Abstract

Rationale:

Despite the increasingly pervasive use of chemogenetic tools in preclinical neuroscience research, the in vivo pharmacology of DREADD agonists remains poorly understood. The pharmacological effects of any ligand acting at receptors, engineered or endogenous, are influenced by numerous factors including potency, time course, and receptor selectivity. Thus, rigorous comparison of the potency and time course of available DREADD ligands may provide an empirical foundation for ligand selection.

Objectives:

Compare the behavioral pharmacology of three different DREADD ligands clozapine-N-oxide (CNO), compound 21 (C21), and deschloroclozapine (DCZ) in a locomotor activity assay in tyrosine hydroxylase:cre recombinase (TH:Cre) male and female rats.

Methods:

Locomotor activity in nine adult TH:Cre Sprague-Dawley rats (5 female, 4 male) was monitored for two hours following administration of d-amphetamine (vehicle, 0.1–3.2 mg/kg, IP), DCZ (vehicle, 0.32–320 μg/kg, IP), CNO (vehicle, 0.32–10 mg/kg), and C21 (vehicle, 0.1–3.2 mg/kg, IP). Behavioral sessions were conducted twice per week prior to and starting three weeks after bilateral intra-VTA hM3Dq DREADD virus injection.

Results:

d-Amphetamine significantly increased locomotor activity pre- and post-DREADD virus injection. DCZ, CNO, and C21 did not alter locomotor activity pre-DREADD virus injection. There was no significant effect of DCZ, CNO, and C21 on locomotor activity post-DREADD virus injection; however, large individual differences in both behavioral response and receptor expression were observed.

Conclusions:

Large individual variability was observed in both DREADD agonist behavioral effects and receptor expression. These results suggest further basic research would facilitate the utility of these chemogenetic tools for behavioral neuroscience research.

Keywords: clozapine N-oxide, compound 21, deschloroclozapine, DREADD, TH:Cre rats, locomotor activity

1.0. Introduction

Chemogenetics refers to the use of engineered receptors designed to be activated by a selective ligand such as Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADDs). Since the introduction of DREADDs in 2007 [1], chemogenetics have provided multiple new tools to facilitate behavioral neuroscience research by affording more selective manipulation of specific neurotransmitter systems or subpopulations of neurons compared to traditional pharmacological tools. For example, both inhibitory (e.g., hM4Di) and excitatory (e.g., hM3Dq) DREADDs have been utilized to selectively manipulate the mesocorticolimbic dopamine circuit in both rats and mice. In both species, chemogenetic ligand administration acting at hM4Di receptors within the ventral tegmental area (VTA) decreased locomotor activity whereas ligand activation of hM3Dq in the VTA increased locomotor activity [2–5].

The pharmacological effects of any chemical ligand acting at either engineered or native receptors are influenced by numerous factors including potency, time course, and receptor selectivity. Clozapine-N-oxide (CNO) has been the classically used ligand in studies utilizing muscarinic-based DREADDs; however, recent evidence suggests CNO effects may be mediated by back conversion to clozapine rather than CNO directly. Clozapine not only has significantly greater affinity for DREADDs than CNO but also interacts with numerous endogenous G-protein coupled-receptors (GPCRs) suggesting poor receptor selectivity for engineered-vs-endogenous receptors [6–8]. To mitigate potential off-target effects produced from the back-conversion of CNO to clozapine, researchers have developed alternative DREADD ligands such as Compound 21 (C21) and deschloroclozapine (DCZ) [3,9,10]. For example, C21 has similar selectivity for DREADDs over endogenous muscarinic receptors but increased potency compared to CNO and has shown no evidence of back-conversion to clozapine [11]. In addition, DCZ has even higher affinity and selectivity for DREADDs over endogenous receptors compared to CNO and C21 [9]. However, there are a paucity of in vivo behavioral studies that have rigorously compared the potency and time course of available DREADD ligands in rats to provide an empirical foundation for DREADD ligand selection.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to compare the behavioral pharmacology of three different DREADD ligands CNO, C21, and DCZ in a locomotor activity assay in transgenic male and female rats expressing Cre-recombinase in tyrosine hydroxylase (TH:Cre) positive cells. Locomotor activity was selected as a behavioral measure because it is an unconditioned behavior resulting in potentially higher throughput. The VTA was selected as the target of DREADD expression because VTA activation has been shown to produce pronounced and sustained increases in locomotor activity [2]. Once CNO, C21, and DCZ activity effects were determined pre-DREADD virus injection, rats were bilaterally injected with a Cre-dependent hM3Dq DREADD into the VTA and CNO, C21, and DCZ activity effects were redetermined. d-Amphetamine effects on activity pre- and post-DREADD virus injections were also determined as a positive control. The proposed experimental design was influenced by recently published experimental design considerations for using chemogenetic tools [12,13]. We hypothesized that d-amphetamine would increase activity both pre- and post-DREADD virus injections and that expression of the engineered receptor alone would not impact d-amphetamine effects. We further hypothesized that CNO, C21, and DCZ alone would not significantly increase activity pre-DREADD virus injections but would significantly increase activity post-DREADD virus expression in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

