Abstract

Executive Functions are a set of interrelated, top-down processes essential for adaptive goal-directed behaviour, frequently impaired across different neurodevelopmental disorders with variable degrees of severity. Many executive-function-training studies in children with neurodevelopmental disorders have focused on near effects, investigating post-treatment improvements on directly trained processes, while enhancements of skills not directly trained, defined as far effects, are less considered, albeit these could be extremely relevant for reducing the negative impact of a disorder’s core symptomatology. This systematic review and metanalysis aims to investigate the far effect outcomes after EF training in children with different types of neurodevelopmental disorders. 17 studies met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review, while 15 studies were selected in the metanalysis. An overall statistically significant effect size was found in the majority of far effect outcome measures considered in the studies. In particular, trainings on executive functions determine significant far effects on daily life functioning (0.46, 95% CI: [0.05–0.87]) and clinical symptoms (0.33, 95% CI: [0.15–0.51]). Despite a high variability of the results, intensity, frequency and the laboratory/life contexts dimension seem to be the most influential variables in determining far effects. This systematic review and metanalysis highlights the need to measure far effects of executive function training in neurodevelopmental disorders, selecting treatments not only on directly targeted processes, but also according to far impacts on the functional weakness of the disorder.

Keywords: Executive functions, Neurodevelopmental disorders, Far effect, Children

Introduction

Executive Functions: Definition

Executive Functions (EFs) represent a complex cognitive domain consisting of a set of top-down functions essential for adaptive goal-directed behaviour (Lehto et al., 2003; Miyake et al., 2000). EFs allow to formulate, plan, and organize ideas, cope with challenges and novelties, resist temptations and stay focused (Diamond, 2013). There is an ongoing debate as to the extent to which EFs can be fractionated or be unified into a single concept, both in adults and during development (for example, Morra et al., 2018). The model that may best explain executive functioning during development has been put forward by Adele Diamond (Diamond, 2013; Diamond & Ling, 2016), based on the conceptualizations of Miyake and colleagues (Friedman & Miyake, 2017; Miyake et al., 2000). Three early and distinct, although interrelated, components are identified in this model: inhibition, working memory and cognitive flexibility, whose interaction allows for the development of higher order EFs such as reasoning, problem solving and planning.

Inhibitory control is the ability to voluntarily resist temptations and impulsive actions (i.e., response inhibition) and to maintain selective attention by suppressing non relevant information (i.e., interference control). Inhibitory control is a fundamental skill involved both in cognitive activities, such as abstract reasoning, and in affective and emotional challenges allowing for more appropriate behaviours geared to internal or external goals (Zelazo & Mller, 2002; Zelazo et al., 2005). Inhibitory control supports the development of self-regulation, which requires the ability to maintain optimal cognitive, emotional and motivational arousal levels.

Working memory is a complex and multi-component mental system where information can be temporarily stored. It refers to the ability to actively maintain, monitor, update and manipulate verbal or visual-spatial information (Baddeley, 2003; Baddeley & Hitch, 1994; Smith & Jonides, 1999).

Cognitive flexibility is the ability to shift among different tasks, rules or mental contents. It supports creative thinking and the capacity to solve problems in different ways or see things from different perspectives.

EFs develop from preschool-age to childhood and into adulthood (Hughes et al., 2009; Huizinga et al., 2006; Lehto et al., 2003; Somerville & Casey, 2010) following maturation of prefrontal circuitries and their connections (Gilbert & Burgess, 2008). A single-undifferentiated executive factor was found in younger children of preschool age (Wiebe et al., 2011), whereas two separate dimensions consisting of inhibition and working memory were identified in children older than 5 years of age (Lee et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2012; Usai et al., 2014). Cognitive flexibility emerges later in development (Lee et al., 2013; Lehto et al., 2003) after the inhibition and working memory abilities have been established. Subsequently, these three basic EF components support the emergence of more complex and high-level EFs, including abstract reasoning, problem solving and planning, also referred to as Fluid Intelligence (Collins & Koechlin, 2012; Diamond, 2013; Lunt et al., 2012).

EFs have also been differentiated into “cool” and “hot” processes (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). The former domain, mainly subserved by the lateral prefrontal cortex, includes cognitive EF skills, elicited under relatively abstract, de-contextualized, non-affective conditions. Hot EF processes, mainly subserved by ventromedial prefrontal cortex and operating in motivationally and emotionally significant high-stakes situations, involve decision making, gratification delay and theory of mind (Wilson et al., 2018; Zelazo & Carlson, 2012).

In typically developing children, persistent difficulties affecting EFs, even if minor, represent a risk factor for development and can predict learning skills (Alloway & Alloway, 2010; Clark et al., 2014; LeFevre et al., 2013; Steele et al., 2012), academic achievement, job success, physical and mental wellbeing (McClelland et al., 2013; Moffitt et al., 2011; St Clair-Thompson & Gathercole, 2006).

EFs and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

It is currently well accepted that EFs are frequently impaired across different developmental disorders (Bausela Herreras et al., 2019; Pennington & Ozonoff, 1996). In some neurodevelopmental disorders an EF deficit may be a part of the core cognitive symptoms, while in others, a weakness of EFs is associated with specific deficits and help to define different subtypes of the disorder. Finally, poor executive abilities could be due to the reduced efficiency of other cognitive and sensory-motor functions.

A deficit in inhibition, and in particular in the ability to inhibit responses, was described as one of the core deficit of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Barkley, 2006, 2018). According to Barkley, a deficit in inhibition may cause, in turn, deficits in working memory, emotional regulation, reconstitution and internalization of language, leading to difficulties in the self-regulation of social interaction. Indeed, in ADHD other EFs are also compromised, notably working memory, divided attention, cognitive flexibility, planning, sustained attention and theory of mind (reviews: Elosúa et al., 2017; Jiménez-Figueroa et al., 2017; Lambek et al., 2011; Mary et al., 2016; Molnar, 2007; Pineda-Alhucema et al., 2018; Sergeant et al., 2002; Willcutt et al., 2005). In many studies, also the hot components of EF are impaired in individuals with ADHD, for example delay aversion, Theory of Mind and decision-making (reviews and meta-analysis: Bora & Pantelis, 2016; Groen et al., 2013; Mowinckel et al., 2015; Patros et al., 2016; empirical studies: Braaten & Rosén, 2000; Yang et al., 2011). Individuals with Intellectual Disability (ID) display worse EFs abilities than subjects with the same chronological and mental age (review and meta-analysis: Hronis et al., 2017; Spaniol & Danielsson, 2019; Tungate & Conners, 2021; empirical studies: Costanzo et al., 2013; Danielsson et al., 2010; Carney et al., 2013).

Children with Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) present EFs impairment in several domains, such as working memory (especially visuospatial), inhibitory control, attention, flexibility and metacognitive aspects of action planning (reviews and metanalysis: Leonard et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2013, 2017; empirical studies: Piek & Dyck, 2004; Sartori et al., 2020). Moreover, some evidence supports deficits in hot executive functions in children with DCD, as they have a high sensitivity to immediate gratification and to distracting emotional stimuli that underly low decision-making skills in emotionally activating situations (Rahimi-Golkhandan et al., 2014, 2015, 2016). Some difficulties in EFs remain distinctive features of individuals with DCD even in middle childhood, adolescence and early adulthood and limit children’s ability to improve automatic motor control and motor skills in daily activities (Bernardi et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2017).

Executive functions are fundamental for cognitive-linguistic translation (Berninger et al., 2012), the basis for language learning (Arrington et al., 2014; Berninger et al., 2012; Swanson, 2000, 2006), and appear to be in a reciprocal and complex relationship with language development (Bishop et al., 2013). It is therefore understandable that individuals with Developmental Language Disorders (DLDs) show cognitive difficulties that are not limited to the language domain. In particular, this clinical population presents difficulties with multiple components of EFs (meta-analysis and review: Kapa & Plante, 2015; Pauls & Archibald, 2016; empirical study: Andrés-Roqueta et al., 2021; Henry et al., 2012; Roello et al., 2015) and related functions such as processing speed ( Miller et al., 2001), non-verbal reasoning (Gallinat & Spaulding, 2014), procedural memory (Lum et al., 2012), motor control (Finlay & McPhillips, 2013). The most compromised EFs in this disorder are inhibition (Marini et al., 2020; Pauls & Archibald, 2016), cognitive flexibility (Pauls & Archibald, 2016), working memory both phonological (Duinmeijer et al., 2012; Marini et al., 2014) and visuospatial (Vugs et al., 2013), updating (Marini et al., 2020) and attentional control in verbal and non-verbal tasks (Dispaldro et al., 2013; Duinmeijer et al., 2012; Ebert & Kohnert, 2011; Finneran et al., 2009; Montgomery, 2008; Montgomery et al., 2009; Spaulding et al., 2008). Learning to read, text comprehension and mathematical competences are linked to working memory, inhibition, cognitive flexibility, updating and attentional control and planning (Cartwright & Smith, 2017; Gilmore & Cragg, 2014; Zaccoletti & Mason, 2018).

