Summary

While CD4+ T-cell depletion is key to disease progression in people living with HIV and SIV-infected macaques, the mechanisms underlying this depletion remain incompletely understood, with most cell death involving uninfected cells. In contrast, SIV infection of “natural” hosts such as sooty mangabeys do not cause CD4+ depletion and AIDS despite high-level viremia. Here, we report that the CARD8 inflammasome is activated immediately after HIV entry by the viral protease encapsulated in incoming virions. Sensing of HIV protease activity by CARD8 leads to rapid pyroptosis of quiescent cells without productive infection, while T-cell activation abolishes CARD8 function and increases permissiveness to infection. In humanized mice reconstituted with CARD8-deficient cells, CD4+ depletion is delayed despite high viremia. Finally, we discovered loss-of-function mutations in CARD8 from “natural hosts”, which may explain the peculiarly non-pathogenic nature of these infections. Our study suggests that CARD8 drives CD4+ T-cell depletion during pathogenic HIV/SIV infections.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

The hallmark of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) pathogenesis is a progressive depletion of CD4+ T-cell populations, which represents the main pathogenic mechanism responsible for the increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections and progression to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The mechanism through which HIV depletes CD4+ T cells in humans has been the subject of intense research for decades. While HIV infection induces a well-defined cytopathic effect, CD4+ T-cell depletion is not confined to virus-infected cells, because only around 1 in 104 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or up to 1% CD4+ T cells were infected in untreated individuals1–5. Notably, only cells positive for HIV RNA, DNA, or protein were defined as infected cells in these studies, thus identifying cells in which the life cycle of productive HIV infection has reached at least the state of retro-transcription and, most likely, virus integration in the host genome. In fact, viral RNA was rarely observed in the dying CD4+ T cells during HIV infection6. However, these cells likely experienced a co-receptor-mediated interaction with the virus, possibly resulting in virus entry but without engaging in productive infection, as suggested by the observation that CD4+ T-cell depletion requires HIV co-receptor expression7,8. Pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infections in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta, RM) are also associated with high viremia, rapid depletion of non-productively infected CCR5-expressing CD4+ T cells, and progression to simian AIDS6,9,10. In SIV-infected RMs, rapid inflammasome activation was observed both at the site of SIV inoculation and the sites of distal virus spread11. In this model, caspase-1(CASP1)-dependent pyroptosis has been described as the dominant mechanism responsible for the rapid CD4 depletion by SIV, whereas other programmed cell death mechanisms contribute minimally12. In humans, CASP1 activation and pyroptotic cell death were observed in bystander CD4+ T cells from viremic individuals13.

Naturally occurring SIV infections have been identified in over 40 different African NHP species. Interestingly, natural SIV infections of the African Cercopithicenae species sooty mangabeys (Cercocebus atys) and African green monkeys (Chlorocebus sabaeus) do not lead to systemic CD4+ T-cell loss and progression to AIDS, even though the virus is equally cytopathic in productively infected CD4+ T cells and plasma viral loads are comparable to untreated HIV infections and SIV-infected RMs14. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) acquired SIV by transmission and recombination of SIVs infecting primate species on which they prey15, and SIVcpz infection of chimpanzees resulted in increased mortality and development of AIDS-related symptoms16–18. Of note, studies using chimeric SIVs suggested that pathogenicity is determined by specific aspects of the host-pathogen interaction, as opposed to intrinsic differences in the viral genomes, thus indicating that the immune response to the virus during pathogenic infections likely contributes to the observed CD4+ T-cell depletion19. In natural SIV hosts, the resistance to disease progression has been attributed to several non-mutually exclusive factors, including the absence of chronic immune activation14,20,21, low levels of microbial translocation from the gut22,23 and subsequent systemic immune activation24, and the limited level of infection of specific CD4+ T cells subsets including central memory cells, stem-cell memory cells, and follicular helper cells25–27. Since one of the hallmarks of non-pathogenic SIV infection is the lack of bystander CD4+ T-cell death21, it is important to understand whether CD4+ T cells from the natural hosts are inherently resistant to SIV-induced bystander cell death.

Taken together, the vast majority of available observations are compatible with the hypothesis that direct, virus-mediated cytopathic effect in productively infected cells is not the major driver of CD4+ T-cell depletion during pathogenic HV/SIV infection of humans and RMs. However, the mechanisms by which HIV and SIV trigger cell death in bystander CD4+ T cells remain poorly understood, including the role of inflammasome activation. In this regard, it should be noted that most aspects of inflammasome function and biology have been identified and characterized in myeloid cells, and that their roles in human CD4+ T cells are not well defined. We recently reported that caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 8 (CARD8) can detect HIV protease activity and mediates assembly of the inflammasome complex28, but its physiological role in HIV infection and pathogenesis is unclear. The CARD8 C-terminus contains a “function-to-find” domain (FIIND), followed by a CARD domain. CARD8 undergoes autoproteolytic processing in the FIIND domain, generating the N-terminal ZU5 and C-terminal UPA-CARD fragments that remain associated noncovalently between the F296 and S297 positions29. CARD8 can be activated by direct proteolysis of its N terminus by viral proteases28,30, which results in an unstable neo–N terminus targeted for proteasome degradation. Because of the noncovalent bond, the bioactive UPA-CARD subunit is liberated and initiates CASP1-dependent inflammasome assembly. The ability of the CARD8 inflammasome to drive pyroptotic cell death has been demonstrated in different lineages of immune cells28,31–33. In cells already productively infected by HIV, the virus produces the Gag-Pol polyprotein after integration, which contains an embedded form of protease with minimal enzymatic activities. Interestingly, some clinically approved non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) drive dimerization of Gag-Pol, which leads to premature activation of the viral protease. NNRTI-mediated Gag-Pol dimerization provides a strategy of targeting HIV-1 protease to eliminate viral reservoirs. In this study, we aimed to determine whether CARD8 is responsible for HIV- and SIV-induced CD4 depletion, and if so, how CARD8 is activated during the natural course of viral infection to drive rapid CD4+ T-cell loss. Additionally, we aimed to investigate the genetic differences in the NHP CARD8, which may help explain the differences seen in SIV pathogenesis across NHP species.

Results

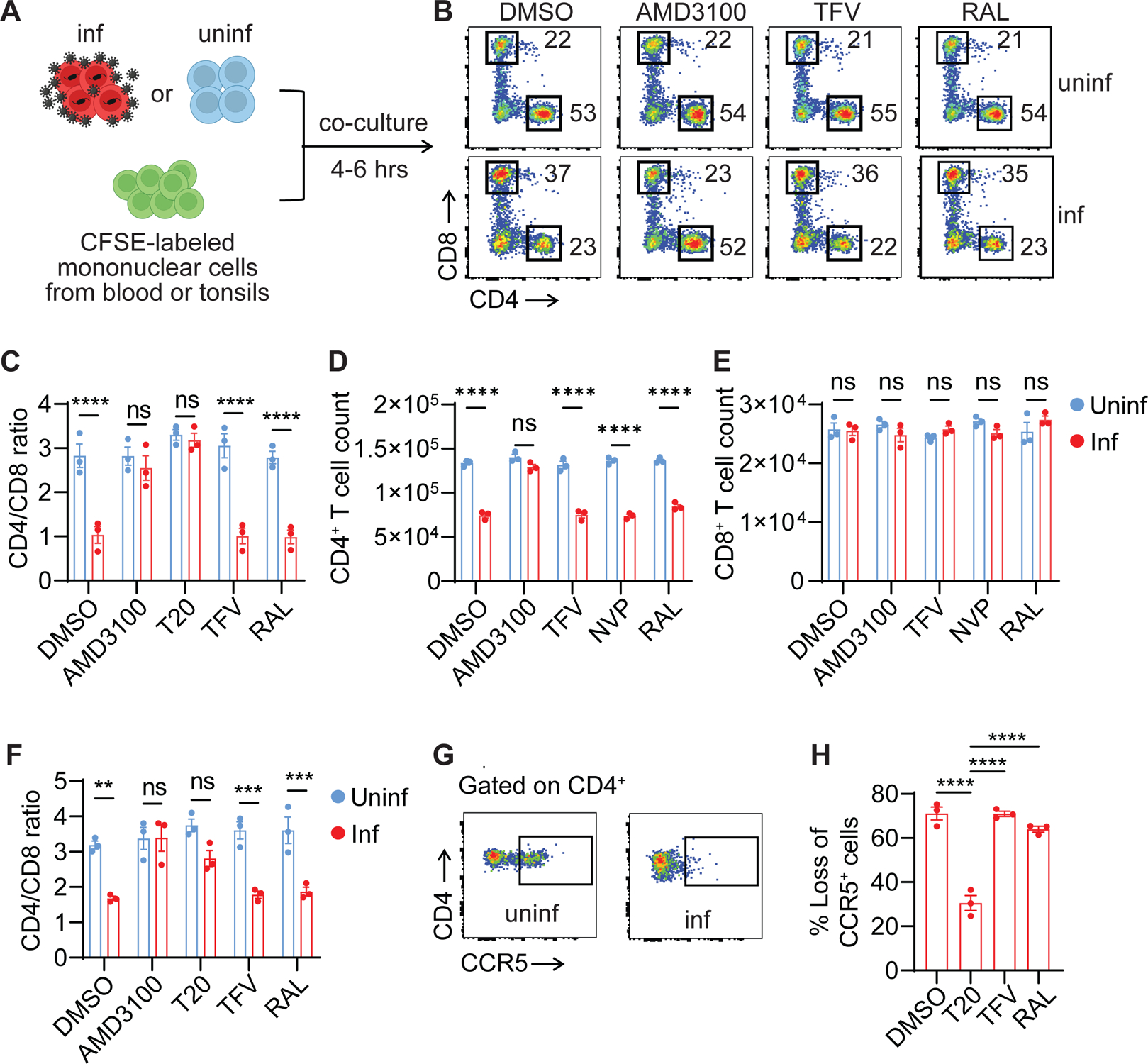

HIV entry induces rapid CD4+ T-cell loss through the CARD8 inflammasome

To determine how HIV induces rapid loss of CD4+ T cells and whether CARD8 is involved, activated CD4+ T cells pre-infected with HIV were co-cultured with autologous peripheral blood or tonsil mononuclear cells (PBMCs or ToMCs) in the presence of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs). The percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was measured by flow cytometry within six hours after co-culture, allowing us to examine cell death immediately after viral entry (Figure 1A). The CD4 to CD8 ratio was reduced from 2.4 to 0.6 when co-cultured with CD4+ T cells pre-infected with HIVNL4-3 (Figure 1B). Inhibitors AMD3100 and T20 that block viral entry completely abolished blood and tonsillar CD4+ T-cell loss measured by the CD4 to CD8 ratio and cell counts, whereas blocking viral reverse transcription by tenofovir (TFV), nevirapine (NVP), or integration by raltegravir (RAL) did not prevent CD4+ T-cell depletion (Figure 1C–F). The extent of cell loss was determined by the ratio between infected and uninfected cells (Figure S1A and B). These results suggested that cell death occurred post-viral entry but before reverse transcription. When CD4+ T cells pre-infected with the CCR5-tropic HIVBaL were used for the co-culture experiments, a rapid depletion of CCR5+ CD4+ T cells was observed (Figure 1G and H), demonstrating that this effect was entry-dependent and was not limited to X4-tropic viruses. Additionally, the PMA-stimulated ACH-2 cell line was used as the virus-producing cell and similar CD4+ T-cell depletion was observed in blood and tonsillar samples (Figure S1C–F).

Figure 1. HIV entry triggers rapid loss of CD4+ T cells.

(A) The co-culture schemes. Activated blood or tonsillar CD4+ T cells were infected with either HIVNL4-3 or HIVBaL for three days. Virus-producing cells were then co-cultured at a 1:1 ratio with CFSE-labeled donor-matched unstimulated mononuclear cells from blood or tonsils for four to six hours with the presence of indicated ARVs.

(B) Representative plots were shown from blood cells infected with HIVNL4-3.

(C-F) Rapid loss of blood and tonsillar CD4+ T cells. Virus-producing cells were infected with HIVNL4-3. Three blood samples (C-E) and three tonsillar samples (F) were used.

(G and H) Rapid loss of CCR5+ CD4+ T cells. Virus-producing cells were infected with HIVBaL. Three blood samples were used.

In C-F, p values were calculated using the two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison tests. In H, p values were calculated using the one-way ANOVA with Dunnett tests. ** p < 0.01. *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001. Error bars show mean values with standard errors of the mean (SEM). n=3.

