Abstract

Context:

Despite current advances in antiemetic treatments, between 19% to 58% of oncology patients experience chemotherapy-induced nausea (CIN).

Objectives:

Aims of this post hoc exploratory analysis were to determine occurrence, severity, and distress of CIN and evaluate for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, symptom severity, stress; and quality of life (QOL) outcomes between oncology patients who did and did not report CIN in the week prior to CTX. Demographic, clinical, symptom, and stress characteristics associated with CIN occurrence were determined.

Methods:

Patients (n=1296) completed questionnaires that provided information on demographic and clinical characteristics, symptom severity, stress, and QOL. Univariate analyses evaluated for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, symptom severity, stress, and QOL scores between the two patient groups. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate for factors associated with nausea group membership.

Results:

Of the 1296 patients, 47.5% reported CIN. In the CIN group, 15% rated CIN as severe and 23% reported high distress. Factors associated with CIN included: less education; having childcare responsibilities; poorer functional status; higher levels of depression, sleep disturbance, evening fatigue, and intrusive thoughts; as well as receipt of CTX on a 14-day CTX cycle and receipt of an antiemetic regimen that contained serotonin receptor antagonist and steroid. Patients in the CIN group experienced clinically meaningful decrements in QOL.

Conclusions:

This study identified new factors (e.g., poorer functional status, stress) associated with CIN occurrence. CIN negatively impacted patients’ QOL. Pre-emptive and ongoing interventions may alleviate CIN occurrence in high risk patients.

Keywords: nausea, chemotherapy, antiemetics, cancer, stress, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

With the advent of antiemetic prophylaxis, significant progress has been made in the prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced vomiting (CIV).1 However, the management of chemotherapy-induced nausea (CIN) remains a significant clinical problem. While only 13% to 32% of patients report CIV, CIN occurs in 19% to 58% of oncology patients.1 Unrelieved CIN can lead to compromised nutritional status, decrements in quality of life (QOL), and discontinuation of cancer treatment.2

A number of studies used multivariate logistic regression analysis to determine demographic and clinical characteristics associated with CIN.2–9 In terms of demographic characteristics, findings are not consistent. While in three studies,2–4 age <50 years was associated with increased risk for CIN, in two studies,5,6 no age association was found. Similarly, while in three studies,2,3,5 female patients were more likely to report CIN, in three studies,2,6,7 no association was reported.

In terms of clinical characteristics, the most common risk factors for CIN include: a history of motion sickness,1,6,8 a history of morning sickness,1,8,10 malnutrition,11,12 and a history of nausea and emesis.1,9 In addition, the intrinsic emetogenic potential of the chemotherapy (CTX) regimen contributes to the occurrence of CIN.2,4 While in one study,2 decreased alcohol intake was shown to increase the risk for CIN, this association was not supported in other studies.8,9

Across six studies, pre-CTX nausea,2,9 pre-CTX anxiety,2,8,9,13 less than seven hours of sleep on the night before CTX,8 as well as higher levels of depression,5 and fatigue12,13 post-CTX were associated with the occurrence and severity of CIN. While most of the studies that evaluated for predictors of CIN had relatively large sample sizes, inconsistent findings may be related to: the variety of instruments used to assess nausea;3,5,6,8,11 lack of controls for ethnicity in the multivariate analyses;2,3,5,8 and diverse factors evaluated across these studies.3,6,8

While previous studies provide insights into risk factors for CIN, additional research is warranted. First, additional demographic and clinical characteristics associated with other common symptoms in oncology patients (e.g., ethnicity,14 education,5,15 adult/child care responsibilities,16 functional status,15,16 body mass index,11,12 comorbidities,16 and treatment-related factors5) need to be evaluated. Second, the intrinsic emetogenic potential of the CTX regimen and the type of antiemetic regimen patients received need to be included in a multivariate analysis. Finally, the impact of concurrent symptoms on the occurrence of CIN warrants investigation.

The stress associated with cancer and its treatment can lead to symptoms such as depression and anxiety.17 In a recent study of the effect of an integrated yoga program on CIN and CIV,18 the authors suggested that the positive effect of the intervention on these two symptoms was through a decrease in stress. However, no studies have evaluated for associations between perceived stress and the occurrence of CIN.

While the impact of cancer symptoms on QOL outcomes continues to be an area of active investigation,19–21 the majority of the studies on the associations between CTX-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) and QOL did not distinguish between CIN and CIV and/or were done in the context of clinical trials of antiemetics.22–24 In addition, most studies used a global measure of QOL and did not evaluate for associations between the occurrence of CIN and various domains of QOL (e.g., physical or social well-being).

Therefore, in a sample of oncology patients receiving CTX (n=1296), the purposes of this study were to evaluate for the occurrence, severity, and distress of CIN and evaluate for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, symptom severity, perceived stress, and QOL outcomes between patients who did and did not report CIN in the week prior to their next dose of CTX. In addition, we determined which demographic, clinical, symptom, and stress characteristics were associated with the occurrence of nausea.

METHODS

Patients and settings

This post hoc exploratory analysis analyzed data collected as part of a larger descriptive, longitudinal study that evaluated the symptom experience of oncology outpatients receiving CTX.25, 26 Patients were included if they: were ≥18 years of age; had a diagnosis of breast, gastrointestinal, gynecological, or lung cancer; had received CTX within the preceding four weeks; were scheduled to receive at least two additional cycles of CTX; were able to read, write, and understand English; and provided written informed consent. Patients were recruited from two Comprehensive Cancer Centers, one Veteran’s Affairs hospital, and four community-based oncology programs. The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California at San Francisco and by the Institutional Review Board at each of the study sites.

