Summary

Anopheles gambiae uses its sense of smell to hunt humans. We report a two-step method yielding cell-type-specific driver lines for enhanced neuroanatomical and functional studies of its olfactory system. We first integrated a driver-responder-marker (DRM) system cassette consisting of a linked T2A-QF2 driver, QUAS-GFP responder, and a gut-specific transgenesis marker into four chemoreceptor genes (Ir25a, Ir76b, Gr22, and orco) using CRISPR-Cas9-mediated homology-directed repair. The DRM system facilitated rapid selection of in-frame integrations via screening for GFP+ olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) in G1 larval progeny, even at genomic loci such as orco where we found the transgenesis marker was not visible. Next, we converted these DRM integrations into T2A-QF2 driver-marker lines by Cre-loxP excision of the GFP responder, making them suitable for binary use in transcuticular calcium imaging. These cell-type-specific driver lines tiling key OSN subsets will support systematic efforts to decode olfaction in this prolific malaria vector.

Keywords: mosquito, malaria, Anopheles gambiae, olfaction, olfactory sensory neuron, CRISPR-Cas9

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Two-step method for engineering Anopheles gambiae cell-type-specific driver lines

-

•

Expanded neurogenetic toolkit to study the Anopheles gambiae olfactory system

-

•

Functional validation of the toolkit to decode mosquito responses to human odorants

Motivation

The African malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae uses olfaction to track humans and orchestrate other behaviors such as oviposition site search that are critical for its survival. The mosquito neural circuitry and odorants driving such olfactory behaviors remain largely unknown. To yield an expanded collection of transgenic resources to advance studies of olfactory coding in this major malaria vector, we developed a two-step method to rapidly visualize target chemoreceptor gene expression patterns and to derive cell-type-specific driver lines for binary expression of reporter transgenes in the An. gambiae olfactory system.

Giraldo et al. report a two-step method facilitating genetic access to specific olfactory sensory neuron populations in the African malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. They generate cell-type-specific driver lines for a suite of chemoreceptor genes and validate their utility to decode the odor tuning dynamics of the Anopheles gambiae olfactory system.

Introduction

Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto (Diptera: Culicidae) is a devastating vector of human malaria throughout sub-Saharan Africa. This highly anthropophilic mosquito species blood feeds preferentially and frequently on humans,1,2,3,4,5,6 posing a major threat to public health in this region. To navigate toward a host from a range of distances, An. gambiae females use their sense of smell to detect various chemical cues that signal human presence.7,8,9,10,11 Olfaction also plays a crucial role in other important An. gambiae behaviors such as nectar seeking,12,13,14 detection of oviposition sites,15,16 and swarm formation for mating.17

The main olfactory appendages of female An. gambiae are the antennae, maxillary palps, and the labella of the proboscis. These organs house olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) expressing chemosensory receptors such as odorant receptors (ORs), ionotropic receptors (IRs), and gustatory receptors (GRs) that bind volatile organic compounds encountered by An. gambiae in its sensory environment. Comparative genomics suggests that the An. gambiae genome putatively encodes 76 ORs, 110 IRs, and 93 GRs18—an unknown proportion of which are likely to function in olfaction.

Studies of a subset of these ORs in An. gambiae and its closely related sibling species An. coluzzii have implicated this chemoreceptor gene family in detection of multiple classes of odorants such as aldehydes, ketones, esters, alcohols, and aromatic compounds19,20,21 that are present in volatile emissions from hosts and nectar, among other sources. Single ORs complex with the odorant receptor co-receptor (Orco) to form ligand-gated cation channels tuned to these ligands. In contrast, IRs in these two malaria vectors likely mediate sensation of amines and acids22,23 found predominantly in human scent, with each IR acting in conjunction with one or more IR co-receptors (IR8a, IR76b, and IR25a) to detect odorants. A subset of GRs expressed in the An. gambiae and An. coluzzii maxillary palps (GR22, GR23, and GR24) have been found to form a CO2 receptor complex sensitive to this gaseous ligand,24,25,26 which can also be activated by a range of other volatile organic compounds.27

Analyses in Drosophila melanogaster, An. coluzzii, and Aedes aegypti have shown that while some OSNs only express one class of receptor, there are subsets of OSNs that express multiple, broadening their tuning properties.23,28,29 This includes OSNs in these species that putatively co-express unique combinatorial repertoires of co-receptors such as Orco, IR76b, IR8a, and IR25a alongside their associated ligand-tuning receptors. Recent advances in mosquito neurogenetics have been crucial to gain genetic access to subpopulations of these OSNs using binary expression systems (e.g., QF2-QUAS system). This has facilitated neuroanatomical studies of the expression patterns of chemosensory receptors as well as their tuning properties.23,28,30,31,32,33

Efforts to apply neurogenetic tools in An. coluzzii initially applied a promoter-fusion-based strategy to characterize the expression pattern of the orco gene in the antennae, maxillary palps, and labella and to map the projections of orco+ OSNs into the antennal lobe.34 More recently in An. coluzzii, T2A-QF2 in-frame fusions have been applied to map the expression patterns of the IR co-receptor gene Ir76b in the antennae and labella,33 the tuning receptor gene Ir41c in multiple segments of the antenna,23 and the active zone protein gene bruchpilot throughout the nervous system.35 Implementation of binary expression systems in this species has also enabled cell-type-specific expression of genetically encoded calcium indicators (e.g., GCaMP6f) to study the tuning of Orco- and IR41c-expressing OSNs23,30 by transcuticular calcium imaging. This approach enables rapid recording of odor-evoked responses from multiple individual OSNs at once in a non-invasive fashion, which makes it an ideal tool to screen for compounds that activate certain OSN classes in mosquitoes and to study their ligand tuning dynamics.

Here, we engineer an expanded neurogenetic toolkit to study the An. gambiae olfactory system. We report application of a two-step method to develop cell-type-specific T2A-QF2 driver lines for target An. gambiae chemoreceptors. Specifically, we demonstrate the utility of integrating a single multiplexed “driver-responder-marker” (DRM) cassette consisting of a T2A-QF2 driver directly coupled with a floxed QUAS-mCD8::GFP responder and an Actin5C (Act5C) fluorescent transgenesis marker to rapidly label OSNs expressing the olfactory chemoreceptor genes Ir25a, Ir76b, Gr22, and orco. We highlight several factors for consideration when using such configurations to generate cell-type-specific neurogenetic tools in An. gambiae including the potential for positional effects to modulate the expression of both responder and marker transgenes at these olfactory loci. We also demonstrate application of Cre-loxP excision to generate conventional driver-marker (DM) T2A-QF2 drivers for each target gene that are suitable for binary use and map expression patterns across olfactory appendages using an An. gambiae responder line expressing the genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP6f.36 Finally, we apply transcuticular calcium imaging to record neurophysiological responses to select human-related odorants for each OSN class. These cell-type-specific drivers tiling subsets of OSNs thus have applied utility for neuroanatomical and functional mapping of the An. gambiae olfactory system and expand the neurogenetic toolkit available for molecular and cellular studies of olfaction in this primary vector of human malaria as well as its closely related sibling species An. coluzzii by transgene introgression.

Results

A driver-responder-marker system for rapid reporting of chemoreceptor gene expression patterns in the Anopheles gambiae olfactory system

T2A in-frame fusion technology has recently been deployed in both An. gambiae and An. coluzzii to map the expression patterns of a select handful of hygrosensors and thermoreceptors,37 chemoreceptors,23,33 and pan-neuronal gene targets.35 To date, all of these cell-type-specific drivers have been developed by integrating a T2A-QF2 transgene alongside an associated 3xP3 fluorescent transgenesis marker into the target locus via CRISPR-Cas9-mediated homology-directed repair (HDR). Given the need to select transformants and then typically outcross and amplify the driver line before crossing an established responder line such as QUAS-mCD8::GFP from An. coluzzii,34 this process can typically take 3–4 generations before defining the neuroanatomical expression pattern of the target gene.