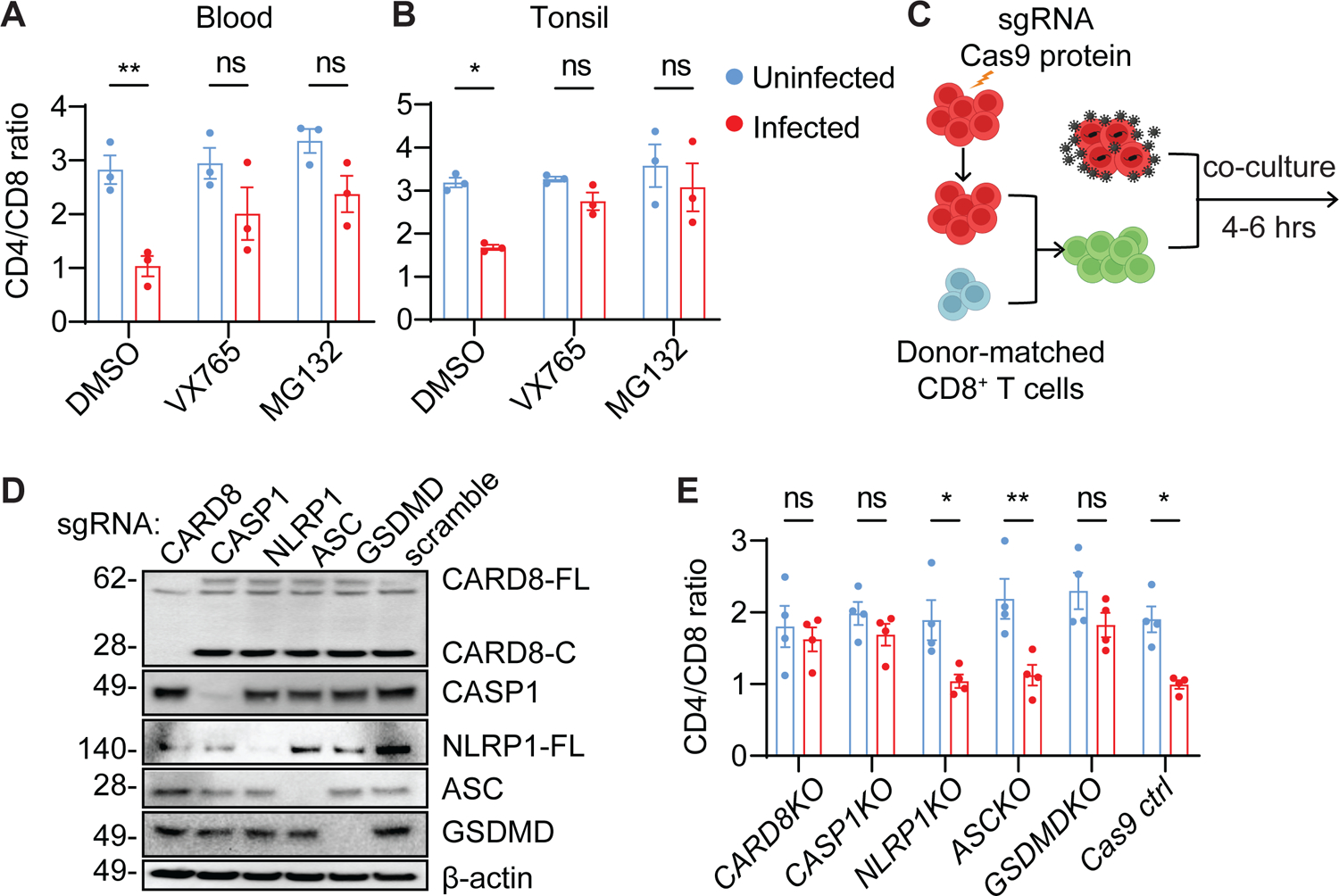

To determine whether the rapid CD4+ T-cell destruction post-viral entry was due to CARD8-mediated pyroptosis, we first confirmed that it was prevented by the CASP1-specific inhibitor VX765 and the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Figure 2A and B). Next, we modified the co-culture system to test Cas9-edited CD4+ T cells (Figure 2C). We found that CARD8-, CASP1-, and GSDMD-KO CD4+ T cells were resistant to HIV entry-mediated cell killing, whereas NLRP1 and other ASC-dependent inflammasomes were not involved in this process (Figure 2D and E). Compared to the six-hour co-culture, a longer co-culture did not affect the resistance in CARD8- and CASP1-KO cells, but GSDMD-KO cells lost their resistance (Figure S2A). These results suggest that an alternative pathway was activated, which was also CARD8- and CASP1-dependent. CARD8-mediated GSDMD-independent cell death is observed in other studies. Cell death in GSDMD-KO THP-1 cells was due to CASP1-depedent activation of caspase-3 and -7 to trigger apoptosis34. Therefore, during HIV-1 infection, CD4+ T cells mainly undergo GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis since GSDMD is functional in all CD4+ T cells. However, strategies that block GSDMD are unable to prevent loss of CD4+ T cells. Furthermore, cell death was not reduced in NLRP3-, IFI16-, or ASC-KO CD4+ T cells from blood or tonsils suggesting that these inflammasome components were not involved (Figure S2B–E).

Figure 2. CD4+ T-cell depletion by HIV is mediated by the CARD8 inflammasome.

(A and B) Rapid CD4+ T-cell death is proteasome- and CASP1-dependent. Unstimulated PBMCs (A) or ToMCs (B) were pretreated with VX765 (50 μM) or MG132 (10 μM) for 30 minutes and then co-cultured with donor-matched uninfected or HIVNL4-3-producing CD4+ T cells for six hours before flow cytometry analyses.

(C) The co-culture scheme of Cas9-edited unstimulated CD4+ T cells and HIV-infected autologous CD4+ T cells. Unstimulated CD4+ T cells electroporated with the indicated gene-specific sgRNA were cultured for three weeks and then mixed with donor-matched CD8+ T cells before co-culture with HIV-infected CD4+ T cells from the same donor.

(D and E) The CARD8 inflammasome is required for the rapid loss of CD4+ T cells. Unstimulated CD4+ T cells with indicated knockouts were mixed with autologous CD8+ T cells at a 2:1 ratio before co-culture with HIVNL4-3-producing cells. Cas9 editing efficiency was confirmed in D. The immunoblots represent four independent experiments. Four blood samples were used.

p values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison tests. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ns: not significant. Error bars show mean values with SEM from three or four independent blood donors.

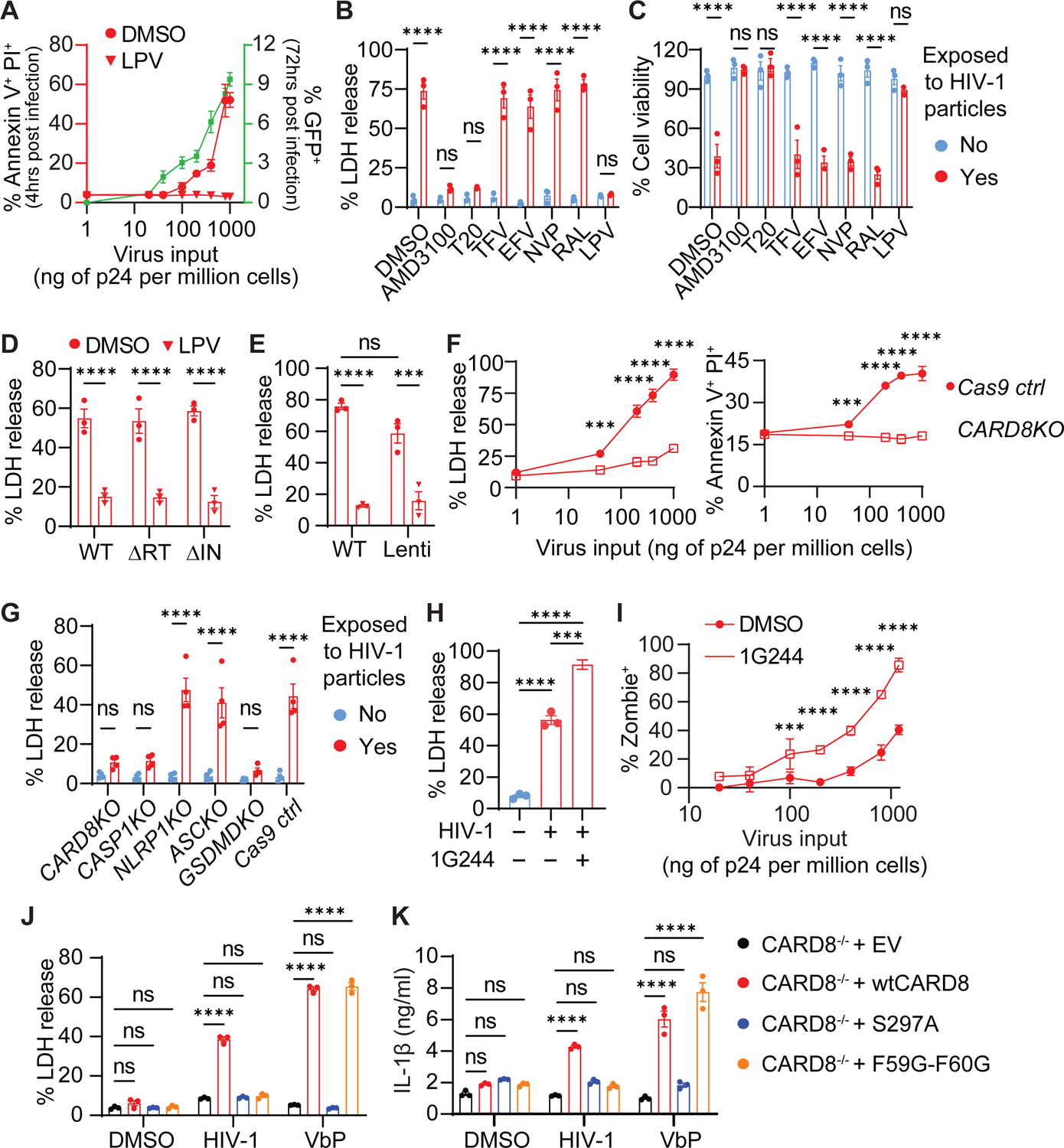

The CARD8 inflammasome is activated by HIV protease encapsulated in incoming viral particles

Previous studies showed that cell-free viral particles triggered rapid cell death of CD4+ T cells35. Since the multiplicity of infection by spin-inoculation is likely higher than natural infection, we aimed to determine whether abrogation of CARD8 function could protect CD4+ T cells from pyroptosis despite exposure to a copious amount of HIV particles. We utilized the cell-free replication-defective HIV reporter virus NL4-3-ΔEnv-EGFP pseudotyped with the NL4-3 envelope for primary CD4+ T cells or VSV-G for THP-1 cells to study cell death post viral entry. Cell death after exposure to HIV particles was determined by quantitation of ATP and LDH release and staining of annexin V, propidium iodide (PI), Zombie live/dead, and active caspase-1, while productive infection was determined by GFP expression. Productive infection (GFP+) in the DMSO group was measured 72 hours post exposure. Similar to the co-culture experiments, cell death was observed four hours post-exposure to cell-free HIV particles, which was completely blocked by a viral protease inhibitor lopinavir (LPV) regardless of viral doses (Figure 3A). Cell death was also blocked by viral entry inhibitors T20 and AMD3100, whereas ARVs that did not block viral entry had no effect on cell death, except for LPV (Figure 3B and C, and S3A–C). Next, we introduced reverse transcriptase inactive (ΔRT, RT-D110A-D185A) or integrase inactive (ΔIN, IN-D116A) mutations to the NL4-3-ΔEnv-EGFP plasmid, which then generated HIV reporter virus particles carrying either deactivated RT or integrase in their respective viral particles. We found that both mutant viruses induced cell death as efficiently as the control reporter virus (Figure 3D and S3D), despite being unable to form productive infections (Figure S3E and F). More importantly, lentiviral particles carrying HIV Gag-Pol triggered comparable levels of cell death as the HIV reporter virus (Figure 3E), These results suggest that the rapid cell killing was due to release of the viral protease during or immediately after viral entry and that the viral protease was sufficient to drive CD4+ T-cell death. Next, short-term exposure to HIV particles led to caspase-1 activation and LDH release, which were abrogated by VX765 and MG132 (Figure S3G and H). Viral entry also resulted in GSDMD cleavage in CD4+ T cells, which was blocked by LPV (Figure S3I). Furthermore, deletion of CARD8, CASP1, and GSDMD in CD4+ T cells completely abrogated early cell death induced by HIV entry, confirming that HIV infection induces rapid pyroptosis in CD4+ T cells through the CARD8 inflammasome (Figure 3F and G, and S3J). Similar to the co-culture experiments, prolonged exposure to HIV particles with the presence of RAL to block productive infection did not affect the resistance of CARD8 KO and CASP1 KO cells to post-viral entry killing (Figure S4K). Dipeptidyl peptidase 9 (DPP9) negatively regulates CARD8 activity by binding to and sequestering the bioactive CARD8 C-fragment36. Thus, abolishing CARD8 and DPP9 interaction sensitizes the CARD8 inflammasome in cells exposed to HIV particles37. While the DPP9 inhibitor 1G244 alone at ≤1μM did not drive cell death, it greatly enhanced HIV entry triggered pyroptosis of CD4+ T cells (Figure 3H and I, and S3L), further demonstrating that CARD8 is the driver of the post-viral entry cell death.

