Abstract

Introduction:

Sarcoidosis is a rare inflammatory disease with unclear natural history. Using a large, retrospective, longitudinal, population-based cohort, we sought to define its natural history in order to guide future clinical studies.

Methods:

We identified 722 newly diagnosed cases of sarcoidosis within Kaiser Permanente Northwest health care records between 1995–2015. We investigated immunosuppressive medication use in the two years following diagnosis, analyzed demographic and clinical characteristics, and quantified chest imaging and pulmonary function testing (PFTs) across the clinical course.

Results:

Over two years of follow-up, 41% of patients were treated with prednisone. Of those, 75% tapered off their first course within 100 days, although half of those patients required recurrent therapy. Five percent of the entire cohort remained on prednisone for longer than one year, with an average daily dose of 10–20mg. Chest imaging was associated with early prednisone use, and chest CT was associated with changes in prednisone dose. PFTs or demographics were not associated with prednisone use. Cumulative prednisone doses were significantly higher in African Americans (1,845mg additional) and those who had a chest CT (2,015mg additional). Overall, PFTs were less frequently obtained than chest imaging and had no significant change over disease course.

Discussion:

The natural history of sarcoidosis varies greatly. For those requiring therapy, corticosteroid burden is high. Chest imaging drives medication dose changes as compared to PFTs, but neither outcome fully captures the entire history of disease. Prospective cohorts are needed with purposefully collected, repeated measures that include objective clinical assessments and symptoms.

Introduction

In the United States (U.S.), rare diseases are defined as those that affect fewer than 200,000 people (1). However, collectively thirty million people suffer from rare diseases, and fewer than 10% of rare diseases have cures (1). Sarcoidosis is a rare multi-system inflammatory disease that primarily affects the lungs, with few effective treatments (2). It is difficult to design clinical trials for new treatments because the natural history of the disease is not well characterized.

Natural history studies in sarcoidosis are difficult to perform because the disease can be heterogenous in terms of both presentation and outcome. Some patients improve on immunosuppressive treatment, but others do not. In addition, some patients improve without treatment (3). It is also difficult to recruit enough research participants at any one center because the disease is rare. Currently, clinicians use pulmonary function tests (PFTs) and radiologic imaging to monitor disease progression. However, there is frequently a dissociation between PFT and radiologic imaging results (4). One possible approach used to improve the understanding of the natural history of sarcoidosis, is to use “real-world evidence” extracted from patients’ medical records.

A better understanding of the natural history of sarcoidosis would assist in determining the number of patients needed for trials, inform the measurement of clinical outcomes, and aid in the development of novel biomarkers to guide treatment (5). The goal of this study was to define the natural history of sarcoidosis using a large, retrospective, longitudinal, population-based cohort of sarcoidosis patients. Specifically, we measured healthcare utilization, imaging frequency, PFTs, and longitudinal medication use. We then estimated factors associated with prednisone (immunosuppressive) use, duration, average dose, and cumulative dose.

Methods

Population

Our study was conducted using data from Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW), an integrated delivery system that provides care to approximately 525,000 members in Oregon and southwest Washington. KPNW membership comprises a stable population base that is demographically representative of the surrounding insured community. At KPNW, all aspects of a member’s health care—including but not limited to vital statistics, outpatient visits, hospital stays, ER visits, dispensed medications, procedures and imaging, and lab test results—are captured in the KP electronic health record (EHR) and associated with the member’s unique health record number. This unique health record number is fixed and retained over time, allowing for individual patient longitudinal follow-up, and connects potential coverage gaps. Every contact an individual makes with the medical care system and all referrals to outside services and hospitals are recorded in the EHR under this unique health record number. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Iowa and at KPNW.

Case Identification

We identified sarcoidosis cases as individuals with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis of 135 or 321.4 between January 1st, 1995 and September 30th, 2015. We defined each case’s index date as the first observed diagnosis of sarcoidosis. To ensure cases reflected a new sarcoidosis diagnosis, we required two years of continuous KPNW enrollment before the first diagnosis. To capture early natural history and post-diagnositic management, we also required 2 years of continuous enrollment after the index date; therefore, each case was enrolled a minimum of four years. Additionally, we required visits on two or more unique dates with sarcoidosis diagnosis to be included as a case, to avoid “rule-out” diagnoses. For the second diagnosis, we included the ICD-10-CM codes of D86.0, D86.1, D86.2, D86.3, D86.81, D86.82, D86.83, D86.84, D86.85, D86.86, D86.87, D86.89, or D86.9 in addition to the ICD-9-CM codes of 135 or 321.4.

Medication Use

We identified prednisone or a corticosteroid-sparing agent (methotrexate, azathioprine, leflunomide, mycophenolate, infliximab, adalimumab) dispensing event by a KPNW pharmacy or a claim for dispensing from a non-KPNW pharmacy submitted to KPNW. We identified events of interest by matching the medication generic name during the two years following index date. These data included the date of dispensing, the days-supply dispensed, and the medication strength. We used these variables to determine the duration, average dose, and cumulative dose of each medication during the follow-up period.

Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs)

We identified all PFTs performed on sarcoidosis patients in our cohort. We defined ‘baseline’ PFTs as those occurring within 60 days of index date and ‘follow-up’ PFTs as those performed at least 60 days after the first diagnosis but not more than 15 months after index date. We measured pulmonary performance using percent predicted forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), percent predicted forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1/FVC, and adjusted diffusing capacity (DLCO). In patients who underwent a PFT during both baseline and followup, we compared FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC, and DLCO values for these periods using a paired t-test. In instances where a patient had multiple PFTs during the baseline or follow-up period, we calculated mean values for FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC, and DLCO measurements.

Chest Imaging

We identified chest imaging studies using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. Chest CT scans were identified by CPT codes 72150, 71260, 71270, and 71275; chest x-rays (CXRs) were identified with CPT codes 71010, 71015, 71021, 71022, 71030, 71035, and 71101. We considered chest imaging to have occurred at baseline if imaging was performed within 60 days before or after the index diagnosis date.

