Summary

The WHO Western Pacific region bears disproportionate deaths from non-communicable diseases (NCDs), with increased overall NCD proportional mortality over the past two decades. The disease burden of mental health increased, resulting from rapid ageing, enhanced stress, and the COVID-19 pandemic, but it was largely neglected. The highly diverse cultures, religions, political systems, socioeconomic contexts, lifestyles, and environmental factors probably have led to massive disparities across countries in NCD mortality, risk factors, and NCD management. Geographically, East Asia had the lowest NCD mortality whilst Pacific islands had the highest. Economic booms, ageing, nutrition transition, social stress, prevalent tobacco use, and fast-increasing obesity and hyperglycaemia are important drivers of NCDs. Men tended to have more adverse behavioural and metabolic risk factors. Rural residents are catching up with their urban counterparts in metabolic risk factors and conditions. Sustainable strategies tailored to NCD patterns are needed to fight the NCD epidemic and related disparities.

Keywords: Non-communicable diseases, Trends, Disparity, Risk factors, The Western Pacific region

Introduction

Fighting non-communicable diseases (NCDs) is a public health priority worldwide and has particular relevance for the Western Pacific region. The United Nations has called on all countries to make a sincere effort to fight the growing NCD epidemic and included NCD prevention and control in the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.4.1 In concordance with global reported data, NCDs are the leading causes of death and disability in the region. Indeed, in this most populous area among the six WHO regions, the Western Pacific region data represent 1/4 of global NCD deaths. The four major NCDs–cardiovascular disease (CVD), cancers, chronic respiratory diseases, and diabetes–accounted for 12 million deaths in this region in 2019.2 The burden of mental health problems, as the fifth major NCD in the new 5 × 5 approach to NCDs favoured by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2018,3 is relatively high and rising currently in the region.

The Western Pacific region distinguishes itself from other WHO regions by its large population, great diversity, and fast-growing economy. The region consists of 37 countries and areas (see Table 1), with nearly 1.9 billion total population. The geographical variance, multiple political systems and levels of socioeconomic development, complex ethnicities, languages, beliefs, cultures, lifestyles, and health statuses in this region probably have led to great disparities in NCD-related health outcomes across countries. Specifically, the gap in life expectancy was as high as 20.1 years in 2019 with the lowest 64.3 years in Tuvalu, and the highest 84.4 years in Japan.4 The mortality rates from NCDs also varied largely across countries in this region.5

Table 1.

Profiles of 37 countries and areas in the Western Pacific region.

| No. | Country/area | Populationa | Year of Populationa | GDP per capita ($)b | Year of GDPb | Income groupb | Land area (km2)b | Ethnicityc | Major religionc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | American Samoa (USA) | 55,519 | 2010 | 12,844.90 | 2020 | UMIC | 2934 | Pacific Islander (includes Samoan, Tangan), Asian 3.6%, mixed, other | Christian |

| 2 | Australia | 23,717,421 | 2016 | 59,934.10 | 2021 | HIC | 7,692,020 | English, Australian, Irish, Scottish, Chinese, other | Protestant, Roman Catholic |

| 3 | Brunei Darussalam | 429,999 | 2021 | 31,722.40 | 2021 | HIC | 5270 | Malay, Chinese, other | Muslim |

| 4 | Cambodia | 15,552,211 | 2019 | 1591.00 | 2021 | LMIC | 5270 | Khmer, Cham, Chinese, other | Buddhist |

| 5 | China | 1,411,778,724 | 2020 | 12,556.30 | 2021 | UMIC | 5270 | Han Chinese, ethnic minorities | Folk religion, Buddhist |

| 6 | Cook Islands | 17,434 | 2016 | – | – | – | – | Cook Island Maori (Polynesian), part Cook Island Maori, other | Protestant, Roman Catholic |

| 7 | Fiji | 884,887 | 2017 | 5086.00 | 2021 | UMIC | 18,270 | iTaukei, Indo-Fijian, Rotuman, other | Protestant, Hindu, other Christian, Roman Catholic, Muslim |

| 8 | French Polynesia (France) | 281,674 | 2017 | 20,182.60 | 2020 | HIC | 3471 | Polynesian, Chinese, local French, metropolitan French | Protestant, Roman Catholic |

| 9 | Guam (USA) | 153,836 | 2020 | 34,624.30 | 2020 | HIC | 540 | Chamorro, Filipino, White, Chuukese, Korean, other Pacific Islander | Christian, folk religions, Buddhist |

| 10 | Hong Kong SAR (China) | 7,336,585 | 2016 | 49,660.60 | 2021 | HIC | 1050 | Chinese, Filipino, Indonesian, and other | Buddhist or Taoist, Protestant, Roman Catholic, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh |

| 11 | Japan | 126,226,568 | 2020 | 39,285.20 | 2021 | HIC | 364,500 | Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and other | Shintoism, Buddhism |

| 12 | Kiribati | 119,940 | 2020 | 1514.60 | 2020 | LMIC | 810 | I-Kiribati, I-Kiribati/mixed, Tuvaluan, other | Roman Catholic, Kiribati Uniting Church |

| 13 | Lao People's Democratic Republic | 6,492,228 | 2015 | 2551.30 | 2021 | LMIC | 230,800 | Lao, Khmou, Hmong, Phouyhay, Tai, Makong, Katong, Lue, Akha, other | Buddhist |

| 14 | Macao SAR (China) | 650,834 | 2016 | 45,421.60 | 2021 | HIC | 33 | Chinese, Portuguese, mixed, other | Folk religion, Buddhist, Christian |

| 15 | Malaysia | 28,334,135 | 2010 | 11,371.10 | 2021 | UMIC | 328,550 | Bumiputera, Chinese, Indian, other | Muslim, Buddhist, Christian, Hindu |

| 16 | Marshall Islands | 53,158 | 2011 | 4171.00 | 2021 | UMIC | 180 | Marshallese, mixed Marshallese, other | Protestant, Roman Catholic |

| 17 | The Federated States of Micronesia | 102,843 | 2010 | 3476.70 | 2021 | LMIC | 700 | Chuukese/Mortlockese, Pohnpeian, Kosraean, Yapese, Yape outer islanders, Polynesian, Asian, other | Roman Catholic, Protestant |

| 18 | Mongolia | 271,407 | 2020 | 4534.90 | 2021 | LMIC | 1,557,507 | Khalkh, Kazak, Durvud, Bayad, Buriad, Zakhchin, Dariganga, other | Buddhist |

| 19 | Nauru | 271,407 | 2011 | 12,252.30 | 2021 | HIC | 20 | Nauruan, part Nauruan, I-Kiribati, other | Protestant, Roman Catholic |

| 20 | New Caledonia (France) | 271,407 | 2019 | 272,620.00 | 2021 | HIC | 18,280 | Kanak, European, Wallisian, Futunian, Tahitian, Indonesian, Ni-Vanuatu, Vietnamese, other | Christian |

| 21 | New Zealand | 4,793,358 | 2018 | 48,801.70 | 2021 | HIC | 263,310 | European, Maori, Chinese, Indian, Samoan, Tongan, Cook Island Maor, English, Filipino, New Zealander, other | Christian |

| 22 | Niue | 1719 | 2017 | – | – | – | – | Niuean, part-Niuean, non-Niuean | Ekalesia Niue, Church of Jesus Christ, Roman Catholic |

| 23 | Northern Mariana Islands | 53,883 | 2010 | 20,659.60 | 2019 | HIC | 460 | Asian, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, other | Christian |

| 24 | Palau | 17,661 | 2015 | 14,243.90 | 2020 | UMIC | 460 | Palauan, Filipino, Chinese, other | Roman Catholic, Protestant |

| 25 | Papua New Guinea | 7,275,324 | 2011 | 2916.40 | 2021 | LMIC | 452,860 | Melanesian, Papuan, Negrito, Micronesian, Polynesian | Protestant, Roman Catholic |

| 26 | Philippines | 109,035,343 | 2020 | 3548.80 | 2021 | LMIC | 298,170 | Tagalog, Bisaya, Cebuano, Llocano, Hiligaynon, Bikol, Waray, other local ethnicity, other foreign ethnicity | Roman Catholic |

