Abstract

The swine industry across the globe is recently facing a devastating situation imparted by a highly contagious and deadly viral disease, African swine fever. The disease is caused by a DNA virus, the African swine fever virus (ASFV) of the genus Asfivirus. ASFV affects both wild boars and domestic pigs resulting in an acute form of hemorrhagic fever. Since the first report in 1921, the disease remains endemic in some of the African countries. However, the recent occurrence of ASF outbreaks in Asia led to a fresh and formidable challenge to the global swine production industry. Culling of the infected animals along with the implementation of strict sanitary measures remains the only options to control this devastating disease. Efforts to develop an effective and safe vaccine against ASF began as early as in the mid-1960s. Different approaches have been employed for the development of effective ASF vaccines including inactivated vaccines, subunit vaccines, DNA vaccines, virus-vectored vaccines, and live attenuated vaccines (LAVs). Inactivated vaccines are a non-feasible strategy against ASF due to their inability to generate a complete cellular immune response. However genetically engineered vaccines, such as subunit vaccines, DNA vaccines, and virus vector vaccines, represent tailored approaches with minimal adverse effects and enhanced safety profiles. As per the available data, gene deleted LAVs appear to be the most potential vaccine candidates. Currently, a gene deleted LAV (ASFV-G-∆I177L), developed in Vietnam, stands as the sole commercially available vaccine against ASF. The major barrier to the goal of developing an effective vaccine is the critical gaps in the knowledge of ASFV biology and the immune response induced by ASFV infection. The precise contribution of various hosts, vectors, and environmental factors in the virus transmission must also be investigated in depth to unravel the disease epidemiology. In this review, we mainly focus on the recent progress in vaccine development against ASF and the major gaps associated with it.

Keywords: African swine fever, Asfivirus, Vaccines

Introduction

The global demand for livestock products is on the rise and is anticipated to surge by a substantial growth of 70–80% by the year 2050. Yet, a significant portion of this expected growth rate has already been achieved in the Asian region over the past two to three decades [1]. China holds the distinction of being the leading swine producer and consumer of pork products in Asia, contributing to almost half of the global value. However, the emergence of the deadly African swine fever (ASF) disease in recent times has the potential to impede the growth rate achieved in the swine industry. ASF is a highly lethal viral haemorrhagic disease caused by a member of the Asfarviridae family, primarily affecting domestic pigs and Eurasian wild boar. The disease is characterized by an exceptionally elevated mortality rate among the affected animals. Despite its non-zoonotic nature and narrow host range, ASF is a notifiable disease according to the guidelines of the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH), owing to its significant socio-economic impact and the potential for transboundary spread [2]. The disease was initially reported in Kenya and continues to be endemic in various African countries to this day [3, 4]. Shortly following the initial report of ASF, the disease rapidly spread to multiple European countries, including France, Italy, Malta, Belgium, Iberian Peninsula, and Netherlands [5]. While Europe had effectively eradicated ASF in 1995, except for Sardinia, a significant outbreak of ASF emerged in Eastern European regions in 2007. At present, ASF outbreaks have been identified in both Central and Eastern Europe, as well as in Asian countries leading to huge economic losses within the swine industry [6]. In August 2018, it was reported in China for the first time, and subsequently, it spread to another eleven Asian countries quickly [7]. In 2020, the initial ASF outbreak was reported in two Indian states, Assam and Arunachal Pradesh [8]. By 2022, the disease had spread to several more states, including Meghalaya, Mizoram, Manipur, Nagaland, Sikkim, Tripura, Uttar Pradesh, and Kerala. In July 2021, ASFV was re-emerged in America, initially in the Dominican Republic and subsequently spreading to Haiti [9]. According to OIE reports spanning from January 2020 to January 2022, 35 countries/regions reported ASF outbreaks, resulting in significant losses in both domestic swine (1,043,334 animals lost) and wild boar populations (29,970 animals lost) [10].

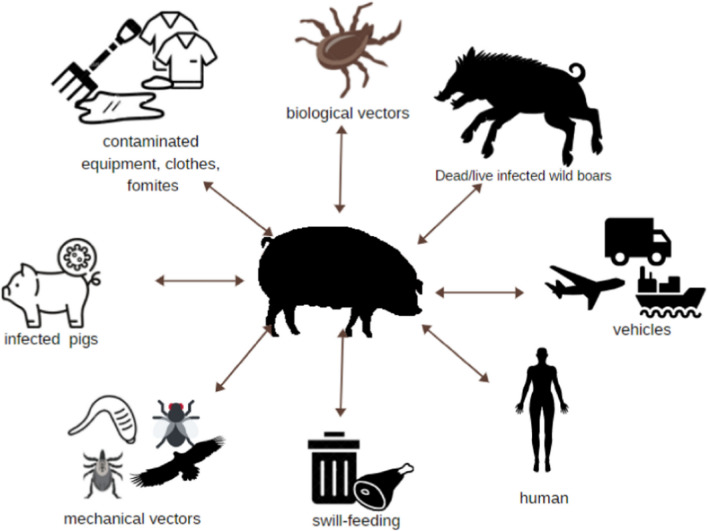

ASFV infects both wild boars and domestic swine, with wild boars like warthogs and bush pigs serving as the natural reservoir in the transmission cycle of the virus [5]. All the age groups of the family Suidae are susceptible to the infection regardless of any report of ASF cases with age predispositions [11]. The only species capable of serving as a competent vector for ASFV are soft ticks belonging to the Ornithodoros complex. An experimental study conducted by Plowright et al. (1974) had demonstrated the possibility of sexual transmission (from infected males to females) of ASFV in Ornithodorus moubata porcinus [12]. However, it can also be transmitted through various means (Fig. 1), including direct contact, consumption of contaminated meat, and indirectly through fomites carrying virus-containing materials such as blood, faeces, urine, or saliva [5]. ASF exhibits four independent epidemiological cycles: (i) the sylvatic cycle, (ii) the tick–pig cycle, (iii) the domestic cycle, and (iv) the wild boar–habitat cycle (a recently identified cycle in Europe) [13]. The sylvatic cycle, primarily restricted to the regions in African continent, is maintained by biological vectors (Ornithodoros ticks) and natural reservoirs (bush pigs and warthogs) without any clinical manifestations in reservoir hosts and is rarely observed in countries like India [14]. In the tick-pig cycle, ticks serve as reservoirs, spreading the virus among domestic pigs and persisting locally in the environment. The establishment of soft ticks in this non-sylvatic biological environment has been facilitated by the dissemination of immature tick phases through migratory birds and changes in climatic conditions. However, in the domestic cycle, the infection spreads among the domestic pigs through the contamination of pig products and reservoir hosts have no role in the transmission [13]. This epidemiological cycle played a critical role in the recent ASF outbreak in India, as the domestic pigs likely contracted the infection from an environment contaminated with ASFV, possibly originating from an imported pig population. The wild boar–habitat cycle has been lately described the Eastern and Central Europe [13]. This cycle elucidates the potential for new infections among the populations of wild boars in previously unaffected regions, including wildlife sanctuaries and national parks.

Fig. 1.

Possible routes of ASFV transmission to pigs.

Adapted from Turlewicz-Podbielska et al. [15] under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

ASF exhibits a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, comprising acute, subacute, chronic, and unapparent forms in domestic pigs while causing mild or persistent infections in warthogs and bush pigs [16]. At present, there is no treatment or sufficient vaccine available for ASF, making control strategies depended solely on surveillance, early disease detection through rapid field monitoring and laboratory diagnosis followed by subsequent enforcement of strict culling and sanitary measures [17, 18]. Given this context, the objective of the current review is to examine recent advancements in the field of ASF vaccine development and address the significant gaps and challenges associated with it.

Aetiology

ASFV belongs to the genus Asfivirus of the family Asfarviridae and shares a close relationship with a novel Asfarvirus (known as Abalone asfa-like virus) within the same family [19]. The virus is enveloped and exhibits icosahedral symmetry, with an average diameter of approximately 200 nm [20]. In its fully mature extracellular form, the ASFV virus particle comprises consecutive layers, commencing with an outer envelope, succeeded by a capsid, an inner envelope, and culminating in a core shell containing the nucleoid [21–23]. Both the mature intracellular and enveloped extracellular forms are infectious, and the genome comprises a linear double-stranded DNA molecule of 170 to 193 kbp in size, encoding approximately 151 to 167 open reading frames (ORFs), depending on the strains [24]. The genome features a central conserved region of around 125 kbp and two variable ends containing five multigene families (MGFs), which are responsible for variations in genome size among different strains [22, 24]. Approximately 17 to 25% of the genome consists of ASFV-encoded MGFs [24, 25]. Based on the sequence analysis of B646L gene, which codes for the major structural protein p72, the ASFV genome is further categorized into 24 distinct genotypes [26]. However, only eight serotypes of the ASFV have been identified based on the C-type lectin and viral haemagglutinin CD2-like protein (CD2v). The genome also encodes multiple proteins responsible for virus assembly, DNA replication, and immune modulation within the host (e.g., proteins interfering with type I interferon and cell death pathways) [27].

