Abstract

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are a rare population of cells found in the bone marrow that play a critical role in lifelong hematopoiesis and the reconstitution of the hematopoietic system after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation remains the only curative treatment for patients with refractory hematologic disorders, and umbilical cord blood (CB) serves as an alternative stem cell source due to its several advantageous characteristics, including human leukocyte antigen flexibility and reduced donor burden. However, CB also has the disadvantage of containing a small number of cells, resulting in limited donor selection and a longer time for engraftment. Therefore, the development of techniques to expand HSCs ex vivo, particularly umbilical CB, is a goal in hematology. While various combinations of cytokines were once the mainstream approach, these protocols had limited expansion rates and did not lead to clinical application. However, in recent years, the development of a technique in which small molecules are added to cytokines has enabled the stable, long‐term ex vivo expansion of human HSCs. Clinical trials of expanded umbilical CB using these techniques have been undertaken and have confirmed their efficacy and safety. In addition, we have successfully developed a recombinant‐cytokine‐free and albumin‐free culture system for the long‐term expansion of human HSCs. This approach could offer the potential for more selective expansion of human HSCs compared to previous protocols. This review discusses ex vivo culture protocols for expanding human HSCs and presents the results of clinical trials using these techniques, along with future perspectives.

Keywords: chemical, clinical trial, ex vivo expansion, human hematopoietic stem cell, polymer

Recent advances in the ex vivo expansion methods of human hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), particularly the development of small molecule compounds, have led to significant progress in the technology for massive expansion of HSCs. In addition, we have recently successfully developed a recombinant‐cytokine‐free and albumin‐free culture system for the long‐term expansion of human HSCs. This review discusses ex vivo culture protocols for expanding human HSCs and presents the results of clinical trials using these techniques, along with future perspectives.

Abbreviations

- AhR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- CB

cord blood

- GVHD

graft‐versus‐host disease

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- HDR

homology‐directed repair

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cell

- HSCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- HSPC

hematopoietic progenitor cell

- IL‐6

interleukin‐6

- indel

insertion–deletion

- NAM

nicotinamide

- OS

overall survival

- PCL‐PVAc‐PEG

polyvinyl caprolactam‐polyvinyl acetate‐polyethylene glycol graft copolymer

- PVA

polyvinyl alcohol

- SCF

stem cell factor

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficiency

- SR‐1

StemRegenin‐1

- SRC

SCID‐repopulating cells

- TPO

thrombopoietin

1. INTRODUCTION

Hematopoietic stem cells are a rare population of cells found in the bone marrow, and are responsible for lifelong hematopoiesis and the reconstitution of the hematopoietic system after HSCT. 1 Hematopoietic stem cells are also found in CB, which is utilized for HSCT. 2 Cord blood transplantation has the advantage of a high number of acceptable human leukocyte antigen incompatibilities and no donor burden. However, it also has disadvantages, including slower engraftment, an increased risk of infection, and limitations in the number of CB units that can be transplanted, especially in adults, due to insufficient cell counts per body weight. 3 These limitations are due to the small number of HSCs present in the CB, and ex vivo expansion of human HSCs has the potential to overcome these limitations. This review article focuses on recent advances in ex vivo expansion techniques for human HSCs and clinical trials using these methods.

2. CYTOKINES

Building on the knowledge of HSC self‐renewal in vivo, researchers have developed techniques for the ex vivo expansion of HSCs. Cytokines and growth factors have played a central role in this process, and the most commonly used combinations include SCF, 4 TPO, 5 Fms‐like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand, 6 and interleukin‐6. 6 However, the long‐term stable maintenance of HSC self‐renewal could not be achieved in cytokine‐based culture systems, and the development of such systems remains insufficient for full‐scale clinical applications.

3. TRANSGENE OVEREXPRESSION

As a potential means of improving the HSC expansion, efforts have been made to introduce foreign genes into HSCs. As a result, forced expression of Hoxb4 7 and Dppa5a, 8 and activation of Notch 9 and Wnt 10 signaling, were found to be effective for enhancing HSC expansion. Another Notch ligand, Delta1, has been used in combination with cytokines for ex vivo proliferation of human umbilical CB‐derived HSPCs and has been shown to increase the number of HSPCs by more than 100‐fold and to enhance short‐term repopulating activity in low‐dose Delta1 cultures. 11 , 12 , 13

4. COCULTURED CELLS AND ECM

Cocultured cells and ECM have been examined to mimic the BM niche. Mesenchymal cells have been shown to play an important role as cocultured cells supporting HSCs ex vivo, 14 and recently, hydrogel‐based cultures of mesenchymal cells have enabled the expansion of functional HSCs. 15 It has also been reported that human HSCs can be expanded 73‐fold in 24 days by 3D culture in zwitterionic hydrogels to replicate the hydrophilic and 3D bone marrow environment. 16 The beneficial effect of these hydrogels on HSC proliferation is assumed to be due to reduced production of reactive oxygen species, thereby inhibiting differentiation.

