Abstract

Objectives:

Exposure therapy is a cornerstone of social anxiety treatment, yet not all patients respond. Symptoms in certain social situations, including intergroup (i.e., out-group) contexts may be particularly resistant to treatment. Exposure therapy outcomes may be improved by stimulating neural areas associated with safety learning, such as the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). The mPFC also plays an important role in identifying others as similar to oneself. We hypothesized that targeting the mPFC during exposure therapy would reduce intergroup anxiety and social anxiety.

Methods:

Participants () with the public speaking subtype of social anxiety received active (anodal) or sham tDCS targeting the mPFC during exposure therapy. Exposure therapy consisted of giving speeches to audiences in virtual reality. To target intergroup anxiety, half of the public speaking exposure trials were conducted with out-group audiences, defined in this study as audiences of a different ethnicity.

Results:

Contrary to hypotheses, tDCS did not facilitate symptom reduction. Some evidence even suggested that tDCS temporarily increased in-group favoritism, although these effects dissipated at one-month follow-up. Additionally, collapsing across all participants, we found reductions across time for public speaking anxiety and intergroup anxiety.

Conclusions:

The data provide evidence that standard exposure therapy techniques for social anxiety can be adapted to target intergroup anxiety. TDCS targeting the mPFC may boost safety signaling, but only in contexts previously conditioned to signal safety, such as an in-group context.

Keywords: noninvasive neurostimulation, virtual reality exposure therapy, social anxiety, intergroup anxiety

Introduction

Social anxiety is highly prevalent1 and impairing,2 and treatments leave room for improvement. Exposure therapy is an important component of gold standard treatments.3 However, only about half of individuals with social anxiety respond to treatment.4 This might be explained, in part, by certain types of social anxiety being more resistant to extinction due to biological preparedness.

Biological preparedness refers to the notion that humans are predisposed to develop fears toward specific stimuli.5 In addition to being developed more readily, these biologically prepared fears are more resistant to extinction.6,7 Fear responses toward ethno-racial out-groups (i.e., people belonging to an ethnicity or race that is different from one’s own) might be biologically prepared and more resistant to extinction.8,9 However, this phenomenon has not been evaluated among individuals with social anxiety, who have pre-existing social fears as opposed to laboratory-conditioned social fears.

Individuals with social anxiety may be more anxious in out-group social contexts compared to in-group socials contexts. If fear toward out-group members is more difficult to extinguish, then intergroup anxiety (i.e., anxiety related to interacting with members of a different sociocultural group) may be an important target for social anxiety treatment. Intergroup anxiety is an emerging area of research, and there are no well-established treatments for it. Theoretically, standard clinical treatments such as exposure therapy could help,10 but empirical research is needed to directly test whether exposure therapy can effectively target intergroup anxiety.

Given the challenges in treating social and intergroup anxiety, it is important to consider strategies to boost fear extinction mechanisms during treatment. The neural mechanisms of fear extinction involve the central roles of (1) the amygdala in governing fear responding and (2) the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) in inhibiting amygdala-driven fear responses and promoting fear extinction learning. Compared to healthy controls, people with social anxiety show hyperactivity in the amygdala in response to negatively valanced stimuli.11 The role of the mPFC in extinction learning is well-supported by animal models. For example, lesions to the mPFC disrupt fear extinction.12–14 Furthermore, the mPFC signals safety by dampening amygdala activity.15 For example, imaging studies show that emotional regulation in the presence of a fear-provoking stimulus corresponds with increased mPFC activity and decreased amygdala activity.16 Overall, the mPFC plays a critical role in fear extinction.

Because mPFC activation promotes fear extinction, several studies have boosted mPFC activation with neurostimulation to enhance fear extinction. Two reviews suggest stimulating the mPFC could enhance the effects of exposure therapy.17,18 Moreover, noninvasive neurostimulation as a treatment augmentation strategy has demonstrated promising results in treatment-resistant contexts, such as treatment-resistant depression19 and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).20 However, it has not been tested as a means of enhancing exposure therapy to treat extinction-resistant fears, such as biologically prepared fears, including fear in an intergroup (i.e., out-group) context.

Noninvasive neurostimulation targeting the mPFC may be especially valuable for augmenting exposure therapy for intergroup anxiety. Firstly, mPFC stimulation might enhance exposure therapy to treat extinction-resistant biologically prepared fears, like fear towards out-groups. Moreover, the role of the mPFC in social cognitive processes makes it a particularly applicable target for intergroup anxiety treatment. Prior studies found that mPFC activation is associated with self-referential (i.e., “same-or-similar-to-me”) processing.21 Therefore, if stimulated in an out-group context, mPFC activity may facilitate re-categorization to alter one’s perception of out-group members to align with one’s in-group. Overall, these data suggest that targeting the mPFC with neurostimulation during exposure therapy is a promising strategy for promoting fear extinction and could be particularly beneficial in treating intergroup anxiety.

The current study examined whether stimulating the mPFC via transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) improves exposure therapy outcomes for social anxiety in ethnicity-related in-group and out-group contexts. We used tDCS because it is inexpensive, and has minimal side effects22 compared to other stimulation methods.23 We focused on public speaking anxiety because it is a commonly feared social situation among individuals experiencing social anxiety.24 We used a virtual reality (VR) exposure therapy protocol, given the growing empirical support for VR exposure therapy, and to allow for rapid alternations between in-group and out-group public speaking contexts. Lastly, we decided to focus on an intergroup context defined by Latinx (vs non-Latinx) ethnic identity because the Latinx population is the largest local minority group.25

We addressed three research questions with corresponding hypotheses. (1) Do people with public speaking anxiety experience greater anxiety in an out-group vs in-group context? We hypothesized that participants would report greater anxiety when delivering speeches to out-group audiences. (2) Can standard exposure therapy protocols for public speaking anxiety reduce anxiety in an out-group context (i.e., intergroup anxiety)? We hypothesized that, after completing VR exposure therapy in both in-group and out-group contexts, participants would experience reductions in intergroup anxiety. (3) Does stimulation targeting the mPFC facilitate safety signaling during exposure therapy for public speaking anxiety in general, and especially for public speaking anxiety in an out-group context? We hypothesized that participants who received an active dose of tDCS would experience greater reductions in public speaking anxiety compared to participants who received a placebo dose (i.e., sham tDCS). We also hypothesized that the benefits of active tDCS would be more pronounced in the out-group public speaking context.

Methods

Participants

We recruited 33 undergraduates (mean (standard deviation), 19.65 (1.50) years old) from northern Nevada colleges between April 2019 and April 2020. Two participants discontinued participation before completion due to discomfort during stimulation; their data were removed, resulting in a sample of (94% of the originally recruited sample). Participants were mostly female-identified (81%) and white (66%), with the remainder identifying as male (19%) and Latinx (Hispanic/Latino; 34%; see Table 1 for demographics).

Table 1.

Demographics for Overall Sample and by Experimental Group

| Characteristic | Total () | Active tDCS () | Sham tDCS () |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ethnicity/race classification | |||

| White | 20 (65) | 10 (63) | 10 (67) |

| Latinx | 11 (35) | 6 (38) | 5 (33) |

| Ethnic identity | |||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 20 (65) | 10 (63) | 10 (67) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 11 (35) | 6 (38) | 5 (33) |

| Racial identity | |||

| White/Caucasian | 26 (84) | 13 (81) | 13 (87) |

| More than one race | 5 (16) | 3 (19) | 2 (13) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 25 (81) | 14 (88) | 11 (73) |

| Male | 6 (19) | 2 (13) | 4 (27) |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Age | 19.65 (1.50) | 19.75 (1.45) | 20.00 (1.51) |

Note. All participants who self-identified as non-Hispanic/Latino also self-identified as white/Caucasian.

