Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted a need to change traditional teaching methods. This study was conducted to evaluate the educational quality of a blended anatomy course and measure student satisfaction and knowledge after completing the course.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

Tyler's model was used to develop a new blended curriculum. The study guide for this curriculum was also developed using Association for Medical Education in Europe guide no. 16. A quasi-experimental study compared educational quality, students' satisfaction, and students' satisfaction using Students' Evaluations of Educational Quality (SEEQ), Borim Nejad's satisfaction survey, and multiple choice questions, respectively. Independent t-tests and Chi-square were used to compare the groups.

RESULTS:

A total of 122 students participated in this study, 62 and 60 in the intervention and control groups, respectively. The satisfaction score was significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group (40.6 versus 38.6, P value = 0.03). The score of SEEQ was not significantly different (91.9 versus 91.08, P value = 0.52), but the subscales of learning (17.23 versus 16.32, P = 0.01), group interaction (16.87 versus 18.1, P = 0.01), and breadth (17.73 versus 16.65, P = 0.02) were significant. The knowledge score was also significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group (18.13 versus 16.68, P value < 0.001).

CONCLUSION:

Using blended learning approaches for anatomy courses can increase students' satisfaction, improve the learning and breadth of educational quality subscales, but worsen group interaction. Although this study shows improvement in medical students' knowledge, further studies are needed because of the limitations of this study.

Keywords: Anatomy, COVID-19, education, learning, medical education

Introduction

Since the last days of 2019, the world has faced a new challenge: the COVID-19 pandemic. COVID-19 is a virus that was first reported in China, causing pneumonia.[1] This virus quickly spread in a short time all over the world and caused a new pandemic.[2] Iran is also one of the countries that was soon affected by the virus. This pandemic changes people's lifestyles, like social distancing, wearing masks, and lockdowns. Undergraduate medical education is also affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Being in populated indoor sites is one of the major causes of COVID-19 infection.[3] As a result, a big challenge emerges for universities and teachers to create a change in teaching methods.

Blended learning is a style of education in which students learn via electronic and online media and traditional face-to-face teaching.[4] This method allows students to take advantage of technologies not previously provided by textbooks.[5] Blended learning is more flexible than traditional education and more responsive than e-learning alone.[6] Moreover, similar to e-learning, blended learning is subject to no time and space restrictions.[5] In fact, blended learning utilizes the advantages of both traditional and online methods but circumvents their restrictions.

A meta-analysis from the US Department of Education showed that blended learning is the best educational approach because it can utilize the advantages of both traditional and online approaches but circumvent their restrictions.[7] A blended course has benefits like: increases the efficiency of the students,[8] is acceptable among students and teachers,[9] increases students motivation,[10] and has a customizable learning environment.[11]

Anatomy is one of the basic sciences courses for medical students and a prerequisite to clinical courses such as surgery, orthopedics, neurosurgery, and radiology. Considering the extensive complexities of human anatomy and the widespread use of paraclinical examinations such as plain radiographs, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in clinical settings, traditional education approaches usually face many limitations in teaching this course. Therefore, the application of technological methods and blended learning programs can help transform the process of teaching human anatomy and radiography, CT, and MRI stereotypes.[12]

All these advantages of blended courses and anatomy courses' characteristics make a blended-learning course a favorable choice in the COVID-19 pandemic, but implementing a blended course also needs some requirements.[13,14]

A blended learning program's requirements include high-speed and stable internet access for all students, hardware facilities for content creation, an appropriate learning management system (LMS) for content presentation, and proper hardware facilities for content display.

Technological developments, increased internet users, easier access to high-speed internet, and opening of more virtual education centers in Iran have removed the most critical barriers to applying blended learning in Iranian universities.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic affected the whole world in a short time, in most universities, the change in educational programs was done without regard to curriculum planning principles. However, because the virtualization process of this course began before COVID-19, this study has the novelty of using a scientific approach to create a blended course. Moreover, using a blended learning method for current medical curriculums has not been extensively investigated in Iran, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has highlighted the need for innovative teaching methods. As a result, this study aims first to design a blended course based on the anatomy and radiology references, then implement the course, and finally evaluate students' satisfaction, educational quality, and knowledge after participating in the course.