2.0. Methods

2.1. Subjects.

A total of (4) adult male and (5) adult female homozygous TH:Cre transgenic Sprague-Dawley rats (Envigo, Frederick, MD) served as study subjects. Two cohorts of rats were tested. Pre-DREADD studies were conducted in the first cohort but not the second cohort. Final sample groups are reported in the figure legends. Animals were individually housed in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium maintained on a 12-h light-dark cycle (lights on from 0600 to 1800h). Rats had ad libitum access to food and water in the home cage. The vivarium was accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International, and both experimental and enrichment protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the 2011 National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Locomotor procedure

Locomotor activity was assessed using four Plexiglass open field chambers with dimensions of 17in L x 17in W x 12in H (Med Associates Inc., Fairfax, VT). Each box was equipped with a camera connected to a computer with AnyMaze software (v. 4.99; Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL) assessing horizontal locomotor activity expressed as total distance travelled in meters (m). Following an initial habituation session, experimental sessions were conducted twice per week with at least 48 h between sessions. Sessions began with an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of a drug dose after which animals were immediately placed in locomotor boxes and their movement recorded for two hours. Drugs were administered in the following order with doses randomized across all animals: d-amphetamine (vehicle, 0.1, 0.32, 1,and 3.2 mg/kg), deschloroclozapine (DCZ; vehicle, 0.32, 1, 3.2, 10, 32, 100, and 320 μg/kg), clozapine-N-oxide (CNO; vehicle, 0.32, 1, 3.2, and10 mg/kg), and compound 21 (C21; vehicle, 0.032, 0.1, 0.32, 1, and 3.2 mg/kg). Dose ranges used were initially determined based on the literature [2,9,11] and adjusted post-DREADD virus injection to capture the full dose-effect curve of each ligand, ranging from maximally effective to ineffective.

Once all drug/dose conditions were initially tested in the first cohort, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (2–4% in oxygen; Patterson Veterinary Supply, Loveland, CO). A 5μL Hamilton syringe was used to inject 1μL/hemisphere of a Cre-dependent Gq-coupled DREADD virus (pAAV2-hSyn-DIO-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry, 6 × 1012 vector genomes (vg)/mL, Catalog #44361-AAV2; AddGene, Watertown, MA) into the VTA using stereotaxic coordinates based on the literature (relative to Bregma: AP – 5.5 mm; ML ± 0.8 mm; DV – 8.15 mm) [5]. Virus was injected over a five-minute period after which the syringe was left in place for another five minutes. Following syringe removal, the incision site was sutured, and the animals received 5 mg/kg ketoprofen as a post-operative analgesic. After three weeks to allow DREADD expression, locomotor activity following d-amphetamine, DCZ, CNO, and C21 administration alone was redetermined in the first cohort or determined in the second cohort of animals.

2.3. Drugs

d-Amphetamine hemisulfate (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in sterile saline to a final volume of 1 mL/kg. CNO (NIDA Drug Supply Program, Research Triangle Institute, RTP, NC), C21 (TOCRIS, Bristol, UK), and DCZ (MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ) were dissolved in sterile 2% DMSO in saline to a final volume of 1 mL/kg. All drugs were passed through a sterile 0.22 μm filter (Millex GV, Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA) prior to IP administration. Drug doses were expressed as the salt or base forms listed above.

2.4. Immunohistochemistry

Following completion of behavioral experiments, animals were administered a sub-lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (Euthasol™) followed by transcardial perfusion with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (Merck, Kenilworth, NJ) in PBS. Brains were post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h then saturated in 30% v/v sucrose in PBS. Tissue was stored at −80°C until immunohistochemistry was performed.

To confirm VTA DREADD expression, tissue was co-stained for mCherry and TH. 40 μm floating sections were blocked in 3% normal goat serum, then incubated in rabbit anti-DS red (1:1000; catalog #632496, TakaraBio, San Jose, CA) and mouse anti-TH (1:1000; catalog #22941, Immunostar, Hudson, WI) for 48 h at 4°C. Sections were washed then incubated in Alexa Fluor goat anti-rabbit 488 and Alexa Fluor goat anti-mouse 594 antibodies (both 1:500; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) for 3 h. Sections were mounted using Fluoromount-G™, with DAPI (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Carlsbad, CA), cover slipped, and imaged at 40x using a Vectra 3 Polaris microscope (Akoya Biosciences, Marlborough, MA).

2.4. Data analyses.

The primary dependent behavioral measures were 1) total distance traveled (m) and 2) time course of each drug dose administered. Total distance traveled was averaged across all animals for each drug dose to yield the group mean data. These data were analyzed using a repeated measures one-way ANOVA with dose as the single factor. Dunnett’s post-hoc tests comparing treatment to vehicle were conducted following significant treatment effects. Time course for each drug dose was averaged across all animals and analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. Šídák’s multiple drug dose was averaged across all animals and analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. comparisons test was conducted following significant treatment effects. Violations of sphericity were corrected using the Geisser-Greenhouse epsilon. All analyses were performed using GraphPad software (v. 9.4.1; GraphPad Scientific, San Diego, CA). Significance was established a priori at the 95% confidence level.