Participants were prescreened for eligibility via an online survey. Participants were excluded if they were (1) under the age of 18, (2) did not identify as white or Latinx, (3) did not have high enough public speaking anxiety, or (4) had pre-existing conditions which would make them more likely to experience side effects from brain stimulation. (See Eligibility prescreen under Measures for further detail.) Eligible participants were randomly assigned to receive active tDCS () or sham tDCS (; see Table 1 for demographic information by tDCS group). Participants were randomized to tDCS groups in a 1:1 ratio using block randomization (blocks of two) and stratification based on ethnicity.

Full participation required participants to attend two in-person laboratory visits. All 31 participants who received the allocated treatment were included in analyses when data were available (e.g., treatment process analyses) even if they did not attend the second visit.

Informed consent for the online prescreen was obtained electronically, and informed consent for the in-person study procedures was obtained during the first lab visit. Participants were compensated with either class credit or a $25 Amazon gift card for each study visit ($50 possible in total). All procedures were approved by the university Institutional Review Board.

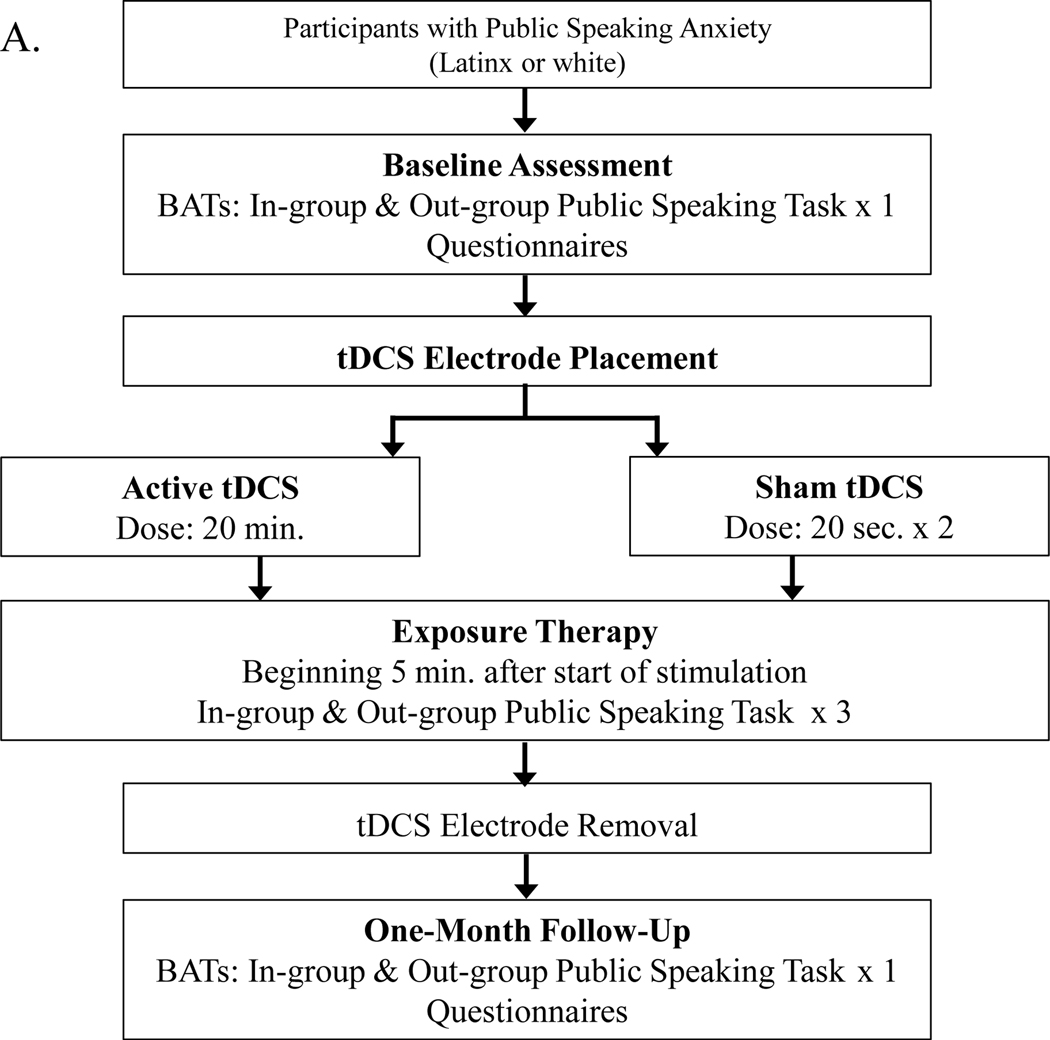

Procedure

After the online prescreen, eligible participants were scheduled to attend an initial laboratory visit, during which they completed informed consent, baseline behavioral tests (including subjective ratings), baseline questionnaires, and exposure therapy (also including subjective ratings). One month later, participants returned for a follow-up visit, and behavioral tests and questionnaires were repeated. We did not assess treatment outcomes immediately after exposure therapy because the aftereffects of tDCS can last an hour or more,26,27 and tDCS can produce more pronounced differential effects after a delay of several weeks.28 Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, two participants (one from the active tDCS group and one from the sham tDCS group) were unable to attend a second in-person lab visit. Therefore, we modified our procedures to collect follow-up self-report data via an online survey for them. See Figure 1 for an overview of study procedures.

Figure 1.

Procedural Overview

Note. Experimental design and procedures. Part A depicts the flow of procedures from the beginning to end of the study. Part B depicts the VR public speaking environment and audiences which were used for speech tasks during behavioral assessments (BATs) and exposure therapy trials. Part C depicts the electrode placements for the study’s tDCS montage.

VR environment.

We administered VR using the VIVE virtual reality system29 equipment, and the VR public speaking environments and audiences were produced using Virtual Orator software.30 To provide an ecologically valid setting for college student participants, avatars in VR mimicked informally dressed young adults in a small classroom setting. Each VR audience was composed of eight avatars (see Figure 1). The audiences were always equally distributed according to gender but varied in ethnic composition to create in-group/out-group (75% same/different ethnicity as the participant) contexts. Audience members were designed by Virtual Orator using Northern-European-appearing avatars from Character Generator31 as a foundation; Latinx-appearing avatars were generated by modifying morphologies and skin tones to match reference photos.

Speech tasks.

Participants delivered speeches while standing to audiences in VR for both behavioral approach tests (BATs) and exposure therapy trials. Participants selected topics to present out of a list of five topics used in previous studies: abortion, corporal punishment in schools, mandatory seatbelt laws, nuclear power, or the American healthcare system.32 Participants were required to select one topic for the BAT speeches, and a different topic for the speeches completed during exposure therapy trials to reduce practice effects. Consistent with prior research designs, participants were given three minutes to prepare their speeches before BATs and exposure therapy, but they were not allowed to use notes during their speeches.32

BAT and exposure therapy trials were structured similarly. BATs involved giving a speech in VR for up to five minutes to two audiences: one in-group audience and one out-group audience. Order of audience context was randomized. For exposure therapy, participants delivered six three-minute speeches in VR, a procedure similar to previous studies.33 The six trials were divided into three pairs of trials, with each pair of trials including one in-group audience and one out-group audience. The order of the in-group and out-group contexts was randomized within each pair of trials using a blocked randomization procedure. Thus, participants presented to an ethnic in-group audience (50%) and to an ethnic out-group audience (50%) equally often.

Stimulation montage.

A battery-driven neuroConn DC-Stimulator34 (product still investigational and not yet approved by the FDA) was used to deliver a single continuous direct current. Two 5 × 7 cm2 electrodes within saline-dampened sponges were used to deliver 20 minutes of current35 at 2 mA.36 For the sham condition, current was delivered for 20 seconds ramping up and for 20 seconds ramping down to provide a physical stimulation sensation. The anode was centered above the eyebrow ridge over the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC; Fpz), and the reference (cathode) electrode was centered above the inion (Oz) because these electrode placements enhance activation in the vmPFC.37 We focused on the vmPFC because this portion of the mPFC is involved in learning and retaining fear extinction.38,39 Participants were randomly assigned to the active anodal or sham condition, and treatment assignment was double-blinded via use of a code inputted into the tDCS device to administer the assigned stimulation protocol. Stimulation was administered concurrently during exposure therapy, with exposure trials beginning five minutes after the start of stimulation.

