Abstract

Neural oscillations are associated with diverse computations in the mammalian brain. The waveform shape of oscillatory activity measured in the cortex relates to local physiology and can be informative about aberrant or dynamically changing states. However, how waveform shape differs across distant yet functionally and anatomically related cortical regions is largely unknown. In this study, we capitalize on simultaneous recordings of local field potentials (LFPs) in the auditory and frontal cortices of awake, male Carollia perspicillata bats to examine, on a cycle-by-cycle basis, waveform shape differences across cortical regions. We find that waveform shape differs markedly in the fronto-auditory circuit even for temporally correlated rhythmic activity in comparable frequency ranges (i.e., in the delta and gamma bands) during spontaneous activity. In addition, we report consistent differences between areas in the variability of waveform shape across individual cycles. A conceptual model predicts higher spike–spike and spike–LFP correlations in regions with more asymmetric shapes, a phenomenon that was observed in the data: spike–spike and spike–LFP correlations were higher in the frontal cortex. The model suggests a relationship between waveform shape differences and differences in spike correlations across cortical areas. Altogether, these results indicate that oscillatory activity in the frontal and auditory cortex possesses distinct dynamics related to the anatomical and functional diversity of the fronto-auditory circuit.

Keywords: auditory cortex, frontal cortex, local field potential, oscillations, spike trains, waveform shape

Significance Statement

The brain activity of many animals displays intricate oscillations, which are usually characterized in terms of their frequency and amplitude. Here, we study oscillations from the bat frontal and auditory cortices on a cycle-by-cycle basis, additionally focusing on their characteristic waveform shape. The study reveals clear differences across regions in waveform shape and oscillatory regularity, even when the frequency of the oscillations is similar. A conceptual model predicts that more asymmetric waveforms result from stronger correlations between neural spikes and electrical field activity. Such predictions were supported by the data. The findings shed light onto the unique properties of different cortical areas, providing key insights into the distinctive physiology and functional diversity within the fronto-auditory circuit.

Introduction

Rhythmic neural activity at various timescales underpins several functions in the mammalian brain. In the frontal cortex, oscillations of local field potentials (LFPs) in low and high frequencies are implicated in cognitive and executive control (Insel et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2016; Helfrich and Knight, 2019; Rajan et al., 2019; Veniero et al., 2021; Tavares and Tort, 2022), while rhythmic activity in sensory cortices is linked with the effective encoding of incoming stimuli (Gross et al., 2007; Lakatos et al., 2007; Teng et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2019; Gourevitch et al., 2020; Kienitz et al., 2021; Uran et al., 2022). These oscillations reflect the underlying dynamics of their generating motifs, which determine several of their properties, including waveform shape (Cole and Voytek, 2017). Indeed, waveform shape and related features change in the developing brain (Schaworonkow and Voytek, 2021) and possess atypical characteristics in disease (Cole et al., 2017; Cole and Voytek, 2019; Jackson et al., 2019). Waveform patterns of oscillatory activity can provide important insights into the physiology and function of the neocortex, yet how they differ across cortical regions remains largely unstudied.

In this work, we examine oscillatory waveform shape in the frontal and auditory cortices of a mammalian vocal specialist, the bat Carollia perspicillata. The bat auditory cortex (AC) is a well-studied structure that presents both spontaneous and stimulus-driven rhythmic patterns of neuronal activity (Medvedev and Kanwal, 2004; Hechavarria et al., 2016; Garcia-Rosales et al., 2019). As in other mammals (Lakatos et al., 2005; Luo and Poeppel, 2007; Teng et al., 2017; Neymotin et al., 2022), LFPs in the bat AC track the temporal dynamics of acoustic sequences with periodic and quasiperiodic temporal structures (Garcia-Rosales et al., 2018). LFPs in C. perspicillata's AC exhibit clear coupling with neuronal spiking, potentially coordinating single-cell responses to acoustic stimuli and contributing actively to the encoding of multisyllabic communication sounds (Garcia-Rosales et al., 2018).

In the frontal cortex, we focused on the frontal auditory field (FAF), a structure specialized in auditory-related behavior (Kobler et al., 1987; Eiermann and Esser, 2000; Kanwal et al., 2000). This region is anatomically connected with the AC but receives also relatively fast inputs from an alternative pathway bypassing the midbrain and cortex (Kobler et al., 1987). Pre- and postvocal dynamics in the FAF, as well as its functional connectivity patterns with the AC and the striatum, implicate this region in the control of vocalization behavior (Weineck et al., 2020; Garcia-Rosales et al., 2022b). Furthermore, the FAF is anatomically connected with the superior colliculus, suggesting that it may be involved in coordinating fast movements based on the bat's auditory environment (Kobler et al., 1987; Casseday et al., 1989). The nature of FAF–AC interconnectivity suggests that the FAF plays a crucial role in the integration of auditory feedback for the coordination of rapid auditory-based behavior (Garcia-Rosales et al., 2022b). These data indicate that, while the AC operates as a classical sensory cortex, the FAF acts as part of a control and integration hub.

While low- and high-frequency oscillatory activities in the bat FAF–AC network are functionally related, it is unknown how they differ in terms of waveform shape. Characterizing waveform shape differences across cortical regions could be an informative step toward understanding how neuronal oscillations in these areas differ and thus constrain hypotheses about the mechanisms underlying neural activity across structures. By means of simultaneous electrophysiological recordings and cycle-by-cycle analyses of neural oscillations, we show that the waveform shape and variability of frontal- and auditory cortical oscillations differ markedly in delta and gamma frequencies. We demonstrate a relationship between waveform shape and spike correlations by modeling and computing spike-field measures. We argue that these differences reflect physiological disparities in the FAF–AC circuit and establish a potential link between spike timing and waveform shape. Our results support the notion of heterogeneity of cortical rhythms in the mammalian brain and stress the importance of waveform shape for understanding cortical physiology and function.

Materials and Methods

Animal preparation and surgical procedures

The study was conducted on two awake Carollia perspicillata bats (two males), which were obtained from a colony at the Goethe University Frankfurt. All experimental procedures were in compliance with European regulation and were approved by the relevant local authorities (Regierungspräsidium Darmstadt, experimental permit #FU-1126). Animals used in experiments were kept isolated from the main colony, with a reversed light/dark cycle (i.e., lights off from 12:00 to 00:00; this applies to all bats in the colony as well).

The data presented in this work were collected as part of a previous study (Garcia-Rosales et al., 2022b), where a detailed description of the surgical procedures can be found. In brief, bats were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (10 mgkg−1, Ketavet, Pfizer) and xylazine (38 mgkg−1, Rompun, Bayer) and underwent surgery in order to expose the skull in the areas of the frontal and auditory cortices. A metal rod (∼1 cm length, 0.1 cm diameter) was glued onto the bone for head fixation during electrophysiological recordings. A local anesthetic (ropivacaine hydrochloride, 2 mg/ml, Fresenius Kabi) was applied subcutaneously around the scalp area prior to any handling of the wounds. The precise locations of the FAF and AC were determined by means of well-described landmarks, including the sulcus anterior and prominent blood vessel patterns (Esser and Eiermann, 1999; Eiermann and Esser, 2000; Garcia-Rosales et al., 2020). Access to the frontal and auditory regions of the left hemisphere was gained by cutting small holes (∼1 mm2) with a scalpel blade on the first day of recordings. Electrophysiological recordings in the AC were made mostly in the high-frequency fields (Esser and Eiermann, 1999).

After the surgery animals were given sufficient time to recover (no less than 2 d) before the beginning of experimental sessions. A session did not last >4 h per day. Water was offered to the bats every 1–1.5 h. Experiments were halted if an animal showed any signs of discomfort (e.g., excessive movement). No animal was used on 2 consecutive days for recordings.

Electrophysiological recordings

Electrophysiological measurements were made acutely from fully awake animals in a sound-proofed and electrically isolated chamber. Inside the chamber, bats were placed on a custom-made holder kept at a constant temperature of 30°C using a heating blanket (Harvard homeothermic blanket control unit). Data were acquired simultaneously from the FAF and AC of the left hemisphere using two 16-channel laminar probes (Model A1 × 16, NeuroNexus, MI; 50 μm channel spacing; impedance, 0.5–3 MΩ per electrode). For each paired FAF–AC recording, probes were carefully inserted into the tissue using piezo manipulators (one per probe; PM-101, Science Products), perpendicular to the cortical surface, until the top channel was barely visible above the surface. The typical width of C. perspicillata's cortex and the total span of the electrodes in the probes (750 µm) allowed us to record from all six cortical layers at once (Garcia-Rosales et al., 2019, 2022b). From one paired recording to the next in the same experimental session, probes were retracted from the cortical tissue and moved to a new location within the craniotomy in the FAF or AC, as distant as possible from the previous recording sites within that craniotomy. New recording locations were chosen at the beginning of each experimental session.

Probes in the FAF and AC were connected to micropreamplifiers (μPA16, Multi Channel Systems), while acquisition was done with a single 32-channel system with integrated digitization (sampling frequency, 20 kHz; precision, 16 bits) and amplification steps (Multi Channel Systems, model ME32 System). Silver wires were used as reference electrodes for each recording shank (i.e., in the FAF and AC) placed at different areas of the brain (for the FAF, nonauditory lateral ipsilateral region; for the AC, nonauditory occipital ipsilateral region). The silver wires were carefully positioned between the skull and the dura matter. The reference and the ground of each probe were short-circuited, and the ground was ultimately common in the acquisition system (the ME32). Recordings were monitored online and stored in a computer using the MC_Rack_Software (Multi Channel Systems; version 4.6.2). Due to technical reasons, the signal from one FAF channel (depth, 500 µm) was linearly interpolated from its immediate neighbors.

Preprocessing of spiking and LFP signals

All data analyses were made using custom-written Python scripts. Raw data from the recording system were converted to H5 format using Multi Channel System's McsPyDataTools package (https://github.com/multichannelsystems/McsPyDataTools, version 0.4.3) and were then parsed and handled with Syncopy (https://github.com/esi-neuroscience/syncopy, version 2022.8). LFPs were obtained by filtering the raw data with a low-pass Butterworth filter (fourth order) with a cutoff frequency of 300 Hz. For computational convenience, LFP signals were then downsampled to 5 kHz. On occasions a sharp spectral peak at 100 Hz was present in the recordings, corresponding to a harmonic of the line noise. We were discouraged from using LFPs close (or above) to 100 Hz in the analyses for the following reasons: (1) frequencies close to 100 Hz would be affected by the line noise harmonic, and (2) high-frequency LFPs (>100 Hz) can be directly influenced by spiking activity in the form of, for example, spike bleed-through (Ray, 2015). Spike bleed-through constitutes a potential confound that we sought to avoid.