3.0. Results

3.1. Effects of d-amphetamine and DREADD ligands pre-DREADD virus injection

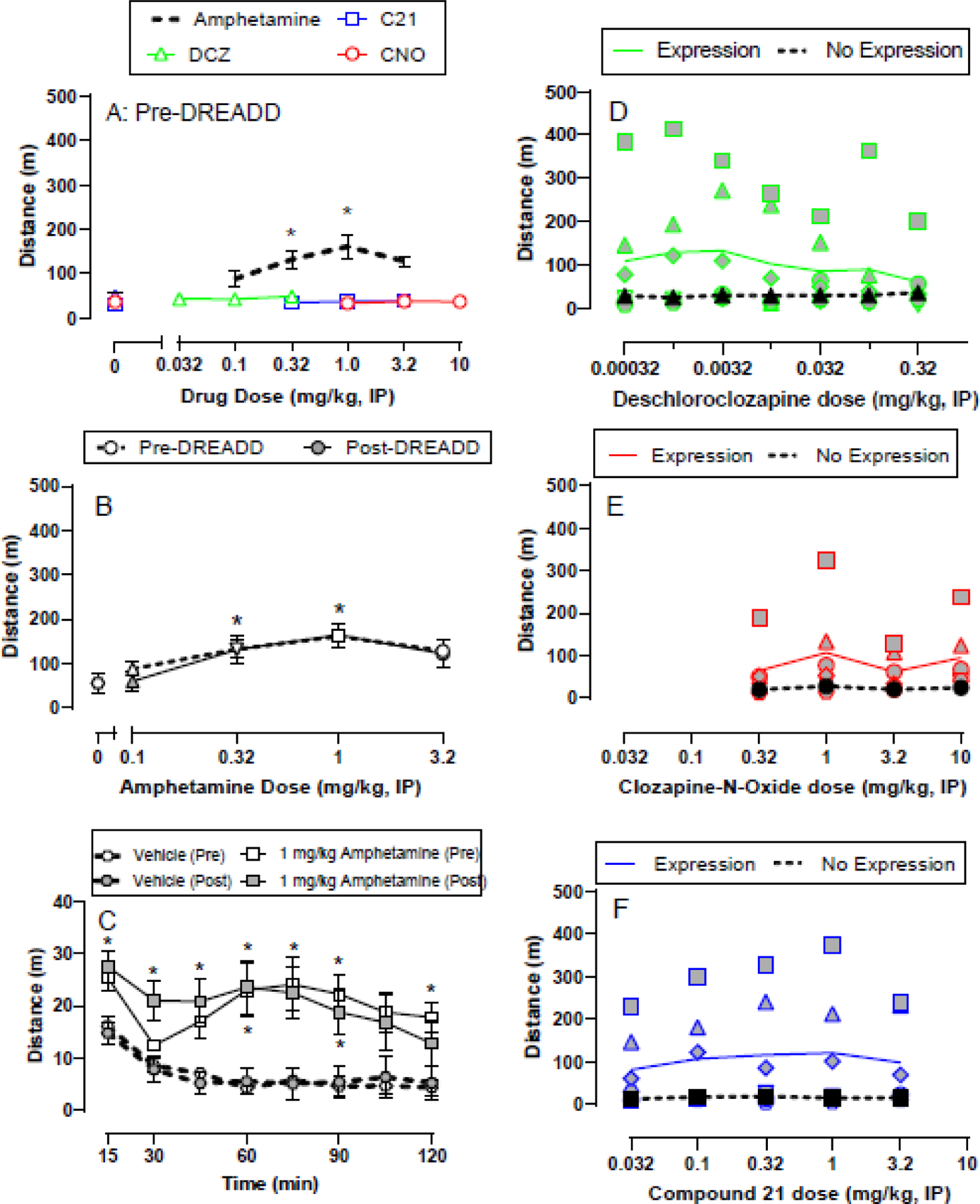

Figure 1A shows effects of d-amphetamine, CNO, C21, and DCZ on locomotor activity before bilateral intra-VTA Gq DREADD virus injections. 0.32 and 1.0 mg/kg d-amphetamine significantly increased locomotor activity compared to vehicle (dose: F(2,10)=8.1, p=0.008). Additionally, DCZ (0.32–320 μg/kg), CNO (1–10 mg/kg), or C21 (0.032–3.2 mg/kg) failed to significantly alter locomotor activity up to the largest dose tested.

Figure 1.

Effects of amphetamine, DCZ, CNO, and C21 alone on locomotor activity both pre-DREADD and post-DREADD virus injection. All points in panels A represent the mean±SEM of 6 rats. Panels B and C compare amphetamine potency (B) and time course (C) pre-DREADD and post-DREADD virus injection. Pre-DREADD points represent mean±SEM of 6 rats and post-DREADD points represent mean±SEM of 9 rats in panels B and C. Panels D-F show individual subject behavioral data for deschloroclozapine (D), clozapine-N-oxide (E), and compound 21 (F) in the six rats that showed mCherry expression and the three rats that failed to show mCherry expression “no expression.” * denotes p<0.05 compared to vehicle (0 drug dose).

3.2. Effects of d-amphetamine and DREADD ligands post-DREADD virus injection

Figure 1B shows d-amphetamine dose-response function both pre- and post-DREADD virus injection. Similar to the pre-DREADD condition, 0.32 and 1.0 mg/kg, IP d-amphetamine administered post-DREADD virus injection significantly increased locomotor activity compared to vehicle (dose: F(1.4,11.3)=4.7, p=0.042). There was no significant main effect of virus condition nor an amphetamine dose × virus interaction. Amphetamine significantly increased activity in a time- and dose-dependent manner before DREADD virus injections (time: F(2.4,11.9)=20.9, p<0.001; dose: F(2,10)=8.1, p=0.008; interaction: F(3.1,15.4)=4.2, p=0.024) and after virus injections (time: F(2.1,16.7)=24.4, p<0.001; dose: F(1.4,11.3)=4.7, p=0.042).