Outcomes and Comparisons

Our primary outcome was the percentage of patients with prednisone use over the 2 years after index date. We labeled individuals as having used prednisone if they were dispensed prednisone at least once during the two years after diagnosis. We further divided prednisone ever-users into two subgroups: immediate users (starting within 30 days of diagnosis) and delayed users (starting at least 31 days after diagnosis and within the two years following diagnosis). We also included an ever-use of corticosteroid-sparing therapy as an outcome.

Secondary endpoints included prednisone use duration, average daily dose, and cumulative total dose. Using these endpoints, we further anlayzed the first course of prednisone therapy and the total course of therapy over the initial two years of disease. We defined the first course of therapy as the first time a prednisone prescription was filled after the sarcoidosis diagnosis, until ≥30 day lapse in drug supply. This reflects the initial treatment decision, and response to therapy.

Whether a participant ever filled a prescription for prednisone was regressed on demographics (age, sex, race), baseline diagnostics (PFT, chest CT, CXR) using logistic regression. Additionally, we regressed start time (within 30 days of the index diagnosis or 31 or more days after the index diagnosis) on the same collection of predictors. Finally, we estimated the effect of demographics and baseline diagnostics on the duration of prednisone therapy, the average dose while taking medication, and the cumulative dose during the first two years using ordinary least squares regression.

We modeled the odds of ever starting a corticosteroid-sparing agent by regressing on demographics, baseline characteristics, and whether the participant had a previous course of treatment with prednisone. As a measure of therapy intensity, we computed the total days on the corticosteroid-sparing therapy and regressed on the same collection of factors. We estimated the odds of use with logistic regression and the duration using ordinary least squares regression.

We were interested in whether medication changes were likely to occur following chest imaging (CXR or CT). We defined a medication change event as the initiation or cessation of prednisone (or steroid sparing agent), or a dose change, then determined time between the chest imaging and medication-change date, censoring data after the two years of follow-up. To establish the expected rate of prednisone initiating, cessation or change in dose, we randomly sampled 1,682 non-CXR or chest CT procedures from our cohort and determined time to the next medication change event or censoring date. We then repeated this 10,000 times to produce an estimate of the relationship between procedures and medication changes that we would expect if there were no relationship between the two events. We estimated the difference in the hazard of a medication change using Cox proportional hazard and report the mean estimated hazard ratio (HR) over the 10,000 replicates and the empirical 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Population

Of 1,477 subjects with a sarcoidosis diagnosis within the twenty-year dataset, 1,032 had at least two years of lookback, 823 had the required 2 or more years of enrollment following the index date, 749 had two or more diagnoses of sarcoidosis, and of these, 722 had complete data (27 subjects were missing complete data due to missing/unreported race). Our final sample was those 722 individuals using the two years prior and following the index date. Baseline characteristics and demographics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1:

Baseline Demographics and Cohort Characteristics

| Variable | Mean (SD) | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Race | |

|

| |

| White | 597 (83%) |

|

| |

| Black | 96 (13%) |

|

| |

| Asian | 14 (1.9%) |

|

| |

| Other | 15 (2.1%) |

|

| |

| Female | 456 (63%) |

|

| |

| Age | 53.0 (12.0) |

|

| |

| Chest Imaging | |

| Any chest imaging at baseline* | 501 (69%) |

| Chest CT | 224 (31%) |

| CXR | 499 (69%) |

|

| |

| PFT at Baseline | 145 (20%) |

Some participants got both chest CT and CXR.

Medication Use

A total of 294 patients (40.7 %) filled a prednisone prescription at least once in the two years following diagnosis. Of these, 130 had an initial fill within 30 days of diagnosis and 164 occurred 31 or more days after diagnosis. Of those with an initial prednisone fill within 30 days of diagnosis, median prednisone dispenses were the same day as diagnosis. For those started after the first 30 days, the median number of days until treatment was 227 days after the index date. The estimated associations between demographics and baseline diagnostics on the odds of ever starting prednisone and prescription-fill timing are shown in Table 2. Baseline chest imaging (CXR and CT) was associated with ever-use of prednisone (OR = 1.63 and 1.47, respectively) and was associated with earlier starting of prednisone (OR = 2.02 and 1.87). Women had an increased OR of prednisone use after 30 days (1.49 [1.02, 2.19]).

Table 2:

Predictors of Immediate, Eventual, or Ever-Use of Prednisone. Odds ratios are reported (95% CIs in parentheses).

| Start Prednisone ≤30 Days | Start Prednisone >30 Days | Ever Start Prednisone | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18–39 | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 40–49 | 0.85 (0.45, 1.62) | 1.17 (0.63, 2.22) | 1.01 (0.60, 1.69) |

| 50–59 | 0.98 (0.54, 1.79) | 1.51 (0.86, 2.76) | 1.32 (0.82, 2.14) |

| 60+ | 0.89 (0.47, 1.70) | 1.33 (0.73, 2.49) | 1.14 (0.69, 1.89) |

| Female | 0.70 (0.47, 1.05) | 1.49 (1.02, 2.19) | 1.07 (0.78, 1.48) |

| Race | |||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Black | 1.10 (0.61, 1.92) | 1.36 (0.82, 2.21) | 1.35 (0.86, 2.11) |