For the detection of multiunit activity, the raw data were bandpass filtered between 300 and 3,000 Hz with a fourth-order Butterworth filter. Spikes were detected based on threshold crossing: We defined a spike as a peak with an amplitude of at least 3.5 standard deviations relative to all samples in the signal. Only peaks separated by at least 2 ms were considered.

Spectral analyses

Power spectral densities (PSDs) were computed using Welch's method (segment length 20,480 samples, i.e., 4,096 ms) implemented in scipy (version 1.9.1). PSDs were calculated independently for each LFP trace (all channels in the N = 29 recordings in both FAF and AC). LFP traces were typically approximately, but not shorter than, 1,200 s long (median, 1,239.5 s; 25th percentile, 1,252.8 s; 75th percentile, 1,423.9 s). The power of each recording was parametrized using a spectral parametrization model (Donoghue et al., 2020), with which a 1/f fit of the PSD was computed. All fits had an R2 > 0.93 (mean, 0.9965; SEM, 0.001).

We reasoned that significant deviations of the power spectrum from the 1/f fit potentially represented oscillatory activity at a given frequency range. Thus, we normalized each power spectrum by its 1/f component to highlight spectral peaks in the FAF and AC. Normalized values would hover ∼0 in the case of no spectral peaks and would be consistently >0 for frequencies in which LFPs presented clear deviations from the underlying 1/f trend. For each channel, we considered a significant deviation from the 1/f if the normalized power at a certain frequency was significantly larger than 0 (FDR-corrected, two-sided one-sample t tests, pcorr < 0.05). This analysis was done for each individual animal (Bat-01, N = 15; Bat-02, N = 14), for frequencies ranging from 1 to 120 Hz. From the results in the two bats, we established the following frequency bands of interest: delta (1–4 Hz) and gamma (65–85 Hz).

Cycle-by-cycle analyses

For detecting oscillatory bursts in the frequencies of interest, we used the bycycle package [(Cole and Voytek, 2019), version 1.0.0]. The bycycle algorithm makes it possible to detect individual cycles in a frequency range of interest (here, the frequency bands outlined above) and then to determine whether detected cycles belong to so-called oscillatory bursts. An oscillatory burst consists of a sequence of cycles (at least three in this study) with stable temporal properties that are mainly summarized as follows: amplitude consistency, period consistency, and monotonicity (rise and decay flanks of cycles in a burst should be mostly monotonic). Furthermore, one parameter controls for signal-to-noise ratio (SNR): the amplitude fraction threshold (Fig. 2A). This parameter rejects cycles whose amplitudes are below a certain percentile relative to the amplitude of all cycles in a given trace. As in a previous study (Schaworonkow and Voytek, 2021), we chose the following thresholds for cycle detection: amplitude fraction threshold, 0.5; amplitude consistency threshold, 0.5; period consistency threshold, 0.5; and monotonicity threshold, 0.5.

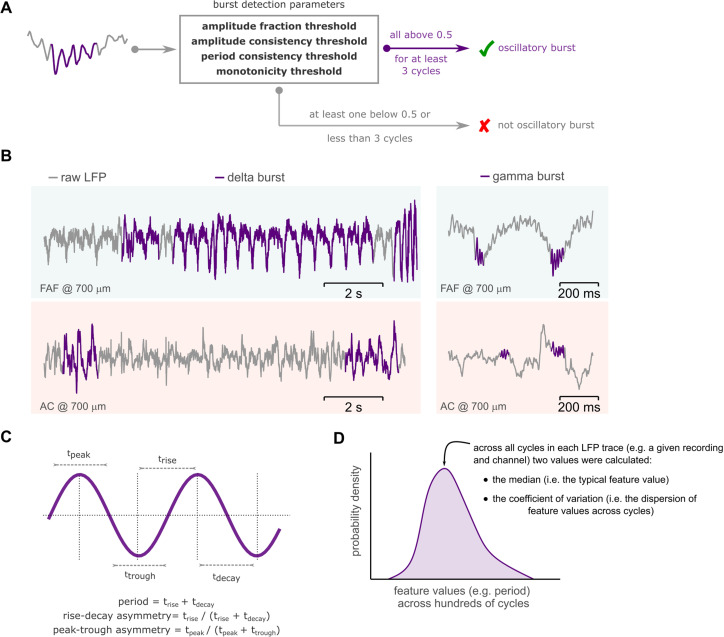

Figure 2.

Burst cycle features and the CV. A, Schematic representation of the oscillatory burst detection algorithm. If at least three consecutive cycles exceeded the thresholds of the detection parameters (enclosed in the box), these cycles together were considered an oscillatory burst (marked in purple); otherwise, no burst was detected. No-burst cycles were not used in further analyses. B, Representative delta- and gamma-frequency bursting activity (bursts marked in purple) in the FAF and AC, at a cortical depth of 700 µm. C, Illustration of cycle waveform features: period, rise–decay asymmetry, and peak–trough asymmetry. An artificial sinusoidal waveform was utilized for illustrative purposes. D, The median value for a given feature (e.g., period) across all cycles was used as the value of that feature for a given LFP trace. The CV across all feature values was used as a measure of dispersion. Shown in the figure (in purple) is a schematic distribution of feature values for a given LFP recording.

Each cycle was characterized according to the following features, which determine waveform shape: cycle period (i.e., the duration of each cycle), cycle rise–decay asymmetry (the asymmetry between rise and decay times in the cycle), and cycle peak–trough asymmetry (the asymmetry in duty cycle; Cole and Voytek, 2019; Schaworonkow and Voytek, 2021). Bursts were characterized according to their duration (the sum of the individual duration of each cycle in the burst). Only cycles that were part of oscillatory bursts were used for further analyses.

To compare cycle features across different recording sites (e.g., between channels in the FAF and AC), we defined the value of a given feature for a certain recording as the median value of that feature across all detected cycles in the recording. This was made per LFP trace, therefore yielding one value per recording site (N = 29 paired FAF–AC sites, across 16 channels; data from the two bats were pooled as spectral and bursting patterns were highly consistent across animals). Given that data from FAF and AC were acquired simultaneously for each paired recording, the above allowed us to compare across sites using paired statistics (FDR-corrected Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, significant for pcorr < 0.05). Only values derived from simultaneously recorded LFP traces were compared with one another.

A median asymmetry value of 0.5 for a given LFP trace indicates that cycles tend toward a sinusoidal shape. The farther the value is from 0.5 (above or below) the more asymmetric a waveform is. However, whether such values lie above or below the 0.5 threshold strongly depends on signal polarity. Note, for example, that a certain signal and its copy, the latter with inverse polarity, will have values of asymmetry equally distanced from 0.5 but in opposite directions (as peaks become troughs with a polarity inversion). Thus, not controlling for signal polarity can be a strong confound when comparing waveform shape asymmetries, especially if these are calculated from electrodes located in different brain regions, which already have dissimilar cytoarchitectures, such as the frontal and auditory cortices. Since we are unable to control for signal polarity in the current dataset, we avoid this potential confound by normalizing median asymmetry values to 0.5. That is, the asymmetry value for a given LFP trace used for comparisons is given by the absolute value of the difference between its raw asymmetry and 0.5. This approach measures how far from sinusoidal the waveform shape of an LFP trace is, independently of signal polarity (Schaworonkow and Voytek, 2021), and is therefore better suited for interareal comparisons of waveform shape asymmetry.

The aforementioned cycle features characterize waveform shape, but they do not quantify to what degree individual burst cycles in a given LFP trace are similar to one another. This is measured by the dispersion of the distribution of the cycle features, which was quantified here as the coefficient of variation (CV). The CV is computed over each LFP trace, therefore quantifying cycle-by-cycle the variability over time; it is expressed as follows:

| (1) |

where is the standard deviation of the cycle feature distribution (W) and is its mean.

Every recording in the frontal or AC had a specific CV for a given cycle parameter, channel, and frequency band. As described with median feature values, this enabled us to conduct paired statistics when comparing CV values between the FAF and AC (FDR-corrected Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, significant for pcorr < 0.05). The CV was calculated from raw feature values (not normalized to 0.5) across all cycles in a given signal, given that this metric is not affected by signal polarity as it is self-contained for each LFP trace. This allows us to explore cycle-by-cycle variability over time without affecting the individual asymmetry values of the cycles involved.

Sensitivity analyses

For the evaluation of the dependence of significant differences across cortical structures on the burst detection parameters of the bycycle algorithm, bursts were detected as above, but detection parameters were varied in pairs as follows: (1) amplitude fraction threshold versus amplitude consistency threshold; (2) amplitude fraction threshold versus period consistency threshold; and (3) amplitude fraction threshold versus monotonicity threshold. The same parameter values were used to detect bursts in the FAF and AC. However, we also evaluated to what degree our results were sensitive to different burst detection parameters across regions, varying the amplitude fraction threshold independently in each area (Fig. 7). Parameters were varied in the range from 0.1 to 0.9, with a step of 0.1. All waveform features were computed as described above, and the variability of waveform features was measured as the CV. As in the original analyses, all channels were statistically compared against each other. We then determined the median of the effect size of comparisons across areas (i.e., the median effect size of the upper-right quadrant of the comparison matrices in Figures 5 and 6; effect sizes of nonsignificant comparisons were set to 0) and plotted this median against parameter combinations (Fig. 7) to determine how changing detection parameters affected the reported interareal differences.

