Abstract

Background

Regular engagement over time in hypertension care, or retention, is a crucial but understudied step in optimizing patient outcomes. This systematic review leverages a hermeneutic methodology to identify, evaluate, and quantify the effects of interventions and contextual factors for improving retention for patients with hypertension.

Methods

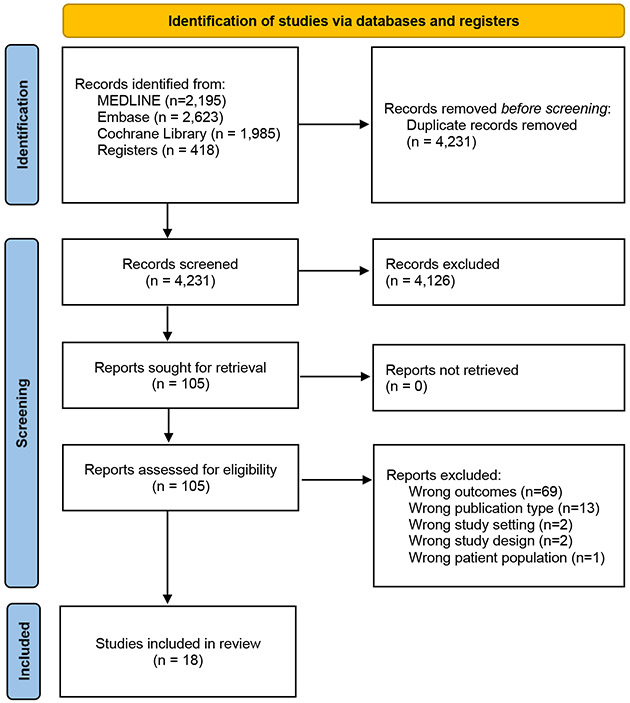

We searched for articles that were published between 2000-2022 from multiple electronic databases, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, clinicaltrials.gov, and WHO International Trials Registry. We followed the latest version of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guideline to report the findings for this review. We also synthesized the findings using a hermeneutic methodology for systematic reviews, which used an iterative process to review, integrate, analyze, and interpret evidence.

Results

From 4,686 screened titles and abstracts, 18 unique studies from 9 countries were identified, including 10 (56%) randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 3 (17%) cluster RCTs, and 5 (28%) non-RCT studies. The number of participants ranged from 76 to 1,562. The overall mean age range was 41-67 years, and the proportion of female participants ranged from 0% to 100%. Most (n=17, 94%) studies used non-physician personnel to implement the proposed interventions. Fourteen studies (78%) implemented multilevel combinations of interventions. Education and training, team-based care, consultation, and Short Message Service reminders were the most common interventions tested.

Conclusions

This review presents the most comprehensive findings on retention in hypertension care to date and fills the gaps in the literature, including the effectiveness of interventions, their components, and contextual factors. Adaptation of and implementing HIV care models, such differentiated service delivery, may be more effective and merit further study.

Registration

CRD42021291368

Keywords: hypertension, retention, primary care, implementation science, hermeneutic systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Elevated blood pressure, or hypertension, is a leading modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) globally[1, 2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) HEARTS (Healthy-lifestyle counselling; Evidence-based treatment protocols; Access to essential medicines and technology; Risk-based CVD management; Team-based care; Systems for monitoring) technical package recommends integrating hypertension care into primary care to improve the reach, effectiveness, implementation, and maintenance of hypertension care[3]. Research is needed to determine not only how best the HEARTS package can be used in the diagnosis, treatment, and control of hypertension in routine primary care but also how to retain patients in longitudinal care.

Retention in hypertension care is defined as patients’ regular engagement over time with medical care at a health care facility after initial entry into the system. High retention is essential for the long-term management of hypertension and other non-communicable diseases (NCDs), as well as clinical programmatic maintenance, but 1-year retention rates are <50% in many resource-limited settings[4].

Addressing provider-patient communication, financial barriers, and limited knowledge about hypertension treatment and control seem to be modestly effective in improving retention[5, 6]. Trials testing the effectiveness of behavioral communication tools, mobile health messaging, and linkage to peer and microfinance groups have had mixed results[7-10]. Despite the importance of retention in the hypertension care cascade globally, there has not been a previous synthesis of what interventions are most effective in improving retention and in what contexts. Thus, this systematic review leverages a hermeneutic methodology to identify, evaluate, and quantify the effects of interventions and contextual factors for improving retention comprehensively for patients with hypertension in primary care settings. We will utilize implementation science frameworks to map the context and intervention components stratified by target population, setting, outcomes, and overall results.

METHODS

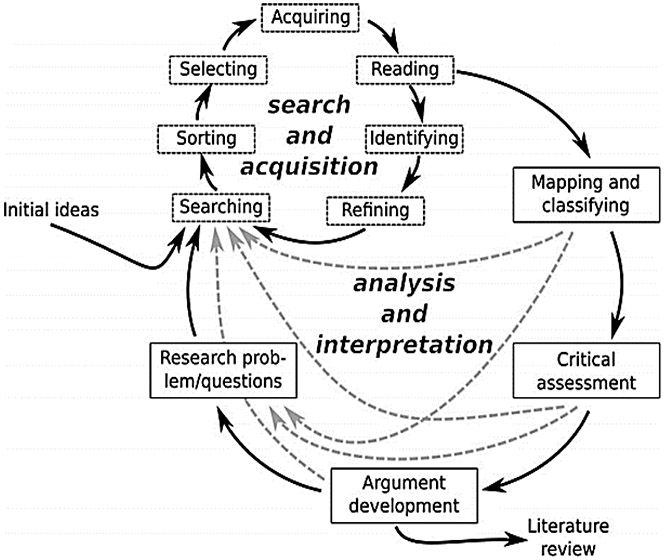

We followed a hermeneutic approach (Figure 1) given the iterative nature of reviewing, mapping, and synthesizing data to develop arguments around a complex topic like retention[11]. We chose to use the hermeneutic approach for two reasons: (1) the amount of eligible studies seemed to be, a priori, relatively small, and thus we decided to conduct two phases of review, including one phase of conventional systematic review and one phase of hermeneutic review to synthesize additional primary care-based interventions for improving retention in other conditions; and (2) unlike a conventional systematic review approach, the hermeneutic approach uses an iterative process to review, integrate, analyze, and interpret evidence to develop a better understanding of a particular field[11]. The review, coding, analysis, and reporting of findings were organized to evaluate effects and contextual factors associated with relevant interventions based on our team’s prior experience and adherence to systematic review performance (AMSTAR-2)[12] and reporting (PRISMA)[13].

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram for the systematic review.

Eligibility criteria

We used the following PICOTS (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Time course, and Study design) elements to build eligibility criteria for the included studies:

Population:

Studies that included adults (age ≥18 years) with hypertension and patients who were selected or enrolled in the study from primary care clinics.

Intervention:

Studies that evaluated the effect of any intervention, including system- and provider-level implementation strategies and patient behaviors, aimed at improving the retention of patients with hypertension in primary care settings. Trials that included a combination of interventions to improve retention were also included. We included trials that tested interventions targeting:

Health Systems: case management/patient registration system; electronic patient registry; availability of fixed-dose combination; health insurance policy; strengthening infrastructure, health system financing, and other incentives (e.g., gifts or monetary incentives); regulation and governance; and other management techniques.

Clinicians: education; reminders; group problem solving; healthcare provider-directed financial incentives; supervision (e.g., improving routine supervision, benchmarking, or audit and feedback); high-intensity or low-intensity training; printed information for healthcare providers; information and communication technology for healthcare providers (e.g., telephone or text message follow-up or intensive tracing efforts to locate study participants).

Patients: patient education; availability of transportation to primary care facilities; insurance and employment improvement; medication adherence; promotion of self-management (e.g., behavioral and motivational interventions); and reminder systems.

Comparator:

We considered any standard or usual hypertension care as the control group.

Outcomes:

The primary effectiveness outcome was:

Difference in retention rates between intervention and control groups among patients with hypertension in primary care settings.

Secondary effectiveness outcomes were:

Medication adherence, using a validated instrument or defined by the study investigators.

Cost of intervention.

Cost-effectiveness.