Figure 3. HIV infection induces CARD8 inflammasome activation by virion-packaged protease.

(A-E) Rapid loss of CD4+ T cells induced by HIV protease encapsulated in the incoming viral particles. In (A), unstimulated CD4+ T cells were exposed to cell-free HIV reporter virus NL4-3-ΔEnv-EGFP pseudotyped with the NL4-3 envelope. Cell death and productive infection (GFP+) were measured four hours and three days post-infection, respectively. In (B and C), unstimulated CD4+ T cells were treated with indicated antiretroviral drugs for 30 minutes before being exposed to HIV reporter viral particles. In (D and E), unstimulated CD4+ T cells were pre-treated with LPV or DMSO for 30 minutes and then exposed to indicated enzyme inactive reporter HIV or lentiviral particles pseudotyped with the NL4-3 envelope. ΔRT: D110A and D185A. ΔIN: D116A.

(F and G) Rapid loss of CD4+ T cells is mediated by the CARD8 inflammasome. Cell death was determined at indicated virus doses or in different knockout cells.

(H and I) 1G244 enhances HIV entry-triggered pyroptosis of CD4+ T cells. Unstimulated CD4+ T cells were exposed to cell-free virions with or without 1G244 for four hours.

(J and K) Activation of CARD8 inflammasome by HIV-1 in THP-1 cells. CARD8-KO THP-1 cells expressing wild-type or mutant CARD8 were exposed to HIV reporter virus NL4-3-ΔEnv-EGFP pseudotyped with the VSVG envelope for six hours before LDH or IL-1β measurement. VbP (5 μM) was used as positive controls.

In (H), p values were calculated using the one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests. Other p values were calculated using the two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison tests. * p < 0.05, **** p < 0.0001. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01. The data points are means with SEM and represent three or more independent experiments.

Our previous study demonstrated that HIV protease cleaves CARD8 between F59 and F60, leading to the formation of an unstable neo-N-terminus for proteasome degradation and subsequent activation of the CARD8 inflammasome28. In this study, we sought to find direct evidence of CARD8 cleavage and activation by HIV particle-derived viral protease. We generated CARD8-KO THP-1 cells replete with wild-type (wt), cleavage-deficient (F59G-F60G), or autoprocessing-deficient (S297A) CARD8. Autoprocessing is required for HIV protease-induced CARD8 inflammasome activation, because only the autoprocessed CARD8 can release its bioactive C-terminus from the proteasome complex due to the non-covalent bond. Of note, VSVG pseudotyped reporter viruses were used to infect THP-1 cells more efficiently, and viral entry mediated by VSVG and HIV envelopes utilize different mechanisms. HIV triggered LDH release and IL-1β secretion with the presence of the wtCARD8, whereas both wtCARD8 and the F59G-F60G mutant restored VbP-triggered cell death and IL-1β secretion in CARD8−/− THP-1 cells (Figure 3J and K). Upon viral entry, the CARD8 C-fragment generated by the viral protease cleavage was not detectable, likely because of its rapid degradation by the proteasome, but it became detectable when MG132 was added to the culture (Figure S3M). These results demonstrate that the HIV protease encapsulated in the incoming viral particles is required and sufficient to trigger CARD8-mediated pyroptosis immediately after viral entry.

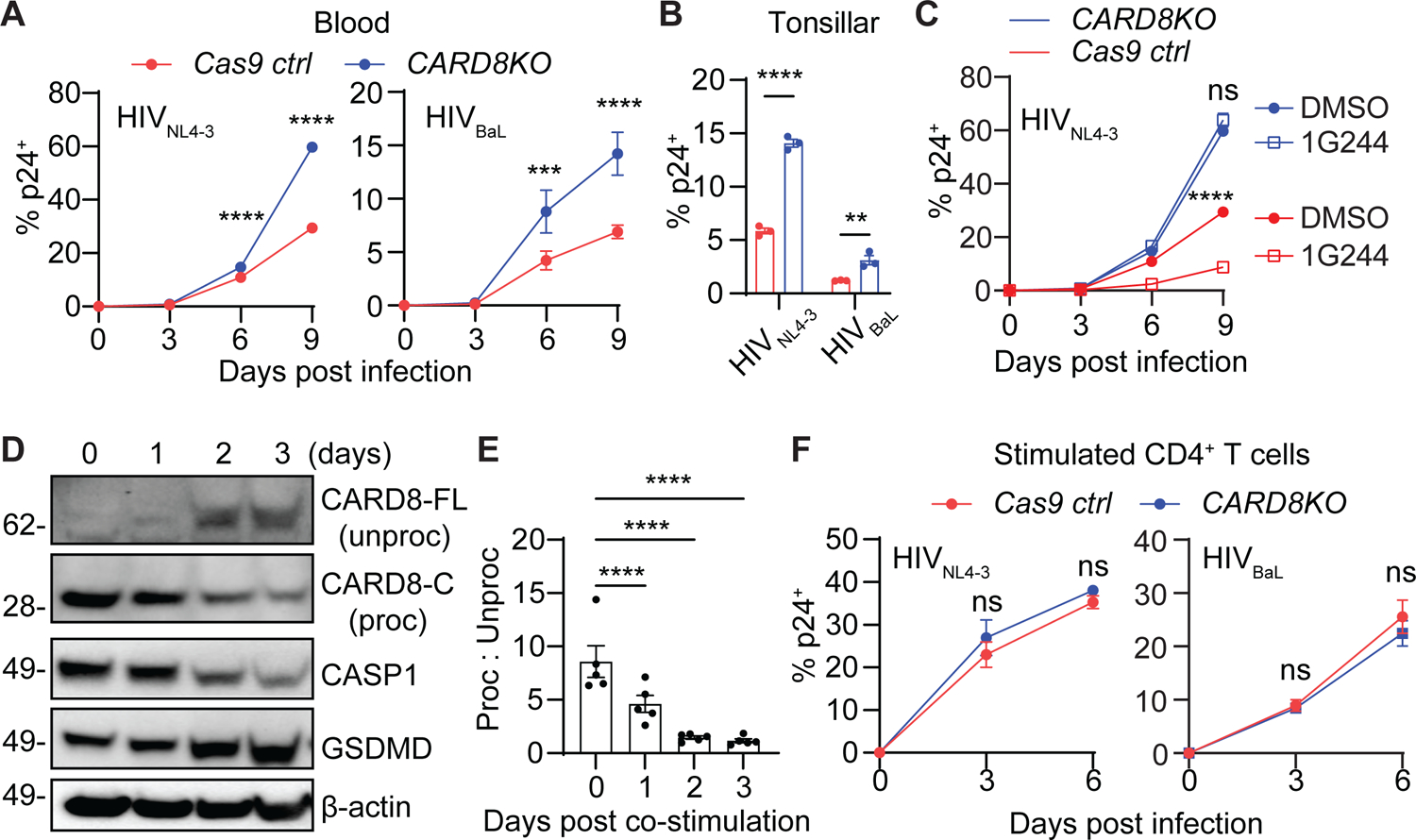

The CARD8 inflammasome restricts HIV infection in unstimulated CD4+ T cells

Since CARD8 can be activated immediately after HIV entry, it may function as a host restriction factor to suppress HIV replication. To test this hypothesis, CARD8-KO or control CD4+ T cells from blood and tonsils were infected with CXCR4- or CCR5-tropic HIV isolates to measure infection by intracellular p24 staining. Both HIVNL4-3 and HIVBaL replicated more efficiently in CARD8- and CASP1-KO CD4+ T cells (Figure 4A and B, and S4A). In addition, sensitization of CARD8 by the DPP9 inhibitor 1G244 suppressed viral replication in Cas9 control cells infected with either replication-competent HIVNL4-3 or a single-round HIV reporter virus, whereas knockout of CARD8 abolished this effect (Figure 4C and S4B). Activated CD4+ T cells have diminished CARD8 function, and hence, are resistant to DPP9 inhibitor-induced pyroptosis31,33. To assess CARD8 activation by HIV protease in activated CD4+ T cells, we first measured the expression levels of CARD8 in CD4+ T cells following TCR stimulation. Although CARD8 was expressed by both unstimulated and activated CD4+ T cells, the CARD8 autoprocessing was highly efficient in unstimulated cells as evidenced by the dominant presence of autoprocessed C-terminal fragments (Proc) and the lack of unprocessed full-length CARD8 (Un-proc) by immunoblotting. By contrast, TCR stimulation led to a loss of the autoprocessed CARD8 and accumulation of unprocessed full-length CARD8 (Figures 4D and E, and S4C), the latter of which may have dominant-negative effects. We performed the co-culture experiments described in Figure 1 and found that the rapid CD4+ T-cell destruction was abolished after T cell activation (Figure S4D). Furthermore, deletion of the CARD8 coding gene had no significant impact on HIV replication in stimulated CD4+ T cells (Figure 4F). Taken together, these findings prove that the CARD8 inflammasome regulates the fate of resting CD4+ T cells upon HIV entry and restricts productive viral infection.

Figure 4. The CARD8 inflammasome restricts HIV infection in unstimulated CD4+ T cells.

(A-C) Loss of CARD8 leads to increased susceptibility to HIV infection in unstimulated CD4+ T cells. CARD8-KO or Cas9 ctrl unstimulated CD4+ T cells from blood (A) or tonsil (B) were infected with HIVNL4-3 or HIVBaL at 40 ng HIVp24 per million cells. Infection was measured by intracellular p24 staining. Tonsillar samples were analyzed on day six post-infection. In (C), CARD8-KO or Cas9 ctrl unstimulated CD4+ T cells were infected with HIVNL4-3 or HIVBaL with or without 1G244 (500 nM).

(D and E) Accumulation of unprocessed CARD8 in activated CD4+ T cells. Immunoblotting was performed to analyze CARD8 expression and autoprocessing following anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 stimulation of CD4+ T cells.

(F) The CARD8 inflammasome does not restrict HIV infection in activated CD4+ T cells. CARD8-KO or Cas9 ctrl activated CD4+ T cells were infected with HIVNL4-3 or HIVBaL at 40 ng HIVp24 per million cells. Infection was measured by intracellular p24 staining.

In (E), p values were calculated using the one-way ANOVA with Dunnett tests. Other p values were calculated using the two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison tests. * p < 0.05, **** p < 0.0001. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01. Error bars show mean values with SEM. n=3.