| Other | 0.54 (0.13, 1.64) | 0.75 (0.25, 1.88) | 0.59 (0.24, 1.34) |

| PFT at Baseline | 1.56 (0.97, 2.46) | 0.94 (0.59, 1.47) | 1.29 (0.87, 1.90) |

| Chest Imaging at Baseline | |||

| X-Ray | 2.02 (1.26, 3.34) | 1.18 (0.80, 1.75) | 1.63 (1.16, 2.30) |

| CT | 1.87 (1.20, 2.88) | 0.93 (0.59, 1.43) | 1.47 (1.01, 2.13) |

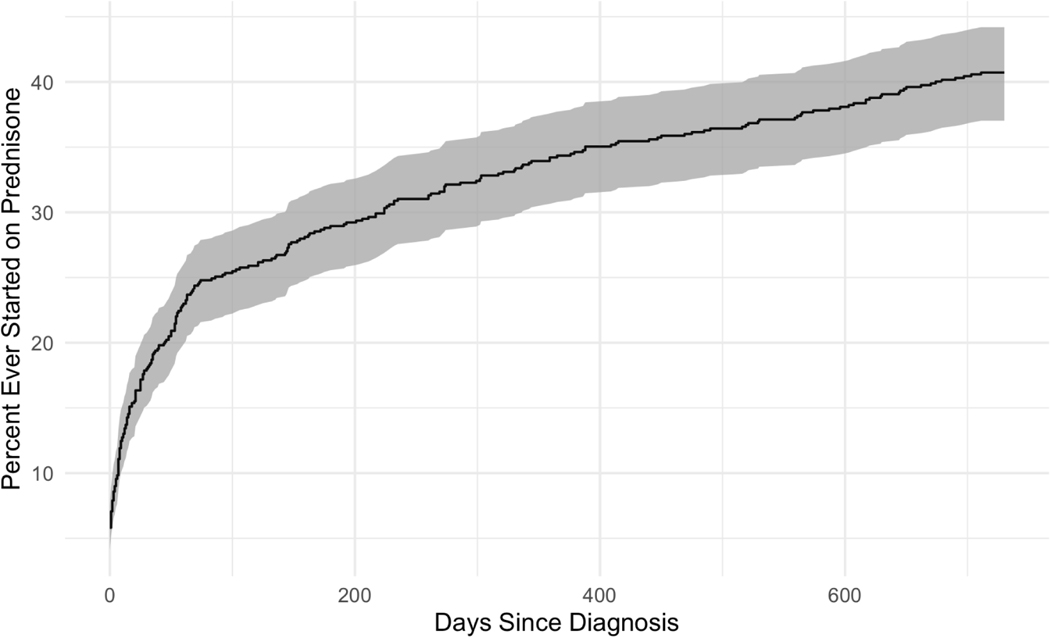

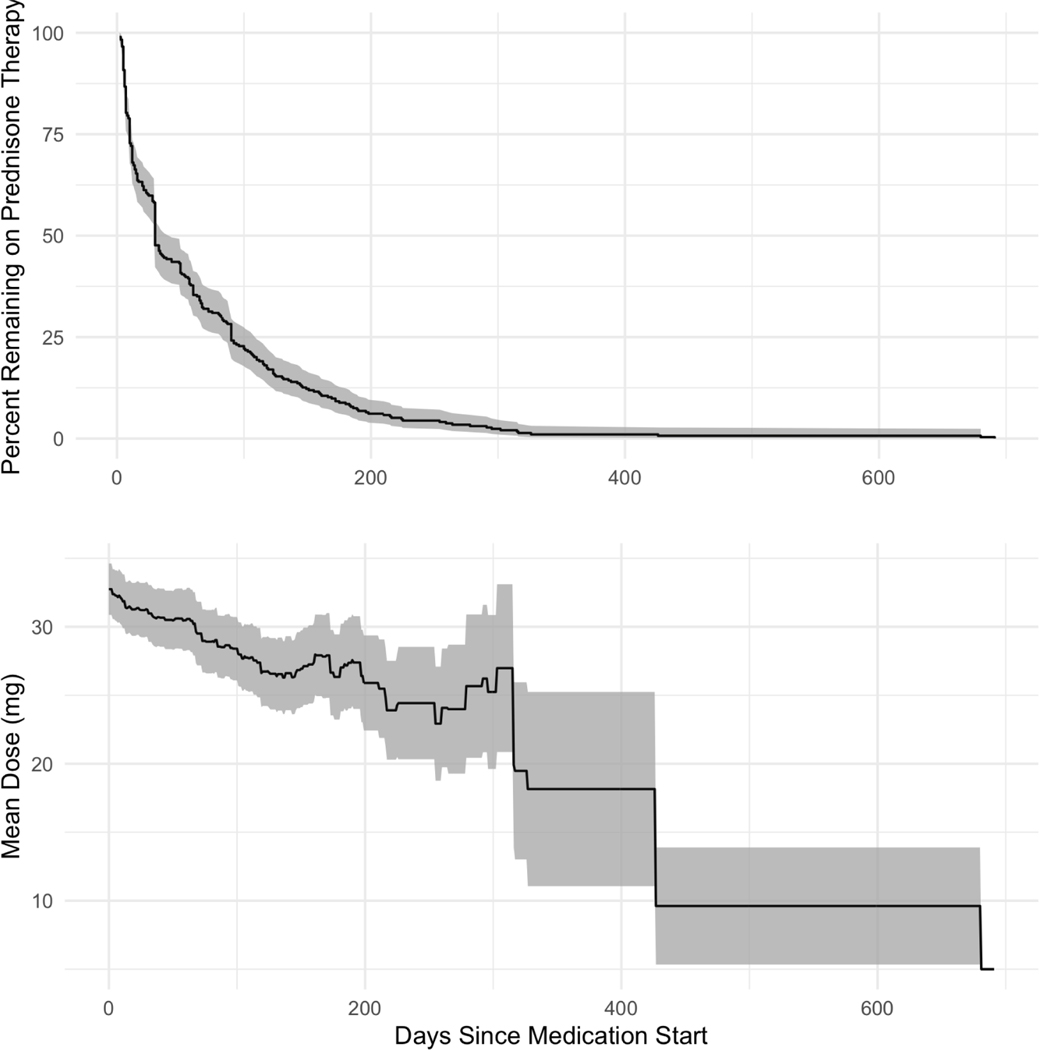

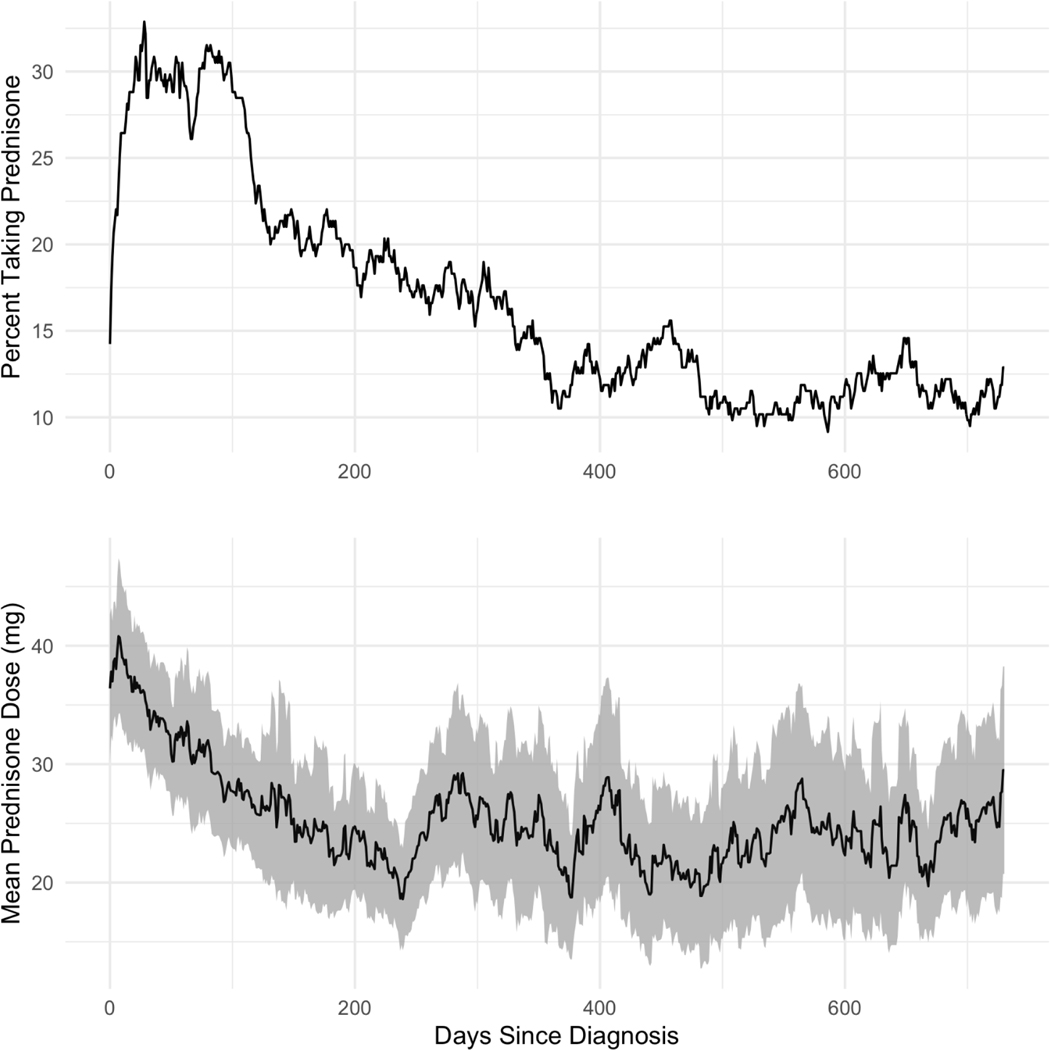

Prednisone was prescribed at the greatest rate within 90 days following sarcoidosis diagnosis (Figure 1). The average initial course of prednisone treatment was short and dose-tapering was common – approximately 75% of patients who started an early course of prednisone stopped taking it within 100 days of treatment (Figure 2). The average initial prednisone dose was 30–35 mg/day and patients who remained on their first therapy course for greater than one year were maintained on 10–20 mg/day. Of patients who ever filled prednisone prescriptions, 163 of 294 (55.4%) were dispensed ≥2 distinct prednisone therapy courses (Table 3). Consequentially, the percent of the cohort with prednisone fills (by day since diagnosis), and the mean prednisone dose was variable (Figure 3). However, cohort-wide, 10–15% of patients (point prevalence) were prescribed prednisone therapy at any given time after diagnosis (1–2 years).

Figure 1:

Cumulative Percent of Patients with Prednisone Prescription Fills by Days from Sarcoidosis Diagnosis. Most patients ever started on prednisone begin treatment within the first 50 days of diagnosis, after which the rate slows and remains constant over the following 2 years.

Figure 2:

First Round of Prednisone Dose and Duration (by day). Duration of therapy (top) was typically short for the initial dose. Median therapy duration is 30 days and relatively few patients were initially treated with prednisone longer than 6 months. The daily prednisone dose (bottom) starts at approximately 32 mg, tapering over 6 months before plateauing (25 mg). Shaded regions denote the 95% CI.

Table 3:

Number of Patients by Rounds of Prednisone Treatment.*

| Number of Prednisone Rounds | Number of Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 428 (59.3%) |

| 1 | 131 (18.1%) |

| 2 | 80 (11.1%) |

| 3 | 47 (6.5%) |

| 4 | 15 (2.1%) |

| 5 | 12 (1.7%) |

| 6 | 7 (1.0%) |

| 7 | 2 (0.3%) |

Note: A new round of prednisone treatment is defined as having started >30 days from the end of the previous dispensing date plus the number of days supplied and the next dispensing date.

Figure 3:

Point Prevalence and Dose of Prednisone Use by Days Since Diagnosis. Patients stopping and restarting prednisone account for the “waves” observed in the prevalence and dose trends. Shaded region denotes the 95% CI.