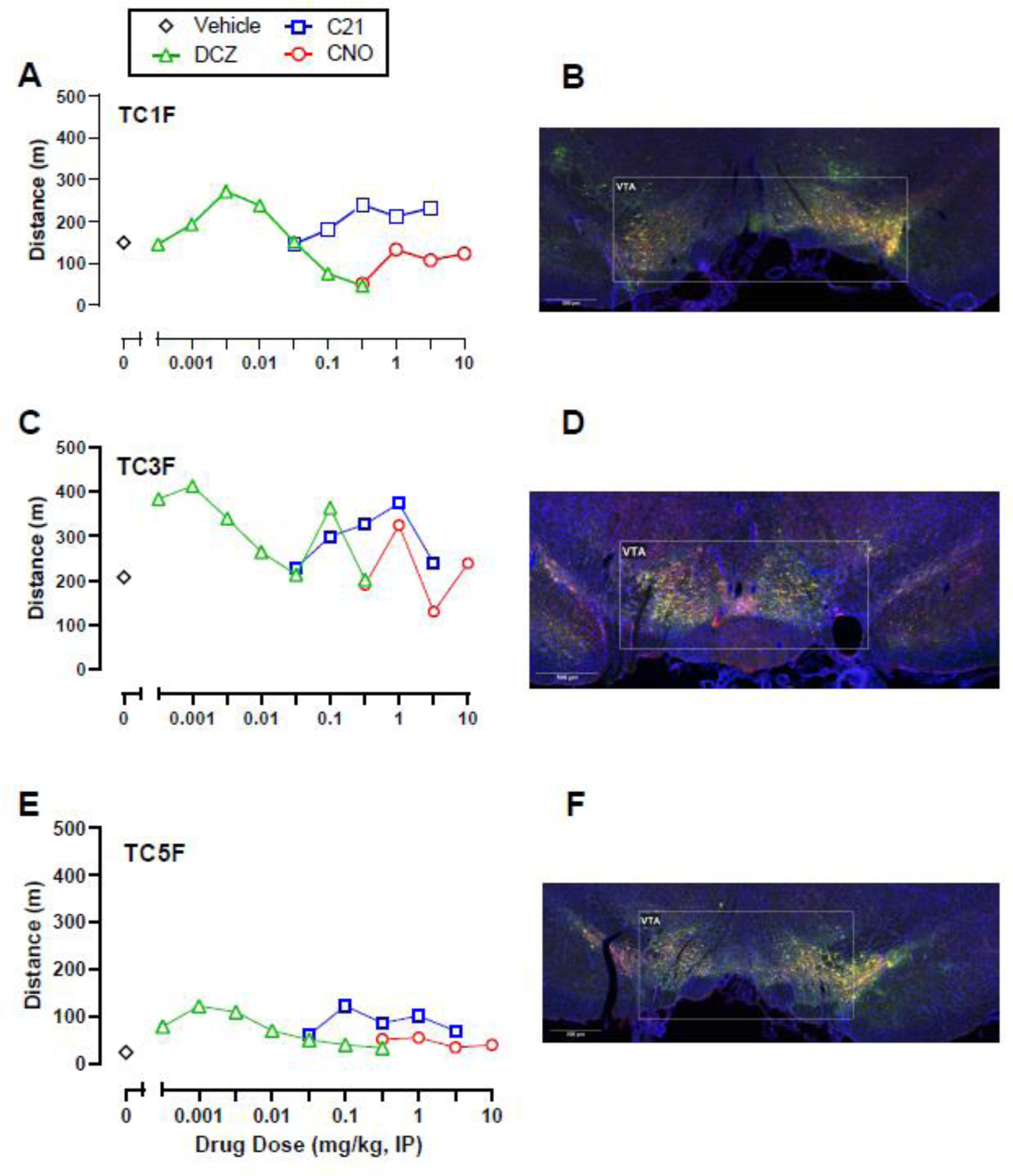

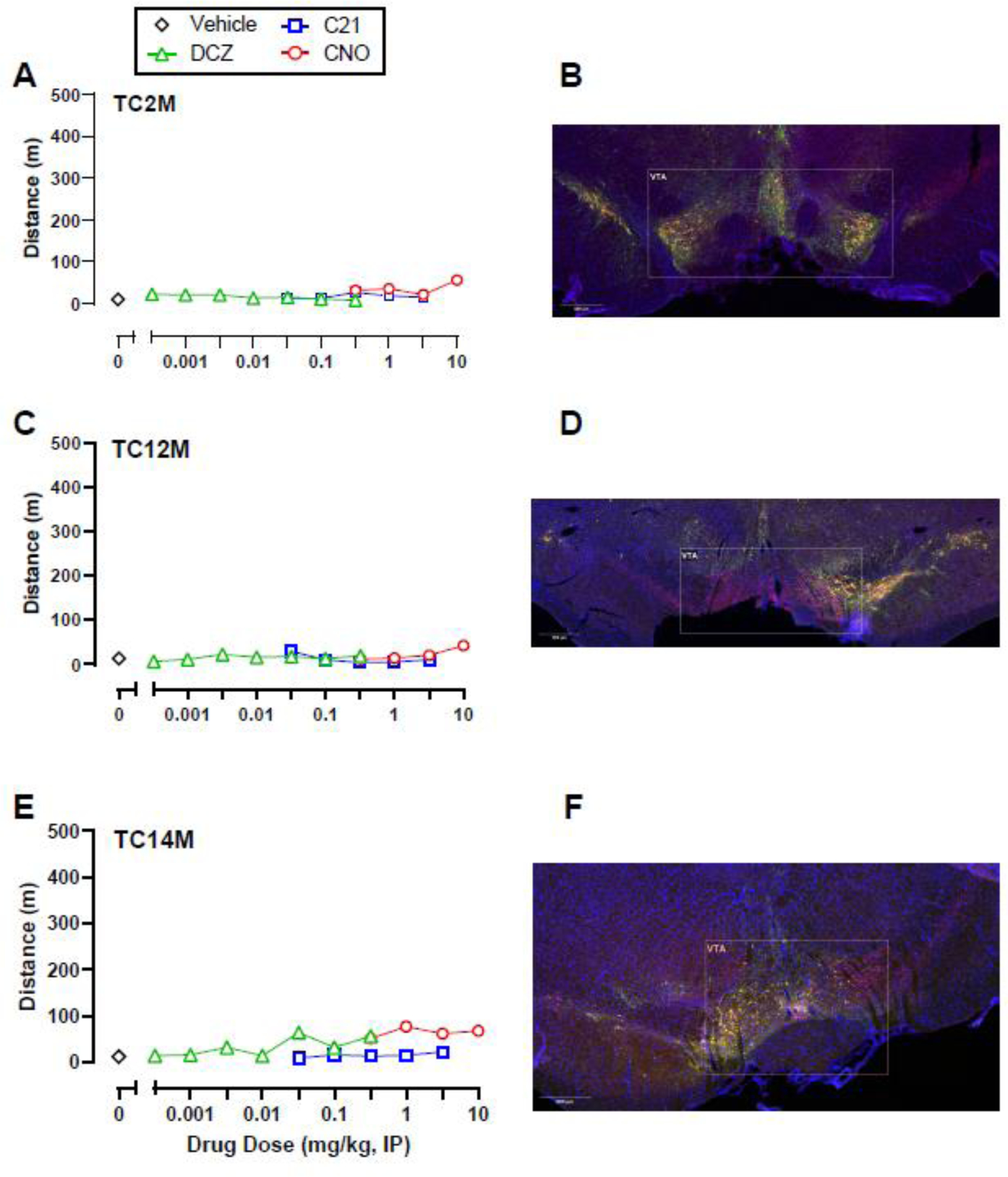

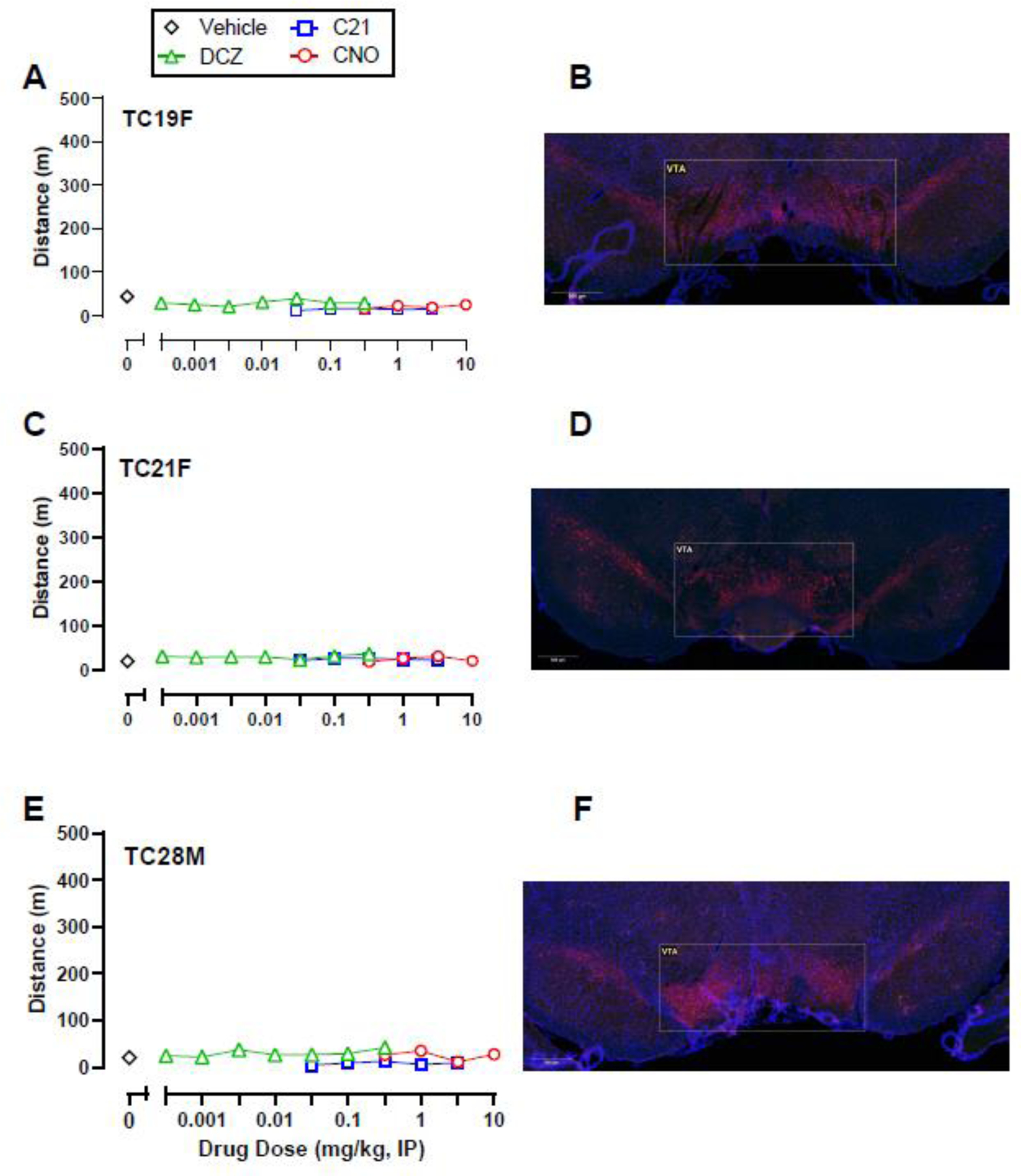

Following visualization of intra-VTA DREADD expression, subjects were subdivided into two groups. One group (Expression; n=6) displayed both mCherry and co-mCherry/TH expression throughout the VTA, whereas the second group (No Expression; n=3) showed little to no mCherry expression alone or co-expression with TH within the VTA. No DREADD agonist tested significantly increased activity in the Expression group (Figure 1D-F) compared to either DREADD agonist vehicle or data from the No Expression group; however, there were trends of increased locomotor activity in the Expression group. Post-hoc power analyses reported sample sizes of 70, 55, 50 rats would be necessary to detect a significant effect of DCZ, C21, and CNO, respectively if present (Supplemental Table 1). Individual subject data in the Expression group revealed that three (TC1, TC3, and TC5) out of six rats displayed a consistent locomotor activation effect following DCZ and C21 administration, and to a lesser extent CNO (Figure 2). The other three rats (TC2, TC12, and TC14) in the Expression group did not show a locomotor activity effect of any DREADD agonist and visually weaker mCherry and co-mCherry/TH expression (Figure 3). Individual data from the three rats (TC19, TC21, and TC28) that showed neither a locomotor effect nor mCherry or co-mCherry/TH expression are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 2.

