Abstract

Introduction:

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is the most lethal subtype of renal cell carcinoma with a high invasive potential. Radiomics has attracted much attention in predicting the preoperative T-staging and nuclear grade of ccRCC.

Objective:

The objective was to evaluate the efficacy of dual-energy computed tomography (DECT) radiomics in predicting ccRCC grade and T-stage while optimizing the models.

Methods:

200 ccRCC patients underwent preoperative DECT scanning and were randomized into training and validation cohorts. Radiomics models based on 70 KeV, 100 KeV, 150 KeV, iodine-based material decomposition images (IMDI), virtual noncontrasted images (VNC), mixed energy images (MEI) and MEI + IMDI were established for grading and T-staging. Receiver operating characteristic analysis and decision curve analysis (DCA) were performed. The area under the curve (AUC) values were compared using Delong test.

Results:

For grading, the AUC values of these models ranged from 0.64 to 0.97 during training and from 0.54 to 0.72 during validation. In the validation cohort, the performance of MEI + IMDI model was optimal, with an AUC of 0.72, sensitivity of 0.71, and specificity of 0.70. The AUC value for the 70 KeV model was higher than those for the 100 KeV, 150 KeV, and MEI models. For T-staging, these models achieved AUC values of 0.83 to 1.00 in training and 0.59 to 0.82 in validation. The validation cohort demonstrated AUCs of 0.82 and 0.70, sensitivities of 0.71 and 0.71, and specificities of 0.80 and 0.60 for the MEI + IMDI and IMDI models, respectively. In terms of grading and T-staging, the MEI + IMDI model had the highest AUC in validation, with IMDI coming in second. There were statistically significant differences between the MEI + IMDI model and the 70 KeV, 100 KeV, 150 KeV, MEI, and VNC models in terms of grading (P < .05) and staging (P ≤ .001). DCA showed that both MEI + IDMI and IDMI models outperformed other models in predicting grade and stage of ccRCC.

Conclusions:

DECT radiomics models were helpful in grading and T-staging of ccRCC. The combined model of MEI + IMDI achieved favorable results.

Keywords: dual-energy CT, nuclear grade, radiomics, renal cell carcinoma, T-stage

1. Introduction

Clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) is a type of malignant tumor originating from the urinary system, accounting for about 70%–85% of renal cell carcinoma,[1] and, it is the most lethal subtype with a high invasive potential.[2] The 5-year survival rate of patients with ccRCC is closely related with the pathological nuclear grade.[3] Patients with lower pathological nuclear grade of ccRCC have better prognosis and lower risk of recurrence than those with higher pathological nuclear grade.[4,5] Treatment of RCC includes radical resection, partial resection, tumor enucleation, as well as minimally invasive ablation and targeted therapy developed in recent years. Conservative surgery or minimally invasive ablation can be used for RCC with low pathological grade and staging, and active monitoring or targeted therapy can also be performed in some cases.[6] Tumor T-staging is a comprehensive assessment of tumor progression, and has great significance to the selection of treatment including surgical methods, the formulation of perioperative treatment plan and the prognosis of patients. Biopsy and histopathology are most commonly used for renal cancer grading and staging before operation. However, the disadvantages such as its inherent invasive, hysteresis, in vitro, and dependence on the accuracy puncture tissue limit its application.

Therefore, it is necessary to develop a noninvasive technique for accurately grading the preoperative pathology and T-staging for ccRCC.

Radiomics can extract a large number of image features, combine image quantitative analysis with machine learning, and transform the tumor internal features into rich quantitative features through different algorithms.[7,8] It has shown potential in tumor diagnosis, differential diagnosis, grading, and efficacy evaluation.[9–13] As a noninvasive imaging technology radiomics has attracted much attention in predicting the preoperative T-staging and nuclear grade of ccRCC.

Compared with single energy computed tomography, dual-energy scanning of dual-energy computed tomography (DECT) can obtain mixed energy images (MEI) of different proportions, virtual mono-energy images (VMI), and iodine-based material decomposition images (IMDI) through postprocessing workstation, and significantly improve tissue resolution and material recognition ability.[14,15] Moreover, IMDI can reflect the vascularization of various tissues via measuring the concentration of iodine (contrast reagent)[16] and is conducive to the detection of vascular rich tumor.[16,17]

Previous radiomics studies on pathological grading and staging of other tumors based on DECT had obtained good results.[18–20]However, the pathological grading and staging of ccRCC based on DECT radiomics are rarely reported. Moreover, there is no consensus with multiple parameters of DECT based radiomics including multiple VMI and IMDI, so it needs to be further studied to find out the best radiomics model. Herein, we investigated the value of radiomics based on the DECT in predicting pathological nuclear grade and T-stage of ccRCC. The efficacies of radiomics models based on different mono-energy VMI, IMDI, and MEI were compared. The potential of DECT as the noninvasive method in clinical decision-making and precision medicine was explored.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Jinan Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University and the patient consent was waived. A total of 200 patients with postoperatively pathologically confirmed ccRCC in our hospital from January 2015 to January 2022 were included in the study. There were 137 males and 63 females. Their mean age was 57 ± 11.24 years old and their age range was 33–82 years old. The inclusion criteria were as follows: radical nephrectomy or nephron sparing surgery was performed, and postoperative pathology confirmed ccRCC; complete clinical data could be obtained; and contrast-enhanced DECT of kidney was performed within 1 week before surgery.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: patients with poor image quality that affected the delineation and feature extraction of the region of interest; patients with cardiovascular or renal disease that seriously affected the degree of renal enhancement; patients with previous abdominal surgery; and patients with multiple lesions and poorly defined tumor boundaries.