The virus is highly stable at a pH range of 4–13 and can withstand a temperature of 56 °C for more than 1 h [28]. The virus can readily spread either via direct contact or indirectly via contaminated fomites and swill feed. The recent epidemics of ASF in the European regions are due to the transmission via fomites associated with the feeding of a ship carrying kitchen waste contaminated with ASFV transported via ship. ASFV exhibits a greater resistance to various climatic conditions, and it can persist as infectious in refrigerated meat for a longer period, approximately 84–155 days [14]. ASFV remains viable for several days ranging from 100 to 1000 days in frozen organs and raw meat. As per one study, the curing of ASFV-infected meat has facilitated its survival for almost 1 year [29]. ASFV can remain viable for 30 days in contaminated feed and 60 days in water when it is stored at 4 degrees [30].

Immunology

The manifestation of the disease in the host body relies on the strategies employed by the pathogen to evade the intricate array of immune defence mechanisms it encounters. A comprehensive grasp of the virus-host interactions will serve as a strong foundation for developing an efficacious vaccine. The immune responses triggered by the host can be broadly categorized into two types- innate and adaptive [31]. The innate immune response is considered as the first line of defence against all invading pathogens. The recognition of diverse pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by cellular pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) triggers the initiation of the innate immune response, resulting in the release of type-1 IFNs and a range of pro-inflammatory cytokines. These interferons inhibit virus multiplication, maturation, and dissemination to uninfected cells [32]. ASFV encodes a variety of distinct proteins that can downregulate the expression of numerous immunomodulatory proteins in the host [33]. During ASFV infection, over 150 cellular proteins, including IL-1 and TNF-α, undergo dysregulation.

The virus predominantly replicates in the mononuclear-phagocytic cells, which play an essential role in initiating both adaptive and innate immune responses [34]. However, ASFV is equipped with multiple defence tactics to dodge the host immune responses. The non-essential protein A238Lp blocks the transcription of the genes associated with the host’s immune response, by inhibiting the activity of transcriptional activators. Proteins like A179Lp (a member of the Bcl-2 family), A224Lp (an Inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family member), and C-type lectin EP153Rp play a critical role in preventing programmed cell death during the initial stages of infection. Moreover, the proteins coded by the MGF 505 and MGF 360 genes along with I329L, K205R, A276R, pE120R, and pI215L genes are implicated in blocking the induction of IFNs [35]. The I329L protein was the first ASFV protein identified for its ability to inhibit IFN responses via the TLR3 signalling pathway. Another protein encoded by K205R localizes in the cytoplasm and prevents the activation of IFN-β. As a consequence of this suppression of IFN-α and β, arrays of IFN-stimulated genes remain unexpressed. Another potential immune evasion protein is pDP96R or the UK protein; however, its precise mechanism of action has yet to be elucidated. It is believed to be involved in the downregulation of interferon-1 production by intervening with the cGAS-STING signalling pathway [36]. The MGF360-12L protein significantly contributes to the inhibition of nuclear translocation of transcription factor, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-Κb) [37]. The immunosuppressive genes such as MGF505-7R, MGF505-11R, F317L, and I215L also act by interfering the interferon production [38]. The highly conserved ASFV capsid protein, pE120R, similarly inhibits the IFN-β production by blocking the cGAS-STING pathway [39]. Recently, identified uncharacterized proteins such as F317L, EP364R, and C129R are also involved in restricting the host’s innate immune response [40]. ASFV genes like MGF360-9L and I267L participate in the suppression of interferon expression and the inhibition of the innate antiviral response mediated by the RNA Pol-III-RIG-I, respectively [41–43].

Though the major protein associated with virus neutralization is still unclear, proteins such as p72/B646Lp, p54/E183Lp, and p30/CP204Lp are identified as a target for virus neutralization [44]. Antibodies against p30/CP204Lp impede virus internalization, while antibodies targeting p72/B646Lp and p54/E183Lp prevent virus attachment to host cells. Additionally, viral proteins like CD2v/EP402R, p12/O61Rp, and D117L have been identified as targets for virus neutralization [45]. Besides the antibody response, CD8+ T cells also play a pivotal role in providing protection against ASFV [46]. DNA vaccine immunization studies in pigs have shown that partial protection can be achieved, even when specific antibodies are absent, suggesting a correlation with the induction of CD8+ T cells [47]. The G1340Lp protein [48] and the ASFV structural proteins such as p30/CP204Lp and p72/B646Lp [49] contain cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) determinants; however, their involvement in protection has not been proven. Identifying ASF CTL epitopes essential for protection is a challenging assignment due to the heterogeneity of the T cell population.

ASF vaccine strategies

Viral inactivation and attenuation represent two common strategies utilized in the generation of viral vaccines. Inactivated vaccines retain their antigenicity, but they cannot infect the host due to physical or chemical inactivation [50]. However, inactivated vaccines have the drawback of their inability to elicit a long-lasting immune response, a limitation that attenuated live vaccines overcome [50]. Efforts to develop a vaccine against ASF began as early as the mid-1960s. Various approaches have been explored in the pursuit of a successful ASF vaccine, including inactivated vaccines, subunit vaccines, DNA vaccines, virus-vectored vaccines, and live attenuated vaccines.

Inactivated vaccines

The earliest attempts to develop inactivated ASF vaccines have revealed it to be an infeasible strategy [51]. This could be attributed to the challenge of inducing a cell-mediated immune response in the host, leading to incomplete protection [50]. The pigs that received immunization with glutaraldehyde-fixed ASFV-infected alveolar macrophages and detergent- treated antigens did not attain protection [52–54]. Sang et al. (2020) proposed that enhancing the protective efficacy of inactivated vaccines could be achieved through the incorporation of appropriate adjuvants [55]. However, ASFV particles inactivated by employing binary ethyleneimine (BEI) and adjuvanated with Polygen™ or Emulsigen®-D did not elicit an effective protective immune response [56]. Likewise, gamma irradiated ASFV “Estonia 2014,” when adjuvanated with Polygen™ or Montanide™ ISA 201 VG, was also found to be ineffective. To date, numerous efforts have been done to safeguard animals from the ASFV through various inactivated vaccine formulations. Unfortunately, all of these attempts have proven unsuccessful. Some examples of these unsuccessful inactivated ASF vaccine formulations comprise inactivated infected cell extracts, purified inactivated virions, infected alveolar macrophage cell cultures, and supernatants of peripheral blood leukocytes from the infected pigs [51–53]. In a recent study, Walczak et al. (2022) examined the neutralizing capacity of ASFV using serum collected from survivors of ASF and found that antibodies against ASFV alone are inadequate for inhibiting viral replication [57]. This finding aligns with other reports that have indicated inactivated vaccines as an unviable strategy due to their inability to generate a complete cellular immune response.

Subunit vaccine, DNA vaccines, and virus vectored vaccines

Genetically engineered vaccines, such as subunit vaccines, DNA vaccines, and virus vector vaccines, represent tailored approaches with minimal adverse effects and enhanced safety profiles. Subunit vaccines, in particular, are regarded as the most precise and safest antigen-based vaccine candidates. Ongoing efforts have been directed towards the generation of a subunit vaccine for African swine fever (ASF). Selecting appropriate antigens for inclusion in subunit vaccines against ASFV poses a significant challenge due to the virus’s capacity to encode up to 167 proteins. Numerous ASFV-encoded proteins, such as p54, p30, pp220, pp62, p72, EP153R, D117L, and CD2v, have been identified as participants in various stages of virus attachment and internalization [58]. These proteins have shown immunogenicity and are potential candidates for subunit vaccine development. Additionally, ASFV proteins like CD2v, D117L, and p12 may play roles in generating neutralizing antibodies and inhibiting viral invasion and release. Vaccinating pigs with proteins such as CD2v, p54, and p30, expressed using baculovirus, has been demonstrated to induce the production of neutralizing antibodies, effectively safeguarding them against challenges with virulent ASFV [59]. In a similar vein, Barderas et al. (2001) demonstrated that pigs injected with chimeric proteins p54 and p30 elicited a protective humoral immune response [60]. However, the use of baculovirus- expressed p22, p30, p72, and p54 proteins from ASFV did not elicit adequate protection against the virulent ASFV Pr4 strain. Despite the detection of neutralizing antibodies, their presence alone was not adequate for ensuring protection. The results seem to be subject to debate, possibly due to the interference of other antibodies or variations in the experimental setup. Ruiz-Gonzalvo et al. (1996) utilized baculovirus for CD2v protein expression and administered to pigs along with Freund’s adjuvant [61]. Remarkably, these immunized pigs exhibited a protective response against the homologous ASFV E75 strain, with protection correlating with the dosage administered, despite the lack of neutralizing antibodies. The findings indicated that beyond the presence of neutralizing antibodies, there are additional factors associated with CD2v-induced antibodies contributing to protection that have the capability to hinder red blood cell adsorption and temporarily impede infection [61].

