Abstract

Sichuan is a significant aquaculture province in China, with a total aquaculture output of 1.72 × 106 tons in 2022. One of the most significant microorganisms hurting the Sichuan aquaculture is Aeromonas hydrophila, whose genotype and antibiotic resistance are yet unknown. This study isolated a total of 64 strains of A. hydrophila from various regions during September 2019 to June 2021 within Sichuan province, China. The technique of Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST) was used for the purpose of molecular typing. Meanwhile, identification of antibiotic resistance phenotype and antibiotic resistance gene was performed. The findings of the study revealed that 64 isolates exhibited 29 sequence types (ST) throughout different regions in Sichuan, with 25 of these ST types being newly identified. Notably, the ST251 emerged as the predominant sequence type responsible for the pandemic. The resistance rate of isolated strains to roxithromycin was as high as 98.3%, followed by co-trimoxazole (87.5%), sulfafurazole (87.5%), imipenem (80%), amoxicillin (60%), and clindamycin (57.8%). Fifteen strains of A. hydrophila exhibited resistance to medicines across a minimum of three categories, suggesting the development of multidrug resistance in these isolates. A total of 63 ARGs were detected from the isolates, which mediated a range of antibiotic resistance mechanisms, with deactivation and efflux potentially serving as the primary mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. This study revealed the diversity of A. hydrophila genotypes and the risk of antibiotic resistance in Sichuan, providing reference for scientific and effective control of A. hydrophila infection.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-023-01187-9.

Keywords: Aeromonas hydrophila, MLST, Antibiotic resistance phenotype, Antibiotic resistance gene, Aquatic animal

Introduction

The genus Aeromonas consists of oxidase-positive, facultative, anaerobic gram-negative bacteria that normally inhabit the aquatic environment. Depending on the physiological properties and hosts, they are divided into two large groups. The first group consists of non-motile species, represented by Aeromonas salmonicida. The other group includes motile aeromonads, with Aeromonas hydrophila as a typical representative [1].

A. hydrophila is a bacterium with a rod-shaped morphology commonly found in aquatic habitats [2]. It exhibits a wide temperature tolerance range, being able to survive in temperatures ranging from 0 to 45 °C [3]. This bacterium has been linked to various diseases in different fish species, such as zebrafish, salmonids, carp, milkfish, and channel catfish [4]. Examples of these diseases include red sore disease in bass and carp, as well as motile aeromonad septicemia in carp, tilapia, perch, catfish, and salmon [2]. Aeromonad septicemia is a very detrimental condition that poses significant threats to the aquaculture. It is characterized by a vast geographic spread and a prolonged duration of outbreaks, resulting in substantial economic losses. Despite the existence of many vaccines, there is still a lack of effective vaccination options for combating A. hydrophila infection within the aquaculture [5]. Consequently, antibiotics continue to be the primary method of therapy for this kind of illness. Nevertheless, owing to the misuse of antibiotics and the transmission of resistance genes [6], the development of antibiotic resistance in various types of bacteria has become a significant challenge worldwide [7]. Freshwater environments, being natural habitats vulnerable to antibiotic contamination, have emerged as focal points for horizontal gene transfer (HGT) of antibiotic resistance genes. The persistence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes in freshwater environments poses an elevated risk of infections caused by resistant pathogens [8]. A number of studies have shown that the antibiotic resistance of A. hydrophila is increasing, and its resistant strains show the characteristics of broad antibiotic resistance spectrum and high antibiotic resistance rate [9, 10]. The genus Aeromonas possesses a high level of genetic diversity among the species, and the taxonomy is complex due to the expanding number of new species and reclassification of the existing species [11].

The output of aquaculture in Sichuan in 2022 was 1.72 × 106 tons, making it the leader in southwest China, and the output value of aquaculture industry has reached 3.43 × 104 million [12], which plays an important role in poverty alleviation and rural revitalization. A. hydrophila is one of the most important bacteria harming Sichuan aquaculture industry, of which the genotype and antibiotic resistance are still unclear. It results in antibiotic misuse, which may seriously contaminate freshwater ecosystems with antibiotics. This study aimed to investigate molecular typing, antibiotic resistance phenotype, and resistance genes of A. hydrophila in Sichuan, hoping to provide reference for scientific and effective control of A. hydrophila infection.

Materials and methods

Bacterial isolation and identification

In this study, fishes that displayed symptoms of A. hydrophila infection were collected from several locations within the Sichuan province. Fishes were first sanitized with 70% alcohol and then dissected in the laboratory. Samples obtained from the liver, spleen, kidney, and ascites of each diseased fish were directly streaked onto Rimler-Shotts (RS) agar plates and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h. Yellow smooth round and opacity colony was selected for purification on LB agar plates incubated at 28 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, the isolated bacterium was identified by PCR analysis using specific primers (F1:5′-CGACGATCCCTAGCTGGTCT-3′; R1: 5′-GCCTTCGCCACCGGTAT-3′ and F2: 5′- AGTCTGCCGCCAGTGGC-3′; R2: 5′- CRCCCATCGCCTGTTCG-3′), which target the A. hydrophila-specific 16S rRNA (461 bp) and gyrB gene (144 bp) [13, 14]. All identified A. hydrophila were stored at − 80 °C in sterile balanced salt solution (BSS: 0.8% NaCl, 0.11% K2SO4, 0.135% NaH2PO4, 0.005% NaHCO3; pH 7.2) supplemented with 15% glycerol for further experiments.