2.2. Pathological staging and nuclear grading

All patients received radical nephrectomy or nephron sparing surgery. Surgical specimens were stained with H&E and examined by 2 pathologists with more than 5 years of professional experience. According to WHO/ISUP nuclear grade of renal cancer, 149 cases were defined as low-grade (grade 1–2), and, 51 cases were defined as high-grade (grade 3–4). According to the AJCC T-staging system, 152 cases had ccRCC at T1–T2 and 48 cases had ccRCC at T3–T4. The final classification and T-staging were decided by the 2 pathologists in consensus. General clinical data of all patients were shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

General clinical data of all patients of the 200 patients n (%).

| T-staging | Grading | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | Total | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Total | |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | 101 (50.5) | 11 (5.5) | 14 (7.0) | 11 (5.5) | 137 (68.5) | 9 (4.5) | 86 (43.0) | 37 (18.5) | 5 (2.5) | 137 (68.5) |

| Female | 31 (15.5) | 9 (4.5) | 14 (7.0) | 9 (4.5) | 63 (31.5) | 10 (5.0) | 44 (22.0) | 7 (3.5) | 2 (1.0) | 63 (31.5) |

| Total | 132 (66) | 20 (10) | 28 (14.0) | 20 (10) | 200 (100) | 19 (9.5) | 130 (88.22) | 44 (22) | 7 (3.5) | 200 (100) |

| Age (yr) | ||||||||||

| 33–60 | 85 (42.5) | 14 (7.0) | 21 (10.5) | 7 (3.5) | 127 (63.5) | 16 (8.0) | 78 (39.0) | 30 (15.0) | 1 (0.5) | 125 (62.5) |

| 61–82 | 45 (22.5) | 8 (4.0) | 7 (3.5) | 13 (6.5) | 73 (36.5) | 2 (1.0) | 53 (26.5) | 12 (6.0) | 8 (4.0) | 75 (37.5) |

| Total | 130 (65) | 22 (11.0) | 28 (14.0) | 20 (10.0) | 200 (100) | 18 (9.0) | 131 (66.5) | 42 (21.0) | 9 (4.5) | 200 (100) |

2.3. DECT imaging acquisition

All patients underwent contrast-enhanced DECT before surgery and signed informed consent before CT scanning. Somatom Force CT scanner (Siemens Healthineers, Forchheim, Germany) was used for scanning. Nonionic contrast agent (Omnipaque, 300 mgI/mL) (1.2 mL/kg; 60–80 mL) was injected intravenously at injection rate of 3.5 mL/s. In dual-energy mode, the cortical phase and parenchymal phase enhanced scanning was performed with the automatic exposure system. The respective parameters were as follows: the delay times were 30 seconds (cortical phase) and 80 seconds (parenchymal phase) respectively; the tube voltages were 100 kvp and sn150 kvp; and the tube currents were 130~180 mAs and 80~90 mAs. The images were reconstructed at 1.0 mm slice thickness and 1.0 mm interval, and then analyzed by using the postprocessing workstation (syngo. via). Finally, the 70 KeV, 100 KeV, 150 KeV, MEI, IMDI, and virtual noncontrasted (VNC) images of the 2 phases were obtained. Then, all these data were imported to radcloud platform (https://mics.huiyihuiying.com/).

2.4. Image segmentation and image preprocessing

All images were reviewed and the 3D volume of interests (VOIs) were delineated slice by slice manually by 2 junior radiologists with more than 5 years of working experience in this field, who were blinded to the clinical information of the patients but were aware that the lesions were ccRCC. Then, all contours were reviewed and revised by a senior radiologist with 20 years of experience. If the discrepancy was ≥5%, the tumor borders were determined by the senior radiologist with 20 years of experience.[21] Before VOI segmentation, all images were uniformly enlarged by 1.5 times, and window width and window level were 250/50 HU.

Eventually, the VOIs of 200 patients were segmented on Radcloud platform. The patients were randomized into validation cohort and training cohort at the ratio of about 3:7.

Resampling and filtering were used to reduce noise and increase feature stability. Voxels in each CT image body were resampled to an isotropy voxel size of 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 mm3 to correct for different voxel spacing and section thickness between different centers. At the same time, the discretization of resampled image data was also used to reduce noise and increase the stability of features. All features were normalized using z-score normalization.

2.5. Feature extraction and establishment of the radiomics models

The radiomics workflow was shown in Figure 1. A total of 1439 quantitative imaging features were extracted from the VOIs, encompassing 262 first order statistics features delineating the distribution of voxel intensities, 28 3-dimensional features reflecting the shape and size of the region, and 1060 texture features quantifying heterogeneity differences in region characteristics such as gray run length, gray co-occurrence texture matrix (GCTM), gray level size zone matrix, gray level dependence matrix, and neighboring gray tone difference matrix (https://mics.huiyihuiying.com/).

Figure 1.

The radiomics analysis workflow. The radiomics workflow includes VOI segmentation, feature extraction, feature selection, model establishment (machine learning, radiomics model), analysis (ROC curve drawing, predictive performance validation and model testing).

The feature selection methods, including the variance threshold (variance threshold = 0.8), the SelectKBest, and, the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO), were used to reduce the redundant features. The optimal features obtained after screening were used for machine learning, and then the classification models were established. Our preexperiments showed that the relative standard deviation of SVM was low and the area under the curve (AUC) was high among KNN, DT, LR and SVM models. Based on the literature[22,23] and our preexperiments, we selected the commonly used support vector machine (SVM) model. The validation method was used to test the effectiveness of the models.

Two groups of models were established according to WHO/ISUP nuclear grading and T-staging. A total of 14 radiomics models were established, including 70 KeV, 100 KeV, 150 KeV, MEI, IMDI, VNC, and MEI + IMDI models of nuclear grading group and T-staging group, respectively.

