Abstract

The aim of this study was to systematically review and meta-analyze the efficiency and safety of using the Robotic Stereotactic Assistance (ROSAⓇ) device (Zimmer Biomet; Warsaw, IN, USA) for stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG) electrode implantation in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. Based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, a literature search was carried out. Overall, 855 nonduplicate relevant articles were determined, and 15 of them were selected for analysis. The benefits of the ROSAⓇ device use in terms of electrode placement accuracy, as well as operative time length, perioperative complications, and seizure outcomes, were evaluated. Studies that were included reported on a total of 11,257 SEEG electrode implantations. The limited number of comparative studies hindered the comprehensive evaluation of the electrode implantation accuracy. Compared with frame-based or navigation-assisted techniques, ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation provided significant benefits for reduction of both overall operative time (mean difference [MD], −63.45 min; 95% confidence interval [CI] from −88.73 to −38.17 min; P < 0.00001) and operative time per implanted electrode (MD, −8.79 min; 95% CI from −14.37 to −3.21 min; P = 0.002). No significant differences existed in perioperative complications and seizure outcomes after the application of the ROSAⓇ device and other techniques for electrode implantation. To conclude, the available evidence shows that the ROSAⓇ device is an effective and safe surgical tool for trajectory-guided SEEG electrode implantation in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy, offering benefits for saving operative time and neither increasing the risk of perioperative complications nor negatively impacting seizure outcomes.

Keywords: epilepsy, stereoelectroencephalography, depth electrode implantation, Robotic Stereotactic Assistance (ROSAⓇ), efficacy

Introduction

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder that affects a significant number of people globally. Its overall lifetime prevalence is 7.6 per 1,000 population, with approximately 65 million individuals affected worldwide.1) Epilepsy is a complex disease with several etiologies and risk factors, and it has a trend for a higher incidence among the elderly, which may be problematic considering that life expectancy is steadily increasing in most developed countries.2) Although antiseizure medications are still the first-line treatment for epilepsy, approximately 30% of patients experience drug-resistant seizures, necessitating the consideration of surgical options and requiring thorough clinical evaluation for appropriate decision making.3)

Preoperative evaluation in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy is primarily directed at accurate determination of the epileptogenic zone, a brain region responsible for generating seizures. Its precise localization is important for successful epilepsy surgery, given that resection or disconnection of this area can effectively result in freedom from seizures or a significant reduction of their frequency. Although noninvasive techniques, such as scalp electroencephalography (EEG), video-EEG monitoring, structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS), and positron emission tomography (PET), are necessary initial steps in the evaluation of potential surgical candidates, several such patients entail additional invasive EEG monitoring to record electrical activity directly from the brain, which presumes intracranial placement of subdural grid/strip electrodes or implantation of depth electrodes for stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG).4-6)

The technique of SEEG with the implantation of depth electrodes according to stereotactic principles was first introduced in the 1960s by Talairach and Bancaud in France.7) It has been widely accepted and is currently employed routinely in neurosurgical centers globally. Although subdural grid/strip electrodes allow for the recording of electrical activity only from the brain surface, depth electrodes can be implanted very precisely into deep brain structures or specific regions that presumably contain the epileptogenic zone or are related to relevant epileptic neuronal networks for their direct evaluation.6) Several advantages of this technique include (but are not limited to) its ability to investigate structure-of-interest in the three-dimensional (3D) space, convenient bilateral and/or multifocal implantation of electrodes, low complication rates, and cost-effectiveness.8,9)

Furthermore, recent technological developments and the introduction of advanced computer-aided robotic systems for neurosurgery have revolutionized the technique of SEEG electrode implantation.10-16) In particular, the Robotic Stereotactic Assistance (ROSAⓇ) device (Zimmer Biomet; Warsaw, IN, USA), a neurosurgical system based on state-of-the-art technologies such as infrared tracking, image guidance, and a robotic arm, exhibited several advantages over traditional SEEG electrode implantation methods, that include increased accuracy, reduced operative time, and fewer complications.10,17-21) Nevertheless, its efficiency and safety still necessitate additional critical evaluations. Specifically, in Japan only a few neurosurgical centers employ ROSAⓇ up to date, and unlike North America, Europe, and some Asian countries, clinical experience with this device here is limited.

The aims of this systematic review and meta-analysis were to perform a comprehensive evaluation and to determine existing evidence on the advantages of ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy compared with other available techniques (e.g., frame-based stereotactic implantation, navigation-assisted implantation, and other robotic systems assisted implantation) in terms of accuracy of depth electrode placement, operative time, perioperative complication rates, and seizure outcomes. These data may provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and safety of this method for the preoperative evaluation of patients before planned epilepsy surgery, which can aid in clinical decision making as well as the direction of future research work in the related fields.

Materials and Methods

Relevant articles in literature published up to March 15, 2023, were searched by the first author (AK) based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines22) through several databases (Cochrane, Embase, Web of Science, PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar). Supplementary Material presents the details of the search strategy for each database (Tables S1.1-S1.6), and the PRISMA checklists (Tables S2.1-S2.2).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All articles published in English, Japanese, Russian, and Thai languages that emphasized prospective or retrospective studies on the use of ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy, either with or without comparison to other depth electrode implantation techniques, were included in our systematic review and meta-analysis; nonclinical investigations, preprinted manuscripts, proceedings' materials, reviews, and abstracts were excluded.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

The first author (AK) conducted the initial screening and removal of duplicates using Rayyan, an online systematic review process organizer (https://www.rayyan.ai). Then, two authors (AK and MC) evaluated the remaining articles according to titles and abstracts to assess their adherence to inclusion criteria. Full texts of potentially eligible articles were reviewed, and to align with the objectives of our study, that is, an accuracy of the ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation in terms of entry point error and target point error (primary outcomes), and operative time (overall and per implanted electrode), perioperative complications rate, and postoperative seizure outcomes (secondary outcomes), relevant information was extracted. Moreover, to determine any additional relevant publications, gray literature was searched through the reference lists of the included articles.

Afterward, the data were extracted by the two authors (AK and MC) into a standard form created in separate Microsoft Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft Corp., 2022), including the following information: the first author of the article, year of publication, country of study origin, study design, applied techniques of SEEG electrodes implantation, patient characteristics (e.g., number, age, sex, and diagnosis), number of implanted depth electrodes, accuracy of electrode implantation (e.g., entry point error and target point error), operative time (overall and per implanted electrode), complications, further treatment (e.g., SEEG-guided resection), seizure outcomes (according to Engel classification), and length of follow up.

