Abstract

Objective

High-risk pregnancy (HRP) conditions such as gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), hypertension (HTN), and peripartum depression (PPD) affect maternal and neonatal health. Patient engagement is critical for effective HRP management (HRPM). While digital technologies and analytics hold promise, emerging research indicates limited and suboptimal support offered by the highly prevalent pregnancy digital solutions within the commercial marketplace. In this article, we describe our efforts to develop a portfolio of digital products leveraging advances in social computing, data science, and digital health.

Methods

We describe three studies that leverage core methods from Digilego digital health development framework to (1) conduct large-scale social media analysis (n = 55 301 posts) to understand population-level patterns in women’s needs, (2) architect a digital repository to enable women curate HRP related information, and (3) develop a digital platform to support PPD prevention. We applied a combination of qualitative coding, machine learning, theory-mapping, and programmatic implementation of theory-linked digital features. Further, we conducted preliminary testing of the resulting products for acceptance with sample of pregnant women for GDM/HTN information management (n = 10) and PPD prevention (n = 30).

Results

Scalable social computing models using deep learning classifiers with reasonable accuracy have allowed us to capture and examine psychosociobehavioral drivers associated with HRPM. Our work resulted in two digital health solutions, MyPregnancyChart and MomMind are developed. Initial evaluation of both tools indicates positive acceptance from potential end users. Further evaluation with MomMind revealed statistically significant improvements (P < .05) in PPD recognition and knowledge on how to seek PPD information.

Discussion

Digilego framework provides an integrative methodological lens to gain micro-macro perspective on women’s needs, theory integration, engagement optimization, as well as subsequent feature and content engineering, which can be organized into core and specialized digital pathways for women engagement in disease management.

Conclusion

Future works should focus on implementation and testing of digital solutions that facilitate women to capture, aggregate, preserve, and utilize, otherwise siloed, prenatal information artifacts for enhanced self-management of their high-risk conditions, ultimately leading to improved health outcomes.

Keywords: women’s health, high-risk pregnancy, digital health, social media

Introduction

Maternal health is of significant importance for individuals, families, and societies as a whole. Maternal health refers to the health of women during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period, as well as the health of the newborn.1–4 The United Nations has included maternal health as one of the sustainable development goals, which aims to enhance investments that address maternal mortality, access to reproductive health services, and overall women’s health disparities.2 In line with this effort, the National Institutes of Health has launched their program, Implementing a Maternal health and PRegnancy Outcomes Vision for Everyone (IMPROVE) to reduce preventable causes of maternal deaths and improve health for women before, during, and after delivery with special emphasis on health disparities.5

American women have the greatest risk of dying from high-risk pregnancy (HRP) complications among 11 high-income countries.5 Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), hypertension (HTN), and peripartum depression (PPD) are some of the most common medical disorders of HRPs. It is estimated that 8%-14% of pregnancies (depending on diagnostic criteria) are complicated with any type of diabetes and that approximately 86% of these cases are GDM.6,7 GDM affects more than 20 million live births, or approximately one in six births, worldwide (8-10). Pregnancy complications of GDM include preeclampsia (9.8%-18%), development of overt type 2 diabetes mellitus (70%) and cesarean section (17%-25%). Other complications include vascular dysfunction, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, and ischemic heart disease.8,9 When a pregnancy is associated with new- onset HTN, this can lead to preeclampsia, which occurs after 20 weeks of pregnancy and frequently near term. In the United States, preeclampsia has seen a 7-fold increase over the past two decades.10 Pregnancy complications of HTN in pregnancy include fetal growth restriction, oligohydramnios, placental abruption, non-reassuring fetal status, and spontaneous or medically indicated preterm delivery. HTN contribute to 16% of all maternal deaths.10,11 Similarly, PPD is a serious public health problem that affects a significantly high number (approximately 10%-15%) of peripartum women.12 PPD is associated with pregnancy complications such as low birth weight and preterm births.12,13 Women with PPD may also forego recommended prenatal checkups, immunization schedules for the baby, and well-baby check-ups.14 If left untreated, PPD can result in longer and more intense episodes of depression for the mother, and later on with cognitive and behavioral issues for the baby.15,16 In addition to the health risks, GDM, HTN, and PPD are among the leading cost drivers in adult women based on the highest cost reported, thereby increasing the overall economic burden of pregnancy on the US health care system.17–19

