Abstract

Background:

To compare the rate of detection of renal cell carcinoma metastases to the pancreas between arterial and portal venous phase MDCT.

Material and Methods:

A retrospective review of CTs of the abdomen yielded 6 patients with metastatic RCC to the pancreas. Five of six patients had pathologically proven clear cell RCC. Two blinded reviewers independently reported the number of pancreatic lesions seen in arterial and venous phases. Each lesion was graded as definite or possible. The number of lesions was determined by consensus review of both phases. Attenuation values were obtained for metastatic lesions and adjacent normal pancreas in both phases.

Results:

There were a total of 24 metastatic lesions to the pancreas. Reviewer 1 identified 20/24 (83.3%) lesions on the arterial phase images and 13/24 (54.2%) lesions on the venous phase. Seventeen of twenty (85.0%) arterial lesions were deemed definite and 9/13 (69.2%) venous lesions were definite. Reviewer 2 identified 19/24 (79.2%) lesions on the arterial phase and 14/24 (58.3%) on the venous phase. Seventeen of nineteen (89.5%) arterial lesions were definite and 7/14 (50%) venous lesions were definite. Mean attenuation differential between lesion and pancreas was 114 HU and 39 HU for arterial and venous phases respectively (p<.0001).

Conclusion:

Detection of RCC metastases to the pancreas at MDCT is improved using arterial phase imaging compared to portal venous phase imaging.

Keywords: Renal cell carcinoma, pancreas, metastasis, MDCT, arterial phase

Over 64,000 new cases and 13,000 deaths are expected from kidney cancer in the United States during 2012 (1). Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for the majority of these cases and 20–30% of patients will develop metastatic disease following local therapy for RCC (2). The most common sites of metastases are lung, liver, and bone but metastases are also known to occur in unusual locations such as thyroid, muscle, and subcutaneous fat (3, 4). The pancreas is an increasingly recognized site of metastatic RCC spread, and RCC has been cited as the most common primary tumor leading to an isolated pancreatic metastasis (4, 5). It is also known that recurrence of RCC in the pancreas often occurs long after nephrectomy, with multiple reports of recurrence greater than 20 years after initial treatment (6–9). These lesions are usually asymptomatic or associated with nonspecific signs and symptoms, making detection on clinical grounds difficult (10). Surgical series have demonstrated improved patient survival after resection of isolated pancreatic metastases from RCC (3, 11, 12). Therefore, detection of metastases to the pancreas is of importance during RCC surveillance. Current surveillance protocols are not uniform, however, most recommend follow up with chest x-ray and ultrasound for low risk tumors (stage T1 tumors). For intermediate risk tumors (stage T2) chest x-ray and ultrasound are suggested with some protocols suggesting abdominal CT, and for high risk tumors (stage T3 or T4), most protocols suggest routine surveillance with CT (2, 13, 14). Therefore optimizing the CT protocol for detection of RCC metastases in these high risk patients is important.

Clear cell carcinoma, the most common subtype of RCC, is known to show avid enhancement in the arterial phase at MDCT imaging and RCC metastases maintain this property (15). Specifically, RCC metastases to the pancreas demonstrate arterial enhancement and have been shown to be subjectively more conspicuous in the arterial phase when compared to more delayed phases at MDCT (4, 10, 16, 17). Ng et al. evaluated 34 RCC metastases to the pancreas and found attenuation differences of 50–100 HU in the arterial and portal venous phases, while the differences were only 5–45 HU on delayed phases (18). However, this study made the distinction between early (arterial and portal venous) versus delayed phases, not arterial versus portal venous. Jain et al. compared arterial and portal venous phase MDCT in detecting RCC metastasis in the liver, pancreas and contralateral kidney (19). Overall, more lesions were detected on the arterial phase, however, the same number of pancreatic lesions (3 out of 12) were detected on the arterial phase alone as on the portal venous phase alone. Thus, to our knowledge, it has not yet been shown that arterial phase images will actually lead to an increase in the number of pancreatic lesions detected by radiologists when compared to the portal venous phase. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine if detection of RCC metastases to the pancreas is improved using arterial phase imaging compared to the portal venous phase at MDCT.

