From the Authors:

We thank Drs. Mumin, McKenzie, and Spronk for their comments on our article that described a randomized of trial of thiamine for kidney protection in septic shock (1, 2). They raise important points, and we appreciate the opportunity to respond and share additional background regarding certain design choices for the TRPSS (Thiamine for Renal protection in Septic Shock) trial.

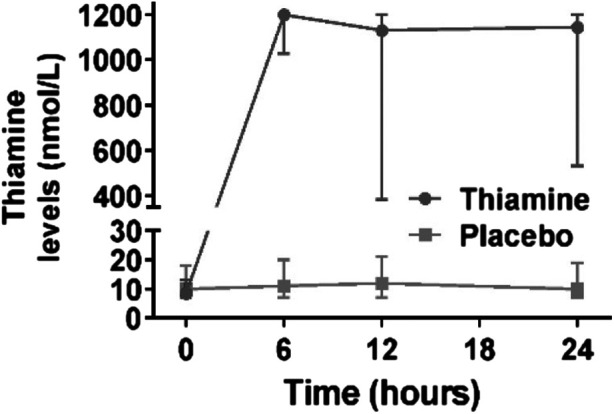

The first point raised concerns about the selection of thiamine dose in TRPSS. The letter authors appropriately note that in critical illness, both the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of thiamine may be altered. We agree that the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of parenteral thiamine in sepsis are likely abnormal, and the optimal dose of thiamine is not known. The dose selected (200 mg twice daily) was chosen for consistency with our prior randomized trial of thiamine in septic shock (3). In that trial, the dose of 200 mg of thiamine rapidly and dramatically increased plasma thiamine concentrations (Figure 1). The letter authors are correct, however, that this dose may be insufficient in sepsis, especially when neurologic outcomes such as delirium are considered and adequate doses to cross the blood–brain barrier are necessary. We note, however, that even doses in routine clinical use for Wernicke’s encephalopathy are based on extremely limited data (4), and additional research regarding the dosing of thiamine in critical illness is needed.

Figure 1.

Plasma thiamine concentrations over time in the thiamine in septic shock trial. Values represent means, with error bars representing SDs.

Delirium in the TRPSS trial was measured using the Confusion Assessment Method in the Intensive Care Unit tool. The Confusion Assessment Method in the Intensive Care Unit is a validated tool for the assessment of delirium in the ICU and is measured and recorded clinically by bedside ICU nurses. Reducing delirium was not the primary focus of TRPSS; however, we agree with the letter authors that thiamine is a potential therapy for delirium attenuation in critical illness (5). A study focused on delirium may indeed opt to use a higher dose of thiamine to ensure adequate concentration across the blood–brain barrier.

Last, the optimal approach to thiamine measurement in critical illness is not known. The approach used in TRPSS is the same as that of our prior studies (3, 6–8), including the Thiamine in Septic Shock trial, in which there was lower mortality in the thiamine-deficient group if thiamine was administered as compared with placebo (3). We agree that there may be advantages to measuring thiamine in whole blood, but it is also possible that this approach is more specific but less sensitive and may result in a number of patients with thiamine deficiency who are not identified. Indeed, given the results of this trial, measurement of thiamine in whole blood would have shown either similar findings (i.e., a differential effect of thiamine with greater impact in the thiamine-deficient group) or no heterogeneity of treatment effect based on thiamine concentration (perhaps confirming that whole blood may be more specific but less sensitive). Along those lines, it is not clear what thiamine concentration is adequate in sepsis, and it is possible that patients with concentrations generally considered to be in the normal range actually have thiamine deficiency.

In sum, we agree with the important points raised in the authors’ letter. We look forward to growing the evidence base in thiamine supplementation during critical illness in future larger studies in which these more detailed questions can be better answered.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: A.M. authored the first draft of the work. All the authors provided critical input into the final version and approved of the final product.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202310-1740LE on November 16, 2023

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Moskowitz A, Berg KM, Grossestreuer AV, Balaji L, Liu X, Cocchi MN, et al. Thiamine for Renal Protection in Septic Shock (TRPSS): a randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2023;208:570–578. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202301-0034OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moskowitz A, Grossestreuer A, Berg K, Balaji L, Berlin N, Gong J, et al. Thiamine for Renal Protection in Septic Shock: a randomized trial [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2023;207:A6378. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202301-0034OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Donnino MW, Andersen LW, Chase M, Berg KM, Tidswell M, Giberson T, et al. Center for Resuscitation Science Research Group Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of thiamine as a metabolic resuscitator in septic shock: a pilot study. Crit Care Med . 2016;44:360–367. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Galvin R, Bråthen G, Ivashynka A, Hillbom M, Tanasescu R, Leone MA, EFNS EFNS guidelines for diagnosis, therapy and prevention of Wernicke encephalopathy. Eur J Neurol . 2010;17:1408–1418. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McKenzie CA, Page VJ, Strain WD, Blackwood B, Ostermann M, Taylor D, et al. Parenteral thiamine for prevention and treatment of delirium in critically ill adults: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev . 2020;9:131. doi: 10.1186/s13643-020-01380-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andersen LW, Holmberg MJ, Berg KM, Chase M, Cocchi MN, Sulmonte C, et al. Thiamine as an adjunctive therapy in cardiac surgery: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II trial. Crit Care . 2016;20:92. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1245-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berg KM, Grossestreuer AV, Andersen LW, Liu X, Donnino MW. The effect of a single dose of thiamine on oxygen consumption in patients requiring mechanical ventilation for acute illness: a phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Explor . 2021;3:e0579. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moskowitz A, Graver A, Giberson T, Berg K, Liu X, Uber A, et al. The relationship between lactate and thiamine levels in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis. J Crit Care . 2014;29:182.e5–182.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]