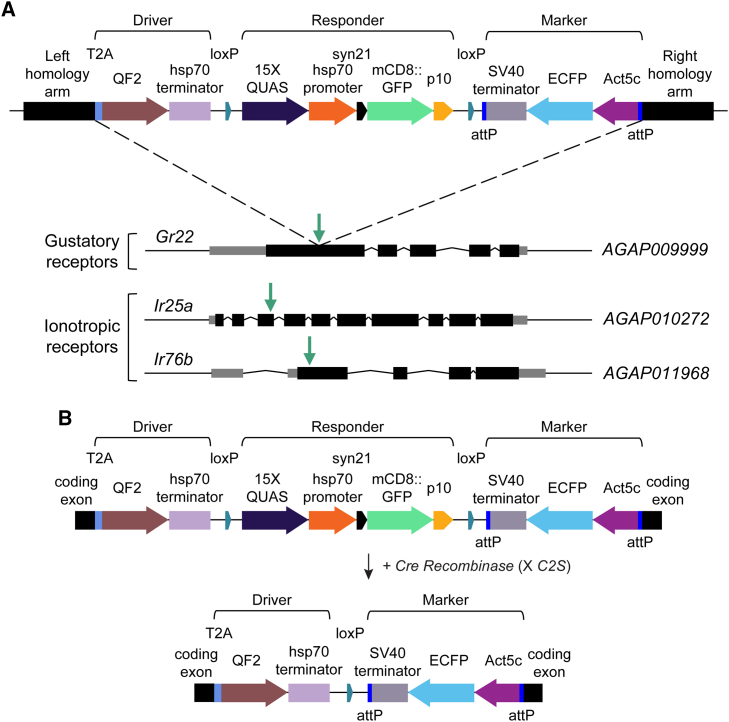

In this study, to rapidly report whether T2A in-frame fusions successfully gained genetic access to and labeled target subsets of OSNs in the An. gambiae olfactory system, we initially applied CRISPR-Cas9-mediated HDR to integrate a multiplexed transgenic cassette containing components of the QF2/QUAS binary expression system in-frame into coding exons of three olfactory co-receptor genes. These loci included Ir76b previously targeted to generate a complementary T2A-QF2 driver in An. coluzzii,33 as well as Ir25a and the CO2 receptor complex gene Gr22, which have not previously been targeted to generate such reagents. In an attempt to develop lines that neuroanatomically report gene expression in a single transgenesis step visible in G1 transformants, we designed the integration cassette to consist of three parts: (1) a T2A-QF2 driver component, (2) a fluorescent QUAS-mCD8::GFP responder component that was floxed (flanked by loxP sites), and (3) an Act5C-based transgenesis marker component, forming a DRM system configuration (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the DRM system for rapid reporting of gene expression patterns and development of binary T2A-QF2 drivers for the Anopheles gambiae chemoreceptor genes Gr22, Ir25a, and Ir76b

(A) Schematic of the DRM cassette integrated by CRISPR-Cas9-mediated HDR. The cassette contains three components: (1) a T2A-QF2 driver, (2) a QUAS-mCD8::GFP responder, and (3) an Act5C-ECFP transgenesis marker. These components are flanked by homology arms to catalyze in-frame insertion of this DRM cassette into coding exons of Gr22, Ir25a, and Ir76b resulting in the lines Gr22DRM, Ir76bDRM, and Ir25aDRM.

(B) After DRM line establishment, the QUAS-mCD8::GFP responder component, which is flanked by loxP sites, can be removed via Cre-loxP-mediated excision to generate conventional T2A-QF2 driver lines for binary use resulting in the lines Gr22QF2, Ir25aQF2, and Ir76bQF2. See also Figure S1.

Specifically, the “driver” consisted of a T2A-QF2 transgene followed by a Drosophila hsp70 terminator to drive the expression of the transcription factor QF2 under the control of the endogenous regulatory elements of each chemoreceptor gene when integrated in-frame into a target coding exon. The “responder” consisted of a 15XQUAS-hsp70P-Syn21-mCD8::GFP-p10 transgene with a Drosophila hsp70 core promoter (hsp70P) to drive the expression of mCD8::GFP in cell types where QF2 is expressed. We flanked this fluorescent reporter with both a Syn21 sequence and p10 3′ UTR shown to act as translational enhancers in Drosophila38 to promote robust labeling of neuronal membranes and processes. We also strategically included loxP sites surrounding this transgene to facilitate its prospective removal using Cre-loxP excision, which is highly efficient in An. gambiae39,40 (Figure 1B). Finally, the “marker” consisted of an Act5C-ECFP-SV40 transgene consisting of the Drosophila Actin5C (Act5C) promoter41 driving expression of enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP) with an SV40 terminator in the An. gambiae midgut to serve as a marker of successful transformation and to substitute for commonly used 3xP3 fluorescent markers, which are also expressed in the nervous system.23,25,33,34,37 The Act5C-ECFP marker was also surrounded by two φC31 attP sites to facilitate prospective exchange of this marker in lines post establishment as desired using recombination-mediated cassette exchange.42,43,44

For each target gene, we next designed a dual gRNA/Cas9 vector expressing a gRNA targeting a coding exon (Table S1), as well as an HDR donor plasmid containing the DRM cassette (Table S2) and microinjected these reagents into pre-blastoderm stage An. gambiae (G3 strain) embryos. Using this strategy, we successfully isolated G1 transformants for all three of these initial target genes by screening for visible expression of ECFP in the midgut of 1st instar larvae. Subsequently, we outcrossed these lines to the wild-type G3 strain to generate the following DRM lines: Gr22DRM, Ir25aDRM, and Ir76bDRM.

After line establishment, we then performed confocal analyses on the antennae, maxillary palps, and labella (Figure 2A) of DRM females to determine the expression pattern of Gr22, Ir76b, and Ir25a. Strikingly, we observed expression of mCD8::GFP in all three appendages in these DRM lines (Figure S1). The expression was broad in Ir25aDRM with numerous cells strongly labeled with fluorescence in all three tissues (Figure S1A). Ir76bDRM also had broad expression in the labella and antennae, but only few fluorescent cells were found in the maxillary palps (Figure S1B). The Gr22DRM line showed expression in multiple cells of the maxillary palps but only 1–2 cells in the antenna and labella (Figure S1C).

Figure 2.

T2A-QF2 in-frame fusions for binary use report expression patterns of the chemoreceptor genes Gr22, Ir76b, and Ir25a in Anopheles gambiae olfactory appendages

(A) Image of the head of an An. gambiae female with the main olfactory appendages (antennae, maxillary palps, and labella of the proboscis) labeled. The right panel summarizes the observed pattern of Gr22QF2, Ir76bQF2, and Ir25aQF2-transactivated QUAS-GCaMP6f expression in these appendages.

(B) Gr22+ OSNs were found in the maxillary palps (genotype: Gr22QF2, Act5C-ECFP>15XQUAS-GCaMP6f, 3xP3-ECFP).

(C) Ir76b+ OSNs were restricted to the antennae and labella of the proboscis (genotype: Ir76bQF2, Act5C-ECFP>15XQUAS-GCaMP6f, 3xP3-ECFP).

(D) Ir25a+ OSNs were more broadly expressed in the maxillary palps, antennae, and labella (genotype: Ir25aQF2, Act5C-ECFP>15XQUAS-GCaMP6f, 3xP3-ECFP). (B–D) Scale bar represents 30 μm. See also Figures S1, S2, and S3.

Transcriptomic analyses have revealed that Gr22 is expressed by CO2-sensitive OSNs (cpA) found in the maxillary palps26 but not in the antenna,15 which made expression of this gene in cells outside of the maxillary palps surprising. Ir76b transcripts have previously been detected in An. coluzzii maxillary palp tissue.45,46 However, a previous T2A-QF2 in-frame insertion in Ir76b in An. coluzzii reported expression of this gene in the antennae and labella but not the maxillary palps.33

To evaluate the potential for responder leakiness alone to generate such sparse labeling patterns in olfactory tissues, we next generated an independent An. gambiae QUAS-mCD8::GFP responder line using piggyBac-mediated transposition (Figure S1D). This line included an Act5C-DsRed marker and gypsy insulators flanking the QUAS-mCD8::GFP cassette in an attempt to buffer any local cis-regulatory elements at the integration site and enhancer elements associated with the Act5C promoter from influencing the expression of this responder transgene. Confocal analyses of olfactory appendages in a single isolated line carrying this responder transgene surprisingly revealed leaky mCD8::GFP expression in cells across the antennae, labella, and maxillary palps (Figure S1D) in the absence of QF2-based transactivation. This result suggests that some of the expression observed in these DRM lines may not be driven by the target genes—indicative of locus-dependent leaky expression (Figures S1B–S1D).

We conclude that the DRM system has the potential to rapidly report chemoreceptor gene expression patterns in the An. gambiae olfactory system. However, the potential for positional effects influencing the expression of responder transgenes within the context of the DRM system, as well as the potential for leaky expression in responder transgenes integrated elsewhere in the An. gambiae genome may confound interpretation of expression patterns in the absence of neurophysiological, transcriptomic, or RNA in situ hybridization data for cross-validation.

Cre-loxP excision of responder cassettes from Anopheles gambiae DRM lines generates conventional T2A-QF2 drivers suitable for binary use in cell-type-specific labeling

The DRM cassette we designed included a floxed QUAS-mCD8::GFP responder transgene (Figure 1A). To remove this fluorescent reporter, we employed Cre-loxP cassette excision. To do this, we crossed each DRM line with the C2S line (Figure 1B) that expresses Cre recombinase in the An. gambiae germline.39,40 We then selected individual progeny that did not have visible GFP labeling in adult olfactory tissue but retained the Act5C-ECFP marker in the midgut, indicative of successful excision of the QUAS-mCD8::GFP responder. Confocal analyses of the antennae, labella, and maxillary palps from these responder excised lines showed no expression of mCD8::GFP in any cells across olfactory appendages (Figures S2A–S2C). We subsequently validated that these resulting lines only carried T2A-QF2 driver and Act5C-ECFP marker transgenes with a single intervening loxP site using PCR (see STAR Methods). We have denoted these conventional T2A-QF2 driver lines as Gr22QF2, Ir76bQF2, and Ir25aQF2.