Multi-locus sequence typing analysis

PCR amplification of six housekeeping genes (gyrB, groL, gltA, metG, ppsA, recA) was performed on all isolates according to findings of Martino et al. [15]. The PCR reaction mixture consisted of 25 μL, including 12.5 μL of SYBR Green PCR Master Mix, 8.5 μL of diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water, 1.0 μL of the forwarding primer, 1.0 μL of the reverse primer, and 2.0 μL of DNA. The following program conditions were used for the reactions: 5 min at 95 °C for 1 cycle, samples were amplified for 30 cycles at 95 °C for 5 min, fading fire for 15 s, followed by 72 °C for 10 min. The allelic profiles and sequence type (ST) of all house-keeping genes from A. hydrophila were determined and assigned using the PubMLST database (https://pubmlst.org/aeromonas). When the comparison outcomes lacked a matching full sequence type, re-upload the relevant data to the MLST database to apply for a new sequence type.

Antibiotic resistance profile (ARP) assay

Test on antibiotic susceptibility of A. hydrophila isolates was conducted against the disc diffusion method. A total of 20 antibiotics were utilized in this study. These antibiotics included imipenem (10 µg), ceftazidime (30 µg), cefoxitin (30 µg), amoxicillin (20 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), tobramycin (10 µg), nalidixic acid (30 µg), streptomycin (10 µg), kanamycin (30 µg), doxycycline (30 µg), tetracycline (30 µg), enrofloxacin (10 µg), levofloxacin (5 µg), ciprofloxacin (5 µg), co-trimoxazole (19 µg), sulfafurazole (300 µg), florfenicol (30 µg), clindamycin (2 µg), roxithromycin (15 µg), and polymyxin B (300 IU). The fresh bacterial solution was distributed uniformly over the solid MH agar plates. Subsequently, the drug-sensitive discs were affixed to the surface of the medium using a sterile forceps. The plates were incubated at 28 °C for 24 h. The resulting zone of inhibition was then assessed according to the guidelines provided by the CLSI-M100 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (28th edition). The obtained findings were categorized into three groups: sensitivity (S), intermediate (I), and resistance (R) (Table S1).

Antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) detection

Bacterial genomic DNA was extracted by using a DNA extraction kit. The concentration of DNA was determined by fluorometric analysis with a microplate reader (Spectramax M5, USA) using a QuantiFluor® dsDNA system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The concentrations of the sample at least 20 ng/μL were required. High-throughput qPCR reactions were performed by using the Wafergen SmartChip Real-time PCR system. In this project, a total of 80 primer sets were used, including 79 primers for the target ARGs and one for the 16S rRNA gene (Table S2). The PCR reaction mixture contained 1 × LightCycle 480SYBRGreenIMaster, 500 nM each primer, and DNA template. The following program conditions were used for the reactions: 10 min at 95 °C for 1 cycle, samples were amplified for 40 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 60 °C for 30 s. Three reactions were run in parallel for each sample. The PCR reaction mixture was added to the microwell chip by using a nano-upgrade multi-sample spotter (MSND) with the model of 96 (assays) × 54 (samples), and the qPCR reaction is performed on cycler. The results were then analyzed with SmartChip qPCR Software. Thirty-one cycles of CT value were set as the threshold value, and two or more of the three replicates were detected as judged to be detected positive.