Using the methodological index for nonrandomized studies (MINORS) score,23) the quality of publications was assessed by the two authors (AK and MC). The maximum MINORS scores for comparative and noncomparative studies are 24 and 16, respectively.

To achieve consensus among the authors, any discrepancies in study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment were resolved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative analysis was carried out only for the assessment of comparative studies. Risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were utilized for dichotomous data, and mean differences (MDs) and 95% CIs were utilized for continuous data in meta-analyses. If standard deviation values were missing in the included studies, they were calculated by the first author (AK). Using the I2 statistic, with more than 50% indicating significant heterogeneity, heterogeneity was assessed. Using forest plots to present each study's pooled effect estimates and overall summary effects with similar individual outcomes, the results of meta-analyses were presented. Moreover, to avoid overestimating the combined study results, a random-effects model was employed. Finally, publication biases were assessed using funnel plots.

The level of statistical significance was defined at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using Review Manager (RevMan, ver. 5.4; The Cochrane Collaboration, 2020) and Stata (ver. 17; StataCorp LCC, 2021).

Results

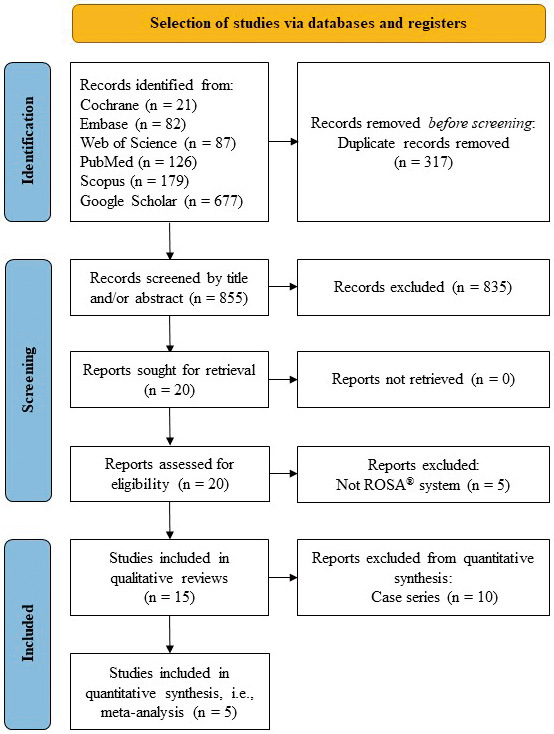

The initial search through six literature databases revealed 1,172 articles, of which 855 nonduplicate ones were evaluated for their titles and abstracts. Of these, 20 articles met the inclusion criteria and were assessed in full text. Five studies24-28) were excluded considering that they did not mention the use of the ROSAⓇ device. Thus, in the final analysis, 15 studies10,17-21,29-37) were included.

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. They originated from five countries: the United States (eight studies), Germany (three studies), France (two studies), Italy (one study), and China (one study). There were four prospective10,17,30,33) and 11 retrospective studies.18-21,29,31,32,34-37) There were no randomized control trials or studies on the comparison of ROSAⓇ with other robotic systems for SEEG electrode implantation identified. Approximately two-thirds of included studies (nine of 15) were case series of the ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation, defined as noncomparative studies.29-37) In one additional study,10) both ROSAⓇ-assisted and frame-based SEEG electrode implantation were employed, but the results of either group were not presented separately; thus, this study also was considered as noncomparative. Out of the remaining five studies, four retrospectively compared results of the ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation with a historical cohort of cases, which underwent frame-based stereotactic implantation (three studies18,20,21)) and/or navigation-assisted implantation (two studies19,21)). Finally, in their investigation González-Martínez et al.17) utilized data from their previously published study5) on frame-based stereotactic electrode implantation as a control for comparison with ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation in a prospective fashion. Hence, our systematic review is based on all 15 included studies, and a meta-analysis includes 5 comparative studies allowing for their quantitative synthesis (Fig. 1). Pediatric patients were investigated cohorts in six studies and were included in five others.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Author, year of publication | Country | Study design | Techniques of electrode implantation | Number of patients |

Number of procedures | Number of implanted electrodes | Proportion of cases with bilateral electrode implantation | Number of implanted electrodes per patient | Characteristics of patients | Operative time (min) | Total number of complications | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Proportion of women | Proportion of cases with MRI-negative epilepsy | Overall | Per electrode | ||||||||||

| Comparative studies | ||||||||||||||

| González-Martínez et al., 201617) | USA | Prospective | ROSA® | 100 | 101 | 1,245 | 35% | Mean, 12.5 Range, 5-19 |

Mean, 33.2 Range, 19-69 |

59% | 39% | Mean, 130 Range, 45-160 |

ND | 4 |

| Frame-based (Leksell) | 100 | 103 | 1,365 | ND | Mean, 13.3 | Mean, 30.9 | ND | ND | 352 | ND | 3 | |||

| Abel et al., 201818) | France | Retrospective | ROSA® | 17 | 19 | 265 | 15.8% | Mean, 14 | Mean, 11.3 Range, 3-17 |

58.8% | 41.2% | Mean, 304.71 ± 67.79 | ND | 5 |

| Frame-based (Talairach) | 18 | 19 | 264 | 21.1% | Mean, 13.9 | Mean, 11.3 Range, 3-16 |

22.2% | 22.2% | Mean, 352.47 ± 60.22 | ND | 2 | |||

| Kim et al., 202019) | USA | Retrospective | ROSA® | 25 | 25 | 257 | 64% | Mean, 10.3 Range, 4-16 |

Mean, 34 ± 8.8 | 52% | 28% | Mean, 125.5 ± 48.5 | Mean, 13.5 ± 6.2 | 4 |

| Navigation (StealthTM) | 25 | 25 | 177 | 92% | Mean, 7.1 Range, 4-12 |

Mean, 37.4 ± 10.1 | 36% | 28% | Mean, 173.4 ± 84.3 | Mean, 25.2 ± 10.3 | 4 | |||

| Machetanz et al., 202120) | Germany | Retrospective | ROSA® | 15 | 15 | 129 | ND | ND | Mean, 26.5 ± 15.7 | 53.3% | Total, 25.9% | ND | Mean, 9.1 ± 1.7 | 1 |

| Frame-based (BRW) | 12 | 12 | 91 | ND | ND | Mean, 23.2 ± 17.0 | 75% | Mean, 15.1 ± 1.9 | 0 | |||||

| Miller et al., 202121) | USA | Retrospective | ROSA® | Total, 131 | 58 | Total, 1,603 | Total, 89% | Total mean, 10.5 Total range, 1-21 |

