INTRODUCTION

Modification of etiologic factors for HCC will dramatically affect the future modalities of surveillance in patients at risk of developing this tumor. Epidemiological trends of chronic liver diseases are expected to profoundly modify the approach to HCC surveillance, with an increase in virus-negative cases—mainly metabolic-related and alcohol-associated. In this scenario, the identification of more accurate screening tools and strategies aimed at increasing adherence to surveillance programs are urgently needed to maintain the benefit of surveillance.

In patients with established HCC, a comprehensive approach that takes into account liver-related features such as residual liver function and portal hypertension, and general fitness of the patient in addition to oncological characteristics, is essential to guide treatment. A hierarchical approach to the selection of the therapeutic option associated with the greatest survival benefit for a given patient represents a novel model that may modify the treatment paradigm of patients with HCC.

Liver transplantation (LT) represents the most rewarding treatment for HCC, as it allows to cure both the tumor and concurrent liver disease, although it may be burdened by liver cancer recurrence. Thus, an accurate assessment of the risk of recurrence is central to identify patients who might need enhanced post-LT surveillance, with the ultimate goal to identify earlier tumors and potentially improve patients’ prognosis.

HOW CHANGING EPIDEMIOLOGY OF CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE MAY IMPACT ON HCC SURVEILLANCE PROGRAMS?

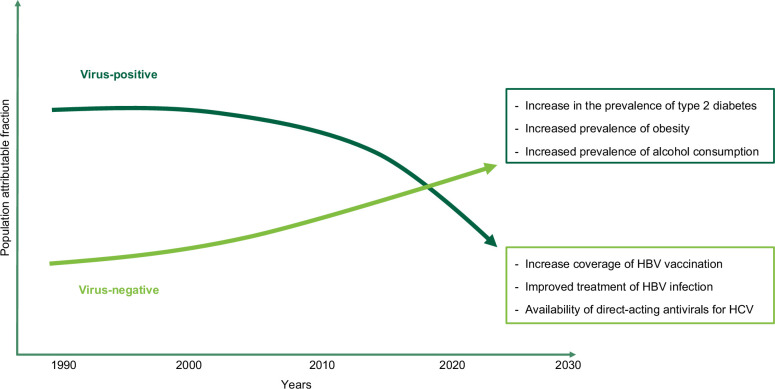

In more than 90% of cases, HCC occurs in patients with an underlying liver disease, most frequently cirrhosis.1 Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease and alcohol-associated liver disease are now considered, in the western world, the main etiologies of liver disease in patients with HCC, with a sharp decline of cases associated with chronic hepatitis virus infection.2 The main drivers of these epidemiological changes are represented by the epidemic of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus and by the increased prevalence of alcohol consumption, while the advent of direct-acting antivirals for the treatment of HCV infection and improved population coverage of HBV vaccination contributed to the decline of virus-related cases (Figure 1).3,4

FIGURE 1.

Trends of population attributable fraction of principal etiologic factors for HCC, with reasons for the observed modifications.

This changing epidemiology brings along some crucial questions related to inherent accuracy and actual applicability in the future of current HCC surveillance programs—ultrasound and alpha-fetoprotein every 6 months. As a fact, technical issues, such as poor ultrasound visualization of the hepatic parenchyma due to overweight and obesity, findings that are already present in 68.0% of patients with nonviral HCCs, will be more prevalent in the future, hampering the accuracy of examinations.1,5,6 Moreover, alpha-fetoprotein, which is normal in 62.8%–92.5% of patients who will represent the future focus of surveillance, is expected to modestly contribute to the effectiveness of surveillance.7 The actual feasibility of surveillance programs will also be uncertain, as the population of patients with metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease is large, and in these patients, HCC may develop in the absence of cirrhosis. Thus, without additional, accurate features that may help adequately select high-risk patients it is likely that sustainability of surveillance programs may be at risk.8 Lastly, adherence to surveillance programs will likely represent a main issue, as in patients with alcohol-associated liver disease, it is suboptimal—3-fold lower than in patients with other etiologies—with a negative reflex on oncological stage at diagnosis, the likelihood of access to curative treatments, and ultimately patients’ survival.9,10