Material and Methods

Patient Population

This Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant study was approved by the institutional review board, and a waiver of informed consent was obtained owing to its retrospective nature. A search of our single institution radiology database was performed to identify all cases of pancreatic metastases seen on CT of the abdomen from 1/1/2008 to 10/4/2012. A total of 10 patients were identified. Four were excluded because they lacked both an arterial and portal venous phase. The remaining 6 patients were included (4 men, 2 women; mean age of 68.3 years, range 58–80 years). Five patients had histologicaly proven clear cell RCC and one patient had a 7.7 cm heterogeneous arterially enhancing right renal mass on CT but no histologic data. All six patients had CT evidence of metastatic disease in other sites besides the pancreas. Three patients underwent biopsy of metastatic lesions revealing RCC, one of which was of a pancreatic lesion.

Image Acquisition

The CT examinations were performed on both Siemens (Siemens Medical System, Forchheim, Germany) and GE (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) MDCT scanners ranging from 4 to 64 detector rows. All scans were performed at 120 kVp and variable mAs. For all scanners, images were reconstructed at a thickness of 4 or 5mm and reconstruction interval of 4 or 5mm respectively, using a standard body filter on the GE scanners and B40f kernel on the Siemens scanners. All patients were injected with Omnipaque-350 (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA), injection volume ranging from 100–125 ml and injection rate ranging from 2.0–4.0ml/sec. In all patients two contrast phases were obtained through upper abdomen, one of these was an arterial phase obtained at 25–40 seconds after the start of the injection and the latter scan was obtained in the portal phase, obtained at 80–90 seconds after the start of the injection.

Image Analysis

Two board certified radiologists with specialized training in abdominal imaging (JM and RL, 25 and 14 years of experience, respectively) independently reviewed the cases. They were blinded to any clinical information and only viewed images through the pancreas. They were initially shown a single phase for each patient, arterial for half of the cases and venous for the other half. A second session was performed four weeks later in which they were shown the other phase for each patient that they did not initially review. With each session they were shown four control cases which had no pancreatic pathology, two performed in the arterial phase and two performed in the venous phase. On each study, the reviewers identified the number and location of all focal lesions in the pancreas. Each lesion was described as either possible or definite based on the reviewers’ confidence that the finding was a true metastatic lesion. The reviewers were asked to interpret the case as if the patient would be undergoing surgery to resect any metastatic lesions. For a lesion to be definite, the reviewer would recommend resection based on the provided images. For a possible lesion, the reviewer would recommend an additional study (additional CT or MRI or biopsy) to confirm the finding before recommending resection. The reference standard of actual number of pancreatic lesions was then obtained by consensus review of both arterial and venous phase images by both reviewers and a third abdominal radiologist (MC, 7 years experience). Thin slices (1 mm) were also reviewed at this session to help clarify any questionable lesions.

A single reviewer (MC) then placed regions of interest (ROI) on all lesions that were large enough to achieve an accurate attenuation measurement (7 mm or greater) on both arterial and venous phases. The ROI diameter was kept at least one-half the diameter of the lesion. The same portion of the lesion was measured and the same size ROI was used in each phase. If a lesion had central necrosis, the enhancing peripheral portion was measured. An ROI was also placed in the adjacent normal pancreas to obtain the differential enhancement (Hounsfield units (HU) lesion – HU pancreas). Care was made to avoid any blood vessels, calcifications, or focal areas of fatty lobulation when placing the ROI. ROI measurements were performed using the thin 1.0 mm slices in order to minimize volume averaging.

Statistical Analysis

To test for differences in lesion detection between the arterial and venous phases, for each radiologist and each phase, we first calculated the error in the number of lesions identified with respect to the consensus (error-from-consensus). Then we calculated the difference in this error between the arterial and venous (venous minus arterial) phase for each radiologist and then calculated the average across radiologists. This produced the average difference in the error-from-consensus between arterial and venous phase. Using this variable we conducted a one sample T test. If there is no difference in error-from-consensus between arterial and venous, then the mean of this variable should be zero. If detection is improved on the arterial phase, then we expect this variable to be positive.

To test for differences in the differential enhancement between the venous and arterial phases, we first tested for an effect due to patient using a one factor ANOVA. This was non-significant (p-value = 0.26). Therefore the lesions were treated as independent observations and a standard T test was used.

