RNA kit (Illumina, CA, USA). The mRNA was isolated with oligo (dT) beads according to the polyA selection method. Double-stranded cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript double-stranded cDNA kit (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and was subjected to end repair. Phosphorylation, and ‘A’ base addition. Paired-end RNA-Seq library (2 × 150 bp) was sequenced with Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (CA, USA). Furthermore, the reads quality CTR, transcript assembling, expression analysis, functional annotation, identification of differentially expressed genes, and function enrichments were performed as previously described [35], [36].

Statistical analyses

Before statistical analyses, we assessed variance homogeneity using Levene’s test and data normality using Shapiro-Wilk’s test. To compare differences in body mass, metabolite profiles, relative abundances of the gut microbiome, and gene expression changes across the CTR and treatment groups, we performed one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test, and data were expressed as mean values ± standard deviation. Alpha and Beta-diversity indices were calculated using the R package [33], [34]. The phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt2, v2.4.1) and Statistical Analysis of Metagenomic Profile (STAMP) was used to predict the potential functions of PS-MNPs-driven changed microbiome of the silkworms. Metabolites-metabolites correlation networks (Pearson correlation r > 0.8) were generated in Gephi 0.9.6. The statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of PS-MNPs used in this study

Microscopic and analytical investigation revealed that the particles were spherical with a mean diameter of 91.92 nm ± 4.11 SD for PS-S, 5.69 µm ± 0.17 SD for PS-M, and 9.77 µm ± 0.39 SD for PS-L (Fig. 1B), which is consistent with the manufacturer's description (Fig. 1B). In addition, Py-GC/MS analysis confirmed the chemical composition of the particles (Fig. 1C).

Effects of PS-MNPs-exposures on the general health of silkworms

The potential effects of PS-MNPs exposures on the growth and survivorship of silkworms were investigated. First, three exposure doses (0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 µg/mL) were selected based on their realistic concentrations present in the environment [1], [7], [13], [17]. The results showed that the lower concentrations of PS-MNPs had a stimulatory effect and increased the silkworms’ larval body weight (p < 0.05) across all treatment groups (except PS-L 1.0 μg/mL) (Fig. 2A). Meanwhile, the exposures had no negative effect on the survivorship of silkworms (p > 0.05, Fig. 2B). These results indicate that the field-realistic concentrations of PS-MNPs do not pose a threat to silkworms’ survival, although there may be a tradeoff between metabolic functions to allocate more resources to increase the growth. Given the distinctive effect of medium concentration (0.5 μg/mL) on physiological endpoints (Fig. 2A), the subsequent analyses were performed with individuals from this concentration cohort of different sizes.

Ps-mnps-exposures induced alterations in silkworms’ gut metabolites

To address the question regarding the overall biological responses to PS-MNPs, the untargeted metabolomic analysis was performed to assess the metabolite profiles in the guts of CTR and exposure groups. The metabolite profiles in the CTR and treatment groups were visualized using a PLS-DA model (Fig. 3A). The PLS-DA score plot (R2 = 0.76, Q2 = -0.85) demonstrates the high predictive accuracy of the regression model. The results showed that all exposure groups were distinctly separated from the CTR group, indicating that the silkworms’ metabolism is highly sensitive to contaminants. However, there was no clear separation pattern observed between the different particle sizes within the treatment groups, as they overlapped with each other (Fig. 3A). However, further analysis using pairwise comparison showed that metabolome profiles were separated between different particle sizes (Fig. S1), indicating that particle size plays a significant role in shaping the metabolome profiles. In addition, our untargeted metabolomics analysis successfully annotated a total of 860 metabolites, including 488 in positive ion mode and 372 in negative ion mode (Table S1). These annotated metabolites were then categorized into various functional categories based on their biological roles in the KEGG database (Fig. S2). Amino acids, carbohydrates, lipids, nucleotides, vitamins and cofactors, carboxylic acids, and other biomolecules were the most prominent metabolite classes identified in our analysis. Of these metabolites, 415 were significantly changed upon exposure to PS-MNPs (Fig. 3B). Fig. 3C shows the SCMs shared and unique to different particle sizes concerning the CTR group. The PS-S, PS-M, and PS-L groups showed 213 (up = 147, down = 66), 191 (up = 134, down = 57), and 169 (up = 145, down = 24) altered metabolites, respectively (Fig. 3C and S3). PS-MNPs exposure perturbed various metabolic pathways regulating cellular processes, genetic information processing, environmental information processing and organismal system, and induced the metabolisms of amino acids, nucleic acids, lipids, carbohydrates, vitamins, etc. (Table S2, Fig. S4). The impact of PS-MNPs exposure on the metabolome was size-dependent, with smaller particles causing a more pronounced effect than larger sizes. Moreover, it was observed that the abundance of most of the SCMs increased in the exposure groups.

Fig. 3.

PS-MNPs induced metabolomic alteration in the gut of silkworms. (A) PLS-DA scatter plot displays the patterns of metabolite changes between the CTR and exposure groups. (B) Metabolites clustering heatmap shows the significantly changed metabolites (SCMs) between the CTR and exposure groups. (C) The Venn diagram shows the distribution pattern of significantly changed metabolites (SCMs) across the different groups.