Individuals with Specific Learning Disorder (SLD) are characterized by difficulties in executive functions domains such as planning, cognitive flexibility, verbal and visuospatial working memory, attentional control and inhibition (El Wafa et al., 2020; Schuchardt et al., 2008). Developmental Dyslexia is the most studied disorder in terms of executive dysfunctions. Impairments or weaknesses have been reported in visual-spatial (Altemeier et al., 2008; Helland & Asbjørnsen, 2000; Menghini et al., 2010) and auditory attention (Buchholz & McKone, 2004; Casco & Prunetti, 1996; Dufor et al., 2007; Facoetti et al., 2000; Valdois et al., 2004), shifting (Hari & Renvall, 2001; Laasonen et al., 2012), verbal categorical and phonological fluency, verbal and visual short-term memory, verbal and visual-spatial working memory (Varvara et al., 2014), inhibition of irrelevant information (Brosnan et al., 2002; Everatt et al., 1997; Reiter et al., 2005), maintaining relevant information in working memory (meta-analysis: (Booth et al., 2010). In particular, the working memory deficit is considered one of the major markers of Dyslexia, both in its verbal and visuospatial components (Bacon et al., 2013; Brosnan et al., 2002; Helland & Asbjrnsen, 2004; Martinussen & Tannock, 2006; Menghini et al., 2011; Poblano et al., 2000; Smith-Spark & Fisk, 2007; Swanson et al., 2009).

EFs have been found to be frequently impaired in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), characterized by a deficit in cognitive flexibility, planning and inhibiting preponderant responses (Hill, 2004; Jiménez-Figueroa et al., 2017; Kenworthy et al., 2005; Landa & Goldberg, 2005; Lopez et al., 2005; Ozonoff et al., 1994; Rinehart et al., 2001; Robinson et al., 2009; Shu et al., 2001; Verté et al., 2005).

Finally, EFs are crucial for adaptive behaviour, in as much as efficient executive functioning during child development is able to predict health and well-being in adulthood (Moffitt et al., 2011). Considering that especially in childhood, EFs are indeed highly responsive to environmental influences (Jolles & Crone, 2012; Klingberg, 2010), it is important to identify early EF impairments in order to intervene and improve developmental trajectories.

EF Interventions

Convergent evidence suggests that it is possible to improve EFs through cognitive training (Diamond & Lee, 2011) and some findings demonstrated a strengthening of the neural circuits underlying the trained EFs by intensive practice (Brehmer et al., 2011; Crespi et al., 2018; McNab et al., 2009; Rueda et al., 2012). Given the importance of EFs in development and their variability in the severity of their impairment in different neurodevelopmental disorders, many studies have analyzed the effectiveness of different approaches both for the enhancement of EFs and for the generalization effect on other cognitive and daily life functioning. Some key principles of clinical practice for an intervention to be helpful foresee contextual support and the use of compensatory aids, the use of problem-solving and metacognitive strategies aimed at improving specific task trained but also applicable to a variety of everyday situations (Krasny-Pacini et al., 2018).

Many types of EF intervention are reported in the literature: computerized training, non-computer games, physical activities, classroom curricula, art activities, mindfulness practices, and biofeedback. Computer-based programs, such as CogMed Working Memory Training (www.cogmed.com) and Braingame Brian (Prins et al., 2013), are among the most popular interventions used for the improvement of working memory and for the enhancement of inhibition and cognitive flexibility respectively. Evidence shows that although these treatments have a solid effect in improving the practiced skills, such as inhibition and working memory span (Beck et al., 2010; Chacko et al., 2014; Di Lieto et al., 2021; Gibson et al., 2011; Kidokoro et al., 2014; Klingberg et al., 2005; Løhaugen et al., 2011; Lundqvist et al., 2010; Melby-Lervåg et al., 2016), the improvements do not seem to transfer to untrained domains (Blair & Razza, 2007; Diamond, 2012; Diamond & Lee, 2011; Diamond & Ling, 2016), nor to untrained EF skills (Kassai et al., 2019), nor to everyday life contexts if the intervention is not included in these scenarios (Blair, 2017). The efficacy of EF treatments through physical activities (Best & Miller, 2010; Ng et al., 2017; Tomporowski et al., 2008) and non-computerized games (Tominey & McClelland, 2011) has also been demonstrated. The effectiveness of these interventions could depend on the activation of strategies and cognitive skills related to EFs. Furthermore, complex motor activity activates brain regions related to the prefrontal cortex which may produce immediate physiological responses (increased blood flow, oxygen and brain derived neurotrophic factor-BDNF) which in turn facilitate cognitive performance and learning (Best & Miller, 2010). The presence of cognitive challenges within physical activities requiring flexible adaptation of behaviour seems to produce greater effects on EFs than physical activities involving only aerobic components or automated motor responses (Best & Miller, 2010; Diamond, 2015). Other promising treatment approaches are classroom curricula specifically designed to promote EFs, such as Tools of the Mind (Bodrova & Leong, 2006). These approaches are inserted in the daily practice of children, facilitating the generalization of the skills learned and their application in new contexts. Furthermore, these programs do not require any specific materials, can be conducted in school by teachers and can include a large number of participants (Diamond & Lee, 2011). Not only specific curricula design to promote EF, but also some academic discipline as art activities (Diamond, 2012; Diamond & Lee, 2011; Diamond & Ling, 2016), such as music and drama, requiring inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility are able to produce benefits in EF skills (Schellenberg, 2004; Thibodeau et al., 2016). Another approach to foster children’s EFs is providing them with strategies of self-regulation, both through teaching skills targeting metacognitive intervention, useful for daily life challenges, and through mindfulness practises. This latter activity requires attention (Zelazo & Lyons, 2012) and self-control, reducing anxiety and stress, in the meanwhile, working both on a cognitive and emotional level (Zenner et al., 2014).

Finally, also biofeedback, a technique that uses the electroencephalographic (EEG) or electromyographic (EMG) signal for learning voluntary self-control of some psychophysiological processes that are usually involuntary, are effective on attention and self-regulation, fostering self-teaching strategies to control physiological reactions (Niv, 2013). Neurofeedback training has also been reported to be effective in reducing clinical symptoms in children and adolescents with ADHD (Arns et al., 2009). However, a more recent meta-analysis highlighted the lack of efficacy of neurofeedback treatment tested by standardized tests on EFs in ADHD children (Louthrenoo et al., 2022). This inconsistency in the literature evidence could be due to the different outcome measures considered.

Despite the wide amount of data supporting the usefulness of EF training, the characteristics that make an EF intervention effective are not fully understood. The review by Diamond and Ling (2016) highlights that interventions involving socio-emotional components and physical exercise have the greatest effectiveness, as long as cognitive challenges are included within the proposed activities. Moreover, the exercises must be calibrated on the subject's abilities, as to represent a challenge rather than only skill practice. Other variables influencing the success of the training are the personal characteristics of the person conducting the program and the starting impairment level of the participants, as it seems that greater benefits are observed in conditions of greater initial EF impairment. Furthermore, Blair (2017) emphasizes the importance of placing the intervention within an everyday life context in order to increase ecological validity and generalization. However, interventions on EFs must not become a burden for the family system, already challenged by child’s difficulties, but have to involve the caregivers in an appealing way, favouring skills acquisition useful to support daily life functioning (Krasny-Pacini et al., 2018).

Since EFs are highly correlated with other cognitive functions, their impairment can determine cascade effects on other neuropsychological processes. For this reason, EF improvements could produce effects on functions untrained but correlated with EFs, resulting in important benefits for children's daily functioning. These non-specific effects have been defined by the literature as far-transfer effects, i.e. effects of training on different processes correlated with practiced skills (Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013; Sala & Gobet, 2016, 2017), as opposed to near transfers, i.e. post-treatment improvements in tasks that require directly trained processes (Kassai et al., 2019; Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013; Sala & Gobet, 2016, 2017). Transfer has been defined not only in terms of improvements in different tasks, but also in terms of improvement along time intervals and contextual similarity, and in each of these dimensions the transfer can be near or far (Klahr & Chen, 2011). Linked to the conceptualization of transfer in terms of context dimension, Diamond and Ling (2016) analysed the narrow transfers, i.e., improvements of the abilities trained within the treatment but in other contexts where the same skills are required. The authors argue that “people improve on the skills they practice and that transfers to other contexts where those same skills are needed […]; improvement does not seem to transfer to other skills" (Diamond e Ling in Novick et al., 2020, pages 460–461). The question about the possibility of producing far transfer after EF training is still open, as pointed out by the review by Katz and Saha (2020) on children with developmental disorders (see Novick et al., 2020). Katz and Saha analysed many studies, showing the heterogeneity of results (Chooi & Thompson, 2012; Heinzel et al., 2014; Jaeggi et al., 2014; Kundu et al., 2013; Redick et al., 2013; Stephenson & Halpern, 2013; Thompson et al., 2013), varying from the absence of transfer effects (Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013) to significant effects on skills far from those trained, as fluid intelligence (Au et al., 2015; Karbach & Verhaeghen, 2014). In order to disambiguate the question, it is necessary to develop and use dynamic outcome measures able to detect the effective EFs improvement after a treatment, as well as transfer effects on other processes, taking into account the ecological validity and the test–retest effect (Krasny-Pacini et al., 2018).