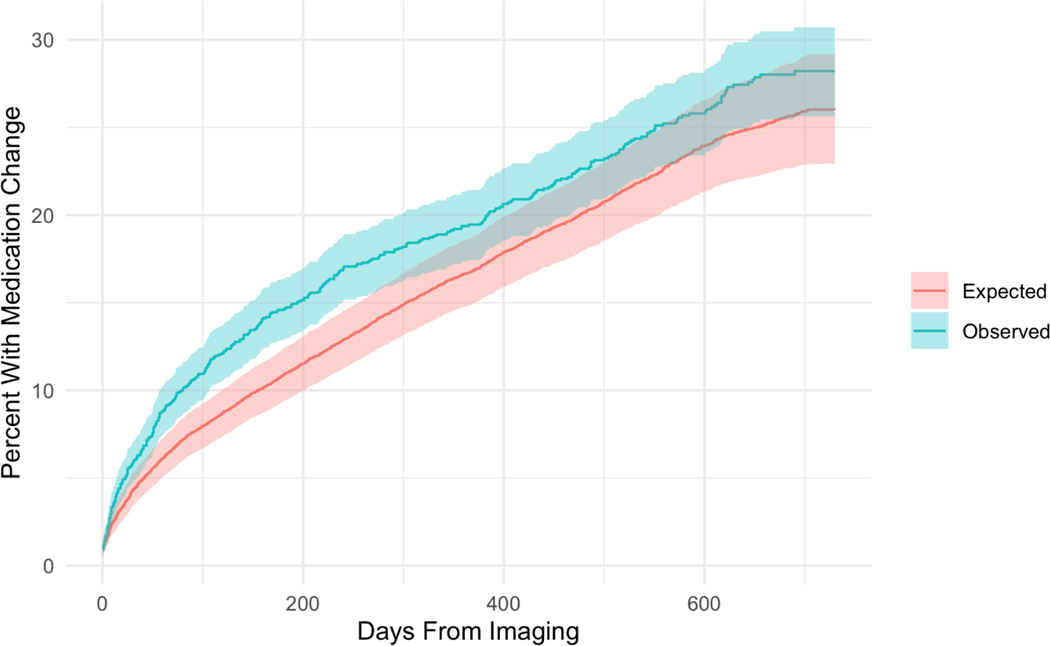

Greater average and cumulative prednisone dose during the first two years varied with baseline diagnostics and demographics, Table 4. Specifically, undergoing chest CT at baseline was associated with a greater daily average dose (+7.1 mg/day, 95% CI: 1.9, 12.2) and greater cumulative dose (+2,015 mg, 95% CI: 509, 3,520) over the first two years compared to those without a chest CT. African-American enrollees experienced a significantly greater cumulative dose (+1,845 mg, 95% CI: 123, 3,568) driven by trends in both longer duration, and daily average dose. Women had fewer days on therapy (−53.9, 95% CI: −103.2, −4.7) and a lower cumulative total dose (−1,718 mg, 95% CI: −3,011, −425). No other factors were associated with significant changes in prednisone duration, average daily dose, or cumulative dose during the first two years. Consistent with these two-year results, baseline chest CT was associated with a greater average daily dose (+6.9 mg, 95% CI: 0.0, 13.8) and total prednisone dose (1,043 mg, 95% CI: 219, 1,868) during the first course of therapy, compared to those without a baseline chest CT while females had a slightly lower total prednisone dose (−924 mg, 95% CI: −1,631, −216). We found a greater hazard of medication addition, removal, or dose change following chest imaging compared to a randomly selected procedure (HR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.38) (Figure 4).

Table 4:

Predictors of Prednisone Duration, Average Dose, and Cumulative Dose. “Initial Course” refers to the initial prednisone prescriptions plus all following prescriptions without a ≥30 day break. “First Two Years” refers to the total prednisone use (within any number of courses) during the first two years following diagnosis. The sample size for all models is 295 (total number of prednisone users).

| Initial Course | First Two Years | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration | Average dose (mg) | Total Dose (mg) | Duration | Average dose (mg) | Total Dose (mg) | |

| Intercept | 74.8 (32.5, 117) | 39.5 (29.4, 49.6) | 1,885 (671, 3,100) | 160.7 (76.3, 245.2) | 39.8 (32.2, 47.4) | 4,336 (2,118, 6,555) |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–39 | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| 40–49 | −4.5 (−45.0, 36.1) | −3.9 (−13.6, 5.8) | −48 (−1,212, 1,116) | 24.3 (−56.7, 105.2) | −6.3 (−13.6, 0.9) | 37 (−2, 90, 2,163) |

| 50–59 | 3.2 (−34.9, 41.4) | −0.8 (−9.9, 8.3) | 682 (−413, 1,778) | 29.1 (−47.1, 105.3) | −4.2 (−11.1, 2.6) | 1,131 (−870, 3,133) |

| 60+ | 13.2 (−27.0, 53.5) | 1.4 (−8.3, 11.0) | −2 (−1,160, 1,156) | 38.6 (−41.9, 119.1) | −4.7 (−11.9, 2.5) | −286 (−2,400, 1,829) |

| Female | −22.4 (−47.0, 2.2) | −4.0 (−9.9, 1.9) | −924 (−1,631, −216) | −53.9 (−103.2, −4.7) | −2.9 (−7.3, 1.6) | −1,718 (−3,011, −425) |

| Race | ||||||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Black | 9.3 (−23.5, 42.2) | −0.7 (8.5, 7.2) | 806 (−136, 1,749) | 30.3 (−35.3, 95.8) | −0.1 (−6.0, 5.7) | 1,845 (123, 3,568) |

| Other | −29.6 (−103.1, 43.8) | −7.2 (−24.8, 10.4) | −1,137 (−3,246, 973) | 0.0 (−146.7, 146.7) | −4.2 (−17.4, 9.0) | −479 (−4,333, 3,375) |