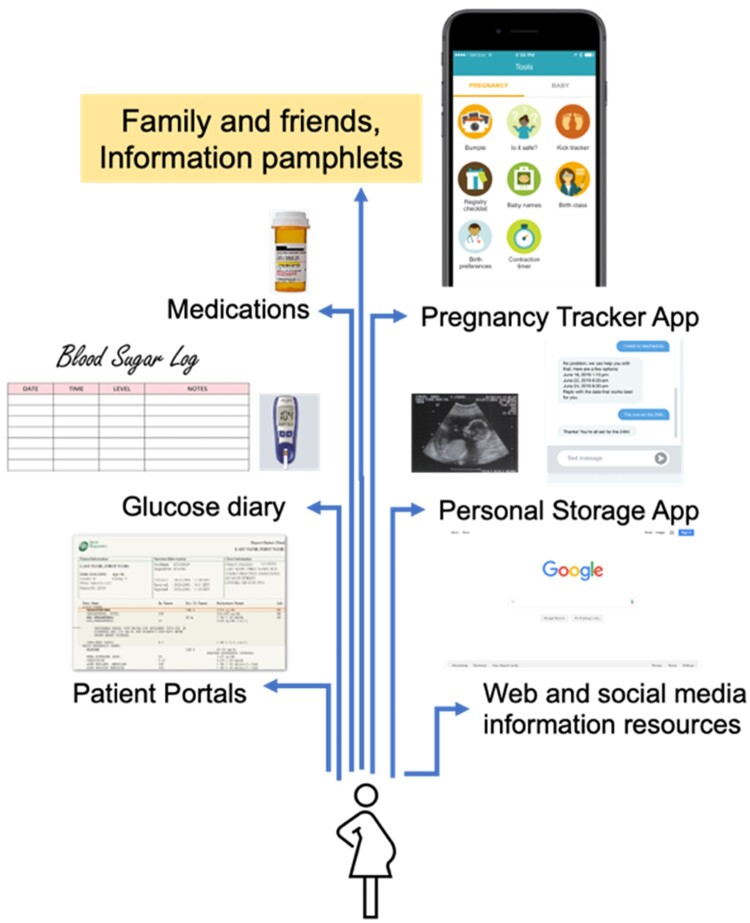

Outcomes of these HRPs are heavily dependent on active patients’ engagement in their pregnancy. Along with close fetal surveillance, maternal behavior modification is often seen as an effective strategy for HRP management (HRPM).20,21 For instance, for GDM, modified dietary interventions, exercise, glucose monitoring, and/or medications result in improved outcomes in maternal glycemic control and birth outcomes.22–24 As shown in Figure 1, oftentimes, critical information needed for patient engagement is distributed in the form of prenatal ultrasounds, discharge summary, lab reports in paper and electronic formats across personal health records, text messages, and individual websites (eg, educational resources). Such scattered and incoherent HRP information overload coupled with the steep learning curve associated with sustaining behavior modifications, and conflicting information resources (eg, physician recommendations, social media influencers) lead to response fatigue, limiting their self-efficacy and engagement in GDM.25,26 Recent trends highlight the utility of digital health as a promising solution to the increasing prevalence and complexity in engaging patients in health behaviors across the spectrum (eg, medication adherence, nutrition).27–32

Figure 1.

Patient-facing information resources for high-risk pregnancies with gestation diabetes mellitus.

While the current digital market place for women is crowded,33–36 there are hardly any solutions focused on integrative HRPM, let alone digitally inclusive disparities-mending personalized knowledge ecosystems.37 Little is known about mechanisms through which multilevel inter- and intra-personal factors, individualized knowledge resources, and theory-driven behavior change techniques can be packaged into comprehensible, engaging, and effective digital health solutions for enhancing maternal health.28,38 New approaches are needed that model the dynamics of the social context (eg, family ties, social influence) and individual factors (eg, health beliefs, cognitive heuristics) affecting critical decision making and opinion formation, to develop interventions that drive patient activation and engagement in effective utilization of digital platforms for HRPM.29 In addition, few digital health development frameworks facilitate cross-disciplinary integration beyond computational programming and oftentimes competing interests involved in design choices and feature trade-offs affects community-engaged technology development efforts.30,31 This lack of consideration and accommodation poses a risk for not only the failure of these technologies, but their failure to address women’s needs, importantly, especially the specialized needs of populations plagued with health disparities (eg, Hispanic women who are at the highest risk for GDM).39,40 To fill these gaps, in this article, we present and apply Digilego, a novel digital health development framework,41,42 which integrates advances in digital health and data science through a combination of theory-guided qualitative research, advances in social computing, and patient engagement models.