The present systematic review aims to investigate the presence of far-transfer effects following executive function training, limiting the analysis to children with neurodevelopmental disorders and considering as far-transfer effects any skill not directly trained by the treatment and assessed post intervention, also including executive functions, if different from those enhanced.

Method

Search Strategy

The review authors undertook a comprehensive search of databases as MEDLINE Advanced PsycINFO, EMBASE, CINHAL and CENTRAL (Cochrane Controlled Registered Trials) in April 2020, in accordance with the PRISMA statement (Moher et al., 2009). The search strategy comprised keywords in different combinations referring to four main clusters: “executive functions'', “neurodevelopmental disorders'', “children” “intervention” and “far effects'' including terms related to constructs and definitions (see Appendix 1 for complete search string and the Introduction for the definition of the specific terms). The keywords were selected based on the analysis of the literature on the effect of training in neurodevelopmental disorders (Kassai et al., 2019; Diamond e Ling in Novick et al., 2020; Scionti et al., 2020; Takacs & Kassai, 2019). The selection of terms referring to executive functions was guided by the models suggested by Diamond (2013) and Miyake et al. (2000). The latter one also includes emotional aspects such as emotion regulation and “hot” EF, which are considered also in this review as part of executive functions. Given the recent increased interest in studying the effects of EF training in children, the research was restricted to the period 2000–2020. In order to exclude non-peer reviewed studies, the authors included studies published in academic journals, reported in English and available for full text. The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed according to the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Evidence Hierarchy (NHMRC, 2009).

Inclusion Criteria

Type of Participants

Published studies included samples of subjects in developmental age (5–18 years) diagnosed with Neurodevelopmental Disorders (according to ICD 11 or 10 or DSM 5 or IV TR) They included Learning Disorders, Developmental Coordination Disorder, Language Disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Intellectual Disabilities (or as defined by the ICD or DSM IV). The choice of age range was guided by evidence described above that EFs develop from the first year of life to late adolescence, with a peak of development during the first 5 years of life (Garon et al., 2008). Furthermore, it is possible that for some neurodevelopmental disorders a clear diagnosis cannot be formulated before the age of five, thus, it is from the end of the preschool ages that eventual alterations in EFs are expected, and in turn, interventions are needed.

Type of Interventions

Selected studies focused on interventions aimed at improving any process belonging to the executive function domain (i.e., inhibition, working memory, shifting, planning, organization, problem solving, decision making, cognitive control, effortful control, self-regulation). Intervention could begin at any time during childhood, and it could have been carried out either in an ecological context, such as home or school, or in an experimental context, such as a laboratory. The intervention had to be carried out by health professionals (such as psychologists, neuropsychiatrists or occupational therapists) or by education professionals (such as teachers or educators). Types of interventions could include any program assumed to work on EFs, such as neurocognitive stimulation, neurocognitive training, computer programs, scholastic and academic curricula, occupational therapy, neuropsychological rehabilitation, psychoeducation, mindfulness and physical activities. Any frequency, intensity and duration of training was included. Moreover, the studies included needed to have a pre-post treatment design or the presence of a control group (active or waitlist).

Type of Outcomes

To be selected, studies must have measured far effect outcomes at the completion of the intervention.

The outcome variables had to be measured with standardized, objective tests administered to the child (either commercial or prototypal/experimental) and with parent’s and self-report questionnaires. These far effect measures included standardized neuropsychological and cognitive tests, achievement tests (math or reading or writing), quality of life questionnaires, self-regulation questionnaires, teachers’ ratings (school readiness, general literacy skills, or math or reading or writing), report cards (literacy or math or reading or writing).

Studies were excluded if: (1) they included single case studies and reviews; (2) they were diagnostic or prognostic studies (2) participants’ age was > 18 or < 5 or not clearly defined; (3) they included participants with other medical, psychiatric or neurological conditions not included in the classification of neurodevelopmental disorders, (4) the training was not targeted on cognitive or neuropsychological domains, (5) there was no control group, (6) there were no far effect outcome measures.

Study Selection Process

The initial literature searches produced 1683 papers. Five of these studies were included by analysing the articles’ bibliography. After removing duplicates, 508 articles were reviewed independently by three authors (Clara Bombonato (CB), Benedetta Del Lucchese (BDL), and Costanza Ruffini (CR)) on the basis of the title and abstract with an inter-rater agreement of 100%. 143 full-text articles were selected and reviewed to identify those that met the inclusion criteria. When discrepancy arose, articles were discussed and re-reviewed to determine their inclusion or exclusion. The process led to the selection of 17 papers that met the inclusion criteria. The overall process for selecting studies is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study selection process following the PRISMA 2009 flow diagram

Meta-analysis

Far effect outcome measures of reviewed studies including control groups were analyzed. The data collected from the articles were analyzed using software R, version 4.1.2. All of the studies included different outcomes, divided and analyzed on the basis of 5 macro categories considered as far effects, ;detailed in paragraph 3.5. A multivariate random-effect linear model, making use of Hedges Estimator, was used to conduct a meta-analysis. Hedge's g values were calculated and, ;according to Cohen (Cohen, 1977), values of effect sizes between 0.2 and 0.5 were considered "small", between 0.5 and 0.8 "medium", and > 0.8 "large". Effect size estimates were pooled across studies to obtain an overall effect size.

Results

Seventeen studies were eligible for inclusion. The methodological quality of the included studies was independently assessed by the reviewers according to the National Health and Research Council (NHMRC). All studies were classified at level II, as Randomized Control Trials (Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; Bowling et al., 2017; Chacko et al., 2014; de Vries et al., 2015; Dovis et al., 2015; Egeland et al., 2013; Esmaili et al., 2019; Kenworthy et al., 2014; Kirk et al., 2016, 2017; Klingberg et al., 2005; Leins et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2020; Strehl et al., 2017; Weiss et al., 2018), except one that was classified at level III-1, as Pseudorandomized Control Trial (Beck et al., 2010).

Participants

Studies including children with neurodevelopmental disorders as the target population of the intervention were selected. In particular, samples were composed by children with Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity (ADHD) in ten studies (Beck et al., 2010; Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; Chacko et al., 2014; Dovis et al., 2015; Egeland et al., 2013; Klingberg et al., 2005; Leins et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2020; Strehl et al., 2017), children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in three studies, (de Vries et al., 2015; Kenworthy et al., 2014; Weiss et al., 2018), children with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (ID) in two studies (Kirk et al., 2016, 2017) and children with Specific Learning Disabilities in one study (SLD) (Esmaili et al., 2019). Moreover, it was agreed to include one study that targets children with Behavioral Health Disorders (BHD) (Bowling et al., 2017), since, although not present in the main diagnostic classifications (DSM-5; ICD-10), a broad category including some of the neurodevelopmental disorders mentioned above (ASD, ADHD). The studies also varied in terms of the age range of the population (4–17 years) and sample size (50 to 150 subjects).

Study Design

Regarding the study design, in fifteen studies, the population was divided into two groups. In five of these studies, the control group underwent a training equivalent to that of the experimental group but non-adaptive, therefore without the adjustment for difficulty (Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; Chacko et al., 2014; Kirk et al., 2016, 2017; Klingberg et al., 2005), in four studies the control group consisted in the waitlist (Beck et al., 2010; Bowling et al., 2017; Esmaili et al., 2019; Weiss et al., 2018), in three studies the experimental group’s performance was compared with that of an active control group following an intervention not focused on EFs. Kenworthy et al., 2014; Leins et al., 2007; Strehl et al., 2017), and in two studies the control group received treatment as usual (Egeland et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2020). In two studies, the population was divided into three groups: two experimental groups and one control group, which underwent non-adaptive training (de Vries et al., 2015; Dovis et al., 2015).

Intervention

All the selected articles provided results about an intervention aimed at executive functions rehabilitation. Such treatments were undertaken in several ways. Specifically, most of the interventions included computer training activities (Beck et al., 2010; Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; Chacko et al., 2014; de Vries et al., 2015; Dovis et al., 2015; Egeland et al., 2013; Kirk et al., 2016, 2017; Klingberg et al., 2005); in addition, among the selected articles there were two neurofeedback treatments (Leins et al., 2007; Strehl et al., 2017), two curriculum interventions delivered during school attendance (Kenworthy et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2020), an individualized manualized Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) intervention (Weiss et al., 2018), a training delivered through cooperative and collaborative group play activities at the clinic (Esmaili et al., 2019) and finally an intervention based on physical activity (Bowling et al., 2017).