Moreover, to gain a global view of the metabolite alterations induced by PS-MNPs, we established a correlation network using Pearson correlation analysis (Fig. S5). In the CTR group, metabolites from different biological categories are marked with different colors, while changes in corresponding metabolites in the treatment groups are visualized based on abundance. Also, a map of the biochemistry pathways regulating the metabolism exhibits the PS-MNPs-induced metabolites changes (Fig. S6). Predominantly, the exposures changed the biosynthesis pathways related to nucleotide metabolism (purine metabolism and pyrimidine metabolism), amino acid metabolism (lysine biosynthesis, arginine and proline metabolism, histidine metabolism, tyrosine metabolism, tryptophan metabolism, alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism, glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism, etc.), carbohydrate metabolism (pentose and glucuronate interconversions, ascorbate and aldarate metabolism, etc.), lipid metabolism (glycerophospholipids metabolism, primary bile acid biosynthesis, sphingolipid metabolism, alpha-linolenic acid metabolism, etc.), and metabolism of cofactors and vitamins (riboflavin metabolism, nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism, pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis, biotin metabolism, etc.) (Table S2). Perturbation of amino acid biosynthesis pathways in the exposure groups upregulated the levels of L-tryptophan, glutamic acid, histidine, phenylalanine, serine, kaempferol, and cystathionine while downregulating the levels of aspartic acid, asparagine, and lysine (Fig. 4A). Alterations in purine and pyrimidine pathways upregulated several nucleosides and their intermediates, including 2′-deoxyuridine, adenosine 5′-diphosphate, adenosine monophosphate, adenylosuccinate, adenylosuccinic acid, adenosine diphosphate (ADP), cytidine, guanosine 5′-monophosphate, uracil, uridine 5′-diphosphate, and xanthosine 5′-disphosphate (Fig. 4B). Meanwhile, some nucleosides and their intermediates, such as 2′-deoxyguanosine, deoxycytidine, guanosine, L-dihydroorotic acid, ribose 1-phosphate, and urate-3-ribonucleoside, were significantly downregulated. Perturbation of carbohydrate metabolism upregulated the levels of ascorbic acid, D-glucuronic acid, N-glycolylneuraminate, ribitol, and N-acetylmuramate, while downregulating the profiles of L-arabinose, L-threonic acid, and ribose 1-phosphate in the exposure groups (Fig. 4C). For lipids, most of the lipid metabolites and their derivatives, such as adipic acid, astragalin, delphinidin, glycocholate, phosphocholine, and quercetin 3-beta-D-glucoside, were significantly upregulated, and only the stearamide metabolite was downregulated in the exposure groups (Fig. 4D). These metabolites play critical biological roles in homeostasis, energy metabolism, xenobiotic detoxification, and immune defense, and their perturbations can directly and/or indirectly affect the host phenotype. The higher abundance of the SCMs, with more upregulated SCMs than downregulated, has a strong association with increased body weight in the exposure groups.

Fig. 4.

PS-MNPs perturbed the metabolisms of (A) amino acids, (B) nucleosides, (C) carbohydrates, and (D) lipids, as well as affected (E) valeric acid (a short chain fatty acid) level in the gut contents of silkworms. The data are presented as mean values ± standard deviation and significant differences between groups were estimated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test, which is denoted by different letters.

Ps-mnps-exposures reduced the production of valeric acid in silkworm gut

The effect of PS-MNPs on the levels of SCFAs was assessed in the gut contents of silkworms (Fig. 4E). The results showed a significant decrease in the level of valeric acid in all exposure groups (p < 0.001). However, no significant differences were observed in the levels of other SCFAs including acetic acid, butanoic acid, hexanoic acid, isohexanoic acid, isobutyric acid, propanoic acid, and isovaleric acid in the gut contents of exposure or CTR groups (Fig. 4E). These findings suggest that the exposure to PS-MNPs has a selective effect on the levels of certain SCFAs in the gut, which could have implications for gut microbiota and host health.

PS-MNPs-exposures changed the structure and composition of the gut microbiome

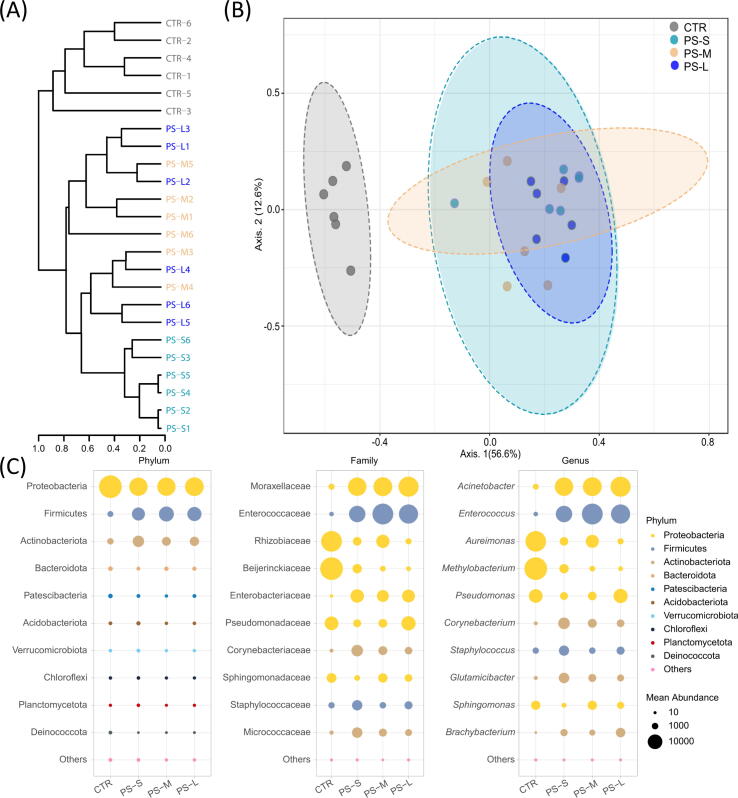

High-throughput sequencing was conducted to investigate changes in the gut microbiome in the silkworms exposed to PS-MNPs. Amplicon library sequencing yielded 3,892,367 effective reads (27,161–162,181 per sample). Rarefaction curves based on species richness reached the saturation plateau indicating the sequencing depth was sufficient to estimate the diversity (Fig. S7). A total of 2,475 ASVs were identified from all samples, of which only 53 were common among the four groups, whereas 563, 474, 442, and 510 were unique to CTR, PS-S, PS-M, and PS-L groups, respectively (Fig. S8A). The Alpha-diversity indices namely ACE, Chao 1, Shannon, and Simpson were used to estimate the species richness and community diversity across the CTR and exposure groups. There were no significant differences in the total observed species (Fig. S8B). However, Bray-Curtis dissimilarity-based clustering dendrogram separated microbial communities of the CTR group from the exposure groups (Fig. 5A). Also, the Beta-diversity indices based on the Bray-Curtis distance matrix revealed significant differences (PCoA, PERMANOVA F-value = 10.7, R2 = 0.61, p < 0.001) and all exposure groups exhibited a clear separation from the CTR group demonstrating the sensitivity of silkworms’ gut microbiota to the exposed materials (Fig. 5B). The treatment groups overlapped with each other and did not show a clear separation pattern between the different particle sizes, however, a pairwise comparison exhibited differences in bacterial community structures between PS-S vs PS-M (F-value = 3.28, p = 0.01) and PS-S vs PS-L (F-value = 3.81, p = 0.003) but not between PS-M vs PS-L (F-value = 2.23, p = 0.07) groups (Fig. S9). These findings highlight the significance of particle size on their potential impact on silkworms’ gut microbiota with smaller sizes had a more pronounced effect than the larger sizes (PS-S > PS-M > PS-L) which is concomitant with the effect of PS-MNPs on metabolites.