Study procedures

A total of 2234 patients were approached and 1343 consented to participate (60.1% response rate). The major reason for refusal was being overwhelmed with their cancer treatment. A research staff member approached eligible patients in the infusion unit and discussed participation in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all of the patients. Because of the stress associated with the first treatment, patients were recruited during their second or the third cycle of CTX. Depending on the length of their CTX cycle (i.e., 14-day, 21-day, or 28-day), patients completed all of the study questionnaires in their homes, a total of six times over the two cycles of CTX. The enrollment assessment (i.e., patients were asked to rate the occurrence, severity, and distress of nausea on average during the week prior to their next cycle of CTX) was used in this analysis to create the nausea groups. Medical records were reviewed for disease and treatment information.

Instruments

Demographic and clinical characteristics -

Demographic questionnaire obtained information on: age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, living arrangements, education, employment status, income, and past medical history. Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scale was used to evaluate functional status.27 Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (SCQ) evaluated the occurrence, treatment, and functional impact of thirteen common comorbid conditions.28 Total SCQ score ranges from 0 to 39. Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) evaluated alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence, and the consequences of alcohol abuse in the last 12 months.29 Smoking questionnaire assessed smoking history.30

Assessment of nausea -

Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) was used to assess nausea. Patients were asked to indicate whether or not they had experienced nausea in the past week (i.e., symptom occurrence). If they experienced nausea, they were asked to rate its frequency, severity, and distress.31 Patients’ assessment of nausea in the week prior to their next cycle of CTX (i.e., enrollment assessment) was used to dichotomize the sample. Patients who provided a rating for occurrence, frequency, severity, and/or distress for the nausea item were coded as having nausea. Patients who indicated “no” to the occurrence item were coded as not having nausea.

Assessment of other symptoms -

Associations between the occurrence of nausea and other common symptoms were evaluated using a number of valid and reliable instruments. Diurnal variations in fatigue and decrements in energy were evaluated using the Lee Fatigue Scale (LFS).32 State and trait anxiety were evaluated using the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventories.33 Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (CES-D).34 The quality of sleep was evaluated using the General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS).35 Difficulties with executive function were assessed using the Attentional Function Index (AFI).36 Occurrence of pain was evaluated using the Brief Pain Inventory.37

Assessment of stress –

Stress was assessed using disease-specific (i.e., Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R)38) and general (i.e., Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)39) stress measures. Three subscales in the IES-R evaluate the level of intrusion, avoidance, and hyperarousal associated with cancer and its treatment.40 PSS evaluates stress due to life circumstances. For both instruments, a higher score indicates greater stress.39

Assessment of QOL -

QOL was evaluated using disease-specific (i.e., QOL-Patient Version (QOL-PV)41) and generic (i.e., Medical Outcomes Study-Short Form-12 (SF-12)42) measures. The QOL-PV assesses four domains of QOL (i.e., physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being) as well as a total QOL score. Higher scores indicate a better QOL.41 The SF-12 consists of 12 questions about physical and mental health as well as overall health status. The SF-12 is scored into: physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores. Higher summary scores indicate a better QOL.42

Coding of the emetogenicity of the CTX regimens

Using the Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) guidelines,43 each CTX drug in the regimen was classified as having: minimal, low, moderate, or high emetogenic potential. The emetogenicity of the regimen was categorized into one of three groups (i.e., low/minimal, moderate, or high) based on the CTX drug with highest emetogenic potential.

An exception was made if a patient received doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide. When administered separately, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide are listed as having moderate emetogenic potential.43 When given together, the combination has high emetogenic potential.

Coding of the antiemetic regimens

Each antiemetic was coded as either a neurokinin-1 (NK-1) receptor antagonist, a serotonin receptor antagonist, a dopamine receptor antagonist, prochlorperazine, lorazepam, or a steroid. The antiemetic regimens were coded into one of four groups: none (i.e., no antiemetics administered); steroid alone or serotonin receptor antagonist alone; serotonin receptor antagonist and steroid; or NK-1 receptor antagonist and two other antiemetics (e.g., a serotonin receptor antagonist, dopamine receptor antagonist, prochlorperazine, lorazepam and/or a steroid).

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were calculated for demographic and clinical characteristics. For categorical variables, nonparametric tests were used to evaluate for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between patients who did and did not report CIN. For continuous variables, Independent Student’s t-tests were done to evaluate for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as symptom severity, perceived stress, and QOL scores between patients who did and did not report CIN. Spearman’s correlation was used to evaluate the relationships between the categorical variables. Effect sizes were determined using Cohen’s d statistic.44

Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate for predictors of nausea group membership. Only those characteristics that were significantly different in the univariate analyses between patients who did and did not report CIN were evaluated in the logistic regression analysis. A backwards stepwise approach was used to create a parsimonious model. Only predictors with a p-value of <0.05 were retained in the final model.