2.6. Qualification and statistical analysis

Feature extraction, dimensionality reduction and modeling were carried out on the Radcloud platform. All statistical analyses were performed by R Studio (version 4.0.2, 2020-06-22) software package. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted and the area under the ROC curve (AUC) as well as sensitivity and specificity were calculated both in the training cohort and the validation cohort. Delong test was performed to evaluate the differences between the ROC curves. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to assess which model obtained the greatest net benefit.

3. Results

3.1. Results of nuclear grading group

3.1.1. Dimensionality reduction and selection of task-specific features.

The feature selection methods included the variance threshold (variance threshold = 0.8), SelectKBest, and LASSO in WHO/ISUP nuclear grading group. After reducing the dimensionality, a total of 31 optimal features were selected, including 11 firstorder, 7 GLDM, 2 GLRLM, 9 GLSZM, and 2 shape features. About 7 features were selected from the cortical phase, while 24 features were chosen from the medulla phase. Compared with cortical phase, medullary phase images provided more features to help nuclear classification.

The final number of selected features for the 70 KeV, 100 KeV, and 150 KeV models as well as the MEI, IMDI, VNC, and MEI + IMDI models were determined to be 6, 1, 6, 3, 4, 2, and 5 respectively.

Table 2 and Figure 2 displayed the radiomic features that were selected, along with their corresponding coefficients for each model.

Table 2.

Description of selected radiomics features with their associated feature group and filter for nuclear grading.

| Models for nuclear grading | Radiomic feature | Radiomic class | Filter | Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70 KeV | Kurtosis | Firstorder | A 70kv_original | 0.083 |

| Kurtosis | Firstorder | A 70kv_exponential | 0.014 | |

| LargeDependenceEmphasis | GLDM | V70kv_wavelet-LLH | −0.008 | |

| RunVariance | GLRLM | V70kv_wavelet-LLH | −0.049 | |

| LargeDependenceHighGrayLevelEmphasis | GLDM | V70kv_wavelet-LLH | −0.033 | |

| Kurtosis | Firstorder | V70kv_square | 0.044 | |

| 100 KeV | DependenceVariance | GLDM | V100KV_wavelet-LLH | −0.024 |

| 150 KeV | Kurtosis | Firstorder | A150KV_wavelet-LLL | −0.064 |

| Kurtosis | Firstorder | V150kv_square | 0.070 | |

| SmallAreaHighGrayLevelEmphasis | GLSZM | A150KV_wavelet-HHH | 0.040 | |

| Maximum3DDiameter | Shape | V150kv_original | 0.037 | |

| MinorAxisLength | Shape | V150kv_original | 0.041 | |

| Kurtosis | Firstorder | A150KV_logarithm | 0.152 | |

| MEI | LargeDependenceEmphasis | GLDM | Vmix_wavelet-LLH | 0.014 |

| LargeDependenceHighGrayLevelEmphasis | GLDM | Vmix_wavelet-LLH | 0.013 | |

| RunVariance | GLRLM | Vmix_wavelet-LLH | 0.038 | |

| VNC | HighGrayLevelZoneEmphasis | GLSZM | V VNC.N_wavelet-LLH | 0.010 |

| SmallAreaHighGrayLevelEmphasis | GLSZM | V VNC.N_wavelet-HHH | −0.012 | |

| IMDI | RobustMeanAbsoluteDeviation | Firstorder | A VNC_squareroot | −0.040 |

| DependenceVariance | GLDM | V VNC_wavelet-LLH | −0.070 | |

| MeanAbsoluteDeviation | Firstorder | V VNC_wavelet-LLL | 0.000 | |

| HighGrayLevelZoneEmphasis | GLSZM | A VNC_wavelet-HLL | −0.099 | |

| MEI + IMDI | MeanAbsoluteDeviation | Firstorder | V VNC_wavelet-LLL | −0.002 |

| HighGrayLevelZoneEmphasis | GLSZM | A VNC_wavelet-HLL | −0.010 | |

| Variance | Firstorder | V VNC_original | −0.061 | |

| DependenceVariance | GLDM | Vmix_wavelet-LLH | −0.038 | |

| InterquartileRange | Firstorder | V VNC_wavelet-LLL | −0.050 |

GLDM = Gray Level Dependence Matrix, GLRLM = Gray Level Run Length Matrix, GLSZM = Gray Level Size Zone Matrix

Figure 2.

Features extraction and dimensionality reduction for nuclear grading. A–G: LASSO algorithm (regression coefficient diagram) for feature extraction and dimensionality reduction in nuclear grading based on image features at 70 KeV, 100 KeV, 150 KeV, MEI, IMDI, VNC, and MEI + IMDI.

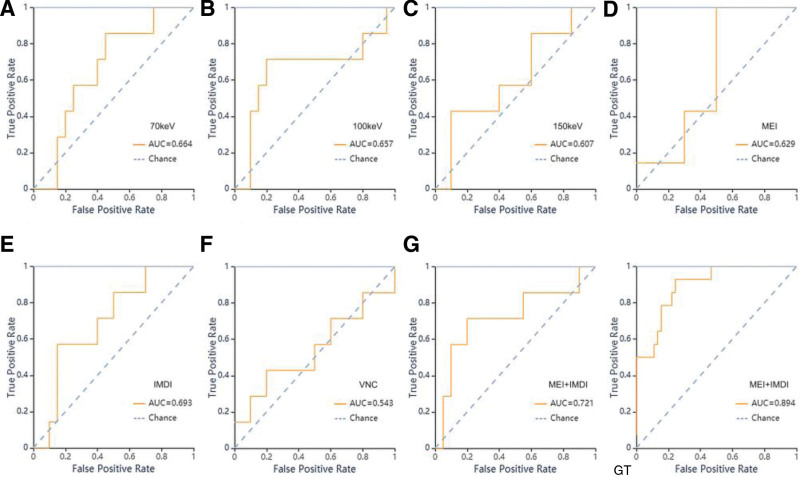

3.1.2. Results of ROC curve analysis and Delong test.

During SVM classifier training, the AUC values for the 70 KeV, 100 KeV, 150 KeV, MEI, IMDI, VNC and MEI + IMDI models were 0.64 (0.66), 0.73 (0.66), 0.97 (0.61), 0.64 (0.63), 0.94 (0.69), 0.77 (0.54), and, 0.89 (0.72) in the training (validation) cohort, respectively.