| PFT at Baseline | 23.4 (−5.8, 52.6) | −6.9 (−13.9, 0.00) | 180 (−659, 1,018) | 5.8 (−52.5, 64.2) | −3.4 (−8.6, 1.8) | −245 (−1,777, 1,287) |

| Chest Imaging at Baseline | ||||||

| X-Ray | −1.6 (−29.5, 26.4) | −0.5 (−7.2, 6.2) | 97 (−707, 900) | −27.1 (−83.0, 28.7) | −1.6 (−6.6, 3.5) | −619 (−2,087, 848) |

| CT | 9.8 (−18.9, 38.5) | 6.9 (0.00, 13.8) | 1,043 (219, 1,868) | 36.9 (−20.4, 94.2) | 7.1 (1.9, 12.2) | 2,015 (50.9, 3,521) |

Figure 4:

Kaplan-Meier time-to-event curves for medication changes following procedures. Observed series is the curve for time-to-medication change following a chest CT or CXR procedure. The expected series is the result of 10,000 samples of the same number of procedures selected at random. A greater percentage of the population has a medication change immediately following a chest imaging procedure than would be expected. After approximately 100 days, the rate of change in medication in both groups is similar. Solid lines denote the Kaplan-Meier estimated cumulative incidence and shaded regions denote the 95% CI.

PFTs were performed infrequently during baseline (+/− 60 days from diagnosis), with 148 patients (20.5%) having a recorded baseline PFT. Of these, PFT metrics were largely normal (Table 5). After the index date (3–15 months), PFTs were rare, with only 108 (15.0%) having one or more PFT during this interval. A total of 61 patients (8.4%) had a PFT during both baseline and follow-up and there was no statistically significant change in any PFT metric between baseline and follow-up. Only seven subjects had abnormal FVC (baseline FVC percent predicted <70%), and we were therefore under-powered to detect changes in therapy based on pulmonary function at baseline.

Table 5:

Pulmonary Performance Metrics at Baseline and Follow-up. For subjects with a PFT during both baseline and followup, a change was computed. All values are either mean or counts (standard deviation or percent).

| All PFTs at Baseline | All PFTs during Follow-up | Cohort with Both Baseline and Follow-up Measurements | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 148 (20.5%) | N = 108 (15.0%) | N = 61 (8.4%) | |

| FEV1 | 85.1 (17.3) [n = 147] | 86.6 (19.1) | 0.1 (8.4) |

| FVC | 93.1 (15.7) | 93.5 (18.1) | −1.1 (6.5) |

| FEV1/FVC | 72.6 (8.7) | 73.9 (8.5) | 0.8 (5.0) |

| DLCO | 81.9 (18.5) [n = 130] | 80.0 (18.9) [n = 88] | −1.3 (8.9) [n = 45] |

The 68 ever-users of corticosteroid-sparing drugs were more likely to have a PFT at baseline, use prednisone in the first two years, and be female (Table 6). Only prednisone use was significantly associated with the total duration of corticosteroid-sparing drugs; prednisone users were on steroid-sparing agents for 68 additional days on average in the first two years (95% CI: 49 to 93). In total, 43 subjects had ≥1 filling event for methotrexate, 24 for azathioprine, ≤10 for mycophenolate, leflunomide and infliximab.

Table 6:

Predictors of Use and Duration of Steroid Sparing Agents in the Two Years Following Sarcoidosis Diagnosis.

| Ever Start Steroid-Sparing (Odds Ratios) | Duration in First Two Years (Days) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| < 40 | Reference | Reference |

| 40–50 | 0.63 (0.26, 1.50) | 3.4 (−32.8, 39.6) |

| 50–60 | 0.53 (0.24, 1.23) | −1.7 (−35.8, 32.3) |

| 60+ | 0.53 (0.23, 1.30) | −5.4 (−41.1, 30.2) |

| Female | 1.94 (1.08, 3.64) | 6.3 (−16.0, 28.7) |

| Race | ||

| White | Reference | Reference |

| Black | 1.42 (0.69, 2.78) | 28.9 (−3.0, 60.7) |

| Other | 0.53 (0.03, 2.87) | 0.4 (−54.7, 55.5) |

| PFT at Baseline | 2.03 (1.07, 3.80) | 24.4 (−3.6, 52.4) |

| Chest Imaging at Baseline | ||

| Chest X-Ray | 1.01 (0.54, 1.94) | −16.8 (−40.6, 7.0) |

| Chest CT | 0.98 (0.51, 1.83) | 4.5 (−22.4, 31.4) |

| Used Prednisone | 8.78 (4.64, 18.12) | 67.6 (45.5, 89.8) |

Discussion

We found that 41% of patients with sarcoidosis required therapy within two years of diagnosis, and most patients started their first course of prednisone within 100 days of diagnosis (half of these within 30 days). For patients on immunosuppressive therapy, nearly all discontinued their first round by six months, although half of these patients then required another course. After one year, approximately 5% of our cohort required immunosuppressive therapy, indicating that a small proportion of the cohort remain on prednisone therapy for prolonged periods, suggestive of more persistent clinically active disease.

In terms of other clinical assessments to describe natural history, objective measures were not systematically obtained on a population level. Traditionally, FVC has been the primary outcome measure for disease progression among patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis (6). However, PFT metrics in our cohort were typically normal, did not significantly change between baseline and follow-up (in both treated and untreated patients) and were infrequently ordered. This was a consistent finding, even as we tightened our case definition to those patients who underwent lung biopsy (data not shown). This finding indicates that PFTs are not routinely used to guide treatment decisions, and thus do not adequately capture clinical signs and symptoms that a patient may experience over the course of disease. Continued work on novel clinical assessments or composite endpoints is warranted for trial endpoints and standardization of clinical protocols to describe the natural history of sarcoidosis, and evaluate treatment effects (7).