Duration of retention:

One challenge to administrators, researchers, and clinicians who want to systematically evaluate hypertension clinical engagement is deciding on how to measure retention in care. Measuring retention is complex because it includes multiple clinic visits scheduled at varying intervals and occurring longitudinally[14, 15]. We report retention rates in four categories based on typical follow-up time periods: 1-3 months, 3-6 months, 6-12 months, and more than 12 months.

Study design:

The inclusion/exclusion criteria were illustrated in Table 1. The field of health information and communication technology have witnessed significant advancements and changes over time. By including articles from the last two decades, we aimed to ensure that our review reflects the most current and relevant research findings, methodologies, and practices. Including older articles might introduce outdated practices, theories, or technologies that are no longer representative of the current state of retention in hypertension care. Focusing on recent publications helps maintain the accuracy and applicability of our findings.

Table 1.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for article selection.

| Article type | |

|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|

|

Contextual factors

Contextual factors that influence the primary and secondary outcomes, as defined by the study investigators and by the systematic review team, were captured and mapped onto the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) framework[16].

Outer setting: comparison between high-income countries versus low- or middle-income countries and World Health Organization-defined geographic region.

Inner setting: primary care study characteristics (e.g., setting ownership).

Intervention characteristics: technology-based, community-based, or personnel-based interventions.

Characteristics of individuals: patients with hypertension (age, gender, education, comorbidities, etc.), health care worker type.

Process of implementation: interventions and how they were implemented, duration of intervention, follow-up approach.

Information sources

Following prospective protocol registration (CRD42021291368)[17], we searched for articles that were published between 2000-2022 from multiple electronic databases including MEDLINE (National Library of Medicine, National Center for Biotechnology Information), EMBASE (Elsevier), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (EBSCOhost), clinicaltrials.gov (National Institutes of Health), and WHO International Trials Registry (World Health Organization). Given the recent advancement in information and communication technology that can influence retention, we restricted the study time period to last two decades, so as to make the contextualization/adaptation of interventions to current primary health care settings more relevant and applicable.[18, 19] Additionally, we searched the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and included articles and identified other relevant articles through contact with experts in cardiovascular medicine, investigators who have done relevant studies, and professionals who have investigated retention in other health condition domains (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]).

Search strategy

We worked with two medical research librarians (LO, EW) to develop a comprehensive search strategy. The search strategy incorporated keywords and controlled vocabulary terms for hypertension, primary care, and retention. We developed the search strategy in MEDLINE and adapted it to the pre-selected databases. We performed each search without language restrictions. The search strategies are presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Study selection

We performed a pilot screen to calibrate reviewers and improve the reliability of screening. Reviewers (JY, OAS) applied the eligibility criteria to independently screen a sample of 100 citations using Covidence, an online systematic review software[20]. We resolved discrepancies through discussion, including with a third author (MDH). We repeated this exercise in subsequent pilot screenings until we reached 90% agreement. These same two authors then utilized Covidence to independently screen the titles and abstracts of the remaining potentially relevant articles in duplicate (level 1 screening). Two reviewers (JY, OAS) then independently reviewed full-text articles to assess eligibility in duplicate (level 2 screening). Disagreements were resolved through discussion, including with a third author (MDH) to achieve consensus at each level of screening.

Data collection process

We developed a standardized data abstraction form, which was pilot tested with 2 included studies to ensure agreement between data extractors. Data from included articles were extracted and mapped independently by two reviewers (JY, OAS) to key domains such as geographic region, income, intervention timing and frequency, comparators, start time, number of participants, study objectives, primary outcome, and methods of follow-up will be collected. Details of retention interventions included type, timing, and frequency.

Because some interventions to improve retention were multifaceted with multiple targets, we extracted information about each component from all trials, explored its elements, and determined the overall impact through a narrative synthesis. We used a hermeneutic review approach that consists of two interlinked cycles: (1) accessing and interpreting the articles, including mapping the interventions onto two existing health system and implementation science frameworks, including WHO building blocks[21] and Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) compilation [22], and (2) developing arguments. To ensure the synthesis was rigorous and transparent, review authors met to discuss and categorized different retention interventions from the included studies. As sources accumulated, it became necessary to interpret, clarify, and understand emerging ideas and perspectives and to reject less relevant sources through progressive focusing, which led us to differentiated service delivery models as the most promising area for further inquiry[11]. We searched for systematic reviews that synthesized interventions that used differentiated service delivery models to improve retention in hypertension and other health conditions. This additional search is consistent with the hermeneutic approach that includes an iterative process of review, mapping, and synthesis. The independent results were discussed, and discrepancies were reconciled before providing the final list of major retention categories.

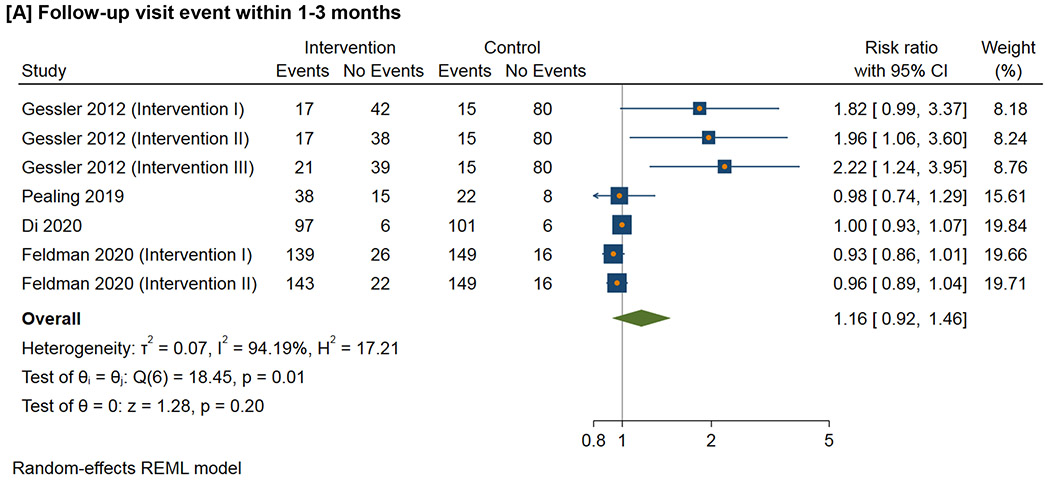

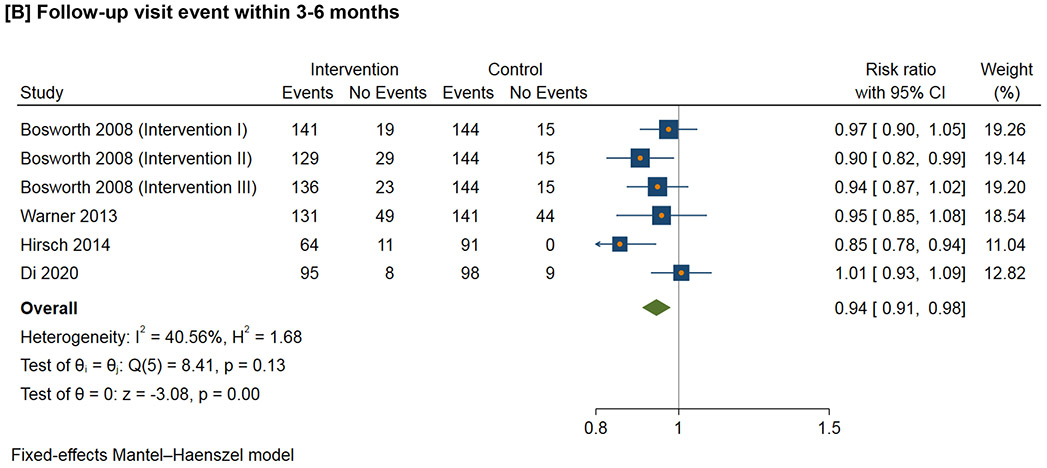

Statistical analysis

Due to the heterogeneous characteristics of the time duration of retention in the selected studies, we did not perform meta-analysis for retention rate. We defined that having a follow-up visit within the given time duration as the “event” and performed meta-analysis for all the RCTs. We reported pooled dichotomous data as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using a fixed-effect meta-analysis when statistical heterogeneity was low to moderate (I2 <50%). In the event of substantial clinical, methodological, or statistical heterogeneity (I2 ≥50%), we performed a random-effect meta-analysis with cautious interpretation of the pooled effect estimate. We reported baseline SBP and DBP to show the characterisctics of the particpants, which were continuous data as mean difference with 95% CIs. Because this study did not aim to test the effectiveness of a specified intervention but rather explore different intervetions, we did not perform meta-analysis for the change of SBP and DBP and other clinical or implementation outcomes. We identified heterogeneity through visual inspection of forest plots and by using a standard Chi2 test with a significance level of α = 0.1. In view of the low power of this test, we also considered the I2 statistic to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta-analysis.