| 27 | Pitcairn Island (UK) | 45 | 2020 | – | – | – | – | Descendants of the Bounty mutineers and their Tahitian wives | Seventh Day Adventist |

| 28 | Republic of Korea | 51,829,136 | 2020 | 34,757.70 | 2021 | HIC | 97,600 | Homogeneous | Protestant, Buddhist, Catholic |

| 29 | Samoa | 195,979 | 2016 | 3939.10 | 2021 | LMIC | 2780 | Samoan, Samoan/New Zealander, other | Protestant, Roman Catholic |

| 30 | Singapore | 4,044,210 | 2020 | 72,794.00 | 2021 | HIC | 718 | Chinese, Malay, Indian, other | Buddhist, Christian, Muslim, Taoist, Hindu |

| 31 | Solomon Islands | 515,870 | 2009 | 2337.00 | 2021 | LMIC | 27,990 | Melanesian, Polynesian, Micronesian, other | Protestant, Roman Catholic |

| 32 | Tokelau (New Zealand) | 1285 | 2016 | – | – | – | – | Tokelauan, part Tokelauan/Samoan, part Tokelauan/Tuvaluan, Tuvaluan, Kiribati, other | Congregational Christian Church, Roman Catholic |

| 33 | Tonga | 100,651 | 2016 | 4624.80 | 2020 | UMIC | 720 | Tongan, part-Tongan, other | Protestant, Church of Jesus Christ, Roman Catholic |

| 34 | Tuvalu | 10,645 | 2017 | 5291.50 | 2021 | UMIC | 30 | Tuvaluan, Tuvaluan/I-Kiribati, Tuvaluan/other, other | Protestant |

| 35 | Vanuatu | 272,459 | 2016 | 3127.40 | 2021 | LMIC | 12,190 | Melanesian, non-Melanesian | Protestant |

| 36 | Viet Nam | 96,208,984 | 2019 | 3694.00 | 2021 | LMIC | 313,429 | Kinh, Tay, Thai, Muong, Khmer, Mong, Nung, other | Catholic, Buddhist, Protestant, other |

| 37 | Wallis and Futuna (France) | 11,562 | 2018 | – | – | – | – | Polynesian | Roman Catholic |

Income groups were per World Bank definitions in 2022; HIC: high-income economies. UMIC: upper-middle-income economies. LMIC: lower-middle-income economies.

Data from the Demographic Statistics Database of the United Nations Statistics Division (https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-social/products/dyb/#censusdatasets).

Data from the World Bank (https://datahelpdesk.world_x0002_bank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-countryand-lending-groups).

Data from the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States (https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/).

To understand the complexity of the large NCD burden and related disparities in the Western Pacific region to inform strategies that could facilitate a healthier future, this study (see Panel 1 and Supplementary File 1) examined the trends and disparities in NCDs in this region and explored their related major risk factors at different levels.

Panel 1. Search strategy and selection criteria.

We searched English (World Health Organization Global Health Data Exchange databases, PubMed, Web of Science, and Google Scholar), and Chinese databases (National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and Wanfang) from their inception to May 29, 2023, using the following search terms and their combinations: “NCD,” “non-communicable diseases,” “CVD,” “cardiovascular diseases,” “hypertension,” “obesity,” “overweight,” “BMI,” “diabetes,” “respiratory diseases,” “COPD,” “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,” “cancer,” “tumor,” “neoplasms,” “nervous,” “neurological,” “mental health,” “psychiatric disorders,” “epidemiology,” “prevalence,” “awareness,” “treatment,” “control,” “Western Pacific region,” and names of all 37 countries and areas in the Western Pacific region. We also examined the reference lists of relevant literature and received advice on other data sources from experts on this research topic. Important publications and other data sources were included. Additionally, we systematically reviewed the published manuscripts about the prevalence and management of hypertension and diabetes in countries in the Western Pacific region from the online databases PubMed and Web of Science. We selected relevant studies by reviewing the titles, abstracts, and full texts. Flowchart of the included literature on hypertension prevalence and management is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Current status and trends of NCD mortality in the Western Pacific region

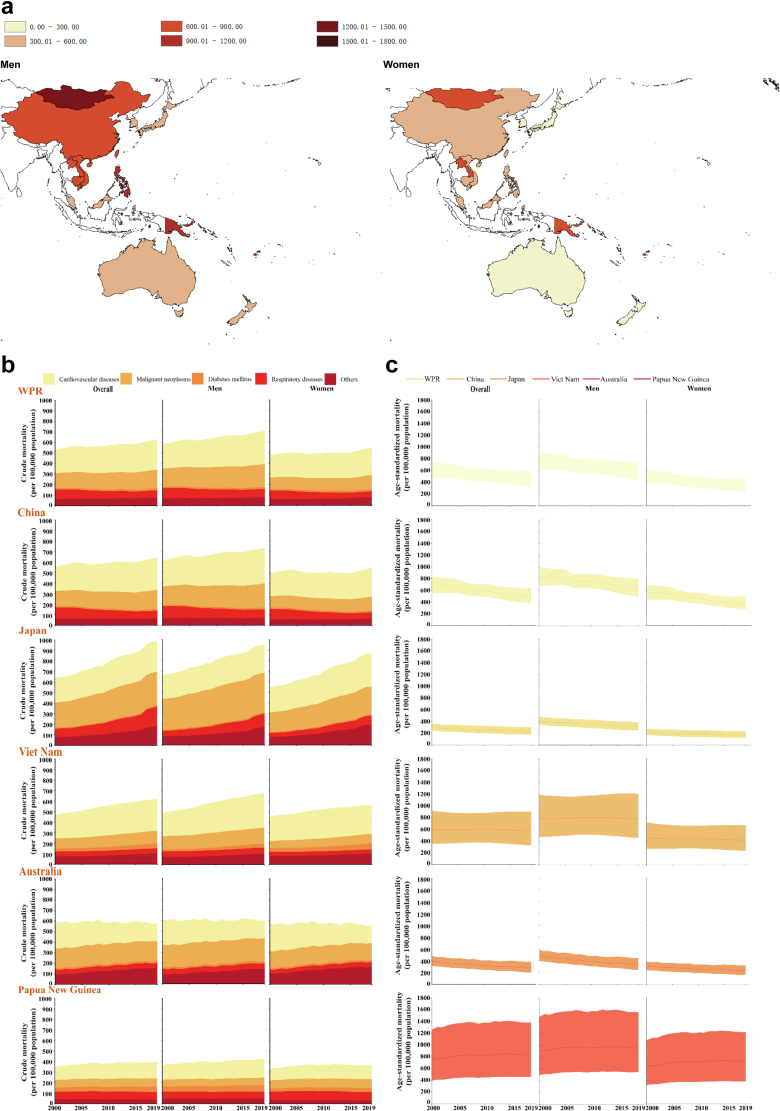

NCD mortality, as the endpoint of comprehensive NCD burden including NCD prevention and control, was selected as one of the most accurate measurements to assess successful and failed strategies. NCD mortality data is available for almost all countries and areas thus allowing for comparative analysis. Using WHO data,6 we described the status and trends of NCD mortality in the Western Pacific region, highlighted five selected countries (Australia, China, Japan, Papua New Guinea, and Viet Nam), compared and contrasted their conditions against global and other regions, and discussed their experiences and lessons (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Current status and trends of NCD mortality in Western Pacific region and its 37 respective countries/areas in the Western Pacific region. a. Status in age-standardised mortality rates due to non-communicable diseases by sex in 21 countries and areas in the Western Pacific region in 2019. b. Compositional NCD crude mortality by sex in Western Pacific region and 5 select countries, 2000–2019. c. Overall age-standardised NCD mortality by sex in Western Pacific region and 5 selected countries, 2000–2019. Data on mortality rates were obtained from the World Health Organization Noncommunicable diseases: Mortality (https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/ncd-mortality).