To determine the expression pattern of these target chemoreceptors in peripheral chemosensory appendages in the head of female An. gambiae, we crossed Gr22QF2, Ir76bQF2, and Ir25aQF2 lines with an An. gambiae QUAS-GCaMP6f strain that we generated with piggyBac-mediated transposition using a construct previously validated in An. coluzzii.30 For these neuroanatomical studies, we used the fluorescent calcium indicator GCaMP6f36 to label cells instead of our QUAS-mCD8::GFP line since we determined that the An. gambiae QUAS-GCaMP6f line that we generated lacked detectable leaky expression (Figures S1D and S3). Confocal analyses revealed expression of GCaMP6f in maxillary palp OSNs of the Gr22QF2>QUAS-GCaMP6f females (Figure 2B), as well as labeling of OSNs in the maxillary palps and labella of Ir76bQF2>QUAS-GCaMP6f females (Figure 2C). We also found strong labeling in OSNs of the maxillary palps, antennae, and labella of Ir25aQF2>QUAS-GCaMP6f females (Figure 2D). For each of these genotypes, we did not observe any fluorescence across any of the tissues sparsely labeled in the parental DRM integrations or those carrying the QF2 driver cassettes only (Figure S3). The loss of sparse labeling patterns in these binary T2A-QF2 lines may thus result from excision of the QUAS-mCD8::GFP reporter or alternatively the lower basal green fluorescence of GCaMP6f relative to mCD8::GFP making these rare cell types not visible.

A DRM integration into the Anopheles gambiae orco gene illuminates positional effects influencing expression of both responder and marker transgenes

We hypothesized that the Drosophila hsp70 core promoter used in both our initial DRM and independent QUAS-mCD8::GFP responder integrations may have been a potential source of reporter leakiness. To investigate alternative core promoters for use in the DRM system, we next replaced the hsp70 core promoter associated with the QUAS elements of the DRM cassette (Figure 1A) with a piggyBac core promoter (Figure 3A) that has successfully been used for enhancer trapping in An. stephensi47 to generate a 15XQUAS-pBacP-Syn21-mCD8::GFP-p10 transgene. To pilot whether this transgene could label An. gambiae OSNs, we integrated this updated DRM system configuration in-frame into exon 2 of the odorant receptor co-receptor orco, which is broadly expressed throughout the An. gambiae and An. coluzzii olfactory system34,45 using CRISPR-Cas9-mediated HDR.

Figure 3.

A DRM integration into the Anopheles gambiae orco gene reveals positional effects modulating responder and marker transgene expression

(A) Schematic of the DRM cassette for integration into the An. gambiae orco gene using CRISPR-Cas9-mediated HDR to generate orcoDRM and subsequent Cre-loxP excision of the responder transgene to generate orcoQF2 for binary use.

(B) orco+ OSNs were found in the maxillary palp, antennae, and labella of the proboscis.

(C) Locus-dependent heterogeneity in Act5C-ECFP marker expression across An. gambiae T2A-QF2 in-frame fusion lines. Act5C-ECFP expression (white arrows) in larval midgut mark T2A-QF2 driver integration is shown. 3xP3-ECFP expression (green arrows) in ventral nerve cord and optic lobe mark QUAS-GCaMP6f responder integration is shown. No visible expression of Act5C-ECFP was observed in the orcoQF2 integration, despite evidence of GFP labeling in OSNs in the larval antennae of both this cross and parental orcoDRM line. See also Figures S4 and S5.

Notably, in G1 transformants, we clearly observed mCD8::GFP expression in antennae of L1- to L4-stage larvae (Figure S4A) indicating functionality of the piggyBac core promoter in this revised QUAS-mCD8::GFP responder transgene, facilitating the isolation of an orcoDRM line. However, we did not observe any larvae expressing ECFP in the midgut, despite evidence of a fully intact Act5C-ECFP transgenesis marker being integrated in this line as revealed through Sanger sequencing (see STAR Methods). Likewise, we did not observe any mCD8::GFP expression in adult chemosensory appendages suggesting the piggyBac core promoter may be active only in larval stages when integrated at this locus. To validate the integration of T2A-QF2 into this location in orco was indeed capable of capturing endogenous regulatory elements suitable for reporting expression of this target gene across larval and adult stages of An. gambiae, we next excised this responder construct from the orcoDRM by Cre-loxP excision as described above to generate a conventional orcoQF2 line (Figure 3A) for binary expression. We then crossed orcoQF2 with our QUAS-GCaMP6f line and in the resulting progeny found GCaMP6f expression in the larval antenna (Figure S4B) as well as strong labeling in OSNs in the antennae, labella, and maxillary palps of adult females (Figure 3B).

These results indicate that the piggyBac core promoter is functional at An. gambiae larval stages for use in association with QUAS responder transgenes. However, we determined that this core promoter drives stage-specific responder transgene expression when integrated at the orco locus suggesting locus-dependent effects. Likewise, Act5C-ECFP when integrated in the orco locus also appears highly susceptible to positional effects as indicated by no visible expression of this marker in this genomic context. Nevertheless, larval-specific mCD8::GFP expression within the context of a DRM configuration ensured successful isolation of initial transformants in the absence of a detectable Act5C-driven fluorescent transgenesis marker, facilitating the downstream establishment of a functional orcoQF2 line.

Positional effects at Anopheles gambiae Ir25a, Ir76b, and Gr22 genomic loci influence the expression patterns of Act5C transgenesis markers

Consistent with positional effects influencing the expression pattern of the Act5C-ECFP marker when integrated into the orco gene, we noticed that the expression pattern of this fluorescent marker also varied across each of the other chemoreceptor genes that we targeted. For instance, in integrations generated at Gr22 and Ir25a, the Act5C-ECFP marker is expressed broadly throughout the midgut, whereas at Ir76b, this marker is expressed in the posterior midgut (Figure 3C). Since Act5C is a commonly used promoter for An. gambiae and An. coluzzii transgenesis and considered a candidate substitute promoter to mark neurogenetic tools given its non-neuronal expression pattern, these positional effects influencing the activity of the Act5C promoter should be taken into consideration during construct design and screening to recover transformants for studies of Anopheles neurobiology.

T2A-QF2 in-frame fusions facilitate transcuticular calcium imaging of OSN activity in Anopheles gambiae in response to stimulation with human-related odorants

Transcuticular calcium imaging has previously been applied to understand the ligand tuning dynamics of subsets of An. coluzzii OSNs expressing orco and Ir41c23,30 and An. gambiae hygrosensitive neurons expressing Ir93a.37 To validate the utility of the T2A-QF2 lines developed here for this purpose, we next performed functional imaging with each of the QF2 lines crossed to the An. gambiae QUAS-GCaMP6f line that we generated.

GR22 is a CO2 receptor complex subunit that is expressed in cpA neurons on the maxillary palps,26 and this chemoreceptor is required for modulating sensitivity of this OSN class to CO2 and other odorants in An. coluzzii.25 We first tested whether Gr22+ OSNs found on the maxillary palp of An. gambiae females responded to CO2 by crossing our Gr22QF2 driver with our QUAS-GCaMP6f responder and imaging odor-evoked activity in maxillary palps of progeny carrying both of these transgenes (retaining one wild-type Gr22 allele). We stimulated mosquitoes with a 1-s pulse of 1% CO2 and observed an increase in odor-evoked fluorescence in Gr22+ cells (Figure 4A). Over a series of three CO2 concentrations (0.1%, 0.5%, and 1% CO2), we observed that odor-evoked responses increased with increasing CO2 concentration (Figures 4B and 4C). CO2-evoked responses observed in response to stimulation with 1% CO2 were significantly greater than those observed at 0.1% or 0.5%, respectively (Figure 4C). These results confirm that Gr22+ OSNs are indeed responsive to CO2.

Figure 4.

Gr22+ OSNs on the Anopheles gambiae maxillary palps respond to CO2

(A) GCaMP6f fluorescence in Gr22 + OSNs before (left) and during (right) 1% CO2 stimulation (genotype: Gr22QF2, Act5C-ECFP>15XQUAS-GCaMP6f, 3xP3-ECFP).

(B) GCaMP6f traces of Gr22+ OSNs after 1-s pulses (black bar) of increasing CO2 concentrations. Mean ± SEM is plotted (n = 10).

(C) Maximum change in fluorescence above baseline to increasing concentrations of 1-s CO2 pulses. Mean ± SEM is plotted (n = 10). Two-sided Wilcoxon signed rank test: 0%–1% ∗∗p = 0.002; 0.5%–1% ∗∗p = 0.0039.

To further validate transcuticular GCaMP imaging with Ir76bQF2, Ir25aQF2, and orcoQF2>QUAS-GCaMP6f females, we next stimulated antennal OSNs from each of these genotypes with ligands previously shown to activate these classes of chemoreceptors in Drosophila and An. coluzzii,48,49 which are also found in human odor.50,51,52 We found that Ir76b+ OSNs in the 8th antennal segment showed a significant response to a 0.28% trimethylamine stimulus relative to a water control (Wilcoxon signed rank test p = 0.0039, Figure 5A). Additionally, Ir25a+ OSNs in the 12th antennal segment responded significantly more strongly to 1% pyridine relative to a water control (Wilcoxon signed rank test p = 0.002, Figure 5B), and orco+ cells in the same segment responded significantly more strongly to 1% sulcatone relative to a paraffin oil control (Wilcoxon signed rank test p = 0.002, Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Odor-evoked activity of Ir76b+, Ir25a+ and orco+ OSNs in the Anopheles gambiae antennae to select human-related odorants

(A) GCaMP6f traces in Ir76b+ OSNs in the 8th antennal segment in response to a 1-s pulse of 0.28% trimethylamine or a water control (left) and quantification of the maximum ΔF/F values obtained from the traces (n = 9) for each stimulus (right). Genotype: Ir76bQF2, Act5C-ECFP>15XQUAS-GCaMP6f, 3xP3-ECFP.