5. SMALL MOLECULES WITH CYTOKINES

Because cytokines have shown limited success in the ex vivo expansion of human HSCs, several recent studies have examined the effectiveness of adding small molecules to cytokine cocktails, revealing that this approach indeed improved the expansion (Table 1). A pioneer in this field was SR‐1, which was identified from a screening of 100,000 compound libraries as a promoter of proliferation of umbilical CB‐derived HSPCs. SR‐1, a purine derivative that inhibits the AhR of human HSPCs, when combined with cytokines in 5‐week cultures, expanded umbilical CB‐derived HSPCs by 47‐fold and expanded SRCs, which maintain long‐term hematopoiesis in immunodeficient mice, by 17‐fold. 17 The precise molecular mechanism underlying the actions of SR‐1 remains unclear, but a study suggested that direct attenuation of the AhR pathway by overexpression of the RNA‐binding protein Musashi‐2 (MSI2) can lead to the ex vivo expansion of long‐term repopulating HSCs. 18

TABLE 1.

Small molecule‐based protocols for ex vivo expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells

| Agents | Function | Cell tested | Cytokines | Culture period | Fold expansion | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SR‐1 | AhR antagonist | CB CD34+ | SCF, TPO, FLT3‐L, IL‐6 | 21 days |

CD34+ HSPCs: 50‐fold SRCs: 17‐fold |

17 |

| Nicotinamide | Inhibition of NAD+‐dependent enzymes | CB CD34+ | SCF, TPO, FLT3‐L, IL‐6 | 21 days |

CD34+ HSPCs: 80‐fold SRCs: 9‐fold |

19 |

| UM171 | Inhibition of LSD1 and HDAC | CB CD34+ | SCF, TPO, FLT3‐L | 12 days | SRCs: 13‐fold | 20 |

| TEPA | Copper chelator | CB CD34+ | SCF, TPO, FLT3‐L, IL‐6, IL‐3 | 21 days |

CD34+CD38− HSPCs: 30.5‐fold CFUs: 172‐fold |

44 |

| NR‐101 | c‐MPL agonist | CB CD34+CD38−, CB CD34+ | SCF, FLT3‐L | 7 days |

CD34+CD38− HSPCs: 4.9‐fold SRCs: 2.9‐fold |

45 |

| Rapamycin + CHIR99021 | Inhibition of mTOR and GSK3β | CB CD34+ | None | 7 days |

TNCs: 7‐fold SRCs: 5‐fold |

46 |

| Garcinol | Inhibition of histone acetyltransferase | CB CD34+CD38−, CB CD34+ | SCF, TPO | 7 days |

CD34+CD38− HSPCs: 4.5‐fold SRCs: 2.5‐fold |

47 |

| BIO | Inhibition of GSK3β | CB CD34+ | SCF, TPO, FLT3‐L | 5 days | SRCs: 2.5‐fold | 48 |

| 5azaD + TSA | Inhibition of DNA methyltransferase/HDAC | CB CD34+, CB CD34+CD90+ | SCF, MGDF, FLT3‐L, IL‐3/SCF, MGDF, FLT3‐L | 9 days |

CD34+CD38− HSPCs: 12.5‐fold SRCs: 9.6‐fold |

49 |

| Valproic acid | Inhibition of HDAC | CB CD34+ | SCF, TPO, FLT3‐L, IL‐3 | 7 days |

CD34+ HSPCs: 213‐fold SRCs: 36‐fold |

50 |

| DEAB | Inhibition of ALDH | CB/BM CD34+CD38− | SCF, TPO, FLT3‐L | 7 days |

CD34+ HSPCs: 16.6‐fold SRCs: 3.4‐fold |

51 |

| zVADfmk | Inhibition of apoptosis | CB CD34+ | SCF, TPO, FLT3‐L, IL‐6 | 10 days | CD34+CD38− HSPCs: 3‐fold | 52 |

| UNC0638 | Inhibition of methyltransferases | PB CD34+, BM CD34+ | SCF, TPO, FLT3‐L, IL‐6, IL‐3, G‐CSF or SCF, TPO, FLT3‐L, IL‐6 | 14 days | SRCs: 2‐fold | 53 |

| dmPGE2 | PGE2 analog | CB CD34+, PB CD34+ | None | 1 h | CFUs: 1.4‐fold | 54 |

| C7 | Inhibition of p38‐MAPK | CB CD34+ | SCF, TPO, FLT3‐L | 11 days |

CD34+CD38−CD45+CD45RA− HSPCs: 1554‐fold SRCs: 2.5‐fold |

55 |

| JNK‐IN‐8 | Inhibition of JNK | CB CD34+ | SCF, TPO, FLT3‐L | 10 days |

CD34+CD38−CD45RA−CD90+ HSPCs: 8‐fold SRCs: 3.88‐fold |

56 |

| 005A | Inhibition of p18 | CB CD34+ | SCF, TPO, FLT3‐L | 7 days | CFUs: 2.72‐fold | 57 |

| CPI‐203 | Inhibition of BET | CB CD133+ | SCF, TPO, FLT3‐L | 5 days |

CD34+CD38−CD45RA−CD90+CD49f+ HSPCs: 5‐10‐fold SRCs: 1.5‐3‐fold |

58 |

Abbreviations: AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; BM, bone marrow; CB, cord blood; CFU, colony forming unit; FLT3‐L, Fms‐like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; HSPC, hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell; IL, interleukin; LSD1, lysine‐specific histone demethylase 1; HDAC, histone deacetylase; MGDF, megakaryocyte growth and development factor; PB, peripheral blood; Ref., reference; SCF, stem cell factor; SRC, SCID repopulating cell; TEPA, tetraethylenepentamine; TNC, total nucleated cells; TPO, thrombopoietin.