Fig. 5.

PS-MNPs changed the structure and composition of silkworm gut microbiota. (A) Dendrogram based on Bray-Curtis matrix showing clustering pattern of microbial communities under exposure to different particle sizes. (B) PCoA plot visualizes the gut bacterial community structure. (C) Bubble plots based on the phylum, family, and genus taxa show the differences between the CTR and exposure groups.

Furthermore, the study analyzed the shifts in the microbiome community structure in greater detail. The results indicated significant changes at all taxonomic ranks (p < 0.07), with alterations at the phylum, family, and genus levels shown in Fig. 5C. The phyla Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria, which accounted for over 98% of the total microflora, were significantly different in the CTR and exposure groups (p < 0.07). The exposure groups had a higher abundance of Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, while the phylum Proteobacteria was more abundant in the CTR group. These changes were also translated at the lower taxonomic levels i.e., the family and genus levels. In the CTR group, the families Rhizobiaceae, Beijerinckaceae, Pseudomonandaceae, and Sphingomonandaceae were more abundant than the exposure groups. On the other hand, the families Moraxellaceae, Enterococcaceae, Enterobacteriaceae, Corynebacteriaceae, Staphylococcaceae, and Micrococcaceae were enriched in the exposure groups. Likewise, the genera Acinetobacter, Enterococcus, Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus, Glutamicibacter, and Brachybacterium were highly abundant in the exposure groups, whereas Aureimonas, Methylobacterium, and Sphingomonas (also in PS-M) were the dominant genera in the CTR group (Fig. 5C). Although the microbiota structure and composition in the exposure groups shared some similarities, the LefSe analysis revealed significant differences in some taxa among the different exposure groups (Fig. S10). The FDR (<0.05) and LDA scores (>4) indicated that nineteen features at the genus level were significantly changed in the dataset (Table S3).

Functional prediction of the changed microbiome and their associations with metabolites

The phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt2) was used to predict the potential functions of PS-MNPs-induced dysbiotic silkworms’ gut microbiome. The predicted function profiles showed significant differences between the CTR and exposure groups, which were consistent with the observed metabolite and microbiome profiles (Fig. 6A and Fig. S11). The CTR group was separated from the exposure groups, whereas the latter overlapped with each other as described earlier (namely, metabolome and microbiome) (Fig. S11). Major differences were observed in lipid metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, amino acid metabolism, carbohydrates metabolism (glycan biosynthesis), energy metabolism, xenobiotic biodegradation and metabolism, and biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites among others (Fig. 6A). Most of these metabolic functions were significantly upregulated in the exposure groups, especially in the small-size particles (PS-S). Since having found a broader resemblance in the metabolite changes, microbiome alterations, and their predicted function profiles, we performed the Spearman correlation analysis to better understand the associations between the silkworms’ gut microbiome and its metabolites in each exposure group (Fig. 6B). Significant correlations (r > 0.8, p < 0.05, both positive (blue lines) and negative (red line)) were observed between the gut microbiome (at genus level) and metabolites. For example, the genus Aureimonas was positively correlated with pantothenic acid and guanosine 3′, 5′-cyclic monophosphate but negatively correlated with L-aspartic acid, L-glutamate, and L-arabinose. Pseudomonas had positive associations with L-asparagine and L-serine but was negatively associated with adipic acid. Furthermore, Sphingomonas was negatively correlated with citric acid but positively correlated with coenzyme A and lysophospholipid (Lyso PC) (PS-S). Aureimonas and Curtobacterium had a positive association with Lyso PC but a negative association with butanoic acid (PS-M). Glutamicibacter abundance had a positive correlation with thymine, D-allose, L-proline, and sphingomyelin (SM (OH)) profiles (PS-L) and negative correlations with citric acid (PS-L) L-proline, D-allose, 5, 6-dihydroxyprostaglandin, and L-citrulline (PS-S), and higher abundance of Enterococcus was associated with the upregulation of L-serine (Fig. 6B). These correlations highlight the potential impact of the changed microbiome on the host’s metabolic and physiological state.

Fig. 6.

Functional prediction and microbes-metabolites correlations. (A) The heatmap shows changes in the predicted functional potentials of the changed microbiome. (B) Significant correlations (r > 0.8) exist between bacteria (color teal) and metabolites (color lavender). Red lines indicate negative correlations, whereas positive correlations are denoted by blue lines. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Transcriptional response of silkworms to PS-MNPs exposure

Transcriptome analysis yielded 44–50 million raw reads per sample, and after quality filtering, about 43–47 million clean reads (97.5–98%) per sample were retained in the gut tissue samples of the silkworms (Table S4). Functional annotation was performed by searching the clean reads against several databases including GO, KEGG, COG, NR, Swissport, and Pfam, resulting in the annotation of over 17 thousand genes (Fig. S12A, Table S5). Among these genes, 7468 were shared by both the CTR and exposure groups, while 559, 142, 38, and 66 genes were uniquely expressed in the CTR, PS-S, PS-M, and PS-L groups, respectively (Fig. S12B). Using the DESeq2 method, we identified 1256 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with a Log2FC > 2 and a p-adjust value of ≤ 0.05 (Fig. 7A). Among the exposure groups, PS-S had the greatest impact on the number of DEGs (807, up = 430, down = 377), followed by PS-M (572 DEGs, up = 460, down = 112), and PS-L (423 DEGs, up = 306, down = 117) (Fig. S13, Table S6). Notably, the number of DEGs unique to each particle size steadily decreased with increasing particle size i.e., 520 in PS-S, 178 in PS-M, and 139 in PS-L, whereas 127 DEGs were shared among them (Fig. 7B). These results suggest that smaller particle size had a more significant impact on host gene expression in silkworms, and the upregulated genes were more dominant than the downregulated ones.

