Abstract

Purpose:

The aim of this qualitative study is to understand the need for, access to, and quality of rehabilitation services for people living with Long COVID. Little is known about the experiences of people living with Long COVID accessing rehabilitation services. Therefore, we explored health concerns leading people living with Long COVID to seek help to address functional concerns and their experiences with accessing and participating in rehabilitation.

Method:

Interpretive description guided exploration of participants’ experiences with Long COVID rehabilitation in Alberta, Canada. Semi-structured interviews were completed with 56 participants recruited from: three publicly funded Long COVID clinics, a specialized private physiotherapy clinic, a telephone-based rehabilitation advice line, and a Workers’ Compensation Board-funded Long COVID rehabilitation program. Recruitment through mass media coverage allowed us to include people who did not access rehabilitation services. Data analysis was informed by Braun and Clarke's reflexive thematic analysis.

Results:

Four themes were identified: (1) the burden of searching for guidance to address challenges with functioning and disability; (2) supportive relationships promote engagement in rehabilitation; (3) conditions for participation in safe rehabilitation; and (4) looking forward – provision of appropriate interventions at the right time.

Conclusions:

Our findings highlight the experiences of accessing rehabilitation services for people living with Long COVID. Results suggest approaches to Long COVID rehabilitation should be accessible, multi-disciplinary, flexible, and person-centred.

Key Words: COVID-19, health services, lived experience, post-COVID condition, rehabilitation

Résumé

Objectif :

étude qualitative pour comprendre les besoins en services de réadaptation des personnes qui vivent avec la COVID longue, l’accès à ces services et leur qualité. On sait peu de choses sur les expériences des personnes qui vivent avec la COVID longue et accèdent à des services de réadaptation. C’est pourquoi les auteurs ont exploré les inquiétudes qui incitent ces personnes à demander de l’aide pour répondre à leurs problèmes fonctionnels et les expériences qu’elles ont vécues en matière d’accès à la réadaptation et de participation aux services qui y sont associés.

Méthodologie :

exploration guidée de la description interprétative des expériences des participants qui suivent une réadaptation à cause de la COVID longue en Alberta, au Canada. Les chercheurs ont procédé à des entrevues semi-structurées auprès de 56 participants recrutés dans trois cliniques de COVID longue financées par le gouvernement, une clinique de physiothérapie spécialisée privée, une ligne téléphonique de conseils en réadaptation et un programme de réadaptation après la COVID longue remboursé par la commission des accidents de travail. Le recrutement dans les médias de masse a permis d’inclure des personnes qui n’avaient pas accédé aux services de réadaptation. L’examen des données reposait sur l’analyse thématique réflexive de Braun et Clarke.

Résultats :

les chercheurs ont relevé quatre thèmes : 1) le fardeau de la recherche de conseils pour répondre aux problèmes de fonctionnement et d’incapacité; 2) les relations de soutien qui favorisent la participation à la réadaptation; 3) les conditions nécessaires pour participer à une réadaptation sécuritaire et 4) pour l’avenir, la prestation d’interventions appropriées au bon moment.

Conclusions :

les constatations des auteurs font ressortir les expériences d’accès aux services de réadaptation chez les personnes qui vivent avec la COVID longue. Selon les résultats, les approches de réadaptation après la COVID longue devraient être accessibles, multidisciplinaires, flexibles et axées sur l’individu.

Mots-clés : affection post-COVID, COVID-19, expérience vécue, réadaptation, services de santé

Long COVID, also known as post COVID-19 condition, “occurs in individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS CoV-2 infection, usually 3 months from the onset of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Symptoms last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis.”1,2 Since January 2022, approximately 15% of Canadian adults who tested positive or presumed they had a COVID-19 infection have experienced symptoms lasting 3 months or more after infection.3

The patient-led acknowledgment of Long COVID stemmed from shared experiences of people having prolonged symptoms after COVID-19 infection that negatively impacted physical, cognitive, and mental health.4 The symptoms most commonly associated with Long COVID are fatigue, cough, shortness of breath, pain, and cognitive dysfunction (e.g., memory or attention challenges).3 Some people experience symptoms associated with other complex chronic post-infection illnesses, such as myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).5 These symptoms include autonomic dysfunction and post-exertional symptom exacerbation (PESE) (i.e., where symptoms worsen after engaging in previously tolerated amounts of activity), and can lead to disability.6–10 Although people experiencing severe symptoms during the acute phase of their infection are more likely to report prolonged or recurrent symptoms,3 any individual who contracts COVID-19 can develop Long COVID.1 Long COVID symptoms can be episodic and unpredictable, significantly impacting quality of life and an individual's ability to participate in meaningful life roles.11,12

Rehabilitation's primary focus on function and improving participation makes physiotherapists (PTs) and occupational therapists (OTs) well-suited to support people in managing the impact of Long COVID on day-to-day living.13 Rehabilitation professionals can provide safe and personalized interventions to address the impact of Long COVID symptoms on function, while considering the episodic and fluctuating nature of the condition. Safe rehabilitation approaches are critical, given the impact of Long COVID symptom exacerbation on daily function and quality of life.6 These approaches include avoiding acute events and flare-ups, facilitating clear and accurate expectations and being psychologically supportive to avoid stigma.6,8 Clinical guidelines identify core components of Long COVID rehabilitation, which include multidisciplinary teams, continuity and coordination of care, person-centred care, and shared decision making.14–16

In Alberta, Canada, Long COVID services were established within public,17,18 private,19 and Workers’ Compensation Board (WCB) health systems20 to reduce the impact of symptoms on functioning, disability, and health among people living with Long COVID. At the time, little evidence was available to guide clinical practice or referrals to rehabilitation services. There was, and continues to be, little known about the experiences of people with Long COVID regarding access to rehabilitation services.

The aim of this qualitative, exploratory study was to better understand the need for, access to, and quality of rehabilitation services for people living with Long COVID. We focused on the experiences of accessing rehabilitation services by exploring: (1) health concerns leading people with Long COVID to rehabilitation, (2) experiences with accessing and engaging in rehabilitation, and (3) whether rehabilitation services met (or did not meet) their disability-related needs.

Methods

Researchers’ positionality

Recognizing that there are diverse experiences of living with Long COVID, this study was guided by constructivist and interpretivist perspectives. In addition, advancements in Long COVID evidence from patient-led initiatives5 highlights the importance of using patient-oriented research approaches to inform clinical practice.21–23 Two people with lived experiences of Long COVID with professional backgrounds in physiotherapy and nursing were equal and active members on our study team, providing input and feedback throughout the study. They piloted the interview guide to ensure relevance and participated in interpretation of findings to ensure appropriate reporting of results. The research team was comprised of clinicians and researchers with diverse professional backgrounds in rehabilitation, public health, health services, nursing, pulmonology, and qualitative and quantitative methodologies. Intersectionality between patient partners, who were also clinicians, offered considerable insight and varied perspectives into how the research was conducted.

Study design

This study was conducted in Alberta, Canada. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Alberta's Health Research Ethics Board (Pro00110635). All participants provided informed consent.