In 2012, NAM in combination with cytokines was found to significantly enhance the proliferation of umbilical CB‐derived HSPCs by 80‐fold within 3 weeks. 19 This led to increased SRC and enhanced CXCR4–CXCL12‐based homing in transplantation assays, resulting in higher chimerism compared to cultures with cytokines alone or uncultured CD34+ cells. These grafts were capable of hematopoietic reconstitution with cells belonging to both myeloid and lymphoid cell lineages, but CD3+ cells were not identified. Nicotinamide is a form of vitamin B3, acts as an inhibitor of NAD+‐dependent enzymes, and exerts its effect on HSC proliferation by selectively inhibiting the HDAC Sirtuin1 (SIRT1).

In 2014, a pyrimidoindole derivative, UM171, identified from a screening of 5280 compound libraries, was shown to efficiently expand human HSCs when used in combination with cytokines. UM171 enhanced the frequency of long‐term repopulating HSCs by more than 13‐fold and maintained long‐term repopulating capacity. 20 Recent studies have provided insight into the mechanism of HSC expansion by UM171. The compound activates the CULLIN3‐E3 ubiquitin ligase (CRL3) complex, which includes KBTBD4, leading to the ubiquitination of the CoREST complex. This results in the inactivation of lysine‐specific histone demethylase 1 (LSD1) and HDAC within the CoREST complex, suppressing genes involved in differentiation. 21

6. POLYMERS AND CHEMICALS

Bovine serum albumin or fetal bovine serum is commonly added to the HSC culture medium along with cytokines. Although these components are considered to play an important role as carrier proteins, it has been difficult to obtain stable results due to the large lot‐to‐lot variations caused by comingled substances. This instability and uncertainty have been major barriers to their clinical application.

In 2017, Ieyasu et al. 22 reported that synthetic albumin produced and extracted from yeast had the same functionality and stable results as albumin extracted from serum in the ex vivo expansion of mouse HSCs. However, even with this synthetic albumin, the presence of very small amounts of yeast‐derived comingled substances increased inflammatory cytokines throughout the culture, which affected the expansion of HSCs.

In 2019, Wilkinson et al. achieved a significant breakthrough by screening chemically synthesized substances that could replace the function of albumin. By adding SCF and TPO to a PVA‐based medium, they successfully expanded mouse HSCs ex vivo without albumin. 23 Polyvinyl alcohol is a water‐soluble polymer that has been used for culturing embryonic cell types. 24 Surprisingly, PVA not only was an effective substitute for the function of albumin but also showed higher expansion efficiency than albumin. Wilkinson et al. hypothesized that this is because the PVA‐based medium suppresses the production of inflammatory cytokines and the expression of genes related to cellular senescence. In addition, Sudo et al. investigated the optimal PVA for ex vivo expansion of HSCs and showed that PVA with a low hydrolysis rate expanded both mouse and human HSCs more efficiently. 25 Conversely, the molecular weight of PVA did not affect expansion. Polyvinyl alcohol can be synthesized stably and inexpensively in large quantities, providing a potential advantage over cultures using animal‐derived components or synthetic proteins, which tend to be less cost‐effective and to have lower expansion efficiency. However, the expansion efficiency of human HSCs under the same culture conditions was shown to be limited.

To investigate the differences between mouse and human HSCs, we analyzed the phosphorylation status of key signaling pathways in culture. 26 The results showed a significant decrease in PI3K/AKT signaling in human cells. To address this, we added 740Y‐P, a PI3K activator, which effectively improved the expansion rate of human HSPCs on day 7. Furthermore, we found that SCF was not required when 740Y‐P was added, and TPO was also not required when butyzamide, 27 , 28 a TPO receptor agonist, was used. Based on these findings, we successfully demonstrated that human HSPCs could be cultured in PVA plus 740Y‐P and butyzamide (2a medium) for 7 days without the use of additional cytokines. However, we also found that the cells in the 2a medium differentiated into megakaryocytes after 14 days. Therefore, we searched for compounds that prevent differentiation, and discovered that human HSPCs could be stably cultured for 30 days in 3a medium, which is produced by adding UM171 to the 2a medium. By transplanting human CB‐derived CD34+ cells cultured in 3a medium for 30 days into irradiated immunodeficient mice, we confirmed the maintenance of their ability to reconstitute hematopoiesis, and observed a significant increase in chimerism compared to that of fresh cells before the culture.