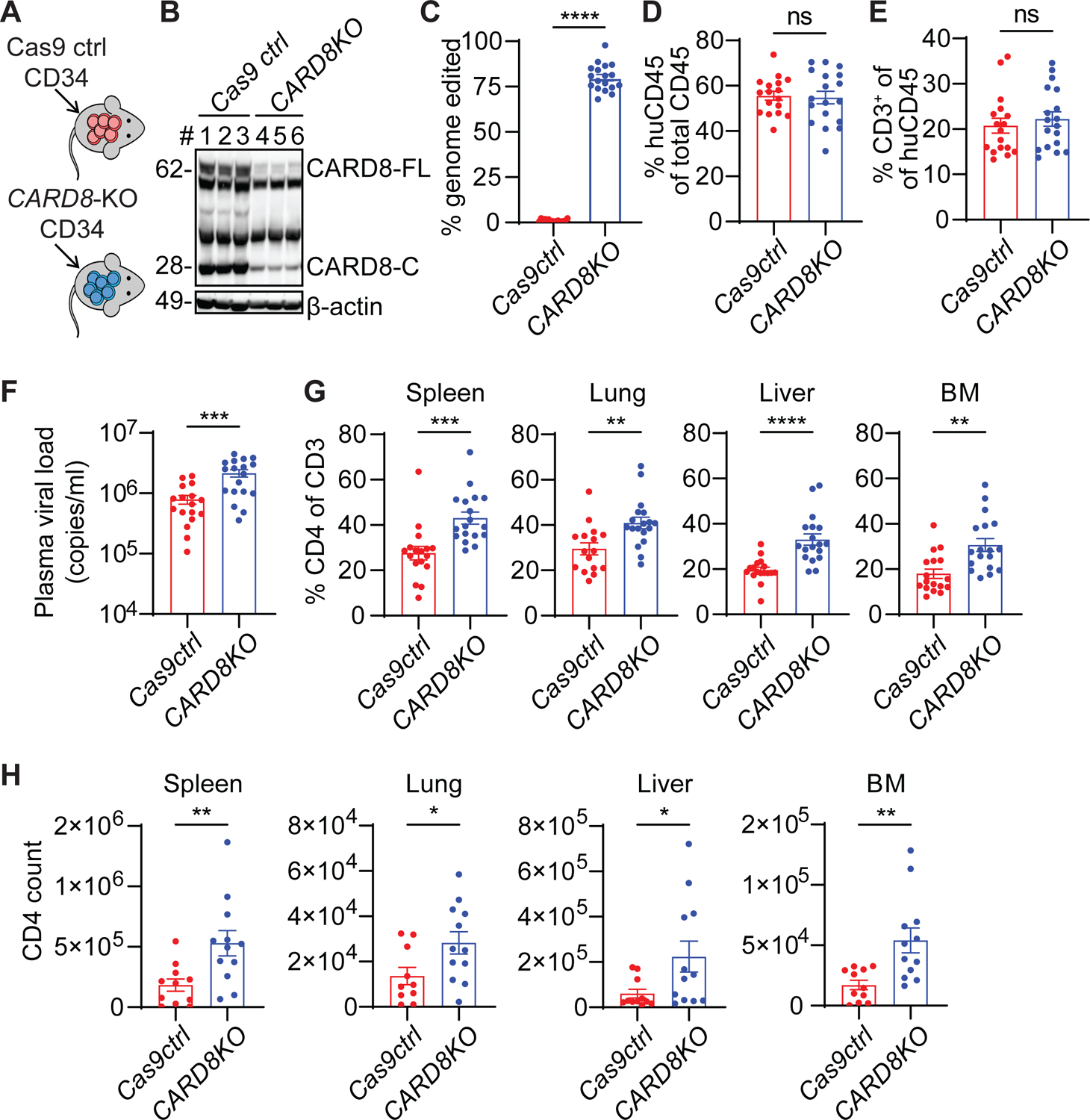

The CARD8 inflammasome promotes CD4+ T-cell depletion in humanized mice infected with HIV

Human immune system mice (humanized mice) are susceptible to HIV infection and lose CD4+ T cells over time. To evaluate the role of the CARD8 inflammasome in CD4+ T-cell depletion in vivo, we used electroporation to deliver the Cas9 protein and CARD8-targeting sgRNAs into human CD34+ cells to obtain humanized mice with a CARD8-deficient immune system. Due to limited numbers of CD34+ cells from each cord blood sample and reduced cell viability after electroporation to introduce Cas9 and sgRNAs, we used the NSG-SGM3 strain in this study because this mouse strain expresses human IL-3, GM-CSF, and stem cell factor, which allow robust engraftment by as few as 30,000 CD34+ cells38. We first characterized HIV infection and disease progression in this mouse model. HIVBaL infection led to a progressive loss of CD4+ T cells in blood (Figure S5A), concomitant with lymphocytes activation evidenced by increased plasma IFNγ levels (Figure S5B). In tissues, CD4+ T-cell depletion was evident as early as two weeks post infection (Figure S5C and D), and a near-complete loss of CD4+ T cells was observed in all tissues four weeks after infection (Figure S5E). Next, we generated human CARD8-KO or Cas9 control CD34+ cells to engraft immunodeficient mice (Figure 5A). We confirmed the reconstitution of the CARD8-KO human immune system in mice by immunoblotting (Figure 5B) and by deep sequencing analysis, which showed that 75–90% of human immune cells in mice were CARD8-edited (Figure 5C and S6A). The frequency and number of human CD4+ T cells in tissues and their CCR5 expression were not affected by deletion of the CARD8 coding gene (Figure S6B–E). We then generated three independent mouse cohorts and confirmed that overall human hematopoietic cell reconstitution (Figure 5D), T cell development (Figure 5E), and CD4 levels (Figure S6F) in blood were comparable between the two groups before infection. Next, we infected these mice with HIVBaL and measured plasma viral loads and CD4+ T cells in different tissues. Mice reconstituted with CARD8-KO immune system had higher levels of plasma HIV RNA (Figure 5F), suggesting that CARD8 restricted HIV replication, which was consistent with our in vitro experiments. Despite increased levels of viral replication, CARD8-KO resulted in a delay of CD4+ T-cell loss in blood (Figure S6G). Importantly, CARD8 ablation more efficiently protected tissue CD4+ T cells, as evidenced by increases in the frequency and number of CD4+ T cells in all tissues in CARD8-KO mice (Figures 5G and H). CCR5-tropic HIV infection results in a systemic depletion of memory CD4+ T cells, because CCR5 expression is restricted in memory populations39. In our humanized mice, the frequency of naïve CD4+ T cells was higher in control mice (Figure S6H), suggesting a more profound depletion of memory cells in the presence of the CARD8 inflammasome. Our study in humanized mice demonstrates that the CARD8 inflammasome promotes CD4 depletion during HIV infection.

Figure 5. The CARD8 inflammasome leads to the loss of CD4+ T cells in humanized mice with HIV infection.

(A) Strategy for generating CARD8-edited humanized mice.

(B) Representative immunoblotting of total splenocytes from the uninfected CARD8-KO and Cas9 ctrl groups. Cas9 ctrl, n=3; CARD8-KO, n=3.

(C) Blood samples were collected to determine the frequency of CARD8 editing by MiSeq. Cas9 ctrl, n=17; CARD8-KO, n=18.

(D and E), Human immune cell reconstitution and T cell development in mice engrafted with CARD8-KO or Cas9 ctrl CD34+ cells. Blood samples were collected 10 weeks after transplantation. Cas9 ctrl, n=17; CARD8-KO, n=18.

(F) Plasma viral loads was measured two weeks after infection. Cas9 ctrl, n=17; CARD8-KO, n=18.

(G and H) The frequency and number of human CD4+ T cells in tissues. In G, Cas9 ctrl, n=17, except for lung (n=16); CARD8-KO, n=18. In H, Cas9 ctrl, n=11, except for lung (n=10); CARD8-KO, n=12.

Data were pooled from three independent mouse cohorts. p values were calculated using an unpaired two-tailed t-test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001. Error bars show mean values with SEM.

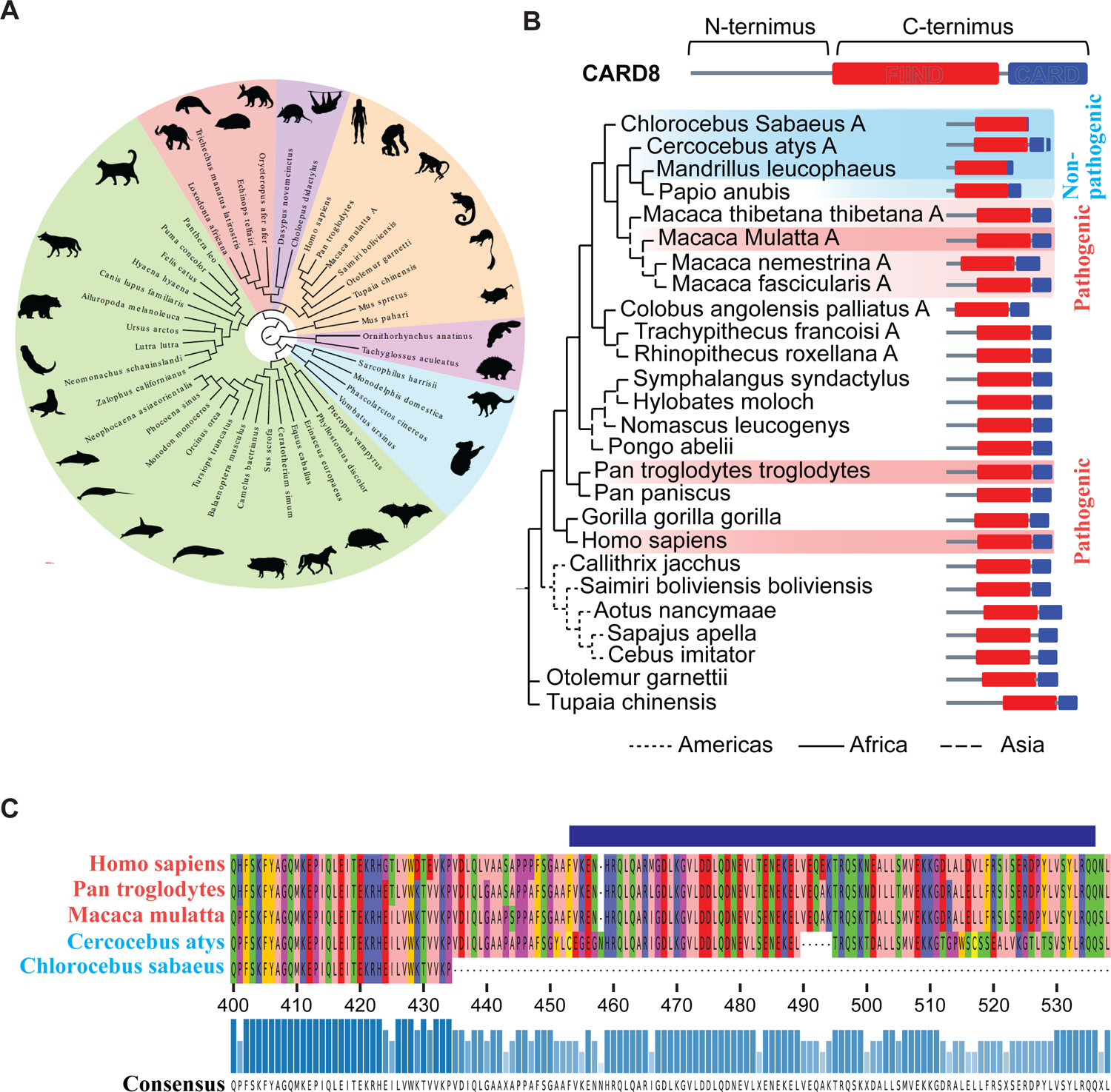

The NHP CARD8 coding gene in non-pathogenic hosts of SIV contains loss-of-function mutations

To first understand the conservation of the CARD8 gene, CARD8 protein sequences from a majority of the mammalian orders were aligned and used to construct a maximum likelihood gene tree (Figure 6A). CARD8 can be found in most extant mammalian species that have been sequenced, with distinct variation seen in the mammalian superorder Laurasiatheria. The Carnivora order clustered more closely with the superorders of Xenartha, Afrotheria, and Euarchontoglires instead of with the other more closely related members of Laurasiatheria indicating a potentially distinct diversification of the CARD8 gene in this order which more closely resembles that of the members of the Xenartha, Afrotheria, and Euarchontoglires. Alternatively, this could denote a rapid diversification of the CARD8 gene in Laurasiatheria as a whole. We also note that the Euarchontoglires does not represent a monophyletic group due to diversification of the CARD8 gene in rodents. As CARD8 is present in most mammalian species, with large genetic variations seen, we next sought to understand how genetic variation has impacted CARD8’s evolution in NHPs. We identified CARD8 sequences from 25 different NHPs, and surprisingly we found that all Cercopithecoidae have evidence of a reverse tandem gene duplication of CARD8 (Table S5). Of note, one of these copies – hereby termed CARD8B – has a truncated N-terminal region due to genomic loss of these exons, which is the critical region for viral protease recognition. In contrast, the other copy– hereby termed CARD8A – maintained an intact N-terminus. As this version of the gene is the most likely functional copy for lentiviral recognition, we next aligned CARD8A of Cercopithecoidae with the only copy of CARD8 for the other NHPs. Interestingly, the CARD8A of the non-pathogenic SIV hosts Chlorocebus sabaeus and Cercocebus atys have truncations in the CARD domain (Figure 6B), which may impact its interaction with CASP1. The Chlorocebus CARD8A completely lost the CARD domain exons and the Cercocebus gene contained several small deletions resulting in frameshifts giving rise to large variations in the domain and a five amino acid deletion. However, the CARD domain of rhesus macaques and chimpanzees remain intact and share homology with the human sequence (Figure 6C). Next, a species tree of the expected evolutionary relationships of non-human primates and their close relatives of the Scandentia order was created using the NCBI taxonomy browser and adjusted to account for updated relationships identified from recently published findings from whole genome phylogenomics of more than 200 primate species40–42 (Figure S7A). This phylogenetic tree shows large differences in comparison to the one based on evolutionary relationships of NHP CARD8A, indicating substantial evolution of CARD8 in comparison to the whole genome. We believe this may be assisted by the presence of the gene duplication events in the Cercopithecoidae species, as gene duplication allows for greater mutational rates. This is in stark contrast to other inflammasome sensors reported to play a role in CD4+ T-cell bystander cell death such as with interferon gamma inducible protein 16 (IFI16). The gene tree developed for IFI16 more closely resembles that of the expected evolutionary relationships of NHP species (Figure S7B). IFI16 proteins between pathogenic and non-pathogenic hosts share 98% and 97% homology (Table S6). We therefore theorize that the genetic differences in CARD8 may be better suited to explain the differential response to SIV infection in non-pathogenic and pathogenic hosts of SIV infection.