Methods

Digilego framework

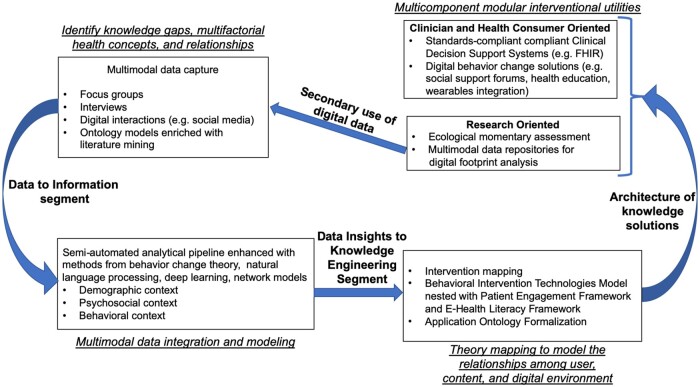

The overview of our generalized methodological framework, Digilego, is illustrated in Figure 2. Digilego facilitates the development and integration of individual Digilego building blocks to form a patient-oriented digital health solution.41,42 The unique features of these Digilego blocks are their reusability and customization abilities according to care context. These Digilego blocks can be put together to build digital health solutions that are modular, flexible and extensible, yet comprehensive. Such compartmentalized design architecture of the Digilego framework allowed us to facilitate customization of health education, harness machine-based querying, integrate digital engagement tactics, and adopt theory-driven techniques that ultimately enable the development of women-empowering flexible digital health solutions that can be used and modified across the care continuum for efficient care coordination and self-health management. Our Digilego framework is theory-guided: drawing links between behavior change theories, naturalistic decision making models, and multilevel inter- and intrapersonal influences on HRPM; empirically informed: needs gathering based on large-scale population level social listening among diverse populations as well as qualitatively enriched contextual inquiry using interviews with pregnant women from different ethnic groups and diverse income groups, thereby encompassing digital footprints and real-world evidence, inclusive: community engagement through interviews to obtain perspectives of women to understand individual-level, interpersonal, and health system-level factors affecting their engagement in perinatal health management, translational: providing guided learning artifacts responsive to patient care contexts in digital settings.

Figure 2.

High-level overview of Digilego modular architecture and design pipeline.

We have instantiated Digilego to develop a portfolio of digital health technologies to enable patient engagement in prevention and management of high-risk conditions during peripartum period in a series of studies described in this article. In Study 1, we focused on gathering population needs for PPD prevention and management, in Study 2, we architected a specialized personal health library for management of GDM and HTN, and in Study 3 we developed and tested a state-of-the art digital tool for prevention of PPD. We adopted a mixed methods approach across the three studies utilizing multiple methodological components outlined in Figure 2. These methods include, focus groups, semi-structured interviews, semi-automated methods of online peer interactions, theory mapping using Behavioral Interventions Technology (BIT) model43 and optimizing digital experiences using Patient Engagement Framework (PEF)44 which we describe below in detail. In order to enrich our understanding of women’s needs, we took a phased approach, starting with large-scale social media analysis at population-level interweaved with focus groups and semi-structured interviews to capture inter- and intra-personal factors affecting women’s engagement in HRPM through digital resources at individual-level. The focus groups allowed us to understand shared concerns, while interviews allowed us to capture patient journey and needs, and online peer interactions allowed us to explore generalizability of our design solutions and also examine solution seeking behaviors of women with HRPs, which can in turn help us in theory-mapping and content and feature engineering as well as engagement sustenance as we design digital pathways for HRPM.

Semi-automated methodology to enable large-scale social listening

Data extraction: For Study 1, we analyzed peer interactions extracted from two popular pregnancy apps used by women on a world-wide scale, What to Expect45 and Baby Center.46 Peer interactions were extracted from the PPD-specific forums “Postpartum Depression” (What to Expect) and “Postpartum Depression, Anxiety, and Related Topics” (Baby Center). We used a web scraping software called Scrapy47 for extracting the messages from the above-mentioned forums. We obtained a total of 12 416 threads containing 55 301 messages exchanged by 9364 individuals from years 2008 to 2022. The social forums and their respective messages used in this study were marked public and we also removed any potential identifiers (ie, usernames) from our data set. This study was approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center’s Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects IRB number HSC-SBMI-15-0697.

Qualitative analysis: From the above data set, a total of 1424 posts were randomly selected for qualitative analysis to assign thematic labels that were derived from grounded theory approaches48 (see Table S1 for definitions of themes and sample messages). These labels were guided by open codes that emerged from the data (eg, baby, panic, medication), from which we first developed a total of 14 themes, (eg, physical pain, anxiety and stress, baby routine, breastfeeding). These themes were then merged axially to form six themes (eg, physical and mental, mother and infant dyad) to facilitate pragmatic interventional insights in terms of content and feature optimization. In order to ensure consistency in the labeling process, the messages were labeled by two coders using a subset of 150 messages and computing interrater reliability among them (Cohen’s Kappa). Interrater reliability was consistently substantial across all themes, with the highest Cohen’s Kappa measure of 1.00 in the theme of “Family and friends,” followed by “Mother and Infant Dyad” (k = 0.98), “Doctor and Patient Dyad” (k = 0.92), “Physical and Mental Health” (k = 0.85), “Medications” (k = 0.84), and “Social Support” (k = 0.84). Any disagreements regarding labels were discussed among the researchers until a mutual agreement was reached.