Quality assessment of included studies

The Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool[23] was used to assess the risk of bias for RCTs. The ROBINS-I (“Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies - of Interventions”) tool [24] was used to assess the risk of bias in estimates of the comparative effectiveness (i.e., harm or benefit) of interventions from non-randomized studies.

Hermeneutic approach

We followed a hermeneutic approach (Figure 2)[11], which emphasizes the theory of interpretation that deals with the questions and meanings of texts, given the iterative nature of reviewing, mapping, and synthesizing data to develop arguments around a complex topic like retention[11]. First, we developed the key question, theories, search methods, analysis plans, and scholarly arguments relevant to our research questions (i.e., retention in hypertension care). Next, we studied the results of the initial, systematic review phase. Based on limited findings from the selected studies for the conventional systematic review, emergent themes and discussion related to small effect sizes and low probability of scalability observed with interventions to improve retention for patients with hypertension, we sought more sources and information about retention in other health conditions in the second phase of the review. We searched for reviews that synthesized primary care-based strategies for improving retention in other conditions using a similar search strategy and found that HIV was the dominant condition that focused on retention, especially in decentralized care models for people living with HIV, also known as differentiated service delivery models[25]. We sought these models also based on the successful history of decentralization of care for HIV[26], which has preceded widespread decentralization for management of hypertension. We thus adapted differentiated service delivery models for hypertension care with a focus on improving retention.

Figure 2.

The hermeneutic framework for the systematic review process[11].

Differentiated service delivery models

Differentiated service delivery models have been scaled up for antiretroviral treatment (ART) for HIV care, which typically reduces clinic visits, moves services out of the clinic, or both; these models may also alter the provider cadre and package of services provided[27]. Differentiated service delivery models have multiple aims: (1) making treatment more patient-centered, including but not limited to reducing the number of clinic visits, (2) reducing costs to both the health care system and patients, and (3) sustaining or improving clinical treatment outcomes[28]. Differentiated service delivery models are intended as an adjunct or alternative to traditional or conventional care. Although differentiated service delivery models in HIV care are increasingly utilized, there is limited experience in their application for hypertension care.

RESULTS

After de-duplication, 4,686 titles, abstracts, and other records were identified and screened, which led to assessment of 105 full-text papers, reports, and manuscripts for eligibility. Of these potentially eligible studies, 18 studies were included in the initial stage of this review (Figure 1); the reasons for exclusion included wrong outcomes, wrong publication types, wrong study settings, wrong patient population, and wrong study design than in the eligibility criteria. The results of the risk of bias summary and risk of bias graph are shown in Supplemental Figure 2 (RCTs) and Supplemental Figure 3 (non-RCTs), respectively.

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the included studies. Eighteen unique studies (n=9,656 participants, range: 76 to 1,562) were identified, including 10 (56%) randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 3 (17%) cluster RCTs, and 5 (28%) non-RCT studies. The 18 studies were conducted in 9 countries with diverse patient populations, among which 7 (39%) studies were in the United States, 3 (17%) studies were in Cameroon, 2 (11%) studies were in Australia, and the others including China, Ghana, Iraq, Kenya, Singapore, and the United Kingdom. In total, 11 (61%) studies were conducted in high-income countries, and 7 (39%) were conducted in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) based on the World Bank’s classification[29]. Overall mean age range was 41 to 67 years, and the proportion of females ranged from 0% to 100%.

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Study design | Country | Region (sites) | Population Mean age, % of female |

Setting | No. of patients (clinics) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adler 2019 [37] | Uncontrolled before–after study | Ghana | Lower Manya Krobo, Eastern Region (1) | 58, 69% | A periurban community | 1,339 patients (NR) |

| Aldabbagh 2020 [31] | Uncontrolled before–after study | Iraq | Al-Najaf city (1) | NR, 66% | 27 primary care centers | 76 patients (27 clinics) |

| Bosworth 2008 [38] | RCT | United States | Durham city, North Carolina (1) | 61, 66% | 2 primary care clinics | 1,424 patients (2 clinics) |

| Dennison 2007 [46] | RCT | United States | Inner city Baltimore, Maryland (1) | 41, NR | A community | 309 patients (NR) |

| Di 2020 [32] | Parallel-group RCT | China | Shenzhen city (1) | 54.3, 51% | 2 primary care centers | 210 patients (2 clinics) |

| Feldman 2020 [33] | RCT | United States | New York city, New York (1) | 66.6, 57% | A large urban home health organization | 495 patients (1 clinic) |

| Gessler 2012 [30] | Quasi RCT | Cameroon | Health districts of Mfou, Mbankomo, Soa and Obala (3) | 62, 43% | Primary care centers | 269 patients (NR) |

| Gums 2015 [41] | Cluster RCT | United States | 15 states in the U.S. (15) | 59, 60% | 32 primary care offices | 625 patients (32 clinics) |

| Hirsch 2014 [39] | RCT | United States | San Diego city, California (1) | Intervention: 65.4, 47% Control: 69.6, 68% |

A university-based primary care clinic. | 166 patients (1 clinic) |

| Huebschmann 2012 [47] | Pragmatic RCT | United States | Aurora city, Colorado (1) | Intervention: NR, 57% Control: NR, 52% |

2 general internal medicine clinics, 4 family medicine clinics, and 1 women’s health clinic | 591 patients (7 clinics) |

| Labhardt 2010 [44] | Uncontrolled before–after study | Cameroon | 8 resource-limited Cameroonian districts with mostly public facilities (8) | 60, 69% | 75 NPC-facilities | 796 patients (75 clinics) |

| Labhardt 2011 [45] | Cluster RCT | Cameroon | 5 predominantly rural health districts in Central Cameroon (5) | Incentive group: 58.7, 65% Letter reminder group: 60.8, 64% Control: 59.9, 64% |

33 primary care centers | 221 patients (33 clinics) |

| Oti 2016 [42] | Quasi-experimental study | Kenya | Korogocho slum (1) | Intervention: NR, 50% Control: NR, 22% |

A private nonprofit facility and a community-owned facility in a slum | 660 patients (2 clinics) |

| Pealing 2019 [34] | Unmasked RCT | United Kingdom | England (1) | NR, 100% | 4 National Health Service (NHS) maternity units | 158 patients (4 clinics) |

| Stewart 2014, A [43] | Prospective, non-blinded, cluster-RCT | Australia | Metropolitan, regional, and remote areas in 3 states of Australian (Victoria, Western Australia and Tasmania). (3) | Intervention: 66.8, 52.2% Control: 66.6, 45% |

55 community pharmacies | 457 patients (55 clinics) |

| Stewart 2014, B [35] | RCT | Australia | Australian-wide (1) | Intervention: 59, 38% Control: 59, 38% |

119 primary care clinics | 1,562 patients (119 clinics) |

| Teo 2021 [40] | Quasi-experimental study | Singapore | Singapore-wide (1) | Intervention: 56.3, 43% Control: 59.9, 40% |

A polyclinic (Asian primary care setting) | 242 patients (1 clinic) |

| Warner 2013 [36] | Randomized, controlled, intervention trial | United States | Boston neighborhoods of Roxbury and Dorchester, Massachusetts (2) | Intervention: 54.6, 71% Control: 54.7, 66% | 3 community health clinics. | 365 patients (3 clinics) |

NR=Not reported, NPC= Non-physician clinician, RCT=randomized controlled trial

Table 3 demonstrates the characteristics of retention rates in the included studies. We categorized the time course for retention into four groups based on common clinical follow-up periods: (1) 1-3 months, (2) 3-6 months, (3) 6-12 months, and (4) more than 12 months. Retention rates varied widely: 6 studies reported retention rates in 30 days-3 months[30-35], 7 studies reported retention rates in 3-6 months[32, 35-40], 10 studies reported retention rates in 6-12 months[33, 36-39, 41-45], and 4 studies reported retention rates that were more than 12 months[36, 38, 46, 47]. The 1-3 month effect sizes ranged from −6.1% to 19%, 3-6 month effect sizes ranged from −15% to 0%, 6-12 month effect sizes ranged from −31% to 36%, and effect sizes for over 12 months ranged from −15% to 29%. In 5 RCTs (39%) among the 13 RCT studies, the intervention groups had significantly higher retention rates than the control groups, which ranged from 35%-93%.

