Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the relationship between fungal infection in the female genital tract and infertility.

Data sources

A systematic review was carried out, and the search was conducted in Medline, Embase, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library databases until August 2022. The search strategy used standardized keywords such as “candidiasis” and “infertility,” combined with their respective synonyms. The search was limited to human studies, with no language restrictions.

Study eligibility criteria

Primary articles that evaluated women of reproductive age with and without infertility and related to the presence or absence of candidiasis were included.

Study appraisal and synthesis methods

For the analyses, the odds ratio association measure was used with a confidence interval of 95% using RevMan software (version 5.4).

Results

Eight studies, published between 1995 and 2021 in different countries around the world, were included in this systematic review. Two studies were excluded after sensitivity analysis. A total of 909 participants were included in the group of infertile women and 2363 women in the control group. The age of the evaluated women varied between 18 and 50 years. The random effect model was used and showed no significant difference when comparing candidiasis between fertile and infertile women (odds ratio: 1.44; 95% confidence interval 0.86, 2.41 p= 0.17).

Conclusions

There was no association between candidiasis and female sterility.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-023-01225-6.

Keywords: Candidiasis, Dysbiosis, Infertility, Vaginal infection

Introduction

Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) refers to a disorder characterized by signs and symptoms of vulvovaginal inflammation in the presence of Candida species. VVC is the second most common cause of vaginitis symptoms. The prevalence of VVC is difficult to determine because (1) Candida species, without inflammation, can be identified in the lower genital tract in 10 to 20% of healthy women of reproductive age, (2) the use of self-medication without the need for medical prescription, and (3) need for diagnostic confirmation whose gold standard is Sabouraud agar culture [1, 2]. The prevalence of VVC in Brazil is 18%, and this number may be higher due to underreporting and the presence of asymptomatic, undiagnosed cases. Regarding prevalence according to regions of Brazil, the South and Southeast regions have higher prevalence than the North and Northeast regions [3].

The main cause of VVC is the fungus Candida albicans, responsible for 80 to 92% of episodes [2]. An increase in the frequency of non-C. albicans species has been observed, mainly C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and C. guillermondi, which indicates a possible trend of change in the etiology of candidiasis, after decades of C. albicans predominance [4]. Candida spp. are members of fungal phylum ascomycetes, and C. albicans is an important human pathogen, capable of surviving as a commensal in several anatomically distinct locations, each with its own specific set of environmental pressures [5]. This genus of Candida fungi presents several opportunistic pathogens, with many virulence factors, which take advantage of changes in immunocompromised hosts to invade and damage tissues. This genus of Candida fungi presents several opportunistic pathogens, with many virulence factors (membrane and cell wall barriers, dimorphism, biofilm formation, signal transduction pathway, proteins related to stress tolerance, hydrolytic enzymes, and toxin production), which take advantage of changes in immunocompromised hosts to invade and damage tissues, causing intense vulvar itching, leucorrhoea, dyspareunia, dysuria, edema, and vulvovaginal erythema, and may also be asymptomatic [6].

Marital infertility is defined as the failure to conceive after a period of at least 1 year of frequent sexual intercourse without protective methods. It is a condition that can affect up to 10% of couples in the general population [7]. In recent years, there has been an increase in care for issues related to infertility, and the WHO has started to mention and consider fertility as a reproductive right [8]. According to Babu et al. (2017), pathogens such as Mycoplasma, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae can cause infertility, but the role in infertility of the vaginal microbiome and the presence of fungi in the lower genital tract is unclear [9]. Upper female reproductive tract infections are known to be recognized as one of the causes of female infertility, but lower genital tract infections, both symptomatic and asymptomatic, also seem to be associated [8, 10, 11].

The identification of factors associated with infertility is an important step toward establishing treatment and prevention strategies, and studies related to the disease should be encouraged. In this study, the objective was to evaluate the relationship between the presence of Candida-type fungi in the female genital tract and its relationship with marital infertility.

Methods

This is a systematic review and meta-analysis carried out in accordance with the recommendation of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [12]. The study protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO; http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero; CRD42022374305).

Literature search

The search was conducted in Medline, Embase, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library databases. The search strategy used standardized keywords such as “candidiasis” and “infertility” combined with their respective synonyms. Reference lists of all available primary studies were reviewed to identify additional relevant citations. The search was limited to human studies, with no language restrictions.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

According to evidence-based practice [13], the research question was asked based on the acronym PECOT, where Population of interest (P): women of reproductive age; Exposure (E): women with VVC; Comparison (C): women without VVC; Outcomes (O): infertility; Type of study (T): observational studies (case-control, cross-sectional). The inclusion criteria were women of reproductive age with and without a diagnosis of candidiasis who sought pregnancy. Studies with women outside reproductive age were excluded.