These findings underscore an urgent need for accurate and easily available tools to enhance the feasibility of HCC surveillance in the future. The use of abbreviated magnetic resonance imaging (AMRI) protocols is an appealing and promising surveillance modality that may obviate to the technical limitations of ultrasound in patients with central obesity. This technique exploits the information provided by T1-weighted and T2-weighted images and diffusion-weighted sequences—even without contrast—in a reduced acquisition time (ie, <10 minutes).11 In a retrospective study including a large population with cirrhosis due to metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease, noncontrast AMRI had a lower diagnostic sensitivity (61.5%, 95% CI: 34.4%–83%) compared to dynamic-AMRI (84.6%, 95% CI: 60.8%–95.1%) and hepatobiliary phase-AMRI (80.8%, 95% CI: 53.6%–93.9%), with specificity above 95.0% for all the sets, and with a simulated life-year gain of 3–12 months compared with ultrasound, against an incremental cost of <12,000 USD.12 How these results may translate into clinical practice is unknown: both financial sustainability and patients’ compliance still need to be adequately assessed, and data from prospective, randomized surveillance studies comparing surveillance efficacy and effectiveness of AMRI against ultrasound are missing. Lastly, strategies aimed at improving patients’ adherence to surveillance programs still need to be identified, as there is evidence that even mailed outreach strategies providing information about HCC risk and the relevance of surveillance, and direct contact of nonadherent patients, minimally increased patients participation in surveillance programs.13

IMPACT OF LIVER FUNCTION AND PORTAL HYPERTENSION ON THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS AND PROGNOSIS OF PATIENTS WITH HCC

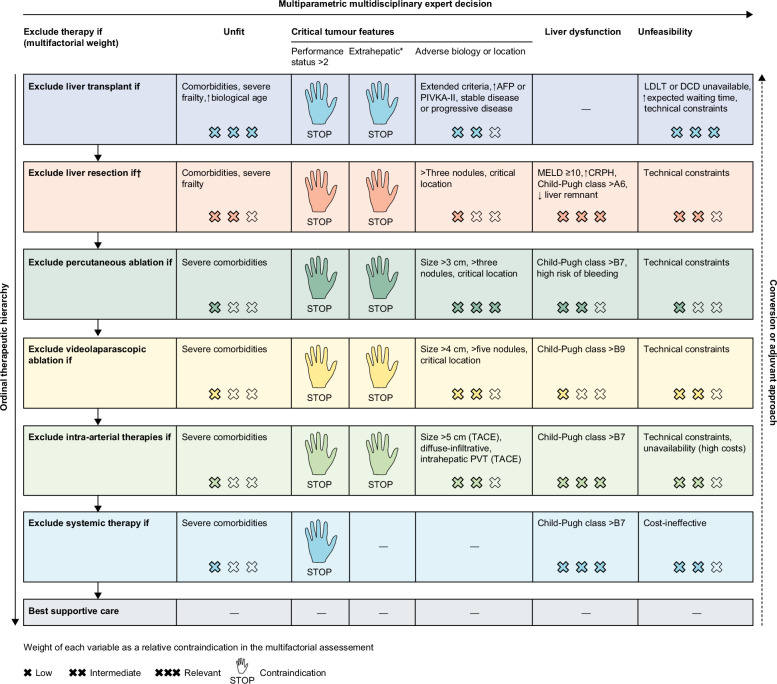

Progressive hepatic decompensation represents the main competitive risk of death in patients with HCC, and therefore, both evaluation of residual liver function and assessment of the presence and degree of portal hypertension plays a fundamental role in the selection of treatment and in the prediction of prognosis. Application of a holistic approach that comprehensively considers liver function, portal hypertension, and general fitness of the patient with HCC to circumvent the limitations inherent to rigid, stage-based therapeutic algorithms and to enhance the role of survival benefit provided by the selected treatment in a given patient represents the most promising line of action.14,15 Indeed, in patients with HCC, treatment selection should follow a hierarchical approach, with the potential survival advantage dictated by one treatment over competitive treatments, driving the selection of the therapeutic option for a determined patient (Figure 2).14

FIGURE 2.