Measures

Eligibility prescreen.

To be eligible, adult participants had to self-identify as white (i.e., both non-Hispanic/Latino and white/Caucasian) or Latinx (i.e., Hispanic/Latino and any racial category). Public speaking anxiety was assessed via two questions used in previous exposure therapy studies for public speaking anxiety.40,41 Eligible participants had to report a six or above on a scale from 0 (no anxiety) to 8 (extreme anxiety) in response to, “How anxious would you feel giving a formal speech before a live audience?” Additionally, they had to respond with a five or above on a scale from 0 (never avoid) to 8 (always avoid) to the question, “How likely would you be to avoid taking a class that required an oral presentation?” To receive tDCS, potential participants had to deny experiencing conditions which might make them more susceptible to unpleasant side effects related to tDCS: current pregnancy, history of seizures or other significant neurological conditions, history of traumatic brain injury within the past year, metallic implants in the skull, or current use of anti-convulsant, antipsychotic, or sedative/hypnotic medications.22

Intergroup anxiety.

The Intergroup Anxiety Scale (IAS)42 is a 11-item measure of intergroup anxiety with good internal consistency and validity.43 The internal consistency of the IAS in the current study was good at baseline () and follow-up ().

Public speaking anxiety.

The Personal Report of Public Speaking Anxiety (PRPSA)44 is a 34-item measure of public speaking anxiety with good internal consistency and validity.45 The internal consistency of the PRPSA in the current study was good at both baseline () and follow-up ().

Self-statements during public speaking.

The Self-Statements During Public Speaking Scale (SSPS)46 is a 10-item measure of positive and negative statements made to oneself during public speaking. The SSPS has good internal consistency, convergent and divergent validity, and a consistent factorial structure with this measure.46 The internal consistency of the SSPS in the current study was good for positive self-statements at baseline () and follow-up () and for negative self-statements at baseline () and follow-up ().

Behavioral approach duration.

For BAT speeches, participants could choose to stop before the five-minute time limit.47 Therefore, the length of each speech was used as a measure of behavioral approach toward a feared situation.

Subjective ratings for speech tasks.

Participants reported their expected and peak anxiety and social threat for speech tasks using an adaptation of the subjective units of distress scale (SUDS).48 Expected and peak anxiety, respectively, were rated before and after each BAT and exposure trial on a scale from 0 (no anxiety at all) to 100 (the highest anxiety imaginable). Additionally, expected and peak social threat (e.g., embarrassing themselves), respectively, were rated before and after each BAT and exposure trial on a scale from 0 (no harm at all) to 100 (very severe harm). Participants were informed of the upcoming audience context (in-group versus out-group) before rating expected anxiety and threat.

Blinding questionnaire.

After receiving stimulation and completing exposure trials, participants reported whether they thought they received active or sham tDCS. According to a chi-square test of independence with continuity correction, tDCS condition was independent of whether participants believed they received active or sham stimulation (, ), indicating the tDCS condition was effectively blinded.

Data Analysis Plan

Statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS version 28.0.1.49 First, we conducted baseline analyses to test for differences between tDCS conditions (active versus sham) and audience contexts (in-group versus out-group) at baseline using t-tests for self-report questionnaires and ANOVAs (tDCS × audience) for BAT data. Next, we examined data collected during the exposure therapy trials, using ANOVAs (tDCS × audience × time). Lastly, we conducted one-month follow-up analyses to test for changes from baseline to follow-up using ANOVAs for self-report measures (tDCS × time) and BAT data (tDCS × audience × time). For consistency, Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were reported where applicable (i.e., involving three or more within-subject comparisons) to account for sphericity violations. When probing significant effects, Bonferroni adjustments accounted for multiple comparisons.

We conducted power analyses using GPower 3.1.9.450 for two-way interactions and PANGEA51 for three-way interactions. For our analyses of changes over time in self-report measures (active vs sham tDCS × two measurement timepoints), we needed a total sample size of to have 80% power to detect a moderate-to-large effect () for 2 × 2 (between × within subject) interactions. For our analyses of changes over time in BAT measures (active vs sham tDCS × in-group vs out-group audience × two measurement timepoints), we needed a total sample size of to have 80% power to detect a moderate-to-large effect () for 2 × 2 × 2 (between × within × within subject) interactions. For our analyses of treatment process measures (active vs sham tDCS × in-group vs out-group audience × three measurement timepoints), we needed a total sample size of to have 80% power to detect a moderate-to-large effect () for 2 × 2 × 3 (between × within × within subject) interactions. Given our obtained sample size of , we achieved appropriate power to detect moderate-to-large two-way interactions, although findings from three-way interactions should be interpreted as preliminary because they were underpowered.

Results

Baseline Analyses

Participant’s performance at baseline answered the following two questions. First, was randomization effective in equating the active and sham tDCS groups at baseline? Second, do people with public speaking anxiety experience greater fear in the context of an ethno-racial out-group? (See Table 2 for descriptive statistics and Supplemental Digital Content 1 for a table of baseline results.)

Table 2.

Treatment Outcome Descriptive Statistics for Active and Sham tDCS Groups

| Active tDCS | Sham tDCS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Baseline | Follow-up | Baseline | Follow-up | ||

|

| |||||

| Public Speaking Anxiety | 149.67 (8.22) | 133.47 (16.69) | 144.77 (11.75) | 131.15 (17.87) | .01 |

| Negative Self-Statements | 16.00 (6.50) | 12.33 (6.95) | 14.00 (6.94) | 11.77 (6.83) | .03 |

| Positive Self-Statements | 9.07 (4.76) | 11.13 (5.14) | 8.69 (5.31) | 10.69 (4.57) | <.01 |

| Intergroup Anxiety | 4.53 (1.53) | 3.84 (1.25) | 4.56 (1.45) | 4.03 (1.40) | .01 |

| In-group BAT | |||||

| Expected anxiety | 70.00 (16.53) | 38.86 (18.69) | 63.17 (28.89) | 37.58 (24.97) | <.01 |

| Peak anxiety | 58.07 (32.44) | 36.07 (20.96) | 64.08 (24.57) | 26.25 (26.64) | .08 |

| Expected threat | 46.07 (30.08) | 29.43 (23.83) | 47.25 (35.79) | 33.50 (26.12) | .02 |

| Peak threat | 40.00 (31.99) | 14.29 (17.19) | 43.50 (35.42) | 21.58 (25.20) | <.01 |

| Duration (seconds) | 117.57 (49.41) | 128.50 (51.52) | 164.92 (95.64) | 141.00 (65.31) | .03 |

| Out-group BAT | |||||

| Expected anxiety | 66.07 (22.72) | 42.50 (21.10) | 66.75 (23.94) | 40.25 (25.40) | - |

| Peak anxiety | 66.79 (27.85) | 34.64 (21.26) | 71.67 (20.50) | 27.92 (24.16) | - |

| Expected threat | 37.79 (32.94) | 31.43 (25.07) | 52.67 (29.48) | 32.50 (27.26) | - |

| Peak Threat | 40.71 (32.75) | 13.86 (19.94) | 46.67 (35.38) | 19.33 (21.47) | - |

| Duration (seconds) | 128.43 (76.21) | 145.07 (59.67) | 159.08 (108.70) | 168.25 (71.90) | - |

Note. Results are reported in the format M (SD). The column refers to the partial effect sizes for the tDCS × time interaction for each outcome, collapsed across pairs of audience contexts for BAT outcomes. Therefore, these effect sizes represent the magnitude of differences between tDCS groups in changes over time. Additional effect sizes and model results are reported in Supplemental Digital Content 3.