Overall patterns of NCDs in the Western Pacific region

The four major NCDs in the Western Pacific region accounted for the vast majority and a disproportionately higher proportion of deaths as compared with global data (87.0% vs. 75.0%), and the proportion ranked the 2nd highest among all six WHO regions.5 The WHO data from the Global Health Observatory (Fig. 1A, data in Supplementary Table S1A) shows that men had overall higher age-standardised mortality from NCDs than women, which was in line with the global distribution by sex.6 The five lowest-ranking countries and areas in age-standardised mortality from NCDs in this region for both women and men were Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, and the Republic of Korea; while the highest-ranking for women were Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Kiribati, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu, and for men were Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Kiribati, Mongolia, and Vanuatu.

Consistent with global trends and in other WHO regions, the proportional mortality from NCDs in the past decades in the Western Pacific region increased from 79.8% in the year 2000 to 87.4% in the year 2019 according to Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study results.7 Disaggregating the proportional mortality from CVD, cancers, and diabetes increased, and chronic respiratory disease decreased over time. Meanwhile, the crude NCD mortality continuously increased but age standardised NCD mortality decreased in this region (Fig. 1B and C, data in Supplementary Table S1B and C). This paradoxical phenomenon could be a result of the ongoing progress of the demographic transition towards an ageing population, and the epidemiological transition from communicable diseases to NCDs globally including in the Western Pacific region, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and countries in transition.8

Conditions of NCDs in five selected countries

We selected five countries in the Western Pacific region to examine the status and trends in NCD mortality (Fig. 1B and C, data in Supplementary Table 2B and C). They are countries representative of the variation in stages of ageing, economic development, geographical/environmental characteristics, and health care systems and services. The selection includes two high-income countries (HICs) with a well-established health care system (Japan, with the highest average life expectancy and an ageing population, and Australia, with the majority of the population from European ancestral groups), one upper-middle-income country (UMIC) (China, the most populous country; rapidly ageing), and two LMICs (Viet Nam and Papua New Guinea). Alarmingly, Papua New Guinea, as a representative of the Pacific Islands, showed some reversal and a slightly increasing trend in age-standardised mortality. This unusual trend in this indicator suggested worsened NCD prevention and control in this country. The very high prevalence of obesity and diabetes and potentially prevalent unhealthy lifestyles, e.g., smoking in Pacific islands are potential risk factors.9,10 The interesting inverse association between the income groups and the width of the mortality confidence interval, particularly the large width in two LMICs, suggested the diverse degrees of data validity and reliability in NCD monitoring.

Mental health in the Western Pacific region

Mental health is an important health issue in the Western Pacific region and has been added as the fifth major NCD in the new 5 × 5 approach to NCDs in the 3rd High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of NCDs.3 Over 215 million people in this region suffer from mental health conditions.11 The result of the 2019 GBD study showed that various mental health conditions, such as anxiety and depressive disorders, self-harm, schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease, and other forms of dementia significantly increased in the Western Pacific region from 1990 to 2019.12 In addition, emerging evidence has suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic had a massive negative impact on mental health and exacerbated this increasingly high public health issue.13

The universal increased disease burden due to mental disorders in this region was consistent with the global trends, which had an increased proportion of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) from 3.1% in 1990 to 4.9% in 2019.14 The current status and trends in mental health were caused by the complex interactions of many multi-level factors. The increasing proportion of older people in this region as a result of a combination of longer life expectancies and decreasing fertility rates probably have led to the growing prevalence of dementia and other age-related mental health conditions.15 The rapid economic development, urbanisation, lifestyle transition, and related pressure in this region, may also lead to increased mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety.16 The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic were substantial. High rates of psychological distress and signs of an increase in mental health disorders were observed, both as a result of the pandemic itself and strategies to cope with it, such as mitigation/containment and lockdowns/quarantines.13 Many countries, including China, have used digital health care in their mental health responses.13,17 However, this strategy also intensified the disparities in access to quality mental health care, particularly among older adults.18

Of note, from the GBD data, some HICs, e.g., Japan, Australia, and the Republic of Korea in this region have a higher disease burden from mental health than the LMICs, which was in line with the global distribution by income group.14,19 One potential reason may be due to internet overuse, which may increase the risk of online or cyber-bullying through various vehicles such as laptops and smartphones.20 The serious problem of suicide and school refusal among Japanese teenagers, and the derived social withdrawal among adults is a typical example.21 On the other hand, the potential drivers of disease burden from mental health in LMICs are heterogeneous in comparison with HICs. For instance, the high prevalence of sexual and interpersonal violence in LMICs may result in short- and long-term mental effects.22,23 Though the recognition of mental health problems in LMICs is growing, the gap still exists in monitoring the issue and studying the strategies, policies, and programs to prevent mental disorders by income groups.24 Barriers to mental health services and related stigma may hinder medical care-seeking behaviours, thus facilitating underestimating and increasing the disease burden. Potential barriers of mental health services in LMICs include the competing public health priority, the challenges in implementing population-based strategies in primary care settings, and insufficient numbers and limited types of mental health professionals and qualified community workers.25 Stigma of mental disorders is common in almost every country, and impacts people living with this condition, their families and health professionals. Certain prerequisites are necessary for addressing and overcoming stigma adequately, including comprehensive and integrated mental health policies and legislation, sustainable and culturally adapted intervention programs, capacity building of mental health and other workforce professionals, and the integration of mental health services into primary care settings. However, these conditions are largely inadequate in LMICs.26 Cultural factors (e.g., collectivism, Confucianism, concern over saving face, religion, and supernatural beliefs) are potential socio-cultural determinants that facilitate the hesitation for mental health acknowledgement and medical care-seeking behaviours.27

Within countries, disadvantaged populations are commonly disproportionately affected by poor mental health conditions resulting from higher exposure to stress due to poverty, disparities in access to mental health services, and low health literacy.14,19 A substantial lack of resources for sufficient access to medical care may prevent disadvantaged people from care-seeking behaviours.24

Disparities in NCD mortality by selected macro-level factors in the Western Pacific region

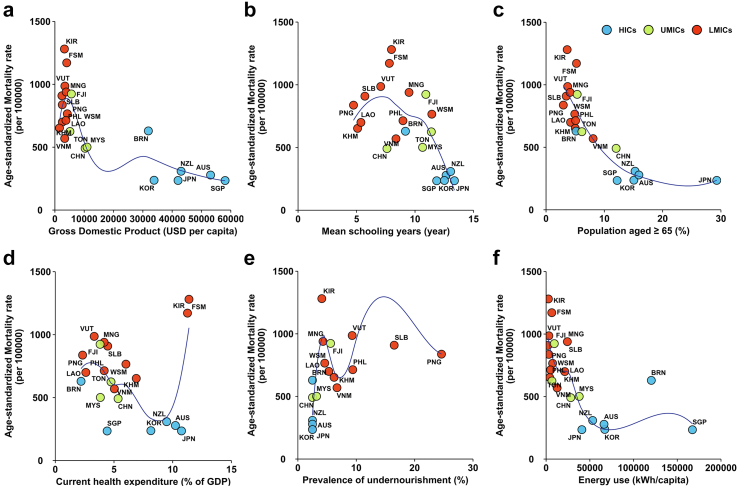

Large disparities existed in the distribution of both the NCD mortality and potential socioeconomic and other related risk factors (Fig. 2). The highest age-standardised mortality from NCDs was 1281.0 per 100 thousand population in Kiribati, which was 5.4 times higher than the lowest country (234.8 per 100 thousand population in Singapore). Socioeconomic (gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and education), demographic (percentage of aged population), health expenditure (current health expenditure as a percentage of GDP), and some other related factors listed in Fig. 2 using World Bank Open Data,28 all varied widely. Some risk factors are aggregated by different types of features such as income group, geographic, or cultural factors. Both the trends of the fitting curve and the aggregation pattern of the potential risk factors by income groups are of interest. HICs had more schooling years, a higher percentage of GDP as health expenditure, a higher percentage of the aged population, higher energy use per capita, and a lower prevalence of undernourishment compared with UMIC and LMICs. Consequently, HICs also had lower age-standardised NCD mortality.

Fig. 2.