Figure 6. Genetic analysis of the NHP CARD8 inflammasome reveals functional defects in non-pathogenic hosts of SIV infection.

(A) Phylogenetic analysis of mammalian CARD8. The protein sequences of the longest isoform for each CARD8 gene from each species were aligned and used to construct the maximum likelihood tree shown. CARD8 is present in every superorder (pink: Monotremata, blue: Marsupiala, purple: Xenartha, red: Afrotheria, green: Laurasiatheria, and orange: Euarchontoglires). Laurasiatheria is polyphyletic, Euarchontoglires is paraphyletic, and all other superorders are monophyletic. The sequences used to generate this tree may be found in Table S4.

(B) Maximum likelihood gene tree of CARD8 or CARD8A from the selected NHP species. Dark red shading indicates known pathogenic HIV/SIV hosts and light red the suspected pathogenic hosts; dark blue depicts known non-pathogenic hosts, and light blue the suspected non-pathogenic hosts. The protein schemes on the right depict the predicted domain architecture based on the alignment to the known domain structure of the human protein. (C) Protein alignment of the CARD domains and part of the FIIND domains of the species of known pathogenicity status.

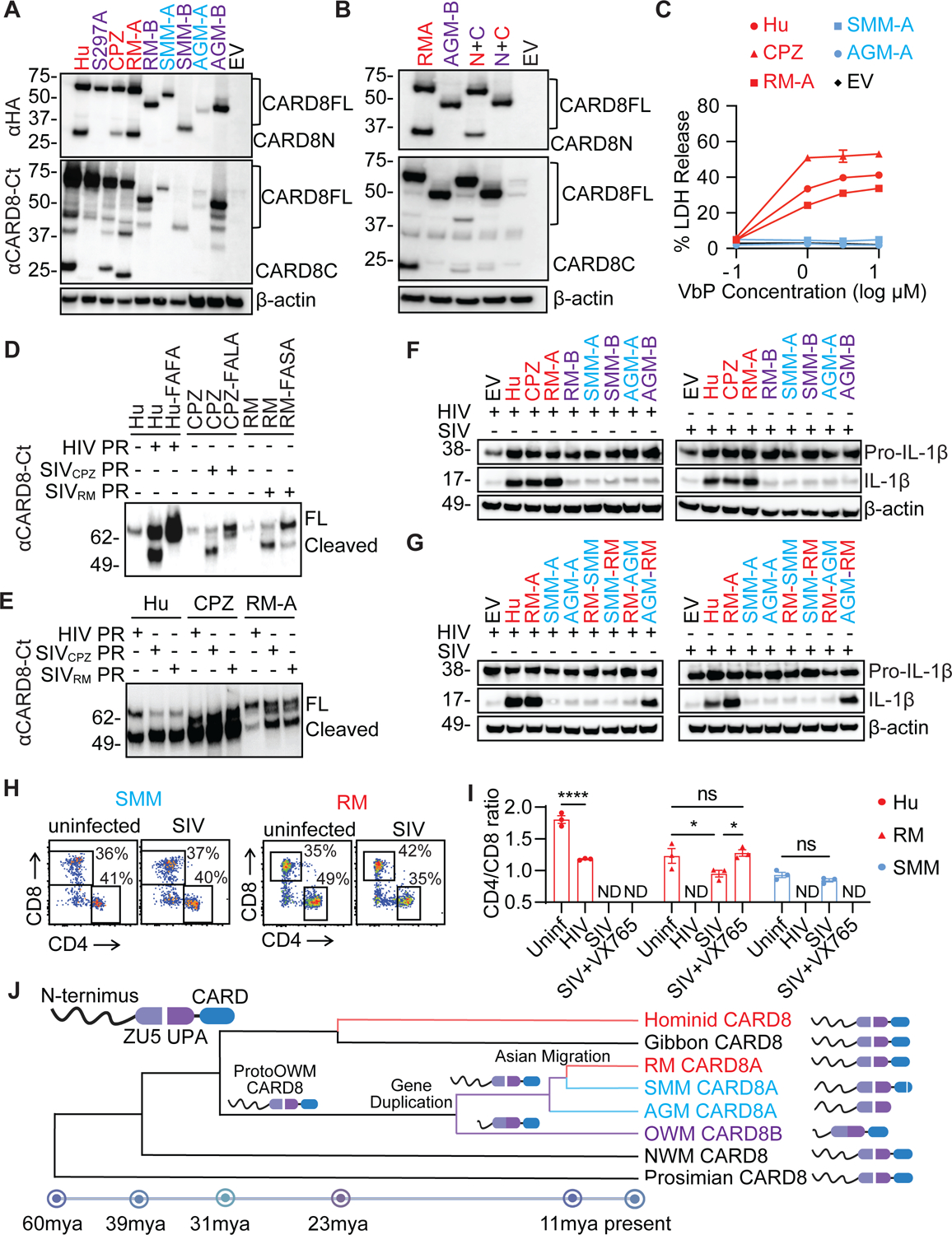

The CARD8 inflammasome is defective in non-pathogenic hosts of SIV

To further assess whether the CARD8 inflammasome can explain differences in pathogenicity of NHPs, we cloned the NHP CARD8 coding genes including card8 from chimpanzee (CPZ), and card8a and card8b from rhesus macaque (RM), sooty mangabey (SMM), and African green monkey (AGM). Human CARD8 and the autoprocessing-deficient S297A mutant were included as controls. Expression of these human and NHP CARD8 proteins in human or NHP cell lines demonstrates that CARD8B from all three Cercopithecinae species (in purple) do not autoprocess (Figure 7A and S7C), likely due to the common CARD8B N-terminal truncation in Cercopithecinae species. Based on genomic analyses, CARD8A from sooty mangabeys and African green monkeys have deletions in the CARD domain, thus they are smaller than the CARD8 from the pathogenic hosts (Figure 7A and S7C). To further understand whether the N-terminal truncation affected the autoprocessing in the FIIND-CARD domain, we swapped the N- and C-terminus of RM-CARD8A and AGM-CARD8B. The intact CARD8A N-terminus was able to restore autoprocessing in the CARD8B FIIND-CARD domain (Figure 7B). By contrast, the CARD8B N-terminal region was able to abolish autoproteolytic activity of the FIIND-CARD of CARD8A. We next generated CARD8-KO THP-1 cells that stably express different NHP CARD8 to test the capacity of these proteins to respond to VbP, a known activator of the human CARD8 inflammasome. We found that CARD8 proteins from the pathogenic hosts were able to respond to VbP treatment (Figure 7C). As VbP is a non-specific activator of the CARD8 inflammasome independent upon PR recognition, we next tested whether NHP CARD8 senses SIV PR by an in vitro cleavage assay using purified PR and CARD8 proteins. HIV and SIV were able to cleave CARD8 from their respective hosts, which is blocked by the putative cleavage site mutations (Figure 7D). Interestingly, PR from SIVRM and SIVCPZ had strong cross species activities, whereas HIV PR cleaved RM CARD8 less efficiently (Figure 7E), likely because HIV-1 protease prefers the F-F motif43. To test whether this cleavage could result in functional inflammasome activation, we transfected CARD8-KO HEK293T cells with human pro-CASP1, pro-IL-1β, and the NHP CARD8 along with HIV or SIV reporter plasmids. Co-transfection with HIV and SIV led to cleavage of pro-IL-1β to its active form (Figure 7F), which was blocked after the introduction of cleavage mutations (Figure S7D). To further confirm that the CARD domain loss-of-function mutations in natural hosts were responsible for the ablation of CARD8A activity, we swapped the CARDs of SMM and AGM with the functional CARD of RM, or vice versa. The addition of the CARD domain of RM to the AGM CARD8 protein restored its ability to sense SIV and HIV protease as evidenced by IL-1β cleavage, indicating the truncation in the CARD domain is responsible for loss of CARD8A function in AGMs (Figure 7G and S7E). By contrast, RM N-terminus with a truncated CARD domain from natural hosts lost its inflammasome activity. Surprisingly, the addition of the RM CARD to SMM CARD8A did not restore IL-1β cleavage. We then found that the major cleavage site in SMM CARD8 is at a position different from other primates, generating a smaller freed C-terminus (Fig. S7F), which might disrupt the subsequent inflammasome activation. To quantify cell death in primary NHP cells, we conducted co-culture experiments using RM and SMM PBMCs alongside human PBMC controls. CEM-174 cells were used as the viral producing cells for SIVmac 251 and were co-cultured with unstimulated NHP PBMCs (Figure S7G). Only the PBMCs from RMs had rapid CD4+ T cell depletion as evidenced by the reduction in the CD4:CD8 ratio in PBMCs from five different animals, which was blocked by VX765 (Figures 7H and I, and S7H). In contrast, CD4+ T-cell loss was not observed in SMM PBMCs. Finally, we wanted to confirm the predicted CARD8A sequences in SMM and RM PBMCs. Stimulated PBMCs from RMs were used to clone out the predicted CARD8A cDNA and sent for sequencing for confirmation, whereas SMM sequences were confirmed by publicly available RNAseq data from LPS-stimulated monocytes from SMMs (Table S7)24. These sequences map closely with the reference sequences used for this study and show slight interspecies variation in SMMs. Taken together, these data suggest that CARD8 in natural hosts of SIV is functionally defective and cannot trigger pyroptosis upon SIV entry. In summary, proto-OWMs underwent a CARD8 gene duplication which resulted in a functional CARD8A and a dysfunctional CARD8B carrying a truncated N-terminus (Figure 7J). OWM species remaining in Africa further acquired loss-of-function truncations or mutations in the CARD domain, rendering these species resistant to SIV PR-mediated CD4+ T-cell pyroptosis.

Figure 7. The CARD8 inflammasome is functional in pathogenic hosts and defective in non-pathogenic hosts of SIV infection.

(A) Autoprocessing of NHP CARD8. HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-tagged CARD8 from Hu and CPZ, and CARD8A and CARD8B from RM, SMM, and AGM.

(B) CARD8 N-terminal truncation inhibits its C-terminal autoprocessing. The two chimeric CARD8 (N+C) were RMA N-terminus (red) plus AGMB C-terminus (cyan) and AGMB N-terminus (cyan) plus RMA C-terminus (red).

(C) Validation of NHP CARD8 functions. CARD8-KO THP-1 cells replete with indicated NHP CARD8 were treated with VbP for six hours before cell death measurement by the LDH release assay.

(D and E) In vitro cleavage of human and NHP CARD8 by HIV and SIV protease. Purified CARD8 proteins and SIV or HIV protease were incubated for one hour before immunoblotting. CARD8 cleavage site mutants included Hu-FAFA, CPZ-FALA, and RM-FASA.

(F and G) Activation of human and NHP CARD8 inflammasome by HIV and SIV. CARD8-KO HEK293T cells were co-transfected with HIV or SIV molecular clones together with plasmids encoding CASP1, pro–IL-1β, and human or NHP CARD8. In (G), indicated chimeric CARD8 (N+C) proteins were used.