In contrast to PFTs, chest imaging was frequently performed in our cohort, and changes to prednisone prescriptions followed chest imaging. A chest CT at baseline was associated with increased odds of prednisone use and higher total prednisone utilization, indicating that clinicians may use imaging to drive treatment decisions. These results were unsurprising, given that CT imaging has become commonplace for clinicians treating sarcoidosis; however, the utility of CT scans over CXR in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis has been debated (8, 9). Currently, there are no evidence-based guidelines available to guide CT imaging use to treat or manage the disease, nor has CT imaging been established as a monitoring biomarker. Traditionally, use of CXR as an outcome measure has been limited by intraobserver variability, lack of validated imaging scoring, and variable correlation with symptoms (10, 11). Emerging work in radiomics may help further clarify CT as a diagnostic and monitoring measure (12). Importantly, the role of CT in sarcoidosis should be further clarified given potential risks of repeated radiation exposure (13).

Additionally, our results show that patients with sarcoidosis are frequently treated (often repeatedly) with corticosteroids, with risk of treatment side effects. Prednisone use was common (41% of cohort) and 5% in our population had a prolonged chronic course. In our cohort, days taking corticosteroid or steroid-sparing medication were high, with a substantial cumulative dose, particularly for African Americans. Additionally, patients started on prednisone commence with doses >30 mg/day and have high cumulative doses, exceeding 1–2 grams over a three-month (or longer) period. For the minority of patients with prolonged therapy courses, doses were maintained at 10–20 mg/day for greater than one year. The potential toxicity of this corticosteroid use is notable; prior studies show a dose- and time-dependent increased risk of toxicity including obesity, cardiovascular risk, hypertension, and osteoporosis in patients with sarcoidosis and other diseases requiring repeated prednisone use (14–17). Similarly, corticosteroids in patients with sarcoidosis have deleterious effects on quality of life, and are associated with increased emergency department visits (18). The high doses of corticosteroid therapy for patients with sarcoidosis highlights the need to develop alternative medications and therapies that would reduce treatment side effects and toxicities.

Our results differ from a study evaluating therapy duration in a subset of patients enrolled in the ACCESS study (A Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis), where 24% of subjects remained on therapy for 18–24 months (19). Historically, some data have suggested prolonged courses of corticosteroids, based upon a higher rate of relapse with shorter courses of therapy (20–22). However, increasing evidence suggests subgroups of patients may respond quickly to therapy (23, 24). Additionally, some patients may benefit from quicker de-escalation of prednisone with the addition of a steroid-sparing agent to avoid side effects if chronic therapy is required (24, 25). Discrepancy between our results and other cohorts may reflect populations with differing disease severity (e.g. academic medical centers vs. community-based populations) or evolving treatment paradigms.

Limitations of this study are related to the retrospective nature of the cohort and the difficulty of studying sarcoidosis using observational data. First, the use of administrative insurance data results in a risk of non-random loss to follow-up. While attrition is low among KPNW members (as of June 2017, annual retention was 91.4% for medical members), imposing two years of lookback and two years of follow-up reduces our sample size. Our requirement of four years of enrollment centered on the index date reduces our sample by 45%, somewhat more than the 30% expected from a 91.4% annual retention rate. This may represent a risk of non-random loss to follow-up and healthy worker bias. Second, missing or uncollected data, such as PFTs, are frequent, and likely reflect the lack of standardized guidelines for outcome assessment. Even nationally, follow-up schedules are not well-established and may vary depending on disease severity and individual patient presentation. Therefore, studying disease change and treatment response is difficult without repeated, structured, and granular outcome assessments. Third, symptoms, or other disease information such as Scadding stage, are not coded elements in structured EHR data. For this reason, we also do not have information regarding the precise organ or symptom being treated by the medications prescribed. While in some instances, prednisone may be used for other conditions, roughly half of prednisone users initiated within 30 days of sarcoidosis diagnosis. While these data may be observed and even recorded by the provider, these are likely only reported in the encounter note, due to the lack of systematized assessment tools. The presence of symptoms may supercede other objective findings to guide immunosuppressive treatment. Another potential limitation of retrospective cohorts for natural history studies include length-biased sampling, but we do not think that this plays a large role in our results, as the cohort period was 20 years, and we only included patients of whom we had four full years of data surrounding their diagnosis. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to other populations or health care systems. For example, as is common practice, KPNW maintains a formulary of approved medications, which may limit the use of off-label steroid-sparing agents. Therefore, there may be differences in prescribing practices with other health systems. While we were able to collect information regarding clinical specialties of the providers who treated these cases, a lack of standardized protocols translates to variable sarcoidosis treatment among providers and regions. Last, the general population of the region served by KPNW has a small African American population (generally under 2%). Compared to the general population in the region of our study, African Americans are overrepresented in our cohort; however, absolute numbers remain low (n = 96), reducing our power and ability to understand variance in steroid use by race.

Despite our limitations, we clearly demonstrate that a significant proportion of patients with sarcoidosis are prescibed immunosuppressive therapy, with a small proportion requiring prolonged treatment. Our results also show that PFTs, while recommended and common in studies, are frequently normal; therefore, PFT results do not appear to drive clinical decision making. Future studies, where data are collected prospectively and purposefully at uniform intervals are needed. Without such studies, it will be difficult to describe the natural history of disease necessary to design interventions and to evaluate potential therapies.