Total mean, 39 Total range, 19-69 |

Total, 52% | Total, 50% | Mean, 136 Range, 64-276 |

Mean, 11 Range, 6-30 |

Total, 7 |

| Frame-based (CRW) | 91 | Mean, 219 Range, 23-467 |

Mean, 24 Range, 5-111 |

|||||||||||

| Navigation (VarioGuideTM) |

3 | |||||||||||||

| Noncomparative studies | ||||||||||||||

| Serletis et al., 201410) | USA | Prospectivea | ROSA® and Frame-based | 78 and 122 | 78 and 122 | 2,663 | 42% | ND | Mean, 32 Range, 3-69 |

53% | ND | ND | ND | 5 |

| De Benedictis et al., 201729) | Italy | Retrospective | ROSA® | 36 | 36 | 386 | ND | Mean, 11 Range, 6-16 |

Mean, 11.2 | ND | ND | Mean, 204.53 | ND | 0 |

| Ollivier et al., 201730) | France | Prospective | ROSA® | 66 | 66 | 857 | 51.5% | Mean, 14 Range, 6-18 |

Mean, 28 Range, 2-53 |

37.9% | 48.5% | Mean, 121 ± 48 | ND | 10 |

| Ho et al., 201831) | USA | Retrospective | ROSA® | 20 | 20 | 222 | ND | Mean, 11.1 | Mean, 10.9 ± 5.8 | 35% | 45% | Mean, 297.95 ± 52.96 | Mean, 10.98 ± 5.12 | 0 |

| McGovern et al., 201932) | USA | Retrospective | ROSA® | 57 | 64 | 791 | 36% | Mean, 12.4 ± 2.7 | Mean, 12 ± 3.6 | 56.1% | 56% | Mean, 117 ± 35 | Mean, 9.6 ± 2.4 | 7 |

| Spyrantis et al., 201833) | Germany | Prospective | ROSA® | 5 | 5 | 40 | 20% | Mean, 8 | Mean, 31 Range, 24-46 |

40% | 0 | ND | ND | 0 |

| Spyrantis et al., 201934) | Germany | Retrospectiveb | ROSA® (CT/frame) |

4 | 4 | 49 | ND | Mean, 12 Range, 10-14 |

Mean, 13 Range, 8-20 |

50% | 0 | ND | ND | 0c |

| ROSA® (CT/laser) |

7 | 7 | 60 | ND | Mean, 9 Range, 5-11 |

Mean, 32 Range, 21-43 |

57.1% | 0 | ND | ND | 3c | |||

| ROSA® (3.0T MRI/laser) |

7 | 7 | 56 | ND | Mean, 8 Range, 6-10 |

Mean, 34 Range, 27-46 |

42.9% | 0 | ND | ND | 1c | |||

| ROSA® (1.5T MRI/laser) |

1 | 1 | 6 | ND | 6 | 24 | 100% | 0 | ND | ND | 0c | |||

| Nelson et al., 202035) | USA | Retrospective | ROSA® | 19 | 23 | 148 | ND | Mean, 6 ± 3 | Mean, 13 ± 5 | 26% | ND | Mean, 148 ± 60 | ND | 0 |

| Bonda et al., 202136) | USA | Retrospective | ROSA® | 23 | 23 | 261 | 21.7% | Mean, 11 Range, 5-21 |

Mean, 11.7 ± 6.1 | 47.8% | 43.5% | ND | Mean, 6.56 ± 3.48 | 0 |

| Lu et al., 202137) | China | Retrospective | ROSA® | 39 | 39 | 322 | ND | ND | Mean, 19 Range, 2-35 |

53.8% | ND | ND | ND | ND |

BRW, Brown-Roberts-Wells stereotactic frame; CRW, Cosman-Roberts-Wells stereotactic frame; Leksell, Leksell stereotactic frame; Talairach, Talairach stereotactic system; ND, no data

aThis study was not considered comparative, because it did not present the results in each group separately.

bThis study compared the accuracy of several methods of ROSA®-assisted stereoelectroencephalography electrode implantation with the use of different imaging modalities (CT vs. 1.5T MRI vs. 3.0T MRI) and registration techniques (frame-based vs. surface laser scanning).

cIn this study, the total number of complications was 6, but two cases of broken guidance screws were not assigned to specific subgroups.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the systematic review and meta-analysis.

The average MINORS scores were 12.6 (range, 10-14) out of a maximum of 24 points and 8.7 (range, 6-11) out of a maximum of 16 points for comparative and noncomparative studies, respectively, which suggests significant methodological flaws (Table 2). Specifically, none of the included studies explicitly presented the unbiased assessment of outcomes as a blind or nonblind evaluation, nor did they provide information on the prospective sample size calculation.

Table 2.

Methodological index for nonrandomized studies (MINORS) for assessing the quality of included studies

| Author, year of publication | Items for all nonrandomized studies | Items for comparative studies | Total score | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clearly stated aim | Inclusion of consecutive patients | Prospective data collection | Appropriate endpoints | Unbiased assessment endpoints | Appropriate follow-up perioda | Loss follow-up <5% | Prospective calculation of study size | Adequate control group | Contemporary groups | Baseline equivalence of groups | Adequate statistical analysis | ||

| Comparative studies | |||||||||||||

| González-Martínez et al., 201617) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| Abel et al., 201818) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 11 |

| Kim et al., 202019) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| Machetanz et al., 202120) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 |

| Miller et al., 202121) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10 |

| Noncomparative studies | |||||||||||||

| Serletis et al., 201410) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | 8 | |||

| De Benedictis et al., 201729) | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | 9 | |||

| Ollivier et al., 201730) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | - | 11 | |||

| Ho et al., 201831) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | - | 9 | |||

| McGovern et al., 201932) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | 8 | |||

| Spyrantis et al., 201833) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | - | 10 | |||

| Spyrantis et al., 201934) | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | - | 8 | |||

| Nelson et al., 202035) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | - | 6 | |||

| Bonda et al., 202136) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | - | 9 | |||

| Lu et al., 202137) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | - | 9 | |||

Score 0 (not reported), 1 (reported but inadequate), and 2 (reported and adequate). The maximum total score is 24 for comparative studies and 16 for noncomparative studies.

aIn the present systematic review and meta-analysis, an appropriate follow-up period was defined as >12 months.

Number of implanted electrodes and technique of implantation

In total, included studies reported on 11,257 SEEG electrode implantations. The average number of implanted electrodes per patient in 12 studies, which provided this information, was 10.6 (range, 1-21). The proportion of cases with bilateral electrode implantations in nine studies, which provided this information, ranged from 15.8% to 92%. The number of implanted electrodes with the use of ROSAⓇ device remained unknown in two studies,10,21) which did not provide information on different subgroups of patients separately, whereas it was 5,094 in 13 other studies.