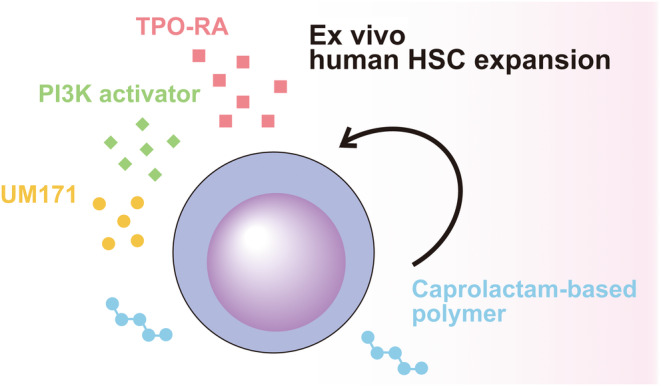

To further enhance the expansion rate, we searched for polymers that could outperform PVA. Our screening revealed that a PCL‐PVAc‐PEG 29 , 30 showed significant cell expansion potential. The PCL‐PVAc‐PEG‐based 3a medium also supported faster cell expansion over a longer term, with an approximately 75‐fold expansion of total cells and 55‐fold expansion of CD34+ cells observed after a 30 day culture. In addition, we confirmed through xenotransplantation assays that cells cultured in this medium also maintain the ability to reconstitute hematopoiesis. Next, we undertook single‐cell RNA sequencing analysis to characterize the cells cultured in the PCL‐PVAc‐PEG‐based 3a medium. We observed that a significant proportion of cells expressed HSC‐specific genes, exceeding the trend observed with the recently clinically tested UM171 and SR‐1. These results suggest that the PCL‐PVAc‐PEG‐based 3a medium selectively expands HSCs. In conclusion, we have successfully developed a recombinant cytokine‐free and albumin‐free culture system for the long‐term expansion of human HSCs (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Scheme of chemically defined cytokine‐free ex vivo expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells (HSC). TPO‐RA, thrombopoietin receptor agonist.

7. CLINICAL TRIALS

Several clinical trials have already been carried out and promising results have been reported for the ex vivo expansion of human HSCs, mainly using small molecule‐based culture systems (Table 2). The most pioneering approach is the use of NAM. The double CB transplantation of NAM‐expanded CB and unmanipulated CB in phase I 31 and the single transplantation of NAM‐expanded CB in phase I/II 32 demonstrated its safety. Subsequently, a phase III randomized controlled trial was also conducted. 33 A total of 125 patients were assigned to either the omidubicel (NAM‐expanded CB) group (62 patients) or the standard umbilical CB transplantation group (63 patients), with no significant differences in patient characteristics. CD34+ cells were expanded approximately 130‐fold (range, 32–233‐fold) in culture with NAM, and the numbers of transplanted CD34+ cells were 9.0 (range, 2.1–47.6) × 106 cells/kg in the omidubicel group. The median time to neutrophil engraftment was significantly shorter in the omidubicel group compared to the control group (12 days vs. 22 days), and the cumulative incidences of platelet engraftment by day 42 were also significantly higher in the omidubicel group (55% vs. 35%). In addition, the cumulative incidence of bacterial and invasive fungal infections was significantly lower in the omidubicel group (37% vs. 57%), and the number of days spent outside the hospital within the first 100 days posttransplantation was significantly longer in the omidubicel group (61 days vs. 48 days). There was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of grade III–IV acute GVHD or chronic GVHD. Despite the significantly improved engraftment and infection, there was no significant difference in disease‐free survival or OS.

TABLE 2.

Clinical trials of hematopoietic stem cells using ex vivo expanded cord blood

| Agent | Product name | Phase | Cord blood unit | Infused CD34+ cells (×106/kg, median) | Fold expansion of CD34+ cells (median) | Median time to neutrophil engraftment (days) | Median time to platelet engraftment (days) | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study group | Control group | Study group | Control group | |||||||

| Nicotinamide | Nicord | I | Double, one manipulated | 3.5 | 72 | 13.0 | 25.0 | 33.0 | 37.0 | |

| Nicotinamide | Nicord | I/II | Single | 6.3 | 33 | 11.5 | 21.0 | 34.0 | 46.0 | |

| Nicotinamide | Omidubicel | III | Single | 9.0 | 130 | 10.0 | 20.0 | 37.0 | 50.0 | |

| SR‐1 | HSC835 | I/II | Double, one manipulated | 17.5 | 330 | 15.0 | 24.0 | 49.0 | 89.0 | |

| UM171 | I/II | Double, one manipulated (4 pts) single (22 pts) | 2.87 | 28 | 18.0 | NA | 42.0 | 40.5 | ||

| TEPA | Carlecortemcel‐L | II/III | Single, split into two fractions | 0.16 | 77 | 21.0 | 28.0 | 54.0 | 105.0 | |

| Delta1 | NLA101 | I | Double, one manipulated | 6.0 (mean) | 164 | 16.0 | 26.0 | NA | NA | |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; pts, patients; Ref., reference; TEPA, tetraethylenepentamine.