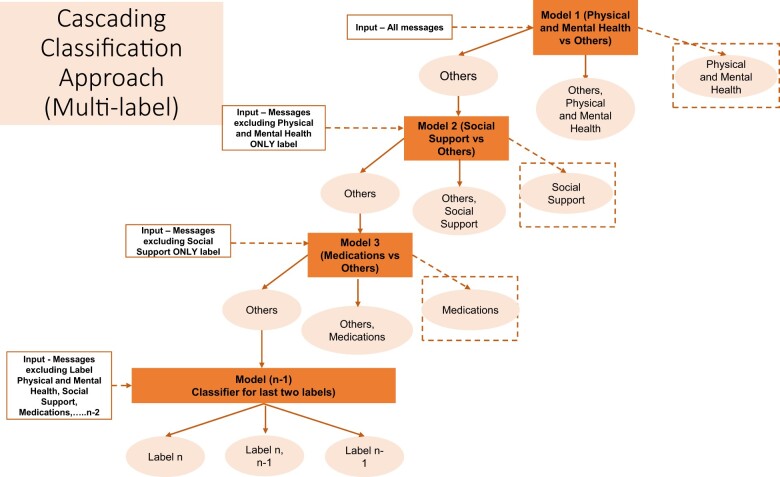

Automated text analysis: Transformer-based language models have emerged as the state-of-the-art models in many Natural Language Processing (NLP) tasks primarily because of their ability to capture bidirectional contextual information.49,50 Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) is a multilayer transformer encoder model implemented using the self-attention mechanism that learns information from both left and right side of token’s context.49,50 For this study, we further pretrained BERT (called BERT PPD-trained) in order to perform theme classification of messages from PPD online health communities. We pretrained the BERT-base model on PPD-specific corpus using our unlabeled data set of 55 301 messages. Given the imbalanced distribution of thematic labels in our data set, we built sequential models using the cascading classification approach based on the prevalence of labels in the manually annotated data set (Figure 3). We used a fine-tuning layer that consisted of two fully connected dense layers (768 and 512 units, respectively) and a sigmoid activation function in the output layer (2 units). We set the maximum sequence length to 100 and batch size to 32. We used AdamW optimizer to find individual learning rates for each parameter with the learning rate of 1 × 10−5. We then split the entire data set into 80%, 10%, and 10% for training, validation, and test sets, respectively. The model was trained for 20 epochs to fine-tune for our classification task. We used three evaluation metrics (recall, precision, and F1-score) to evaluate the classifier’s predictions per class on the held-out test data set.

Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows the cascading algorithm employed for multilabel classification of messages exchanged in an online forum on different topics ranging from physical health, social support to medications.

Development and optimization of digital experiences for HRPM

Following the Digilego framework, for Studies 2 and 3, we used a combination of focus groups and interviews to gather women’s needs for HRPM in addition to aforementioned social listening to understand population-level perspectives. Details of the methods and subsequent results can be found in our published works.51,52 In order for us to achieve theoretically informed digital health products for HRPM, we utilized BIT model.43 This allowed us to operationalize behavioral theory into tangible digital features. This model prompts intervention developers to answer the questions of Why?, How? (conceptual and technical), What?, and When? at the time of technology development. Further, to facilitate the identification of specific behaviorally based techniques to be integrated into digital modalities, we leveraged Michie’s Behavior Change Taxonomy.53 This is a standardized, comprehensive taxonomy of 93 theory-linked techniques for use in health behavior change interventions. Utilizing PEF, we defined the intended digital engagement level and optimized the user interaction features and technical complexity on the backend of the solutions allowing us to make informed choices and tradeoff decisions among theoretical nuances, technological sophistication and user experience producing a modular digital roadmap for our intended use cases in HRPM. To create digital features specific to GDM, HTN, and PPD, we leveraged and repurposed existing Digilego core architecture,41,42,54 specifically DigiSocial and DigiConnect blocks to provide coverage for peer support, journaling, and patient-generated data. Multiple specialized Digilego blocks were conceived and implemented (eg, DigiCAPSULE, DigiNavi). These special purpose features enable women to capture, aggregate, preserve, and summarize their HRP information and were dedicated for onboarding and streamlining digital experiences for women during the perinatal period. This mapping process allowed us to produce two digital products for HRPM, MomMind (for PPD) and MyPregnancyChart (for GDM/HTN). Initial prototypes for these applications were developed using AdobeXD and proof-of-concepts were built using ReactJS, Django, RedCap, and MySQL.

Initial evaluation of patient acceptance of MyPregnancyChart and MomMind

Our evaluation consisted of is combination of surveys and individual interviews with perinatal women (n = 10 for MyPregnancyChart) in Study 2 and (n = 30 for MomMind) in Study 3. Individuals had to be at least 18-years-old, English-speaking, and currently seeking pre/post-natal care at The Fetal Center clinic located within the UT Physicians healthcare system in the Texas Medical Center (Houston, Texas) to be eligible for participation. Eligible individuals were approached by their OB/GYN provider and explained the study. Informed consent was obtained for those who agreed to participate in the study. A $25 gift card for use in a national-level department store chain was offered as incentive for participating in the evaluation. The studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Center for Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Health Science Center at Houston, HSC-SBMI-22-0750 and HSC-SBMI-16-0594. Individuals were asked to complete a survey on their demographic background, their information technology preferences, and their prior experiences with HRPs. A semi-structured interview was conducted with questions based on the Integrated Behavior Model,55 a model that focuses on individual’s perceptions and intentions regarding a specific health behavior. Acceptability of the application was measured using Weiner’s set of Likert-scale surveys for intervention acceptance, feasibility, and appropriateness measures.56 In addition to these, for MomMind evaluation, we conducted an assessment of individuals’ PPD health literacy (knowledge, attitudes, beliefs) was conducted pre-and-immediately-post use of the app using the Postpartum Depression Literacy Scale.57 Also, we evaluated the education content presented through the “PPD 101” videos using a questionnaire based on previous evaluations of educational content presented in a similar digital format.58 The qualitative and quantitative methods used during our evaluation are summarized in Table S1.