Planning of electrode implantation was usually conducted on the basis of MRI, which in some centers was combined with computed tomography (CT), DynaCT, and/or digital subtraction angiography (DSA) data. Skull fixation during the procedure was usually achieved either with a stereotactic frame or with a Mayfield clamp (the latter method was more frequently employed in recent studies). Registration with face and head surface laser scanning was applied much more often than that with the skull or scalp fiducial markers.

Accuracy of electrode implantation

In total, 10 of 15 studies reported on the accuracy of ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation based on measurements of Euclidian distance to assess the error between planned and actual entry and/or target points (Table 3). Overall, in cases of ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation, the cumulative mean entry point error was 1.80 mm (95% CI from 1.33 to 2.28 mm), and the cumulative mean target point error was 2.73 mm (95% CI from 2.26 to 3.19 mm).

Table 3.

Procedural details and electrode implantation accuracy of included studies

| Author, year of publication | Techniques of electrode implantation | Preoperative imaging | Skull fixation | Registration | Postoperative imaging | Entry point error (mm) a | Target point error (mm) a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative studies | |||||||

| González-Martínez et al., 201617) | ROSA® | MRI, CT, DSA | Leksell frame | Laser-based facial recognition | DynaCT | Median, 1.2 IQR, 0.78, 1.83 |

Median, 1.7 IQR, 1.2, 2.3 |

| Frame-based (Leksell) | MRI, CT, DSA | Leksell frame | Coregistration with iPlan® cranial software (Brainlab) | DynaCT | Median, 1.1 | ND | |

| Abel et al., 201818) | ROSA® | MRI, CT, DSA | Stereotactic frame | Five bone fiducials | O-arm CT | ND | ND |

| Frame-based (Talairach) | SEEG electrode implantation using Talairach stereotactic system (no other procedural details have been provided) |

||||||

| Kim et al., 202019) | ROSA® | MRI, CT | Stereotactic frame | Facial recognition or fiducial-based registration | O-arm CT | Mean, 1.39 ± 0.75 | Mean, 3.05 ± 2.02 |

| Navigation (StealthTM) | MRI, CT | Stereotactic frame | Skull fiducial or autoregistration using O-arm, StealthTM navigation system (Medtronic) |

O-arm CT | ND | ND | |

| Machetanz et al., 202120) | ROSA® | MRI, CT | Mayfield clamp | Five bone fiducials | MRI or CT | Mean, 0.7 ± 0.5 | Mean, 1.6 ± 0.8 |

| Frame-based (BRW) | MRI, CT | BRW frame | Coregistration with iPlan® cranial software (Brainlab) | MRI or CT | Mean, 1.5 ± 0.6 | Mean, 1.5 ± 0.8 | |

| Miller et al., 202121) | ROSA® | MRI | ND | ND | CT | ND | ND |

| Frame-based (CRW) | MRI | CRW frame | ND | CT | |||

| Navigation (VarioGuideTM) |

MRI | ND | VarioGuideTM navigation system (Brainlab) | CT | |||

| Noncomparative studies | |||||||

| Serletis et al., 201410) | ROSA® | MRI, DynaCT, DSA | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Frame-based | MRI, DynaCT, DSA | Leksell frame | Coregistration with iPlan® cranial software (Brainlab) | DynaCT | ND | ND | |

| De Benedictis et al., 201729) | ROSA® | MRI, CT | 3-pin support | Surface laser registration | CT or MRI | Mean, 1.59 ± 1.1 | Mean, 2.22 ± 1.71 |

| Ollivier et al., 201730) | ROSA® | MRI | Mayfield clamp | Surface laser registration | CT | Mean, 1.62 ± 1.8 | Mean, 2.66 ± 2.3 |

| Ho et al., 201831) | ROSA® | MRI, CT | Mayfield clamp | Surface laser registration | CT | ND | Mean, 3.39 ± 1.08 |

| McGovern et al., 201932) | ROSA® | MRI, CTA | Leksell frame | Surface laser registration | CT | ND | ND |

| Spyrantis et al., 201833) | ROSA® | MRI | Mayfield clamp | Surface laser registration | CT | Mean, 2.96 ± 0.24 | Mean, 2.53 ± 0.23 |

| Spyrantis et al., 201934) | ROSA® (CT/frame) |

MRI, CT | Leksell frame | Robotic arm pointer probe based on CT | MRI | Mean, 0.86 ± 0.51 | Mean, 2.28 ± 1.33 |

| ROSA® (CT/laser) |

MRI, CT | Mayfield clamp | Surface laser registration based on CT | CT | Mean, 1.85 ± 0.84 | Mean, 2.41 ± 1.34 | |

| ROSA® (3.0T MRI/laser) |

MRI | Mayfield clamp | Surface laser registration based on 3.0T MRI | CT | Mean, 3.02 ± 1.35 | Mean, 3.51 ± 1.48 | |

| ROSA® (1.5T MRI/laser) |

MRI | Mayfield clamp | Surface laser registration based on 1.5T MRI | CT | Mean, 0.97 ± 0.70 | Mean, 1.71 ± 0.65 | |

| Nelson et al., 202035) | ROSAr | MRI, CT | Mayfield clamp or Leksell frame | Surface laser registration | CT or MRI | ND | ND |

| Bonda et al., 202136) | ROSA® | 3D printed model | Mayfield clamp | ND | CT | Mean, 2.52 ± 2.20 | Mean, 4.58 ± 3.47 |

| Lu et al., 202137) | ROSA® | MRI, CT | Mayfield clamp or Leksell frame | Surface laser registration or scalp fiducial markers | CT | Mean, 2.2 ± 7.61b | Mean, 2.57 ± 1.70b |

3D, three-dimensional; BRW, Brown-Roberts-Wells stereotactic frame; CRW, Cosman–Roberts–Wells stereotactic frame; CTA, computed tomography angiography; DSA, digital subtraction angiography; IQR, interquartile range; Leksell, Leksell stereotactic frame; ND, no data

aEntry and target points error calculation was based on measurements of Euclidian distance between their planned and actual location.

bThese results are derived from a subgroup (n = 61) of multilobe-spanning stereoelectroencephalography electrodes with a length of >70 mm.

Out of 10 studies reporting on accuracy, three were comparative, and two17,20) provided separate data for ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation and frame-based stereotactic technique, but highlighted either median or mean values (one study each). One other comparative study19) did not provide results on accuracy in a control subgroup of navigation-assisted implantation. The remaining seven studies were noncomparative. Owing to the limited number of comparative studies and methodological discrepancy in reporting data, creating combined error values for other electrode implantation techniques was not possible. Thus, a forest plot to compare accuracy findings was not carried out.