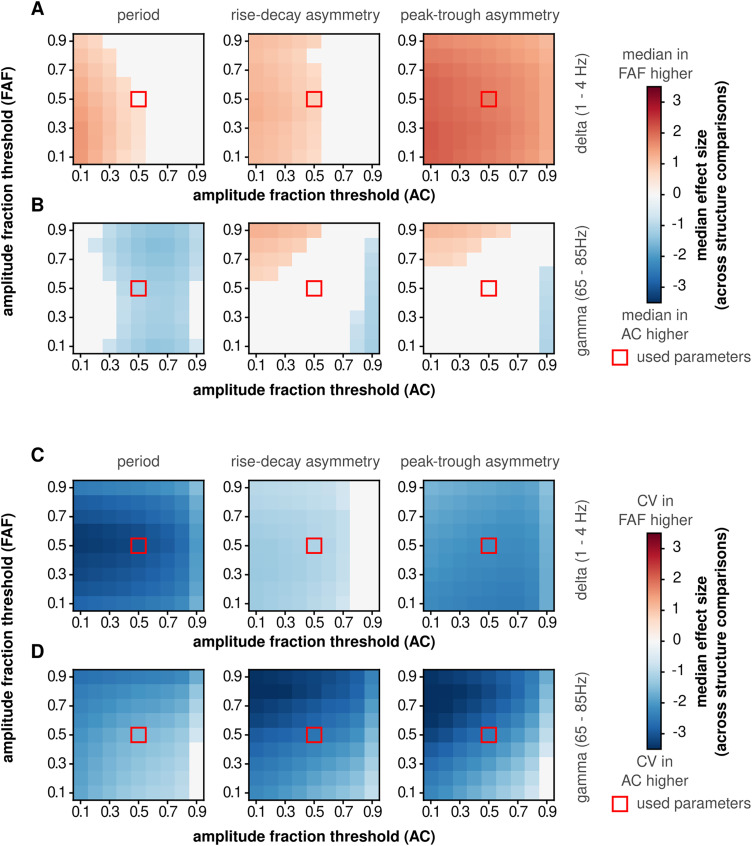

Figure 7.

Differences in waveform shape features and their variability are robust against burst detection amplitude threshold. The burst detection parameter “amplitude fraction threshold” was varied independently in the FAF and AC to determine whether SNR critically contributes to differences in oscillatory regularity between frontal and auditory areas. The difference across regions was measured as the median effect size obtained from comparing all pairs of channels in the FAF and AC (e.g., the median of the upper-right quadrant in the comparison matrices in Fig. 5, labeled “interareal comparisons”). In the absence of significant differences (FDR-corrected Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, pcorr < 0.05), effect size values were set to 0 (pcorr ≥ 0.05). A, Median effect sizes across all values of amplitude fraction threshold tested in the FAF and AC, for delta frequencies, comparing the median of cycle periods (left), cycle rise–decay asymmetries (middle), and cycle peak–trough asymmetries (right). B, Similar to panel A, but data correspond to cycles from gamma-band oscillatory bursts. C, D, Similar to panels A and B, but the CV was calculated for each cycle feature. The red squares indicate the amplitude fraction threshold values used to detect bursts used in the main results.

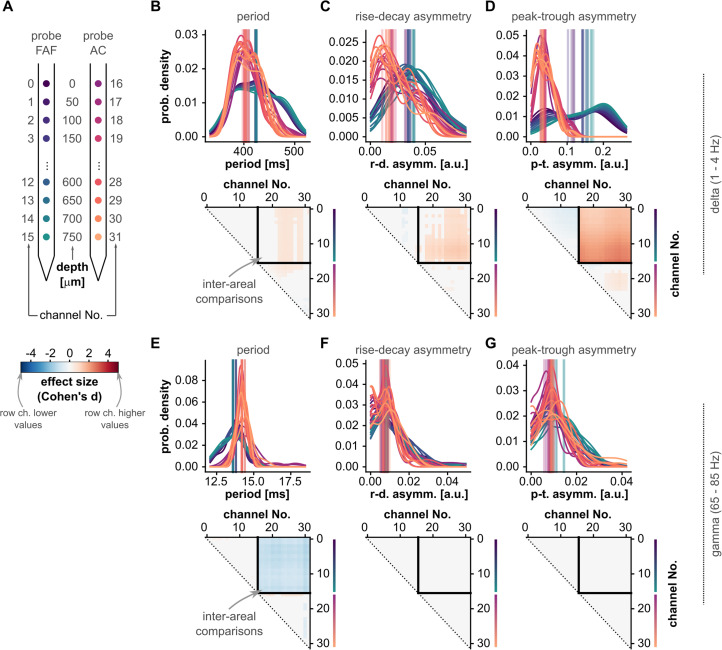

Figure 5.

Waveform shape differences between frontal and auditory cortical LFPs. A, Schematic illustrating the relationship of region and cortical depth with the channel number markers of panels B–G. Notice that depths are color-coded as in Figure 1. B, Top: distribution of oscillatory cycle periods across all recordings (N = 29; for each recording, the median period across all cycles is considered), for all channels (in the FAF and AC; see panel A for region and depth according to color), in the delta band. Vertical lines indicate the median of each distribution. Bottom: effect sizes of pairwise statistical comparisons of population-level period values across all channels (FDR-corrected Wilcoxon signed-rank tests). Effect sizes for comparisons that did not yield significance (i.e., pcorr ≥ 0.05) were set to 0. A cell (r, c) in the effect size matrix indicates the effect size of the comparison between values in channel r and channel c (as per panel A). The quadrant spanning rows (0–15) and columns (16–31) illustrate the effect sizes of comparisons between channels in the FAF and AC. In this quadrant, the blue colors indicate lower periods in the FAF. C, Similar to panel B, but corresponding to values of cycle feature “rise–decay asymmetry.” D, Similar to panel C, but related to values of cycle feature “peak–trough asymmetry.” E–G, Similar to panels B–D, but shown for values obtained using gamma-band oscillatory cycles.

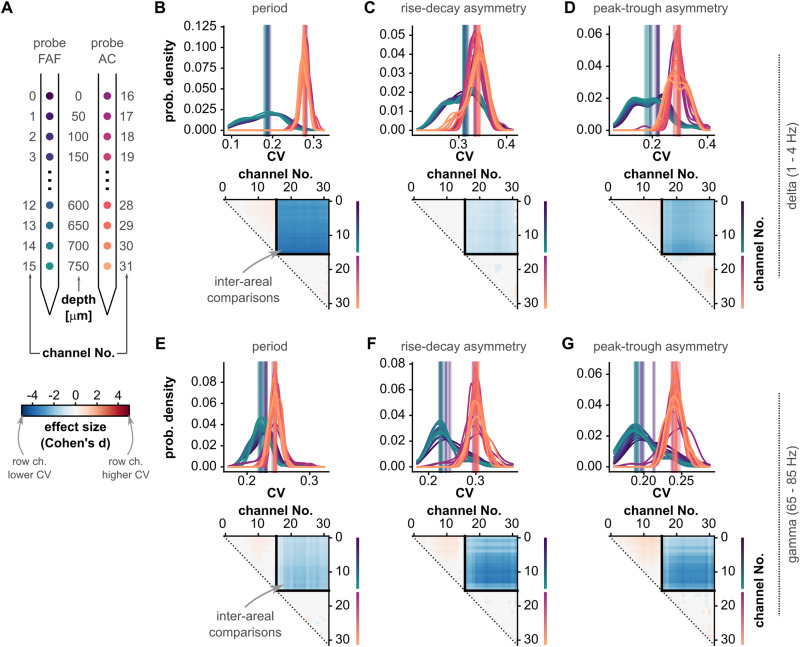

Figure 6.

The variability of waveform shape features differs between frontal and auditory regions. A, Schematic illustrating the relationship of region and cortical depth with the channel number markers of panels B–G. Notice that depths are color-coded as in Figure 1. B, Top: distribution of CV values for oscillatory cycle periods across all recordings (N = 29), for all channels (in the FAF and AC; see panel A for region and depth according to color), in the delta band. The vertical lines indicate the median of each distribution. Bottom: effect sizes of pairwise statistical comparisons of population CV values across all channels (FDR-corrected Wilcoxon signed-rank tests). Effect sizes for comparisons that did not yield significance (i.e., pcorr ≥ 0.05) were set to 0. A cell (r, c) in the effect size matrix indicates the effect size of the comparison between CV values in channel r and channel c (as per panel A). The quadrant spanning rows (0–15) and columns (16–31) illustrates the effect sizes of comparisons between channels in the FAF and AC. In this quadrant, the blue colors indicate lower CV values in the FAF. C, Similar to panel B, but corresponding to CV values of cycle feature “rise–decay asymmetry.” D, Similar to panel C, but related to CV values of cycle feature “peak–trough asymmetry.” E–G, Similar to panels B–D, but shown for CV values obtained using gamma-band oscillatory cycles (effect sizes can be interpreted as follows: d < 0.5 small, 0.5 ≤ d ≤ 0.8 medium, d > 0.8 large).

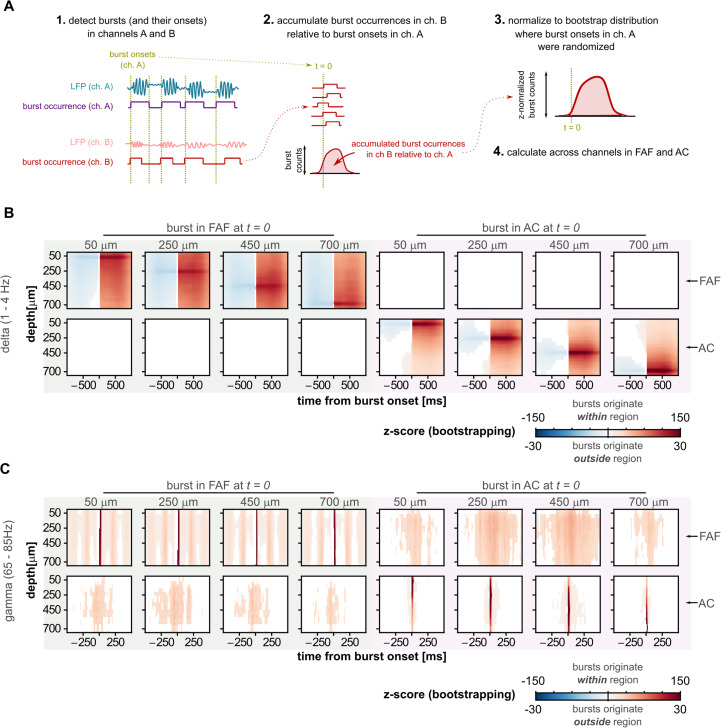

Burst co-occurrence analysis

The relationship between the onset of a burst in a specific channel and the cumulative burst co-occurrence with all other channels was calculated as follows. First, given a certain channel (e.g., channel A, for convenience), we determined the onset of all bursts detected across all recordings (the data from the two bats were pooled given that spectral and bursting patterns were highly consistent across animals). In a time window centered on each burst (spanning from −1,000 to 1,000 ms for delta frequencies and from −250 to 250 ms for the gamma frequencies), we counted and accumulated, for every channel, the time points at which bursts occurred. Bursts were counted even if their onset or offset were outside the aforementioned window, as long as at least a segment of the burst occurred within that window. For every given channel (channel A in this example) this procedure yielded a matrix (dimension, channels by samples) whose values indicate the accumulated, co-occurring bursting activity in each other electrode, relative to the times in which a burst onset occurred in the channel of interest (i.e., A in this case). We referred to this matrix as a channel's burst co-occurrence matrix. Burst co-occurrence matrices were computed for eight channels, four in the FAF and four in the AC (at depths of 50, 250, 450, and 700 µm). This reduced computational costs and facilitated visualization, while at the same time allowing exploration of burst co-occurrences at various depths in each region including superficial, middle, and deep layers of the cortex.