In most studies, the intervention targeted cold components of executive functions, specifically working memory (Beck et al., 2010; Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; Chacko et al., 2014; de Vries et al., 2015; Dovis et al., 2015; Egeland et al., 2013; Esmaili et al., 2019; Klingberg et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2020), inhibition (Dovis et al., 2015; Esmaili et al., 2019; Leins et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2020) and attentional control Kirk et al., 2016, 2017; Leins et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2020), while others aimed at strengthening other executive functions such as planning, problem-solving, shifting, monitoring and cognitive flexibility (de Vries et al., 2015; Dovis et al., 2015; Esmaili et al., 2019; Kenworthy et al., 2014). Four studies targeted the hot components of executive functions, in particular self-regulation and emotional regulation, as intended by the Miyake et al. model (2000) (Bowling et al., 2017; Esmaili et al., 2019; Strehl et al., 2017; Weiss et al., 2018).

These interventions were carried out in different settings; at home in ten studies (Beck et al., 2010; Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; Chacko et al., 2014; de Vries et al., 2015; Dovis et al., 2015; Kirk et al., 2016, 2017; Klingberg et al., 2005; Weiss et al., 2018), at school in five studies (Bowling et al., 2017; Egeland et al., 2013; Kenworthy et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2020; Weiss et al., 2018) and at the clinic in three studies (Esmaili et al., 2019; Leins et al., 2007; Strehl et al., 2017).

The duration of the interventions ranged from 5 weeks to 3 months; only one study involved a treatment in which the 28 sessions were spread over a year (Kenworthy et al., 2014).

The intensity of the intervention varied from 2 times a week to daily, twice a week in three studies (Bowling et al., 2017; Esmaili et al., 2019; Strehl et al., 2017), 3–4 times a week in one study (. Smith et al., 2020), 5 times a week in seven studies (Bigorra et al., 2016a; Chacko et al., 2014; Kirk et al., 2016, 2017; Klingberg et al., 2005; Leins et al., 2007). In one study, frequency of intervention corresponded to the total days of school attendance (Egeland et al., 2013). Of the articles examined, five studies did not report the frequency of intervention but the overall duration of the intervention: 6 weeks (de Vries et al., 2015), 10–14 weeks (Weiss et al., 2018), 28 sessions (Kenworthy et al., 2014), 25 sessions over 5–6 weeks (Beck et al., 2010) and the last one, 25 sessions over 5 weeks (Dovis et al., 2015). The duration of each single treatment session ranged from 20 min to 2 h.

Far Effect Outcomes

According to the research questions of the studies, different far effects were measured. However, it was possible to outline some common aspects that had been investigated, regardless of the type and target of the author's intervention. Most of the authors investigated whether, as a consequence of training on specific executive functions, improvements were obtained on other executive functions not directly trained. For example, Bigorra and colleagues (2016a, b) conducted two interventions on working memory and explored the far effect on inhibition, sustained attention, planning, cognitive flexibility, task switching (study 1) and decision making (study 2). De Vries and colleagues (2015) explored inhibition, sustained attention, working memory or cognitive flexibility and their intervention was directed to working memory or cognitive flexibility. Dovis and colleagues (2015) led a training on visuospatial working memory, inhibition and cognitive flexibility and studied the far effect on interference control, verbal short-term memory/working memory and complex reasoning. For Egeland and colleagues (2013) working memory was the target intervention and processing speed, attention, inhibitory control were assessed as far effects. Klingberg and colleagues (2005) implemented a working memory training and studied inhibition as a far effect. All these studies implemented neuropsychological outcome measures. Finally, Kirk and colleagues’ (2017) intervention target was attentional control and response inhibition while Beck and colleagues’ (2010) was working memory and both studies investigated parent and teacher-report child daily executive functioning as outcome measures.

Another common target of investigation was the study of any changes, following the training, in the disorder’s specific symptomatology: ADHD symptoms (Beck et al., 2010; Bigorra et al. 2016a, b; Chacko et al., 2014; de Vries et al., 2015; Dovis et al., 2015; Egeland et al., 2013; Kirk et al., 2016; Klingberg et al., 2005; Leins et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2020; Strehl et al., 2017), autism symptoms ( Kenworthy et al., 2014), mood (Weiss et al., 2018) referred by parents and teachers or by the clinician (Smith et al., 2020; Strehl et al., 2017; Weiss et al., 2018).

The majority of studies assessed the child’s daily life functioning, including adaptive behaviour (Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; Dovis et al., 2015; Egeland et al., 2013; Kirk et al., 2017; Leins et al., 2007; Strehl et al., 2017; Weiss et al., 2018), quality of life (de Vries et al., 2015; Dovis et al., 2015; Esmaili et al., 2019; Strehl et al., 2017), classroom functioning (Bowling et al., 2017; Kenworthy et al., 2014), and social skills (Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; de Vries et al., 2015).

A recurring aspect that was investigated with direct outcome measures was the child’s learning skills such as reading comprehension (Bigorra et al., 2016a, b), math, vocabulary, letter knowledge and rhyme detection (Kirk et al., 2017), reading and math (Egeland et al., 2013), word reading, sentence comprehension, spelling, and mathematical computation (Chacko et al., 2014).

Finally, a few studies explored other cognitive outcomes as far effect: memory (Egeland et al., 2013), complex non-verbal reasoning (Dovis et al., 2015; Klingberg et al., 2005; Strehl et al., 2017) and intelligence (Leins et al., 2007).

Efficacy on Far Effects

Results will be presented dividing the selected articles according to the EF component target of the intervention. Within each section, the studies will be reported analyzing the far effects investigated, which are categorized into 5 macro categories, agreed upon by the authors of this systematic review. These macro-categories grouped the different outcomes assessed as far effects (other executive functions, clinical symptoms, learning skills, daily life functioning and cognitive outcomes).

Intervention on Attentional Control and Inhibition

KIRK et al. (2016), Kirk et al. (2017), Leins et al. (2007) analysed the effects of interventions targeting attention and inhibition (Table 1).

Table 1.

Studies implementing interventions on attentional control and inhibition

| Authors | Study design | Diagnosis | Population | Age | Intervention | Target of intervention | Duration | Intensity | Assessment of near effect | Assessment of far effect | Near effects | Far effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kirk et al. (2017) | RCT | ID | EG n = 38, CG n = 37 (non-adaptive training) | 4–11 yrs | Training Attention and Learning Initiative (TALI): computer training at home | Selective attention, sustained attention, attentional control (conflict resolution; response inhibition) | 5 wks (25 sessions) | 20 min per day, 5 times a week | Not investigated |

Learning skills: GAN, TEMA-3, PPVT-4, PAT (letter knowledge and rhyme detection subscales) Other executive Functions: BRIEF, WMRS Daily life functioning: DBC-P |

- |

Yes, on mathematical learning skills (TEMA) at 3 months follow-up No other learning skills, executive functions non-trained and daily life functioning |

| Kirk et al. (2016) | RCT | ID | EG n = 38, CG n = 37 (non-adaptive training) | 4–11 yrs | Training Attention and Learning Initiative (TALI): computer training at home | Selective attention, Sustained attention, attentional control (conflict resolution; response inhibition) | 5 wks (25 sessions) | 20 min per day, 5 times a week, | Selective attention, attentional control and sustained attention: WATT (visual search task; sustained attention task) | Clinical Symptoms: SWAN |

Yes, on selective attention (Number of errors) No on attentional control, selective attention (time) and sustained attention |

No significant treatment effect found |

| Leins et al. (2007) | RCT | ADHD | EG1 (SCP) n = 19, EG2 (Theta/beta) n = 19 | 8–13 yrs | Neurofeedback in clinic | Attention, inhibition | 2 wks (10 sessions) for three treatment phases with a break of 4 to 6 weeks between each phase | 1 h per session | Attention: TAP |

Clinical symptoms: DSM-IV—questionnaires for parents and teachers, Conners’ Rating Scale Daily life functioning: ECBI Cognitive outcomes: HAWIK-III; |

Yes, on attention for both EGs | No differences between EG on clinical symptoms (Conners’ Rating Scale, DSM IV questionnaires), on daily life functioning (ECBI) and on Cognitive outcomes (HAWIK-III). At post hoc analysis significant improvement only for EG 2 on cognitive outcomes and on clinical symptoms |

Legend: RCT Randomized Controlled Trial, ID Intellectual Disability, ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, EG Experimental Group, CG Control Gropu, DSM IV Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders, WATT Wilding attention battery, TAP Testbatterie zur Aufmerksamkeitsprufung, GAN Give A Number, TEMA Test of Early Mathematics Ability, PPVT-4 Peabody Picture Vocabulary Task-4, PAT Phonological Abilities Test, BRIEF Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions, WMRS Working Memory Rating Scale, DBC-P Developmental Behavior Checklist Parent, SWAN Strengths and Weaknesses of ADHD symptoms and Normal behavior scale, ECBI Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory, HAWIK III The Hamburg-Wechsler intelligenztest fur Kinder

One study ( Kirk et al., 2017) evaluated improvement of executive functions in daily life with parent and teacher report questionnaires, finding no significant far effect of the computerized attentional training on children with intellectual disability.