The concept of multiparametric therapeutic hierarchy guiding treatment options in patients with HCC. *Extrahepatic metastases, invasion of the main trunk of the portal vein or inferior vena cava. †Mini-invasive approach offers a prognostic advantage (decreased risk of postoperative liver failure) and decreases the impact of liver dysfunction by one cross. Reprinted with permission from Vitale et al.14 Abbreviations: AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; CRPH, clinically relevant portal hypertension; DCD, donor after circulatory death; LDLT, living donor liver transplantation; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; PIVKA-II, protein induced by vitamin-K absence-II; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

In order to assess liver function, the albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade represents a simple and readily available parameter that helps identify patients who may be unsuitable for oncological treatment due to insufficient liver functional reserve.16 The ALBI grade obviates the subjective assessment of parameters of the Child-Pugh classification, such as ascites and encephalopathy, and proved to be able to identify the subclasses of patients who may not derive a substantial survival benefit from various treatments, including surgery and loco-regional therapies, thus representing a valuable decision-making aid in clinical practice.16 Noteworthy, the ALBI grade also helps stratify patients receiving systemic treatment: a subanalysis of the atezolizumab/bevacizumab registration study has shown that patients with an ALBI grade 1 benefit most from atezolizumab/bevacizumab compared to sorafenib (overall survival HR ALBI grade 1: 0.50, 95% CI: 0.35–0.72; ALBI grade 2: 0.92, 95% CI: 0.66–1.29), while a recent meta-analysis of real-world studies showed that patients with an ALBI grade >2 treated with atezolizumab/bevacizumab have a dismal prognosis as compared to those with lower ALBI grades (overall survival: 8.3±11.4 vs. 3.3 ± 5.0 months).17,18

Portal hypertension is another relevant clinical issue that needs to be adequately assessed when planning treatment for HCC, as the presence of esophageal varices identifies patients with worse prognosis independently of the degree of liver dysfunction, etiology of liver disease, HCC stage, and treatment modality.9,19 Moreover, the presence of clinically significant portal hypertension is associated with a 2- to 3-fold increase in the risk of mortality at 3 and 5 years after surgery for HCC, with a 3-fold increase in the risk of clinical decompensation.20 Lastly, patients with HCC and a prior bleeding episode less frequently receive prophylaxis of rebleeding than patients without HCC (77% vs. 89%, p=0.009), in particular, patients with advanced stage tumors (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stages C and D: 66% vs. stages 0, A, and B: 96%; p<0.001), and in these patients lack of secondary prophylaxis represents an independent predictor of death.21 Thus, endoscopic screening for esophageal varices represents a mandatory part of the clinical work-up of these patients; independently of planned oncological treatment and bleeding or rebleeding, prophylaxis must be implemented in all patients in order to improve their prognosis.

ASSESSMENT OF HCC RECURRENCE IN PATIENTS WHO UNDERWENT TRANSPLANT

HCC represents a growing indication for LT, with approximately 25% of patients listed with HCC both in the United States and Europe.22,23 LT for patients with HCC within predefined limits, such as the Milan criteria, is associated with a 5-year survival of approximately 70%, although disease recurrence is between 10% and 20% and portends a poor prognosis, often determined by limited therapeutic options.24–26 As the goal of universal absence of recurrence is unreachable, the risk of post-LT recurrence has to be balanced with the risk of death without LT in the same patient, taking into account the survival benefit provided by LT over other potential treatments in the single patient.27

In order to guide surveillance for HCC recurrence, which on average occurs 13–21 months after LT, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines indicate a strategy with imaging and alpha-fetoprotein every 3–6 months for the first 2 years and every 6–12 months thereafter, while the International Liver Transplant Society recommends abdominal and chest imaging with serial alpha-fetoprotein measurement every 3 months for 3 years after LT.28,29 However, these indications are mainly based on experts’ opinion and have the drawback of being monotonous rather than tailored on patients’ characteristics. In clinical practice, physicians tend to prefer grading surveillance on the perceived risk of the individual patient, basing their judgment mainly on tumor characteristics.30