(B) GCaMP6f traces in Ir25a+ OSNs in the 12th antennal segment in response to a 1-s pulse of 1% pyridine or a water control (left) and quantification of the maximum ΔF/F values (n = 10) (right). Genotype: Ir25aQF2, Act5C-ECFP>15XQUAS-GCaMP6f, 3xP3-ECFP.

(C) GCaMP6f traces of orco+ OSNs in the 12th antennal segment in response to a 3-s pulse of 1% sulcatone or a paraffin oil control (left) and quantification of the maximum ΔF/F values (n = 10) (right). Genotype: orcoQF2, Act5C-ECFP>15XQUAS-GCaMP6f, 3xP3-ECFP. (A–C) Orange and black bars indicate stimulus onset and duration. Mean ± SEM is plotted in all panels. ∗∗p < 0.01, two-sided Wilcoxon signed rank test.

We conclude that these T2A-QF2 lines validated here with transcuticular calcium imaging expand the repertoire of available tools in An. gambiae to study olfactory coding in OSN subsets expressing the chemoreceptor genes Gr22, Ir76b, Ir25a, and orco.

Discussion

Advances in our understanding of olfaction in malaria vectors have been spurred by integrative studies of their electrophysiological and behavioral responses to odorants,24,26,27,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60 genomics and transcriptomics,15,22,45,49,61 heterologous expression systems,19,20,22,24 and genome editing.21,25 Most recently, application of binary expression systems has provided insights into the neuroanatomy and function of OSNs and chemoreceptors as well as other aspects of sensory biology of An. gambiae and An. coluzzii. These have included use of the QF2/QUAS system for cell-type-specific labeling and calcium imaging using promoter fusion34 and T2A in-frame fusion23,33,35,37-based QF2 drivers. In this study, we sought to expand the repertoire of cell-type-specific drivers for studies of olfactory coding in An. gambiae given its status as a major primary vector of human malaria in sub-Saharan Africa.

Our approach to generate QF2/QUAS reagents in An. gambiae revealed several important considerations for engineering functional genetic tools in this non-model insect and related species. We initially developed a DRM system to rapidly obtain transgenic lines that report the expression pattern of chemoreceptor genes in the peripheral nervous system of An. gambiae, orthologous to recent designs in Ae. aegypti used to express genetically encoded calcium indicators pan-neuronally32 and in orco+ OSNs.31 This system allowed us to, in a single step, insert a cassette that has a T2A-QF2 driver, a floxed QUAS-mCD8::GFP responder, and an Act5C fluorescent transgenesis marker using CRISPR-Cas9-mediated homologous recombination into target chemosensory genes. We initially piloted this approach using the co-receptor genes: Gr22, Ir76b, and Ir25a. We confirmed the DRM system provided a rapid method to label cells expressing these genes across olfactory appendages. These analyses revealed the Ir25aDRM lines broadly labeled cells in the antennae, maxillary palps, and labella, Gr22DRM predominantly labeled cells in the maxillary palps, and Ir76bDRM mostly labeled numerous cells in the antennae and labella, which is consistent with transcriptomic data indicating the expression of each of these genes in these olfactory tissues.15,26

For the Gr22DRM line, we also detected sparse cell labeling patterns in the antennae and labella that were discordant with current transcriptomic data indicating Gr22 expression is restricted to the maxillary palps.15,26 For the Ir76bDRM line, we conversely detected sparse labeling of cells in the maxillary palps, which is supported by transcriptomic studies in An. coluzzii indicating the presence of Ir76b transcripts in this tissue.45,46 However, Ir76b+ cells on the maxillary palps were not observed in a separate study using a complementary Ir76b T2A-QF2 An. coluzzii line and GFP labeling.33 Likewise, these sparse labeling patterns were not observed in the Gr22QF2>QUAS-GCaMP6f and Ir76bQF2>QUAS-GCaMP6f individuals we engineered and analyzed here. Whether such sparse labeling patterns found in our Gr22DRM and Ir76bDRM lines reflect leakiness of the hsp70 core promoter associated with the QUAS-mCD8::GFP transgene in the DRM system configuration that we integrated into each of these loci or whether these cells are labeled variably using these transgenic tools or not always captured at the resolution of current transcriptomic analyses performed in these tissues awaits further characterization.

We also observed leaky reporter expression in numerous cells on the antenna, palp, and labella in the complete absence of QF2-based transactivation in an independent An. gambiae QUAS-mCD8::GFP responder line that we generated. We hypothesize that this undesirable labeling pattern may be observed in this line due to local cis-regulatory elements acting on the QUAS-associated hsp70 core promoter at the site of transgene integration yielding leaky reporter expression. We suggest such leaky reporter expression may also have been accentuated in this instance by the addition of gypsy insulators surrounding the responder cassette. Such an effect has been previously reported in Drosophila where insulator elements seem to have enhancer activity in certain tissues that lead to an increase in leaky expression of reporter genes under the control of UAS in a position-dependent manner.62 In an orthologous fashion, leakiness of reporter transgene expression in nervous tissues of a separate QUAS-mCD8::GFP responder line with a hsp70 core promoter in An. coluzzii has been previously reported.34

While the DRM system is susceptible to positional effects, in the instance of the orcoDRM integration, it also proved to be an invaluable backup marker system where the Act5-ECFP marker used to report transgenesis was not active. The DRM approach is therefore highly useful when integrating cargo into genomic loci where the suitability of a chosen transgenesis marker for expression at that location is unknown and the expression pattern of the target gene is predictable. For instance, in this study, we tested the utility of the Act5C promoter to drive ECFP expression, which is canonically expressed in the An. gambiae midgut,39 to confirm DRM integrations into target chemoreceptor genes. This was done in an attempt to investigate alternative promoters to replace the commonly used promoter 3xP3,63 which can drive fluorescent marker expression variably throughout the nervous system.64 In the instance of the orco locus, we would have never recovered transformants without this DRM QUAS-mCD8:GFP responder transgene visibly labeling larval OSNs, due to the inactivity of the Act5C promoter at this genomic site.

To make DRM lines suitable for use in a binary fashion, we demonstrated that Cre-loxP excision39 can successfully convert these integrations into conventional T2A-QF2 DM lines, which have the potential to be crossed to any QUAS responder transgene of interest. Using these reagents, when crossed with an An. gambiae QUAS-GCaMP6f line that we generated, we illuminated expression patterns and functional responses for each of our four target chemoreceptor genes. These results revealed that Gr22QF2 drives GCaMP6f expression exclusively in OSNs of the maxillary palps where they respond to CO2. This was consistent with the known expression of Gr22 in CO2 receptor complex neurons alongside Gr23 and Gr24 in An. coluzzii and An. gambiae maxillary palps.24,25 The Ir76bQF2>QUAS-GCaMP6f expression pattern we observed in the antennae and labella matched the transgenic labeling pattern previously reported for this gene in a T2A-QF2 knockin in An. coluzzii.33 In this line, we found OSNs in the antenna that responded to trimethylamine, which is a ligand of OSNs expressing this co-receptor in flies65 and a known component of human odor.52

In contrast, Ir25aQF2>QUAS-GCaMP6f mosquitoes exhibited a broader expression pattern across all olfactory appendages. Broad expression of Ir25a was also observed in Ae. aegypti, where it was found to be co-expressed with other receptor genes including orco and Ir76b.28 The broad expression pattern we observe for this receptor suggests that such co-expression in An. gambiae is highly likely. We specifically identified a subset of Ir25a+ antennal OSNs that responded to the aromatic compound pyridine found in human skin emanations,66 which also is sensed by OSNs expressing this co-receptor in Drosophila.48 Finally, orcoQF2>QUAS-GCaMP6f mosquitoes also revealed broad expression of this gene in all olfactory appendages, which is consistent with the expression pattern previously described using an orco promoter fusion QF2 line of An. coluzzii34. We identified orco+ OSNs on the antenna that responded to sulcatone, which is an abundant ketone present in human scent.50

These lines for transcuticular imaging therefore provide a rapid means to image odor-evoked activity in An. gambiae. These neurogenetic tools complement existing neurophysiological methods such as single sensillum recordings (SSRs)24,26,27,54,55,67 and electroantennogram (EAG)/electropalpogram (EPG) recordings53,56,57,58,59 to enhance studies of olfactory coding in this species. Future studies may therefore apply these reagents to comprehensively profile the ligand tuning dynamics of each of these OSN subtypes to additional components of human scent and other chemosensory stimuli. Furthermore, this neurogenetic toolkit may also be used to gain insights into how changes in internal physiological state such as mating, immune challenge, starvation, and Plasmodium falciparum infection affect An. gambiae olfactory neurophysiology and behavior.