Fig. 7.

PS-MNPs-induced changes in the gene expression profiles of silkworms. (A) The heatmap depicts the relative expression level of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the CTR and exposure groups. (B) The upset plot displays the distribution pattern of DEGs across the exposure groups. The DEGs are involved in regulating the metabolism of (C) carbohydrates, (D) amino acids, (E) lipids, and (F) xenobiotics.

Furthermore, we found that exposure to PS-MNPs resulted in significant changes in the citrate cycle (TCA cycle), carbohydrates metabolism, amino acid metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, lipid metabolism, metabolism of cofactors and vitamins, and biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites (Fig. S14). To determine the functions of DEGs, the GO classification provides an ideal system for the annotation of genes. The exposure groups in GO classification mainly assigned the DEGs into three categories namely, biological process, cellular component, and molecular function (Fig. S15A). For the biological processes, the DEGs were putatively involved in catalytic activity, whereas the membrane part represented the highest number of DEGs in the cellular component category, indicating the potential impact of PS-MNPs on the cell membrane. Meanwhile, the metabolic and cellular processes were the major GO enrichment terms in the molecular function classes and explained the metabolic perturbations of various pathways, which suggests that PS-MNPs exposure may alter the enzymatic activity in silkworms (Table S7). To gain further insights into the biological functions of the DEGs, the COG database was employed. The COG enrichment analysis revealed that the DEGs in the exposure groups were predominantly associated with various metabolic processes, including amino acid metabolism (PS-S = 38, PS-M = 33, and PS-L = 25), carbohydrate metabolism (PS-S = 56, PS-M = 46, and PS-L = 41), lipid metabolism (PS-S = 30, PS-M = 26, and PS-L = 17), and nucleotide metabolism (PS-S = 12, PS-M = 4, and PS-L = 5) (Fig. S15B, Table S8). The exposure to PS-MNPs also resulted in changes in the expression of genes involved in information storage and processing, as well as cellular processes and signaling. Notably, a considerable number of DEGs had unknown functions (Fig. S15). Importantly, several genes regulating carbohydrate metabolism (Fig. 7C), amino acid metabolism (Fig. 7D), lipid metabolism (Fig. 7E), xenobiotic biodegradation (Fig. 7F), and nucleotide metabolism were significantly upregulated in the exposure groups (Table S6). However, some genes involved in immune response and host defense such as cecropin B, antibacterial peptide enbocin, and heat shock protein 68 were significantly downregulated in the exposure groups and may have implications for host defense. Further detail on the regulation (up and down) of DEGs from various metabolic, cellular, and molecular function pathways is presented in Table S6. Overall, exposure to PS-MNPs had a significant impact on the basic metabolism and biosynthesis processes of silkworms in a size-dependent manner (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Schematic of PS-MNPs-induced metabolic disorders in overall energy balance. Increased silkworm growth (weight gain) was attributed to enhanced energy reserves (ATPs) triggered by tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle that stimulated (A) amino acid metabolism, (B) lipid metabolism, (C) carbohydrates metabolism, and (D) nucleotide metabolism. (E) The PS-MNPs induced dysbiosis of gut microbiota, leading to significant differences in the predicted functional profiles.

Discussion

In recent years, the impact of MNPs on the environment has become a topic of great concern, as exposure to these materials has dramatically increased [1], [4], [13], [37], [38], [39]. Of these, polystyrene polymers are among the most commonly used materials in the manufacturing of everyday items [40]. Polystyrene micro- and nanoplastics (PS-MNPs) have been found in soils and present a model plastic to be adopted in toxicological studies [41], [42]. To better understand the effects of PS-MNPs on terrestrial organisms, we conducted a long-term exposure study using environmentally relevant concentrations of three different particle sizes of PS-MNPs in silkworms. The potential effects were examined on the silkworms’ physiological endpoints, including growth and survivorship, as well as their metabolic functions and molecular pathways (Fig. 8). In general, the current concentrations of MNPs in the environment may not pose a serious threat to individual organisms, with an exception for some very susceptible ones [1], [9], [17]. Our findings demonstrated that the long-term, environmentally realistic exposure to PS-MNPs did not affect the silkworm survival rate, however, changed the physiological and metabolic functions, altered the gut microbiome, and gene expression levels, and eventually increased the body weight (Fig. 8). Moreover, we found that particle size played a major role in the observed outcomes, with small particles inducing a stronger influence, which reinforced the notion that smaller size particles cause greater impacts due to a larger surface/volume ratio, higher cellular internalization, and increased disruption of the endocrine system as compared to the larger particles [14], [15], [37].

The stimulatory effect on body weight, when exposed to environmentally realistic concentrations of MNPs is not often reported. This may be attributed to the fact that most studies that reported adverse effects on growth and survival have used concentrations considerably higher than those found in the environment [1], [15], [36], [37], [43]. For instance, higher concentrations of NPs decreased the weights of Enchytraeus crypticus but low concentrations had stimulatory effects on body weight and cocoon production [24]. Furthermore, the impact of MNPs-induced toxicity on organisms can also be modulated by their feeding habits, specifically the availability of food. For example, the growth of Daphnia magna exposed to PS-MPs increased at high food (algae) abundance but decreased when the availability of algae was low [39]. Besides the direct effects of PS-MNPs on growth, the chemical leachates released from plastics such as bisphenol A, phthalates, and organotin, can disrupt the endocrine system and stimulate the growth and reproduction of Daphnia [7], [44]. MNPs and their leachates are considered obesogenic compounds that disrupt lipid and energy metabolism, leading to weight gain and obesity in humans [38], [45]. However, the mechanisms through which MNPs affect growth in different biological contexts, including host transcriptomic and metabolic changes and gut microbiota-MNPs interactions, remain poorly studied. As a result, our current understanding of how MNPs impact organisms’ growth is limited, and further research is necessary to fully comprehend the molecular mechanisms underlying these effects.