Among the mono-energy image models, the 70 KeV model exhibited superior classification efficacy. Both the AUC of 70 KeV and IMDI models surpassed that of MEI model. The MEI + IMDI model demonstrated optimal performance in the validation cohort, with an AUC value of 0.72, sensitivity of 0.71 and specificity of 0.70. As anticipated, the VNC model lacked categorical ability.

The performance metrics, including AUC value, 95% CI, sensitivity, specificity, and support value of the models developed for nuclear grading in both the training and validation cohorts are presented in Table 3 and Figure 3.

Table 3.

The results of AUC, 95 CI, sensitivity, specificity for nuclear grading.

| Classifiers | 70 KeV | 100KeV | 150KeV | MEI | IMDI | VNC | MEI + IMDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | AUC | 0.64 | 0.73 | 0.97 | 0.64 | 0.94 | 0.77 | 0.89 |

| 95 CI | 0.48–0.80 | 0.58–0.87 | 0.87–1.00 | 0.49–0.80 | 0.86–1.00 | 0.62–0.91 | 0.77–1.00 | |

| Sensitivity | 0.60 | 0.57 | 0.86 | 0.57 | 0.93 | 0.71 | 0.79 | |

| Specificity | 0.57 | 0.83 | 0.93 | 0.44 | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.80 | |

| Support | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | |

| Validation set | AUC | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.54 | 0.72 |

| 95 CI | 0.44–0.89 | 0.45–0.86 | 0.39–0.83 | 0.41–0.85 | 0.48–0.91 | 0.33–0.76 | 0.52–0.93 | |

| Sensitivity | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.71 | |

| Specificity | 0.70 | 0.85 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.80 | 0.50 | 0.70 | |

| Support | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

Figure 3.

ROC curves of SVM methods for classification in nuclear grading group. A–G: ROC curve of validation set of the 70 KeV, 100 KeV, 150 KeV, MEI, IMDI, VNC and MEI + IMDI models respectively. GT: ROC curve of training set in MEI + IMDI models.

The Delong test demonstrated that the MEI + IMDI model outperformed the 70 KeV, 100 KeV, 150 KeV, MEI and VNC models (P < .05) in the validation cohort with statistically significant differences. There were no significant differences in AUC values between the IMDI model and the MEI + IMDI model (Table 4).

Table 4.

The Delong test of the models’AUC for nuclear grading.

| MEI + IMDI vs other 6 models (AUC) | Validation set | P value |

|---|---|---|

| 70 KeV vs MEI + IMDI | 0.66 vs 0.72 | .033 |

| 100 KeV vs MEI + IMDI | 0.66 vs 0.72 | .008 |

| 150 KeV vs MEI + IMDI | 0.61 vs 0.72 | .001 |

| MEI vs MEI + IMDI | 0.63 vs 0.72 | .003 |

| IMDI vs MEI + IMDI | 0.69 vs 0.72 | .128 |

| VNC vs MEI + IMDI | 0.54 vs 0.72 | <.001 |

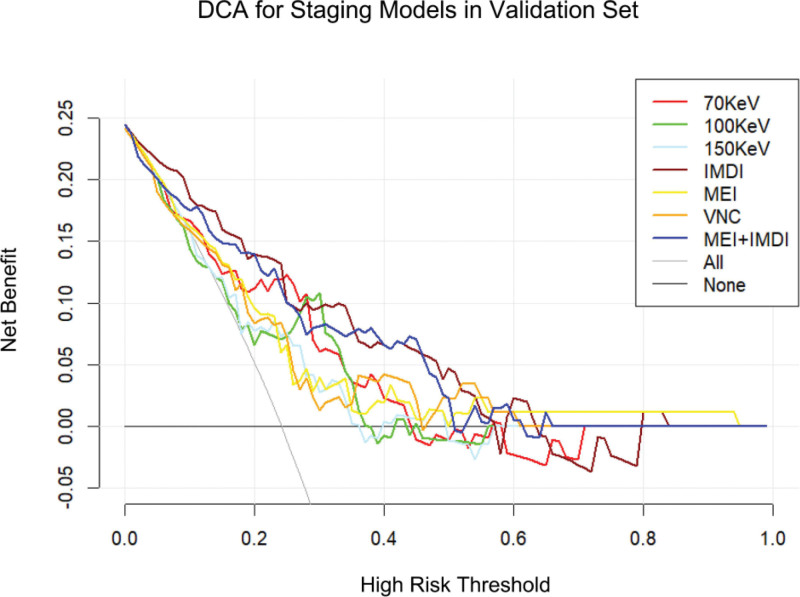

The DCA of the validation group for grading is illustrated in Figure 4. The findings indicate that the MEI + IDMI model enhances the ability to predict nuclear grade of ccRCC at a higher risk threshold, and both MEI + IDMI and IDMI models exhibit superior predictive performance compared to other models in the validation group.

Figure 4.

The decision curve analysis of various prediction models for identify high-grade ccRCC from low-grade ccRCC in validation set.

3.2. Results of T-stage grouping

3.2.1. Dimensionality reduction and selection of task-specific features.

The feature selection methods included the variance threshold (variance threshold = 0.8), SelectKBest, and the LASSO in T-staging group. After reducing the dimensionality, a total of 56 optimal features were selected for T-staging group, including 18 firstorder, 4 GLDM, 6 GLRLM, 26 GLSZM and 2 shape features. The number of selected features was 28 for both the arterial and venous phases.