(H and I) Rapid loss of CD4+ T cells. Co-culture of human, RM, and SMM PBMCs with SIVmac251-infected CEM-174 cells. CD4/CD8 ratio was measured 16 hours post co-culture. Two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. * p < 0.05 and **** p < 0.0001. Error bars show mean values with SEM for PBMC from three separate primates.

(J) The evolution of non-human primate CARD8 depicting key events in its evolution. CARD8 underwent a reverse tandem gene duplication in the ancestor to old world monkeys (OWM) giving rise to a non-functional CARD8B and a functional CARD8A. The CARD8A of non-pathogenic hosts in Africa underwent further selection leading to non-functionalization of the protein whereas the Asian migration of macaques allowed for escape from this selective pressure. Speciation dates are estimated based on recently published findings42. NWM – new world monkeys.

Discussion

Pathogenic HIV infection of humans and SIVmac infection of rhesus macaques (RMSs) are characterized by progressive CD4+ T-cell depletion even though productive viral infection is largely confined to activated CD4+ T cells, the majority of which are already destined to die rapidly regardless of infection44. In contrast, non-pathogenic SIV infection of natural SIV hosts, such as sooty mangabyes (SMMs) and African green monkeys (AGMs) is associated with normal or near normal CD4+ T-cell counts despite chronic high levels of virus replication. These observations prompted a series of investigations aimed at clarifying the mechanisms responsible for the death of non-productively infected CD4+ T cells during pathogenic HIV and SIV infections (or, conversely, the mechanisms allowing the survival of these cells during non-pathogenic SIV infection of SMMs and AGMs). Of note, during pathogenic SIV infection of RMs, the rapid depletion of CD4+ T cells by CCR5- or CXCR4-tropic chimeric simian–human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) involves predominantly CCR5+ memory cells or CXCR4+ cells, respectively, strongly suggesting that the mechanism for CD4+ T-cell depletion involves viral entry or at least co-receptor engagement by the Env glycoprotein9. In addition, the observation that the vast majority of CD4+ T cells die of pyroptosis during pathogenic SIV infection in RMs11,12 raised the question of what molecular mechanism(s) triggers inflammasome activation in CD4+ T cells after the HIV/SIV envelope protein engages the co-receptor, and if that phenomenon requires virus entry.

In the current study, we provide substantial experimental evidence indicating that the CD4+ T-cell depletion associated with pathogenic primate lentiviral infections is caused by an aberrant activation of the CARD8 inflammasome pathway. In addition, we posit that those primate species that have evolved to be natural hosts for non-pathogenic SIV infections (i.e., SMMs and AGMs) have developed truncations in the CARD domain of the CARD8 locus that could have been expedited by the presence of CARD8B. It is possible that SIV or other pathogens with the same geographic distribution caused these loss-of-function mutations in CARD8 of African NHPs. While the molecular dynamics of both copies of CARD8 (i.e., “A” and “B”) are not fully understood, we believe that CARD8B may retain additional yet unknown functions of CARD8 that allowed, in evolutionary terms, for the ablation of its inflammasome activity in response to persistent SIV infection. While we do not understand the consequences of this gene duplication, it is still possible that this event could have led to subfunctionalization or neofunctionalization of the different copies of CARD8 allowing for each copy to take on some roles of the ancestral CARD8 or new functions completely. While in this study we offer a snapshot of the predicted splicing patterns of these CARD8 genes in various NHP species, future work will focus on a comparative in vivo functional analysis of the CARD8 inflammasome system in these species. Future work will also investigate whether the two copies of CARD8 gene could be working in concert via subfunctionalization to retain a low level of inflammasome activity.

Using both cell-to-cell and cell-free models, we demonstrated that the viral protease encapsulated in the incoming viral particles activated the CARD8 inflammasome immediately after viral entry into CD4+ T cells. We then showed that genetic ablation of CARD8 blocked the rapid CD4+ T-cell depletion following viral entry. The current study also highlights how resting CD4+ T cells are selectively targeted by HIV for rapid CARD8 activation. Furthermore, we reconstituted CARD8-KO or Cas9 control human immune systems in immunodeficient mice and demonstrated that CARD8 accelerates the virus-associated loss of CD4+ T cells. We acknowledge that CARD8 ablation only partially prevented CD4+ T-cell loss, which could be related to factors such as incomplete genome editing of CD34+ cells and immune features specific to humanized mouse models. Since humanized mice are generally lymphopenic due to suboptimal thymic development and human T cell selection, the model is associated with continuous expansion of memory T cells, which results in a higher frequency of proliferating CCR5+CD4+ T cells (Figure S6D). As such, the fraction of CD4+ T-cell depletion due to productive viral infection that does not require inflammasome activation is greater in humanized mice than humans. In addition, T cell renewal after depletion in humanized mice is less efficient, resulting in the absence of the partial CD4 recovery observed during pathogenic lentiviral infections of primates. However, the lack of complete protection of CD4+ T cells in the CARD8-deficient immune system could also be attributed to the activation of other inflammasome sensors by HIV. For example, IFI16 and NLRP3 have been implicated in HIV-induced CD4+ T-cell pyroptosis45,46, but these two inflammasomes are only functional in certain subsets of CD4+ T cells and their ability to drive pyroptosis of human T cells remains unclear47,48.

While the function of various components of inflammasomes has been studied in T cells, the CARD8 inflammasome is best characterized to trigger pyroptosis in human lymphocytes49. In this regard, our work emphasizes the need for further investigation into CARD8 functionality in NHPs in vivo, as the paucity of available in vivo experimental systems and reagent limitations have hindered a more thorough investigation of this molecular pathway in these highly relevant models of HIV/AIDS pathogenesis. Of note, SIV can activate the CARD8 inflammasome of RMs and chimpanzee in vitro, thus laying the ground for future studies of the role of CARD8 in SIV pathogenesis, for instance by assessing the impact of CARD8 blockade and/or inhibition and/or gene targeting in RMs.

In conclusion, the current study defines a paradigm to explain the marked differences observed in the clinical outcomes of primate lentiviral infections between pathogenic hosts, such as humans and RMs, versus non-pathogenic, natural hosts, such as SMMs and AGMs. According to this paradigm, the progressive CD4+ T-cell depletion that characterizes pathogenic infections and involves predominantly cells that are not experiencing productive viral infection, is due to the activation of the CARD8 inflammasome which follows virus entry into CD4+ T-cells. The contribution of this mechanism of CD4+ T-cell depletion to the progressive immune deficiency which characterizes pathogenic lentiviral infections remains to be determined, as well as its relationship with previously described, non-mutually exclusive mechanisms of disease progression.

Limitations of the study

We have demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo how CARD8 drives CD4+ T-cell loss during HIV entry. A limitation of our work is that HIV infection in mice is accessed over a short period of time, which is because engraftment levels of human CD45+ cells decline over time in humanized mouse models due to suboptimal hematopoiesis and T cell development. Further in vivo experiments in non-human primates are needed to determine the precise role of CARD8 in pathogenesis of chronic HIV/SIV infections.

STAR ★ Methods

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Liang Shan (liang.shan@wustl.edu).

Materials availability

Requests of plasmids and cell lines generated in this study will be available upon request from the lead contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and code availability

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request. This paper does not report original code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and study participant details

Mice Strain

NSG-SGM3 mice were initially purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Strain #013062) and the colony was maintained at Washington University School of Medicine. Both male and female mice were included. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Washington University School of Medicine (approval #20–0224).

Human and non-human primate samples

Anonymous human cord blood samples were collected at the Cleveland Cord Blood Center. Anonymous peripheral blood samples were acquired from the Mississippi Valley Regional Blood Center as waste cellular products. Human tonsils were collected from elective tonsillectomies from Children’s Hospital in Saint Louis, which were provided as surgical waste without identifying information.

For the in vitro studies involving non-human primate samples, we used cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) that had been isolated from 30 ml blood collections obtained by standard venipuncture from Indian origin rhesus macaques (RMs) (Macaca mulatta) and sooty mangabeys (SMs) (Cercocebus atys) housed at the Emory National Primate Research Center (ENPRC) of Emory University, which is one of the seven centers belonging to the NIH-sponsored National Primate Research Center Program (NPRCP). All animals were housed according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) rules and regulations, and all blood collections were approved by existing IACUC protocols.

Cell lines

HEK 293T cells, Vero-E6 cells, CEM-174 cells, and ACH-2 cells were cultured in DMEM or RPMI containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. THP-1 cells, carrying doxycycline-inducible CARD8 expression cassettes were described previously37, were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. Blood or tonsil CD4+ T cells were isolated using a human CD4+ T-cell isolation kit. Purified CD4+ T cells were used without stimulation or co-stimulated with plate-bound CD3 and soluble CD28 antibodies in the presence of 20 ng/ml IL-2 for three days. Human CD34+ cells were isolated from cord blood using EasySep™ human cord blood CD34 positive selection kit, which was then cryopreserved in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM) containing 7.5% DMSO. The cryopreserved CD34+ cells were thawed and cultured in IMDM supplemented with 50 ng/ml SCF, 50 ng/ml Flt3L, and 50 ng/ml TPO for 12 hours before electroporation.

Method details

Phylogenetic analysis

The NHP species tree was generated from the NCBI taxonomy browser and adjusted for recently published data which has provided whole genome phylogenomic relationships of these species40,42. For the CARD8 gene trees, the NCBI and ensemble databases were used to collect the protein sequence of the longest isoform for each gene50. Each sequence entry can be found in Table S4 and S5. Sequences were aligned via ClustalW in MEGA1151. MEGA11’s “Find Best DNA/Protein Models (ML)” tool was used to identify the most appropriate phylogenetic tree method. For all cases, the best model was the Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) model with Gamma distribution. The Maximum likelihood trees were generated in MEGA11 with the JTT+G model with default settings. For primate phylogenies, Tupaia chinensis was selected for rooting and for the mammal phylogeny the monotremes were selected as the root. Newick trees were exported from MEGA11 and imported into python v3.8.5 and the ETE3 v3.1.3 toolkit was used to generate the phylogenetic trees52. Domain architecture was added via the ETE3 toolkit and was identified via the multiple sequence alignment of the sequences to the human reference. The corresponding locations were used as the predicted domain constraints. Trees were exported to adobe illustrator for cosmetic changes, branch distances were left untouched, and the addition of the species-specific silhouettes were obtained from PhlyoPic and the attribution and license information can be found at the following permalink: https://www.phylopic.org/permalinks/4e99be51d1c165798c1fea2747e55e9b95afb0b21c3248bea30cb0b757878ae8.

For the multiple sequence alignment visualizations, a subset of the CARD8 or IFI16 sequences was used for alignment as described above. The resulting alignments were visualized using the pymsaviz package v0.4.0 in python. Homology of IFI16 was assessed using NCBI BLASTP. The graphical overview of NHP CARD8 was created using BioRender and the speciation dates were calculated using previously published estimates.

Plasmids and viruses

To prepare replication-defective HIV reporter viruses, HEK 293T cells were transfected with pNL4-3-ΔEnv-EGFP (NIH HIV Reagent Program #11100), pNL4-3-ΔEnv-EGFP-RT-D110A-D185A or pNL4-3-ΔEnv-EGFP-IN-D116A, and the NL4-3 envelope expressing plasmid or pVSV-G. The replication-competent HIVNL4-3 was prepared by transfecting HEK293T with pNL4-3. The replication-competent HIVBaL was produced by infecting CD8-depleted PHA-stimulated PBMCs. The culture supernatant was collected six to nine days post-infection. The lentiviruses were also produced in HEK 293T cells by co-transfecting pLKO.1puro, psPAX2, and NL4-3 envelope expressing plasmid. Viral stocks were concentrated with the Lenti-X Concentrator. SIVagm Tan-1 GFP was described previously53. SIVmac 251 (NIH HIV Reagent Program #253) was used to infect CEM-174 cells for expansion, infected CEM-174 cells were replenished with uninfected CEM-174 cells every 2–3 days and the supernatant was collected and concentrated via the Lenti-X concentrator.