Results

The findings from our Study 1 are as follows. The theme of “Physical and Mental Health” was the most discussed among users of PPD online social forums, with a total of 547 unique users. This was followed by the theme of “Social Support” (n = 437), “Medications” (n = 423), “Mother and Infant Dyad” (n = 359), “Doctor and Patient Dyad” (n = 335), and “Family and Friends” (n = 322). Detailed definitions and examples of peer interactions can be found in Table S2. To illustrate how these themes are applied in the context of the social forum, we follow a single conversation thread in this example. User 1 has begun the thread by expressing her frustration at the significant anxiety symptoms she experienced soon after starting a medication:

I started taking Zoloft a wk and half ago and my anxiety has been through the roof. I haven’t been able to drive since I started taking it out of fear of having a panic attack…I know you have to give it 2 wks but I can’t keep having extreme panic attacks every day. Help I don’t know what to do.

The user has sought peer support for help in deciding whether to stop the medication immediately, or continue for the recommended time of 2 weeks before stopping. The original post contains the themes of “Medications” and “Physical and Mental Health.” The replies to the original post contain a variety of themes, from “Social Support” in encouraging User 1 to continue the medication for 2 weeks, to “Doctor and Patient Dyad” in recommending the user seek care from doctors specializing in peripartum depression. An example reply illustrating social support:

Please give it time to work! I am on lexapro and I had a similar experience. I needed the 2 weeks before I started feeling a million times better. My only complaint now is the emotional numbness you’re referencing.

In analyzing this conversation thread, we can see how users’ interactions and the themes they discuss in the forum can help shape their decisions regarding PPD management. As shown in Table 1, the “Medications” theme had the highest F1 score of 0.96, followed by “Mother and Infant Dyad” theme which had a F1 score of 0.93, and “Family and Friends” theme had an F1 score of 0.90. The performance for “Doctor and Patient Dyad” was also substantial with an F1 score of 0.89, as was the performance for “Physical and Mental Health” with an F1 score of 0.88. The performance for “Social Support” was the lowest with an F1 score of 0.75.

Table 1.

Overall model performance of domain-trained BERT classification.

| BERT (PPD-trained) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall model performance | |||

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1 |

| Physical and Mental Health | 0.84 | 0.92 | 0.88 |

| Social Support | 0.73 | 0.78 | 0.75 |

| Medications | 0.94 | 0.99 | 0.96 |

| Mother and Infant Dyad | 0.89 | 0.99 | 0.93 |

| Family and Friends | 0.93 | 0.88 | 0.90 |

| Doctor and Patient Dyad | 0.87 | 0.91 | 0.89 |

The results of our development efforts for MyPregnancy Chart and MomMind can be found in Figure S1 and Table S3. Our initial evaluation of our MyPregnancyChart prototypes in Study 2 resulted in firm acceptance from our participants as indicated in Figure S2. Nine out of 10 participants indicated the solution is practical and approved the use of images-driven user interface for library interactions, and expressed the need for advanced annotation features rather than manual completion of curated information artifacts for GDM/HTN such as photos of blood glucose and blood pressure logs. All participants agreed the interface navigation is straightforward and intutive. Initial evaluation of MomMind in Study 3 revealed 96.6% of the participants approved of MomMind (29 out of 30), 96.6% of the participants deemed MomMind is easy to use (29 out of 30), 93.3% deemed MomMind is a good match (28 out of 30), and the PPD 101 content was deemed acceptable by 90% of the participants (27 out of 30). Our results also revealed statistically significant results in participants’ ability to recognize PPD pre- (3.89/5) and post- (4.25/5) MomMind use. Similar improvements are noted in their knowledge to seek PPD information (pre (3.49/5), post (3.79/5)).