RESULTS

Nausea characteristics

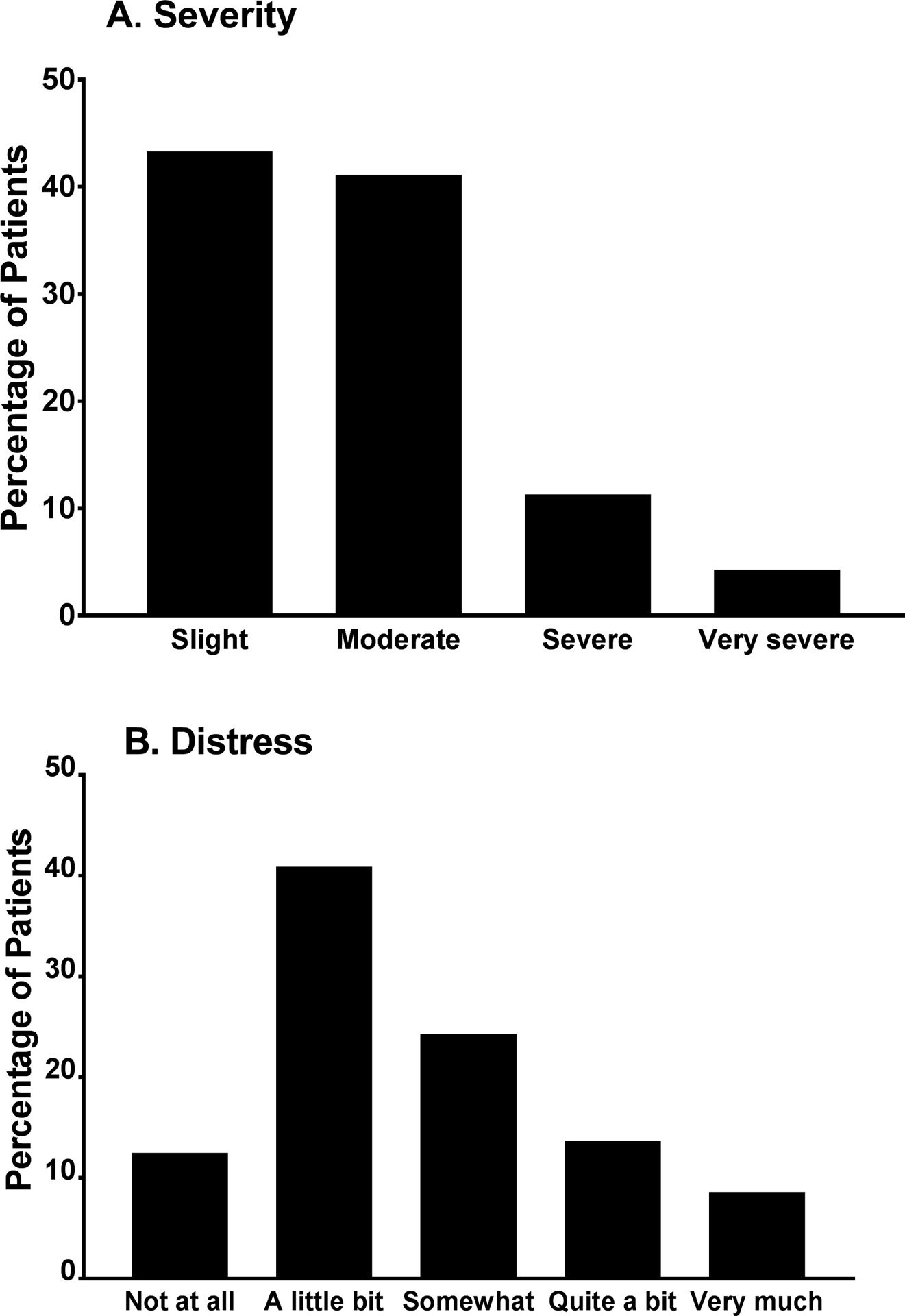

Of the 1296 patients who responded to the nausea item, 615 (47.5%) reported nausea in the week prior to their next cycle of CTX. Of the 615 patients who reported nausea, 95.3% (n=586) rated its severity. As illustrated in Figure 1A, 11% (n=66) of the patients reported “severe” and 4% (n=25) reported “very severe” nausea. Of the 615 patients who reported nausea, 95.0% (n=548) rated its distress. As illustrated in Figure 1B, 14% (n=80) of the patients reported “quite a bit” and 9% (n=50) reported “very much” distress related to nausea.

Figure 1:

Percentage of patients who reported each severity (A) and distress (B) rating for nausea on the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale

Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics

Compared to the no nausea group, patients who reported nausea were significantly younger and less educated; had a lower KPS score, and had an increased number of comorbidities, a higher comorbidity score, and a lower AUDIT score. A higher percentage of patients in the nausea group reported child care responsibilities, had a lower annual income, and were less likely to be employed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differences in Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Between Patients With and Without Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea

| Characteristic | No Nausea 52.5% (n = 681) |

Nausea 47.5% (n = 615) |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 58.64 (12.58) | 55.62 (11.93) | t = 4.41, p < 0.001 |

| Education (years) | 16.43 (2.97) | 15.87 (3.04) | t = 3.34, p = 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.15 (5.37) | 26.36 (6.02) | t = −0.64, p = 0.520 |

| Karnofsky Performance Status score | 83.36 (11.54) | 76.20 (12.41) | t = 10.50, p < 0.001 |

| Number of comorbidities | 2.30 (1.37) | 2.53 (1.50) | t = −2.82, p = 0.005 |

| SCQ score | 5.14 (2.90) | 5.87 (3.48) | t = −4.10, p < 0.001 |

| AUDIT score | 3.17 (2.52) | 2.76 (2.44) | t = 2.39, p = 0.017 |

| Time since cancer diagnosis (years) | 2.07 (3.99) | 1.79 (3.61) | U, p = 0.230 |

| Time since diagnosis (median) | 0.44 | 0.41 | |

| Number of prior cancer treatments | 0.77 (0.42) | 0.73 (0.44) | t = 1.50, p = 0.132 |

| Number of metastatic sites including lymph node involvement | 1.28 (1.21) | 1.18 (1.22) | t = 1.43, p = 0.153 |

| Number of metastatic sites excluding lymph node involvement | 0.81 (1.03) | 0.73 (1.04) | t = 1.32, p = 0.188 |

| % (n) | % (n) | ||

| Gender* | FE, p = 0.257 | ||

| Female | 76.2 (519) | 79.0 (486) | |

| Male | 23.6 (161) | 21.0 (129) | |

| Transgender | 0.2 (1) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Ethnicity | X2 = 5.57, p = 0.135 | ||

| White | 72.8 (490) | 67.1 (407) | |

| Black | 6.4 (43) | 8.1 (49) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 11.4 (77) | 12.7 (77) | |

| Hispanic Mixed or Other | 9.4 (63) | 12.2 (74) | |

| Married or partnered (% yes) | 64.6 (435) | 64.0 (388) | FE, p = 0.861 |

| Lives alone (% yes) | 21.6 (145) | 21.9 (133) | FE, p = 0.946 |

| Child care responsibilities (% yes) | 18.5 (124) | 26.2 (157) | FE, p = 0.001 |