Data collection and extraction

Two reviewers independently (ALCP and SZMF) examined the titles and abstracts for relevance using the Rayyan software (www.rayyan.ai) [14]. Potentially relevant full texts were read in full, and those that met the eligibility criteria were included in this review. The studies selected for inclusion had their data extraction carried out by contemplating data such as author, year, country, the mean age of the study population, and diagnostic method of fungal infection in the vaginal tract, diagnostic method of infertility. The data were extracted independently by two reviewers, and when there was any disagreement, a third reviewer was contacted to resolve the conflict (MIR).

Assessment of risk of bias

The studies were assessed for methodological quality using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. This tool is presented through a “star system” to evaluate each study by the selection of the study groups, the comparability of the groups, and verification of the exposure (for case-control studies) or the results (for cross-sectional studies). Studies with scores between seven and nine stars are considered high quality and low risk, scores between four and six stars are high risk of bias, and studies with zero to three stars are considered very high risk of bias [15].

Data analysis

The results were expressed through tables and graphs. Forest plots were made to indicate the effects studied for certain outcomes. For the analyses, the odds ratio (OR) association measure was used with a 95% confidence interval using RevMan software (version 5.4). Heterogeneity across studies in the metanalysis was done using the I2 statistic: the I2 which numbers of 0 to 40% might not be important; 30 to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity; 50 to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity; and 75 to 100% considerable heterogeneity. We use the random effects model in the case of heterogeneity and the fixed effect model when heterogeneity was 0%.

Results

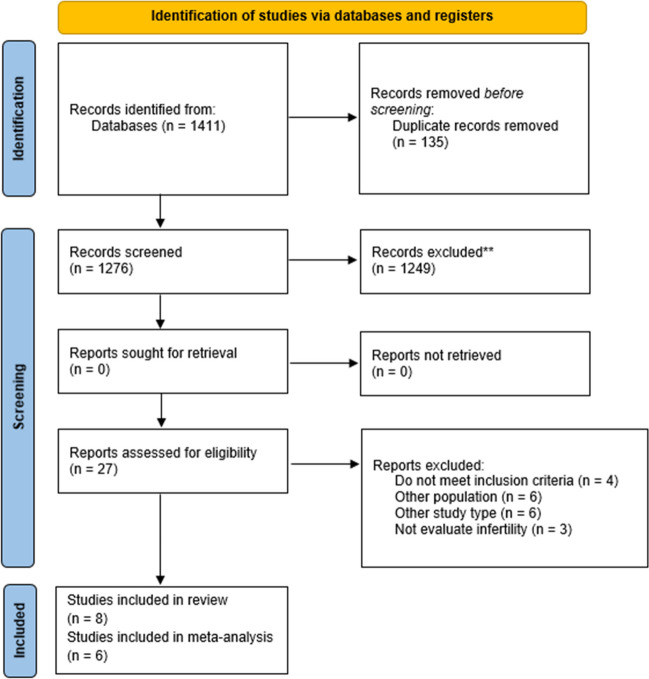

The research identified a total of 1411 studies, and no additional studies were found through other sources. Of these, 135 studies were excluded due to duplication. The remaining 1276 studies were included for reading titles and abstracts, 1249 of which were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. The remaining 27 articles were included for full-text reading. Four studies did not meet the inclusion criteria [16–19]. Six studies were excluded due to presenting different study designs [20–25]. Furthermore, six studies were excluded due to different population [26–31]. Finally, three studies did not evaluate infertility and were also excluded [32–34]. Eight studies were included in this systematic review [9, 11, 35–40] with four cross-sectional studies [9, 36, 38, 39] and four case-control studies [11, 34, 36, 38]. The selection process for studies found in databases is shown in Fig. 1. The included studies were published between 1995 and 2021. The studies were carried out in the following countries: India (3), Italy (1), Cuba (1), Ukraine (1), Nigeria (1), and Spain (1). The age of the women included ranged between 18 and 50 years (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Author, year | Country | N total | Fertile women | Prevalence of candidiasis in fertile women | Infertile women | Prevalence of candidiasis in infertile women | Age group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n total | No candidiasis | n total | No candidiasis | ||||||