Two studies evaluated a reduction of ADHD symptomatology (rating scales) as a far effect of the interventions. Kirk et al. (2016) found no significant effects of the computerized attentional training in children with intellectual and developmental disabilities, while Leins et al. (2007), in children with ADHD found a significant reduction in symptoms after neurofeedback interventions in the two experimental groups, but in absence of a control group and without observing specific differences between the two types of treatment.

Only Kirk et al. (2017) considered the improvement in learning skills (defined as both academic skills and as abilities supporting learning) as a far effect, finding significant effects only for mathematic skills at the three-month follow-up, while no effects were found in cognitive skills underlying school learning, such as the receptive vocabulary and metaphonological skills neither at the post-test nor at the follow-up assessment.

The two studies, which evaluated children’s daily life functioning through parent report questionnaires, did not find significant effects, neither in terms of improvement of behavioural and emotional problems ( Kirk et al., 2017), nor of behavioural problems at home (Leins et al., 2007).

Leins et al. (2007) evaluated cognitive functioning (German intelligence test for children) as a far effect of the intervention, finding a significant increase in both neurofeedback intervention groups; however, these results were not compared with any control group.

Intervention on Working Memory

Seven of the studies (Beck et al., 2010; Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; Chacko et al., 2014; de Vries et al., 2015; Egeland et al., 2013; Klingberg et al., 2005) analysed the effects of interventions targeting working memory (Table 2).

Table 2.

Studies implementing interventions on working memory

| Authors | Study design | Diagnosis | Population | Age | Intervention | Target of intervention | Duration | Intensity | Assessment of near effect | Assessment of far effect | Near effects | Far effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bigorra et al. (2016a) | RCT | combined-type ADHD | EG n = 36, CG (non-adaptive CogMed training) n = 30 | 7–12 yrs | CogMed computer training at home | Spatial and verbal WM | 5 wks | 5 sessions for week |

WM: WISC IV (Digit Span Backward, letter-Number Sequencing), WMS-III (Spatial span backward) BRIEF (WM subscale) |

Other Executive functions: BRIEF, CPT II, ToL, WCST-64 and TMT B Clinical symptoms: Conners' rating scales-revised, CBCL/4–18, TRF/4–18 Daily life functioning: SDQ, WFIRS-P Learning skills: Canals |

Yes, on BRIEF WM subscale and on a WM composite score |

Yes, on other executive functions (BRIEF, CPT), clinical symptoms (composite score) and daily life functioning (school learning behavior at WFIRS-P, only at follow-up) No on learning skills |

| Bigorra et al. (2016b) | RCT | combined-type ADHD | EG n = 36, CG (non-adaptive CogMed training) n = 30 | 7–12 yrs | CogMed computer training at home | Spatial and verbal WM | 5 wks | 5 sessions for weeks | WM: WISC IV (Digit Span Backward, Letter-Number Sequencing), WMS-III (Spatial span backward) |

Daily life functioning: Happè’s Strange Stories, Folk Psychology Test Other Executive function: IGT |

Yes, the results are reported in the previous article (Bigorra et al., 2016a, 2016b) | No significant treatment effects found |

| De Vries et al. (2015) | RCT | ASD | EG1 (WMtr) n = 40, EG2 (FLEXtr) n = 37, CG (non-adaptive mock training) n = 38 | 8–12 yrs | Braingame Brian: computer training at home | EG1: 5 WM activities with increasing difficulties (remembering, manipulating and updating). EG2: One Cognitive Flexibility activity with increasing difficulty | 6 wks (25 sessions) | Not reported | WM: Corsi-BTT (similar to activities' training), N back task (different to activities' training); Cognitive Flexibility: GEWT (similar to activities' training), NGST (different to activities' training) |

Other executive functions: Stop task, SART, BRIEF Daily Life Functioning: CSBQ, PedsQL Clinical symptoms: DBDRS |

No significant differences between groups for working memory and cognitive flexibility | No significant treatment effects found |

| Egeland et al. (2013) | RCT | ADHD | EG (TAU + Cogmed) n = 38, CG (TAU) n = 37 | 10–12 yrs | CogMed computer training at school | Spatial and verbal WM | 5–7 wks | Each school day (30–45 min) | WM: BVRT |

Other executive functions: CW, TMT (D-KEFS), BRIEF, CCPT-II Cognitive outcomes: CAVLT-2 Learning skills: Key Math, LOGOS Clinical symptoms: ARS-IV Daily life functioning: SDQ |

No |

Yes, on reading learning skills No on cognitive outcomes (CAVLT-2), maths learning skills, other executive functions (CW, TMT (D-KEFS), BRIEF, CCPT-II), clinical symptoms (ARS-IV) and daily life functioning (SDQ) |

| Chacko et al. (2014) | RCT | ADHD | EG n = 44, CG (Non adaptive training) n = 41 | 7–11 yrs | Cogmed computer training at home | verbal and non-verbal WM | 25 sessions | Fine days per week (30–45 min) | WM: AWMA |

Clinical symptoms: DBD, actigraphs Learning skills: WRAT4-PMV |

Yes, on WM (non-verbal and verbal storage) but no significant differences between groups on measures of nonverbal or verbal complex working memory (storage plus processing/manipulation) | No significant treatment effects found |

| Klingberg et al. (2005) | RCT | ADHD | EG n = 26, CG (non adaptive WM training) n = 24 | 7–12 yrs | Cogmed computer training at home | Spatial and verbal WM | 5–6 wks (25 sessions) | 40 min per day every day |

Visuo-spatial WM: span-board task Verbal WM: Digit-span (WISC III) |

Clinical symptoms: parent and teacher-report Conners Rating Scale, number of head movements Cognitive outcomes: CPM Other executive functions: Stroop Task |

Yes, on visuo-spatial and verbal WM |

Yes, on other executive functions (Stroop task), cognitive outcomes (CPM) and on parent ratings clinical symptoms No on teacher rating clinical symptoms |

| Beck et al. (2010) | NRS | combined type or inattentive type ADHD | EG n = 27, CG (waitlist) n = 25 | 7–17 yrs | Working Memory Training Program: computer training at home | Spatial and verbal WM | 5–6 wks (25 sessions) | 30–40 min per session | WM: BRIEF (WM subscale) |

Other executive functions: BRIEF (other subscales) Clinical symptoms: P-ChIPS, Conners’ Rating Scale—teacher and parents |

Yes, on WM (for parents at post training and at 4-month follow up, for teachers only at follow up) | Yes, on clinical symptoms (ChIPS, Conners’ Rating Scale) and on other executive functions (BRIEF) |

Legend: RCT Randomized Controlled Trial, ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, ASD Autism Spectrum Disorder, EG Experimental Group, CG Control Gropu, DSM IV Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders, WM Working Memory, WMtr Working memory training, TAU Treatment As Usual, WISC IV Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-IV, WMS III Wechsler Memory Scale-III, BRIEF Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions, Corsi – BTT Corsi Block Tapping Task, GEWT Gender Emotion Switch Task, NGST Number gnome switch task, BVRT Benton Visual Retention Test, AWMA The Automatic Working Memory Assessment, CCPT-II Conners’ Continuous Performance Test-II, TOL Tower of London, WSCT Wisconsin Card Sorting Test, TMT – B Trail Making Test, CBCL Child Behaviour Checklist, TRF Teacher’s report Form/4-18, SDQ Strenght and Difficulties Questionnaire, WFIRS Weiss Functional Impairment rating scale for parents, IGT Iowa Gambling Task, SART Sustained attention response task, CSBQ Children's Social Behavior Questionnaire, PedsQL The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory, DBDRS parent version of the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale, CW Color Word, DKEFS Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System, CAVLT-2 Children’s Auditory Verbal Learning Tests-2, ARS ADHD Rating Scale, WRAT4-PMV Wide Range Achievement Test 4 Progress Monitoring Version, CPM Colour Progressive Matrices, ChIPS Children’s Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes–Parent Form

Among the six studies that included other executive functions, assessed with neuropsychological measures, as far effects of the intervention in children with ADHD, three found significant effects on response inhibition (Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; Egeland et al., 2013; Klingberg et al., 2005), one on sustained attention (Bigorra et al., 2016a, b), and one on cognitive flexibility (Egeland et al., 2013). On the contrary, Bigorra et al. (2016b) found no significant effects in improving decision making and De Vries et al. (2015) found no significant effects on sustained attention, inhibition, and cognitive flexibility in children with ASD. Some studies assessed far effects on other executive functions by means of parent or teacher report questionnaires (BRIEF), finding significant effects (Beck et al., 2010; Bigorra et al., 2016a, b) indicating an improvement on executive functions in ecological settings. On the other hand, Egeland et al. (2013) and De Vries et al. (2015) reported no significant effect of the intervention in increasing executive functioning in daily life.