Our results suggested that randomization was effective in equating tDCS groups (no significant tDCS × audience interactions, or main effects of tDCS at baseline; ). Additionally, participants with public speaking anxiety reported greater peak anxiety to an out-group vs in-group audience at baseline (significant main effect of audience at baseline; ; , , ). This suggests that an ethno-racial out-group context, compared to an in-group context, provoked greater anxiety among individuals with social anxiety symptoms.

Treatment Process Analyses

Treatment process analyses on measures collected during exposure therapy were used to address two research questions. First, does tDCS targeting the mPFC facilitate the extinction of public speaking anxiety, especially in a difficult-to-extinguish context, such as in the context of an ethno-racial out-group? Second, can standard exposure therapy procedures produce habituation in both in-group and out-group ethno-racial contexts? (See Table 3 for descriptive statistics and Supplemental Digital Content 2 for a table of treatment process results.)

Table 3.

Treatment Process Descriptive Statistics for Active and Sham tDCS Groups

| Active tDCS | Sham tDCS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Pair 1 | Pair 2 | Pair 3 | Pair 1 | Pair 2 | Pair 3 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Expected anxiety | .03 | ||||||

| In-group | 59.69 (19.62) | 47.81 (19.23) | 42.31 (20.89) | 62.13 (21.29) | 58.87 (25.87) | 49.00 (24.36) | |

| Out-group | 60.94 (13.93) | 54.69 (19.02) | 45.94 (18.82) | 61.33 (21.00) | 55.20 (21.99) | 48.07 (23.72) | |

| Peak anxiety | .01 | ||||||

| In-group | 55.63 (20.07) | 47.56 (20.03) | 36.56 (21.11) | 59.07 (24.88) | 50.80 (22.01) | 43.73 (27.09) | |

| Out-group | 56.88 (19.05) | 45.44 (18.67) | 39.38 (18.34) | 56.47 (24.35) | 52.07 (27.88) | 40.53 (23.56) | |

| Expected threat | .06 | ||||||

| In-group | 33.87 (29.71) | 27.31 (23.29) | 25.19 (22.01) | 41.00 (31.46) | 42.53 (29.18) | 34.87 (25.53) | |

| Out-group | 37.19 (27.63) | 32.81 (27.08) | 27.31 (24.60) | 37.33 (31.10) | 38.67 (28.50) | 31.53 (26.18) | |

| Peak threat | <.01 | ||||||

| In-group | 34.94 (29.10) | 27.50 (20.90) | 22.31 (22.19) | 42.47 (33.03) | 34.53 (26.82) | 30.47 (27.26) | |

| Out-group | 31.44 (29.55) | 25.63 (22.87) | 22.63 (22.52) | 40.07 (31.98) | 36.53 (34.04) | 28.53 (24.61) | |

Note. Results are reported in the format M (SD). The column refers to the partial effect sizes for the tDCS × time interaction for each outcome, collapsed across pairs of audience contexts. Therefore, these effect sizes represent the magnitude of differences between tDCS groups in changes over time. Additional effect sizes and model results are reported in Supplemental Digital Content 2.