Based on the results, on April 17, 2023, the US FDA approved omidubicel‐only (Omisirge; Gamida Cell, Ltd) for use in adult and pediatric patients (12 years and older) with hematologic malignancies who are scheduled to receive CB transplantation after myeloablative conditioning, to shorten neutrophil recovery time and reduce infection rates. This represents a significant milestone for ex vivo expansion techniques of human umbilical CB. Moreover, clinical trials have been carried out to expand the indication to include patients with nonmalignant hematologic disorders, such as severe aplastic anemia and sickle cell disease. 34

The results of a single‐arm phase I/II trial using SR‐1 for ex vivo expanded CB transplantation have also been reported. 35 In this clinical trial, a product called HSC835 was used, which involved culturing CD34+ cells from CB in a culture medium containing SR‐1 for 15 days and then adding cryopreserved CD34− fraction cells. In addition, a double CB transplantation was carried out by transplanting HSC835 and another unmanipulated CB unit. The culturing process resulted in approximately 330‐fold expansion of CD34+ cells, and the median time to neutrophil engraftment was significantly shorter in the HSC835 group compared to the historical control group (15 days vs. 24 days). The median time to platelet engraftment was also significantly shorter in the HSC835 group (49 days vs. 89 days). Although there were no significant differences in the incidence of acute GVHD, treatment‐related mortality, or OS, the hospitalization period was significantly shorter in the HSC835 group (30 days vs. 46 days).

In addition, a single‐arm phase I/II trial using UM171 was reported in 2020. 36 In this clinical trial, CD34+ cells from umbilical CB were cultured for 7 days in UM171‐containing medium, and then transplanted into patients with hematologic malignancies along with unmanipulated CD34− cells from the same CB unit. Initially, 4 patients received double CB transplants with one unit expanded using UM171 and the other unmanipulated, followed by 22 patients who received single CB transplants with UM171‐expanded cells only. After 7 days of expansion with UM171, the median net CD34+ cell count was 35 times higher than the preculture cell count. The median times to neutrophil and platelet recovery were 18 and 42 days, respectively. Resolution of febrile neutropenia also showed a trend toward shorter time compared to historical controls. At 1 year, the cumulative incidences of grade III–IV acute GVHD and chronic GVHD were 10% and 17%, respectively, the transplant‐related mortality rate was 5%, and the relapse rate was 21%. The OS and relapse‐free survival at 1 year were 90% and 74%, respectively. T cell reconstitution was evaluated in 20 surviving patients who underwent single umbilical CB transplantation expanded by UM171. It was estimated that approximately 50% of their T cells were lost during the procedure, but the recovery of CD4+ cells was rapid and no severe viral infections were observed, as compared to CB transplants reported in published works. The authors concluded that UM171‐expanded single umbilical CB transplantation offers clinical benefits with faster engraftment and fewer early infectious complications, and that the expansion technology allows the use of fewer cell number‐matched umbilical CB units.

Furthermore, the results revealed that the minimum number of cells required from umbilical CB to achieve early engraftment was at least 0.52 × 105 cells/kg CD34+ cells before the start of expansion. This finding led to a projected increase in the eligibility of CB units for selection from only 5% based on previous criteria for a 70 kg patient to 47% based on the criteria of this clinical trial. In addition, calculations using data from US CB banks showed that the donor availability for all patients increased from 72% to 84% with this expansion technology. It has also been suggested that this expansion technique could benefit racial and ethnic minorities who often face challenges in finding suitable donors. 37 Two phase II trials (NCT03913026 and NCT04103879) are currently underway for high‐risk acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, evaluating treatment‐related mortality and relapse‐free survival.

In addition, a clinical trial was carried out using an expanded CB unit with cytokines and the copper chelator tetraethylenepentamine (carlecortemcel‐L). 38 In this trial, a portion of selected CB units were expanded, and the remaining unmanipulated CB units were transplanted along with the expanded fraction. The primary end‐point was the 100 day survival, which was compared to a concurrent double‐unit CB transplantation group. The median time to neutrophil (21 days vs. 28 days) and platelet engraftment (54 days vs. 105 days) was significantly shorter in the carlecortemcel‐L study group compared to the control group, and the 100 day survival rate was also significantly improved compared to the control group.