Table 3.

Characteristics of retention rates in the included studies.

| Study | Retention period definition | Retention rates (30 days-3 months) |

Retention rates (3-6 months) |

Retention rates (6-12 months) |

Retention rates (>12 months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retention as primary outcome | |||||

| Gessler 2012 | Any visit by:

|

Usual care: 15/95 (16%) Intervention group I: 17/59 (29%) Intervention group II: 17/55 (31%) Intervention group III: 21/60 (35%) |

|||

| Labhardt 2010 | Had recorded consultation by:

|

63/349 (18.1%) | |||

| Labhardt 2011 | Had ≥ 12 follow-up visits within 12 months and with the last recorded consultation at least 1 year after the start of the treatment. | Usual care: 26/89 (29%) Incentive group: 33/55 (60%) Letter reminder group: 50/77 (65%) |

|||

| Pealing 2019 | Any visit by: 6 weeks | Usual care: 22/30 (73%) Intervention: 38/53 (72%) |

|||

| Warner 2013 | Any visit by:

|

Control: 141/185 (76.2%) Intervention: 131/180 (72.8%) |

Control: 139/185 (75.1%) Intervention: 114/180 (63.3%) |

Control: 18 months: 133/185 (71.9%) 24 months: 166/185 (89.7%) Intervention: 18 months: 112/180 (62.2%) 24 months: 148/180 (82.2%) |

|

| Retention as exploratory outcome | |||||

| Adler 2019 | Any visit by:

|

552/1339 (41%) | 338/1339 (25%) | ||

| Aldabbagh 2020 | Any visit by:

|

30 days: 39/76 (51.3%) 90 days: 20/76 (26.3%) |

|||

| Bosworth 2008 | Any visit by:

|

Usual care: 144/159 (94%) Behavioral Intervention: 141/160 (88%) Home BP Monitor: 129/158 (82%) Combined (Home BP & Behavioral) Intervention: 136/159 (86%) |

Usual care: 131/159 (82%) Behavioral Intervention: 135/160 (84%) Home BP Monitor: 118/158 (75%) Combined (Home BP & Behavioral) Intervention: 122/159 (77%) |

18 Months: Usual care: 129/159 (81%) Behavioral Intervention: 122/160 (76%) Home BP Monitor: 112/158 (71%) Combined (Home BP & Behavioral) Intervention: 105/159 (66%) 24 Months: Usual care: 128/159 (81%) Behavioral Intervention: 124/160 (78%) Home BP Monitor: 113/158 (72%) Combined (Home BP & Behavioral) Intervention: 110/159 (69%) |

|

| Dennison 2007 | Any visit by:

|

Less intensive intervention: Year 1: 122/152 (80%) Year 2: 118/152 (78%) Year 3: 106/152 (70%) Year 4: 99/152 (65%) Year 5: 89/152 (59%) More intensive intervention: Year 1: 142/157 (90%) Year 2: 134/157 (85%) Year 3: 125/157 (95%) Year 4: 118/157 (94%) Year 5: 111/157 (71%) |

|||

| Di 2020 | Any visit by:

|

2 weeks: Usual care: 105/107 (98%) Intervention: 100/103 (97%) 3 months: Usual care: 101/107 (94%) Intervention: 97/103 (94%) |

Usual care: 98/107 (92%) Intervention: 95/103 (92%) |

||

| Feldman 2020 | Any visit by:

|

Usual care: 149/165 (90.3%) Usual care +NP: 139/165 (84.2%) Usual care +NP+HC: 143/165 (86.7%) |

Usual care: 141/165 (85.5%) Usual care +NP: 128/165 (77.6%) Usual care +NP+HC: 132/165 (80.0%) |

||

| Gums 2015 | Any visit by:

|

Usual care: 170/194 (87.6%) Intervention: 319/345 (92.5%) |

|||

| Hirsch 2014 | Any visit by:

|

Usual care: 91/91 (100%) Intervention: 64/75 (85%) |

Usual care: 91/91 (100%) Intervention: 52/75 (69%) |

||

| Huebschmann 2012 | Any visit by: 18 months |

Usual care: 181/591 (30.6%) Intervention: 219/591 (37.1%) |

|||

| Oti 2016 | Had ≥ 6 visits by: 12 months | 178/660 (27%) | |||

| Stewart 2014, A | Any visit by: 6 months |

Usual care: 176/216 (81.5%) Intervention:178/241 (73.9%) |

|||

| Stewart 2014, B | Any visit by:

|

Day 42 Intervention: 812/945 (86%) Day 70 Intervention: 678/872 (78%) |

Day 98 Intervention: 595/831 (72%) Day 126 Intervention: 586/829 (71%) Day 182 Intervention: 502/857 (59%) |