The adoption of high-throughput multiomics approaches (metabolomics, genomics, and transcriptomics) has proven to be useful in uncovering subtle effects and adverse outcome pathways of environmental contaminants [13], [16], [23], [46], [47], [48]. In our study, we employed a similar approach and found that exposure to PS-MNPs altered the regulation of important metabolic pathways and changed the metabolisms of carbohydrates, lipids, amino acids, and nucleotides (Fig. 8). Also, exposure to PS-MNPs altered the structure and composition of the gut microbiome, and the predicted functional profiles were strongly associated with the metabolic pathways mentioned earlier. These metabolic changes resulted in increased energy reserves (ATP) and ultimately led to an increase in the body weight of the silkworms.

The upregulation of metabolic pathways in response to PS-MNPs exposure likely contributed to the elevated body weights observed in the exposure groups. This is consistent with previous studies which have shown that the upregulation of metabolic pathways can lead to an increased abundance of metabolites that directly affect the organism phenotypes [13], [23]. In our hands, upregulation of the metabolic pathways in response to PS-MNPs exposure likely contributed to the observed increase in body weight, because their downregulation in response to toxic fluoride treatment was associated with reduced body weight and survivorship, altered gut microbiota, and damaged epithelial cells of the silkworms [49]. Carbohydrates, lipids, and amino acids are the three major energy reserves required for the growth, development, and other physiological processes of organisms [16], [23], [48]. Among them, lipids play a crucial role in insect life as they provide energy for growth and development, as well as for other essential processes such as flight, migration, diapause, and pheromone synthesis [50]. Our KEGG analysis showed that PS-MNPs exposure influenced the expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism, including fatty acid transport, cholesterol metabolism, and lipogenesis. This effect promoted lipid metabolism required for protein synthesis, maintaining energy reserves for physiological processes, and providing energy for the silkworm growth [13], [36]. The PS-MNPs-induced increase in lipid metabolites is consistent with a recent study in mice where PS-NPs acted as potential obesogens by reducing lipolysis and lipid mobilization [51]. Also, Galleria mellonella feeding on plastic films was able to maintain lipid reserves at a similar level as their counterparts feeding on honeycomb but higher than the starved individuals [52], further highlighting the obesogenic role of plastics.

Carbohydrate metabolism in silkworms is another important pathway of energy homeostasis and is vital for growth and development [15], [53]. Exposure to PS-MNPs can upregulate genes involved in the TCA cycle, promoting the carbohydrate [13] and energy metabolism in the silkworms [15], [35]. This effect has been associated with an increase in ATP production, which in turn, correlates with the enhanced body weight of the exposed silkworms. Additionally, PS-MNPs can also upregulate genes related to amino acid metabolism, which can facilitate protein digestion and absorption, leading to improved energy homeostasis [13]. Also, the accelerated metabolism of amino acids such as L-tryptophan, glutamic acid, histidine, phenylalanine, and serine, has been reported to enhance growth and facilitate the host to adapt to oxidative stress [18], [54]. The upregulation of genes involved in nucleotide metabolism, as observed in black soldier flies, suggests that plastic exposure may have a broader impact on cellular metabolism beyond the energy homeostasis [55]. While the upregulation of genes involved in xenobiotic detoxification may indicate that the silkworms were attempting to mitigate the effects of the exposure by breaking down and eliminating the plastic particles [13], [29], [56]. On the other hand, exposure to PS-MNPs resulted in the downregulation of genes related to immune defense, which could impact the immune competence of the host [13], [57]. Collectively, these findings suggest that PS-MNPs disrupt metabolic homeostasis and enrich energy reserves, which may be the primary mechanism responsible for the increased body weight of the silkworms exposed to environmentally realistic concentrations of PS-MNPs.

Recent studies have also revealed the importance of the silkworm gut microbiome in various aspects of host physiology, including nutrient metabolism, disease resistance, and immune defense [25], [54], [58], [59]. Exposure to PS-MNPs can change the structure of the microbial community, with smaller particles having a stronger impact. The enrichment of certain taxa while reducing the abundance of others indicates trade-offs between the altered microbial communities. PS-MNPs exposure increased the Firmicutes/Proteobacteria ratio, which may enhance the host’s capacity for energy harvest and lead to weight gain [4], [19], [60]. Silkworm gut is predominantly occupied by Proteobacteria [25], however, exposure to PS-MNPs decreased their abundance in favor of Firmicutes, which can enhance the host’s energy harvest capacity and promote weight gain [61]. The enrichment of genera Acinetobacter and Enterococcus in the exposure groups, positively correlated with body weight, suggests that they might be potential biomarkers for obesity. These taxa have health-promoting potential and an improved capacity for energy harvest and storage, leading to increased caterpillar body weights [54], [58], [59], [62], [63]. In accordance with our study, these taxa were strongly associated with the gut microbiota of G. mellonella, Tenebrio molitor, and Tribolium castaneum which had consumed PS-MNPs and other kinds of plastics [21], [22], [64]. The genomes of these genera contain multiple genes involved in decomposition and detoxification, which render them capable of plastics biodegradation and mineralization, thereby improving host fitness (body mass and survival), and providing opportunities for the development of remediation approaches [21], [64]. The higher abundance of these taxa in the exposure groups can partly explain the increased body weight of the exposed silkworms, although further empirical evidence is needed to confirm this notion. It is important to note that MNPs are potential obesogens in the environment [38], and dysbiotic gut microbiota may aggravate the risk of obesity in the exposed organisms.