Results

There were a total of 24 metastatic lesions to the pancreas based on consensus review. Lesions were multiple in three patients and solitary in the other three. The mean size was 8.3 mm (range 2–16 mm). Reviewer 1 identified 20/24 (83.3%) lesions on the arterial phase images and 13/24 (54.2%) lesions on the venous phase images. Reviewer 2 identified 19/24 (79.2%) lesions on the arterial phase and 14/24 (58.3%) on the venous phase. Neither reviewer identified any false positive lesions on either phase. The average difference in the error-from-consensus was 1 lesion. The T test for differences in the average error-from-consensus between arterial and venous phase was significant at the 90% confidence level (p= 0.051). A post-hoc power analysis was conducted to ascertain the sample size needed to reject the null hypothesis of no difference in the average error-from-consensus between arterial and venous phase at the 0.05 level. A sample size of 13 patients is required to detect an average difference of 1 lesion between the two phases at 90% power.

For reviewer 1, 17/20 (85.0%) arterial lesions were deemed definite and 9/13 (69.2%) venous lesions were deemed definite. For reviewer 2, 17/19 (89.5%) arterial lesions were definite and 7/14 (50%) venous lesions were definite. Figs. 1 and 2 demonstrate the increased conspicuity of lesions on the arterial phase. For one patient with four lesions, reviewer 1 identified two and reviewer 2 identified four lesions on the arterial phase, but neither identified any lesions on the venous phase (Fig. 3).

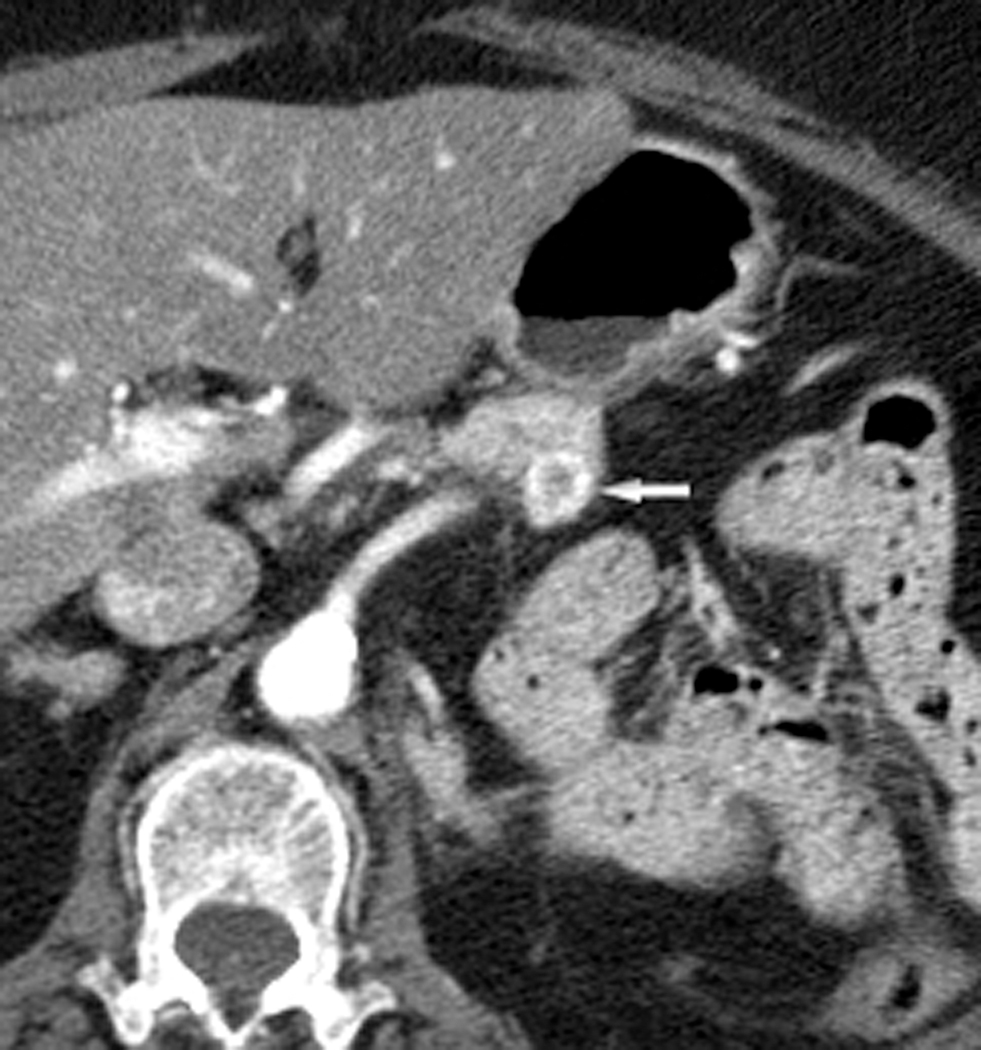

Fig. 1.