||

| Teo 2021 | Any visit by: 6 months |

Usual care:115/121 (95%) Intervention: 103/121 (85%) |

|||

NR= Nurse practitioner, NP = Nurse practitioner: HC=home care

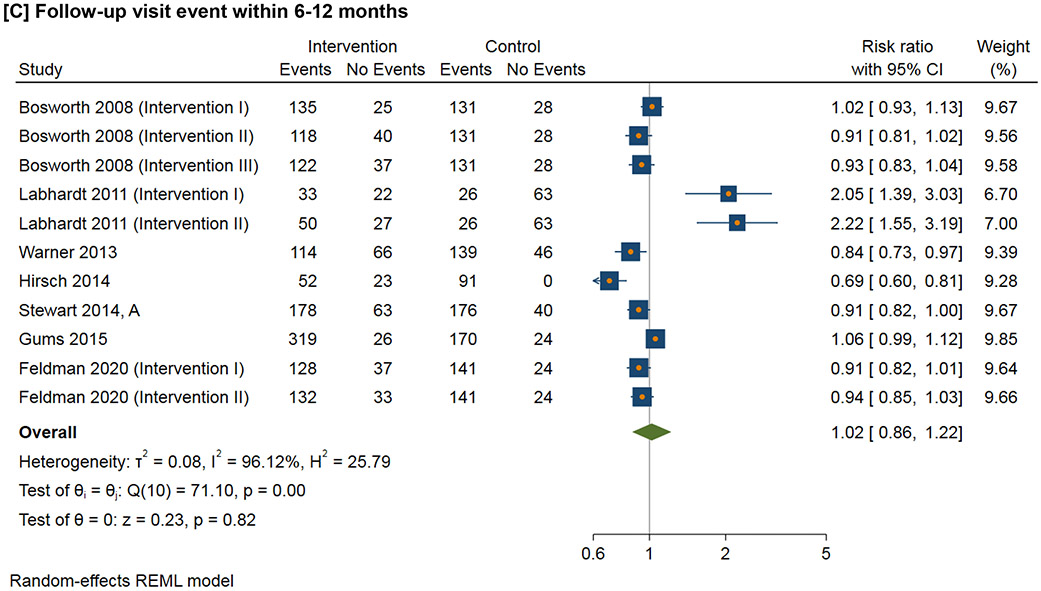

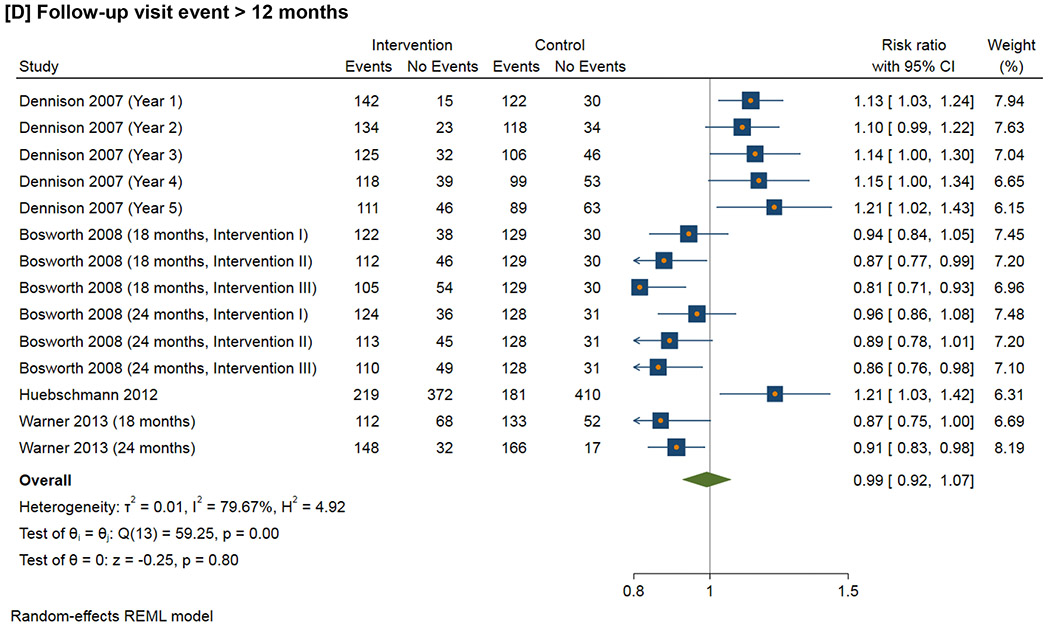

Figure 3 shows the meta-analysis of the follow-up visit event within the defined time duration. For 1-3 month follow-up visit, the RR ranges from 0.98 to 2.22 (I2=94.2%); for 3-6 month follow-up visit, the RR ranges from 0.85 to 1.01 (I2=40.6%); for 6-12 month follow-up visit, the RR ranges from 0.69 to 2.22 (I2=96.1%); for follow-up visit more than 12 months, the RR ranges from 0.81 to 1.21 (I2=79.7%).

Figure 3.

Effect of interventions on follow-up visit event within the defined time duration

Supplemental Figure 1 shows the baseline characteristics of (A) systolic blood pressure and (B) diastolic blood pressure. The mean differenecs of SBP ranges from - 2.9 to 10.0 mm Hg (I2= 78.1), and mean differenecs of DBP ranges from −1.5 to 2.0 mm Hg (I2= 0).

Table 4 presents the interventions for improving retention in hypertension care mapped onto the WHO building blocks [21] and Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) compilation[22]. The specific interventions defined by the study authors are presented in Supplemental Table 2. Fourteen studies (78%) implemented multilevel interventions. Education and training, team-based care, consultation, and Short Message Service (SMS) reminder were the most common interventions for improving retention in hypertension care. Mapped to the WHO building blocks, service delivery, health information systems, and health workforce were the most common intervention domains. Mapped to the ERIC compilation of implementation strategies, providing interactive assistance, training and educating stakeholders, and supporting clinicians were the most common strategies tested.

Table 4.

Interventions for improving retention in hypertension care derived from this review with subsequent mapping to the WHO building blocks and ERIC frameworks.

| Study | Interventions | WHO building blocks | ERIC strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adler 2019 |

|

|

|

| Aldabbagh 2020 |

|

|

|

| Bosworth 2008 |

|

|

|

| Dennison 2007 |

|

|

|

| Di 2020 |

|

|

|

| Feldman 2020 |

|

|

|

| Gessler 2012 |

|

|

|

| Gums 2015 |

|

|

|

| Hirsch 2014 |

|

|

|

| Huebschmann 2012 |

|

|

|

| Labhardt 2010 |

|

|

|

| Labhardt 2011 |

|

|

|

| Oti 2016 |

|

|

|

| Pealing 2019 |

|

|

|

| Stewart 2014, A |

|

|

|

| Stewart 2014, B |

|

|

|

| Teo 2021 |

|

|

|

| Warner 2013 |

|

|

|

ERIC=Expert Recommendations in Implementing Change, WHO=World Health Organization

Table 5 presents the contextual factors for improving retention in hypertension care among the selected studies. Four of the 7 studies that were conducted in low- or middle-income countries were supported by agencies or organizations outside of the home country. Most (n=17, 94%) studies used non-physician personnel (e.g., nurses, pharmacists, community health workers, etc.) to implement the tested interventions. Six (33%) studies were led by or included nurses in the intervention.

Table 5.

Contextual factors for improving retention in hypertension care derived from this review.

| Study | Outer setting | Inner setting | Intervention characteristics |

Characteristics of individuals |

Process of implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adler 2019 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Aldabbagh 2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Bosworth 2008 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Dennison 2007 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Di 2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Feldman 2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gessler 2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Gums 2015 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Hirsch 2014 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Huebschmann 2012 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Labhardt 2010 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Labhardt 2011 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Oti 2016 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Pealing 2019 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Stewart 2014, A |

|

|

|

|

|

| Stewart 2014, B |

|

|

|

|

|

| Teo 2021 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Warner 2013 |

|

|

|

|

|

NR= Not reported; LMIC= low- and middle-income country; HIC= high-income country; EBI= evidence-based, individualized

Table 6 demonstrates common differentiated service delivery models for HIV care based on results from the second round of review; each taxonomy provides different information. In HIV care, differentiated service delivery models offers clinical care at established health care facilities, though each health care system may have organization models that also deliver care outside the facility. We adapted these strategies for implementation in hypertension care.

Table 6.

Characteristics of the common differentiated service delivery models for HIV with adaptations for implementation in hypertension care to improve retention.

| Strategies | Care model for HIV (syntheses from literature) | Adapted care model for hypertension |

|---|---|---|

| External pickup points | Models that deliver antiretroviral medications to pick-up points outside clinic facilities, such as lockers, community pharmacies, decentralized pickup points, etc. | Strategies that deliver anti-hypertension medications to pick-up points outside secondary or higher-level facilities, such as primary care centers, community pharmacies, and other decentralized pickup points. |

| Adherence clubs | Group models that are led by a health care worker (professional or lay). | Group models that are led by a non-physician worker. |

| Community outreach | A variety of models that bring both clinical care and medications into the community, such as nurse-led outreach. | Strategies that bring both clinical care and medications into the community, such as non-physician worker-led outreach. |

| Unstable patient models | Models for patients who do not meet definitions of clinical stability, such as high viral load clinics and advanced disease clinics. | Strategies for patients who do not meet definitions of clinical stability, such as persistently high blood pressure and other advanced cardiac diseases. |

| Youth models | Models specifically for youth/teens/adolescents. | Not applicable* |

| Fast track services | Any models that create a separate queue, kiosk, or procedure at a facility to speed up service delivery for stable patients. | Strategies that create a separate queue, kiosk, or procedure at a facility to speed up service delivery for stable patients. |

| Community adherence groups | Models in which a patient picks up medications for other group members (typically community adherence group). | Strategies that a patient picks up medications for other group members (e.g., community adherence group, patient support group, or community health committee). |

| Multi-month dispensing | Models in which the primary goal is to dispense medications for a longer duration than is done under standard care (usually 6 months). | Strategies that the primary goal is to dispense anti-hypertension medications for a longer duration than is done under standard care (usually 3-6 months). |

| Extra clinic hours | Models that add additional hours to a facility's operations to facilitate access, such as on evenings or weekends. | Strategies that add additional hours to a facility's operations to facilitate access, such as on evenings or weekends. |

| Family models | Models designed to serve multiple and/or specific members of a family at once (e.g., pediatric clinic or family clinic). | Strategies designed to serve multiple and/or specific members of a family at once (e.g., home-based primary care). |

| Home delivery | Models that deliver antiretroviral medications to patients' homes (e.g., by a community health worker or a bicycle courier). | Strategies that deliver anti-hypertension medications to patients' homes (e.g., by a non-physician worker). |

| Key population models | Models for a key population such as men who have sex with men or female sex workers. | Models for a key population such as older or pregnant female populations. |

Management of hypertension in adults is different than management among children, adolescents, and young adults.

Supplemental Table 3 presents the common differentiated service delivery models and strategies for HIV retention. Within the 4 major categories of differentiated service delivery models, individual models varied widely, particularly in terms of specific populations targeted and locations and timing of medication pickup or delivery. Out-of-facility-based individual models (e.g.,community-based individual drug distribution and community pharmacy dispensation) and health care worker-led group models were the most commonly reported categories. However, these approaches differed sharply from one another in terms of resource needs, and thus they may have very different roles in HIV treatment programs.