In order to evaluate whether the onset of a burst in a given electrode was related to the occurrence of bursts in other electrodes, the burst co-occurrence matrix for the channel of interest (e.g., channel A) was normalized following a bootstrapping procedure. We calculated 500 bootstrap burst co-occurrence matrices, but instead of utilizing burst onsets as a reference, pseudorandom time points were used. Because the accumulated number of co-occurring bursts across channels depends on the number of burst onsets used from the reference channel (A), we ensured that the number of randomized time points was equal to the number of burst onsets individually for each recording. The 500 pseudorandom burst co-occurrence matrices were used as a baseline distribution, and the values of the burst co-occurrence matrix for the channel of interest A were then Z-normalized relative to the bootstrap matrices. Absolute Z-score values ≥6 were considered significant. Note that Bonferroni’s correction of an α of 0.05 over 32 channels, 2 frequency bands, 8 channels of interest, and 1,000 time points yields a significance threshold of 9.7 × 10−8, equivalent to a Z-score of 5.2. In our analysis, negative Z-scores indicate a suppression of burst activity relative to baseline, while positive values indicate an enhancement. These procedures are illustrated in Figure 4A.

Figure 4.

Burst co-occurrence in the FAF–AC circuit. A, Schematic representation of the analysis for quantifying temporal co-occurrence of bursting events. Note that channels A and B could be drawn from the same or different cortical regions. B, Left (shaded green): delta-band burst co-occurrence across all channels, calculated relative to the onset of a burst at four representative depths (50, 250, 450, 700 µm) in the FAF. Matrices in the top row show burst co-occurrence in FAF channels; matrices in the bottom show co-occurrence of bursts in AC channels, aligned to burst onsets in the FAF (at t = 0). Burst co-occurrence values were Z-normalized relative to a bootstrapped baseline (blue colors, suppression of bursting activity; red colors, increased bursting activity). Only Z-normalized values considered significant (z > 6, see Materials and Methods) are shown. Right (shaded pink): similar information, but in this case, bursts originate in the AC at the same four representative depths (50, 250, 450, 700 µm). Here, t = 0 is aligned to auditory cortical burst onsets. C, Similar to panel B, but depicting data related to the gamma-frequency band. Note that burst co-occurrence matrices corresponding to bursts originating within a specific area (i.e., FAF or AC) are shown with a different color scale than those corresponding to bursts originating outside a given area.

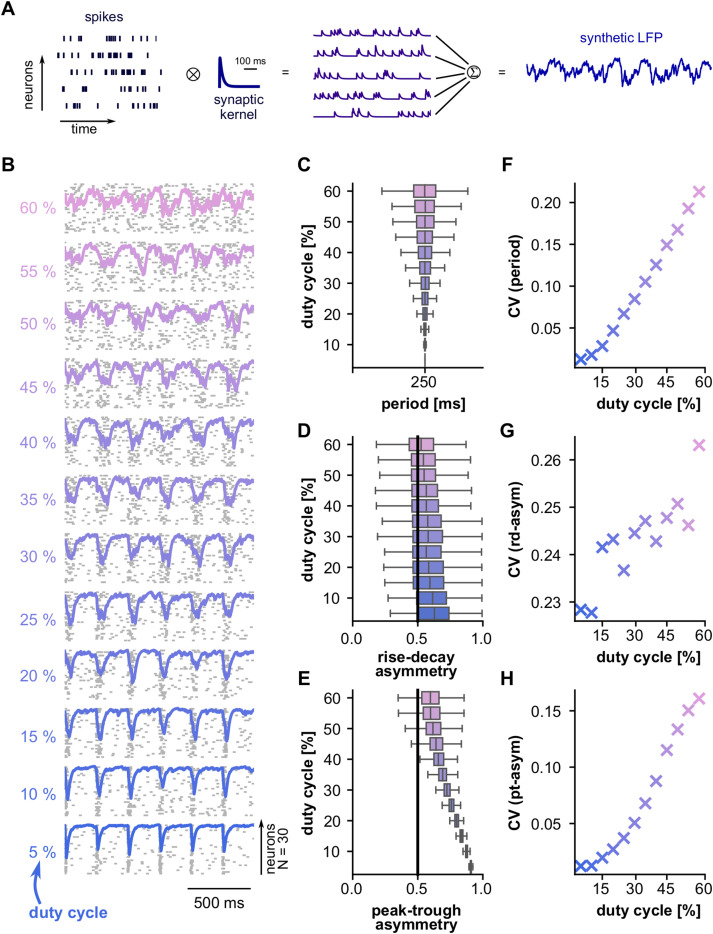

A conceptual model of spike correlations and LFP waveform shape

Synthetic spike trains were modeled as inhomogeneous Poisson processes with firing rates controlled by a pulse train with a frequency of 3 Hz. The duty cycle of the pulse train defines a temporal window in which spiking occurs. Narrow spiking windows (i.e., lower duty cycles) constrain the firing of a neural population in time, resulting in increased temporal correlations across neurons. In contrast, wider spiking windows (i.e., higher duty cycles) result in decreased temporal spiking correlations across neurons. By systematically adjusting the duty cycles, we were therefore able to explore how temporal correlations in a neuronal population (N = 30 neurons in our model) might affect LFP waveform shape.

From the spiking activity, we derived synthetic LFP signals as follows. The spike train of each simulated neuron was convoluted with a synaptic kernel whose rise and decay times were set to 1 and 20 ms, respectively (function sim_synaptic_kernel of the python package NeuroDSP, version 2.2.1; Cole et al., 2019). The sum of all convolutions was taken as the LFP signal. The procedure is illustrated in Figure 8A. We generated 300 s of spikes and LFPs for several values of duty cycles (5–60%; step, 5%). Cycle features were extracted from the synthetic LFPs by applying the bycycle algorithm described above.

Figure 8.

A linear model captures the differences in waveform shape between the FAF and AC. A, Schematic illustrating how synthetic LFP signals were derived from the spiking activity of a population of simulated neurons. B, Representative spiking activity of a population of N = 30 simulated neurons. The synchronicity across neurons varies with the duty cycle of a pulse train modulating firing rate (lower duty cycle, more synchronous; see Materials and Methods). A synthetic LFP was calculated for each condition (overlaid traces; see panel A). C–E, The period (C), rise–decay asymmetry (D), and peak–trough asymmetry (E) values across all cycles detected by the bycycle algorithm for each duty cycle tested. The black line in panels D and E represents no asymmetry (i.e., a value of 0.5). F–H, CV values of features period (F), rise–decay asymmetry (G), and peak–trough asymmetry (H). In panels C–H, values from each duty cycle simulation are color-coded according to panel B.

Spike–spike correlations

All detected spiking events (see above) were included to calculate spike train correlations across channels. Spike trains were binned using 5 ms bins, and the Pearson's correlation coefficient across pairs of binned spike trains was computed using the Elephant toolbox (v. 0.12.0; https://github.com/NeuralEnsemble/elephant). Correlation coefficients from channels located in the FAF were averaged, and the same was done for channels located in the AC. This yielded one correlation value per recording in the FAF and AC, which allowed us to capitalize on simultaneous recordings in both regions by means of paired statistical comparisons (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, α = 0.05).

Pairwise phase consistency

The pairwise phase consistency (PPC) was computed as described in previous literature (Vinck et al., 2010). Only spikes that occurred within oscillatory bursts in the FAF or AC were considered. If >10,000 spikes were detected in a given trace, 10,000 spikes were randomly selected to calculate PPC given that analyses were computationally expensive for large spike counts. In order to minimize the risk of asymmetric signals yielding unclear measurements of phase, spike phases were not obtained by means of a Hilbert transform or a Fourier analysis. Instead, the timing of a spike was expressed as the time in which the event occurred relative to the onset and offset of a cycle as detected in the time series by the bycycle algorithm. Thus, each spike timing was between 0 and 1 (0 being the beginning of a burst cycle and 1 being the end) and was converted to a phase by multiplication with 2π. These phases were then used for PPC calculation, which can be expressed as follows (Vinck et al., 2010):

| (2) |

where N is the number of spikes and represent the phases of spikes j and k, respectively. The function calculates the dot product between two unit vectors. It can be expressed as follows:

| (3) |

PPC values were averaged in the FAF and AC, and paired statistical comparisons were made to evaluate whether significant differences in spike phase consistency existed between regions (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, α = 0.05).

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using scipy (version 1.9.1) or custom-written Python scripts. For determining significant deviations from a 1/f fitted trend in the LFP spectra, one-sample t tests were performed. Statistical comparisons of median and CV values across regions (and within regions) were performed using paired statistics (Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, α = 0.05), as recordings in the FAF and AC were performed simultaneously (N = 29). Comparisons of spike–spike and spike–LFP correlation (PPC values) were also made using paired statistics. Comparisons of burst lengths were made by means of nonpaired statistics (Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, α = 0.05). All tests were corrected for multiple comparisons using the false discovery rate when appropriate [Benjamini and Hochberg procedure (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995)]; it is noted in the main text whenever this correction was applied.