| Almanza et al, 2011 | Cuba | 189 | 100 | 65 | 65.4% | 89 | 18 | 20.2% |

30.4 years in infertile women 24.3 years in the fertile |

| Babu et al, 2017 | India | 200 | 84 | 10 | 11.9% | 116 | 30 | 25.8% | X |

| Casari et al, 2010 | Italy | 952 | 556 | 67 | 12.0% | 396 | 20 | 5.0% | 35 years |

| Krotik et al, 2021 | Ukraine | 126 | 30 | 0 | 0.0% | 96 | 17 | 17.7% | x |

| Kumari et al, 2020 | India | 1100 | 1000 | 210 | 21.0% | 100 | 26 | 26.0% |

40% of infertile women aged 25–30 48% of fertile 25–30 year olds |

| Oknofua et al, 1995 | Nigeria | 178 | 86 | 25 | 29.1% | 92 | 23 | 25.0% |

27.5 years in infertile women 28 years in the fertile |

| Rao et al, 2017 | India | 1124 | 992 | 211 | 21.2% | 132 | 33 | 25.0% |

40.1% of infertile women aged 26–30 years 47.08% of the fertile 26–30 year olds. |

| Rodriguez et al, 2001 | Spain | 487 | 111 | 17 | 15.3% | 376 | 48 | 12.9% |

30.6 years in infertile women 29.9 years in the fertile |

As for the results that evaluated the presence of candidiasis in the included women, in the study by Almanza et al. (2011) [34], the presence of Candida spp. was identified in 20.2% of infertile women and 65.4% in the control group. In the study by Babu et al. (2017) [9], among the 116 women evaluated with infertility problems, 102 samples had growth. In these samples, 113 germs were found and 14 samples had no growth, the most dominant flora being Candida spp. (30, 25.8%). In the study by Casari et al. (2010) [35], Candida species had a frequency of 12.1% in the symptomatic population, second only to Gardnerella vaginalis (26.7%). In the study by Kumari et al. (2010) [37], the presence of vaginal candidiasis was 26% in women with primary infertility and 21% in fertile women. In the study by Okonofua et al. (1995) [36], C. albicans was the most common pathogenic organism isolated, being present in 25% of infertile women and 29.1% of pregnant women. In the study by Rao et al. (2017) [38], the overall prevalence of candidiasis was 21.71% (244/1124), not being significantly different between the two evaluated groups. Finally, in the study by Rodriguez et al. (2001) [39], the genus Candida had an incidence of 15.3% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Methods and results of the included studies

| Author, year | Study design | Infertility diagnostic criteria | Candidiasis diagnostic criteria | Control group | Prevalence of candidiasis in infertile women and the control group | Main results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almanza et al, 2011 | Cross-sectional | Being consulted at the infertility outpatient clinic due to an obstructive factor at the study hospital | Investigated the presence of Candida fungus in cervical and endovaginal samples | Pregnant women about to give birth |

Fertile: 65.0% Infertile: 20.2% |

p < 0.0001 | There was a significant difference between the infertile candidiasis and pregnant candidiasis groups—but there were more cases of candidiasis in pregnant patients. |

| Babu et al, 2017 | Cross-sectional observational retrospective | Having been treated at the infertility outpatient clinic of the study hospital, both primary and secondary infertility |

Two vaginal swabs (fundus x cervical) were collected. One for fresh examination and the other for culture on Sabouraud’s Dextrose Agar (SDA) and incubated at 25±2°C. |

Healthy women with regular menstrual cycles and no previous gynecological diseases. |

Fertile: 11.9% Infertile: 25.8% |

p - 0.041 | There was a significant difference between healthy and infertile women in the presence of Candida in the usual vaginal flora. |

| Casari et al, 2010 | Retrospective analysis | Screening program women before IVF at the study site | An Affirm VPIII sample collection set was used, and one was collected with an Amies-Stuart medium. A vaginal smear was taken by a third vaginal swab on a glass slide. | Fertile women, but does not describe how they were selected |

Fertile: 12.0% Infertile: 5.0% |

p<0.001 | The reasons for the prevalence of some microorganisms in the population of asymptomatic women with infertility problems need to be better analyzed, especially after recent studies on the correlation between idiopathic infertility and the presence of cytokines at cervical levels in women with abnormal vaginal flora. |

| Krotik et al, 2021 | Case-control | Women with a previous history of STIs who were planning IVF techniques at the study site | A comprehensive microbiological analysis, involving smear microscopy, culture, and molecular DNA analysis of pathogens from the vagina, cervical canal, uterine cavity (endometrium) using PCR. | Women of reproductive age who desire a pregnancy without a history of infertility |