Discussion

Our study provides an introduction to cross-cutting methods from behavioral theory, social sciences, data science, and digital health development, and describes their application to identify and address women’s needs for HRPM through a set of three studies. With the onset of mobility and connectivity in the communication sector, peer interactions in online health communities reflect the intricacies of engagement in HRPM as experienced in real-time at individual, community, and societal levels.59–62 Existing theories of behavior change and patient engagement models suggest a myriad of content-driven strategies to elicit specific socio-behavioral mechanisms beyond social support (eg, stimulus control, observational learning, role models) to drive maternal behavior modification and engagement.53,63 Through our Study 1, we demonstrate the utility of peer interactions in online communities to understand women’s needs from established participatory venues in the digital domain. These results along with our focus groups and user interviews with women dealing with HRPs51,52 have facilitated our development efforts resulting in two digital applications—MomMind and MyPregnancyChart focusing on various aspects of maternal health management. Insights extracted from social media analysis have helped us with content framing, design optimization, and feature implementation for self-monitoring of health behaviors in both MomMind and MyPregnancyChart.64–66 MomMind54,64 focuses on journaling and health education for women seeking perinatal care, and MyPregnancyChart focusses on user generated image repository of cataloguing perinatal health information as they manage GDM/HTN. Peer interactions illuminated specific knowledge gaps, such as misconceptions surrounding infant formula use, a significant source of anxiety for new mothers with PPD, which we directly addressed through tailored content creation within our MomMind application. In contrast, the unique needs of women with GDM/HTN prompted the integration of a health education module within our MyPregnancyChart app, specifically to debunk prevalent myths and resolve prevalent uncertainties regarding health supplements (eg, alternatives to insulin therapy). While discussions on PPD are more geared towards emotional needs and societal expectations, GDM/HTN discussions are focused on behavior modification, reasoning for physical symptom manifestations (eg, systolic spikes, adamant fasting glucose), and relevance of physician-prescribed behavioral goals. Our results from preliminary evaluation of MyPregnancyChart in Study 2 have revealed women’s acceptance of image-based health library, and emphasized the need for automated methods for machine-based annotation, integrative summaries, and personalized health education taking into account clinical, social, and demographic contexts of women, while accounting for health literacy and behavioral support to self-monitor maternal and neonatal health. Our evaluation results for MomMind in Study 3 suggest positive acceptance by women, including minority and low-income populations represented in our sample. During interviews, individuals identified many benefits of our applications, including creditable health information, ability to socialize with others, and recognized the synchronous design details with other general domain application they use in daily lives. Individuals also deemed the applications present simple design and ease of navigation, both seen as positive characteristics. However, participants noted room for improvement including interactive educational components with conversational capabilities, automated annotation capabilities for patient-generated data and images, and opportunities for practice-based peer support groups, which concurs with existing studies.67,68 Our paper has several limitations. In Study 1, the communication themes are limited to two online forums. And, the manual codes were inductively derived from only a subset of the data, additional themes might be present in the remainder of the data set. In Study 2, our evaluation is limited to preliminary prototypes with a low patient sample (n = 10) in formative phases and initial user acceptance of the proposed library solution for HRPM. Future studies testing the effectiveness of the solution for psychosocial measures (eg, self-efficacy, stress), knowledge level (eg, health literacy), pregnancy outcomes (eg, cesarean rates), and fetal outcomes (eg, birthweight) are highly desirable. In Study 3, participants had a limited time of interaction with MomMind, and a longitudinal study and log file analysis may provide a more thorough assessment of participant’s experiences. Further, a longitudinal study evaluating the efficacy and effectiveness of MomMind on PPD prevention and management is warranted.

Conclusions

Maternal health management forms a crucial component of our societal wellness going well beyond the peripartum period affecting women, their families, and future generations.69 Better efficiency and effectiveness of digital solutions that enable prevention and management of high-risk pregnancies are vital to enhance the quality of life during and after pregnancy as well as improve pregnancy and fetal health outcomes.70 Our Digilego framework provides a foundational step that will help influence the development of digital applications with reusable and customizable components as per the needs of the women across the care continuum. While our framework is aimed at women’s specific health conditions, our methods and core infrastructure can be used to develop interactive and innovative digital care pathways for management of any chronic disease (eg, diabetes, cardiovascular health) that requires patient engagement and self-health management. Use of informatics-driven methods, behavior change theories, and patient-centered design approaches may help us develop scalable and cost-effective digital assets and products that can be deployed globally.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Sahiti Myneni, Department of Clinical and Health Informatics at McWilliams School of Biomedical Informatics, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030, United States.

Alexandra Zingg, Department of Clinical and Health Informatics at McWilliams School of Biomedical Informatics, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030, United States.

Tavleen Singh, Department of Clinical and Health Informatics at McWilliams School of Biomedical Informatics, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030, United States.

Angela Ross, Department of Clinical and Health Informatics at McWilliams School of Biomedical Informatics, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030, United States.

Amy Franklin, Department of Clinical and Health Informatics at McWilliams School of Biomedical Informatics, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030, United States.

Deevakar Rogith, Department of Clinical and Health Informatics at McWilliams School of Biomedical Informatics, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030, United States.

Jerrie Refuerzo, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences at McGovern Medical School, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX 77030, United States.

Author contributions

Sahiti Myneni led manuscript writing, Digilego development, and architecture of the digital products; Alexandra Zingg contributed to expand Digilego into PPD; Tavleen Singh contributed the deep learning pipeline; Jerrie Refuerzo provided clinical expertise; Amy Franklin, Angela Ross, and Deevakar Rogith supported study design, data analysis, and manuscript editing.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at JAMIA Open online.

Funding

The work reported in this publication was supported by the National Library of Medicine of the National Institutes of Health under Award No. 1R01LM012974-01A1. The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Data availability

Some of the underlying data for this article are available upon request given participant privacy and data security needs.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990-2015: Estimates from WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. World Health Organization; 2015.