Several scoring systems that include pre-LT and post-LT factors, such as size and number of lesions, presence of microvascular invasion, serum alpha-fetoprotein, and immunosuppressive regimen, have been proposed to guide post-LT surveillance, although no prospective studies adequately addressed this issue.31 The Risk Estimation of Tumor Recurrence After Transplant score, which includes number and size of viable tumors on explant, microvascular invasion, and alpha-fetoprotein, is based on retrospective data from multicenter cohorts and has been validated both in patients beyond the Milan criteria and in independent cohorts.32 Recently, the REcurrent Liver cAncer Prediction ScorE was devised in a US multicenter population of 4981 patients transplanted for HCC and validated in a population of 1160 recipients of LT from 5 European centers.33 The REcurrent Liver cAncer Prediction ScorE score includes maximum alpha-fetoprotein, neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio, pathologic maximum HCC diameter, microvascular and macrovascular invasion, and tumor differentiation, with an accuracy of 0.76–0.78 in the training and internal validation cohorts, and of 0.75–0.77 in the external validation cohort, and has the merit of applying machine learning algorithm with stratification of the prognostic determinants by means of classification and regression tree model.33 However, despite these positive aspects, this and other scores provide just a fairly good overall prediction of recurrence and are still mainly based on morphologic tumor characteristics and on weak surrogates of tumor biology, such as alpha-fetoprotein.26 Overall, they lack an in-depth biological characterization that may help better assess the potential aggressiveness of recurrence and, therefore, guide surveillance in the individual patient.

LT has the benefit of providing sufficient material to perform molecular testing to identify gene expression signatures associated with recurrence, potentially allowing to tailor post-LT surveillance: in a large series of patients outside Milan criteria, gene signatures of progenitor markers—CK19 and S2—predicted recurrence and prognosis.34 Furthermore, a deeper characterization of the immune milieu of the explanted liver, assessing the interaction between the local immune response and HCC might help better understand the biological interplay between the host and cancer, possibly predicting the risk of recurrence and eventually guiding treatment. In this regard, previous studies have shown that evaluation of immune function on peripheral blood independently predicted HCC recurrence following LT.35 Lastly, the detection of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) represents an appealing option in this regard, as they demonstrated their predictive value in patients outside the Milan criteria and in those with no detectable CTC before LT and negative tumor serological biomarkers.36,37 As CTC may be positive before recurrence is detected by imaging, serial assessment of CTC following LT may be useful to guide the intensity of surveillance so as to identify recurrence at an earlier stage.

In the absence of prospective studies that may still be limited by size and by an a priori selection of putative variables, exploration of large databases of transplanted patients—possibly with the aid of artificial intelligence—may consent to identify disease biological clusters that can be exploited to adequately stratify risk of recurrence and surveillance strategies in the future.

CONCLUSIONS

Changes in etiologic factors for HCC are already modifying the clinical characteristics of the population at risk of development of this tumor, with an increase in the proportion of patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease without cirrhosis. However, despite an expected increase in the absolute number of patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease who will develop HCC, the overall proportion of patients developing HCC among noncirrhotic patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease will still be low. Therefore, as suggested by the current American Association for the Study of Liver Disease HCC practice guidance, features that may help identify higher-risk patients, such as concurrent alcohol use, diabetes, or other co-factors, or factors that may provide protection toward the development of HCC such as diabetes medication or antiplatelet therapies, within this very large population are eagerly needed to refine surveillance.8,38–40 These changes will also affect the eligibility of patients to various treatments for HCC, and in particular may deeply impact on both eligibility for LT and systemic treatments. Lastly, the efficacy of newer systemic therapies for HCC is expected to increase the proportion of patients who may be enabled to undergo curative treatments, including LT, due to their capacity to downstage even advanced tumors, and therefore accurate models to predict the likelihood of recurrence are required to adequately select patients who may benefit most from LT and to personalize post-LT surveillance.