Moreover, gut microbiota dysbiosis has been linked with metabolism disorders and its dysregulation can have implications for overall organismal health and physiology [19], [23], [43], [47]. In our study, the predicted functional profiles of PS-MNPs-induced dysbiotic gut microbiota had a strong association with lipid, nucleotide, amino acid, carbohydrate metabolism (glycan biosynthesis), and energy metabolism, which is consistent with the observed metabolite profiles discussed earlier. This finding supports the notion that shifts in the composition of gut microbiota are significantly correlated with host metabolite changes [49]. The abundance of Enterococcus, Acinetobacter, and Aureimonas was correlated with the availability of certain metabolites, such as carbohydrates (arabinose, allose), amino acids (glutamic acid, aspartic acid, L-serine, tryptophan), nucleosides (guanosine, adenine), and lipids (butanoic acid, adipic acid), which suggests that these bacterial taxa may influence the bioavailability of these metabolites and consequently affect the health of the host [49], [54]. For example, in our recent study, Enterococcus was found to exhibit an efficient ability for L-tryptophan production and was shown to have the probiotic potential for silkworms [54]. Moreover, the gut microbiota dysbiosis induced by MNPs exposure can have a profound impact on the production of SCFAs in the gut. SCFAs are crucial bacterial-derived metabolites that are produced through the fermentation of dietary carbohydrates, fibers, and other phytonutrients in the digestive tract. These metabolites play a key role in regulating and maintaining gut homeostasis and immune functions [61], [65]. Exposure to PS-MNPs has been found to decrease the abundance of SCFA-producing genera [43], [65]. In our study, we observed a significant decrease in the amount of valeric acid in the exposure groups, which was associated with the reduced abundance of Proteobacteria. However, the precise biological mechanism underlying the effect of Proteobacteria on valeric acid metabolism and its biological significance in silkworms and other insects remain unclear. Nonetheless, the gut microbiota is a valuable biomarker for environmental contaminants, and further research is needed to elucidate the functional connection between the gut microbiota and host metabolism.

Conclusion

Our study provides robust evidence that environmental concentrations of three different sizes of PS-MNPs, when present in the diet of silkworms, have a stimulatory effect on growth and do not pose risks to survivorship. At the molecular level, PS-MNPs exposure resulted in the dysregulation of various metabolic pathways, altered energy metabolism, and caused dysbiosis of gut microbiota. Notably, the observed outcome effects were size-dependent, with small-size particles having a stronger impact. The PS-MNPs-induced accelerated metabolism of carbohydrates, amino acids, lipids, nucleotides, vitamins, and other secondary metabolites enhanced energy reserves available for physiological functions. Furthermore, the increased relative abundance of gut Acinetobacter and Enterococcus could enhance the capacity of energy harvest from food and promote silkworms’ growth. The host transcriptomic analysis provided molecular insight into the DEGs significantly enriched in the metabolic pathways that regulate energy metabolism and indicated the causal link with the metabolites. Although a strong functional connection between gut microbiota and metabolites exists, the exact biological mechanisms underlying these interactions remain unclear and further research is needed to decipher these associations. Moreover, the stimulatory effects of PS-MNPs on energy metabolism and body weight may have trade-offs for other traits, such as immunity and disease resistance, that remain poorly understood. The observed stimulatory effects on body weight and increased energy reserves suggest that if food is not limited, PS-MNPs might trigger obesity by influencing host energy (particularly lipid metabolism) and gut microbiota homeostasis. And given the significance of gut microbiota in host physiology and metabolic functions, future studies should reveal how environmentally realistic concentrations of MNPs affect microflora and the specific microbial mechanisms for organismal health.

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

This article does not contain any studies with human or vertebrate animal subjects.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Abrar Muhammad: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Data curation, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Nan Zhang: Investigation, Validation. Jintao He: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Xiaoqiang Shen: Investigation. Xinyue Zhu: Validation. Jian Xiao: Investigation. Zhaoyi Qian: Investigation. Chao Sun: Validation. Yongqi Shao: Supervision, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editors from AJE for their editorial assistance. This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32022081, 31970483, and 32250410276), China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (Grant No. CARS-18-ZJ0302), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LZ22C170001), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (226-2023-00089).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Faculty of Engineering, Alexandria University.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2023.09.010.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Agathokleous E, Iavicoli I, Barceló D, Calabrese EJ. Micro/nanoplastics effects on organisms: A review focusing on ‘dose’. J Hazard Mater. 2021;417:126084. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Geyer R, Jambeck JR, Law KL. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci Adv. 2017;3(7):e1700782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Statista, Plastic production worldwide, https://www.statista.com, (2022).