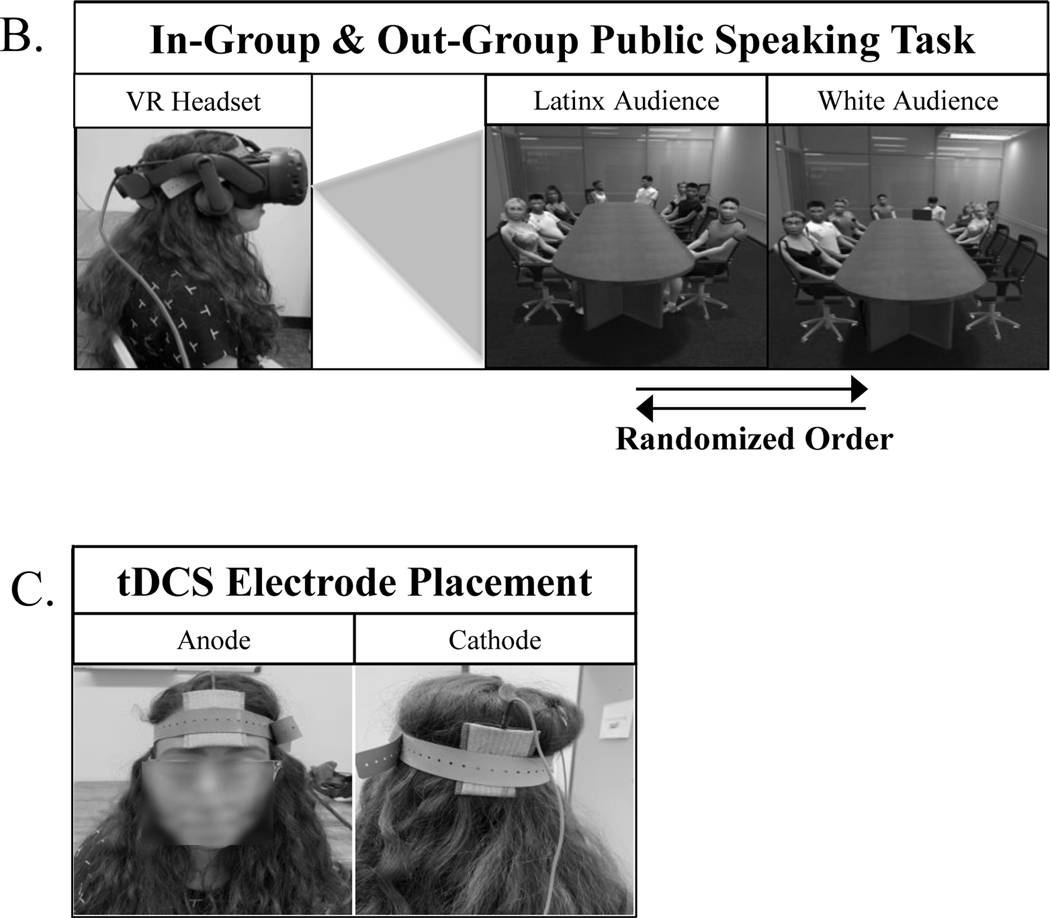

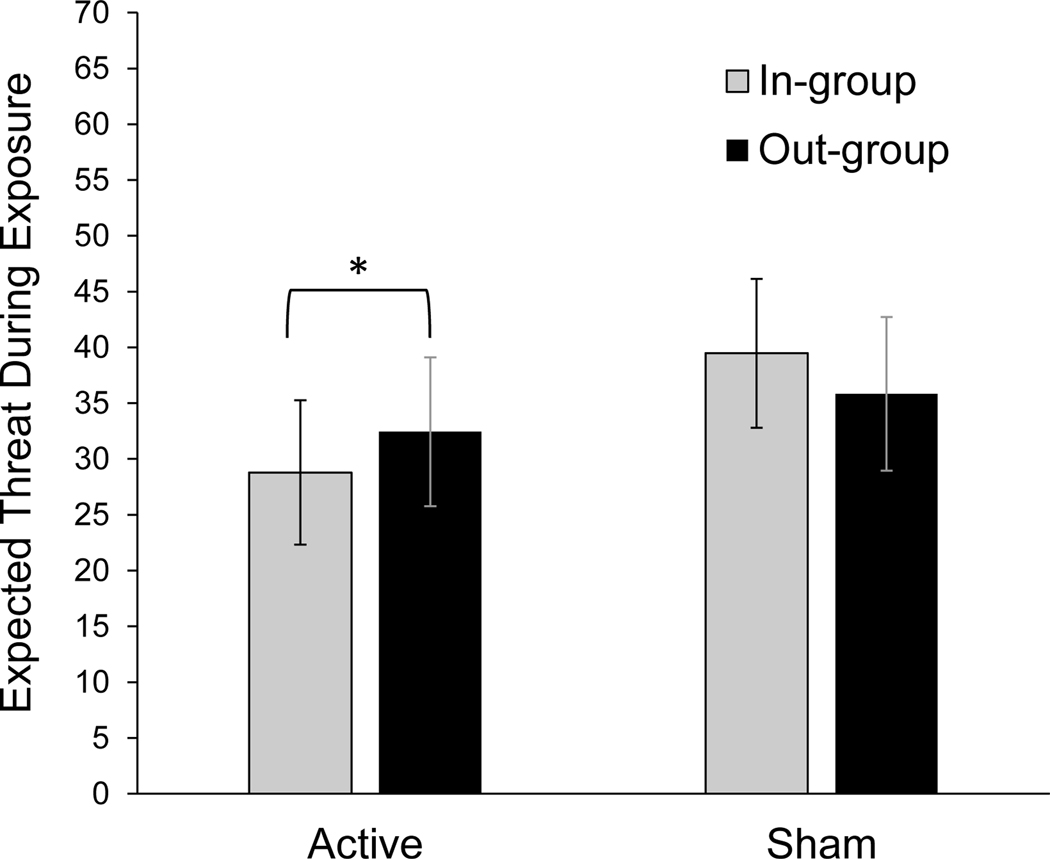

With regard to the first question, the inclusion of tDCS did not facilitate extinction (no significant tDCS × audience × time, or tDCS × time interactions; ). Contrary to hypotheses, active tDCS temporarily increased contextual discrimination, introducing an in-group bias (tDCS × audience interactions for expected anxiety (, , ) and expected threat (, , ; see Figure 2). For those receiving active tDCS, in-group ratings were lower than out-group ratings for expected anxiety ( ; ) and expected threat ( ; ). However, for the sham tDCS group, the in-group was rated numerically higher for expected anxiety ( ; ) than expected threat ( ; ). Contrary to hypotheses, this suggests that the effect of active anodal tDCS introduced an in-group bias, increasing in-group favoritism.

Figure 2.

Treatment Process tDCS × Audience Interactions

Note. For participants receiving active stimulation targeting the mPFC, in-group audiences were rated with lower expected threat ( () vs (); ) and anxiety ( () vs (); ) than out-group audiences. For participants receiving sham stimulation, there were no significant differences between in-group and out-group audiences for expected anxiety ( () vs (); ) and expected threat ( () vs (); ). The means displayed above are marginal means representing an average of all trials conducted during VR exposure therapy.

In regard to the second question, overall patterns suggest that participants showed evidence of habituation across exposure therapy trials, that was similar across in-group and out-group contexts (main effects of time for anxiety and threat ratings (), but there was no audience × time interaction; ).

One-Month Follow-Up Analyses

We evaluated changes from baseline to one-month follow-up, thereby addressing three questions. First, did tDCS stimulation facilitate the long-term reduction of public speaking anxiety? Second, can standard exposure therapy procedures, conducted in both in-group and out-group ethno-racial contexts, reduce intergroup anxiety? Third, were our exposure therapy procedures generally effective in producing long-term reductions in anxiety? The third question served as a manipulation check to ensure that our modified one-session protocol in VR was effective for reducing the severity of public speaking anxiety. (See Table 2 for descriptive statistics and Supplemental Digital Content 3 for a table of follow-up results.)

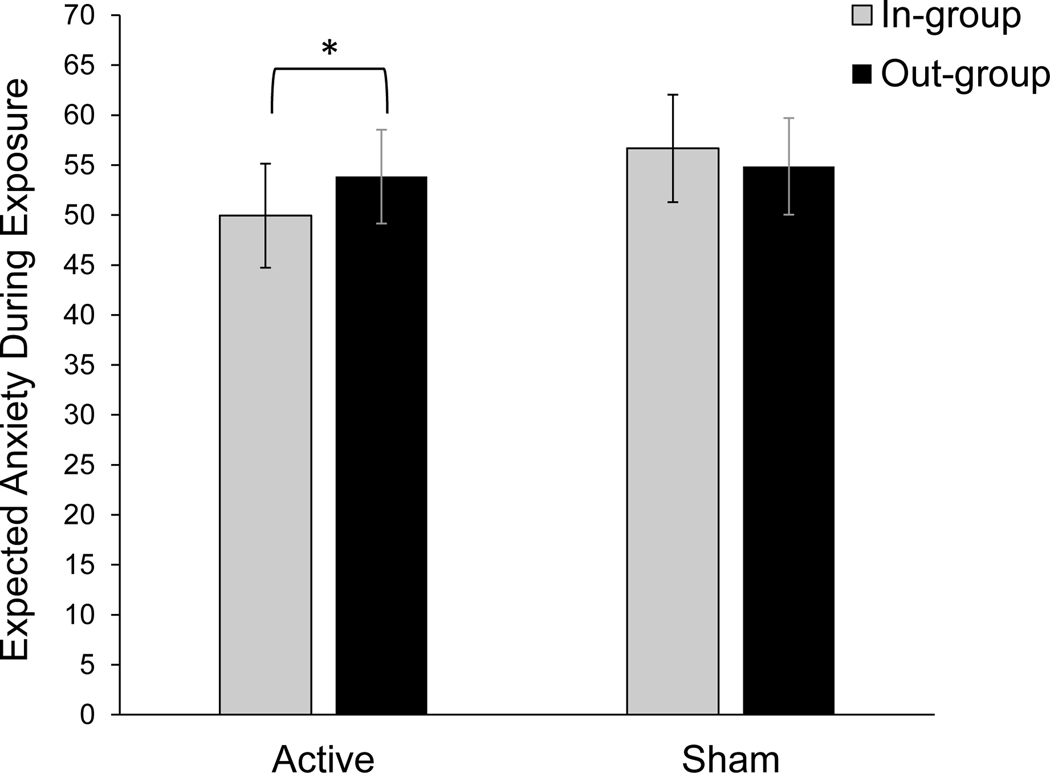

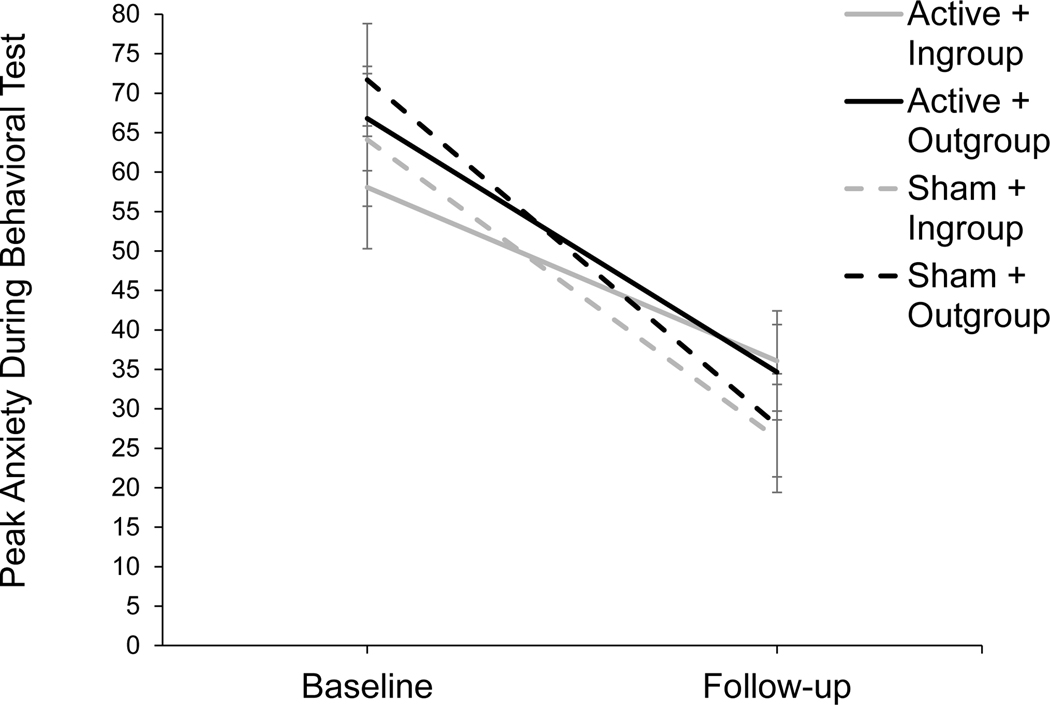

In regard to the first question, we found that that tDCS did not facilitate the long-term reduction of public speaking anxiety (no significant tDCS × audience × time, or tDCS × time interactions; ). However, in regard to the second question, conducting standard exposure therapy procedures in ethno-racial in-group and out-group contexts was somewhat effective for reducing intergroup anxiety. Specifically, we observed an audience × time interaction for peak anxiety at a trend level (, , ; see Figure 3). A simple effects analysis found that peak anxiety ratings were higher for the out-group vs in-group at baseline ( ; ), but this in-group bias was eliminated at follow-up ( ; ). Exposure therapy closed the gap between the subjective anxiety experienced in an in-group vs out-group ethno-racial context.