Fertile: 0.0% Infertile: 17.7% |

X | X |

| Kumari et al, 2020 | Cross-sectional | Women with a partner for more than two years, sexually active, not using modern contraception and without children | Vaginal swab culture for specific culture of Candida sp. | Women treated at the same outpatient clinic who did not meet the criteria for infertility |

Fertile: 21.0% Infertile: 26.0% |

p - 0.37 | The prevalence of candidiasis was 21.45% (236/1100), and the prevalence of candidiasis was not significantly different between groups with or without infertility. |

| Oknofua et al, 1995 | Case-control | Inability to establish a pregnancy within two years for couples of reproductive age who are having sex without contraception. | Swab cultures with the vaginal and endocervical collection were inoculated into Sabouraud dextrose Agar supplemented with penicillin/neomycin and initially incubated at 29°C for 3-7 days and speciation as Candida albicans was done by producing germ tubes on corn flour agar. | Pregnant women who attend prenatal care in the same period with the same age group and education |

Fertile: 29.0% Infertile: 25.0% |

p > 0.05 | Candida albicans was the most common pathogenic organism isolated in both groups. Infertile women in Nigeria have higher rates of cervical transport of facultative and pathogenic microorganisms compared to pregnant controls. A greater proportion of infertile women than pregnant women also had a previous pelvic inflammatory disease and induced abortion. |

| Rao et al, 2017 | Cross-sectional | X | Vaginal swab culture for the specific culture of Candida sp. | Married women of reproductive age were treated at the hospital without criteria for infertility. |

Fertile: 21.2% Infertile: 25.0% |

p - 0.32 | There was no significant difference in the prevalence of candidiasis between the groups with and without infertility. |

| Rodriguez et al, 2001 | Case-control | Direct seeding in culture medium: Saboureaud agar for the diagnosis of Candida spp. As well as culture of semen from partners in the same medium. | Fertile women |

Fertile: 15.3% Infertile: 12.9% |

p > 0.0 5 | There was no significant difference in Candida infection in fertile and infertile patients. |

Synthesis of results

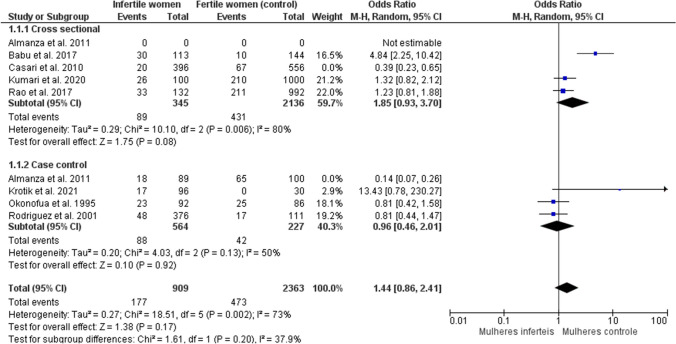

The meta-analysis was carried out using a random effect model, showing no significant difference in the presence of candidiasis in fertile and infertile women (OR: 1.44; 95% CI 0.86, 2.41 p=0.17; I2= 73%) for six studies, with 909 participants in the infertile women group and 2363 women in the control group, regardless of the type of study design (Fig. 2). At first, the eight studies were included in the meta-analysis, but with 90% heterogeneity. The studies by Almanza et al. (2011) [34] and Casari et al. (2010) [35] were excluded from the meta-analysis after sensitivity analysis, reducing heterogeneity to 73%. Casari et al. (2010) [35] presented as control pregnant women close to giving birth with a high presence of candidiasis, which may be characteristic of the gestational period, since during the entire pregnancy and even more so at the end of it, a habitual change in the flora is common vaginal bacteria due to changes in the mother’s body and hormonal profile during this period. The study by Almanza et al. (2011) [34] is a poster, which limited the search for information about the possible causes of heterogeneity in this study. To avoid possible biases in the interpretation of the results, these studies were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of the presence of candidiasis in fertile and infertile women

Risk of bias of included studies

All studies included in this review were assessed for risk of bias using the Newcastle-Ottawa risk of bias scale adapted for case-control studies and the scale adapted for cross-sectional studies. For case-control studies, when performing the risk of bias analysis, the maximum score on the scale is nine stars in the studies by Krotik et al. (2021) [11], Okonofua et al. (1995) [36], and Rodriguez et al. (2001) [39] scored 8/9, presenting a reduction in the score only in the item referring to comparison. The study by Almanza et al. (2011) [34] scored 7/9 as it is a poster, and some important information regarding the definition of controls was not informed, thus reducing the score (Table 3).