- 2. Reinke E, Haier JSupriyatiningsih. Maternal mortality as a millennium development goal of the United Nations: a systematic assessment and analysis of available data in threshold countries using Indonesia as example. J Glob Health. 2017;7(1):010406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cheng CY, Fowles ER, Walker LO.. Postpartum maternal health care in the United States: a critical review. J Perinat Educ. 2006;15(3):34-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Collier AR, Molina RL.. Maternal mortality in the United States: updates on trends, causes, and solutions. Neoreviews. 2019;20(10):e561-e574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Temkin SM, Noursi S, Regensteiner JG, Stratton P, Clayton JA.. Perspectives from advancing National Institutes of Health research to inform and improve the health of women: a conference summary. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(1):10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jovanovic L, Pettitt DJ.. Gestational diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286(20):2516-2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lawrence JM, Contreras R, Chen W, Sacks DA.. Trends in the prevalence of preexisting diabetes and gestational diabetes mellitus among a racially/ethnically diverse population of pregnant women, 1999–2005. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(5):899-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics. ACOG practice bulletin no. 190: gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(2):e49-e64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Landon MB. Changing the diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus? Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(1):3-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sava RI, March KL, Pepine CJ.. Hypertension in pregnancy: taking cues from pathophysiology for clinical practice. Clin Cardiol. 2018;41(2):220-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. ACOG practice bulletin no. 222. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135:e237-e260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Langan RC, Goodbred AJ.. Identification and management of peripartum depression. Am Fam Phys. 2016;93(10):852-858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Payne JL. Recent advances and controversies in Peripartum depression. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2016;5(3):250-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Howard MM, Mehta ND, Powrie R.. Peripartum depression: early recognition improves outcomes. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017;84(5):388-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Traube DE, Molina AP, YingWangKay S, Kemner A.. Perinatal mental health support and early childhood home visitation during COVID-19. Prev Sci. 2022;23(2):260–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Interrante JD, Admon LK, Stuebe AM, Kozhimannil KB.. After childbirth: better data can help align postpartum needs with a new standard of care. Womens Health Issues. 2022;32(3):208-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mo X, Tobe RG, Takahashi Y, et al. Economic evaluations of gestational diabetes mellitus screening: a systematic review. J Epidemiol. 2021;31(3):220-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hao J, Hassen D, Hao Q, et al. Maternal and infant health care costs related to preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(6):1227-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Valadares G, Drummond AV, Rangel CC, Santos E, Apter G.. Maternal mental health and peripartum depression. In: Rennó Jr J, Valadares G, Cantilino A, Mendes-Ribeiro J, Rocha R, Geraldo da Silva A, eds. Women's Mental Health: A Clinical and Evidence-Based Guide. Springer; 2020:349-375. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Daneshmand SS, Stortz S, Morrisey R, Faksh A.. Bridging gaps and understanding disparities in gestational diabetes mellitus to improve perinatal outcomes. Diabetes Spectr. 2019;32(4):317-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jain J, Moroz L.. Strategies to reduce disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality: patient and provider education. Semin Perinatol.2017;41(5):323-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Onaade O, Maples JM, Rand B, Fortner KB, Zite NB, Ehrlich SF.. Physical activity for blood glucose control in gestational diabetes mellitus: rationale and recommendations for translational behavioral interventions. Clin Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;7(1):7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ferrara A. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus: a public health perspective. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Suppl 2):S141-S146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mirfeizi M, Mehdizadeh Tourzani Z, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Moghimi Hanjani S, Hasanzad M.. Health education in gestational diabetes mellitus and quality of life. J Midwifery Reprod Health. 2017;5(4):1066-1074. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Overdijkink SB, Velu AV, Rosman AN, Van Beukering MD, Kok M, Steegers-Theunissen RP.. The usability and effectiveness of mobile health technology–based lifestyle and medical intervention apps supporting health care during pregnancy: systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(4):e8834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wallwiener S, Müller M, Doster A, et al. Pregnancy eHealth and mHealth: user proportions and characteristics of pregnant women using web-based information sources—a cross-sectional study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;294(5):937-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ancker JS, Witteman HO, Hafeez B, Provencher T, Van de Graaf M, Wei E.. The invisible work of personal health information management among people with multiple chronic conditions: qualitative interview study among patients and providers. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(6):e137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. O'Connor S, Hanlon P, O'Donnell CA, Garcia S, Glanville J, Mair FS.. Understanding factors affecting patient and public engagement and recruitment to digital health interventions: a systematic review of qualitative studies. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):120-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alper J, Martinez RM, McHugh K. Workshop on Improving Outcomes for Mother and Child: Addressing Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine; 2021.

- 30. Kostkova P. Grand challenges in digital health. Front Public Health. 2015;3:134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Peyton T, Poole E, Reddy M, Kraschnewski J, Chuang C. "Every pregnancy is different" designing mHealth for the pregnancy ecology. In: Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Designing Interactive Systems. 2014:577-586.

- 32. Mehregany M, Saldivar E.. Opportunities and obstacles in the adoption of mHealth. In: Krohn R, Metcalf D, eds. mHealth From Smartphones to Smart Systems. HIMSS Publishing; 2020:7-20. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Powell J, Deetjen U.. Characterizing the digital health citizen: mixed-methods study deriving a new typology. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(3):e11279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Alkhaldi G, Modrow K, Hamilton F, Pal K, Ross J, Murray E.. Promoting engagement with a digital health intervention (HeLP-Diabetes) using email and text message prompts: mixed-methods study. Interact J Med Res. 2017;6(2):e6952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jongsma KR, van den Heuvel JF, Rake J, Bredenoord AL, Bekker MN.. User experiences with and recommendations for mobile health technology for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: mixed methods study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(8):e17271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brusniak K, Arndt HM, Feisst M, et al. Challenges in acceptance and compliance in digital health assessments during pregnancy: prospective cohort study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(10):e17377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jeffries N, Zaslavsky AM, Diez Roux AV, et al. Methodological approaches to understanding causes of health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S1):S28-S33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Meskó B, Drobni Z, Bényei É, Gergely B, Győrffy Z.. Digital health is a cultural transformation of traditional healthcare. Mhealth. 2017;3:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen IY, Joshi S, Ghassemi M.. Treating health disparities with artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2020;26(1):16-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smith B, Magnani JW.. New technologies, new disparities: the intersection of electronic health and digital health literacy. Int J Cardiol. 2019;292:280-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Myneni S, Rogith D, Franklin A. Digilego: a standardized analytics-driven consumer-oriented connected health framework. In: International Conference on Social Computing, Behavioral-Cultural Modeling and Prediction and Behavior Representation in Modeling and Simulation. Springer; 2018:263-273.