Results

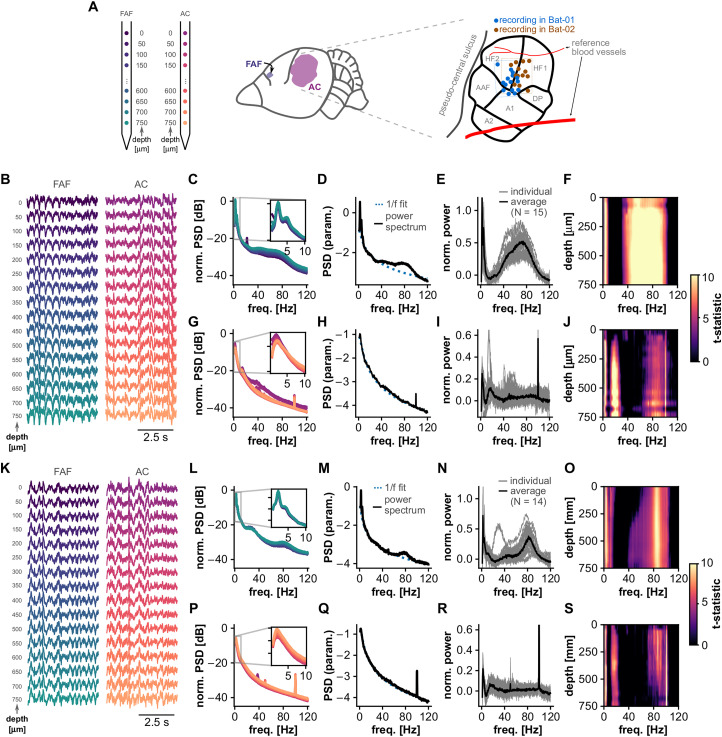

Spectral properties of frontal and auditory cortical LFPs

A total of 29 paired recordings (i.e., simultaneous electrophysiological acquisition from each region) in the FAF and AC were performed in two bats: Bat-01 and Bat-02 (N = 15 and N = 14 paired FAF–AC recordings, respectively). A schematic representation of the laminar probes, channel depths, and recording locations in the AC is given in Figure 1A. Since a clear map of the FAF does not exist, it was not possible to map electrode locations in the frontal structure in a similar manner. Example frontal and auditory cortical LFP traces from both animals are given in Figure 1, B and K, across all recording depths. Typically, LFPs exhibited clear rhythmicity in low and high frequencies in both cortical regions. Evidence for rhythmic activity was clear in grand-average spectra obtained from all ∼20-min-long LFP traces (Fig. 1C,G,L,M). Observable “bumps” in these spectra are interpretable as deviations from a 1/f power-law [a property of aperiodic mesoscopic signals such as LFPs (Baranauskas et al., 2012)] and therefore suggest the presence of oscillatory activity. We performed spectral parametrization by fitting 1/f curves to the power spectral density of every LFP signal recorded (Donoghue et al., 2020) in order to confirm that such spectral bumps were in fact significant deviations from an aperiodic spectrum. Representative parametrized spectra are depicted in Figure 1, D, H, M, and Q, corresponding to the full ∼20 min LFP traces from which data in Figure 1, B and K, were selected. The 1/f fit is shown in blue dashed lines. Deviations in the spectra from the power-law trend were clear in both animals, particularly in the FAF. We tested whether such deviations were consistently present in all recordings by normalizing the power spectrum of each LFP trace (N = 15 in Bat-01, N = 14 in Bat-02, per channel) to their fitted 1/f function (Fig. 1E,I,N,R). Power spectral values would hover ∼0 in the absence of consistent deviations but would be significantly above zero otherwise. Normalized spectral values were significantly above 0 in the FAF and AC for both animals (FDR-corrected one-sample t tests; pcorr < 1.73 × 10−4, t > 2.25) at relatively low (∼1–5 Hz in the FAF and AC), intermediate (∼12–27 Hz in the AC), and relatively high (ranging from ∼32 to 105 Hz but peaking at 70–85 Hz in the FAF and AC) frequencies (Fig. 1F,J,O,S).

Figure 1.

Spectral properties of LFPs in the FAF and AC. A, Left: schematic representation of the probes used for recordings in the FAF and AC. Depth and channel colors correspond to those in panels B and K. Middle: location of the FAF and AC in C. Perspicillata's cortex. Right: schematic representation of recording locations in the AC, color-coded by animal (blue, Bat-01, N = 15; brown, Bat-02, N = 14). The precise location of one recording in Bat-02 could not be recovered. B, Cortical LFPs (5 s excerpts) recorded simultaneously from the FAF (left) and AC (right; note that channel depths are color-coded) of Bat-01. C, Average power spectra in the FAF across all recordings (N = 15) in Bat-01 using full LFP traces (lengths of ∼20 min), for all channels. The spectrum of each channel is color-coded according to the depth scheme of panels A and B. D, Parametrization of an exemplary power spectrum obtained from ∼20 min LFP recordings in the FAF (depth, 700 µm). LFP traces originate from the same recording shown in B. The 1/f fit is depicted as a blue dashed line; power spectrum shown in solid black. E, Normalized power spectra (to 1/f activity) across all recordings in Bat-01, shown for channels located at 700 µm in the FAF. The solid black line indicates average (N = 15). F, We tested whether the normalized power spectrum was significantly larger than 0 (FDR-corrected t test, pcorr < 0.05) across depths and frequencies. The t-statistics are summarized here; values were set to 0 if the normalized power spectrum was not significant (i.e., pcorr ≥ 0.05). G–J, Similar to panels C–F, but the data shown corresponds to channels located in the AC. K–S, Similar to panels B–J but with data recorded from Bat-02.

In bats such as C. perspicillata (the animal studied here), LFP activity in low and high frequencies is related to vocal production (e.g., at frequencies delta, 1–4 Hz; beta, 12–30 Hz; and gamma, 60–120 Hz; Weineck et al., 2020; Garcia-Rosales et al., 2022b). Considering the above and the patterns of deviations from a pure 1/f signal shown in Figure 1, in subsequent analyses, we focused on frequency bands delta (1–4 Hz) and gamma (65–85 Hz). β-band frequencies were not included because no clear peaks in this range were detected in FAF signals (Fig. 1F,J,O,S).

Cycle-by-cycle analysis of oscillatory activity in frontal and auditory cortices

To study the characteristics of delta- and gamma-band rhythmic activity in frontal and auditory areas, we performed a cycle-by-cycle analysis of the recorded LFP. Cycles were considered only if they were part of consistent oscillatory activity (i.e., they were associated with putative oscillatory bursts). Bursts of oscillatory activity were detected using the bycycle algorithm (Cole and Voytek, 2019), which capitalizes on a time domain approach for quantifying waveform shape (Fig. 2A). A burst is detected based on four parameters, which control for SNR and waveform consistency (see Materials and Methods). In this context, an oscillatory burst occurs if the threshold values of these parameters are exceeded for at least 3 consecutive cycles.

Representative burst events in delta and gamma bands are shown for the FAF and AC in Figure 2B. The waveform shape of oscillatory activity was quantified by measuring three main features on a cycle-by-cycle basis: cycle period, cycle rise–decay asymmetry, and cycle peak–trough asymmetry (Fig. 2C; Cole and Voytek, 2019). For each LFP trace, the median feature value across all detected cycles was considered the waveform shape feature for that trace (Fig. 2D). The median summarizes a distribution of feature values, yielding one value per LFP trace (i.e., 29 values for each FAF and AC channel). The median feature value of asymmetry metrics was normalized to 0.5 to account for possible confounds related to signal polarity differences in the FAF and AC (see Materials and Methods; Schaworonkow and Voytek, 2021). To determine how and to what extent oscillatory waveform shape differed between recording locations, we performed systematic channel-by-channel pairwise comparisons. Only values obtained from simultaneously recorded LFP traces were compared with one another by using paired statistical testing. Median values for each ∼20 min LFP were quantified from hundreds of cycles. That is, for Bat-01, no less than 665 and 370 delta-band cycles were used from FAF and AC, respectively, while no less than 829 and 146 gamma-band cycles were used from the same regions. For Bat-02, at least 561 and 468 delta-band cycles were used from FAF and AC, while at least 717 and 241 gamma-band cycles were used from the same areas.

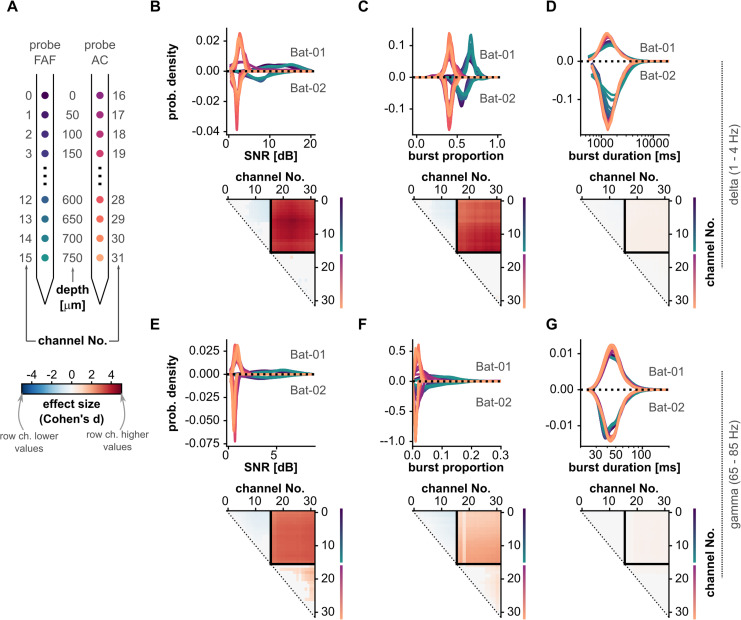

Bursting dynamics in frontal and auditory cortices

The data shown in Figure 1 suggest that the SNR of oscillatory activity in delta and gamma bands is higher in the FAF than that in the AC. We quantified SNR independently for each bat in frontal and auditory regions on a channel-by-channel basis (N = 15 observations for each channel in the FAF or AC for Bat-01 and N = 14 for Bat-02). The distribution of SNR values is shown in Figure 3B (top) for delta frequencies and in Figure 3E (top) for gamma frequencies. Distributions from Bat-01 are shown with positive probability densities, whereas data from Bat-02 are given with negative probability densities merely for illustrative purposes. Note that the color of each distribution corresponds to a specific channel in the shank, located at a certain cortical depth (Fig. 3A). Given that the patterns across animals were highly consistent, we compared SNR values across recording sites by pooling data from the two bats. Channel-by-channel statistical comparisons revealed significant differences in SNR across recording sites (FDR-corrected Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, N = 29, significance when pcorr < 0.05). Comparisons are summarized in the matrices of Figure 3B–G (bottom). A comparison matrix represents the effect sizes (d) of pairwise comparisons of SNR values across channels (d < 0.5 small, 0.5 ≤ d ≤ 0.8 medium, d > 0.8 large effect sizes; Cohen, 2013). A cell (r, c) in a matrix shows the effect size of comparing SNRs from a channel indexed by row r and a channel indexed by column c (i.e., channel r vs channel c). The relationship between a channel index and its relative depth in the frontal or AC is schematized in Figure 3A (notice the vertical lines next to channel numbers in Fig. 3B–G indicating cortical depths by following the color schemes of Figs. 1, 3A). The upper-right quadrant of each matrix represents comparisons of channels in the FAF versus those in the AC. Only effect size values of significant comparisons (pcorr < 0.05) were shown; they were set to 0 otherwise. The matrices in Figure 3, B and E, show strong differences in SNR between frontal and auditory cortices in the delta and gamma bands.