Table 3.

Newcastle-Ottawa risk of bias tool for case-control studies. Average score: 9

| Are the case definitions adequate? | Representativeness of cases | Selection of controls | Definition of controls | Comparability of cases and controls based on designs and analyses | Exposure assessment | Similar methods for checking cases and controls | Non-response rate | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Almanza, 2011 | * | * | * | - | * | * | * | * | 7 |

| Krotik., 2021 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8 |

| Okonofua, 1995 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8 |

| Rodriguez et al. 2001 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8 |

For cross-sectional studies, the risk of bias analysis score reaches 10 stars. In the studies included in this review, Babu et al. (2017) [9] and Casari et al. (2010) [35] scored 7/10, for not presenting information regarding the selection process of participants to evaluate the sample, exposure, and comparison. The study by Rao et al. (2017) [38] scored 8/10, due to incomplete information for exposure and comparison, while Kumari et al. (2020) [37] was rated 9/10 for lack of data in the comparison assessment (Table 4).

Table 4.

Newcastle-Ottawa risk of bias tool for cross-sectional studies. Average score: 10

| Representativeness of the sample | Sample size | non-responders | Exposure assessment | Comparability | Study evaluation | Statistical tests | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Babu, 2017 | * | - | * | * | * | ** | * | 7 |

| Casari, 2010 | * | - | * | * | * | ** | * | 7 |

| Kumari, 2020 | * | * | * | ** | * | ** | * | 9 |

| Rao, 2017 | * | * | * | * | * | ** | * | 8 |

Discussion

This is the first systematic review that evaluated the association of candidiasis in the female genital tract with infertility. The association between the vaginal flora with the presence of fungal infection and infertility is not clear, and few studies on the subject are available so far. The female lower genital tract has a wide variety of microorganisms in variable quantity and proportion that form an environment in balance to generate local protection against infections [40]. Candida-type fungi, in general, are part of the usual vaginal microbiota and normally do not pose any threat because they are maintained in controlled quantities by the presence of other microorganisms, by the local innate immune response, and by the vaginal epithelial barrier. In some situations, such as immunosuppression, use of antibiotics or glucocorticoids, hospitalization, and exposure to estrogen, the fungus can break the local balance and become a pathogen [41]. Imbalances in the usual vaginal flora, such as bacterial vaginosis, are related to complications in the gestational period, such as premature labor, preterm ruptured sacs, and chorioamnionitis [40]. During pregnancy, VVC is considered to become more common and tends to be difficult to eradicate because there are several physiological changes in the genitourinary tract of pregnant women that favor the growth of fungi, such as weakened immune system, increased level of reproductive hormones, glycogen deposition, low vaginal pH, and decreased cell-mediated immunity [42]. Furthermore, one of the main virulence factors that contribute to the pathogenic potential of C. albicans is the expression of proteins for adhesion and invasion, and hormonal changes can directly influence these two factors, stimulating them [2]. However, few studies have been conducted to relate the presence of vaginal fungi and infertility.

For Leitich et al. (2007) [43] and Martin et al. (2012) [44], altered vaginal flora is more common among infertile women, who would be more prone to evident changes in the composition of the microbiota, depletion of lactobacilli, and colonization of the vagina with different bacteria. C. albicans can grow in the forms of yeast and hyphae and form biofilm, which are important factors capable of preventing fertilization. Despite this, in the present study, no significant difference was found between women with or without infertility and the presence of candidiasis; therefore, it is likely that the disease is not related to infertility in isolation. In studies conducted by Casari et al. (2010) [35], Okonofua et al. (1995) [36], and Rodriguez et al (2001) [39], a greater presence of candidiasis was evidenced in women considered fertile who were part of the control group.

Women of reproductive age, who do not want pregnancy, may be using oral estrogen as contraception, which is considered a risk factor for the development of the disease. Estrogen is thought to be involved in the growth and increased adhesion of Candida to vaginal epithelial cells and may lead to an increase in glycogen levels, which is a nutritional supply for Candida. Vaginal lactobacilli also produce glucose by breaking down glycogen and converting it to lactic acid, which promotes an acidic environment suitable for Candida growth [43–45].