Results

Isolation of A. hydrophila

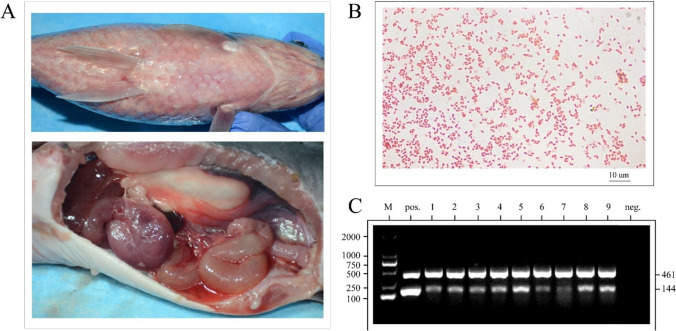

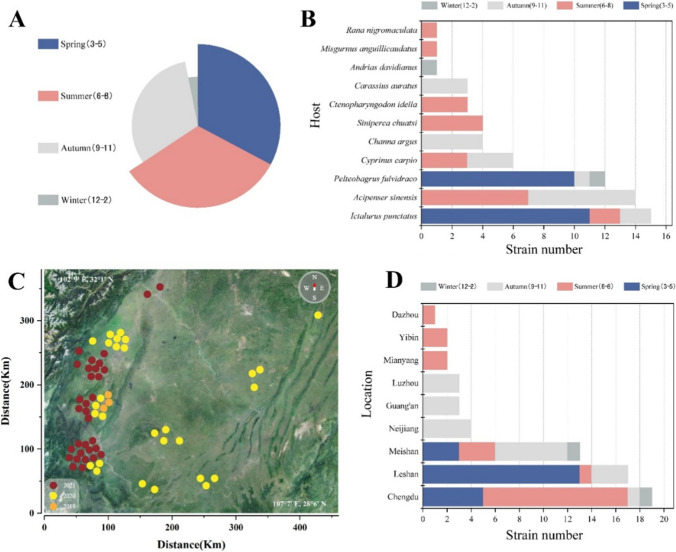

A total of 64 A. hydrophila strains were obtained from aquatic animals with hemorrhagic sepsis (Fig. 1), including Ictalurus punctatus, Acipenser sinensis, Pelteobagrus fulvidraco, Channa argus, Siniperca chuatsi, Ctenopharyngodon idella, Carassius auratus, Andrias davidianus, Misgurnus anguillicaudatus, and Rana nigromaculata during September 2019 to June 2021 from different locations in Sichuan Province (Fig. 2B, C). The prevalence of A. hydrophila in Ictalurus punctatus (23.44%), Acipenser sinensis (21.88%), and Pelteobagrus fulvidraco (18.75%) exhibited larger proportions compared to other host species (Fig. 2B). The present analysis revealed that A. hydrophila, which was obtained from Chengdu, constituted around 29.69% of the total isolates. Subsequently, Leshan accounted for 26.56% of the isolates, while Meishan represented 20.31% of the isolates (Fig. 2D). The winter isolation rate was seen to be 3.13%, a value that was found to be substantially lower compared to the isolation rates observed in previous seasons (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 1.

Pathological changes and identification of A. hydrophila. A Carassius auratus (top picture) has bleeding on its body, whereas Ictalurus punctatus (bottom image) has congestion, enteritis, and ascites. B The pink and short rod-shaped A. hydrophila can be seen under a microscope. C Results of a dual PCR on the 16S rRNA gene and the gyrB gene in A. hydrophila

Fig. 2.

Source statistics of 64 isolated A. hydrophila. A Period statistics of isolated strains. The rate of isolation throughout spring and summer was 32.81%, followed by autumn (31.24%), and winter (3.13%). B Host statistics of isolated strains. The isolation rate of A. hydrophila in Ictalurus punctatus was 23.44%, followed by Acipenser sinensis (21.88%), and Pelteobagrus fulvidraco (18.75%). C Geographic distribution of isolated strains. The locations of all isolates over the three years are shown on the map. D Location statistics of isolated strains. Chengdu, Leshan, and Meishan have high isolation rates, while the remaining areas have low isolation rates

Multi-locus sequence typing analysis of A. hydrophila

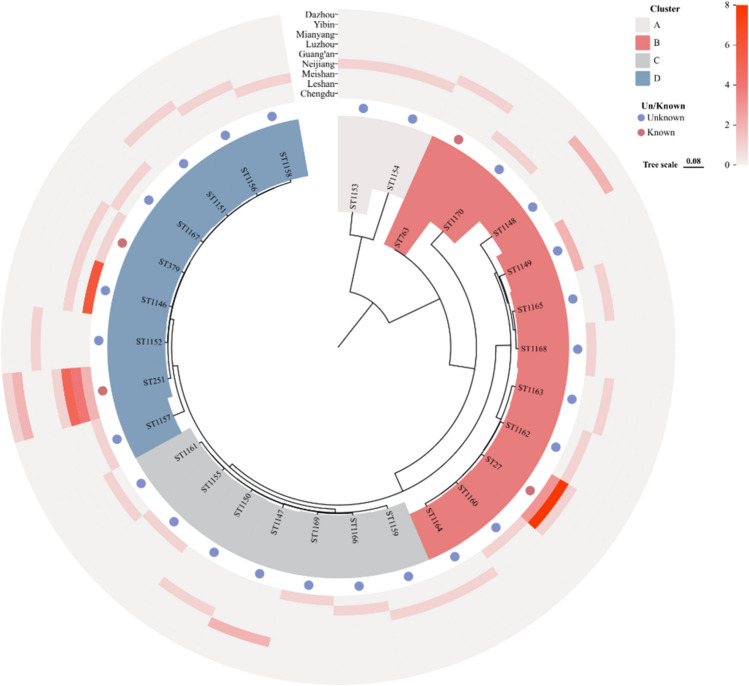

The analysis of the 64 isolates in this study was conducted using multi-locus sequence typing (MLST), resulting in the identification of 29 sequence types (ST) as shown in Table S3. The dataset comprises four distinct sequence types (STs), namely 15 ST251 types, 12 ST27 types, 2 ST379 types, and 1 ST763 type. A total of 25 novel sequence types (STs) were acquired by submitting samples to the online database located at http://pubmlst.org/aeromonas. Among them, there were 7 instances of ST1146, 2 instances of ST1147, 2 instances of ST1148, and 2 instances of ST1149. The other strains were classified as distinct individual ST types. The 29 sequence types (STs) were mostly grouped into four distinct clusters, with the recently identified STs exhibiting tight relationships with the previously known STs. The aforementioned findings indicate that A. hydrophila in the primary cultivation regions of Sichuan exhibited a range of sequence types (ST), with ST251 being the most prevalent kinds (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree based on 29 ST types of isolated strains (https://www.chiplot.online/tvbot.html). There were a total of 29 ST types, out of which only four ST types were known. These ST types were further categorized into four distinct clusters, namely A, B, C, and D. The graphic also depicted the distribution of each ST type in each location