Methodological approach

We used Interpretive Description (ID),24 a qualitative approach used to explore relationships and patterns of complex phenomena in applied settings.24–26 Knowledge is co-constructed by the researcher interpreting patient lived experiences in the context of disciplinary knowledge to generate meaningful insights that inform clinical practice.24,25

Conceptual framework

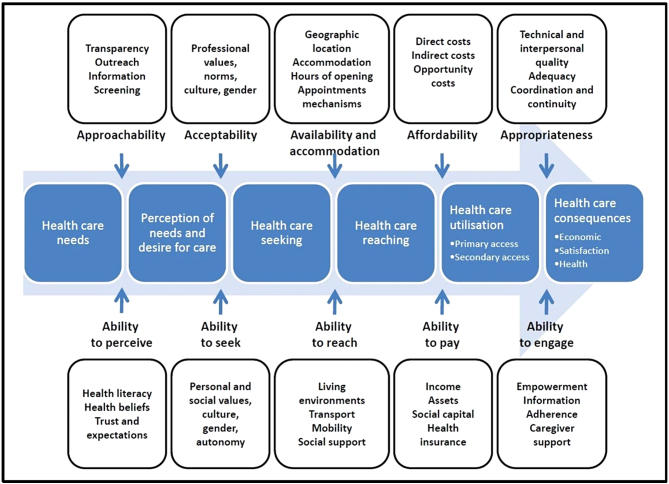

Levesque and colleagues’ “conceptual framework of access to health care” informed how we considered factors related to accessing rehabilitation while we developed the interview guide and during data analysis (refer to Figure 1).27 This multidimensional framework describes how dynamic interactions between patient abilities and aspects of the health system influence access to health care.27,28 Patient abilities are defined as the ability to: perceive, seek, reach, pay, and engage in health care services.27,28 Aspects of the health system include approachability, acceptability, availability and accommodation, affordability, and appropriateness.27

Figure 1.

A conceptual framework of access to healthcare.28

In our study, the patient-level aspects of the conceptual framework informed interview question development. During analysis, we considered definitions of health care access in relation to the participant experiences and the complexity of the phenomenon as we developed themes. This framework has been used in qualitative health services and rehabilitation research with diverse study populations.27–29

Study population

Participants were recruited from Alberta's publicly-funded telerehabilitation advice line,17 three publicly-funded physician-led Long COVID clinics,18 a specialized private PT clinic,19 and a multidisciplinary Long COVID clinic operated by WCB-Alberta.20 This study was conducted prior to the establishment of multi-disciplinary teams in Long COVID clinics in Alberta. Participants were also recruited through local media coverage (social media and radio) to learn from those who may have experienced barriers to accessing Long COVID rehabilitation. More details on the referral sources and the types of services offered when this study was conducted (late 2021/early 2022) are described in Table 1 in Appendix 1.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) people reporting ongoing symptoms at least 3 months after confirmed or presumed COVID-19 infection; (2) age 18+ years; (3) able to communicate in English; and (4) able to provide informed consent. Participants did not need to have a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test.

Recruitment

Purposive sampling towards maximum variation guided recruitment.30,31 The diversification criteria were age, gender, ethnicity, and geographical location (rural/urban) with the intent to recruit a diverse sample, knowing that Long COVID is present across multiple age groups, genders, and ethnicities.32 Geographic location was considered to reflect experiences representative of urban and rural settings since there are differences in available health services across Alberta. We did not monitor these diversification criteria during recruitment as we were reliant on clinicians at each site to identify a diverse group of participants. However, we asked participants about each of these criteria at the end of each interview to monitor them in case we needed to recruit participants with certain characteristics. We aimed to recruit 50–60 participants, considering the diversity of people living with Long COVID and the number of recruitment settings.24 This aligns with taking a practical approach to sample size determination in ID and reflexive thematic analysis, as described by Thorne and colleagues and Braun and Clarke.24,30,33,34 Knowing there is a wide array of experiences related to accessing Long COVID services, ID does not provide specific sample sizes to achieve theoretical or data saturation, but allows for researchers to determine how much data is required to provide reasonably comprehensive findings that are clinically meaningful.24

Staff liaisons considered the study inclusion/exclusion criteria when asking potential participants for their consent to share contact information with the research team. Eligible participants were then contacted by the study coordinator. We also recruited a convenience sample of individuals who contacted the investigators by email after seeing media coverage of the study.

Data generation

Data generation occurred between October 2021 and January 2022. One-on-one semi-structured interviews were completed by one experienced interviewer (KB) and one PhD-level trainee (PH) via videoconference software (Zoom35) or phone. Participants were offered the option to complete the interview over multiple sessions if necessary, and two chose this option. Participants were asked to describe their Long COVID experiences. Interview topics addressed health-related challenges impacting participation in daily activities, perceptions of rehabilitation needs and service quality, and experiences accessing rehabilitation services. Probing questions explored topics in greater depth. The full interview guide is provided in Appendix 2. Data generation and analysis occurred concurrently, enabling iterative refinements to the interview guide to generate more descriptive and relevant data.24

Participants were asked open-ended questions about their gender, cultural or ethnic background, and whether their place of residence was urban or rural in a conversational manner at the end of the interview. Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, reviewed for accuracy, and imported into NVivo data management software for analysis.36

Data analysis

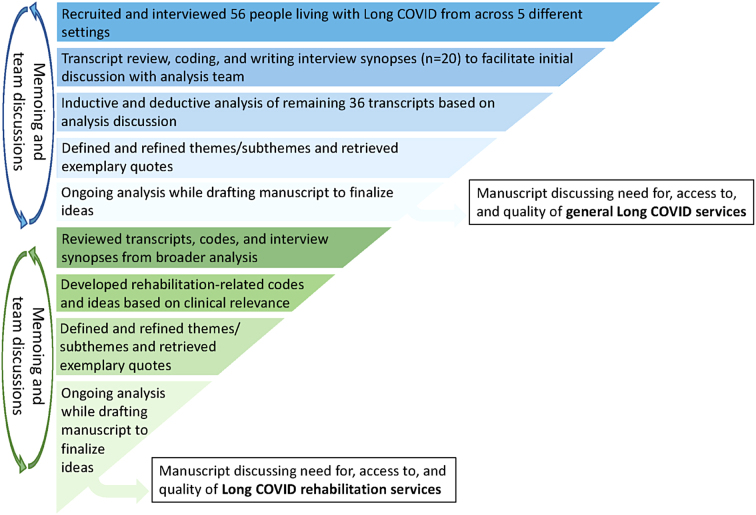

Participants shared rich descriptions of the broad scope of Long COVID health services37 and rehabilitation. Braun and Clarke's six phases of reflexive thematic analysis guided coding of all data related to perceptions and experiences of accessing Long COVID health services.38,39 Thematic analysis was supported by written interview synopses (i.e., 2–3-page overviews of participants’ interview responses) that facilitated team-based discussions and supported theme development, definition, and refinement.37,38,40 Refer to Figure 1 in Appendix 1 for further details about the analysis process. The findings related to participants’ experiences with access and perceptions of the quality of the broader scope of Long COVID health services are described elsewhere.37

Focusing on the rehabilitation-specific codes and themes, we used a relational approach, also informed by Braun and Clarke's six-steps of reflexive thematic analysis.38,39 PH (PhD Candidate and OT) reviewed the synopses and codebook to inductively generate initial codes and themes while considering practical relevance of the data to rehabilitation practitioners (e.g., PT, OT, mental health, kinesiologists, speech-language pathologists) and clinical practice. Frequent discussions occurred between KB (public health background), and MM, DG, and PH (rehabilitation and research backgrounds). They iteratively brainstormed, challenged, and critiqued interpretations of the data to refine themes focused on rehabilitation, which promoted credibility of interpretations and relevance to clinical practice. Memoing (i.e., analytic notes to help researchers conceptualize and refine emerging thoughts and patterns about the data during analysis) allowed for comparison of participants’ experiences across settings and interventions while supporting theme conceptualization, definition, and refinement.24 Confirmation of themes and identifying relevant quotes were achieved through comparison with the codebook during analysis and while writing the report.