As previously described, in some situations, such as immunosuppression, use of antibiotics, hospitalization, and exposure to estrogen, the fungus can break the balance of the local vaginal flora and become a pathogen [46]. Thus, due to the physiological changes of pregnancy, such as high estrogen levels and immunosuppression, this is a period of naturally greater susceptibility to this type of infection. The study by Almanza et al. (2011) [34] used pregnant patients about to give birth among women in the control group. This may have increased the prevalence of candidiasis in the control group and led to the final result of the study, which found a significant difference between candidiasis in the infertile group and the control group, disagreeing with the final result of the systematic review carried out.

Increasingly, the role of Candida-like yeast infection in male infertility is being studied. Tuttle et al. (1977) [47], Wittemer et al. (2004) [19], Golshani et al. (2006) [48], Tian et al. (2006) [23], and Burrello et al. (2009) [49] suggest a relationship between the presence of Candida-type fungus in the male genital tract and changes in sperm vitality and motility. Recently, Sasikumar et al. (2013) [50], Sasikumar et al. (2013) [51], and Castrillon-Duque et al. (2018) [52] also related the loss of motility and decreased sperm survival time when incubated with Candida-type fungi; in addition, changes in DNA, cellular necrosis, and apoptosis and other modifications of the male sperm cell were also observed in the presence of fungi. These studies were not included in our systematic review because they did not analyze the outcome, which was infertility, but suggest that a male or chronic vaginal infection by Candida can influence fertility by changing the male factor and not by endometrial and tubal changes as other infections commonly present, but further research is needed to properly evaluate these results. In a study carried out by Trajano et al. [53], studied 104 vaginal yeast samples obtained during routine clinical examinations of a population treated at the Military Police Medical Center, São Paulo, Brazil, divided into two groups: patients with VVC and colonized patients. C. albicans was the most frequently isolated species (55%), but a considerable rate of other Candida species isolated (30%) was observed, including Candida orthopsilosis only in the infected group. There were also other rare genera such as Rhodotorula, Yarrowia, and Trichosporon (15%), of which Rhodotorula mucilaginosa was the most prevalent in both groups.

The lack of homogeneity in the control group, the lack of definition of infertility and how the diagnosis of candidiasis was made, the non-discrimination of how the criteria for selection of participants was made, and the lack of information such as the age of participants are important limitations of the systematic review performed. Age, for example, directly influences fertility, and in most studies, it was not properly evaluated. According to Abdelhameed et al. (2020) [41], the lack of studies, the selection criteria used, and the wrong diagnosis of Candida impair the assessment of the relationship between the disease and infertility. Therefore, for better elucidation of the subject, it is recommended to carry out more studies, with a better diagnosis of infertility and candidiasis, both clinical and laboratory. The control groups to be used in the studies must also be of higher quality. Research into chronic or recurrent candidiasis and infertility, assessing the long-term influence of the fungus on the male factor, also needs to be better elucidated. In addition, factors such as stress, diabetes mellitus, use of glucocorticoids, and personal hygiene habits are also considered risk factors for the development of vaginal fungi [2] and were not evaluated in the included studies, therefore may be a limiting factor.

Conclusion

In this systematic review, no significant difference was observed in women with infertility and the presence of VVC. In the studies included, the genus Candida spp., with emphasis on C. albicans, was the main cause of VVC.

Supplementary information

(DOCX 31 kb)