| Care of adult responsibilities (% yes) | 7.1 (44) | 8.7 (48) | FE, p = 0.328 |

| Born prematurely (% yes) | 4.4 (29) | 6.4 (37) | FE, p = 0.163 |

| Currently employed (% yes) | 37.8 (255) | 32.4 (197) | FE, p = 0.047 |

| Income | KW, p < 0.001 | ||

| < $30,000 | 12.5 (75) | 25.0 (139) | |

| $30,000 to < $70,000 | 22.1 (133) | 19.7 (110) | |

| $70,000 to < $100,000 | 17.0 (102) | 16.9 (94) | |

| ≥ $100,000 | 48.4 (291) | 38.4 (214) | |

| Specific comorbidities (% yes) | |||

| Heart disease | 6.9 (47) | 4.6 (28) | FE, p = 0.075 |

| High blood pressure | 31.1 (212) | 29.6 (182) | FE, p = 0.586 |

| Lung disease | 11.2 (76) | 11.5 (71) | FE, p = 0.861 |

| Diabetes | 7.2 (49) | 10.9 (67) | FE, p = 0.025 |

| Ulcer or stomach disease | 3.8 (26) | 6.0 (37) | FE, p = 0.071 |

| Kidney disease | 1.5 (10) | 1.5 (9) | FE, p = 1.000 |

| Liver disease | 6.0 (41) | 6.8 (42) | FE, p = 0.572 |

| Anemia or blood disease | 10.4 (71) | 15.0 (92) | FE, p = 0.015 |

| Depression | 15.1 (103) | 23.7 (146) | FE, p < 0.001 |

| Osteoarthritis | 12.5 (85) | 11.7 (72) | FE, p = 0.733 |

| Back pain | 21.9 (149) | 29.6 (182) | FE, p = 0.002 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 3.8 (26) | 2.6 (16) | FE, p = 0.272 |

| Exercise on a regular basis (% yes) | 73.4 (493) | 68.5 (408) | FE, p = 0.063 |

| Smoking current or history of (% yes) | 36.3 (244) | 34.5 (208) | FE, p = 0.520 |

| Cancer diagnosis | X2 = 5.46, p = 0.141 | ||

| Breast | 40.5 (276) | 39.5 (243) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 28.5 (194) | 33.3 (205) | |

| Gynecological | 19.2 (131) | 15.3 (94) | |

| Lung | 11.7 (80) | 11.9 (73) | |

| Type of prior cancer treatment | X2 = 4.73, p = 0.193 | ||

| No prior treatment | 23.4 (155) | 26.9 (161) | |

| Only surgery, CTX, or RT | 42.7 (238) | 41.6 (249) | |

| Surgery & CTX, or Surgery & RT, or CTX & RT | 21.7 (144) | 17.7 (106) | |

| Surgery & CTX & RT | 12.2 (81) | 13.7 (82) | |

| CTX cycle length | X2 = 17.77, p < 0.001 | ||

| 14 day cycle | 37.2 (253) | 48.3 (297) | 0 < 1 |

| 21 day cycle | 56.2 (382) | 44.7 (275) | 0 > 1 |

| 28 day cycle | 6.6 (45) | 7.0 (43) | NS |

| Emetogenicity of CTX | X2 = 14.88, p = 0.001 | ||

| Minimal/Low | 21.4 (146) | 15.9 (98) | 0 > 1 |

| Moderate | 62.6 (426) | 60.5 (372) | NS |

| High | 16.0 (109) | 23.6 (145) | 0 < 1 |

| Antiemetic regimens | X2 = 19.82, p < 0.001 | ||

| None | 8.2 (56) | 5.9 (36) | NS |

| Steroid alone or serotonin receptor antagonist alone | 24.1 (164) | 16.4 (101) | 0 > 1 |

| Serotonin receptor antagonist and steroid | 46.5 (317) | 48.9 (301) | NS |

| NK-1 receptor antagonist and two other antiemetics | 21.1 (144) | 28.8 (177) | 0 < 1 |

Abbreviations: AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, CTX = chemotherapy, FE = Fisher’s Exact test, kg = kilograms, KW = Kruskal Wallis test, m2 = meter squared, NK-1 = Neurokinin-1, NS = not significant, RT = radiation therapy, SCQ = Self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire, SD = standard deviation, U = Mann-Whitney U test, X2 = Chi square

Chi Square test done without the transgender participant

Patients in the nausea group were more likely to have diabetes, anemia or blood disease, depression, and back pain. In terms of cycle length, a higher percentage of patients in the nausea group received CTX on a 14-day cycle compared to those in the no nausea group. A lower percentage of patients in the nausea group received CTX on a 21-day cycle compared to those in the no nausea group. In terms of emetogenicity of the regimen, a higher percentage of patients in the nausea group received highly emetogenic CTX. In terms of the antiemetic regimen, while a lower percentage of patients in the nausea group received a steroid alone or serotonin receptor antagonist alone compared to the no nausea group, a higher percentage of these patients received a NK-1 receptor antagonist and two other antiemetics compared to the no nausea group.

Differences in symptom severity

Compared to the no nausea group, patients who reported nausea had significantly higher depression, trait anxiety, state anxiety, sleep disturbance, morning and evening fatigue scores and lower attentional function, morning, and evening energy scores. A significantly higher percentage of patients in the nausea group reported pain (Table 2).

Table 2.