Figure 3.

Bursting dynamics and SNR in frontal and auditory cortices. A, Schematic illustrating the relationship of region and cortical depth with the channel number markers of panels B–G. Notice that depths are color-coded as in Figure 1. B, Top: distribution of SNR shown for each channel (notice the color schemes in panel A for the region and depth of each channel), across all recordings (N = 29 in the FAF and AC). Values for Bat-01 are shown with densities >0; values for Bat-02 are shown with densities <0 only for illustrative purposes. Bottom: effect sizes of channel-by-channel, pairwise statistical comparisons of SNR values (FDR-corrected Wilcoxon signed-rank tests). Effect sizes for comparisons that did not yield significance (i.e., pcorr ≥ 0.05) were set to 0. A cell (r, c) in the effect size matrix indicates the effect size of the comparison between burst proportion values in channel r and channel c (as per panel A). The quadrant spanning rows (0–15) and columns (16–31) illustrate the effect sizes of comparisons between channels in the FAF and AC. In this quadrant, red colors indicate higher SNR values in the FAF. C, Similar to panel B, but data shown correspond to burst proportions across recordings. D, Similar to panel C, but data shown correspond to burst durations (note the logarithmic scale of the x-axis).

Typically, SNR values are interpreted solely on the basis of signal amplitude. However, high SNRs derived from the spectral properties of a signal could also indicate, beyond amplitude, a relatively high proportion of oscillatory events. We calculated the bursting proportion as the ratio of the total time of bursting in an LFP trace relative to the total duration of that trace. The distribution of bursting proportions is given for both animals in Figure 3C (top) for delta frequencies and in Figure 3F (top) for gamma frequencies. From these data, it appeared clear that, in both animals, the proportion of bursting events in the FAF was higher than that in the AC. Given this consistency, we pooled data across bats and compared on channel-by-channel basis bursting proportions across sites (FDR-corrected Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, N = 29, significance when pcorr < 0.05). These comparisons, summarized in the matrices of Figure 3C (bottom) and Figure 3F (bottom), corroborate that the proportion of delta- and gamma-band oscillatory events was significantly higher in the FAF than that in the AC, with large effect sizes.

A higher proportion of bursting events could be influenced by two factors: more bursts occur in the FAF than in the AC, or bursts in the FAF are longer than those in the AC (or both). To elucidate this, we examined the distributions of burst durations in delta- and gamma-band LFP traces from all channels. The distribution of burst durations is given independently for each animal in Figure 3D (top) for delta and Figure 3G (top) for gamma frequencies. To statistically compare burst durations, we pooled data across bats given the highly similar patterns observed from the two animals. For comparisons, all bursts from any given channel are considered, so the number of bursts per channel was not always the same (at least 2,283 and 1,977 bursts were used for delta frequencies from Bat-01 and Bat-02, respectively; in gamma, no less than 2,984 and 1,991 for each bat). Because of the uneven burst counts, channel-by-channel comparisons were not paired (FDR-corrected Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, N ≥ 1,991, significance when pcorr < 0.05). As readily visible from the distributions of burst duration and as shown in the comparison matrices from Figure 3D (bottom) and Figure 3G (top), differences in burst durations between the FAF and AC were statistically negligible, indicating that bursts in the FAF were more numerous, but not necessarily longer, than in the AC. This corresponds well with our initial observation of a very large burst density in frontal regions.

The data shown in Figures 1 and 3 demonstrate that spectral and bursting dynamics were highly consistent between Bat-01 and Bat02. Because of this consistency between animals (Figs. 1, 3), data from the two bats were pooled in subsequent analyses.

Bursting events in the FAF and AC are temporally correlated

Transfer entropy analyses based on the phase of ongoing LFP activity, and direct electrical microstimulation of the frontal cortex to alter AC responsiveness, show that neural activity in the FAF can significantly modulate its auditory cortical counterpart (Garcia-Rosales et al., 2022b). Given the functional and anatomical connections in the FAF–AC network, we sought to determine whether oscillatory bursts in one region are related to bursts occurring in the other. We reasoned that co-occurring bursts across brain structures could be a fingerprint of functional connectivity complementary to phase correlations (e.g., coherence), statistical dependencies (e.g., transfer entropy), or invasive approaches (e.g., electrical microstimulation). We calculated the burst co-occurrence index (Fig. 4), a metric that quantifies for any given channel the relationship between the onset of its own bursts with the occurrence of bursts in other channels (Fig. 4A illustrates how the index was computed). The burst co-occurrence index is shown in Figure 4, B and C, calculated for eight channels in total, four in each region, at representative depths of 50, 250, 450, and 700 µm. Since the index is a cumulative count Z-normalized according to bootstrap distributions (see Materials and Methods), we could use it to evaluate the significance of burst co-occurrence across channels. Thus, the red colors in Figure 4 indicate significant, temporally correlated increases in bursting activity in other channels (Z-values ≥ 6), while the blue colors indicate significant, temporally correlated suppression of bursting activity in other channels (Z-values ≤ −6). The white colors indicate no significant deviations from baseline values.

At delta frequencies (Fig. 4B), a burst onset in either FAF or AC was typically preceded by a suppression of bursting activity in channels of the same structure and succeeded by a within-structure increase in burst co-occurrence across channels, peaking as trivially expected in the channel from which burst onsets were chosen. A similar pattern was observable for bursts detected in the gamma-frequency range (Fig. 4C). However, we observed no clear preonset suppression in the gamma band, potentially due to much shorter durations of gamma bursts compared with delta ones. In gamma frequencies, an interesting pattern was evident: When burst onsets were taken from FAF channels (Fig. 4C, top left quadrant), a periodicity of burst co-occurrence emerged in the frontal area, with a temporal scale of ∼250 ms. This phenomenon constitutes evidence for strong coupling between gamma-band activity and low-frequency (delta) rhythms. These data resonate with that of a second study (and a different dataset) demonstrating clear coupling between the amplitude of gamma-band and the phase of delta-band LFPs in the FAF of C. perspicillata (Garcia-Rosales et al., 2022a).

Remarkably, when a burst onset occurred in frontal or AC, significant and consistent changes in burst co-occurrence in the other region happened for gamma-band LFPs (Fig. 4C). That is, bursts onsets in the FAF were consistently and significantly correlated with gamma-band bursting in the AC and vice versa. Furthermore, Figure 4C suggests a degree of spatial specificity to this relationship, wherein bursts originating in the FAF appear more strongly related to those in the middle layers of the AC (depths of 250–450 µm), while bursts originating in the middle layers of the AC yield larger coactivation patterns in the FAF. Significant interareal burst co-occurrence was not equally clear in delta frequencies (Fig. 4B), although clear FAF–AC interactions occur in the delta band when considering transfer entropy analysis or even electrical stimulation experiments (Garcia-Rosales et al., 2022b). The apparent lack of burst interactions in the delta band is shown in Figure 4B; however, it does not necessarily mean the absence of burst co-occurrence in these frequencies. Rather, this effect is a consequence of the stringency of the bootstrapping procedure (see Materials and Methods) interacting with the ubiquity of bursting activity in the FAF (Fig. 3). That is, bootstrap distributions were contaminated with real bursting activity when accumulating burst counts from the frontal cortex. Taken together, these results (particularly the ones related to gamma-band LFPs) suggest an intrinsic relationship between elevated bursting activity in frontal and auditory cortices, supporting the notion of strong functional connectivity in the FAF–AC network.

Oscillatory waveform shape differences between frontal auditory cortices

We have shown the presence of oscillatory activity in delta and gamma frequencies in the frontal and auditory cortices of C. perspicillata. Oscillatory bursts across structures occur more often in the FAF, but are not necessarily longer than those in the AC. Remarkably, bursts in the FAF and AC are temporally correlated, supporting the notion of concerted activity in the delta and gamma ranges in the FAF–AC circuit. Such correlated bursting activity occurs in very similar frequencies, yet they occur in functionally and anatomically distinct areas of the brain. Do these oscillations differ across structures?

A visual inspection of ongoing LFP activity revealed that the oscillatory waveform in the FAF was highly asymmetric (i.e., less sinusoidal, with more pronounced troughs), something that was not so obvious in the AC (see, e.g., the representative bursts in Fig. 2B). The waveform shape of an oscillation was characterized by three main features (see above): period, rise–decay asymmetry, and peak–trough asymmetry. The distribution of feature values across recordings is given in Figure 5B–D (top) for delta frequencies and in Figure 3E–G (top) for gamma frequencies for all channels (Fig. 5A; conventions are the same used for presenting data in Fig. 3). Note that the median feature value across all cycles is considered the feature value for a given LFP trace (Fig. 2D), thus yielding 29 feature values for each electrode either in the FAF or AC (i.e., one value per recording). This allowed us to compare recording sites using paired statistics, capitalizing on the fact that data in the FAF and AC were simultaneously acquired.