Individual locomotor activity effects of DCZ, CNO, and C21 alone (A, C, E) and corresponding intra-VTA Gq DREADD expression (B, D, F) in three TH:Cre rats that showed mCherry expression and a behavioral response to the chemogenetic ligands post-DREADD virus injections. DAPI staining is represented in blue, TH in red, and mCherry in green. Yellow represents colocalization of TH and mCherry.

Figure 3.

Individual locomotor activity effects of DCZ, CNO, and C21 alone (A, C, E) and corresponding intra-VTA hM3Dq DREADD expression (B, D, F) in three TH:Cre rats that showed mCherry expression, but little-to-no behavioral response to the chemogenetic ligands post-DREADD virus injections. DAPI staining is represented in blue, TH in red, and mCherry in green. Yellow represents colocalization of TH and mCherry.

Figure 4.

Individual locomotor activity effects of DCZ, CNO, and C21 alone (A, C, E) and corresponding intra-VTA hM3Dq DREADD expression (B, D, F) in three TH:Cre rats that showed no mCherry expression and little-to-no behavioral response to the chemogenetic ligands post-DREADD virus injections. DAPI staining is represented in blue, TH in red, and mCherry in green. Yellow represents colocalization of TH and mCherry.

4.0. Discussion

This study evaluated the effects of d-amphetamine and three DREADD agonists (DCZ, C21, and CNO) alone on locomotor activity in the absence and presence of a Gq-coupled chemogenetic receptor expressed in the VTA. There were four main findings. First, d-amphetamine significantly increased locomotor activity prior to and after DREADD virus injection targeting the VTA. These results