DISCUSSION

Summary of Results

This hermeneutic systematic review includes 18 studies, the RCTs (72%), across a diverse range of settings. Our initial synthesis identified a limited number of interventions to improve retention with small effect sizes and low probability of scalability. After iterative review and group discussion, differentiated service delivery models to decentralize care emerged as a potentially promising approach to improve retention for patients with hypertension, which led to further assessment of differentiated service delivery in a context where it has been broadly used, namely HIV care. To the best of our knowledge, this hermeneutic systematic review is the most comprehensive review of global studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of interventions for improving retention for patients with hypertension in primary care settings.

Losing patients at the retention step of the hypertension care cascade negates the work of all other previous steps, including accurate diagnosis and treatment[48]. Low availability, difficulty obtaining, and cost of medications may deter patients from returning to clinics[49, 50]. Treatment-seeking and management behavior may be further influenced by social and religious constructs, such as gender inequity in treatment decision-making,[51] lack of awareness of causes and treatment models, and reliance upon herbal and traditional remedies[52]. Factors related to the inner setting and implementers such as quality of care (e.g., staff’s attitude, total time spent at the facility, refill frequency) and patient experience (e.g., waiting time, time at which patients could go for visits and the facility being open), as well as outter setting (e.g., geographic distance), also impact retention in care[53-56]. The selected studies generally addressed the barriers of supply of drugs, coomunication between patients and relavant stakeholders, education and consultation about hypertension management.[57]

Synthesis

The hermeneutic approach enabled us to identify potentially relevant literature and expanded the findings beyond a conventional systematic review. The more literature we acquired, the more important it became to interpret, clarify, and understand the diverse ideas, approaches, and findings in individual studies.[58] Through reading and discussion, we developed a better understanding of each selected study, embarked on a route of clarification and insight into different studies, and how they were related to retention in hypertension care. A particular type of perspective on literature related retention thus enabled us to grasp and critically assess the state of knowledge in hypertension retention and revealed important shortcomings in dealing with this underlying research problem. This also allowed the development of new linkages among concepts and theories and new syntheses by comprehensively analyzing the implications from HIV care, which accounted for most retention studies[11]. For example, adherence clubs have been implemented to improve access and adherence to blood pressure lowering medications, as well as hypertension control, learning from the experiences in HIV context[59].

Interventions to improve retention have been tested with generally modest effect sizes. For example, an included study conducted in Kenya applied integrated and co-located chronic disease care in primary care, which increased relative retention rate by 10.5% (95% CI: 10.0% - 10.9%) over 6 months compared to usual care[60]. Multilevel interventions, such as the WHO HEARTS package, which enhance access to blood pressure lowering drugs, are associated with higher retention[61]. Successful interventions need to address patients’ barriers and changing health care needs over time, and in which risk factors, diseases, and health resources are in a continuous state of interaction and flux, congruent with complexity models.

Considering the sustainability of the intervention or strategy is important. The ComHIP study in Ghana provided an example of using existing health service protocols and medications in Ghana and did not require outside funds or intervention for medications, which might improve the long-term sustainability of the intervention[37].

In 13 (72%) of the included studies, retention was not the primary or secondary outcome, and the interventions did not primarily focus on improving retention. This may partially explain why some studies reported lower retention rates in the intervention group than the control group. For example, a study in Kenya reported that only 21% of patients with hypertension had follow-up visits within 6 months, and 63% of these patients were adherent to clinic appointments after their follow-up visits[62]. The study in Ghana reported that 41% of total patients with hypertension had follow-up visits at 6 months, and 25% were retained in care at 12 months[63]. One key reason that impacted retention was health care professionals’ fatigue, because engaging patients to present for appointments required considerable effort, such as multiple phone calls and personal interaction, which were not compensated activities[37, 64]. Patients may also feel burdened with too many responsibilities by participating in a research study, which may have negatively impacted retention rates[36]. On the other hand, patients who participate in research studies typically have higher adherence and better outcomes than those observed in the general population[65].

Studies that used longer time horizons (e.g., 6 months or 12 months) for at least one follow-up visit did not necessarily report higher retention rates than those that used shorter time horizons. For example, in the Take Control of Your Blood Pressure (TCYB) study, the retention rate decreased in both intervention and control groups as the time course increased[38]. Dennison et al. reported the retention rates yearly in 5 years, which showed a fluctuating pattern of retention in both intervention and control groups[46].

When allocating resources to interventions to increase retention in hypertension, successful approaches from treatment programs for other chronic diseases, notably HIV, should be considered. For example, antiretroviral treatment programs may require direct physical patient tracing – an approach widely applied[66], which will need to be adapted for patients with hypertension given the differences of the scale of these two conditions[67]. The scale in hypertension is much bigger so setting up the infrastructures for non-physician health care workers or team-based care may be feasible for hypertension management. Because there is an increasing trend of task shifting and nurse-led care implemented in low-resource settings[68, 69], this may be beneficial for implementing the physical patient tracing intervention for hypertension care by taking advantage of the existing resources and infrastructures for HIV care.

Differentiated service delivery model has been shown to improve retention and medication adherence in HIV/AIDS studies[70], and promising evidence from non-communicable disease context has shown that similar interventions may be effective for hypertension management[71]. Differentiated service delivery models de-link medication dispensing from clinical examination for people established on treatment, which are more convenient for patients with hypertension and may be more efficient for overburdened health facility staff[72, 73].

Interventions in low- and middle-income countries also showed that community health workers can be an important resource in hypertension management[74-76]. A multi-level intervention focused on home visits by community health workers has demonstrated significant improvement in hypertension control in rural communities across three South Asian countries in a randomized controlled trial[77]. Team-based care, including non-physician health workers or laypeople, may expand the geographic coverage and reach of hypertension services[78]. Expanding the findings from these studies, this systematic review reinforces the notion that models that engage and educate the community on the importance of retention and empower patients to take a larger role in the management of hypertension may be feasible and result in improved retention.

Although differentiated service delivery models may lead to lower clinician-to-patient time on a per patient basis, these models still require relatively frequent interaction between patients and health care systems.[79] Differentiated service delivery models also aimed to incorporate team-based care. In most reported interventions, formally trained differentiated delivery staff, including community health care workers, outreach coordinators, and health educators, provided decentralized care, while trained clinical staff (i.e., doctors, nurses, pharmacists) continued to provide most facility-based services. Researchers and policymakers need more data to understand the feasibility, appropriateness, acceptability, effectiveness, and cost of implementing different types of differentiated service delivery models for patients with hypertension and other chronic conditions in their local context.[80, 81] The diversity we observed in such characteristics as the number of health systems interactions required for each model, or in the eligibility criteria for different models driven by target populations, will be crucial to make operational and budgetary decisions about how to optimize the distribution of models across facilities and regions.[82] We found that the extent to which the details of each model's design varied from one another and mattered to how well a model achieved the various goals of differentiated service delivery models, which illustrates important challenges of drawing generalizations about differentiated service delivery models from HIV for hypertension care.

This hermeneutic systematic review has several strengths. We developed a comprehensive search strategy in multiple databases on retention in hypertension care, and this report represents the most comprehensive review on this topic to date. Our methods allowed for a more conceptual investigation and mapping of interventions, their components, and contextual factors reported by the researchers to understand the state of the science for improving retention in hypertension care. The inclusion of different study designs (i.e., experimental, and quasi experimental trials, controlled before–after studies, or interrupted time series) enabled us to review different types of interventions used for improving hypertension retention. However, the understanding of a body of literature is an ongoing process. Boell et al. suggested that highly structured approaches in conventional systematic reviews downplay the importance of reading and dialogical interaction between the literature and researchers[11]. They argued for the continuing interpretation and questioning, critical assessment and imagination, argument development and writing, rather than solely replicability[11]. During the screening process, we found that many studies reported results for improving retention in HIV care. Given successful history of differentiated service delivery of HIV care, the hermeneutic process of differentiated service delivery enabled us to learn about experience and implications in retention from HIV care implications, which complemented the findings for hypertension care. We believe this study adds to previous work by using a formal, hermeneutic methodology, and by incorporating a wide range of literature.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, many included studies had limitations in design and reporting, such as inadequate details of interventions and context (including how and why interventions were chosen), heterogeneity of interventions and context, and difficulty in assessing intervention fidelity, risk of bias, and evaluation of implementation outcomes. Second, due to the heterogeneous nature of the selected studies, we did not perform a meta-analysis of the outcomes. Third, the proposed interventions and strategies in the original 18 selected studies were from limited geographic regions and had modest, and even mixed, effects in terms of improving retention; thus, these interventions may not be generalizable to other settings. Fourth, the mapping of the interventions to the WHO building blocks and ERIC compilation did not always fit into the original definitions. In addition, this study applied CFIR 1.0 version because the CFIR 2.0 version had not published until the research team extracted and mapped all the data from the selected papers[83]. However, the research team iteratively identified questions, discussed mapping results, and solicited suggestions. Future research includes adapting and testing differentiated service delivery models for hypertension care in collaboration with stakeholders within an ongoing hypertension treatment program in Nigeria (NCT04158154). The study team for this program has been conducting a community participatory research study that will incorporate stakeholder perspectives (i.e., patients, community health extension workers, nurses, pharmacists, researchers, administrators, policy makers, and physicians). The findings from this review will also serve as model inputs for: (1) protocol that uses systems dynamics modeling to improve retention, (2) study procedures for identifying and organizing multilevel inputs, and (3) estimating the direction and magnitude for a system dynamics model. The results should also lead to insights into the practical implementation of differentiated service delivery models of care for patients with hypertension, including ongoing activities in the Community Intervention to Reduce CardiovascuLar Disease in Chicago (CIRCL-Chicago) Implementation Research Center (NCT04755153)[16, 84].