Rigor

Rigor was maintained by keeping an audit trail of decision-making throughout the study.24 We asked open-ended questions to prioritize participants’ perspectives and experiences. Rich description and direct quotes from participants grounded our analysis in the data, supporting credibility.24 Analysis team discussions enabled consideration of team members’ subjectivities, promoted rich dialogue of diverse perspectives during analysis, supporting credibility in theme development. Reflexive journaling facilitated consideration of our perspectives and interpretations within the context of clinical practice.24

Results

Participants

We received contact information for 64 potential participants from all recruitment sites, and 56 participants were interviewed. We were unable to contact four people, three people agreed to participate but did not attend the interview, and one person declined to participate after having the study explained. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1, with additional details related to participants’ ethnicity in Table 2 in Appendix 1. Most participants identified as female (60.7%). Our sample ranged from 20 to 74 years of age with a mean (standard deviation) of 49.3 years (13.0). Twenty-one (37.5%) participants had pre-existing conditions, including asthma, multiple sclerosis, and diabetes. The majority (76.8%) were from urban areas. Participants reported diverse occupational backgrounds, including front-line positions (e.g., health care, education, trades) and non-front-line positions (e.g., home maker). Some were unemployed, retired, or did not discuss their employment status during the interview. Forty-five (80.4%) participants had accessed rehabilitation services. The remaining 11 participants (19.6%) that accessed minimal or no rehabilitation were recruited from media coverage about the study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants Living with Long COVID

| Participant characteristics | Total |

|---|---|

| Self-reported gender* | |

| Male | 22 |

| Female | 34 |

| Mean age | 49.3 y |

| Mean interview length | 52.6 min |

| Rural/Urban | |

| Rural | 13 |

| Urban | 43 |

| Self-reported ethnicity – See Appendix 1 – Table 2 for a comprehensive summary of the wide variety of reported ethnic backgrounds. | |

| Vaccination status | |

| Unvaccinated | 50 |

| One dose | 4 |

| Undisclosed | 2 |

| Alberta COVID-19 wave where participant was infected | |

| Wave 1 (March 2020–June 2020) | 12 |

| Wave 2 (July 2020–February 2021) | 33 |

| Wave 3 (March 2021–June 2021) | 10 |

| Wave 4 (July 2021–December 2021) | 1 |

| Recruitment site | |

| Public Long COVID clinics | 14 |

| BreatheWell Physiotherapy | 9 |

| Rehabilitation Advice Line | 8 |

| Workers’ Compensation Clinic | 14 |

| News Article Recruitment (accessed minimal to no rehabilitation) | 11 |

All participants were asked their gender as an open-ended question in conversation with the interviewer. All responded using sex-based categories of male/female. We are reporting terms that participants used.

Themes

Participants shared diverse experiences of accessing Long COVID rehabilitation services, characterized by the following themes: (1) the burden of searching for guidance to address challenges with functioning and disability; (2) supportive relationships promote engagement in rehabilitation; (3) conditions for participation in safe rehabilitation; and (4) looking forward – provision of appropriate interventions at the right time. The themes (italics) and sub-themes (subheadings in bold) are discussed below. Participants are identified by number, self-reported gender (F or M), and recruitment setting.

Theme 1: The burden of searching for guidance to address challenges with functioning and disability

The impact of the multi-faceted and unpredictable nature of Long COVID symptoms on daily function resulted in most participants seeking care. Physical, cognitive, emotional, social, and system factors coalesced to create challenges in finding appropriate care, which took a toll on various aspects of overall health and led participants to independently seek guidance.

Impact of physical symptoms on functioning triggered the search

Multiple participants across all recruitment settings referred to unexpected symptom “flare-ups” or “crashes” that made activities of daily living (ADL), such as personal hygiene, walking, household tasks, leisure pursuits, community involvement, and social participation difficult and their days unpredictable and taxing. One participant shared: “when I’m having a really bad flare up it's…almost impossible for me to do anything… I haven’t been able to work… [my parents] do my laundry, they help me clean, and…help me cook dinner…” (P9-F, public Long COVID clinic). Long COVID symptoms prevented participants from engaging in life roles as employees or parents, which often negatively impacted mental health: “Making suppers…like we would do it as a family or we [did] a lot of eating out because mom's too tired…I missed out on a lot of activities…I wasn’t well enough…There's a lot of loss there” (P15-F, public Long COVID clinic). These struggles drove participants to seek help in the healthcare system.

Lack of clarity puts the onus on the patient (to find services)

At the time of the study, Long COVID rehabilitation was not widely available or well-known across the province, as one participant described: “I never really thought that there [was] this physio…group, like I never even thought that there’d be such a thing” (P7-F, media coverage). Participants had not considered requesting referrals to rehabilitation because of symptom fluctuations or not believing that rehabilitation could help: “…the idea of being exhausted and not being able to concentrate…I don’t know how that would be served with an occupational therapist or PT” (P7-F, media coverage). Some participants were surprised to learn that PT could help with breathing: “I saw [a PT], but it was by fluke…I had never even heard of breathing physio. I didn’t know that was a thing” (P3-F, private PT clinic).

Getting referrals to Long COVID rehabilitation required practitioner or patient knowledge of the programs as it was difficult to find information about available services. Perceived as the first point of contact for referrals, some participants noted that primary care physicians were not aware of Long COVID services. For example, one participant expressed: “I’m grateful that the resources were there…[but] I had to know about it, I had to find it, I had to know how to access it and then I had to make it happen” (P12-F, media coverage).

If the option of referral to rehabilitation was presented, it was only after extensive diagnostic testing, even if participants expressed difficulty with ADL. Subsequently, they were not provided with timely guidance to help manage functional challenges and disability. Uncertainty with next steps and delays caused by waiting for referrals or test results added to their burden:

“I haven’t got a clue…my GP just sends me to this specialist, this specialist, and they did their due diligence…you know follow up…now…I don’t feel like I have the support or even the understanding of what to do” (P4-F, public Long COVID clinic).

Unclear pathways to access Long COVID rehabilitation resulted in participants struggling to find services. This burden was reduced for participants with accepted WCB claims, as one participant described: “I can call my case manager and…[tell them] what I need…people to help….they have a way for me to…go” (P9-M, WCB program). These participants were referred directly to multidisciplinary rehabilitation by their case worker or primary care physician.

Flying solo – a trial and error process at their own expense

If participants did not receive guidance to address challenges with functioning and disability, they used numerous strategies to independently find rehabilitation services. Participants utilized personal and professional relationships to find services. For example, one participant discussed how a family member helped:

“…that 1-800 number was given to me by a cousin…I didn’t know which way to turn, and she found this number because she works in a medical clinic…unless I was looking in the wrong places…that starting step is not easily recognizable…or easy to find” (P2-M, telerehabilitation advice line).

Regardless of recruitment setting, participants who experienced delays accessing rehabilitation or who were unable to access rehabilitation experimented with strategies to balance the demands of daily activities, work, and rest by modifying ADL, being selective about activities they performed, or getting help from others. Participants were also on their own to obtain assistive devices, such as shower seats, walkers, or scooters for energy management. Given that options were often not presented to them, participants sourced assistive devices based on personal knowledge and self-assessment. Using personal savings to pay out-of-pocket for private practitioners, self-monitoring (e.g., blood pressure monitor, pulse oximeter, smart watch) and assistive devices, and paying for services to help with more demanding household activities (e.g., housecleaning, meal services), added financial burden to participants, except for participants accessing funding and services through WCB-Alberta. The ongoing process of trying different strategies and looking for information and/or private practitioners to help self-manage symptoms came at a cost of time, energy, and finances, adding to the already heavy burden of living with Long COVID.

Theme 2: Supportive relationships promote engagement in rehabilitation

For participants accessing rehabilitation services, supportive patient–practitioner relationships and peer connections with others experiencing Long COVID symptoms facilitated engagement in rehabilitation.