Acknowledgments

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Edoardo G. Giannini advises and is on the speakers’ bureau for Roche and MSD-Eisai. He advises AstraZeneca. He consults for GSK.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; AMRI, abbreviated magnetic resonance imaging; CTCs, circulating tumor cells; LT, liver transplantation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Garuti F, Neri A, Avanzato F, Gramenzi A, Rampoldi D, Rucci P, et al. The changing scenario of hepatocellular carcinoma in Italy: An update. Liver Int. 2021;41:585–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vitale A, Svegliati-Baroni G, Ortolani A, Cucco M, Dalla Riva GV, Giannini EG, et al. Epidemiological trends and trajectories of MAFLD-associated hepatocellular carcinoma 2002-2033: The ITA.LI.CA database. Gut. 2023;72:141–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung RT. A watershed moment in the treatment of hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:273–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Estes C, Anstee QM, Arias-Loste MT, Bantel H, Bellentani S, Caballeria J, et al. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016-2030. J Hepatol. 2018;69:896–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Poggio P, Olmi S, Ciccarese F, Di Marco M, Rapaccini GL, Benvegnù L, et al. Factors that affect efficacy of ultrasound surveillance for early stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1927–33.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong LL, Reyes RJ, Kwee SA, Hernandez BY, Kalathil SC, Tsai NC. Pitfalls in surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma: How successful is it in the real world? Clin Mol Hepatol. 2017;23:239–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giannini EG, Sammito G, Farinati F, Ciccarese F, Pecorelli A, Rapaccini GL, et al. Determinants of alpha-fetoprotein levels in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: Implications for its clinical use. Cancer. 2014;120:2150–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plaz Torres MC, Bodini G, Furnari M, Marabotto E, Zentilin P, Strazzabosco M. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Universal or selective? Cancers (Basel). 2020;12:1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mancebo A, González-Diéguez ML, Navascués CA, Cadahía V, Varela M, Pérez R, et al. Adherence to a semiannual surveillance program for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reggidori N, Bucci L, Santi V, Stefanini B, Lani L, Rampoldi D, et al. Landscape of alcohol-related hepatocellular carcinoma in the last 15 years highlights the need to expand surveillance programs. JHEP Rep. 2023;5:100784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ronot M, Nahon P, Rimola J. Screening of liver cancer with abbreviated MRI. Hepatology. 2023;78:670–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vietti Violi N, Lewis S, Liao J, Hulkower M, Hernandez-Meza G, Smith K, et al. Gadoxetate-enhanced abbreviated MRI is highly accurate for hepatocellular carcinoma screening. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:6003–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singal AG, Tiro JA, Murphy CC, Marrero JA, McCallister K, Fullington H, et al. Mailed outreach invitations significantly improve hcc surveillance rates in patients with cirrhosis: A randomized clinical trial. Hepatology. 2019;69:121–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vitale A, Cabibbo G, Iavarone M, Viganò L, Pinato DJ, Ponziani FR, et al. Personalised management of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A multiparametric therapeutic hierarchy concept. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:e312–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaffe A, Taddei TH, Giannini EG, Ilagan-Ying YC, Colombo M, Strazzabosco M. Holistic management of hepatocellular carcinoma: The hepatologist’s comprehensive playbook. Liver Int. 2022;42:2607–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demirtas CO, D’Alessio A, Rimassa L, Sharma R, Pinato DJ. ALBI grade: Evidence for an improved model for liver functional estimation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. JHEP Rep. 2021;3:100347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kudo M, Finn RS, Cheng AL, Zhu AX, Ducreux M, Galle PR, et al. Albumin-bilirubin grade analyses of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sorafenib in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: A post hoc analysis of the phase III IMbrave150 Study. Liver Cancer. 2023;12:479–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasta A, Calabrese F, Jaffe A, Labanca S, Marenco S, Pieri G, et al. Safety and efficacy of atezolizumab/bevacizumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and impaired liver function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Liver Cancer. 2023. doi: 10.1159/000533991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giannini EG, Risso D, Testa R, Trevisani F, Di Nolfo MA, Del Poggio P, et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of the presence of esophageal varices in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1378–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berzigotti A, Reig M, Abraldes JG, Bosch J, Bruix J. Portal hypertension and the outcome of surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma in compensated cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2015;61:526–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ripoll C, Genescà J, Araujo IK, Graupera I, Augustin S, Tejedor M, et al. Rebleeding prophylaxis improves outcomes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. A multicenter case-control study. Hepatology. 