Axial CT images through the neck of the pancreas in arterial (a) and portal venous (b) phases in a 60-year-old male with RCC. A peripherally enhancing hypervascular lesion is well depicted in the arterial phase (white arrow) but more difficult to detect in the portal venous phase (arrowhead).

Fig. 2.

Axial CT images through the tail of the pancreas in arterial (a) and portal venous (b) phases in a 79-year-old female with RCC. A peripherally enhancing hypervascular lesion is well depicted in the arterial phase (white arrow) but inconspicuous in the portal venous phase (arrowhead).

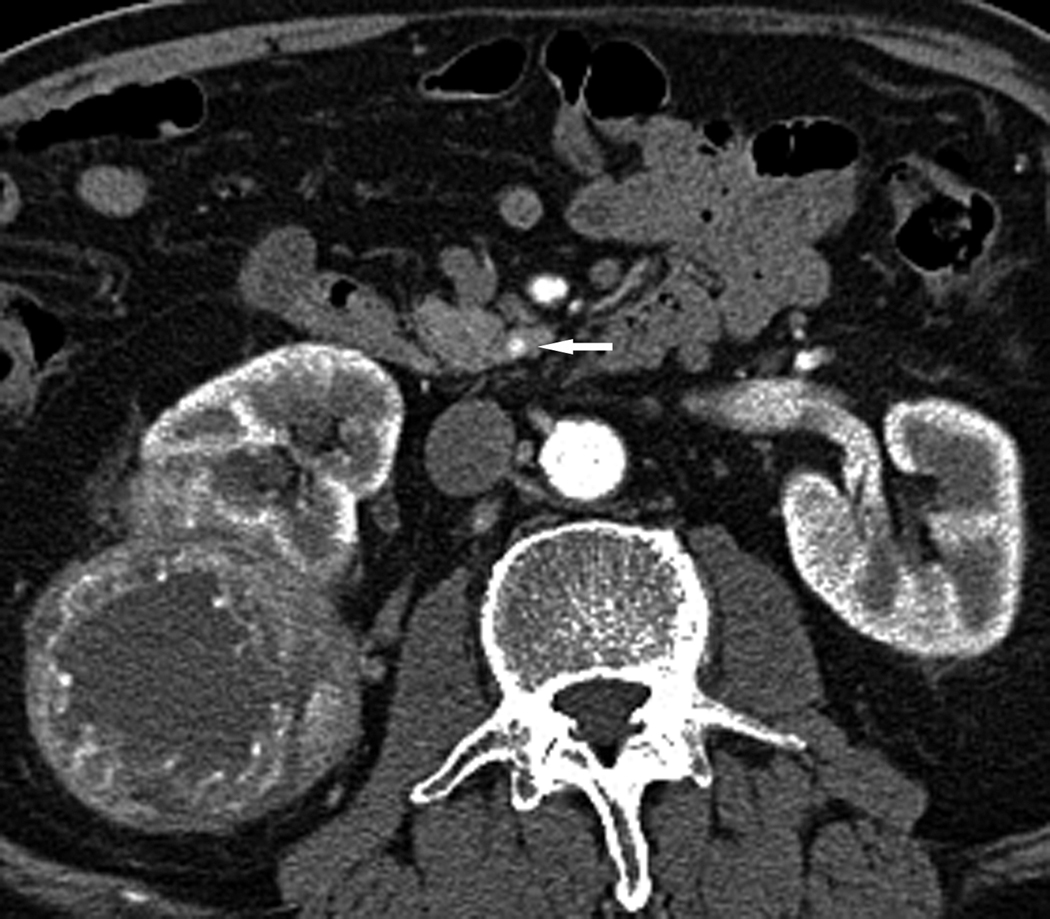

Fig. 3.

Axial CT images through the uncinate process of the pancreas in arterial (a) and portal venous (b) phases in a 72-year-old male with presumed RCC. A 3 mm hyperenhancing lesion in seen in the uncinate process of the pancreas on the arterial phase images (white arrow). This lesion is questionably detected on the portal venous phase (arrowhead). A heterogeneously enhancing mass of the right kidney is also visualized.

Attenuation values were obtained for 14 lesions. For every lesion, the absolute HU and the differential between lesion and normal pancreas was higher in the arterial phase. The mean differential attenuation between lesions and normal pancreas was 114 HU (range 53–162, SD 37) during the arterial phase, which was significantly higher than 39 HU (range 9–61, SD 17) during the venous phase (p< 0.0001).