Differences in Symptom Severity Scores Between Patients With and Without Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea

| Symptom | Clinically Meaningful Cut-off Scores | No Nausea 52.5% (n = 681) |

Nausea 47.5% (n = 615) |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| CES-D score | ≥16.0 | 10.29 (8.56) | 15.65 (10.14) | t = −10.08, p < 0.001 |

| Trait Anxiety Inventory score | ≥32.2 | 33.06 (9.82) | 37.32 (10.69) | t = −7.34, p < 0.001 |

| State Anxiety Inventory score | ≥31.8 | 31.23 (11.07) | 36.66 (13.19) | t = −7.88, p < 0.001 |

| Attentional Function Index score | 6.81 (1.70) | 5.95 (1.80) | t = 8.76, p < 0.001 | |

| >7.5 High | ||||

| General Sleep Disturbance Scale | ≥43.0 | 46.82 (19.19) | 58.50 (19.46) | t = −10.68, p < 0.001 |

| Morning fatigue score (LFS) | ≥3.2 | 2.48 (2.00) | 3.80 (2.30) | t = −10.85, p < 0.001 |

| Evening fatigue score (LFS) | ≥5.6 | 4.89 (2.14) | 5.81 (2.05) | t = −7.80, p < 0.001 |

| Morning energy score (LFS) | ≤6.2 | 4.64 (2.29) | 4.14 (2.18) | t = 3.98, p < 0.001 |

| Evening energy score (LFS) | ≤3.5 | 3.68 (1.96) | 3.40 (2.11) | t = 2.45, p = 0.015 |

| Percentage of patients with pain (%, n) | 49.3 (332) | 64.8 (396) | FE, p < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale, FE = Fisher’s Exact, LFS = Lee Fatigue Scale, SD = standard deviation

Differences in perceived stress scores

Compared to the no nausea group, patients who reported nausea had a significantly higher PSS score. Patients in the nausea group reported significantly higher IES-R subscale (i.e., intrusion, avoidance and, hyperarousal) and total scores (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differences in Stress Scores Between Patients With and Without Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea

| Instrument | No Nausea 52.5% (n = 681) |

Nausea 47.5% (n = 615) |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Perceived Stress Scale score | 17.00 (7.86) | 20.07 (8.30) | t = −6.71, p < 0.001 |

| IES-R subscale scores | |||

| Intrusion | 0.76 (0.63) | 1.07 (0.75) | t = −7.82, p < 0.001 |

| Avoidance | 0.86 (0.66) | 1.05 (0.68) | t = −5.08, p < 0.001 |

| Hyperarousal | 0.52 (0.58) | 0.81 (0.72) | t = −7.86, p < 0.001 |

| IES-R total score | 16.00 (11.75) | 21.83 (13.84) | t = −7.95, p < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: IES-R = Impact of Event Scale-Revised, SD = standard deviation

Differences in QOL outcomes

Compared to the no nausea group, patients who reported nausea scored significantly lower on three QOL-PV subscales (i.e., physical, psychological, social well-being) as well as on the total score. For the SF-12, compared to the no nausea group, patients who reported nausea had significantly lower MCS and PCS scores (Table 4).

Table 4.

Differences in Quality of Life Outcomes Between Patients With and Without Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea

| Instrument | No Nausea 52.5% (n = 681) |

Nausea 47.5% (n = 615) |

Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Quality of Life Scale - Patient Version | |||

| Physical well-being | 7.31 (1.54) | 5.86 (1.76) | t = 15.55, p < 0.001 |

| Psychological well-being | 5.88 (1.79) | 5.05 (1.85) | t = 7.99, p < 0.001 |

| Social well-being | 6.21 (1.90) | 5.20 (2.01) | t = 9.06, p < 0.001 |

| Spiritual well-being | 5.38 (2.13) | 5.57 (2.01) | t = −1.66, p = 0.097 |

| Total score | 6.13 (1.36) | 5.33 (1.42) | t = 10.13, p < 0.001 |

| Short Form12 Health Survey | |||

| MCS score | 51.21 (9.73) | 46.55 (10.72) | t = 7.85, p < 0.001 |

| PCS score | 43.51 (10.08) | 38.73 (10.50) | t = 8.04, p < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: MCS = mental component summary, PCS = physical component summary, SD = standard deviation

Logistic regression analysis of factors associated with nausea group membership

In the logistic regression analysis to determine factors associated with nausea group membership, characteristics that were significantly different between the two nausea groups in the univariate analysis (p<0.05) were included in the backwards stepwise elimination model (i.e., age, education, KPS score, SCQ score, child care responsibilities, employment status, CTX cycle length, antiemetic regimen, all of the symptom scores, PSS total score, and the three IES-R subscale scores).

While AUDIT score and income were significantly different between the two groups, 456 patients did not complete the AUDIT and 138 patients did not report their income. Therefore, these two variables were not included in the regression analysis. Consequently, data from 1035 patients were included in the final model. The inter-correlations among the potential predictors were examined for possible multicolinearity. Because trait anxiety and state anxiety scores were highly correlated (r = .82), only trait anxiety was evaluated in the initial model.

Ten variables were retained in the final logistic regression model (Table 5). Those variables were education, child care responsibilities, KPS score, CES-D score, GSDS score, evening LFS score, PSS total score, IES-R intrusion subscale score, CTX cycle length, and antiemetic regimen. The overall model was significant (X2 = 189.99, p<0.001). Patients who were less educated; had child care responsibilities; had a lower KPS score; had higher depression, sleep disturbance, evening fatigue, and IES-R intrusion scores; and had a lower PSS score were more likely to be in the nausea group.

Table 5.

Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis Predicting Nausea Group Membership (n = 1035)

| Predictor | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education (years) | 0.93 | 0.89, 0.98 | 0.003 |

| Child care responsibilities | 1.42 | 1.03, 1.97 | 0.032 |

| Karnofsky Performance Status score | 0.96 | 0.95, 0.98 | < 0.001 |

| CES-D score | 1.03 | 1.00,1.05 | 0.026 |

| General Sleep Disturbance Scale score | 1.01 | 1.00,1.02 | 0.011 |

| Evening fatigue score (LFS) | 1.12 | 1.04,1.20 | 0.003 |

| Perceived Stress Scale score | 0.97 | 0.95, 0.99 | 0.015 |

| IES-R Intrusion subscale score | 1.35 | 1.04, 1.75 | 0.026 |

| CTX cycle length | 0.001 | ||

| 21 day cycle vs 14 day cycle | 0.58 | 0.44, 0.77 | < 0.001 |

| 28 day cycle vs 14 day cycle | 0.91 | 0.52, 1.61 | 0.754 |

| 21 day cycle vs 28 day cycle | 0.64 | 0.37, 1.11 | 0.110 |

| Antiemetic regimen | 0.019 | ||

| Steroid alone or serotonin receptor antagonist alone vs None | 0.88 | 0.48, 1.61 | 0.675 |