Channel-by-channel comparisons revealed significant differences across cortical regions (FDR-corrected Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, significance when pcorr < 0.05). These analyses are summarized in the comparison matrices of Figure 5B–G (bottom; conventions are the same as those of Fig. 3). Delta-band oscillations in frontal and auditory cortices differed in period typically with small-to-medium effect sizes (d ≤ 0.8; Fig. 5B, bottom) but were strongly different in terms of their temporal asymmetries (Fig. 5C,D, bottom; d > 0.8 particularly for peak–trough asymmetries). The data in Figure 5 corroborates that the differences visible in Figure 2B were consistent across recordings. Regarding gamma-band LFPs, the period of gamma-band cycles in the FAF and AC differed more markedly than that of delta-band cycles (Fig. 3E, bottom; d > 0.8), although gamma-band oscillations differed only negligibly in their asymmetry across structures.

Waveform shape variability is higher in the AC than that in the frontal cortex

By examining recordings independently, we observed that beyond direct differences in waveform shape features (or lack thereof), feature values across cycles were typically less variable in the FAF than those in the AC. That is, the distribution of feature values (e.g., period) was typically narrower for LFPs recorded in the frontal cortex. To evaluate the extent of this effect, we quantified for each LFP trace the variability of waveform shape features as the CV (Fig. 2D) and compared it across recording sites. The CV is a measure of dispersion, in the sense that it measures the “broadness” of a distribution. Thus, larger CVs indicate that cycle features vary over a wider range of possible values, suggesting a higher variability in the oscillatory processes. As with the median, the CV summarizes a distribution, yielding one value per LFP trace (see above; Fig. 2D). The same cycles used to calculate median feature values were used to calculate CV values.

The distributions of CV values across cycle features for each channel are given in Figure 6B–D (top) for delta frequencies and Figure 6E–G (top) for gamma frequencies. CV values appeared consistently lower for channels in the FAF than for those in the AC. This trend was confirmed by statistical, channel-by-channel pairwise comparisons (FDR-corrected Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, N = 29, significance when pcorr < 0.05), summarized in comparison matrices similar to those of Figure 3. Statistical comparisons between channels located in different regions (the upper-right quadrants of the comparison matrices) yielded the highest effect sizes (typically d > 0.8, large). CV values were consistently and significantly lower in the FAF channels than those in AC channels, in delta- and gamma-frequency bands, for all cycle features. Some significant within-area differences also occurred (e.g., deeper channels in the FAF had higher CV values than more superficial ones), yet effect sizes were typically medium (0.5 < d < 0.8) or small (d < 0.5). Overall, these results indicate that, beyond first-order differences in waveform shape, oscillatory activity in the frontal cortex exhibits a higher degree of cycle-by-cycle regularity (i.e., lower variability over cycles) than that of the AC. Note that such differences in regularity between regions are unlikely to arise from differences in the bursting proportions across FAF and AC (Fig. 3). Although more bursts result in more cycles contributing to a distribution, cycle-by-cycle regularity is quantified here using hundreds (sometimes thousands) of cycles obtained from relatively long LFP traces (∼20 min). These are well-sampled distributions whose CV should not be strongly affected by increasing the number of waveform shape features in them.

Differences across regions are robust against burst detection parameters

The data indicate that oscillations in the FAF are more regular than those in the AC. However, the measurements of waveform shape used here can be affected by the SNR of the oscillatory activity used to quantify them. In particular, higher SNR of oscillatory activity in the FAF (Fig. 3B) could result in narrower distributions of cycle features, because low SNR increases the variability of waveform shape features (Schaworonkow and Nikulin, 2019). The SNR for burst detection is controlled by the parameter amplitude fraction threshold, which discards cycles below a certain amplitude percentile calculated from all cycles in an LFP trace (Cole and Voytek, 2019; Schaworonkow and Voytek, 2021). Therefore, to test whether the results shown above can be simply accounted for by different SNR levels in the FAF and AC, we evaluated the sensitivity of the interareal differences to different values of amplitude fraction threshold in each region (Fig. 7).

The median effect size of interareal comparisons was used as a summary metric of differences in median feature values (Fig. 7A,B) and CV values (Fig. 7C,D) across cortical regions. This metric corresponds to the median value of the upper-right quadrant of the comparison matrices in Figures 5 and 6. We systematically varied the amplitude fraction threshold parameter (range, 0.1–0.9, step of 0.1) used to detect oscillatory bursts independently in the FAF or the AC, and for each iteration, we calculated the median effect size of interareal comparisons. As depicted in Figure 7A, period values for delta-band cycles were different between the FAF and AC with typically medium or even low effect sizes (d < 0.5 for low, 0.5 ≤ d < 0.8 for medium), while asymmetries differed with typically strong effect sizes (d > 0.8) particularly when considering the peak–trough asymmetry as in Figure 5. In general, observations across a broad range of threshold values conformed well to the data depicted in Figure 5 in delta and gamma bands (Fig. 7B for gamma). Those data were obtained with a threshold value of 0.5 (Fig. 7, red squares). Similarly, CVs were consistently lower in the FAF than those in the AC across a wide range of amplitude fraction threshold values in both delta and gamma frequencies (Fig. 7C, delta; Fig. 7D, gamma), for all three cycle features considered. These data were highly consistent with those shown in Figure 6. These results indicate that the differences in waveform shape features and their CV values between frontal and auditory cortices are not trivially accounted for by differences in SNR across regions.

A conceptual model captures patterns of waveform shape differences between the FAF and AC

We hypothesized that differences across areas, particularly when considering the CV of waveform features, might reflect the activity of two distinct cortical generators exhibiting different degrees of regularity. We illustrate this idea with a conceptual model in which an oscillation occurs as a consequence of the temporally aligned rhythmic discharge of a population of neurons. This conceptualization makes no assumption on the nature of the neuronal oscillators themselves (see Discussion); instead, it only assumes that extracellular oscillatory activity occurs when a sufficiently large neuronal population fires concertedly (Buzsaki et al., 2012). We reasoned that a highly synchronous population firing would lead to a strong current at a specific phase of the LFP resulting in relatively asymmetric waveform shapes; in contrast, a relatively asynchronous population activity would yield less asymmetric temporal features. We simulated 30 neurons firing rhythmically for 300 s at a delta rate (3 Hz, for illustrative purposes; this can be generalized to other frequencies as well), with varying degrees of synchronicity among them. The synchronization of the spiking across neurons was manipulated by changing the duty cycle of a square pulse train determining the instantaneous rate of an inhomogeneous Poisson process controlling a neuron's firing rate (see Material and Methods). Lower duty cycles represent narrower spiking windows and therefore higher synchronicity across neurons. From the neuronal firing in each condition, we generated a synthetic LFP by convoluting each spike train with a synaptic kernel and adding them over all neurons (Fig. 8A). This synthetic LFP was used to estimate cycle features computed with the bycycle algorithm, analog to the analyses performed on the empirical data.

Simulated spiking activity with various degrees of synchronicity (controlled by the duty cycle parameter) is shown in Figure 8B together with corresponding LFPs. Figure 8C–E shows the distribution of cycle features (Fig. 8C, period; Fig. 8D, rise–decay asymmetry; Fig. 8E, peak–trough asymmetry) for each duty cycle condition. We did not observe changes in the median period across duty cycles. However, we did observe a consistent change in temporal asymmetries (Fig. 8D,E) indicating that a more synchronous neuronal population (lower duty cycles in the figure) resulted in more asymmetric waveform shapes. Note that the farther the median feature value is from 0.5 (Fig. 8D,E, black line), the more asymmetric LFP cycles are. In addition, we observed that as the neuronal population became less synchronized (i.e., higher duty cycles) feature values became more variable, as illustrated by the fact that the CV obtained from the feature distributions tended to increase together with the duty cycle (Fig. 8G–H). These two cases (higher asymmetry for more synchronized population spiking and more variability for less synchronized spiking) reflect differences in delta- and gamma-band oscillations in the FAF and AC (i.e., higher asymmetry and less variability for oscillations in the FAF) and offer a simple yet plausible account of the patterns observed across regions.

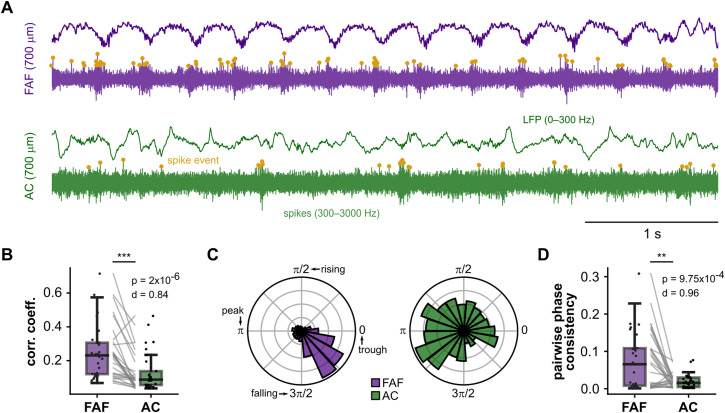

These results suggest that differences in FAF and AC waveform shape can at least be partially accounted for by different degrees of synchronicity in the underlying neuronal firing. To test this prediction, we turned to the spiking activity in frontal and auditory regions (Fig. 9A). Since oscillations were more asymmetric and less variable in the FAF, we hypothesized that neuronal spiking would be more highly correlated in frontal than in auditory cortex and, additionally, more strongly synchronized with LFP oscillations (a secondary consequence of the model in Fig. 8). For each recording, we averaged correlation coefficients obtained from FAF and AC channels and tested whether their values were significantly different across regions. These analyses corroborated that spike train correlations were higher in frontal regions (Fig. 9B, bottom; Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 2 × 10−6) with a large effect size (d = 0.84).

Figure 9.