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sobel JD. Vulvovaginal candidosis. Lancet. 2007;369(9577):1961–1971. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60917-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonçalves B, Ferreira C, Alves CT, Henriques M, Azeredo J, Silva S. Vulvovaginal candidiasis: epidemiology, microbiology and risk factors. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2016;42(6):905–927. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2015.1091805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carvalho GC, De Oliveira RAP, Araujo VHS, Sábio RM, De Carvalho LR, Bauab TM, Chorilli M. Prevalence of vulvovaginal candidiasis in Brazil: a systematic review. Med Mycol. 2021;59(10):946–957. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myab034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadeghi G, Ebrahimi-Rad M, Mousavi SF, Shams-Ghahfarokhi M, Razzaghi-Abyaneh M. Emergence of non-Candida albicans species: epidemiology, phylogeny and fluconazole susceptibility profile. J Mycol Med. 2018;28(1):51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calderone RA, Fonzi WA. Virulence factors of Candida albicans. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9(7):327–335. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Staniszewska M. Virulence factors in Candida species. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2020;21(3):313–323. doi: 10.2174/1389203720666190722152415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habbema JD, Collins J, Leridon H, Evers JL, Lunenfeld B, te Velde ER. Towards less confusing terminology in reproductive medicine: a proposal. Hmm Play. 2004;19(7):1497–1501. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perslev K, Msemo OA, Minja DTR, et al. Marked reduction in fertility among African women with urogenital infections: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Babu G, Singaravelu BG, Srikumar R, Reddy SV, Kokan A. Comparative study on the vaginal flora and incidence of asymptomatic vaginosis among healthy women and in women with infertility problems of reproductive age. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(8):DC18–DC22. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/28296.10417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakraborty A, Dalal A, Shah SR, Deshmukh CS, Lahiri KK. Screening of infertile females for vaginal candidiasis. Int J Adv Res. 2017;5(3):1509–1513. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krotik OI. Characteristics of the vaginal microbiota, cervical and utterine flora in women with the past history of sexually transmitted infections. Wiad Lek. 2021;74(4):896–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hrobjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123(3):A12–A13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell PJOOHRI. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2011. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aguilera MA, Carrasco JR, Perez AE, Alonso JLG, Gonzalez YP. Characterization of predisposing factors of sexual behavior in infertile couples. Guise. Enero-Diciembre. 2018. Multimed. 2020;24(5):1022–1032. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le MT, Nguyen TLN, Le DD, et al. It is genital tract infection related to tubal diseases in infertile Vietnamese women. J Infect DevCtries. 2019;13(10):906–913. doi: 10.3855/jidc.11632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mishra SP, Panda R, Patnaik T, et al. Surveillance of microbial flora for infertility couples in an Indian tertiary car teaching hospital. Asian J Pharm Clin Res. 2017;10(4):405–408. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wittemer C, Bettahar-Lebugle K, Ohl J, et al. Bacterienne vaginale colonization abnormale et implantation en assistance Médicale à la procréation. Gynecol Obstet Ferti. 2004;32:135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogouyemi-Hounto A, Adisso S, Djamal J, et al. Place des candidoses vulvovaginales au cours de infections génitales basses et facteurs de risque associés chez les femmes au Bénin [Place of vulvovaginal candidiasis in the lower genital tract infections and associated risk factors among women in Benin] J Mycol Med. 2014;24(2):100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagy B, Sutka P, Ziwe-el-Abidine M, et al. Candida guilliermondii var. guilliermondii infection in infertile women. Mycoses. 1989;32(9):463–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1989.tb02283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abu-Elteen KH, Abdul Malek AM, Abdul Wahid NA. Prevalence and susceptibility of vaginal yeast isolates in Jordan. Mycoses. 1997;40(5-6):179–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1997.tb00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tian YH, Xiong JW, Hu L, Huang DH, Xiong CL. Candida albicans and filtrates interfere with human spermatozoal motility and alter the ultrastructure of spermatozoa: an in vitro study. Int J Androl. 2007;30(5):421–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2006.00734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vander H, Prabha V. Evaluation of fertility outcome as a consequence of intravaginal inoculation with sperm-impairing micro-organisms in a mouse model. J Med Microbiol. 2015;64(Pt 4):344–347. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherman KJ, Daling JR, Weiss NS. Sexually transmitted diseases and tubal infertility. Sex Transm Dis. 1987;14(1):12–16. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198701000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajalakshmi R, Kalaivani S. Prevalence of asymptomatic infections in sexually transmitted diseases appears diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis, vaginal candidiasis, and trichomoniasis. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2016;37(2):139–142. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.192121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosleh A, Abdul-Razzaq MS. Bacterial isolates associated with pelvic inflammatory diseases among women of reproductive age in Babylon Province. J Global Pharma Technol. 2020;12(1):607–613. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomsíková A, Tomaierová V, Kotál L, Novácková D. An immunologic study of vaginal candidiasis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1980;18(6):398–403. doi: 10.1002/j.1879-3479.1980.tb00528.