Recent advances in the ex vivo expansion methods of human HSCs, particularly the development of small molecule compounds, have led to significant progress in the technology for massive expansion of HSCs. Moreover, promising results have been reported in clinical trials using these technologies. Expanded CB transplantation was shown to exhibit a time to engraftment and an incidence of infections comparable to those of these other stem cell sources. However, challenges remain with this technology. Long‐term clinical benefits, such as OS, have not been fully evaluated. In addition, in a phase III trial using omidubicel, the manufacturing period was 21 days and the manufacturing failure rate was 10%, resulting in 14% of patients not receiving treatment. To make this therapy available to more patients, improvements such as shortening the incubation period or frozen off‐the‐shelf expanded products need to be considered. 39

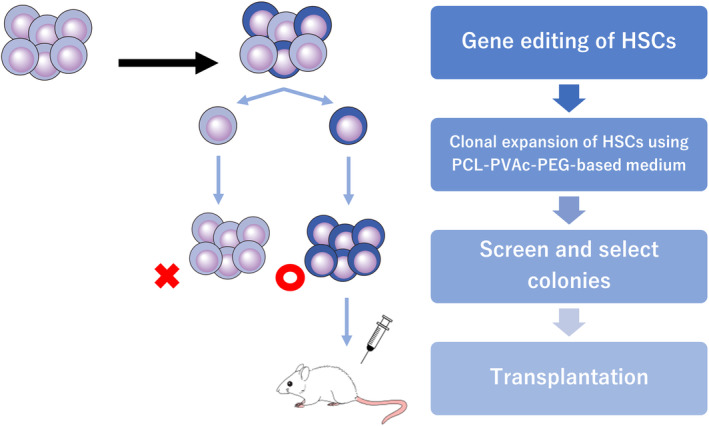

Hematopoietic stem cell expansion techniques are not only being explored for transplantation but also for other applications, with particular interest in gene therapy applications. Recently, CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing has opened the possibility of efficiently correcting disease‐causing genetic mutations in patient‐derived cells, and is also being extensively investigated in human HSPCs. 40 However, in conventional HSC gene editing followed by bulk expansion, the majority of cells carry alleles with unintended edits, such as small indels, caused by nonhomologous end joining, as well as large deletions. 41 These mutations represent unpredictable risks and can undermine the efficacy and safety of gene therapeutic applications. 42

Most recently, Becker et al. 43 achieved expansion and direct selection of HDR‐corrected murine HSC clones using a single‐cell expansion protocol including PCL‐PVAc‐PEG‐based medium (Figure 2). In a murine SCID model, HDR‐mediated correction of the causative point mutation was only achieved in approximately 20% of alleles, with indels and large deletions representing the majority of editing outcomes. To address this, the authors first undertook genome editing on SCID mouse HSCs, followed by 4 days of bulk culture. Subsequently, cells were cloned from the primitive CD201+CD150+CD48−KSL population, and single‐cell expansion was performed for 2 weeks in PCL‐PVAc‐PEG‐based medium. Of the HSC colonies that emerged after the single‐cell expansion period, genotype screening revealed that 50% of clones had at least one HDR‐corrected allele. These corrected HSC clones were combined and transplanted into conditioned SCID mice. As a result, all cells in the transplanted graft were phenotypically corrected, and over 70% of the alleles in the graft were HDR‐edited. This represents a significant improvement over conventional bulk expansion methods, where most cells remain uncorrected and contain either unmodified or indel alleles. Single‐cell expansion is a significant departure from conventional bulk expansion methods and allows direct control of genetic heterogeneity in the transplant graft. Genome editing technology is rapidly evolving and is expected to be widely adopted in gene therapy for various hematological disorders. For translational application of the single‐cell expansion approach to edited human HSCs, there is a need for improved culture systems that support extensive expansion of single human HSC clones as well as more reliable markers to identify and purify human Long‐term HSCs.

FIGURE 2.

Scheme for controlling the genetic heterogeneity in gene‐edited murine hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) by single‐cell culture. PCL‐PVAc‐PEG, polyvinyl caprolactam‐acetate polyethylene glycol.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Masatoshi Sakurai: Conceptualization; writing – original draft. Kantaro Ishitsuka: Conceptualization; writing – original draft. Hans Jiro Becker: Conceptualization; writing – original draft. Satoshi Yamazaki: Conceptualization; supervision.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

M.S. and S.Y. are cofounders and shareholders in Celaid Therapeutics. S.Y. has received research funding from BASF. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENTS

Approval of the research protocol by an institutional review board: N/A.

Informed consent: N/A.

Registry and the registration no. of the study/trial: N/A.

Animal studies: N/A.

Sakurai M, Ishitsuka K, Becker HJ, Yamazaki S. Ex vivo expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells and clinical applications. Cancer Sci. 2024;115:698‐705. doi: 10.1111/cas.16066