Discussion

The results of our study show that more metastatic RCC lesions to the pancreas are detected using the arterial phase than portal venous phase. Not only did each reviewer detect more lesions in the arterial phase, the confidence level was also improved. These findings are supported by the greater attenuation differential between lesions and normal pancreas during the arterial phase compared to venous. Importantly, both reviewers failed to identify any lesions in one patient using the portal venous phase but definitively identified lesions in the arterial phase. Such a patient could therefore remain undiagnosed with metastatic disease to the pancreas if only portal venous phase imaging was performed. In addition, the increased confidence level may allow definitive treatment to begin without the need for additional studies. It should be noted that our findings only pertain to the clear cell variant of RCC as other types such as papillary RCC do not typically show hypervascularity.

Neither reviewer identified all lesions on the arterial phase. This is likely due to the fact that some of the lesions were very small (3 lesions were 3 mm or less) and were only well seen at consensus review using the thin (1 mm) slices which were not utilized during the blinded review.

It is important to note that detection of RCC metastases to other organs in the upper abdomen such as the liver was also improved with arterial phase imaging, resulting in increased lesion detection outside of the pancreas as well (19, 20). Because organs such as the liver and pancreas enhance substantially themselves, the contrast between normal parenchyma and enhancing lesions may be decreased if imaging is not performed during the appropriate phase. The phase of imaging is likely less important in the chest or pelvis, as the inherent contrast between the metastatic lesions and organs in these regions (lung, mesenteric fat) is sufficient for detection. Therefore, we suggest that the abdomen be imaged in both the arterial and portal venous phase when CT is performed for surveillance of clear cell RCC.

The main limitation of this protocol is increased radiation exposure from scanning the upper abdomen twice. This could be avoided by only performing the arterial phase for the abdomen. Our results would support this technique with regards to the pancreas as no lesions were identified in the portal venous phase that were not seen in the arterial phase. However, studies by Raptopoulos et al. and Jain et al. reported increased RCC metastasis detection (to the liver and to the liver, pancreas, and contralateral kidney respectively) using both arterial and venous phases compared to either phase alone (19, 20). However, neither study reported the type of RCC and it is possible that some of the lesions were hypovascular papillary RCC, which would be expected to be more conspicuous in the portal venous phase. The importance of identifying local recurrence after partial nephrectomy as well as contralateral kidney lesions must be stated due to the 3–5% incidence of bilateral RCC (21). Delayed phases are known to be superior in renal mass detection compared to the corticomedullary phase which supports the use of a delayed phase for RCC surveillance (22).

A potential method to reduce radiation dose would be to obtain the arterial phase at a lower peak tube voltage (i.e. 100 kVp) in thin patients. This would provide the dual benefit of a lower dose and even greater lesion to background contrast, by increasing the attenuation of the iodinated contrast enhancing the lesion (23, 24).

It should be noted that the patients undergoing CT are likely to be older and already have a history of malignancy and therefore may have a reduced life expectancy (mean age of 68.3 years in this study). As radiation-associated cancer risks are decreased in patients with a decreased life expectancy, the potential benefit of improved lesion detection outweighs this risk in our opinion (25). However, the risk of increased radiation must be balanced with the potential benefits depending on the clinical context. In high risk patients, the European Association of Urology recommends performing CT in alternate years beyond five years after surgery and the American college of Radiology suggests CT surveillance every year or every other year three years after surgery (13, 14). Neither organization recommends a specific end point of follow up. Thus the interval, duration and radiation dose of CT surveillance should be put into the appropriate clinical context with less frequent and lower dose protocols reserved for younger and lower risk patients.

Limitations to our study include lack of pathologic proof of the pancreatic lesions in all patients but one. However, all patients were known to have metastatic disease elsewhere in the setting of known RCC. This, combined with the typical imaging appearance of RCC metastases to the pancreas make it highly likely that these lesions were in fact from metastatic RCC. A second limitation is the lack of standardized MDCT imaging techniques as variable CT scanners, contrast volumes and injection rates were used. Lastly, our patient population was small, and this is likely the reason that the difference in lesion detectability between arterial and venous phases was just short of significance at the 95% confidence level. Future larger studies would be of benefit to confirm our findings.