Materials and Methods

Design and implementation

The Anatomy Department at the Medical University of Isfahan (MUI) began implementing blended learning methods for its courses 12 months prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, recognizing the many advantages of this approach. At that time, among the five anatomy courses for medical students, gastrointestinal (GI) system anatomy was chosen for this transformation. This course includes eight sessions. For curriculum development, Tyler model was used. A needs assessment was done at the first step. Oral interviews with some anatomy faculty members, general practitioners, and medical interns were done, and their comments were gathered. After that, the objectives and goals of each session were written. For the contents, the references introduced by the ministry of health and medical education were reviewed, and anatomy faculty members chose the contents. The online content are presented to students in the form of electronic texts and multimedia content.

Electronic contents are also presented by using an online study guide. Using an open-source Content Management System, Drupal, anatomy.mui.ac.ir was launched as an online study guide. The online study guide for the anatomy course was developed based on Association for Medical Education in Europe guide No. 16. All audio and video files were recorded in the studio of the virtual education center of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, compiled based on Shareable Content Object Reference Model (SCORM) standards, and uploaded to the online study guide. To present the radiology, CT, and MRI stereotypes, appropriate samples were extracted from the Picture Archiving and Communication System of Al-Zahra and Kashani hospitals, prepared using HTML, CSS, and JS, and provided to students through a leaflet library.

Evaluation

The evaluation was done by a quasi-experimental interventional study that aimed to compare the effectiveness of traditional and blended learning approaches to teaching anatomy. The participants were all medical students at MUI taking the anatomy course in the first and second semesters of the academic year 2019–2020; students in the first semester who were educated by the traditional face-to-face method were regarded as the control group, and those in the second semester who were educated by the blended method formed the intervention group. The students who dropped the course or did not participate in the final exam were excluded from the study. For the evaluation phase, Students' Evaluation of Educational Quality (SEEQ), Students' satisfaction, and students' knowledge were measured and compared between groups.

Student evaluation of educational quality (SEEQ)

The Marsh' SEEQ was employed to measure student evaluation of the teaching quality. This questionnaire consists of 21 items in 6 subscales: learning, enthusiasm, group interaction, individual rapport, breadth, and examinations/assignments. The items are scored based on a five-point Likert scale, from very good (5) to very bad (1). The reliability of this questionnaire was confirmed by a sample of Iranian students. In this study, Cronbach's alpha for subscales ranged between 0.82 and 0.88 and was equal to 0.91 for the whole questionnaire.[15,16] Scores of 0–21, 22–42, 43–63, 64–84, and over 84 on this questionnaire indicate very poor, poor, medium, good, and very good quality of teaching, respectively.

Student satisfaction with the course

Borim Nejad's questionnaire was used to measure students' satisfaction with the training course. This questionnaire consisted of 16 items scored based on a three-point Likert scale (totally, somewhat, and at all). It measures satisfaction with the teaching method through questions such as “I gained practical knowledge and skills during this training course.” Scores of 0–16, 17–32, and over 32 on this questionnaire indicate low, moderate, and high levels of satisfaction, respectively.

Student knowledge

The students took an multiple choice question (MCQs) exam with 50 questions to evaluate the educational content provided to both groups. The questions were extracted from the question bank of the department, and a panel of experts qualitatively evaluated their face validity and content validity.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUI.MED.REC.1397.251). The Helsinki statement was followed throughout the study, and all data were managed anonymously.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package of Social Science software (SPSS version 26.0, IL, Chicago, USA). Mean ± standard deviation (SD) and Frequency were used to report categorical and continuous variables, respectively. To compare the continuous and categorical variables between two groups of case/intervention, independent t-test and a Chi-squared test were used, respectively.