Footnotes

CRediT author statement

Jacob Simmering: Conceptualization, software, formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Review & Editing. Emma M Stapleton: Writing – Review & Editing. Philip M Polgreen: Conceptualization. Jennifer Kuntz: Resources, Writing – Review & Editing. Alicia K Gerke: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Kaufmann P, Pariser AR, Austin C. From scientific discovery to treatments for rare diseases - the view from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences - Office of Rare Diseases Research. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1):196. Epub 2018/11/08. doi: 10.1186/s13023-018-0936-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, Bonham CA, Morgenthau AS, Patterson KC, Abston E, Bernstein RC, Blankstein R, Chen ES, Culver DA, Drake W, Drent M, Gerke AK, Ghobrial M, Govender P, Hamzeh N, James WE, Judson MA, Kellermeyer L, Knight S, Koth LL, Poletti V, Raman SV, Tukey MH, Westney GE, Baughman RP. Diagnosis and Detection of Sarcoidosis. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(8):e26–e51. Epub 2020/04/16. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202002-0251ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagai S, Handa T, Ito Y, Ohta K, Tamaya M, Izumi T. Outcome of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29(3):565–74, x. Epub 2008/06/10. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zych D, Krychniak W, Pawlicka L, Zielinski J. Sarcoidosis of the lung. Natural history and effects of treatment. Sarcoidosis. 1987;4(1):64–7. Epub 1987/03/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FDA. Rare Diseases: Natural History Studies for Drug Development 2019.

- 6.Baughman RP, Drent M, Culver DA, Grutters JC, Handa T, Humbert M, Judson MA, Lower EE, Mana J, Pereira CA, Prasse A, Sulica R, Valyere D, Vucinic V, Wells AU. Endpoints for clinical trials of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2012;29(2):90–8. Epub 2013/03/07. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moller DR. Negative clinical trials in sarcoidosis: failed therapies or flawed study design? Eur Respir J. 2014;44(5):1123–6. Epub 2014/11/02. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00156314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cottin V, Muller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis from bench to bedside: a state-of-the-art series for the clinician. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(1):14–6. Epub 2012/07/04. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00070712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mana J, Teirstein AS, Mendelson DS, Padilla ML, DePalo LR. Excessive thoracic computed tomographic scanning in sarcoidosis. Thorax. 1995;50(12):1264–6. Epub 1995/12/01. doi: 10.1136/thx.50.12.1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baughman RP, Shipley R, Desai S, Drent M, Judson MA, Costabel U, du Bois RM, Kavuru M, Schlenker-Herceg R, Flavin S, Lo KH, Barnathan ES, Sarcoidosis I. Changes in chest roentgenogram of sarcoidosis patients during a clinical trial of infliximab therapy: comparison of different methods of evaluation. Chest. 2009;136(2):526–35. Epub 2009/04/28. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Judson MA, Gilbert GE, Rodgers JK, Greer CF, Schabel SI. The utility of the chest radiograph in diagnosing exacerbations of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Respirology. 2008;13(1):97–102. Epub 2008/01/17. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan SM, Fingerlin TE, Mroz M, Barkes B, Hamzeh N, Maier LA, Carlson NE. Radiomic measures from chest high-resolution computed tomography associated with lung function in sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(2). Epub 2019/06/15. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00371-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sodickson A, Baeyens PF, Andriole KP, Prevedello LM, Nawfel RD, Hanson R, Khorasani R. Recurrent CT, cumulative radiation exposure, and associated radiation-induced cancer risks from CT of adults. Radiology. 2009;251(1):175–84. Epub 2009/04/01. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2511081296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan NA, Donatelli CV, Tonelli AR, Wiesen J, Ribeiro Neto ML, Sahoo D, Culver DA. Toxicity risk from glucocorticoids in sarcoidosis patients. Respir Med. 2017;132:9–14. Epub 2017/12/13. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sweiss NJ, Lower EE, Korsten P, Niewold TB, Favus MJ, Baughman RP. Bone health issues in sarcoidosis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2011;13(3):265–72. Epub 2011/02/18. doi: 10.1007/s11926-011-0170-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price DB, Trudo F, Voorham J, Xu X, Kerkhof M, Ling Zhi Jie J, Tran TN. Adverse outcomes from initiation of systemic corticosteroids for asthma: long-term observational study. J Asthma Allergy. 2018;11:193–204. Epub 2018/09/15. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S176026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ungprasert P, Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Risk of cardiovascular disease among patients with sarcoidosis: a population-based retrospective cohort study, 1976–2013. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(2). Epub 2017/02/10. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01290-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Judson MA, Chaudhry H, Louis A, Lee K, Yucel R. The effect of corticosteroids on quality of life in a sarcoidosis clinic: the results of a propensity analysis. Respir Med. 2015;109(4):526–31. Epub 2015/02/24. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baughman RP, Judson MA, Teirstein A, Yeager H, Rossman M, Knatterud GL, Thompson B. Presenting characteristics as predictors of duration of treatment in sarcoidosis. QJM. 2006;99(5):307–15. Epub 2006/04/06. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcl038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Judson MA. An approach to the treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis with corticosteroids: the six phases of treatment. Chest. 1999;115(4):1158–65. Epub 1999/04/20. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.4.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gottlieb JE, Israel HL, Steiner RM, Triolo J, Patrick H. Outcome in sarcoidosis. The relationship of relapse to corticosteroid therapy. Chest. 1997;111(3):623–31. Epub 1997/03/01. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baughman RP, Judson MA. Relapses of sarcoidosis: what are they and can we predict who will get them? Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):337–9. Epub 2014/02/04. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00138913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broos CE, Wapenaar M, Looman CW, van den Toorn LM, Overbeek MJ, Grootenboers MJ, Heller R, Mostard RL, Poell LH, Hoogsteden HC. Daily home spirometry to detect early steroid treatment effects in newly treated pulmonary sarcoidosis. European Respiratory Journal. 2018;51(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Culver DA, Judson MA. New advances in the management of pulmonary sarcoidosis. bmj. 2019;367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baughman RP, Valeyre D, Korsten P, Mathioudakis AG, Wuyts WA, Wells A, Rottoli P, Nunes H, Lower EE, Judson MA. ERS clinical practice guidelines on treatment of sarcoidosis. European Respiratory Journal. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]