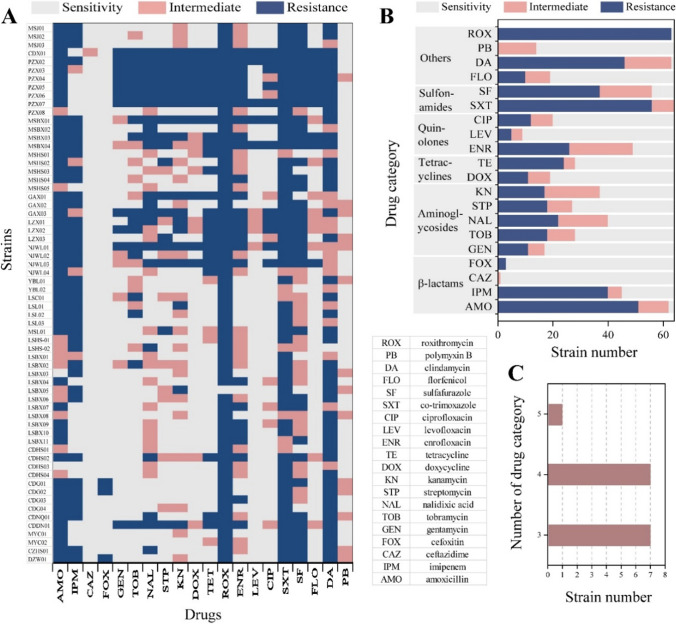

The ARP characteristic of A. hydrophila

The drug susceptibility testing revealed that A. hydrophila exhibited resistance to 18 out of the 20 drugs. Several strains obtained from the same batch exhibited comparable resistance to a specific medication (PZX02-07), but some shown significant variations (LSBX01-11) (Fig. 4A). The prevalence of roxithromycin-resistant bacteria is notably high, reaching 98.3%. This is followed by co-trimoxazole and sulfafurazole, both exhibiting resistance rates of 87.5%. Imipenem has a resistance rate of 80%, while amoxicillin and clindamycin exhibit resistance rates of 60% and 57.8% respectively (Fig. 4B). In addition, the results indicated that a significant proportion of strains (98%) exhibited sensitivity to ceftazidime followed by cefoxitin (95.3%), levofloxacin (85.9%), polymyxin B (78.1%), gentamicin (73.4%), doxycycline (70.3%), florfenicol (70.3%), ciprofloxacin (68.8%), streptomycin (57.8%), tobramycin (56.3%), and tetracycline (56.2%) (Fig. 4B). Fifteen strains of A. hydrophila exhibited resistance to dugs across a minimum of three categories (Fig. 4C). This observation suggests that these isolates have acquired the ability to resist several drugs, thereby demonstrating multidrug resistance.

Fig. 4.

The antibiotic resistance profiles of 64 isolated A. hydrophila. A Distribution of resistance in all A. hydrophila. The graphic presented the resistance of all isolates to each medication. B Statistics of the classification of 20 antibiotics. C Multidrug resistance of isolated strains. There were 7 strains with resistance to 3 drug categories, 7 strains with resistance to 4 drug categories, and 1 strain with resistance to 5 drug categories