The final number of selected features used for the 70 KeV, 100 KeV, 150 KeV, MEI, IMDI, VNC, and MEI + IMDI models were 9, 5, 5, 12, 12, 4, and, 9 respectively.

The radiomic features selected and their coefficient for each model and the final number of selected features were shown in Table 5 and Figure 5.

Table 5.

Description of the selected radiomic features with their associated feature group and filter for T-staging.

| Models for T-staging | Radiomic feature | Radiomic class | Filter | Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70 KeV | ZoneEntropy | GLSZM | A 70kv_wavelet-LHH | 0.001 |

| MajorAxisLength | Shape | A 70kv_original | 0.017 | |

| GrayLevelNonUniformity | GLSZM | A 70kv_wavelet-HHH | 0.032 | |

| ZoneEntropy | GLSZM | A 70kv_wavelet-HLH | 0.016 | |

| Skewness | Firstorder | V 70kv_wavelet-HHL | −0.055 | |

| ZoneEntropy | GLSZM | V 70kv_wavelet-LLH | 0.112 | |

| Maximum | Firstorder | A 70kv_squareroot | 0.034 | |

| HighGrayLevelZoneEmphasis | GLSZM | V70kv_wavelet-HHL | 0.084 | |

| DependenceVariance | GLDM | V70kv_wavelet-LLH | −0.041 | |

| 100 KeV | GrayLevelNonUniformity | GLSZM | A100kv_wavelet-HHH | 0.065 |

| Kurtosis | Firstorder | V 100KV_wavelet-HHL | 0.007 | |

| ZoneEntropy | GLSZM | V 100KV_wavelet-LHL | 0.054 | |

| SmallAreaHighGrayLevelEmphasis | GLSZM | A 100kv_wavelet-HHH | 0.035 | |

| Kurtosis | Firstorder | V 100KV_wavelet-HHH | 0.011 | |

| 150 KeV | Kurtosis | Firstorder | V 150kv_wavelet-HHL | 0.120 |

| ZoneEntropy | GLSZM | A 150KV_wavelet-LLH | 0.085 | |

| HighGrayLevelZoneEmphasis | GLSZM | V 150kv_wavelet-LHH | −0.091 | |

| SmallAreaHighGrayLevelEmphasis | GLSZM | A 150KV_wavelet-HHH | 0.059 | |

| HighGrayLevelZoneEmphasis | GLSZM | V 150kv_wavelet-HLL | −0.011 | |

| MEI | Kurtosis | Firstorder | V mix_wavelet-HHL | 0.004 |

| ZoneEntropy | GLSZM | V mix_wavelet-LHL | 0.029 | |

| Skewness | Firstorder | V mix_wavelet-HHL | −0.073 | |

| Kurtosis | Firstorder | V mix_wavelet-HHH | 0.030 | |

| MajorAxisLength | Shape | A mix_original | 0.060 | |

| ZoneEntropy | GLSZM | V mix_wavelet-HLH | 0.002 | |

| ZoneEntropy | GLSZM | V mix_wavelet-HHL | 0.029 | |

| ZoneEntropy | GLSZM | V mix_wavelet-HHH | 0.003 | |

| LargeDependenceLowGrayLevelEmphasis | GLDM | A mix_wavelet-LHH | 0.001 | |

| LargeDependenceLowGrayLevelEmphasis | GLDM | A mix_wavelet-HHH | 0.045 | |

| HighGrayLevelZoneEmphasis | GLSZM | V mix_wavelet-LHL | −0.047 | |

| HighGrayLevelZoneEmphasis | GLSZM | A mix_wavelet-HHL | 0.028 | |

| IDMI | ZoneEntropy | GLSZM | A VNC_wavelet-LHH | 0.086 |

| ZoneEntropy | GLSZM | A VNC_wavelet-HLH | 0.023 | |

| RunLengthNonUniformity | GLRLM | A VNC_exponential | 0.099 | |

| RunLengthNonUniformity | GLRLM | A VNC_gradient | 0.000 | |

| RunLengthNonUniformity | GLRLM | A VNC_square | 0.000 | |

| RunLengthNonUniformity | GLRLM | A VNC_lbp-2D | 0.000 | |

| Maximum | Firstorder | V VNC_wavelet-LHL | 0.070 | |

| Maximum | Firstorder | V VNC_wavelet-HHL | 0.020 | |

| Maximum | Firstorder | A VNC_wavelet-LLH | 0.013 | |

| Range | Firstorder | V VNC_logarithm | 0.023 | |

| HighGrayLevelRunEmphasis | GLRLM | V VNC_wavelet-LLL | −0.078 | |

| Maximum | Firstorder | V VNC_logarithm | 0.100 | |

| VNC | GrayLevelNonUniformity | GLSZM | A VNC.N_wavelet-LLH | 0.061 |

| HighGrayLevelZoneEmphasis | GLSZM | V VNC.N_wavelet-HHH | −0.049 | |

| Kurtosis | Firstorder | A VNC.N_wavelet-HHH | 0.077 | |

| HighGrayLevelZoneEmphasis | GLSZM | A VNC.N_wavelet-HLL | −0.100 | |

| HighGrayLevelZoneEmphasis | GLSZM | A VNC.N_wavelet-HLL | −0.207 | |

| MEI + IMDI | HighGrayLevelRunEmphasis | GLRLM | V VNC_wavelet-LLL | −0.048 |

| SmallAreaHighGrayLevelEmphasis | GLSZM | V mix_wavelet-LHL | −0.078 | |

| TotalEnergy | Firstorder | A VNC_square | 0.041 | |

| Maximum | Firstorder | A mix_squareroot | 0.039 | |

| ZoneEntropy | GLSZM | A mix_wavelet-HHH | 0.060 | |

| Maximum | Firstorder | A VNC_wavelet-LLH | 0.043 | |

| Minimum | Firstorder | V VNC_wavelet-LHL | −0.185 | |

| HighGrayLevelEmphasis | GLDM | V VNC_wavelet-LLL | −0.047 | |

| HighGrayLevelZoneEmphasis | GLSZM | V VNC_wavelet-HLL | −0.297 |

A = Artery phase, GLDM = Gray Level Dependence Matrix, GLRLM = Gray Level Run Length Matrix, GLSZM = Gray-Level Size Zone Matrix, V = venous phase

Figure 5.