Association between age-standardised mortality rates due to non-communicable diseases and potential risk factors in 21 countries and areas in the Western Pacific region in 2019. a. gross domestic product; b. Mean year of schooling; c. Percentage of the population aged ≥65; d. Current health expenditure; e. Prevalence of undernourishment; f. Energy use per capita. Data on age-standardised mortality rates were obtained from the World Health Organization Noncommunicable diseases: Mortality (https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/topic-details/GHO/ncd-mortality). Data on the risk factors were obtained from the World Bank Open Data (https://data.worldbank.org). Each point represents one country or area, and countries and areas are colored by region. USD: United States dollars; HICs: high-income countries; UMICs: upper-middle-income countries; LMICs: lower-middle-income countries.

An overall inverse association was observed between age-standardised mortality from NCDs and indicators or proxies of socioeconomic development, including GDP per capita, mean schooling years, and energy use per capita (Fig. 2A, C, and F). This is consistent with the conditions globally and in other regions,5 indicating such social determinants of health may have the strongest impacts on health outcomes. The Pacific islands had the highest age-standardised mortality from NCDs. Further, most Pacific islands were above the fitting curve in Fig. 2D, indicating lower health system efficiency, with higher health expenditure but only limited performance of NCD prevention and control in these countries and areas. The very high obesity rates in the Pacific islands, which is an important intermediate and monitoring indicator for NCD prevention and control, may be an important reason as discussed before.9,29,30 By contrast, some countries below the fitting curve in Fig. 2D had higher health system efficiency by using relatively limited health expenditure but achieved better performance, e.g., Singapore, the Republic of Korea, Japan, China, and Malaysia.

A broader overview of the global conditions shows the general gradient in health and socioeconomic status across and within countries: lower socioeconomic position, worse health.31 Despite overall limited studies, such evidence tended to accumulate in HICs, such as European countries,32 and was scarce in UMICs and LMICs. This was probably associated with the competing resources for research topics in UMICs and LMICs, where studies on health disparities were not prioritised. Some outlier examples with inferior economic development but outstanding performance in health outcomes provided some promising insights for overcoming the health divide related to the economic status through improving health system performance. Cuba had a life expectancy at birth of 78 years in 2020, which was comparable to many HICs.28 The divergence in health and economic indicators for Cuba was even more pronounced in the 1990s. Cuba's health system represents an example of a national integrated approach resulting in improved health for the mass population. The development of family medicine and tax-financed universal health systems in Cuba enabled equitable access to quality care.33,34 Such successful health system performance provided invaluable experiences for other countries, particularly for those with limited resources.

Minority population is also vulnerable and demonstrates different patterns in NCDs and their related risk factors by income groups. In Australia, the HIC, the prevalence of obesity and diabetes were higher in indigenous people than that in general population (obesity/overweight 74.9% vs. 64.3%; diabetes 12.6% vs. 4.3%).35 In China, the UMIC, a study in 2014–2015 included more than 726 thousand participants showed higher prevalence of overweight/obesity in Uyghur (65.5%), Manchu (38.0%), and Molgol people (34.3%) and lower obesity prevalence in Muslim (27.1%) than Han people (30.6%).36 Other national surveys in China suggested major minority population had lower prevalence of hypertension and diabetes but also lower awareness, treatment and control rates of both conditions compared to the Han population.37, 38, 39, 40

The generally low prevalence of some NCD metabolic risk factors, e.g., obesity and hypertension, contributed to the low mortality from NCDs in some countries. Japan and the Republic of Korea are the two countries with the lowest obesity rates in HICs worldwide (4.4% and 4.9%, respectively).41 The actions taken to reduce other risk factors, such as smoking cessation and the promotion of a healthy diet in some Eastern Asian countries, may also play important roles in reducing NCD burden.42,43 Thus, policy and interventions targeting the five major NCD risk factors (tobacco use, unhealthy use of alcohol, poor diet, inadequate physical activity, and environmental pollution) and controlling the metabolic risk factors (overweight and obesity, increased blood pressure, raised blood glucose, and dyslipidemia) should be prioritised. From the health economics perspective, promoting a healthy lifestyle is the most cost-effective investment in population-level health.44

Ageing is an important risk factor for NCDs. The seemingly contradictive inverse association between NCD age-standardised mortality and the percentage of the population aged ≥65 years (Fig. 2C) was explained by that countries in aged societies were more likely to be socioeconomically advanced, which is a strong predictor for low age-standardised mortality from NCDs.

Indicators for NCD management in the Western Pacific region and selected countries

The prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates of hypertension and diabetes are important indicators for NCD management and are included in the WHO NCD monitoring framework. The suboptimal conditions and disparities in NCD prevalence and management, indicated by the low rates of and large gaps in these rates of hypertension and diabetes, need to be addressed in the future, including national policies and programs.

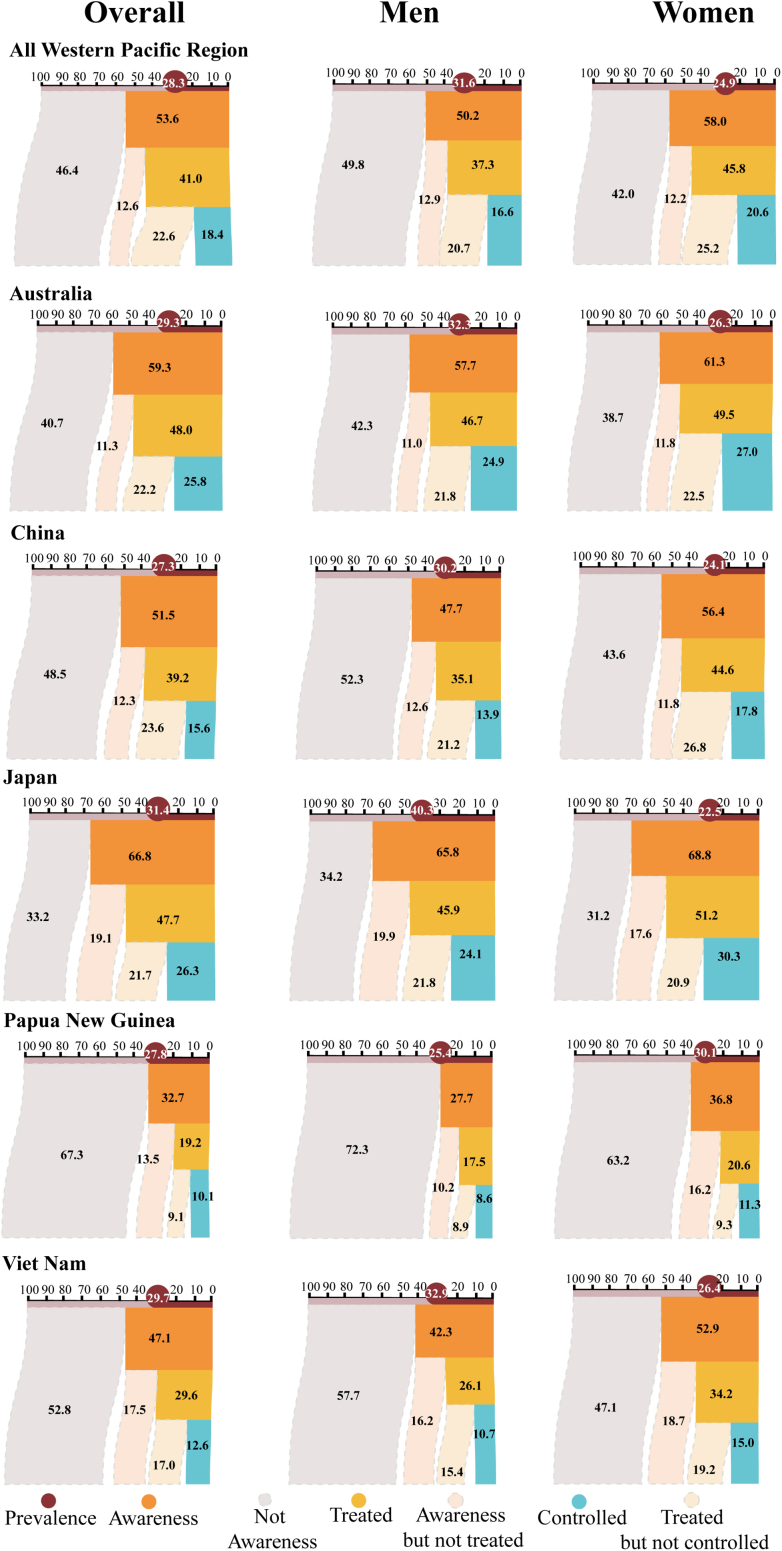

To address this concern, we systematically reviewed studies on the prevalence and management rates of hypertension and diabetes based on nationally representative surveys in the Western Pacific region and respective 37 countries and areas. The efforts identified limited studies on hypertension (Supplementary Table S2) and a few on diabetes. Thus, we presented the key results for the overall Western Pacific region and five selected countries (see Fig. 1). We selected data sources for comparability across countries from the WHO NCD database,6 detailed in Fig. 3 and Table 2.