In summary, we have successfully generated T2A-QF2 in-frame fusions in the chemoreceptor genes Gr22, Ir25a, Ir76b, and orco, to provide genetic access to large subsets of OSNs collectively tiling the An. gambiae olfactory system. This work highlights several key considerations for engineering functional genetics tools in An. gambiae and related disease vectors, as well as non-model organisms. These validated reagents for neuroanatomy and functional imaging in An. gambiae expand the repertoire of neurogenetic tools available to study olfaction in this important malaria vector.

Limitations of the study

The goal of this study was to develop an expanded collection of cell-type-specific driver lines to support neuroanatomical and functional studies in the An. gambiae olfactory system. To achieve this, we employed the modular DRM system to rapidly select for functional T2A-QF2 in-frame fusions in the G1 generation by screening for GFP+ OSNs in the larval antennae. This facilitated recovery of transformants even in genomic contexts where the Act5C-ECFP transgenesis marker was not visible such as the orco locus. While not currently common practice, an equivalent result could be obtained via crossing G0 animals to a homozygous QUAS-mCD8::GFP strain. We demonstrated that DRM lines can be converted to conventional T2A-QF2 DM lines by crossing with a germline Cre recombinase strain, providing flexibility to users with regard to how they generate driver lines. Likewise, in this study, we performed transgenesis and downstream functional imaging assays in the An. gambiae G3 strain. However, the QF2 and QUAS integrations reported here can also be flexibly introgressed into other An. gambiae and An. coluzzii strains for experimental characterization in different genetic backgrounds.

We determined using the DRM-based T2A in-frame fusion strategy in the An. gambiae orco gene that positional effects have the potential to influence the expression of both responder and marker transgenes. Specifically, we noted that a piggyBac core promoter we used in association with QUAS elements in the mCD8::GFP responder component of this line exhibited an unexpected larval-specific labeling of OSNs that was absent in adults. We also found a complete absence of a visible Act5C-ECFP transgenesis marker in this line. The piggyBac core promoter has been previously used in Gal4-based enhancer trapping in adult Anopheles stephensi,47 and therefore, we anticipated it would be also active across life cycle stages in An. gambiae. Likewise, we predicted the Act5C-ECFP marker would also be visible when integrated at this locus. Strikingly, this was not the case in either instance, and future studies should therefore seek to identify basal core promoters that are not susceptible to such effects to ensure expression across life cycle stages and to abrogate leakiness, as well as screen promoters for transgenesis markers that are best suited for each target locus.

For instance, alternative synthetic core promoters such as the Drosophila synthetic core promoter have been used to replace the hsp70 core promoter for binary expression systems in Drosophila,20,38 and endogenous core promoters have been employed with the GAL4/UAS system in Tribolium castaneum.68 Likewise, systematic surveys in other Drosophila species have been used to identify new transgenesis markers suitable for use across different genomic loci.64 The positional effects we observed in this study finally highlight the need to identify landing sites in the An. gambiae genome for site-specific integration of responder constructs for controlled neurogenetic studies, where leakiness from QUAS or UAS responder transgenes is reduced or absent as has been surveyed in Drosophila.62,69

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| PBS | Quality Biological | 119-069-131 |

| Trimethylamine | TCI | T0464 |

| Pyridine | Sigma-Aldrich | 270407 |

| 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one (Sulcatone) | Sigma-Aldrich | M48805 |

| Paraffin oil | Supelco | PX0047-1 |

| Slow-Fade Gold Antifade Mountant | Invitrogen | S36936 |

| Synthetic clean air | Airgas | UZ300 |

| 5% CO2 | Airgas | X02AI95C2000117 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Anopheles gambiae: Wild type G3 strain | Laboratory of Andrea Crisanti Hammond et al.42 |

N/A |

| Anopheles gambiae: C2S strain | Laboratory of Andrea Crisanti Volohonsky et al.39 |

N/A |

| Anopheles gambiae: Ir25aDRM strain | This paper | N/A |

| Anopheles gambiae: IR76bDRM strain | This paper | N/A |

| Anopheles gambiae: Gr22DRM strain | This paper | N/A |

| Anopheles gambiae: orcoDRM strain | This paper | N/A |

| Anopheles gambiae: Ir25aQF2 strain | This paper | N/A |

| Anopheles gambiae: IR76bQF2 strain | This paper | N/A |

| Anopheles gambiae: Gr22QF2 strain | This paper | N/A |

| Anopheles gambiae: orcoQF2 strain | This paper | N/A |

| Anopheles gambiae: QUAS-GCaMP6f strain | This paper | N/A |

| Anopheles gambiae: QUAS-mCD8::GFP strain | This paper | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| gRNA target site sequences, see Table S1 | This paper | N/A |

| Primers for constructing donor plasmids, see Table S2 | This paper | N/A |

| Primers for plasmid p371 construction, see Table S3 | This paper | N/A |

| Primers for verifying HDR integration, see Table S4 | This paper | N/A |

| Primers for sequence verification of Act5C-ECFP marker cassette in orcoQF2 strain, see METHOD DETAILS | This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| p174: base gRNA/Cas9 expression plasmid | Kyrou et al.70 | N/A |

| p17424: Ir25a gRNA/Cas9 expression plasmid | This paper | N/A |

| p17422: Ir76b gRNA/Cas9 expression plasmid | This paper | N/A |

| p17425: Gr22 gRNA/Cas9 expression plasmid | This paper | N/A |

| p17421: orco gRNA/Cas9 expression plasmid | This paper | N/A |

| p313: base DRM donor plasmid | This paper | N/A |

| p31304: Ir25a DRM donor plasmid | This paper | N/A |

| p31302: Ir76b DRM donor plasmid | This paper | N/A |

| p31305: Gr22 DRM donor plasmid | This paper | N/A |

| p327: modified base DRM donor plasmid | This paper | N/A |

| p32701: orco DRM donor plasmid | This paper | N/A |

| p371: QUAS-mCD8::GFP plasmid | This paper | N/A |

| p361: QUAS responder plasmid for exchange of reporters | This paper | N/A |

| pXL-BACII-ECFP-15xQUAS-TATA-Gcamp6f-SV40 | Gift of Chris Potter Afify et al.30 |

N/A |

| pENTR R4-vas2-Transposase-R3 | Gift of Eric Marois Volohonsky et al.39 |

N/A |

| pBB | Shankar et al.71 | N/A |

| pMosECFP-15XQUAS-mCD8:GFP | Shankar et al.71 | N/A |

| pK104c | Gift of Kyros Kyrou Quinn et al.72 |

N/A |

| pSL1180-QUAS-pBacP-mCD8GFP | Gift of Diego Giraldo | N/A |

| pSL∗UAS-LUCg | Gift of Gareth Lycett Lynd et al.73 |

N/A |

| pPBRED | Gift of Tony Nolan Nolan et al.74 |

N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Fiji | Schindelin et al.75 | https://imagej.net/software/fiji |

| MATLAB R2018b | The MathWorks Inc. | https://www.mathworks.com/products/matlab.html |

| Micro-Manager | Edelstein et al.76 | https://micro-manager.org |

| Arduino IDE | Arduino | https://www.arduino.cc |

| Zeiss Zen Microscopy | Zeiss | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/en/products/software/zeiss-zen.html |

| Other | ||

| Gibson Assembly kit | NEB | E5510S |

| In-Fusion HD Cloning kit | Takara Bio | 639650 |

| CloneAmp HiFi PCR Premix | Takara Bio | 639298 |

| NucleoSpin Tissue kit | Macherey-Nagel Inc | 740952.50 |

| Mass flow controller | Alicat Scientific | MC-series 100 |

| Mass flow controller | Alicat Scientific | MC-series 500 |

| Solenoid valve driver | Automate Scientific | ValveLink 8.2 |

| 3-way solenoid valve | Clippard | ETO-2-12 |

| 3-way solenoid valve | The Lee Company | LHDA1223411H |

| Solenoid valve 8 port manifold | The Lee Company | LFMX0510528B |

| 1/4″ vinyl tubing | Cole-Parmer | 06405–02 |

| Arduino UNO | Arduino | A000066 |

| Epifluorescence microscope | Olympus | BX51W1 |

| LED light source | Sutter Instrument | Lambda HPX-L5 |

| Confocal microscope | Zeiss | LSM 880 |

| CMOS camera | Hamamatsu Photonics K. K. | Orca-Fusion C14440 |

| Quartz capillary glass tube | Sutter Instrument | QF100-70-10 |

| Fly vials | Flystuff | 32–110 |

| Double-sided tape | Scotch | 137DM-2 |

| Filter papers, 6 mm diameter, | Cytiva Whatman | 2017006 |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Conor McMeniman (cmcmeni1@jhu.edu).

Materials availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact without restriction.

Data and code availability

-

•

All raw data supporting these analyses have been deposited publicly in the Johns Hopkins Research Data Repository at: https://doi.org/10.7281/T1/NTWJAR.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and study participant details

Mosquito strains and maintenance

The Anopheles gambiae G3, C2S39 and transgenic strains engineered in this study were maintained with a 14 h light: 10 h dark photoperiod at 27°C and 80% relative humidity using a standardized rearing protocol.77 Adults were provided with a 10% sucrose solution for colony maintenance.