Figure 3.

Treatment Outcome Audience × Time Interaction

Note. Performance for tDCS conditions are shown separately for descriptive purposes; however, the significant interaction was an audience × time interaction and did not include tDCS condition. Audience context (in-group vs out-group) moderated the reduction from baseline to one-month follow up in ratings of peak anxiety reported during BATs, behavioral tests of public speaking fear. Simple effects analyses of means collapsed across tDCS condition demonstrate an in-group bias at baseline (in-group () vs out-group (); ) that is no longer present at one-month follow-up (in-group () vs out-group (); ). Thus, conducting exposure therapy in both in-group and out-group contexts may reduce in-group bias, although tDCS was not shown to potentiate this effect.

As additional evidence that our exposure therapy procedure reduced intergroup anxiety, we observed reductions on the intergroup anxiety questionnaire across time (significant main effect of time; , , ). We also observed an effect of audience for BAT durations (, , ), such that participants spoke longer to out-group audiences compared to in-group audiences ( ). However, this effect did not include time (i.e., was not an audience × time interaction). Therefore, we cannot conclude that participants experienced a reduction in anxiety-driven avoidance behavior toward an out-group audience by speaking longer to out-group audiences over time. Instead, participants were observed to speak longer to out-group audiences overall when accounting for both baseline and follow-up BATs.

In regard to the third question, the single-session exposure therapy protocol was effective for producing significant reductions in public speaking anxiety (main effect of time for anxiety and threat ratings during public speaking tests, and for all public speaking anxiety questionnaires; ). The only exception to this pattern of findings occurred in the context of BAT duration, such that there was no significant change in BAT duration from baseline to one-month follow-up (). This may be due to the specific exposure procedures used in this study that were shorter than the maximum duration allowed for the test speeches at baseline and follow-up (3 min total vs up to 5 min). Therefore, participants may have simply been responding to practice trials that unintentionally trained them to give shorter speeches.

Discussion

We recruited participants with the public speaking subtype of social anxiety symptoms to test (a) whether ethno-racial context influences the intensity of social anxiety symptoms, (b) whether varying ethno-racial context during exposure therapy reduces intergroup anxiety, and (c) whether targeting the mPFC with a noninvasive stimulation method (tDCS) during exposure therapy would facilitate the extinction of public speaking anxiety especially in difficult-to-extinguish contexts such as an ethno-racial out-group (intergroup) context. We found that an ethno-racial out-group context exacerbates anxiety among people with social anxiety symptoms. Additionally, intergroup anxiety may be responsive to standard exposure therapy procedures when they are adapted to include both in- and out-group contexts. However, contrary to predictions, stimulating the mPFC during exposure therapy produced a temporary bias towards perceiving safety in the in-group, as indicated by lower expected threat and anxiety ratings; this effect was not detected at one-month follow-up assessment. Each finding, alongside related limitations and implications, is discussed below.

The Importance of Ethno-racial Context for Social Anxiety Treatment

Prior studies reported heightened fear response to an out-group vs in-group context. However, these were basic science studies, in which fear responses were conditioned in the laboratory.8,9 Our study extends this finding to individuals who endorse fear and avoidance of public speaking and, thus, have naturally acquired fear responses to social settings. Specifically, participants with public speaking anxiety endorsed higher anxiety after giving a speech to an ethno-racial out-group vs in-group during their first public speaking test in the lab. This evidence highlights a new potential treatment target. Directly targeting heightened anxiety in out-group contexts may be a promising pathway for improving social anxiety treatment.

The moderating influence of ethno-racial minority status is important to consider. Members of ethno-racial minority groups likely experience discrimination, and this history would be expected to exacerbate anxiety in an out-group setting and make it more resistant to extinction. However, it is important to note that, due to the ongoing danger of ethno-racial discrimination particularly in the U.S.,52 heightened anxiety in an ethno-racial out-group may promote adaptive protective responses. Thus, caution is warranted when determining how out-group anxiety should be addressed in the context of treatment, particularly among marginalized ethno-racial groups. One pathway would be to target out-group anxiety among ethno-racial majority groups and reduce the related frequency of ethno-racial discrimination. This could result in lower intergroup anxiety among both majority and minority ethno-racial groups. Regardless of the specific treatment pathway, it is important to incorporate the effect of ethno-racial context on individuals’ experiences of social anxiety into case conceptualization.

The Influence of Standard Exposure Therapy Procedures on Intergroup Anxiety

We found that standard exposure therapy can reduce intergroup anxiety, and we replicated earlier studies showing that virtual reality exposure therapy for public speaking anxiety is effective.53 Remarkably, effects lasted at least one month, even after one brief session of exposure therapy. We extended these findings to intergroup anxiety. This provides support for prior arguments10 that traditional treatments like exposure therapy could target intergroup anxiety.

One limitation is that we did not include a comparison group that received exposure therapy to one context only. Future studies should compare the effects of exposure therapy protocols that involve both in- and out-group contexts, with protocols that involve an in-group context alone. This would strengthen the conclusion that the addition of an out-group context to exposure therapy provided greater improvement in intergroup anxiety. Importantly, participants reported greater anxiety after speaking to an out-group audience at baseline, but there was no discrepancy between in-group and out-group anxiety ratings at follow-up. This highlights the efficacy of this protocol for targeting out-group (i.e., intergroup) anxiety.

The Influence of tDCS Targeting mPFC on Social Anxiety in an Out-Group Context

We chose to target the mPFC with tDCS given evidence across multiple studies suggesting that stimulating the mPFC could enhance the effects of exposure therapy.17,18 For example, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation targeting mPFC has been shown to accelerate responses to exposure therapy in people with heights phobia,54 and tDCS targeting mPFC has been shown to produce more rapid extinction of lab-conditioned fear responses.55 We did not see the same benefits as previous studies; tDCS targeting mPFC did not enhance the ability of VR exposure therapy to reduce public speaking anxiety.

Given the different symptom presentations across anxiety disorders, perhaps mPFC is not the best stimulation target to enhance exposure therapy for all types of anxiety disorders. For example, because mPFC activity has been associated with maladaptive self-focused attention among individuals with social anxiety,56 it is possible that mPFC may not be a beneficial stimulation target during exposure therapy for social anxiety. In contrast, other studies have found success in reducing social anxiety using different stimulation protocols as stand-alone treatments (e.g., enhancing activation of left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and inhibiting activation of mPFC).57 However, unlike our study, these studies did not deliver stimulation concurrently with a behavioral therapy as a means of enhancing therapy outcomes. Therefore, additional research is needed to address the question of which brain area is the most beneficial stimulation target to enhance existing therapies for social anxiety, such as exposure therapy, which is an important component of gold standard treatments for social anxiety.

Although it is possible that tDCS did not augment exposure therapy, it also is possible that the timing of our study procedures interfered with our ability to detect the effects of tDCS. For example, in studies using tDCS to enhance memory training, some findings suggest that tDCS enhances skill acquisition by producing a faster learning rate and longer-lasting effects.28,58 In our case, we might not have been able to detect a faster rate of fear extinction or longer-lasting effects among our active tDCS group due to using only one session of exposure and only one follow-up time point. Future research involving more exposure sessions and additional follow-ups may be more sensitive to detecting changes in fear extinction, similar to what has been found for tDCS-enhanced memory training.