Features extraction and dimensionality reduction for T-staging. A-G: LASSO algorithm (regression coefficient diagram) for feature extraction and dimensionality reduction in T-staging based on image features at 70 KeV, 100 KeV, 150 KeV, MEI, IMDI, VNC, and MEI + IMDI.

3.2.2. Results of ROC curve analysis and Delong test.

When training with SVM classifier, the AUC values of the 70 KeV, 100 KeV, 150 KeV, MEI, IMDI, VNC and MEI + IMDI models were 1 (0.64), 0.87 (0.66), 0.99 (0.61), 0.93 (0.60), 0.87 (0.70), 0.83 (0.593, and 0.96 (0.82) in the training (validation) cohort, respectively (Table 6). ROC curves of SVM methods to classification are shown in Figure 6.

Table 6.

The results of AUC, 95 CI, sensitivity, specificity for T-staging.

| Classifiers | 70 KeV | 100 KeV | 150 KeV | MEI | IMDI | VNC | MEI + IMDI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | AUC | 1.00 | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.96 |

| 95 CI | 0.80–0.97 | 0.75–0.98 | 0.91–1.00 | 0.85–1.00 | 0.75–1.00 | 0.70–0.96 | 0.91–1.00 | |

| Sensitivity | 1.00 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 1.00 | |

| Specificity | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.89 | |

| Support | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | |

| Validation set | AUC | 0.64 | 0.66 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.70 | 0.59 | 0.82 |

| 95 CI | 0.49–0.79 | 0.43–0.88 | 0.39–0.83 | 0.37–0.83 | 0.49–0.91 | 0.37–0.82 | 0.62–1.00 | |

| Sensitivity | 0.14 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.43 | 0.71 | |

| Specificity | 0.95 | 0.65 | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.50 | 0.80 | |

| Support | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

Figure 6.

ROC curves of SVM methods for classification in T-staging group. A–G: ROC curve of validation set of the 70 KeV, 100 KeV, 150 KeV, MEI, IMDI, VNC, MEI + IMDI models respectively. GT: ROC curve of training set of the MEI + IMDI model.

For the models based on different energy images, the AUC value of the MEI was the lowest, but when MEI combined IMDI, the MEI + IMDI model achieved the best performance, with the AUC value 0.96 (0.82) in the training (validation) cohort. The AUC value of 150 KeV model was lower than those of the 70 KeV, 100 KeV models.

As we expected the VNC model had the lowest AUC value among the 7 models.

The AUC, 95% CI, sensitivity, specificity and support value of models for T-staging in the training cohort and the validation cohort are shown in Table 6.

The Delong test compared the predictive performance of the 70 KeV, 100 KeV, 150 KeV, MEI, IMDI, and VNC models with that of the MEI + IMDI model. The results showed that the differences between models have statistical significance (P ≤ .001; Table 7).

Table 7.

The Delong-test of the models’AUC for T-staging.

| MEI + IMDI vs other 6 models (AUC) | Validation cohort | P value |

|---|---|---|

| 70 KeV vs MEI + IMDI | 0.64 vs 0.82 | <.001 |

| 100 KeV vs MEI + IMDI | 0.66 vs 0.82 | <.001 |

| 150 KeV vs MEI + IMDI | 0.61 vs 0.82 | <.001 |

| MEI vs MEI + IMDI | 0.60 vs 0.82 | <.001 |

| IMDI vs MEI + IMDI | 0.7 0 vs 0.82 | .001 |

| VNC vs MEI + IMDI | 0.50 vs 0.82 | <.001 |

The DCA of the validation group for T-staging showed that MEI + IDMI model could improve the ability to predict T-stage of ccRCC in a larger risk threshold, and MEI + IDMI and IDMI model in the validation group had higher prediction effect than other prediction models (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

The decision curve analysis of various prediction models for T-stage of ccRCC in validation set.

4. Discussion

DECT can perform multi-parameter imaging vs single-parameter of conventional CT, and Compared with the hybrid energy images of single energy computed tomography, DECT can obtain a series of VEI and IMDI, moreover, the images can be obtained with a radiation exposure not significantly different from that of single-energy CT.[24] Many studies had applied DECT based radiomics in the tumor staging and nuclear grading and had achieved good results.[16,19,25,26] VMI were recommended for routine use in DECT of the abdomen by the White Paper of the Society of Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance[27] and a multi-institutional consensus.[28,29] VMI had been shown to improve lesion detection at low KeV levels.[24] With the increase of energy, the diagnostic accuracy of renal lesions could decrease, 70 KeV VMI has the lowest noise magnitude and may provide the best trade-off between sensitivity and specificity.[30,31]Some studies considered 70 KeV VMI accepted as a relatively standard energy level for routine reconstruction.[24]

In this study, the radiomics models for nuclear grading and T-staging based on different VMI, IMDI, and MEI images obtained a certain value, The radomics model based on VMI obtained better results than MEI model. The AUC of 70 and 100 KeV models was larger than 150 KeV. This may lend credence to these standpoints.