Anopheles gambiae G3 (Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center MR4, Atlanta, USA; stock number MRA-112) is a wild type strain collected in 1975 from MacCarthy Island, The Gambia.78 The colony used in this study (gift of A. Crisanti, Imperial College London) has been molecularly characterized by both SNP genotyping79 and whole genome resequencing80 as being an An. gambiae s.s./An. coluzzii hybrid stock, that is primarily Savannah type, with An. gambiae species-specific markers on the X chromosome.

Method details

gRNA/Cas9 expression constructs

The CRISPR vector p174,70 expressing Cas9 under the An. gambiae promoter zero population growth and a gRNA under the U6 promoter, was secondarily modified by Golden Gate Cloning, as previously described70 to contain gRNA spacers specific to targeting each of the olfactory target genes (Table S1). This yielded gRNA/Cas9 expression plasmids for Ir25a (p17424), Ir76b (p17422), Gr22 (p17425) and orco (p17421).

Generation of T2A-QF2 DRM constructs

A base HDR vector (p313) for integration of the driver-responder-marker (DRM) system into target An. gambiae chemoreceptor genes, was cloned using Gibson Assembly (New England Biolabs). Briefly, fragments containing a T2A-QF2 driver (from pBB71), a Syn21-15XQUAS-hsp70P-mCD8::GFP-p10 responder (from pMosECFP-15XQUAS-mCD8GFP71) flanked by two loxP sites, and an Act5C-ECFP marker flanked by two φC31 attP sites (from pK104c, gift of K. Kyrou72) were assembled in the p174 vector70 digested with AgeI and MluI. To target Ir25a, Ir76b and Gr22, p313 was secondarily modified to contain homology arms of approximately 1.5kb in length that were PCR amplified from An. gambiae G3 strain genomic DNA, extending outwards from each gRNA cleavage site (Table S2). The p313 base vector can be easily modified to contain any pair of homology arms in a single cloning step by digesting this vector with MluI and PmeI, co-purifying the two fragments in a single column cleanup step, and using Gibson Assembly to combine the two plasmid fragments with that of the homology arms at equimolar ratio. This assembly strategy yielded HDR vectors for Ir25a (p31304), Ir76b (p31302) and Gr22 (p31305).

To target the orco gene, a modified DRM base plasmid (p327) was generated by substituting the hsp70 core promoter in the responder component, with a piggyBac core promoter (pBacP)47 to generate a 15XQUAS-pBacP-Syn21-mCD8::GFP-p10 responder. Briefly, the fragment comprising T2A-QF2-hsp70t-LoxP, 15XQUAS-hsp70P was excised from p313 by digestion with PmeI and XhoI. Gibson assembly of this digested p313 backbone, T2A-QF2-hsp70t-LoxP amplified from p313, and QUAS-pBacP sequence amplified from pSL1180-QUAS-pBacP-mCD8GFP (gift of D. Giraldo) was then performed. Homology arms for the orco target site were then amplified (Table S2) and inserted into p327 by digesting this base vector with MluI and PmeI and using Gibson assembly as described above for the other chemoreceptor genes, yielding the HDR vector for orco (p32701).

Generation of independent responder constructs for insertion into the An. gambiae genome using piggyBac-mediated transposition.

In Fusion cloning (Takara Bio) was used to assemble the responder vector (p371) for generation of an An. gambiae QUAS-mCD8::GFP line using piggyBac mediated transposition. To generate p371, fragments comprising gypsy insulators from Drosophila melanogaster, QUAS-hsp70P-syn21, HindIII-mCD8::GFP-p10, and LoxP-Act5C-DsRed were PCR amplified (Table S3) and cloned into an empty p313 vector backbone, digested with PvuI and AscI. A derivative vector (p361) facilitates exchange of mCD8::GFP for alternative reporters by restriction digestion of this plasmid using HindIII and PmeI.

The plasmid pXL-BACII-ECFP-15xQUAS-TATA-Gcamp6f-SV4030 was used to generate an An. gambiae QUAS-GCaMP6f line in the G3 strain genetic background using piggyBac-mediated transposition.

Microinjection

Pre-blastoderm stage embryos from the An. gambiae G3 strain were microinjected in the posterior pole as previously described,81 using injection solutions comprising 300ng of each target-specific vector (i.e., HDR donor detailed in Table S1) and the corresponding Cas9/gRNA vector detailed in in 1x microinjection buffer.81 Responder strains were created using injection solutions comprising 300 ng/μL each of the responder (i.e., p371 or pXL-BACII-ECFP-15xQUAS-TATA-Gcamp6f-SV40) and vasa transposase (pENTR R4-vas2-Transposase-R3)39 vectors. Briefly, freshly laid embryos were aligned against nitrocellulose paper and injected using a quartz capillary needle, three-axis micromanipulator (Narishige, MMO-4) and microinjector (Eppendorf FemtoJet 4X). 300–500 embryos were injected to obtain each transgenic line.

Identification and verification of DRM integrations

An. gambiae G0 larvae with transient expression of fluorescent markers resulting from microinjection were isolated as virgin adults and outcrossed to the wild type G3 strain. Transgenic G1 progeny with visible Act5C-ECFP expression in the larval midgut (Ir25aDRM, Ir76bDRM and Gr22DRM), or visible GFP expression in the larval antennae (orcoDRM) were maintained as heterozygous lines by outcrossing as virgins to the G3 strain each generation. HDR cassette integration into each target gene was confirmed using PCR with a forward primer anchored outside of each left HDR arm and a reverse primer anchored in the QF2 coding sequence (Table S4).

Cre-loxP excision of responder transgenes to yield T2A-QF2 in-frame fusions for binary use

To excise responder transgenes from each of the DRM strains, a minimum of 20 virgin females of the C2S line expressing Cre recombinase in the An. gambiae germline39,40 were mated to a minimum of 20 virgin males for each DRM line (i.e., Ir25aDRM, IR76bDRM, Gr22DRM and orcoDRM). Progeny carrying both the Act5C-ECFP marker linked to the driver cassette, and 3xP3-DsRed marker linked to the C2S line, were outcrossed to wild type in reciprocal male and female crosses. Driver strains suitable for binary use (i.e., Ir25aQF2, IR76bQF2, Gr22QF2 and orcoQF2) were isolated by selecting progeny carrying the Act5C-ECFP marker linked to the driver cassette that also had no visible mCD8::GFP expression in larval OSNs (i.e., indicating successful excision of the floxed QUAS-mCD8::GFP responder); and which also lacked the 3xP3-DsRed marker linked to vas2-Cre recombinase from the C2S line.

Sequence verification of the Act5C-ECFP marker cassette in orcoQF2

orcoQF2 driver mosquitoes were crossed with the QUAS-GCaMP6f responder line and adult G1 female progeny were screened for GCaMP6f fluorescence in the antenna and a 3xP3-ECFP marker to identify individuals carrying both of these transgenes (i.e., those with visible GFP labeling the larval antennae marking the presence of the orcoQF2 driver transgene and 3xP3-ECFP expression in larval optic nerves and ventral nerve cord marking the presence of the QUAS-GCaMP6f responder transgene). To confirm that the Act5C-ECFP marker associated with the orcoQF2 driver transgene that was not visible was fully intact, genomic DNA was extracted from a single mosquito using the NucleoSpin Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel Inc., 740952.50). A diagnostic PCR was then performed to fully amplify the Act5C-ECFP marker using the primer: 5′-TATCGATACCGTCGACTAAAGCC-3′ and 5′-CCAATTTGAAGTGCAGATAGCAGT-3′, and its sequence was verified using Sanger sequencing.

Imaging of peripheral olfactory appendages

Live antennal, palp and labella tissues were dissected in 0.1M PBS (119-069-131, Quality Biological) and immediately mounted in Slow-Fade Gold Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen, S36936) on glass slides. Images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 880 Airyscan Fast confocal microscope within 2 h of dissection. The 488 nm laser line was used to excite the green GCaMP6f signal. An additional DIC channel was used to visualize bright field morphology of the peripheral tissue. Images of the antennae, palps, and labella were acquired with a 40X oil immersion objective. Images were processed using Fiji.75 A maximum intensity projection was acquired for all z-slices of the GCaMP6f images.

Mosquito preparation for peripheral calcium imaging

3-6 day old female mosquitoes were transferred to Drosophila vials (28.5 mm diameter, 95 mm long, 320110, Flystuff) containing a cotton ball soaked with dH2O for 1 h before calcium imaging. Mosquitoes were cold anesthetized on ice for 3 min, and the wings and legs were gently removed. They were then placed sideways on double-sided tape (Scotch, 137DM-2) to affix the thorax and abdomen in position. The proboscis, antennae, and maxillary palps were placed on a coverslip to allow air to flow over them. These organs were pinned down with a quartz capillary (QF100-70-10, Sutter Instrument) to reduce movement of the preparation.