Results

Design and implementation

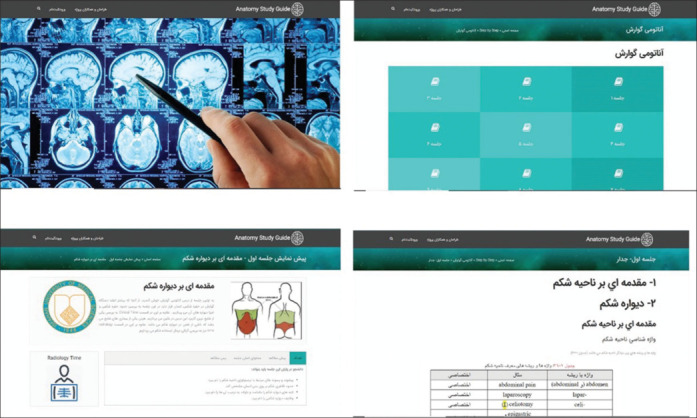

The anatomy course's electronic content, based on SCORM standards, was recorded in eight separate sessions in the Virtual Education Center of MUI and uploaded on the online study guide website. The online study guide was also developed on Drupal (it is now available at http://anatomy.mui.ac.ir/) [Figure 1]. Two sessions of face-to-face traditional learning were also held. One at the beginning of the semester and one in the middle of the semester.

Figure 1.

Screenshots of anatomy online study guide

Evaluation

A total of 122 students participated in this study: 60 in the control group and 62 in the intervention group. The demographic information of the participants is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of Demographics, Students Satisfaction Scores, Educational Quality Scores and its Subscales, and Knowledge Scores between the Intervention and Control Groups

| Variables | Intervention group | Control group | P | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | 20.84±1.86 | 20.33±0.87 | 0.06 | ||

| Gender (male) | 28 of 62 (45%) | 26 of 60 (43%) | 0.84 | ||

| GPA | 16.10±1.86 | 16.33±1.78 | 0.49 | ||

| Borim Nejad’s Satisfaction Survey | |||||

| Satisfaction score | 40.6±6.17 | 38.59±4.45 | 0.034 | 0.16 | 4.00 |

| Student Evaluation of Educational Quality (SEEQ) | |||||

| Total Score | 91.9±6.1 | 91.08±7.81 | 0.52 | -1.69 | 3.32 |

| Learning | 17.23±1.64 | 16.32±2.22 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 1.61 |

| Enthusiasm | 9.44±0.72 | 9.48±0.68 | 0.7 | -0.3 | 0.2 |

| Group interaction | 16.87±3.16 | 18.1±1.94 | 0.01 | -2.17 | -0.29 |

| Individual rapport | 13.63±1.7 | 13.68±1.55 | 0.85 | -0.64 | 0.53 |

| Breadth | 17.73±1.91 | 16.65±3.12 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 2.00 |

| Examinations/assignments | 17.02±2.23 | 16.85±2.48 | 0.7 | -0.69 | 1.01 |

| Knowledge Score | |||||

| MCQ Score | 18.13±2.05 | 16.68±2.30 | <0.001 | 0.68 | 2.23 |

The satisfaction score was 40.6 ± 6.17 for the intervention group and 38.59 ± 4.45 for the control group. The difference between the satisfaction scores of these groups was statistically significant (P = 0.03). The teaching quality was measured in 6 subscales of learning, enthusiasm, group interaction, individual rapport, breadth, and examinations/assignments. Overall, the two groups did not show a significant difference in the SEEQ score (P = 0.52). However, the intervention group had significantly higher scores in the subscales of learning and breadth, while the control group scored higher in the group interaction subscale. The detailed results are shown in Table 1.

The final examination was performed for both groups at the end of the semester using an MCQ test. Due to the limitations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the final examination for the intervention group was held online (those in the control group had taken a face-to-face exam). The final score of the intervention group was significantly higher (18.13 ± 2.05 versus 16.68 ± 2.30, P value ≤ 0.001).

Discussion

Due to students' everyday use of technology, this study in the design and implementation parts sought to provide suitable infrastructure to represent anatomy courses virtually along with face-to-face education. Producing online content for a GI anatomy course with a platform to represent it resulted from two parts of design and implementation, which are now available via anatomy.mui.ac.ir and can be used for blended and virtual learning. During the COVID-19 pandemic, distance learning used was widely, so it seems that in the post-COVIID-19 era, as students return to physical classrooms, the trend of using blended learning will continue.[17] There are many studies on the efficiency of using technology in teaching. For example, Morris et al.,[18] by reviewing the study process of students in a three-year interval, concluded that, considering the easier accessibility to resources with the help of tablets and smartphones, the amount of students' use of references and textbooks in their neuroanatomy course increased. In another article published by Leung et al.,[19] it is represented that the most used references for anatomy students are anatomy teaching websites.