Patient–practitioner relationships were pivotal

Participants spoke of unsupportive interactions with multiple health practitioners that negated their lived experiences and needs. For example, some experienced judgment about the validity and cause of their symptoms, especially if they could not provide a positive COVID-19 test. At times, health practitioners downplayed participants’ concerns about symptom exacerbation, which participants perceived as stigmatizing and resulted in participants not returning to that practitioner, delaying further rehabilitation.

Unsupportive experiences accentuated the importance of positive patient–practitioner relationships in supporting participants to engage in rehabilitation. Supportive relationships were developed with rehabilitation practitioners that listened, were knowledgeable, collaborative, and validated participant experiences. For example, at the private PT clinic, participants appreciated that practitioners were willing to collaborate and were “non-judgmental and patient-focused…like a team…not just like the expert giving advice to the patient” (P8-F, private PT clinic). Additionally, participants acknowledged and appreciated the efforts rehabilitation practitioners made to seek out treatment options, provide referrals, and follow-up, especially when evidence to guide rehabilitation was limited.

Practitioners acknowledged participants’ progress with rehabilitation and helped them to view Long COVID as a condition that might require prolonged self-management. Many participants struggled with the reality of slow or subtle improvements in function over time requiring long-term management. They expressed gratitude for how rehabilitation practitioners continued to support and validate their efforts, while helping them manage personal expectations of treatment progressions being “aggravatingly slow” (P14-F, private PT clinic).

Integrating peer support into rehabilitation

Group-based, clinician-led education programs at the private PT clinic facilitated connections with others experiencing similar symptoms, helping participants to feel less isolated and more supported. Participants appreciated the peer support and learning from others with Long COVID: “these education sessions…we all have the same issues …it was kind of nice to meet other people who have the same crappy things going on” (P15-F, private PT clinic). Although participants engaged in many self-directed strategies, the group-based program was viewed positively, helping participants recognize they are not alone and can take actionable approaches to self-manage.

Theme 3: Conditions for participation in safe rehabilitation

Flexible service delivery and practitioner responsiveness to symptom exacerbations helped create an environment for participation in appropriate and safe rehabilitation approaches. Being able to self-monitor symptoms and take proactive steps to prevent symptom exacerbations during activities helped participants feel safer to engage in activities inside and outside of the clinic setting.

Flexible care delivery

In some situations, participants experienced symptom exacerbations as practitioners did not consider how symptoms were impacted by rehabilitation. Engagement in graded exercise, or physical activity interventions based on fixed incremental increases of intensity,41 and having long appointments multiple times per week led to symptom exacerbation. This required increased levels of therapeutic rest after appointments: “the first week I think I had nine hours of appointments. And I kept saying it's too much, and then they say…we’ll cut it back, but then they just never did. And then I just went downhill” (P17-F, WCB program). Graded exercise interventions are now considered to be contraindicated for people experiencing PESE.8 Participants that attended the WCB program more recently shared that appointment frequency and program intensity was flexible, and virtual appointment options provided a safer environment to participate in rehabilitation.

Mode and frequency of service delivery were key considerations for patient safety. Some participants acknowledged that in-person observation and assessment contributed to personalized care. Others were concerned about re-exposure to COVID-19, making them hesitant to attend in-person sessions. Additionally, some participants did not have the energy to prepare for in-person appointments and fully participate, especially if they travelled long distances. Providing options for appointment frequency and location (in-clinic or virtually) based on participant symptoms and accommodating breaks during appointments helped create opportunities for participants to feel more confident participating in rehabilitation than if they were required to attend lengthy, in-person appointments. Virtual appointments decreased the risk of viral re-exposure while allowing participants to manage energy, which potentially prevented symptom exacerbation.

Ability to self-monitor symptoms during and after rehabilitation

Being able to provide symptom information to PTs helped guide progression of rehabilitation treatments to ensure activity levels were not increased too quickly. Participants self-monitoring their sleep, heart rate, and oxygen saturation in real-time using wearable devices (e.g., smart watch) recognized that elevated heart rate following activity often preceded symptom exacerbation. Keeping a journal of how symptoms changed over time helped some participants identify symptom patterns in relation to activities. As a result of self-monitoring, participants felt empowered to proactively modify and pace themselves as they started to re-engage in activities outside rehabilitation sessions.

Theme 4: Looking forward - provision of appropriate interventions at the right time

Several participants shared ideas for how to facilitate timely access to Long COVID rehabilitation. Their hope was that early education about pacing, coordinated services, and broad dissemination of local Long COVID rehabilitation resources would help others access relevant support sooner.

Early education on pacing, rest, and energy management

Many participants expressed that early education on resting and pacing (i.e., managing energy by balancing periods of activity with rest based on symptoms) should be provided to people with COVID-19. Initially, many participants were advised, or tried, to self-manage symptoms using graded exercise approaches, which often resulted in worsening symptoms. Integrating rehabilitation interventions into daily routines helped them realize the importance of resting, pacing, and returning to activities slowly to prevent symptom exacerbation. Education on pacing, self-monitoring, and breathing re-training was perceived to be an appropriate and effective approach to manage symptoms. Many participants wondered if their symptoms could have been prevented if education on pacing was provided before their symptoms became prolonged: “maybe [if] I would have taken tinier baby steps …I wouldn’t have…these huge crashes, and maybe my recovery would have been quicker” (P19-F, WCB program).

Coordinated care that can address multiple symptoms

Participants appreciated having access to practitioners in one setting to address multiple symptoms and challenges with functioning:

“…if there were…multidisciplinary clinics where you could just go…then have …information for like how to rest…pace…track your heart rate…just kind of an all-in-one place…it would be really helpful to…have that information up front…” (P11-F, private PT clinic).

For example, the WCB program included access to a multidisciplinary team to address a broad range of symptoms. At the private PT clinic, referrals could be made to voice coaches and OTs for further assessment and management. Services were not only available but could be appropriately coordinated in collaboration with participants.

Participants perceived appropriate and timely follow-up for non-respiratory complaints as essential. Because medical practitioners in primary care and respirologists at the public Long COVID clinics usually focused on diagnostic testing and respiratory functioning, services for attention difficulties, fatigue, orthostatic intolerance, and dysautonomia were often not coordinated. One participant, who accessed multiple services, described their initial perception of the public Long COVID clinic: “…it's labeled as a post-COVID clinic, I thought that would be like an all-encompassing clinic…my complaint at the time was still being coherent, memory type, low energy complaint versus a breathing complaint” (P4-M, private PT clinic). Having limited guidance or follow-up for managing challenges with fatigue, cognition, or unpredictable symptoms, delayed access to appropriate treatments. Participants believed that continuity of support was hampered by strict program durations (e.g., 6-week programs). They expressed that having an ongoing “safety net” (P15-F, public Long COVID clinic), or the ability to reconnect with appropriate practitioners at the right time (e.g., when planning for return-to-work) would provide essential support and potentially reduce delays of re-referral to a program.

Broader communication of local information about safe rehabilitation

Participants expressed that better awareness of, and accessibility to, credible information about Long COVID and information about local safe rehabilitation services was needed. One participant shared:

“I hope that now…the first thing they do is … [provide] the information…about COVID and what to do…things that could…help to manage my symptoms…whether it is the physio or…the counseling…and that there is a COVID clinic, and [this is what] the clinic does…” (P3-F, telerehabilitation advice line).

Some participants did not know where to access reliable information about local services for managing Long COVID, especially if it did not come from a trusted practitioner. This drove participants to online support groups or websites in other provinces or countries.

Participants who were able to access Long COVID rehabilitation, or had knowledge of the health system, expressed concern for others who were not able to self-advocate or lacked the knowledge and experience to effectively navigate the health system. They believed that better communication of information and resources would provide opportunities for people to access services when needed most.