The ARG characteristic of A. hydrophila

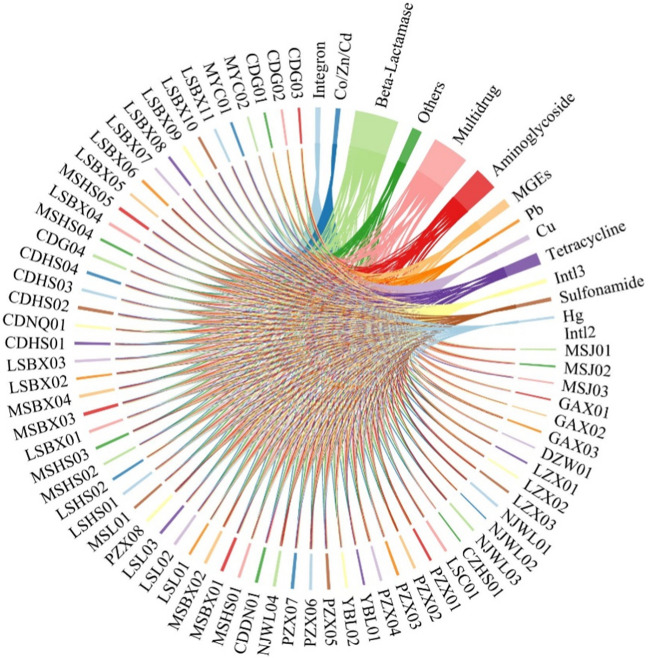

In this study, a total of 63 antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) were identified from the isolates. Among these ARGs, beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, multiple medicines, and tetracyclines were found to be present in a larger percentage (Fig. 5). All 64 isolates exhibited the presence of cphA-01, fox5, aac(6’)I1, mepA, intI-1, and ISCR1. Moreover, intI-1 and cphA-01 were not only discovered in all isolated strains, but also shown a significantly greater prevalence compared to other genes. The findings indicated that there was considerable variation in resistance genotypes across different strains, demonstrating a high level of diversity.

Fig. 5.

Circle diagram of resistance gene categories and strains. The resistance gene categories seen in this study, including beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, multiple medicines, tetracyclines, mobile genetic elements (MGEs), and resistance to Pb and Cu, among others. Beta-lactam antibiotics, aminoglycosides, a combination of medicines, and tetracyclines were administered in a greater percentage

Discussion

As a conserved sequence shared by prokaryotes, the 16S rRNA sequence has a fabulous classification effect [16]. Besides, gyrB as one of the conserved housekeeping genes of A. hydrophila also has an excellent effect on identification [17]. Combining RS medium and double PCR identification based on 16S rRNA and gyrB, we successfully isolated 64 strains of A. hydrophila from major aquaculture areas in Sichuan Province during September 2019 to June 2021. A. hydrophila is a conditionally pathogenic bacterium widely present in nature, and has strong pathogenicity to freshwater fish when the water temperature is suitable. Regarding the period of isolation, our findings indicated that the rate of isolation during winter was notably reduced compared to other seasons. This observation aligns with the established result that water temperature may have an influence on the development and reproductive condition of A. hydrophila [18]. In terms of geographical distribution, the strains exhibited a higher prevalence in Chengdu, Leshan, and Meishan, displaying distinct features of localized outbreaks.

The examination of genotypes may facilitate the investigation of the cloning association among different strains, hence enabling the prevention and management of epidemiological bacteria. This approach has significant value in the realm of bacterial epidemiology research. The need for more precise characterization of isolates has prompted the emergence of many strain-typing techniques, among which multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) has gained prominence as the preferred approach for typing numerous species [19]. This study included the analysis of 64 strains of A. hydrophila, which were categorized into 29 sequence types (ST) across different regions. Notably, only 4 ST types were identified in this particular study, therefore contributing to the existing database of Aeromonas multi-locus sequence typing (MLST). Furthermore, these findings shed light on the diverse and intricate nature of A. hydrophila pathogenicity in the Sichuan region. The comparative analyses of sequence type ST 251 and other ST groups revealed that there were higher numbers of virulence factors in ST251 than in other STs group [20]. In this study, ST251 type was the main ST type in isolated strains, and it also was the main epidemic strain in the aquaculture region of central China [21]. Furthermore, the ST251 clonal group was likely to be responsible for the motile Aeromonad septicemia outbreaks in both China and the southeastern United States [22]. Multiple lines of evidence indicated US catfish and Asian carp isolates of A. hydrophila affiliated with ST251 shared a recent common ancestor [23]. According to the Aeromonas database of PubMLST, ST27 and ST763 type were respectively found in Italy and Spain, and both of them were not visually related to our strains. A human case suggested that A. hydrophila could cause disseminated infection in immunocompetent individuals [24], and this might support the long-distance spread of germs. The results obtained from MLST typing revealed the presence of identical genotypes across farms located in distinct regions. Additionally, it was observed that pathogens isolated from different ponds and farms, albeit collected simultaneously, exhibited distinct molecular profiles. These findings provide evidence of significant genetic diversity within A. hydrophila populations in the primary aquaculture regions of Sichuan.

The drug susceptibility testing revealed that the strains isolated from various locations of Sichuan had elevated resistance rates to amoxicillin, imipenem, roxithromycin, clindamycin, and sulfonamides. Moreover, the prevalence of resistance to florfenicol, tetracyclines, and quinolones ranged from 0 to 40%, while the isolated strains in Egypt had a high resistance toward gentamicin and a high sensitivity toward amoxicillin [25]. The antibiotic susceptibility investigation of A. hydrophila in Indonesia reported that all samples were susceptible to ciprofloxacin and imipenem [26], which was quite different from our results. In contrast to low temperatures, it was observed that A. hydrophila exhibited greater virulence at elevated temperatures [27]. The findings of this study indicated that the rates of resistance observed in strains isolated during the winter season were comparatively lower when compared to those observed in other seasons. On the one hand, it might be connected to the elevation of the expression of the strain’s antibiotic resistance genes once the water temperature rises [28]. On the other hand, it was plausible that this phenomenon might be attributed to the overutilization of antibiotics as a consequence of recurrent illnesses during the warmer months. Moreover, it should be noted that the resistance shown by isolates is subject to regional variations, as well as variations between hosts even within the same location. These differences may be attributed to the diverse aquatic conditions and the accompanying approaches to drug management. With the advent of the antibiotic era, the overuse and inappropriate application of antibiotics have driven the rapid emergence of multidrug-resistant pathogens [29]. Our study revealed that the 15 isolates obtained from Sichuan had pronounced multidrug resistance, with the majority of them displaying resistance to drugs belonging to 3–4 categories. In Northern Vietnam, the overall multiple antibiotic resistance index ranged from 0.13 to 0.88, corresponding to 100% A. hydrophila isolates resistant to at least two antibiotics [30]. In South Korea, 18.6% of A. hydrophila isolates showed presumptive multidrug-resistant phenotypes [31].