CONCLUSION

This hermeneutic systematic review contributes to the knowledge by investigating the specific elements that contribute to the effectiveness and implementation of interventions and contextual factors for improving retention in care for patients with hypertension in primary care settings. The findings will be used to develop a systems-based approach for improving retention in hypertension care through an adapted differentiated service delivery care model.

Supplementary Material

Contributions to the literature.

This systematic review leveraged a hermeneutic methodology.

Identify and quantify interventions and contextual factors to improve retention.

The hermeneutic methods allowed for the investigation and mapping of retention.

This review presents the most comprehensive findings on retention in hypertension.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Linda O'Dwyer and Q. Eileen Wafford for their help with the development of the search strategies.

Funding:

This study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL144708) with additional support from the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1TR00422) and Robert J. Havey MD Institute for Global Health. OAS and JDS were supported by funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (UG3JL154297). The funders had no role in the design, conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations

- BP

Blood Pressure

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- CFIR

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- ERIC

Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change

- HEARTS

Healthy-lifestyle counselling; Evidence-based treatment protocols; Access to essential medicines and technology; Risk-based CVD management; Team-based care; Systems for monitoring

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Competing interests

MDH has planned patents for combination therapy for the treatment of heart failure. The George Institute for Global Health has a patent, license, and has received investment funding with intent to commercialize fixed-dose combination therapy through its social enterprise business, George Medicines. TLW receives research funding from Gilead Sciences. The other authors do not report any disclosures.

Protocol registration: PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021291368