Fig. 3.

Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates of hypertension in overall Western Pacific region and selected countries in the Western Pacific region. Data on the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates of hypertension were obtained from the World Health Organization Noncommunicable diseases: Risk factors (https://www.whoi.nt/data/gho/data/themes/topics/noncommunicable-diseases-risk-factors).

Table 2.

Disease burden and management (%) of diabetes in representative countries in the West Pacific region.c

| Countries | Year | Diagnostic criteria | Age (year) | Outcomes (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | Awareness | Treatment | Control | ||||

| Japan45 | 2021 | ADA 2018 | 20–79 | All 6.6 | All 54.5a | / | / |

| 2013–2017 | / | 40–74 | / | / | All 79.9 | All 55.3 | |

| Australia46,47 | 2021 | ADA 2018 | 20–79 | All 6.4 | All 75.0a | / | / |

| 2020–2021 | / | ≥15 | / | / | All 76.1 | / | |

| 2015 | / | ≥18 | / | / | / | All 28.0b | |

| Viet Nam | 2020 | ADA 2018 | 20–79 | All 6.1 | All 48.5a | / | / |

| China48 | 2021 | ADA 2018 | 20–79 | All 10.6 | All 48.3a | / | / |

| 2018 | ADA 2018 | ≥18 | / | / | All 32.9 | All 50.1 | |

| Papua New Guinea | 2021 | ADA 2018 | 20–79 | All 16.7 | All 48.5a | / | / |

| Western Pacific Region | 2021 | ADA 2018 | 20–79 | All 9.9 | All 47.2a | / | / |

Awareness rate was calculated by 1-proportion of patients with undiagnosed diabetes.

Control rate calculation included only type 2 diabetes.

Data from the International Diabetes Federation (for prevalence and awareness rates; https://diabetesatlas.org/data/en/indicators/2/), and multiple authoritative sources (for treatment and control rates).45, 46, 47, 48

In the Western Pacific region, the status and disparities in prevalence and management rates of hypertension and diabetes suggested a major challenge for NCD prevention and control. The prevalence of hypertension in the overall Western Pacific region and the five selected countries did not have large variability. All were high, ranging from 27.3% in China to 31.4% in Japan. However, the rates of awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension were generally low and varied largely across countries. Further, the data showed an inverse association between income and the management rates of hypertension. Among these five countries, the control rates were as low as around 10% in Papua New Guinea and Viet Nam, and only about 1/4 as that in Australia and Japan. Generally, men had a higher prevalence of hypertension than women, while women had higher awareness, treatment, and control rates than men (Fig. 3).

The limited studies available on diabetes revealed generally low levels of and large disparities in prevalence and management rates across countries. Papua New Guinea had the highest prevalence of diabetes of 16.7%, and Australia had the highest awareness rate of 75.0% (Table 2). No nationally representative or comparable data was found for the difference by sex.

Evidence on time trends in NCD management also showed continuously prevalent hypertension and diabetes, but stagnated rates and uncontrolled situations in both conditions in the past two decades in the Western Pacific region.49,50 With China as an example, the prevalence of hypertension increased from 18.8% in 2002 to 25.2% in 2012 and 27.5% in 2018, and the prevalence of diabetes increased from 2.6% in 2002 to 10.4% in 2012 and 11.9% in 2018. In this same period, the awareness, treatment, and control rates of both conditions had a modest improvement, but the rates remained low. Specifically, the control rate for hypertension in China was as low as less than 20%, and the rate for diabetes was about 1/3 in 2018.51 Of importance, rural residents were more adversely affected and had higher increase rates in prevalence of both conditions compared with urban residents,48,50,51 suggesting the prominent phenomenon of disparity in NCD management by socioeconomic status within countries. Similar intra-country disparities can also be observed in other countries by sex, income, education, occupation, ethnicity, religion, etc.52 The easily neglected social determinants of health need to be explored to address health inequities for vulnerable populations.53

Determinants of NCD burdens in the Western Pacific region

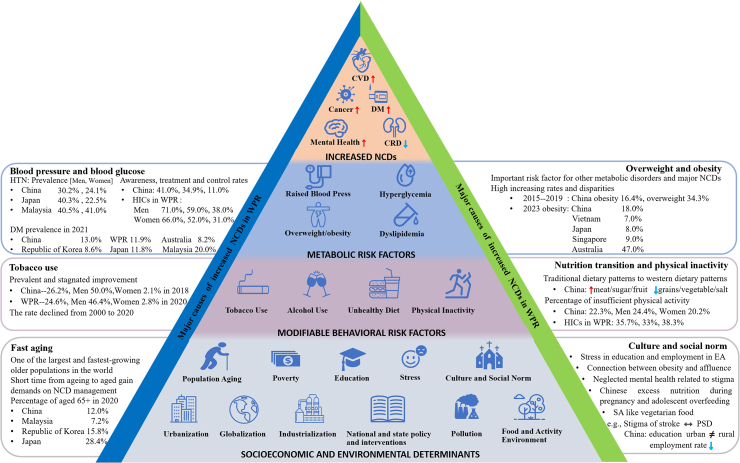

The rapid increase in the NCD disease burden in the Western Pacific region is a result of complex interactions of many determinants in multiple domains. Fig. 4 shows the framework of three domains of potential determinants of increased NCDs and some unique examples in the Western Pacific region. We developed this framework based on the Regional Action Framework for Noncommunicable Disease Prevention and Control in the Western Pacific and findings from other related studies.66, 67, 68 Three consecutive bottom-up layers of determinants are listed in a pyramid: socioeconomic and environmental determinants, modifiable behavioural risk factors, and metabolic risk factors.

Fig. 4.

Major causes and drivers of increased non-communicable diseases in the Western Pacific region.29,54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65 Describe the major causes and drivers that contribute to non-communicable diseases. CRD, Chronic Renal Disease; CVD, Cardiovascular Disease; DM, Diabetes Mellitus; HICs, high-income countries; HTN, hypertension; M, men; NCD, non-communicable diseases; PSD, post-stroke depression; W, women; WRP, Western Pacific region.

Mutual and reciprocal impacts between determinants and increased NCDs

The complex interaction and mutual-reinforcing effects of these determinants have an important collective impact on increased NCDs.66,67 Reciprocally, the increased NCD burden can exacerbate socioeconomic status by increased healthcare-related costs and decreased labor capability of patients with NCDs. In particular, disadvantaged populations with inadequate resilience and inferior capability of coping with such stress, will suffer more and may sink into a reciprocally vicious cycle unless necessary aid and other timely intervention programs are provided.69, 70, 71 A national survey of 29,712 poor households in rural China in 2017 showed that 51.6% of households attributed their poverty to diseases, among which most were NCDs.72 During the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with NCDs were particularly vulnerable to increased and excessive morbidity and mortality.73 Countries and areas with an inadequate capacity to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic suffered more, thus further increasing NCD-related poor health outcomes.