Discussion

Findings from this qualitative, exploratory study provide insight into the diverse symptoms leading people to seek care for Long COVID symptoms and their experiences accessing rehabilitation services prior to the establishment of public-funded multidisciplinary Long COVID services. Participants shared experiences and perceptions related to the burden of seeking care, importance of supportive relationships, approaches to safe rehabilitation, and improving opportunities for people with Long COVID to access safe rehabilitation. Findings align with recent research and recommendations for Long COVID management.8,41,42 To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the perceptions and experiences of people with Long COVID accessing and engaging with rehabilitation services.

The combination of experiencing unpredictable Long COVID symptoms and disability, needing to navigate unclear processes to seek rehabilitation, and practitioners not discussing difficulties with functioning and disability, resulted in significant burden leading participants to search for information on their own. Some participants in our study were unable to access services to address their functional concerns. The burden of living with Long COVID symptoms and experiencing frustration and restrictions trying to access care has been well established in the literature.43–46 Findings from our study provide practical ways to overcome challenges related to finding and engaging with Long COVID rehabilitation services.

It appears that unless participants had prior knowledge of rehabilitation's role and scope or were referred, they did not seek out rehabilitation services. For participants who were unable to access rehabilitation, many did not know what options were available or how to access services to address their concerns. While many participants engaged in compensatory strategies on their own, having access to safe rehabilitation services may have promoted other ways to support participation in ADL and provide access to loan programs or funding to offset the cost of assistive devices. This highlights a need for broad promotion and dissemination of information about safe Long COVID rehabilitation and how to access local services in accessible formats, which may support patient understanding of Long COVID and shared decision making with health practitioners.14 The development of Alberta's Provincial Post COVID-19 Rehabilitation Response Framework should help promote access to safe rehabilitation services by providing guidance for practitioners, referral pathways to facilitate access to safe rehabilitation across the continuum of care, and screening tools (e.g., Post-COVID Functional Scale (PCFS)) to identify rehabilitation needs for people who experienced COVID-19 in Alberta.47 Information about local rehabilitation services is also publicly available on the provincial health system web page but was not well known at the time of this study.17,48,49

Participants discussed aspects of patient-practitioner relationships they viewed as supportive including collaboration, validation, and acknowledgement of self-management strategies. This support promoted engagement in safe rehabilitation and is well-supported in the literature.44–46,50 Rushforth and colleagues and Day and colleagues’ qualitative studies highlighted that healthcare practitioners who were engaged, validated patient experiences, and were willing to find answers were viewed as supportive which directly contrasted practitioners who dismissed or invalidated Long COVID symptoms.43,51 Similarly, person-centred care has been identified as a core component of Long COVID rehabilitation.6,8 A growing recognition of Long COVID and increased access to Long COVID guidelines and resources for health care practitioners should aid in developing understanding and promoting more therapeutic relationships.

Peer support through interactive, group-based interventions helped participants build supportive relationships with others having similar experiences. A hermeneutic systematic review of the peer support literature in long-term conditions such as diabetes, heart conditions, and others discusses the potential for peer support delivery models in Long COVID.52 Further research is needed on delivery of peer support in Long COVID management, particularly in the context of clinical programming.52

Participants accessing services with flexible care delivery options (e.g., virtual, in-person, taking breaks during sessions) felt better able to fully participate in safe rehabilitation sessions. Particularly for participants living in rural areas, preparing for, and travelling to multiple appointments was exhausting and potentially limited successful rehabilitation outcomes. There is limited evidence to validate the effectiveness of virtual or hybrid care delivery in Long COVID.47,53 One systematic review (n = 6 studies) identified tele-rehabilitation as a potential care delivery method to help people with Long COVID participate in safe rehabilitation.54 Current recommendations note that safe rehabilitation should be tailored to individual needs, which includes how care is delivered.14 Given the episodic and unpredictable nature of Long COVID symptoms,55 being able to modify in-person sessions to virtual delivery may support participation and potentially prevent cancelled sessions.

Participants reported that some traditional approaches to rehabilitation, including progressive loading of physical or cognitive activity, exercise, or graded activity, exacerbated symptoms of Long COVID, which is consistent with current literature.6,16 Using these types of approaches may worsen disability and prevent people from participating in daily activities, life roles, and rehabilitation.6 However, the literature is still emerging and is inconclusive with exercise-based rehabilitation potentially improving some aspects for certain patients without PESE.56 Current recommendations suggest comprehensive pre-screening for cardiac impairment, exertional oxygen desaturation, PESE and orthostatic intolerances that could limit exercise, as well as focusing on energy conservation and pacing strategies.6,8,13,16,41 Monitoring for PESE symptoms during rehabilitation interventions, and in the days following, is strongly recommended.8 Additionally, participants in our study reported that energy conservation, pacing, and self-monitoring heart rate and blood pressure interventions were effective and that they helped to create safer conditions for participation in rehabilitation, which is supported by the literature.6,42 Aligning with current recommendations, practitioners should provide personalized energy-conserving approaches to safe Long COVID rehabilitation, including education and skills training on self-management strategies which may help reduce symptom severity and improve daily function.8,14,16

Participants reported that education on pacing and resting was perhaps the most valuable information received from practitioners. Some suggested that people diagnosed with COVID-19 should receive this information as early as possible to potentially prevent Long COVID symptoms. Although there is an evidence gap related to the effectiveness of early pacing education and rehabilitation outcomes in Long COVID, Parker and colleagues examined the effectiveness of a 5-phase pacing protocol in 31 individuals with Post-COVID syndrome, which resulted in a reduction of the number of PESE episodes and improved quality of life.57 The World Health Organization and World Physiotherapy recommends education about breathing, pacing, and resuming activities conservatively based on symptoms for anyone with Long COVID.8,41 Further research is needed to determine the effectiveness of early pacing education on the progression of Long COVID symptoms.

Care coordination and access to a multi-disciplinary team with ongoing follow-up allowed participants to feel supported while navigating fluctuating symptoms, lengthy recovery periods, and eventual return to various activities, including work. Literature describing care models for Long COVID53 and current guidelines8,41 suggest that multidisciplinary care should be coordinated with local referral pathways to facilitate access to appropriate services. Acknowledging the long-term nature of Long COVID and associated need for services to support return to activities, limited funding and staff resources have been identified as potential barriers to providing ongoing services.14,53 In Alberta, Long COVID clinics now include a multi-disciplinary team, with medical specialists and allied health/rehabilitation supports to address the impact of the diverse range of Long COVID symptoms on function across the care continuum.58 Although this study took place in a single province in Canada, the recruitment sites were both publicly and privately funded, which is representative of services offered in the Canadian health system and the geographic distribution of the population. Findings can be considered for application in other publicly and privately funded rehabilitation programs that offer services to people living with Long COVID in urban and rural settings.

The findings have a number of practical implications that can inform the development of targeted interventions for Long COVID. Many participants struggled to access information about available rehabilitation services to address Long COVID symptoms. Programs can consider examining ways to increase accessibility of information about available services to other practitioners and the public. Participants’ experiences and suggestions for improving rehabilitation services reinforce recommendations in current guidelines of providing early education on pacing, integrating peer support networks in service delivery models, and acknowledging and including the patient perspectives in care planning and delivery. Our findings have been used to inform a proposed framework and recommendations for the management of Post-COVID-19 Condition in Canada.59 While Brehon and colleagues37 report findings related to broader health services that participants discussed during the interviews, this paper highlights findings that can be applied specifically to rehabilitation settings.