In the evaluation part, this study indicated that using virtual learning with in-person learning can increase students' satisfaction in comparison to the traditional methods of teaching. Increased satisfaction with blended learning courses has been reported not only in the field of medical sciences but also in other fields. For instance, Wang et al.,[20] Stefanovic and Klochkova,[21] and Sucaromana[22] have shown that blended learning leads to increased satisfaction among English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students.

Numerous studies have also been conducted in the field of medical sciences regarding student satisfaction with blended learning, which have ultimately led to the publication of meta-analysis.

In the meta-analysis published by Li et al.,[23] by studying eight studies on nursing students, it was also determined that using combined learning increases students' level of satisfaction with an educational course. Furthermore, another meta-analysis involving 25 studies and 2706 participants has shown that blended learning leads to increased satisfaction among nursing students.[24] Although the articles mentioned have all reported increased student satisfaction with blended learning, it should be noted that blended courses can also lead to dissatisfaction. For example, both studies by Roff and Fu have concluded that the technology used and the accessibility to online resources can be a reason for students' dissatisfaction.[25,26] In our study, all materials were presented on an online study guide, allowing students to use any platform for learning. Furthermore, considering the increasing daily use of mobile devices, all pages were designed to be mobile-friendly to ensure readability and accessibility. Not only the features of a course but also the characteristics of the participants can affect students' satisfaction with a blended learning course. Individual factors such as age, digital literacy, and socioeconomic status can affect the students' satisfaction.[27,28]

In our study, the age of students had no significant differences, and both groups are classified as millennials. This can justify high satisfaction in our intervention group, but it should be considered that, unlike the Y and Z generations, we face people who have less dependency on the digital world in the X generation. Thus, when using virtual learning, the age of the audience should be considered.[29]

Although digital literacy increases with the passing of generations too, it should be noted that it is also different among people of one generation, which can affect people's satisfaction with this type of learning method.

Another factor that affects students' satisfaction with combined learning is socioeconomic status. For instance, during the coronavirus epidemic, Abbasi et al.[28] in a study indicated that students are more satisfied with virtual learning in developed countries than in less developed countries. In fact, proper equipment and infrastructure are essential factors that affect students' satisfaction with this learning method.[30]

The teaching quality score from the students' perspective in the two groups of control and intervention had no significant differences, but it was observed that blended learning positively affects some aspects of teaching, such as breadth and learning. On the other hand, using virtual learning reduces the possibility of group interaction with other students. Accordingly, it limits some learning methods that are based on group work and interaction with each other. Many similar studies indicate that using combined learning increases the comprehensiveness of courses and consequently increases teaching quality. For instance, an article published by Gould et al.[31] on an online educational tool in anatomy determined that, concerning comprehensiveness, this educational tool is very useful for the course and exam preparation. In another article published by Mansouri et al.,[32] which is a qualitative study to examine the features of anatomy software, comprehensiveness is also one of the most important features. The ability to use multimedia content, 3D models, the availability of standard content, and all-time accessibility can be considered the most important reasons for improving breadth and learning with this teaching method.

Our study did not indicate a significant difference in the enthusiasm score between the groups. Adding an online part to the traditional teaching methods can come with challenges for instructors. These challenges include instructors' interest, preparations, and teaching styles.[33,34]

As a result, it is important to consider that the successful transformation to a blended learning program relies on the characteristics of the instructor.[35] An article published during the coronavirus epidemic also mentioned this issue that technology acceptance by professors is one of the key elements of e-learning.[36] Although because of the pandemic and lockdowns these barriers to teachers' enthusiasm are inevitable, it is essential to keep in mind that universities may face such situations in the future. As a result, attention to the characteristics of teachers, such as digital literacy and familiarity with virtual teaching tools, is essential in selecting their faculty members.

In our study, the course instructor had a history of using digital educational aids for about 15 years, and therefore, our results did not show any significant differences in the instructor's motivation when they used the blended learning method.