Various types of resistance genes identified from A. hydrophila MX16A revealed multiple resistance mechanisms, including enzyme inactivation, gene mutation, and active effusion [32]. In this study, a total of 63 resistance genes were identified among 64 isolates, facilitating the operation of 6 distinct resistance mechanisms. The isolated strains mostly had resistance genes associated with deactivation, followed by efflux-mediated reduction of drug concentrations as a means to counteract drug effects. Additionally, they were capable of evading drug effects via mobile genetic elements (MGEs), protective mechanisms, multidrug resistance (MDR), and antibiotic target alteration. The presence of cphA-01 was seen in all strains examined in this study, which could improve the resistance of A. hydrophila to aztreonam, ceftriaxone, and cefepime [33]. The high detection rate of cphA-01 may be attributed, in part, to the mutation and development of cphA under the short-term selection pressure of imipenem [34]. This phenomenon might potentially enhance bacterial resistance. Previous research has shown that intI-1was the most common integrator [33], and our current investigation provided further support for this assertion. Our present investigation observed a notable prevalence of resistance genes associated with β-lactams and aminoglycosides. These discovered resistance genes mostly encoded enzymes responsible for deactivating β-lactams and aminoglycosides, thereby elucidating the prominent role of deactivation mechanisms in conferring resistance. Moreover, there was a notable prevalence of tetracycline resistance genes, which exhibited a substantial capacity to express efflux proteins responsible for drug expulsion. This observation provides a plausible explanation for the higher occurrence of efflux mechanisms.

There was a certain correlation between resistance genes and antibiotic resistance phenotypes. The observed detection rate of multidrug resistance genes exceeded 70%. These genes, namely mepA, acrR-01, emrD, floR, marR-01, mexF, and oprD, provide an explanation for the observed multidrug resistance outcomes. The resistance rates of clindamycin and roxithromycin exhibited a high degree of concordance with the detection rates of their respective resistance genes. Nevertheless, a considerable number of medications had a resistance genotype that did not show as a resistance phenotype. As an example, the prevalence of resistance to florfenicol was found to be 15.6%, while the identification rate of the resistance gene (floR) was seen to be 70.3%. Similarly, the resistance rate to imipenem was determined to be 62.5%, with a corresponding detection rate of resistance genes (oprD) at 98.4%. Differences in resistance phenotypes and resistance genes might be related to the gene expression levels and bacteria’s environment [28, 35, 36]. The freshwater environment has become the place where resistance evolution occurs, in which antibiotic-resistant bacteria and resistance genes could not be completely eradicated by natural processes of degradation or dilution [8]. In Germany, sulfonamides, fluoroquinolones, and macrolide were reported the most frequently detected antibiotics in wastewater [37]. Due to the fast mobility, low biodegradability, and low affinity to soil sorption [38], sulfamethoxazole became the most detected antibiotic in groundwater among all the sulfonamides [39]. The present study determined that doxycycline, ciprofloxacin, and levofloxacin were the rare antibiotics that exhibited efficacy against the isolated strains, while also demonstrating low levels of detection for antibiotic resistance genes in Sichuan.

Conclusions

In this study, 64 strains of A. hydrophila obtained from aquatic animals in the Sichuan province of China. Twenty-nine sequence types (STs) were identified and categorized, with the inclusion of 25 novel ST types. Fifteen isolates exhibited noteworthy levels of multidrug resistance. A total of 63 resistance genes were identified across all isolated strains, mostly associated with the processes of antibiotic resistance deactivation and efflux. In summary, this study has shown the wide range of genotypes and the potential for antibiotic resistance in A. hydrophila in aquatic animals of Sichuan.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank all authors who kindly provided their hard work in the program.

Author contribution

Kun Peng: writing, methodology, investigation. Mengzhu Chen: investigation, methodology, formal analysis. Yilin Wang: methodology, investigation. Ziqi Tian: investigation, formal analysis. Longjun Deng: investigation, data curation. Tiancai Li: data curation, formal analysis. Yang Feng: methodology, data curation. Ping Ouyang: project administration, resources. Xiaoli Huang: conceptualization, methodology. Defang Chen: writing — review and editing. Yi Geng: funding acquisition, supervision. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version. Kun Peng and Mengzhu Chen contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This research was supported by the Sichuan Innovation Team Project of Agricultural Industry Technology System (SCCXTD-15) and Fish Diseases Prevention and Control Project of JPDC (No.23XB0027).