suggest expression of the engineered Gq receptor itself did not significantly alter amphetamine locomotor effects. Second, no DREADD agonist dose tested significantly altered locomotor activity pre-DREADD virus injection suggesting these agonists demonstrate a degree of behavioral selectivity. This result was further supported by the absence of DREADD agonist effect in the No Expression group. Third, no DREADD agonist dose significantly altered locomotor activity post-DREADD virus injection. However, individual subject analysis revealed that three out of six rats in the Expression group showed a locomotor activity effect for DCZ and C21, and to a lesser extent CNO. Overall, large individual variability was observed in both DREADD agonists effects and intra-VTA DREADD expression and suggest further basic research would facilitate the utility of these chemogenetic tools for behavioral neuroscience research.

d-Amphetamine was used as a positive control comparator for DREADD agonist effects on locomotor activity before and after intra-VTA DREADD virus injections. Consistent with previous rat studies [14,15], d-amphetamine significantly increased locomotor activity before and after intra-VTA DREADD virus injections. Furthermore, d-amphetamine effects were not significantly different before and after DREADD virus injections. These results demonstrate that Gq-DREADD expression did not alter d-amphetamine locomotor activity effects. Overall, these d-amphetamine results provide an empirical basis to compare the effects of DCZ, C21, and CNO on locomotor activity.