In the group interaction aspect, our results showed that the score of the control group was significantly higher than the intervention group. One of the learning virtualization problems is increasing student isolation and reducing the ability to use group-based learning methods. The results of our study also indicate that the ability to work in a team decreased in learning. One way to improve group interaction is to increase the number of in-person classes in the combined learning method, which was not possible in this study due to the coronavirus epidemic. In such situations, using social media platforms and virtual forums might be effective in teamwork improvement.[37]

Students' final exam score in the intervention group was significantly higher than the control group, but it should be considered that the intervention group's exam was held online due to the coronavirus pandemic. Studies indicate that cheating possibility in online exams is higher, and students' stress levels also differ for this kind of exam.[38] This difference may cause a significant error in comparing the two groups, but many studies are consistent with the above results. In a meta-analysis, Li et al.[23] indicated that using combined education improves students' level of knowledge. A systematic analysis of 49 articles concluded that using offline virtual learning compared to traditional learning will have similar and probably better results. In fact, in none of the articles reviewed in this analysis, virtual learning lagged behind in-person education.[39]

Limitations

This study used a quasi-experimental method. It's better that feature studies use randomization to reduce biases. Moreover, the type of exam in both groups should be the same, which is unavailable to us because of the lockdowns.

Conclusion

This study could create an infrastructure on the internet for teaching anatomy and use it for blended learning of GI anatomy. The level of students' satisfaction increased with this learning method. Teaching quality also improved in some aspects of breadth and learning, but we should consider that items such as age, digital literacy, and the socioeconomic status of individuals can influence the satisfaction and quality of teaching. In the group interaction subscale, the quality of teaching decreased. Using in-person classes and social media can help improve group interaction in this learning method. Students' final exam scores were also higher in the intervention group, but more studies are needed to prove this difference due to the difference between the two exams. Concerning the existence of proper infrastructure, it is suggested to use this learning method for other anatomy courses and do randomized studies with the same test between the two groups.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences [Grant Number: 397568].

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Mina Haghighat and Paria Sanei for their great help in the implementation phase of this study. The authors also wish to thank all the staff at the Virtual Education Center for their support and help during the study.