IMDI can quantify the actual iodine concentration and indicate increased tumor angiogenesis.[32] Homayounieh F et al[33] compared the pathological results of liver lesions with dual-energy IMDI and found that the coincidence rate of IMDI detection results with postoperative pathological examination was higher than that of conventional CT. Wu et al[34] confirmed that radiomics analysis based on IMDI of DECT imaging could provide a relatively high diagnostic value for predicting microsatellite instability status in patients with colorectal cancer. This study showed the combined model of MEI + IMDI for nuclear grading and T-staging in this study achieved better performance in the validation cohort, with the AUC of 0.72 and 0.82, sensitivity of 0.71 and 0.71, and specificity of 0.70 and 0.80, respectively, the AUC of IMDI models were the next highest to combined model of MEI + IMDI. Among the models based on different energy images, the AUC of the MEI was the lowest, but when MEI combined IMDI, the MEI + IMDI model achieved the best performance. IMDI model is expected to play a bigger role in the diagnosis and treatment of ccRCC. This is similar to previous studies.

As we expected, VNC model has the lowest AUC among the models, this is because concentration of iodine can reflect the vascularization of various tissues and provides important information for diagnosis. Without information of iodine VNC provides limited information.

Several studies[22,23] had shown that SVM combined with quantitative MDCT texture analysis has the highest predictive performance in different machine learning based classifiers for distinguishing low-grade from high-grade ccRCC. Our results are similar to theirs, so our research mainly focuses on SVM for machine learning. Generally, radiomics features can be divided into 3 types, including firstorder statistics features, shape- and size-based features and textural features (calculated from gray level run-length and gray level co-occurrence texture matrices).

In our study, among all selected radiomics features, the number of texture features was the highest, with the number 1060/1439. The texture features showed higher discrimination ability. The reason for the good performance is that 3D texture features can provide the overall characteristics of tumor heterogeneity by analyzing the gray distribution of pixels or pixels in CT images and its relationship with gray level.[35] Radiomics is mainly composed of 3D texture features, and its prediction performance is significantly superior to morphological features and firstorder features.[36,37] Mayerhoefer et al[38] showed that radiomics could be used to describe tumor heterogeneity. According to previous studies, the risk of malignancy in high-grade tumors can increase with tumor size, and tumor size is significantly correlated with metastasis.[39] Shape features refer to the characteristics that describe the size and morphology of a region of interest, such as maximum 2-dimensional diameter, volume, and area. These parameters reflect information about the entire tumor shape. Our findings are consistent with this conclusion. Our study also has some limitations. Firstly, the sample size was relatively small and cases were not evenly distributed across different grades or stages. Secondly, the T-staging subgroups (T1–2 and T3–4) were coarse due to clinicians’ emphasis on other subgroups of T-staging (such as T1a and T1b). Finally, this study is limited to a single center and lacks external validation. In the future, multi-center studies should be carried out to enhance the generalizability of the model.

5. Conclusion

Radiomics models based on DECT have the potential to aid in nuclear grading and T-staging of ccRCC prior to surgery, thereby facilitating treatment strategies and prognosis assessment. This provides additional incremental value for the development and utilization of DECT.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft: Ning Wang, Xue Bing.

Writing—review & editing: Ning Wang.

Data curation: Xue Bing, Yuhan Li.

Funding acquisition: Jian Yao, Aimei Ouyang.

Methodology: Jian Yao, Dexin Yu.

Software: Zhengjun Dai.

Project administration: Aimei Ouyang.

Abbreviations:

- AUC

- the area under the curve

- ccRCC

- clear cell renal cell carcinoma

- DCA

- decision curve analysis

- DECT

- dual-energy CT

- DT

- decision tree

- GLDM

- gray level dependence matrix

- GLRLM

- gray level run length matrix

- GLSZM

- gray level size zone matrix

- IMDI

- iodine-based material decomposition images

- KNN

- K nearest neighbor

- LASSO

- the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator

- LR

- logistics regression

- MEI

- mixed energy image

- ROC

- receiver operating characteristic

- RSD

- the relative standard deviation

- SD

- standard deviation

- SVM

- support vector machine

- VMI

- virtual monoenergetic images

- VNC

- virtual noncontrasted

- VOI

- volume of interests

- X

- arithmetic mean of the calculated results.

This work was supported by the Jinan Clinical Medical Science and Technology Innovation Program (202019036) and the Central Guidance on Local Science and Technology Development Fund of Shandong Province (YDZX2021012).

The ethics committee of Jinan Central Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, approved this retrospective study. The ethics committee waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation. The study was carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

How to cite this article: Wang N, Bing X, Li Y, Yao J, Dai Z, Yu D, Ouyang A. Study of radiomics based on dual-energy CT for nuclear grading and T-staging in renal clear cell carcinoma. Medicine 2024;103:10(e37288).

Contributor Information

Ning Wang, Email: wn1919@126.com.

Xue Bing, Email: 503812189@qq.com.

Yuhan Li, Email: 510103533@qq.com.

Jian Yao, Email: yj8859@163.com.

Zhengjun Dai, Email: daizhengjun@huiyihuiying.com.

Dexin Yu, Email: ydx0330@sina.com.