We also expected that targeting the mPFC would reduce intergroup anxiety, given the role of the mPFC in social cognitive processes such as in-group affiliation.21 Surprisingly, however, our stimulation protocol targeting the mPFC did not eliminate the discrepancy between in-group and out-group threat perceptions. Unexpectedly, active tDCS increased the discrepancy between in-group and out-group threat perceptions by increasing in-group favoritism. Notably, these effects were temporary and did not persist through one-month follow-up.

However, the results inform how stimulating the mPFC during exposure therapy may influence fear extinction learning. Specifically, anodal tDCS lowers the threshold for neural firing, but does not initiate neuronal firing. We speculate that anodal tDCS may increase mPFC related safety signaling15 in response to a context established as signaling safety: the in-group context. This could explain why the active tDCS group displayed lower ratings of expected anxiety and threat toward the in-group audience. TDCS may heighten safety signaling in contexts that are already associated with greater safety, such as an in-group context. Anodal tDCS targeting the mPFC may be insufficient for introducing safety signaling in a new context. However, it may strengthen existing safety signaling. Further research in clinical populations, including within distinct sub-groups, is needed given observations that neurostimulation can have nearly equal and opposite effects as a function of individual differences58,59 and as our understanding of the underlying neural mechanism of neurostimulation-induced changes takes shape.60,61 No treatment is ideal for everyone, and determining in whom neurostimulation is effective remains an area of intense research.62

General Limitations

Our sample size was limited which reduced our power to detect effects, particularly for three-way interactions. However, we observed small effect sizes for three-way interactions (s ≤ .06). Given the limited clinical impact of effect sizes this small, a replication study to fully power three-way interaction terms may not be the best use of resources. In other words, results suggest that there was not a clinically meaningful interaction effect of tDCS × audience context × time. However, we were powered to detect moderate-to-large two-way interaction effects between tDCS condition and in/out-group contexts, which did highlight important conclusions regarding how mPFC activation (i.e., during stimulation) may encourage ethno-racial in-group favoritism. Although tDCS targeting mPFC was insufficient in our case for introducing safety signaling (as evidenced by fear dampening) in an ethno-racial out-group audience, future follow up studies could examine the benefits of mPFC activation as a means of strengthening existing safety signaling, such as in an ethno-racial in-group context.

As an additional limitation, the self-report measures used in this study may have been influenced by social desirability. A desire to appear equitable may have influenced participants’ ratings for in- versus out-group settings, and for self-reported levels of intergroup anxiety. However, through randomization, this pattern would be equal across both active and sham tDCS groups. Furthermore, we did not incorporate neuroimaging to permit individualized targeting. However, we selected a protocol that has stimulated the mPFC in prior studies.37 This approach has some practical utility because the greater technical requirements for individualized imaging may prohibit easy translation to clinics. Yet this approach does leave unanswered questions about the extent to which this stimulation protocol effectively targeted the mPFC across study participants.

Another limitation relates to our BAT procedures. Unlike other BAT outcomes, no improvements over time were observed for BAT duration. Participants did not speak longer over time, which would have indicated fear reduction. This may be an artifact of the specific protocol; participants practiced speeches during exposure therapy that were shorter than the maximum duration allowed for the test speeches (3 min total vs up to 5 min). We used this procedure to avoid floor effects by making the test context more challenging than the training context. However, it may have unintentionally trained participants to engage in shorter speeches. Future research should ensure BAT speech lengths match exposure trial speech lengths to allow for better detection of changes in behaviorally measured public speaking fear.

Future researchers should record speeches to detect avoidance behaviors beyond speech duration alone. In addition to giving shorter speeches, people with greater public speaking fear pause for longer durations and speak fewer words.63 It is possible that our participants gave longer speeches to out-group audiences by pausing for longer durations, which is another form of avoidance behavior. This would be consistent with their self-report ratings, which indicated greater anxiety in out-group contexts. However, this explanation requires additional future testing.

Conclusions

The findings from this study have important implications. First, it is important to assess intergroup anxiety (i.e., fear towards out-groups) and consider its contribution to social anxiety. Second, findings support the role of the mPFC in promoting ethno-racial in-group bias, and stimulating the mPFC during exposure may reduce anxiety in contexts that are already perceived as safe, such as in-group contexts. Finally, these findings provide support that standard exposure therapy procedures can be easily adapted to reduce intergroup anxiety among people with social anxiety symptoms.

Supplementary Material

Source of Funding:

This project is supported by an award from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health under grant number U54GM104944. Research reported in this publication was also supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20 GM103650. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03743571

Data Availability:

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Beesdo K, Bittner A, Pine DS, et al. P.4.b.004 Social anxiety disorder: patterns of incidence and secondary depression risk. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007;17:S511–S512. doi: 10.1016/S0924-977X(07)70788-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aderka IM, Hofmann SG, Nickerson A, Hermesh H, Gilboa-Schechtman E, Marom S. Functional impairment in social anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26(3):393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feske U, Chambless DL. Cognitive behavioral versus exposure only treatment for social phobia: a meta-analysis. Behav Ther. 1995;26(4):695–720. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80040-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loerinc AG, Meuret AE, Twohig MP, Rosenfield D, Bluett EJ, Craske MG. Response rates for CBT for anxiety disorders: need for standardized criteria. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;42:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mineka S, Zinbarg R. A contemporary learning theory perspective on the etiology of anxiety disorders: it’s not what you thought it was. Am Psychol. 2006;61:10–26. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.1.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Åhs F, Rosén J, Kastrati G, Fredrikson M, Agren T, Lundström JN. Biological preparedness and resistance to extinction of skin conductance responses conditioned to fear relevant animal pictures: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;95:430–437. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Giudice M. Åhs et al. ’s (2018) Systematic review on biological preparedness and resistance to extinction: a commentary and reanalysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;120:13–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mallan KM, Sax J, Lipp OV. Verbal instruction abolishes fear conditioned to racial out-group faces. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2009;45(6):1303–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olsson A, Ebert JP, Banaji MR, Phelps EA. The role of social groups in the persistence of learned fear. Science. 2005;309(5735):785–787. doi: 10.1126/science.1113551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birtel MD, Crisp RJ. Psychotherapy and social change: utilizing principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy to help develop new prejudice-reduction interventions. Front Psychol. 2015;6. Accessed October 24, 2022. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etkin A, Wager TD. Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: a meta-analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. AJP. 2007;164(10):1476–1488. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lebrón K, Milad MR, Quirk GJ. Delayed recall of fear extinction in rats with lesions of ventral medial prefrontal cortex. Learn Mem. 2004;11(5):544–548. doi: 10.1101/lm.78604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgan MA, Romanski LM, LeDoux JE. Extinction of emotional learning: contribution of medial prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Lett. 1993;163(1):109–113. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90241-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrow BA, Elsworth JD, Inglis FM, Roth RH. An antisense oligonucleotide reverses the footshock-induced expression of fos in the rat medial prefrontal cortex and the subsequent expression of conditioned fear-induced immobility. J Neurosci. 1999;19(13):5666–5673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05666.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Likhtik E, Stujenske JM, A Topiwala M, Harris AZ, Gordon JA. Prefrontal entrainment of amygdala activity signals safety in learned fear and innate anxiety. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(1):106–113. doi: 10.1038/nn.3582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nili U, Goldberg H, Weizman A, Dudai Y. Fear thou not: activity of frontal and temporal circuits in moments of real-life courage. Neuron. 2010;66(6):949–962. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nuñez M, Zinbarg RE, Mittal VA. Efficacy and mechanisms of non-invasive brain stimulation to enhance exposure therapy: a review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2019;70:64–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vicario CM, Salehinejad MA, Felmingham K, Martino G, Nitsche MA. A systematic review on the therapeutic effectiveness of non-invasive brain stimulation for the treatment of anxiety disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;96:219–231. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mutz J, Edgcumbe DR, Brunoni AR, Fu CHY. Efficacy and acceptability of non-invasive brain stimulation for the treatment of adult unipolar and bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised sham-controlled trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;92:291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shivakumar V, Dinakaran D, Narayanaswamy JC, Venkatasubramanian G. Noninvasive brain stimulation in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Indian J Psychiatry. 2019;61(Suppl 1):S66. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_522_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Senholzi KB, Kubota JT. The neural mechanisms of prejudice intervention. In: Absher JR, Cloutier J, eds. Neuroimaging Personality, Social Cognition, and Character. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 2016:337–354. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800935-2.00018-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bikson M, Grossman P, Thomas C, et al. Safety of transcranial direct current stimulation: evidence based update 2016. Brain Stimul. 2016;9(5):641–661. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao H, Qiao L, Fan D, et al. Modulation of brain activity with noninvasive transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS): clinical applications and safety concerns. Front Psychol. 2017;8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruscio AM, Brown TA, Chiu WT, Sareen J, Stein MB, Kessler RC. Social fears and social phobia in the USA: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Psychol Med. 2008;38(1):15–28. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Census Bureau. Quickfacts: Reno city, Nevada. [United States Census Bureau QuickFacts Web site]. January 17, 2022. Available at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/renocitynevada [Google Scholar]