Most of the protective antigens against ASFV currently incorporated into subunit vaccines fall short of providing complete protection for vaccinated pigs. Even when neutralizing antibodies are generated, it remains challenging to evoke substantial immune defence using just a handful of ASFV proteins as antigens. In a broader context, over 50 immunogenic ASFV proteins and 44 virus-packaged polypeptides have been recently identified. Yet, it remains uncertain whether these newly uncovered proteins possess immunogenic properties [62]. The relevant ASFV protective antigen and the current viral strain diversity must be investigated to construct an effective ASF subunit vaccine platform.

In recent times, various innovative strategies have emerged for generating disabled infectious single-cycle (DISC) or replication-deficient mutants as potential vaccine candidates against ASF [63, 64]. In 2023, Zhang et al. conducted an in-vitro expression study of p30, p72, and p54 proteins using the Lactobacillus lactis expression system [65]. Remarkably, the study results indicated that this approach could elicit humoral, cellular, and mucosal immune responses.

Given the significance of antibody-mediated immune responses and the pivotal role of CD8+ T cells in safeguarding against ASF, DNA vaccines present themselves as a viable alternative strategy. These vaccines offer heightened immunogenicity by expressing antigens intracellularly and presenting them alongside MHC-I molecules, a central process for activating CD8+ T cells. However, pigs vaccinated with DNA vaccines encoding the genes p54/E183L and p30/CP204L failed to generate a protective immune response [47]. Subsequently, it was discovered that pigs immunized with a DNA vaccine encoding the ASFV haemagglutinin (HA) extracellular domain (CD2v) fused to the p54/E183L and p30 antigens were able to trigger a robust cell-mediated and humoral immune response. Moreover, pigs that received immunization through a DNA expression library containing multiple ASFV ORFs linked to ubiquitin were documented to exhibit partial protection when challenged with virulent viruses. This partial protection has been attributed to the activation of ASFV-specific T cells, highlighting the critical role of cell-mediated immunity in ASFV infection. Recognizing that peptide or DNA immunization alone cannot confer complete protection, some researchers have advocated for more potent strategies, including a combined DNA–protein vaccination approach. However, when pigs were inoculated with a combination of plasmid DNA (CD2v, p32, p72, ± p17) and recombinant proteins (p54, p15, p35, ± p17), the resulting protection level was not observed as significant [66]. Despite the capacity of DNA vaccines to induce specific T cell responses in the host, they remain insufficient in providing complete defence against the challenges posed by virulent strains [67].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that virus-vectored vaccines can trigger the generation of IFN-γ and specific antibody-mediated humoral immune responses in pigs, leading to partial protection against ASFV challenges. These vectors encompass non-replicative vaccinia derivatives such as modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA), as well as alpha and adenoviruses. In 2019, Lokhandwala et al. (2017) investigated the protective impact and immune response produced by two recombinant adenovirus combination Ad-ASFV-I (A151R, B119L, B602L, EP402R∆PRR, B438L, K205R, A104R, pp62, and p72) and Ad-ASFV-II (p30, p54, pp62, p72, and pp220) [68]. When pigs were inoculated with a combination of Ad-ASFV-I and BioMize0226 adjuvant, despite the substantial IgG response generated in response to the ASFV antigen, the vaccinated pigs proved unable to resist the challenge posed by the virulent Georgia 2007/1 strain. However, Goately et al. (2020) have recently reported that vaccination using an antigen pool comprising eight virus vectored ASFV genes was capable of providing complete protection to the pigs against virulent virus challenge [69]. The concept of a viral-vectored vaccine for ASF holds promise as a comprehensive strategy, yet the pivotal factor for its success lies in the careful selection of antigens, a criterion for which robust candidates are currently in short supply.

Prime-boost vaccination represents an alternative approach aimed at expediting the generation of a sizable memory CD8+ T cell population and assessing the immunogenicity of various ASFV antigens [70]. This screening of diverse ASFV antigens has recently been achieved through a combination of DNA priming and subsequent boost with recombinant vaccinia virus. In this study, roughly 47 viral genes were used to clone into individual plasmids as DNA vaccine as well as into recombinant vaccinia virus as a booster vaccine. Although vaccinated pigs showed some clinical and pathological symptoms after the challenge, the virus load in the blood and various lymphoid organs was much lower when compared to that of the control group [62]. In summary, DNA and peptide-based vaccines stimulate targeted antiviral immune responses, including the generation of neutralizing antibodies and virus-specific T cells. Though, their efficacy in affording protection against virulent virus challenges remains limited and often inadequate.

Cutting-edge technologies like CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing and reverse genetics will play pivotal roles in the screening and selection of the most immunoprotected antigens for vaccine development. By integrating diverse viral vectors and a range of protective antigens, we can anticipate the development of safe and efficacious recombinant vector vaccines in the future.

Naturally and in vitro attenuated vaccines

Many viral diseases have been effectively managed through LAVs, which were traditionally developed through empirical processes such as serial passage of the causative virus in heterologous hosts or in vitro [71]. Live attenuated vaccines, often called as attenuated vaccines, are produced by reducing the pathogenicity of the virulent virus strain through physical and chemical methods, along with genetic modifications (most commonly the deletion of specific genes). Live attenuated vaccines against ASFV are classified into three types: natural attenuated strains, subculture attenuated strains, and recombinant attenuated strains.

Naturally attenuated strains

In the 1960s, the first ASF vaccination strategy was initiated, involving early live vaccines based on attenuated ASFV strains and implemented in Portugal and Spain. Unfortunately, these vaccines led to the emergence of painful chronic lesions in a substantial portion of previously vaccinated animals, contributing to an increase in ASF occurrences in both countries [72]. During the period spanning from 1970s to the 1990s, Russia conducted research aimed at the rational selection of attenuated strains for the development of emergency vaccines. Various strains underwent thorough examination and classification, based on their specific characteristics and serogroups, as determined via hemadsorption inhibition and immunological testing. However, the majority of these candidates continued to elicit mild fever reactions and viremia. While the protection persisted for an extended duration, it was not entirely effective, particularly in animals with compromised immune systems [73]. Subsequently, researchers identified naturally attenuated ASFV strains, such as OUR T88/3 and NH/P68, which were found in chronically infected pigs and soft ticks [44]. The extent of immune protection provided by these two naturally attenuated strains varies, ranging from 66 to 100% when challenged with homologous virulent strains. Later, it was shown that the naturally attenuated strain NH/P68 (genotype I) can provide complete protection against the virulent strain L60 (genotype I) and, notably, even against a heterologous challenge with Arm/07 (genotype II). However, it should be noted that this immunization did lead to some side effects in the vaccinated animals [74].

In an experiment conducted by King et al. (2011), the OUR T88/3 strain was employed for the initial immunization, followed by a booster immunization with the OUR T88/1 strain [75]. Protection rate in the immunized pigs ranged from 85.7 to 100% when challenged with the virulent strains Benin 97/1 and Uganda 1965, respectively. Likewise, in the study conducted by Mulumba-Mfumu et al. (2016), pigs were initially immunized with the OUR T88/1 strain, and a booster immunization was administered using the virulent OUR T88/3 vaccine [76]. As a result, the immunized animals were able to generate cross-protection against a heterologous strain of ASFV genotype Ι. These experimental findings highlight the potential for generating a safe and efficient vaccine capable of providing cross-protection. Recently, a naturally occurring virus strain, Lv17/WB/Rie1, underwent evaluation for its safety and efficacy profile. This strain does not exhibit hemadsorption and features a truncated CD2v (EP402R). An immunization challenge trial was conducted with wild boars under the specified conditions, and in the majority of immunized animals and one early contact control animal, the sole symptom observed was a minor increase in body temperature. A substantial 92% of the animals demonstrated protection against this deadly challenge. While these results are promising, there is still a need for more comprehensive data regarding the protective efficacy and safety [77]. Given the current circumstances, further research is imperative to determine whether the naturally attenuated strain Lv17/WB/Rie1 can indeed serve as an ideal vaccine prototype for effectively managing disease transmission in wild boars [78].