In conclusion, detection of RCC metastases to the pancreas is improved at arterial phase imaging compared to portal venous phase imaging at MDCT. We suggest that arterial phase imaging through the abdomen be utilized when MDCT is performed for surveillance in patients with a history of RCC.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2012; 62:10–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel U, Sokhi H. Imaging in the follow-up of renal cell carcinoma. Am J Roentgenol 2012; 198:1266–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanis PJ, van der Gaag NA, Busch OR, et al. Systematic review of pancreatic surgery for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. BrJ Surg 2009; 96:579–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mecho S, Quiroga S, Cuellar H, et al. Pancreatic metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: multidetector CT findings. Abdom Imaging 2009; 34:385–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins EG, 2nd, Franceschi D, Barkin JS. Solitary metastatic tumors to the pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91:2414–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kassabian A, Stein J, Jabbour N, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the pancreas: a single-institution series and review of the literature. Urology 2000; 56:211–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wente MN, Kleeff J, Esposito I, et al. Renal cancer cell metastasis into the pancreas: a single-center experience and overview of the literature. Pancreas 2005; 30:218–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNichols DW, Segura JW, DeWeerd JH. Renal cell carcinoma: long-term survival and late recurrence. J Urol 1981; 126:17–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson LD, Heffess CS. Renal cell carcinoma to the pancreas in surgical pathology material. Cancer 2000; 89:1076–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghavamian R, Klein KA, Stephens DH, et al. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the pancreas: clinical and radiological features. Mayo Clin Proc 2000; 75:581–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sellner F, Tykalsky N, De Santis M, et al. Solitary and multiple isolated metastases of clear cell renal carcinoma to the pancreas: an indication for pancreatic surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 2006; 13:75–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strobel O, Hackert T, Hartwig W, et al. Survival data justifies resection for pancreatic metastases. Ann Surg Oncol 2009; 16:3340–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ACR appropriateness Criteria:Follow-up of renal cell carcinoma. Available at: http://www.acr.org/~/media/ACR/Documents/AppCriteria/Diagnostic/FollowUpRenalCellCarcinoma.pdf. Accessed 10/4/2012.

- 14.Imamura M, MacLennan S, Lapitan MC. Systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of surgical management for localized renal cell carcinoma. Available at: http://www.uroweb.org/gls/refs/LRCC_report_v19_20120216.pdf. Accessed 10/4/012.

- 15.Lin SP, Bierhals AJ, Lewis JS Jr. Best cases from the AFIP: Metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Radiographics 2007; 27:1801–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmowski M, Hacke N, Satzl S, et al. Metastasis to the pancreas: characterization by morphology and contrast enhancement features on CT and MRI. Pancreatology 2008; 8:199–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ascenti G, Visalli C, Genitori A, et al. Multiple hypervascular pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: dynamic MR and spiral CT in three cases. Clin Imaging 2004; 28:349–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng CS, Loyer EM, Iyer RB, et al. Metastases to the pancreas from renal cell carcinoma: findings on three-phase contrast-enhanced helical CT. Am J Roentgenol 1999; 172:1555–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain Y, Liew S, Taylor MB, et al. Is dual-phase abdominal CT necessary for the optimal detection of metastases from renal cell carcinoma? Clin Radiol 2011; 66:1055–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raptopoulos VD, Blake SP, Weisinger K, et al. Multiphase contrast-enhanced helical CT of liver metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Eur Radiol 2001; 11:2504–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klatte T, Patard JJ, Wunderlich H, et al. Metachronous bilateral renal cell carcinoma: risk assessment, prognosis and relevance of the primary-free interval. J Uology 2007; 177:2081–6; discussion 6–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuh BI, Cohan RH. Different phases of renal enhancement: Role in detecting and characterizing renal masses during helical CT. Am J Roentgenol 1999; 173:747–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marin D, Nelson RC, Barnhart H, et al. Detection of pancreatic tumors, image quality, and radiation dose during the pancreatic parenchymal phase: effect of a low-tube-voltage, high-tube-current CT technique--preliminary results. Radiology 2010; 256:450–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marin D, Nelson RC, Samei E, et al. Hypervascular liver tumors: low tube voltage, high tube current multidetector CT during late hepatic arterial phase for detection--initial clinical experience. Radiology 2009; 251:771–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brenner DJ, Shuryak I, Einstein AJ. Impact of reduced patient life expectancy on potential cancer risks from radiologic imaging. Radiology 2011; 261:193–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]