| Serotonin receptor antagonist and steroid vs None | 1.52 | 0.87, 2.67 | 0.141 |

| NK-1 receptor antagonist and two other antiemetics vs None | 1.37 | 0.75, 2.49 | 0.307 |

| Serotonin receptor antagonist and steroid vs Steroid alone or serotonin receptor antagonist alone | 1.73 | 1.21, 2.49 | 0.003 |

| Steroid alone or serotonin receptor antagonist alone vs NK-1 receptor antagonist and two other antiemetics | 0.64 | 0.42, 0.97 | 0.037 |

| Serotonin receptor antagonist and steroid vs NK-1 receptor antagonist and two other antiemetics | 1.12 | 0.80, 1.56 | 0.529 |

| Overall model fit: df = 13, X2 = 189.99, p < 0.001 | |||

Abbreviations: CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale, CI = confidence interval, CTX = chemotherapy, IES-R = Impact of Event Scale-Revised, LFS = Lee Fatigue Scale, NK-1 = neurokinin-1

CTX cycle length and antiemetic regimen groups were significant predictors of nausea group membership. Because CTX cycle length had three groups, three pairwise contrasts were examined to interpret the effect of cycle length. The significance criteria for each of the contrasts was 0.0125 (0.05/3). Only one contrast was significant. Compared to patients who received a 14-day cycle, patients who received a 21-day cycle of CTX had a 42% decrease in the odds of belonging to the nausea group. Because antiemetic regimen had four groups, six pairwise contrasts were examined to interpret the effect of antiemetic regimen. The significance criteria for each of the contrasts was 0.0083 (0.05/6). Only one contrast was significant. Compared to patients who received a steroid alone or a serotonin receptor antagonist alone, patients who received a serotonin receptor antagonist and steroid were 1.73 times more likely to be in the nausea group.

In the final regression model, the emetogenicity of the CTX regimen was not a significant predictor of CIN. A number of additional analyses were done to explore this unexpected finding. First, antiemetic regimen and emetogenicity of the CTX regimen were moderately correlated with each other (r = 0.50, p<0.001). Second, within the regression analysis, we tested for an interaction between emetogenicity of the CTX regimen and the antiemetic regimen. The interaction term was not significant. Third, we did another analysis where we removed cycle length from the analysis and forced emetogenicity of the CTX regimen into the regression analysis. Emetogenicity of the CTX was not a significant predictor of CIN group membership in this analysis (p=0.33).

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to evaluate the relative contribution of a comprehensive set of demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as symptom severity scores, and levels of perceived stress to the occurrence of nausea in the week prior to the patients’ next cycle of CTX. In addition, this study is the first to evaluate multiple domains of QOL in patients who did and did not report CIN.

Given previous occurrence rates of 19%1,45 to 58%,1,46 our 47.5% occurrence rate is quite high. Consistent with a previous report,11 15% of our patients reported that the severity of CIN was severe and 23% reported high levels of distress. These findings suggest that unrelieved CIN continues to be a significant problem during CTX.

The results of the logistic regression analysis provide new insights into modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for CIN. While in the univariate analysis and consistent with previous studies, younger age2,3,8,47 and decreased alcohol intake2 were associated with CIN, only education and having child care responsibilities remained significant in the multivariate model. Given that one study found no association with education and CIN,5 additional research is needed to confirm our association. Our study is the first to report that patients who had child care responsibilities were 1.4 times more likely to be in the CIN group. Clinicians can assess whether patients need assistance with child care and make appropriate referrals.

While not evaluated in previous studies, in the univariate analysis, both a higher comorbidity burden and lower functional status were associated with CIN group membership. However, in the multivariate analysis, only KPS score was retained in the final model. The differences in KPS scores between the CIN and no CIN groups represent not only statistically significant, but clinically meaningful differences (i.e., Cohen’s d = 0.60). While no studies evaluated for associations between functional status and CIN, previous studies found associations between lower KPS scores and higher depression,48 anxiety,49 fatigue,16,25 and sleep disturbance15 scores.

This study is the first to evaluate for associations between CTX cycle length and CIN group membership. Compared to patients on the 21-day cycle, patients on a 14-day cycle were more likely to report nausea in the week prior to their next does of CTX. This association can partially be explained by the increased frequency of exposure to CTX. In addition, compared to patients on a 21-day cycle, a higher percentage of patients on a 14-day cycle received highly emetogenic CTX (36.8% vs 63.2%, p<0.001, respectively). While in our univariate analysis and consistent with previous studies,2,4,9 the emetogenicity of the CTX regimen was associated with CIN group membership, only CTX cycle length and antiemetic regimen remained significant in our multivariate model. One of the most likely reason why all three characteristics did not remain significant in the multivariate analysis is that the emetogenicity of CTX regimen and antiemetic regimen were correlated (r = 0.50, p = <0.001). Another plausible explanation for this finding is that different factors may be associated with different CINV outcomes (e.g., occurrence of CIV, severity of CIN, severity of CIV).

In our multivariate model, compared to patients who received either a steroid or a serotonin receptor antagonist, patients who received the combination were more likely to belong to nausea group. While one would expect the opposite association, one possible explanation for this finding is that compared to patients who received the single agent (10.2%), 89.8% of patients who received the combination antiemetic regimen received highly emetogenic CTX (p<0.001). Another factor that could explain this finding is patients’ level of adherence with the antiemetic regimen. While not assessed in this study, future studies of CIN need to include a measure of antiemetic adherence as a covariate.