The extent of immunoprotection offered by different attenuated strains may vary, primarily influenced by factors such as dosage, administration route, and the virulence of the challenging virus. Due to their remaining level of virulence, naturally attenuated strains are seldom suitable as vaccine candidates. However, the safety profile can be enhanced by selectively deleting specific genes associated with virulence from these naturally attenuated strains. Moreover, natural attenuated strains are associated with adverse side effects, including symptoms like fever, abortion, and chronic or persistent infections [79]. Efforts have been undertaken to enhance the safety of the naturally attenuated strain OUR T88/3 by removing the I329 gene, which plays a role in inhibiting the innate immune response. However, it is surprising to note that the OURT88/3∆I329L strain resulted in a significant decrease in resistance to the attack by the virulent strain OURT 88/1 [80].

Live attenuated vaccines based on cell passage

Live attenuated vaccines, produced by culturing the virus in cell culture through serial passages, can lead to the spontaneous deletion of segments of the viral genome, subsequently reducing its virulence. In vitro ASFV live attenuated vaccines (LAVs) are typically derived from primary cells like porcine alveolar macrophages (PAMs) and porcine bone marrow (PBM) cells. However, primary cells are not ideal for the large-scale manufacture of vaccines. Following the initial reports of ASF in Europe, researchers commenced efforts to attenuate ASFV in cell culture systems, including porcine bone marrow or kidney cells. [81, 82]. In challenge studies, pigs immunized with these attenuated strains demonstrated protection, but the results obtained from field trials were discouraging [81]. Krug et al. (2015) reported that a virulent strain (ASFV-G) was attenuated after 110 serial passages in the Vero cell line though surprisingly, pigs immunized with these attenuated strains did not achieve protection [83]. According to recent research, a novel strain of ASFV, ASFV-G-ΔI177L/ΔLVR, was adapted in a porcine foetal kidney cell line, and its protective efficacy was observed to be comparable to ASFV-G-ΔI177L [84]. However, the safety and genetic stability of this attenuated strain requires further evaluation.

Gene-deletion mutants

Vaccine candidates generated through gene deletion mutants via homologous recombination stand out as the most promising approach in the fight against ASF (Table 1). The ASFV genome contains a multitude of proteins that enable the virus to manipulate and evade the host’s immune response, exerting control over host cell protein expression, cell cycle, and innate immune reactions, all of which create an environment for viral proliferation. Thus, the exploration of ASFV genes associated with replication, virulence, and immune evasion holds paramount importance in developing gene-deleted vaccines. Viral virulence can be reduced through the targeted knockout of virulence genes (primarily TK, UK, 9-GL, and CD2v) as well as immune evasion genes (like MGF and A238L) using homologous recombination. O’Donnell et al. (2016) successfully engineered a recombinant virus known as ASFV-G-Δ9GL, by removing the 9-GL (B119L) gene from the Georgia 2007/1 isolate (ASFV-G) [85]. This particular isolate is a highly virulent strain originally identified in the Caucasus region in 2007 and prevalent in Eastern Europe [86]. When administered intramuscularly at a dose of 104 HAD50, ASFV-G-Δ9GL caused a lethal disease in pigs, similar to the parental ASFV-G. However, a partial level of protection was observed when a dose of 102 HAD50 was used, with effective results seen when pigs were challenged at 21- or 28- days post-infection. Furthermore, a dose of 103 HAD50 resulted in both partial and complete protection, depending on whether the challenge occurred at 21 or 28 days post-infection. To enhance the virus attenuation, they further deleted the UK gene (DP96R), creating a double gene deletion recombinant virus known as ASFV-G-Δ9GL/ΔUK [85]. Intramuscular inoculation of a high dose (106 HAD50) did not induce disease in pigs, whereas inoculation with a lower dose (104 HAD50) conferred protection against ASFV-G upon subsequent challenge. Another recombinant virus, BeninΔDP148R, was developed by Reis et al. (2020) through the deletion of the DP148R gene [80]. The pigs that received the BeninΔDP148R vaccine not only survived but also displayed mild clinical symptoms following immunization. Notably, all pigs inoculated intramuscularly, and nearly all except one that was immunized intranasally, successfully withstood the challenge posed by the parental virus [87]. ASFV-G-ΔMGF is another recombinant virus created by O’Donnell et al. (2015) by deleting six genes including MGF505, MGF360-1R, MGF360-12L, MGF360-13L, MGF360-14L, MGF505-2R, and MGF505-3R from the Georgia 2007/1 isolate (ASFV-G) [86]. It was found that the replication competence of ASFV-G-ΔMGF in primary pig macrophages was similar to that of the parental virus. Following intramuscular inoculation with ASFV-G-ΔMGF, pigs demonstrated resistance to the challenge posed by the parental strain; however, some safety concerns arose post-vaccination. Consequently, researchers developed a new virus strain, ASFV-G-Δ9G/ΔMGF, by deleting all the genes previously removed in both ASFV-G-Δ9GL and ASFV-G-ΔMGF. Unfortunately, this vaccine proved ineffective in inducing protection against the parent ASFV-G upon challenge.

Table 1.

Gene deleted LAV candidates against ASF

| Vaccine candidate | ASFV strain | Attenuation strategy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASFV-G-Δ9GL | Georgia 2007/1 | Gene deleted (9GL) | [85] |

| ASFV-G-Δ9GL/ΔUK | Georgia 2007/1 | Gene deleted (9GL,UK) | [85] |

| BeninΔDP148R | Benin 97 | Gene deleted (DP148R) | [80] |

| ASFV-G-ΔMGF | Georgia 2007/1 | Gene deleted (MGF505, MGF360-1R, MGF360-12L, MGF360-13L, MGF360-14L, MGF505-2R and MGF505-3R) | [86] |

| BeninΔMGF | Benin 97/1 | Gene deleted (MGF360-10L, 11L, 12L, 13L, 14L), (MGF530/505-1R, 2R, and 3R) (MGF360-9L and MGF530/505-4R) | [87] |

| BA71ΔCD2 | BA71 | Gene deleted (CD2) | [88] |

| HLJ/18-6GD | HLJ/2018 | Gene deleted (MGF360/505) | [89] |

| HLJ/18-7GD | HLJ/2018 | Gene deleted (MGF505-1R, MGF505-2R, MGF505-3R, MGF360-12L, MGF360-13L, MGF360-14L, and CD2v) | [89] |

| ASFV-G-ΔI177 L | Georgia 2007/1 | Gene deleted (I177 L) | [90] |

| SY18∆L7-11 | SY18 | Gene deleted (L7L-L11L) | [91] |

| ASFV-G-Δ184L | ASFV-G | Gene deleted (E184L) | [92] |

| ASFV-g/VΔTK | Georgian ASFV strain | Gene deleted (TK) | [93] |

| ASFV-ΔQP509L/ QP383R | CN/GS/2018 | Gene deleted (QP509L/ QP383R0 | [94] |

BeninΔMGF is a gene-deleted mutant developed by Reis et al. (2016) where they removed genes including MGF360 (MGF360-10L, 11L, 12L, 13L, 14L), MGF530/505 (MGF530/505-1R, 2R, and 3R), and the interrupting genes (MGF360-9L and MGF530/505-4R) from the ASFV Benin 97/1 isolate [87]. Pigs were immunized with initial and final doses of BeninΔMGF, and upon challenge with the parental virus strain, all vaccinated pigs were found to be effectively protected. Through the deletion of the CD2v gene from the BA71 strain, Monteagudo et al. (2017) engineered a novel recombinant virus called BA71ΔCD2 [88]. The pigs that received immunization with BA71ΔCD2 successfully prevented attacks from both the parental BA71 strain and a challenge with the heterologous E75 strain. Furthermore, these vaccinated pigs demonstrated resistance against infection with the Georgia 2007/1 (an ASFV genotype II strain). Even though most of the gene-deleted vaccines without virulence genes can offer full protection, because of the residual virulence there is a chance of virulence resurfacing. The recombinant NH/P68 strain, which lacks the A238L gene, exhibited a highly effective protective response when confronted with the homologous virulent strain L60. However, it is noteworthy that some of the vaccinated pigs did experience viremia and other adverse effects [74]. In a recent study, Chen et al. (2020) employed homologous recombination technology to generate a series of recombinant viruses with diverse genetic modifications using the Pig/HLJ/2018ASFV strain, which originated from China [89]. The attenuated strain HLJ/18-6GD, created by deleting six genes from MGF360/505 of the HLJ/2018 strain, demonstrated the ability to confer protection against the parental virus upon challenge. However, safety assessment data indicate that HLJ/18-6GD carries a significant risk of reverting to a virulent virus strain. In response to this concern, a newly designed gene-deleted mutant called HLJ/18-7GD was developed, involving the removal of seven genes (MGF505-1R, MGF505-2R, MGF505-3R, MGF360-12L, MGF360-13L, MGF360-14L, and CD2v) from the highly virulent Chinese ASFV strain HLJ/18. Studies have demonstrated that HLJ/18-7GD is a reliable and efficient ASFV vaccine candidate and it is anticipated that it will play a vital role in limiting the spread of ASFV. ASFV-G-ΔI177-L is another recently identified vaccine candidate developed from the ASFV Georgia strain [90]. Utilizing homologous recombination technology, the I177 L gene was excised from the parental virus. ASFV-G-ΔI177 L has proven to be safe when administered via parenteral inoculation at a high dose, and it exhibits exceptional efficacy in conferring protection against challenges with the highly virulent parental virus, ASFV Georgia when given at a low dose. A recent study demonstrated that oronasal administration of ASFV-G-ΔI177- L is capable of inducing protection against virulent ASFV-G, yielding results comparable to those achieved through parenteral inoculation with ASFV-G-ΔI177-L. These findings suggest that oronasal delivery of ASFV-G-ΔI177-L may represent an effective vaccine administration method.