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article that are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

All animal procedures were conducted by the Animal Experiment General Requirement in China (record number GB/T 35823–2018) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Sichuan Agricultural University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Kun Peng and Mengzhu Chen contributed to this work equally.

References

- 1.Stratev D, Odeyemi OA. Antimicrobial resistance of Aeromonas hydrophila isolated from different food sources: a mini-review. J Infect Public Health. 2016;9:535–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janda JM, Abbott SL. The genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, pathogenicity, and infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:35–73. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00039-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pianetti A, Battistelli M, Citterio B, Parlani C, Falcieri E, Bruscolini F. Morphological changes of Aeromonas hydrophila in response to osmotic stress. Micron. 2009;40:426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rashidian G, Boldaji JT, Rainis S, Prokic MD, Faggio C. Oregano (Origanum vulgare) extract enhances zebrafish (Danio rerio) growth performance, serum and mucus innate immune responses and resistance against Aeromonas hydrophila challenge. Animals (Basel) 2021;11:299. doi: 10.3390/ani11020299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaur B, Naveen Kumar BT, Tyagi A, AdmaneHoleyappa S, Singh NK. Identification of novel vaccine candidates in the whole-cell Aeromonas hydrophila biofilm vaccine through reverse vaccinology approach. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2021;114:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2021.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collignon P, Beggs JJ, Walsh TR, Gandra S, Laxminarayan R. Anthropological and socioeconomic factors contributing to global antimicrobial resistance: a univariate and multivariable analysis. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2018;2:e398–e405. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elbehiry A, Marzouk E, Abdeen E, Al-Dubaib M, Alsayeqh A, Ibrahem M, Hamada M, Alenzi A, Moussa I, Hemeg HA. Proteomic characterization and discrimination of Aeromonas species recovered from meat and water samples with a spotlight on the antimicrobial resistance of Aeromonas hydrophila. Microbiologyopen. 2019;8:e782. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nnadozie CF, Odume ON. Freshwater environments as reservoirs of antibiotic resistant bacteria and their role in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. Environ Pollut. 2019;254:113067. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khor WC, Puah SM, Koh TH, Tan J, Puthucheary SD, Chua KH. Comparison of clinical isolates of Aeromonas from Singapore and Malaysia with regard to molecular identification, virulence, and antimicrobial profiles. Microb Drug Resist. 2018;24:469–478. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2017.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramadan H, Ibrahim N, Samir M, Abd El-Moaty A, Gad T. Aeromonas hydrophila from marketed mullet (Mugil cephalus) in Egypt: PCR characterization of beta-lactam resistance and virulence genes. J Appl Microbiol. 2018;124:1629–1637. doi: 10.1111/jam.13734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau TTV, Tan JMA, Puthucheary SD, Puah SM, Chua KH. Genetic relatedness and novel sequence types of clinical Aeromonas dhakensis from Malaysia. Braz J Microbiol. 2020;51:909–918. doi: 10.1007/s42770-020-00239-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.FISHERIES BO . China fishery statistics yearbook. China Agriculture Press; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicholson P, Mon-on N, Jaemwimol P, Tattiyapong P, Surachetpong W (2020) Coinfection of tilapia lake virus and Aeromonas hydrophila synergistically increased mortality and worsened the disease severity in tilapia (Oreochromis spp.). Aquaculture 520. 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734746