NHP CARD8 Sequence Verification

For identification of CARD8 sequences from Macaca mulatta, RT-PCR was conducted on total RNA isolated from stimulated PBMCS. Gene specific primers were then used to amplify the potential CARD8 constructs and were cloned using the Zero Blunt™ TOPO™ PCR Cloning Kit (Fisher #450245). Plasmids were then sent for whole plasmid sequencing by Plasmidsaurus. The cDNA sequence was translated to protein sequence using the Expasy translator tool54. For identification of CARD8 sequences from Cercocebus atys, sequences were obtained from previously published data. RNA-seq data for LPS-stimulated monocytes was previously submitted to the GEO database (accession numbers GSM2711028, GSM2711051, and GSE101617). Forward and reverse reads from each subject were aligned against the latest Cercocebus atys genome sequence (GCF_000955945.1_Caty_1.0) using STAR v2.7.9a55. Each subject had three samples which were combined when aligning. The aligned data was visualized using Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) v2.16.256 and the consensus sequences were extracted for all the exon regions for CARD8A. The exonic regions were combined and the non-DNA bases (Y, K, R, S, M, and W) were converted into standard nucleotide bases by comparing the respective positions of the CARD8 sequences from other subjects. Nucleotide sequences were translated to protein sequences using the Expasy translator tool54. Protein sequences were combined with the reference sequences for Homo sapiens, Macaca mulatta, and Cerecocebus atys as well as the CARD8A protein sequence derived from Macaca mulatta cDNA. CLUSTAL omega was used to align the protein sequences in MEGA v11. Alignment files were exported into FASTA format and imported into the pymsaviz package v0.4.0 in python for visualization. All CARD8 protein sequences can be found in Table S4.

NHP CARD8 construct generation

The longest isoform for each gene of CARD8 from each NHP species was synthesized using IDT or Genscript gene synthesis, the protein sequences can be found in Table S5. These constructs were ligated into the pcDNA 3.1 vector for mammalian expression as previously published. The N-terminal HA-FLAG tags were replaced by 3xHA tags to improve pull down and western blotting efficiency when the genes were synthesized. To generate dox-inducible CARD8 constructs for expression in CARD8-KO THP-1 cells, primers were used to alter the CARD8 sgRNA target site and placed into the doxycycline inducible vector as previously published. N-terminal CARD8 swapping was conducted via PCR to add on the N-terminal to the start of the FIIND domain to the other species FIIND-CARD for rhesus macaque and African green monkey CARD8. CARD domain swapping was conducted via PCR to add on the 3’ end of CARD8 after the FIIND domain (including the CARD if present) to the other species FIIND domain for rhesus macaque, African green monkey, and sooty mangabey CARD8A.

Immunoblotting and ELISA

For GSDMD cleavage detection, the unstimulated CD4+ T cells were spinoculated with X4-NL4-3-ΔEnv-EGFP reporter virus for two hours and incubated for another hour. For IL-1β cleavage assay, CARD8-KO HEK293T cells (4 × 105) were seeded in 12-well plates and cultured overnight before transfection. Each well was co-transfected with plasmids encoding CASP1 (2 ng), pro-IL-1β (200 ng), and WT or mutant CARD8 (5 ng), together with HIV-1 or SIVagmTan1-GFP (1μg). Cells were harvested 24 hours post-transfection. For autoprocessing westerns of NHP CARD8, HEK293T or Vero-E6 cells were transfected with NHP CARD8 (1μg) as above and protein was collected 24 hours post-transfection. For doxycycline-inducible expression CARD8WT, CARD8S297A, and CARD8F59GF60G in CARD8-KO THP-1 cells, cells were pre-treated with doxycycline (1 μg/ml) for two days and then treated with DMSO or indicated inhibitors for 30 minutes. The treated cells were then infected with VSVG pseudotyped NL4-3-ΔEnv-EGFP viruses for three hours. Doxycycline-treated THP-1 cells were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (50 ng/ml) for three hours, washed twice with PBS, and infected with VSVG pseudotyped NL4-3-ΔEnv-EGFP viruses for six hours. The culture supernatant was used for IL-1β ELISA. Mouse plasma IFN-gamma was measured using a human IFN-gamma Quantikine ELISA Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell viability and LDH release assay

For the assessment of the cell viability, cells were washed with PBS and incubated with Zombie Violet for 30 minutes in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell viability measurement is based on the detection of ATP by the CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Kit, or from the CyQUANT LDH Cytotoxicity Assay kit. For the Annexin V and Propidium Iodide staining, cells were washed with PBS and then incubated with Annexin V and Propidium Iodide (PI) in Annexin V Binding Buffer for 15 min at room temperature. Adding Annexin V Binding Buffer and the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. The supernatants were collected after infection to determine the activity of LDH, and the LDH assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To test VbP activation of dox-inducible NHP CARD8, cells were treated with doxycycline as above for two days prior to treatment with VbP for six hours.

HIV fusion assay

A reporter plasmid BLaM-Vpr was used to quantify the entry of the viruses into the cells. After pre-treating CD4+ T cells with different drugs for 30 minutes, the cells were infected with virions containing BLaM-Vpr for four hours. The cells were washed in a CO2-independent medium and then incubated for one hour at room temperature with 100 μl CCF2/AM dye. Afterward, the cells were washed in RPMI and incubated overnight in a CO2-independent medium containing 10% FBS at room temperature. Flow cytometry was used to detect the green-to-blue color change as an indication of viral entry.

In vitro assessment of CARD8 cleavage by HIV and SIV protease

Human and NHP CARD8, HIV and SIV protease were purified to assess cleavage in vitro. To express and purify HIV and SIV protease, HIV or SIV codon-optimized protease was cloned into pST50Trc by using BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites. Protease expression and purification were performed as previously described for HIV-1 protease57,58. Freshly purified protease was used for CARD8 cleavage. To purify CARD8 proteins, HEK293T cells were transfected with 10 μg of plasmids encoding the HA-tagged CARD8 in 10-cm dishes. Two days after transfection, cells were collected and lysed in 1x RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with 0.5 mM DTT and complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail. CARD8 was immunoprecipitated using 40 μL of Protein G Dynabeads® conjugated with a mouse anti-HA antibody. After immunoprecipitation, beads were washed three times with 1x RIPA buffer and once with protease cleavage buffer (50 mM sodium acetate, 50 mM Na-MES, 100 mM Tris, 2 mM beta-mercaptoethanol, pH 6.5). Beads were then resuspended in 200 μL of protease cleavage buffer for the cleavage assay. To perform cleavage, 10 μL viral protease was added on top of the beads bearing immunoprecipitated CARD8 and incubated at 30°C for 30 minutes on a thermal mixer set at 1200 rpm. The eluate from the beads were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Co-culture for CD4+ T-cell depletion in human CD4+ T cells

Replication-competent HIVNL4-3 and HIVBaL were used for co-culture experiments. Activated CD4+ T cells were infected with HIVNL4-3 or HIVBaL for three days to reach 20%−30% infection by intracellular p24 staining. HIV-infected CD4+ T cells were used as effector cells. A total of 2 × 105 donor-matched PBMCs or ToMCs were labeled with CFSE, pre-treated with different inhibitors for 30 minutes, and then co-cultured with 2 × 105 HIV-infected cells for six hours in a U-bottom 96-well plate without any cytokines. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the CD4 to CD8 ratio and the percentage of CCR5-positive cells within CFSE-positive cells. For ACH-2 and PBMC co-culture, 5 × 105 ACH-2 cells were stimulated with 50 ng/ml PMA for 24 hours as effector cells. A total of 2 × 105 PBMCs were labeled with CFSE (target cells) and treated with different inhibitors and then co-cultured with PMA-stimulated ACH-2 cells for six hours in a U-bottom 96-well plate. The CD4 and CD8 ratios of the harvested cells were determined by flow cytometry.

Co-culture for CD4+ T-cell depletion in NHP PBMCs

CEM-174 cells were infected with SIVmac251 or HIVNL4-3 for 6–9 days. Additional uninfected CEM-174 cells were added to the infected culture every 2–3 days depending on cell viability to allow for expansion of the viruses. Human and NHP PBMCs were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin in the presence of IL-7 and IL-15. For co-culture, 105 PBMC were labelled with CFSE and treated with 50 μM VX765 and co-cultured with 5 × 105 SIV- or HIVNL4-3-infected CEM-174 cells for 16 hours. Flow cytometry analysis was conducted as with the human co-culture experiments.

Exposure to cell-free HIV virions

For the exposure to cell-free HIV virions, replication-defective HIV reporter virus NL4-3-ΔEnv-GFP pseudotyped with the NL4-3 envelope or VSV-G was used for CD4+ T cells or THP-1 cells, respectively. Unstimulated CD4+ T cells or THP-1 cells were pre-treated with different ARVs or other inhibitors for 30 minutes and then were exposed to viruses in the 96-U-bottom plate by two hours of spinoculation and four hours of incubation before flow cytometry analysis and LDH measurement. 1000 ng HIVp24 per million cells was used unless noted otherwise. The following inhibitor concentrations were used: AMD3100 5 μM, T20 5 μM, TFV 1 μM, NVP 5 μM, EFV 5 μM, RAL 5 μM, LPV 5 μM, VX765 50 μM, MG132 10 μM, and VbP 5 μM. 1G244 was used at 500 nM unless noted otherwise.

CRISPR knockout in CD4+ T cells and CD34+ cells

Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes were electroporated into CD4+ T cells and CD34+ cells using the Lonza 4D Nucleofector system. The recombinant Cas9 protein was obtained from IDT. The modified synthetic sgRNAs were purchased from Synthego and the sequences are listed in Table S1. RNP complexes were prepared by mixing Cas9 (40 pmol) with sgRNA (100 pmol) and incubating them for 10 minutes at room temperature. 2 × 106 unstimulated CD4+ T cells or 0.2 × 106 CD34+ cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 20 μl buffer P3 (Lonza #V4XP-3032). To deliver two specific sgRNAs targeting one gene, 2 μl of each RNP complex were then mixed with the cell suspension and transferred into a 16-well reaction cuvette of the 4D-Nucleofector System. The CD4+ T cells and CD34+ cells were electroplated using the programs EH-100 and DZ-100, respectively. After electroporation, CD4+ T cells and CD34+ cells were resuspended in 100 μl of prewarmed RPMI 1640 or IMDM and transferred to a 96-well plate to recover for 30 minutes at 37°C. The electroporated CD4+ T cells were cultured for three to four weeks under low concentrations of human IL-7 (2 ng/mL) and IL-15 (2 ng/mL) before in vitro testing. The electroporated CD34+ cells were then washed with PBS before being transplanted into the mice.

Flow cytometry analysis

The mouse tissue cell suspensions were first incubated with Zombie NIR in PBS for 30 minutes at 4°C, followed by incubation with Human TruStain FcX and TruStain FcX (anti-mouse CD16/32) blocking antibodies for 10 min at room temperature. The cell suspensions were then incubated at 4°C with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies for 30 minutes to stain surface antigens. In all experiments, stained cells were acquired on a BD LSR Fortessa, X20, or Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences), and data were analyzed by the FlowJo software.

Immunohistochemistry

Mouse spleens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with human CD4 antibody by Washington University Anatomic and Molecular Pathology (AMP) Core Labs. Images were acquired using the Zeiss Axio Scan Z1 Brightfield slide scanner. The positively stained area was quantified using Image J software.

Generation and HIV infection of humanized mice

One- to three-day-old newborn NSG-SGM3 mice were preconditioned with sublethal irradiation (100 cGy) followed by an intrahepatic injection of 3–4×104 unmodified or Cas9-edited CD34+ cells. Reconstitution of human CD45+, CD3+, and CD4+ T cells was assessed 10 to 12 weeks after engraftment. Experimental groups were assigned randomly.

Engrafted mice were infected with HIVBaL (10 ng p24/mouse) through retro-orbital injection. Blood samples were collected by retro-orbital or submandibular vein bleeding to quantify plasma HIV RNA. The plasma viral RNA was extracted using a Quick-RNA Viral Kit (Zymo Research) and reverse transcribed using the ProtoScript II Reverse Transcriptase (NEB). A ten-fold serial dilution of HIV genomic DNA served as a standard for measuring plasma viral RNA by the HIV gag-based qPCR assay59. Three cohorts of mice were used for HIV infection as shown in Figure 5. Cohort 1: Cas9 ctrl (n=9), CARD8-KO (n=9); Cohort 2: Cas9 ctrl (n=3), CARD8-KO (n=3); Cohort 3: Cas9 ctrl (n=5), CARD8-KO (n=6).

Amplicon deep sequencing

In the first step, corresponding primers were used for the CARD8 loci (CARD8-F and CARD8-R). In a second round of PCR using primers (Table S2) containing sample-specific barcodes and adapters, amplicons were sequenced for 2 × 150 paired-end reads with MiSeq Sequencing (Illumina). The CRISPResso software was used to analyze the deep sequencing data60.