CO2 delivery for calcium imaging

5% CO2 (X02AI95C2000117, Airgas) was mixed with clean air (UZ300, Airgas) using mass flow controllers (MC-series 100, MC-series 500, Alicat Scientific) to obtain the desired CO2 concentration at a flowrate of 2 mL/s. The stimulus was pulsed by a solenoid valve (ETO-3-12, Clippard) controlled by an Arduino (Arduino UNO, Arduino) and a valve driver (ValveLink 8.2, Automate Scientific). These brought the CO2 stimulus into a carrier flow of humidified air (6 mL/s) for a total flow of 8 mL/s. A compensatory clean air flow (2 mL/s) was on whenever the CO2 stimulus was off to ensure a constant flow of 8 mL/s.

Odorant delivery for calcium imaging

Trimethylamine (T0464, TCI) and pyridine (270407, Sigma-Aldrich) were diluted in molecular-grade dH2O to obtain a concentration of 0.28% and 1% respectively. Sulcatone (M48805, Sigma-Aldrich) was diluted in paraffin oil (PX0047-1, Supelco) to obtain a concentration of 1%. 100% dH2O or 100% paraffin oil were used as control stimuli. To prepare odor cartridges for stimulation, 40μL of solution were pipetted onto two round filter papers (Cytiva Whatman 2017006, 6 mm diameter, 20μL per paper) and the papers were inserted into 3cm segments of 1/4″ vinyl tubing (06405-02, Cole-Parmer). The cartridge was capped on both ends with parafilm until ready to use. Odors were delivered using a custom made olfactometer consisting of two manifold arrays (LFMX0510528B, The Lee Company) each containing 8 solenoid valves (LHDA1223411H, The Lee Company). Clean air (UZ300, Airgas) that was humidified was brought into a first manifold array at a flowrate of 2 mL/s set with a mass flow controller (MC-series 100, Alicat Scientific). The odor cartridge was then connected to the output of one of the eight valves of the array on one end, and to the input of a solenoid valve in the second manifold array on the other end. The valves on each end of the odor cartridge were opened and closed simultaneously using an Arduino (Arduino UNO, Arduino) and a valve driver (ValveLink 8.2, Automate Scientific) to allow airflow over the headspace of the filter papers for odor stimulation. This system facilitates having up to 7 odor cartridges in the manifold array that can be independently controlled. The output of the second manifold array carrying the odor was connected to a tube that had carrier flow (6 mL/s) of clean humidified air set by a mass flow controller (MC-series 500, Alicat Scientific) onto the live mosquito preparation. One of the channels of the manifold arrays was kept open between stimuli with humidified air flowing at 2 mL/s and closed whenever the odor stimuli were on to ensure a constant flow of 8 mL/s onto the preparation for the duration of the experiment. The odor cartridges were replaced between each mosquito preparation.

Calcium imaging system and analysis

Calcium signals were recorded using an epifluorescence microscope (BX51W1, Olympus) and an LED light source (Lambda HPX-L5, Sutter Instrument) and a 50X objective (LMPlanFLN, Olympus, 0.5 NA). Recordings were carried out at 30 fps using a CMOS camera (Orca-Fusion C14440, Hamamatsu Photonics K.K.) controlled by Micro-Manager.76 The videos were analyzed using Fiji75 to obtain ΔF/Fo traces. Regions of interest (ROIs) were selected using the “ROI manager” tool in Fiji, and fluorescence intensity traces were obtained with the multi measure function. For videos with CO2 stimulation of Gr22QF2>QUAS-GCaMP6f mosquitoes, an ROI was drawn around every fluorescent cell body in the fourth segment of the palp, and the responses of all units were averaged for each mosquito preparation. For videos of odor-evoked responses from Ir76bQF2>QUAS-GCaMP6f, Ir25aQF2>QUAS-GCaMP6f and orcoQF2>QUAS-GCaMP6f mosquitoes, ROIs were drawn around cell bodies that were visibly responding to each stimulus in the specified antennal segment, and the response of these units was averaged for each preparation. The analysis of the calcium traces obtained from Fiji and all statistical analyses were performed using MATLAB R2018b (The MathWorks Inc.). To calculate ΔF/Fo, the Fo value was calculated by averaging the fluorescence intensity of all the frames 0.5 s before stimulus onset.

Quantification and statistical analysis

We tested normality of maximum responses to treatment and control stimuli in calcium imaging experiments with a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. To test for the statistical significance of differences observed we used a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. All statistical analyses we performed in MATLAB R2018b (The MathWorks Inc.).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the Innovative Vector Control Consortium (P105) to C.J.M.; postdoctoral fellowships from the Human Frontier Science Program (LT000310/2019-L) and Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute to D.G.; and a Sir Henry Wellcome postdoctoral fellowship from the Wellcome Trust (213694/Z/18/Z) to A.M.H. Microscopy infrastructure at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Microscope Core Facility used in this research was supported by the National Institutes of Health NCRR (S10OD023548). We thank Tony Southall, Stephen Goodwin, and Andrea Crisanti for project advice and support; Kyros Kyrou, Eric Marois, Tony Nolan, Chris Potter, and Gareth Lycett for constructs; Niyati Jain, James Tan, Matthew Gribble, Louise Marston, Ioanna Morianou, Ana Perez-Lebron, Margot Wohl, and Stephanie Rankin-Turner for expert technical assistance; Olena Riabinina and members of the McMeniman lab for comments on the manuscript; and JHMRI and Bloomberg Philanthropies for generous supplemental funding and core infrastructure that supported this research.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, D.G., A.M.H., and C.J.M.; data curation, D.G. and J.W.; formal analysis, D.G., A.M.H., J.W., and C.J.M.; funding acquisition: D.G., A.M.H., and C.J.M.; investigation: D.G., A.M.H., J.W., B.F., N.A.-S., and C.J.M.; methodology: D.G., A.M.H., J.W., and C.J.M.; project administration: C.J.M.; visualization: D.G. and J.W.; writing – original draft, D.G., A.M.H., J.W., and C.J.M.; writing – review & editing, all authors.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: February 26, 2024