- 14.Persson S, Al-Shuweli S, Yapici S, Jensen JN, Olsen KE. Identification of clinical aeromonas species by rpoB and gyrB sequencing and development of a multiplex PCR method for detection of Aeromonas hydrophila, A. caviae, A. veronii, and A. media. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:653–656. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01963-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martino ME, Fasolato L, Montemurro F, Rosteghin M, Manfrin A, Patarnello T, Novelli E, Cardazzo B. Determination of microbial diversity of Aeromonas strains on the basis of multilocus sequence typing, phenotype, and presence of putative virulence genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:4986–5000. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00708-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Church DL, Cerutti L, Gurtler A, Griener T, Zelazny A, Emler S. Performance and application of 16S rRNA gene cycle sequencing for routine identification of bacteria in the clinical microbiology laboratory. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020;33:e00053–e119. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00053-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez-Bravo A, Figueras MJ. An update on the genus Aeromonas: taxonomy, epidemiology, and pathogenicity. Microorganisms. 2020;8:129. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8010129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sautour M, Mary P, Chihib NE, Hornez JP. The effects of temperature, water activity and pH on the growth of Aeromonas hydrophila and on its subsequent survival in microcosm water. J Appl Microbiol. 2003;95:807–813. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maiden MC, Jansen van Rensburg MJ, Bray JE, Earle SG, Ford SA, Jolley KA, McCarthy ND. MLST revisited: the gene-by-gene approach to bacterial genomics. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:728–736. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Awan F, Dong Y, Liu J, Wang N, Mushtaq MH, Lu C, Liu Y. Comparative genome analysis provides deep insights into Aeromonas hydrophila taxonomy and virulence-related factors. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:712. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5100-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang X, Yang W, Wu H, Gong X, Li A. Multilocus sequence typing revealed a clonal lineage of Aeromonas hydrophila caused motile Aeromonas septicemia outbreaks in pond-cultured cyprinid fish in an epidemic area in central China. Aquaculture. 2014;432:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pang M, Jiang J, Xie X, Wu Y, Dong Y, Kwok AH, Zhang W, Yao H, Lu C, Leung FC, Liu Y. Novel insights into the pathogenicity of epidemic Aeromonas hydrophila ST251 clones from comparative genomics. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9833. doi: 10.1038/srep09833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasmussen-Ivey CR, Hossain MJ, Odom SE, Terhune JS, Hemstreet WG, Shoemaker CA, Zhang D, Xu DH, Griffin MJ, Liu YJ, Figueras MJ, Santos SR, Newton JC, Liles MR. Classification of a hypervirulent Aeromonas hydrophila pathotype responsible for epidemic outbreaks in warm-water fishes. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1615. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nikiforov I, Goldman J, Cheriyath P, Vyas A, Nookala V. Aeromonas hydrophila sepsis associated with consumption of raw oysters. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2014;2014:163040. doi: 10.1155/2014/163040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saleh AER, Younis G. Virulent and multiple antimicrobial resistance Aeromonas hydrophila isolated from diseased Nile tilapia fish (Oreochromis niloticus) in Egypt with sequencing of some virulence-associated genes. Biocontrol Sci. 2021;26:167–176. doi: 10.4265/bio.26.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fikri F, Wardhana DK, Purnomo A, Khairani S, Chhetri S, Purnama MTE. Aerolysin gene characterization and antimicrobial resistance profile of Aeromonas hydrophila isolated from milkfish (Chanos chanos) in Gresik, Indonesia. Vet World. 2022;15:1759–1764. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2022.1759-1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schubert RH, Matzinou D. Temperature as an environmental factor influencing the pathogenicity of Aeromonas hydrophila. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1990;273:327–331. doi: 10.1016/S0934-8840(11)80436-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gong Z, Li J, Luo H, Zhan D, Liu X, Gao C, Huang J, Qian Y, Song Y, Quan W, An S, Tian Y, Hu Z, Sun J, Yuan H, Jiang R. Low-temperature laminar flow ward for the treatment of multidrug resistance Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia. Nat Public Health Emergency Collection. 2020;39:877–887. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03790-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medina E, Pieper DH. Tackling threats and future problems of multidrug-resistant bacteria. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2016;398:3–33. doi: 10.1007/82_2016_492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nhinh DT, Le DV, Van KV, Huong Giang NT, Dang LT, Hoai TD. Prevalence, virulence gene distribution and alarming the multidrug resistance of Aeromonas hydrophila associated with disease outbreaks in freshwater aquaculture. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021;10:532. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10050532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woo SJ, Kim MS, Jeong MG, Do MY, Hwang SD, Kim WJ. Establishment of epidemiological cut-off values and the distribution of resistance genes in Aeromonas hydrophila and Aeromonas veronii isolated from aquatic animals. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022;11:343. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics11030343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo Y, Zeng C, Ma C, Cai H, Jiang X, Zhai S, Xu X, Lin M. Comparative genomics analysis of the multidrug-resistant Aeromonas hydrophila MX16A providing insights into antibiotic resistance genes. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:1042350. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.1042350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qiuli He GM, Liang M. Analysis of drug resistance of Aeromonas parenterinal to β-lactam drugs in a hospital in Shaoxing. Int J Epidemiol Epidemiol. 2019;46:5. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong X, Shi P, Liu W, Bai J, Bian L. Metallo-beta-lactamase CphA evolving into more efficient hydrolases through gene mutation is a novel pathway for the resistance of super bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022;106:2471–2480. doi: 10.1007/s00253-022-11879-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McMahon MA, Xu J, Moore JE, Blair IS, McDowell DA. Environmental stress and antibiotic resistance in food-related pathogens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:211–217. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00578-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kolář M, Urbánek K, Látal T. Antibiotic selective pressure and development of bacterial resistance. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;5:357–531. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(01)00317-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Voigt AM, Faerber HA, Wilbring G, Skutlarek D, Felder C, Mahn R, Wolf D, Brossart P, Hornung T, Engelhart S, Exner M, Schmithausen RM. The occurrence of antimicrobial substances in toilet, sink and shower drainpipes of clinical units: a neglected source of antibiotic residues. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2019;222:455–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boy-Roura M, Mas-Pla J, Petrovic M, Gros M, Soler D, Brusi D, Mencio A. Towards the understanding of antibiotic occurrence and transport in groundwater: findings from the Baix Fluvia alluvial aquifer (NE Catalonia, Spain) Sci Total Environ. 2018;612:1387–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Apreja M, Sharma A, Balda S, Kataria K, Capalash N, Sharma P. Antibiotic residues in environment: antimicrobial resistance development, ecological risks, and bioremediation. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29:3355–3371. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-17374-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article that are available from the corresponding author upon request.