This study is the first to evaluate for associations between the severity of the most common symptoms reported by oncology patients and CIN group membership. For patients in the CIN group, all of the symptom severity scores were above the clinically meaningful cutoff scores. The findings in our regression analysis are consistent with previous reports that found associations between pre- and post-treatment CIN and higher levels of depression,5 fatigue,13 and sleep disturbance.8

While previous studies found an association between CIN and higher levels of anxiety,8,9 trait anxiety scores did not remain significant in our multivariate model. This finding may be partially explained by the inclusion of stress scores in our predictive model. Our study is the first to evaluate for associations between CIN and measures of both disease specific and general stress. While all of the subscale and total IES-R scores for patients in the CIN group were significantly higher, the total IES-R score did not exceed the clinically meaningful IES-R cutoff score of ≥33.38 In the multivariate analysis, for each 1 point increase on the intrusion subscale score, there was a 1.35 increased odds of being in the nausea group. The intrusion subscale assesses intrusive thoughts about the stress associated with cancer and its treatment (e.g., disturbing visuals and feelings). In cancer patients, fear of recurrence and progression of cancer, as well as physical symptoms (e.g., pain) are associated with increased stress.50

The PSS was used to evaluate association between non-specific stress that exceeds a person’s coping abilities39 and CIN. In the multivariate analysis, for each 1 point increase in PSS score, there was a 3% decrease in odds of belonging to nausea group. This unexpected finding warrants evaluation in future studies.

Patients who reported CIN had not only statistically significant but clinically meaningful (i.e., Cohen’s d = 0.45 to 0.81) decrements in overall QOL as well as in the physical, psychosocial, and social domains.51 In addition, these patients had clinically meaningful (i.e., Cohen’s d = 0.44 to 0.45) decrements in MCS and PCS scores.44 Patients who reported CIN had a mean MCS score of 46.55 which is below the score of 50 for the general US population. While patients in the CIN group had lower PCS scores, both groups of patients had PCS scores that were below the normative value of 50. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that reported that higher symptom occurrence rates (e.g., fatigue,52–54 pain,52–54 sleep disturbance52–54) were associated with lower PCS and MCS scores. Clinicians need to educate patients about the importance of taking antiemetic medication as prescribed to decrease CIN and associated decrements in QOL.

Several limitations warrant consideration. In a previous study the occurrence of CIN during the first cycle of CTX was a risk factor for future episodes of CIN.2 Because patients were enrolled during their second and third cycle of CTX, we could not assess the contribution of this risk factor or patients’ expectations for CIN, to CIN group membership. In addition, we did not assess patients’ level of adherence with their antiemetic regimen. While we did evaluate a large number of previously reported risk factors, because our study was not designed specifically to study CIN, a number of risk factors (e.g., morning sickness, motion sickness) were not assessed. Because of the cross-sectional nature of this study, longitudinal studies are needed to demonstrate causal relationships between our identified risk factors and changes over time in the occurrence of CIN.

Despite the limitations, our findings suggest that CIN occurs in a high percentage of oncology patients receiving CTX. The modifiable risk factors that were identified include: having childcare responsibilities; poorer functional status; and higher levels of depression, sleep disturbance, evening fatigue, perceived stress, and intrusive thoughts and feelings. Clinicians need to assess patients for these risk factors and refer them for appropriate interventions (e.g., physical therapy, mental health services). Clinicians need to educate patients about stress reduction strategies and the importance of adhering with the antiemetic regimen.

Future studies to evaluate risk factors for CIN should enroll CTX naïve patients and use instruments specifically designed to measure CIN occurrence and severity (e.g. MASCC Antiemesis Tool,55 Morrow Assessment of Nausea and Emesis Follow-Up56). The use of these measures would provide a comprehensive evaluation of anticipatory, acute, and delayed nausea, as well as the effectiveness of the antiemetic regimen. Patient adherence with the antiemetic regimen needs to be evaluated to determine its association with CIN occurrence, severity and distress. Predictors identified in previous studies as well as those identified in our study warrant confirmation. Longitudinal studies of CIN occurrence may provide insights into which characteristics identify higher risk patients. Because severe nausea can have a negative impact on patients’ nutritional status and physical functioning,11 future studies need to examine these relationships over multiple cycles of CTX. This knowledge will assist clinicians to recommend more targeted interventions to decrease the occurrence and severity of CIN.

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (NCI, CA134900). Dr. Miaskowski is an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor and is funded by a K05 award from the NCI (CA168960). Komal Singh is supported by a T32 grant (T32NR016920) from the National Institute of Nursing Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Antiemetics. 2016. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/antiemesis.pdf.