References

- 1.Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: The mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020;92:401–2. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciotti M, Ciccozzi M, Terrinoni A, Jiang W-C, Wang C-B, Bernardini S. The COVID-19 pandemic. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2020;57:365–88. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2020.1783198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323:2131–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrison DR, Kanuka H. Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. Internet Higher Educ. 2004;7:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray K, Tobin J. Introducing an online community into a clinical education setting: A pilot study of student and staff engagement and outcomes using blended learning. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:6.. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewin LO, Singh M, Bateman BL, Glover PB. Improving education in primary care: Development of an online curriculum using the blended learning model. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:33.. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Means B, Toyama Y, Murphy R, Bakia M, Jones K. Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies. Structure. 2009;115:3.. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yushau B. The effects of blended e-learning on mathematics and computer attitudes in pre-calculus algebra. Math Enthus. 2006;3:176–83. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bains M, Reynolds P, McDonald F, Sherriff M. Effectiveness and acceptability of face-to-face, blended and e-learning: A randomised trial of orthodontic undergraduates. Eur J Dent Educ. 2011;15:110–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2010.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khalil MK, Abdel Meguid EM, Elkhider IA. Teaching of anatomical sciences: A blended learning approach. Clin Anat. 2018;31:323–9. doi: 10.1002/ca.23052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh H. Building effective blended learning programs. Educ Technol. 2003;43:51–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurt E, Yurdakul SE, Ataç A. An overview of the technologies used for anatomy education in terms of medical history. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2013;103:109–15. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eagleton S. Designing blended learning interventions for the 21st century student. Adv Physiol Educ. 2017;41:203–11. doi: 10.1152/advan.00149.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khobragade S, Soe H, Khobragade Y, Abas A. Virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: What are the barriers and how to overcome them? J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10:360.. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_1422_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gharatapeh A, Rezaei M, Pasdar Y, Asadi F, Safari Y, Nazari M. Comparison of the teaching quality aspects by Student Evaluation of Education Quality (SEEQ) and students survey questionnaires health school, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. Educ Strateg Med Sci. 2015;8:247–54. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marsh HW. SEEQ: A reliable, valid, and useful instrument for collecting students'evaluations of university teaching. Br J Educ Psychol. 1982;52:77–95. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh H. Challenges and Opportunities for the Global Implementation of E-Learning Frameworks. IGI Global; 2021. Building effective blended learning programs; pp. 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris NP, Lambe J, Ciccone J, Swinnerton B. Mobile technology: Students perceived benefits of apps for learning neuroanatomy. J Comput Assist Learn. 2016;32:430–42. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung BC, Williams M, Horton C, Cosker TD. Modernising anatomy teaching: Which resources do students rely on? J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520955156.. doi: 10.1177/2382120520955156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang N, Chen J, Tai M, Zhang J. Blended learning for Chinese university EFL learners: Learning environment and learner perceptions. Comput Assist Lang Learn. 2021;34:297–323. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stefanovic S, Klochkova E. Digitalisation of teaching and learning as a tool for increasing students' satisfaction and educational efficiency: Using smart platforms in EFL. Sustainability. 2021;13:4892.. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sucaromana U. The effects of blended learning on the intrinsic motivation of Thai EFL students. Engl Lang Teach. 2013;6:141–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li C, He J, Yuan C, Chen B, Sun Z. The effects of blended learning on knowledge, skills, and satisfaction in nursing students: A meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2019;82:51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du L, Zhao L, Xu T, Wang Y, Zu W, Huang X, et al. Blended learning vs traditional teaching: The potential of a novel teaching strategy in nursing education-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022;63:103354.. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roff K. Student satisfaction and/or dissatisfaction in blended learning environments. Front Educ Technol. 2018;1:149–63. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu F-L, editor, editor. Hybrid Learning: Third International Conference, ICHL 2010, Beijing, China, August 16-18, 2010 Proceedings 3. Springer; 2010. Comparison of students' satisfaction and dissatisfaction factors in different classroom types in higher education. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venkatesh S, Rao YK, Nagaraja H, Woolley T, Alele FO, Malau-Aduli BS. Factors influencing medical students' experiences and satisfaction with blended integrated E-learning. Med Princ Pract. 2020;29:396–402. doi: 10.1159/000505210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abbasi MS, Ahmed N, Sajjad B, Alshahrani A, Saeed S, Sarfaraz S, et al. E-Learning perception and satisfaction among health sciences students amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Work. 2020;67:549–56. doi: 10.3233/WOR-203308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buckingham D. Is there a digital generation? Digital Generations: Children, Young People, and New Media. 2006:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Doherty D, Dromey M, Lougheed J, Hannigan A, Last J, McGrath D. Barriers and solutions to online learning in medical education–an integrative review. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:130.. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gould DJ, Terrell MA, Fleming J. A usability study of users' perceptions toward a multimedia computer-assisted learning tool for neuroanatomy. Anat Sci Educ. 2008;1:175–83. doi: 10.1002/ase.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mansouri M, Bigdeli S, Dehnad A, Sohrabi Z, Alizadeh S, Keshavarzi MH. Exploring the features of mobile phone application of anatomy in basic medical sciences: A qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02145-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guangul FM, Suhail AH, Khalit MI, Khidhir BA. Challenges of remote assessment in higher education in the context of COVID-19: A case study of Middle East College. Educ Assess Eval Account. 2020;32:519–35. doi: 10.1007/s11092-020-09340-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kebritchi M, Lipschuetz A, Santiague L. Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review. J Educ Technol Syst. 2017;46:4–29. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mokaripour P, Shokrpour N, Bazrafkan L. Comparison of readiness for e-learning from the perspective of students and professors of Medical Sciences. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9:111.. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_668_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alhumaid K, Ali S, Waheed A, Zahid E, Habes M. COVID-19 and Elearning: Perceptions and attitudes of teachers towards E-Learning acceptance in the developing countries. Multicult Educ. 2020;6:100–15. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Croft N, Dalton A, Grant M. Overcoming isolation in distance learning: Building a learning community through time and space. J Educ Built Environ. 2010;5:27–64. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manteghinejad A. Web-based medical examinations during the COVID-19 era: Reconsidering learning as the main goal of examination. JMIR Med Educ. 2021;7:e25355.. doi: 10.2196/25355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rasmussen K, Belisario JM, Wark PA, Molina JA, Loong SL, Cotic Z, et al. Offline eLearning for undergraduates in health professions: A systematic review of the impact on knowledge, skills, attitudes and satisfaction. J Glob Health. 2014;4:010405.. doi: 10.7189/jogh.04.010405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]