Operative time

Operative time (overall, per electrode, or both) was reported in all comparative and six of 10 noncomparative studies. For ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation, the mean lengths of overall operative time varied widely (range, 117-304.71 min), whereas the mean lengths of operative time per implanted electrode were more homogeneous (range, 6.56-13.5 min).

In total, three comparative studies18,19,21) reported data on overall operative time, and two19,20) reported data on operative time per electrode, providing information separately in varied subgroups of patients. Meta-analysis revealed that compared with other techniques, ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation provided a statistically significant reduction (Fig. 2) of both overall operative time (MD, −63.45 min; 95% CI from −88.73 to −38.17 min; P < 0.00001; I2 = 38%) and operative time per implanted electrode (MD, −8.79 min; 95% CI from −14.37 to −3.21 min; P = 0.002; I2 = 98%).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of operative time differences between various techniques of stereoelectroencephalography electrode implantation. The use of ROSA® provided a statistically significant reduction of both overall operative time (A) and operative time per implanted electrode (B).

Complications

Perioperative complications of SEEG electrode implantations were reported in 14 of 15 included studies (Supplementary Material; Table S4). For 416 ROSAⓇ-assisted procedures with 4,772 SEEG electrode implantations, a total of 37 complications were observed (on average, one complication for every 11.2 procedures or for every 129 implanted electrodes). Among these events, intracerebral hemorrhage was the most common (32 of 37 cases; 86.5%). Notably, there were no complications in five studies.29,31,33,35,36)

Overall, four comparative studies17-20) reported data on rates of any complications and intracerebral hemorrhage, and provided data separately in varied subgroups of patients. Meta-analysis showed no significant differences (Fig. 3) between ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation and other techniques in rates of either any complications (RR, 1.48; 95% CI from 0.67 to 3.24; P = 0.33; I2 = 0%) or intracerebral hemorrhage (RR, 1.56; 95% CI from 0.69 to 3.55; P = 0.29; I2 = 0%). Considering that the number of other complications was small, a quantitative comparative analysis of their rates could not be conducted.

Fig. 3.

Forest plots of perioperative complication rates between various techniques of stereoelectroencephalography electrode implantation. The use of ROSA® was not associated with a significantly different number of complications (A) or intracerebral hemorrhage (B).

Seizure outcomes

Details of further treatment following SEEG electrode implantation with or without highlighting seizure outcomes were provided in 13 of 15 studies; however, these data were presented inconsistently, complicating their precise synthesis and analysis (Supplementary Material; Table S5).

For 332 patients who underwent ROSAⓇ-assisted depth electrode implantation, the proportion of cases with subsequent SEEG-guided resections in nine studies, which provided this information, ranged from 57.9% to 95%. In addition to focal resective surgery, other interventions were applied, which include thermocoagulation, responsive neurostimulation, hemispherectomy/hemispherotomy, corpus callosotomy, vagus nerve stimulation, laser-induced thermotherapy, and their various combinations. Seizure outcomes were usually presented regardless of applied intervention. For cases of ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation, the proportion of Engel Class I outcomes (i.e., freedom from seizures) was reported in seven studies (261 patients) and ranged from 21% to 67%.

In total, three comparative studies17-19) reported data on seizure outcomes following SEEG-guided resection after depth electrode implantation separately in various subgroups of patients. Meta-analysis showed no significant differences (Fig. 4) between ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation and other techniques in terms of proportion of subsequent SEEG-guided resections (RR, 0.94; 95% CI from 0.82 to 1.07; P = 0.32; I2 = 0%) and attainment of the Engel Class I outcome (RR, 1.01; 95% CI from 0.79 to 1.30; P = 0.61; I2 = 0%).

Fig. 4.

Forest plots of proportions of cases with subsequent stereoelectroencephalography-guided resections (A) and Engel Class I outcomes (B) do not demonstrate significant differences between various techniques of depth electrode implantation.

Publication bias

Publication bias assessment with funnel plots (Supplementary Material; Figures S6.1-S6.5; Tables S6.1-S6.5) showed asymmetrical distribution for evaluation of the difference in operative time per electrode between ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation and other techniques, which may reflect high heterogeneity (I2 = 98%). For other conducted meta-analyses, there were no evident publication biases disclosed.

Discussion

Since recently, implantation of SEEG electrodes with the utilization of various robotic systems has been routinely employed for both adult and pediatric patients in neurosurgical centers globally.10-16) To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the ROSAⓇ device concerning accuracy of depth electrode placement, operative time, perioperative complication rates, and seizure outcomes, the presented systematic review and meta-analysis has been specifically directed.

Accuracy of electrode implantation

Accurate placement of SEEG electrodes during clinical evaluation of patients with drug-resistant seizures prior to consideration of possible surgical treatment is a crucial prerequisite for precisely localizing the epileptogenic zone and epileptic focus.38) Nonetheless, there is still no standardized definition of implantation accuracy, and for its assessment, different methods have been applied. In most cases, measurements of Euclidian distance were utilized to define errors between planned and actual locations of entry and target points; however, occasionally, assessments of depth error, two-dimensional radial error, and angular deviation were also conducted.19,31,37)

The use of robotic systems is believed to enhance the precision and accuracy of SEEG electrode implantation.10-16,39) Indeed, once the trajectory for implantation has been set, the rigidity of the robotic arm reduces involuntary movement, which decreases human error. In their meta-regression analysis, Philipp et al.40) demonstrated that robot-assisted stereotactic procedures lessen target error. Our study showed that in cases of ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation, the cumulative mean entry point and target point errors consist of 1.80 and 2.73 mm, respectively. It is larger than similar values underscored in the previous report of Vakharia et al.39) on the combined accuracy of robotic trajectory guidance, who found a mean entry point error of 1.17 mm and a mean target point error of 1.71 mm. Nevertheless, a direct comparison of different studies is hardly possible, considering that multiple confounding factors may affect the accuracy of electrode implantation. In particular, misregistration of the neuronavigation system, inaccurate alignment, and skull drilling deflection may increase entry point errors, whereas suboptimal angle of trajectory, intracranial deflection of the implanted electrode, and inappropriate depth of the introducer insertion may increase target point errors.39,41) Imaging modalities and registration techniques should also be considered. Spyrantis et al.34) compared the accuracy of several methods of ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation and found that registration with CT provides results that could be compared to 1.5T MRI and are more accurate than 3.0T MRI. Additionally, they noted that with the use of CT, frame-based referencing was associated with smaller entry point errors in comparison to facial laser scanning, whereas the difference for target point errors did not reach the level of statistical significance.34)

Previously, Vakharia et al.39) presented higher accuracy of depth electrode placement with the application of robotic devices compared with frame-based implantation. In accordance, several studies demonstrated that entry point and target point errors are at least comparable between ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation and other frame-based methods.17,20) Unfortunately, integrated evaluation of these data in our meta-analysis was not possible because of the limited number of comparative studies and methodological discrepancy in reporting data. Hence, additional research work should be directed at this important issue, whereas there is a high possibility that the use of ROSAⓇ device allows for increased accuracy of SEEG electrode implantation compared with conventional frame-based or navigation-assisted techniques.