- 2.Molassiotis A, Aapro M, Dicato M, et al. Evaluation of risk factors predicting chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting: results from a European prospective observational study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:839–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hesketh P, Aapro M, Street J, Carides A. Evaluation of risk factors predictive of nausea and vomiting with current standard-of-care antiemetic treatment: analysis of two phase III trials of aprepitant in patients receiving cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2010;18:1171–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grassi L, Berardi MA, Ruffilli F, et al. Role of psychosocial variables on chemotherapy- induced nausea and vomiting and health-related quality of life among cancer patients: a European study. Psychother Psychosom 2015;84:339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pirri C, Katris P, Trotter J, et al. Risk factors at pretreatment predicting treatment-induced nausea and vomiting in Australian cancer patients: a prospective, longitudinal, observational study. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1549–1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuji Y, Baba H, Takeda K, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in 190 colorectal cancer patients: a prospective registration study by the CINV study group of Japan. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2017;18:753–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vol H, Flank J, Lavoratore SR, et al. Poor chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting control in children receiving intermediate or high dose methotrexate. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:1365–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dranitsaris G, Molassiotis A, Clemons M, et al. The development of a prediction tool to identify cancer patients at high risk for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Ann Oncol 2017;28:1260–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molassiotis A, Lee PH, Burke TA, et al. Anticipatory nausea, risk factors, and its impact on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: Results from the Pan European Emesis Registry Study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:987–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warr D, Street J, Carides A. Evaluation of risk factors predictive of nausea and vomiting with current standard-of-care antiemetic treatment: analysis of phase 3 trial of aprepitant in patients receiving adriamycin-cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:807–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrell C, Brearley SG, Pilling M, Molassiotis A. The impact of chemotherapy-related nausea on patients’ nutritional status, psychological distress and quality of life. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molassiotis A, Farrell C, Bourne K, Brearley SG, Pilling M. An exploratory study to clarify the cluster of symptoms predictive of chemotherapy-related nausea using random forest modeling. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;44:692–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zachariae R, Paulsen K, Mehlsen M, et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea, vomiting, and fatigue--the role of individual differences related to sensory perception and autonomic reactivity. Psychother Psychosom 2007;76:376–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh KP, Miaskowski C, Dhruva AA, Flowers E, Kober KM. A review of the literature on the relationships between genetic polymorphisms and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2018;121:51–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mark S, Cataldo J, Dhruva A, et al. Modifiable and non-modifiable characteristics associated with sleep disturbance in oncology outpatients during chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:2485–2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kober KM, Cooper BA, Paul SM, et al. Subgroups of chemotherapy patients with distinct morning and evening fatigue trajectories. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:1473–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bekhbat M, Neigh G. Sex differences in the neuro-immune consequences of stress: Focus on depression and anxiety. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;67:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raghavendra RM, Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR, et al. Effects of an integrated yoga programme on chemotherapy-induced nausea and emesis in breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care 2007;16:462–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klemp JR, Myers JS, Fabian CJ, et al. Cognitive functioning and quality of life following chemotherapy in pre- and peri-menopausal women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:575–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miaskowski C, Mastick J, Paul SM, et al. Impact of chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicities on adult cancer survivors’ symptom burden and quality of life. J Cancer Surviv 2018;12:234–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miaskowski C, Cooper BA, Aouizerat B, et al. The symptom phenotype of oncology outpatients remains relatively stable from prior to through 1 week following chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer Care 2017;26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bosnjak SM, Gralla RJ, Schwartzberg L. Prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea: the role of neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptor antagonists. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:1661–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chasen M, Urban L, Schnadig I, et al. Rolapitant improves quality of life of patients receiving highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nasir SS, Schwartzberg LS. Recent advances in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Oncology 2016;30:750–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright F, D’Eramo Melkus G, Hammer M, et al. Trajectories of evening fatigue in oncology outpatients receiving chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:163–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wright F, D’Eramo Melkus G, Hammer M, et al. Predictors and trajectories of morning fatigue are distinct from evening fatigue. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:176–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karnofsky D, Abelmann WH, Craver LV, Burchenal JH. The use of nitrogen mustards in the palliative treatment of carcinoma. Cancer 1948;1:634–656. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum 2003;49:156–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. In: Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kozlowski LT, Porter CQ, Orleans CT, Pope M, Heatherton T. Predicting smoking cessation with self-reported measures of nicotine dependence: FTQ, FTND, and HSI. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;34:211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer 1994;30A:1326–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee KA, Hicks G, Nino-Murcia G. Validity and reliability of a scale to assess fatigue. Psychiatry Res 1991;36:291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy BL, Schwab JJ, Morris RL, Beldia G. Assessment of state and trait anxiety in subjects with anxiety and depressive disorders. Psychiatr Q 2001;72:263–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fletcher BS, Paul SM, Dodd MJ, et al. Prevalence, severity, and impact of symptoms on female family caregivers of patients at the initiation of radiation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cimprich B, Visovatti M, Ronis DL. The Attentional Function Index--a self-report cognitive measure. Psychooncology 2011;20:194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daut RL, Cleeland CS, Flanery RC. Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to assess pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain 1983;17:197–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiss DS, Marmar CR. The Impact of Event Scale - Revised, New York: Guilford Press, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:386–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale - Revised. Behav Res Ther 2003;41:1489–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Padilla GV, Ferrell B, Grant MM, Rhiner M. Defining the content domain of quality of life for cancer patients with pain. Cancer Nurs 1990;13:108–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ware J Jr., Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roila F, Molassiotis A, Herrstedt J, et al. 2016 MASCC and ESMO guideline update for the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer patients. Ann Oncol 2016;27:v119–v133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2 nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miura S, Watanabe S, Sato K, et al. The efficacy of triplet antiemetic therapy with 0.75 mg of palonosetron for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in lung cancer patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:2575–2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albany C, Brames MJ, Fausel C, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III cross-over study evaluating the oral neurokinin-1 antagonist aprepitant in combination with a 5HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone in patients with germ cell tumors receiving 5-day cisplatin combination chemotherapy regimens: a hoosier oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3998–4003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sekine I, Segawa Y, Kubota K, Saeki T. Risk factors of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: index for personalized antiemetic prophylaxis. Cancer Sci 2013;104:711–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saad S, Dunn LB, Koetters T, et al. Cytokine gene variations associated with subsyndromal depressive symptoms in patients with breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2014;18:397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gold M, Dunn LB, Phoenix B, et al. Co-occurrence of anxiety and depressive symptoms following breast cancer surgery and its impact on quality of life. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2016;20:97–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hall DL, Lennes IT, Pirl WF, Friedman ER, Park ER. Fear of recurrence or progression as a link between somatic symptoms and perceived stress among cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:1401–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sloan JA, Frost MH, Berzon R, et al. The clinical significance of quality of life assessments in oncology: a summary for clinicians. Supportive Care in Cancer 2006;14:988–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Papachristou N, Barnaghi P, Cooper BA, et al. Congruence Between Latent Class and K- modes analyses in the identification of oncology patients with distinct symptom experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:318–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Astrup GL, Hofso K, Bjordal K, et al. Patient factors and quality of life outcomes differ among four subgroups of oncology patients based on symptom occurrence. Acta Oncol 2017;56:462–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pisu M, Azuero A, Halilova KI, et al. Most impactful factors on the health-related quality of life of a geriatric population with cancer. Cancer 2018;124:596–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Molassiotis A, Coventry P, Stricker C, et al. Validation and psychometric assessment of a short clinical scale to measure chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: the MASCC Antiemesis Tool. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;34:148–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rhodes VA MR. Nausea, vomiting, and retching: complex problems in palliative care. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:232–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]