All three DREADD agonists tested in the present study failed to significantly alter locomotor activity before intra-VTA DREADD virus injection up to doses that reached solubility limits. The present results are consistent with previous results demonstrating a lack of CNO, C21, and DCZ effect in non-DREADD expressing control mice and rats [2–5,16–18]. Furthermore, the lack of DCZ, C21, and CNO locomotor effect before intra-VTA DREADD virus injections provides one measure of behavioral selectivity supporting the utility of these chemogenetic tools.

The present findings add to a growing preclinical literature determining the basic pharmacological effects of DREADD agonists [3,6,7,17,19–21]. The present study utilized a locomotor assay towards the goal of efficiently comparing the potency and time course of multiple DREADD agonists in the same behavioral procedure using a common within-subjects design in behavioral pharmacology studies. None of the three DREADD agonists examined significantly increased locomotor activity following DREADD virus injection and confirmation of mCherry expression. The present results are inconsistent with published studies demonstrating DREADD agonists acting on stimulatory DREADDs expressed in the VTA significantly increased locomotor activity in both rats and mice [2–5,16,18]. There are several potential reasons for these differential results.

One potential reason for the differential behavioral results and the published literature could be rat strain. Previous rat studies determining DREADD agonist effects on locomotor activity have used TH:Cre rats on a Long-Evans background [2,16], whereas the present study used a Sprague-Dawley background. Strain differences in drug effects between Sprague-Dawley and Long-Evans rats have been previously reported on other behavioral endpoints such as prepulse inhibition [22]. Elucidation of potential rat strain differences on chemogenetic agonist on other behavioral or neurochemical endpoints is one potential future direction and beyond the scope of this manuscript. In addition to potential strain differences in DREADD agonist effects, neuroanatomical differences could have also contributed to the differential behavioral results between the present study and previous studies. For example, Boekhoudt (2016) reported that CNO administration increased locomotor activity in TH:Cre Long-Evans rats only when the Gq-DREADD was injected into the VTA, but not the substantia nigra pars compacta. The present results were consistent with these previous results such that the three rats that showed expression in the more lateral VTA and substantia nigra showed little-to-no behavioral effect of any DREADD agonist.

Another potential reason for the lack of a significant DREADD agonist effect in the present study could be explained by individual subject variability both in chemogenetic receptor expression and ligand behavioral effects. Receptor expression via the mCherry fluorophore was determined at the end of the experiment, but receptor expression over the course of several months could have fluctuated. Recently, CNO and JHU37160 behavioral effects acting on hM4Di DREADDs in the VTA were compared in the same rats and produced similar effects in TH:Cre rats, but differential behavioral effects in wildtype rats [23]. One future direction would be to develop standardized methods that would facilitate the correlation between on-target vs. off-target chemogenetic receptor expression with behavioral endpoints. One study in rats using inhibitory hM4Di DREADDs reported a correlation between receptor expression with significant decreases in excitatory synaptic transmission [24]. In addition, a non-human primate study using inhibitory DREADDs found that expression levels directly correlated with behavioral effects [25]. However, similar studies conducted correlating expression of excitatory DREADDs with behavioral endpoints have not been conducted to the best of our knowledge. Finally, reporting both inclusion/exclusion criteria and individual subject variability will be critical in understanding the relationship between expression level and functional output to facilitate utility of chemogenetic tools.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Services in support of the research project were generated by the VCU Massey Cancer Center Health Communication and Digital Innovation Shared Resource core, supported, in part, with funding from NIH-NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA016059.

Role of funding source

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (T32DA007027, P30DA033934, and R36DA057546). NIDA had no role in study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, in the writing or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The manuscript content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIDA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

HLR: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. KLN: methodology, resources, writing – review and editing. KLS: methodology, resources, writing – review and editing. PJH: methodology, resources, supervision, writing – review and editing. MLB: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, supervision, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