Among the six studies that included the reduction of clinical symptoms, measured with teacher or parent-report, as a far effect of working memory interventions, three studies found a significant reduction in ADHD-related symptoms in children with this neurodevelopmental disorder (Beck et al., 2010; Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; Klingberg et al., 2005). In contrast, other studies did not find significant effects in reducing ADHD-clinical symptoms neither in children with ADHD (Chacko et al., 2014; Egeland et al., 2013) nor in children with ASD (de Vries et al., 2015). Furthermore, when ADHD symptomatology was assessed with direct measures, as attention, activity level and impulse control measured by actigraphs (Chacko et al., 2014) and by the number of head movements measured by an infrared camera (Klingberg et al., 2005), no significant far effects were reported.

Among the three studies that evaluated the improvement of learning skills as a far effect of the intervention, only Egeland et al. (2013) found significant effects in improving speed and accuracy of reading. No significant effects were found in improving reading comprehension (Bigorra et al., 2016a, b), math skills (Egeland et al., 2013), word reading, sentence comprehension, spelling, and mathematical computation (Chacko et al., 2014).

Among the four studies that evaluated functioning in daily life (behaviour, social skills, quality of life), only Bigorra et al., (2016a, b) found a significant effect in improving school learning behaviour (i.e. need for an extra help at school, grades that are below potential), assessed through a parent report questionnaire, while no significant effects were found in improving behavioural and emotional skills (Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; Egeland et al., 2013), social skills (de Vries et al., 2015) or quality of life (de Vries et al., 2015). Finally, a direct test assessing of theory of mind skills (Bigorra et al., 2016a, b) did not yield any improvement.

In the two studies that considered an improvement in cognitive processes as a far effect of the intervention, Klingberg et al. (2005) found a significant effect in improving non-verbal reasoning abilities (Raven’s Matrices), while Egeland et al. (2013) found no significant effects on auditory long-term memory (word recall and recognition).

Intervention on Cognitive Flexibility

Only one of the studies included in this systematic review analysed the effects of a treatment aimed at improving cognitive flexibility (de Vries et al., 2015) (Table 3). No significant far effects were reported for children with ASD: neither on other executive functions assessed through questionnaires and standardized tests, nor on clinical symptoms, daily life functioning, or on quality of life.

Table 3.

Studies implementing intervention on cognitive flexibility

| Authors | Study design | Diagnosis | Population | Age | Intervention | Target of intervention | Duration | Intensity | Assessment of near effect | Assessment of far effect | Near effects | Far effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Vries et al. (2015) | RCT | ASD | EG1 (WMtr) n = 40, EG2 (FLEXtr) n = 37, CG (non-adaptive mock training) n = 38 | 8–12 yrs | Braingame Brian: computer training at home | EG1: 5 WM activities with increasing difficulties (remembering, manipulating and updating). EG2: One Cognitive Flexibility activity with increasing difficulty | 6 wks (25 sessions) | Not reported | WM: Corsi-BTT (similar to activities' training), N back task (different to activities' training); Cognitive Flexibility: GEWT (similar to activities' training), NGST (different to activities' training) |

Other executive functions: Stop task, SART, BRIEF Daily Life Functioning: CSBQ, PedsQL Clinical symptoms: DBDRS |

No significant differences between groups for working memory and cognitive flexibility | No significant treatment effects found |

Legend: RCT Randomized Controlled Trial, ASD Autism Spectrum Disorder, EG Experimental Group, CG Control Group, DSM IV, WM Working Memory, WMtr Working memory training, FLEXtr Flexibility training; Corsi – BTT Corsi Block Tapping Task, GEWT Gender Emotion Switch Task, NGST Number gnome switch task, SART Sustained attention response task, BRIEF Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions – parent, CSBQ Children's Social Behavior Questionnaire, PedsQL The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory, DBDRS parent version of the Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale

Intervention on Hot Executive Functions

Three studies (Bowling et al., 2017; Strehl et al., 2017; Weiss et al., 2018) investigated the effects of interventions (physical activity through virtual reality, emotional regulations trainings, neurofeedback) aimed at improving the "hot" component of executive functions on clinical symptomatology, daily life functioning and intelligence in children with different neurodevelopmental disorders (Table 4).

Table 4.

Studies implementing interventions on hot executive functions

| Authors | Study design | Diagnosis | Population | Age | Intervention | Target of intervention | Duration | Intensity | Assessment of near effect | Assessment of far effect | Near effects | Far effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowling et al. (2017) | RCT | BHD (ASD, ADHD, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders) | EG n = 52, CG (waitlist) n = 52 | 7–16 yrs | Manville Moves: VR-cybercycling at school | Self-regulation | 7 wks | 2 sessions per week (30–40 min) | Behavioural self-regulation: CATRS-10 | Daily life functioning: classroom functioning (TOC per days) | Yes | Yes |

| Weiss et al. (2018) | RCT | ASD | EG n = 31, CG (waitlist) n = 29 | 8–12 yrs | Secret Agent Society: Operation Regulation at home and school | Emotional regulation | 10–14 wks | Not reported | Emotional regulation: ERSSQ-P, ERC, CEM, Dylan, James |

Daily life functioning: BASC-2 Clinical symptoms: ADIS-P, CGI-S, BASC-2 |

Yes, on parent report emotional regulation measures No significant group differences on any of the child-reported ER measures |

Yes, on daily life functioning (BASC -2) and clinical symptoms (ADIS-P, CGI-S) Gains maintained at follow-up |

| Strehl et al. (2017) | RCT | ADHD | EG1 (Neurofeedback) n = 76, EG2 (EMG Feedback) n = 74 | 7–9 yrs | Neurofeedback; EMG feedback in clinics | Self-regulation | 3 months (25 sessions with a break after 12 sessions of 4–6 weeks.) | 2–3 sessions per week |

Cortical self-regulation ADHD symptoms: German ADHD rating scale (subscale inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity) |

Clinical symptoms: Parents’ ratings of ADHD subdomains, Teachers’ ratings of ADHD symptoms,CGI-I Daily life functioning: SDQ, Kid-KINDL Cognitive outcomes: CPM |

Yes, EG1 was significantly superior to EMG in reducing ADHD core symptoms |

Yes, there are significant differences between EG groups on clinical symptoms (Parents’ Ratings of ADHD Subdomains on impulsivity and inattention) and on cognitive outcomes (CPM) No, there are not differences between EG groups on clinical symptoms (Teachers’ Ratings of ADHD Core Symptoms and CGI-I) and on daily life functioning (Kid-KINDL,SDQ) |

Legend: RCT Randomized Controlled Trial, ASD Autism Spectrum Disorder, ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, BHD behavioral health disorders, EG Experimental Group, CG Control Group, EMG Electromiography, VR Virtual Reality, CATRS Conner's abbreviated teacher rating scale, ERSSQ-P Emotion Regulation and Social Skills Questionnaire, ERC Emotion Regulation Checklist, CEM Children’s Emotion Management Scales, TOC Time out of class, BASC-2 Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition – Parent Rating Scales, ADIS-P Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule – Parent Version, CGI Clinical Global Impression, SDQ Strenght and Difficulties Questionnaire, Kid-KINDL German quality of life assessment for kids, CPM Colour progressive matrices

Two studies evaluated the improvement of clinical symptoms as a far effect of the intervention. Specifically, Weiss et al., (2018) found significant effects in the improvement of symptomatology related to mood and behavioural disorders through parent report questionnaires and in the global clinical assessment evaluated by clinicians, while Strehl et al. (2017) found significant effects in terms of a decrease of inattention and hyperactivity from the analysis of teacher and parent report questionnaires, while there was no significant effect as expressed by the clinicians Global Clinical Impression (CGI).

All three studies evaluated functioning in daily life as a far effect of the intervention, finding significant effects on classroom functioning (Bowling et al., 2017) and on emotional and behavioural problems perceived by parents (Weiss et al., 2018). Instead, the neurofeedback intervention (Strehl et al., 2017) yielded no significant effects on the reduction of behavioural and emotional impairments assessed by parents and teachers or on the quality of life.