SY18∆L7-11 is a gene deletion mutant developed by Zhang et al. (2021) with the aim of exploring the role of the L7L-L11L gene in combating ASFV and assessing its possibility as a vaccine candidate [91]. Notably, among the 15 pigs tested, 11 survived 28 days after immunization with doses of 103 TCID 50 and 106 TCID50. Their research further indicates that the removal of the L7L-L11L gene does not impede the in vitro replication of ASFV. In 2022, Ramirez-Medina et al. conducted a study to investigate the function of the gene MGF110-5L-6L in viral replication in the cell culture and in experimental swine infections [95]. Their findings revealed that this gene does not significantly impact virus virulence or replication.

Additionally, Tran et al. (2022b) carried out a safety study involving ASFV-G-∆I177L in vaccinated piglets aged 6–8 weeks [96]. The study determined that the vaccine did not induce general ASF symptoms and only resulted in transient clinical symptoms, such as mild coughing. Presently, ASFV-G-∆I177L, developed in Vietnam, stands as the sole commercially available vaccine against ASF worldwide [97].

The limited understanding of immune escape mechanisms, as well as the genes linked to ASFV virulence, coupled with subclinical symptoms and vaccine-induced viremia, constitute significant obstacles in the advancement of gene-deleted vaccines. It is anticipated that by unravelling the biological characteristics of uncharacterized ASFV genes, an optimal combination of gene-deleted vaccines can be devised.

Major gaps

Choice of immunogens and virulence-associated genes

The complexity of ASFVs poses a significant challenge in the development of an effective vaccine. The virus encodes an extensive array of proteins that play a critical role in immune evasion. Currently, there is limited information available regarding ASFV virulence-related genes and protective immunogens. The majority of subunit vaccines rely on a restricted number of ASFV antigens, which have shown limitations in providing complete protection for pigs [98]. Live attenuated vaccines (LAVs) seem to be the most promising candidates for the near future, offering the potential for full protection, although safety concerns persist. Hence, it is imperative to pinpoint novel ASF determinants linked to virulence and protective immunogens. A comprehensive screening of the entire ASFV proteome is required for this purpose, and research initiatives should be devised to deliver these immunogens efficiently and cost-effectively.

Protection mechanisms

As of now, there is a paucity of reported studies that investigate the protective mechanisms of experimental ASF vaccines [99]. While live attenuated vaccines are believed to provide complete protection, the specific host immune mechanisms responsible for mediating this protection in the pigs infected with attenuated ASFV strains remain unknown. Even though ASF live attenuated vaccines (LAVs) can elicit protection against homologous ASFV challenges, there is limited understanding regarding their potential for cross-protection against heterologous virus strains [100]. The majority of live attenuated vaccines (LAVs) are developed using ASFV genotypes Ι and ΙΙ strains, which are prevalent in Asia and Europe. However, there has been limited research conducted on field strains within the 24 ASFV genotypes found in African endemic regions [101]. ASFV is a virus with complex morphology, capable of suppressing both adaptive and innate immune responses in pigs by interfering with numerous signalling pathways. Consequently, it is imperative to conduct a comprehensive analysis of factors influencing virulence and find the precise viral proteins associated with these pathways. Understanding the underlying principles of cross-protection can aid in the selection of appropriate vaccines in the event of a new ASFV genotype emerging [75].

Furthermore, it is essential to conduct extensive research into safety concerns, post-vaccination virus shedding, the development of vaccination-related complications, and the adequacy of vaccine protection. Continuous monitoring of live attenuated vaccines in pigs is necessary to assess the risk of reversion to virulent strains. Currently, there is a lack of thorough evaluation regarding the horizontal transmission of ASF live attenuated vaccines and the potential for vertical transmission from vaccinated sows. All these gaps in knowledge must be thoroughly addressed.

Cell lines for LAVs

The absence of a susceptible continuous cell line poses a significant hurdle in the development of live attenuated vaccines. Presently, there is no appropriate cell line accessible for the cost-effective production of ASFV live attenuated vaccine stocks. The challenge lies in identifying a suitable cell line capable of establishing ASFV replication without requiring extensive genetic adaptation [102]. To facilitate biological and immunological research on ASFV, primary cultures of porcine macrophages, monocytes from peripheral blood, or alveolar macrophages have traditionally been employed. However, owing to the lot-to-lot variation, labour-intensive and costly cell extraction procedures, and ethical considerations regarding animal welfare, it is not advisable to employ primary cells in vaccine manufacturing. Chen et al. (2020) demonstrated that primary bone marrow cells can serve as a platform for propagating HLJ/18-7GD [89]. They successfully produced a minimum of 200,000 vaccine doses (each containing 106 TCID50) from the bone marrow of a single SPF piglet. However, this approach raises ethical concerns and may not be considered acceptable. In 2015, efforts were made to adapt specific ASFV strains to stable mammalian cell lines like Vero and CV-1. However, this adaptation process led to genomic alterations in the virus, which occasionally compromised the vaccine's effectiveness [83]. Recently, five unique porcine cell lines of monocyte origin, namely ZMAC, IPAM WT, IPAM-CD163, WSL, and C∆2 + have come under consideration [103]. Furthermore, studies have shown that the COS cell line is exceptionally proficient in supporting the in vitro replication of ASFV viruses with minimal observable adaptation [104]. In contrast, specific in vivo experimental tests using the attenuated NH/P68 strain have revealed that live attenuated vaccines produced in COS cells lost their capacity to provide protection over time [105].

DIVA strategy

The availability of a discriminatory method (DIVA strategy) to distinguish between infected and immunized animals is essential for the implementation of a vaccine. To ensure effective monitoring of immunization campaigns and their impact on vaccinated pigs, positive and negative markers must be employed to accurately differentiate between vaccinated and infected animals. Consequently, the development of a dependable DIVA strategy should be a key consideration alongside vaccine development. Two DIVA strategies have been developed for ASFV live attenuated vaccines (LAVs); one is a multiplex real-time PCR method that targets the P72 gene of wild-type ASFV and the deleted genes of the vaccine virus, while the other is an ELISA designed to detect antibodies induced by the proteins encoded by the deleted genes of the vaccine virus [106].

Despite the availability of several live attenuated vaccine candidates, they all share a common limitation: the inability to differentiate between infected and vaccinated animals. Currently, it remains a significant challenge to predict the impact of gene deletions from ASFV on virus virulence and the vaccine efficacy of live attenuated vaccines (LAVs). This challenge persists due to the substantial gap in our knowledge and understanding of the molecular functions of each protein coded by the ASFV genome. A recent experimental study conducted by Ramirez-Medina et al. (2022a) investigated the role of the ASFV gene MGF110-5L-6L during viral replication in pig macrophage culture and in vivo experimental infections of domestic pigs [95]. Their findings revealed that a recombinant ASFV (ASFV-G-DMGF110-5L-6L), created by deleting the MGF110-5L-6L gene, exhibited robust replication in macrophage cell culture and induced a disease presentation similar to that caused by the parent virus (ASFV-G) infection. Therefore, this gene appears to be non-essential and does not contribute to virus virulence. Moreover, the protein generated by the MGF110-5L-6L gene exhibits a strong immunogenic capacity, suggesting that this gene could be a promising candidate for developing a DIVA vaccine. Following these discoveries, a recombinant virus (ASFV-G-DI177L/DMGF110-5L-6L) was generated by removing the MGF110-5L-6L gene from a gene-deleted LAV candidate known as ASFV-G-DI177L [90]. Inoculation of this recombinant virus into experimental pigs resulted in a robust humoral immune response against all the major ASFV antigens, while no immune response was observed against the deleted gene MGF110-5L-6L. However, the deletion of the MGF110-5L-6L gene had an impact on the protective efficacy of ASFV-G-DI177L, similar to a study in which the deletion of the E184L gene from the LAV ASFV-G-DMGF resulted in reduced protective efficacy [86]. Therefore, it remains challenging to predict which combinations of gene deletions can sustain the protective efficacy of LAV candidates.