References

- [1].Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2007;104:5163–8. 10.1073/pnas.0700293104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Boekhoudt L, Omrani A, Luijendijk MCM, Wolterink-Donselaar IG, Wijbrans EC, van der Plasse G, et al. Chemogenetic activation of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area, but not substantia nigra, induces hyperactivity in rats. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2016;26:1784–93. 10.1016/J.EURONEURO.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bonaventura J, Eldridge MAG, Hu F, Gomez JL, Sanchez-Soto M, Abramyan AM, et al. High-potency ligands for DREADD imaging and activation in rodents and monkeys. Nature Communications 2019;10:1–12. 10.1038/s41467-019-12236-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jing MY, Han X, Zhao TY, Wang ZY, Lu GY, Wu N, et al. Re-examining the role of ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons in motor activity and reinforcement by chemogenetic and optogenetic manipulation in mice. Metabolic Brain Disease 2019;34:1421–30. 10.1007/S11011-019-00442-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mahler SV, Brodnik ZD, Cox BM, Buchta WC, Bentzley BS, Quintanilla J, et al. Chemogenetic manipulations of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons reveal multifaceted roles in cocaine abuse. Journal of Neuroscience 2019;39:503–18. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0537-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bærentzen S, Casado-Sainz A, Lange D, Shalgunov V, Tejada IM, Xiong M, et al. The Chemogenetic Receptor Ligand Clozapine N-Oxide Induces in vivo Neuroreceptor Occupancy and Reduces Striatal Glutamate Levels. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2019;0:187. 10.3389/FNINS.2019.00187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gomez JL, Bonaventura J, Lesniak W, Mathews WB, Sysa-Shah P, Rodriguez LA, et al. Chemogenetics revealed: DREADD occupancy and activation via converted clozapine. Science 2017;357:503–7. 10.1126/science.aan2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].MacLaren DAA, Browne RW, Shaw JK, Radhakrishnan SK, Khare P, España RA, et al. Clozapine N-oxide administration produces behavioral effects in long-evans rats: Implications for designing DREADD experiments. ENeuro 2016;3. 10.1523/ENEURO.0219-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Nagai Y, Miyakawa N, Takuwa H, Hori Y, Oyama K, Ji B, et al. Deschloroclozapine, a potent and selective chemogenetic actuator enables rapid neuronal and behavioral modulations in mice and monkeys. Nature Neuroscience 2020;23:1157–67. 10.1038/s41593-020-0661-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Weston M, Kaserer T, Wu A, Mouravlev A, Carpenter JC, Snowball A, et al. Olanzapine: A potent agonist at the hM4D(Gi) DREADD amenable to clinical translation of chemogenetics. Science Advances 2019;5. 10.1126/sciadv.aaw1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Thompson KJ, Khajehali E, Bradley SJ, Navarrete JS, Huang XP, Slocum S, et al. DREADD Agonist 21 is an effective agonist for muscarinic-based DREADDs in vitro and in vivo. ACS Pharmacology and Translational Science 2018;1:61–72. 10.1021/acsptsci.8b00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Aldrin-Kirk P, Björklund T. Practical considerations for the use of DREADD and other chemogenetic receptors to regulate neuronal activity in the mammalian brain. Methods in Molecular Biology, vol. 1937, 2019, p. 59–87. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9065-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Goutaudier R, Coizet V, Carcenac C, Carnicella S. DREADDs: The power of the lock, the weakness of the key. favoring the pursuit of specific conditions rather than specific ligands. ENeuro 2019;6. 10.1523/ENEURO.0171-19.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Antoniou K, Kafetzopoulos E, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z, Hyphantis T, Marselos M. d-amphetamine, cocaine and caffeine: a comparative study of acute effects on locomotor activity and behavioural patterns in rats. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 1998;23:189–96. 10.1016/S0149-7634(98)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pijnenburg AJJ, Honig WMM, Van Rossum JM. Inhibition of d-amphetamine-induced locomotor activity by injection of haloperidol into the nucleus accumbens of the rat. Psychopharmacologia 1975;41:87–95. 10.1007/BF00421062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Minnaard AM, Luijendijk MCM, Baars AM, Drost L, Ramakers GMJ, Adan RAH, et al. Increased elasticity of sucrose demand during hyperdopaminergic states in rats. Psychopharmacology 2022. 10.1007/S00213-022-06068-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nentwig TB, Obray JD, Vaughan DT, Chandler LJ. Behavioral and slice electrophysiological assessment of DREADD ligand, deschloroclozapine (DCZ) in rats. Scientific Reports 2022;12:1–9. 10.1038/s41598-022-10668-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Runegaard AH, Sørensen AT, Fitzpatrick CM, Jørgensen SH, Petersen AV, Hansen NW, et al. Locomotor-and Reward-Enhancing Effects of Cocaine Are Differentially Regulated by Chemogenetic Stimulation of Gi-Signaling in Dopaminergic Neurons. ENeuro 2018;5. 10.1523/ENEURO.0345-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Goutaudier R, Coizet V, Carcenac C, Carnicella S. Compound 21, a two-edged sword with both DREADD-selective and off-target outcomes in rats. PLoS One 2020;15:2020.05.01.072181. 10.1101/2020.05.01.072181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ilg AK, Enkel T, Bartsch D, Bähner F. Behavioral effects of acute systemic low-dose clozapine in wild-type rats: Implications for the use of DREADDs in behavioral neuroscience. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 2018;12. 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rodd ZA, Engleman EA, Truitt WA, Burke AR, Molosh AI, Bell RL, et al. CNO administration increases dopamine and glutamate in the medial prefrontal cortex of wistar rats: Further concerns for the validity of the CNO-activated DREADD procedure. Neuroscience 2022. 10.1016/J.NEUROSCIENCE.2022.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Swerdlow NR, Shoemaker JM, Bongiovanni MJ, Neary AC, Tochen LS, Saint Marie RL. Strain differences in the disruption of prepulse inhibition of startle after systemic and intra-accumbens amphetamine administration. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 2007;87:1–10. 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lawson KA, Ruiz CM, Mahler SV. A head-to-head comparison of two DREADD agonists for suppressing operant behavior in rats via VTA dopamine neuron inhibition. Neuroscience; 2023. 10.1101/2023.03.27.534429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Goossens M-G, Larsen LE, Vergaelen M, Wadman W, Van Den Haute C, Brackx W, et al. Level of hM4D(Gi) DREADD Expression Determines Inhibitory and Neurotoxic Effects in the Hippocampus 2021. 10.1523/ENEURO.0105-21.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Upright NA, Brookshire SW, Schnebelen W, Damatac CG, Hof PR, Browning PGF, et al. Behavioral Effect of Chemogenetic Inhibition Is Directly Related to Receptor Transduction Levels in Rhesus Monkeys. Journal of Neuroscience 2018;38:7969–75. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1422-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.