Socioeconomic and environmental determinants

Some unique socioeconomic and environmental factors in the macro-level determinants of NCDs existed in the Western Pacific region. Fast ageing is one of the most prominent ones. Unlike most European countries, which took more than 60 years to finish the transition from ageing to an aged society, the time for most Asian countries in the Western Pacific region is predicted to be about only 15–25 years, regardless of the income group. Examples include both HICs and LMICs such as Japan (24 years), the Republic of Korea (18 years), and Singapore (17 years), China (23 years), Viet Nam (18 years), Malaysia (24 years), and Mongolia (25 years).74 In the Western Pacific region, China has the largest number of older adults aged 65 and older globally, totaling 200.6 million and accounting for 14.2% of the total population in 202175; Japan has the largest percentage of the aged population of 29.3% in 2021 (Monaco excluded) and this proportion will continue to increase.28

In addition, some cultural and social norms in this region also contributed to the increased NCD burden but these factors have been understudied. Specifically, the common traditional perception of the close connection between obesity and affluence in some Asian countries, which has been examined in South Asian countries, such as India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh,76 were rarely studied in the Western Pacific region. The topic of stigma and mental health has only very limited epidemiological data with large uncertainty intervals, without further exploration for potential key effective interventions.27 The culture-related perfectionism mindset and the consequent intensive competition-related stress in education and job markets in East Asian countries, e.g., China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea, are perhaps interesting cultural determinants and were considered important drivers for the decreased fertility rates in these countries,77 but are largely understudied. The tendency of study aggregation on the biological pathway rather than the macro-level determinants of NCDs, which may have important impacts on policy and intervention programs, highlights the research gap in NCDs in this region.

Furthermore, the increased NCD burden may also be attributed to environmental determinants such as air pollution and climate change.78 To be specific, the adverse effect of air pollution exposure on NCDs was mainly reported among individuals in East Asian countries, such as China, Korea, and Japan.79 Pacific islands are areas that suffered most from the elevated sea level resulted from climate change. Some islanders are forced to migrate from their homeland to other places. Related anxiety and other mental disorders should be investigated further.

The socioeconomic and environmental determinants had universal impacts on the overall population, but some detrimental influences affected the disadvantaged more adversely. Some contextual risk factors, such as the unhealthy food and activity environment and the negative impacts of the global food industry affected the poor and disadvantaged most.69,71 The Western Pacific region presents significant disparities in levels of socioeconomic status across and within countries. The GDP per capita ranged from 72794.0 USD in Singapore to 1606.5 USD in Kiribati in the year 2021. The Gini Index, an indicator for measuring the equity of income distribution in a country, reached 42.3 in the Philippines in 2018, higher than the value of 41.4 in the United States in the same year.28,53,80 Such social determinants of health should be addressed and more efforts should be taken to tackle these potential health equity issues in this critical time window of a transitional period in many countries and areas in this region.

Behavioral and metabolic risk factors

The prevalence of behavioral and metabolic risk factors is an important pointer to the NCD burden. Among the modifiable behavioral risk factors, the nutrition transition from traditional to western diets, driven by the food system transformation after urbanisation and globalisation, is happening in many countries in the Western Pacific region in the past decades, regardless of income groups, such as in the Republic of Korea, China, and Pacific islands.54,81,82 Historically, most countries in the region have suffered from wars, conflicts, and unrest over the past decades: the Second World War, Viet Nam War, and Korean War. From the life course nutrition perspective, food insecurity and famine related to these situations may have bred an increased risk of obesity and related metabolic disorders and NCDs in this region, particularly in the context of nutrition transition.83 These unique historical contexts were suggested to have contributed to the fast-increasing prevalence of elevated blood glucose (diabetes prevalence 1–2% in the early 1980s to around 12.5% in 2021 in adults) and the current uniformly high prevalence of raised blood pressure (all over 25% and country-specific prevalence from 25% to 50%) and dyslipidaemia (all over 25%) in this region.84,85

Commercial determinants are potential underlying causes for the behavioural risk factors including the nutrition transition and other factors. Resulted from colonialism and commercial fishing, the Pacific islands had limited local access to fishing and replaced local food stuffs with processed food and animal products.86 The global and local corporations’ commercial promotion for tobacco, alcohol, sugar-sweetened beverages, and fast food, together with the reluctant willingness of governments to intervene in these areas through extensive public health campaigns or legally, e.g., by financial or tax measures, have also contributed to the prevalent behavioral risk factors.87 Such examples include the prevalent and stagnated smoking rates in China and Viet Nam, particular in men (50.0% in Chinese men in 2018, and 48.0% in Vietnamese men in 2015)51,88 and the increasing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages in many LMICs and the over-recommended-daily-limit consumption for free sugar in many HICs.89

Disparities in behavioural and metabolic risk factors also existed in the Western Pacific region. Men tended to have more adverse behavioural factors (e.g., tobacco use and alcohol consumption) and metabolic risk factors (e.g., raised blood glucose and increased blood pressure). Low socioeconomic groups usually had a significantly higher prevalence of unhealthy behaviours, e.g., unhealthy diet, tobacco use, than high socioeconomic groups in both HICs and LMICs.90 Behavioural modification is also very challenging for the vulnerable mostly due to social determinants of health, such as difficulties in physical and economic access to healthy food and to safe spaces for exercise, such as the case in Papua New Guinea.91 Metabolic risk factors were also more prevalent among urban residents in LMICs and transitional countries, but the differences by residence were closing.55,80,85 Data in China showed that the prevalence rates of current smokers (50.0% vs. 2.1%), excessive drinking (17.6% vs. 3.7%), hypertension (30.8% vs. 24.2%), and diabetes (12.9% vs. 10.9%) in men were all higher than in women; further, the rates for obesity (17.5% vs. 15.3%), diabetes (12.6% vs. 11.1%) and dyslipidaemia (36.5% vs. 34.6%) were all higher in urban than in rural residents, but the rates for hypertension were reversed (25.7% vs. 29.4%) in 2018.51 Interestingly, the top five countries with the highest prevalence of obesity and those with the highest prevalence of diabetes were all Pacific islands.9,85 The geographic aggregation of metabolic risk factors is interesting and the underline reasons and tailored interventions need to be explored further.

Highlights of intervention efforts in China

The Western Pacific and European regions are the only two WHO regions predicted to achieve SDG 3.4 targets on NCDs by 2030.92 With the largest population and the second largest economy globally, China has made good progress overall NCD prevention and control and heavily influenced the overall progress in premature mortality due to NCDs in this region. Some successful practices in China can provide useful insights for other countries.

During recent years, the Chinese government has promoted comprehensive population-based strategies to improve public health, launched several landmark national programs and enacted several laws. In 2016, China announced the “Healthy China 2030” national initiative; in 2019, it launched the “Healthy China Action Plan (2019–2030)”.93 Campaigns to promote health, such as National Nutritional Week held annually since 201594 and China’s ‘Healthy Lifestyles for All’ held since 2007,95 have made some major contributions to health lifestyle.

Obesity is a good indicator and intervention target of lifestyle risk factors of many NCDs. In October 2020, China released the “Action Plan to Prevent and Control Obesity among Children and Adolescents”. Our team published the comprehensive “Blue Paper on Obesity Prevention and Control in China” in 2019 and in a 2021 paper we outlined policy recommendations for China to fight the growing obesity epidemic.12,96 We have carried out a series of academic and community-based intervention efforts to fight against obesity as part of the March 4th World Obesity Day global efforts since 2022.

Moreover, community-based hypertension and diabetes management programs in China helped in improving NCD management. Healthcare system reforms, including universal healthcare coverage, enhanced financial security, and optimised health care resource allocation, have also improved the efficiency and productivity of the health care system, thus helping to improve NCD prevention and control.97

On the other hand, the stagnated improvement or even worsened conditions in some behavioural risk factors for NCDs and the deterioration in metabolic risk factors in China also called on for more efforts. In China, 50% of men smoke and almost 20% of men had excessive alcohol drinking, with smoking declining very slowly and alcohol consumption slowly increasing in the past two decades. The prevalence of overweight and obesity has been rising, and hypertension and diabetes largely were uncontrolled.51 To promote healthy lifestyles and appropriate management of NCDs are urgently needed in China, as well as in many other countries and areas in the Western Pacific region.