Animal models

For a vaccine to be commercialized, an in vivo evaluation of the vaccine candidate has to be carried out to identify a safe and effective vaccine followed by a large-scale clinical evaluation. In vivo evaluation procedure of LAV candidates for its safety and virulence will be done by inoculating different doses of vaccine to pigs and the clinical symptoms will be monitored for 14–28 days [89]. To accomplish this, it necessitates the use of highly secure biosafety level 3 or 4 (BSL-3/4) animal facilities. Throughout the development of ASF vaccines, the in vitro detection of immune responses and the outcomes of in vivo protection have exhibited inconsistency [107]. The advancement of a small animal model capable of assessing ASFV virulence will expedite the assessment of ASF vaccine safety and the functional analysis of virulence-related genes.

Oral immunization of wild boar

The high susceptibility of wild boars to ASFV is a major risk factor in preventing and controlling ASF. Several ASF outbreaks, particularly those in the Russian Federation and Trans-Caucasian countries, have been attributed to the European wild boar populations [108]. Considering the vast population of wild boars, estimated in the millions, in China, there is a growing concern that ASF could become endemic. Therefore, the development of a specific vaccine for preventing disease transmission among the wild boar population is essential to effectively control and eradicate the disease. In endemic regions, the oral vaccination of wild boars against ASFV proves to be a valuable control strategy. This oral immunization approach has been successfully employed in preventing diseases such as pseudorabies and tuberculosis. [109]. A potential vaccine candidate for wild boar populations must exhibit immunogenicity when administered orally, necessitating a higher viral titre in the vaccine. Furthermore, these oral vaccines should demonstrate resilience to environmental factors such as temperature and sunlight to maintain their efficacy in outdoor settings. To date, only a limited number of studies have explored oral immunization in wild boars [110]. In 2019, it was reported that a naturally attenuated vaccine strain, Lv17/WB/Rie1, effectively provided protection to wild boars against virulent challenges, though this achievement remains at the experimental stage only. In another experimental study, the vaccine candidate ASFV-G-∆I177L was administered via the oronasal route to pigs. It was observed that this route of administration induced protection against challenges with the parent virulent virus ASFV-G, and the resulting immune response was comparable to that produced when the vaccine was given via the parenteral route [110]. Additional research is required to thoroughly validate and confirm the safety of administering the vaccine candidate through the oronasal route.

Use of unlicensed vaccines

The majority of the developed vaccine candidates have only reached the experimental stage, rather than the commercial level. Many of the live attenuated vaccine candidates face safety concerns, including the potential for reversion to a virulent strain. An experimental gene-deleted vaccine candidate, HLJ/18-6GD, exhibited increased virulence during experimental infection in pigs [89]. Due to the immense socioeconomic importance of ASF, there is a significant risk of stakeholders illegally deploying promising vaccine candidates before completing thorough efficacy studies.

Conclusion

Despite of the fact that ASF was initially reported nearly a century ago, significant knowledge gaps persist in our understanding of its epidemiology and pathogenesis. The accurate contribution of different hosts, vectors, and environmental factors in disease progression needs to be definitively established. Key priorities for ASF control should involve raising awareness among hunters, farmers, and veterinarians, while also re-evaluating the routes of introduction and transmission to identify the area’s most at risk. Current research on the development of an effective ASF vaccine is yielding some promising results. Future studies should prioritize the development of commercial confirmatory serological tests and cell lines to replace primary cell cultures. Even though, currently, there is a lack of availability of safe and effective ASF vaccines sufficiently to meet the world demand, the path to success may not be far off.

Author contribution

CMS and SSN conceptualized the idea. CMS, SSN, MSSC, and SB did the literature search. CMS, SSN, SS, KV, and PD wrote the manuscript. VKC and A edited the manuscript. SP assisted in revising the manuscript along with CMS and SSN.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The authors confirm that no ethical approval was required.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

M. S Chandana, Email: cms78848@gmail.com.

Sonu S. Nair, Email: sonunair001@gmail.com

References

- 1.FAO (2011) looking ahead in world food and agriculture: perspectives to 2050. FAO, Rome

- 2.OIE (World Organization for Animal Health) (2021) Listed diseases 2021. https://www.oie.int/en/animal-health-in-the-world/oie-listed-diseases-2021/

- 3.Montgomery RE. On a form of swine fever occurring in British East Africa (Kenya Colony) J Comp Pathol. 1921;34:159–191. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costard S, Mur L, Lubroth J, Sanchez-Vizcaino JM, Pfeiffer DU. Epidemiology of African swine fever virus. Virus Res. 2013;173(1):191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penrith ML, Vosloo W. Review of African swine fever: transmission, spread and control. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2009;80 (2):58–62. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v80i2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costard S, Randriamparany T, Humbert C, Franco S, Rasamoelina H, Rakotoharinome M, Rakotondrahanta S, Albina E, Roger F, Pfeiffer DU (2009) Estimating the prevalence of African swine fever in Madagascar. In: 12th Symposium of the International Society for Veterinary Epidemiology and Economics (ISVEE), vol 12. ISVEE

- 7.Ito S, Bosch J, Martínez-Avilés M, Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM. The evolution of African swine fever in China: A global threat Front. Vet Sci. 2022;9:828498. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.828498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajukumar K, Senthilkumar D, Venkatesh G, Singh F, Patil VP, Kombiah S, Tosh C, Dubey CK, Sen A, Barman NN. Genetic characterization of African swine fever virus from domestic pigs in India. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021;68(5):2687–2692. doi: 10.1111/tbed.13986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goonewardene KB, Onyilagha C, Goolia M, Le VP, Blome S, Ambagala A. Superficial inguinal lymph nodes for screening dead pigs for African swine fever. Viruses. 2022;14:83. doi: 10.3390/v14010083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.African Swine Fever (ASF)—Situation report 4. Available online: https://www.oie.int/app/uploads/2022/01/asf-situationreport-4.pdf. Accessed 18 Jan 2022

- 11.OIE (2019) African swine fever: aetiology epidemiology diagnosis prevention and control references. Technical Disease Cards. http://www.oie.int/wahis/public.php?page=home