References

- [1].Motzer RJ, Jonasch E, Agarwal N, et al. Kidney cancer, version3.2022, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20:71–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gong Z, Xie J, Chen L, et al. Integrative analysis of TRPV family to prognosis and immune infiltration in renal clear cell carcinoma. Channels (Austin). 2022;16:84–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kiliçarslan G, Eroğlu Y, Kiliçarslan A. Application of different methods used to measure the apparent diffusion coefficient of renal cell carcinoma on the same lesion and its correlation with ISUP nuclear grading. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2022;47:2442–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].van der Mijn JC, Al Hussein Al Awamlh B, Islam Khan A, et al. Validation of risk factors for recurrence of renal cell carcinoma: results from a large single-institution series. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0226285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Delahunt B, Eble JN, Egevad L, et al. Grading of renal cell carcinoma. Histopathology. 2019;74:4–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gang G, Xin M. The update interpretation of 2020 EAU renal cell carcinoma guideline (Part I)—progress in surgical treatment of renal cancer. Chin J Urol. 2020;41:575–7. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zhang Y, He D, Liu J, et al. Preoperative prediction of macrotrabecular-massive hepatocellular carcinoma through dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging-based radiomics. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:2001–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Shu J, Tang Y, Cui J, et al. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma: CT-based radiomics features for the prediction of Fuhrman grade. Eur J Radiol. 2018;109:8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Shahveranova A, Balli HT, Aikimbaev K, et al. Prediction of local tumor progression after microwave ablation in colorectal carcinoma liver metastases patients by MRI radiomics and clinical characteristics-based combined model: preliminary results [published online ahead of print]. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Paiar F, Gabelloni M, Pasqualetti F, et al. Correlation of pre- and post-radio-chemotherapy MRI texture features with tumor response in rectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2023;43:781–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yue Z, Wang X, Yu T, et al. Multi-parametric MRI-based radiomics for the diagnosis of malignant soft-tissue tumor. Magn Reson Imaging. 2022;91:91–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Liu Z, Wang S, Dong D, et al. The applications of Radiomics in precision diagnosis and treatment of oncology: opportunities and challenges. Theranostics. 2019;9:1303–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhou L, Zhang Z, Chen YC, et al. A deep learning-based radiomics model for differentiating benign and malignant renal tumors. Transl Oncol. 2019;12:292–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Parakh A, Lennartz S, An C, et al. Dual-energy CT images: pearls and pitfalls. Radiographics. 2021;41:98–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rapp JB, Biko DM, Barrera CA, et al. Current and future applications of thoracic dual-energy CT in children: pearls and pitfalls of technique and interpretation. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2020;41:433–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Li Z, Liu Z, Guo Y, et al. Dual-energy CT-based radiomics nomogram in predicting histological differentiation of head and neck squamous carcinoma: a multicenter study. Neuroradiology. 2022;64:361–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhou Y, Su G, Hu H, et al. Radiomics analysis of dual-energy CT-derived iodine maps for diagnosing metastatic cervical lymph nodes in patients with papillary thyroid cancer. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:6251–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Azour L, Ko JP, O’Donnell T, et al. Combined whole-lesion radiomic and iodine analysis for differentiation of pulmonary tumors. Sci Rep. 2022;12:11813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].An C, Li D, Li S, et al. Deep learning radiomics of dual-energy computed tomography for predicting lymph node metastases of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49:1187–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yang L, Sun J, Yu X, et al. Diagnosis of serosal invasion in gastric adenocarcinoma by dual-energy CT radiomics: focusing on localized gastric wall and peritumoral radiomics features. Front Oncol. 2022;12:848425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lambin P, Rios-Velazquez E, Leijenaar R, et al. Radiomics: extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:441–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bektas CT, Kocak B, Yardimci AH, et al. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma: machine learning-based quantitative computed tomography texture analysis for prediction of fuhrman nuclear grade. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nazari M, Shiri I, Hajianfar G, et al. Noninvasive Fuhrman grading of clear cell renal cell carcinoma using computed tomography radiomic features and machine learning. Radiol Med. 2020;125:754–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gentili F, Monteleone I, Mazzei FG, et al. Advancement in diagnostic imaging of thymic tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Shi C, Yu Y, Yan J, et al. The added value of radiomics from dual-energy spectral CT derived iodine-based material decomposition images in predicting histological grade of gastric cancer. BMC Med Imaging. 2022;22:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rajamohan N, Goyal A, Kandasamy D, et al. CT texture analysis in evaluation of thymic tumors and thymic hyperplasia: correlation with the international thymic malignancy interest group (ITMIG) stage and WHO grade. Br J Radiol. 2021;94:20210583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].De Cecco CN, Boll DT, Bolus DN, et al. White paper of the society of computed body tomography and magnetic resonance on dual-energy CT, part 4: abdominal and pelvic applications. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2017;41:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Patel BN, Alexander L, Allen B, et al. Dual-energy CT workflow: multi-institutional consensus on standardization of abdominopelvic MDCT protocols. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2017;42:676–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Euler A, Laqua FC, Cester D, et al. Virtual mono-energy images of dual-energy CT-impact on repeatability, reproducibility, and classification in radiomics. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:4710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Oostveen LJ, Boedeker KL, Balta C, et al. Technical performance of a dual-energy CT system with a novel deep-learning based reconstruction process: evaluation using an abdomen protocol. Med Phys. 2022;50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Schabel C, Patel B, Harring S, et al. Renal lesion characterization with spectral CT: determining the optimal energy for virtual monoenergy reconstruction. Radiology. 2018;287:874–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Lennartz S, Le Blanc M, Zopfs D, et al. Dual-energy CT-derived iodine maps: use in assessing pleural carcinomatosis. Radiology. 2019;290:796–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Homayounieh F, Singh R, Nitiwarangkul C, et al. Semiautomatic segmentation and radiomics for dual-energy CT: a pilot study to differentiate benign and malignant hepatic lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;215:398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wu J, Zhang Q, Zhao Y, et al. Radiomics analysis of iodine-based material decomposition images with dual-energy computed tomography imaging for preoperatively predicting microsatellite instability status in colorectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lubner MG, Smith AD, Sandrasegaran K, et al. CT texture analysis: definitions, applications, biologic correlates, and challenges. Radiographics. 2017;37:1483–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tian Q, Yan LF, Zhang X, et al. Radiomics strategy for glioma grading using texture features from multiparametric MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2018;48:1518–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Li Y, Huang X, Xia Y, et al. Value of radiomics in differential diagnosis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma and renal oncocytoma. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020;45:3193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Mayerhoefer ME, Materka A, Langs G, et al. Introduction to radiomics. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:488–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Jiang W, Shou J, Shi H, et al. Impact of primary tumor size on prognosis in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving cytoreductive nephrectomy: a population study of a Chinese center and the US SEER database. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2021;20:15330338211019507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]