Strengths and Limitations

There are several strengths within our approach to examining the lived experiences of accessing rehabilitation services for people with Long COVID. Having a research team with diverse professional backgrounds and including people with lived experiences of Long COVID on the research team allowed us to ensure our research would be relevant to both patients and clinicians in different settings. Using a conceptual framework helped to ground our approach to data collection and analysis in patient and system-level aspects of health care. We also offered flexible options for interviewing participants (i.e., Zoom or telephone), including the option of breaking up the interview into multiple sessions to accommodate differences in participants’ abilities to complete the interview in one session.

Some limitations impact transferability of our results. Available services and evidence to support care for people living with Long COVID has rapidly evolved since 2021, when data were collected. It is possible that people accessing Long COVID services more recently may have different perceptions about access and current rehabilitation services, highlighting the need for continued research. Many participants in this study accessed multiple services to address their concerns, making it difficult to make cross-case comparisons between different recruitment settings. In addition, programs evolved as patient needs changed and new evidence emerged so attributing patient experiences to aspects of a particular program was not possible in the scope of this study. In addition, this study took place in Alberta, within a high-income country, which may limit transferability of the results to other dissimilar jurisdictions. Our findings may not represent all perspectives of the wide diversity and intersections of experience with Long COVID. Examining experiences across different settings may identify specific aspects of programs that impact access or participants’ experiences. Having two people conducting the interviews may have impacted interview consistency. However, the number of participants, using a common interview guide, and frequent review and debrief sessions between interviewers likely mitigated any disadvantages.

Conclusion

Our study aimed to explore the experiences of people living with Long COVID that led them to seek rehabilitation services, their experiences trying to access services, and how well the services they accessed were able to meet their needs. Findings highlight the lived experiences of people with Long COVID as they struggled to manage symptoms, seek out services to address challenges with functioning and disability, and interact with various rehabilitation programs and services. Results suggest Long COVID rehabilitation services should provide multi-disciplinary, flexible, patient-centred approaches that acknowledge individual patients’ experiences. Future research should include gender, ethnic, and geographically diverse participants across different settings to strengthen transferability and to understand if perceptions of access and care are different. In light of the ongoing emergence of evidence related to experiences and access to Long COVID health services, continued research reflecting the diverse experiences of those living with Long COVID will contribute to improvements in clinical practice, programs, and policy that could positively influence quality of life and well-being.

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

-

•

Research, clinical guidelines, and resources for managing Long COVID are rapidly evolving as research evidence emerges. Current guidance is largely based on expert consensus.

What this study adds:

-

•

Findings highlight the lived experiences of people with Long COVID as they struggled to manage symptoms and interacted with various rehabilitation programs and services.

-

•

Functional challenges experienced by people living with Long COVID highlight the need for rehabilitation to promote participation in ways that prevent symptom exacerbation.

-

•

Early education on the importance of resting, pacing, and self-monitoring may be proactive strategies to avoid prolonged symptoms.

-

•

From the perspective of those with lived experiences, Long COVID rehabilitation services should provide multi-disciplinary, flexible, patient-centred approaches that acknowledge individual patients’ experiences.

Douglas Gross PhD, BScPT, is Professor & Chair of the Department of Physical Therapy at the University of Alberta (Edmonton, Canada) and Director of the Rehabilitation Research Centre. Doug's scholarship focuses on evaluating rehabilitation approaches to prevent work disability. He is a McCalla Professor, Killam Laureate, and Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation.

Appendix 1

Table 1 Long Covid Rehabilitation Recruitment Settings, Referral Sources and Services in Alberta, Canada (Late 2021/Early 2022)

| Setting | Description and referral source | Services offered or available |

|---|---|---|

| Telerehabilitation Advice Line | • Publicly funded telephone service • Advice line contacted patients post-discharge from hospital • Self-referral by calling a toll-free number |

• Phone assessment by OT or PTs • Online resources provided via email |

| Public physician led Long COVID clinics | • Three publicly funded clinics lead by physician specialists (pulmonology) • One clinic required a COVID positive test (Polymerase Chain Reaction) • One clinic required patients to have respiratory symptoms • One clinic accepted patients with any Long COVID symptoms |

• Specialist referrals • Diagnostic testing • Symptom management |

| Specialized PT clinic | • Private practice clinic funded through: ∘ Private insurance ∘ Self-pay |

• In-person or virtual 1:1 sessions (PT/OT/Voice therapy) • Multi-disciplinary psychoeducational group-based program on managing Long COVID |

| WCB rehabilitation program | • Multidisciplinary rehabilitation program serving people exposed to COVID-19 in the workplace • Must have accepted WCB claim • Referrals made through WCB care pathways and claim owners |

• Multi-disciplinary rehabilitation program (OT/PT/Kinesiologist/ Psychologist) • Psychoeducational approaches for management of LC symptoms, guidance on pacing, energy conservation, and breathing strategies • Advice about work activity, exploration of modified duties, and negotiation with employers about appropriate duties |

Figure A1.

Qualitative data analysis process.

Table 2.

Self-Reported Ethnicity of Participants Living with Long Covid

| Self-reported ethnicity | Total† |

|---|---|

| Self-reported cultural or ethnic background* | |

| Belgian | 2 |

| Black | 1 |

| Canadian | 2 |

| Chinese | 1 |

| East Indian | 3 |

| English | 2 |

| European | 1 |

| Filipino | 3 |

| French | 1 |

| Indigenous | 2 |

| Irish | 1 |

| Italian | 1 |

| Métis | 2 |

| Pakistani | 1 |

| Scottish | 1 |

| Swedish | 1 |

| Vietnamese | 1 |

| White | 39 |

Participants were asked to self-identify their cultural or ethnic background using the open-ended question “How would you describe your cultural or ethnic background?”

Total does not add to 56 as some participants identified with multiple categories.

Appendix 2: Interview Guide

Exploring Rehabilitation Needs and Access to Services for Long COVID

Study objectives:

We aim to better understand the need for, and access to, rehabilitation services by people living with Long COVID. We will meet this aim through exploring:

-

(1)

The health concerns and needs leading people with Long COVID to seek care,

-

(2)

Experiences of people living with Long COVID with rehabilitation services received, including barriers to access, and

-

(3)

How well available services met (or did not meet) health- and rehabilitation-related needs.

Interview Guide

Introduction

Thank you for agreeing to participate in this study. As noted in the informed consent form, your participation is entirely voluntary. You do not have to answer any questions that you do not want to. The interview will take about 60 minutes but could last up to 90 minutes. If you would like to take a break for any reason during the interview, please let me know. We can do the interview in multiple sessions, if necessary. I will be recording this interview, if that is okay with you, so that we capture what you say exactly how you say it but all of your contributions will remain anonymous so no one will be able to identify anything that you say. Does that sound okay? Do you have any questions before we begin?

[START RECORDING]

1. We want to better understand the need for, and access to, rehabilitation services, like physiotherapy or occupational therapy for example, by people living with Long COVID. We’re defining Long COVID as any symptoms of COVID-19 that are lingering three months or more after recovery. To start, I was hoping you could tell me your Long COVID story?

Possible probes

-When did you first start noticing that your symptoms were lingering? Any particular symptoms?

-What happened after you noticed your symptoms were lingering?

-How were you treated in the health system as someone who had COVID-19 and then later on as someone with Long COVID?

2. How do you feel that your recovery has gone to date?

Possible probes

-How do you feel that your life has been affected by living with Long COVID?

-

-How do you feel that your symptoms have interfered with your daily home and work activities?

-Did any of your symptoms change how you sleep now compared to how you slept before developing COVID? How?

-How, if at all, do you feel that long COVID has affected your return to work?

-To what extent have your Long COVID symptoms changed over time?

3. What supports, if any, have you received for Long COVID, to date?

Possible probes

-

-What health care providers have you seen? What have they done?