- 4.Agathokleous E, Iavicoli I, Barceló D, Calabrese EJ. Ecological risks in a ‘plastic’world: a threat to biological diversity? J Hazard Mater. 2021;417:126035. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Singh N., Hui D., Singh R., Ahuja I.P.S., FeoF L. Fraternali, Recycling of plastic solid waste: A state of art review and future applications. Compos Part B-Eng. 2017;115:409–422. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2016.09.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kogel T, Bjoroy O, Toto B, Bienfait AM, Sanden M. Micro- and nanoplastic toxicity on aquatic life: Determining factors. Sci Total Environ. 2020;709:136050. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136050. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Xu E.G., Cheong R.S., Liu L., Hernandez L.M., Azimzada A., Bayen S., et al. Primary and secondary plastic particles exhibit limited acute toxicity but chronic effects on Daphnia magna. Environ Sci Technol. 2020;54(11):6859–6868. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c00245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng J., Meistertzheim A.-L., Leistenschneider D., Philip L., Jacquin J., Escande M.-L., et al. Impacts of microplastics and the associated plastisphere on physiological, biochemical, genetic expression and gut microbiota of the filter-feeder amphioxus. Environ Int. 2023;172 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2023.107750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lackmann C., Velki M., Šimić A., Müller A., Braun U., Ečimović S., et al. Two types of microplastics (polystyrene-HBCD and car tire abrasion) affect oxidative stress-related biomarkers in earthworm Eisenia andrei in a time-dependent manner. Environ Int. 2022;163 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2022.107190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu M., Palic D. Micro- and nano-plastics activation of oxidative and inflammatory adverse outcome pathways. Redox Biol. 2020;101620 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang K., Li J., Zhao L., Mu X., Wang C., Wang M., et al. Gut microbiota protects honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) against polystyrene microplastics exposure risks. J Hazard Mater. 2021;402 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Awet T.T., Kohl Y., Meier F., Straskraba S., Grun A.L., Ruf T., et al. Effects of polystyrene nanoparticles on the microbiota and functional diversity of enzymes in soil, Environmental sciences. Europe. 2018;30(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12302-018-0140-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu L.Q.Q., Zheng H., Luan L.P., Luo X.X., Wang X., Lu H., et al. Functionalized polystyrene nanoplastic-induced energy homeostasis imbalance and the immunomodulation dysfunction of marine clams (Meretrix meretrix) at environmentally relevant concentrations. Environ Sci-Nano. 2021;8(7):2030–2048. doi: 10.1039/d1en00212k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miao L., Hou J., You G., Liu Z., Liu S., Li T., et al. Acute effects of nanoplastics and microplastics on periphytic biofilms depending on particle size, concentration and surface modification. Environ Pollut. 2019;255(Pt 2) doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X., Wen K., Ding D., Liu J., Lei Z., Chen X., et al. Size-dependent adverse effects of microplastics on intestinal microbiota and metabolic homeostasis in the marine medaka (Oryzias melastigma) Environ Int. 2021;151 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marana M.H., Poulsen R., Thormar E.A., Clausen C.G., Thit A., Mathiessen H., et al. Plastic nanoparticles cause mild inflammation, disrupt metabolic pathways, change the gut microbiota and affect reproduction in zebrafish: A full generation multi-omics study. J Hazard Mater. 2022;424 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun T., Zhan J., Li F., JiH C. Wu, Effect of microplastics on aquatic biota: A hormetic perspective. Environ Pollut. 2021;285 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao J, Liao Y, Yang W, Jiang X, Li M. Enhanced microalgal toxicity due to polystyrene nanoplastics and cadmium co-exposure: From the perspective of physiological and metabolomic profiles. J Hazard Mater. 2022;427:127937. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Deng Y., Yan Z., Shen R., Wang M., Huang Y., Ren H., et al. Microplastics release phthalate esters and cause aggravated adverse effects in the mouse gut. Environ Int. 2020;143 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang H-M, Byeon E, Jeong H, Kim M-S, Chen Q, Lee J-S. Different effects of nano-and microplastics on oxidative status and gut microbiota in the marine medaka Oryzias melastigma. J Hazard Mater. 2021;405:124207. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Lou Y., Li Y., Lu B., Liu Q., Yang S.-S., Liu B., et al. Response of the yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) gut microbiome to diet shifts during polystyrene and polyethylene biodegradation. J Hazard Mater. 2021;416 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peydaei A, Bagheri H, Gurevich L, De Jonge N, Nielsen JL. Mastication of polyolefins alters the microbial composition in Galleria mellonella. Environ Pollut. 2021;280:116877. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Qiao R, Sheng C, Lu Y, Zhang Y, RenB H. Lemos. Microplastics induce intestinal inflammation, oxidative stress, and disorders of metabolome and microbiome in zebrafish. Sci Total Environ. 2019;662:246–253. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Zhu BK, Fang YM, Zhu D, Christie P, Ke X, Zhu YG. Exposure to nanoplastics disturbs the gut microbiome in the soil oligochaete Enchytraeus crypticus. Environ Pollut. 2018;239:408–415. 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Chen B., Zhang N., Xie S., Zhang X., He J., Muhammad A., et al. Gut bacteria of the silkworm Bombyx mori facilitate host resistance against the toxic effects of organophosphate insecticides. Environ Int. 2020;143 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li G., Xia X., Zhao S., Shi M., LiuY F. Zhu, The physiological and toxicological effects of antibiotics on an interspecies insect model. Chemosphere. 2020;248 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li F., Hu J., Tian J., Xu K., Ni M., Wang B., et al. Effects of phoxim on nutrient metabolism and insulin signaling pathway in silkworm midgut. Chemosphere. 2016;146:478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muhammad A., He J., Yu T., Sun C., Shi D., Jiang Y., et al. Dietary exposure of copper and zinc oxides nanoparticles affect the fitness, enzyme activity, and microbial community of the model insect, silkworm Bombyx mori. Sci Total Environ. 2022;813 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muhammad A., Zhou X., He J., Zhang N., Shen X., Sun C., et al. Toxic effects of acute exposure to polystyrene microplastics and nanoplastics on the model insect, silkworm Bombyx mori. Environ Pollut. 2021;285 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdelli N., Peng L., Chen K. Silkworm Bombyx mori, as an alternative model organism in toxicological research. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25(35):35048–35054. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3442-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meng X., ZhuK F. Chen, Silkworm: A Promising Model Organism in Life Science. J Insect Sci. 2017;17(5):1–6. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/iex064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parenti C.C., Binelli A., Caccia S., Della Torre C., Magni S., Pirovano G., et al. Ingestion and effects of polystyrene nanoparticles in the silkworm Bombyx mori. Chemosphere. 2020;257 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He J., Zhang N., Shen X., Muhammad A., Shao Y. Deciphering environmental resistome and mobilome risks on the stone monument: A reservoir of antimicrobial resistance genes. Sci Total Environ. 2022;838 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He J., Zhang N., Muhammad A., Shen X., Sun C., Li Q., et al. From surviving to thriving, the assembly processes of microbial communities in stone biodeterioration: A case study of the West Lake UNESCO World Heritage area in China. Sci Total Environ. 2022;805 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang L., Peng L.