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verghese S, Padmaja P, Asha M, Elizabeth SJ, Anitha A, Kundavi KM, Varma T. Prevalence, species distribution and antifungal sensitivity of vaginal yeasts in infertile women. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2001;44(3):313–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sensini A, Verducci N, Ulissi A, Sposini T, Sbaraglia G, Pasqualucci P, Tedeschi L, Angelini A. Infezioni dell'apparato genitale femminile e infertilita: 4 Anni di studio. Microbiologi Clinici Italiani. 1997;12(2):60–63. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sopia AR, Joseph PID, Kalyani M, Ananthi B, Dhanaraj S, Henry AJ. Aerobical vaginosis among women attending an infertility clinic at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Chennai, India and susceptibilitu pattern as isolates. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2021;15(1):194–200. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azima S, Houshyar S, Motamedifar M, et al. The effect of vaginal probiotic capsule on vaginal colonization and treatment results in patients with vulvar and vaginal candidiasis. J Adv Med Biomed Res. 2018;26(114):40–50. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiesenfeld HC, Manhart LE. Mycoplasma genitalium in women: current knowledge and research priorities for this recently emerged pathogen. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(suppl_2):S389–S395. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Almanza C, Ricardo M, González A. Relation between female infertility and sexually transmitted genital infections. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(0):A157–A158. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Casari E, Ferrario A, Morenghi E, Montanelli A. Gardnerella, Trichomonas vaginalis, Candida, Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum in the genital discharge of symptomatic fertile and asymptomatic infertile women. New Microbiol. 2010;33(1):69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okonofua FE, Ako-Nai KA, Dighitoghi MD. Lower genital tract infections in infertile Nigerian women compared with controls. Genitourin Med. 1995;71(3):163–168. doi: 10.1136/sti.71.3.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumari S, Chauhan A, Thaper D, Prabha V. Sperm immobilization factor of Candida albicans: a proposed mechanism of infertility in female mice. Glob J fertile Res. 2019;5(1):001–006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rao LK, Keerthi M, Vutharkar NR, Rani UK. Determinants of primary infertility among women of reproductive age group in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India. Natl J Community Med. 2017;8(4):183–187. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodríguez AZ, de Bedout GC, Restrepo CAA, Parra HH, Arteaga MA, Moreno ÁR, Marín ÁG. Sensibilidad a fluconazol y voriconazol de especies de Candida aisladas de pacientes provenientes de unidades de cuidados intensivos en Medellín, Colombia (2001–2007) Rev Iberoam Micol. 2010;27(3):125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mania-Pramanik J, Kerkar SC, Salvi VS. Bacterial vaginosis: a cause of infertility? Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20(11):778–781. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdelhameed A, Hilal HA, Alqaysi R. The synergistic effect of Candida sp and vaginal bacterial infection on infertility: a review. Plant Achives. 2020;20(2):4501–4510. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rani TS, Srikumar R, Reddy EP, Kumar N. The incidence and prevalence of virulence factors of vaginal candidiasis in pregnant women with diabetes mellitus. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2019;10(5):294–299. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leitich H, Kiss H. Asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis and intermediate flora as risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;21(3):375–390. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin DH. The microbiota of the vagina and its influence on women’s health and disease. Am J Med Sci. 2012;343(1):2. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31823ea228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fidel PL, Jr, Cutright J, Steele C. Effects of reproductive hormones on experimental vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2000;68(2):651–657. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.651-657.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burkman R, Schlesselman JJ, Zieman M. Safety concerns and health benefits associated with oral contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(4 Suppl):S5–S22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tuttle JP, Bannister ER, Derrick FC. Interference of human spermatozoal motility and spermatozoal agglutination by Candida albicans. J Urol. 1977;118(11):797–799. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)58197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Golshani M, Taheri S, Eslami G, Suleimani Rahbar AA, Fallah F, Goudarzi H. Genital tract infection in asymptomatic infertile men and its effect on semen quality. Iran J Public Health. 2006;35(3):81–84. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burrello N, Salmeri M, Perdichizzi A, et al. Candida albicans experimental infection: effects on human sperm motility, mitochondrial membrane potential and apoptosis. Play Biomed Online. 2009;18(4):496–501. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sasikumar S, Dakshayani D, Sarasa D. An investigation of DNA fragmentation and morphological changes caused by bacteria and fungi in human spermatozoa. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2013;2(4):84–96. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sasikumar S, Dakshayani D, Franklin A, Rajkumar S. An in-vitro study of effectiveness of uropathogenic yeasts on male infertility. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2013;2(5):233–246. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Castrillon-Duque EX, Puerta Suarez J, Cardona Maya WD. Yeast and fertility: effects of in vitro activity of Candida spp. on sperm quality. J Reprod Infertile. 2018;19(1):49–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trajano DTM, Melhem MDSC, Takahashi JPF, Bonfietti LX, de Araújo MR, Corrêa VB, Fernandes CG. Species and antifungal susceptibility profile of agents causing vulvovaginal candidiasis in a military population: a cross-sectional study. Med Mycol. 2023;61(3):myad025. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myad025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 31 kb)