Only Strehl et al. (2017) evaluated cognitive outcomes, finding significant effects in improving non-verbal reasoning (Raven’s Matrices) in the neurofeedback group compared to the electromiography feedback group.

Integrated Intervention on Different EF Components

Four (Dovis et al., 2015; Esmaili et al., 2019; Kenworthy et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2020) of the studies investigated the effects of integrated trainings, that is, interventions simultaneously training different components of executive functions in children with different neurodevelopmental disorders (Table 5).

Table 5.

Studies implementing integrated interventions

| Author | Study design | Diagnosis | Population | Age | Intervention | Target of intervention | Duration | Intensity | Assessment of near effect | Assessment of far effect | Near effects | Far effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esmaili et al. (2019) | RTC | SLD | EG n = 28, CG (waitlist) n = 28 | 7–11 yrs | Peer- activities in groups: cooperative and collaborative plays in clinic | Inhibition, shifting, emotional control, working memory, initiation, planning, organization of materials, and monitoring | 9 wks | 2 sessions per week (3 h) | Executive functions: BRIEF |

Daily life functioning: COSA |

Yes | No significant treatment effects found |

| Kenworthy et al. (2014) | RCT | ASD | EG n = 47, CG (SS intervention) n = 20 | 7–11 yrs | Unstuck and On Target (UOT): curriculum at school | Flexibility, goal-setting, planning, using internalized language to support problem-solving | 1 year (28 sessions for children, 1 session for parents and 1 session for teachers) | 30–40 min |

Problem solving: BD Flexibility and planning: CT Executive Functions: BRIEF |

Clinical symptoms: SRS Daily life functioning: Classroom functioning (Classroom Observations Coding Form) |

Yes on daily life functioning (classroom functioning) No on clinical symptoms |

|

| Smith et al. (2020) | RCT | ADHD | EG n = 48, CG (TAU) n = 44 | 5–9 yrs | Integrated Brain, Body and Social intervention (IBBS) at school |

EF: Sustained attention, response inhibition, working memory, directed attention, attentional switching, divided attention, visual searching, OTHER: category formation, speed of processing, oppositional behavior, disruptive behavior |

15 wks (60 sessions) | In USA: 3–4 days per week (2 h); In China: 3 days per week (90 min) |

Memory and Learning: CVLT, WRAML-2 Interference control: Flanker task |

Clinical symptoms: CGI-I, SNAP |

Yes on memory and learning (CVLT) No significant treatment effect on memory and learning (WRAML-2) and interference control |

No significant treatment effects found |

| Dovis et al. (2015) | RCT | combined-type ADHD | EG1 (full active condition) n = 31, EG2 (partially active condition) n = 28, CG (placebo non adaptive condition) n = 30 | 8–12 yrs | Braingame Brian: computer training at home |

EG1: visuospatial WM, Inhibition and cognitive flexibility EG2: inhibition and cognitive flexibility |

5 wks (25 sessions) |

Not reported (35–50 min per session) |

Visuospatial short-term memory and WM: CBTT Inhibition: Stop Task Cognitive Flexibility: TMT |

Interference control: Stroop Color and Word Test Other executive functions: Digit span, BRIEF Cognitive outcomes: CPM Clinical symptoms: DBDRS Daily life functioning: PedsQL, SPSRQ-C, HSQ |

Yes: EG1 improved on visuospatial short-term memory, WM and inhibition; EG2 improved on inhibition, but not on visuospatial short-term memory and WM |

Yes there are significant differences between EG groups on other executive functions (interference control) No, there are not significant differences between EG groups on other executive functions (Digit Span, BRIEF), cognitive outcomes (CPM), clinical symptoms (DBDRS) and daily life functioning (PedsQL, SPSRQ-C, HSQ) |

Legend: RCT Randomized Controlled Trial, ASD Autism Spectrum Disorder, ADHD Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, SLD Specific Learning Disability, EG Experimental Group, CG Control Group, TAU Treatment As Usual, SS Social Skills intervention, WM Working Memory, BRIEF Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions, BD Block design, CT Challenge Task, CVLT Verbal Learning and Memory, WRAML-2 Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning–Second Edition—visuo spatial memory feed foward and backward, CBTT Corsi Block Tapping Task, TMT Trail Making Test, COSA Child Occupational Self-Assessment, SRS Social Responsiveness Scale, CGI-I The Clinical Global Impression-Improvement, SNAP The Swanson, Nolan and Pelham Teacher and Parent Rating Scale, CPM Colour Progressive Matrices, DBDRS Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale, PedsQL Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory, SPSRQ-C Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire for children, HSQ Home Situations Questionnaire

Dovis et al. (2015) evaluated the improvement in other executive functions than the target ones, in children with ADHD finding no significant effects either in the improvement of verbal working memory evaluated through standardized direct tests, or in executive functioning in the context of daily life evaluated through parent report questionnaires.

Among the three studies that evaluated the reduction of clinical symptoms as a far effect of the intervention, Dovis et al. (2015) found significant effects in ADHD behaviour perceived by teachers, but not by parents, while Smith et al. (2020) found no significant reduction in ADHD symptoms as assessed by clinicians, nor as perceived by parents and teachers in children with ADHD. Finally, Kenworthy et al. (2014) found no significant reduction in ASD symptoms in children with this disorder.

Kenworthy et al. (2014) found ASD after the intervention, assessed by an external blind researcher using observational measures. Instead, Esmaili et al. (2019) in children with specific learning disability, found no significant effects in children’s perceived competence in everyday activities, and Dovis et al. (2015) found no significant effects, in children with ADHD in improving children's motivational behaviours, neither in decreasing problematic behaviours at home and in public situations as assessed by parent report questionnaires nor in quality of life.

Only Dovis et al. (2015) evaluated the improvement of cognitive abilities, finding no significant effects in the improvement of non-verbal reasoning skills (Raven’s Matrices).

Metanalysis Results

Non-trained Executive Functions

All of the 9 studies that assessed a non-trained EF as far effect was included in the metanalysis, considering 87 outcome measures. According to the multivariate random-effect model, overall effect size was statistically significant (p < 0.0001), estimated as 0.18 (95% CI: [0.13, 0.24]) (Fig. 1). Among the studies with a greater effect size (0.52–0.97), two (Beck et al., 2010; Bigorra et al., 2016a, b) assessed non trained EF with an indirect (teacher or parent questionnaires) measure of everyday executive functioning, and two with a direct measure of attentional control (Bigorra et al., 2016a, b) and switching (de Vries et al., 2015) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Metanalysis results of far effect on other executive functions

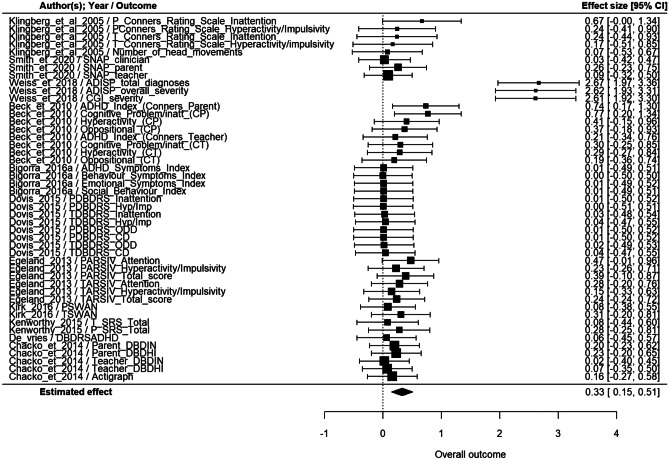

Clinical Symptoms

Among the 13 studies that assessed clinical symptoms as the far effect, only those with a control group were included. For this reason, two studies were excluded (Leins et al., 2007; Strehl et al., 2017). Other measures included in some studies (Smith et al., 2020; Weiss et al., 2018) have been excluded because of zero sample variance. According to the multivariate random-effect model, overall effect size was statistically significant (p < 0.001), estimated as 0.33 (95% CI: [0.15, 0.51]) (Fig. 2). Among the studies with a greater effect size (0.67–2.67), two considered ADHD symptoms (Beck et al., 2010; Klingberg et al., 2005), assessed with standardized questionnaires, while the other one considered ASD symptoms (Weiss et al., 2018) assessed through an interview conducted with parents by clinician and with a blind clinical global impression (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Metanalysis results of far effect on clinical symptoms