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crmeth.2024.100714.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Besansky N.J., Hill C.A., Costantini C. No accounting for taste: Host preference in malaria vectors. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:249–251. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott T.W., Takken W. Feeding strategies of anthropophilic mosquitoes result in increased risk of pathogen transmission. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takken W., Verhulst N.O. Host preferences of blood-feeding mosquitoes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013;58:433–453. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrett-Jones C., Boreham P.F.L., Pant C.P. Feeding habits of anophelines (Diptera: Culicidae) in 1971–78, with reference to the human blood index: A review. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1980;70:165–185. doi: 10.1017/S0007485300007422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Constantini C., Sagnon N.F., della Torre A., Coluzzi M. Mosquito Behavioral aspects of vector-human interactions in the Anopheles gambiae complex. Parasitologia. 1999;41:209–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dekker T., Takken W., Braks M.A. Innate preference for host-odor blends modulates degree of anthropophagy of Anopheles gambiae sensu lato (Diptera: Culicidae) J. Med. Entomol. 2001;38:868–871. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-38.6.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giraldo D., Rankin-turner S., Corver A., Tauxe G.M., Gao A.L., Jackson D.M., Simubali L., Book C., Stevenson J.C., Thuma P.E., et al. Human scent guides mosquito thermotaxis and host selection under naturalistic conditions. Curr. Biol. 2023;33:2367–2382.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smallegange R.C., Knols B.G.J., Takken W. Effectiveness of synthetic versus natural human volatiles as attractants for Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) Sensu Stricto. J. Med. Entomol. 2010;47:338–344. doi: 10.1603/ME09015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukabana W.R., Takken W., Coe R., Knols B.G.J. Host-specific cues cause differential attractiveness of Kenyan men to the African malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. Malar. J. 2002;1:17. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spitzen J., Spoor C.W., Grieco F., ter Braak C., Beeuwkes J., van Brugge S.P., Kranenbarg S., Noldus L.P.J.J., van Leeuwen J.L., Takken W. A 3D analysis of flight behavior of Anopheles gambiae sensu stricto malaria mosquitoes in response to human odor and heat. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takken W., Knols B.G. Odor-mediated behavior of afrotropical malaria mosquitoes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1999;44:131–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.44.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikbakhtzadeh M.R., Terbot J.W., II, Otienoburu P.E., Foster W.A. Olfactory basis of floral preference of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) among common African plants. J. Vector Ecol. 2014;39:372–383. doi: 10.1111/jvec.12113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nyasembe V.O., Teal P.E.A., Mukabana W.R., Tumlinson J.H., Torto B. Behavioural response of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae to host plant volatiles and synthetic blends. Parasit. Vectors. 2012;5:234. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foster W.A., Takken W. Nectar-related vs. human-related volatiles: behavioural response and choice by female and male Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) between emergence and first feeding. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2004;94:145–157. doi: 10.1079/BER2003288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rinker D.C., Pitts R.J., Zhou X., Suh E., Rokas A., Zwiebel L.J. Blood meal-induced changes to antennal transcriptome profiles reveal shifts in odor sensitivities in Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013;110:8260–8265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302562110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang J., Miller J.R., Chen S.C., Vulule J.M., Walker E.D. Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) oviposition in response to agarose media and cultured bacterial volatiles. J. Med. Entomol. 2006;43:498–504. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585. 43[498:AGDCOI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mozūraitis R., Hajkazemian M., Zawada J.W., Szymczak J., Pålsson K., Sekar V., Biryukova I., Friedländer M.R., Koekemoer L.L., Baird J.K., et al. Male swarming aggregation pheromones increase female attraction and mating success among multiple African malaria vector mosquito species. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020;4:1395–1401. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthews B.J., Dudchenko O., Kingan S.B., Koren S., Antoshechkin I., Crawford J.E., Glassford W.J., Herre M., Redmond S.N., Rose N.H., et al. Improved reference genome of Aedes aegypti informs arbovirus vector control. Nature. 2018;563:501–507. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0692-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carey A.F., Wang G., Su C.-Y., Zwiebel L.J., Carlson J.R. Odorant reception in the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Nature. 2010;464:66–71. doi: 10.1038/nature08834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang G., Carey A.F., Carlson J.R., Zwiebel L.J. Molecular basis of odor coding in the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:4418–4423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913392107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun H., Liu F., Ye Z., Baker A., Zwiebel L.J. Mutagenesis of the orco odorant receptor co-receptor impairs olfactory function in the malaria vector Anopheles coluzzii. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020;127 doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2020.103497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pitts R.J., Derryberry S.L., Zhang Z., Zwiebel L.J. Variant ionotropic receptors in the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae tuned to amines and carboxylic acids. Sci. Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/srep40297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raji J.I., Konopka J.K., Potter C.J. A spatial map of antennal-expressed ionotropic receptors in the malaria mosquito. Cell Rep. 2023;42 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu T., Qiu Y.T., Wang G., Kwon J.Y., Rutzler M., Kwon H.W., Pitts R.J., van Loon J.J.A., Takken W., Carlson J.R., Zwiebel L.J. Odor coding in the maxillary palp of the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1533–1544. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu F., Ye Z., Baker A., Sun H., Zwiebel L.J. Gene editing reveals obligate and modulatory components of the CO2 receptor complex in the malaria vector mosquito, Anopheles coluzzii. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2020;127:103470–103479. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2020.103470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Omondi B.A., Majeed S., Ignell R. Functional development of carbon dioxide detection in the maxillary palp of Anopheles gambiae. J. Exp. Biol. 2015;218:2482–2488. doi: 10.1242/jeb.116798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coutinho-Abreu I.V., Sharma K., Cui L., Yan G., Ray A. Odorant ligands for the CO2 receptor in two Anopheles vectors of malaria. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:2549. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39099-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herre M., Goldman O.V., Lu T.-C., Caballero-Vidal G., Qi Y., Gilbert Z.N., Gong Z., Morita T., Rahiel S., Ghaninia M., et al. Non-canonical odor coding in the mosquito. Cell. 2022;185:3104–3123.e28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Task D., Lin C.-C., Vulpe A., Afify A., Ballou S., Brbic M., Schlegel P., Raji J., Jefferis G.S.X.E., Li H., et al. Chemoreceptor co-expression in Drosophila melanogaster olfactory neurons. Elife. 2022;11:e72599. doi: 10.7554/eLife.72599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Afify A., Betz J.F., Riabinina O., Lahondère C., Potter C.J. Commonly used insect repellents hide human odors from Anopheles mosquitoes. Curr. Biol. 2019;29:3669–3680.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Z., Zung J.L., Hinze A., Kriete A.L., Iqbal A., Younger M.A., Matthews B.J., Merhof D., Thiberge S., Ignell R., et al. Mosquito brains encode unique features of human odour to drive host seeking. Nature. 2022;605:706–712. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04675-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Z., Tian D., McBride C.S. Development of a pan-neuronal genetic driver in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Cell Rep. Methods. 2021;1 doi: 10.1016/j.crmeth.2021.100042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ye Z., Liu F., Sun H., Ferguson S.T., Baker A., Ochieng S.A., Zwiebel L.J. Discrete roles of the Ir76b ionotropic co-receptor impact olfaction, blood feeding, and mating in the malaria vector mosquito Anopheles coluzzii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2022;119 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2112385119/-/DCSupplemental.Published. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riabinina O., Task D., Marr E., Lin C.-C., Alford R., O’Brochta D.A., Potter C.J. Organization of olfactory centres in the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Nat. Commun. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms13010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Konopka J.K., Task D., Poinapen D., Potter C.J. Neurogenetic identification of mosquito sensory neurons. iScience. 2023;26 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.106690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen T.W., Wardill T.J., Sun Y., Pulver S.R., Renninger S.L., Baohan A., Schreiter E.R., Kerr R.A., Orger M.B., Jayaraman V., et al. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laursen W.J., Budelli G., Tang R., Chang E.C., Busby R., Shankar S., Gerber R., Greppi C., Albuquerque R., Garrity P.A. Humidity sensors that alert mosquitoes to nearby hosts and egg-laying sites. Neuron. 2023;111:874–887.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2022.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfeiffer B.D., Truman J.W., Rubin G.M. Using translational enhancers to increase transgene expression in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:6626–6631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204520109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Volohonsky G., Terenzi O., Soichot J., Naujoks D.A., Nolan T., Windbichler N., Kapps D., Smidler A.L., Vittu A., Costa G., et al. Tools for Anopheles gambiae transgenesis. G3 (Bethesda) 2015;5:1151–1163. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.016808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoermann A., Tapanelli S., Capriotti P., Del Corsano G., Masters E.K., Habtewold T., Christophides G.K., Windbichler N. Converting endogenous genes of the malaria mosquito into simple non-autonomous gene drives for population replacement. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/ELIFE.58791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Han K., Levine M.S., Manley J.L. Synergistic activation and repression of transcription by Drosophila homeobox proteins. Cell. 1989;56:573–583. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hammond A., Galizi R., Kyrou K., Simoni A., Siniscalchi C., Katsanos D., Gribble M., Baker D., Marois E., Russell S., et al. A CRISPR-Cas9 gene drive system targeting female reproduction in the malaria mosquito vector Anopheles gambiae. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:78–83. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bateman J.R., Lee A.M., Wu C.T. Site-specific transformation of Drosophila via φC31 integrase-mediated cassette exchange. Genetics. 2006;173:769–777. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.056945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adolfi A., Lynd A., Lycett G.J., James A.A. Site-directed φC31-mediated integration and cassette exchange in Anopheles vectors of malaria. J. Vis. Exp. 2021 doi: 10.3791/62146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pitts R.J., Rinker D.C., Jones P.L., Rokas A., Zwiebel L.J. Transcriptome profiling of chemosensory appendages in the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae reveals tissue- and sex-specific signatures of odor coding. BMC Genom. 2011;12:271. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/17.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Athrey G., Cosme L.V., Popkin-Hall Z., Pathikonda S., Takken W., Slotman M.A. Chemosensory gene expression in olfactory organs of the anthropophilic Anopheles coluzzii and zoophilic Anopheles quadriannulatus. BMC Genom. 2017;18:751. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4122-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Brochta D.A., Pilitt K.L., Harrell R.A., Aluvihare C., Alford R.T. Gal4-based enhancer-trapping in the malaria mosquito Anopheles stephensi. G3. 2012;2:1305–1315. doi: 10.1534/g3.112.003582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ni L. The structure and function of ionotropic receptors in Drosophila. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020;13:638839. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2020.638839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Omondi A.B., Ghaninia M., Dawit M., Svensson T., Ignell R. Age-dependent regulation of host seeking in Anopheles coluzzii. Sci. Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46220-w. 9699–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rankin-Turner S., McMeniman C.J. A headspace collection chamber for whole body volatilomics. Analyst. 2022;147:5210–5222. doi: 10.1039/d2an01227h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bernier U.R., Kline D.L., Barnard D.R., Schreck C.E., Yost R.A. Analysis of human skin emanations by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. 2. Identification of volatile compounds that are candidate attractants for the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti) Anal. Chem. 2000;72:747–756. doi: 10.1021/ac990963k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martínez-Lozano P. Mass spectrometric study of cutaneous volatiles by secondary electrospray ionization. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2009;282:128–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2009.02.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takken W., Van Loon J.J.A., Adam W. Inhibition of host-seeking response and olfactory responsiveness in Anopheles gambiae following blood feeding. J. Insect Physiol. 2001;47:303–310. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1910(00)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meijerink J., Van Loon J.J.A. Sensitivities of antennal olfactory neurons of the malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae, to carboxylic acids. J. Insect Physiol. 1999;45:365–373. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1910(98)00135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qiu Y.T., van Loon J.J.A., Takken W., Meijerink J., Smid H.M. Olfactory coding in antennal neurons of the malaria mosquito. Chem. Senses. 2006;31:845–863. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjl027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cator L.J., George J., Blanford S., Murdock C.C., Baker T.C., Read A.F., Thomas M.B. “Manipulation” without the parasite: Altered feeding behaviour of mosquitoes is not dependent on infection with malaria parasites. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2013;280 doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.0711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cork A., Park K.C. Identification of electrophysiologically-active compounds for the malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae, in human sweat extracts. Med. Vet. Entomol. 1996;10:269–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1996.tb00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knols B.G., van Loon J.J., Cork A., Robinson R.D., Adam W., Meijerink J., Jong R.D., Takken W. Behavioural and electrophysiological responses of the female malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) to Limburger cheese volatiles. Bull. Entomol. Res. 1997;87:151–159. doi: 10.1017/s0007485300027292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]