- 12.Plowright W, Perry CT, Greig A. Sexual transmission of African swine fever virus in the tick, Ornithodoros moubata porcinus. Walton Res Vet Sci. 1974;17:106–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chenais E, Stahl K, Guberti V, Depner K. Identification of wild boar–habitat epidemiologic cycle in African swine fever epizootic. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:810. doi: 10.3201/eid2404.172127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.EFSA Scientific Opinion on African swine fever. EFSA J. 2014;12:3628. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turlewicz-Podbielska H, Kuriga A, Niemyjski R, Tarasiuk G, Pomorska-Mól M. African swine fever virus as a difficult opponent in the fight for a vaccine -Current data. Viruses. 2021;13(7):1212. doi: 10.3390/v13071212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blome S, Gabriel C, Beer M. Pathogenesis of African swine fever in domestic pigs and European wild boar. Virus Res. 2013;173(1):122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallardo C, Soler A, Nieto R, Sánchez MA, Martins C, Pelayo V, Carrascosa A, Revilla Y, Simón A, Briones V, Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM. Experimental transmission of African swine fever (ASF) low virulent isolate NH/P68 by surviving pigs. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2015;62(6):612–622. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM, Mur L, Martínez-López B. African swine fever: an epidemiological update. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2012;59:27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1865-1682.2011.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuyama T, Takano T, Nishik I, Fujiwara A, Kiryu I, Inada M, Sakai T, Terashima S, Matsuura Y, Isowa K. A novel Asfarvirus-like virus identified as a potential cause of mass mortality of abalone. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61492-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galindo I, Alonso C. African swine fever virus: a review. Viruses. 2017;9:103. doi: 10.3390/v9050103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrés G, Simón-Mateo C, Vinuela E. Assembly of African swine fever virus: role of polyprotein. J Virol. 1997;71:2331–2341. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2331-2341.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salas ML, Andrés G. African swine fever virus morphogenesis. Virus Res. 2013;173:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tulman ER, Delhon GA, Ku BK, Rock DL. African swine fever virus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;328:43–87. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68618-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dixon LK, Chapman DA, Netherton CL, Upton C. African swine fever virus replication and genomics. Virus Res. 2013;173:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chapman DA, Tcherepanov V, Upton C, Dixon LK. Comparison of the genome sequences of non-pathogenic and pathogenic African swine fever virus isolates. J Gen Virol. 2008;9:397–408. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bastos ADS, Penrith ML, Cruciere C, Edrich JL, Hutchings G, Roger F, Couacy-Hymann E, Thomson GR. Genotyping field strains of African swine fever virus by partial p72 gene characterisation. Arch Virol. 2003;148:693–706. doi: 10.1007/s00705-002-0946-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reis AL, Goatley LC, Jabbar T, Sanchez-Cordon PJ, Netherton CL, Chapman DA, Dixon LK. Deletion of the African swine fever virus gene DP148R does not reduce virus replication in culture but reduces virus virulence in pigs and induces high levels of protection against challenge. J Virol. 2017;91(24):e01428–e1517. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01428-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plowright W, Parker J. The stability of African swine fever virus with particular reference to heat and pH inactivation. Arch Gesamte Virusforsch. 1967;21:383–402. doi: 10.1007/BF01241738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mebus C, Arias M, Pineda JM, Tapiador J, House C, Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM. Survival of several porcine viruses indifferent Spanish dry-cured meat products. Food Chem. 1997;59:555–559. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sindryakova IP, Morgunov YP, Chichikin AY, Gazaev IK, Kudryashov DA, Tsybanov SZ. The influence of temperature on the Russian isolate of African swine fever virus in pork products and feed with extrapolation to natural conditions. Sel’skokhozyaistvennaya Biol. 2016;51:467–474. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ivashkiv LB, Donlin LT. Regulation of type I interferon responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:36–49. doi: 10.1038/nri3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Innate immunity to virus infection. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:75–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dixon LK, Abrams CC, Bowick G, Goatley LC, Kay-Jackson PC, Chapman D, Zhang F. African swine fever virus proteins involved in evading host defence systems. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2004;100:117–134. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hernaez B, Alonso C. Dynamin- and clathrin-dependent endocytosis in African swine fever virus entry. J Virol. 2010;84:2100–2109. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01557-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Correia S, Ventura S. Goodbourn RME Parkhouse, M. ASFV includes several mechanisms for the manipulation of IFN responses. Cytokine. 2013;63:256. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X, Wu J, Wu Y, Chen H, Zhang S, Li J, Xin T, Jia H, Hou S, Jiang Y. Inhibition of cGAS-STING-TBK1 signalling pathway by DP96R of ASFV China 2018/1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;506:437–443. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.10.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhuo Y, Guo Z, Ba T, Zhang C, He L, Zeng C, Dai H. African swine fever virus MGF360-12L inhibits type I interferon production by blocking the interaction of importin alpha and NF-kappa B signalling pathway. Virol Sin. 2020;36:176–186. doi: 10.1007/s12250-020-00304-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Z, Ai Q, Huang S, Ou Y, Gao Y, Tong T, Fan H. Immune escape mechanism and vaccine research progress of African swine fever virus. Vaccines. 2022;10(3):344. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10030344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu H, Shi K, Sun W, Zhao J, Yin Y, Si H, Qu S, Lu W. Development a multiplex RT-PCR assay for simultaneous detection of African swine fever virus, classical swine fever virus and atypical porcine pestivirus. J Virol Methods. 2021;287:114006. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2020.114006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang J, Li S, Feng T, Zhang X, Yang F, Cao W. African swine fever virus F317L protein inhibits NF-κ B activation to evade host immune response and promote viral replication. Sphere. 2021;6:e0065821. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00658-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y, Ke J, Zhang J, Yue H, Chen T, Li Q. I267L is neither the virulence- nor the replication-related gene of African swine fever virus and its deletant is an ideal fluorescent-tagged virulence strain. Viruses. 2021;14:53. doi: 10.3390/v14010053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ran Y, Li D, Xiong MG, Liu HN, Feng T, Shi ZW. African swine fever virus I267L acts as an important virulence factor by inhibiting RNA polymerase III-RIG-I-mediated innate immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2022;18(1):e1010270. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang K, Yang B, Shen C, Zhang T, Hao Y, Zhang D. MGF360-9L is a major virulence factor associated with the African swine fever virus by antagonizing the JAK/STAT signalling pathway. MBio. 2022;13(1):e0233021. doi: 10.1128/mbio.02330-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arias M, de la Torre A, Dixon L, Gallardo C, Jori F, Laddomada A, Sanchez-Vizcaino, Approaches and perspectives for development of African swine fever virus vaccines. Vaccine. 2017;5:35. doi: 10.3390/vaccines5040035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burmakina G, Malogolovkin A, Tulman ER, Zsak L, Delhon G, Diel DG, Shobogorov NM, Morgunov YP, Morgunov SY. African swine fever virus serotype-specific proteins are significant protective antigens for African swine fever. J Gen Virol. 2016;97:1670–1675. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oura CA, Denyer MS, Takamatsu H, Parkhouse RM. In vivo depletion of CD8+ T lymphocytes abrogates protective immunity to African swine fever virus. J Gen Virol. 2005;86(9):2445–2450. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Argilaguet JM, Pérez-Martin E, Nofrarías M, Gallardo C, Accensi F, Lacasta A, Mora M, Ballester M, Galindo-Cardiel I, Lopez-Soria S. DNA vaccination partially protects against African swine fever virus lethal challenge in the absence of antibodies. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e40942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leitão A, Malur A, Cartaxeiro C, Vasco G, Cruz B, Cornelis P, Martins CL. Bacterial lipoprotein-based expression vectors as tools for the characterisation of African swine fever virus (ASFV) antigens. Arch Virol. 2000;145:1639–1657. doi: 10.1007/s007050070081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alonso F, Domínguez J, Vinuela E, Revilla Y. African swine fever virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognize the 32 kDa immediate early protein (vp32) Virus Res. 1997;49:123–130. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(97)01459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tlaxca JL, Ellis S, Remmele R., Jr Live attenuated and inactivated viral vaccine formulation and nasal delivery: potential and challenges. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;93:56–78. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stone SS, Hess WR. Antibody response to inactivated preparations of African swine fever virus in pigs. Am J Vet Res. 1967;28:475–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Forman AJ, Wardley RC, Wilkinson PJ. The immunological response of pigs and guinea pigs to antigens of African swine fever virus. Arch Virol. 1982;74:91–100. doi: 10.1007/BF01314703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kihm U, Ackerman M, Mueller, H, Pool R (1987) Approaches to vaccination. In: Becker Y (ed) African swine fever. Martinus Nijhoff Publishing, Boston, MA, pp 127–144