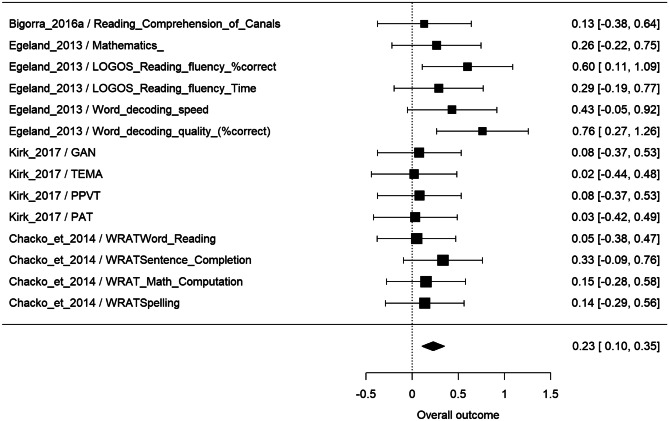

Learning Skills

All of the 4 studies that assessed learning as a far effect were included in the metanalysis, considering 14 outcome measures. According to the multivariate random-effect model, overall effect size was statistically significant (p < 0.001), estimated as 0.23 (95% CI: [0.10, 0.35]) (Fig. 4). The only study that found greater effect sizes (0.60–0.76) evaluated reading accuracy (Egeland et al., 2013) in ADHD children. (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Metanalysis results of far effect on learning skills

Cognitive Outcomes

Among the 5studies that assessed cognitive outcomes as far effects, only those with a control group were included. For this reason, two studies were excluded (Leins et al., 2007; Strehl et al., 2017). According to the multivariate random-effect model, overall effect size was not statistically significant, estimated as 0.18 (95% CI: [-0.05, 0.41]) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Metanalysis results of far effect on cognitive measures

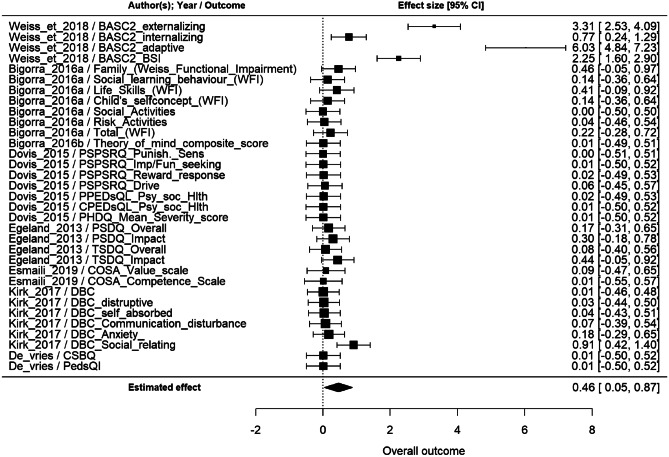

Daily Life Functioning

Among the 10 studies that assessed daily life functioning as far effect, only those with a control group were included. For this reason, two studies were excluded (Leins et al., 2007; Strehl et al., 2017). One study had been excluded because of zero sample variance (Bowling et al., 2017). According to the multivariate random-effect model, overall effect size was statistically significant (p < 0.05), estimated as 0.46 (95% CI: [0.05, 0.87]) (Fig. 6). Among the studies with a greater effect size (0.91–6.03), one (Weiss et al., 2018) investigated behavioural and emotional functioning through a parent report questionnaire in children with ASD, and the other one (Kirk et al., 2017) assessed social functioning in children with intellectual disability.

Fig. 6.

Metanalysis results of far effect on daily life functioning

Discussion

This systematic review was aimed at investigating the far-transfer effects, which are improvements on any skills or behaviour not directly trained, following EF intervention in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. In fact, in neurodevelopmental disorders and in atypical developmental trajectories, EF alterations are a common finding, suggesting that an executive dysfunction is a pervasive and shared outcome among different disorders and a transdiagnostic indicator of atypical development (Zelazo, 2020). Nonetheless, these complex, multi-component functions influence other cognitive abilities and, above all, daily life functioning (Marotta & Varvara, 2013; Marzocchi & Valagussa, 2011; Vicari & Di Vara, 2017). According to Zelazo's iterative reprocessing model (Zelazo, 2015) which defines a continuous reciprocal relationship between EFs and cognitive development, it is highly probable that a bidirectional relationship is frequently triggered between the specific alterations of a certain disorder and those of EFs. Alternatively (Lahey et al., 2017), EFs could represent either a cognitive factor that contributes to the aetiology of the disorder or a causal factor for the emergence of additional symptoms, making the disorder more complex and severe. Therefore, EF intervention should ultimately improve non trained abilities as well as induce positive cascade effects on development.

Among the different definitions of far transfer (Diamond & Ling, 2016; Klahr & Chen, 2011), for the purpose of this review all the skills not directly involved in the EF intervention and assessed post-intervention have been considered (Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013; Sala & Gobet, 2016, 2017). This conceptualization is in line with the one proposed by Borella and Carretti (Borella & Carretti, 2020), who define as "near transfer" the improvement in the trained skill measured with different tests and "far transfer" the effective generalization of the training effects to tests that detect skills or processes other than those trained. This conceptualization was also used to include articles that did not refer explicitly to "far effect" or "far transfer" in order to provide a more comprehensive overview with respect to the cross-functional effects of interventions on EFs among neurodevelopmental disorders. This approach was used to weigh the impact that improvements in executive functioning have on symptoms or weaknesses characterizing a specific developmental disorder.

According to the Prisma method, out of 1683 studies, only 17 studies met the inclusion criteria. All the studies included, except one (Beck et al., 2010), were randomized control trials, where at least one experimental group and one control group were involved, supporting the quality of the studies according to the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Evidence Hierarchy (NHMRC, 2009). Among these, 10 studies reported an improvement right after the intervention in at least one outcome that can be considered as a far effect following an EF treatment.

The results can be summarized by subdividing them according to the main EF components targeted by the interventions.

Among the three studies on attentional control and inhibition only one study demonstrated at least one far effect (Kirk et al., 2017). With regard to the interventions on working memory, four out of seven studies proved to be effective in producing at least one far effect (Beck et al., 2010; Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; Egeland et al., 2013; Klingberg et al., 2005), while the only study on cognitive flexibility intervention did not show any far effect. Thus, interventions on cold EFs show high variability on the results: although there is a prevalence of far effects in studies of working memory training, one should note that these prevail in number with respect to those training other EF components. Such a prevalence could be due in part to the exponential increase of interventions on working memory implemented through computerized trainings, that also payed attention to measuring far effects. In contrast, all the three studies on hot executive function intervention reported at least one far effect (Bowling et al., 2017; Strehl et al., 2017; Weiss et al., 2018). Finally, among the four studies on integrated interventions on different EF components, two reported at least one far effect (Dovis et al., 2015; Kenworthy et al., 2014).

Albeit few in number, interventions on “hot” components of EFs seem promising, probably since the target of the intervention, that is emotional-behavioural self-regulation, appears to be more transversal to a wide range of skills and processes.

With regards to the intervention population, the majority of the studies involved children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), followed by children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Intellectual Disability (ID) and Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD). One study conducted an intervention on a population with complex diagnosis, called Behavioural Health Disorders, a mixed category that includes Mood Disorder and ADHD. No studies investigating the far-transfer effects following an EF intervention in children with Developmental Coordination Disorder or with Language Disorder were found. The studies that found at least one far effect were found to be six out of ten for ADHD (Beck et al., 2010; Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; Dovis et al., 2015; Egeland et al., 2013; Klingberg et al., 2005; Strehl et al., 2017), two out of three for ASD ( Kenworthy et al., 2014; Weiss et al., 2018), one out of two in ID ( Kirk et al., 2017), zero out of one in SLD and one out of one in BHD (Bowling et al., 2017). Given the scarce number of studies for each clinical population, conclusive data about the different far effects of EF interventions in different developmental disorders are not obtainable. The preponderance of studies in ADHD might be linked to the hypothesis that EFs are predominantly altered in this neurodevelopmental disorder and extend to different contexts, in part justifying the higher number of far effects respect to other clinical populations.

This review underlines the increasing interest for analysing the impact that intervening on different components of EFs may have on a variety of skills impaired in neurodevelopmental disorders. Thus, such interventions, especially if implemented early on, may indirectly strengthen those functions that become the core deficits or positively shape their developmental trajectories.

As far as the intervention population’s age, all studies targeted school-aged children and three of them expanded the sample to include preschool-aged children. Kirk et al., 2016, 2017; Smith et al., 2020). Among the studies on school-age children, 9 out of 14 found at least one far effect (Beck et al., 2010; Bigorra et al., 2016a, b; Bowling et al., 2017; Dovis et al., 2015; Egeland et al., 2013; Kenworthy et al., 2014; Klingberg et al., 2005; Strehl et al., 2017; Weiss et al., 2018). In the studies including also preschool children, in line with the developmental trajectories of EFs (Lee et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2012; Usai et al., 2014), the proposed interventions targeted the firsts EF component that develops or adopted an integrated intervention perspective, without differentiation of the components, which occurs in later life (Diamond, 2013; Lee et al., 2013; Lehto et al., 2003; Lunt et al., 2012). Among these, only one demonstrated at least one far effect (Kirk et al., 2017).