- 26.Batsikadze G, Moliadze V, Paulus W, Kuo MF, Nitsche MA. Partially non-linear stimulation intensity-dependent effects of direct current stimulation on motor cortex excitability in humans. J Physiol. 2013;591(7):1987–2000. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.249730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nitsche MA, Cohen LG, Wassermann EM, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation: state of the art 2008. Brain Stimul. 2008;1(3):206–223. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2008.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones KT, Stephens JA, Alam M, Bikson M, Berryhill ME. Longitudinal neurostimulation in older adults improves working memory. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0121904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.HTC Corporation. Products: find the right immersive experience for you [VIVE Web site]. January 31, 2023. Available at: https://www.vive.com/us/product/

- 30.Virtual Human Technologies. What is virtual orator? [Virtual Orator Web site]. January 31, 2023. Available at: https://virtualorator.com/

- 31.Autodesk. Welcome to autodesk character generator [Character Generator Web site]. January 31, 2023. Available at: https://charactergenerator.autodesk.com/

- 32.Hofmann SG, Newman MG, Ehlers A, Roth WT. Psychophysiological differences between subgroups of social phobia. J Psychopathol Clin Sci. 1995;104:224–231. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.104.1.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smits JAJ, Powers MB, Buxkamper R, Telch MJ. The efficacy of videotape feedback for enhancing the effects of exposure-based treatment for social anxiety disorder: a controlled investigation. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(12):1773–1785. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.neuroCare Group. DC-stimulator: stimulators for cranial electrotherapy and neuroscientific research. [neuroCare Web site]. January 31, 2023. Available at: https://www.neurocaregroup.com/neuroconn-dc-stimulator.html

- 35.Abend R, Jalon I, Gurevitch G, et al. Modulation of fear extinction processes using transcranial electrical stimulation. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6(10):e913–e913. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van’t Wout M, Longo SM, Reddy MK, Philip NS, Bowker MT, Greenberg BD. Transcranial direct current stimulation may modulate extinction memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Brain Behav. 2017;7(5):e00681. doi: 10.1002/brb3.681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abend R, Sar-el R, Gonen T, et al. Modulating emotional experience using electrical stimulation of the medial-prefrontal cortex: a preliminary tDCS-fMRI study. Neuromodulation. 2019;22(8):884–893. doi: 10.1111/ner.12787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phelps EA, Delgado MR, Nearing KI, LeDoux JE. Extinction learning in humans: role of the amygdala and vmPFC. Neuron. 2004;43(6):897–905. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quirk GJ, Garcia R, González-Lima F. Prefrontal mechanisms in extinction of conditioned fear. Biol Psychiatry.. 2006;60(4):337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Niles AN. Does affect labeling enhance exposure effectiveness for public speaking anxiety? Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of California, Los Angeles; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsao JCI, Craske MG. Timing of treatment and return of fear: effects of massed, uniform-, and expanding-spaced exposure schedules. Behav Ther. 2000;31(3):479–497. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(00)80026-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stephan WG, Stephan CW. Intergroup anxiety. J Soc Issues. 1985;41(3):157–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1985.tb01134.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lolliot S, Fell B, Schmid K, et al. Measures of intergroup contact. In: Boyle GJ, Saklofske DH, Matthews G, eds. Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Constructs. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 2015:652–683. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386915-9.00023-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCroskey JC. Measures of communication-bound anxiety. Commun Monogr. 1970;37(4):269–277. doi: 10.1080/03637757009375677 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mörtberg E, Jansson-Fröjmark M, Pettersson A, Hennlid-Oredsson T. Psychometric properties of the personal report of public speaking anxiety (PRPSA) in a sample of university students in Sweden. J Cogn Ther. 2018;11(4):421–433. doi: 10.1007/s41811-018-0022-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM. An instrument to assess self-statements during public speaking: scale development and preliminary psychometric properties. Behav Ther. 2000;31(3):499–515. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(00)80027-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amir N, Weber G, Beard C, Bomyea J, Taylor CT. The effect of a single-session attention modification program on response to a public-speaking challenge in socially anxious individuals. J Psychopathol Clin Sci. 2008;117:860–868. doi: 10.1037/a0013445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolpe J. The Practice of Behavior Therapy. [1st ed.]. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 49.IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows [computer program]. Version 28.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Westfall J. PANGEA: power analysis for general anova designs. Unpublished manuscript. 2016. http://jakewestfall.org/publications/pangea.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 52.Findling MG, Bleich SN, Casey LS, et al. Discrimination in the United States: experiences of Latinos. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(S2):1409–1418. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horigome T, Kurokawa S, Sawada K, et al. Virtual reality exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2020;50(15):2487–2497. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720003785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Herrmann MJ, Katzorke A, Busch Y, et al. Medial prefrontal cortex stimulation accelerates therapy response of exposure therapy in acrophobia. Brain Stimul. 2017;10(2):291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2016.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dittert N, Hüttner S, Polak T, Herrmann MJ. Augmentation of fear extinction by transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boehme S, Miltner WHR, Straube T. Neural correlates of self-focused attention in social anxiety. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2015;10(6):856–862. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsu128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jafari E, Alizadehgoradel J, Koluri FP, et al. Intensified electrical stimulation targeting lateral and medial prefrontal cortices for the treatment of social anxiety disorder: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, dose-comparison study. Brain Stimul. 2021;14(4):974–986. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2021.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jones KT, Gözenman F, Berryhill ME. Enhanced long-term memory encoding after parietal neurostimulation. Exp Brain Res. 2014;232(12):4043–4054. doi: 10.1007/s00221-014-4090-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gözenman F, Berryhill ME. Working memory capacity differentially influences responses to tDCS and HD-tDCS in a retro-cue task. Neurosci Lett. 2016;629:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.06.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johnson EL, Arciniega H, Jones KT, Kilgore-Gomez A, Berryhill ME. Individual predictors and electrophysiological signatures of working memory enhancement in aging. Neuroimage. 2022;250:118939. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2022.118939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jones KT, Johnson EL, Berryhill ME. Frontoparietal theta-gamma interactions track working memory enhancement with training and tDCS. Neuroimage. 2020;211:116615. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martin DM, Berryhill ME, Dielenberg V. Can brain stimulation enhance cognition in clinical populations? a critical review. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2022;Preprint(Preprint):1–19. doi: 10.3233/RNN-211230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lewin MR, McNeil DW, Lipson JM. Enduring without avoiding: pauses and verbal dysfluencies in public speaking fear. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1996;18(4):387–402. doi: 10.1007/BF02229142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.