Operative time

The statistically significant positive impact of the ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation on the reduction of both overall operative time and operative time per implanted electrode is the main finding of this meta-analysis. Although lengths of overall operative time varied widely between individual studies (which most probably reflected the different number of implanted electrodes and/or variable methodology of operative time recordings), lengths of operative time per implanted electrode were homogeneous. These results are in line with previous reports on such an effect with the usage of other robotic systems for depth electrode implantation.28,42,43)

The reduction of operative time with the utilization of intraoperative robotics may be related to several reasons. First, the trajectory of electrode implantation in such cases is created not intraoperatively but prior to surgery. Likewise, a rehearsal of electrode implantation can be conducted before intervention on the 3D-printed model of the skull,44) which may be helpful for complex cases that require the application of multiple electrodes, especially in pediatric patients. Second, a robotic arm allows for five to six degrees of freedom, providing exceptional dexterity and flexibility to access surgical sites, which can also result in faster procedures. Finally, haptic technology generates a seamless interface between the surgeon and the robotic device, such as ROSAⓇ, which also helps to improve his or her performance during the intervention.11,45)

Complications

The main concerns in terms of SEEG monitoring have been related to potential complications of the depth electrode implantation, either surgical (intracerebral hemorrhage, neurological deficit, and infection) or technical (broken guidance screw and retained electrode). Nevertheless, our study revealed that the risk of such adverse events after ROSAⓇ-assisted procedures is low and comprised, on average, one complication per 129 implanted electrodes. Moreover, notably, as a minimally invasive technique, SEEG with implantation of depth electrodes is associated with a much lower rate of perioperative hemorrhage, infection, and intracranial hypertension in comparison to craniotomy with placement of subdural grid/strip electrodes.8,46)

Nonetheless, based on our data, among various adverse events intracerebral hemorrhage was the most common and amounted to 86.5% of all complications. McGovern et al.47) investigated hemorrhage rates in three groups of patients, who underwent SEEG electrode implantation via (1) Leksell frame-based stereotactic technique with referencing to DSA, (2) ROSAⓇ-assisted technique with referencing to MRI, and (3) ROSAⓇ-assisted technique with referencing to CT angiography (CTA). Based on the results of that study, robot-assisted SEEG electrode implantation was not associated with a significantly different rate of hemorrhagic events compared with conventional frame-based technique. Although cases with reference to MRI displayed slightly higher total and symptomatic hemorrhage rates, statistical analysis did not present significant differences.47) Still, since hemorrhage during insertion of electrodes is mainly due to direct injury of superficial or deep cerebral vessels, integration of DSA, CTA, or magnetic resonance angiography into the planning of the implantation trajectories may serve as a simple and effective primary preventive measure for this complication. Apparently, the risk of hemorrhage is associated with the number of electrodes placed during the procedure.

In line with previous reports,17-20,47) our meta-analysis did not reveal statistically significant differences in rates of any complications or intracerebral hemorrhage between ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation and other techniques. Nevertheless, these results basically relied on retrospective studies of low-to-moderate quality. Prospective comparative evaluation of complication rates after robot-assisted SEEG electrode implantation is necessary, since it may allow for the optimization of the procedure and enhancement of its safety.

Seizure outcomes

Predicting the epilepsy surgery success at the individual level is a complex and multifaceted task. Multiple demographic, clinical, imaging, electrophysiological, and histopathological factors should be considered, and their integration is a pivotal element during clinical decision making on the selection of the optimal surgical candidates. Specifically, a well-defined and clearly circumscribed epileptogenic zone located in a non-eloquent brain area, allowing for its complete resection, is an essential predictor of optimal postoperative seizure outcomes. Thus, precise identification of the epileptogenic zone is extremely important. Therefore, SEEG represents an invaluable tool, which is particularly effective in complex cases with unclear lateralization of the epileptic focus, bilateral or multifocal origin of seizures, nonconcordant results of noninvasive studies (scalp EEG, MRI, 1H-MRS, and PET), extension of the epileptogenic zone on eloquent brain structures, or necessity for detailed characterization of the relevant epileptic neuronal networks.5)

Based on our data, ROSAⓇ-assisted depth electrode implantation was followed by SEEG-guided epilepsy surgery in 57.9%-95% of patients, but this proportion does not vary significantly in comparison with other techniques of depth electrode implantation. It may indicate that although SEEG itself is an important method for clinical decision making in terms of surgical treatment and prediction of its success, the applied technique of depth electrode implantation is somewhat less important. Indeed, the efficacy of epileptogenic zone localization obviously is dependent not only on the precision and safety of SEEG electrode positioning but accurate preimplantation hypothesis of seizure origin and propagation. Likewise, attainment of the Engel Class I outcome following SEEG-guided resections was similar after depth electrode implantation with the utilization of different techniques. Notably, however, the comparison of different groups included in our systematic review is challenging because of the heterogeneity of pathologies (specifically, differing proportions of cases with MRI-negative epilepsy), patient characteristics, other applied treatment modalities, and so forth. Additionally, evaluation of seizure outcomes following SEEG-guided resection was complicated by the variability of treatment strategies, frequent reporting on results irrespective of applied intervention, and variable length of follow-up in different series. Thus, the impact of ROSAⓇ and other robotic systems used for SEEG electrode implantation on choice of treatment strategy in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy and overall seizure outcomes necessitates further clarification.

Other important issues

Despite the potential benefits of ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation emphasized, several important issues have remained outside the scope of this study.