Quantification and statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using Prism 9. Phylogenetic statistics and analysis were performed as above. The methods for statistical analysis are described in the figure legends. The error bars indicate the standard error of the mean.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. HIV entry induces rapid loss of CD4+ T cells, related to Figure 1 (A-B) PBMCs labeled with CFSE were treated with AMD3100 or DMSO for 30 minutes and co-cultured with HIVNL4-3 infected or uninfected autologous CD4+ T cells for six hours at the indicated E: T ratio. In A, representative flow cytometry plots of the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in PBMCs. In B, CD4 to CD8 ratio at the indicated E: T ratio.

(C-F) Co-culture of PMA-stimulated ACH-2 cells and CFSE-labeled PBMCs. ACH-2 cells were stimulated with DMSO or PMA (50 ng/ml) for 24 hours and then co-cultured with CFSE-labeled PBMCs or ToMCs for six hours. Cells were harvested to determine the percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by flow cytometry. In D, CD4 to CD8 ratio in CFSE-labeled PBMCs. In E and F, CARD8-KO or Cas9 ctrl CD4+ T cells from blood or tonsils were mixed with donor-matched CD8+ T cells before co-culture with ACH-2 cells as described above.

p values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison tests. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, **** p < 0.0001. Error bars show mean values with SEM. n=3.

Figure S2. CARD8 inflammasome is required for HIV entry-induced CD4+ T-cell death, related to Figure 2 (A) The co-culture of Cas9-edited unstimulated CD4+ T cells and HIV-1-infected autologous CD4+ T cells were described in Figure 2C. The CD4 to CD8 ratio after co-culture for 48 hours with the presence of raltegravir (5 μM) was shown.

(B and C) NLRP3 and IFI16 knockout efficiency was confirmed in the blood (B) or tonsil (C) by immunoblotting.

(D and E) The co-culture of Cas9-edited unstimulated CD4+ T cells and HIV-infected autologous blood (D) or tonsillar (E) CD4+ T cells for six hours as described above. p values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison test. **** p < 0.0001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, ns: not significant. Error bars show mean values with SEM from three or four independent donors.

Figure S3. HIV-1 protease encapsulated in incoming viral particles causes pyroptosis of CD4+ T cells upon viral entry, related to Figure 3 (A) Quantification of HIV entry. Representative flow cytometry plots of CCF2 substrate cleavage by BlaM in infected blood CD4+ T cells.

(B and C) Unstimulated CD4+ T cells were pre-treated with ARVs and then exposed to HIV reporter viruses for four hours before CASP1 and Zombie staining.

(D-F) Unstimulated CD4+ T cells were exposed to HIV reporter viruses with indicated mutations or a lentivirus. In D, cell viability (Zombie) and active CASP1 expression were measured four hours after exposure. In E and F, GFP expression was measured three days post-infection.

(G and H) Cell viability (Zombie), active CASP1 expression, and LDH release in unstimulated CD4+ T cells pre-treated with VX765 or MG132 before infection.

(I) GSDMD cleavage from cell lysates by immunoblotting.

(J and K) Cell viability (Zombie) of genetically modified unstimulated CD4+ T cells after exposure to HIV reporter viruses for four hours (J) or 72 hours (K) in the presence of RAL. (L) Cell-killing dose-response curves for 1G244 with or without exposure to HIV reporter viruses.

From B-L, unstimulated CD4+ T cells were exposed to HIV reporter virus NL4-3-ΔEnv-EGFP with indicated mutations or a lentivirus pseudotyped with the NL4-3 envelope.

(M) THP-1 cells expressing dox-inducible CARD8 expression cassette were pre-treated with dox (1 μg/ml) for 48 hours and then were exposed to NL4-3-ΔEnv-EGFP pseudotyped with VSV-G for six hours in the presence of the indicated drugs. Cells were collected to detect CARD8 cleavage by immunoblotting.

In C, G, J, and K, p values were calculated using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. In D and H, p values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison tests. **** p < 0.001. Error bars show mean values with SEM. n=3.

Figure S4. Activated CD4+ T-cell is resistant to pyroptosis mediated by CARD8, related to Figure 4 (A) CASP1-KO or Cas9 ctrl unstimulated CD4+ T cells from blood were infected with HIVNL4-3 or HIVBaL at 40 ng HIVp24 per million cells. Infection was measured by intracellular p24 staining.

(B) CARD8-KO or Cas9 ctrl unstimulated CD4+ T cells were infected with the indicated amount of NL4-3-ΔEnv-EGFP pseudotyped with the NL4-3 envelope for four hours with or without 1G244 (500 nM). GFP was measured on day 3 post-infection by flow cytometry.

(C) Immunoblotting of CD4+ T cells from healthy donors following anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies stimulation.

(D) Unstimulated or stimulated CD4+ T cells were mixed with donor-matched CD8+ T cells before co-culture with HIVNL4-3-infected CD4+ T cells from the same donor. The CD4 to CD8 ratio was determined six hours after co-culture by flow cytometry.

In A and B, p values were calculated using two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison tests. In D, p values were calculated using unpaired t-tests. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Error bars show mean values with SEM. n=3.

Figure S5. HIV pathogenesis in humanized NSG-SGM3 mice, related to Figure 5 Newborn NSG-SGM3 mice were preconditioned and engrafted with human cord blood CD34+ cells. Mice were infected with HIVBaL 12 weeks post engraftment.

(A) Frequency of CD4+ T cells in T cells and total white blood cells in the blood were shown. Uninfected, n=5; Infected, n=4.

(B) Plasma IFNγ increases post-HIV infection. Plasma samples from infected and uninfected mice were collected at week 3 post-infection for ELISA. Uninfected, n=6; Infected, n=10.

(C-E) Loss of CD4+ T cells in tissues post HIV infection. In C and D, spleens were collected at the indicated times for histology and immunohistochemistry using anti-huCD4 antibody. Scale bars: 50 μm. Quantification of human CD4-stained sections was performed using ImageJ. Uninfected, n=4; Infected, n=4. In E, tissues were collected four weeks post-infection to determine the numbers of CD4+ T cells. Uninfected, n=3; Infected, n=4.

In A and D, p values were calculated using the two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison tests. In B and E, p values were calculated using unpaired t-tests. * p < 0.05, **** p < 0.0001. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ns: not significant. Error bars show mean values with SEM.

Figure S6. Reconstitution of CARD8-KO human immune system in mice for HIV infection, related to Figure 5 (A) A summary of indels detected by sequencing of blood cells from mice engrafted with CARD8-KO CD34+ cells.

(B-E) Human cell reconstitution in mice engrafted with CARD8-KO or Cas9 ctrl CD34+ cells. Mice were not infected with HIV. Tissues were collected 12 weeks after engraftment for flow cytometry analyses. Cas9 ctrl, n=5; CARD8-KO, n=4.

(F) Frequency of CD4+ T cells in the blood of the three mouse cohorts before HIV infection. Cas9 ctrl, n=17; CARD8-KO, n=18.

(G) Frequency of CD4+ T cells in the blood during HIV infection. The solid lines denote mean values. Cas9 ctrl, n=9; CARD8-KO, n=9.

(H) Percentage of human CD45RO−CCR7+ cells in the tissues of HIV-infected mice. Cells were gated on the human CD45+CD3+CD4+ population. Cas9 ctrl, n=10; CARD8-KO, n=10, except for BM (n=9). Data were pooled from 2 independent mouse cohorts.

In G, p values were calculated using the two-way ANOVA with Šidák’s multiple comparison tests. Other p values were calculated using an unpaired t-test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. Error bars show mean values with SEM.

Figure S7. CARD8 functions in NHPs, related to Figure 6 and 7 (A) Expected evolutionary relationships of primate species based on the NCBI taxonomy browser and recent analyses of whole genome phylogenomics40–42. Geographic locations of each species are indicated by dashed lines.

(B) Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree for the multiple sequence alignments of non-human primate IFI16 protein sequences. Known pathogenic hosts are highlighted in red and known non-pathogenic hosts are highlighted in blue. This tree shows very few differences from the expected evolutionary relationships seen in a) and indicates far less genetic variation than the phylogenetic trees for CARD8. The sequences used to construct this tree may be found in Table S5.

(c) Autoprocessing of NHP CARD8. Vero cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-tagged CARD8 from Hu and CPZ, and CARD8A and CARD8B from RM, SMM, and AGM.

(D) Activation of human and NHP CARD8 inflammasome by HIV and SIV. CARD8-KO HEK 293T cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding CASP1, pro–IL-1β, and human or NHP CARD8 with or without cleavage site mutations, together with HIV or SIV plasmids.

(E) Autoprocessing of NHP CARD8 constructs with CARD domain swaps. The 3’ terminus following the FIIND domain was swapped for AGM and SMM with that of RM.

(F) In vitro cleavage by SIV protease. Purified CARD8 proteins and SIV protease were incubated for one hour before immunoblotting.

(G) The co-culture schemes. CEM-174 cells were infected with either HIVNL4-3 or SIVmac251 for six days. Virus-producing cells were then co-cultured at a 5:1 ratio with CFSE-labeled human or RM PBMCs for 12–16 hrs.

(H) Rapid loss of RM CD4+ T cells. Co-culture of PBMCs from five RMs with SIVmac251-infected CEM-174 cells. CD4/CD8 ratio was measured 12–16 hours post co-culture. p values were calculated using an unpaired two-tailed t-test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001. Error bars show mean values with SEM.

Table S1. sgRNA sequences, related to STAR Methods.

Table S2. Primers for MiSeq, related to STAR Methods.

Table S3. Primers for primate CARD8 cloning, related to STAR Methods.

Table S4. Mammal CARD8 protein sequences, related to Figure 6.

Table S5. NHP CARD8 protein sequences, related to Figure 6.

Table S6. NHP IFI16 protein sequences, related to Figure 6.

Table S7. Individual SMM CARD8 sequences, related to Figure 7.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-CARD8 | Abcam | Cat# ab24186; RRID: AB_2275096 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-HA | BioLegend | Cat#901502; RRID: AB_2565007 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-CASP1 | Abcam | Cat#ab179515; RRID: AB_2884954 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-NLRP1 | BioLegend | Cat# ab 679802; RRID: AB_2566263 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-ASC | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 13833; RRID: AB_2798325 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-IFI16 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 14970; RRID: AB_2798669 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-NLRP3 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 13158; RRID: AB_2798134 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-pro-IL-1β | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat #12703; RRID: AB_2737350 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-IL-1β | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat #83186: RRID: AB_2800010 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-GSDMD | Novus Biologicals | Cat# NBP2–33422; RRID: AB_2687913 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Beta-actin | Invitrogen | Cat# MA1–140; RRID: AB_2536844 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-HA | BioLegend | Cat# 901515; RRID: AB_2565334 |

| HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 7076; RRID: AB_330924 |

| HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 7074; RRID: AB_2099233 |

| Human TruStain FcX | BioLegend | Cat# 422302; RRID: AB_2818986 |

| TruStain FcX anti-mouse CD16/32 | BioLegend | Cat# 101320; RRID: AB_1574975 |

| anti-mouse CD45-FITC | BioLegend | Cat# 103108; RRID: AB_312973 |

| anti-human CD45-Pacific Blue | BioLegend | Cat# 304029; RRID: AB_2174123 |

| anti-human CD3-BV650 | BioLegend | Cat# 317324; RRID: AB_2563352 |

| anti-human CCR5-PECy7 | BioLegend | Cat# 359108; RRID: AB_2562652 |

| anti-human CD45RO-PE | BioLegend | Cat# 304206; RRID: AB_314422 |

| anti-human CCR7-Alexa 647 | BioLegend | Cat# 353218; RRID: AB_10917385 |

| anti-human CD8-BUV395 | BD Biosciences | Cat# 563795; RRID: AB_2722501 |

| anti-human CD3 | BioLegend | Cat# 300333; RRID: AB_2616669 |

| anti-human CD28 | BioLegend | Cat# 302943; RRID: AB_2616667 |

| anti-p24-PE | Beckman Coulter | Cat# KC57-RD1; RRID: AB_1575989 |

| anti-human CD8-BV421 | BD Biosciences | Cat#562428; RRID: AB_11154035 |

| anti-human CD4-BUV395 | BD Biosciences | Cat#564107; RRID: AB_2738596 |

| anti-human CD4 | Ventana | Cat#790–4423; RRID: AB_2335982 |

| anti-human CD3-BUV737 | BD Biosciences | Cat#568353; RRID: N/A |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||