Spiking activity in the FAF is more correlated and more strongly synchronized to delta-band oscillatory bursts. A, Representative LFP (top) and spiking (bottom) activity from FAF (purple) and AC (green) electrodes at depths of 700 µm. B, Spike–spike correlation coefficients for each recording in the FAF and AC (N = 29; averaged across channels); spike–spike correlation in the FAF was significantly larger than in the AC (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 2 × 10−6, d = 0.84, large effect size). C, Distribution of spike phases relative to delta LFPs in the FAF (left, N = 6,760 spikes) and AC (right, N = 661 spikes). Spikes were only those occurring during bursts of delta-band activity as detected by the bycycle algorithm. Troughs, peaks, and rising and falling phases, for any given cycle, are indicated in the figure. D, Average PPC values in the FAF and AC were compared across all recordings (N = 29). There was significantly larger spike phase consistency in the FAF than in the AC (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 9.75 × 10−4, d = 0.96, large effect size).

Because delta-band oscillations exhibited the largest differences in terms of asymmetry (Fig. 5), we studied spike–LFP relationships in this frequency range. Here, only spikes occurring within oscillatory bursts, as detected by the bycycle algorithm, were considered (note that these are the same bursts used in previous analyses). Spike times were expressed as the points of spike occurrence relative to the period of the burst cycle in which they occurred (0, spike occurs at beginning of the cycle; 1, spike occurs at end of cycle), and spike phases were obtained by multiplying the relative spike timing by 2π. The distribution of spike phases from the recordings shown in Figure 9A is depicted in Figure 9C (N = 6,760 spikes in the FAF, N = 661 spikes in the AC), suggesting a tighter clustering of spike phases in the FAF. The PPC (Vinck et al., 2010) was computed for all channels across recordings. The PPC measures how tightly spike phases group together (phase consistency) and constitutes a bias-free equivalent to the square of the phase locking value. Higher PPC values indicate higher spike–LFP coherence. To test whether spikes in the FAF were more strongly synchronized to delta-band LFPs than those in the AC, we averaged PPC values across channels in the FAF and AC (as described above) and statistically compared across regions. PPC values were significantly higher in the FAF than in the AC (Figure 9D, bottom; Wilcoxon signed-rank test, p = 9.75 × 10−4) with a large effect size (d = 0.96).

Altogether, these results show that differences in waveform asymmetries between the FAF and AC in delta frequencies are accompanied by differences in spike correlations and spike–LFP synchronization between regions. These observations are in line with predictions derived from the conceptual model illustrated in Figure 8 and support a relationship between waveform shape and spike synchronization. Direct correlations between, for example, peak–trough asymmetry and spike train correlations were, although significant, relatively weak (FAF, p = 0.033, adjusted R2 = 0.13; AC, p = 0.009, adjusted R2 = 0.2), indicating that oscillatory waveform shape cannot be trivially explained by local spike synchronization alone.

Discussion

In this work, oscillations in the bat frontal and auditory cortices were studied with respect to their waveform shape. We show that oscillations present in simultaneously recorded LFPs in the fronto-auditory circuit differ markedly in waveform shape and in the variability of waveform features across individual cycles. This heterogeneity is not trivially accounted for by different levels of SNR in frontal and auditory regions. A conceptual model suggests a relationship between the temporal organization of neuronal spiking and waveform shape asymmetry, with higher spike temporal correlations leading to more asymmetric waveforms. In line with the predictions of the model, we demonstrate that spike–spike and spike–LFP correlations differ significantly in the FAF–AC network.

The bat frontal and auditory cortices are two brain regions with distinct cytoarchitectonic patterns, which likely account for the differences observed in oscillatory waveform shape across areas. C. perspicillata's AC is a primary sensory region with a well-defined, six-layered columnar structure and clear interlaminar boundaries [see Garcia-Rosales et al. (2019) for histology], following a blueprint that is typical across mammalian species (Mountcastle, 1997; Linden and Schreiner, 2003; Douglas and Martin, 2004). In contrast, C. perspicillata's FAF lacks clear boundaries between layers (Weineck et al., 2020; Garcia-Rosales et al., 2022b), mirroring instead the stereotypical agranular or slightly agranular architecture of the mammalian frontal cortex (Camarda and Bonavita, 1985; Shepherd, 2009; Beul and Hilgetag, 2014). Differences between the bat frontal and auditory regions likely extend to other cytoarchitectonic properties such as the distribution of cell-type density and overall cellular organization. Beyond anatomy, cortical cytoarchitecture plays a significant role in defining activity patterns and brain function. Indeed, the functional characteristics of a given region are well-related to its cytoarchitecture (Pandya and Yeterian, 1996; Badre and D'Esposito, 2009), which includes the nature of incoming and outgoing axonal connections (Kritzer et al., 1992; Passingham et al., 2002; Hilgetag et al., 2019), cell-type specific characteristics (e.g., density, morphology; Benavides-Piccione et al., 2002; Beul and Hilgetag, 2014), and laminar organization (Hooks et al., 2011). Local cytoarchitecture affects neuronal firing patterns, which are known to vary consistently across functionally and anatomically well-defined regions (Badre and D'Esposito, 2009; Shinomoto et al., 2009; Mochizuki et al., 2016). Anatomical differences between granular and agranular cortical areas also result in distinct intra- and interlaminar connectivity patterns (Shepherd, 2009; Beul and Hilgetag, 2014), which may also affect the dynamics of the generators of cortical oscillatory activity. Together, local anatomy, spiking patterns, and connectivity influence mesoscopic measurements of activity such as LFPs or other signals recorded noninvasively (Buzsaki et al., 2012; Cole and Voytek, 2017).

Other than local cytoarchitecture, respiration can also affect both single-neuron and oscillatory activities (Tort et al., 2018). For example, respiratory rhythms in mice entrain single-neuron spiking and local cortical oscillations particularly—but not only—in frontal regions (Koszeghy et al., 2018; Tort et al., 2018) with measurable functional consequences (Bagur et al., 2021; Folschweiller and Sauer, 2023). Likewise, heart rate fluctuations are known to correlate with brain oscillations, particularly during sleep (Mara and Julian, 2018; Mikutta et al., 2022). Respiratory or cardiac rhythms were not measured in this study, but their potential effects cannot be directly ruled out given that typical values for C. perspicillata lie close to delta frequencies: respiration rate, ∼2.5–4.5 Hz, and heart rate, ∼8.33 Hz. For example, it is possible that respiration influences the patterns of rhythmicity and asymmetry overserved in frontal areas by directly modulating the LFP, synchronizing neuronal spiking (thereby altering the LFPs), or a combination of both. Future studies should clarify the roles—if any—of respiration or heart rate in modifying oscillatory waveform shape dynamics.

Delta-band oscillations differed markedly across regions in terms of their temporal asymmetries, something that did not occur consistently for gamma-band activity (Fig. 5). However, for both frequency ranges, we observed large and consistent interareal differences in the variability of shape feature values across individual cycles (Fig. 6). A conceptual model (Fig. 8) suggests that temporal asymmetries (i.e., waveform shape features) and their variability across cycles could depend on the degree of correlated activity of the underlying neuronal population. The model in Figure 8 suggests that more synchronous populations yield highly asymmetric waveform shapes and lower cycle-by-cycle variability, while less synchronous populations yield gradually a more sinusoidal shape with more variable cycle-by-cycle features. That waveforms become less asymmetric can be explained by temporal averaging of the contribution of each spike to the LFP, akin to the expected effects of spatial averaging in electro- or magnetoencephalographic recordings (Schaworonkow and Nikulin, 2019). Note that the model does not make any assumptions about important features of the underlying generators, such as location in the local circuitry, connectivity patterns, or component cell types. As discussed above, these factors can influence both waveform shape and spiking dynamics. Instead, the model provides a parsimonious account of the empirical data shown in Figure 5, assuming only that spiking is an important contributor to the LFP (Buzsaki et al., 2012). The model in Figure 8, together with the waveform shape differences across regions, affords one prediction, namely, that spike–spike and spike–LFP correlations should be higher in the area with more asymmetric signals (i.e., the FAF). Our results in Figure 9 corroborate such prediction, illustrating that the bat frontal cortex exhibits more correlated spiking, which is also more strongly synchronized with the ongoing LFP phase in delta frequencies. As a concept, and supported by our data, the model draws a relationship between waveform shape asymmetry and the temporal dynamics of neuronal spiking in the neocortex.

A hypothesis stemming from the above observations is that differences in the variability of cycle features (measured by the CV) between the FAF and AC might be explained by different values of temporal correlations in the underlying generators. In other words, it could be speculated that putative generators in the FAF operate with tighter parameters (reflected in higher temporal correlations) than their AC counterparts. One possible take on the functional implications of such a phenomenon would be that frontal circuits rely more on internal timescales, while auditory circuits exhibit elevated flexibility and perturbability. Previous studies have demonstrated that activity patterns in the rodent prefrontal cortex exhibit less variability than those of sensory regions (Ruiz-Mejias et al., 2011; Castano-Prat et al., 2017), potentially reflecting a cortical hierarchy of excitability and circuit properties. In such a hierarchy, peripheral areas exhibit more adaptability to sensory stimuli (and therefore more variability), while frontal areas exhibit higher stimulus independence, yielding activity patterns better related to local network dynamics (Badre and D'Esposito, 2009; Braun and Mattia, 2010; Ruiz-Mejias et al., 2011). In the bat brain, the FAF appears to be a modulation and control structure that may also be involved in the integration of diverse inputs during echolocation and navigation, as reflected by its internal dynamics and by the anatomical and functional connectivity patterns with other cortical and subcortical regions (Kobler et al., 1987; Casseday et al., 1989; Eiermann and Esser, 2000; Kanwal et al., 2000; Weineck et al., 2020; Garcia-Rosales et al., 2022b). Conversely, the bat AC (similar to that of other mammals) is primarily tasked with representing sounds that may unfold in time over nested timescales, typically exhibiting varying degrees of periodicity which require higher adaptability and flexibility (Henry and Obleser, 2012; Lakatos et al., 2013; Teng et al., 2017; Garcia-Rosales et al., 2018; Doelling et al., 2019). Indeed, previous modeling work suggests that neuronal response patterns in the FAF and AC can be accounted for by slower synaptic dynamics in the frontal region (Lopez-Jury et al., 2020), something that could be detrimental to precise stimulus tracking but that could be important for sensory integration. From the above, we hypothesize that a higher level of variability in the auditory cortical circuitry (Fig. 6) might aid with efficient sensory representations in the AC (Pittman-Polletta et al., 2021), while narrower dynamics could be important for high-level computations in the FAF (e.g., sensory integration), closely tied to internal timescales and more robust against external perturbations.