Recommendations to cope with NCDs in the Western Pacific region

We recommend several strategies to cope with the increasing NCD burden and related disparities in this region. First, “active health” and health-centred concepts should be promoted for long-term health. This includes more vigorous effects on promoting health lifestyle, and better programs on screening and self-management among high-risk populations and NCD patients. Second, countries should implement programs on prevention, early detection, management, and reducing social stigma about mental health. These include to enhance mental health services (its accessibility and quality), professional training and quality health facilities. Third, some cultural and social norms deserve increased attention. We need comprehensive research to understand health perceptions. Perfectionism-related stress should be explored and mitigated through wellbeing initiatives. A holistic research approach to NCDs considering macro-level determinants is critical. Policies addressing harmful norms and promoting health equity should be implemented. Interdisciplinary collaboration, community engagement, and local health system capacity strengthening are key to a holistic, culturally sensitive, and evidence-based approach to NCDs. Finally, more sustainable and effective efforts are needed to support vulnerable populations, such as those living in LMICs and those with low socioeconomic status, to decrease health disparities.

All above strategies require collaborative efforts from governments, healthcare providers, communities, and individuals and should be customised according to the specific circumstances of each country.

Conclusions

The NCD burden increase over the past decades and disparity in NCDs is common across and within countries in the Western Pacific region. Behavioural risk factors stagnated, metabolic risk factors continuously increased, and macro-level determinants were understudied. The prevalence of major NCDs is high while the rates of awareness, treatment and control are low in some countries in the region where data are available. Varying and sustainable coping strategies depending on changes in NCD patterns, and risk factors are needed for countries to combat NCDs in this region.

Contributors

YW, WP, and LZ initiated the concepts; LZ, FW, and XT reviewed the data and drafted figures and tables; YW, WP, LZ, FW, and XT conducted literature review; and YW, WP, and LZ drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically, and approved the submission of the manuscript in its current form.

Editor note

The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Declaration of interests

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Maureen Malowany for her contribution in editing and improving this manuscript, thank Prof Zumin Shi and Ms. Yanxiang Wang, Meng Lv, Aibin Qu, Yuan Sun and Han Qi for their contribution in preparing and improving this manuscript, and thank Profs Dongfeng Gu, Yaogang Wang, Liang Sun, Fengchao Liang, Xueli Yang, Xiaomin Sun and Ruiyue Yang for their assistance to improve the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported in part by Key R&D and Transformation Program of Qinghai (2023-QY-204); National Natural Science Foundation of China (82103846); National Key Research and Development Program of China, Grant/Award Number: 2017YFC0907200, 2017YFC0907201, 2016YFC0900603.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100938.

Appendix ASupplementary data

References

- 1.United Nations Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf

- 2.World Health Organization Global action plan for the prevention and control of NCDs 2013–2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.United Nations Political declaration of the 3rd high-level meeting of the general assembly on the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases : resolution/adopted by the general assembly. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1648984?ln=en

- 4.World Bank Life expectancy. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search/dataset/0037712/World-Development-Indicators

- 5.NCD Countdown 2030 collaborators NCD Countdown 2030: worldwide trends in non-communicable disease mortality and progress towards Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1072–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31992-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Noncommunicable diseases. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/noncommunicable-diseases

- 7.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation GBD results. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/

- 8.Kevin McCracken D.R.P. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2017. Demographic and epidemiological transition. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Obesity Federation Global Obesity Observatory Ranking (% obesity by country) https://data.worldobesity.org/rankings/?age=a&sex=f

- 10.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2627–2642. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization Mental health. https://www.who.int/westernpacific/health-topics/mental-health

- 12.Wang Y., Zhao L., Gao L., Pan A., Xue H. Health policy and public health implications of obesity in China. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(7):446–461. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kola L., Kohrt B.A., Hanlon C., et al. COVID-19 mental health impact and responses in low-income and middle-income countries: reimagining global mental health. Lancet Psychiatr. 2021;8(6):535–550. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00025-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatr. 2022;9(2):137–150. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasai D.T. Preparing for population ageing in the Western Pacific region. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2021;6 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gruebner O., Rapp M.A., Adli M., Kluge U., Galea S., Heinz A. Cities and mental health. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(8):121–127. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu S., Yang L., Zhang C., et al. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7(4):e17–e18. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Y., Li W., Zhang Q., Zhang L., Cheung T., Xiang Y.T. Mental health services for older adults in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatr. 2020;7(4):e19. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30079-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization Regional framework for the future of mental health in the Western Pacific 2023–2030. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/wpro---documents/regional-committee/session-73/wpr-rc73-agenda-11-annex-mental-health.pdf?sfvrsn=7cb83322_1

- 20.Yen C.F., Yen J.Y., Ko C.H. Internet addiction: ongoing research in Asia. World Psychiatr. 2010;9(2):97. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2010.tb00285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tateno M., Inagaki T., Saito T., Guerrero A.P.S., Skokauskas N. Current challenges and future opportunities for child and adolescent psychiatry in Japan. Psychiatry Investig. 2017;14(5):525–531. doi: 10.4306/pi.2017.14.5.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coll C.V.N., Ewerling F., García-Moreno C., Hellwig F., Barros A.J.D. Intimate partner violence in 46 low-income and middle-income countries: an appraisal of the most vulnerable groups of women using national health surveys. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(1) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization Global and regional estimates of violence against women. 2013. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564625

- 24.Henderson C., Noblett J., Parke H., et al. Mental health-related stigma in health care and mental health-care settings. Lancet Psychiatr. 2014;1(6):467–482. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saraceno B., van Ommeren M., Batniji R., et al. Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370(9593):1164–1174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61263-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Javed A., Lee C., Zakaria H., et al. Reducing the stigma of mental health disorders with a focus on low- and middle-income countries. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;58 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ran M.S., Hall B.J., Su T.T., et al. Stigma of mental illness and cultural factors in Pacific Rim region: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatr. 2021;21(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02991-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Bank World Bank open data. https://data.worldbank.org/

- 29.Guthold R., Stevens G.A., Riley L.M., Bull F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(10):e1077–e1086. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dearie C., Linhart C., Rafai E., Nand D., Morrell S., Taylor R. Trends in mortality and life expectancy in Fiji over 20 years. BMC Publ Health. 2021;21(1):1185. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11186-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marmot M. Epidemiology of socioeconomic status and health: are determinants within countries the same as between countries? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:16–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marmot M., Allen J., Bell R., Bloomer E., Goldblatt P. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet. 2012;380(9846):1011–1029. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keck C.W., Reed G.A. The curious case of Cuba. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(8):e13–e22. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atun R., de Andrade L.O., Almeida G., et al. Health-system reform and universal health coverage in Latin America. Lancet. 2015;385(9974):1230–1247. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61646-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Australian Bureau of Statistics ABS 2018-19 national aboriginal and torres strait islander health survey (NATSIHS) 2019. https://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/719848

- 36.Tong X., Wang X., Wang D., et al. Prevalence and ethnic pattern of overweight and obesity among middle-aged and elderly adults in China. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26(16):1785–1789. doi: 10.1177/2047487319845129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases Annual report on cardiovascular health and diseases in China (2019) 2019. https://www.nccd.org.cn/News/Columns/Index/1089

- 38.Lu J., Lu Y., Wang X., et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: data from 1·7 million adults in a population-based screening study (China PEACE Million Persons Project) Lancet. 2017;390(10112):2549–2558. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32478-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang L., Gao P., Zhang M., et al. Prevalence and ethnic pattern of diabetes and prediabetes in China in 2013. JAMA. 2017;317(24):2515–2523. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li Y., Teng D., Shi X., et al. Prevalence of diabetes recorded in mainland China using 2018 diagnostic criteria from the American Diabetes Association: national cross sectional study. BMJ. 2020;369:m997. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Bank Obesity. https://ourworldindata.org/obesity

- 42.Jiang Y., Guo H., Zhang W., et al. Gaps and directions in addressing non-communicable and chronic diseases in China: a policy analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(15) doi: 10.3390/ijerph19159761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katoh K. Health advocacy for reducing smoking rates in Hamamatsu, Japan. Hypertens Res. 2020;43(7):634–647. doi: 10.1038/s41440-020-0418-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization Saving lives, spending less: a strategic response to noncommunicable diseases. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-NVI-18.8