Acquiring proficiency in the use of ROSAⓇ device may be challenging, time-consuming, and somewhat costly. Practice with such a robotic system is associated with a definite learning curve, reflecting the interrelationship between the level of one's surgical experience and proficiency in performing the procedure. Because of its relevance to efficacy, performance, and surgeon-related safety, understanding the learning curve is necessary.48) McGovern et al.47) showed that mastery of the robotic technique for SEEG electrode implantations took much longer than of the frame-based technique, with the operative time peaking at 75 cases and plateauing at 150 cases for the former versus 25 cases and 10 cases for the latter. Nonetheless, the transition to the new technique significantly reduced operative time (196 vs. 115 min) and the number of hemorrhagic complications and increased implantation accuracy.47) Thus, by monitoring the learning curve associated with robot-assisted SEEG electrode implantation and proactive managing the potential risks, the quality of care and treatment safety for patients with epilepsy can be improved. Strategies for minimizing the effects of the learning curve in concordance with ethical considerations must also be developed, specifically if the risk of adverse events and technical failures associated with the application of new techniques exceeds those in standard surgical approaches.49)

Moreover, notably, the cost of the ROSAⓇ device is high, making it hardly affordable for low- and middle-income countries. Additionally, maintenance of the device requires a strong supporting team, the service of which may also necessitate additional funding. Generally, cost-benefit performance of robotic systems for SEEG electrode implantation definitely requires thorough investigation.

Study limitations

This systematic review and meta-analysis has several methodological limitations. First, although a literature search was conducted based on PRISMA guidelines with the use of multiple databases, search terms and their combinations were selected arbitrarily. Second, although strict inclusion and exclusion criteria allowed the selection of a highly homogeneous group of studies dedicated to the technique under investigation (ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation), their overall number was too small. Third, the entire analysis is based on noncomparative case series and retrospective comparative studies of low-to-moderate quality, in which evaluation with MINORS suggested methodological flaws. Fourth, included studies occasionally showed discrepancies in reporting results, which complicated data synthesis for further statistical analysis. Fifth, a limited number of comparative studies deterred a comprehensive evaluation of the electrode implantation accuracy and reduced the statistical power of performed meta-analyses, potentially leading to an overestimation of the effect size. Sixth, the absence of control over confounding variables in included studies might influence the results of performed meta-analyses. Seventh, meta-regression analysis for identification of potential sources of heterogeneity among the included studies was not carried out. Finally, developments of operative techniques over time and the learning curve of the ROSAⓇ device use were not assessed. During the interpretation and extrapolation of presented findings, all these issues should be considered.

Conclusions

The presented systematic review and meta-analysis provides level 3 evidence that compared with other frame-based or navigation-assisted techniques, the use of ROSAⓇ-assisted SEEG electrode implantation in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy leads to a significant reduction of both overall operative time and operative time per implanted electrode, is not accompanied by a higher risk of perioperative complications (specifically, intracerebral hemorrhage) and has no negative impact on seizure outcomes after subsequent SEEG-guided epilepsy surgery. These data confirm the effectiveness and safety of the ROSAⓇ device and favor its use in clinical practice. Nonetheless, given that our analysis is based on the small number of available noncomparative case series and retrospective comparative studies of low-to-moderate quality, the findings should be carefully accepted and require additional confirmation. Furthermore, future research should be directed at the evaluation of the electrode implantation accuracy with the comparison of conventional techniques and varying robotic systems, which should be preferably realized within well-designed prospective, randomized, and multiinstitutional trials.

Grant Support

None. The authors do not have any personal or institutional financial interests in drugs, materials, or devices described in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest Disclosure

Neither author has any actual or potential conflicts of interest related to this study. All Japan Neurosurgical Society (JNS) member authors (MC, SY, and YK) have registered online self-reported COI Disclosure Statement Forms via the JNS website.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

At the time of this study, Dr. Anukoon Kaewborisutsakul from Prince of Songkla University (Songkhla, Thailand) had an International Clinical Training Fellowship in Epilepsy Neurosurgery at the Department of Neurosurgery, Tokyo Women's Medical University Adachi Medical Center (Tokyo, Japan), under the sponsorship of Takeda Science Foundation.

References

- 1). Fiest KM, Sauro KM, Wiebe S, et al. : Prevalence and incidence of epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of international studies. Neurology 88: 296-303, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Beghi E: The epidemiology of epilepsy. Neuroepidemiology 54: 185-191, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Kalilani L, Sun X, Pelgrims B, Noack-Rink M, Villanueva V: The epidemiology of drug-resistant epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia 59: 2179-2193, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Rosenow F, Lüders H: Presurgical evaluation of epilepsy. Brain 124: 1683-1700, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Gonzalez-Martinez J, Bulacio J, Alexopoulos A, Jehi L, Bingaman W, Najm I: Stereoelectroencephalography in the “difficult to localize” refractory focal epilepsy: early experience from a North American epilepsy center. Epilepsia 54: 323-330, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Isnard J, Taussig D, Bartolomei F, et al. : French guidelines on stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG). Neurophysiol Clin 48: 5-13, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Chauvel P: The history and principles of stereo EEG. In: A Practical Approach to Stereo EEG. Schuele SU, Ed. Demos Medical Publishing, Springer Publishing Company, LLC, New York, 2021: 3-11 [Google Scholar]