REFERENCES

- 1. Wilkinson AC, Igarashi KJ, Nakauchi H. Haematopoietic stem cell self‐renewal in vivo and ex vivo. Nat Rev Genet. 2020;21:541‐554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gluckman E, Broxmeyer HE, Auerbach AD, et al. Hematopoietic reconstitution in a patient with Fanconi's anemia by means of umbilical‐cord blood from an HLA‐identical sibling. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1174‐1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ballen KK, Gluckman E, Broxmeyer HE. Umbilical cord blood transplantation: the first 25 years and beyond. Blood. 2013;122:491‐498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Williams DE, Eisenman J, Baird A, et al. Identification of a ligand for the c‐kit proto‐oncogene. Cell. 1990;63:167‐174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yamazaki S, Iwama A, Takayanagi SI, et al. Cytokine signals modulated via lipid rafts mimic niche signals and induce hibernation in hematopoietic stem cells. EMBO J. 2006;25:3515‐3523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Walasek MA, van Os R, de Haan G. Hematopoietic stem cell expansion: challenges and opportunities. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1266:138‐150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Antonchuk J, Sauvageau G, Humphries RK. HOXB4‐induced expansion of adult hematopoietic stem cells ex vivo. Cell. 2002;109:39‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miharada K, Sigurdsson V, Karlsson S. Dppa5 improves hematopoietic stem cell activity by reducing endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1381‐1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Varnum‐Finney B, Xu L, Brashem‐Stein C, et al. Pluripotent, cytokine‐dependent, hematopoietic stem cells are immortalized by constitutive Notch1 signaling. Nat Med. 2000;6:1278‐1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reya T, Duncan AW, Ailles L, et al. A role for Wnt signalling in self‐renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:409‐414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ohishi K, Varnum‐Finney B, Bernstein ID. Delta‐1 enhances marrow and thymus repopulating ability of human CD34(+)CD38(−) cord blood cells. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1165‐1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Delaney C, Heimfeld S, Brashem‐Stein C, Voorhies H, Manger RL, Bernstein ID. Notch‐mediated expansion of human cord blood progenitor cells capable of rapid myeloid reconstitution. Nat Med. 2010;16:232‐236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Delaney C, Varnum‐Finney B, Aoyama K, Brashem‐Stein C, Bernstein ID. Dose‐dependent effects of the notch ligand Delta1 on ex vivo differentiation and in vivo marrow repopulating ability of cord blood cells. Blood. 2005;106:2693‐2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jing D, Fonseca AV, Alakel N, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells in co‐culture with mesenchymal stromal cells – modeling the niche compartments in vitro. Haematologica. 2010;95:542‐550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sharma MB, Limaye LS, Kale VP. Mimicking the functional hematopoietic stem cell niche in vitro: recapitulation of marrow physiology by hydrogel‐based three‐dimensional cultures of mesenchymal stromal cells. Haematologica. 2012;97:651‐660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bai T, Li J, Sinclair A, et al. Expansion of primitive human hematopoietic stem cells by culture in a zwitterionic hydrogel. Nat Med. 2019;25:1566‐1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boitano AE, Wang J, Romeo R, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor antagonists promote the expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2010;329:1345‐1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rentas S, Holzapfel NT, Belew MS, et al. Musashi‐2 attenuates AHR signalling to expand human haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2016;532:508‐511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peled T, Shoham H, Aschengrau D, et al. Nicotinamide, a SIRT1 inhibitor, inhibits differentiation and facilitates expansion of hematopoietic progenitor cells with enhanced bone marrow homing and engraftment. Exp Hematol. 2012;40:342‐355.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fares I, Chagraoui J, Gareau Y, et al. Cord blood expansion. Pyrimidoindole derivatives are agonists of human hematopoietic stem cell self‐renewal. Science. 2014;345:1509‐1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chagraoui J, Girard S, Spinella JF, et al. UM171 preserves epigenetic marks that are reduced in ex vivo culture of human HSCs via potentiation of the CLR3‐KBTBD4 complex. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28:48‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ieyasu A, Ishida R, Kimura T, et al. An all‐recombinant protein‐based culture system specifically identifies hematopoietic stem cell maintenance factors. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;8:500‐508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wilkinson AC, Ishida R, Kikuchi M, et al. Long‐term ex vivo haematopoietic‐stem‐cell expansion allows nonconditioned transplantation. Nature. 2019;571:117‐121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wiles MV, Johansson BM. Embryonic stem cell development in a chemically defined medium. Exp Cell Res. 1999;247:241‐248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sudo K, Yamazaki S, Wilkinson AC, Nakauchi H, Nakamura Y. Polyvinyl alcohol hydrolysis rate and molecular weight influence human and murine HSC activity ex vivo. Stem Cell Res. 2021;56:102531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sakurai M, Ishitsuka K, Ito R, et al. Chemically defined cytokine‐free expansion of human haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2023;615:127‐133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nogami W, Yoshida H, Koizumi K, et al. The effect of a novel, small non‐peptidyl molecule butyzamide on human thrombopoietin receptor and megakaryopoiesis. Haematologica. 2008;93:1495‐1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sakurai M, Takemoto H, Mori T, Okamoto S, Yamazaki S. In vivo expansion of functional human hematopoietic stem progenitor cells by butyzamide. Int J Hematol. 2020;111:739‐741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jin X, Zhou B, Xue L, San W. Soluplus® micelles as a potential drug delivery system for reversal of resistant tumor. Biomed Pharmacother. 2015;69:388‐395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Linn M, Collnot EM, Djuric D, et al. Soluplus® as an effective absorption enhancer of poorly soluble drugs in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2012;45:336‐343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Horwitz ME, Chao NJ, Rizzieri DA, et al. Umbilical cord blood expansion with nicotinamide provides long‐term multilineage engraftment. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3121‐3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Horwitz ME, Wease S, Blackwell B, et al. Phase I/II study of stem‐cell transplantation using a single cord blood unit expanded ex vivo with nicotinamide. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:367‐374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Horwitz ME, Stiff PJ, Cutler C, et al. Omidubicel vs standard myeloablative umbilical cord blood transplantation: results of a phase 3 randomized study. Blood. 2021;138:1429‐1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Parikh S, Brochstein JA, Galamidi E, Schwarzbach A, Kurtzberg J. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation with omidubicel in sickle cell disease. Blood Adv. 2021;5:843‐852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wagner JE, Brunstein CG, Boitano AE, et al. Phase I/II trial of StemRegenin‐1 expanded umbilical cord blood hematopoietic stem cells supports testing as a stand‐alone graft. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:144‐155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cohen S, Roy J, Lachance S, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation using single UM171‐expanded cord blood: a single‐arm, phase 1‐2 safety and feasibility study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e134‐e145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dumont‐Lagacé M, Feghaly A, Meunier MC, et al. UM171 expansion of cord blood improves donor availability and HLA matching for all patients, including minorities. Transplant Cell Ther. 2022;28:410.e1‐410.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stiff PJ, Montesinos P, Peled T, et al. Cohort‐controlled comparison of umbilical cord blood transplantation using carlecortemcel‐L, a single progenitor‐enriched cord blood, to double cord blood unit transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24:1463‐1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shpall EJ, Rezvani K. Cord blood expansion has arrived. Blood. 2021;138:1381‐1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dever DP, Bak RO, Reinisch A, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 β‐globin gene targeting in human haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2016;539:384‐389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mohrin M, Bourke E, Alexander D, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence promotes error‐prone DNA repair and mutagenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:174‐185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tsai SQ, Joung JK. Defining and improving the genome‐wide specificities of CRISPR‐Cas9 nucleases. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:300‐312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Becker HJ, Ishida R, Wilkinson AC, et al. Controlling genetic heterogeneity in gene‐edited hematopoietic stem cells by single‐cell expansion. Cell Stem Cell. 2023;30:987‐1000.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Peled T, Mandel J, Goudsmid RN, et al. Pre‐clinical development of cord blood‐derived progenitor cell graft expanded ex vivo with cytokines and the polyamine copper chelator tetraethylenepentamine. Cytotherapy. 2004;6:344‐355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nishino T, Miyaji K, Ishiwata N, et al. Ex vivo expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells by a small‐molecule agonist of c‐MPL. Exp Hematol. 2009;37:1364‐1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Huang J, Nguyen‐McCarty M, Hexner EO, Danet‐Desnoyers G, Klein PS. Maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells through regulation of Wnt and mTOR pathways. Nat Med. 2012;18:1778‐1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nishino T, Wang C, Mochizuki‐Kashio M, Osawa M, Nakauchi H, Iwama A. Ex vivo expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells by garcinol, a potent inhibitor of histone acetyltransferase. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ko KH, Holmes T, Palladinetti P, et al. GSK‐3β inhibition promotes engraftment of ex vivo‐expanded hematopoietic stem cells and modulates gene expression. Stem Cells. 2011;29:108‐118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Araki H, Mahmud N, Milhem M, et al. Expansion of human umbilical cord blood SCID‐repopulating cells using chromatin‐modifying agents. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:140‐149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chaurasia P, Gajzer DC, Schaniel C, D'Souza S, Hoffman R. Epigenetic reprogramming induces the expansion of cord blood stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2378‐2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chute JP, Muramoto GG, Whitesides J, et al. Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase and retinoid signaling induces the expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11707‐11712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sangeetha VM, Kale VP, Limaye LS. Expansion of cord blood CD34 cells in presence of zVADfmk and zLLYfmk improved their in vitro functionality and in vivo engraftment in NOD/SCID mouse. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen X, Skutt‐Kakaria K, Davison J, et al. G9a/GLP‐dependent histone H3K9me2 patterning during human hematopoietic stem cell lineage commitment. Genes Dev. 2012;26:2499‐2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Goessling W, Allen RS, Guan X, et al. Prostaglandin E2 enhances human cord blood stem cell xenotransplants and shows long‐term safety in preclinical nonhuman primate transplant models. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:445‐458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bari S, Zhong Q, Fan X, et al. Ex vivo expansion of CD34+ CD90+ CD49f+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells from non‐enriched umbilical cord blood with azole compounds. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2018;7:376‐393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Xiao X, Lai W, Xie H, et al. Targeting JNK pathway promotes human hematopoietic stem cell expansion. Cell Discov. 2019;5:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Li Y, Zhang W, Zhang Y, et al. Enhanced self‐renewal of human long‐term hematopoietic stem cells by a sulfamoyl benzoate derivative targeting p18INK4C. Blood Adv. 2021;5:3362‐3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hua P, Hester J, Adigbli G, et al. The BET inhibitor CPI203 promotes ex vivo expansion of cord blood long‐term repopulating HSCs and megakaryocytes. Blood. 2020;136:2410‐2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]