- 45.Ikeda N., Nishi N., Sugiyama T., Noda H., Noda M. Effective coverage of medical treatment for hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidaemia in Japan: an analysis of National Health and Nutrition Surveys 2003-2017. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2021;26(2):106–114. doi: 10.1177/1355819620949574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Australian Bureau of Statistics Diabetes, 2020-21 financial year. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/diabetes/latest-release

- 47.Nanayakkara N., Ranasinha S., Gadowski A.M., et al. Age-related differences in glycaemic control, cardiovascular disease risk factors and treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study from the Australian National Diabetes Audit. BMJ Open. 2018;8(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang L., Peng W., Zhao Z., et al. Prevalence and treatment of diabetes in China, 2013-2018. JAMA. 2021;326(24):2498–2506. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.22208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.World Health Organization Regional action framework for noncommunicable disease prevention and control in the Western Pacific. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/wpro---documents/regional-committee/session-73/wpr-rc73-agenda-12-annex-ncd-prevention-and-control.pdf/

- 50.Zhang M., Shi Y., Zhou B., et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China, 2004-18: findings from six rounds of a national survey. BMJ. 2023;380 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-071952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peng W., Chen S., Chen X., et al. Trends in major non-communicable diseases and related risk factors in China 2002–2019: an analysis of nationally representative survey data. Lancet Reg Health Western Pac. 2023;43:100809. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olsen M.H., Angell S.Y., Asma S., et al. A call to action and a lifecourse strategy to address the global burden of raised blood pressure on current and future generations: the Lancet Commission on hypertension. Lancet. 2016;388(10060):2665–2712. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang J., Wang Z., Du W., et al. Twenty-five-year trends in dietary patterns among Chinese adults from 1991 to 2015. Nutrients. 2021;13(4) doi: 10.3390/nu13041327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021;398(10304):957–980. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01330-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang M., Wu J., Zhang X., et al. Prevalence and control of hypertension in Chinese adult residents in 2018. Chin J Epidemiol. 2021;42(10):1780–1789. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20210508-00379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.International Diabetes Federation . 10th ed. 2021. IDF diabetes atlas. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pan X.F., Wang L., Pan A. Epidemiology and determinants of obesity in China. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(6):373–392. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.World Obesity Federation World obesity atlas 2023. https://data.worldobesity.org/publications/?cat=19

- 60.Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention Center for Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases . People's Medical Publishing House; 2018. China chronic diseases and risk factors monitoring report. [Google Scholar]

- 61.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2023. World health statistics 2023: monitoring health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. [Google Scholar]

- 62.United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population Division . 2019. World population Prospects 2019, volume II: demographic Profiles (ST/ESA/SER.A/427) [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhu M., Zhou H., Zhang W., et al. Stigma experienced by Chinese patients with stroke during inpatient rehabilitation and its correlated factors: a cross-sectional study. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2019;26(5):342–348. doi: 10.1080/10749357.2019.1605759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deng C., Lu Q., Yang L., et al. Factors associated with stigma in community-dwelling stroke survivors in China: a cross-sectional study. J Neurol Sci. 2019;407 doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2019.116459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li C. Social Sciences Literature Press; 2022. Education and employment of Chinese youth. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pearce N., Ebrahim S., McKee M., et al. The road to 25×25: how can the five-target strategy reach its goal? Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(3):e126–e128. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dans A., Ng N., Varghese C., Tai E.S., Firestone R., Bonita R. The rise of chronic non-communicable diseases in southeast Asia: time for action. Lancet. 2011;377(9766):680–689. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.World Health Organization Global comprehensive surveillance framework (with indicators) and voluntary targets for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases (2013-2025) https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB132/B132_6-en.pdf

- 69.Mendenhall E., Kohrt B.A., Norris S.A., Ndetei D., Prabhakaran D. Non-communicable disease syndemics: poverty, depression, and diabetes among low-income populations. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):951–963. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30402-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jaspers L., Colpani V., Chaker L., et al. The global impact of non-communicable diseases on households and impoverishment: a systematic review. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015;30(3):163–188. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9983-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Manderson L., Jewett S. Risk, lifestyle and non-communicable diseases of poverty. Global Health. 2023;19(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12992-023-00914-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhou Y., Guo Y., Liu Y. Health, income and poverty: evidence from China's rural household survey. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-1121-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kluge H.H.P., Wickramasinghe K., Rippin H.L., et al. Prevention and control of non-communicable diseases in the COVID-19 response. Lancet. 2020;395(10238):1678–1680. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31067-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.World Health Organization Report of the regional director : the work of WHO in the Western Pacific region, 1 July 2021 - 30 June 2022. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789290619963

- 75.The State Council of the People's Republic of China National bulletin on the development of the cause of aging in 2021. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2022-10/26/content_5721786.htm

- 76.Mistry S.K., Puthussery S. Risk factors of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence in South Asian countries: a systematic review of the evidence. Public Health. 2015;129(3):200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anderson T., Kohler H.P. Education fever and the East Asian fertility puzzle: a case study of low fertility in South Korea. Asian Popul Stud. 2013;9(2):196–215. doi: 10.1080/17441730.2013.797293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fuller R., Rahona E., Fisher S., et al. Pollution and non-communicable disease: time to end the neglect. Lancet Planet Health. 2018;2(3):e96–e98. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu K., Ho H.C., Su H., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of intraday effects of ambient air pollution and temperature on cardiorespiratory morbidities: first few hours of exposure matters to life. EBioMedicine. 2022;86 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.World Health Organization Health equity and its determinants in the Western Pacific region. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/333944

- 81.Kim S., Moon S., Popkin B.M. The nutrition transition in South Korea. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(1):44–53. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thow A.M., Heywood P., Schultz J., Quested C., Jan S., Colagiuri S. Trade and the nutrition transition: strengthening policy for health in the Pacific. Ecol Food Nutr. 2011;50(1):18–42. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2010.524104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Uauy R., Kain J., Corvalan C. How can the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis contribute to improving health in developing countries? Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(6 Suppl):1759s–1764s. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.World Health Organization Noncommunicable diseases in the Western Pacific region: a profile. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/207510/9789290615637_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- 85.International Diabetes Federation Diabetes in Western Pacific – 2021. https://diabetesatlas.org/idfawp/resource-files/2021/11/IDF-Atlas-Factsheet-2021_WP.pdf [PubMed]

- 86.Thow A.M. Trade liberalisation and the nutrition transition: mapping the pathways for public health nutritionists. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(11):2150–2158. doi: 10.1017/S1368980009005680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Moodie R., Stuckler D., Monteiro C., et al. Profits and pandemics: prevention of harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink industries. Lancet. 2013;381(9867):670–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Samira A. The GATS atlas: global adult tobacco survey. 2015. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/51993

- 89.Malik V.S., Hu F.B. The role of sugar-sweetened beverages in the global epidemics of obesity and chronic diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18(4):205–218. doi: 10.1038/s41574-021-00627-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Allen L., Williams J., Townsend N., et al. Socioeconomic status and non-communicable disease behavioural risk factors in low-income and lower-middle-income countries: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(3):e277–e289. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30058-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Koczberski G., Curry G.N., Bue V., Germis E., Nake S., Tilden G.M. Diffusing risk and building resilience through innovation: reciprocal exchange relationships, livelihood vulnerability and food security amongst smallholder farmers in Papua New Guinea. Hum Ecol. 2018;46(6):801–814. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Martinez R., Lloyd-Sherlock P., Soliz P., et al. Trends in premature avertable mortality from non-communicable diseases for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a population-based study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(4):e511–e523. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.The State Council of the People's Republic of China Healthy China action plan (2019–2030) http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-07/15/content_5409694.htm

- 94.Chinese Nutrition Society Nutrition week. https://www.cnsoc.org/background/

- 95.China healthy lifestyle for all. https://www.chinacdc.cn/jiankang121/mryw/

- 96.Wang Y., Sun M., Yang Y. Peking University Medical Press; Beijing: 2019. Blue paper on obesity prevention and control in China. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chai P., Wan Q., Kinfu Y. Efficiency and productivity of health systems in prevention and control of non-communicable diseases in China, 2008-2015. Eur J Health Econ. 2021;22(2):267–279. doi: 10.1007/s10198-020-01251-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.