Available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=291368

Disclosures: MDH has planned patents for combination therapy for the treatment of heart failure. The George Institute for Global Health has a patent, license, and has received investment funding with intent to commercialize fixed-dose combination therapy through its social enterprise business, George Medicines. TLW receives research funding from Gilead Sciences. The other authors do not report any disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang H, et al. , Global, regional, and national under-5 mortality, adult mortality, age-specific mortality, and life expectancy, 1970–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet, 2017. 390(10100): p. 1084–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Havas S, Roccella EJ, and Lenfant C, Reducing the public health burden from elevated blood pressure levels in the United States by lowering intake of dietary sodium. American Journal of Public Health, 2004. 94(1): p. 19–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akinlua JT, et al. , Current prevalence pattern of hypertension in Nigeria: A systematic review. PloS one, 2015. 10(10): p. e0140021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox AD, et al. , Health outcomes and retention in care following release from prison for patients of an urban post-incarceration transitions clinic. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 2014. 25(3): p. 1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Labhardt ND, et al. , Improved retention rates with low-cost interventions in hypertension and diabetes management in a rural African environment of nurse-led care: a cluster-randomised trial. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 2011. 16(10): p. 1276–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magadza C, Radloff S, and Srinivas S, The effect of an educational intervention on patients' knowledge about hypertension, beliefs about medicines, and adherence. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 2009. 5(4): p. 363–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vedanthan R, et al. , Community health workers improve linkage to hypertension care in western Kenya. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2019. 74(15): p. 1897–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vedanthan R, et al. , Optimizing linkage and retention to hypertension care in rural Kenya (LARK hypertension study): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 2014. 15(1): p. 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pastakia SD, et al. , Impact of bridging income generation with group integrated care (BIGPIC) on hypertension and diabetes in rural western Kenya. Journal of general internal medicine, 2017. 32(5): p. 540–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye J and Ma Q. The effects and patterns among mobile health, social determinants, and physical activity: a nationally representative cross-sectional study. in AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. 2021. American Medical Informatics Association. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boell SK and Cecez-Kecmanovic D, A hermeneutic approach for conducting literature reviews and literature searches. Communications of the Association for information Systems, 2014. 34(1): p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shea BJ, et al. , AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. bmj, 2017. 358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page MJ, et al. , The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 2021. 88: p. 105906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mugavero MJ, et al. , From access to engagement: measuring retention in outpatient HIV clinical care. AIDS patient care and STDs, 2010. 24(10): p. 607–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye J, et al. , Optimizing Longitudinal Retention in Care Among Patients With Hypertension in Primary Healthcare Settings: Findings From the Hypertension Treatment in Nigeria Program. Circulation, 2022. 146(Suppl_1): p. A13217–A13217. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Damschroder LJ, et al. , Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation science, 2009. 4(1): p. 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye J, et al. , Strategies and contextual factors to improve retention in care for patients with hypertension in primary care: Protocol for a systematic review. Available at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=291368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye J, The role of health technology and informatics in a global public health emergency: practices and implications from the COVID-19 pandemic. JMIR Medical Informatics, 2020. 8(7): p. e19866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye J, Wang Z, and Hai J, Social Networking Service, Patient-Generated Health Data, and Population Health Informatics: National Cross-sectional Study of Patterns and Implications of Leveraging Digital Technologies to Support Mental Health and Well-being. Journal of medical Internet research, 2022. 24(4): p. e30898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Babineau J, Product review: covidence (systematic review software). Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association/Journal de l'Association des bibliothèques de la santé du Canada, 2014. 35(2): p. 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization, Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. 2010: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waltz TJ, et al. , Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implementation Science, 2015. 10(1): p. 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, et al. , The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj, 2011. 343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sterne JA, et al. , ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions, bmj. 2016. 355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long L, et al. , Retention in care and viral suppression in differentiated service delivery models for HIV treatment delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a rapid systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 2020. 23(11): p. e25640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roy M, et al. , A review of differentiated service delivery for HIV treatment: effectiveness, mechanisms, targeting, and scale. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 2019. 16(4): p. 324–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duncombe C, et al. , Reframing HIV care: putting people at the centre of antiretroviral delivery. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 2015. 20(4): p. 430–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grimsrud A, et al. , Reimagining HIV service delivery: the role of differentiated care from prevention to suppression. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 2016. 19(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Bank Group, World Bank Country and Lending Groups 2020. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gessler N, et al. , The lesson of Monsieur Nouma: Effects of a culturally sensitive communication tool to improve health-seeking behavior in rural Cameroon. Patient Education and Counseling, 2012. 87(3): p. 343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aldabbagh L, Aldhalmi AK, and Al-Wehaab ZA, Dose early detection of hypertension through the early detection of hypertension program or inclusion of mobile communication improve hypertension outcomes in the attendees of primary healthcare centers in Najaf governorate. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 2020. 12(4): p. 3907–3917. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di M, et al. , Lack of effects of evidence-based, individualised counselling on medication use in insured patients with mild hypertension in China: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Evid Based Med, 2020. 25(3): p. 102–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldman PH, et al. , Reducing Hypertension in a Poststroke Black and Hispanic Home Care Population: Results of a Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Hypertens, 2020. 33(4): p. 362–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pealing LM, et al. , A randomised controlled trial of blood pressure selfmonitoring in the management of hypertensive pregnancy. OPTIMUM-BP: A feasibility trial. Pregnancy Hypertens, 2019. 18: p. 141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stewart S, et al. , More rigorous protocol adherence to intensive structured management improves blood pressure control in primary care: results from the Valsartan Intensified Primary carE Reduction of Blood Pressure study. J Hypertens, 2014. 32(6): p. 1342–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warner ET, et al. , Recruitment and retention of participants in a pragmatic randomized intervention trial at three community health clinics: results and lessons learned. BMC Public Health, 2013. 13: p. 192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adler AJ, et al. , Can a nurse-led community-based model of hypertension care improve hypertension control in Ghana? Results from the ComHIP cohort study. BMJ Open, 2019. 9(4): p. e026799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bosworth HB, et al. , Take Control of Your Blood Pressure (TCYB) study: a multifactorial tailored behavioral and educational intervention for achieving blood pressure control. Patient Educ Couns, 2008. 70(3): p. 338–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirsch JD, et al. , Primary care-based, pharmacist-physician collaborative medication-therapy management of hypertension: a randomized, pragmatic trial. Clin Ther, 2014. 36(9): p. 1244–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teo VH, et al. , Effects of technology-enabled blood pressure monitoring in primary care: A quasi-experimental trial. J Telemed Telecare, 2021: p. 1357633x211031780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gums TH, et al. , Pharmacist intervention for blood pressure control: medication intensification and adherence. J Am Soc Hypertens, 2015. 9(7): p. 569–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oti SO, et al. , Outcomes and costs of implementing a community-based intervention for hypertension in an urban slum in Kenya. Bull World Health Organ, 2016. 94(7): p. 501–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stewart K, et al. , A multifaceted pharmacist intervention to improve antihypertensive adherence: a cluster-randomized, controlled trial (HAPPy trial). J Clin Pharm Ther, 2014. 39(5): p. 527–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Labhardt ND, et al. , Task shifting to non-physician clinicians for integrated management of hypertension and diabetes in rural Cameroon: a programme assessment at two years. BMC Health Serv Res, 2010. 10: p. 339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Labhardt ND, et al. , Improved retention rates with low-cost interventions in hypertension and diabetes management in a rural African environment of nurse-led care: a cluster-randomised trial. Trop Med Int Health, 2011. 16(10): p. 1276–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dennison CR, et al. , Underserved urban african american men: hypertension trial outcomes and mortality during 5 years. Am J Hypertens, 2007. 20(2): p. 164–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huebschmann AG, et al. , Reducing clinical inertia in hypertension treatment: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich), 2012. 14(5): p. 322–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arora S, et al. , Project ECHO: A telementoring network model for continuing professional development. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 2017. 37(4): p. 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nelissen HE, et al. , Pharmacy-based hypertension care employing mHealth in Lagos, Nigeria–a mixed methods feasibility study. BMC health services research, 2018. 18(1): p. 934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ye J, Patient Safety of Perioperative Medication Through the Lens of Digital Health and Artificial Intelligence. JMIR Perioperative Medicine, 2023. 6: p. e34453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ye J and Ren Z, Examining the impact of sex differences and the COVID-19 pandemic on health and health care: findings from a national cross-sectional study. JAMIA Open, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boima V, et al. , Factors associated with medication nonadherence among hypertensives in Ghana and Nigeria. International journal of hypertension, 2015. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sikazwe I, et al. , Retention and viral suppression in a cohort of HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy in Zambia: Regionally representative estimates using a multistage-sampling-based approach. PLoS medicine, 2019. 16(5): p. e1002811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zanolini A, et al. , Understanding preferences for HIV care and treatment in Zambia: evidence from a discrete choice experiment among patients who have been lost to follow-up. PLoS medicine, 2018. 15(8): p. e1002636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ye J, et al. , Identifying Contextual Factors and Strategies for Practice Facilitation in Primary Care Quality Improvement Using an Informatics-Driven Model: Framework Development and Mixed Methods Case Study. JMIR Human Factors, 2022. 9(2): p. e32174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ye J, et al. , Leveraging natural language processing and geospatial time series model to analyze COVID-19 vaccination sentiment dynamics on Tweets. JAMIA Open, 2023. 6(2): p. ooad023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ye J, et al. , Identifying Practice Facilitation Delays and Barriers in Primary Care Quality Improvement. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine: JABFM, 2020. 33(5): p. 655–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ye J Design and development of an informatics-driven implementation research framework for primary care studies. in AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. 2021. American Medical Informatics Association. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Santo K, et al. , Adapting a club-based medication delivery strategy to a hypertension context: the CLUBMEDS Study in Nigeria. BMJ open, 2019. 9(7): p. e029824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Osetinsky B, et al. , Hypertension control and retention in care among HIV infected patients: the effects of co-located HIV and chronic non-communicable disease care. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999), 2019. 82(4): p. 399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ye J, et al. , Characteristics and Patterns of Retention in Hypertension Care in Primary Care Settings From the Hypertension Treatment in Nigeria Program. JAMA Network Open, 2022. 5(9): p. e2230025–e2230025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kuria N.e., et al. , Compliance with follow-up and adherence to medication in hypertensive patients in an urban informal settlement in Kenya: comparison of three models of care. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 2018. 23(7): p. 785–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adler AJ, et al. , Can a nurse-led community-based model of hypertension care improve hypertension control in Ghana? Results from the ComHIP cohort study. BMJ open, 2019. 9(4): p. e026799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ye J, Advancing mental health and psychological support for health care workers using digital technologies and platforms. JMIR Formative Research, 2021. 5(6): p. e22075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shrank WH, Patrick AR, and Alan Brookhart M, Healthy user and related biases in observational studies of preventive interventions: a primer for physicians. Journal of general internal medicine, 2011. 26(5): p. 546–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tweya H, et al. , Early active follow-up of patients on antiretroviral therapy (ART) who are lost to follow-up: the ‘Back-to-Care’project in Lilongwe, Malawi. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 2010. 15: p. 82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou B, et al. , Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. The Lancet, 2021. 398(10304): p. 957–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rosen S and Ketlhapile M, Cost of using a patient tracer to reduce loss to follow-up and ascertain patient status in a large antiretroviral therapy program in Johannesburg, South Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 2010. 15: p. 98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ye J, et al. , A portable urine analyzer based on colorimetric detection. Analytical Methods, 2017. 9(16): p. 2464–2471. [Google Scholar]

- 70.World Health Organization, Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, testing, treatment, service delivery and monitoring: recommendations for a public health approach. 2021: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Isiguzo GC, et al. , Adherence Clubs to Improve Hypertension Management in Nigeria: Clubmeds, a Feasibility Study. Global heart, 2022. 17(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bygrave H, et al. , Let's talk chronic disease: can differentiated service delivery address the syndemics of HIV, hypertension and diabetes? Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS, 2020. 15(4): p. 256–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ye J, The impact of electronic health record–integrated patient-generated health data on clinician burnout. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neupane D, et al. , Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention led by female community health volunteers versus usual care in blood pressure reduction (COBIN): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet Global Health, 2018. 6(1): p. e66–e73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ye J, Health Information System's Responses to COVID-19 Pandemic in China: A National Cross-sectional Study. Applied Clinical Informatics, 2021. 12(02): p. 399–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ye J, He L, and Beestrum M, Implications for implementation and adoption of telehealth in developing countries: a systematic review of China’s practices and experiences. npj Digital Medicine, 2023. 6(1): p. 174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jafar TH, et al. , A community-based intervention for managing hypertension in rural South Asia. New England Journal of Medicine, 2020. 382(8): p. 717–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kwon C, et al. , Community Group-Based Models of Medication Delivery: Applicability to Cardiovascular Diseases. Global heart, 2021. 16(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ye J, Pediatric Mental and Behavioral Health in the Period of Quarantine and Social Distancing With COVID-19. JMIR pediatrics and parenting, 2020. 3(2): p. e19867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ye J, et al. , Predicting mortality in critically ill patients with diabetes using machine learning and clinical notes. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 2020. 20(11): p. 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ye J and Sanchez-Pinto LN. Three data-driven phenotypes of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome preserved from early childhood to middle adulthood. in AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. 2020. American Medical Informatics Association. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ye J, et al. , The Roles of Electronic Health Records for Clinical Trials in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Scoping Review. JMIR Medical Informatics, 2023. 11: p. e47052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Damschroder LJ, et al. , The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implementation Science, 2022. 17(1): p. 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Smith J, et al. Equitable implementation to eliminate cardiovascular health disparities on Chicago's south side: A description of implementation preparation activities. in IMPLEMENTATION SCIENCE. 2022. BMC CAMPUS, 4 CRINAN ST, LONDON N1 9XW, ENGLAND. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.