-Medical – family doctor, cardiology, neurology, respirologist, pulmonologist?

-Allied health – physiotherapist, occupational therapist, speech language pathologist

-Could you speak a bit about whether you’ve received any psychological or social work support?

-If they speak about having received rehabilitation, ask relevant branch A questions

-If they have not received any rehabilitation supports, ask branch B questions

A. If they have received rehabilitation for Long COVID:

4. Can you tell me about your experience of initially accessing rehabilitation for Long COVID? We are defining rehabilitation as allied health care that focuses on helping you regain your function and abilities rather than trying to cure the disease.

Possible probes

-When did you seek rehabilitation? How long after you noticed your symptoms were lingering?

-

-What led you to seek rehabilitation?

-

-Was there someone that encouraged you to seek rehabilitation?

-Did you seek rehabilitation services on your own or were you guided by a healthcare professional?

-Were there any particular symptoms that you were experiencing that made you more motivated to seek rehabilitation initially?

-

-

-How was the contact with the rehabilitation service made?

-How did you feel about the process?

-Could you expand on how … happened?

-Could you give an example of …?

5. Could you walk me through what your ongoing rehabilitation was/is like?

Possible probes

-

-What types of providers have been involved in your care?

-Allied health – physiotherapist, occupational therapist, speech language pathologist

-

-What types of interventions have you received?

-What was your biggest takeaway from each provider you saw? What did you learn from them?

-

-How would you describe your rehabilitation providers’ approach with you?

-Person-centred? Do you feel like the rehabilitation providers you encountered understood your needs?

6. Do you feel as though the rehabilitation you received addressed your needs or concerns?

Possible probes

-To what extent do you feel that you got the answers or information you needed?

-

-To what extent do you feel that your rehabilitation was provided in a safe manner?

-Culturally safe? Respected belief system?

7. To what extent do you feel that the rehabilitation you received was effective?

Possible probes

-Did it match the symptoms you were experiencing?

-Was it effective in helping you return to activities that are important and meaningful for you? (Examples: work, physical activity, reading, household duties, etc.)

8. Were there any costs associated with the treatments you received, keeping in mind that costs could be financial but also related to time, travelling, emotional costs, etc?

Possible probes

-

-Financial costs of the service?

-Do you have access to private insurance?

-What services were covered for you? Which ones were not covered?

-Time? Travel Time? Time off work for themselves and their spouse?

9. If rehabilitation has come to an end, How did your rehabilitation come to an end?

Possible probes

-How, when, and by whom was the decision made about the end of your rehabilitation?

-

-To what extent do you feel the rehabilitation you received for Long COVID was adequate?

-What are your thoughts on the length of rehabilitation you received?

-What are your thoughts on the type of rehabilitation you received?

-What are your thoughts on the rehabilitation providers that you saw?

10. If they received some rehabilitation for Long COVID but stopped part way through: Could you please tell me about why you stopped your Long COVID rehabilitation part way through?

Possible probes

-What made you want to discontinue your care?

B. If they have not received rehabilitation for Long COVID:

11. To what extent was rehabilitation ever presented to you as an option to help with your Long COVID experience?

Possible probes

-If not presented as an option, What avenues of advertising or getting the word out about rehabilitation for Long COVID would have captured you as part of the audience?

-If not presented as an option, Who do you think should have presented it as an option?

-If it was presented as an option, Is there any reason that you have chosen not to access rehabilitation?

12. To what extent do/did you feel that rehabilitation is/was not meant for you?

Possible probes

-Why or why not?

Closing Questions for Everyone:

13. To what extent have you managed your symptoms on your own?

Possible probes

-Did you choose to manage your symptoms on your own?

-Would you have liked to have more support? What support do you feel you needed?

14. To what extent would you consider Long COVID rehabilitation accessible to you and the rest of the Long COVID population?

Possible probes

-Were there any barriers that you experienced when trying to access rehabilitation?

-What barriers do you think might be present for other people?

-Could you speak a little bit about your thoughts on virtual care versus in-person care? Is there one format that you would prefer more than the other? Why?

15. In your Long COVID rehabilitation journey to date, is there anything that stood out as going well?

16. What do you think could have been done differently along your rehabilitation journey with Long COVID, to date?

Possible probes

-What could have been improved in the way your Long COVID rehabilitation needs were cared for or addressed?

-

-If you could change one experience you’ve had, or did not have, during your Long COVID journey for the next person to make their rehabilitation journey better, what would it be?

-Why?

-

-If you were to have had an ideal rehabilitation experience for long-term COVID, what would that look like for you?

-When would you access services?

-What services would you have accessed?

-How would you have learned about these resources?

-Who would have helped you navigate to these resources?

-Where would these services take place? In-person versus online?

17. Looking forward, what are your expectations for rehabilitation?

18. Is there anything else that we have not discussed but that you would like to share?

[STOP RECORDING]

Thank you so much for participating in an interview. We really appreciate your time and insight. Before we wrap up, I’m going to ask you a few questions about yourself to help us get a sense of some of your demographics. These questions aren’t going to be tied to your previous answers but are just to help us ensure we end up with a representative sample. If you don’t want to answer any of the questions, that's completely fine, just let me know.

What is your age?

What is your gender?

Would you say you live in a rural or urban area?

How would you describe your cultural or ethnic background?

Funding Statement

This project was funded by an Operating Grant: Emerging COVID-19 Research Gaps & Priorities - Post COVID-19 from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

References

- 1.Soriano J, Allan M, Alsokhn C, et al. A clinical case definition of post COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. World Health Organization; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID); 2023. [cited 2023 June 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition.

- 3.Statistics Canada. Long-term symptoms in Canadian adults who tested positive for COVID-19 or suspected an infection, January 2020 to August 2022; 2022. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221017/dq221017b-eng.htm.

- 4.Callard F, Perego E. How and why patients made Long Covid. Soc Sci Med. 2021;268:113426. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113426. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCorkell L, S Assaf G, E Davis H, et al. A patient-led research collaborative: embedding patients in the Long COVID narrative. Pain Rep. 2021;6(1):e913. 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000913. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeMars J, Brown DA, Angelidis I, et al. What is safe Long COVID rehabilitation? J Occup Rehabil. 2023;33(2):227–30. 10.1007/s10926-022-10075-2. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Twomey R, DeMars J, Franklin K, et al. Chronic fatigue and postexertional malaise in people living with Long COVID: an observational study. Phys Ther. 2022;102(4):1–12. 10.1101/2021.06.11.21258564. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Physiotherapy. World physiotherapy response to COVID-19 briefing paper 9. Safe rehabilitation approaches for people living with Long COVID: physical activity and exercise; 2021. London, UK: World Physiotherapy. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Disability; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/disability#tab=tab_1.

- 10.Davenport TE, Stevens SR, Stevens J, et al. Lessons from Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome for Long COVID: postexertional symptom exacerbation is an abnormal response to exercise/activity. movement science media JOSPT; 2022.

- 11.Brown D, O’Brien K. Conceptualising Long COVID as an episodic health condition. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(9):e007004. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007004. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tabacof L, Tosto-Mancuso J, Wood J, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome negatively impacts physical function, cognitive function, health-related quality of life, and participation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;101(1):48–52. DOI: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001910. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Rehabilitation needs of people recovering from COVID-19: scientific brief; 2021. [cited 2023 June 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci-Brief-Rehabilitation-2021.1.

- 14.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence SIGN, Royal College of General Practitioners. Covid19 rapid guideline: managing the Long term effects of Covid19; 2022.

- 15.World Physiotherapy. Long Covid: resources to support in the understanding and management of the consequences of Long Covid, 2022. Available from: https://world.physio/covid-19-information-hub/long-covid.