2013;58:2079–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang JD, Larson JJ, Watt KD, Allen AM, Wiesner RH, Gores GJ, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma is the most common indication for liver transplantation and placement on the waitlist in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:767–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Müller PC, Kabacam G, Vibert E, Germani G, Petrowsky H. Current status of liver transplantation in Europe. Int J Surg. 2020;82S:22–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabrizian P, Holzner ML, Mehta N, Halazun K, Agopian VG, Yao F. Ten-year outcomes of liver transplant and downstaging for hepatocellular carcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2022;157:779–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bzeizi KI, Abdullah M, Vidyasagar K, Alqahthani SA, Broering D. Hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence and mortality rate post liver transplantation: Meta-analysis and systematic review of real-world evidence. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:5114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabiee A, Miller JB. HCC in peri-transplant period: What a gastroenterologist needs to know. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2023;22:7–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cillo U, Vitale A, Volk ML, Frigo AC, Grigoletto F, Brolese A, et al. The survival benefit of liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:642–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berenguer M, Burra P, Ghobrial M, Hibi T, Metselaar H, Sapisochin G. Posttransplant management of recipients undergoing liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Working Group Report From the ILTS Transplant Oncology Consensus Conference. Transplantation. 2020;104:1143–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benson AB, D’Angelica MI, Abbott DE, Anaya DA, Anders R, Are C. Hepatobiliary Cancers, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:541–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim NJ, Rozenberg-Ben-Dror K, Jacob DA, Rich NE, Singal AG, Aby ES. Provider attitudes toward risk-based hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:183–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffman D, Mehta N. Recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma following liver transplantation. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15:91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehta N, Heimbach J, Harnois DM, Sapisochin G, Dodge JL, Lee D, et al. Validation of a isk Estimation of Tumor Recurrence After Transplant (RETREAT) Score for hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplant. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tran BV, Moris D, Markovic D, Zaribafzadeh H, Henao R, Lai Q, et al. Development and validation of a REcurrent Liver cAncer Prediction ScorE (RELAPSE) following liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: Analysis of the US Multicenter HCC Transplant Consortium. Liver Transpl. 2023;29:683–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miltiadous O, Sia D, Hoshida Y, Fiel MI, Harrington AN, Thung SN, et al. Progenitor cell markers predict outcome of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond Milan criteria undergoing liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2015;63:1368–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng JW, Shi YH, Fan J, Huang XW, Qiu SJ, Xiao YS, et al. An immune function assay predicts post-transplant recurrence in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:1445–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahn JC, Teng PC, Chen PJ, Posadas E, Tseng HR, Lu SC, et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells and their implications as a biomarker for diagnosis, prognostication, and therapeutic monitoring in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2021;73:422–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang PX, Xu Y, Sun YF, Cheng JW, Zhou KQ, Wu SY, et al. Detection of circulating tumour cells enables early recurrence prediction in hepatocellular carcinoma patients undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2021;41:562–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singal AG, Llovet JM, Yarchoan M, Mehta N, Heimbach JK, Dawson LA, et al. AASLD Practice Guidance on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2023;78:1922–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Plaz Torres MC, Jaffe A, Perry R, Marabotto E, Strazzabosco M, Giannini EG. Diabetes medications and risk of HCC. Hepatology. 2022;76:1880–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lai Q, De Matthaeis N, Finotti M, Galati G, Marrone G, Melandro F. The role of antiplatelet therapies on incidence and mortality of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Clin Invest. 2023;53:e13870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]