-L., Cao Y.-Y., Thakur K., Hu F., Tang S.-M., et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals gene expression changes of the fat body of silkworm (Bombyx mori L.) in response to selenium treatment. Chemosphere. 2020;245 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang R., Cao Y.-Y., Du J., Thakur K., Tang S.-M., Hu F., et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals the gene expression changes in the silkworm (Bombyx mori) in response to hydrogen sulfide exposure. Insects. 2021;12(12):1110. doi: 10.3390/insects12121110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ding J., Huang Y., Liu S., Zhang S., Zou H., Wang Z., et al. Toxicological effects of nano- and micro-polystyrene plastics on red tilapia: Are larger plastic particles more harmless? J Hazard Mater. 2020;396 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kannan K., Vimalkumar K. A Review of Human Exposure to Microplastics and Insights Into Microplastics as Obesogens. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.724989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogonowski M, Schür C, Jarsén Å, Gorokhova E. The effects of natural and anthropogenic microparticles on individual fitness in Daphnia magna. PloS One. 2016;11(5):e0155063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Long M., Paul-Pont I., Hegaret H., Moriceau B., Lambert C., Huvet A., et al. Interactions between polystyrene microplastics and marine phytoplankton lead to species-specific hetero-aggregation. Environ Pollut. 2017;228:454–463. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matthews S., Xu E.G., Dumont E.R., Meola V., Pikuda O., Cheong R.S., et al. Polystyrene micro-and nanoplastics affect locomotion and daily activity of Drosophila melanogaster. Environ Sci-Nano. 2021;8(1):110–121. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheurer M., Bigalke M. Microplastics in Swiss floodplain soils. Environ Sci Technol. 2018;52(6):3591–3598. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b06003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qiao J., Chen R., Wang M., Bai R., Cui X., Liu Y., et al. Perturbation of gut microbiota plays an important role in micro/nanoplastics-induced gut barrier dysfunction. Nanoscale. 2021;13(19):8806–8816. doi: 10.1039/d1nr00038a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duft M., Schulte-Oehlmann U., Weltje L., TillmannJ M. Oehlmann, Stimulated embryo production as a parameter of estrogenic exposure via sediments in the freshwater mudsnail Potamopyrgus antipodarum. Aquat Toxicol. 2003;64(4):437–449. doi: 10.1016/s0166-445x(03)00102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Laan L.J.W., Bosker T., Peijnenburg W.J.G.M. Peijnenburg, Deciphering potential implications of dietary microplastics for human health. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20(6):340–341. doi: 10.1038/s41575-022-00734-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang Q., Zhang W. Gradual effects of gradient concentrations of polystyrene nanoplastics on metabolic processes of the razor clams. Environ Pollut. 2021;287 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jing J., Zhang L., Han L., Wang J., Zhang W., Liu Z., et al. Polystyrene micro-/nanoplastics induced hematopoietic damages via the crosstalk of gut microbiota, metabolites, and cytokines. Environ Int. 2022;161 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2022.107131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kayis T, Altun M, Coskun M. Thiamethoxam-mediated alteration in multi-biomarkers of a model organism, Galleria mellonella L.(Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26:36623-36633. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Li G, Zheng X, Zhu Y, Long Y, Xia X. In-depth insights into the disruption of the microbiota-gut-blood barrier of model organism (Bombyx mori) by fluoride. Sci Total Environ. 2022;838:156220. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Toprak U, Hegedus D, Doğan C, Güney G. A journey into the world of insect lipid metabolism. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2020;104(2):e21682. 10.1002/arch.21682. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Shiu H.T., Pan X., Liu Q., Long K., Cheng K.K.Y., Ko B.C., et al. Dietary exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics impairs fasting-induced lipolysis in adipose tissue from high-fat diet fed mice. J Hazard Mater. 2022;440 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cassone BJ, Grove HC, Kurchaba N, Geronimo P, Lemoine CMR. Fat on plastic: Metabolic consequences of an LDPE diet in the fat body of the greater wax moth larvae (Galleria mellonella). J Hazard Mater. 2022;425:127862. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127862. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Chen Q., Ma Z., Wang X., Li Z., Zhang Y., Ma S., et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of silkworm fat body after knocking out fibroin heavy chain gene: a novel insight into cross-talk between tissues. Funct Integr Genomics. 2015;15:611–637. doi: 10.1007/s10142-015-0461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liang X., He J., Zhang N., Muhammad A., Lu X., Shao Y. Probiotic potentials of the silkworm gut symbiont Enterococcus casseliflavus ECB140, a promising L-tryptophan producer living inside the host. J Appl Microbiol. 2022;133(3):1620–1635. doi: 10.1111/jam.15675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beale D.J., Shah R.M., Marcora A., Hulthen A., Karpe A.V., Pham K., et al. Is there any biological insight (or respite) for insects exposed to plastics? Measuring the impact on an insects central carbon metabolism when exposed to a plastic feed substrate. Sci Total Environ. 2022;831 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gardon T, Morvan L, Huvet A, Quillien V, Soyez C, Le Moullac G, et al., Microplastics induce dose-specific transcriptomic disruptions in energy metabolism and immunity of the pearl oyster Pinctada margaritifera. Environ Pollut. 2020;266:115180. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Galarza JA, Murphy L, Mappes J. Antibiotics accelerate growth at the expense of immunity. Proc R Soc B: Biol Sci. 2021;288(1961):20211819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Zhang X., Feng H., He J., Liang X., Zhang N., Shao Y., et al. The gut commensal bacterium Enterococcus faecalis LX10 contributes to defending against Nosema bombycis infection in Bombyx mori. Pest Manag Sci. 2022;78(6):2215–2227. doi: 10.1002/ps.6846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang X., Feng H., He J., Muhammad A., Zhang F., Lu X. Lu, Features and Colonization Strategies of Enterococcus faecalis in the Gut of Bombyx mori. Front Microbiol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.921330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mueller M-T, Fueser H, Höss S, Traunspurger W. Species-specific effects of long-term microplastic exposure on the population growth of nematodes, with a focus on microplastic ingestion. Ecol Indic. 2020;118:106698.

- 61.Cao X., Han Y., Gu M., Du H., Song M., Zhu X., et al. Foodborne titanium dioxide nanoparticles induce stronger adverse effects in obese mice than non-obese mice: gut microbiota dysbiosis, colonic inflammation, and proteome alterations. Small. 2020;16(36):2001858. doi: 10.1002/smll.202001858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen B, Mason CJ, Peiffer M, Zhang D, Shao Y, Felton GW. Enterococcal symbionts of caterpillars facilitate the utilization of a suboptimal diet. J. Insect Physiol. 2022;138:104369. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Mason CJ, Peiffer M, Chen B, Hoover K, Felton GW. Opposing growth responses of lepidopteran larvae to the establishment of gut microbiota. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(4):e01941-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Wang Z, Xin X, Shi X, Zhang Y. A polystyrene-degrading Acinetobacter bacterium isolated from the larvae of Tribolium castaneum. Sci Total Environ. 2020;726:138564. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Romano N., Fischer H. Microplastics affected black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) pupation and short chain fatty acids. J Appl Entomol. 2021;145(7):731–736. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.