- 54.Mebus CA. African swine fever. Adv Virus Res. 1988;35:251–269. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60714-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sang H, Miller G, Lokhandwala S, Sangewar N, Waghela SD, Bishop RP, Mwangi W. Progress toward development of effective and safe African swine fever virus vaccines. Front Vet Sci. 2020;7:84. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.00084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blome S, Gabriel C, Beer M. Modern adjuvants do not enhance the efficacy of an inactivated African swine fever virus vaccine preparation. Vaccine. 2014;32:3879–3882. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Walczak M, Juszkiewicz M, Szymankiewicz K, Szczotka-Bochniarz A, Woźniakowski G. ASF -survivors’ sera do not inhibit African swine fever virus replication in vitro. J Vet Res. 2022;66:21–27. doi: 10.2478/jvetres-2022-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alonso C, Borca M, Dixon L, Revilla Y, Rodriguez F, Escribano JM. ICTV Report Consortium. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: Asfarviridae. J Gen Virol. 2018;99:613–614. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gómez-Puertas P, Rodríguez F, Oviedo JM, Ramiro-Ibanez F, Ruiz-Gonzalvo F, Alonso C, Escribano JM. Neutralizing antibodies to different proteins of African swine fever virus inhibit both virus attachment and internalization. J Virol. 1996;70:5689–5694. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5689-5694.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barderas MG, Rodríguez F, Gómez-Puertas P, Aviles M, Beitia F, Alonso C, Escribano JM. Antigenic and immunogenic properties of a chimera of two immunodominant African swine fever virus proteins. Arch Virol. 2001;146:1681–1691. doi: 10.1007/s007050170056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ruiz-Gonzalvo F, Rodriguez F, Escribano JM. Functional and immunological properties of the baculovirus-expressed hemagglutinin of African swine fever virus. Virology. 1996;218:285–289. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jancovich JK, Chapman D, Hansen DT, Robida MD, Loskutov A, Craciunescu F, Borovkov A, Kibler K, Goatley L, King K. Immunization of pigs by DNA prime and recombinant Vaccinia virus boost to identify and rank African swine fever virus immunogenic and protective proteins. J Virol. 2018;92:e02219–e2317. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02219-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Freitas FB, Simões M, Frouco G, Martins C, Ferreira F. Towards the generation of an ASFV-pA104R DISC mutant and a complementary cell line-a potential methodology for the production of a vaccine candidate. Vaccine. 2019;7:68. doi: 10.3390/vaccines7030068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Urbano AC, Ferreira F. African swine fever control and prevention: an update on vaccine development. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11:2021–2033. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2108342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang H, Zhao S, Zhang H, Shen Y, Zhang P, Shan H. Orally administered recombinant Lactobacillus expressing African swine fever virus antigens that induced immunity responses. Front Microbiol. 2023;13:1103327. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.1103327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sunwoo SY, Pérez-Núñez D, Morozov I, Sánchez EG, Gaudreault NN, Trujillo JD, Mur L, Nogal M, Madden D, Urbaniak K, Kim IJ. DNA-protein vaccination strategy does not protect from challenge with African swine fever virus Armenia 2007 strain. Vaccines. 2019;7(1):12. doi: 10.3390/vaccines7010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bosch-Camos L, López E, Rodriguez F. African swine fever vaccines: a promising work still in progress. Porcine Health Manag. 2020;6(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s40813-020-00154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lokhandwala S, Waghela SD, Bray J, Sangewar N, Charendoff C, Martin CL, Hassan WS, Koynarski T, Gabbert L, Burrage TG. Adenovirus-vectored novel African swine fever virus antigens elicit robust immune responses in swine. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0177007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goatley LC, Reis AL, Portugal R, Goldswain H, Shimmon GL, Hargreaves Z, Ho CS, Montoya M, Sánchez-Cordón PJ, Taylor G, Dixon LK. A pool of eight virally vectored African swine fever antigens protects pigs against fatal disease. Vaccines. 2020;8(2):234. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8020234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kardani K, Bolhassani A, Shahbazi S. Prime-boost vaccine strategy against viral infections: Mechanisms and benefits. Vaccine. 2016;34:413–423. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Minor PD. Live attenuated vaccines: historical successes and current challenges. Virology. 2015;479:379–392. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Petisca NJ. Quelques aspects morphologiques des suites de la vaccination contre la peste porcine Africaine (virose L) au Portugal. Bull Off Int Epiz. 1965;63:199–237. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sered AD, Balyshe VM, Kazakova AS, Imatdinov AR, Kolbasov DV. Protective properties of attenuated strains of African swine fever virus belonging to seroimmunotypes I-VIII. Pathogens. 2020;9(4):274. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9040274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gallardo C, Sánchez EG, Pérez-Núñez D, Nogal M, De León P, Carrascosa AL, Nieto R, Soler A, Arias ML, Revilla Y. African swine fever virus (ASFV) protection mediated by NH/P68 and NH/P68 recombinant live-attenuated viruses. Vaccine. 2018;36:2694–2704. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.King K, Chapman D, Argilaguet JM, Fishbourne E, Hutet E, Cariolet R, Takamatsu HH. Protection of European domestic pigs from virulent African isolates of African swine fever virus by experimental immunisation. Vaccine. 2011;29:4593–4600. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mulumba-Mfumu LK, Goatley LC, Saegerman C, Takamatsu HH, Dixon LK. Immunization of African indigenous pigs with attenuated genotype I African swine fever virus OURT88/3 induces protection against challenge with virulent strains of genotype I. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2016;63:e323–e327. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gavier-Widén D, Ruiz Fons F, Iacolina L (2020) Four years of advances in African swine fever in Europe by the ASF-STOP COST Action.

- 78.Barasona JA, Cadenas-Fernández E, Kosowska A, Barroso-Arévalo S, Rivera B, Sánchez R. Safety of African swine fever vaccine candidate Lv17/WB/ Rie1 in wild boar: overdose and repeated doses. Front Immunol. 2021;12:761753. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.761753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Netherton CL, Goatley LC, Reis AL, Portugal R, Nash RH, Morgan SB, Gault L, Nieto R, Norlin V, Gallardo C, Ho CS. Identification and immunogenicity of African swine fever virus antigens. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1318. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reis AL, Goatley LC, Jabbar T, Lopez E, Rathakrishnan A, Dixon LK. Deletion of the gene for the Type I Interferon Inhibitor I329L from the attenuated African swine fever virus OURT88/3 strain reduces protection induced in pigs. Vaccines (Basel) 2020;8:262. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8020262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Manso Ribeiro J, Nunes-Petisca JL, Lopez-Frazao F, Sobral M. Vaccination against ASF. Bull Off Int Epizoot. 1963;60:921–937. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sánchez BC. Modificatión del virus de la peste porcina Africana en cultivos celulares. Bulletin de l’Office Int des Epizooties. 1963;60:901–919. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Krug PW, Holinka LG, O’Donnell V, Reese B, Sanford B, Fernandez-Sainz I, Gladue DP, Arzt J, Rodriguez L, Risatti GR, Borca MV. The progressive adaptation of a Georgian isolate of African swine fever virus to Vero cells leads to a gradual attenuation of virulence in swine corresponding to major modifications of the viral genome. J Virol. 2015;89(4):2324–2332. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03250-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Borca MV, Rai A, Ramirez-Medina E, Silva E, Velazquez-Salinas L, Vuono E. A cell culture-adapted vaccine virus against the current African swine fever virus pandemic strain. J Virol. 2021;95:e0012321. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00123-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.O’Donnell V, Holinka LG, Sanford B, Krug PW, Carlson J, Pacheco JM, Reese B, Risatti GR, Gladue DP, Borca MV. African swine fever virus Georgia isolate harbouring deletions of 9GL and MGF360/505 genes is highly attenuated in swine but does not confer protection against parental virus challenge. Virus Res. 2016;221:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.O’Donnell V, Holinka LG, Gladue DP, Sanford B, Krug PW, Lu X, Arzt J, Reese B, Carrillo C, Risatti GR. African swine fever virus Georgia isolate harbouring deletions of MGF360 and MGF505 genes is attenuated in swine and confers protection against challenge with virulent parental virus. J Virol. 2015;89:6048–6056. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00554-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Reis AL, Abrams CC, Goatley LC, Netherton C, Chapman DG, Sanchez-Cordon P, Dixon LK. Deletion of African swine fever virus interferon inhibitors from the genome of a virulent isolate reduces virulence in domestic pigs and induces a protective response. Vaccine. 2016;34(39):4698–4705. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Monteagudo PL, Lacasta A, López E, Bosch L, Collado J, Pina-Pedrero S, Correa-Fiz F, Accensi F, Navas MJ, Vidal E. BA71∆CD2: A new recombinant live attenuated African swine fever virus with cross-protective capabilities. J Virol. 2017;91(21):10–1128. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01058-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chen W, Zhao D, He X, Liu R, Wang Z, Zhang X, Li F, Shan D, Chen H, Zhang J. A seven-gene-deleted African swine fever virus is safe and effective as a live attenuated vaccine in pigs. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63:623–634. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1657-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Borca MV, Ramirez-Medina E, Silva E, Vuono E, Rai A, Pruitt S, Holinka LG, Velazquez-Salinas L, Zhu J, Gladue DP. Development of a highly effective African swine fever virus vaccine by deletion of the I177L gene results in sterile immunity against the current epidemic Eurasia strain. J Virol. 2020;94(7):e02017–e2019. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02017-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang J, Zhang Y, Chen T, Yang J, Yue H, Wang L. Deletion of the L7L–L11L genes attenuates ASFV and induces protection against homologous challenge. Viruses. 2021;13:255. doi: 10.3390/v13020255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ramirez-Medina E, Vuono E, Rai A, Pruitt S, Espinoza N, Velazquez-Salinas L. Deletion of E184L, a putative DIVA target from the pandemic strain of African swine fever virus, produces a reduction in virulence and protection against virulent challenge. J Virol. 2022;96:e0141921. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01419-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sanford B, Holinka LG, O'Donnell V, Krug PW, Carlson J, Alfano M. Deletion of the thymidine kinase gene induces complete attenuation of the Georgia isolate of African swine fever virus. Virus Res. 2016;213:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li D, Wu P, Liu H, Feng T, Yang W, Ru Y. A QP509L/QP383R-deleted African swine fever virus is highly attenuated in swine but does not confer protection against parental virus challenge. J Virol. 2022;96:e0150021. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01500-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]