- 8). Mullin JP, Shriver M, Alomar S, et al. : Is SEEG safe? A systematic review and meta-analysis of stereo-electroencephalography-related complications. Epilepsia 57: 386-401, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Garcia-Lorenzo B, del Pino-Sedeño T, Rocamora R, López JE, Serrano-Aguilar P, Trujillo-Martín MM: Stereoelectroencephalography for refractory epileptic patients considered for surgery: systematic review, meta-analysis, and economic evaluation. Neurosurgery 84: 326-338, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Serletis D, Bulacio J, Bingaman W, Najm I, González-Martínez J: The stereotactic approach for mapping epileptic networks: a prospective study of 200 patients. J Neurosurg 121: 1239-1246, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Fomenko A, Serletis D: Robotic stereotaxy in cranial neurosurgery: a qualitative systematic review. Neurosurgery 83: 642-650, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Tandon N, Tong BA, Friedman ER, et al. : Analysis of morbidity and outcomes associated with use of subdural grids vs stereoelectroencephalography in patients with intractable epilepsy. JAMA Neurol 76: 672-681, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Rollo PS, Rollo MJ, Zhu P, Woolnough O, Tandon N: Oblique trajectory angles in robotic stereo-electroencephalography. J Neurosurg 135: 245-254, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). Stumpo V, Staartjes VE, Klukowska AM, et al. : Global adoption of robotic technology into neurosurgical practice and research. Neurosurg Rev 44: 2675-2687, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Kojima Y, Uda T, Kawashima T, et al. : Primary experiences with robot-assisted navigation-based frameless stereo-electroencephalography: higher accuracy than neuronavigation-guided manual adjustment. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 62: 361-368, 2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Maesawa S, Ishizaki T, Mutoh M, et al. : Clinical impacts of stereotactic electroencephalography on epilepsy surgery and associated issues in the current situation in Japan. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 63: 179-190, 2023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). González-Martínez J, Bulacio J, Thompson S, et al. : Technique, results, and complications related to robot-assisted stereoelectroencephalography. Neurosurgery 78: 169-180, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Abel TJ, Varela Osorio R, Amorim-Leite R, et al. : Frameless robot-assisted stereoelectroencephalography in children: technical aspects and comparison with Talairach frame technique. J Neurosurg Pediatr 22: 37-46, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Kim LH, Feng AY, Ho AL, et al. : Robot-assisted versus manual navigated stereoelectroencephalography in adult medically-refractory epilepsy patients. Epilepsy Res 159: 106253, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Machetanz K, Grimm F, Wuttke T, et al. : Frame-based and robot-assisted insular stereo-electroencephalography via an anterior or posterior oblique approach. J Neurosurg 135: 1477-1486, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Miller C, Schatmeyer B, Landazuri P, et al. : sEEG for expansion of a surgical epilepsy program: safety and efficacy in 152 consecutive cases. Epilepsia Open 6: 694-702, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. : The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med 18: e1003583, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J: Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg 73: 712-716, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Bourdillon P, Châtillon CE, Moles A, et al. : Effective accuracy of stereoelectroencephalography: robotic 3D versus Talairach orthogonal approaches. J Neurosurg 131: 1938-1946, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Sharma JD, Seunarine KK, Tahir MZ, Tisdall MM: Accuracy of robot-assisted versus optical frameless navigated stereoelectroencephalography electrode placement in children. J Neurosurg Pediatr 23: 297-302, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Zhao R, Xue P, Zhou Y, et al. : Application of robot-assisted frameless stereoelectroencephalography based on multimodal image guidance in pediatric refractory epilepsy: experience of a pediatric center in a developing country. World Neurosurg 140: e161-e168, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Zheng J, Liu Y, Zhang D, et al. : Robot-assisted versus stereotactic frame-based stereoelectroencephalography in medically refractory epilepsy. Neurophysiol Clin 51: 111-119, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Yao Y, Hu W, Zhang C, et al. : A comparison between robot-guided and stereotactic frame-based stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG) electrode implantation for drug-resistant epilepsy. J Robot Surg 17: 1013-1020, 2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). De Benedictis A, Trezza A, Carai A, et al. : Robot-assisted procedures in pediatric neurosurgery. Neurosurg Focus 42(5): E7, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Ollivier I, Behr C, Cebula H, et al. : Efficacy and safety in frameless robot-assisted stereo-electroencephalography (SEEG) for drug-resistant epilepsy. Neurochirurgie 63: 286-290, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Ho AL, Muftuoglu Y, Pendharkar AV, et al. : Robot-guided pediatric stereoelectroencephalography: single-institution experience. J Neurosurg Pediatr 22: 1-8, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). McGovern RA, Knight EP, Gupta A, et al. : Robot-assisted stereoelectroencephalography in children. J Neurosurg Pediatr 23: 288-296, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Spyrantis A, Cattani A, Strzelczyk A, Rosenow F, Seifert V, Freiman TM: Robot-guided stereoelectroencephalography without a computed tomography scan for referencing: analysis of accuracy. Int J Med Robot 14: e1888, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Spyrantis A, Cattani A, Woebbecke T, et al. : Electrode placement accuracy in robot-assisted epilepsy surgery: a comparison of different referencing techniques including frame-based CT versus facial laser scan based on CT or MRI. Epilepsy Behav 91: 38-47, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Nelson JH, Brackett SL, Oluigbo CO, Reddy SK: Robotic stereotactic assistance (ROSA) for pediatric epilepsy: a single-center experience of 23 consecutive cases. Children (Basel) 7(8): 94, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). Bonda DJ, Pruitt R, Theroux L, et al. : Robot-assisted stereoelectroencephalography electrode placement in twenty-three pediatric patients: a high-resolution analysis of individual lead placement time and accuracy at a single institution. Childs Nerv Syst 37: 2251-2259, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37). Lu C, Chen S, An Y, et al. : How can the accuracy of SEEG be increased? - an analysis of the accuracy of multilobe-spanning SEEG electrodes based on a frameless stereotactic robot-assisted system. Ann Palliat Med 10: 3699-3705, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Jayakar P, Gotman J, Harvey AS, et al. : Diagnostic utility of invasive EEG for epilepsy surgery: indications, modalities, and techniques. Epilepsia 57: 1735-1747, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39). Vakharia VN, Sparks R, O'Keeffe AG, et al. : Accuracy of intracranial electrode placement for stereoelectroencephalography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia 58: 921-932, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40). Philipp LR, Matias CM, Thalheimer S, Mehta SH, Sharan A, Wu C: Robot-assisted stereotaxy reduces target error: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of 6056 trajectories. Neurosurgery 88: 222-233, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41). Cardinale F, Cossu M, Castana L, et al. : Stereoelectroencephalography: surgical methodology, safety, and stereotactic application accuracy in 500 procedures. Neurosurgery 72: 353-366, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42). Vakharia VN, Rodionov R, Miserocchi A, et al. : Comparison of robotic and manual implantation of intracerebral electrodes: a single-centre, single-blinded, randomised controlled trial. Sci Rep 11: 17127, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43). Hines K, Matias CM, Leibold A, Sharan A, Wu C: Accuracy and efficiency using frameless transient fiducial registration in stereoelectroencephalography and deep brain stimulation. J Neurosurg 138: 299-305, 2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44). Bonda DJ, Pruitt R, Goldstein T, et al. : Robotic surgical assistant (ROSA™) rehearsal: using 3-dimensional printing technology to facilitate the introduction of stereotactic robotic neurosurgical equipment. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 19: 94-97, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45). Ball T, González-Martínez J, Zemmar A, et al. : Robotic applications in cranial neurosurgery: current and future. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 21: 371-379, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46). Sacino MF, Huang SS, Schreiber J, Gaillard WD, Oluigbo CO: Is the use of stereotactic electroencephalography safe and effective in children? A meta-analysis of the use of stereotactic electroencephalography in comparison to subdural grids for invasive epilepsy monitoring in pediatric subjects. Neurosurgery 84: 1190-1200, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47). McGovern RA, Butler RS, Bena J, Gonzalez-Martinez J: Incorporating new technology into a surgical technique: the learning curve of a single surgeon's stereo-electroencephalography experience. Neurosurgery 86: E281-E289, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48). Shlobin NA, Huang J, Wu C: Learning curves in robotic neurosurgery: a systematic review. Neurosurg Rev 46: 14, 2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49). Vilanilam GC, Venkat EH: Ethical nuances and medicolegal vulnerabilities in robotic neurosurgery. Neurosurg Focus 52(1): E2, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.