- 16.World Health Organization. Support for rehabilitation: self-management after COVID-19-related illness. 2nd ed.; 2022.

- 17.Alberta Health Services. Recovery & rehabilitation after COVID-19: resources for health professionals; 2022. Available from: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/topics/Page17540.aspx.

- 18.Toy A. 3 Alberta clinics study long-term effects of COVID-19, lasting symptoms. Global News; 2021.

- 19.Breathewell Physiotherapy. Post-COVID support; n.d. [cited 2022 Apr 4]. Available from: https://www.breathewellphysio.com/post-covid-recovery-support.html#/.

- 20.WCB-Alberta. COVID-19; 2023. [cited 2023 June 8]. Available from: https://www.wcb.ab.ca/about-wcb/whats-new/COVID-19.html.

- 21.Harrison SL, Brooks D. Active patient engagement: long overdue in rehabilitation research. Physiother Can. 2015;67(4):305–10. 10.3138/ptc.67.4.GEE. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alberta SPOR Support Unit. Patient engagement in health research: a how-to guide for researchers; 2018.

- 23.Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Foundations of SPOR; 2019. Available from: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/51039.html.

- 24.Thorne S. Interpretive description: qualitative research for applied practice. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hunt MR. Strengths and challenges in the use of interpretive description: reflections arising from a study of the moral experience of health professionals in humanitarian work. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(9):1284–92. 10.1177/1049732309344612. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson Burdine J, Thorne S, Sandhu G. Interpretive description: a flexible qualitative methodology for medical education research. Med Educ. 2021;55(3):336–43. 10.1111/medu.14380. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levesque JF, Harris MF, Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:18. 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cu A, Meister S, Lefebvre B, et al. Assessing healthcare access using the Levesque's conceptual framework - a scoping review. Int J Equity Health. 2021. May 7;20(1):116. 10.1186/s12939-021-01416-3. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho JW, Kuluski K, Im J. “It's a fight to get anything you need” - accessing care in the community from the perspectives of people with multimorbidity. Health Expect. 2017;20(6):1311–9. 10.1111/hex.12571. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teodoro IPP, Rebouças VdCF, Thorne SE, et al. Interpretive description: a viable methodological approach for nursing research. Escola Anna Nery 2018. Mar 11; 22. 10.1590/2177-9465-ean-2017-0287 [DOI]

- 31.Thorne S, Kirkham SR, MacDonald-Emes J. Interpretive description: a noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Res Nurs Health. 1997;20(2):169–77. . PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayoubkhani D, Bosworth M, King S. Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK - Office for National Statistics. Office for National Statistics; 2022. p. 1–7.

- 33.Thorne S, Oliffe J, Kim-Sing C, et al. Helpful communications during the diagnostic period: an interpretive description of patient preferences. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2010;19(6):746–54. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01125.x. PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health 2019; 13:2, 201–16. 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zoom. Zoom Video Communications Inc., 2023.

- 36.QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo (released in March 2020); 2020.

- 37.Brehon K, Miciak M, Hung P, et al. “None of us are lying”: an interpretive description of the search for legitimacy and the journey to access quality health services by individuals living with Long COVID. BMC Health Serv Res 23, 1396 (2023). 10.1186/s12913-023-10288-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braun V, Clarke V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Counsel Psychother Res. 2021; 21:1, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualit Res Psychol 2021; 18:3, 328–52. 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organisation. Clinical management of COVID-19: living guideline (WHO/2019-nCoV/clinical/2023.1). Geneva; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Francis A, Coleman J, Harris J, et al. Rehabilitation for clients with post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID) guidance for Canadian rehabilitation and exercise professionals; 2021.

- 43.Rushforth A, Ladds E, Wieringa S, et al. Long Covid - the illness narratives. Soc Sci Med. 2021. Oct;286:114326. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114326. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Macpherson K, Cooper K, Harbour J, et al. Experiences of living with long COVID and of accessing healthcare services: a qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e050979. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050979. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burton A, Aughterson H, Fancourt D, et al. Factors shaping the mental health and well-being of people experiencing persistent COVID-19 symptoms or ’long COVID’: qualitative study. BJPsych Open. 2022;8(2):e72. 10.1192/bjo.2022.38. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kingstone T, Taylor AK, O’Donnell CA, et al. Finding the ’right’ GP: a qualitative study of the experiences of people with long-COVID. BJGP Open. 2020;4(5):bjgpopen20X101143. 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101143. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manhas KP, O’Connell P, Krysa J, et al. Development of a novel care rehabilitation pathway for post-COVID conditions (Long COVID) in a provincial Health System in Alberta, Canada. Phys Ther. 2022;102(9):pzac090. 10.1093/ptj/pzac090. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alberta Health Services Post-COVID-19 Task Force. Provincial adult Long COVID pathway; 2022.

- 49.Primary Care Networks Edmonton Zone and Alberta Health Services. Edmonton zone: primary care pathway for Post COVID-19 rehabilitation; 2021.

- 50.Ladds E, Rushforth A, Wieringa S, et al. Persistent symptoms after Covid-19: qualitative study of 114 “long Covid” patients and draft quality principles for services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1144. 10.1186/s12913-020-06001-y. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Day H. Exploring online peer support groups for adults experiencing long COVID in the United Kingdom: qualitative interview study. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(5):e37674. 10.2196/37674. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mullard JCR, Kawalek J, Parkin A, et al. Towards evidence-based and inclusive models of peer support for long covid: a hermeneutic systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2023. Mar;320:115669. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115669. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Décary S, De Groote W, Arienti C, et al. Scoping review of rehabilitation care models for post COVID-19 condition. Bull World Health Organ. 2022;100(11):676–88. 10.2471/BLT.22.288105. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Valverde-Martinez MA, Lopez-Liria R, Martinez-Cal J, et al. Telerehabilitation, a viable option in patients with persistent Post-COVID syndrome: a systematic review. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11(2):187. 10.3390/healthcare11020187. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Brien KK, Brown DA, McDuff K, et al. Conceptualising the episodic nature of disability among adults living with Long COVID: a qualitative study. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8(3):e011276. 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-011276. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soril LJJ, Damant RW, Lam GY, et al. The effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation for Post-COVID symptoms: a rapid review of the literature. Respir Med. 2022. Mar 2;195:106782. 10.1016/j.rmed.2022.106782. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parker M, Sawant HB, Flannery T, et al. Effect of using a structured pacing protocol on post-exertional symptom exacerbation and health status in a longitudinal cohort with the post-COVID-19 syndrome. J Med Virol. 2023;95(1):e28373. 10.1002/jmv.28373. PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alberta Health Services. FAQ for health providers: long COVID-19 inter-professional outpatient program (IPOP); 2022. Available from: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/ppih/if-ppih-covid-19-ipop-faq.pdf.

- 59.Office of the Chief Scientific Advisor of Canada. Post-COVID-19 condition in Canada: what we know, what we don’t know, and a framework for action. Canada; 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID); 2023. [cited 2023 June 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition.

- Statistics Canada. Long-term symptoms in Canadian adults who tested positive for COVID-19 or suspected an infection, January 2020 to August 2022; 2022. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/221017/dq221017b-eng.htm.

- World Health Organization. Disability; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/disability#tab=tab_1.

- Davenport TE, Stevens SR, Stevens J, et al. Lessons from Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome for Long COVID: postexertional symptom exacerbation is an abnormal response to exercise/activity. movement science media JOSPT; 2022.

- World Health Organization. Rehabilitation needs of people recovering from COVID-19: scientific brief; 2021. [cited 2023 June 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci-Brief-Rehabilitation-2021.1.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence SIGN, Royal College of General Practitioners. Covid19 rapid guideline: managing the Long term effects of Covid19; 2022.