- 42. Myneni S, Amith M, Geng Y, Tao C.. Towards an ontology-driven framework to enable development of personalized mHealth solutions for cancer survivors’ engagement in healthy living. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:113-117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mohr DC, Schueller SM, Montague E, Burns MN, Rashidi P.. The behavioral intervention technology model: an integrated conceptual and technological framework for eHealth and mHealth interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(6):e3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Alhubaysh A, Almutairi N, Win K. Patient Engagement through Mobile Health Interventions of Diabetes: A Systematic Literature Review. In: ACIS Proceedings. 2022.

- 45. Expect Wt. What to Expect. Accessed February 1, 2024. https://www.whattoexpect.com

- 46. BabyCenter. BabyCenter. Accessed February 15, 2024. https://www.babycenter.com

- 47.Scrapy. A fast and powerful scraping and web crawling framework. Accessed February 28, 2024. https://Scrapy.org

- 48. Strauss A, Corbin JM.. Grounded Theory in Practice. Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K. Bert: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1810.04805, October 11, 2018.

- 50. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, et al. Attention is all you need. Adv Neural Inform Processing Syst. 2017;30:5998-6008. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zingg A, Carter L, Rogith D,. et al. Digital technology needs in maternal mental health: A qualitative inquiry. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2021;281:979-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zingg A, Singh T, Myneni S.. Analysis of online peripartum depression communities: application of multilabel text classification techniques to inform digitally-mediated prevention and management. Front Digit Health. 2021;3:653769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zingg A, Rogith D, Refuerzo JS, Myneni S.. Digilego for peripartum depression: a novel patient-facing digital health instantiation. In: AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings 2020. Vol. 2020. American Medical Informatics Association; 2020:1421. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K.. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implementation Sci. 2017;12(1):1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mirsalimi F, Ghofranipour F, Noroozi A, Montazeri A.. The postpartum depression literacy scale (PoDLiS): development and psychometric properties. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Valera P, Acuna N, Alzate-Duque L, Liang LE, Cupertino P, Merulla J.. The development and prototype feedback of digital cancer 101 videos to enhance cancer education for marginalized communities with limited health literacy. Cancer Control. 2021;28:10732748211006055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Bagalkot N, Verdezoto N, Ghode A, et al. Beyond health literacy: navigating boundaries and relationships during high-risk pregnancies: challenges and opportunities for digital health in North-West India. In: Proceedings of the 11th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Shaping Experiences, Shaping Society. 2020:1-15.

- 60. Rhodes A, Smith AD, Chadwick P, Croker H, Llewellyn CH.. Exclusively digital health interventions targeting diet, physical activity, and weight gain in pregnant women: systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(7):e18255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Figueroa CA, Luo T, Aguilera A, Lyles CR.. The need for feminist intersectionality in digital health. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3(8):e526-e533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Guendelman S, Broderick A, Mlo H, Gemmill A, Lindeman D.. Listening to communities: mixed-method study of the engagement of disadvantaged mothers and pregnant women with digital health technologies. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(7):e7736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Moller AC, Merchant G, Conroy DE, et al. Applying and advancing behavior change theories and techniques in the context of a digital health revolution: proposals for more effectively realizing untapped potential. J Behav Med. 2017;40(1):85-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zingg A, Singh T, Myneni S. Towards digestible digital health solutions: application of a health literacy inclusive development framework for peripartum depression management. In: AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. Vol. 2021. American Medical Informatics Association; 2021:1274. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zingg A, Singh T, Franklin A, et al. Digital health technologies for peripartum depression management among low-socioeconomic populations: perspectives from patients, providers, and social media channels. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23(1):411-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Singh T, Roberts K, Cohen T, Cobb N, Franklin A, Myneni S.. Discerning conversational context in online health communities for personalized digital behavior change solutions using pragmatics to reveal intent in social media (PRISM) framework. J Biomed Inform. 2023;140:104324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tresp V, Overhage JM, Bundschus M, Rabizadeh S, Fasching PA, Yu S.. Going digital: a survey on digitalization and large-scale data analytics in healthcare. Proc IEEE. 2016;104(11):2180-2206. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lupton D. Digital Health: Critical and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives. Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Annandale E. Women's Health and Social Change. Routledge; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lupton D. Towards critical digital health studies: reflections on two decades of research in health and the way forward. Health (London). 2016;20(1):49-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Some of the underlying data for this article are available upon request given participant privacy and data security needs.